The effects of child-bearing on women’s marital status: using

twin births as a natural experiment

a ,

*

b cJoyce P. Jacobsen

, James Wishart Pearce III , Joshua L. Rosenbloom

a

Department of Economics, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT 06459-6067, USA

b

Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

c

University of Kansas and National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, USA

Received 22 January 1999; accepted 18 May 1999

Abstract

We use the exogenous variation in fertility caused by a twin birth to measure the impact of an unplanned child on a woman’s marital status. Contrary to previous research, we find that an unplanned child has little effect on the married mother’s probability of subsequent divorce or remarriage. For unmarried mothers we find that an unplanned child does reduce the likelihood of marriage, but that the magnitude of this effect appears smaller than previous estimates suggest. 2001 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Divorce; Marriage; Fertility

JEL classification: J12

The issue of whether and how the presence or absence of children affects marital formation and dissolution is an interesting one. Economists have advanced a range of views about children’s effects on marital status and have attempted to test these views using recent data. Becker et al. (1977) theorize that the increase in marital-specific capital represented by children would reduce the probability of dissolution. They also argue that children would lower the probability of remarriage because ‘‘they hinder the search for another mate and reduce the gain from remarriage’’ (p. 1157), and present evidence in support of both of their hypotheses. Not only remarriage, but also first marriage may be affected by the presence of children. Bennett et al. (1995) document a negative association between nonmarital childbearing and the subsequent likelihood of first marriage for US

*Corresponding author. Tel.: 11-860-685-2357; fax:11-860-685-2781.

E-mail address: [email protected] (J.P. Jacobsen)

mothers and argue that such childbearing is ‘‘an unexpected and unwanted event.’’ Lillard (1993) finds that second and higher-order children in the current marriage, as well as children from previous relationships, increases the probability of marital dissolution.

Given the apparent import of and public interest in this issue, it is somewhat surprising that a greater volume of work has not been forthcoming on this topic. However, there are two problems involved in measuring the impact of fertility on marital status. To the extent that fertility is affected by measured exogenous variables, such as a woman’s wage, her education, or her husband’s income, failure to account for the endogeneity of fertility may bias estimates of the effect of both fertility and these exogenous variables on marital status. Second, given that there are omitted variables — such as individual heterogeneity in tastes — that likely affect both household formation and fertility decisions, observed fertility will serve as a proxy for the effects of these variables. One solution to these problems is to estimate the determinants of fertility and marital status within a simultaneous equations framework (cf. Lillard, 1993). Unfortunately, implementing this approach is complicated by the difficulty of finding plausible identifying restrictions so that the underlying structural parameters can be recovered, and appropriate data sets are in short supply.

Ideally we would like to be able to observe how probability of marriage, or probability of staying married, would respond to an exogenous variation in the number of children within a family. We cannot, of course, literally perform such an experiment. However, the occurrence of twins in the first birth is an exogenous and unplanned event. Moreover, because the occurrence of twins is randomly distributed with respect to other characteristics that may be related to one’s probability of either becoming or staying married, it is possible to measure the effects of exogenous fertility variations using a simple statistical technique as outlined below.

One obvious limitation of the twins-first methodology is that while it helps to illuminate the marginal effect of an additional child given the presence of one child, it does not allow us to measure the effect of the change from no children to one child. Nonetheless, given that most women do have at least one child during their lives, estimating the marginal effects of an additional child is quite useful, and the effect may be considered a lower bound on the effect of a first child on a marriage, or as a measure of the effect of a second child. Note also that it is necessary to control for parity because the probability of twin births is obviously an increasing function of the number of pregnancies, and the number of pregnancies is likely to be correlated with unobserved preferences concerning family size. Because every woman who wishes to have a nonzero number of children must experience a first pregnancy, we can avoid this selectivity bias by using the occurrence of twins in the first birth.

unplanned births on the labor supply and earnings of married women, but did not examine the impact

1

on marital status.

If the occurrence of twins in the first birth were uncorrelated with any other individual characteristic then we could proceed to estimate the effects of exogenous variation in fertility as the difference in the average level of the outcome variables of interest between the treatment and control groups. Because the probability of twins increases with age, however, and age may be related to marital status, the situation is slightly more complicated. To isolate the pure effects of fertility variations it is thus necessary to control for variations in mothers’ age at first birth. Therefore, the basic statistical framework that we use to estimate the treatment effects is as follows:

2 3

Yi5aj 01a AGEFBj 1 i1a AGEFBj 2 i 1a AGEFBj 3 i 1b TWINSj i1u ,ij (1)

where i indexes individual observations, Y is the outcome variable, AGEFB is mothers’ age at first birth, TWINS is a binary indicator variable equal to zero if the woman had one child in the first birth

2

and equal to one if the woman had two children in the first birth, and uij is a disturbance term.

Because of the independence between the TWINS indicator variable and all other factors influencing the outcome variable Y, we can subsume the influence of these other variables into the disturbance

term. The impact of twins in the first birth is measured by the estimated value of the coefficient b .j

Estimates of Eq. (1) provide a measure of the effect of the discrete event ‘twins in the first birth.’ Our data are drawn from the Public Use Microdata Samples of the 1970 and 1980 Censuses. For 1970 we used the 1-in-100 State, County-Group and Neighborhood Characteristics samples from the

3

5-percent questionnaire, which yields a 3-percent random sample of the population. For 1980 we used all available data: the A, B, and C samples, which provide a 7-percent random sample of the population. The files contain a single record for each individual in each household, which includes information on his or her demographic and economic characteristics. The record also contains information about the individual’s relationship to other members of the household that allows us to match parents with their children.

Using a procedure similar to that outlined by Bronars and Grogger (1994), we first identified all potential mothers and children, and then matched them using the relationship and subfamily status codes. We then eliminated those women who reported an implausibly high or low age at first birth

4

(less than 12 or greater than 55). To be included in our twins-first sample a woman had to: (1) be living with the same number of her own children as she had ever borne; (2) have no children over 18

1

In both papers, women are classified based on their marital status at the time of their first birth in order to avoid potential sample selection problems created by the possible effects of fertility on marital status. Our current work examines that maintained hypothesis. Indeed, if marital status were not affected by twinning, this reduction in the need for past information on marital status would expand the range of datasets and applications to which this method could be applied.

2

Before settling on the specification in Eq. (1) we experimented with a range of polynomial specifications. Inclusion of additional higher-order terms did not affect our estimates of the coefficient on TWINS.

3

We are unable to use the 15-percent questionnaire because it lacks two items, namely age at first marriage and quarter of first marriage. As a result, for these samples we are not able to identify whether the child had been borne before or after the mother’s first marriage.

4

years of age; and (3) have a second child with the same age and calendar quarter of birth as her first

5

child. . As our control group, we selected all women who met the first two criteria, but did not meet the third. For 1970 our sample contains 546,485 observations, of which 3742 had twins in their first birth. For 1980 our sample contains 1,444,495 observations, of which 10,342 are twins-first mothers. These figures imply a probability of twin births of 0.0068 in 1970 and 0.0072 in 1980, which are in

6

the range of probabilities found in other studies. We also consider two subsamples, white mothers and black mothers. The proportion of twins-first mothers is higher among Blacks (0.0086 in 1970 and 0.0085 in 1980) than among Whites (0.0067 in 1970 and 0.0070 in 1980), consistent with the racial differences in the probability of twin births found in other studies.

We estimate two separate sets of probit equations following the specification in (1). In the first set of specifications, the dependent variable indicates whether a woman who was married at the time of her first birth is either (a) currently unmarried or (b) not married currently to the person she was married to at the time of her first birth. In the second set of specifications, the dependent variable indicates whether a woman who was unmarried at the time of her first birth is either (a) currently

7

married or (b) has ever been married. In each case, we identify whether or not a woman was married at the time of her first birth by whether or not she reports an age at first marriage that is younger than the age at which we estimate (based on the reported age of the child) she first gave birth. Current

8

marital status is self-reported, as is whether or not one has been married more than once.

These equations are estimated for all women and separately for white and black mothers, for both 1970 and 1980. We also estimate these equations for all women and separately by whether the age of the first born child (or children) is in the 0 to 3 years range or in the 10 to 13 years range at the time when the sample was collected (April of the Census year). This division allows us to use synthetic cohort analysis to determine whether the effect of twins on marital status changes with the passage of time, since those women whose children were ages 0 to 3 in 1970 belong to the same cohort as women whose children were ages 10 to 13 in 1980.

The relevant results from these estimations are shown in Tables 1 and 2, where the predicted magnitude of the effect on the probability is recorded, along with whether or not it is statistically significant. As shown in Table 1, twin births appear to have at most a small positive effect on the probability of marital dissolution in the 1980 sample, predominantly among women with children ages 10 to 13, with the strongest effect found among black women with children in this age range. In particular, while the twin effect does not appear to increase the probability that one is currently unmarried (and even appears to reduce it among black women in 1970 with children ages 10 to 13), it

5

We exclude mothers living apart from some or all of their children or whose oldest child was over 18 because it is not possible to determine conclusively whether their first birth had been twins. We also exclude mothers who have triplet or higher-order first births (24 cases in 1970 and 82 cases in 1980).

6

These sample sizes and twinning probabilities are different than those reported in our earlier study as we have refined our twin identification procedure so as to exclude more questionable family relationship cases.

7

In runs not shown herein, we also consider different treatments of the state of being widowed, and, for 1970, consider what happens when persons who report ‘‘married, spouse absent’’ are treated as unmarried rather than married. The latter case leads to stronger effects in the same directions as those reported in the tables. When we code widows as currently married rather than as currently unmarried, coefficients are almost identical to those shown in both Tables 1a and 2a.

8

Table 1

Change in marital status probabilities associated with having twins for women who are married at the time of their first birth

Change in probability All White Black

of being: 1970 1980 1970 1980 1970 1980

(a) Currently unmarried

All women 0.002 0.000 0.000 0.005 20.012 0.001

Women with children

ages 0 to 3 0.006 0.001 0.002 20.004 0.045 0.027

Women with children

ages 10 to 13 0.003 0.000 0.001 0.008 20.086* 0.026

(b) Unmarried, or married to a different person

All women 0.000 0.014*** 20.004 0.011*** 0.022 0.022

Women with children

ages 0 to 3 20.001 0.001 20.009 20.004 0.060* 0.021

Women with children

ages 10 to 13 20.003 0.025*** 0.000 0.017* 20.070 0.081**

Sample sizes

All women 495,030 1,227,393 454,540 1,071,117 33,852 86,617

Women with children

ages 0 to 3 111,412 283,361 101,878 247,963 7,815 16,824

Women with children

ages 10 to 13 106,365 260,078 97,636 227,373 7,393 19,751

*Denotes statistical significance at the 90% level, **at the 95% level, ***at the 99% level.

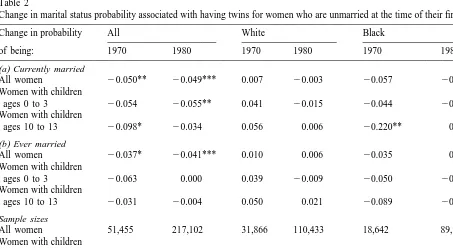

Table 2

Change in marital status probability associated with having twins for women who are unmarried at the time of their first birth

Change in probability All White Black

of being: 1970 1980 1970 1980 1970 1980

(a) Currently married

All women 20.050** 20.049*** 0.007 20.003 20.057 20.044**

Women with children

ages 0 to 3 20.054 20.055** 0.041 20.015 20.044 20.028

Women with children

ages 10 to 13 20.098* 20.034 0.056 0.006 20.220** 0.000

(b) Ever married

All women 20.037* 20.041*** 0.010 0.006 20.035 0.000

Women with children

ages 0 to 3 20.063 0.000 0.039 20.009 20.050 20.020

Women with children

ages 10 to 13 20.031 20.004 0.050 0.021 20.089 20.013

Sample sizes

All women 51,455 217,102 31,866 110,433 18,642 89,911

Women with children

ages 0 to 3 12,750 55,929 7,651 28,747 4,861 22,679

Women with children

ages 10 to 13 10,316 44,704 6,421 22,993 3,697 18,468

does tend to increase the probability that one is not married to the same person as at the time of first birth.

Table 2 indicates that women who were unmarried at the time of their first birth are less likely to become married if they have a twin birth. The magnitude of this effect is nonnegligible (decreasing the probability in the full sample of being currently married by 5 percentage points), and is robust across definitions of marital status, and shows little evidence of weakening in comparing the 1970 and 1980 cohorts. However, the effect in the full sample is driven by the black subsample, as it is not evident in the subsample of whites. The effect of an additional child appears to be more significantly negative in the marriage market for black women.

The results for married women — finding essentially no effect of fertility on marital status — contrast with the findings of Lillard (1993) that additional children increase the probability of marital dissolution and Becker et al. (1977) that additional children reduce the probability of divorce. On the other hand, our results for unwed mothers are consistent with previous research that has found that out-of-wedlock childbearing reduces the probability of subsequent marriage, at least among blacks. However, our results contrast with those of Bronars and Grogger (1994) in that the magnitude of this

9

effect was smaller and more consistent over time than they had found .

Acknowledgements

The data utilized in this paper were made available by the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. The data for the 1970 and 1980 Censuses of Population were originally collected by the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. Neither the collectors of this data nor the Consortium bears any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here.

References

Becker, G.S., Landes, E.M., Michael, R.T., 1977. An economic analysis of marital instability. Journal of Political Economy 85, 1141–1187.

Bennett, N.G., Bloom, D.E., Miller, C.K., 1995. The influence of nonmarital childbearing on the formation of first marriages. Demography 32, 47–62.

Bronars, S.G., Grogger, J., 1994. The economic consequences of unwed motherhood: using twin births as a natural experiment. American Economic Review 84, 1141–1156.

Jacobsen, J.P., Pearce, J.W. P., Rosenbloom, J.L., 1999. The effects of child-bearing on married women’s labor supply and earnings: using twin births as a natural experiment. Journal of Human Resources, forthcoming.

Lillard, L.A., 1993. Simultaneous equations for hazards: marriage duration and fertility timing. Journal of Econometrics 56, 189–217.

9