Strategic context and patterns of IT infrastructure

capability

q

M. Broadbent

a,*, P. Weill

b, B.S. Neo

caGartner Group Pacific, 2nd Floor, 620 Bourke Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3001, Australia bMelbourne Business School, The University of Melbourne, 200 Leicester Street, Carlton,

Victoria 3053, Australia

cNanyang Technological University, Nanyang Avenue, Singapore 2263, Singapore

Accepted 23 September 1999

Abstract

The importance of a firm’s information technology (IT) infrastructure capability is increasingly recognised as critical to firm competitiveness. Infrastructure is particularly important for firms in industries going through dynamic change, for firms reengineering their business processes and for those with multiple business units or extensive international or geographically dispersed operations. However, the notion of IT infrastructure is still evolving and there has been little empirically based research on the patterns of IT infrastructure capability across firms.

We develop the concept of IT infrastructure capability through identification of IT infrastructure services and measurement of reach and range in large, multi-business unit firms. Using empirical case research, we examine the patterns of IT infrastructure capability in 26 firms with diverse strategic contexts, including different industry bases, level of marketplace volatility, extent of business unit synergies and the nature of firm strategy formation processes. Data collection was based on a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods with multiple participants.

More extensive IT infrastructure capability is defined as a combination of more IT infrastructure services and more reach and range. More extensive IT infrastructure capability was found in firms where: (i) products changed quickly; (ii) attempts were made to identify and capture synergies across business units; (iii) there was greater integration of information and IT needs as part of planning processes; and (iv) there was greater emphasis on tracking the implementation of long term strategy. These findings have implications for both business and technology managers particularly in regard to how firms link strategy and IT infrastructure formation processes.q1999 Elsevier Science B.V. All

rights reserved.

Keywords: Information systems planning issues; Information systems investment; Information systems infrastructure; Information infrastructure; Business strategy

Journal of Strategic Information Systems 8 (1999) 157–187

0963-8687/99/$ - see front matterq1999 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

PII: S 0 9 6 3 - 8 6 8 7 ( 9 9 ) 0 0 0 2 2 - 0

www.elsevier.com/locate/jsis

q

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 17th International Conference on Information Systems in December 1996 in Cleveland Ohio, where it won the Best Paper Award.

* Corresponding author. Tel.:161-3-9203-3514; fax:161-3-9203-3501.

1. The importance of information technology infrastructure

Although there is no single universally accepted definition of business strategy (Mintzberg and Quinn, 1991) a number of scholars emphasise the importance of choice. Porter (1996) argues that competitive strategy is about being different requiring the choice of a different set of activities and capabilities to deliver a unique mix of values. Markides (1999) identifies three dimensions where firms must make these choices: who to target as customers, what products to offer and how to undertake the related activities efficiently. Core competencies are at the centre of these strategic choices (Hamel and Prahalad, 1989; Kay, 1993) to create and sustain advantages and implement effectively. Information technology (IT) infrastructure capability is a firm resource (Barney, 1991) and potential core competence that is difficult to imitate requiring a fusion of human and technical assets.

IT infrastructure is increasingly seen as a fundamental differentiator in the competitive performance of firms (McKenney, 1995). New competitive strategies (Boynton et al., 1993) and progression through higher levels of organisational transformation (Davidson and Movizzo, 1996) each require major IT infrastructure investments. IT infrastructure capabilities underpin the emergence of new organisa-tional forms (Davidow and Malone, 1992), such as global virtual corporations (Miller et al., 1993), facilitate electronic commerce via the development of virtual value chains (Rayport and Sviokla, 1995) and are part of a firm’s strategic choices (Porter, 1996; Markides, 1999). IT infrastructure capability is critical to globally competing firms (Clemons et al., 1989; Neo, 1991) to provide connectivity and integration.

IT infrastructure can be a significant barrier or enabler in the practical options available to planning and changing business processes (Grover et al., 1993; Wastell et al., 1994). The support of enabling technologies and platforms is an important contributor to success-ful business process change (Caron et al., 1994; Furey and Diorio, 1994). Cross functional process changes require a shift in the role of the IT function from being guardians of information systems to providing infrastructure support, particularly in the form of data management expertise (Dixon et al., 1994; Earl and Kuan, 1994) and connectivity across areas and computer platforms.

While the significance of IT infrastructure is now being recognised (Davenport and Linder, 1994), this is often as a by-product or retrospective analysis of the success of strategic initiatives or process change implementations. Knowledge of the value of IT infrastructure remains largely “in the realms of conjecture and anecdote” (Duncan 1995, p. 39).

2. The dimensions of IT infrastructure

Over the past five years, issues associated with IT infrastructure have consistently been identified as a key concern of IS management (Broadbent et al., 1994; Pervan, 1994; Brancheau et al., 1996). IT infrastructure is a major business resource and is a source for attaining sustainable competitive advantage (Keen, 1991; McKenney, 1995). However, few works have had the notion of IT infrastructure as their central focus.

IT infrastructure is the enabling base of shared IT capabilities which provide the foundation for other business systems (McKay and Brockway, 1989). This capability includes both the internal technical (equipment, software and cabling) and managerial expertise required to provide reliable services (McKay and Brockway, 1989; Weill, 1993). This complex set of technological resources is developed over time and its precise description and value are difficult to define (Duncan, 1995).

IT infrastructure differs from applications in its purposes as a base for future applica-tions rather than current business functionality, and in the way in which it must cope with the uncertainty of future needs (Grossman and Packer, 1989). IT infrastructure is usually justified and financed differently from applications, its benefits are often hard to quantify (Parker and Benson, 1988; CSC Index, 1993) and are typically large investments requiring board level or executive management approval (PE International, 1995).

The major components of IT infrastructure are hardware platforms, base software plat-forms, communications technology, middleware and other capability that provides shared services to a range of applications and common handling mechanisms for different data types (Turnbull, 1991; Darnton and Giacolette, 1992). IT infrastructure capability is usually coordinated by the corporate information systems (IS) group (Weill and Broadbent, 1994) and can be sourced in a variety of ways including insourced, outsourced and co-sourced (PE International, 1995).

The purposes of building IT infrastructure is to support the commonality between different applications or uses (CSC Index, 1992) facilitating information sharing across and outside the enterprise, cross-functional integration (Darnton and Giacolette, 1992) and to obtain economies of scale. IT infrastructure flexibility refers to the degree to which its resources are shareable and reusable (Duncan, 1995) and the speed and cost with which a firm can respond to changes in the market place. Building in flexibility adds cost and complexity but provides a business option that may be exercised in the future (Kambil et al., 1993), widening the variety of customer needs a firm can handle without increased costs (Weill, 1993). Firms take different approaches to IT infrastructure invest-ments depending on strategic objectives. Some firms focus on costs savings via economies of scale, while others firms focus on current strategy needs or longer-term requirements for flexibility (Venkatraman, 1991; Weill, 1993).

countries. Thus a shared IT infrastructure rather than separate IT platforms and services is required (Keen, 1991).

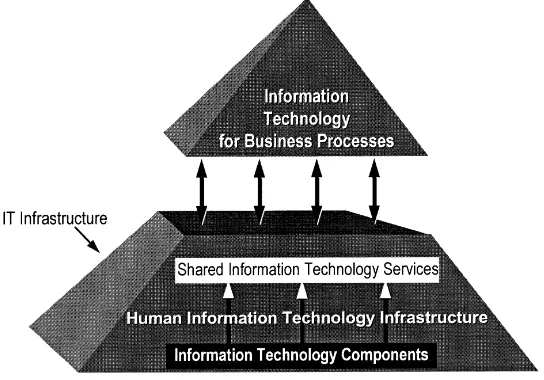

The mortar which binds all the IT components into robust and functional services includes a specific body of knowledge, skill sets and experience embodied in the human infrastructure (McKay and Brockway, 1989; Davenport and Linder, 1994). This human component provides the policies, architectures (Keen, 1995), planning, design, construction and operations capability necessary for a viable IT infrastructure.

3. IT infrastructure capability

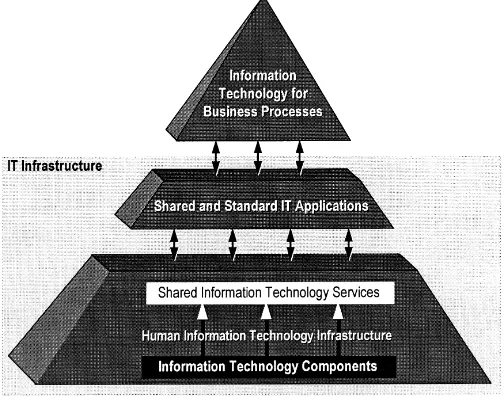

Drawing on conceptual and related empirical work, we define IT infrastructure as:

the base foundation of budgeted-for IT capability (both technical and human), shared throughout the firm in the form of reliable services, and centrally coordinated.

We contend that such capability is a firm resource (Barney, 1991) which is difficult to imitate as it is created through a unique fusion of technology and human infrastructure (Keen, 1991).

The various elements of IT infrastructure are presented in Fig. 1 (drawing particularly on McKay and Brockway, 1989; Weill 1993; Weill and Broadbent, 1994). At the base of this model are the IT components, such as computers and communications technologies, which are commodities and readily available in the marketplace. The second layer comprises a set of shared services such as management of large scale data processing, provision of an extranet capability, or management of a firm-wide customer database. The base level IT components are converted into useful IT infrastructure services by the human IT infrastructure composed of knowledge, skills, policies and experience. This human

infrastructure binds the IT components into a reliable set of shared IT infrastructure services. The process of binding components into a service can be achieved by an internal IS group or by an outsourcer.

Evidence for IT infrastructure capability can be found in the nature of IT infrastructure services in a firm. The notion of IT infrastructure and thus shared services leads to an identifiable set of services centrally coordinated and offered across firms in multi-business unit firms (Weill et al., 1995). The set of IT infrastructure services is relatively stable over time and focused on the long-term strategic intent (Hamel and Prahalad, 1989, 1994) of the firm. However, the systems required for business processes (i.e. applications) are expected to change regularly to meet the needs of current strategies of specific businesses within the firm.1

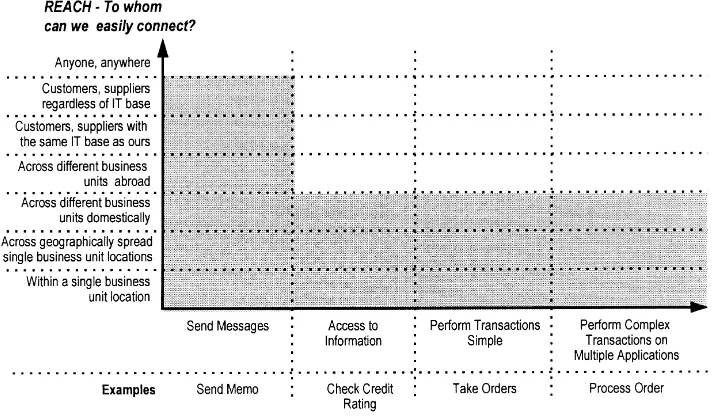

The business connectivity of IT infrastructure can be defined in terms of ‘reach and range’ (Keen, 1991; Keen and Cummins, 1994). ‘Reach’ refers to locations that can be connected via the infrastructure, while ‘range’ determines the level of functionality (i.e. information and/or transaction processing) that can be shared automatically and seamlessly across each level of ‘reach’.

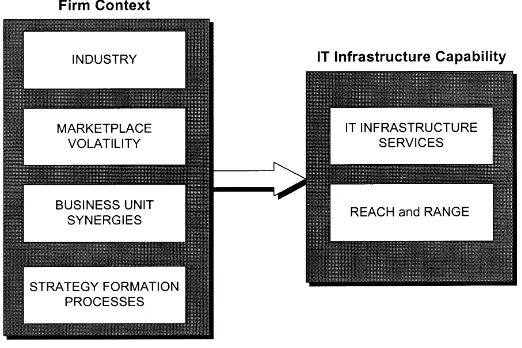

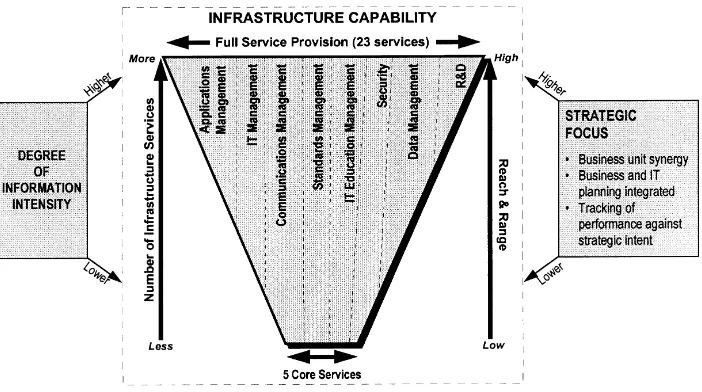

4. Model and propositions

Drawing on the literature, we identified four aspects of firm context for investigation when assessing patterns of IT infrastructure capability: industry differences, the level of marketplace volatility, the extent of synergies amongst business units in firms, and char-acteristics of strategy formation processes in firms. The model for the study, which evolved from the literature analysis and initial concept formulation, is presented in Fig. 2.

1While we are focussing on firm-wide IT infrastructure services, it is also possible to envisage business unit

Constructs which appear in italics in the next paragraphs are part of the model in Fig. 2.

IT infrastructure capability:Key attributes of IT infrastructure capability are the extent

to which it is shareable and reusable across the firm (Duncan 1995). We define IT infra-structure capability as a combination of functionality and connectivity. Functionality is identified by theIT infrastructure servicesoffered firm-wide. Connectivity is identified by the infrastructurereach and range. Taken together services and reach and range provide a practical measure of IT infrastructure capability.

Thus IT infrastructure capability comprises two elements:

Functionality

1. The number of firm-wide infrastructure services, with a higher number indicating a high level of capability.

2. The nature of those services. For example a larger number of services in the area of communications management indicates a high level of capability in communications management.

Connectivity

3. The extent of reach and range with a higher reach and range indicating a higher level of capability.

4.1. Propositions

Seven propositions explore the linkage of patterns of IT infrastructure capability and firm strategic context.

4.2. IT infrastructure capability and industry differences

The demand for IT infrastructure capability will vary amongst industries due to different levels of information intensity (Porter and Millar, 1985). Industries generally differ in the rates of change, extent of cross selling of products, cross ownership of customers and similarly of processes. Bradley et al. (1993) identify three industries at the forefront of change:finance,manufacturingandretail.Financeis posited to have more infrastructure due to higher integration between business units and more rapid product development cycles. In finance firms, customers often utilise several products from different parts of the firm such as loans and insurance. Thus firms desire a picture of the entire relationship with a customer. Concurrently, finance firms are experiencing rapid change due to ongoing internationalisation of the finance industry and the need to build infrastructures to support clients whose businesses are expanding globally.Retailing is posited to have extensive infrastructures due to commonality of processes, (e.g. supply chain management across different business units or brands).

Proposition 1: Firms operating in different industries have different requirements for information, and thus different patterns of IT infrastructure capabilities.

4.3. IT infrastructure capability and marketplace volatility

1995). Firms which value flexibility because ofmarketplace volatilityare expected to have more extensive IT infrastructure capabilities because of business requirements to respond to rapid changes in the marketplace (Quinn, 1992). Such changes often require improved customer service and increasingly emphasise higher interdependence between business units; thus leading to a stronger impetus for shared firm-wide services. Information technology infrastructure investments “provide real options and flexibility to managers to enable them to position the firm to take advantage of environmental uncertainties” (Kambil et al., 1993, p. 175). IT infrastructure therefore is a major determinant of a firm’s ‘business degrees of freedom’ as its business functionality “will determine which IT dependent products and services are practical and which are not” (Keen, 1991, p. 18).

Proposition 2: Firms with greater emphasis on the need to change products more quickly will have more extensive IT infrastructure capabilities.

Proposition 3: Firms which tend to make resource decisions based on current needs will have less extensive IT infrastructure capabilities.

Proposition 4: Firms with greater emphasis on flexibility to meet changing needs of their marketplace will have more extensive IT infrastructure capabilities.

4.4. IT infrastructure capability and business unit synergies

The increasing importance of relationship-based services and ‘single point of customer contact’ raises the stakes for information sharing and common transaction processing across the business to capitalise on opportunities for cross-selling and synergy. Firms where business units share products, customers, business processes, suppliers or expertise are expected to provide more extensive firm-wide IT capability to gain benefit from cross-business unit synergies. This business flexibility requires IT capability (Duncan, 1995) to share information across products, services, locations, companies and countries. To realise these synergies requires a common infrastructure and an end to separate IT platforms for related business activities in the same firm (Keen, 1991).

Proposition 5: Firms with greater emphasis on identifying synergies between business units will have more extensive IT infrastructure capabilities.

4.5. IT infrastructure capability and strategy formation processes

Providing extensive information technology capabilities in firms indicates a high level of consideration of IT in business strategies (Henderson and Venkatraman, 1992). Align-ment of business and information technology strategies requires strategy formation

processes (Hax and Majluf, 1988; Segev, 1988) which encompass and integrate both

long term business and technology developments (Broadbent and Weill, 1993; Powell and Dent-Micallef, 1997). Successful strategy formation processes in the complex environment of multi-business unit firms require a high level of planning sophistication to achieve their goals, particularly the goal of creating synergy between business units (Pearce et al., 1987) or alignment of IT infrastructure with business strategy.

Proposition 7: Firms with greater emphasis on tracking the success of implementation of strategic intent will have more extensive IT infrastructure capabilities. The indicators of the extent of a firm’s emphasis are: (i) the level of reporting progress against strategic intent; (ii) whether achievements are actively measured; and (iii) whether those responsible are identified.

5. Research approach and method

5.1. Research approach

We examined the patterns of firm-wide IT infrastructure capability in large multi-business unit firms using a multiple case design (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 1994). We adopted a multiple case design, as it is an intense empirical approach suited to the study of emerging and complex phenomena (Yin, 1994). Our research approach was to first operationalise the concept of IT infrastructure capability. Then we examined the patterns of IT infrastructure capability via a series of research propositions in 26 firms with different strategic contexts using a combination of qualitative (e.g. grouping and construct development) and quantitative (tabulations and correlations) data and analysis. After evaluating and discussing the propositions we then review our approach to operationalizing IT infrastructure capability reflecting on the empirical work and make suggestions for the future conceptualisation.

5.2. Method

Intensive on-site work was required to test the seven propositions and to understand the strategic context of each firm and the nature of its IT infrastructure capability. We selected 26 leading firms (in seven countries) in the finance, retail and manufacturing industries for investigation. These three industries are at the forefront of change in industry structure due to the combination of technological innovation and the accelerating pace of globalisation (Bradley et al., 1993). They also provide a contrast in their strategic use of information and information technology (Porter and Millar, 1985; Cash et al., 1992).

In order to focus on firm-wide IT infrastructure services in complex settings, the firms selected met the following criteria:

1. Comprised at least two autonomously managed business units with distinct sets of products or customers.

2. Were in the top five in their industry by market share in their region.

3. Had historical IT investment data and IT infrastructure services information that could be made available to the researchers.

4. As a group of firms, provided an international perspective.

The participating firms are listed in Appendix A by region.

5.3. Data collection

The seven propositions required a study design involving a combination of quantitative and qualitative data collection (Kaplan and Duchon, 1988; Benbasat and Nault, 1990) and analysis methods. There were multiple respondents in each firm to achieve triangulation of data and insights. Data were collected by means of interviews, the completion of extensive response forms by participants, analysis of organisational documentation (e.g. memos, internal reports) and notes of presentations made by executive managers about recent strategy and technology developments.

In each firm there were a minimum of four participants some of whom were interviewed on multiple occasions. The four participants were the Chief Information Officer (CIO), IS executives from at least two different business units, and a corporate executive who was able to provide a strategic perspective across the firm as a whole. This person was one of the CEO, the Chief Finance Officer, Chief Operating Officer or the Director of Strategy. (This person is referred to hereafter as the Corporate Executive or CE). In each firm the CIO was interviewed about the IS arrangements in the firm and the decision-making process relating to both business and IT strategy. Four different response forms to be completed by the participants were then distributed. When these were completed and returned, interviews were held with each manager to explore the issues in more depth.

Data and documentary material gathered at the time of site visits were combined with public information sources to generate a vignette on each firm (of about eight pages in length). The vignette included information about the firm’s strategy and strategy formation processes, structure, business units, organisational arrangements for the IS functions and the extent and nature of the firm’s IT infrastructure capabilities. These vignettes were checked for accuracy by each firm and approved.

5.4. Constructs

5.4.1. Strategic context

Data came from nine questions with five-point Likert scales plus an open ended ques-tion on strategic intent answered by both the CIO and CE. There was generally a high correlation between CIO and CE responses, with two exceptions (see Appendix B for questions used and for coefficients of correlation between CIO and CE responses). The CE responses were used for analysis purposes as they provide an independent data source (i.e. independent of the CIO responses concerning patterns of IT infrastructure capabilities) and are considered more likely to offer a broader perspective.

Three questions related to marketplace volatility, two to the synergies between business units, one to the role of information and IT needs in planning processes and three to the tracking of long term strategy implementation. These questions drew on concepts of strategic intent (Hamel and Prahalad, 1989, 1994) strategy formation processes elaborated by Hax and Majluf (1988) and Hax (1990) and the iterative nature of IT considerations in planning processes (Venkatraman, 1991; Broadbent and Weill, 1993).

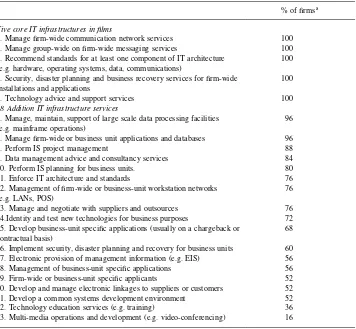

5.4.2. Pattern of IT infrastructure capabilities

identified the firm-wide IT infrastructure services managed by the corporate IS group in each firm. We reviewed these to develop a list of 21 generically expressed IT infrastructure services, eight of which were common to all firms. We used this content analysis as the basis for assessing IT infrastructure services in the subsequent 15 firms, while concurrently checking for further services. Two further IT infrastructure services were identified and we reviewed the data on the initial 11 firms, and in some cases revisited the firms, to check for the existence of these subsequent services. A final list of 23 services was identified and this is included in Table 1. Five of these services were prevalent in all firms that had firm-wide IT infrastructure services. One of the 26 firms did not have any firm-wide IT infrastructure services. A high number of services indicates extensive IT infrastructure capability.

Nature of services: Table 2 presents an allocation by function of each of the services into one of eight service areas. This grouping enabled us to combine like services and look for patterns.

Table 1

Firm-wide IT infrastructure services

% of firmsa

Five core IT infrastructures in films

1. Manage firm-wide communication network services 100

2. Manage group-wide on firm-wide messaging services 100

3. Recommend standards for at least one component of IT architecture (e.g. hardware, operating systems, data, communications)

100

4. Security, disaster planning and business recovery services for firm-wide installations and applications

100

5. Technology advice and support services 100

18 Addition IT infrastructure services

6. Manage, maintain, support of large scale data processing facilities (e.g. mainframe operations)

96

7. Manage firm-wide or business unit applications and databases 96

8. Perform IS project management 88

9. Data management advice and consultancy services 84

10. Perform IS planning for business units. 80

11. Enforce IT architecture and standards 76

12. Management of firm-wide or business-unit workstation networks (e.g. LANs, POS)

76

13. Manage and negotiate with suppliers and outsources 76

14.Identity and test new technologies for business purposes 72

15. Develop business-unit specific applications (usually on a chargeback or contractual basis)

68

16. Implement security, disaster planning and recovery for business units 60

17. Electronic provision of management information (e.g. EIS) 56

18. Management of business-unit specific applications 56

19. Firm-wide or business-unit specific applicants 52

20. Develop and manage electronic linkages to suppliers or customers 52

21. Develop a common systems development environment 52

22. Technology education services (e.g. training) 36

23. Multi-media operations and development (e.g. video-conferencing) 16

Reach and range: During interviews we worked with each firm to identify its reach and range, using the grid shown in Fig. 3, adapted from Keen (1991). For a given Range, there are seven levels of Reach, i.e. seven groups to whom the company can extend that Range capability. The first four levels of Reach are groups internal to the company. The final three levels of reach are groups external to the company.

To facilitate comparison, a formula was developed to convert the plot into a score ranging from 0 to 100 using a simple point counting procedure. Appendix C provides an explanation and details of these calculations. A high score indicated a high level of IT Table 2

Firm-wide IT infrastructure services grouped by functionality

% of firmsa

Applications management

7. Manage firm-wide or business unit applications and databases 96

15. Develop business-unit specific applications (usually on a chargeback or contractual basis)

68

17. Electronic provision of management information (e.g. EIS) 56

18. Management of business-unit specific applications 56

20. Develop and manage electronic linkages to suppliers or customers 82

21. Develop a common systems development environment 52

23. Multi-media operations and development (e.g. video-confer 16

Communication management

1. Manage firm-wide communication network services 100

2. Manage group-wide or firm-wide messaging services 100

12. Management of firm-wide or business-unit workstation networks (e.g. LANs, POS)

76

Data management

9. Data management advice and consultancy services 84

19. Firm-wide or business-unit data management, including standards 52

IT education management

5. Technology advice and support services 100

22. Technology education services (e.g. training) 36

IT R&D

14. Identify and test technologies for business purposes 72

Services management

6. Manage, maintain, support of large scale data processing facilities (e.g. mainframe operations)

96

8. Perform IS project management 88

10. Perform IS planning for business units 80

13. Manage and negotiate with suppliers and outsourcers 76

Security

4. Security, disaster planning and business recovery services for firm-wide installations and applications

100

16. Implement security, disaster planning and recovery for business units 60

Standard management

3. Recommend standards for at least one component of IT architecture (e.g. hardware, operating systems, data, communications)

100

11. Enforce IT architecture and standards 76

infrastructure capability. The firms in the study varied from scores of 17–80 with a mean of 37. The shaded area in Fig. 3 shows an actual reach and range plot for one of the firms in the study, with a score of 35.

6. Findings

We found evidence for six of the seven propositions amongst the 26 firms. In addition, the reach and range was significantly correlated with the number of IT infrastructure services r0:35; p0:04: Propositions were analysed using Pearson Correlation

Coefficients and a summary matrix is presented in Appendix D. The qualitative data was used to help interpret the correlations and further develop the concepts.

6.1. IT infrastructure capability and industry differences

Proposition 1: Firms operating in different industries have different requirements for information, and thus different patterns of IT infrastructure capabilities.

Evidence supporting this proposition was found in the number and nature of IT infra-structure services. Manufacturing firms tended to provide fewer services r20:38;

p0:03than retail or finance firms. The specific areas where those differences occur

to a significant degree are in communications r20:35;p0:04;applications r

20:33;p0:05;IT management r20:27;p0:09;security services r20:26;

p0:09and research and development r20:39;p0:02:Retail firms had more IT

infrastructure services in research and development r0:32;p0:05:Reach and range

was not correlated significantly with whether a firm operated in a particular industry. Thus firms in each industry took a variety of strategies for connectivity and integration—some with low Reach and Range and others with high Reach and Range.

In manufacturing firms such as BP Singapore2and the diversified international company Southcorp Holdings,3IT has traditionally been viewed as providingsupportfor all major functional areas. However, the retail firms reported a 16% average annual increase in their investment in IT over the past five years. Developments in point-of-sale technology, electronic trading, category management at stock keeping unit (SKU) levels, and custo-mer’s expectations for EFTPOS have meant that IT in now critical to competitiveness. In the words of a senior IS manager in a large retailer: ‘We rarely discuss the costs of our systems because of where we are in the evolution of delivering them. Costs are accepted as being high because of the magnitude of the change. We are more concerned with ensuring that the systems we implement are flexible and effective, and that they deliver maximum advantage to the business, and not just in the short term’.4

6.2. IT infrastructure capability and marketplace volatility

Proposition 2: Firms with greater emphasis on the need to change products more quickly will have more extensive IT infrastructure capabilities.

Support for this proposition was found by analysing the firm’s total number of IT infrastructure services and two IT infrastructure service areas in particular. Firms which needed to change products more quickly provided more IT infrastructure services r0:29;p0:08and provided a higher number of services in the areas of applications r0:27;p0:09and data management r0:45;p0:01.

The Development Bank of Singapore (DBS) is the largest bank in Singapore with most of its international offices spanning the Asia-Pacific.5DBS has a reputation for innovation in consumer banking and is consistently the first local bank to introduce new financial products and services. DBS has extensive IT infrastructure capabilities that enable it to continue to compete with product leadership. Staff and technology are seen as the pillars of DBS’ success. In the words of a senior business manager: ‘If our approach had been to determine how much we could save, we would not have invested in technology in the way

2Soh, C. and Neo, B.S. Case vignette of BP Singapore: Information Technology Infrastructure Study.

Melbourne Business School, The University of Melbourne, 1995.

3O’Brien, T. and Broadbent, M.Case vignette of Southcorp Holdings: Information Technology Infrastructure

Study.Melbourne Business School, The University of Melbourne, 1995.

4Butler, C. and Weill, P. Case vignette of Woolworths: Information Technology Infrastructure Study.

Melbourne Business School, The University of Melbourne, 1995.

5Neo, B.S. and Soh, C. Case vignette of the Development Bank of Singapore: Information Technology

we did. We view technology as strategic investments—to give us a competitive edge…. We do not just follow what other banks are doing’. A technology planning group conti-nually tracks and evaluates new technologies that would provide a basis for new product development.

Proposition 3: Firms which tend to make resource decisions based on current needs will have less extensive IT infrastructure capabilities.

Support for this proposition was evident in only one IT infrastructure service area. Firms which tended to base resource decisions on current needs provided fewer IT education infrastructure services r20:41; p0:02: From our interviews, non-IT managers

universally bemoaned the lack of training and education. Empirically this problem was worse in firms that made investment decisions based on current needs. Interestingly, IT managers complained that when IT education was organised, business managers often didn’t come.

Proposition 4: Firms with greater emphasis on flexibility to meet changing needs of their marketplace will have more extensive IT infrastructure capabilities.

No support was found for this proposition. Greater emphasis on flexibility to meet changing needs was not correlated significantly with IT infrastructure capability in terms of either the number of services or reach and range, nor was such an emphasis correlated significantly with any of the IT infrastructure service areas. This could be because flexibility requires different solutions in different contexts.

Greater flexibility to respond quickly might mean limited or no firm-wide infrastructure where there is little synergy between business units. For example, the manufacturer Ralston Purina has several large business units with products as diverse as pet foods and dry cell battery products.6These businesses compete in quite different markets and the lack of firm-wide infrastructure can provide greater flexibility for each business unit. On the contrary, the Commonwealth Bank of Australia has extensive IT infrastructure to provide flexibility and cope with higher levels of uncertainty and changes in strategic direction.7The infrastructure provides the capability to meet the bank’s strategies that all information to service any customer be available at the point of contact to improve service, enhance customer relationships and minimise risk. The extent of these services reflects the two-way flow of influence in the bank between business and information technology strategies. As phrased by a senior manager: ‘The bank and information technology are inseparable’.

The construct of flexibility generated by IT infrastructure needs significantly more refinement.

6Lentz, C. and Ross, J. Case vignette of Ralston Purina: Information Technology Infrastructure Study.

Melbourne Business School, The University of Melbourne, 1995.

7Dery, K. and Weill, P. Case Vignette of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia: Information Technology

6.3. IT infrastructure capability and business unit synergies

Proposition 5: Firms with greater emphasis on identifying synergies between business units will have more extensive IT infrastructure capabilities.

Firms which seek cooperation and synergies between business units to achieve strategic intent have more extensive IT infrastructure capability in both the number of services provided r0:52;p,0:01and the reach and range r0:31;p0:07:Extensive

capability in six of the eight information technology infrastructure service groups correlate significantly with the objective to achieve cooperation and synergy between business units. The six groups are: standards r0:61; p,0:01; IT management r0:55;

p,0:01; applications r0:41; p0:02; communications r0:40; p0:02;

data management r0:34; p0:04 and security r0:29; p0:08: Firms which

document how business units contribute to the achievement of firm strategic intent have a greater number of services in communications r0:39;p0:03and IT management r0:32;p0:06:Hence, the identification and achievement of business unit synergies

is a primary driver for the development of IT infrastructure capability.

For the international manufacturer of health care products, Johnson & Johnson, the desire to leverage its strength with its changing customer base resulted in a business driver to ‘develop partnerships with customers on a worldwide basis’.8This meant understanding the synergies between business units and identifying large customers who were dealing separately with different autonomous business units. Johnson & Johnson recognised that this changed the amount and kinds of information and IT applications that had to be shared across business units. The result was more extensive infrastructure services, including the aggregation of data and the introduction of common application systems to provide the foundation for delivering consolidated customer profiles.

6.4. IT infrastructure capability and strategy formation processes

Proposition 6: Firms with greater integration of information and IT needs as part of the firm’s overall planning processes will have more extensive IT infrastructure capabilities.

There was a very strong positive association between the integration of information and IT in overall planning processes and the pattern of IT infrastructure capabilities. Both the number of IT infrastructure services r0:64;p,0:01and reach and range r0:43;

p0:01were correlated to the integration of information and IT in the business planning

process. A higher level of integration affected every infrastructure service group with the most positive associations being IT management r0:70; p,0:01; applications r0:58; p,0:01; communications r0:57; p,0:01 and standards r0:40;

p0:02:Thus, amongst this group of firms, a high level of IT infrastructure capability

8Ross, J.Johnson & Johnson: Building an Infrastructure to Support Global Operations.CISR Working paper

no. 283, Center for Information Systems Research, Sloan School of Management, MIT, September 1995; Lentz,

C., J. Ross and J. Henderson.Case Vignette of Johnson and Johnson Company: Information Technology

was associated with a high level of integration of information and IT needs in planning processes. This strong relationship could be because such an infrastructure capability is important in order for the firms to compete. Alternatively, it could be because deeper consideration of information and IT needs generally results in leading to more capability and higher expectations.

Competitive pressures forced the Royal Automobile Club of Victoria (RACV), a membership based provider of insurance, roadside vehicle services, travel and other services in Australia, to rethink the role of IT, particularly firm-wide infrastructure invest-ments.9When an equivalent organisation in a neighbouring state extended its base into RACV’s geographic area, RACV engaged in extensive planning, resulting in a stronger focus on customer needs, membership acquisition and innovative products and services. The planning processes and strategies raised the importance of cross-selling and surfaced the urgency of sharing customer databases and transaction processing systems across businesses leading to more firm-wide IT infrastructure capability.

Proposition 7: Firms with greater emphasis on tracking the success of implementation of strategic intent will have more extensive IT infrastructure capabilities. The indicators of the extent of a firm’s emphasis are: (i) the level of reporting progress against strategic intent; (ii) whether achievements are actively measured; and (iii) whether those responsible are identified.

More extensive IT infrastructure capability is evident (in both the number of services and reach and range) where there is a higher level of reporting progress in achieving the strategic intent of the firm (services: r0:42; p0:02; reach and range: r0:34;

p0:05; where such achievements are measured (services: r0:45; p0:01 and

where those responsible are identified (services: r0:44;p0:01;reach and range:

r0:35;p0:04:Thus firms with a higher level of tracking the success of strategy

implementation have more extensive IT infrastructure capabilities. Service areas which correlated most positively with these strategy formation process variables were communications, applications, and IT management.

The multinational insurance firm, Sun Life of Canada, has a strong culture of articu-lating strategic directions, then tracking, reporting and measuring strategy implementation at multiple levels.10Sun Life has an acknowledge focus on sharing knowledge, fostering innovation and careful monitoring through regular reviews identifying and communi-cating ‘lessons learned’. The firm has a series of interlocking business and IT committees which develop and monitor strategic business and technology developments and assist in leveraging Sun Life’s IT investments. Sun Life offers both basic and strategically focused IT infrastructure services including the operation, maintenance and support of mainframe computing facilities, data administration, planning and support of voice and data commu-nications, universal file access, a series of shared applications, electronic mail and voice mail, and video conferencing. While business and information technologies influence each

9Dery, K. and Weill, P.Case Vignette of RACV: Information Technology Infrastructure Study. Melbourne

Business School, The University of Melbourne, 1995.

10Lentz, C. and Henderson, J. Case Vignette of Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada: Information

other, infrastructure investments must meet defined and measurable business needs and are monitored for the value they provide.

7. Towards a model of infrastructure capability

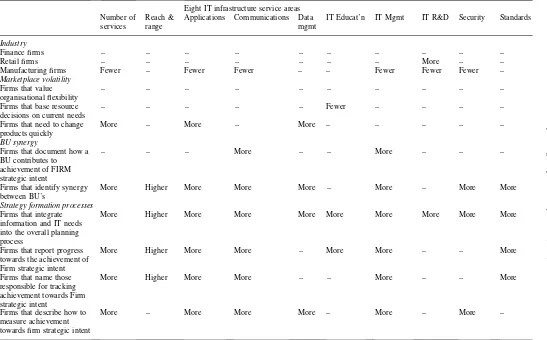

The links identified statistically between firm context and the pattern of IT infrastructure capability in the firms are summarised in Table 3. A strong association was evident between higher levels of IT infrastructure capability and firms which: value business unit synergies, integrate information and technology needs into overall firm-wide planning processes and had specific practices in place aimed at achieving firm-wide strategic intent. The link between firm context and IT infrastructure capability is clearly more complex than that in the preliminary model (Fig. 2). The revised model, drawing on our research, is presented in Fig. 4 showing the thin base of the five core services and the extensive capability provided by all 23 services. The revised model depicts the increasing impor-tance of IT infrastructure capability to firms with particular characteristics. There were industry differences with extensive infrastructure capability of less importance to the less information intense manufacturing firms. Firms with a focus on identifying synergies between business units, integrating information and IT needs as part of planning processes and tracking the implementation of strategy have more extensive IT infrastructure capability in the form of both more shared services and greater reach and range.

While all firms had the five core services, the pattern of the further 18 services varied considerably. IT infrastructure services in the areas of communications, applications, IT management, and standards management were consistently associated with a focus on identifying business unit synergies, the integration of IT planning and well developed planning processes. While communications provide a basic technical capacity, the other three focus more on the application of human expertise and intellect in light of the firm’s long term investments. This pattern is consistent with recent findings on the significance of IT managerial skills and knowledge in achieving sustained competitive advantage (Mata et al., 1995) and appropriate business and technology strategy integration (Boynton and Zmud, 1987).

8. The changing nature of it infrastructure capability

In this section we reflect on our operationalisation of the construct of IT infrastructure contrasting our theoretical model (Figs. 1 and 2) with the empirical evidence. Over the course of the study we noticed a gradual increase of the use of the words and concepts of infrastructure and shared services in the management lexicon. The trend of greater adoption of both standard and shared applications is evident in many industries, though the underlying rationales can differ.

M.

Firm context and IT infrastructure services and reach and range (all table entries represent statistically significant relationshipsp#0:10)

Eight IT infrastructure service areas

IT Educat’n IT Mgmt IT R&D Security Standards

Industry

Finance firms – – – – – – – – – –

Retail firms – – – – – – – More – –

Manufacturing firms Fewer – Fewer Fewer – – Fewer Fewer Fewer –

Marketplace volatility

More Higher More More More – More – More More

Strategy formation processes

Firms that integrate information and IT needs into the overall planning process

More Higher More More More More More More More More

Firms that report progress towards the achievement of Firm strategic intent

More Higher More More – More More – – More

SAP as their standard. In these firms the provision of the ERP modules (e.g. finance), and the client server infrastructure and expertise required, has become shared, standard and centrally coordinated and thus part of the IT infrastructure.11

In the banking industry, groups such as Citibank Asia have centralised and standardised back room processing across five Asian countries. The driver for this change is ‘Citibank-ing’—‘combining relationship banking with technology that enables the customer to exercise greater control over his or her funds’.12The technology enables the Citibanking vision in two major ways: first, with a one-stop paperless account opening, instant account availability, instant card and check issuance; second, with a customer relationship database that supports cross-product relationships, creation of customised products, and relationship pricing that more closely matches the value to the customer. The Citicard is the key to Citibanking services such as checking, money market, and bankcard accounts. In addition, the centralisation of card processing operations for Asian countries reduced costs per card to less than one-third the previous costs and enabled a 23-fold increase in productivity.

For banks such as Citibank the driver to identify shared and standard applications has been a combination of strategic intent (i.e. Citibanking) and cost saving via sharing and centralisation. Citibank’s IT infrastructure includes both shared IT services (e.g. centra-lised large-scale processing and customer relationship database) and shared applications (e.g. account opening and check issuance).

In the firms studied we estimate less than five percent of the annual IT investment was in shared and standard applications whilst 52% (i.e. 57 less 5%) was firm-wide IT

Fig. 4. Revised model: firm context and IT infrastructure capability.

11Very recently we have observed a falling off in demand for ERPs, perhaps caused by the cost and complexity

of implementing these all encompassing packages.

12Neo, B.S. and Soh, C. Case Vignette of Citibank—Asia Pacific: Information Technology Infrastructure

infrastructure. However, from the future plans identified by the 26 CIOs the investment in shared and standard applications will grow rapidly. The shared and standard applications may be provided by implementing ERPs, “best of breed” modules selected from a number of vendors or custom developed software. Historically these applications have been general management applications such as general ledger, human resources management and budgeting. However, now we are observing strategic positions driving the adoption of shared and standard applications for key processes (e.g. order processing).

This trend is reflected in a revised model of IT infrastructure capability (Fig. 5) which includes both IT services and shared and standard IT applications as infrastructure. The definition of IT infrastructure must be altered slightly to be:

the base foundation of budgeted-for IT capability (both technical and human), shared throughout the firm in the form of reliable services and shared applications, usually centrally coordinated.

The services and shared applications are treated separately in the revised model as they have different characteristics and thus need to be managed in different ways (Grossman and Packer, 1989).13

The IT infrastructure services must be defined and provided in a way that allows them to be used by multiple applications including the infrastructure applications. The objective is to enable economies, reuse, synergies and flexibility. The nominal owner of these shared services thus must have firm-wide responsibility (e.g. the CIO). An application such as

13In our ongoing work (Weill and Broadbent 1998) we have identified two further services which have emerged

since the research was completed. These are: (i) provide firm-wide intranet capability (e.g. information access, multiple system access); (ii) provide firm-wide electronic support for groups (e.g. Lotus Notes).

order processing may use as many as five or six services which all must be in place and accessible. To achieve this level of modularity and integration requires careful specifi-cation of the IT architecture (Keen, 1995, p. 45) and particularly the specifispecifi-cation of the interfaces to infrastructure services new applications will need to comply with.

IT infrastructure applications are shared and standard applications applied across the firm and are often the result of strategic objectives. Unlike IT infrastructure services, the scope of the application is for a particular business process. We observed examples where the “notional owner” of the infrastructure applications was a manager of the particular business process (e.g. buying in retailing) or, in some cases, the CIO.

Interestingly most of the CEs were very comfortable with notion of infrastructure be it information technology, human resources or buildings. This was equally true for the CIOs who had a firm-wide responsibility and were constantly facing the decisions of what should and what should not be infrastructure and thus shared and standard. However IT managers in BUs were often less comfortable with the concept or the practicalities of operation. The BU managers were concerned about “lack of control”, being “forced to comply by the corporate IT group” and required to adopt applications which were a good “average fit across the firm” but not optimal for their BU.

In general, most BU managers (both general and IT) were more comfortable with IT infrastructures at the business unit level. The BU managers argued they could tailor the infrastructures to their needs and had far more control on the quality and cost of the services. Many BU managers grudgingly acknowledged the need for firm wide IT infra-structures but were quick to point out the problems they had experienced. The question of at what level (i.e. firm-wide or BU-wide) a particular IT infrastructure service (i.e. client database) should be provided was a source of tension in many firms. The benefits of firm-wide provision were cited as economies of scale, synergies and cross-selling, while the BU IT managers argued for the increased levels of customisation and control afforded by local provision. Some firms never formally resolved this dilemma with each new initiative opening the debate afresh. Other firms resolved this dilemma with a business maxim (Broadbent and Weill, 1997) from corporate providing direction and credibility for firm-wide shared IT infrastructure services.

9. Limitations

This empirical case research study was limited to 26 firms in three industries. The firms were carefully selected to meet certain criteria, namely: as a group they had to provide an international perspective; and each firm had to be an industry leader by market share within its region. However, the firms in this study do not constitute a random sample, nor are they representative of the total population of firms in any of the three industries.

10. Conclusions

The patterns of infrastructure capability amongst the firms in this study indicate an iterative link between the efforts to garner synergy from business units and the considera-tion given to investment in IT infrastructure services and extending reach and range. The identification and achievement of business unit synergies seem to be primary drivers for firm-wide IT infrastructure capability and is seen as an attempt to generate ‘system value’ (Viscio and Pasternack, 1996, p. 13) which is more than the sum of each of the separate business units.

Higher levels of IT infrastructure capability were associated with greater integration of information and IT needs in strategy formation processes. This relationship could indicate that a deeper consideration of the IT implications for strategic choices leads to more extensive investment in IT infrastructure services. A question for further investigation is whether different strategic intents lead to deeper consideration of IT implications and thus more extensive IT infrastructure. Alternatively it may be that firms which better integrate IT needs with business strategy tend to have more extensive IT infrastructure regardless of strategy.

Firms which tracked long term strategy implementation had greater IT infrastructure capability. The implication here could be that more careful post implementation assess-ment focuses on how strategic choices can be impleassess-mented, and thus greater realisation of the role of IT infrastructure capability in their achievement.

Another trend we observed was the increasing use of outsourcing for IT infra-structure provision. The firms studied were modest users of outsourcing averaging 9.7% p.a. of their total IT investment. However, their use of outsourcing was also growing at 8.2% p.a. We demonstrated statistically that the firms, which outsourced more, had lower IT costs and were also more likely to compete predominantly on price. Firms which outsourced more also had longer time to markets for new products than their competitors (Weill and Broadbent, 1998, p. 64). Although not conclu-sive these findings provide evidence that outsourcing IT infrastructure impacts both cost and strategic flexibility.

Future work can focus on at least four areas: further analysis of each IT infrastructure service through the development of depth indicators to measure the level at which each service is offered; application of the notion of IT infrastructure services to other levels in the firm, such as within business units; analysis of other industries to provide a rich source of comparison; the impact of outsourcing IT infrastructure on flexibility and deeper examination of the management processes by which firms link strategy and IT infrastructure formation processes.

greater IT infrastructure capability will need to provide more IT infrastructure services as well as more extensive reach and range carefully tailored to meet the particular strategic needs.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the significant contribution of the co-author of the ICIS Paper Tim O’Brien.

Appendix A. Participating firms by region

Australia ANZ Banking Group BP Australia Brash Holdings Caltex

Carlton and United Breweries (Fosters Brewing Group) Coles Myer (Target, K-Mart, Dept Stores)

Commonwealth Bank Australia ICI Australia

Johnson & Johnson (Asia & Pacific) Metway Bank

Monier/PGH

National Australia Bank RACV

Southcorp Woolworths North America Johnson & Johnson

Ralston Purina Sunlife of Canada Unum

Europe S.G. Warburg

Asia BP Singapore

Citibank Asia Pacific

Development Bank of Singapore Development and Commercial Bank MayBank

Times Publishing

Appendix B. Firm context questions

(IT) investments in your firm. To be consistent with other firms we first provide some definitions:

The term FIRM embraces the Corporate Headquarters and all BUSINESS UNITS of the organisation.

A BUSINESS UNIT refers to the way your FIRM subdivides the organisation for management accountability. Typically this will involve the combination of:

a distinct set of products or services;

competing with a well-defined set of competitors; with independent management and accountability.

B.1. Strategic intent

STRATEGIC INTENT refers to a FIRM’s term target(s) and embraces the long-term vision for the FIRM as a whole. It is usually stable over time.

Some examples of statements of STRATEGIC INTENT are:

to become the preferred bank for Australia’s best performing companies in the 1990s as they move increasingly to operate in global markets;

to operate several independent consumer products business units under the corporate umbrella which in any year provide an overall return on assets (ROA) of at least 7.5%; to be the insurance company, which provides the best financial planning to its clients, resulting in clients having more than one of our products;

to be the best performing oil company in our region by maximising profitability in our two core businesses of Exploration and Production, Refining and Marketing.

Could you please describe the STRATEGIC INTENT of your FIRM as a whole.

To what extent do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements in relation to the FIRM as a whole? Please circle the number that best describes your view ranging from: 1 (Strongly Disagree), 3 (Neither Agree nor Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

B.2. Marketplace volatility (** significance level p,0.01)

Strongly in response to changes in the marketplace

B.3. Business unit synergies (** significance level p,0.01)

B.4. Strategy formation processes (*significance level p,0.05; ** significance level

Appendix C. Calculating reach and range

In the following example, the Reach and Range score is calculated for company Company X. Fig. A1 shows a plot Company X’s reach and range.

When calculating the reach and range score, each level of Range (i.e. each service) should be considered in isolation. For a given Range, there are seven levels of Reach, i.e. seven groups to whom the company can extend that Range capability. The first four levels of Reach are groupsinternalto the company. The final three levels of reach are groups

externalto the company.

As a company extends its Reach for a particular Range capability, it accumulates “points”. In providing the most basic Range capability, “Sending Message”, a company accumulates one point for each of the internal groups to whom it can send messages, and two points for each of the external groups to whom it can send messages.

Hence, each cell in the Reach and Range grid represents a value that may contribute to the Reach and Range score. The cell values are shown in Fig. A2. Simply add the points for each level of Reach and Range provided. If a company was able to provide complete Reach and Range, it would score the maximum 100 points.

As it is more difficult to extend a service to external groups than to internal groups due to such issues as security, standardisation and connectivity, an external connection is weighted twice an internal connection.

As it is more difficult to extend Reach as the Range capability moves from left to right in Fig. A1 due to dealing with such issues as incompatible systems, politics, security and data incompatibilities, the four levels of Range are weighted 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively.

Company X scores a total of 43 points for its ability to extend its Reach for the four levels of Range.

To put this score in context, the mean Reach and Range scores for each industry covered by the study is shown below. Of the firms covered by the study, the highest Reach and Range score was 80, and the lowest 17.

Finance Manufacturing Retail All

M.

Appendix D. Pearson correlation coefficients (^ significance level #0.10; * significance level #0.05; ** significance level #0.01)

Finance (dummy) 0.20 0.22 0.25 0.19 0.14 0.10 0.04 0.06 0.07 0.12

Retail (dummy) 0.21 20.10 0.11 0.16 0.06 0.10 20.10 0.25 0.22 0.33^

Manufacturing (dummy) 20.38* 20.14 20.35* 20.33* 20.20 20.19 0.04 20.27^ 20.26^ 20.39*

Marketplace volatility

Value organisational flexibility 0.10 20.07 20.18 0.23 0.20 20.11 0.03 20.01 0.04 0.07

Base resource decisions on current needs

20.14 20.07 20.06 20.13 20.02 20.10 20.41* 20.10 20.06 0.25

Need to change products quickly 0.29^ 20.06 0.15 0.27^ 0.45** 0.06 20.12 0.13 0.14 0.21

BU synergy

0.52** 0.31^ 0.40* 0.41* 0.34* 0.61** 0.23 0.55** 0.29^ 0.00

Strategy formation processes

IT needs are an integral part of the firm’s planning process

0.64** 0.37* 0.57** 0.58** 0.31^ 0.40* 0.36* 0.70** 0.36* 0.34*

Report progress towards achieving strategic intent

0.42* 0.34* 0.57** 0.33* 0.20 0.27^ 0.35* 0.46** 0.20 20.05

Name those responsible for tracking strategic intent

0.44* 0.35* 0.44* 0.39* 0.22 0.32^ 0.18 0.44* 0.19 0.08

Measurement of achievement towards strategic intent

References

Barney, J., 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 17 (1), 99–120.

Benbasat, I., Nault, B.R., 1990. An evaluation of empirical research in managerial support systems. Decision Support Sciences 6 (3), 203–226.

Boynton, A.C., Zmud, R., 1987. Information technology planning in the 1990s: directions for practice and research. MIS Quarterly 11 (1), 59–71.

Boynton, A.C., Victor, B., Pine, J., 1993. New competitive strategies: challenges to organizations and information technology. IBM Systems Journal 32 (1), 40–64.

Bradley, S.P., Hausman, J.A., Nolan, R.L., 1993. Globalization and technology. In: Bradley, S.P., Hausman, J.A., Nolan, R.L. (Eds.). Globalization, Technology, and Competition: the Fusion of Computers and Telecommu-nications in the 1990s, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, pp. 3–32.

Brancheau, J.C., Janz, B.D., Wetherbe, J.C., 1996. Key issues in information systems management: 1994–95 SIM Delphi results. MIS Quarterly.

Broadbent, M., Weill, P., 1993. Improving business and information strategy alignment: learning from the banking industry. IBM Systems Journal 32 (1), 162–179.

Broadbent, M., Weill, P., 1997. Management by maxim: how business and IT managers can create IT infra-structures. Sloan Management Review 38 (3), 77–92.

Broadbent, M., Butler, C., Hansell, A., 1994. Business and technology agenda for information systems executives. International Journal of Information Management 14 (6), 411–426.

Caron, J.R., Jarvenpaa, S.L., Stoddard, D., 1994. Business reengineering at CIGNA corporation experiences and lessons from the first five years. MIS Quarterly 18 (3), 233–250.

Cash, J.I., McFarlan, F.W., McKenney, J.L., Applegate, L., 1992. Corporate Information Systems Management: Text and Cases, 3. Irwin, Boston.

Clemons, E., Row, M., Venkateswaran, R., 1989. The Bell Canada CRISP project: a case study of migration of information systems infrastructure for strategic positioning. Office: Technology and People 5 (4), 299–315. CSC Index, 1992. Building a New Information Infrastructure, CSC Index, November.

CSC Index, 1993. Building the new Information Infrastructure. (Final Report No. 91), CSC Index, Boston, MA. Darnton, G., Giacolette, S., 1992. Information and IT Infrastructures, Information in the Enterprise: It’s More

Than TechnologyDigital Press, Salem, MA, pp. 273–294.

Davenport, R., Linder, J., 1994. Information management infrastructure: the new competitive weapon. Proceed-ings of the 27th Annual Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences, IEEE, 885–899.

Davidow, W.H., Malone, M.S., 1992. The Virtual Corporation, New York, Harper Collins.

Davidson, W.H., Movizzo, J.A., 1996. Managing the transformation process: planning for a perilous journey. In: Luftman, J. (Ed.). Strategic Alignment: Practical Perspectives, Oxford University Press, New York. Dixon, J.R., Arnold, P., Heineke, J., Kim, J.S., Mulligan, P., 1994. Business process reengineering: improving in

new strategic directions. Californian Management Review 36 (4), 93–108.

Duncan, N.B., 1995. Capturing flexibility of information technology infrastructure: a study of resource charac-teristics and their measure. Journal of Management Information Systems 12 (2), 37–57.

Earl, M.J., Kuan, B., 1994. How new is business process redesign? European Management Journal 12 (1), 20–30. Eisenhardt, K.M., 1989. Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review 14 (4),

532–550.

Furey, T.R., Diorio, S.G., 1994. Making reengineering strategic. Planning Review 22 (2), 7–11 see also p. 43. Grossman, R.B., Packer, M.B., 1989. Betting the business: strategic programs to rebuild core information

systems. Office: Technology and People 5 (4), 235–243.

Grover, T., Teng, J., Fiedler, K., 1993. Information technology enabled business process redesign: an integrated planning framework. OMEGA, International Journal of Management Science 21 (4), 433–447.

Hamel, G., Prahalad, C.K., 1989. Strategic Intent. Harvard Business Review 67 (3), 63–76.

Hamel, G., Prahalad, C.K., 1994. Competing for the Future: Breakthrough Strategies for Seizing Control of Your Industry and Creating the Markets of Tomorrow, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Hax, A.C., Majluf, N.S., 1988. The concept of strategy and the strategy formation process. Interfaces 18 (3), 99–109.

Henderson, J.C., Venkatraman, N., 1992. Strategic alignment: a model for organizational transformation through information technology. In: Kochan, T.A., Useem, M. (Eds.). Transforming Organizations, Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 97–116.

Kambil, A., Henderson, J.C., Mohsenzadeh, H., 1993. Strategic management of information technology invest-ments: an options perspective. In: Banker, R., Kauffman, R., Mahmood, M.A. (Eds.). Strategic Information Technology Management: Perspectives on Organizational Growth and Competitive Advantage, Idea Group Publishing, Middleton, PA.

Kaplan, B., Duchon, D., 1988. Combining qualitative and quantitative methods in information systems research: a case study. MIS Quarterly December, 571–586.

Kay, J., 1993. Foundations of Corporate Success: How Business Strategies Add Value, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Keen, P.G.W., 1991. Shaping the Future: Business Design through Information Technology, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Keen, P.G.W., 1995. Every Manager’s Guide to Information Technology, 2. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Keen, P.G.W., Cummins, J.M., 1994. Networks in Action: Business Choices & Telecommunications Decisions, Wadsworth, Belmont, CA.

Markides, C., 1999. A dynamic view of strategy. Sloan Management Review Spring, 55–64.

Mata, F.J., Fuerst, W.L., Barner, J.G., 1995. Information technology and sustained competitive advantage: a resource-based analysis. MIS Quarterly 19 (4), 487–505.

McKay, D.T., Brockway, D.W., 1989. Building I/T infrastructure for the 1990s. Stage by Stage (Nolan Norton and Company) 9 (3), 1–11.

McKenney, J.L., 1995. Waves of Change: Business Evolution through Information Technology, Harvard Busi-ness School, Boston, MA.

Miller, D.B., Clemons, E.K., Row, M.C., 1993. Information technology and the global virtual corporation. In: Bradley, S.P., Hausman, J.A., Nolan, R.L. (Eds.). Globalization, Technology, and Competition: The Fusion of Computers and Telecommunications in the 1990s, Harvard Business School, Boston, MA, pp. 283–308. Mintzberg, H., Quinn, J., 1991. The Strategy Process, Prentice-Hall, New York.

Neo, B.S., 1991. Information technology and global competition: a framework for analysis. Information and Management 20 (3), 151–160.

Parker, M.M., Benson, R.J., 1988. Information Economics: Linking Business Performance to Information Technology, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

PE International, 1995. Justifying Infrastructure Investment. IT Management Programme Report. Egham, UK: Centre for Management Research, PE International. May, 1995.

Pearce, J.A., Robbins, D.K., Robinson, R.B., 1987. The impact of grand strategy and planning formality on financial performance. Strategic Management Journal 8 (2), 125–134.

Pervan, G.P., 1994. Information systems management: an Australian view of the key issues. Australia Journal of Information Systems 1 (2), 32–44.

Porter, M.E., 1996. What is Strategy? Harvard Business Review November/December, 96 608.

Porter, M.E., Millar, V.E., 1985. How information gives you a competitive advantage. Harvard Business Review July/August, 149–160.

Powell, T.C., Dent-Micallef, A., 1997. Information technology as competitive advantage: the role of human, business and technology resources. Strategic Management Journal 18 (5), 375–405.

Quinn, J.B., 1992. Intelligent Enterprise: A Knowledge and Service Based Paradigm for Industry, The Free Press, New York.

Rayport, J.F., Sviokla, J.J., 1995. Exploiting the virtual value chain. Harvard Business Review 73 (6), 75–85. Segev, E., 1988. A framework for grounded theory of corporate policy. Interfaces 18 (5), 42–54.

Turnbull, P.D., 1991. Effective investments in information infrastructures. Information and Software Technology 33 (3), 191–199.

Viscio, A.J., Pasternack, B.A., 1996. Toward a new business model. Strategy and Business Second Quarter (3), 8–15.

Wastell, D.G., White, P., Kawalek, P., 1994. A methodology for business process redesign: experiences and issues. Journal of Strategic Information Systems 3 (1), 23–40.

Weill, P., 1993. The role and value of information technology infrastructure: some empirical observations. In: Banker, R., Kauffman, R., Mahmood, M.A. (Eds.). Strategic Information Technology Management: Perspec-tives on Organizational Growth and Competitive Advantage, Idea Group Publishing, Middleton, PA. Weill, P., Broadbent, M., 1994. Infrastructure goes industry specific. MIS July, 35–39.

Weill, P., Broadbent, M., 1998. Leveraging the New Infrastructure: How Market Leaders Capitalize on Informa-tion Technology, Harvard Business School, Boston, MA.

Weill, P., Broadbent, M., Butler, C., Soh, C., 1995. Firm-wide Information Technology Infrastructure investment and services, Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Information Systems, Amsterdam, December.