i

STUDENTS’ PERCEPTION OF TEACHER FEEDBACK ON

THEIR ACADEMIC WRITING AS REFLECTED IN THEIR

REVISION

Presented as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Magister Humaniora (M.Hum) Degree

in English Language Studies

By

Niswatin Faoziah

Student Number: 056332001

THE GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDIES SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

iii

v

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First of all I would like to thank “Al Mighty ALLAH” and our prophet Muhammad for the universal love that led me to accomplish this thesis. Indeed, writing thesis has seemed to be a struggle, determined head battle on paper, and “God be pleased”, finally I have completed it.

I also express my gratitude to my adviser, Pak F.X. Mukarto who has provided advice and supportive guidance and largerly contributed to the elaboration and completion of this work. He has proved to be a patient and cooperative adviser without whom this work would have never come into being. I have learned a great deal from him, and no words of thanks are really adequate. So the improvement in this work is the result of his guidance, while all errors and mistakes are mine.

My appreciation goes to Pak Bismoko, Pak Dwijatmoko, and Pak Alip for their careful reading and excellent suggestions that were very important to the implementation of my thesis.

My special thanks go to all participants in the research whose work and ideas were generously shared and directly reflected in this study. I am also grateful to the teacher whose expert teaching and the accessibility contributes to the content of my study.

My sincere thanks go to Ibu Merrian, Pak Simon Rae, and Slash, my watchful editor, who has offered invaluable suggestions, slowed me down, and kept me on track.

I would also like to thank all administrators, all lecturers, and students in in English language studies at Sanata Dharma university,(mbak Jeannete, mbak Retno, mbak Ista, mbak Irma, mbak Yanti, Diah for the discussion and sharing.

vi

5. Research Examining Students’ Perceptio ns of Teacher Feedback.…… … 45

vii

A. Data Analysis and Presentation……… 77

1. Analysis of students’ Document ……… 78

2. Constructing Interview Questions ………. 80

3. Conducting Interviews ……… 81

4. Managing Interview Data ……… 82

B. Findin gs ……… ………… 85

1. A Personal Portrait of Students’ Perceptions of Teacher Feedback ……… 87

a. Personal Portrait of Neina ………. ……… 88

1). Educational Background and Writing Experience……... 88

2). Problem Solving……….…………. 89

2). Understanding of Grammatical Symbols………. 139

viii 3. Individual Perceptions of Teacher Feedback on Student

Academic Writing as Reflected in Revision ……… 152

a. How Neina’s Perception of Teacher Feedback Shaped her Revision ……… 153

b. How Mosez’s Perception of Teacher Feedback Shaped his Revision ……….. 158

c. How Laila’s Perception of Teacher Feedback Shaped her Revision ……… 161

C. Discussion……… 165

CHAPTER V CONCLUSION……… 174

A. Conclusio n……….. 174

B. Implicatio n ………. 176

C. Recommendation ………... 178

BIBLIOGRAPHY ………... 179

APPENDICES ……….. 187

Appendix A: List of guiding question for students’ interview…….. ………... 188

Appendix B: Coding Students’ Account ……… .. 190

Appendix C: Teacher’ s Structured Interview Transcriptions………. 217

ix

LIST OF FIGURES

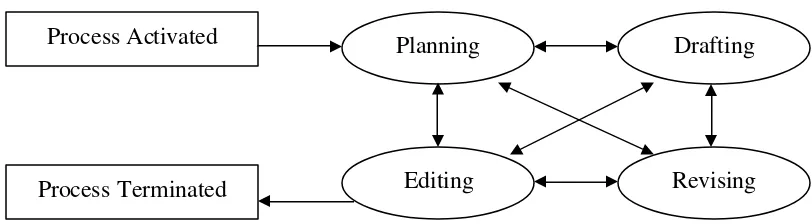

Figure 2.1. Stages in The Writing Process ……… … 17

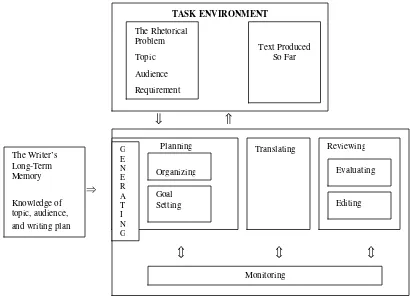

Figure 2.2. The Hayes-Flower Writing Process Model ……….. 19

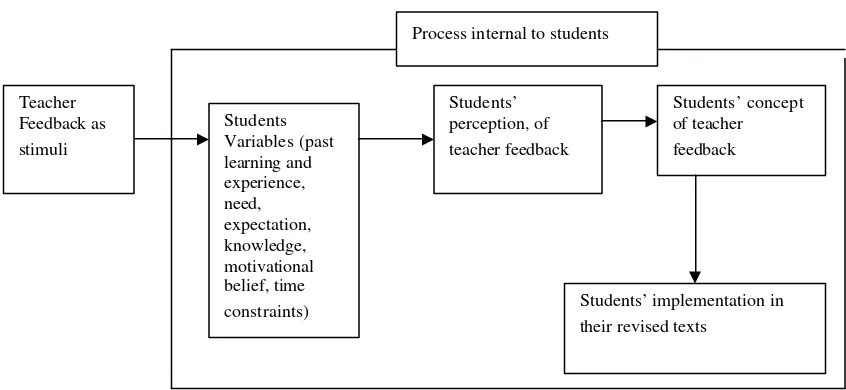

Figure 2.3. The Schema of Students’ Perception of Teacher Feedback As Reflected in Their Revised Work ………. 52

Figure 3.1. Sample of Student Writing………. 65

Figure 3.2. Looking at Students’ Perception of Teacher Feedback As Reflected in Their Revised Work from Different Sides and Sources……….. 66

Figure 3.3. Data Collectio n Processes ……… 72

Figure 3.4. Interactive Technique of Data Analysis ……….. 74

Figure 3.5. Triangulation of the Three Different Varieties of Data Sources ……… 76

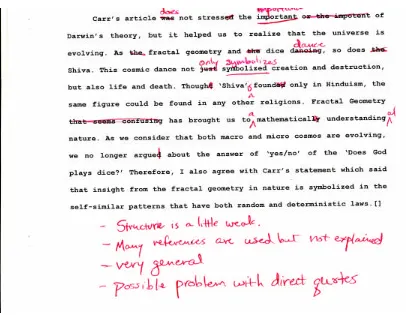

Figure 4.1. A Sample of Neina’s Writing……….. 79

Figure 4.2. Neina’s First Draft……….. 107

Figure 4.3. Neina’s Fina l Draft ……… 107

Figure 4.4. Neina’s First Draft ………. 116

Figure 4.5. Neina’s Final Draft ……… 117

Figure 4.6. Mosez’s First Draft ……… 120

Figure 4.7. Mosez’s Final Draft ……… 121

Figure 4.8. Mosez’s First Draft ……… 122

Figure 4.9. Mosez’s First Draft ……… 135

Figure 4.10. Mosez’s Final Draft ……….. 135

Figure 4.11. Laila’s First Draft ………. 148

Figure 4.12. Laila’s Final Draft ……… 148

Figure 4.13. Laila’s First Draft ……… 151

Figure 4.14. Laila’s Final Draft ……… 151

Figure 4. 15. Neina’s First Draft ……… 155

x

Figure 4.17. Neina’s First Draft ……… . 156

Figure 4.18. Neina’s Final Draft ……… 157

Figure 4.19. Mosez’s First Draft ………. 159

Figure 4.20. Mosez’s First Draft ……….. 159

Figure 4.21. Mosez’s First Draft ……….. 160

Figure 4.22. Mosez’s Final Draft ………. 160

Figure 4.23. Laila’s First Draft ……… 162

Figure 4.24. Laila’s Final Draft ………... 163

Figure 4.25. Laila’s First Draft ……… 164

Figure 4.26. Laila’s Final Draft ……… ... 164

xi

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2.1. Category of Content of Teacher Feedback ……… 32

Table 2.2. Correcting Code ……… 37

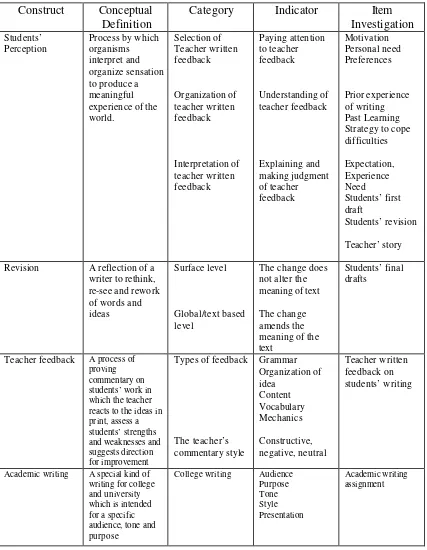

Table 2.3. Theoretical Blueprint … ………. ….. 54

Table 3.1. Research Par ticipants ………. 61

Table 3.2. List of Guiding Questions in Initial Interview ……… ……. 63

Table 3.3. Schedule of Data Collection ……….……. 68

Table 4.1. Initial Interview Coding ……… 83

xii

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ELT: English Language Teaching EFL: English as a Foreign Language ESL: English as a Second Language

CRCS: Center for Religious and Cross Cultural Studies Edu-Back: Educational Background

Past-L-Eng: Past Learning English Writ-Exp: Writing Experie nce

Purp-AW: Purpose of Academic Writing Char-AW: Characteristic of Academic Writing Writ-Diff:Writing Difficulty

Stra-W: Strategy in Writing Refl- L: Reflective Learning

Help-TFB: Helpfulness of Teacher Feedback

Rlt-AR-AW: Relation of Academic Reading and Academic Writing Int-TFB: Interpretation of Teacher Feedback

Conf: Conferences Writ-Style: Writing Style

Imp-TFB: Importance of Teacher Feedback Self- Ed: Self Edit

Str-Self-Ed: Strategy in Self Edit Self-Conf: Self Confidence

Gram-Imprv: Grammar Improvement Const-Rev: Constraint in Revision

Reasn-TFB: Reasons for Teacher Feedback St-Expc: Students’ Expectation

xiii Imp-AS-TFB: Importance Aspect of Teacher Feedback

Attennt-TFB: Attention to Teacher Feedback Agree-TFB: Agreement of Teacher Feedback Underst-TFB: Understanding of Teacher Feedback Ignor-TFB: Ignorance of Teacher Feedback

Reas-Ign-TFB: Reasons of Students’ Ignorance of Teacher Feedback Perso-Trait: Personal Trait

Sta-Un-TFB: Strategy in Understanding of Teacher Feedback Stra-Av-Plag: Strategy to Avoid Plagiarism

Attid-Plag: Attitude Toward Plagiarism Reas-Rev: Reason for Revision

Type-TFB: Types of Teacher Feedback

Cultr-Asp: Cultural Aspect of Teacher Feedback Resp-Tf-Style: Response to Teacher Feedback Style Agreem- TFB: Agreement of Teacher Feedback Cont-TFB: Contribution of Teacher Feedback Refl- TF-Style: Reflection of Teacher Feedback Style Clar-TFB: Clarification of Teacher Feedback

Peer-FB: Peer Feedback

Apprec-TB: Appreciation of Teacher Feedback Motv: Motivation

Self- Eff: Self Efficacy

Expe-TFB: Experience of Teacher Feedback Usef-TFB: Usefulness of Teacher Feedback Infl- TFB: Influence of Teacher Feedback Writ-Enj: Writing Enjoyment

Role-TFB-WE: Role of Teacher Feedback

Str-Rlt-AR-AW: Strategy in Relating Academic Reading to Academic Writing Pref-Tp-TFB: Preference to Types of Teacher Feedback

xiv Lang-Anxiety: Language Anxiety

Com-Barrier: Communication Barrier Teach-Self-Edit: Teaching Self Edit Opini-Plag: Opinion on Plagiarism Reas-N-Rev: Reason not to Revise

xv ABSTRACT

Niswatin Faoziah. 2008. Students’ Perception of Teacher Feedback on Their Academic Writing as Reflected in Revision. Yogyakarta: English language Studies, Graduate Program, Sanata Dharma University.

In the process writing approach, responding to students’ texts has been a central task for writing teachers. They often think that students will learn such comments and apply the new knowledge to subsequent drafts. Nevertheless, a great deal of researches have questioned the effectiveness of teacher feedback as a way of improving students’ writing. The grim picture of research in teacher feedback triggeres the writing teacher to question students’ perceptions and what their responses to teacher feedback are. Inspite of much research examining teacher feedback, and revision processes, limited studies scrutinized students’ perception and how they have incorporated their perceptions of teacher feedback into revision. This study scrutinizes students’ perception which takes into account individual differences such as educational background, need, expectation, previous writing experience and motivation. It is an attempt to understand the lived experience of the participants as part of the phenomenon, so phenomenological research seemed to be appropriate to be applied in the study.

This study explored students’ perception of teacher feedback on their academic writing as reflected in revision. It investigated two research questions namely; (1) what is students’ perception of teacher feedback?, and (2) how is the students’ perception reflected in their revision? These two research questions were answered through in-depth interviews, and analysis of students’ documents. The participants of this study were three students of the Center for Religious and Cross Cultural Studies at the Graduate School, Gadjah Mada University, Jogyakarta, and one of the English teacher.

The results indicated that students’ perceptions varied considerably according to educational background, experience, need, expectation, and students’ linguistic differences. These aspects seemed to stand in the way of students’ perceive of teacher feedback. In addition to this fact, their perceptions were also directly linked to the teacher’s feedback practices, which were aimed largerly at mechanical and grammatical accuracy, fluency, organization of ideas, style and content. In other words, the reseacher argued that students’ perceptions of teacher feedback were mainly a result of their needs, expectations, previous experiences and teacher feedback practice.

xvi

greatly to the students’ writing development as to what constitutes of good essay and their emotional state, particularly their motivation to write.

xvii

ABSTRAK

Niswatin Faoziah. 2008. Students’ Perception of Teacher Feedback on Their Academic Writing as Reflected in Revision. Yogyakarta: Kajian Bahasa Inggris, Program pasca Sarjana, Universitas Sanata Dharma.

Dalam pendekatan proses menulis, respon terhadap teks mahasiswa tela h menjadi tugas pokok bagi dosen menulis. Para dosen berpandangan mahasiswa akan belajar dari dari koreksi-koreksinya dan mendapatkan pengetahuan baru dari draft tersebut. Namun, banyak penelitian mempertanyakan efektifitas dari teacher feedback sebagai sebuah metode untuk meningkatkan kemampuan menulis mahasiswa. Sebagian penelitian mengenai teacher feedback sering menekankan efektifitas proses ini sebenarnya terletak pada pandangan mahasiswa dan bagaimana respon balik mereka terhadap teacher feedback itu sendiri.

Meskipun sudah banyak penelitian membahas teacher feedback dan proses revisi, penelitian yang memfokuskan dir i pada persepsi mahasiswa dan bagaimana mereka menggabungkan persepsi mereka tentang teacher feedback ke dalam proses revisi termasuk masih langka. Kajian ini berupaya menganalisis persepsi mahasiswa yang memperhatikan unsur -unsur pembeda individual seperti latar pendidikan, pengalaman menulis, dan bagaimana ekspektasi (kebutuhan, motivasi, harapan) mahasiswa terhadap teacher feedback. Peneliti tertarik memperhatikan esensi pengalaman subjek riset dan memahami fenomena, sehingga penelitian ini menggunakan pendekatan fenomenologi.

Penelitian ini bertujuan mengeksplorasi persepsi mahasiswa mengenai teacher feedback dalam academic writing mereka yang tercerminkan dalam revisi. Studi ini mengkaji dua pertanyaan penelitian. Pertama, apa persepsi-persepsi mahasiswa mengenai teacher feedback? Kedua, bagaimana persepsi-persepsi tersebut terefleksikan dalam revisi mereka. Kedua pertanyaan dalam kajian ini akan dijawab melalui in-depth interview dan didukung oleh analisa dokumen dari paper mahasiswa. Subjek riset ini difokuskan pada tiga orang mahasiswa di Program Studi Agama dan Lintas Budaya, Sekolah Pascasarjana, Universitas Gadjah Mada dan seorang dosen mereka.

xviii Kajian ini menemukan terdapatnya persepsi-persepsi yang berbeda antar mahasiswa mengenai penerimaan teacher feedback dalam hal isi tulisan dan grammar. Mahasiswa yang memandang isi tulisan dan pengorganisasian gagasan merupakan subjek revisi, maka dia cenderung mau menerima revisi dosen secara lebih mendasar dan total baik secara gramatikal maupun menyangkut hal-hal lain terkait isi tulisan. Sebaliknya mahasiswa ya ng menganggap subjek revisi lebih pada masalah gramatikal, dia cenderung hanya merevisi unsur-unsur gramatikal dari tulisan tersebut. Penelitian ini juga menemukan bahwa text-based changes mengenai isi dan pengorganisasian gagasan pada kenyataannya sulit diterima secara utuh, sehingga mahasiswa cenderung untuk selektif dalam melakukan revisi pada wilayah ini berdasar kemudahan tingkat revisinya. Menariknya, peneliti juga menemukan bahwa mahasiswa mengapresisasi teacher feedback dengan cara menerapkan beberapa strategi dalam merespon kesulitan-kesulitan dalam memahami kode dan simbol koreksi serta komentar yang kurang jelas. Akhirnya, kajian ini menunjukkan bahwa teacher feedback memiliki andil besar dalam pengembangan kemampuan writing mahasiswa seperti persepsi tentang karakteristik essay yang baik dan lebih memotivasi mereka dalam menulis.

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

This chapter sets out to present the background of the study by providing a

clear picture of the key issues in academic writing, teacher feedback practices, and

student perception of teacher feedback. The following part also organizes the

formulation of research problems through three extensive lenses including: research

question, problem limitation, and research goal and benefit.

A. Background of Study

In the academic world, writing ability holds a special status. It has been an

essential part of learning and thinking in the school context, particularly in the light of

21st century demands. Bandura (1993) states that academic writing may be assigned

for a variety of educational goals; assessing knowledge, promoting critical thinking,

stimulating creativity, encouraging discourse as part of the professional community,

and supporting cognition. Hence, academic writing needs to be learned and developed

during learners’ study particularly those who purse their degree in the graduate

programs. Learners at this level are expected to be able to organize ideas in

conformity and write critically in English with certain standards of prescribed English

rhetorical style and genre, as well as reflect accurate grammar.

However, Brown argues that the ability to write is a learned behavior

(2001:334) that signifies that the ability to write well is not a naturally acquired skill;

2 instructional settings or other environments. It should be practiced and learned

through experience. As claimed by Hadley (1993), writing also involves composing,

which implies the ability either to tell or retell pieces of information in the form of

narratives or description, or to trans form information into new texts, as in expository

or argumentative writing. Perhaps it is best viewed as a continuum of activities that

range from the more mechanical or formal aspects of "writing down" on the one end,

to the more complex act of composing on the other end. It is undoubtedly the act of

composing, however, which can create problems for students, especially for those

writing in a second language (L2) in academic contexts. As illustrated by Bereiter &

Scardamalia (1987:12), formulating new ideas can be difficult because it involves

transforming or reworking information, which is much more complex than writing as

telling. By putting together concepts and solving problems, the writer engages in "a

two-way interaction between continuously developing knowledge and continuously

developing text". Indeed, academic writing requires conscious effort and practice in

composing, developing, and analyzing ideas.

Compared to students writing in their native language (L1), however, students

writing in their L2 context have to deal with the difficulties laying down not only in

generating and organizing ideas, but also in translating these ideas into readable texts.

Furthermore, to become a proficient L2 writer, student needs to master some elements

such as content, style and organization as well as surface elements such as grammar,

vocabulary and the actual mechanic of writing.

Hyland & Hyland (2006:1) in their article argue that with the development of

3 classes emerged the significance of feedback provision which enabled students to

improve their language proficiency and to become more confident in their writing

abilities. Learner- centered approaches can also be used to train students to be good

writers and become autonomous learners. Therefore, providing feedback to students’

writing is one of the most challenging tasks a writing teacher has. Teachers typically

invest a great deal of time and effort in responding to the student’s text with the

assumption that their feedback will improve the student’s writing. Similarly, the act of

responding to student writing can enormously influence students’ attitudes to writing

and their motivation for future writing. Students tend to perceive that teacher

feedback gives them opportunity to improve their writing. But practically, students

can be easily confused by unclear, vague, and fuzzy comments. They get frustrated

with their writing progress. On the other hand, students can be positively supported to

explore many areas of knowledge and personal creativity through helpful and

constructive responses to their writing. It is clear that teacher feedback serves as an

important source of feedback for affecting students’ writing performance.

Even though feedback seems to be the central aspect in learning, the research

findings on teacher’s feedback still give us grim pictures. There are inconclusive

arguments related to the importance of composition teachers provide feedback to their

students. Some researchers like Hedgcock & Lefkowitz (1994) have demonstrated

that students expected and valued teacher feedback on their writing, while other

studies reported very little evidence that teacher feedback actually helped students’

writing improve (Leki,1990). As cited by Sommers (1982), and Hyland (2003:178),

4 comments and grammatical symbols in error correction. Students do not read written

teachers’ feedback, and those who read it rarely use the comments in their process of

revision. Teachers often write confusing and superficial comments that focus on

surface errors, may be incongruous, and that reflect paternalistic attitudes; teachers

are regarded as being too authoritarian, formalist and inconsistent.

In the context of L2 research, many studies of teacher feedback have also

come to similar conclusion that teachers focus largely on sentence- level concerns and

tend to appropriate students’ text, and are muddled in their responses (Goldstein, in

Silva and Matsuda, 2001:83). Furthermore, a research which is conducted by Zamel

(1985: 86) reported a similar finding as follows:

ESL writing teachers misread students texts, are inconsistent in their reactions, make arbitrary corrections, write contradictory comments, provide vague prescriptions, impose abstract rules and standards, respond to texts as fixed and final products, and rarely make content-specific comments or offer specific strategies for revising the texts……. The teachers overwhelmingly view themselves as language teachers rather than writing teachers.

Given such evidences, however, there is no a clear set of universal guidelines

that will assure such encouraging and positive experience for all students.

Consequently, I do believe that there is still a need to provide important insights

particularly for teachers who are in search of providing feedback on students’ writing.

I expect that the present study will enrich some of the previous research studies on

teacher fe edback to students’ writing, especially by emphasizing on the individual

variables in the ways students perceive teacher feedback and how it is reflected in

revision. Besides that, this investigation may contribute to a deeper understanding of

5 students’ revision processes and in helping students achieve a greater understanding

of teacher feedback on their academic writing.

B. Problem Identification

It is a common concern for English teachers to know the best way to respond

to students’ writing. While responding to students’ text, at the same time they also

seek to find out how students’ understand and respond to teacher’s feedback. A

number of questions are often raised in students’ responses to teacher feedback such

as; what do students really think about the teacher’s feedback?, do students

understand the teacher feedback?, how do students make use of the teacher feedback?,

how much of the feedback do students process and how do they go about doing this?,

and what are the types of feedback that might be difficult to interpret? What are the

characteristics of teacher feedback that appear to influence students’ revision? And is

the revision influenced by teacher feedback lead to substantive and effective change

in students’ writing? This study is an attempt to scrutinize the understanding of

students’ perceptions of teacher feedback, and consider variables including the

teacher (types of teacher feedback), and the students (students’ age, background,

personality and writing experience) as well as the application of teacher feedback in

the students’ revised papers.

This study does not intent to test the theory or identify variables to study.

However, the study identifies the “essence” of participants’ experiences concerning

the phenomena of students’ perception of teacher feedback on their academic writing

6 experience” of the participant by asking each participant to tell his or her stories. The

researcher is mainly interested in understanding what and how phenomena happen,

focusing on what the product of the students’ perception of teacher feedback is as well

as the process of how these perceptions of teacher feedback are used in their revised

papers. Finally, the study is expected to be able to provide a more effective feedback

model and motivate students to become better writers.

C. Problem Limitation

Teacher feedback is crucial to the process of writing. It is an instrumental tool

to assess students’ strengths and weaknesses as well as a chamber of the teacher’s

interaction with the students. It is a good medium to facilitate thinking, learning, and

reflective processes. However, some investigations have shown that the ideal

teacher-student shared understanding and the improvement of teacher-students’ writing skill are

poorly implemented in practice. Not surprisingly then, students ignore and fail to

understand teacher feedback. There should be understanding of why students ignore

and reject to teacher feedback.

In investigating students’ perceptions of teacher feedback, one must be aware

of the complex aspects involved in that process such as teacher feedback, student

reactions to commentary, and student revisions interact with one another in a

formidable way. The dynamic interaction among the aspects above creates a

complexity of discussion such as how teachers intervene in writing instruction, and

7 teachers stress early mastery of the mechanical aspects of writing, or should they urge

their students to pay little attention to correctness, at least until after a first draft has

been written? Why do not students pay attention to teacher feedback, what aspect are

students concerned with teacher feedback, in what ways can students deal with

feedback they receive? What kinds of teacher feedback do students expect and desire,

what factors seem to influence students' expectations and preferences for teacher

feedback?, and Does feedback make any difference to the quality of students’

writing?

In this study, I am concerned with the issues closely related to students’

perceptions of teacher feedback, teacher feedback, and students’ revision. Students’

perceptions theoretically consist of three subsequent categories “selection/attention,

understanding, and interpretation of teacher feedback”. Students were asked about

their perceptions of teacher feedback in subsequent actions: e.g. What aspect do they

pay attention to? Did they have trouble understanding any teacher feedback? What

they do to resolve the difficulties of teacher feedback? How do students perceive, and

react to comments and how do they employ teacher feedback?

It is apparent that this is an investigation of students’ perception of teacher

feedback on their academic writing and its application as reflected in their revision. I

may articulate perception as aspects of understanding as to why people behave in the

way they do. Since this is a qualitative approach, I do not try to control students’

behavior instead try to understand the behavior of the individual as seeking

8 students they are mo tivated by the opportunity to become all they are capable of

becoming. In addition, as adult students, they are self aware and engage in purposeful

behavior. They are thought to learn, to alter and construct their environment in the

process of learning.

In the investigation of students’ perceptions of teacher feedback on their

academic writing as reflected in their revised papers, the researcher applies interviews

and document analysis as the basis for gathering data with a carefully selected sample

of participants, all of whom have direct experiences with the phenomena being

studied. To meet the criteria of being participants, the students must experience

teacher feedback, they also must revise their papers and keep them. That is why the

participants of this study are limited to only three students enrolled in the English

class of the Center for Religious and Cross Cultural Studies, at the Graduate School,

Gadjah Mada University, Jogyakarta 2006-2007 and one the English teacher.

D. Research Problems

The fact that students’ perceptions of teacher feedback vary, means that the

study in this area is welcomed and appreciated. Personally, I am eager to find out

what the perception is and how the perception used in revision influences the quality

of students’ text. The following research questions guided the current research:

1. What is students’ perception of teacher feedback on their academic writing?

9

E. Research Goals and Objectives

The intention in this study is to attain the following goals:

1. To describe the students’ understanding of teacher feedback on their academic

writing through their “lived experience”.

2. To identify the application of students’ perceptions of teacher feedback in their

revision processes.

3. To describe researcher understanding of students’ perception of teacher

feedback on their academic writing and its application in the revision processes.

The investigation of students’ perceptions of teacher feedback on the ir

academic writing leads me to the practical objective as follows:

1. To understand students’ perceptions of teacher feedback

2. To identify how students’ perceptions of teacher feedback on their academic

writing shaped their revision.

3. To reveal the reasons for students’ perceptions of teacher feedback on their

academic writing

4. To find a mutual understanding of students and teacher by allowing students to

give their own perspectives on teacher feedback as they currently deal with

5. To describe the application of students’ perceptions of teacher feedback in

revision as an attempt to see the improvement of text including how they

monitor and assess critically to teacher feedback.

6. To encourage students to have a positive motivational belief and self esteem in

10

F. Research Benefits

The result of this study exposes the theoretical foundation for language

pedagogy and contributes to the development of English educational theory and

practices particularly in teaching academic writing. In details, the research will be

beneficial in two main fields, namely:

1. Scientific benefits

a. This study exemplifies the model of phenomenological research which

underlies the understanding of students’ perceptions of teacher feedback as

revealed through their story, and document analysis in order to empower

students as self regulated learners

b. Through the interpreted story of the research participants and the document

analysis, the study directs us to an understanding of the students’

interpretation of teacher feedback which emphasizes on creating environment

in teaching writing simultaneously, namely:

1) To foster and enhance the growth and development of the participant

students in terms of their attitude, needs, aspirations and self- fulfillment.

2) To disseminate the fact that not only do individuals’ perceptions differ

from one another but that their diversity can be a source of great strength

to the improvement of writing skill and may contribute to the development

of English language teaching and particularly to the teaching of English as

a foreign language.

11 a. This study provides meaningful insight and information to EFL teachers,

trainers, and language experts, as well as language researchers in light of

understanding students’ interpretation and responses to teacher feedback as an

endeavor to help students acquire writing skills.

b. The study provides an opportunity between teacher and student to reflect and

construct their own learning derived from their experiences and knowledge.

c. The study may present an innovation in responding to students’ writing

particularly for advanced learners to have an active role in the language

classroom.

d. The study provides a chance for teacher and students to interact and modify his

or her teaching practices particularly in terms of feedback. Thus, the study

12

CHAPTER II

LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter attempts to review some relevant theories from various literature

addressing the issues in the study. It explores a review of notions namely: (i) the

nature of academic writing (ii) the nature of teacher feedback (iii) and the construct of

students’ perception of teacher feedback. In addition, to limit the scope of this inquiry

and to strengthen the significance of the study, as well as frame the problem of the

study, some related theories, previous studies, and research reports are presented here.

A. Theoretical Review

1. The Nature of Academic Writing

Academic writing should be understood as an umbrella term under which a

wide and a diverse range of approaches to the practices of writing are categorized.

Jordan’s (1997) idea claimed that such variety or diversity is derived from an

underlying philosophy, starting point of the students, the purpose and type of writing

or simply personal preference that makes the act of writing never easy do define.

Recently, there is a definition of academic writing presented by Oshima and

Hogue (1991:2) as a special kind of writing for college and university which is

intended for a specific audience, tone and purpose. Meanwhile Rosemary Jones

(http://amarris.homestead.com/files/AcademicWriting.htm) states that academic

writing is a product of analysis which derives its process by breaking down any ideas,

13 increasing one’s understanding. Therefore, it can be inferred that academic writing is

a particular type of writing which transforms one’s ideas into written medium which

has a certain purpose, intended audience and style as well as characteristic of its

structure.

a. Characteristics of Academic writing

In the academic world, students are required to undertake a variety of writing

tasks depending on their chosen degrees. Characteristically, these tasks will vary from

one to another; however, each assignment type of writing has a clear structure to

follow. In other words, the style of English in students’ writing relies on some factors

such as the purpose of the assignment, the preferred structured of the assignment type,

and the audience for whom it is intended. Broadly defined, as stated by Swales and

Feak (1997:7-29) the characteristics of academic writing can be viewed as a product

of many considerations including audience, purpose, organization, style, flow and

presentation. Consequently, to be successful in a writing task, a student should have

an understanding of audience’s expectation, the purpose of writing, prior knowledge,

the regular pattern of organization, and must communicate consistently and

appropriately both for the message being conveyed as well as for the audience.

Briefly, academic writing seems to be a unique type of writing which has

special features. However, Davis & McKay (1996:2) strengthen that even though it is

unique, academic writing shares certain features with other writing through using it in

14 call for research and documentation. All these techniques and skills involved in

academic writing are adaptable and useable outside the academic writing classroom.

Before looking at the characteristic of academic writing in detail, we need to

know the common classification of academic writing genre in which learners need to

acquire. Brown (2004:219) in his book mentions that academic writing genre consists

of paper and general subject reports, essays, compositions, academically focused

journals, short-answer test responses, technical reports (e.g., lab reports), theses, and

dissertations. In classroom practices, much of academic writing will be in the form of

essay.

Langan (1996:5-7) asserts that an essay typically has an introductory paragraph,

supporting paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph. In addition, there is a central idea

or point developed in an essay called thesis statement. The thesis appears in the

introductory paragraph and should be developed in an essay. Then supporting

paragraphs which begin with a topic sentence states the point to be detail in that

paragraph. Just as a thesis statement presents a focus for the entire essay, the topic

sentences provide a focus for each supporting paragraph. At the end of the essay is the

concluding paragraph. It frequently reviews the essay by restating briefly the thesis

and, at times, the main supporting pints of the essay.

Further, Davis & McKay (1996:4-21) stage three modes of writing used in

social contents including description, narration, exposition and argument. All these

modes of writing must be presented clearly and accurately. In terms of this

perspective, it is also important to establish the feeling of objectivity by eliminating

15

b. The Approaches To Academic Writing

Lately, there has been a shift of orientation in second language teaching and

learning leading to more demanding roles for teacher and students. Sheild (1996)

argues that teachers are no longer regarded as “ a dispenser of knowledge” or “the

distributor of sanction and judgments”. In this perspective, the teacher seems to be

less authoritative and less dominant in teaching practices while students have greater

participation and responsibility in learning language. Thus, students are no longer

passive recipients of knowledge instead active participants in language teaching and

learning.

At the same time, there also has been a major change in the theory and

research of composition since 1963. The change is a shift from the product to the

process of writing. The product oriented approach views that writing process as linear

one which can be determined by the writer before starting to write (Hairston, 1982). It

focuses on the composition made up of a series of parts-words, sentences, and

paragraphs-but not on the whole discourse with meaning and ideas (Sommers,

1982:148-156).

Accordingly, teaching writing in this approach is a matter of prescribing a set

of predetermined tasks or exercises for the students. The students’ concern is merely

exercises on how to put words into grammatical sentences. In other words, this is not

composing but a ‘grammar exercise’ in a controlled context. As cited by Jones (1985)

this approach echoes the school tradition which has more emphasis on the conscious

16 knowledge of these rules. The students adopting this approach find themselves

duplicating model texts and trying various exercises intended to adhering to relevant

features of a text. The product approach demands that students’ focus, sequentially,

on model, form, and duplication. That is why students are restricted in what they can

write.

Corresponding to the product approach characteristics above, Escholz (1980:

24) points out that the approach encourages students to use the same plan in a

multitude of settings, applying the same form regardless of content, thereby,

inhibiting writers rather than empowering them or liberating them.

The role of the teacher is only as the spotter of grammatical errors and the

reinforcer of a set of grammar rules. In relation to feedback, teachers simply

concentrate with error correction, and no attempt to help students in generating and

exploring ideas in writing. In other word, it aims to produce an error- free sentence.

This kind of response also is not concerned with reader-based discourse (e.g. Zamel,

1983:2). With such a view, language proficiency is primary element which determines

the skill of writing and rules out the significance of discovering ideas and constructing

meaning.

Fortunately, the shift from product to process has caused writing teacher to

review their role in teaching. Second language writers are active agents rather than

passive “tabula rasa” supplied with a set of grammatical rules. Teacher and students

collaboratively are involved in discovering what language is and how a piece of

17 As cited by Taylor (1981:13) in the process approach we no longer believe

that writing is a uni-directional process of recording “presorted, predigested ideas”.

Instead, writing does not follow an orderly sequence of planning, organizing and

writing procedures. It is recursive, a “cyclical process” during which writers move

back and forth on a continuum, discovering, analyzing, and synthesizing ideas. (Hugh,

at al., 1983). The stages of writing processes refer to those of Seow (2002:315) who

divides writing process into four stages: planning, drafting, revis ing, and editing (see

Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Stages in the Writing Process (Seow, 2002:315)

In comparison with the above categorization of writing process, Flower and

Hayes’ model is the frequently adapted model by many scholars (Zimmerman and

Rodriguez, 1992:6). This is an early and influential model of the writing process.

Beginning in the late of 1970s, Hayes-Flower developed a cognitive model of the

writing process which tried to provide a synthesis of research, and this has been

prevailing model for the past 15 years in composition. As cited by Grape & Kaplan

(1996:91), Hayes and Flower have claimed that the composing processes are Process Activated

Process Terminated

Planning

Editing Revising

18 interactive, intermingling, and potentially simultaneous. In addition, composing is a

goal-directed activity, and expert writers write differently from novice writers. From

these hypotheses, they subsequently developed a model of the composing process.

According to Weigle (2002:23-24) the Hayes and Flower model attempts to

sketch the various influences on the writing process, particularly those internal to the

writers. The Hayes-Flower model of writing sees the writing process as consisting of

the three main elements. First, there is the task environment which consists of the

writing assignment, and the text produced so far. The second element consists of the

cognitive processes involved in writing. Within the cognitive processes, three

operational processes generate the written text namely planning (deciding what to do

and how to say it), translating (turning plans into written text), and revising

(improving existing text). These processes are managed by an executive control called

a monitor. Finally, in the planning process, there exists three components namely

generating ideas, organizing information, and setting goals. In the actual generation of

the text, the ideas in planning are translated into language on page, which is then

reviewed and revised. The third element is the writer’s long-term memory, including

knowledge of topic, knowledge of aud ience, and genre. (see Figure 2.2). Accordingly,

in this model, it can be found that writing is recursive and not linear in which writers

are constantly planning and revising when they compose. They are continually

rewriting their papers in order to find their arguments and to participate readers’

19

Figure 2.2 The Hayes and Flower (1980) Writing Process Model

In terms of the perspective above, Pennington (1991) confirms that the

process approach enables writers to modify their written texts as they review their

writing. There exists a creative and purposeful activity of reflecting, both in the sense

of mirroring and in the sense of deliberating on students’ thoughts.

Smith (1982:104) states that the advantage in adopting the process approach is

in developing the significance of the cyclical and recursive nature of writing, in which

ordinary pre-writing, writing and re-writing are frequently seen to be going on

simultaneously. The process approach empowers its students, hence enabling them to

20 tasks, drafting, feedback and informed choices hereby encouraging students to be

responsible for making improvements themselves (Jordan, 1997:168).

The emergence of the process-oriented approach in language pedagogy brings

about a change of teacher role in teaching writing. They no longer play the role

predominantly as the authority on writing, but rather as consultant and assistants to

help students in carrying out their responsibility as writers. Furthermore, teachers are

involved in the various processes in the act of composing in order to help students

produce coherent, meaningful, and creative discourse.

Just as there is a change from product to process oriented approach, so there is

also a call for a different feedback system. Unlike the product approach, which deems

that writing as a product to be evaluated, the process approach thinks about writing as

a complex developmental task involving the discovery and constructing of meaning.

Thus, in responding to students’ writing, teachers stress on both content and form.

They help students from the very beginning process of writing until the final stage of

polishing the whole written discourse. Likewise, teachers’ role in providing feedback

is more demanding. They become facilitators in helping students, providing guidance

in the process of composition as well as critical judge in emphasizing grammatical

correctness. As Jordan (1997) suggests that if we favor the process approach we need

to give more specific guidance and help students to understand how to revise their

writing, and lead them to the “circles of revision”. Consequently, it is important for

teachers not to correct or to give answers immediately. Instead, presenting students

with a degree of autonomy that empowers them in becoming active participants in the

21 Understanding the significance of providing feedback does not take for

granted that teachers are able to provide appropriate feedback. Since the pattern of

feedback and their responses to students writing varies depending on their conception

of the writing process and understanding of students’ errors. Therefore, teachers have

to find effective ways of providing feedback.

In considering the two approaches above, it is obvious that there should be a

need to incorporate the product approach into the system of the process approach in

writing. In this sense, there should be a need to emphasize accuracy and language in

the feedback stage of writing. Thus, in the study, I investigate students’ perception of

teacher feedback on their academic writing as reflected in their revised papers which

is then perceived as both product and process approaches. The product approach will

be used to see the product of the students’ perception while, the process approach is

used to examine how their perceptions are applied in revision.

In contrast to the approaches above, as cited in Nunan (1999:171-89), Raimes

(1993) classifies four approaches to second language writing instruction namely

product approach, process approach, genre approach and discourse based approach.

Historically, until the mid 1970s, pedagogy was dominated by form- focused sentences

which is in line with the development of oral language. It focused on final product,

coherent and error- free text. In this approach, learners have to imitate, copy, and

transform a model which is provided by the teacher or the textbook, we may call it as

“reproductive language work”. In contrast, in the mid 1970s, second language

teachers discovered the process approach. As the term offered, this approach

22 to get their ideas on papers without worrying about formal correctness in the initial

stages. In the mid 1980s, two trends emerged simultaneously, the first was the genre

approach which focused on academic content, raising awareness of reader’s demand

by the nature of the academic subject they were required to master. The last approach

is the discourse- based approach which concentrated on the creation of coherent and

cohesive discourse.

Similarly, Jordan (1997) offers two approaches of academic writing—product

approach and process approach. The former approach focuses on the end product of

the writing process, with its major emphasis on surface- level mechanics. The latter

concentrates on how a product is produced with its major concern on content and

discourse as a whole. The product approach is often criticized because it does not take

into account the psychological and cognitive processes intrinsic to writing (Wason,

1981:351-363), while the process approach is considered as overemphasizing on the

significance of students’ psychological functioning and neglects the reality of

academia and fails to realistically prepare students for the real world as it creates a

classroom situation that bears little resemblance to the situations in which a student’s

writing will eventually be exercised (Horowitz, 1986a:144).

In response to this debate, we should not neglect the fact that the two

approaches correspond to two perspectives for looking at the writing. There is no one

best way to understand and to teach such a complex skill as writing. We can only say

that the process approach gives people a new way of looking at writing creatively,

whereas the product-approach gives the idea that grammar and syntax are also

23 there is a need to integrate the two approaches into one unified theory in which

student writers and teacher -readers can explore meaningful discourse together.

2. Teacher Feedback on Students’ Writing

Providing feedback seems to be a very important task for the composition

teachers. Basically, teachers assume that feedback can help students in the learning

process and provides the kind of individualized attention which seldom happens under

normal classroom conditions. As writers, they want to know how readers respond to

their work. Through teacher feedback, the response offers an opportunity for students

to figure out how the readers respond to their writing so they can learn from the

teacher’s response.

Hyland (2003:177) in his book convincingly states that feedback in learning

process can be seen as crucial for both encouraging the development of students’

writing and consolidating their learning. This idea is derived from the idea that

knowledge is a social construct rather than a cognitive entity and that learning is a

social process. (Bruffe, 1993; McComiskey, 2000). Accordingly, learning cannot be

conceptualized as an entity that we transfer from the mind of one person to another.

Learning should be viewed as an active, social, and constructive process in a context

that is fostered trough transactions with others (www.carmenmonta de Cabrera,

2003).

Aljaafreh & Lantolf (1994) claim that the social cultural perspective draws

heavily on the work of Vygotsky that views humans use physical and symbolic

24 in order to change relationships. As linguistic processes, speaking and writing are

perceived as inherently social, and their development proceeds from the social to the

individual as a consequence of the linguistically mediated interaction which arises

between learners and others, often more experienced members of their socio-cultural

world

Vygotsky (1978) proposed the concept of the zo ne of proximal development

(ZPD), as a frame for understanding central tenets of his cognitive theory: the

transformation of an interpersonal (social) process to an intrapersonal one, the stages

of internalization, and the role of experienced learners. The zone of proximal

development, he wrote is

The distance between the [children’s] actual development level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (p. 86).

As discussed by Vygotsky (1978) that there is a stage in cognitive

development named “zone of proximal development (ZPD)” where skills are

extended trough the guidance and expertise of others, the implications of ZPD for

adult students are that learners first depend on the assistance of more skilled

individuals to regulate learning and perform new and difficult tasks. On the other

hand, the construct of ZPD specifies that development is unlikely to occur if too much

guidance is provided or if the task is too easy. Freedman, Greenleaf & Sperling (1987)

argue that when Vygotsky's theoretical insights are applied to the case of response to

student writing, it seems apparent that to be effective, teacher and student writers

25 establish collaborative problem solving not merely as a way of teaching but as jointly

endorsing teaching and learning whereby teacher and learner negotia te the roles they

play.

In short, students’ perception and teacher feedback entails social interaction

appealing to the notion of the “zone of proximal development” in which intellectual skills are progressively mastered by the learners. When they learn, they make errors

and rely heavily on teacher’s corrective advice. After a large amount of practice,

students ultimately reach a point at which they can perform the skill well on their

own. Thus, there is a point at which student can perform well when they are helped

through problem solving under adult guidance or collaboration with peers.

a. The Nature of Written Teacher Feedback

Keh (1990:194) asserts that feedback is usually viewed as a linear process of

providing input to a writer for the purpose of providing information for revision.

However, as the development of the learner centered approaches to writing instruction

has amended the way feedback is perceived.

Nowadays the issue of feedback is no longer that of being merely input from

one person to another. According to Freedman (1985:321) feedback is acknowledged

as:

26 In other words, feedback is a medium of interaction within the context of

interpersonal classroom relationship. Teacher feedback on students writing is an

important channel of teacher- student interaction which refers to the process of

providing commentary on students’ work in which the teacher reacts to the ideas in

print, assesses a students’ strengths and weaknesses and suggests direction for

improvement. This feedback is delivered written on the blank space of the student

essay or spoken to the student in short conferences. Traditionally students receive

feedback on the formal occasion of the return of their graded essays. Hitherto,

recently feedback both written and oral are integrated in the writing process and

received along with the students’ working on their composition (Freedman, 1987;

Langer & Applebee, 1987).

Regardless of when the feedback is given to the students, teachers assume that

the significance of feedback should not be underestimated. It is a way of empowering

students in becoming active participants in written composition rather than passive

recipients of feedback. The importance of providing feedback to students’ writing

does not inevitably allow the teacher to provide appropriate feedback. The research

conducted by Mac Donald (1991:35) examining the area of students’ processing

teacher feedback has found that the ideal of teacher-students shared understanding is

defectively realized in practice. Teacher feedback often lacks thought; students often

misunderstand their teacher feedback, the students’ writing often receives negative

teachers regress, and many students do not attend to teacher feedback to begin with.

Meanwhile research examining the qualities of teachers’ written feedback on

27 Perhaps because they tent to read looking for errors (Heffernan, 1983), teachers tend

to mark surface errors (Cumming, 1985). Therefore, without doubt, students

frequently misunderstand and fail to benefit from teachers feedback. The positive side

of teacher feedback reported by Olsen and Raffeld (1987) is that it concerns essay

content associated with better essays than feedback concerning with essay language,

grammar, and usage.

Given the fact that teacher feedback to students’ writing is unclear,

ineffective, and misunderstood, we need to observe the reasons underlying why

students may get things wrong in terms of response to teacher feedback. As referred

to Johnson’s idea (1990:279-285) introducing two different situations caused students

the wrong response. The first is that they simply do not have the appropriate

knowledge, and so the knowledge or skill the students have is incomplete. This is

what we call error. The second situation is that learners lack the processing ability.

The later is called as mistake. The problem in this context does not lie whether the

learner’s knowledge right or wrong, instead the learner has difficulty in performing

the knowledge he or she has acquired in operating conditions. As a result, he or she

does not correct his or her wrong doing even after careful re-examination.

These two distinctive situations above lead us to the feedback practice in

writing pedagogy. Bialystok (1982:181-206) argues that the first situation relates to

the learner knowledge of the formal properties of the target linguistic codes, while the

second stresses the ability to make use of the formal properties to express meaning

and content. Students need two kinds of knowledge in processing feedback to refine

28 the knowledge in order to develop their procedural knowledge for creating and

expressing their ideas.

As proposed by Johnson (1990:279-285), there are some factors to consider

which enable teacher feedback to function more effectively namely:

a. A desire or need of the learner to correct the wrong behavior

b. An internal representation of what the correct behavior looks like (i.e. the

learner’s own understanding about the correct behavior)

c. The realization of the occurrence of the wrong behavior

d. An opportunity to re-practice the skill as reinforcement.

All in all, it is suggested that teachers in providing feedback need to think

deliberately about the better ways of motivating students to attend to the error rather

than relying heavily on how the teacher spots the errors. The initial guidance from

teacher should aim at helping learners from internal representation of what the wrong

behavior is. Students should be promoted to have self-awareness toward wrong

behavior carried out so that later they will be able to eliminate errors.

b. The Form of Teacher Feedback

A wide range of techniques have been proposed to provide teacher feedback

forms. According to Bardine et al., (2000:94-101) teacher feedback could be

categorized into three categories 1). a word or words 2). a symbol including

29 symbols. All these categories are able to used to comment on students’ writing

focusing on either structure concern or local or surface level concerns.

Whereas, according to Hyland (2003:180-183) there are five common forms

of teacher written feedback. They are commentary feedback, cover sheets, minimal

marking feedbacks, taped comments, and electronic feedback. Probably, the most

common form of written teacher feedback is in forms of comments. It contains the

teacher’s handwritten commentary on the students’ text. It is the best way of

responding to the students’ writing by showing their responses on how the text

appears to them as readers, how it could be improved, and how successfully the text is

written. Cover sheets or rubrics are a kind of variation on commentary which often

escorts on final draft. It is used to assess students’ assignments and performance based

on the criteria. That is why, it is useful in making grading decisions and showing what

the teacher values in a particular piece of writing. Minimal marking refers to a type of

in-text, form –based feedback. This kind of feedback form usually uses “correction

codes” to indicate the location of types of errors, and eliminates students’ threat and

make correction neater. The next type is taped commentary which is conceived of as

an alternative marginal comment or teacher’ remark recorded in a tape recorder. It is

beneficial for both parties; the teachers and the students. Since this technique saves

teacher’ time, energy, and adds novelty. In addition, it also provides students with an

opportunity of listening practice, and helps learners with auditory learning

preferences. Besides that, it tells the students how the audience responds to their text

as it develops. The last type of teacher feedback is electronic feedback provided by

30 displayed in a separate window while reading a word-processed text. All of these

techniques in teacher feedback forms in turn enable the teacher to provide feedback in

flexible ways.

c. The Function of Teacher Feedback

In order to organize teacher feedback, I refer to categories adapted from

Bardine et al. (2000:94-10l) classifying teacher feedback into five function categories.

The first of these is the question. This comment asks the students about their writing.

The second is instructional comment. This informs students about ways to improve

their writing. The third is praise. This constitutes positive comment that recognizes

students’ good work. The fourth is attention focusing on comments. This comment

usually highlights attention to an aspect of students’ writing, normally related with the

use of symbols without further explanation. The fifth is correction. This last comment

provides students writing with the correct answer for example supplying students the

correct spelling of the word or structure of sentence.

d. The Types of Teacher Feedback

Leki (1990) points out that there are two types of teacher feedback when

teacher responds to students’ writing. They are ‘surface errors’ and “global concerns.”

Surface errors are those connected to grammar, syntax, spelling, and so on; while

global concerns comprise such things as overall organization, sign posting, cohesion,

and clarity of meaning.

31 lies on the fact that the teacher can address more personalized comment and assess

individual student strengths and weaknesses as well as communicate directly to the

students. Despite the significance of feedback, research has shown that for many

teachers responding to students’ writing has become a mechanical activity. As

Sommers (1982), and a few others who conducted their research in a second language

environment like Keh (1990), Hyland (1990), Kepner (1991), Ferris (1995), reported

that many teachers treat the teacher response stage as a copy editing stage, focusing

mostly on the correction of grammar errors in student compositions.

This fact calls for the teacher’s attention to be given more to content rather

than form. The question is then raised about how teachers should respond without

adding anxiety to the students. The researcher like Hyland (1990) suggests the

effective ways to respond to students’ writing stating that the teachers should provide

a platform from which students themselves can reassess and redraft their work.

Furthermore, Hyland (1990) and Mahili (1994) necessitate detailed and informative

comments on content. These are comments that allow the teachers to reach out to the

students. This means that short, questioning remarks, placed in-between sentences

would be obviously inadequate. Instead, teachers should attempt to build a dialogue

with the students. To do that, the nature of the comments should reflect teacher’s

comments as interested readers, and not as judges or evaluators. The comments of this

nature, besides giving a clear picture of what the student needs to do, also respond to

the students themselves and not just to their writing. Simply put, teachers should

32 More specifically, there are two types of content on teacher commentary (see

Table 2.1) The first is facilitative comments. Comments which try not to take control

of the students' work, or attempt to deliver judgments on it. Another type of comment

that can be considered as facilitative, is praise (sometimes referred to as positive

comments). The second is directive comments, which can be defined as comments in

the form of evaluative comments, instructional comments and questions. Though not

necessarily negative in nature, these could result in the students losing ownership of

their work, as they try to accommodate their teachers’ comments when revising

(Straub, 1996).

Table 2.1. Category of content of teacher feedback adopted from Ravichandran (2002:5)

Category Definition Example

Directive

Evaluative comments Comments of a judgmental nature,

describing students writing competence

Weak Intro

Topic sentence is too general

Instructional comments Comments that serve to teach, or instruct students to make changes

Be direct and clear

Do not give advice in your conclusion

Link this point to the topic sentence

Questioning comments (comments seeking clarification)

Comments that seek further information from students

Incomplete

What do you mean? Can you elaborate on this?

Facilitative

Teachers own opinions and ideas

Comments that express the teachers opinions or suggestions

33

Positive comments (Praise)

Comments that point out the strong parts of the essay. Encouragement.

Good point

The main idea is well supported here

In spite of the controversy, I think the composition teacher needs to balance

the need of students in term of accuracy of fluency in writing. Combining both

content and form feedback would be much appreciated. Since students need to know

if what they are doing is right on the track or not. At the same time, they anticipate

their writing to be linguistically accurate by pointing out their strengths as well as the

weaknesses.

e. The Role of Teacher in Providing Feedback

When providing feedback, teachers are basically supposed to respond to all

aspect of the students’ texts including content, organization, grammar, vocabulary,

and mechanic. However not all aspects of the text should be covered on every draft.

Teachers need to understand what students want from feedback and what they attend

to in their revision. Research suggests that teacher written feedback in highly valued

by L2 writers (Hyland, 1998) and that many students particularly favor feedback on

their grammar (Leki, 1990). Error- free work is often a major concern for L2 writers,

possibly because of prior learning experience and the fact that many will go on to be

evaluated in the academic and work place where accuracy may be essential. Yet,

Radecki and Swale, (1988) argue that in the context where students were asked to