Beyond Cost: The Role

of Intellectual Capital

in Offshoring and

Innovation in

Young Firms

Martina Musteen

Mujtaba Ahsan

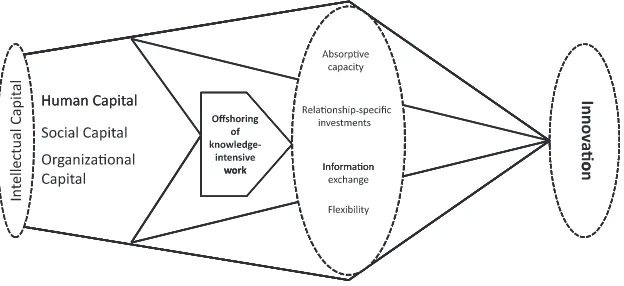

Using the intellectual capital perspective as a theoretical framework, we develop a concep-tual model of offshoring of knowledge-intensive, complex work by young, entrepreneurial firms. We posit that the unique qualities of human, social, and organizational capital of such firms drive them to offshore complex, nonroutine activities to foreign vendors. In addition, we argue that offshoring of such activities can lead to innovation under certain intellectual capital configurations.

O

ver the past several years, the topic of offshoring and outsourcing1has become the subject of attention of both academics and managers. Recently, scholars have been debating the changing nature of offshoring practices. They note that offshoring no longer involves only low-wage and low-skill production activities but also more technologically sophisticated activities including engineering and research and development (R&D; Grimpe & Kaiser, 2010; Manning, Massini, & Lewin, 2008). In addition, offshoring is no longer a domain of large corporations but it also occurs among young, entrepreneurial firms (Engardio, Arndt, & Faust, 2006). While research on offshoring by large corpora-tions has grown into a large body of literature, our understanding of the motivacorpora-tions and payoffs of offshoring undertaken by young firms is limited. One of the few studies that investigated the offshore outsourcing of smaller, entrepreneurial firms is that by Di Gregorio et al. (2009). It indicates that the practice is more common than expected and that cost does not always appear to be the primary driver of offshoring by small, and often younger, firms. Furthermore, Di Gregorio et al. provide some preliminary evidence thatPlease send correspondence to: Martina Musteen, tel.: (619) 594-8346; e-mail: mmusteen@mail.sdsu.edu, and to Mujtaba Ahsan at mahsan@pittstate.edu.

1. The terms offshoring and outsourcing have been defined in various ways (e.g., Mol, van Tulder, & Beige, 2005; USGAO, 2004; Venkatraman, 2004) and sometimes used interchangeably. In this study and consistent with Di Gregorio, Musteen, and Thomas (2009, p. 971), the focus is on the international outsourcing (or offshore outsourcing), a practice whereby a firm shifts some of its business processes to a foreign third-party vendor. Thus, it excludes domestic outsourcing and captive offshoring (i.e., internally managed foreign direct investment).

P

T

E

&

1042-2587

© 2011 Baylor University

offshoring of more technologically sophisticated and knowledge-intensive activities such as software development or engineering may lead to better performance outcomes than offshoring of routine, manufacturing tasks. A few other studies (e.g., Klaas, Klimchak, Semadeni, & Holmes, 2010; Lewin, Massini, & Peeters, 2009) have also suggested that international outsourcing of knowledge-intensive, complex work (as opposed to routine, manufacturing tasks) may be associated with the development of new capabilities on the part of the offshorers. Our research note seeks to extend this line of research. It draws on the literature on intellectual capital to develop a conceptual model of offshoring of knowledge-intensive work by young entrepreneurial firms and start-ups. Such firms are subject to a special set of challenges due to their small size, resource constraints, and lack of institutional legitimacy but are also characterized by distinct competitive advantages arising from organizational agility, ability to leverage external, socially embedded resources, and strategic flexibility. Thus, their motivations for offshoring as well as the benefits they accrue from offshoring arrangements are likely to be different from those of larger established firms.

Most of the extant research on offshoring has focused on the cost benefits associated with the practice. The offshoring literature has been rather silent on one of the potential benefits of offshoring—innovation.2Innovation has long been viewed as key to achieving sustainable competitive advantage and superior profitability (Conner, 1991) and young firms have often been seen as the primary drivers of innovation (more so than larger firms; Acs & Audretsch, 1990). Drawing on organizational learning and network perspectives, we posit that the human, social, and organizational dimensions of intellectual capital of young firms represent a driver of offshoring of knowledge-intensive activities. Moreover, we identify processes that emerge as a result of offshoring of knowledge-intensive activi-ties and lead to innovation. Most importantly, we theorize that whether or not offshoring results in greater innovation depends on the qualities of the intellectual capital embedded in the offshoring firms.

Our research note makes three main contributions to the extant literature. First, we extend the research on offshoring by examining the phenomenon in the context of young firms and by focusing on the most recent “new generation” of offshoring whereby knowledge-intensive processes are outsourced internationally by such firms. We push the offshoring research agenda forward by offering an empirically testable conceptual model, which links firm-specific characteristics to offshoring and identifies processes that are likely to lead to innovation. Second, by examining the intellectual capital dimensions of young firms and their impact on offshoring and innovation, we also contribute to the literature on intellectual capital. Most research on intellectual capital has focused on large firms or considered only one dimension of the construct. Our study extends the literature by describing how human, social, and organizational dimensions of intellectual capital affect the decision to offshore important value chain activities and how they enable innovative behavior of young firms. Third, we contribute to the growing international entrepreneurship (IE) literature. As Di Gregorio, Musteen, and Thomas (2008) suggest, only a few IE studies considered internationalization of firms’ value chain activities other than international sales. Our study examines how shifting “upstream” value chain activities to international partners affects innovation, which, in turn, enhances international competitiveness of young firms (Di Gregorio et al., 2009).

The balance of the paper is structured as follows. First, we provide a brief overview of the intellectual capital construct. Then, we describe how its three dimensions— human, social, and organizational—act as a driver of offshoring of young firms. We follow by theorizing how offshoring leads to innovation and how intellectual capital represents a catalyst to such innovation. We conclude with a discussion of the impli-cations of the theoretical model for research and practice and provide avenues for future research.

Theoretical Background

Intellectual capital has been defined as the sum of all knowledge that firms utilize for competitive advantage (Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005). Considered to represent firms’ stock of most important intangible resources (Rialp & Rialp, 2006), intellectual capital consists of three interrelated dimensions—human, social, and organizational capital. Human capital is defined as the knowledge, skills, and abilities of individuals (Schultz, 1961) while social capital refers to the resources derived from social relationships both within and across organizations (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). Organizational capital relates to firm’s knowledge embedded in routines, structures, systems, and processes (Subramaniam & Youndt).

The three dimensions of intellectual capital have been found to be closely related to firms’ configuration of value chain activities. Youndt, Subramanian, and Snell (2004), for example, observed that firms with high levels of human, social, and organizational capital tend to invest heavily in information technology and R&D. Kang and Snell (2009) noted that different intellectual capital architecture directly influences the configuration of human resource management activities. Thus, the intellectual capital perspective lends itself well to the examination of young firms’ outsourcing of high-skill, knowledge-intensive activities to international vendors. This is particularly true from the perspective of IE literature that views internationally active ventures and young firms as distinctively skilled in integrating international economic activities (Matthews & Zander, 2007). In the next sections, we discuss how intellectual capital drives offshoring of complex, value-adding activities by young firms and how intellectual capital functions as a catalyst for offshoring-based innovation. The visual representation of our conceptual model is pre-sented in Figure 1.

Intellectual Capital as a Driver of Offshoring by Young Firms

The intellectual capital of young firms is qualitatively different from intellectual capital of larger, established firms. Each of its dimensions—human, social, and organizational—is likely to play a unique role in young firms’ motivations to outsource their knowledge-intensive processes to international vendors. We detail our arguments linking the intellectual capital dimensions to offshoring below.

Human Capital and Offshoring

larger, established firms (Desouza & Awazu, 2006). This is exacerbated by the tight labor market for expert knowledge workers, stricter visa requirements on immigrant workers (Bhide, 2008) and the recent pressure on companies to expense stock options (a traditional form of compensation in start-ups). The human capital of young firms is also characterized by a greater number of generalists (i.e., less-specialized employees) given that fewer individuals are expected to perform a greater variety of functions. This lack of specialist expertise along with little support for specific employee training and development programs translate into relatively low levels of human capital. Yet, attract-ing, retainattract-ing, and motivating expert workers have been identified as one of the critical drivers of product innovation among small firms (Branzei & Vertinsky, 2006). Given the abundance of relatively inexpensive, educated labor abroad, it is not surprising that young firms consider offshoring of its knowledge-based processes as a way to access talent and supplementing their stock of human capital. Indeed, according to Ernst (2006), competing in the emerging global market for knowledge workers has become critically important as it creates new sources of talent. Thus, offshoring of knowledge-intensive process is one way of overcoming human capital deficiencies on the part of young firms.

Social Capital and Offshoring

The unique nature of social capital in young firms is another reason why such firms increasingly turn to offshoring of their more complex, value-added activities. Research in entrepreneurship has shown that young firms rely extensively on external (or bridg-ing) relationships to obtain resources and achieve profitability (Davidsson & Honig, 2003). Young firms have been shown to take advantage of strategic alliances and mem-bership in networks to reduce uncertainty, enhance credibility, and gain access to oppor-tunities and competencies (McEvily & Zaheer, 1999). As Baum, Calabrese, and Silverman’s study (2000) suggests, young start-ups are particularly motivated to form partnerships with others to gain access to social, technical, and commercial competitive resources that normally require years of operating experience. Increasingly, because of

Figure 1

Conceptual Model of Young Firms’ Intellectual Capital, Offshoring, and Innovation

-the advances in technology and falling communication barriers, such firms are also beginning to tap relationships with individuals and firms abroad (Preece, Miles, & Baetz, 1999). This enables them not only to take advantage of opportunities in the foreign product markets but also to revamp their value chains (Di Gregorio et al., 2008) by way of offshoring.

The bridging form of social capital that young firms skillfully develop and leverage is thus another driver of international outsourcing of knowledge-intensive activities by young firms. Many new entrepreneurial businesses take advantage of their bridging ties (i.e., personal connections) that their first-generation immigrant managers or employees have with their home countries in the offshore regions in India and China (Saxenian, 2002), for example. Such relationships provide young firms with information on potential offshoring opportunities and also on the practice of offshoring itself. This decreases the cost of searching for potential vendors and enhances confidence of young firms in their ability to manage the offshore arrangement.

Organizational Capital and Offshoring

Finally, the organizational capital of young firms is another factor that induces young firms to offshore their value-added, knowledge-intensive work. Emerging businesses are typically very different from larger corporations in terms of their organizational structure and processes. For one, such firms often compete in specialized, niche markets with a set of fairly narrowly defined know-how. To compete with larger, more established firms, they must continually update their stock of capabilities and respond actively to changes in the external environment. The lack of economies of scale makes it difficult for young firms to develop many auxiliary and support functions and services. Thus, offshoring of at least some of such activities (e.g., software development, engineering, human resources, and R&D work) may be particularly beneficial. As Arend and Wisner (2005) suggest, by handing over noncore business activities, young firms can leverage their scalable compe-tencies such as new product development and design. Externalizing their value chain activities to foreign suppliers further enhances young firms’ flexibility and responsive-ness, qualities that are often lacking in large, established multinationals (Liesch & Knight, 1999).

Low levels of formalization, organic structure, and entrepreneurial culture are typi-cally considered to be an advantage of start-ups and young firms. However, they also contribute to the resistance to codification and effective embedding of organizational knowledge (Feldman & Klofsten, 2000). As Jones and Macpherson (2006) documented, such firms often look to external organizations (e.g., suppliers, customers) to help them develop systems, routines, and procedures necessary to develop organizational knowl-edge. They found that by turning to external organizations, resource-constrained firms can overcome the disadvantages associated with low levels of organizational capital. Thus, contracting with a foreign provider of a business service such as back-office information technology, customer care, or higher skill business processes can be viewed as giving young firms the benefit of both tapping organizational knowledge of others while focusing on the activities that form the core of their competitive advantage.

Offshoring-Based Innovation

offshore partners. Indeed, offshoring can supplement, augment, and leverage the intellec-tual capital available to emerging businesses. In this section, we theorize how offshoring helps firms innovate. In the following section, we explain how the three dimensions of intellectual capital enable such innovation.

Literature states that young firms must view innovation as a priority and utilize a strategy of exploiting advantages of flexibility, speed of response, and external sources of knowledge to produce innovations and compete with larger and more established firms (Acs & Audretsch, 1990; Zahra, Sapienza, & Davidsson, 2006). Innovation has also been viewed as key to attaining global competitiveness (Knight & Kim, 2008). Previous research (e.g., Barnett & Storey, 2000; McCann, 1991) also suggests that young firms do not innovate in formally recognized ways. That is, as opposed to larger, established firms, they tend to innovate through ad hoc improvisation, not through formal scientific experimentation (Zahra et al.). The process and product innovation of emerging businesses is often based on their ability to rapidly integrate, develop, and reconfigure their internal capabilities and external competencies in order to address the changing environmental conditions and needs of their customers (Cusmano, Mancusi, & Morrison, 2009). An important element in such an innovation process of young firms is the speed with which they commercialize and bring new technologies to market. Off-shoring of certain high-end, knowledge-intensive work helps them do so. Instead of developing competencies in-house, offshoring of such activities to qualified partners allows young firms to decrease their lead times and focus on marketing of their products and services in the local market.

According to Bhide (2009), most young firms that innovate are niche players that focus on customization of products or services marketed to other businesses. Offshoring helps such firms minimize the risk associated with developing innovative new offerings. For example, they can hand over the development of peripheral projects that have not yet been commercially proven but can potentially improve their core offering. Chesbrough and Garman (2009, p. 71) refer to this process as an “inside-out open innovation,” which allows firms to “reduce R&D costs without relinquishing related growth opportunities.” This increases their chances of successful innovation commer-cialization (Carayannopoulos, 2009).

Offshoring also provides young firms the opportunity to access new and diverse ideas from a variety of supply markets and cultural perspectives. That can lead to innovation in terms of new products and processes (Miller, 1996) but also improved business models. According to Chesbrough (2007), innovation in business models is difficult. The most advanced, innovative business models are those based on bringing together external technologies and integrating suppliers into the internal processes. Offshoring of knowledge-intensive activities is most likely to create conditions where entrepreneurs recognize opportunities for doing so. Unlike international outsourcing of routine, low-skill tasks, offshoring of activities such as software development, product design, engi-neering, and R&D requires intensive intra-organizational collaboration and transfer of information between the offshoring company and the foreign service provider. It develops over an extended period of time, making the offshore relationship less transaction-oriented and more cooperative in nature (Vivek, Richey, & Dalela, 2009). The greater “customer-stickiness” associated with offshoring of complex, knowledge-intensive activi-ties enables young firms to share knowledge and find novel ways of combining resources and improving their processes.

In the next section, we describe how the human, social, and organizational dimensions of young firms’ intellectual capital influence offshoring-based innovation.

Intellectual Capital as a Catalyst for Offshoring Innovation

offshoring young firms is likely to enhance chances that such firms reap offshoring-based innovation benefits.

Finally, the degree to which offshoring of knowledge-intensive work leads to innova-tion among young firms is likely to be contingent on the nature of their organizainnova-tional capital. Young firms and new ventures possess a stock of organizational capital that is very different from that of larger, well-established corporations. While lack of such organiza-tional capital (embedded in manuals, systems, and formal structures) is one of the reasons why young firms are initially motivated to offshore some of their knowledge-intensive activities, the lack of rigid, bureaucratic structures and few reporting procedures provide benefits in terms of less-constricted information flows within and outside the organization. This can lead to greater absorptive capacity (Lane & Lubatkin, 1998) wherein young firms easily recognize and implement new ideas in their routines and processes. The IE literature refers to such ability as the “learning advantage of newness” (Zahra, 2005). This unique nature of organizational capital enhances the learning that occurs within the offshoring relationship and ultimately should lead to greater innovation. Specifically, the lack of formal organizational systems and processes enables young firms to gain as well as quickly implement creative insights from the cooperation with their offshore service providers. The high involvement of owners-managers in the offshore relationship (which is unique to young firms) facilitates the dissemination of such new knowledge to creative uses in their organizations. Thus, unhindered by organizational capital embedded in rigid routines and codified practices, young firms are more flexible and thus in a better position to put into practice and act upon novel solutions emerging from their offshore arrangements.

Taken together, each of the intellectual capital dimensions impacts the degree to which firms can attain benefits of offshoring-based innovation. This occurs by affecting the absorptive capacity, the motivation to engage in offshore relationship-specific invest-ments and information sharing, and flexibility to implement new ideas.

Discussion

Using the intellectual capital perspective as a theoretical framework, we sought to deepen our understanding of the “new generation” of offshoring whereby young firms outsource some of their high value-added, knowledge-intensive activities to international vendors. First, we examined how intellectual capital of young firms acts as a driver of such offshoring. Our analysis revealed that there are many reasons other than cost savings that induce young firms to offshore their knowledge-intensive activities. Specifically, the deficiencies in human and organizational capital of young firms push them to tap the talent of their offshore vendors while retaining their flexibility. In addition, their social capital and the ability to harness external resources of others make young firms uniquely posi-tioned to learn about and leverage offshore partnerships. Second, we argued that offshor-ing of knowledge-intensive activities can lead to greater innovation on the part of the young firms. However, this is contingent on their intellectual capital configuration. In other words, the level of human, social, and organizational capital is an important factor in offshoring-based innovation by enabling mechanisms such as enhanced learning and absorptive capacity, information sharing, relationship-specific investments, and organiza-tional flexibility, which are antecedents for such innovation.

Theoretical Implications

literature by explaining the relatively new phenomenon of young firms’ offshoring of technologically sophisticated, knowledge-intensive activities. We conceptualize the role of the intellectual capital in offshoring of such activities as a two-stage model where the unique configuration of intellectual capital of young firms pushes such firms to offshore high value-added work and it also affects the degree to which they benefit from the offshoring relationship. In doing so, we extend Vivek et al.’s (2009) and Di Gregorio et al.’s (2009) research that suggested that lower cost is no longer the only motivation to outsource value chain activities internationally. In our paper, we focus on one such non-cost benefit—innovation. We thus contribute to the literature on innovation by identifying the ways young companies can gain new insights and engage in creative cooperation with their offshore partners. Specifically, we outline how (i.e., through which processes) intellectual capital of young firms catalyzes and enables generation of new ideas and solutions in the context of the offshoring relationship, which ultimately leads to greater innovation. Our paper is one of the first to present testable conceptual model linking the unique qualities of young firms (e.g., relative lack of human capital, strong reliance on relational forms of governance with external partners, and organic structure) with the “new generation” of offshoring and the outcomes associated with the same.

Our paper also represents a contribution to the emerging literature on IE, a stream of research on innovative, risk-taking behavior of firms across national borders (McDougall & Oviatt, 2000). While most studies of IE have focused on exploitation of opportunities in terms of foreign sales and product markets (Di Gregorio et al., 2008), our model suggests that young firms can also reap substantial benefits by exploring opportunities in internationalization of their value chains via offshoring. As Zahra (2005) noted in his article on theory of international new ventures (INVs), one of the critical insights of Oviatt and McDougall’s (1994) seminal paper was that firms that internationalize at or soon after inception (i.e., INVs) do not typically own all the resources necessary to internationalize their operations. Our work draws the attention to the importance of tapping external capabilities of offshore partners. Specifically, we have focused on the innovation-based benefits conferred on young firms that internationalize some of their complex, knowledge-intensive work to foreign partners.

Finally, our work presents a complementary perspective on the motivation for inter-nationalization of young firms. In general, the IE literature has suggested that three factors motivate young ventures to compete globally. First, their tendency to operate in niche markets limits their market opportunities locally. This makes it important for them to expand internationally to achieve sales growth. Second, the high cost of research and development makes international expansion a necessity to achieve growth and support such large upfront costs. Third, the speed of technological change and product obsoles-cence forces them to accelerate market penetration. Under the conditions of intense competition, the speed of product and market development becomes critically important for young firms’ success (Preece et al., 1999, p. 261). Our paper suggests that through offshoring, young firms can not only overcome the large upfront costs and lead times associated with product development, but they can also attain resources necessary for innovation. Given the avowed link between survival and growth of young firms and innovation, our paper draws the attention of scholars toward “innovation-seeking” off-shoring behavior in young firms and thereby makes a contribution to the IE literature.

Implications for Entrepreneurs

innovation is not guaranteed as it depends on the levels of human, social, and organiza-tional capital in their organizations. For example, our model suggests that offshoring can help young firms overcome the deficiencies in their human resources. However, such firms must have the absorptive capacity—the capability to learn and recognize new knowledge and apply it to new solutions in order to tap the innovation benefits of offshoring. This requires human capital that has the requisite technological and marketing knowledge. Our model also indicates that young firms (more so than established corporations) should invest in social capital in their offshore partnerships. This represents a form of governance as well as facilitates relationship-specific investments and information sharing between the partners, which promotes innovation.

Operationalization and Empirical Testing

The natural next step in advancing our research is testing our model empirically. The literature on offshoring of knowledge-intensive work is still relatively limited. Therefore, the existing measures are also few, typically consisting of survey items asking offshoring firms about the activities they outsource to foreign vendors (Weigelt, 2009). In some studies, offshoring has been conceptualized as a nominal variable indicating whether or not a firm offshores a particular activity (Di Gregorio et al., 2009). Fortunately, research-ers interested in empirical testing of our theoretical model can rely on numerous measures of intellectual capital (e.g., Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Hayton & Zahra, 2005; Marvel & Lumpkin, 2007; McEvily & Zaheer, 1999).

Given the mediating and moderating relationships proposed in our model, empirical testing of our propositions will be best suited for structural equation modeling tech-niques. Qualitative studies are also likely to be helpful in assessing the validity of the theoretical model and motivations of firms to offshore their knowledge-intensive work and provide insights on the processes that we identified as leading to offshoring-based innovation.

Boundary Conditions and Future Research

On a macroeconomic level, it would be interesting to see if there are longitudinal and geographical patterns in offshoring of knowledge-intensive activities by young firms. With further falling of barriers to finding qualified offshore partners and technology enabling shifting such activities abroad, it is likely that we will see more offshoring particularly by high-tech start-ups.

On the firm level, future studies should seek to identify other mediating and moder-ating factors of offshoring by young firms and its impact on firm-level innovation. For example, how does the age of the firms influence their proclivity to outsource complex, knowledge-based activities to foreign service providers? Very young start-ups, despite their lack of human capital, may be more inclined to keep most of their activities in-house or choose onshore partners, given that their value chain activities are very fluid and it may be difficult to distinguish core activities from those that can be outsourced. Young firms that have had time to establish some routines and processes may be therefore better candidates. Another valuable extension of our work would address the question whether offshoring of certain knowledge-intensive processes leads to more innovation than others. A recent research by Grimpe and Kaiser (2010) suggested that R&D outsourcing can lead to innovation but only to a certain point. It may be interesting to examine how offshoring of other knowledge-intensive activities such as software development or engineering differs in terms of its impact on innovation.

In conclusion, the objective of this research note was to examine the role that the intellectual capital plays in the offshoring of knowledge-intensive work by young com-panies. In doing so, we shed more light on a relatively new trend of young firms’ offshoring (Dossani & Kenney, 2007). We hope our work stimulates further research on this topic.

REFERENCES

Acs, Z.J. & Audretsch, D.B. (1990).Innovation and small firms. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Arend, R. & Wisner, J. (2005). Small business and supply chain management: Is there a fit?Journal of

Business Venturing,20(3), 403–436.

Barnett, E. & Storey, J. (2000). Managers accounts of innovation processes in small and medium-sized enterprises.Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development,7, 315–324.

Baum, J.A., Calabrese, T., & Silverman, B.S. (2000). Don’t go it alone: Alliance network composition and startups’ performance in Canadian biotechnology.Strategic Management Journal,21, 267–294.

Bhide, A. (2008).The venturesome economy: How innovation sustains prosperity in a more connected world. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bhide, A. (2009). The venturesome economy: How innovation sustains prosperity in a more connected world.

Journal of Applied Corporate Finance,21(1), 8–23.

Branzei, O. & Vertinsky, I. (2006). Strategic pathways to product innovation capabilities in SMEs.Journal of

Business Venturing,21(1), 75–105.

Carayannopoulos, S. (2009). How technology-based new firms leverage newness and smallness to commer-cialize disruptive technologies.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,33(2), 419–438.

Chesbrough, H. (2007). Business model innovation: It’s not just about technology anymore.Strategy and

Chesbrough, H.W. & Garman, A.R. (2009). How open innovation can help you cope in lean times.Harvard

Business Review,87(12), 68–76.

Conner, K. (1991). Theory of the firm: Firm resources and other economic theories.Journal of Management,

17, 121–154.

Cusmano, L., Mancusi, M.L., & Morrison, A. (2009). Innovation and the geographical and organisational dimensions of outsourcing: Evidence from Italian firm-level data.Structural Change and Economic Dynam-ics,20(3), 183–195.

Davidsson, P. & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs.Journal

of Business Venturing,18, 301–333.

Desouza, K.C. & Awazu, Y. (2006). Knowledge management at SMEs: Five peculiarities.Journal of

Knowl-edge Management,10, 32–43.

Di Gregorio, D., Musteen, M., & Thomas, D.E. (2008). International new ventures: The cross-border nexus of individuals and opportunities.Journal of World Business,43(2), 186–196.

Di Gregorio, D., Musteen, M., & Thomas, D.E. (2009). Offshoring as a source of international competitive advantage for SMEs.Journal of International Business Studies,40(6), 969–988.

Dossani, R. & Kenney, M. (2007). The next wave of globalization: Relocating service provision to India.

World Development,35, 772–791.

Dyer, J.H. & Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage.Academy of Management Review,23, 660–679.

Engardio, P., Arndt, M., & Faust, D. (2006). The future of outsourcing. Business Week, January 30. http:// www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/06_05/b3969401.htm

Ernst, D. (2006). Innovation offshoring: Asia’s emerging role in global innovation networks.East-West Center

Special Reports,10, 1–48.

Feldman, J.M. & Klofsten, M. (2000). Medium-sized firms and the limits to growth: A case study in the evolution of a spin-off firm.European Planning Studies,8, 631–650.

Fernhaber, S.A. & McDougall-Covin, P.P. (2009). Venture capitalists as catalysts to new venture internation-alization: The impact of their knowledge and reputation resources.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,

33(1), 277–295.

Grimpe, C. & Kaiser, U. (2010). Balancing internal and external knowledge acquisition: The gains and pains from R&D outsourcing.Journal of Management Studies,47(8), 1483–1509.

Hayton, J.C. & Zahra, S.A. (2005). Venture team human capital and absorptive capacity in high technology new ventures.International Journal of Technology Management,31, 256–274.

Jones, O. & Macpherson, A. (2006). Inter-organizational learning and strategic renewal in SMEs: Extending the 4I framework.Long Range Planning,39, 155–175.

Kang, S. & Snell, S.A. (2009). Intellectual capital architectures and ambidextrous learning: A framework for human resource management.Journal of Management Studies,46, 65–92.

Klaas, B., Klimchak, M., Semadeni, M., & Holmes, J. (2010). The adoption of human capital services by small and medium enterprises: A diffusion of innovation perspective.Journal of Business Venturing,25(4), 349–360.

Knight, G.A. & Kim, D. (2008). International business competence and the contemporary firm.Journal of

Lane, P.J. & Lubatkin, M. (1998). Relative absorptive capacity and interorganizational learning.Strategic

Management Journal,19(5), 461–477.

Levina, N. & Su, N. (2008). Global multisourcing strategy: The emergence of a supplier portfolio in services offshoring.Decision Sciences,39(3), 541–570.

Lewin, A., Massini, S., & Peeters, C. (2009). Why are companies offshoring innovation? The emerging global race for talent.Journal of International Business Studies,40(6), 901–925.

Liesch, P.W. & Knight, G.A. (1999). Information internalization and hurdle rates in small and medium enterprise internationalization.Journal of International Business Studies,31, 383–394.

Manning, S., Massini, S., & Lewin, A.Y. (2008). A dynamic perspective on next-generation offshoring: The global sourcing of science and engineering talent.Academy of Management Perspectives,22(3), 35– 54.

Marvel, M.R. & Lumpkin, G.T. (2007). Technology entrepreneurs human capital and its effects on innovation radicalness.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,31, 807–828.

Matthews, J.A. & Zander, I. (2007). The international entrepreneurial dynamics of accelerated internation-alization.Journal of International Business Studies,38(3), 387–403.

McCann, J.E. (1991). Patterns of growth, competitive technology, and financial strategies in young ventures.

Journal of Business Venturing,6(3), 189–208.

McDougall, P.P. & Oviatt, B.M. (2000). International entrepreneurship: The intersection of two research paths.Academy of Management Journal,43(5), 902–906.

McEvily, B. & Zaheer, A. (1999). Bridging ties: A source of firm heterogeneity in competitive capabilities.

Strategic Management Journal,20, 1133–1156.

Miller, D. (1996). A preliminary typology of organizational learning: Synthesizing the literature.Journal of

Management,22, 485–505.

Mol, M.J., van Tulder, R.J.M., & Beige, P.R. (2005). Antecedents and performance consequences of inter-national outsourcing.International Business Review,14, 599–617.

Nahapiet, J. & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage.

Academy of Management Review,23, 242–266.

Oviatt, B. & McDougall, P.P. (1994). Toward a theory of international new ventures.Journal of International

Business Studies,25, 45–64.

Preece, S.B., Miles, G., & Baetz, M. (1999). Explaining the international intensity and global diversity of early-stage technology-based firms.Journal of Business Venturing,14(3), 259–281.

Rialp, A. & Rialp, J. (2006). Faster and more successful exporters: An exploratory study of born global firms from the resource-based view.Journal of Euro-Marketing,16, 71–86.

Rialp, A., Rialp, J., & Knight, G.A. (2005). The phenomenon of early internationalizing firms: What do we know after a decade (1993–2003) of scientific inquiry?International Business Review,14(2), 147–166. Saxenian, A. (2002). Silicon valley’s new immigrant high-growth entrepreneurs. Economic Development

Quarterly,16(1), 20–31.

Schultz, T. (1961). Investment in human capital.American Economic Review,51(1), 1–17.

USGAO. (2004). International trade: Current government data provide limited insight into offshoring of

services. Washington, DC: GAO.

Venkatraman, N.V. (2004). Offshoring without guilt.MIT Sloan Management Review,45(3), 14–16. Vivek, S.D., Richey, R.G., & Dalela, V. (2009). A longitudinal examination of partnership governance in offshoring: A moving target.Journal of World Business,44, 16–30.

Weigelt, C. (2009). The impact of outsourcing new technologies on integrative capabilities and performance.

Strategic Management Journal,30(6), 595–616.

Youndt, M.A., Subramanian, M., & Snell, S.A. (2004). Intellectual capital profiles: An examination of investments and returns.Journal of Management Studies,41, 335–361.

Zahra, S.A. (2005). Theory on international new ventures: A decade of research.Journal of International

Business Studies,36(1), 20–28.

Zahra, S., Sapienza, H., & Davidsson, P. (2006). Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: A review, model and research agenda.Journal of Management Studies,43(4), 917–955.

Zollo, M., Reuer, J.J., & Singh, H. (2002). Interorganizational routines and performance in strategic alliances.

Organization Science,13, 701–713.

Martina Musteen is an Associate Professor in the College of Business Administration at the San Diego State University.

Mujtaba Ahsan is an Assistant Professor of Management in the Kelce College of Business at the Pittsburg State University.