and Job Satisfaction of Apparel Product

Developers and Traditional Retail Buyers

Young-Eun Choi

IOWASTATEUNIVERSITY ANDSAMSUNG

LuAnn Ricketts Gaskill

IOWASTATEUNIVERSITYJob-related information and analysis are fundamental parts for both tion, and increased cooperation in performing their functions compared with those engaged in traditional retail buying. workers and organizations to increase productivity and job satisfaction

that are extensively related to the business organization’s performance. This study presents an analysis of specific job characteristics, job contents,

The Literature

and behaviors in the two diverse merchandising line development process

of traditional retail buying and apparel product development.J BUSN RES

Job Characteristics and Content

2000. 49.15–34. 2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved

In today’s rapidly changing work environment, job crisis issues have emerged as reflected in job absenteeism, higher turnover, decreased labor productivity, and declining economic growth (Ford, 1969; Davis and Tylor, 1972; Organ and Hamner,

S

elf-administered questionnaires were mailed to a random1982). As a result, more and more organizations are turning sample of 249 traditional retail buyers and 250 apparel

to the redesign of work to increase productivity, job satisfac-product developers selected from directories listing

thou-tion, and enhance the business organization’s performance sands of retail executives nationwide. ANOVA, MANOVA,

(Hackman and Oldham, 1975; Hackman, Oldham, Janson, and and Chi-Square statistics were performed to test five research

Purdy, 1975; McCormick, 1979; Bowditch and Buono, 1994). hypotheses developed to determine if differences exist in job

According to McCormick (1979), work redesign requires content, worker’s perception, job satisfaction, interaction with

the development of data pertaining to job characteristics. other departments, and activities related to line development

Commonly used descriptors for characterizing jobs describe between traditional retail buyers and retail product

develop-job content, with particular emphasis on the work activities ers. Significant differences were found between apparel

prod-and related aspects of the work environment. uct developers and traditional retail buyers. Compared with

In a job characteristics model (JCM), Hackman and Old-traditional retail buyers, apparel product developers were

ham (1975, 1976) detailed the hypothesized effects of specific more likely to employ the mental processes of analyzing

quan-job scope characteristics on intervening psychological states titative information, planning/scheduling, problem solving/

and subsequent work attitudes and behaviors. The researchers analyzing, and mathematics. Traditional retail buyers,

how-proposed that the actual duties and responsibilities which ever, who were found to carry more physical exertion-oriented

comprise a job have the capacity to motivate certain individu-tasks, scored higher on their overall job satisfaction,

auton-als (Landy, 1985). omy, and task identity in performing their job. Significant

The JCM identifies five basic job characteristics or core job differences also were found in activities related to line

develop-dimensions that should be considered when attempting to ment between the two groups.

redesign work (i.e., skill variety, task identity, task signifi-The study suggests that retailers who expanded their role

cance, autonomy, and feedback). These core dimensions are into product development require higher skills, more

educa-argued to influence critical psychological states of employees. Critical psychological states are linked to such outcomes and Address correspondence to LuAnn R. Gaskill, 1056 LeBaron Hall, Iowa State

University, Ames, IA 50011. work behaviors as high motivation, high quality work perfor-Journal of Business Research 49, 15–34 (2000)

2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved ISSN 0148-2963/00/$–see front matter

mance, high levels of job satisfaction, low absenteeism, and company-specific factors. Particularly, Sheth’s model explains fundamental organizational buying behaviors related to as-turnover (Ford, 1969; Wanous, 1974; Hackman and Oldham,

1975; Hackman, Oldham, Janson, and Purdy, 1975). pects of the decision-making process.

Sheth’s merchandising model has been found to be applica-The job characteristics model can be applied as a diagnostic

tool through Hackman and Oldham’s (Hackman and Oldham, ble in assessing a retail buyers’ purchasing process (Francis and Brown, 1985; Wagner, Ettenson, and Parish, 1989). Par-1975) job diagnostic survey (JDS). The JDS is a

self-adminis-tered questionnaire that measures the extent to which a partic- ticularly, this model has been used as the theoretical basis from which to study traditional retail buyers by identifying ular job fulfills the dimensions specified by the framework

selected components and analyzing them in relation to retail from the perception of the workers themselves. It is also the

buying behavior (Ettenson and Wagner, 1986; Anthony and most commonly used instrument to assess perceived task

Jolly, 1991; Shim and Kotsiopulos, 1991; Kline and Wagner, design (Dunham, Aldag, and Brief, 1977).

1994). Job information and analysis is a requirement in system and

One of the most acute problems of today’s retailers is an equipment design, workplace layout, performance assessment

“identity crisis.” Many stores are virtually identical in terms of (Meister, 1985), training, personnel selection, job design, job

merchandise carried and presentation (Bergman, 1985; Moin, evaluation, recruiting, management-union relationships, and

1986; Jernigan and Easterling, 1990; Clodfelter, 1993; Fickes, population analysis (McCormick, 1979). It describes

impor-1993; Morgenson, impor-1993; Wilensky, 1994). Consumers have tant aspect of a job that distinguish it from other types of jobs

become bored with the similarities and lack of product differ-(Landy, 1985) and analyzes the basic nature and content of

entiation in retailing. Consumers in the 1990s are value-ori-the work process.

ented shoppers, looking for product quality and value (Why McCormick and Tiffin (1974) identified the importance

Designer Labels are Fading, 1983; Epstein, 1992; Germeroth, of a worker-oriented approach in the study of job analysis

1992a, 1992b; Soderquist, 1993). They do not care where (McCormick and Tiffin, 1974; Muchinsky, 1983).

Worker-they shop, as long as Worker-they are assured of good quality and oriented elements are generalized descriptions of human

be-value. They are an educated and sophisticated population, havior patterns useful in structuring training programs and

making their own decisions about product quality (Barmash, providing performance appraisal feedback to employees.

1986; Underwood, 1992). A well-used structured questionnaire describing generic

Contemporary retailers are recognizing the need to become types of worker-oriented behaviors involved in work is the

increasingly competitive and creative in order to satisfy the position analysis questionnaire (PAQ) (McCormick, Jeanneret,

changed needs of consumers. To survive this complex retail and Mecham, 1972). It serves as the common denominator

environment, some retailers have created product develop-in compardevelop-ing the similarities and differences among jobs

ment divisions and developed private label products targeting (McCormick, Mecham, and Jeanneret, 1989). The PAQ has

specific consumer needs (Fickes, 1993; Moukheiber, 1993). been used by Fiorito and Fairhurst (1989) in their research

Through a private label program, retailers can pursue exclu-on job cexclu-ontent of small apparel retail buyers across four

mer-sivity from other retailers, control their product quality, keep chandise categories (men’s, women’s, children’s, and accessory

consistency in the product line, and have flexible pricing as and others). Job content and apparel buyers in large and small

well as higher margin (Glock and Kunz, 1990; Fickes, 1993). retail firms also were investigated through the PAQ by Fiorito

Private label provides consistency in terms of brand position-and Fairhurst (1993). With the exception of Fiorito position-and

Fair-ing by controllFair-ing what the brand represents and assurance hurst, few researchers have addressed job content in apparel

that quality standards are maintained (Adams, 1989). Retailers retailing.

have realized that the consistency is the key to success from season to season whether it’s in styling, price, or quality

(Mak-Apparel Merchandising and Line Development

ing A Name at Penney’s, 1991) or by particularly addressing Merchandising, marketing, finance, and operation are four a segment of the market (Barmash, 1986).

functional divisions in the apparel firm according to Kunz’s In 1992, Gaskill applied case study research methodology Behavioral Model (Kunz, 1995). While each division has its to study the private label process in the product development unique responsibility, it is the merchandising division that division of a specialty retail firm engaging in 100% product plays the integrative role in relation to the product line. The development (Gaskill, 1992). As a result of this study, Gaskill merchandising division, as the profit center, is responsible for developed a retail product development model for apparel the product line, which provides the firms’ primary source of retailers describing specific product development activities income. Therefore, merchandising plays the most crucial role conducted at the retail level.

in an apparel firm (Brauth and Brown, 1989; Brown and Brauth, 1989).

Purpose of the Study

Sheth’s (Sheth, 1973) industrial buyer behavior model iswith other departments, and activities related to line develop- mation, evaluating alternative supplies, and resolving conflicts among the parties engaged in decision making.

ment in the two diverse merchandising line development

pro-cesses of “traditional retail buying” and “retail product devel- Data on job responsibility, worker perceptions of job char-acterictics, and overall job satisfaction will be collected opment.”

through McCormick, Mecham, and Jeanneret’s (McCormick, Mecham, and Jeanneret, 1967, 1969) position analysis

ques-Hypotheses

tionnaire (PAQ), Hackman and Oldham’s (Hackman andOld-ham, 1975) job diagnostic survey (JDS), and Hoppock’s (Hop-Retail buyers have played an important role linking

manufac-pock, 1935) overall job satisfaction (OJS) measure from both turers and consumers by purchasing products from

manufac-traditional retail buyers and retail product developers. turers and merchandising them for ultimate consumer

con-Based on review of the literature, the following five hypoth-sumption. Particularly, apparel retail buyers play a crucial

eses were formulated to investigate. role as interpreters of current fashion trends and provide

information about merchandise. Retail buyers, as merchandis- H1: Apparel product developers will be significantly higher ers, are responsible for the most important and fundamental than traditional retail buyers on job content dimen-function in retailing, that of procuring appropriate products sions in terms of information input, mental processes, for their customers. Their job performance eventually can job context, devices and activities of job, interpersonal determine the success or failure of the retail store. activities, and miscellaneous aspects of job.

In the retail sector, however, some retailers have expanded

H2: Traditional retail buyers will be significantly higher their role in merchandising, advancing from traditional retail

than apparel product developers on overall worker buyers who selected products that were available in the market

perceptions in terms of their skill variety, task identity, to retailers that develop products. By actively engaging in the

task significance, autonomy, job feedback, feedback conceptualization, planning, development, and presentation

from others, and dealing with others. of market-oriented product lines, retailers have the advantages

H3: Traditional retail buyers will be significantly higher of market differentiation, higher margins, greater control, and

than apparel product developers in their overall job consumer-driven strategies.

satisfaction. Swindley (1992) investigated the role of buyers in the

H4: Apparel product developers will be significantly higher United Kingdom for clothing, grocery, and footwear business.

than traditional retail buyers in their interaction with He noted that buyers were not only involved in the selection,

other department. feasibility, and monitoring of products, but most buyers were

involved in product and packaging decisions, new product H5: Apparel product developers will be significantly higher launches, and quality control. Some stores put together prod- than traditional retail buyers in their activities related uct development teams that include designers, stylists, and to line development.

fashion buyers in order to develop their own collections and coordination accessories (Lebow, 1988). Department stores

currently deploy product development teams of designers and

Method

merchants (Agins, 1994). Swindley (1992) concluded thatSample Selection

buyers in large retail organizations have extended beyond thebuyers’ original role into product development, design, and The target sample for this study consisted of two groups of retailers including (1) individuals engaged in traditional retail marketing activities. Frank (1992) stated that it takes a high

level of skill, training, and experience to turn a retail buyer buying and (2) individuals involved in apparel product devel-opment. TheDirectory of Women’s and Children’s Wear Specialty

into a product developer. Increased knowledge and ability is

required to expand their role into product development. Stores(1995) andDirectory of Men’s and Boys’ Wear Specialty Stores(1995) were the sources used for sample selection. Recently, as technology and cultural patterns develop,

changes in the nature of jobs in the labor force are taking place. For locating the traditional retail buyers, a three-step sam-pling method was developed. First, a page of each directory In the past, emphasis has been placed on functional effectiveness

of jobs rather than human welfare as related to human work. was selected. Second, one store on each page was randomly selected and the percentage of sales in private label indicated In recent years, however, the emphasis has shifted toward the

aspects of human welfare, particularly job satisfaction and the in the store profile was reviewed. Following the predetermined operational definitions for product development and tradi-quality of working life (McCormick, 1979).

Sheth’s (Sheth, 1973) industrial buyer behavior model, tional retail buyers, the store was classified either as (1) a store with product developers (stores with 75–100% sales of which represents the traditional retail buying process in this

study, provides the theoretical framework and conceptualizes private label) or (2) a store with traditional retail buyers (stores with 0–25% sales of private label). When the selected store the process of fundamental organizational buying decisions

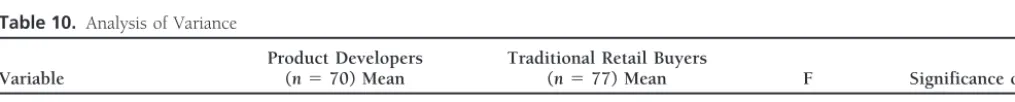

Table 1. Multivariate Analysis of Variance of Job Content for Product Developers and Traditional Retail Buyers: Hotellingst-test

Subscale Measure Value Exact F Hypothetical DF Error DF Significance of F

Information input 0.35 2.84 15.00 121.00 p50.001

Mental processes 0.23 3.10 10.00 134.00 p50.001

Job context 0.10 2.67 5.00 137.00 p50.025

Devices and activities of job 0.21 7.32 4.00 141.00 p50.000

Relationships with other persons 0.38 2.52 17.00 113.00 p50.002

Miscellaneous aspect of job 0.21 1.99 13.00 121.00 p50.027

of each executive was examined for selecting appropriate per- The intraclass coefficients of reliability ranged from upper 0.80’s to 0.90’s. In addition, Jeanneret and McCormick inde-sonnel. Appropriate job titles were adapted from the

Taxon-omy of Retail Careers (Kunz, 1985). A random numbers table pendently analyzed 62 jobs to test the reliability of the PAQ instrument and reported a 0.79 coefficient of reliability was used, once again, to select the final sample of retail buyers

from the potential list of relevant job titles. The sampling (McCormick, 1979).

The job elements in the PAQ are represented in six divisions method resulted in the location of a total of 249 traditional

retail buyers. and are rated with the use of a six-point Likert scales. Specific job elements in PAQ are information input, mental processes, For sampling product developers, census was used due to

the limited number of retailers heavily involved in product job content, devices and activities of the job, interpersonal activities, and miscellaneous aspects of the job.

development. First, all the stores in the directories listing private label sales ranging from 75–100% were identified. In

JOB CHARACTERISTICS. Twenty-one items used to investigate each of the selected stores, executives with appropriate job

job characteristics were adapted from the job diagnostic survey titles for product developers according to Wickett (1995) were

(Hackman and Oldham, 1975). The JDS provides measures identified. From that list of potential product developers, the

of seven major job dimensions including skill variety, task final sample of 250 product developers were chosen using a

identity, task significance, autonomy, job feedback, feedback systematic sampling method. In total, a sample size of 499

from others, and dealing with others (Hackman and Oldham, retailers was selected: 249 were identified as traditional retail

1975; McCormick, 1979; Taber and Tylor, 1990). buyers, and 250 were deemed to be product developers.

Hackman and Oldham (1975) reported reliability of the JDS ranging from a high of 0.88 to a low of 0.56. Respondents

The Data Collection Instrument

completed the instrument by using a seven-point scale. A self-contained and self-administered booklet type mailed

OVERALL JOB SATISFACTION. The third section was related to questionnaire was developed for data collection purposes. The

overall job satisfaction as measured by Hoppock’s (Hoppock, questionnaire consisted of six sections (see Appendix A) and

1935) four-item job satisfaction measure. Hoppock (1935) included the following content areas.

reported a Spearman-Brown reliability coefficient of 0.93. JOB CONTENT. Job content questions were based on the work McNichols, Stahl, and Manley (1978) concluded that Hop-of Fiorito and Fairhurst (1989, 1993), which incorporated

pock’s overall job satisfaction measure has significant utility the PAQ (position analysis questionnaire). Although human

in contemporary organization. The overall job satisfaction work tends to be more qualitative rather than quantitative in

measure was scored on a seven-point scale. its nature, the PAQ has enabled researchers to quantify the

structure of human work (McCormick, Jeanneret, and INTERACTION WITH OTHER DEPARTMENTS. The fourth section was developed to obtain information on the retailer’s interac-Mecham, 1972). The average item reliability coefficient for

PAQ was 0.80 (McCormick, Mecham, and Jeanneret, 1989). tion with other departments. It consisted of three open-ended

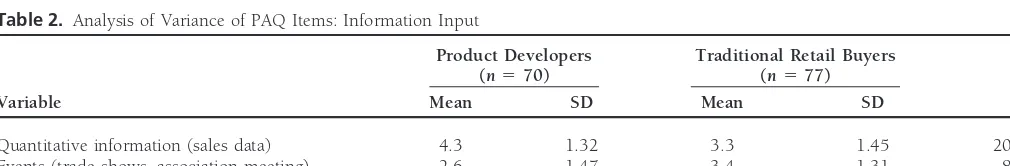

Table 2. Analysis of Variance of PAQ Items: Information Input

Product Developers Traditional Retail Buyers (n570) (n577)

Variable Mean SD Mean SD F

Quantitative information (sales data) 4.3 1.32 3.3 1.45 20.04a

Events (trade shows, association meeting) 2.6 1.47 3.4 1.31 8.18b

Estimating time for activities and events 3.5 1.44 3.0 1.32 5.03c

Table 3. Analysis of Variance of PAQ Items: Mental Processes

Product Developers Traditional Retail Buyers (n570) (n577)

Variable Mean SD Mean SD F

Use of mathematics 3.0 0.88 2.6 0.74 5.01a

Problem solving/analyzing 4.6 0.91 4.2 0.82 6.56a

Planning/scheduling 4.5 0.83 4.0 0.93 9.36b

Analyzing information 4.5 1.02 4.1 0.90 4.72a

Education 2.7 0.68 2.3 0.88 13.82c

ap

,0.05. bp

,0.01. cp

,0.001.

questions. Participants indicated whether or not they were spondent group. In summary, a total of two complete mailing of the instrument took place and three follow-up reminder engaged in team-oriented activities and the areas they

inter-acted most often with. postcards were mailed.

Whenever the mailings were returned and nondeliverable, ACTIVITIES RELATED TO LINE DEVELOPMENT. In order to

mea-those names were excluded from the sample. As a result of sure product knowledge related to line development, this

the 499 mailed questionnaires, a total of 475 were mailed and section consisted of 20 items measuring, on a five-point Likert

deliverable. Of the 475 delivered questionnaires, a total of scale, the extent to which the respondents were engaged in

147 were completed, returned, and usable, resulting in a 31% the product line development ranging from not at all(1) to

response rate.

intensively(5).

In order to support the generalizability of the present study, nonresponse bias was tested using the extrapolation method DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE. Finally, the sixth section collected

demographics on the respondents. Six questions concerning (Armstrong and Overton, 1977). Extrapolation method as-sumes that subjects who less readily respond (less readily respondent’s demographic profile such as gender, age,

educa-tion, title of posieduca-tion, and years of experience as a retail execu- means respond later or requires more stimulus to answer) are more like nonrespondents. People who responded later are tive were included.

The mailed questionnaire was pretested by four retail exec- expected to be similar to nonrespondents (Pace, 1978; Arm-strong and Overton, 1977). The differences between early utives randomly selected among the sample. The format of

the questionnaire was modified as needed to aid in readability respondents and late respondents (or nonrespondents) were compared in terms of demographic profiles.

and in ease of completion.

Those who returned early were regarded as respondents while late respondents were assumed to have close

characteris-Data Collection

tics of the nonrespondents. No significant differences between Data collection commenced guidelines established by

Dill-early respondents and late respondents who are assumed to man’s (Dillman, 1978) total design method. The

question-be nonrespondents were found. This result supports the valid-naires were mailed to 499 retail executives along with a cover

ity and generalizability of this study in that the participating letter, self-addressed, stamped return envelop. One week after

respondents fairly represented those who did not respond. the original mailing date, postcard reminders were sent to the

same group asking for a quick response. Three weeks later,

second reminder postcards were sent to nonrespondents ap-

Results and Discussion

pealing for return. Four weeks after the original mailing,re-Demographic Profile

placement questionnaires and return envelopes were sent tononrespondents. One week after the replacement question- Of the 147 usable responses, 70 were from product develop-ers, and 77 were from traditional retail buyers. Descriptive naire mailing, final reminder postcards were sent to the

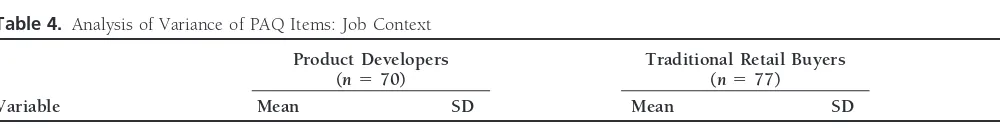

nonre-Table 4. Analysis of Variance of PAQ Items: Job Context

Product Developers Traditional Retail Buyers (n570) (n577)

Variable Mean SD Mean SD F

Civic obligation 1.7 1.54 2.5 1.59 8.20a

ap

Table 5. Analysis of Variance of PAQ Items: Devices and Activities of Job

Product Developers Traditional Retail Buyers (n570) (n577)

Variable Mean SD Mean SD F

Arranging/positioning objects and materials 2.6 1.71 3.7 0.97 23.05a

Physical handling objects and materials 2.4 1.69 3.4 1.13 18.05a

Physical exertion required 2.4 1.00 2.8 0.85 4.63b

ap

,0.001. bp

,0.05.

statistics showed that traditional retail buyers had a higher developers and traditional retail buyers. Results of the analyses and hypotheses testing follows.

portion of males (63% male versus 37% female) than in the groups of product developers (55% male versus 45% female).

HYPOTHESIS 1. The first hypothesis with regard to job content Respondents’ ages overall ranged from 18 to 83. Product

was supported. MANOVA showed significant differences in developers had lower mean age (X¯ 541.5) than traditional

each subdivision of hypothesis 1. The result of MANOVA is retail buyers (X¯547.8). Traditional retail buyers had a higher

shown in Table 1. F-test showed significant differences on number of average years of experience as a retail executive

each of the six overall variables of PAQ, including information (X¯5 19.5) compared with product developers (X¯5 16.2).

input, mental processes, job context, devices and activities of job, interpersonal activities, and miscellaneous aspect of job.

Reliability of Scales

All the overall variables in PAQ resulted in significant differ-Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for PAQ (position analysis

ences between the two groups (see Table 1). What follows is questionnaire) items. With the exception of work output, all

a specific analysis on each subdivision of PAQ. Only significant variables in PAQ had alpha scores higher than 0.70. In JDS

differences were illustrated in the tables. (job diagnostic survey) measurement, alpha scores ranged

from 0.44 to 0.66, and Hoppock’s overall job satisfaction INFORMATION INPUT. Overall significant differences (multi-measure had a high alpha score of 0.86. Cronbach’s alpha variate F52.84,p,0.01) existed between product develop-also was computed for the four factors of activities related to ers and traditional retail buyers in terms of information input line development. The alpha scores ranged from 0.72 to 0.91 (sources of information used in completing the job; see Table (see Appendix B). 1). Specifically, univariate analysis of variance showed that three of the fifteen subdivisions were rated differently by

prod-Results of Hypothesis Test

uct developers and traditional retail buyers. As compared with traditional retail buyers, product developers had significantly To test the suggested five research hypotheses, MANOVAhigher mean scores on the importance of estimating time for (multivariate analysis of variance), ANOVA (analysis of

vari-activities and events (X¯ 5 3.45), whereas traditional retail ance), and Chi-Square tests were used for statistical analyses to

investigate the differences between the two groups of product buyers, on the contrary, had a higher score on the use of

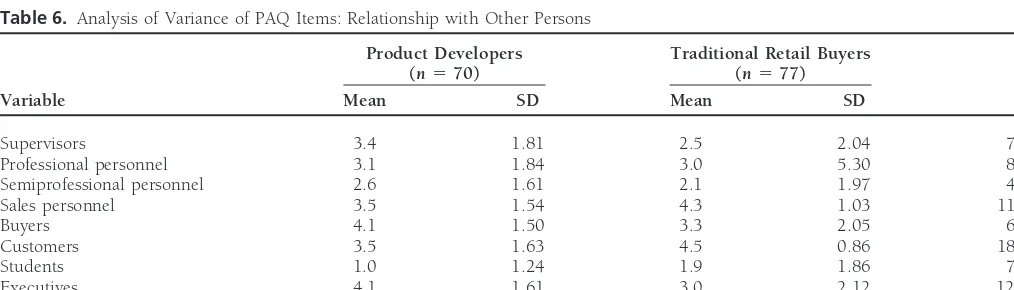

Table 6. Analysis of Variance of PAQ Items: Relationship with Other Persons

Product Developers Traditional Retail Buyers (n570) (n577)

Variable Mean SD Mean SD F

Supervisors 3.4 1.81 2.5 2.04 7.33a

Professional personnel 3.1 1.84 3.0 5.30 8.00b

Semiprofessional personnel 2.6 1.61 2.1 1.97 4.57b

Sales personnel 3.5 1.54 4.3 1.03 11.26a

Buyers 4.1 1.50 3.3 2.05 6.68a

Customers 3.5 1.63 4.5 0.86 18.52c

Students 1.0 1.24 1.9 1.86 7.06a

Executives 4.1 1.61 3.0 2.12 12.45b

Middle management 3.9 1.70 2.9 1.99 11.12a

ap

,0.01. bp

,0.05. cp

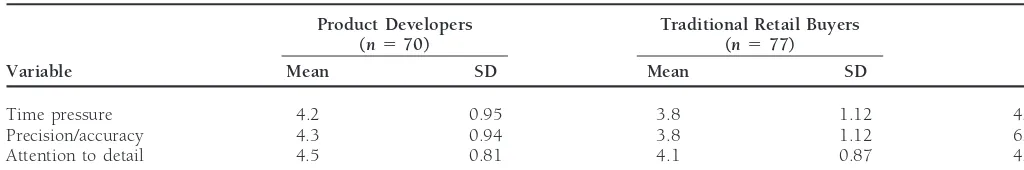

Table 7. Analysis of Variance of PAQ Items: Miscellaneous Aspect of Job

Product Developers Traditional Retail Buyers (n570) (n577)

Variable Mean SD Mean SD F

Time pressure 4.2 0.95 3.8 1.12 4.14a

Precision/accuracy 4.3 0.94 3.8 1.12 6.90a

Attention to detail 4.5 0.81 4.1 0.87 4.33a

ap

,0.05.

events (trade shows, association meeting) (X¯53.41) in per- subdivisions among four. Specifically, arranging/ positioning objects and materials, and physical handling objects and mate-forming their job. Particularly, product developers were

signif-icantly more likely to use quantitative information (sales data) rials were perceived to be significantly important activities in the job of a traditional retail buyer compared with product (X¯54.29) in completing their jobs than were the traditional

retail buyers (X5 3.45; see Table 2). developers (p , 0.001). Traditional retail buyers, however, reported a higher score on the level of physical exertion re-MENTAL PROCESSES. An overall difference between the two

quired to perform the job than did product developers (see groups (multivariate F53.10,p,0.01) was found in mental

Table 5). This result indicates that traditional retail buyers processes employed in the job (see Table 1). ANOVA showed

are more involved in physically oriented tasks because of their five out of ten subdivisions were perceived to be significantly

major tasks of buying and selling activities. differently between product developers and traditional retail

buyers. Product developers were more likely to require the RELATIONSHIP WITH OTHER PERSONS. Overall, Multivariate use of mathematics on the job than were traditional retail F-test (F52.52) showed significant difference at p, 0.01 buyers. Product developers also had higher scores and were (see Table 1). Nine of seventeen subdivisions were perceived significantly more likely to employ the mental processes of to be significantly differently. Interaction with supervisors, problem solving/analyzing (X¯ 5 4.58), planning/scheduling professional personnel, semiprofessional personnel, buyers, (X¯54.46), and analyzing information (X¯54.49) than were and middle management were more important for the product the traditional retail buyers. The level of education necessary developers than they were for traditional retail buyers, while for the job activities also was perceived to be significantly interacting with sales personnel, customers and students were different between the product developers and traditional retail perceived to be more important for the traditional retail buyers buyers at the significance level ofp , 0.001 (see Table 3). (see Table 6). This may imply that traditional retail buyers, Traditional retail buyers were more likely to indicate the neces- who are primarily engaged in buying and selling activities, sary education to be the level obtained by some college work, have a closer relationship with persons who are easily con-whereas, the retail product developers were more likely to tacted at the stores such as customers and sales personnel indicate the necessary level to be that which is by the comple- while product developers engaged in product line develop-tion of usual college curriculum. ment tend to cooperate and interact with people in various

levels of the organizational setting. JOB CONTEXT. An overall difference between the two groups

(multivariate F5 2.67,p, 0.05) was found (see Table 1).

MISCELLANEOUS ASPECTS OF JOB. Multivariate F-test (F 5

Univariate analysis of variance resulted in a difference between

1.99, p , 0.05) showed that there is an overall difference the two groups in terms of civic obligations (p,0.01).

Tradi-between the two groups in miscellaneous aspects of job (see tional retail buyers (X¯52.50) perceived it to be more important

Table 1). Three subdivisions out of thirteen were perceived than did the product developers (X¯51.17; see Table 4).

different by product developers and traditional retail buyers. Product developers were significantly more likely to rate time DEVICES AND ACTIVITIES OF JOB. Overall significant difference

pressure, precision/accuracy, and attention to detail as a more (multivariate F57.32,p,0.001) existed between product

important job demand compared with traditional retail buyers developers and traditional retail buyers (see Table 1).

Univari-ate analysis of variance showed significant differences in three (see Table 7).

Table 8. Multivariate Analysis of Variance of Job Characteristics for Product Developers and Traditional Retail Buyers (Hotellingst-test)

Test Value Exact F Hypothetical DF Error DF Significance of F

Table 9. Analysis of Variance of Job Characteristics

Product Developers Traditional Retail Buyers (n570) (n577)

Variable Mean SD Mean SD F

Autonomy 6.0 0.95 6.4 0.70 6.65a

Dealing with others 6.5 0.68 6.1 0.87 10.95b

Feedback from agent 4.2 1.38 4.4 1.39 0.18

Feedback from job 5.4 1.10 5.4 1.07 0.15

Skill variety 6.0 0.90 5.5 1.05 10.39a

Task significance 5.9 1.08 5.5 1.21 1.00

Task identity 5.3 1.52 5.2 1.22 4.38a

ap

,0.05. bp,0.01.

Overall, product developers seemed to perform a job that because they may work at a smaller organization scale than requires a higher level of mental processes precision/accuracy, product developers.

attention to detail, time consciousness, problem solving,

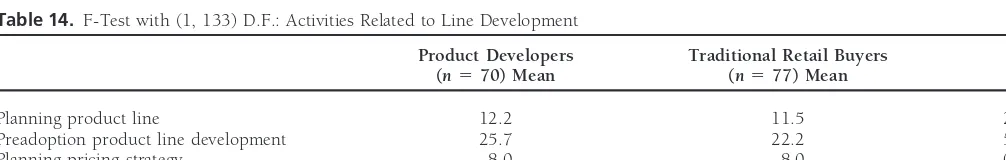

anal-HYPOTHESIS 3. Hypothesis 3 was supported. ANOVA (F5

ysis, and quantitative skills. Traditional retail buyers, however,

9.813,p50.002) showed the interesting result that overall job seemed to be engaged in simpler tasks requiring more physical

satisfaction is significantly different between the two groups. exertion.

Specifically, product developers reported lower levels of job Out of sixty-four total PAQ job content elements and

satisfaction (X¯55.22) than did traditional retail buyers (X¯5

items, ten (16%) were perceived differently between groups

5.69; see Table 10). The Hackman et al.’s (Hackman, Oldham, at the significance level ofp,0.05, nine (14%) were perceived

Janson, and Purdy, 1975) JCM (job characteristic model) es-differently at the significance level ofp,0.01, and five (8%)

tablished the causal relationship between the core job charac-were perceived differently at the significance level of p ,

teristics and job satisfaction, suggesting that the core job char-0.001.

acteristics lead to job satisfaction. However, autonomy and HYPOTHESIS 2. Multivariate F-test (F 5 4.68) showed an task identity, areas where traditional retail buyers reported overall difference between product developers and traditional higher scores, could be major factors affecting job satisfaction. retail buyers at the significance level ofp,0.001 on overall

HYPOTHESIS 4. A significant difference (p,0.01) was found worker perceptions (see Table 8). Traditional retail buyers

between product developers and traditional retail buyers, sup-reported more autonomy (X¯56.35) and task identity (X¯5

porting hypothesis four. Chi-Square test was used to investi-5.22) than did product developers (X¯55.96 for autonomy

gate the difference between product developers and traditional and X¯ 5 5.01 for task identity). Product developers had

retail buyers regarding interaction with other departments. significantly higher scores in terms of dealing with others (X¯5

Significantly more product developers (75%) answered “yes” 6.51) and skill variety (X¯55.99) than traditional retail buyers

to a question asking whether or not they were engaged in (X¯ 5 6.35 for dealing with others and X¯ 5 5.46 for skill

team-oriented activities compared with traditional retail buy-variety), both at the significance levelp, 0.001 (see Table

ers (51%). Table 11 shows the number and percentages of 9). Product developers required a variety of skills and talents

respondents who are engaged in team-oriented activities for and different activities in performing their job. They also need

both the product developers and traditional retail buyers. This to be able to work with organization members in completing

finding confirms what had been found in hypothesis one and their job-related product development activities. Noticeably,

two in that the product developers’ job may require the use traditional retail buyers, who were found to carry out less

of a wide range of relationships and high level of interaction complex but more physical exertion–requiring tasks, had

in their job performance. higher autonomy and task identity. Their job may have a

visible outcome and the job-related tasks are easily identified Those who answered that they were involved in

team-Table 10. Analysis of Variance

Product Developers Traditional Retail Buyers

Variable (n570) Mean (n577) Mean F Significance of F

Overall job satisfaction 5.2 5.7 9.18 p50.002

Table 11. Chi-Square Test: Team-Oriented Activity

Product Developers Traditional Retailer Buyers

(n570) (n577) Pearson Chi-Square

Yes (%) 48 (75.0) 34 (57.5) 8.22a

No (%) 16 (25.0) 33 (42.5)

Total (%) 64 (100.0) 67 (100)

ap

,0.01.

oriented activities were asked in open-ended questions to adoption product development (see Table 12). Satisfying the assumption that those four factors were highly correlated with indicate what job-related activities they did as a team. A large

number of respondents indicated specific merchandising ac- each other, MANOVA was used to test hypothesis five. The overall F-test (F 5 3.2, DF 5 130) showed a significant tivities such as buying (N 511), sales (N 55), forecasting

trends (N54), inventory control (N52), assortment plan- difference between the two groups at the significance level of ning (N52), product development (N52), line presentation p, 0.05 (see Table 13).

(N 5 1), pricing planning (N 5 1), etc. However, some Before MANOVA test, Univariate F-test was conducted to respondents answered that they were engaged in strategic further explore differences between product developers and planning (N55), decision making (N55), problem solving traditional retail buyers regarding individual activity factors. (N 5 3), communication (N 5 3), setting goals (N 5 2), Preadoption product line development activities and post-motivating (N51), and more. This result is consistent with adoption product development were significantly different the behavioral theory of the apparel firm (Kunz, 1995), which between the two groups. Product developers were found to suggests that the behavioral aspects of decision making, com- have higher mean scores on preadoption product development munication, and problem solving within a firm is a key func- activities (X¯525.74) and postadoption product development tion in the merchandising division. (X¯5 12.82), than did traditional retail buyers (X¯ 5 22.23

The respondents were asked to indicate three departments andX¯510.32, respectively; see Table 14). they interact most often with. Both product developers and

traditional retail buyers had similar responses to this question

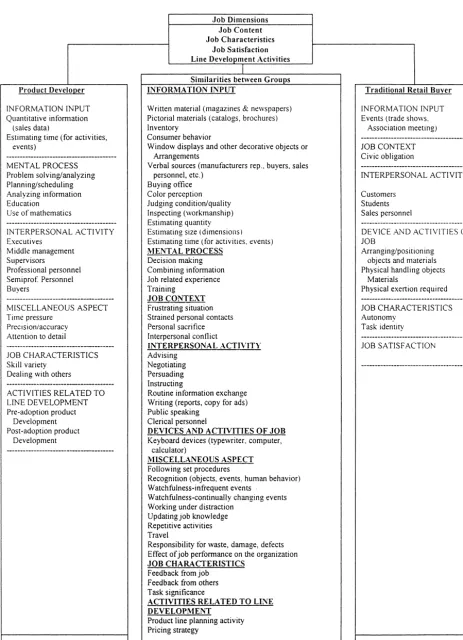

Conclusions

(i.e., finance, store operations, personnel, sales promotion,merchandising, and production). No significant differences The results of this study provided a considerable number of

were reported. significant differences between apparel product developers

and traditional retail buyers and supported the five proposed HYPOTHESIS 5. In order to test hypothesis five, MANOVA

hypotheses. Figure 1 illustrates the discriminating job ele-was used with the factors generated from principal component

ments between product developers and traditional retail buy-factor analysis as a statistical analysis method. Before

MA-ers along with shared elements or “similarities” of the two NOVA was run, correlation coefficients matrix were reviewed

groups. The numerous similarities between the two groups to investigate the strength of the correlation between four

should be carefully considered by training personnel in de-generated factors. Pearson test showed a significant

relation-termining which job content can be commonly provided and ship among the four factors, specifically between product line

which cannot in situations where product development and planning activity and preadoption product line development,

traditional retail buying take place simultaneously. Similarities product line planning activity and planning pricing strategy,

in study results between groups give insight into educational preadoption product line development and planning pricing

strategy, and preadoption product line development and post- content to be addressed.

Table 12. Correlation Matrix by Activities Related to Line Development

Postadoption Product Line Product Line Pricing Strategy Product Variable Planning Activity Development Planning Development

Product line planning activity 1.000 0.333a 0.422a 0.006

Preadoption product line development 1.000 0.486a 0.582

Pricing strategy planning 1.000 0.199b

Postadoption product development 1.000

ap

,0.01. bp

Table 13. Multivariate Hotellingst-Tests of Significance: Activities Related to Line Development

Test Value Hotelling-Lawley Trace F Hypoth. DF Error DF Significance of F

Hotelling-Lawley Trace 0.098 3.20 4.00 130.00 p50.015

Despite the fact that the results of this study provided product development as a differential strategy in today’s de-pressed and competitive retail environment. Repositioning evidence that product developers need a higher level of

job-related skills and knowledge than traditional retail buyers, the and retraining current retail buyers to engage in product devel-opment is not a simple matter. Not only do the general mer-two groups did view the need for updated job knowledge,

job-related experience, and training similarly. This finding chandising activities significantly differ, but specific behavioral dimensions differ with the greater challenge with the product suggests that retailers, whether they are engaged in the product

development process or not, value and recognize the need for developer.

These study results also should be useful to retail personnel training, experience, job-related skills, and updated knowledge.

From the demographic profile of the subjects in this study, managers. Such individuals have responsibility for generating job analysis information. Information that is deemed necessary traditional retail buyers had more years of retail experience

than did the product developers. However, the product devel- in personnel recruitment and selection, training, performance assessment, job evaluation, and job design.

opers had a higher educational level than did the traditional

retail buyers. Product developers, also, rated the importance Study results should be carefully considered by educators responsible for the training and development of tomorrow’s of education higher than did the traditional retail buyers. This

finding, in part, supports the belief of Frank (1992) that it merchandisers. Students on college campuses who are prepar-ing for retail careers can benefit through an understandprepar-ing of requires a high level of knowledge, education, and training

in order to transform a buyer into a product developer. Until the differences and similarities between product developers and traditional retail buyers in terms of their job requirements. the completion of this study, however, the extent to which the

job content and worker perceptions differed for the individuals

engaged in the merchandising line development process was

Limitations

not understood. This finding, alone, has significantimplica-tions for apparel companies that are either currently operating This study has several limitations including those attributed to the JDS (job diagnostic survey) instrument measure. The or initiating product development programs, or reengineering

traditional retail buyers to become product developers. Cronbach’s alpha scores were relatively low but increased if negative wording items were deleted. Factor loadings were In comparison to traditional retail buyers, this study also

found product developers used more quantitative information also low ranging from 0.19 to 0.84. This raises a question regarding the reliability of the JDS measurement.

(sales data) and mathematics; required more planning and

scheduling; analyzing and problem solving; precision, accu- Secondly, combining four different measurement instru-ments and differing scales lessened the consistency of the racy, attention to detail; and time consciousness. Traditional

retail buyers, compared with product developers, were found format of the questionnaire and resulted in difficulty in data analysis. Also, using open-ended questions in a mailed ques-to be more physical exertion–oriented in performing their job.

These findings do offer evidence that the product development tionnaire to inquire about interactions with other departments did not allow for probing and reminding tools. Other data position in retailing requires a higher level of skills and ability

in their job performance than currently exists in the traditional gathering methods could have allowed for more in-depth and meaningful responses.

retail buyer role.

Study findings should be carefully considered by contem- Another limitation of the study is the control of extraneous variables. The product line development process at the retail porary retailers as increasing numbers of retailers turn to

Table 14. F-Test with (1, 133) D.F.: Activities Related to Line Development

Product Developers Traditional Retail Buyers

(n570) Mean (n577) Mean F

Planning product line 12.2 11.5 2.59

Preadoption product line development 25.7 22.2 5.56a

Planning pricing strategy 8.0 8.0 0.10

Postadoption product development 12.8 10.3 4.75a

ap

in Large and Small Retail Firms.Clothing and Textiles Research level likely exists in a larger company because it requires a

Journal4 (1993): 1–8.

relatively high investment and product development experts.

Ford, R. N.:Motivation through the Work Itself, American Management

Other than the type of retailers (whether they are product

Association, Inc., New York. 1969.

developers or traditional retail buyers), the size of a company

Francis, S. K., and Brown, D. J.: Retail Buyers of Apparel and

Appli-in which the respondents were engaged Appli-in could be Appli-

inter-ances: A Comparison. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 4

rupted as an extraneous variable. (1986): 1–8.

Finally, this study was limited to men’s and boy’s, and

Frank, B.: Merchandising Private Label Apparel.Retail Business Review women’s and children’s specialty stores. The result of this 60 (1992): 24–26.

study may not be generalized to other retail sectors, such as

Gaskill, L. R.: Toward A Model of Retail Product Development: A

mail-order catalogue, department, and discount store retailers. Case Study Analysis. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 10 Generalizability of the study results has yet to be determined. (1992): 17–24.

Germeroth, E. A.: Retail Challenge: The Consumer of the 1990’s.

Discount Merchandiser34 (May 1992a): 84–88.

References

Germeroth, E. A.: They Won’t Stop till They Drop.Bobbin34 (Decem-Adams, M. J.: Private Label Programs: Major Changes.Stores71 (June

ber 1992b): 64–68. 1989): 10–19.

Glock, R. E., and Kunz, G. I.:Apparel Manufacturing-Sewn Product

Agins, T.: Big Stores Put Own Labels on Best Clothes.Wall Street

Analysis, Macmillan, New York. 1990.

Journal(September 26, 1994): B1, B10.

Hackman, J. R., and Oldham, G. R.: Development of the Job Diagnos-Anthony, C. A. E., and Jolly, L. D.: The Influence of Uncertainty

tic Survey.Journal of Applied Psychology60 (1975): 159–170. on Ratings of Information Importance by Retail Apparel Buyers.

Clothing and Textiles Research Journal10 (1991): 1–7. Hackman, J. R., and Oldham, G. R.: Motivation through the Design of Work: Test of a Theory.Organizational Behavior and Human

Armstrong, J. S., and Overton, T. S.: Estimating Nonresponse Bias

Performance16 (1976): 250–279. in Mail Surveys.Journal of Marketing Research16 (1977): 196–402.

Hackman, J. R., Oldham, G. R., Janson, R., and Purdy, K.: A New Barmash, I.: Strategies for Private Brand Growth. Stores 68 (April

Strategy for Job Enrichment. California Management Review 18 1986): 24–28.

(1975): 57–71. Bergman, J.: Cookie-Cutters and Clones? Stores 67 (June 1985):

Hoppock, R.:Job Satisfaction, Harper & Brothers, New York. 1935. 14–97.

Reprint edition by Arno Press, New York. Bowditch, J. L., and Buono, A. F.:A Primer on Organizational Behavior,

Jernigan, M. H., and Easterling, C. R.:Fashion Merchandising and

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York. 1994.

Marketing, Macmillan Publishing Company, New York. 1990. Brauth, B., and Brown, P.: Merchandising Methods.Apparel Industry

Kline, B., and Wagner, J.: Information Sources and Retail Buyer

Magazine(1989): 108–110.

Decision Making: The Effect of Product-Specific Buying Experi-Brown, P., and Brauth, B.: Merchandising Methods.Apparel Industry

ence.Journal of Retailing70 (1994): 75–88.

Magazine(1989): 78–82.

Kunz, G. I.:Career Development of College Graduates Employed in

Clodfelter, R.:Retail Buying: From Staples to Fashions to Fads, Delmar Retailing.Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Iowa State Univer-Publisher Inc., New York. 1993. sity, Ames, IA 1985.

Davis, L. E., and Tylor, J. C.:Design of Jobs, Cox & Wyman Ltd., Kunz, G.I.: Behavioral Theory of the Apparel Firm: A Beginning. London. 1972. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal13 (1995): 252–261. Dillman, D. A.:Mail and Telephone Surveys: The Total Design Method, Landy, F. J.:Psychology of Work Behavior, The Dorsey Press,

Home-John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York. 1978. wood, IL. 1985.

Directory of Men’s and Boys’ Wear Specialty Stores 1995, Business Lebow, J.: Private Label Luxury.Harpers Bazaar121 (March 1988):

Guide, New York. 1995. 206–207.

Directory of Women’s and Children’s Wear Specialty Stores 1995, Busi- Making A Name at Penney’s.Apparel Merchandising9 (1990): 28–29. ness Guide, New York. 1995.

McCormick, E. J.:Job Analysis: Methods and Applications, AMACOM, Dunham, R. B., Aldag, R. J., and Brief, A. P.: Dimensionality of Task New York. 1979.

Design as Measured by the Job Diagnostic Survey.Academy of

McCormick, E. J., Jeanneret, P. R., and Meecham, R. C.: Position

Management Journal20 (1977): 209–223.

Analysis Questionnaire (Form A). Occupational Research Center, Epstein, S. H.: Understanding the Consumer in the ’90s.Discount Department of Psychology, Purdue University, West Lafayette,

Merchandiser32 (December 1992): 44–45. IN. 1967.

Ettenson, R., and Wagner, J.: Retail Buyers’ Salability Judgments: A McCormick, E. J., Jeanneret, P. R., and Meecham, R. C.: Position Comparison of Information Use Across Three Levels of Experi- Analysis Questionnaire (Form B). Occupational Research Center, ence.Journal of Retailing62 (1986): 41–63. Department of Psychology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Fickes, M.: Private Label: It’s Coming around Again.Bobbin35 (De- IN. 1969.

cember 1993): 70–71. McCormick, E. J., Jeanneret, P. R., and Mecham, R. C.: A Study of Fiorito, S. S., and Fairhurst, A. E.: Buying for the Small Apparel Job Characteristics and Job Dimensions as Based on the Position Retail Store: Job Content across Four Merchandise Categories. Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ).Journal of Applied Psychology Mono-Clothing and Textiles Research Journal8 (1989): 10–21. graph56 (1972): 347–368.

McCormick, E. J., Mecham, R. C., and Jeanneret, R. P.:Technical

Manual for the Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ), 2nd edition, Apparel Buyers.Clothing and Textiles Research Journal10 (1991): 20–30.

PAQ Service, Inc., IN. 1989.

Soderquist, D. G.: Presidents’ Round Table: Value-Driven Consum-McCormick, E. J., and Tiffin, J.:Industrial Psychology, 6th edition,

ers.Discount Merchandiser33 (December 1993): 61–62. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. 1974.

Swindley, D. G.: The Role of the Buyer in UK Multiple Retailing. McNichols, C. W., Stahl, M.J., and Manley, T.R.: A Validation of

International Journal of Retailing and Distribution Management20(2) Hoppock’s Job Satisfaction Measure.Academy of Management

Jour-(1992): 3–15.

nal21 (1978): 737–742.

Taber, T. D., and Tylor, E.: A Review and Evaluation of the Psycho-Meister, D.: Behavioral Analysis and Measurement Methods, Wiley,

metric Properties of the Job Diagnostic Survey.Personnel

Psychol-New York. 1985.

ogy43 (1990): 467–500.

Moin, D.: Experts Say Stores Can’t Rest on Laurels.Women’s Wear Underwood, E.: Something for Everyone.Brand Week33 (September

Daily, January 13, 1986, p. 7. 1992): 9–24.

Morgenson, G.: Back to Basics.Forbes(May 1993): 56–8. Wagner, J., Ettenson, R., and Parrish, J.: Vendor Selection among Retail Buyers: An Analysis by Merchandise Division. Journal of

Moukheiber, Z.: Out Competitive Advantage.Forbes(April 1993):

Retailing65 (1989): 58–79. 59–62.

Wanous, J. P.: Individual Differences and Reactions to Job Character-Muchinsky, P. M.: Psychology Applied to Work: An Introduction to

istics.Journal of Applied Psychology59 (1974): 616–622.

Industrial and Organizational Psychology, The Dorsey Press,

Home-Wickett, J. L.:Apparel Retail Product Development: Model Testing and

wood, IL. 1983.

Expansion. Unpublished master’s thesis, Iowa State University, Organ, D. W., and Hamner, W. C.: Organizational Behavior: An

Ames, IA 1995.

Applied Psychological Approach, Business Publications, Inc., Plano,

Wickett, J. L., Gaskill, L. R., and Damhorst, M. L.: Apparel Retail TX. 1982.

Product Development Mode Testing and Expansion.Clothing and

Pace, C. R.: Factors Influencing Questionnaire Returns from Former Textiles Research Journal17(1) (1999): 21–35. University Students.Academy of Management Journal21 (1978):

Why Designer Labels Are Fading?Business Week(February 1983): 737–742.

70–71.

Sheth, J. N.: A Model of Industrial Buyer Behavior.Journal of Market- Wilensky, D.: Store Brands Take Paramount Importance as Retailers ing37 (1973): 50–56. Scale Back National Brands.Discount Store News, May 16, 1994,

APPENDIX A. Job Content, Worker Perception, and Job Satisfaction in Retail Merchandising Line Development Process (Section One)

Please complete the following questions based on your present company position. This segment of the questionnaire will be used to analyze the type of work you are presently doing. Please answer by circling the most accurate response using the scale provided.

Q-1. Evaluate the use of the following in performing your job:

Sources of Information

Very Nominal/ Very

Does not Infrequent Occasional Moderate Considerable Substantial Apply (N) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

a Written material (trade

magazines & newspapers) N 1 2 3 4 5

b Quantitative information (sales data) N 1 2 3 4 5

c Pictorial materials (catalogs, brochures) N 1 2 3 4 5

d Inventory N 1 2 3 4 5

e Consumer behavior N 1 2 3 4 5

f Events (trade shows, association meetings) N 1 2 3 4 5

g Window displays and other decorative

objects or arrangements N 1 2 3 4 5

h Verbal sources (manufacturers rep.,

buyers sales, personnel, etc.) N 1 2 3 4 5

i Buying Office N 1 2 3 4 5

Q-2. Evaluate the importance of the following activities in the completion of your job:

Activities for Completion of Job

Low Average Extreme Does not Very Importance Importance High Importance Apply (N) Minor (1) (2) (3) Importance (4) (5)

a Color perception N 1 2 3 4 5

b Judging condition/quality N 1 2 3 4 5

c Inspecting (workmanship) N 1 2 3 4 5

d Estimating quantity N 1 2 3 4 5

e Estimating size (dimensions) N 1 2 3 4 5

f Estimating time (for activities, events) N 1 2 3 4 5

Q-3. To what extent is the N Does not apply

level ofeducation 1 Less than that required for completion of H.S. curriculum necessary to you in 2 Level obtained by some college work

your job activities? 3 Level obtained by completion of usual college curriculum (Circle one) 4 Level obtained by completion of advanced curriculum Q-4. To what extent is N Does not apply

job related experience 1 Less than one month

necessary to you in 2 Over 1 month up to and including 12 months your job activities? 3 One to three

(Circle one) 4 Three to five years 5 Over five years Q-5. To what extent is N Does not apply

trainingrequired 1 Over 1 day up to and including 30 days for your job? 2 Over 30 days up to and including 6 months (Circle one) 3 Over 6 months up to and including 1 year

4 Over 1 year up to and including 3 years 5 Over 3 years

Q-6. To what extent is the N Does not apply

use of mathematics 1 Simple basic required for your job? 2 Basic (Circle one) 3 Intermediate

4 Advanced 5 Very advanced

APPENDIX A. continued

Please complete the following questions based on your present company position. This segment of the questionnaire will be used to analyze the type of work you are presently doing. Please answer by circling the most accurate response using the scale provided.

Q-7. Evaluate the following mental processes employed in your job:

Mental Process

Does not Very Very

Apply (N) Limited (1) Limited (2) Intermediate (3) Substantial (4) Substantial (5)

a Decision making N 1 2 3 4 5

b Problem solving/Analysis N 1 2 3 4 5

c Planning/Scheduling N 1 2 3 4 5

d Combining information N 1 2 3 4 5

e Compiling information N 1 2 3 4 5

f Analyzing information N 1 2 3 4 5

Q-8. Evaluate the importance of the following aspects of interaction with other people in your job:

Relationship with Other Persons

Not Very

Important (N) Minor (1) Low (2) Average (3) High (4) Extreme (5)

a Advising N 1 2 3 4 5

b Negotiating N 1 2 3 4 5

c Persuading N 1 2 3 4 5

d Instructing N 1 2 3 4 5

e Routine information exchange N 1 2 3 4 5

f Writing (reports, copy for ads) N 1 2 3 4 5

g Public speaking N 1 2 3 4 5

Q-9. Evaluate the importance of the following demands in your job:

Job Demand

Does not Very Low Average High Extreme Apply (N) Minor (1) Importance (2) Importance (3) Importance (4) Importance (5)

a Following set procedures N 1 2 3 4 5

b Time pressure N 1 2 3 4 5

c Precision/Accuracy N 1 2 3 4 5

d Attention to detail N 1 2 3 4 5

e Recognition (object, events,

human behavior) N 1 2 3 4 5

f Watchfulness-infrequent

events N 1 2 3 4 5

g Watchfulness-continually

changing events N 1 2 3 4 5

h working under distraction N 1 2 3 4 5

i Updating job knowledge N 1 2 3 4 5

j Repetitive activities N 1 2 3 4 5

k Travel N 1 2 3 4 5

Q-10. What is the degree to which you are directly responsible for waste, damage, defects, or other loss of value to material assets?: (Circle one)

1 Very limited 2 Limited 3 Intermediate 4 Substantial 5 Very substantial

APPENDIX A.continued

Please complete the following questions based on your present company position. This segment of the questionnaire will be used to analyze the type of work you are presently doing. Please answer by circling the most accurate response using the scale provided.

Q-11. What is the degree to which the performance of your activities are critical in terms of their possible effects on the organization?: (Circle one)

1 Very low degree of criticality 2 Low degree of criticality 3 Moderate degree of criticality 4 High degree of criticality 5 Very high degree of criticality

Q-12. What level of physical exertion is required to perform your job?: (Circle one) 1. Very light

2. Light 3 Moderate 4 Heavy 5 Very Heavy

Q-13. Evaluate the importance of the following devices and activities in your job:

Devices and Activities of Job

Does not Very Low Average High Extreme Apply (N) Minor (1) Importance (2) Importance (3) Importance (4) Importance (5)

a Keyboard devices (typewriter,

computer, calculator) N 1 2 3 4 5

b Arranging/Positioning objects

and materials N 1 2 3 4 5

c Physically handling objects

and material N 1 2 3 4 5

Q-14. Evaluate the importance of interaction with the following people in your job:

Job-Required Personal Contact

Does not Very Low Average High Extreme Apply (N) Minor (1) Importance (2) Importance (3) Importance (4) Importance (5)

a Executive N 1 2 3 4 5

b Middle Management N 1 2 3 4 5

c Supervisors N 1 2 3 4 5

d Professional personnel N 1 2 3 4 5

e Semiprof. personnel N 1 2 3 4 5

f Clerical personnel N 1 2 3 4 5

g Sales personnel N 1 2 3 4 5

h Buyers N 1 2 3 4 5

i Customers N 1 2 3 4 5

j Students N 1 2 3 4 5

Q-15. Evaluate the importance of the following aspects in your job:

Personal and Social Aspect

Does not Very Low Average High Extreme Apply (N) Minor (1) Importance (2) Importance (3) Importance (4) Importance (5)

a Civic obligations N 1 2 3 4 5

b Frustrating situation N 1 2 3 4 5

c Strained personal contacts N 1 2 3 4 5

d Personal sacrifice N 1 2 3 4 5

e Interpersonal conflict N 1 2 3 4 5

APPENDIX A. continued

Please complete the following questions based on your present company position. This segment of the questionnaire will be used to analyze the type of work you are presently doing. Please answer by circling the most accurate response using the scale provided.

Section Two

This part of the questionnaire asks you to describe your job, asobjectivelyas you can.

Please donotuse this part of the questionnaire to show how much you like or dislike your job. Questions about that will come later. Instead, try to make your description as accurate and as objective as you possibly can.

A sample question is given below.

A. To what extent does your job require you to work with mechanical equipment?

1 ________ 2 ________ 3 ________ 4 ________ 5 ________ 6 ________ 7

Very little; the job requires almost Moderately Very much; the job requires almost

no contact with constant work with equipment of

mechanical any kind. mechanical equipment.

You are tocirclethe number which is the most accurate description of your job.

If, for example, your job requires you to work with mechanical equipment a good deal of time-but also requires some paperwork-you might circle the number six, as was done in the example above.

Q-16. To what extent does your job require you to work closely with other people (either O` clientsO´ or people in related jobs in your own organization?)

1 ________ 2 ________ 3 ________ 4 ________ 5 ________ 6 ________ 7

Very little; dealing with other people Moderately; Some dealing with others Very much; dealing with other people is not at all necessary in doing the job. in necessary. is an absolutely essential

and crucial part of doing the job. Q-17. How much autonomy is there in your job? That is, to what extent does your job permit you to decide on your own how to go about the work?

1 ________ 2 ________ 3 ________ 4 ________ 5 ________ 6 ________ 7

Very little; the job gives me almost no Moderate autonomy; many things are Very much; the job gives me almost personal O` sayO´ about how and when standardized and not under my complete responsibility for deciding the work is done. control, but I can make some how and when the work is done.

decisions about the work.

Q-18. To what extent does your job involve doing a O` wholeO´ and identifiable piece of work? That is, is the job a complete piece of work that has an absolute beginning and end? Or is it only a small part of the overall piece of work, which is finished by other people or by automatic machines?

1 ________ 2 ________ 3 ________ 4 ________ 5 ________ 6 ________ 7

My job is only a tiny part of the overall My job is a moderate sized chunk of the My job involves doing the whole piece piece of work, the results of my overall piece of work, my own of work from start to finish. activities cannot be seen in the final contribution can be seen in the final

product or service. outcome.

Q-19. How much variety is there in your job? That is, to what extent does the job require you to do many different things at work, using a variety of your skills and talents?

1 ________ 2 ________ 3 ________ 4 ________ 5 ________ 6 ________ 7

Very little; the job requires me to do the Moderately variety Very much; the job requires me to do same routine things over and over many different things, using a number

again. of different skills and talents.

Q-20. In general, how significant or important is your job? that is, are the results of your work likely to significantly affect the lives or well-being of other people?

1 ________ 2 ________ 3 ________ 4 ________ 5 ________ 6 ________ 7

Not very significant; the outcomes of my Moderately significant Highly significant; the outcomes of my work are not likely to have important work can affect other people in very

effects on other people. important ways.

APPENDIX A. continued

Please complete the following questions based on your present company position. This segment of the questionnaire will be used to analyze the type of work you are presently doing. Please answer by circling the most accurate response using the scale provided.

Q-21. To what extent do managers or co-workers let you know how well you are doing on your job? 1 ________ 2 ________ 3 ________ 4 ________ 5 ________ 6 ________ 7

Very little; people almost never let me Moderately; sometimes people may give Very much; managers or co-workers know how well I am doing. me “feedback”, other times they provide me with almost constant

may not. “feedback” about how well I am doing.

Q-22. To what extent does doing the job itself provide you with information about your work performance? That is, does the actual work itself provide clues about how well you are doing-aside from any “feedback” co-worker or supervisors may provide?

1 ________ 2 ________ 3 ________ 4 ________ 5 ________ 6 ________ 7

Very little; the job itself is set up so I Moderately; sometimes doing the job Very much; the job is set up so that I could work forever without finding provides “feedback” to me, sometimes get almost constant “feedback” as I out how well I am doing. it does not. work about how well I am doing.

Section Three

Listed below are a number of statements that could be used to describe a job.

You are to indicate whether each statement is anaccurateor aninaccuratedescription of your job you are rating.

Once again, please try to be as objective as you can in deciding how accurately each statement describes the job regardless of your own

feelingsabout that job.

Write a number in the blank beside each statement, based on the following scale: Q-[23-36]. How accurate is the statement in describing the job you are rating?

(1) Very Inaccurate (2) Mostly (3) Slightly (4) Uncertain (5) Slightly (6) Mostly (7) Very Inaccurate Inaccurate Accurate Accurate Accurate

____ Q-23. The job requires me to use a number of complex or high-level skills. ____ Q-24. The job requires a lot of co-operative work with other people.

____ Q-25. The job is arranged so that I do not have the chance to do an entire piece of work from beginning to end. ____ Q-26. Just doing the work required by the job provides many chances for me to figure out how well I am doing. ____ Q-27. The job is quite simple and repetitive.

____ Q-28. The job can be done adequately by a person working alone-without talking or checking with other people.

____ Q-29. The supervisors and co-workers on this job almost never give me any “feedback” about how well I am doing in my job. ____ Q-30. This job is one where a lot of other people can be affected by how well the work gets done.

____ Q-31. The job denies me any chance to use my personal initiative or judgment in carrying out the work. ____ Q-32. Supervisors often let me know how well they think I am performing the job.

____ Q-33. The job provides me with the chance to completely finish the pieces of work I begin. ____ Q-34. The job itself provides very few clues about whether or not I am performing well.

____ Q-35. The job gives me considerable opportunity for independence and freedom in how I do the work. ____ Q-36. The job itself is not very significant or important in the broader scheme of things.

Section Four Overall Job Satisfaction

Q-37. Circle one of the following statements which best tells how well you like your job. Circle the most accurate number.

1 ________ 2 ________ 3 ________ 4 ________ 5 ________ 6 ________ 7 I hate it. I dislike it. I don’t like it. I am indifferent I like it. I am enthusiastic I love it.

to it. about it.

Q-38. Circle one of the following to show how much of the time you feel satisfied with your job.

1 ________ 2 ________ 3 ________ 4 ________ 5 ________ 6 ________ 7 All of the time. Most of the time. A good deal About half of Occasionally. Seldom. Never.

of the time. the time.