1 23

Journal of Child and Family Studies

ISSN 1062-1024

J Child Fam Stud

DOI 10.1007/s10826-012-9703-0

Parental Perceptions of Services Provided

for Children with Autism in Jordan

Mohammad A. AL Jabery, Diana

H. Arabiat, Hatem A. AL Khamra, Iman

Amy Betawi & Sinaria Kamil Abdel

1 23

O R I G I N A L P A P E R

Parental Perceptions of Services Provided for Children

with Autism in Jordan

Mohammad A. AL Jabery•Diana H. Arabiat •

Hatem A. AL Khamra•Iman Amy Betawi•

Sinaria Kamil Abdel Jabbar

Springer Science+Business Media New York 2012

Abstract Providing formal support for children with autism and their parents is important and mandatory to improve children’s abilities and enhance the capabilities of parents. The present study attempted to investigate the perceptions of parents of children with autism regarding the services provided in Jordan. A questionnaire consisting of five sections was designed and distributed to a sample of 60 parents of children with autism (5–18 years old) among four special education institutions in Jordan. The ques-tionnaire addressed five domains: demographics, type and number of received services, methods and difficulties of obtaining services, parents’ satisfaction, and parents’ per-ceived needed services. The results revealed that the ser-vice delivery system with which parents interacted was composed of multiple places and providers, but had several difficulties. Parents participating in this study expressed an average satisfaction with the received services. Issues pertaining to the cost of services, parents-professional partnerships, and overall quality of services were seen by parents as sources of low satisfaction. On the other hand, parents expressed the need for early intervention, family

counseling, and community awareness services. Further suggestions and implications are presented in the study.

Keywords AutismParents’ satisfactionSpecial

education Parent’s perceptionsServices in Jordan

Introduction

Autism is categorized under the Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDD) category as described by the American Psychiatric Association. Autism is marked by deficits in reciprocal social interaction, communication (verbal and nonverbal), and a restricted repertoire of activity and interest (DSM IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association 2000). The nature of autism demands a wide range of services (e.g., health and medical, rehabilitative, and edu-cational). These services might require parents to interact with multiple providers, try different types of services or treatments, and dedicate their time, money, and energy (Goin-Kochel et al.2009).

Working with children with autism represents a chal-lenge for those who are engaged with them (e.g., teachers, paraprofessionals, primary health providers, and parents). The challenge emerges from ‘‘the heterogeneity of stu-dents’ characteristics and needs, the idiosyncratic and occasionally severe nature of the students’ behavioral challenges, the dramatic increase in the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders, the strongly held and diverse opinions regarding appropriate intervention, and the liti-gious atmosphere engendered by these opinions’’ (Dunlap et al. 2008, p. 111). Making the challenge even more complex is the uncertainties and lack of consensus regarding which treatments will help children with autism (Mackintosh et al. 2012).

M. A. AL Jabery (&)H. A. AL Khamra

Department of Counseling and Special Education, Faculty of Educational Sciences, The University of Jordan, Amman 11942, Jordan

e-mail: [email protected]

D. H. Arabiat

Department of Maternal and Child Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, The University of Jordan, Amman 11942, Jordan

I. A. BetawiS. K. Abdel Jabbar

Department of Curriculum and Instruction,

Faculty of Educational Sciences, The University of Jordan, Amman 11942, Jordan

J Child Fam Stud

In this regard, parents of children with autism are left with the most demanding challenges that require them, on the one hand, to make decisions regarding the type of therapies that are appropriate to their children and, on the other hand, the criteria to implement and determine the effectiveness of these therapies. This challenge might be more problematic, especially in the absence of well-established consensus regarding appropriate educational practices (Dunlap et al.2008).

Because of these documented challenges, many investi-gative research studies worldwide have attempted to explore parents’ perceptions regarding the services provided for their children with autism. The main purpose of these studies was to gain practical understanding about the suitability, utility, and functionality of these services (i.e., appropriateness and effectiveness). Although the majority of the literature con-centrates on the western societies, researchers in the Arab World and the Middle East region have recently begun exploring topics related to children with autism and their parents. For example, Crabtree (2007) stated ‘‘formal services provided for children with disabilities in Jordan, Lebanon, and Palestine are usually at a rudimentary level due to factors related to socioeconomic problems and political conflict’’. She also added ‘‘formal services in Arabian Gulf countries are more constrained by social perceptions of disability and lack of suitably qualified professionals’’ (p. 50).

Due to the previous mentioned factors, it might be acceptable to indicate that providing services for children with disabilities (including children with autism), in most of the Middle Eastern countries, is facing great challenges and is in need of continuous development. Thus, exploring the perceptions of parents is necessary and important in order to improve the level of services provided for children with autism and their families. The existing literature on parental perceptions was mainly presented in two major trends. The first trend gives a thorough report on the types, numbers, and efficacy of services as explored by parents. The second trend tried to socially validate these services using parents’ evaluations (e.g., parent’s satisfactions). In the following sections, we provide an overview of the lit-erature conducted in both trends, as well as the results and the recommendations made in the literature.

Parents Reports of Services Numbers, Types, and Efficacy

Several investigative research studies have reported the numbers, types, and efficacy of services utilized by parents of children with ASD. Some of these research studies indicated that children with autism may receive more educational and health services compared to other children (Bitterman et al.2008).

Other studies indicated that parents of children with ASD utilize an average of seven to nine different types of therapies or treatments (Hess et al. 2008; Green et al. 2006; Kohelr 1999). These therapies were educational or behavioral, health/medical, and pharmacological (Rogers and Vismara 2008; Wong and Smith 2006). Green et al. (2006) developed an Internet survey to identify treatments used by parents of children with autism in 17 different countries. Results of the study revealed parents, on aver-age, reported using seven different types of treatments, such as speech therapy, visual schedules, sensory integra-tion, and applied behavior analysis (p. 70).

Within the Middle East region, Senel (2010) surveyed 38 Turkish parents regarding their use, views, and experi-ences with Complementary and Alternative Medicine treatments (CAM). Five common CAM treatments were listed as: vitamins and minerals, special diets, sensory integration, other dietary supplements, and chelation. Results also emphasized some of the negative aspects of using CAM, such as being expensive, difficult to apply, and harmful.

In addition, Mohan (2009) surveyed the opinions of 28 parents of children with autism in Dubai regarding the availability, quality, uptake, and the need for genetic ser-vices and other relevant serser-vices (e.g., related serser-vices). Results showed that, alongside the need for more organi-zations and types of genetic services, parents expressed the need for more services in areas of autism specialty clinics, family services, early intervention, social skills training, and diagnostic services.

Overall, studies conducted in the first trend have con-sidered new emerging issues and have recommended them for further explorations. These issues included: (1) services need to be evidence-based and represent best-practices (Hess et al. 2008); (2) parents need for guidance in the decision-making process to select treatments for their children (Green et al.2006); (3) parents’ need for objective measures to effectively assess their children’s responsive-ness to treatments; and (4) the need for careful examination of treatments efficacy and the meaning of improvement in light of placebo and cost of treatments effects (Goin-Kochel et al.2009).

Parents’ Evaluations of Services

Parents’ Satisfactions

2008; McConachie and Robinson 2006). Starr and Foy (2010) categorized studies on parents’ satisfaction into three types: (1) generic, in which parents of children with ASD were included with other categories (e.g., learning disabilities); (2) specific, in which only parents of children with ASD were studied; and (3) comparative, in which parents of children with ASD were compared with other parents of children with disabilities such as Down Syn-drome (p. 2). Regardless of the research category, Starr and Foy mentioned ‘‘findings of these studies were remarkably similar despite the passage of time and different countries in which the research was conducted’’ (p. 2).

Despite the fact that satisfaction was reported in some of these studies, dissatisfaction had the greater focus in the literature (e.g., Montes et al. 2009). Mackintosh et al. (2012) surveyed 486 parents of children with ASD in terms of their likes and dislikes about treatments used with their children. Results revealed that 70 % of parents indicated more dislikes than likes with treatments provided for their children (p. 59). Bitterman et al. (2008) found that 91 and 96 % of parents of children with ASD were satisfied with the type of services received by their children. However, for certain aspects of services, parents of children with ASD reported less satisfaction especially with the amount of time their children spent with typically developing peers, the amount of time spent in regular classroom, and the need for more types of services that should be provided through the school district (p. 1513).

In addition, Crabtree (2007) studied 15 mothers of children with developmental disabilities in the State of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Results revealed that the majority of parents in the study reported dissatisfaction with the services provided for their children. Parents also reported some concerns about the adequacy of speech and rehabilitation services, the lack of profession-alism among staff, and the high demand on parents to advocate and mediate with the system to gain the best of services for the child and the family (p. 58).

Overall, studies in this area have identified some sources that might contribute to parents’ satisfaction and consid-ered them emerging issues in need for further investigation. These sources included: (1) the intensity and suitability of services (Bitterman et al. 2008; Mackintosh et al. 2005); (2) the characteristics and credentials of specialists work-ing with children (e.g., their enthusiasm, knowledge, and level of expertise) (Starr et al.2001; Sperry et al.1999); (3) the overall collaboration, communication, and partnerships with parents (Mackintosh et al.2012; Green2007); (4) the availability and continuity of services (Ruble et al. 2005; Krauss et al.2003; Kohelr1999); and (5) the cost or annual expenditures of services (e.g., Liptak et al.2006; Ja¨rbrink et al.2003).

Services Accessibility

Access to services was another topic explored by studies that aimed at evaluating the current services provided. In this venture, researchers were interested in exploring the different sources used by parents to locate services, and the difficulties they face in accessing them. In this regard, Green (2007) identified four general sources of information used by parents of children with ASD to locate the ser-vices: (1) personal relationships (other parents of children with autism, family members, and friends), (2) professional help (physicians, educators, and others), (3) published resources (books, journals, and web pages), and (4) group gatherings (conferences, workshops, and support group meetings).

Montes et al. (2009) concluded that ‘‘parents of children with ASD were three times more likely to report difficulties accessing community and school health services their children needed, compared with parents of other children with special health care needs-(CSHCN)’’ (p. 412). Addi-tional studies addressed other difficulties, such as long waiting lists, lack of available specialists, and bureaucracy in procedures (Mackintosh et al. 2012; Ruble et al.2005; Sperry et al. 1999).

Therefore, considering the aforementioned findings, service providers and policy makers could potentially gain insights into the field of autism and its services by inves-tigating the perceptions of parents of children with autism in Jordan. By doing so, it could enable them to understand and evaluate the current status of services, reinforce them, or provide additional types of services to include the entire family (e.g., family support organizations, formal infor-mation consultation services, and family counseling ser-vices) as well as the entire community (e.g., community awareness and attitudes).

The Present Study

In Jordan, no specific statistics are available to document the total number of children with autism or the number of children being educated or served. In 2010, the Higher Council for the Affairs of Persons with Disabilities (HCAPD) in Jordan published a reference book (in Arabic) called ‘‘The Index of Special Education Institutions.’’ This Index provided information about 266 special education institutions that provide services for all children with spe-cial needs in Jordan. Only four institutions were mentioned in the Index to be specialized in serving children with autism.

teaching instructions (special education); (2) speech, occupational, and physical therapies (related services); (3) medical or health services (a pediatrician visits the tution periodically); (4) transportation between the insti-tutions and children’s homes; (5) parent training workshops, and (6) residential services.

Unfortunately, no studies in Jordan have been conducted to examine the perceptions of parents pertaining to the current services provided (e.g., accessibility methods and difficulties, parents’ satisfaction, and needs for new types of services). Therefore, the current study aims to survey the parents of children with autism to investigate their per-ceptions with current services provided in Jordan. Like other studies (e.g., Mohan 2009; Montes et al. 2009; Kohelr1999), this study is descriptive in nature and utilizes a questionnaire to investigate the perceptions of parents. Using survey research might be adequate for this study since it is the first one to be implemented in Jordan and it is intended to solicit the perceptions of parents at the moment. Accordingly, this study answers the following research questions:

1. What types of services are being received by parents currently?

2. What are the sources of information used by parents to locate these services?

3. What difficulties do parents face when locating these services?

4. How satisfied are the parents regarding the services currently received?

5. What are the most needed services perceived by parents in Jordan?

Method

Setting and Participants

A convenient sample of 60 families participated in this study. Participants were recruited from the four special education institutions specified in the Index (HCAPD 2010). All four institutions were private, separate facilities that typically serve children with autism. Two of them provided residential services for additional fees.

The recruitment process entailed a number of sub-sequent steps. First, the first author visited each institution and met with the administrators to explain the purposes of the study, the characteristics of prospective participants, and the procedures of the study. Second, a contact list of prospective families was obtained from each institution, which included basic information about each family (names, addresses, and phone numbers). Third, a total of 93 families were listed and went through a selection process.

The selection criteria was based on the following: (1) having at least one child with autism in the family, (2) child age ranging from 5 to 18 years, and (3) at least one of the parents is alive.

The selection process narrowed the list to 85 parents. Each institution then announced a call for a meeting with these parents by sending a flyer via children’s bags. The flyer explained the purpose of the meeting, date, time, location, and a brief summary of the study. The meeting was held in one of the institutions for the following rea-sons: (1) the institution is the biggest one in size among the other institutions, (2) the institution offered to provide free transportation for parents (if needed), and (3) the institution has an auditorium that is equipped with the needed tech-nical equipments (e.g., computer, slideshow, speakers and microphones). The meeting took place in the evening and only the parents and the authors of the article were avail-able on site. A total of 60 parents, who voluntarily decided to participate in the study, attended the meeting and signed a consent form.

Table1 presents the participants demographics. Out of the 60 families, 40 (66.7 %; mean age=41 years,

SD=9.8) identified their relationship as mothers, 11 (18.3 %; mean age=42 years;SD =9.4) as fathers, and 9 (15 %; mean age =34;SD=1.1) as both living parents. The mean age of all parents was 41.1 years (SD=11.59). Their age ranged from 23 to 61 years. All families indi-cated having only one child with autism. Children with autism were 45 males (75 %; mean age=10.3 years;

SD=3.70) and 15 females (25 %; mean age=9.6 years;

SD=3.99). The overall mean age of children was ten years (SD=3.75). Their age ranged from five to 18 years. 48.3 % (n=29) of children were judged by their parents as being verbal, while 51.7 % (n=31) as nonverbal (see Table1 for more details).

Research Instrument

Mackintosh et al. (2005) studies. The section also included additional space for parents to express any difficulties they encountered while locating or accessing these services.

The fourth section included 20 items using a five-point Likert scale that ranged from ‘‘not very satisfied’’to ‘‘very satisfied’’ that asks parents to rate their satisfaction with the currently received services (see Table4for a list of items). Items in this section were taken and reframed from reviewing relevant studies (e.g., Starr et al.2006; Whitaker 2007; Kohelr 1999). The last section of the questionnaire used an open-ended question format asking parents to list what they perceived as needed services besides the current

provided ones. The purpose of this section was to direct the attention toward any new types of services that might be needed for future considerations.

A panel of 6 professors in the fields of special education and educational psychology were asked to review the questionnaire to assess its validity. A cover letter was attached to the questionnaire and explained the research purposes, the origins of the items (including a full text of the reviewed articles from the literature), and an overview of the entire methodological procedures. The review panel confirmed the suitability of the questionnaire to the purpose Table 1 Participants demographics

Less than 30 years 12 (20)

30–45 21 (35)

Above 45 27 (45)

Educational level

Below high school 7 (11.7)

High school 10 (16.7)

Number of years in educational settings

Less than 3 years 15 (25)

3–5 years 31 (51.7)

More than 5 years 14 (23.3)

a Classification made based on parents judgments

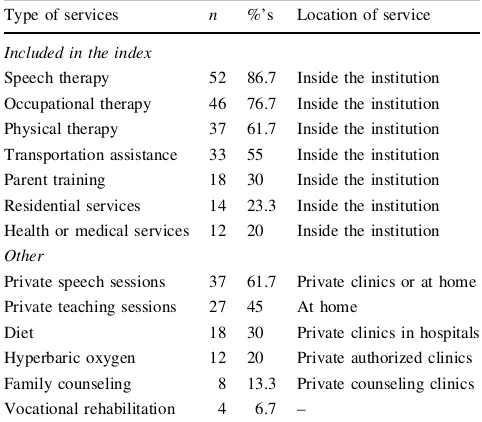

Table 2 Percentages of parents reported received services and their locations

Type of services n %’s Location of service

Included in the index

Speech therapy 52 86.7 Inside the institution Occupational therapy 46 76.7 Inside the institution Physical therapy 37 61.7 Inside the institution Transportation assistance 33 55 Inside the institution Parent training 18 30 Inside the institution Residential services 14 23.3 Inside the institution Health or medical services 12 20 Inside the institution

Other

Private speech sessions 37 61.7 Private clinics or at home Private teaching sessions 27 45 At home

Diet 18 30 Private clinics in hospitals Hyperbaric oxygen 12 20 Private authorized clinics Family counseling 8 13.3 Private counseling clinics Vocational rehabilitation 4 6.7 –

Table 3 Percentages of parents’ ratings of services locating methods

Accessibility method Parents responses

Yes

n(%) No

n(%)

Governmental agencies (e.g., Higher Council) 47 (78.3) 13 (21.7) Other parents of children with autism 37 (61.7) 23 (38.3) Internet resource (e.g., facebook) 31 (51.7) 29 (48.3) Professionals in child’s institute 28 (46.7) 32 (53.3) Private consultation agencies 25 (41.7) 35 (58.3) Media resource (newspapers, flyers, TV

advertisement)

24 (40) 36 (60)

By chance 22 (36.7) 38 (63.3)

Other professionals (e.g., therapists, medical doctors)

15 (25) 45 (75)

Conferences/workshops 14 (23.3) 46 (76.7) Family member (including extended family) 12 (20) 48 (80) Research journals 6 (10) 54 (90)

Books 3 (5) 57 (95)

of the study with minor modifications in language struc-ture. They also suggested distributing the questionnaire among the four administrators of the special education institutions participating in the study to obtain more feed-back regarding its suitability.

All needed modifications in language structure were made and revised by an Arabic language specialist. The modified version of the questionnaire was given again to the professors to ensure that the language structure was appropriate. Two weeks later, the questionnaire was dis-tributed to administrators taking into account the same procedures followed by the panel. All administrators highlighted the importance of the topic under investigation and the suitability of the questionnaire to the purposes of the study.

Finally, a pilot testing of the questionnaire implemented on seven families (not included the sample) revealed that the questionnaire was appropriate to measure parents’ perceptions. Parents’ asked for minor modifications in the language structure of the items included in section four of the questionnaire. They also suggested each section be presented separately with its instructions in a specific frame with borders which would separate the sections from each other.

All modifications were revised and implemented. The same parents were then asked for the second time to indicate if the new modifications improved the suitability of the questionnaire. Indeed, the questionnaire was con-firmed to be ready for use in the study. To obtain reliability indicators, a Cronbach Alpha was computed for the items included in section four and was found to be 0.819.

Data Collection

Copies of the questionnaire forms were personally delivered to the administrator of each institution participating in this study. They were asked to distribute the questionnaires to parents who previously agreed to participate in the study. In this case, parents should have received a sealed envelope containing the questionnaire form with a cover letter explaining the purposes and the importance of the study. The instructions on the cover letter asked parents to fill out the forms, insert them in the envelopes, seal the envelopes, and send them back to the institutions. In addition, the instructions asked parents to discard the received envelopes if they were unsealed or there was evidence of tampering. In this case, parents can immediately contact the first author for help using the cell phone number provided.

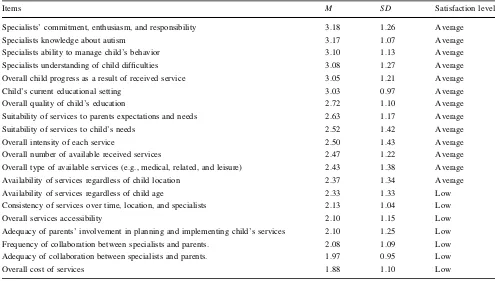

Table 4 Parents’ responses on section four items ranked by means from highest to lowest

Items M SD Satisfaction level

Specialists’ commitment, enthusiasm, and responsibility 3.18 1.26 Average

Specialists knowledge about autism 3.17 1.07 Average

Specialists ability to manage child’s behavior 3.10 1.13 Average Specialists understanding of child difficulties 3.08 1.27 Average Overall child progress as a result of received service 3.05 1.21 Average

Child’s current educational setting 3.03 0.97 Average

Overall quality of child’s education 2.72 1.10 Average

Suitability of services to parents expectations and needs 2.63 1.17 Average

Suitability of services to child’s needs 2.52 1.42 Average

Overall intensity of each service 2.50 1.43 Average

Overall number of available received services 2.47 1.22 Average Overall type of available services (e.g., medical, related, and leisure) 2.43 1.38 Average Availability of services regardless of child location 2.37 1.34 Average Availability of services regardless of child age 2.33 1.33 Low Consistency of services over time, location, and specialists 2.13 1.04 Low

Overall services accessibility 2.10 1.15 Low

Adequacy of parents’ involvement in planning and implementing child’s services 2.10 1.25 Low Frequency of collaboration between specialists and parents. 2.08 1.09 Low Adequacy of collaboration between specialists and parents. 1.97 0.95 Low

Overall cost of services 1.88 1.10 Low

Two weeks after the distribution of the questionnaires, each administrator received a phone call reminder from the second author to encourage parents to send back the completed questionnaires as well as to follow up on the collection process. Four weeks later, the second author collected all completed questionnaires, resulting in a response rate of 100 %. One week later, a letter was sent to parents thanking them for their participation and contri-bution to the current study.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS-16.0). Descriptive statistics (e.g., frequencies, means, standard deviations, ranges, and percentages) were presented in the results section. In addition, one-way ANOVA and independent samplesttest were used for testing any statistically significant differ-ences between participants’ demographic variables (e.g., parents’ educational level and socioeconomic status, chil-dren’s age range, communication level, and gender) and the mean number of received services, as well as the overall satisfaction with the items included in section four of the questionnaire. Apvalue of 0.05 was retained as the level for statistical significance in the analysis. The accessibility and difficulties of services and parents’ per-ceived needed services were summarized and presented alongside their frequencies and percentages.

Results

Type of Received Services

Table2 presents parents’ reports of the received services (in order based on percentages from highest to lowest). A total of 14 services were reported as currently being received services. All services mentioned in the Index (HCAPD 2010) as provided services by the four institu-tions were reported as received ones. In addition, parents reported that six additional services (mentioned under the option ‘‘others’’ in the questionnaire) were received and provided outside the institutions. At the time of this study, the mean number of current services being received by parents was 6.3 (SD=1.85) with a range from 2 to 11 services. Specifically, parents received a mean number of 4.5 (SD=1.09; range 2–7) services from their children’s institutions; while 70 % (n=42) of parents received a mean number of 2.5 (SD=1.01; range 1–5) additional services outside the institutions.

Excluding that the four institutions under investigation were merely educational in nature and, thus, provided special education services (i.e., presenting instructions in a

classroom by implementing an IEP via a special education teacher), related services were reported by parents to be the most received services and included receiving speech therapy (86.7 %), occupational therapy (76.7 %), and physical therapy (61.7 %). On the other hand, vocational rehabilitation services (6.7 %), family counseling services (13.3 %), and health or medical services (20 %) were reported to be the lowest received services.

Moreover, 61.7 % of the participating parents indicated receiving extra speech sessions outside the child’s institu-tion (in private clinics or at homes); 45 % received addi-tional special education (teaching) sessions outside the institutions (at home by a private special education tea-cher); 30 % of parents mentioned that their children are on GF/CF diet plan that are monitored by nutritional clinics in private hospitals; 20 % indicated that their children are currently trying Hyperbaric Oxygen therapy in private clinics which are authorized by the Autism Research Institute (following DAN protocol).

Results of one-way ANOVA revealed no significant dif-ferences in the mean number of received services according to parents’ educational level, F(4, 55)=1.87, p =0.716; socioeconomic status F(2, 57)=0.080, p=0.923; chil-dren’s age rangeF(2, 57)=1.73,p=0.186; and number of years in educational settings,F(2, 57)=0.989,p=0.378. In addition, results of independent samplesttest revealed sig-nificant differences in the mean number of services between male (n=45;M=6.60,SD=1.91) and female (n=15;

M=5.47, SD=1.40) children toward male children, t(58)= -2.10,p=0.039. However, results of independent samplesttest that compared the mean number of services in verbal (n=29, M=6.48, SD=1.63) and nonverbal (n=31, M =6.16, SD=2.05) children revealed no sig-nificant difference between both groups, t(58)=0.668,

p=0.507.

Locating Services: Sources of Information and Difficulties

Table3 presents the percentages of parents’ responses regarding each method (sources of information) utilized in locating the services. On average, parents reported using four different methods (range 2–7) to locate the services. As presented in Table3, getting referral from governmental agencies (e.g., the Higher Council, Minis-try of Social Development) was the most common method used by parents. This method is followed by knowing about the services from other parents, using an Internet resource, and receiving information from other professionals working in the child’s institution. On the other hand, using books, research journals, and family members were the least methods utilized by parents (see Table3 for more details).

Additionally, parents were asked if they had faced any difficulties in the process of locating these services. A common difficulty stated by parents was financial in nature. The majority of parents indicated that services were very expensive and exceeded their financial ability (n=52, 86 %). Moreover, parents stated other difficulties that included finding appropriate and specialized services (n=39, 65 %); locating the correct address of services (n=33, 55 %); long waiting lists, paper work, and bureaucracy of the procedures (n =26, 43 %); traveling to services (n =23, 38 %); and receiving services regardless of the child’s age (n=10, 16 %).

Parents’ Satisfaction

Section four in the questionnaire included 20 items that measure parents’ satisfaction with the received services. The overall mean of parents’ satisfaction with all items included in the section was 2.54 (SD =0.53; range 1.88–3.18), reflecting a slight average satisfaction. This was based on dividing parents’ responses into three satis-faction categories: (1) low satissatis-faction category with a range of (1–2.33), (2) average satisfaction with a range of (2.34–3.66), and (3) high satisfaction with a range of (3.67–5.00).

Table4 presents the responses of parents on each item ranked by its mean from highest to lowest with an indi-cation of the satisfaction category of each item. Out of the 20 items, 13 items had a mean of satisfaction within the average satisfaction category; seven items had a mean of satisfaction within the low satisfaction category; and none of the items had a mean within the high satisfaction cate-gory. Among the 13 items presented in the average satis-faction category, items related to the characteristics of specialists (professional and personal) were the items with the highest mean of satisfaction. These items included the enthusiasm and personal commitment of specialist (M=3.18, SD=1.26; n=40, 66.7 %), the specialists’ knowledge about autism (M =3.17, SD=1.07; n=41, 68.3 %), the ability of specialists to manage the child’s behavior (M =3.10,SD =1.13;n=40, 66.7 %), and the specialists’ understanding of the child’s difficulties (M=3.08,SD=1.27; n=36, 60 %).

On the other hand, among the seven items presented in the low satisfaction category, items in the areas of cost of services (M =1.88, SD=1.10; n=15, 25 %), profes-sional-parents collaboration (both adequacy and frequency of collaboration), and adequacy of parents’ involvement in child’s education (M=2.10,SD=1.25;n=16, 26.7 %) were respectively presented with the lowest mean of sat-isfaction in the parents’ responses.

Moreover, when testing for any significant differences in parents’ overall mean of satisfaction on all items included,

according to parents’ and children’s demographics, the results of one-way ANOVA revealed no significant dif-ferences in parents’ overall satisfaction which could be attributed to parents’ level of education, F(4, 55)=1.79,

p =0.144, or socioeconomic status F(2, 57)=0.480,

p =0.621. Similarly, results of one-way ANOVA revealed no significant differences that could be attributed to chil-dren’s age range,F(2, 57)=2.77,p=0.071, or children’s number of years in educational settings F(2, 57)=1.877,

p =0.162. In addition, results of independent samplettest revealed no statistically significant differences between parents overall satisfaction and children’s gender t(58)=0.607, p =0.54, or level of communication abil-ity,t(58)=3.74,p=0.072.

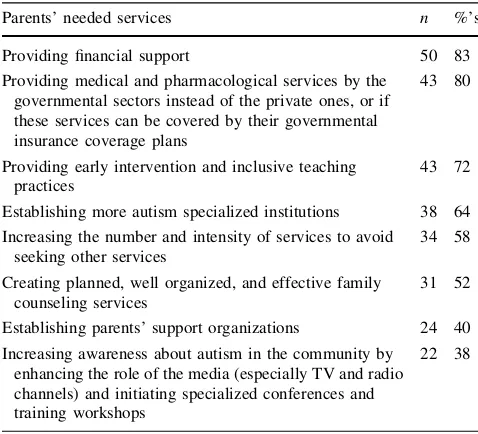

Needed Services

The last section of the questionnaire asked parents to list the most needed services related to autism in Jordan. As presented in Table5, the majority of parents (83 %, n =50) expressed their need for financial support to reduce the financial burden caused by the cost of services. Around (80 %, n=43) of parents believed that health, medical, and pharmacological services (e.g., DAN proto-col) were expensive and were only provided in private clinics. In this manner, parents stated the need for the government to provide them with these services (e.g., Ministry of Health) or to include these services within their health insurance plans currently provided by the govern-ment. Other stated needs included: providing early inter-vention and inclusive teaching, establishing additional autism specialized governmental institutions, providing

Table 5 Percentages of parent’s desires

Parents’ needed services n %’s

Providing financial support 50 83 Providing medical and pharmacological services by the

governmental sectors instead of the private ones, or if these services can be covered by their governmental insurance coverage plans

43 80

Providing early intervention and inclusive teaching practices

43 72

Establishing more autism specialized institutions 38 64 Increasing the number and intensity of services to avoid

seeking other services

34 58

Creating planned, well organized, and effective family counseling services

31 52

Establishing parents’ support organizations 24 40 Increasing awareness about autism in the community by

enhancing the role of the media (especially TV and radio channels) and initiating specialized conferences and training workshops

family services, and enhancing the level of awareness about autism in the community.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the perceptions and experiences of parents of children with autism regarding the current provided services in Jordan. Sixty parents participated in the study and responded to a ques-tionnaire of five sections. Examining parents’ satisfaction is considered beneficial since parents are capable of informing educators about the suitability of the educational programs (Goin-Kochel et al.2009).

A total of 14 services were reported being received by parents in this study. The mean number of the received services at the time of this study was 6.3 (SD=1.85, range 2–11). This mean falls within the range mentioned by other studies (e.g., Goin-Kochel et al.2009; Hess et al. 2008). All services stated in the Index (HCAPD, 2010) were actually received. Six additional services were reported as extra services which were received privately by families in different locations with multiple providers. Although reports of some studies indicated differences in the mean number of services according to the child’s age and level of severity (e.g., Green et al. 2006), results of this study showed no significant differences according to these two factors. This might be attributed to limitations in our sample size, the unequal distribution of participants among these variables, lack of ability to confirm children’s level of severity, and the consideration of children with autism only.

With the exclusion of special education services (since all children are enrolled in special education institutions), related services (including speech, occupational, and physical therapies) were reported to be the most received services; a finding that is similar to results found in other studies (e.g., Kohelr1999). This result might be attributed to factors related to children’s needs, especially if we recognize that autism affects the child’s ability to com-municate and behave within an age manner. In our sample, around 51 % of children were judged to be nonverbal. Therefore, it is expected that the majority of them will need speech language therapy, potentially causing parents to report this service as the most received one.

Parents’ overall satisfaction with services as measured in section four of the questionnaire was slightly on the average category of satisfaction. All items included in the section ranged from the low satisfaction category to the average satisfaction category (see Table4). Unfortunately, none of the items reached the high satisfaction category. Bitterman et al. (2008) stated ‘‘past research and patterns of litigation suggest that parents of children with ASD are not

wholly satisfied with the special education and related services their children receive’’ (p. 1509). Montes et al. (2009) concluded ‘‘parents of children with ASDs reported less access to and more dissatisfaction with school and community health services than other parents with special health care needs’’ (p. 407).

It is expected that issues related to parents’ perception of satisfaction in Jordan could be similar to those mentioned in other countries (e.g., USA, Canada, Flanders, and Brit-ain) where the educational systems, legislations, degree of inclusion and teacher training are different than in Jordan. This result is valid as Starr and Foy (2010) mentioned that ‘‘similarities of parent perceptions across the research lit-erature despite the passage of time and differences in education systems are striking…and even more surprising when considering differences in legislations, degree of inclusion, and teacher training’’ (p. 8). Results of our study highlighted several issues that contribute to parents’ aver-age satisfaction with services provided in Jordan. These issues and their implications will be presented subse-quently hereafter.

First, parents mentioned that receiving services was not unified in one place; rather it consists of multiple places with interactions with multiple providers. This type of service delivery system consists of multiple issues that might be problematic for parents since it impacts their overall experiences with the educational process (Kohelr 1999). For example, 70 % of parents indicated that extra services were being utilized privately outside their chil-dren’s institutions. It is noted that receiving these extra services, alongside the regular fee they already pay to the institutions, increases the financial burden on parents. This financial burden was documented in the literature (Ja¨rbrink et al.2003) and was considered as an important source that might lower parents’ satisfaction (Wang et al. 2012).

In addition, changing the delivery system by unifying the services under one umbrella (e.g., Ministry of Social Development or the Higher Council) might solve the prob-lem. It is important for the government as well as the Higher Council and other stakeholders to consider the financial burden related to the cost of services. Another implication might include a reconsideration of the accreditation process used by the Higher Council in relation to special education institutions. It might be advisable for all institutions to provide comprehensive and evidence-based services. Only the services that have been documented in the field as effective for children with autism should be provided. Other services (e.g., pharmacological) must be provided and monitored under the unified umbrella suggested earlier to ensure their effectiveness as well as to protect parents from what could be called ‘‘unethical costly practices.’’

source that either negatively impacts or positively enhances parents’ satisfaction (Starr and Foy2010). Unfortunately, parents in our study were less satisfied with items that targeted this important topic (see Table4). The perva-siveness of these topics in this research and other studies (e.g., Whitaker 2007; Batten et al. 2006) highlights the need to consider them in the planning and provisioning of education programs for children with autism (Starr and Foy 2010).

Third, contrary to results mentioned in the literature (e.g., Starr and Foy 2010; Renty and Roeyers 2006; Crabtree 2007), the characteristics of specialists, such as commitment, knowledge about autism, the ability to manage the child’s behavior, and the understanding of the child’s difficulties were presented with average level of satisfaction in this study (see Table4). This result might be attributed to the type of service delivery system in which a limited number of institutions and specialists are found in the country, hence making them the only appropriate and available option. Another explanation might be culturally connected to the general feeling of respect that cultural values in Jordan persevere toward teachers.

Fourth, the difficulties faced by parents during the pro-cess of obtaining services are important. Difficulty obtaining services was seen as a major issue connected to parents’ satisfaction (Mackintosh et al.2012). When dif-ficulties are presented, parents’ level of stress, frustration, and discontentment increased (Stoner et al. 2005). This, itself, impacts their sense of satisfaction. These difficulties are anticipated and occurred much more frequently in services with an ASD-specific approach (Renty and Roeyers2006, p. 385).

In the same manner, the methods used by parents for locating services were similar, to some extent, with the methods mentioned by other studies (e.g., Green 2007). However, these methods need greater attention. For example, 51 % of parents in this study depend on Internet resources, 41 % rely on consultations made by private agencies, and 40 % depend on media (e.g., TV or news-paper advertisements) for locating a service. In their study, Mackintosh et al. (2005) discussed the risks that might occur when parents rely on these types of methods. They mentioned that these types of methods provide information that may or may not be reliable or accurate, and are sometimes harmful. Given this result, service providers in Jordan need to develop sensitivity and awareness about these methods in order to help parents gain strong educa-tional experience to the optimal level.

Finally, the perceived needed services stated in Table5 represent parents’ voices for a change in the service delivery system. It is interesting to note the similarities found between the needed services mentioned by parents in this study and the recommendations by Mohan (2009).

Topics such as early intervention, inclusion, family ser-vices, community awareness, financial support, and autism specialized clinics were presented in the study; but they were not exclusive to Jordan alone.

Another implication is directed toward the government and other stakeholders in Jordan to invest in these ser-vices. For example, parents in Jordan mainly complained about the cost of services and the financial burden related to these services, especially when connected to receiving medical and health services. This financial burden should not be found especially when considering Article number 4 mentioned in the Law on the Rights of Persons with disabilities mandated in Jordan in 2007. In this regard, Article number 4 required providing medical therapeutic services and free medical insurance to all persons with disabilities in the country (HCAPD2007). Therefore, the government should consider these services or, at least, include them within its health insurance plans provided for parents.

Finally, it is agreed upon in the field that early inter-vention, inclusion, and family counseling are important services for children with autism (e.g., Starr and Foy2010; Kohelr 1999). Although some inclusive practices have been officially implemented in Jordan (AL Khatib and AL Khatib 2008), children with autism were excluded from them. What is needed is a unified, official, and govern-mental effort to organize, provide, and monitor such types of important services to better serve the children and their families.

Conclusions

delivery system in the country is needed to improve the current situation.

Limitations

It is important to mention that this study has many limi-tations. First, results of the study are limited to its sample size that is drawn from one area in Jordan. This limitation could not be managed, since all special education institu-tions specialized in serving children with autism are loca-ted in that area. Second, designation of children in this study as having autism is based primarily upon their institution’s records. We neither confirm that all children in this study are correctly diagnosed with autism; nor does the nature of the study allow for independent or clinical diagnosis. This is reflected in our inability to confirm children’s level of severity (including their level of com-munication). This inability is attributed to the shortage of assessment measures that are psychometrically available and appropriate to the Jordanian culture.

Third, children included in this study were all educated in segregated settings. No available data confirm any inclusive practices that are provided for children with autism in the country. Therefore, results of this study might be similar or different if other educational settings were taken (or made available) in any future research. Finally, self-reported perceptions are only presented in this study. Starr and Foy (2010) mentioned that confirming whether these perceptions truly reflect what is occurring in the classroom is unknown. In this case, they suggested ‘‘additional research with tri-angulation of data that include teachers’ perceptions alongside observations made in classrooms would strengthen the validity of the results’’ (p. 8).

References

Al Khatib, J., & Al Khatib, F. (2008). Educating students with mild intellectual disabilities in regular schools in Jordan.The Journal of the International Association of Special Education, 9(1), 109–117.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000).Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders(4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. Batten, A., Corbett, C., Rosenblatt, M., Withers, L., & Yuille, R. (2006). Make school make sense: Autism and education: The reality for families today. London, UK: National Autistic Society.

Bitterman, A., Daley, T., Misra, S., Carlson, E., & Markowitz, J. (2008). A national sample of preschoolers: Special education services and parent satisfaction.Journal of Autism and Devel-opmental Disabilities, 38, 1509–1571.

Brewin, B., Renwick, R., & Schormans, A. (2008). Parental perspectives of the quality of life in school environments for children with Asperger syndrome.Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 23(4), 242–252.

Crabtree, S. (2007). Families’ responses to the social inclusion of children with developmental disabilities in the United Arab Emirates.Disability & Society, 22(1), 49–62.

Dunlap, G., Iovannone, R., & Kincaid, D. (2008). Essential compo-nents for effective autism educational programs. In J. K. Luiselli, D. C. Russo, W. P. Christian, & S. M. Wilcznski (Eds.),Effective practices for children with Autism: Educational and support interventions that work (1st ed., pp. 111–137). New York: Oxford University Press.

Goin-Kochel, R., Mackintosh, V., & Myers, B. (2009). Parental reports on the efficacy of treatments and therapies for children with autism spectrum disorders.Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3, 528–537.

Green, V. A. (2007). Parental experiences with treatments for autism.

Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 19, 91–101. Green, V. A., Pituch, K. A., Ichon, J., Choi, A., O’Reilly, M., & Sigafoos, J. (2006). Internet survey of treatments used by parents of children with autism.Research in autism and Developmental Disabilities, 27, 70–84.

Hess, K., Morrier, M., Heflin, L., & Ivey, M. (2008). Autism treatment survey: Services received by children with autism spectrum disorders in public school classrooms. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(5), 961–971. Higher Council for Affairs of Persons with Disabilities (HCAPD).

(2007).The law on the rights of persons with disabilities: Law number 31 for the year 2007. Amman: Author.

Higher Council for Affairs of Persons with Disabilities (HCAPD). (2010).

[The Index of special education institutions educating persons with disabilities in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan]. Amman: Author. Ja¨rbrink, K., Fombonne, E., & Knapp, M. (2003). Measuring the parental, service and cost impacts of children with Autistic Spectrum Disorders: A pilot study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(4), 395–402.

Kohelr, F. (1999). Examining the services received by young children with autism and their families: A survey of parent responses.

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 3, 150–158.

Krauss, M., Gulley, S., Sciegaj, M., & Wells, R. (2003). Access to specialty medical care for children with mental retardation, autism, and other special health care needs.Mental Retardation, 41(5), 329–339.

Liptak, G. S., Orlando, M., Yingling, J. T., Theurer-Kaufman, K. L., Malay, D. P., Tompikns, L. A., et al. (2006). Satisfaction with primary health care received by families of children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 20(4), 245–252.

Mackintosh, V., Goin-Kochel, R., & Myers, B. (2012). ‘‘What do you like/dislike about treatments you’re currently using?’’: A qual-itative study of parents of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders.Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabil-ities, 27(1), 51–60.

Mackintosh, V., Myers, B., & Goin-Kochel, R. (2005). Sources of information and support used by parents of children with autism spectrum disorders.Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 12, 41–51.

McConachie, H., & Robinson, G. (2006). What services do young children with autism spectrum disorder receive. Child: Care, Health and Development, 32(3), 371–385.

Mohan, P. (2009).Autism spectrum disorders in Dubai, United Arab Emirates: Problems in access to comprehensive care. Unpub-lished master thesis, Sarah Lawrence College, Bronxville, NY, USA.

Montes, G., Halterman, J., & Magyar, I. (2009). Access to and satisfaction with school and community health services for US children with ASD.Pediatrics, 124(S4), S407–S413.

Parsons, S., & Lewis, A. (2010). The home-education of children with special needs or disabilities in the UK: Views of parents from an online survey.International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14, 67–86.

Parsons, S., Lewis, A., & Ellins, A. (2009). The views and experiences of parents of children with autistic spectrum disorder about educational provision: Comparisons with parents of children with other disabilities from online survey.European Journal of Special Needs Education, 24, 1–34.

Renty, J., & Roeyers, H. (2006). Satisfaction with formal support and education for children with autism spectrum disorder: The voices of the parents. Child: Care, Health and Development, 32(3), 371–385.

Rogers, S. J., & Vismara, L. A. (2008). Evidence-based comprehen-sive treatments for early autism.Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 8–83.

Ruble, L., Heflinger, C., Rnfrew, J., & Saunders, R. (2005). Access and Service Use by children with autism spectrum disorders in medicaid managed care.Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(1), 3–13.

Senel, H. (2010). Parents’ views and experiences about complemen-tary and alternative medicine treatments for their children with autistic spectrum disorder.Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 494–503.

Sperry, L., Whaley, K., Shaw, E., & Brame, K. (1999). Services for young children with autism spectrum disorders: Voices of parents and providers.Infant and Young Children, 11(4), 17–33. Starr, E., & Foy, J. (2010). In parents’ voices: The education of children with autism spectrum disorders.Remedial and Special Education,33(4), 1–10.

Starr, E., Foy, J., & Cramer, K. (2001). Parental perceptions of the education of children with pervasive developmental disorders.

Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Develop-mental Disabilities, 36(1), 55–68.

Starr, E., Foy, J., Cramer, K., & Singh, H. (2006). How are schools doing? Parental perceptions of children with autism spectrum disorders, down syndrome, and learning disabilities: A compar-ative analysis.Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 41, 315–332.

Stoner, J., Bock, S., Thompson, J., Angell, M., Heyl, B., & Crowley, E. (2005). Welcome to our world: Parent perceptions of interactions between parents of young children with ASD and education professionals.Focus on Autism and Other Develop-mental Disabilities, 20(1), 40–51.

Wang, J., Zhou, X., Xia, W., Sun, C., Wu, L., Wang, J., et al. (2012). Parent-reported health care expenditures associated with autism spectrum disorders in Heilongjiang province, China. BMC Health Services Research, 12, 7.