Journal of Life Sciences

Volume 7, Number 11, November 2013 (Serial Number 67)

David Publishing Company www.davidpublishing.com

Publication Information

Journal of Life Sciences is published monthly in hard copy (ISSN 1934-7391) and online (ISSN 1934-7405) by David Publishing Company located at 240 Nagle Avenue #15C, New York, NY 10034, USA.

Aims and Scope

Journal of Life Sciences, a monthly professional academic journal, covers all sorts of researches on molecular biology, microbiology, botany, zoology, genetics, bioengineering, ecology, cytology, biochemistry, and biophysics, as well as other issues related to life sciences.

Editorial Board Members

Dr. Stefan Hershberger (USA), Dr. Suiyun Chen (China), Prof. Dr. Fadel Djamel (Algeria), Dr. Francisco Torrens (Spain), Dr. Filipa João (Portugal), Dr. Masahiro Yoshida (Japan), Dr. Reyhan Erdogan (Turkey), Dr. Grzegorz Żurek (Poland), Dr. Ali Izadpanah (Canada), Dr. Barbara Wiewióra (Poland), Dr. Amanda de Moraes Narcizo (Brasil), Dr. Marinus Frederik Willem te Pas (The Netherlands), Dr. Anthony Luke Byrne (Australia), Dr. Xingjun Li (China), Dr. Stefania Staibano (Italy), Prof. Dr. Ismail Salih Kakey (Iraq), Hamed Khalilvandi-Behroozyar (Iran).

Manuscripts and correspondence are invited for publication. You can submit your papers via Web Submission, or E-mail to [email protected] or [email protected]. Submission guidelines and Web Submission system are available online at http://www.davidpublishing.org.

Editorial Office

240 Nagle Avenue #15C, New York, NY 10034, USA Tel: 1-323-9847526, 1-302-5977046; Fax: 1-323-9847374

E-mail:[email protected], [email protected]

Copyright©2013 by David Publishing Company and individual contributors. All rights reserved. David Publishing Company holds the exclusive copyright of all the contents of this journal. In accordance with the international convention, no part of this journal may be reproduced or transmitted by any media or publishing organs (including various websites) without the written permission of the copyright holder. Otherwise, any conduct would be considered as the violation of the copyright. The contents of this journal are available for any citation. However, all the citations should be clearly indicated with the title of this journal, serial number and the name of the author.

Abstracted / Indexed in

Database of EBSCO, Massachusetts, USA Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS), USA

Database of Cambridge Science Abstracts (CSA), USA Database of Hein Online, New York, USA

Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory, USA Universe Digital Library S/B, Proquest

Chinese Database of CEPS, American Federal Computer Library center (OCLC), USA China National Knowledge Infrastructure, CNKI, China

Chinese Scientific Journals Database, VIP Corporation, Chongqing, China Index Copernicus, Index Copernicus International S.A., Poland

Google Scholar (scholar.google.com)

Subscription Information

Price (per year): Print $420, Online $300, Print and Online $560.

David Publishing Company

240 Nagle Avenue #15C, New York, NY 10034, USA Tel: 1-323-9847526, 1-302-5977046; Fax: 1-323-9847374 E-mail: [email protected]

J LS

Journal of Life Sciences

Volume 7, Number 11, November 2013 (Serial Number 67)

Contents

Medical Sciences

1123 Pharmacokinetics Evaluation of Nimotuzumab in Combination with Doxorubicin and

Cyclophosphamide in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer

Leyanis Rodríguez-Vera, Eduardo Fernández-Sánchez, Jorge L. Soriano, Noide Batista, Maité Lima, Joaquín Gonzalez, Robin Garcia, Carmen Viada, Concepción Peraire, Helena Colom and Mayra

Ramos-Suzarte

1134 Investigation on the Perceptions of Living Donors regarding Spousal Renal Donor

Transplantation

Miyako Takagi

1143 Lyme Disease in Iraq: First Detection of IgM Antibodies to Borreliaburgdorferi in Human Sera

Khalis A. Hamad Ameen, Basima A. Abdullah and Riyad A. Abdul-Razaq

1147 Missed Opportunities for Intermittent Preventive Treatment [IPTp] among Pregnant Women, in a

Secondary Health Facility, Cross River State, Nigeria

Olaide Bamidele Edet, Edet Etim Edet, Patience Edoho Samson-Akpan and Idang Neji Ojong

1159 Statistics of Acute Aluminium Phosphide Poisoning in Fez, Morocco

Boukatta Brahim, El Bouazzaoui Abderrahim, Houari Nawfal, Achour Sanae, Sbai Hicham and Kanjaa Nabil

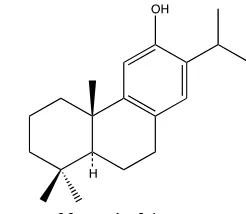

1165 Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Ferruginol from Prumnupitysandina

Maité Rodríguez-Díaz, Carlos Areche and Carla Delporte

Botany and Zoology

1170 Effect of Water Deficit Stress on Isotope 15N Uptake and Nitrogen Metabolism of Newhall Orange

and Yamasitaka Mandarin Seedling

1179 Influence of Biopreparations on Maiden Growth of Sour Cherry (Prunus cerasus L.) in Organic

Nursery – Preliminary Results

Zygmunt Stanisław Grzyb, Wojciech Piotrowski, Lidia Sas Paszt and Paweł Bielicki

1185 Ecological Safe Growing of Chickpea in the Area of Steppe of Ukraine

Didovych Svitlana

1191 Vitamin B6 and Lipid Contents in Engraulis japonica Specifically Caught for Production of

Japanese Soup Stock

Mitsuharu Yagi and Hisaaki Takayama

1196 Distribution and Relative Abundance of the Tursiops truncatus in Lebanese Marine Waters

(Eastern Mediterranean)

Gaby Khalaf, Milad Fakhri, Christine Ohanian, Carine Abi-Ghanem and Lea David

1204 Owls and Mobbing Behavior: Anecdotal Observations

Filipe Cristovão Ribeiro da Cunha, Gustav Valentin Antunes Specht and Franck Rocha Brites

Environmental Sciences

1209 Short Term Effects of Olive Mill Waste Water on Soil Chemical Properties under Semi Arid

Mediterranean Conditions

November 2013, Vol. 7, No. 11, pp. 1123-1133 Journal of Life Sciences, ISSN 1934-7391, USA

Pharmacokinetics Evaluation of Nimotuzumab in

Combination with Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide

in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer

Leyanis Rodríguez-Vera1, Eduardo Fernández-Sánchez2, Jorge L. Soriano3, Noide Batista3, Maité Lima3, Joaquín Gonzalez3, Robin Garcia3, Carmen Viada4, Concepción Peraire5, HelenaColom5 and Mayra Ramos-Suzarte4

1. Laboratory of Pharmacokinetic, Department of Pharmacology & Toxicology, Institute of Pharmacy & Foods, 222 St. and 23

Avenue, La Coronela, La Lisa, University of Havana, Havana, CP 13600, Cuba

2. Center for Research and Biological Evaluation, Institute of Pharmacy & Foods, 222 St. and 23 Avenue, La Coronela, La Lisa,

University of Havana, Havana, CP 13600, Cuba

3. Hermanos Ameijeiras Hospital, San Lázaro Avenue and Street Belascoain, Havana Center, Havana, Cuba

4. Center of Molecular Immunology, Street 216 and 15, Atabey, Playa, Havana, Cuba

5. Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Technology Department, School of Pharmacy, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Received: June 21, 2013 / Accepted: August 15, 2013 / Published: November 30, 2013.

Abstract: EGFr (Epidermal growth factor receptor) overexpression has been detected in many tumors of epithelial origin, specifically in breast cancer and it is often associated with tumor growth advantages and poor prognosis. The nimotuzumab is a genetically engineered humanized MAb (monoclonal antibody) that recognizes an epitope located in the extracellular domain of human EGFr. The aim of this study was to assess the pharmacokinetics of nimotuzumab in patients with locally advanced breast cancer who are receiving neoadyuvant therapy combined with the AC chemotherapy regimen (i.e., 60 mg/m2 of Doxorubicin and 600 mg/m2 of Cyclophosphamide in 4 cycles every 21 days). A single center, non-controlled, open Phase I clinical trial, with

histopathological diagnosis of locally advanced stage III breast cancer, was conducted in 12 female patients. Three patients were enrolled at each of the following fixed dose levels: 50, 100, 200 and 400 mg/week. Multiple intermittent short-term intravenous infusions of nimotuzumab were administered weekly, except on weeks 1 and 10, when blood samples were drawn for pharmacokinetic assessments. Nimotuzumab showed dose-dependent kinetics. No anti-idiotypic response against nimotuzumab was detected in blood samples of participants. There was not interaction between the administration of nimotuzumab and chemotherapy at the dose levels studied. The optimal biological doses ranging were estimated to be 200 mg/weekly to 400 mg/weekly.

Key words: Breast cancer, epidermal growth factor receptor, monoclonal antibody, nimotuzumab, pharmacokinetics.

1. Introduction

The HER (human epidermal growth factor receptor) family consists of four tyrosine kinase receptors:

HER1/ErbB-1 (epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFr)), HER2/ErbB-2/ Neu, HER3/ErbB-3 and HER4/ErbB-4 [1]. These receptors are highly

expressed in many solid tumor types, including

Corresponding author: Leyanis Rodriguez-Vera, M.Sc., auxiliar professor, research field: pharmacokinetics. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected].

breast [2], lung [3], ovarian [4], colorectal [5] and

prostate [6]. They also play an important role in the proliferation, differentiation, motility, adhesion,

protection from apoptosis and transformation of tumor cells [1, 7, 8].

Several strategies have been developed to disrupt

the EGFr-associated signal transduction cascade. The main therapeutic approaches include MAb

(monoclonal antibodies) [8, 9] directed against the extracellular binding domain of the receptor and small

D

D A V ID P U B L IS H IN G

Pharmacokinetics Evaluation of Nimotuzumab in Combination with Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer

1124

molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors [10], which act by

interfering with ATP binding to the receptor.

Nimotuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody

that targets the epidermal growth factor receptor. Nimotuzumab, also known as h-R3, is an anti-EGFr MAb developed at the Center of Molecular

Immunology in Havana, Cuba. Originally isolated as a murine IgG2a anti-body, known as ior egf/r3, the

MAb was humanized to reduce its immunogenicity and to slow clearance from the body by grafting the CDRs (complementarily-determining regions) of R3

to a human IgG1 gene [11]. In the process, the anti-body’s variable fraction was further modified by

recreating three specific murine amino acids (Ser 75, Thr 76, Thr 93) in order to preserve the new MAb’s anti-EGFr activity [11].

Nimotuzumab is registered as a first-line treatment for head and neck cancer in combination with

radiotherapy [12]. Nimotuzumab is currently being evaluated in several clinical trials: two Phase III trials as a first-line treatment for pediatric pontine and adult

glioma, a Phase II/III trial as a treatment for pancreatic cancer, the phase II study in colorectal cancer reported

in this release, phase I in tumors from epithelial origen. Some of those results are published already [13-17] and some of them are ongoing now.

The objective of this study was to characterize the pharmacokinetic profile of nimotuzumab when given

in combination with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide in patients treated with cumulative dose escalation regimen for each dose and each dose

level administered, and to determine possible dose-dependent changes in the pharmacokinetics of

nimotuzumab in patients treated with the multiple cumulative dose escalation regimen.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Patient Eligibility

Patients with histologically confirmed breast locally advanced-stage epithelial tumors that were not

amenable to receive any further therapy and who had

finished their last treatment at least 4 weeks before

were included in the trial. Other selection criteria were a good performance status, normal hematological

conditions, as well as normal hepatic and renal functions. The most important exclusion criteria consisted of previous treatments with murine

anti-EGFr antibodies, pregnancy or lactation, serious chronic diseases, and active infections. All patients

signed a written consent form before their inclusion in the clinical trial.

2.2 Study Design and Treatment Procedure

The study was designed as a clinical trial phase I, monocenter from scale up, clinical register number RPCE00000057 [18]. Twelve patients were included

in four treatment cohorts, receiving multiple administrations of the monoclonal antibody. Three

patients were enrolled in each of the following fixed dose levels: 50, 100, 200 and 400 mg/week. Nimotuzumab was administered weekly during 2.5

months by intravenous infusion of 0.5 hours. Subjects were closely monitored during the trial and finished

the administration of nimotuzumab. The HAMA (human anti-mouse antibody) response was evaluated. Patients also received a combination of 60 mg/m2 of

Doxorubicin and 600 mg/m2 of Cyclophosphamide in 4 cycles every 21 days intercalated with MAb. The

trial was conducted under the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki with the approval of the corresponding Ethics Review Committee for human

subjects protection in clinical trials at the Hermanos Ameijeiras Hospital and the State’s Center for Drug

Quality Control (CECMED), the National Regulatory Agency.

2.3 Pharmacokinetics Assays

2.3.1 Drug Concentration Measurements

Serum samples were collected at week 1 and 10th immediately before IV infusion and 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 7

days following the end of infusion, and before administration at 7th day and on every week before

Pharmacokinetics Evaluation of Nimotuzumab in Combination with Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer

1125

Additional samples were collected after 10th

administration before drug administration on 10th doses and 1, 6, 14, 20 and 26 days after the end of

infusion. Samples were allowed to clot and then centrifuged. Serum was collected and stored at -20 °C. Serum concentrations of nimotuzumab were

determined by a receptor-binding, ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), using the

antigen HER 1, recombinant extracellular of EGFr domain to capture nimotuzumab from serum samples. Bound nimotuzumab was detected with sheep

antihuman IgG gamma chain specific-alkaline phosphate (Sigma Chemical, A-3188, USA), and

para-nitro-phenyl-phosphate diluted in diethanolamine was used as the substrate for color development to quantify serum nimotuzumab against a standard curve.

Absorbance was read at 405 nm. The LLOQ (lower limit of quantification) of nimotuzumab in human

serum was 7.5 ng/mL.

2.3.2 Pharmacokinetic Analysis

The individual concentration vs time profiles

obtained after the first (day 1) and the tenth IV infusions (day 10) were analyzed by the NCA

(non-compartmental analysis) using a combined linear/log linear trapezoidal rule approach. Pharmacokinetic calculations were performed using

WinNonlin®, Pharsight® Co., 2006, ver. 5.3.

A time zero value was considered for extrapolation

purposes. The linear trapezoidal rule was used up to peak level, after which the logarithmic trapezoidal rule was applied. Lambda z is a first-order rate constant

associated with the terminal (log linear) segment of the curve. It was estimated by linear regression of the

terminal data points. The largest adjusted regression was selected in order to estimate lambda z, with a caveat: if the adjustment did not improve, it was rather

that within 0.0001 of the largest value the regression with larger number of points was used. For each

patient in each dose level, metrics typically reported in pharmacokinetic studies were tabulated. Parameters extrapolated to infinity, using the moments of the

curve, such as AUC (the area under the disposition

curve), AUMC (the area under the first moment of the disposition curve) and MRT (mean residence time)

were computed based on the last predicted level, where the predicted value is based on the linear regression performed to estimate terminal lambda

first-order rate constant. Computing these parameters based on the last observed level was discouraged in

order to avoid larger estimation errors.

The relationships between estimated pharmacokinetic parameters and administered weekly doses were

assessed in order to determine the threshold level at which a dose proportionality is lacked.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses (i.e., means,

standard deviations) were performed to summarize the pharmacokinetic characteristics of participants in this

study at each administered dose. Statistical comparison between the 1st and 10th administration in every dose level (i.e., 50, 100, 200 and 400 mg/week)

was performed by a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. All statistical analyses were performed using the

SPSS software, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, 2006). Statistical significance was set at 5% (P < 0.05), with a 95% confidence interval.

2.5 Anti-Idiotypic Response

The anti-idiotypic response was evaluated pre-treatment, at day 7th and then weekly up to 2 months. The HAMA (human anti mouse antibody)

response was considered to be positive when post-treatment value/pre-treatment ratio was higher

than 2. It was determined by an ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), using the murine ior egf/r3 idiotype (CIMAB, D-0201). Briefly,

5 µg/mL of ior egf/r3 concentration was used as capture system overnight at 4 °C. Plates were washed

Pharmacokinetics Evaluation of Nimotuzumab in Combination with Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer

1126

the antihuman IgG γ chain specific-alkaline phosphate

conjugated and anti human IgM µ chain specific–alkaline phosphate conjugated (Sigma

Chemical, A-3188 and A-9794, USA, respectively). After washing, then a chromogen solution (para-nitro-phenil-phosphate 1 mg/mL in

diethanolamide buffer pH 9.8) was added and incubated by 30 min at room temperature. Plates were

measured on an ELISA reader at 405 nm (Organon Teknika, Netherlans) [19].

3. Results and Analysis

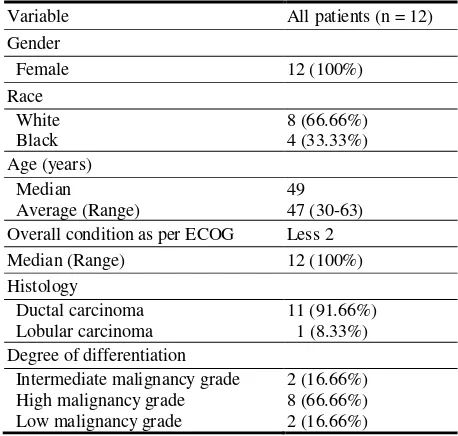

3.1 Patient Characteristics

Twelve female patients, mean age 47 (30-63)

years-old, with a histologically confirmed, advanced locally breast tumor were enrolled in the study.

Participants were recruited from the medical facilities at the Hermanos Ameijeiras Hospital in La Habana, Cuba. Patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

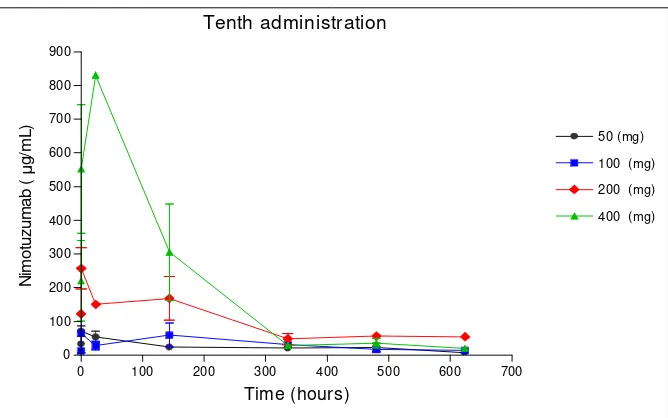

3.2 Pharmacokinetics

The corresponding serum drug concentrations-time

curves for the 1st and 10th administrations of nimotuzumab are depicted in Figs. 1 and 2,

respectively, whereas, the means and standard

deviations of the pharmacokinetic parameters for the

first and tenth administration at each dose level are

shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

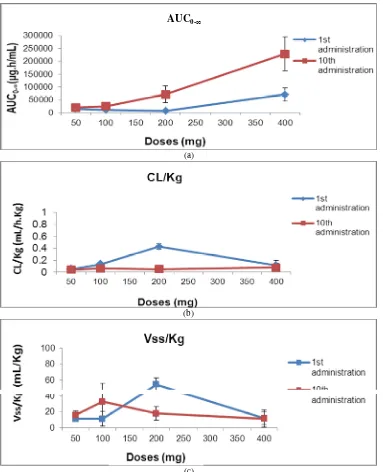

As expected, Fig. 3 shows a typical accumulative

pattern after multiple doses of nimotuzumab given intravenously in each participant by intermittent

short-term infusions. Besides, that non-proportional,

greater than anticipated increments in the areas under

the serum drug concentration-versus-time curves are

observed across the dose range, which reveals a

non-linear behaviour.

The mean AUC0-∞ values increased from 15601.75 to 71405.05 µg·h/mL after the 1st administrations of 50 and 400 mg/week, respectively, and from 20677.29 to 228797.09 µg·h/mL after the corresponding 10th

administrations of the same dose levels, which

indicate lack of dose proportionality (Fig. 4a).

The average value for the elimination half-lives (t½) of the humanized MAb in these patients was

relatively long, and varies from 150.23 hours to 78.02 hours after the first administration of either 50 mg/week or 400 mg/week. Accordingly, the average

drug CL (clearance) was relatively slow for all participants. These body weight-normalized CL values

did not differ significantly along the dose range (i.e., oscillating from 0.05 mL/h·kg to 0.11 mL/h·kg), except for the 200 mg/week level that increases

abruptly up to 0.43 mL/h·kg during the first administration. However, a decrease in the total

clearance is observed after the 10th administration probably due to a saturation effect (Fig. 4b).

The average volume of distribution at steady-state

(Vss) was relatively small, suggesting a limited distribution out of the blood compartment or a

significant binding to plasma/blood components. This parameter tends to increase after the 1st administration of the 200 mg/week dose level; whereas, these values

fluctuated after the 10th administration (Fig. 4c). When the pharmacokinetic parameters were

compared across the different dose levels, there were found significant differences for AUC0-∞ of 0.019 and 0.033, Cmax of 0.043 and 0.029 for 1st and 10th

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the patients.

Variable All patients (n = 12)

Pharmacokinetics Evaluation of Nimotuzumab in Combination with Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer

1127

administration respectively, and CL during the 1st

administration (0.031), but not for the 10th administration indicating the saturation levels of the

nimotuzumab followed doses multiple regimen (Tables 2, 3 and Fig. 4).

Table 4 presents the estimated average drug

concentrations at steady state (Cssaverage) and the peak and trough steady-state concentrations of nimotuzumab

for patients in the four different dose levels. The Css average values increase disproportionately to the dose levels. Indeed, it is observed that at the dose of 200

mg/week the Css average is almost three times that at

100 mg/week, which could indicate that a dose-dependent non-linearity process is involved in the

elimination of nimotuzumab.

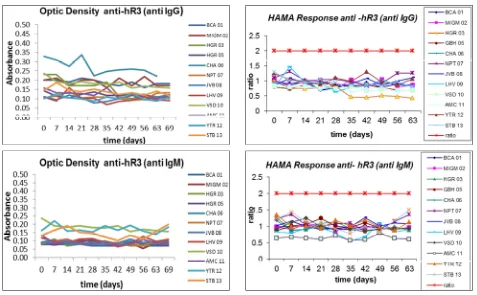

3.3 Anti-Idiotypic Response

After the evaluation of the human response against the murine portion of the MAb (using an ELISA test),

it was verified that the optical density values were in all cases very similar to the pre-treatment values for the IgM and IgG responses (Fig. 5).

First administration

0 50 100 150 200

0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900

50 (mg)

100 (mg)

200 (mg)

400 (mg)

Time (hours)

N

imo

tu

zu

m

a

b

(µ

g

/m

L)

Fig. 1 Nimotuzumab mean serum concentration–time profiles in first administration for four doses level.

Tenth administration

0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700

0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900

50 (mg)

100 (mg)

200 (mg)

400 (mg)

Time (hours)

N

im

o

tuz

u

m

a

b

(µ

g

/m

L)

Fig. 2 Nimotuzumab mean serum concentrations–time profiles in tenth administration for the 50, 100, 200 and 400 mg/week

doses.

Pharmacokinetics Evaluation of Nimotuzumab in Combination with Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer

1128

Table 2 Nimotuzumab pharmacokinetic parameters for the 1st administration. Non-Compartmental Analysis.

Dose (mg) No. of patients AUC0-∞ (µg·h/mL) Cmax (µg/mL) t ½ (h) CL/kg (mL/h·kg) Vss/kg (mL/kg)

50 3 15601.65 ± 5152.58 79.96 ± 22.16 150.23 ± 69.91 0.05 ± 0.01 11.24 ± 2.6

100 3 11186.87 ± 2105.47 169.67 ± 99.52 63.72 ± 46.32 0.13 ± 0.03 11.25 ± 9.4

200 3 7879.41 ± 448.75 59.59 ± 4.32 88.66 ± 9.39 0.43 ± 0.04 54.30 ± 8.4

400 3 71405.05 ± 37116.59 499.53 ± 27.58 78.02 ± 8.78 0.11 ± 0.08 11.93 ± 7.5

(P) 0.019* 0.043* 0.154 0.031* 0.082

Values are mean ± SD. AUC0-∞, area under plasma drug concentration-time curve from zero to infinity; Cmax, maximum level of

concentration; t ½, half-life; CL/kg, clearance corrected per kg of weight; Vss/kg, volume of distribution at steady-state corrected per kg of weight. P: Statistical significance < 0.05; IC95: Kruskal-Wallis test.

Table 3 Nimotuzumab pharmacokinetic parameters 10th administration. Non-Compartmental Analysis.

Dose (mg) No. of patients AUC0-∞(h·µg/ mL) Cmax (µg/mL) t ½ (h) CL/kg (mL/h·kg) Vss/kg (mL/kg)

50 3 20677.29± 6881.28 73.98 ± 11.72 274.20 ± 66.59 0.04 ± 0.02 16.00 ± 4.94

100 3 25489.90 ± 10656.01 64.58 ± 57.06 355.62 ± 145.01 0.06 ± 0.03 33.07 ± 22.7

200 3 71765.77 ± 35480.68 257.63 ± 106.9 218.62 ± 5.08 0.05 ± 0.02 17.91 ± 8.38

400 3 228797.09 ± 228232.98 582.4 ± 325.31 105.76 ± 19.76 0.08 ± 0.07 11.47 ± 10.7

(P) 0.033* 0.029* 0.082 0.705 0.459

Values are mean ± SD. AUC0-∞, area under plasma drug concentration-time curve from zero to infinity; Cmax, maximum level of

concentration; t ½, half-life; CL/kg, clearance corrected per kg of weight; Vss/kg, volume of distribution at steady-state corrected per kg of weight. P: Statistical significance < 0.05, IC95: Kruskal-Wallis test.

Fig. 3 Nimotuzumab concentration-time data in multiple administration regime. Graph shows the observed nimotuzumab concentrations represented as symbols and color lines with black rhombus, blue square, red rhombus and green triangle for the 50, 100, 200 and 400 mg/week doses, respectively.

Once the post-treatment/pre-treatment ratio of ≥ 2 was established as the cohort value to consider if a

patient would have a positive anti-idiotypical response, it was confirmed that none of the patients treated had a higher value. Therefore, it can be considered that with

10 doses of the MAb, even after the single dose was

increased to 400 mg/week and the total dose being 4000 mg, the patients did not develop a response

against the murine portion of the nimotuzumab, which shows low immunogenicity of this MAb due to its humanized characteristics. See Fig. 5 for anti-idiotypic

Pharmacokinetics Evaluation of Nimotuzumab in Combination with Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer

1129

(a)

(b)

(c)

Fig. 4 a, Area under the serum concentration time curve from time zero to infinity (AUC0-∞) as a function of the

nimotuzumab dose from 50 to 400 mg/week (n = 12); b, CL/kg (Clearance corrected per kg of weight) as a function of the nimotuzumab dose from 50 to 400 mg/week (n = 12); c, Vss/kg (volume of distribution at steady-state corrected per kg of weight) as a function of the nimotuzumab dose from 50 to 400 mg/week (n = 12).

Table 4 Estimates average concentration in the steady state and maximal and minimal concentration in the steady state of Nimotuzumab.

Dose (mg) No. of patients Cssaverage C

ss

max C

ss min

50 3 122.53 ± 38.27 149.39 ± 44.0 98.76 ± 33.02

100 3 160.57 ± 63.51 196.26 ± 93.75 129.93 ± 41.83

200 3 465.6 ± 290.37 592.53 ± 369.52 357.89 ± 223.19

400 3 864.72 ± 550.40 1379.27 ± 869.70 498.67 ± 333.47

Values are mean ± SD. Cssaverage: estimates average concentration in the steady state; Cssmax: maximum concentration in the steady

state; Cssmin: minimum concentration in the steady state.

AUC0-∞

Pharmacokinetics Evaluation of Nimotuzumab in Combination with Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer

1130

Fig. 5 Anti-idiotypic response in treated patients (n = 12).

4. Discussion

Despite the advances in surgery, radiation and

chemotherapy, advanced epithelial-derived cancer

largely represent an unsolved problem. Today,

biologic therapy emerges as the fourth modality for

cancer management, being a very attractive option

taking into consideration its specificity and low

toxicity [20]. Passive immunotherapy against solid

tumors with naked antibodies has recently

demonstrated efficacy in the clinical setting [20].

EGFr is a very attractive target for immunotherapy

since EGFr driven autocrine growth pathway has been

implicated in the development and progression of the

majority of human epithelial cancers [21].

Breast cancer shows an increase in the EGFr

expression, and it has been reported that 14-91% of tumours over-express this receptor [2]. The action

of nimotuzumab plus AC chemotherapy was evaluated in this study. Given the fact that nimotuzumab competitively inhibits the binding of the

EGF ligand to the extracellular domain of the HER-1

protein, leading to a further inhibition of the homodimerization or heterodimerization of this

receptor and subsequent autophosphorylation of its tyrosine residues, the activation of the different ligand-induced signal transduction pathways

(Ras-Raf-MEK-MAPKS cascade; PI3K) will be inhibited as well [10]. The aim was to assess the

pharmacokinetic of nimotuzumab in patients with locally advanced breast cancer who are receiving neoadyuvant therapy combined with the AC

chemotherapy regimen. Moreover, AC acts directly on the nucleus of the cells that are in turnover phase and

therefore the replication of the DNA would be inhibited and the combination of both therapeutic agents potentiates the antitumour effect (Fig. 3).

Cetuximab (chimeric monoclonal anti-EGFR antibody) combined with antineoplastic agents

showed a synergistic effect and an increase in the anti-tumour efficacy in metastatic colorectal cancer and head and neck tumors [22]. It is suggested that the

Pharmacokinetics Evaluation of Nimotuzumab in Combination with Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer

1131

paclitaxel and irinotecan [22].

Trastuzumab, a humanized MAb that recognizes the HER-2 receptor (a member of the EGFr family) was

licensed in 1997 for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer combined with paclitaxel [23]. Different clinical studies have led to an extension of this therapy

to the earlier stages of breast cancer, based on the fact that this molecule blocks HER2, which is part of the

EGFr group [23].

Nimotuzumab was combined with an anthracycline based chemotherapy (i.e., doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide)

in the phase I clinical study. This new therapeutic regimen for nimotuzumab included an increase in the

number of administrations up to ten doses. The first dose of this MAb was administered before starting chemotherapy in order to induce an effect of

nimotuzumab on a HER 1 over-expressing tumour without any interference of the cytostatic therapy as

well as to assess the pharmacokinetics of nimotuzumab in this type of patient and therapy.

To our knowledge, this is the first time a

pharmacokinetic report on Nimotuzumab combined with chemotherapy after multiple dosing in breast

cancer patients is written. The pharmacokinetic analyses for nimotuzumab showed a lack of dose proportionality within the dose range of 50-400 mg

weekly, as suggested by a disproportional increase of AUC0-∞ over the entire dose range and dose-dependent clearance and apparent distribution volumes. This is typically the non-linear pharmacokinetic behavior that has been early reported for other monoclonal

antibodies in humans [13, 22, 23].

Clearance variations observed over the entire dose range and the resulting dose-dependency pattern in

this study was opposed to some previous reports for this (i.e., I125-labelled nimotuzumab) and other MAbs

[13, 22, 23]. However, the results of the current study

correlate well with an early report from a

pharmacokinetic study of nimotuzumab in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer

that was conducted in Germany [24].

Although no statistically significant differences are

found between clearance values of this MAb after the

10th administration (Table 3), results after the 1st administration (Table 2) showed a slight but

significant variation of the MAb clearance in these

patients (P = 0.03), with total clearance rising steadily up to the dose of 200 mg/week and then a sudden

decrease is observed at the 400 mg/week dose. Since there is a turning point in the total systemic clearance

of nimotuzumab at the interval of 200 mg/week to 400

mg/week, we consider this dose range as one representing a saturation region for its biological

targets or reservoirs in the body and thus a potential optimal dose level. An explanation for the clearance

variations observed in the dose range (i.e., 50-200 mg/week) tested in this study cohort could be found in

the additive nature of this parameter: CL Total =

specific CL + non-specific CL [25].

We speculate that the total systemic clearance

reduction at the very high dose is probably a consequence of the saturation of the membrane-bound EGFr-mediated elimination pathway (i.e., a specific

clearance routes with limited capacity such as receptor-mediated endocytosis). The impact of the

antigen/target on the non-linear pharmacokinetics of MAbs is generally characterized by faster clearance rates at a lower dose range; whereas, the clearance

decreases at the highest dose of the antibody due to a saturation of the specific antigen/target-mediated

clearance process. However, non-specific processes (e.g., RES (reticule-endothelial system)-mediated events) are likely favoured at increasing doses [25] and,

therefore, they might account for most of the observed changes in clearance at the studied dose range.

On the other hand, the systemic clearance of MAbs in cancer patients could be modified by several factors including soluble antigen in circulation and

immunogenicity [25]. For instance, previous reports from a phase I clinical trial study revealed an increased

Pharmacokinetics Evaluation of Nimotuzumab in Combination with Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer

1132

nimotuzumab given to 12 patients with advanced

epithelial-derived cancer, Crombet et al. observed that 3 patients with ductal infiltrating breast carcinomas

had positive serum elevation of shedding EGFr [13]. Since we have patients with advanced breast cancer in our study cohort, we believe that a fraction of the

nimotuzumab in the bloodstream is bound to these circulating antigens, and that nonspecific RES

clearance process [25] is also contributing to the increasing clearance value observed across the dose ranges from (50 mg/week to 200 mg/week). In fact, it

seems to be that EGFr shedding correlated with nimotuzumab clearance after the 1st administration.

Increased serum ECD (Extracellular Domain) levels of EGFr have been early reported in patients with

cancers that are known to overexpress Her 1 or Her 2

protein [23, 26, 27]. In a study with patients suffering from metastatic breast cancer who were receiving 2

mg/kg of trastuzumab, a patient with high circulating

shed antigens had a similar reduction of serum concentrations to that observed in our study after

giving the dose of 200 mg/week during the 1st administration [23]. This report suggests that high

circulating antigens will decrease the elimination half-life and the trough serum concentrations of

humanized MAb against HER2 product [23]. Besides, high serum concentrations of HER 2 ECD have been

correlated with higher relapse rates, and elevated

pretreatment levels of HER2 ECD have also been associated with poor clinical response to hormone

therapy and chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer patients [27]. Therefore, monitoring of circulating

shed antigen level is considered to be essential in

trastuzumab therapy [27].

Notably, these shed EGFr molecules do not seem to

significantly interfere with the clearance of

nimotuzumab after the 10th administration cycle. It might be due to a depletion of circulating antigens

after multiple administrations of the MAb.

The human anti-murine antibody response does not

alter the clearance of nimotuzumab. The lack of

anti-idiotypic response in this study emphasizes the

relatively non-immunogenicity of this humanized MAb following repeated administrations of nimotuzumab the

doses. In previous studies by Crombet et al., the anti-idiotypic antibodies were not detected in any patient after IV infusions of nimotuzumab at several

dose levels, with measurements performed up to 6 months after treatment [13].

A limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size to perform the corresponding statistical analyses with power enough to draw valid conclusions.

Accordingly, results and recommendations should be observed with cautions.

5. Conclusion

Nimotuzumab showed a non-linear dose-dependent

pharmacokinetics. No interactions between the administration of nimotuzumab and chemotherapy

(doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide) were observed at the studied dose levels. No anti-idiotypic response to nimotuzumab was found in the patients enrolled in

this study. Monitoring of circulating shed EGFr level must be considered in nimotuzumab therapy for breast

cancer. Based on our findings, we preliminarily recommend the 200 mg/week to 400 mg/week infusion dose range as the OBD (Optimal Biological

Dose) range to be proposed for further human studies of this MAb.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ph.D. Jorge Ducongé for their

helpful comments and M.Sc. Idania Suárez for the English correction of the manuscript.

References

[1] Y. Yarden, M.X. Sliwkowski, Untangling the ErbB signalling network, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2 (2001) 127-137.

[2] C.J. Witton, J.R. Reeves, J.J. Going, T.G. Cooke, J.M. Bartlett, Expression of the HER1-4 family of receptor

tyrosine kinases in breast cancer, J Pathol 200 (2003) 290-297.

Pharmacokinetics Evaluation of Nimotuzumab in Combination with Doxorubicin and Cyclophosphamide in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer

1133

Lafitte, C. Mascauxl, The role of EGF-R expression on patient survival in lung cancer: A systematic review with meta-analysis, Eur Respir J 20 (2002) 975-981.

[4] M. Campiglio, S. Ali, P.G. Knyazev, A. Ullrich, Characteristics of EGFR family-mediated HRG signals in human ovarian cancer, J Cell Biochem 73 (1999) Pathol 29 (1998) 771-777.

[6] D.B. Agus, R.W. Akita, W.D. Fox, J.A. Lofgren, B. Higgins, K.L. Maiese, A potential role for activated HER-2 in prostate cancer, Semin. Oncol. 27 (2000) 76-83, discussion 92-100. factor receptor biology (IMC-C225), Curr Opin Oncol 13 (2001) 506-513.

[10] F. Ciardiello, G. Tortora, A novel approach in the treatment of cancer: Targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor, Clin Cancer Res 7 (2001) 2958-2970. [11] C. Mateo, E. Moreno, K. Amour, Humanization of a

mouse monoclonal antibody that blocks the epidermal growth factor receptor: Recovery of antagonistic activity, Immunotechnology 3 (1) (1997) 71-81.

[12] T. Crombet, M. Osorio, T. Cruzl, Use of the humanized anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody h-R3 in combination with radiotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer patients, J Clin Oncol 22 (9) (2004) 1646-1654.

[13] T. Crombet, L. Torres, E. Neninger, Pharmacological evaluation of humanized anti-epidermal growth factor receptor, monoclonal antibody h-R3, in patients with advanced epithelial-derived cancer, J. Immunother 26 (2) (2003) 139-148.

[14] F. Rojo, E. Gracias, N. Villena, Pharmacodynamic study of nimotuzumab, an anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) monoclonal antibody (MAb), in patients with unresectable squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN): A SENDO foundation study, J. Clin. Oncol. 26 (Suppl.) (2008) 6070.

[15] B.K. Reddy, M. Vidyasagar, K. Shenoy, BIOMAb

EGFRTM (Nimotuzumab/h-r3) in combination with standard of care in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck (SCCHN), Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 69 (3) (2007) S450.

[16] A.M. Brade, J. Magalhaes, L. Siu, A single agent, phase I pharmacodynamic study of nimotuzumab (TheraCIM-h-R3) in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors, J. Clin. Oncol. 25 (18S, Part 1, Suppl.) (2007) 14030.

[17] D.G. Bebb, A.M. Brade, C. Smithl, Preliminary results of an escalating dose phase I clinical trial of the anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody nimotuzumab in combination with external radiotherapy in patients diagnosed with stage IIb, III or IV non-small cell lung cancer unsuitable for radical therapy, J. Clin. Oncol. 26 (15) (2008) 3037.

[18] The Cuban Clinical Trials Website, Feb. 15th, 2013, http://www.registroclinico.sld.cu/trials/RPCE00000057/. [19] M.E. Arteaga, N. Ledón, A. Casacó, Systemic and skin

toxicity in Cercopithecus aethiops sabaeus monkeys treated during 26 weeks with a high Intravenous Dose of the Anti Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibody Nimotuzumab, Cancer Biol Ther 6 (9) (2007) Aug. 13.

[20] S. Rosenberg, Principles of cancer management: Biologic therapy, in: V. De Vita, S. Hellman, S. Rosemberg (Eds.), Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology, 6th ed., Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA, 2001, p. 307.

[21] F. Ciardiello, Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors as anticancer agents, Drugs 60 (suppl 1) (25) (2000) 41-42.

[22] D.A. Frieze, J.S. McCune, Current status of Cetuximab for the treatment of patients with solid tumors, Ann Pharmacother 40 (2006) 241-250.

[23] Y. Tokuda, T. Watanabe T.Y. Omuro, Dose escalation and pharmacokinetic study of a humanized anti-Her 2

monoclonal antibody in patients with her

2/neu-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer, British Journal of Cancer 31 (8) (1999) 1419-1425.

[24] D. Strumberg, B. Schultheis, M.E. Scheulen, Safety, efficacy and pharmacokinetics of nimotuzumab, a humanized monoclonal anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFr) antibody, in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer, International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 48 (7) (2010) 473-475.

[25] M.A. Tabrizi, C.L. Tseng, L.K. Roskos, Elimination mechanisms of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies, Drug Discovery Today 11 (1-2) (2006) 81-88.

[26] M.J. Oh, J.H. Choi, I.H. Kim, Detection of epidermal growth factor receptor in the serum of patients with cervical carcinoma, Clin Cancer Res 6 (2000) 4760-4763. [27] M. Fornier, A. Seidman, M. Schwartzl, Serum Her 2 extracellular domain in metastatic breast cancer patients treated with weekly Trastuzumab and paclitaxel association with Her 2 status by immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization and with response rate, Annals of Oncology 16 (2005) 234-239.

November 2013, Vol. 7, No. 11, pp. 1134-1142 Journal of Life Sciences, ISSN 1934-7391, USA

Investigation on the Perceptions of Living Donors

regarding Spousal Renal Donor Transplantation

Miyako Takagi

University Research Center, Nihon University, Tokyo 102-8275, Japan

Received: July 06, 2013 / Accepted: October 21, 2013 / Published: November 30, 2013.

Abstract: In Japan the average waiting time to receive a kidney from brain-dead patients or those in cardiac death is about 14 years. Therefore there is an increasing reliance of kidneys from living donor. Spouses are an important source of living-donor kidney grafts because, despite poor HLA matching, the graft-survival rate is similar to that of parental-donor kidneys. This study investigated the perceptions of living donors regarding spousal renal donor transplantation. We interviewed 8 donors about their feelings after transplantation using structured interviews. Many donors were not anxious and did not consider donation dangerous. However, in the case that the rejection occurred, as a result, transplantation was unsuccessful, the donor felt vain, and regretted that she was donor. On the other hand, total nephrectomy is often performed as a treatment for small size (4 cm or less) renal tumors and many of these nephrectomized kidneys could be successfully transplanted after surgical restoration with satisfactory results. Because of the lack of necessary evidence, it is currently not allowed in Japan. We estimated the 5-year recurrence rate of cancer after restored kidney transplantation would be less than 6%.We also asked donors the rights and wrongs for using the restored kidneys.

Key words: Perceptions of living donors, interview, renal transplantation, restored kidney transplantation.

1. Introduction

In Japan, the average waiting time to receive a kidney from brain-dead patients or those in cardiac death is approximately 14 years [1]. Because of the diminutive availability of cadaveric donor organs, kidneys must be procured from living donors. Spouses are an important source of living donor kidney grafts because, despite poor HLA (human leukocyte antigen) matching, the graft survival rate is similar to that of parental donor kidneys [2]. This study investigated the perceptions of living donors regarding spousal renal donor transplantation. The transplant system has been engineered around the needs of recipients. However, the welfare of the donor should be the primary concern.

Living donor kidney donation is a complex, ethical, moral, and medical issue. It is practiced with the

Corresponding author: Miyako Takagi, Ph.D., professor, research fields: bioethics, ethics of emerging technologies. E-mail: [email protected].

expectation that the risk of short- and long-term harm to the donor is outweighed by the psychosocial benefits of altruism and improved recipient health. However, there is a severe shortage of donor kidneys. In Japan, only family members can be living donors and 1,276 living donor kidney transplantations were performed in Japan in 2010.

On the other hand, at the end of May 2013, 12,623 patients were registered with the Japan Organ Transplant Network seeking renal transplantations. While awaiting transplantation, all these patients must receive dialysis treatment for survival. By the end of 2011, approximately 300,000 people across Japan were receiving dialysis for deteriorating kidney functions. On comparing dialysis and transplantation, the 5-year patient survival rate was much better in patients who underwent transplantation (90%) than in those on dialysis (60%) [3, 4].

The cost of dialysis averages 5-6 million yen ($50,000-$60,000) per patient per year [5]. The

D

Investigation on the Perceptions of Living Donors regarding Spousal Renal Donor Transplantation

1135

average cost for transplantation, including the transplant surgery and medical care for the first postoperative year, averages 4 million yen ($40,000). After the first year, costs for transplantation average 1.5 million yen ($15,000) mostly for medications to prevent rejection [6]. Almost all treatment expenses for dialysis and renal transplantations are paid by the Japanese National Health Insurance system. In Japan, the national government bears half the cost of health insurance and the remainder is paid equally by prefectures and towns.

For small towns such as those in the Amami islands, where the economical situation is severe, the burden of health insurance is a serious problem. Pongee and agriculture make up the local industry in this group of islands that falls under the jurisdiction of Kagoshima Prefecture in Japan, and the economic gap between the islands and the mainland is large. No facilities exist on the islands where transplant surgery can be performed; thus, the local self-governing body of the islands has initiated a system to cover traveling expenses for kidney transplant patients in order to reduce the cost [7]. Because of this system, the Amami islands have many more donors than the Japanese average. In addition, a well-organized Kidney Transplant Support Group has been established, consisting of a community of patients, family members, and friends dedicated to dealing with issues surrounding kidney transplantation.

Total nephrectomy is often performed as a treatment for small renal tumors (≤ 4 cm). Many of these nephrectomized kidneys could be successfully transplanted after surgical restoration with satisfactory results [8]. Because of the lack of necessary evidence for the potential success of restored kidney transplantation, this is currently not allowed in Japan. The issue of cancer recurrence is a concern in restored kidney transplantation. The 5-year recurrence rate of cancer after restored kidney transplantation remains undetermined and Nicol et al. supposed it is less than 1 out of 50 cases (0.5%) [9], however, that after

radical nephrectomy or partial nephrectomy is reported to be less than 6% [10]. We asked donors a question under the assumption of the 5-year recurrence of cancer after restored kidney transplantation be 6%. (This rate seems very high compared with the reality). Nevertheless, clinical research is currently underway to determine the feasibility of restored kidney transplantation as a method of alleviating the long waiting time and easing the suffering of patients who require transplantation.

2. Materials and Methods

Between March 8 and 11, 2012, 8 donors from the Amami islands were interviewed, in whom living donor kidney transplantation between spouses had been performed. Six were wife-to-husband transplants and 2 were husband-to-wife transplants. Donors were interviewed in a room in a hospital on Amami Ōshima island. Each interview lasted 30-60 min. The questionnaire used during these interviews is provided in Appendix 1.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1 Japanese Special Circumstances in Transplantation

Investigation on the Perceptions of Living Donors regarding Spousal Renal Donor Transplantation

1136

shorter (3-4 years and 3 years, respectively) [13].

3.2 The Informed Consent Process to Become a Donor

Informed consent by donors was obtained, and dedicated donor instructions were provided to each donor. The instructions that constitute the informed consent documentation are provided in Appendix 2. In the process of obtaining the informed consent, both donors and recipients were informed that the kidney graft was not guaranteed to be successful. Every effort was made to ensure that the risks to donors were clearly understood. These risks include a 1-in-25 chance of long-term (possibly permanent) pain at the site of kidney removal; a 1-in-500 chance of developing kidney failure again, as compared to the 1-in-2000 risk of anybody developing kidney failure whether they lose a kidney or not; and a 1-in-3000 risk of death after surgery. The patients were informed that the long-term survival rate, quality of life, and general health status are similar in donors and non-donors in the general population. However, after kidney donation, the risk of unilateral kidney failure should not be ignored. Regular checkups, including monitoring of the donor’s kidney function and blood pressure, are recommended to ensure the donor’s health.

3.3 Donor Interviews

Here the authors discuss three cases among the eight donors interviewed.

3.3.1 Case 1: Strong Opposition from a Relative The donor (wife) was in her 60s and the recipient (husband) was in his 70s. Both were Catholic and had been married over 30 years with 2 children. Only the husband was working outside home. The husband underwent dialysis treatment and experienced problems, including hemodialysis induced hypotension, nausea, and vomiting. He also experienced occasional loss of consciousness.

At that time, the wife thought that only a kidney from a blood relative could be utilized for transplantation. When they attended a lecture

regarding kidney transplantation, they learned that HLA differences could be overcome and that transplants between genetically unrelated spouses could be very successful. They also learned that the life expectancy of living kidney donors was better than that of non-donors in the general population because donors tend to take better care of themselves. After the lecture, the wife decided to become a kidney donor. The decision was made instantly, and the couple had few worries or concerns.

When she announced that she intended to donate a kidney to her husband, her daughter strongly opposed the idea. This opposition from a relative was a negative factor for this potential donor. In case of unforeseen circumstances, the daughter would be angry and difficulty and suffering would follow. The transplantation team refused the donation due to this strong opposition from the daughter, although the conditions might have been perfect, and the wife would have been the best surgical candidate. Consultations between the daughter and the doctor were held twice. The daughter was eventually convinced that this transplantation could save her father’s life, and the surgery was performed. After surgery, she was happy that her kidney had improved her husband’s quality of life.

Investigation on the Perceptions of Living Donors regarding Spousal Renal Donor Transplantation

1137

3.3.2 Case 2: A Donor with a Physical Disability The donor (wife) and the recipient (husband) were both in their 60s and had been married over 40 years. She had had a weak constitution as a child, for which she started school one year later than usual. As she grew up, her eyesight deteriorated.

Her husband experienced fatigue very easily, and his arteriosclerosis had been exacerbated because of 13 years of dialysis. At first, the recipient’s siblings had been asked to donate a kidney, but they refused. His health was declining every year, and the wife thought that the only way to save her husband was to donate a kidney. In the transplantation hospital, the wife underwent medical assessment. She learned that when one kidney was removed, the other would increase slightly in size and capacity and would then carry out the function of 2 kidneys. She could then live a completely normal life with one kidney.

After discussion with 2 transplantation doctors, the potential donor required time to think critically and consult with close friends before deciding whether or not to donate. She was afraid that the loss of one kidney would add to her visual disability. This fear of donating a kidney was perfectly normal. The wife also experienced guilt about not wanting to be a donor. She thought that if transplantation was not performed and her husband died as a result, she would regret very much her refusal to donate. Finally, she agreed to be a donor.

Transplantation was performed in 2010. After surgery, she experienced chronic but not debilitating pain around the scar. Her husband felt guilt for having put her through what he felt was an unnecessary surgical procedure. After a period of recovery, she was satisfied living an ordinary life with her husband.

She thought from her experience that kidney transplantation from a living donor was a medical treatment from which both the donor and the recipient suffered physically and mentally. She felt that the transplant system was centered around the needs of the recipient. However, the welfare of the potential

donor should be the primary concern. Therefore, she would not recommend this procedure to others.

When asked about restored kidney transplantation, she felt that a 6%-recurrence rate of cancer in the first 5 years after the procedure (our proposed assumption) was not high. She wished that her husband could become a patient in a clinical study of restored kidney transplantation and regretted that this option was not available.

3.3.3 Case 3: An Example of Kidney Transplant Failure

The donor (wife) was in her 40s and the recipient (husband) was in his 50s. Both were Catholic and had professional occupations. They had been married for 18 years and had one teenage child. Because the couple had been informed that refraining from dialysis prior to transplantation would improve the chances of success, the recipient received no dialysis. The prospect of successful transplantation was a significant source of hope and optimism for this couple. The decision to donate was made with little deliberation. However, the wife was afraid to tell her parent that she had decided to become a donor.

As a potential donor, the wife had completed the informed consent documentation and was informed about the possibility of graft failure, but she thought little about it. After the graft failed, she stated that if she had thought deeply about the possibility of graft failure, she would not have donated. However, because she understood that her husband was suffering from end stage renal disease, she decided to become a donor.

Investigation on the Perceptions of Living Donors regarding Spousal Renal Donor Transplantation

1138

required an enormous amount of emotional support. However, the hospital at which the kidney transplant had been performed was far from her home, and she could not go there again to receive the necessary psychological care. She found it very hard to accept that her kidney had been wasted, and she felt depressed. Fortunately, she was very busy with the care of her child and her work. Therefore, she was unable to brood over transplantation failure.

After surgery, this donor expressed anxiety about having only one kidney. She feared for her health in future. Therefore, she took care of herself and had periodic health checkups. Because transplantation had failed in this case, this donor could not recommend living donor kidney donation for the purpose of renal transplantation. She refused to join the Kidney Transplant Support Group for the fear of feeling jealous of others in whom transplantation had been successful.

When asked about restored kidney transplantation, this donor thought that a 6%-recurrence rate of cancer during the 5 years after transplantation (our proposed assumption) was not high. She had also heard at the dialysis center that the rate of cancer in dialysis patients was higher than average. Therefore, when restored kidney transplantation becomes an option, she wants her husband to receive this treatment.

3.4 Informed Consent and Decision Making

The ethical principles of autonomy underlie the requirement of informed consent to medical treatment [14]. In order to obtain valid informed consent, several issues must be addressed. For example, the donor must have a full understanding of the risks involved, the donor should be made aware of the risk of complications, and the alternative options available to the recipient should be discussed. The decision about whether or not to donate should be made by the potential donor. In addition, a potential donor has the moral right to take a reasonable risk in order to benefit recipient substantially. An organ may be removed

from a living donor only after the person has given free, informed, specific consent. Almost all the donors interviewed in this study went through a remarkably similar decision-making process when confronted with the idea of donating a kidney. They stated that the decision was made instantaneously when the possibility of kidney transplantation was first mentioned. It was not a cognitive decision; it came from the heart. It was an emotional and impulsive decision. This decision was made before the session with the team doctors in which all the relevant information and statistics were presented, and they were finally asked to decide. In other words, the donors were not really interested in the instructions and explanations in the informed consent documentation. The donors did not want to hear about the risks to themselves and the recipients. They wanted to make the decision to save their partners and convinced themselves that they were going to be fine. In the cases where the kidney graft failed, the donors behaved as if they had never heard about the risks and possibility of failure.

To some extent, informed consent is a myth. Donors hear very little of what medical personnel explain when they have already made up their minds to donate a kidney. Therefore, psychological support after donation is probably more important than pre-evaluation assessment. In hospitals with programs on living donors, a social worker or psychologist must be available to address post-transplantation issues and concerns.

3.5 Analysis of Donors’ Perceptions

Investigation on the Perceptions of Living Donors regarding Spousal Renal Donor Transplantation

1139

needs.

In cases where transplantation was successful, donors felt great satisfaction with the experience because they had helped to improve their spouses’ quality of life. When donors saved recipients by agreeing to the procedure, their perceptions toward the recipients were stronger than before the operation in some cases. For example, in case 1 described above, the donor felt very glad because she and her husband were closer because of the kidney transplantation.

Feelings of grief, loss, and depression occurred in cases where the outcome of the surgery did not meet the expectations of the donor. Although they felt that they had done their very best to help their spouses, the graft had been rejected and transplantation was not successful. Preoperatively, the donors only thought about the potential for recovery of the recipient. After graft failure, they acted like they had never heard about the possibility that the procedure would not be successful. As they were not prepared for this possibility, physical and psychological pain was a reality after surgery.

3.6 Restored Kidney Transplantation

When asked about restored kidney transplantation, 6 donors thought that a 6%-recurrence rate of cancer during the first 5 years after transplantation (our proposed assumption) was high. They would not have chosen this option for their spouses if it had been available. In contrast, the other two donors would have preferred this option. These two donors had learned at the dialysis center or in a lecture on kidney transplantation that rates of cancer in dialysis patients were higher than in the general population. Therefore, they thought that a 6%-recurrence rate of cancer after restored kidney transplantation (our proposed assumption) was not high. Patients have been known to resist the idea of receiving a previously cancerous kidney. Certainly, cancer risk is increased by 10%-80% in chronic dialysis patients than in the general population, according to several studies [15].

Because of the reduced quality of life experienced by dialysis patients, the high risk of mortality for patients on long-term dialysis, and the extremely long waiting list for transplantation, the option of restored kidney transplantation may be an attractive alternative for some patients.

In many cases, total nephrectomy was performed even for small (≤ 4 cm) renal tumors. In a previous clinical study, ten of these nephrectomized kidneys were successfully transplanted to unrelated recipients after surgical restoration [8]. Recipients in this clinical trial were selected on the basis of blood group match, high clinical evaluation scores, and negative results of cross-match testing. The term “match” refers to 6 possible HLAs. Before treatment with anti-rejection medications, 6 out of 6 antigens must match for successful transplantation [16].

Some concern has been expressed regarding the possibility of transmitting disease after restored kidney transplantation. Many urologists are concerned about issues of immune suppression surrounding restored kidney transplantation. For example, melanoma and many other cancers are more likely to develop in immunosuppressed patients [17]. However, others see the risk as minimal and recurrence of cancer as extremely unlikely in non-immunocompromised patients. One study revealed the risk of tumor recurrence in the same site to be as low as 0.5% in patients who underwent partial nephrectomy [18]. In addition, de novo tumor growth in the same kidney occurred in only 0%-6% of patients according to studies [10]. Thus, kidneys restored after radical nephrectomy may be expected to have similarly low rates of tumor growth and recurrence in transplant recipients. The relation of newly developed cancers to previous renal cancers in either kidney is uncertain.

4. Discussion

Investigation on the Perceptions of Living Donors regarding Spousal Renal Donor Transplantation

1140

kidney disease on dialysis outweighs the risk of possible cancer recurrence or disease development in the transplanted kidney. Ethical considerations necessitate informing the patient of the status of the kidney prior to obtaining consent for the procedure. Patients on the waiting list are emotionally very vulnerable. During counseling, data must be provided to demonstrate the statistical possibilities of cancer recurrence in restored kidneys. A maximum 6%

chance of developing de novo cancer is a better

statistic than a mortality rate of 40% during 5 years of dialysis [5]. In the event that cancer does recur in the donated organ, partial nephrectomy can again be performed. This is still advantageous from the point of view of long-term survival compared to dialysis.

In countries like Japan, where the demand for donated kidneys far exceeds the supply, transplantation using a previously cancerous donor kidney may offer some relief of pressure on family members to donate. Recipients may also feel better about not having to ask family members to be donors. Using restored kidneys resulting from nephrectomy because of cancer alleviates this problem to some extent. Other problems in Japan include kidneys donated through an illegal trade, faked adoption, or illegal transplant surgery using kidneys donated by foreigners in developing countries. These problems could also be avoided by restored kidney transplantation.

Transplantation of kidneys that have been restored after resection of cancerous lesions may also aid in solving the ethical dilemma that many doctors face when potential donors want to back out at the last minute. As advocates for both patients and donors, they may find themselves having to inform families that donors have changed their minds about donating. Rather than putting donors in such a difficult position, the temptation may arise to take the blame for a nonexistent error in order to protect family relationships and the present and future health (both mental and physical) of the potential donor.

Previously-cancerous donor kidneys that have been restored after nephrectomy may be added to the donor pool to relieve the pressure on families, doctors, and transplant recipients.

5. Conclusion

Organ donation is a stressful experience. Donors’ psychological states must be assessed in terms of their ability to handle stress and depression. Psychiatric support is more crucial after donation. Many people still rely on emotion and not intellect to guide them in decision making about donation. Thus, Japanese public policy and transplant centers should take a more proactive role in screening and evaluation of prospective donors.

The psychological issue is that of transplant rejection or failure, which can occur regardless of the number of tests that are performed. This can be devastating to both the donor and the recipient and must therefore be considered very carefully. The lack of research in this area significantly limits our insight and understanding of the transplant failure experience. Information about the psychological and emotional states of donors could be used to inform and develop clinical practice. This is an area in need of further research.

Other issues, such as regulations regarding who can donate, the problems of performing surgery on healthy individuals (donors) who otherwise would not require it, illegal coercion of donors, and pressure on doctors who advocate for donors may be partially alleviated by addition of restored kidneys to the donor pool.

Acknowledgments

We thank the 8 donors and the Tokushukai Hospital in the Amami islands for allowing the interviews. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 23613009.