This is an electronic version of the print textbook. Due to electronic rights restrictions, some third party content may be suppressed. Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience.

The publisher reserves the right to remove content from this title at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

For valuable information on pricing, previous editions, changes to current editions, and alternate formats,

please visit www.cengage.com/highered to search by ISBN#, author, title, or keyword for materials in your areas of interest.

MEDIA

NOW

Understanding Media, Culture, and Technology

SEVENTH EDITION

JOSEPH STRAUBHAAR

University of Texas, Austin

ROBERT L

A

ROSE

Michigan State University

LUCINDA DAVENPORT

Michigan State University

© 2012, 2009, 2006 Wadsworth, Cengage Learning

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including but not limited to photocopying, recording, scanning, digitizing, taping, Web distribution, information networks, or information storage and retrieval systems, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010934545

ISBN-13: 978-1-4390-8257-7

ISBN-10: 1-4390-8257-X

Wadsworth

20 Channel Center Street Boston, MA 02210 USA

Cengage Learning is a leading provider of customized learning solutions with offi ce locations around the globe, including Singapore, the United Kingdom, Australia, Mexico, Brazil, and Japan. Locate your local offi ce at:

international.cengage.com/region

Cengage Learning products are represented in Canada by Nelson Education, Ltd.

For your course and learning solutions, visit www.cengage.com. Purchase any of our products at your local college store or at our preferred online store www.cengagebrain.com.

Media Now: Understanding Media, Culture, and Technology, Seventh Edition

Joseph Straubhaar, Robert LaRose, Lucinda Davenport

Senior Publisher: Lyn Uhl

Publisher: Michael Rosenberg

Development Editor: Megan Garvey

Assistant Editor: Jillian D’Urso

Editorial Assistant: Erin Pass

Media Editor: Jessica Badiner

Marketing Director: Jason Sakos

Marketing Coordinator: Gurpreet Saran

Marketing Communications Manager: Tami Strang

Content Project Manager: Corinna Dibble

Art Director: Marissa Falco

Manufacturing Manager: Denise Powers

Rights Acquisition Specialist: Mandy Groszko

Production Service: PreMediaGlobal

Text Designer: Yvo Riezebos

Cover Designer: Yvo Riezebos

Compositor: PreMediaGlobal

For product information and technology assistance, contact us at

Cengage Learning Customer & Sales Support, 1-800-354-9706

For permission to use material from this text or product, submit all requests online at www.cengage.com/permissions.

Further permissions questions can be emailed to

B R I E F C O N T E N T S

i i i

PART ONE

Media and the Information Age

CHAPTER 1

The Changing Media 3

CHAPTER 2

Media and Society 27

PART TWO

The Media

CHAPTER 3

Books and Magazines 55

CHAPTER 4

Newspapers 87

CHAPTER 5

Recorded

Music 125

CHAPTER 6

Radio 153

CHAPTER 7

Film and Home Video 181

CHAPTER 8

Television 211

CHAPTER 9

The

Internet 247

CHAPTER 10

Public

Relations 281

CHAPTER 11

Advertising 309

CHAPTER 12

The Third Screen: From Bell’s Phone to

iPhone 345

PART THREE

Media Issues

CHAPTER 13

Video

Games 377

CHAPTER 14

Media Uses and Impacts 403

CHAPTER 15

Media Policy and Law 445

CHAPTER 16

Media

Ethics 473

CHAPTER 17

Global Communications Media 499

C O N T E N T S

v

Contents

Preface xvii

About the Authors xxiii

PART ONE

Media and the Information Age

CHAPTER 1

The Changing Media

3

The Media in Our Lives 3 Media in a Changing World 4

Merging Technologies 5

TECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED:

■ A Digital Media Primer 6

Changing Industries 8 Changing Lifestyles 8

YOUR MEDIA

■ CAREER: Room at the bottom, Room at the top 9

Shifting Regulations 10 Rising Social Issues 11

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ A New Balance of Power? 12

Changing Media Throughout History 12 Preagricultural Society 13

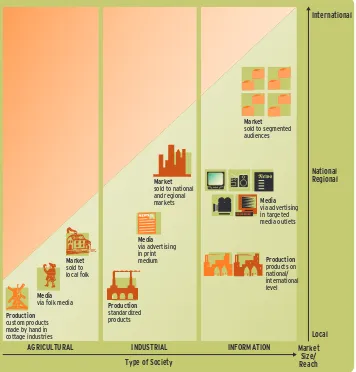

Agricultural Society 13 Industrial Society 13 Information Society 15

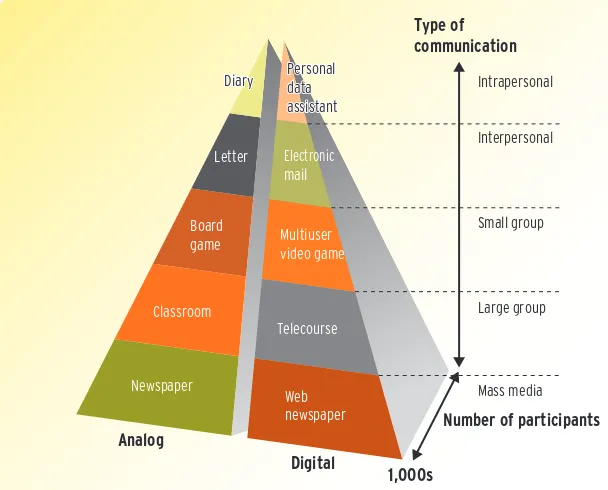

Changing Conceptions of the Media 16 The Smcr Model 17

Types of Communication 18 What are the Media Now? 20

Summary & Review 24 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 25 ■ Key Terms 25

CHAPTER 2

Media and Society

27

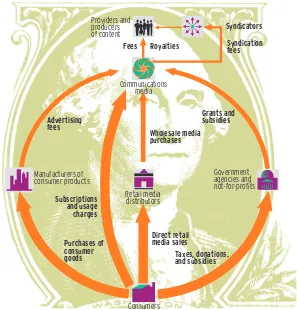

Understanding the Media 27 Media Economics 28

Mass Production, Mass Distribution 28

YOUR MEDIA CAREER:

■ Media Scholar 30

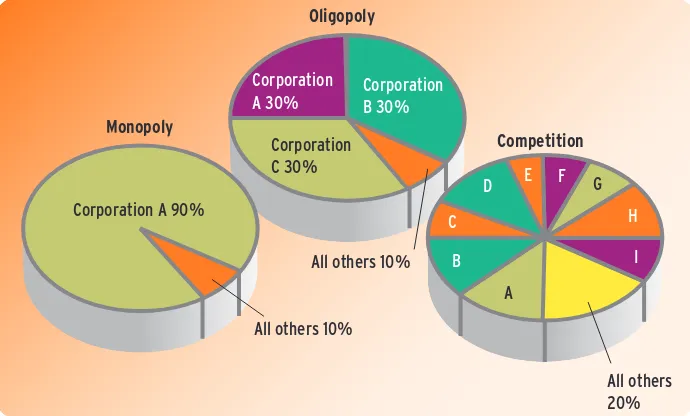

The Benefi ts of Competition 31 Media Monopolies 31

The Profi t Motive 33 How Media Make Money 35

From Mass Markets to Market Segments 36 New Media Economics 37

Critical Studies 39 Political Economy 39 Feminist Studies 41

Jim W

ilson/The New Y

ork Times/R

edux Pictur

es

Br

v i

C O N T E N T SEthnic Media Studies 42 Media Criticism 42

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Postmodernism 43

Diffusion of Innovations 44

Why Do Innovations Succeed? 44 How Do Innovations Spread? 44 What are the Media’s Functions? 46

Media And Public Opinion 47 Gatekeeping 47

Agenda Setting 48 Framing 49

Technological Determinism 49 The Medium is the Message 49

Technology as Dominant Social Force 50 Media Drive Culture 50

Summary & Review 51 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 53 ■ Key Terms 53

PART TWO

The Media

CHAPTER 3

Books and Magazines

55

History: The Printing Evolution 55 Early Print Media 55

The Gutenberg Revolution 57

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Goodbye, Gutenberg 58

The First American Print Media 59 Modern Magazines 63

YOUR MEDIA CAREER:

■ Wanted! Writers and Editors! 65

Book Publishing Giants 66

Technology Trends: From Chapbook To E-Book 67 After Gutenberg 67

Publishing in the Information Age 68 E-Publishing 68

TECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED:

■ Cuddling Up with a Nice Electronic Book? 69

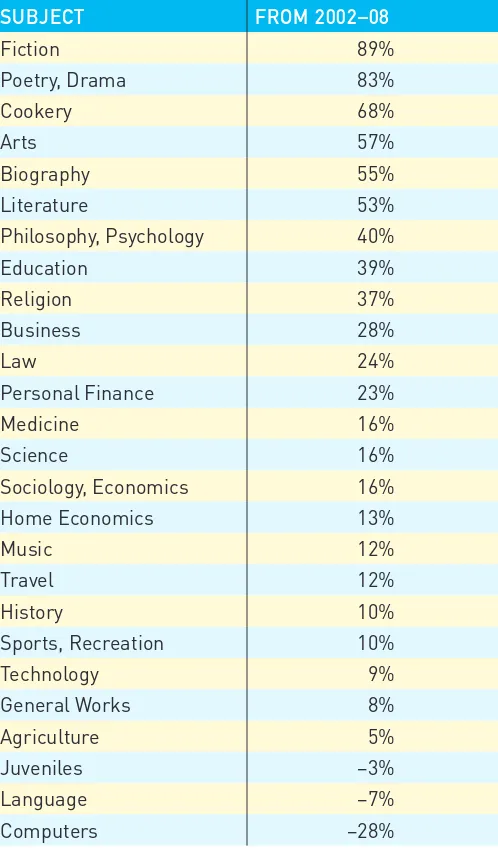

Industry: Going Global 71 Magazine Economics 71

Magazine Industry Proliferation and Consolidation 72 Magazine Circulation and Advertising 73

Magazine Distribution and Marketing 74 The Economics of Book Publishing 75 Book Publishing Houses 75

Bookstores—Physical and Online 75 Book Purchasers 76

What’s To Read? Magazine and Book Genres 77 Magazines for Every Taste 77

Book Publishing 78

MEDIA LITERACY:

■ The Culture of Print 80

Books as Ideas, Books as Commodities 80 Redefi ning the Role of Magazines 81 Intellectual Property and Copyright 81

Censorship, Freedom of Speech, and the First Amendment 82

Summary & Review 83 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 85 ■ Key Terms 85

AP Photo/Jeff R

C O N T E N T S

v i i

CHAPTER 4

Newspapers 87

History: Journalism in the Making 87Newspapers Emerge 87

The Colonial and Revolutionary Freedom Struggles 89 The First Amendment 89

Diversity in the Press 90 The Penny Press 91 Following the Frontier 92 War Coverage 92 The New Journalism 93 Yellow Journalism 94 Responsible Journalism 95 Muckraking 95

Newspapers Reach their Peak 96 Professional Journalism 96 Competing for the News 97 The Watchdogs 98

Newspapers in the Information Age 98

Technology Trends: Roll The Presses! 100 Newsgathering Trends 100

Convergence 101 Production Trends 101

Online and Mobile Newspapers 102 Industry: Freed From Chains? 104

The Newspaper Landscape 104

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Blogging the Elections 107

Chain Ownership and Conglomerates 110

TECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED:

■ Who’s Twittering Now? 110

Citizen News & Local Websites 111 Content: Turning The Pages 111

MEDIA LITERACY:

■ Responsible Reporting 113

Political Economy: Local Monopolies on The News 113 Freedom of Speech and the First Amendment 114 Ethics 114

Public’s Right To Know vs. Individual Privacy 116 Being A Good Watchdog 117

Defi ning News 118

YOUR MEDIA CAREER:

■ Twitter News Flash: See My Story Online! 119

Newspapers, Gatekeeping, and “Information Glut” 120

Summary & Review 121 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 123 ■ Key Terms 123

CHAPTER 5

Recorded Music

125

History: From Roots to Records 125 The Victrola 126

Early Recorded Music 126 Big Band and The Radio Days 126

Big Band Music and The World War II Generation 127 New Musical Genres 127

Rock History 128

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Black Music: Ripped off or Revered? 129

The Record Boom and Pop Music 130 The Rock Revolution will be Segmented 131 Digital Recording 132

Gar

y Hershorn/R

euters/Corbis

v i i i

C O N T E N T SMEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Resisting the March of (Recorded) Progress 133

Music on the Internet 134

Technology Trends: Let’s Make Music 135

TECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED:

■ From the Victrola to the CD 136

New Digital Formats 137 Downloading 139

Industry: The Suits 139 The Recording Industry 139

YOUR MEDIA CAREER:

■ Musicians, Moguls, Music in Everything Electronic 142

WORLD VIEW:

■ What are we Listening To? Genres of Music for Audience

Segments 144

MEDIA LITERACY:

■ Who Controls the Music? 145

Recorded Music in the Age of the New Media Giants 145 Sharing or Stealing? 146

Pity The Poor, Starving Artists 146

Getting Distributed Means Getting Creative 147 Music Censorship? 148

Global Impact of Pop Music Genres 148

Summary & Review 149 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 151 ■ Key Terms 151

CHAPTER 6

Radio 153

History: How Radio Began 153Save the Titanic: Wireless Telegraphy 153 Regulation of Radio 154

Broadcasting Begins 154

BBC, License Fees, and the Road Not Taken 156 Radio Networks 156

Paying for Programming: The Rise of Radio Networks 156 Radio Network Power 157

Competition From Television 157 Networks Fall, Disc Jockeys Rule 157 The FM Revolution 159

Local DJs Decline: A New Generation of Network Radio 159 New Genres: Alternative, Rap, and Hip-Hop Radio 160 Radio in the Digital Age 161

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Satellite Radio—With Freedom Comes Responsibility? 161

Technology Trends: Inside Your Radio 162 From Marconi’s Radio to Your Radio 162 High-Defi nition Radio 163

TECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED:

■ Fun with Electromagnetism? 163

Satellite Radio Technology 164 Internet Radio Technology 165

Weighing Your Digital Radio Options 165

Industry: Radio Stations and Groups 165 Radio in the Age of the New Media Giants 165 Inside Radio Stations 166

Non-Commercial Radio 167

Genres Around the Dial 168 Radio Formats 168

The Role of Radio Ratings 169 Music Genres and Radio Formats 170 Talk Radio 170

National Public Radio 172 Radio Programming Services 172

YOUR MEDIA CAREER:

■ Local DJs Decline but Other Forms of Radio Rise 172

Bennett R

aglin/Getty Images f

C O N T E N T S

i x

MEDIA LITERACY:■ The Impact of the Airwaves 173

Who Controls the Airwaves? 173

Concentrating Ownership, Reducing Diversity? 174 You Can’t Say that on the Radio 175

Breaking or Saving Internet Radio 176

Summary & Review 176 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 178 ■ Key Terms 179

CHAPTER 7

Film and Home Video

181

History: Golden Moments of Film 181

How to Use Images: Silent Films Set the Patterns 182 Setting up a System: Stars and Studios 183

How to use Sound: Look Who’s Talking 184 The Peak of Movie Impact? 185

The Studio System: The Pros and Cons of Vertical Integration 186

Coping with New Technology Competition: Film Faces Television, 1948–1960 187 Studios in Decline 188

Hollywood Meets HBO 190

YOUR MEDIA CAREER:

■ You Ought to Be in Pictures 191

Movies Go Digital 191

TECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED:

■ Entering the Third Dimension 193

Technology Trends: Making Movie Magic 193 Movie Sound 194

Special Effects 194 The Digital Revolution 195

TECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED:

■ You Ought to be Making Pictures 196

Movie Viewing 197

The Film Industry: Making Movies 198 The Players 198

Independent Filmmakers 198 The Guilds 199

Film Distribution 199 Telling Stories: Film Content 200

Team Effort 200

Finding Audience Segments 201

MEDIA LITERACY:

■ Film and your Society 203

Violence, Sex, Profanity, and Film Ratings 203 Viewer Ethics: Film Piracy 204

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Saving National Production or the New Cultural

Imperialism? 206

Summary & Review 207 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 208 ■ Key Terms 209

CHAPTER 8

Television 211

History: TV Milestones 211Television is Born 211 The Golden Age 212 Into the Wasteland 213

Television Goes to Washington 214

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Going by the Numbers 215

The Rise of Cable 216 The Big Three in Decline 217

Television in the Information Age 218

Technology Trends: From a Single Point of Light 220 Digital Television is Here 221

Courtesy

, LEGO® Star Wars; Lucasf

x

C O N T E N T STECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED:

■ Inside HDTV 222

Video Recording 223 Video Production Trends 224 Interactive TV? 224

3-DTV? 225

Industry: Who Runs the Show? 225 Inside the Big Five 225

Video Production 227

YOUR MEDIA CAREER:

■ Video Production 228

National Television Distribution 230 Local Television Distribution 232 Non-Commercial Stations 234 Television Advertisers 234 Genres: What’s On TV? 235

Broadcast Network Genres 235 What’s on Cable? 235

PBS Programming 237 Programming Strategies 237

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Diversity in Television 238

MEDIA LITERACY:

■ Out of the Wasteland? 239

The New Television Hegemony 239 Is Television Decent? 240

Children and Television 240

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Television and the Days of Our Lives? 241

Television Needs You! 242

Summary & Review 243 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 244 ■ Key Terms 245

CHAPTER 9

The Internet

247

History: Spinning the Web 247 The Web is Born 248 The Dot-Com Boom 250 Reining in the Net 250

Old Media in the Internet Age 252 The Rise of Social Media 252

Technology Trends: Following Moore’s Law 253 Computer Technology Trends 253

Network Technology Trends 255

TECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED:

■ Inside the Internet 256

Internet Trends 257

The Industry: David vs. Goliath 260 Computer Toy Makers 260 Where Microsoft Rules 260 Internet Service Providers 261 Content Providers 262 Internet Organizations 262

YOUR MEDIA CAREER:

■ Web Designer 263

Content: What’s on the Internet? 264 Electronic Publishing 264 Entertainment 265 Online Games 266 Portals 266 Search Engines 267

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Media, The Internet, and the Stories We Tell About

Ourselves 268

Internetkilledtv

C O N T E N T S

x i

Social Media 269Blogs 269

Electronic Commerce 269

What Makes A Good Web Page? 270

MEDIA LITERACY:

■ Getting the Most Out of the Internet 272

Does Information Want to be Free? 272 Closing the Digital Divide 273

Government: Hands off or Hands on? 274 Online Safety 276

Summary & Review 277 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 279 ■ Key Terms 279

CHAPTER 10

Public Relations

281

History: From Press Agentry to Public Relations 281 Civilization and its Public Relations 282

The American Way 283 The Timing was Right 283

PR Pioneers in the Modern World 284 Public Relations Matures 286

The New Millennium Meltdown 287 Global Public Relations 287

Technology Trends: Tools for Getting the Job Done 288 Traditional Tools 290

New Tools 290 Social Media 292 PR Databases 293

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Digital Social Media: Blogging is Bling! 293

Industry: Inside the Public Relations Profession 295 PR Agencies and Corporate Communications 295 Elements of Successful Public Relations 296 Professional Resources 296

Public Relations Functions and Forms 298 Public Relations Functions 298 The Publics of Public Relations 298 Four Models of Public Relations 300

MEDIA LITERACY:

■ Making Public Relations Ethical and Effective 300

Personal Ethics in the Profession 300 Crisis Communications Management 301 Private Interests vs. the Public Interest 303 Professional Development 303

YOUR MEDIA CAREER:

■ PR Jobs are in the Fast Lane 304

Use of Research and Evaluation 305

Summary & Review 305 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 307 ■ Key Terms 307

CHAPTER 11

Advertising 309

History: From Handbills to Web Links 309Advertising in America 310

The Rise of the Advertising Profession 310 The Rise of Broadcast Advertisers 311 Hard Sell vs. Soft Sell 312

The Era of Integrated Marketing Communication (IMC) 312

Advertising Everywhere 313

Technology: New Advertising Media 314 Advertising in Cyberspace 314

© AP Photo/Eric Ga

y

Adv

ertising Ar

chiv

x i i

C O N T E N T SMEDIA & CULTURE:

■ The Power of the Few: How College Students

Rule the Marketplace 315

Social Networking Sites: Advertisers’ New Frontier 316 They Have our Number 317

E-commerce 318

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Oprah: Talk Show or Marketing Vehicle? 319

More New Advertising Media 319

Inside the Advertising Industry 322 Advertisers 323

Inside the Advertising Agency 324 Advertising Media 326

Research 328

Advertising’s Forms of Persuasion 329 Mining Pop Culture 330

Consumer Generated Content 330 Relationship Marketing 330 Direct Marketing 331 Targeting the Market 332

Understanding Consumer Needs 332

The Changing Nature of the Consumer 335 Importance of Diversity 335

Global Advertising 336

MEDIA LITERACY:

■ Analyzing Advertising 336

Hidden Messages 336 Privacy 337

Deception 339

Children and Advertising 340

Summary & Review 341 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 342 ■ Key Terms 343

CHAPTER 12

The Third Screen: From Bell’s Phone to iPhone

345

History: Better Living Through Telecommunications 345 The New Media of Yesteryear 346

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ What My Cell Phone Means to Me 347

The Rise of MA Bell 347 The Telephone and Society 348 Cutting the Wires 349

The Government Steps Aside 350 The Third Screen Arrives 351

Technology Trends: Digital Wireless World 352

TECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED:

■ How Telephones Work 353

From Analog to Digital 353 Digital Networks 354

TECHNOLOGY

■ DEMYSTIFIED: Whistling Your Computer’s Tune, or How DSL Works 355 Mobile Networks 357

TECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED:

■ How Your Cell Phone Works 359

Industry: The Telecom Mosaic 361 The Wireline Industry 361 The Wireless Industry 363

YOUR MEDIA CAREER:

■ Mobile Media Star 364

Satellite Carriers 365

Content: There’s an App for Us 365 Wireless Apps 365

Location-Based Services 365 Wireline Apps 366

Image cop

yright Denisenko. Used under license fr

om Shutterstock

C O N T E N T S

x i i i

MEDIA LITERACY:■ Service for Everyone? 367

Set my Cell Phone Free! 367

Consumer Issues in Telecommunications 367 Whose Subsidies are Unfair? 368

Who Controls the Airwaves? 369 All of our Circuits Are. . .Destroyed 370 Big Brother is Listening 371

Privacy on the Line 371

Summary & Review 373 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 374 ■ Key Terms 374

PART THREE

Media Issues

CHAPTER 13

Video Games

377

History: Getting Game 377 Opening Play 377 Home Game 378

Personal Computers Get in the Game 379 Gear Wars 381

Games and Society: We Were not Amused 382 The New State of Play 383

The Next Level: Technology Trends 384 Generations 384

TECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED:

■ A Look Under the Hood at Game Engines 386

No More Consoles? 387 No More Controllers? 387 No More Screens? 387 No More Rules? 388

The Players: The Game Industry 389 Gear Makers 389

Game Publishers 390 Game Developers 391 Selling The Game 391

YOUR MEDIA CAREER:

■ Getting Paid to Play? 392

Rules of the Game: Video Game Genres 393

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Video Game as Interactive Film? 394

Beyond Barbie 396

MEDIA LITERACY:

■ Spoiling the Fun: Video Game Literacy 396

More Addictive Than Drugs? 396 More Harmful Than TV? 397 Serious Games? 399

Summary & Review 400 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 401 ■ Key Terms 401

CHAPTER 14

Media Uses and Impacts

403

Bashing the Media 403 Studying Media Impacts 404 Contrasting Approaches 405

Content Analysis 405 Experimental Research 407 Survey Research 409 Ethnographic Research 410

AP Photo/P

aul Sakuma

© Jason Hor

x i v

C O N T E N T STECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED:

■ The Science of Sampling 411

Theories of Media Usage 413 Uses and Gratifi cations 413

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ The Active Audience 414

Learning Media Behavior 415

Computer-Mediated Communication 416

Theories of Media Impacts 417 Media as Hypodermic Needle 418 The Multistep Flow 418

Selective Processes 418 Social Learning Theory 419 Cultivation Theory 419 Priming 420

Agenda Setting 420 Catharsis 420 Critical Theories 420

Media and Antisocial Behavior 421 Violence 421

Prejudice 423 Sexual Behavior 425 Drug Abuse 426

Communications Media and Prosocial Behavior 427 Information Campaigns 428

Informal Education 429 Formal Education 430

The Impacts of Advertising 430

The Impacts of Political Communication 433 Understanding Societal Impacts 434

Communications Media and Social Inequality 435 Media and Community 436

Health and Environment 437 Media and the Economy 438

Summary & Review 441 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 443 ■ Key Terms 443

CHAPTER 15

Media Policy and Law

445

Guiding the Media 445 Communications Policies 446

Freedom of Speech 446

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ George Carlin and the “Seven Dirty Words” 449

Protecting Privacy 451

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Consumer Privacy Tips and Rights 453

Protecting Intellectual Property 454 Ownership Issues 457

Universal Service 459

Who Owns the Spectrum? 460 Technical Standards 461 The Policy-Making Process 462

Federal Regulation and Policy Making 463 State and Local Regulation 466

Lobbies 467

The Fourth Estate 467

Summary & Review 469 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 470 ■ Key Terms 471

© P

C O N T E N T S

x v

CHAPTER 16

Media Ethics

473

Ethical Thinking 473 Ethical Principles 475

Thinking Through Ethical Problems: Potter’s Box 476

Codes of Ethics 477

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics Seek Truth

and Report it 478 Corporate Ethics 479 Making Ethics Work 480

Ethical Issues 481 Journalism Ethics 481 Ethical Entertainment 486 Public Relations Ethics 487

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ PR Ethics 488

Advertising Ethics 489

MEDIA & CULTURE:

■ Guidelines for Internet Advertising and Marketing 490

Research Ethics 493 Consumer Ethics 494

Summary & Review 496 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 497 ■ Key Terms 497

CHAPTER 17

Global Communications Media

499

Acting Globally, Regionally, and Nationally 499 Regionalization 501

Cultural Proximity 502 National Production 503 The Global Media 504

News Agencies 505 Radio Broadcasting 506 Music 506

Film 508 Video 510 Television 511

WORLD VIEW:

■ Soap Operas Around the World 514

Cable and Satellite TV 515 Telecommunications Systems 516 Computer Access 518

The Internet 520 International Regulation 521

TECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED:

■ A Closed or an Open Internet—The Great Firewall

of China 522

MEDIA LITERACY:

■ Whose World is it? 524

Political Economy of The Internet 524 Political Economy of Cultural Imperialism 525 Cultural Impact of Media and Information Flows 525 Free Flow of Information 526

Trade in Media 527

Media and National/Local Development 528

Summary & Review 529 ■ Thinking Critically About the Media 530 ■ Key Terms 531

Glossary 532 References 538 Index 550

© Starstock/Photoshot

© Ap Photo/K

P R E FAC E

x v i i

Now more than ever the long-predicted convergence of conventional mass media with new digital forms is changing the media landscape in ways that impact it and the plans of those who wish to enter media professions. A continuing world-wide economic slump challenges conventional media fi rms to keep up with new media and with burdens of debt that they incurred in more prosperous times. Our uses of media are evolving and our habits are changing as yesterday’s necessities become today’s luxuries. As travel and even a “night on the town” pinch our budgets, we spend more time with movies, video games, online enter-tainment, and cell phones. The Web seemingly pervades all aspects of the daily lives of our students, from how they research their term papers, listen to music and communicate with friends.

Our theme is that the convergence of traditional media industries and newer technologies has created a new communications environment that im-pacts society and culture. We are in the midst of another shift in media, and the transformation it is making to the culture we all share and the media in-dustries that refl ect it. Our goal throughout this book is to prepare students to cope with that environment as both critical consumers of media and aspiring media professionals.

We reach for that goal by providing an approach to mass media that in-tegrates traditional media (magazines, books, newspapers, music, radio, fi lm, and television) and newer media (cable, satellite, computer media, interactive television, the Internet, and cell phones), and emphasizes the intersection of technology, media, and culture.

We have witnessed astounding changes in the structure of the radio and telecommunications industries and the rapid evolution of the newspaper, movie, and television industries. These are changes that affect our society as well as those across the globe and our students need to learn about them in their introductory courses to prepare them to be productive citizens.

NEW TO THIS EDITION

x v i i i

P R E FAC Eplans while recognizing the cyclical nature of the economy and the impact that external events can have on providers of entertainment, information, and communication.

The changing media and economic environments are affecting the plans of our students and have introduced a new level of uncertainty about media careers. Accordingly, throughout this new edition of Media Now readers will fi nd authoritative information about the current status of media occupations and future projections drawn from the Occupational Outlook published by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Chapter by chapter, we examine the pay, pre-requisites, and perquisites of popular media careers and identify the factors affecting their growth over the next decade. Chapter by chapter, here are ex-amples of the updates you will fi nd in this edition:

The Changing Media

■ examines the fi nal stages of the transition to

digital media.

Media and Society

■ considers the new business models that are

emerg-ing in the digital media environment.

Books and Magazines

■ explains the latest trends in electronic

pub-lishing and the impact of e-books.

Newspapers

■ analyzes the career challenges that face aspiring journal-ists in a time of reorganization and change in the newspaper industry.

Recorded Music

■ tracks how the music industry is learning to live

with the Internet while abandoning their former strategy of prosecut-ing music downloaders.

Radio

■ Examines the Internet radio trend and its impact on conven-tional broadcasting.

Film and Home Video

■ looks at advances in 3D movie technology and

the softening of the DVD market.

Television

■ explores the implications of Comcast’s acquisition of NBC

television and continuing developments in Internet television.

The Internet

■ discovers Internet-related careers for students in media

programs and uncovers the latest trends in social media.

Public Relations

■ describes how social media present new

opportuni-ties for public relations professionals.

Advertising

■ tracks the implications of the social media phenomenon

in the advertising industry and offers reliable information about the prospects for employment in the industry.

The Third Screen

■ explores the development of fourth generation (4G) cell

phones and charts the genres of the growing array of smartphone apps.

Video Games

■ is a new chapter that analyzes the history, technology,

structure, and social impacts of this vibrant, new interactive medium and considers how media students might enter the industry.

Media Uses and Effects

■ updates research on the effects of

pornogra-phy, making friends on Facebook, and media violence.

Media Policy and Law

■ reports on the latest policies and court rulings

affecting indecency in the media and the future of broadband Internet development.

Media Ethics

■ offers analyses of current ethical issues in the media,

P R E FAC E

x i x

Global Communications Media■ examines instances of how digital

media are affecting media systems and culture around the world.

UPDATED PROVEN FEATURES

This book comes with a rich set of features to aid in learning, all of which have been updated as necessary:

Media Literacy:

■ Included within each media chapter, these sections

focuses on key issues regarding the impact of media on culture and soci-ety, encouraging students to think critically and analyze issues related to their consumption of media. In this edition, these sections have been expanded to include “news you can use” tips on how our readers can take practical actions that will empower them as media consumers.

Glossary:

■ Key terms are defi ned in the margins of each chapter, and a complete glossary is included in the back of the book.

Timelines:

■ Major events in each media industry are highlighted near

the beginning of each chapter in Media Then/Media Now lists.

Box program:

■ Four types of boxes appear in the text. Each is designed

to target specifi c issues and further pique students’ interest and many are new to this edition:

MEDIAAND CULTURE

■ boxes highlight cultural issues in the media.

TECHNOLOGY DEMYSTIFIED

■ boxes explain technological information

in a clear and accessible way.

Y

■ OUR MEDIA CAREER (see above) is a new feature that guides readers

to the “hot spots” in media industries.

Stop & Review:

■ Appearing periodically throughout each chapter, and

available in electronic format on the Media Now companion website, these questions help students incrementally assess their understand-ing of key material.

Summary & Review:

■ Each chapter concludes with the authors’ highly

praised, engaging summary and review sections, which are presented as questions with brief narrative answers.

TEACHING AND LEARNING RESOURCES

Mass Communication CourseMate for Media Now: This new multi-media resource offers a variety of rich learning materials designed to enhance the student experience. This resource includes quizzing and chapter-specifi c resources such as chapter outlines, interactive glossaries and timelines, Stop & Review tuto-rial questions, and Critical Thinking About the Media exercises. You will also fi nd an Interactive eBook. Use the “Engagement Tracker” tracking tools to see progress for the class as a whole or for individual students. Identify students at risk early in the course. Uncover which concepts are most diffi cult for your class. Monitor time on task. Keep your students engaged.

Note to faculty:

■ If you want your students to have access to these

x x

P R E FAC Eto your students with every new copy of the text. If you do not order them, your students will not have access to these online resources. Contact your local Cengage Learning sales representative for more details.

CLASS PREPARATION, ASSESSMENT, AND COURSE

MANAGEMENT RESOURCES

Instructor’s Resource Manual: Media Now’s Instructor’s Resource Manual

pro-vides you with extensive assistance in teaching with the book. It includes sam-ple syllabi, assignments, chapter outlines, individual and group activities, test questions, links to video resources and websites, and more.

PowerLecture with JoinIn

■ ® CD-ROM: This all-in-one lecture tool lets you bring together text-specifi c lecture outlines and art from Cen-gage Learning texts, along with video and animations from the Internet or your own materials—culminating in a powerful, personalized media-enhanced presentation. In addition, the CD-ROM contains ExamView® computerized testing, and an electronic version of the book’s Instruc-tor’s Resource Manual. It also includes book-specifi c JoinIn™ content for response systems tailored to Media Now, allowing you to transform your classroom and assess your students’ progress with instant in-class quizzes and polls. Our exclusive agreement to offer TurningPoint soft-ware lets you pose book-specifi c questions and display students’ answers seamlessly within the Microsoft PowerPoint slides of your own lecture, in conjunction with the “clicker” hardware of your choice. Enhance how your students interact with you, your lecture, and each other.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank our spouses, Sandy Straubhaar, Betty Degesie-LaRose, and Frederic Greene for their patience and valuable ideas. We also want to thank a number of our students and graduate assistants, Julie Goldsmith, Nicholas Robinson, Tim Penning, and Serena Carpenter for their reviews and comments on the chapters. Also, thanks to Rolf and Chris Straubhaar, Julia Mitschke, and to Rachael and Jason Davenport Greene for insights into their culture and concerns. Special thanks to Dr. Alex Games, Dr. Wei Peng, and Tammy Lin, all of the Department of Telecommunications, Information Studies, and Media at Michigan State University, for reviewing drafts of the new video games chapter.

P R E FAC E

x x i

We also gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the guest writer of our advertising chapter, Teresa Mastin of Northwestern University. Dr. Mastin earned her master’s degree from California State–Fullerton and her doctorate in mass media from Michigan State University. She has more than 10 years ex-perience teaching advertising and public relations, most recently at Michigan State University. We thank Jeffrey South, Virginia Commonwealth University for writing the Instructor’s Resource Manual and Examview quizzes, and As-sem Nasr, University of Texas, Austin for working on the JoinIn resources.

Finally, we wish to thank the following reviewers for their thoughtful sug-gestions and guidance in the development of the seventh edition:

Charles Lewis, Minnesota State University, Mankato

Ben Peruso, Lehigh Carbon Community College

Karyn S. Campbell, North Greenville University

Dr. Jim Eggensperger, Iona College

Arthur A. Raney, Florida State University

Alden L. Weight, Arizona State University, Polytechnic Campus

Dr. Jim Brancato, Cedar Crest College

Robert Darden, Baylor University

x x i i

P R E FAC EA B O U T T H E AU T H O R S

x x i i i

DR. JOSEPH D. STRAUBHAAR is the Amon G. Carter CentennialPro-fessor of Communications and Graduate Studies Director in the Radio-TV-Film Department of the University of Texas at Austin. He was the Director of the Center for Brazilian Studies within the Lozano Long Institute for Latin American Studies. He is also Associate Director for International Programs of the Telecommunication and Information Policy Institute at the University of Texas. He has published books, articles, and essays on international communi-cations, global media, international telecommunicommuni-cations, Brazilian television, Latin American media, comparative analyses of new television technologies, media fl ow and culture, and other topics appearing in a number of journals, edited books, and elsewhere. His primary teaching, research, and writing in-terests are in global media, international communication and cultural theory, the digital divide in the U.S. and other countries, and comparative analysis of new technologies. He does research in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, and has taken student groups to Latin America and Asia. He has presented seminars abroad on media research, television programming strategies, and telecommu-nications privatization. He is on the editorial board for the Howard Journal of Communications, Studies in Latin American Popular Culture, and Revista Intercom.

Visit Joe Straubhaar on the Web at

http://rtf.utexas.edu/faculty/jstraubhaar.html

DR. ROBERT LAROSE is a Full Professor in the Department of

Telecom-munication, Information Studies, and Media at Michigan State University. He was recently recognized for his research productivity as an “Outstanding Re-searcher” by the College of Communication Arts and Sciences at MSU. He con-ducts research on the uses and effects of the Internet. He has published and presented numerous articles, essays, and book chapters on computer-mediated communication, social cognitive explanations of the Internet and its effects on behavior, understanding Internet usage, privacy, and more. In addition to his teaching and research, he is an avid watercolor painter and traveler.

Visit Robert LaRose on the Web at

http://www.msu.edu/~larose

x x i v

A B O U T T H E AU T H O R Sethics. She is on editorial boards of journals, and her research has been pub-lished and presented in conference papers, journal articles, and books. She has professional experience in newspaper, television, public relations, advertising, and online news. Her credentials include a Ph.D. in Mass Communication, a M.A. in Journalism, and a B.A. double major in Journalism and Radio/TV/ Film. Her master’s thesis and doctoral dissertation were fi rst in the country on computerized information services and online news.

Visit Lucinda D. Davenport on the Web at

NEWSPAPER TO IPAD

. . . broadcast TV to

Jim W

ilson/The New Y

ork Times/R

edux Pictur

es

1

THE MEDIA IN OUR LIVES

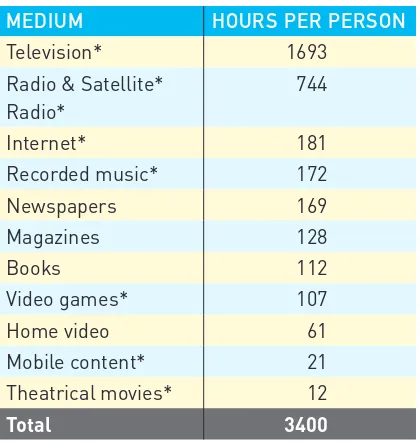

If you were the typical American media consumer, then you would spend over nine and a quarter hours a day with the media! Multiply that by the num-ber of days in a year, and you would spend almost fi ve months of each year with media (see Table 1.1). Since this is the information age we can break that down into the bits and bytes of computer data. It adds up to 34 billion bytes a day per person, or about a third of the capacity of a 100 GB computer hard drive (Bohn & Short, 2009).

We consume information, but we also make it. Students blog, upload vid-eos to YouTube, contribute to MySpace and Facebook, and control avatars in multiplayer online games like “World of Warcraft.” Most of the workers in the United States gather, organize, produce, or distribute information. That in-cludes professional information specialists employed in the media as journal-ists, movie actors, musicians, television producers, writers, advertising account executives, researchers, Web page designers, announcers, and public relations

THE

4

PA RT 1|

M E D I A A N D T H E I N F O R M AT I O N AG EMEDIA

NOW

MEDIA THEN

1455 Gutenberg Bible is published

1910 United States transitions to an industrial society

1960 United States transitions to information society

1991 World Wide Web begins

1996 Telecommunications Act of 1996 reforms U.S. media policy

2009 United States adopts digital TV

specialists. Even in traditional manufacturing industries such as the auto in-dustry, information-handling professionals in managerial, technical, clerical, sales, and service occupations make up a third of the workforce (Aoyama & Castells, 2002). So, we now work and play in an information society.

MEDIA IN A CHANGING WORLD

Media technology changes with every generation: For example, Mr. McQuitty, who is 45 years old, is a television producer. When he was in a college mass communication survey course, our fi ctional Mr. McQuitty studied books, news-papers, magazines, radio, television, and fi lm. Today, these conventional media have evolved through the advent of digital technology. Mr. McQuitty’s daughter, Rachael, wants to start her own online channel. She takes some of her college courses on campus and some online and downloads her textbooks from the Inter-net. Her world revolves around iPods, texting, Facebook, YouTube, and Xbox.

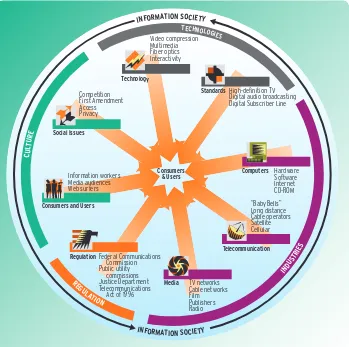

Conventional media forms are combining with new ones in ways that change our media consumption patterns, our lives, and the societies in which we live. Anyone who has ever used a cell phone to download an e-mail, vote for an American Idol contestant, view a video clip, or listen to a song has experienced the merging of conventional mass media into new media forms through advances in digital technology and telecommunications networks. New media technologies impact our culture by offering new lifestyles, creating new jobs and eliminating others, shifting media empires, demanding new regulations, and presenting unique new social issues (see Figure 1.1).

The changes are not purely technology-driven, however. Our individual creativity and our cultures push back against the technologies and the corporations that deploy them to redefine their uses. Big media corporations now contend with citizen journalists, Facebook networks, garage bands, and amateur video producers on the Internet. Meanwhile, world trade agreements and global digital networks force American media institutions like CNN to compete with the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and Middle East-ern news sources like Al Jazeera.

In an information society, the exchange of information is the predominant economic formatted in 1s and 0s.

TABLE 1.1 ANNUAL MEDIA CONSUMPTION MEDIUM HOURS PER PERSON

*Age 12+, all others 18+.

C H A P T E R 1

|

T H E C H A N G I N G M E D I A5

MERGING TECHNOLOGIES

There are not many forms of purely analog communication still in common use today. We still experience purely analog communication when we are in a room with another person listening to what they say and looking at the expression on their face. Handwritten notes are another example, but only for those who don’t text or Twitter. In a short span of years technology has moved us away from analog communication and into the digital age in which nearly all other forms of communication are either created, stored, or transmitted in digital form.

The digital domain now encompasses nearly all radio, television, film, newspapers, magazines, and books with an ever-narrowing list of exceptions. Local talk radio is about the only purely analog medium that remains—local music radio stations still transmit analog signals but they play music that is stored on digital recordings. To catch up with the times the “old media” have responded with digital innovations of their own. The music industry increas-ingly relies on digital distribution through iTunes and other digital music ser-vices after facing ruin from free-but-illegal Internet downloads. Now exciting new digital media forms have emerged, ranging from video games to social networking to texting.

Analog communication uses continuously varying signals corresponding to the light or sounds originated by the source.

FIGURE 1.1 MEDIA CONVERGENCE Information technology and media are converging in

6

PA RT 1|

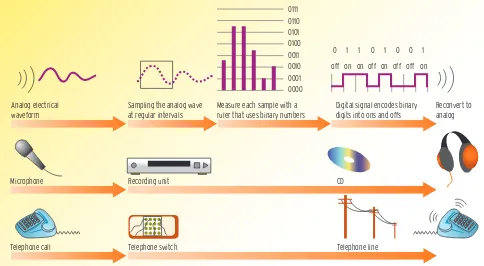

M E D I A A N D T H E I N F O R M AT I O N AG EDigital communication technology converts sound, pictures, and text into computer-readable formats by changing the information into strings of binary digits (bits) made up of electronically encoded 1s and 0s (see Technology De-mystifi ed: A Digital Media Primer, above). People using a telephone today still hear a “W” phonetic sound just like people did a hundred years ago, but only after the phone converts the analog sound to digital pulses and then changes it back to sound for reception by humans (see Figure 1.2). Computers recog-nize a “W” in the encoded bits of 1010111 when you press the W key on the keyboard. A particularly useful quality of digital information is that many different sources can be combined in a single transmission medium so that formerly distinct channels of communication, such as telephone and televi-sion, can be integrated in a common digital medium, such as the Internet or a DVD.

A channel is an electronic or mechanical system that links the source to the receiver.

TECHNOLOGY

DEMYSTIFIED

A DIGITAL MEDIA PRIMER

binary number is 00000000. If the lovers begin to quarrel loudly, the voltage reading might jump to the maximum: 11111111. To the couple, it seems that they are talking to each other, but in reality they are listening to computer emulations of their voices. Digital record-ings use the same methods, but they employ more numerous samples and allow more volume levels to improve sound quality.

To make computer graphics, a computer stores digital information about the brightness and color of every single point on the computer screen. On many computer screens, there are 1024 points of light (or picture elements, pixels for short) going across and 768 down. Up to 24 bits of information may be re-quired for each point so that millions of colors can each be assigned their own unique digital code.

Similarly, when we type text into a computer, each key corresponds to a unique sequence of eight com-puter bits (such as 1000001 for A). These sequences are what is stored inside the computer or transmit-ted through the Internet, in the form of tiny surges of electricity, fl ashes of light, or pulses of magnetism. The human senses are purely analog systems, so for humans to receive the message, we must convert back from digital to analog.

All digital transmissions are composed of only two digits: 1 and 0. These are actually a series of on (for 1s)–off (for 0s) events. These can be encoded in a va-riety of ways including turning electrical currents or light beams on and off in Internet connections, chang-ing the polarity of tiny magnets on the surface of a computer hard drive, or patterns of pits on the sur-face of a CD.

Consider a simple landline telephone call. The digital conversion occurs on a computer card that connects your line to the telephone company’s switch. First, brief excerpts, or samples, of the electrical waveform corresponding to your voice are taken from the tele-phone line at a rate of 8,000 samples per second. The size, or voltage level, of each sample is measured and “rounded off” to the closest of 256 different possible readings. Then a corresponding eight-digit binary num-ber is transmitted by turning an electrical current on for a moment to indicate a 1 and turning it off for a 0.

C H A P T E R 1

|

T H E C H A N G I N G M E D I A7

DIGITAL MEDIA Avatar raised digital fi lm production to a new level and re-introduced 3D technology to a wide audience.

0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 Analog electrical

waveform

Sampling the analog wave at regular intervals

Measure each sample with a ruler that uses binary numbers

Digital signal encodes binary digits into ons and offs

Reconvert to analog off on on off on off off on

Microphone Telephone call

Recording unit Telephone switch

CD Telephone line 0111

0110 0101 0100 0011 0010 0001 0000

FIGURE 1.2 CONVERTING ANALOG TO DIGITAL The analog-to-digital conversion process occurs in a variety of media.

© Cengage Learning

8

PA RT 1|

M E D I A A N D T H E I N F O R M AT I O N AG ECHANGING INDUSTRIES

A convergence trend continues to propel the transformation of conventional media to new digital forms (see Figure 1.1, page 5), although the forces behind this trend are shifting. In the 1990s, conventional media fi rms tried to domi-nate new media. Cable television and publishing giant Time-Warner merged with America Online, then the largest Internet provider. News Corporation, owner of the Fox Network, bought MySpace.com. Rival old-media conglom-erates Disney Corporation, National Amusements (owner of Viacom cable networks and CBS Television), and NBC Universal (a subsidiary of General Electric) likewise positioned themselves to make, distribute, and exhibit con-tent across the Internet as well as by print, radio, recorded music, television, and fi lm.

However, few of these combinations proved successful and media con-glomerates came undone. AOL Time Warner went back to calling itself Time Warner and later separated its cable systems from its media opera-tions and spun off AOL. New media companies seized the initiative from the old. Apple made itself into the most powerful player in the recorded music industry with iTunes, rocked the telephone industry with the iPhone, and is shaking up print media with the iPad. Google emerged as the largest adver-tising medium, and TiVo’s digital video recorders sent tremors through the TV industry.

Following an economic crisis that began in 2007, debt-laden media deals failed as loans came due and fi nancing dried up. Advertising revenues and media stocks slumped followed by a collapse in demand for consumer products. No industry was hit harder than newspapers. The number of two- newspaper cities dwindled and other daily papers cut back on the number of days they made home deliveries or became exclusively online publications. Charter Communications, the fourth-largest cable company in the United States, fi led for bankruptcy, as did the second-largest radio ownership group, Cita-del Broadcasting. Billionaire Sumner Redstone, owner of CBS Television and

Viacom, was forced to sell video game maker Midway Games at a huge loss to help bail himself out of debt. Cable television giant Comcast Cablevision snapped up NBC Universal as rev-enues from its fl agship NBC television network plummeted.

Changing industries also mean challenging careers for those enter-ing media professions. (see Your Media Career: Room at the Bottom, Room at the Top, p. 9).

CHANGING LIFESTYLES

When new media enter our lives, me-dia consumption patterns evolve. Four-fi fths of Internet users now watch video online in a month, averaging about 10

FUTURE TV Many consumers are moving to Digital TV because it promises wider

and better pictures, improved sound, more channels, and interactivity.

Justin Pumfrey/T

axi/Getty Images

C H A P T E R 1

|

T H E C H A N G I N G M E D I A9

ROOM AT THE BOTTOM, ROOM AT THE TOP

YOUR MEDIA

CAREER

The rewards of top-echelon media careers are well publicized: multimillion-dollar salaries, hobnobbing with the rich and famous, globe-hopping lifestyles. Only a few make it to the level of a Diane Sawyer, a Steven Spielberg, a Bob Woodward, or a Howard Stern from among the tens of thousands who enter the media industry each year from courses like the one you are taking now. Still, fulfi lling pro-fessional success can be attained in less visible media oc-cupations, either behind the scenes of global productions or in local markets, where the rewards may come from creative self-expression or from the satisfying feeling of “making a difference.”

The challenges of media careers are many. It is often said that media industries “eat their young.” Some young col-lege graduates never move beyond internships, often un-paid ones, or entry-level “go-for” positions. Making the jump to steady professional employment sometimes depends on

things we do not learn in college, such as having family con-nections or being born with basic creative talent. Those who progress beyond the entry level may leave after “burning out” on the workload or fi nding that competitive pressure from yet newer waves of eager college graduates keeps both entry- and mid-level salaries relatively low.

Yet, the media want you. Some media industries, notably music, television, advertising, and fi lm, feed on the creative energies of young professionals who give them insights into young consumers. That means positions are continually opening up at all levels and talented and well-connected graduates can rise rapidly through the ranks. However, it is also possible to be “washed up” at age 30.

Convergence makes media-related careers highly vola-tile. Whenever you read about a media merger or a new form of digital media production or distribution it means that dozens, if not hundreds, of existing media jobs may hours of viewing monthly (comScore,

2009). Three-fourths of Internet users visited the Internet for politi-cal purposes during the 2008 elections (Pew Research Center, 2009). Top video games like “Call of Duty” make as much money as top movies like Iron Man 2.

A lifestyle change among the college-age population makes media executives take notice: young adults are no longer easily reached by con-ventional mass media. They spend so much time juggling their iPods, cell phones, and video games (often simultaneously) and participating in online communities such as Facebook that there is little time or interest

left for newspapers or television. That’s why the old media run websites to sustain interest in Survivor, create “buzz” for new movies, or add live dis-cussion forums to printed stories. It’s also why media and advertisers look for new ways to recapture the young adult audience, such as making TV showsavailable online and inserting ads into video games.

CHANGING CAREERS Online news sources are part of the reason newsrooms are

emptying out or being sold out in distressed sales.

1 0

PA RT 1|

M E D I A A N D T H E I N F O R M AT I O N AG ENew media introduce us to alternative ways to live, as millions of people now work, shop, seek health information, and pursue their hobbies online (Pew Research Center, 2006a). Others forge new identities (Turkle, 1995), develop new cultures (Lévy, 2001), and fi nd information to make personal decisions online. However, the new media may also dis-place close human relationships with superficial ones online (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Brashears, 2006), lower the quality of public discourse by substituting Internet rumors for professional journalism, or drag popu-lar culture to new lows.

SHIFTING REGULATIONS

With the Telecommunications Act of 1996, Congress stripped away regulations that protected publish-ing, broadcastpublish-ing, cable and satel-lite television, telephone, and other media companies from compet-ing with one another. Lawmakers had hoped to spark competition, improve service, and lower prices in The Telecommunications Actof 1996 is federal legislation that deregulated the communications media.

MEDIA EFFECT Mass killings like those at Fort Hood, Texas raise concerns about

the effects of the Internet. In this case, the killer contacted radical groups online.

AP Images/Sipa

disappear. In the short term, the challenge will be starting a media career. The Great Recession of 2007–2009 made entry into mass-media fields more difficult than usual (Vlad et al., 2009).

Most people entering the workforce today will have four or fi ve different careers regardless of the fi eld they enter and that is also true of media careers. When we say “different careers,” we don’t mean working your way up through a progression of related jobs inside an industry, say, from the mailroom at NBC Television to vice presi-dent for Network Programming at CBS. For many of our readers it will mean starting out in a media industry but retraining to enter health care, education, or computer careers where employment is expected to grow the fast-est over the next decade. To assess your options you can visit the Occupational Outlook Handbook (http://www.bls. gov/OCO/), an authoritative source of information about the training and education needed, earnings, expected job prospects, what workers do on the job, and working conditions for a wide variety of media occupations. Or, keep reading. In each chapter you will fi nd features about media careers in related fi elds.

C H A P T E R 1

|

T H E C H A N G I N G M E D I A1 1

all communications media. Unfortunately, the flurry of corporate mergers, buyouts, and bankruptcies has outpaced consumer benefi ts.

Another information-age legislation, the Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998, has perhaps had a more immediate impact on media consumers. This legislation broadened the copyright protection enjoyed by writers, perform-ers, songwritperform-ers, and the giant media corporations that own the rights to such valued properties as Bugs Bunny. However, other legislation weakens the rights of students and professors to reproduce copyrighted printed works for non-commercial, educational use. It also cracks down on students and other individuals who “share” music and videos online.

Vital consumer interests are also at stake in the battle over net neutrality. The outcome will determine whether Internet providers will re-main neutral in handling information on the Internet or whether they will win the right to favor certain types of information over others. With that right would come the ability to prioritize content created by their corporate part-ners and to charge their competitors extra, charges that would be passed on to consumers.

RISING SOCIAL ISSUES

The media themselves have long been social issues. Television is often sin-gled out for the sheer amount of time that impressionable youngsters spend watching it. Children ages 2–5 average 32 hours a week in front of the tele-vision screen (McDonough, 2009), including the time they spend watching programs recorded on digital video recorders and DVDs. Television has been criticized for its impacts on sexual promiscuity, racial and ethnic stereotypes, sexism, economic exploitation, mindless consumption, childhood obesity, smoking, drinking, and political apathy. The impact of television on violence is an enduring concern of parents and policy makers alike. By the time the average child fi nishes elementary school, he or she has seen 8,000 murders on TV. By high school graduation, that number will have escalated to 40,000 murders and 200,000 other acts of violence (TV-Free, n.d.), and that does not include fi lm or video games or any of the “beat downs” they may see on YouTube.

New media are fast replacing television as the number one concern about media effects. The interactive nature of new media may make them more potent than conventional forms. Some researchers believe that video games have much greater effects on violent behavior than old media and are nearly as powerful inducements to violence as participation in street gangs (Anderson et al., 2006). New media have also made it possible for children to turn into producers of problematic content,

in-cluding videos of middle school beat downs posted on YouTube and exchanges of self-posed child por-nography exchanged as cell phone text messages. Internet critics also worry that although many use the Internet to engage in positive social interaction and to seek out diverse political viewpoints, it may prompt others to live isolated lives in front of the computer screen or to affi liate with terror groups on-line. Finally, does the spread of the Internet create

Copyright is the legal right to control intellectual property

Net neutrality means users are not discriminated against based on the amount or nature of the data they transfer on the Internet.

STOP

&

REVIEW

1. List four examples of the convergence phenomenon.

2. What is meant by the term information society?

3. What are three conventional mass media?

4. What is the difference between analog and digital?

1 2

PA RT 1|

M E D I A A N D T H E I N F O R M AT I O N AG Ea digital divide that creates a new underclass of citizens who do not enjoy equal access to the latest technology and the growing array of public ser-vices available online (See Media and Culture, A New Balance of Power?, above)?

CHANGING MEDIA THROUGHOUT HISTORY

Although the changes in the media, and the changes in society that accompany them, may sometimes appear to be radically new and different, the media and society have always adapted to one another. In this section we examine how the role of the media has evolved as society developed—and vice versa—from the dawn of human civilization (see Figure 1.3, page 13) through agricultural, industrial, and information societies (Bell, 1973; Dizard, 1997; Sloan, 2005). The digital divide is the gap

in Internet usage between rich and poor, Anglos and minorities.

MEDIA

&

CULTURE

Just how powerful are the media? Do they affect the very underpinnings of the social order, such as who holds power in society and how they keep it?

The new media can put us all at the mercy of “digi-tal robber barons” like Steve Jobs of Apple who rule them to enrich themselves at our expense. Their dominance reduces the diversity of content and raises the cost of information. For example, Apple maintains control over the applications (“apps” for short) that are allowed on its iPhone. Innova-tive apps developed by entrepreneurs that might save consumers money on music and phone costs, but that would diminish the profits from Apple’s iTunes or from the cell phone business operated by their partner AT&T, are not allowed. Meanwhile, old media interests like Disney and Time Warner sue peer-to-peer fi le sharing services on the Internet like LimeWire to protect their property rights. We might well ask, Is the information society just a new way for the rich to get richer?

Or, do the new media consign the poor to continu-ing poverty? The digital divide describes the gap in Internet access between whites and minorities, rich and poor (NTIA, 2002). As the Internet grows into an important source of employment, education, and political participation, that digital divide could

translate into widening class division and social up-heaval. Equal opportunity in the information economy already lags for both minorities and women, who are underrepresented in both the most visible (that is, on-camera) and most powerful (that is, senior ex-ecutive) positions in the media. And although the gap in Internet access for women has closed, women are still excluded from a male-dominated computer culture, which denies them access to the most pow-erful and rewarding careers in the information soci-ety (AAUW, 2000). The issue is global. The nations of the world are divided between those with access to advanced communication technology and those without it.

Or, could the new media be a catalyst for a shift away from traditional ruling classes? An alliance of social movements against the excesses of global corporations orchestrates demonstrations via the Internet. Blogs raise issues that are ignored by the mainstream press. The diverse and lively communities of the Internet may contribute to the fragmentation of culture and power—for many, identity is defi ned as much by the Internet communities in which we par-ticipate as by the countries we live in or the color of our skin, characteristics that are invisible on the Internet.

C H A P T E R 1

|

T H E C H A N G I N G M E D I A1 3

PREAGRICULTURAL SOCIETY

Before agricultural societies developed, most people lived in small groups as hunters of animals and gatherers of plants. These cultures depended on the spoken word to transmit ideas among themselves and between generations. Shamans and storytellers spread the news. The oral tradition is an extremely rich one, bringing to us Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and the epic stories, folk-tales, ritual chants, and songs of many other cultures. These works that origi-nated in oral forms live on today in the fairy tales and campfi re stories that we tell our children.

AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY

Once agricultural society developed, most work was found on farms or in re-source extraction, such as mining, fi shing, and logging. Agricultural societies were more settled and more complex than preagricultural societies. It was the ancient Sumerian culture, located in modern-day Iraq, that is commonly cred-ited with developing writing in 3100 BCE. The Greco-Roman method of writing developed into our present-day alphabet.

In early civilizations literacy was common only among priests and the up-per classes. In some cultures literacy was intentionally limited, because the ruling class wanted to keep the masses ignorant and away from new ideas. Reproduction of printed works was painstaking. Christian monks copied books by hand. The Chinese developed printing with a press that used carved wooden blocks, paper, and ink. With much of the populace still illiterate, couriers skilled at memorizing long oral messages were valuable communications specialists.

INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY

Although the beginning of the Industrial Revolution is often dated to correspond with Thomas Newcomen’s invention of the steam engine in 1712, an important precursor of industrialism is found in the fi eld of communication: the printing

Information services Manufacturing

Mass media Agriculture Agriculture

Information Revolution

Mass media Manufacturing

Mode of employment is agriculture

Folk media Cottage industry

Mode of employment is information creation and processing

Information society

Mode of employment is manufacturing

Industrial society Agricultural society

Industrial Revolution

4000 B.C.E. 1712 C.E. 1960 C.E.

FIGURE 1.3 STAGES OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT The three basic stages of economic development, from agricultural to