Labour supply in the home care industry: A case study

in a Dutch region

Elly J. Breedveld

a,∗, Bert R. Meijboom

b, Aad A. de Roo

baThebe/Tilburg University, PO Box 1035, 5004 Tilburg, BA, Netherlands bTilburg University, PO Box 90153, 5000 Tilburg, LE, Netherlands

Abstract

Health organizations have started to become more market-driven. Therefore, it is important for health organizations to analyse the competitive dynamics of their industrial structure. However, relevant theories and models have mainly been developed for organizations acting in the profit sector. In this paper, we adapt Porter’s ‘five forces model’ to the home care industry. In particular, we modify the (determinants of the) bargaining power of labour suppliers. We then apply the modified Porter-model to the home care industry in the Netherlands for the period of 1987–1997 with special attention for labour supply.The new instrument clarifies the complexity of the supply chains and value systems of the home care industry. As can be illustrated by developments in the home care industry in the province of North Brabant during the 1990s, competition between home care providers has influenced labour market relations, but so do other factors as well. Between 1987 and 1997, the bargaining power of labour suppliers was relatively limited. After 1997, however, the demand for home care personnel has increased strongly. In spite of the present economic recession, scarcity on this labour market seems to prevail in the longer term due to a growing demand for home care services.

© 2005 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Competitive analysis; Strategic management; Labour supply; Home care

1. Introduction

Since the 1980s, the Dutch health and home care policy can be characterized by efforts to introduce more competition and ‘business risks’ for insurers and health care providers. In the home care industry, the gov-ernment stimulated competition in several ways and

∗Corresponding author. Tel.: +31 13 5947299.

E-mail addresses: elly.breedveld@thebe.nl (E.J. Breedveld), b.r.meijboom@uvt.nl (B.R. Meijboom), aad.de.roo@12move.nl (A.A. de Roo).

reduced the home care organizations’ protected status. For example, since 1994 new entrants have been admit-ted to the home care market whereas the domains and markets used to be strictly defined and divided with no free entrance for new suppliers. As a result, self-evident certainties on the budget as well as on the sales side have come under pressure. More and more, home care orga-nizations have to compete for clients and money and become more market-driven. Thus, managers in home care are confronted with a new task, namely to guaran-tee the viability and continuity of their organization and to create a surplus (the difference between revenues

and expenditures) in order to survive in a more compet-itive market. More specifically, as labour accounts for a large part of the costs of home care providers, one might wonder how the strategic position of suppliers of labour with respect to these home care providers has evolved and what consequences this has had for the position and ‘profitability’ of the organizations within that sector.

Because of the shift towards more market-driven behaviour of this traditionally non-profit sector, we propose to use a modified version of Porter’s

well-known five forces model[1]. In its original form,

this model accounts for rivalry among existing firms, bargaining power of buyers, threat of new entrants, threat of substitute products or services, and bargaining power of suppliers. Using an extended version of this tool, we will analyse the Dutch home care industry in the province of North Brabant during the period 1987–1997. The year 1987 marks the birth of the idea to introduce competitive elements into the health care sector as a whole. By 1997, the functioning of the market mechanism in the home care industry was tem-porarily frozen, until the year 2001, when the market mechanism experienced a revival. In the analysis of structural changes in the home care industry, specific attention will be paid to the strategic position of labour suppliers and its effect on profitability and social benefits. It should be noted that, since the present study is concerned with a specific industry within a

certain country, Porter’s famous ‘Diamond model’[2],

which addresses issues of international competitive-ness, was considered much less appropriate for our purposes.

The empirical application of the modified ‘five forces model’ encompasses an explorative analytical description, rather than an explanation, of the changes in the dynamics in the home care industry structure. The type of research that is applied is the case study [3], as we offer an empirical enquiry in which:

1. A contemporary phenomenon is investigated within its real-life context.

2. The boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident at all times.

3. Multiple sources of evidence are used.

For the purpose of this research the home care indus-try is functionally defined to include all types of organi-zations that offer professional services at any moment

in the area of nursing and/or physical or domestic care at the home of physically ill, infirm or elderly people. Organizations that provide care services for the men-tally ill or menmen-tally of physically disabled are excluded from this study.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we will sketch the macro-environment which forms the con-text of the central question and show the importance and usefulness of business-oriented instruments for analysing structural changes in the originally typically non-profit home care industry. Second, we present an instrument derived from a set of tools originally developed for market sectors and adapted and extended here for use in the home care industry. The descrip-tion of the extended instrument is followed by the application in our case environment. Some insights for the home care industry as a whole will be presented first, before we analyse the influence of suppliers on the labour market in more detail. We end up with conclusions.

2. Towards a more competitive environment

As in other European countries[4], major health

care reforms in the Netherlands were initiated at the end of the 1980s. In this paper, the focus is on the period 1987–1997. In the year 1987, the ‘Dekker commit-tee’ advised shifting policy from a (central) planning approach to a more market-oriented approach with more responsibilities and (financial) risks for health

insurers and health care providers[5].

In the 1970s and 1980s health care costs increased

rapidly. To illustrate [1], expressed in millions of

Dutch guilders, the expenses for home care grew from 513 to 2561 between 1974 and 1987, and in 1998 it had become 4330. Until 1987, the reimbursement mechanism could be characterized as open-end financing without a macro budget, so there were hardly any incentives for health care organizations to behave efficiently and in a goal-oriented manner. Furthermore, few possibilities for substitution existed and there was no freedom for patients to receive health care service suited to their particular needs.

the home care market and the introduction of Personal Budgets (in Dutch: Persoons Gebonden Budget, abbreviated PGB). More specifically, the Dutch health insurance system (AWBZ) started to offer not only care in kind but also Personal Budgets (cash). The insured are given a budget in order to contract and pay health care services themselves. Personal Budgets are intended to create a possibility for patients/clients to buy care from providers of their own choice [6].

Although the radical reform plans were toned down in 1994, when a new government introduced a mix-ture of several incentives, the Dutch health and home care policy since the 1980s can be characterized by efforts to introduce more competition and ‘business risks’ for insurers and health care providers. By 1997 the functioning of the market mechanism in the home care industry was temporarily frozen.

Before making an analysis of the transitions in the home care industry in North Brabant, the (prevailing) macro-environment will be described. This covers the political, economic, social, cultural, and technological developments between 1987 and 1997, including the demographic and epidemiological trends. These trends have a strong impact on the industry structure. Specif-ically, the following influences can be distinguished [7,8]:

• Demographic and epidemiological. The number of

elderly people in North Brabant increased, in partic-ular the number of elderly single women. Also the number of people with chronic diseases increased. This caused a growing demand for complex types of home care. The growth in demand was also caused by technological and socio-cultural trends and government policy, which stimulated a shift from intramural to extramural care. The growth in demand for (complex) home care services potentially reduced mutual competition among the suppliers.

• Economic. The growth in demand for home care

services was not matched by a growth in financial resources. Consequently, scarcity caused an increase in rivalry between home care providers. In addition, intramural organizations also faced scarcity. This stimulated a shift to extramural care and increased the potential threat of new entrants on the home care market. At the same time, a decrease of hospital beds meant a decreasing threat of substitutes of

home care. In contrast to Porter’s thesis that lack of substitutes will lower the intensity of competition, the home care industry in North Brabant shows the opposite: the lack of financial resources and substitute services increases the social pressure on home care organizations to produce more, without an increase in their revenues (because of the budget system). The home care organizations’ surplus is thus reduced.

• Socio-cultural. Increasing individualization and

emancipation stimulated demand quantitatively as well as qualitatively. The client asks for ‘customized care’. New entrants used the opportunities to sell new types of home care, sometimes in joint venture with other complementary providers within in the sector.

• Political/regulatory. Policy measures play an

impor-tant role in stimulating competitive forces. Policy measures that reduced the home care organizations’ protected status and stimulated competitive forces are:

◦ The admission of new entrants to the home care

market since 1994 (before, the domains and markets were strictly defined and divided with no free entrance for new suppliers).

◦ The reduction of the existing home care

organi-zations’ budget guarantee by 5% in 1995. The initial idea was to reduce budget guarantees slowly up to 35%. However, this was never reached, because the government decided to freeze the market mechanism in 1997 because of disequilibria in the market.

◦ Abolition of the Health Insurance Fund (so-called

Sickness Fund) obligation to sign contracts with home care providers.

◦ Introduction of tariff caps instead of fixed tariffs.

◦ Introduction of competitive elements in the

tender for supply contracts and subsidies for possible market entrants.

3. Theoretical background

In the previous section, we have described changes in the environment that urged health organizations to analyse the competitive dynamics of their industrial structure. However, relevant theories and models have mainly been developed for organizations acting in the profit sector. As a consequence, strategic management models for non-profit organizations are hardly available.

3.1. Extant literature

For an extensive review of economic and manage-ment theories at the level of industries, we refer to

Breedveld[1]. See also Rumelt et al.[9], Scott[10]and

Fahey and Narayanan[11]. Breedveld [1] concludes

that, in this literature, certain tools and techniques are available that, probably in some adapted form, could

help to analyse the restructuring ofnon-profit

indus-tries towards market orientation. More specifically, the ‘strategic management approach’ has produced, among other tools, several techniques to analyse competitive markets from the perspective of individual organiza-tions and their performance (profitability). In addition, the ‘industrial organization approach’ provides appli-cable frameworks to analyse competitive markets and

firm behaviour in relation to social benefits[12,13].

3.2. Porter’s five forces model

In this paper, Porter’s five forces model is taken as the starting-point to analyse the emerging competi-tive atmosphere between 1987 and 1997 in the Dutch

home care industry[14,15]. Porter’s five forces model

is one of the most influential management tools for strategic industry analysis. The model applies insights from industrial organization theory to analyse the com-petitive environment on the level of business units. The basic proposition of Porter’s five forces model is that organizational performance mainly depends on the industry structure. In turn, the industry structure is com-posed of five main forces that determine its intensity of competition:

1. Existing rivalry among firms. 2. The bargaining power of buyers. 3. The bargaining power of suppliers.

4. Threat of new entrants.

5. Suppliers of substitute products or services.

The stronger each of these forces within an industry, the stronger the intensity of competition and therefore the less the industry provides opportunities for orga-nizations to achieve profits. However, because of the specific characteristics of non-profit health organiza-tions, the model has to be modified before we apply it in our case environment.

3.3. Instrument for analysis: the Porter-plus model

As a first step, Porter’s model has to be extended by two additional forces:

• The influence of the government.

• The relations with suppliers of complementary

prod-ucts or services.

In Porter’s model, the government indirectly influ-ences the structure and profitability of an indus-try through the central five forces. However, several authors distinguish a more direct role of the government

as a separate competitive force[16,17]. The second

force consists of products that add value by

simulta-neous consumption[18]. In addition, Porter’s model

is complemented by two other elements, i.e. macro-factors and organizational strategy. In our opinion, the structure of industries cannot be well understood without incorporating these elements in the analytic framework. In fact, this extension is in line with the structure-conduct-performance paradigm in industrial

organization theory[13]. In our framework, we also

take into account the consequences of industry struc-tures, i.e., organizational and industrial performance (profitability) on the one hand and social benefits (for buyers) on the other hand.

publicly financed. In contrast, the privately financed home care organizations seem to be more similar to the profit industry and are therefore expected to fit more closely into Porter’s original forces model. In practice, however, the distinction between publicly and pri-vately funded home care organizations appears rather small.

The major adaptation of Porter’s model necessary before it can be applied to both types of the home care organizations is to add the bargaining power of the fol-lowing three actors to the model, in the form of three additional competitive forces:

• The roles of the ‘gatekeepers’ (who determine the

type and amount of service needed and direct clients to service providers).

• The suppliers of (sequential) complementary

prod-ucts.

• The providers of financial sources in the home care

industry.

These three additional forces can be further clarified as follows. In many health care systems, gatekeepers, clients, and financial institutions have separate roles. These roles correspond with the essential distinction between ‘deciding, consuming, and paying’ for health care services. In contrast to the profit sector, where the decision to consume, the actual consumption, and the payment for the consumption are concentrated

in the same actor, these actions are often distributed among three different actors in the health care sector.

Furthermore, within the home care industry it is difficult to specifically apply the value chain concept, since the ‘assembly of services’ cannot be clearly defined. Actors within the supply chain deliver their services directly to the customer (patients), but without delivering these (sub)services to each other. Conse-quently, the value chain of the home care industry is rather limited, as inputs (personnel and capital) are directly shifted to the customer with interference by only home care organizations. Nevertheless, suppliers of services that are sequential to the home care services, like nursing homes and hospitals, have become increasingly important. They partly regulate client flows and consequently determine the home care organizations’ opportunities to generate turnover and surplus. Because of this influence, they are added as an additional competitive force to Porter’s model.

Finally, insurance companies govern the financial flows that accompany the flow of service along the sup-ply chain (Fig. 1).

In many other countries, these adaptations of the model will be the same for the health care sector. With respect to the home care organizations that are fully based on public funding, the adaptation of Porter’s model is taken one step further. This is necessary

because of the following characteristics of publicly financed (non-profit) home care organizations.

Firstly, Porter’s assumption on profit maximization on behalf of shareholders does not apply. Instead, publicly financed home care organizations deal with a dual concept of profit making. On the one hand, budgets need to be spent as efficiently as possible. Secondly, financial surpluses are supposed to con-tribute to additional social benefits, in terms of quality (differentiation of products, ‘customized care’) and access to care (serving more patients within the same budget). Consequently, Porter’s model needs to be supplemented with the social perspective and the common interests of the home care industry.

Secondly, organizations in the Dutch home care industry are not operating in an environment where price signals coordinate processes (prices are fixed). As a result, increasing competition will not influence prices but costs and revenues. Decreasing revenues (because of competition) in combination with stable or increasing costs will put the home care organiza-tions’ potential surpluses under pressure. The same holds for increasing costs in combination with stable or decreasing revenues. Moreover, movements towards a price mechanism are about to emerge within the pub-licly financed sector of the home care industry, by, for instance, tariff caps (instead of fixed tariffs) and out-put financing. Clearly, these trends will narrow the gap between Porter’s model of industry competition and the structure of home care industry.

In the next subsection, we will elaborate one of the elements of the Porter-plus model in more detail, namely the bargaining power of suppliers on labour markets. As employees account for many of the costs of home care organizations, the bargaining power of labour suppliers is an important competitive force that influences surpluses of organizations in the home care industry.

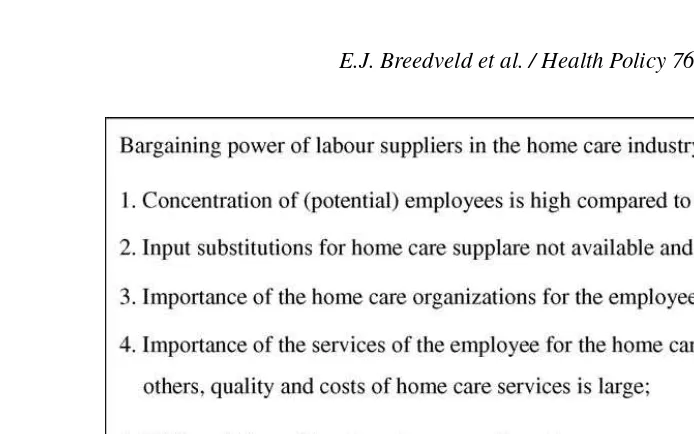

3.4. Bargaining power of suppliers of labour

Assuming no changes in the other dimensions, an increase of the bargaining power of labour suppli-ers may lead to more competition and a decrease in the ‘profitability’ of health organizations. Therefore, analysing changes in the labour supply is relevant for managers in the health care sector. Porter brings up sev-eral determinants of the bargaining power of suppliers, whether it be investors of capital, suppliers of materials or labour suppliers (Fig. 2).

It is important to specify these determinants of the specific conditions of the home care industry and make them fit for use in our (non-profit) setting. Here, we focus on the power of suppliers of labour. The individ-ual (potential) employees that deliver labour are rep-resented by their labour unions, which negotiate about collective labour agreements and, among other things, make wage agreements. When there is a tight labour market, home care suppliers will have to compete with one another for employees. This may increase costs or

Fig. 3. Determinants of the bargaining power of labour suppliers in the home care industry.

wages and go at the expense of the surplus of home care organizations. This will definitely be the case when the increase in wages cannot be compensated for in the budget agreements with financiers. Besides, lack of labour makes it more difficult for home care organiza-tions to increase production and revenues. Depending on the bargaining power of employees, the pressure on the home care supplier’s surplus will be more or less serious. The determinants of employee bargaining power in the home care industry (after Porter) will be

summarized inFig. 3.

4. Empirical results

Earlier in the paper, developments in the macro-environment of the home care industry were described. Subsequently, we presented the Porter-plus model. This instrument is based on Porter’s five forces model, which originally was developed for market sectors and has been adapted and extended here for use in the home care industry. Now we turn to the empirical part of the paper. This comprises the application of the Porter-plus model in our case environment. Some insights for the home care industry as a whole will be presented first, followed by a more detailed analysis of the influence of suppliers on the labour market.

4.1. Generic insights following from application of Porter-plus model

The period 1987–1997 was dynamic in terms of competition and achieved surpluses. Applying Porter’s model, the following forces appeared to have been most influential:

• The threat of new entrants was stimulated by policy

measures to lower barriers to enter the market and lower barriers for financiers to switch between care providers.

• The bargaining power of financiers (health insurers)

was increased because of the increased opportunities for financiers to switch between care providers.

• The bargaining power of clients was increased

by extending their choice options among health providers by allowing them to allocate a PGB (see earlier).

• The rivalry between competitors was increased by

the entry of new suppliers of home care services, the increased bargaining power of financiers, lim-ited budget growth in relation to the strong growth in demand, and less cooperative behaviour between home care suppliers.

• The direct influence of the government put home

by keeping budgets limited compared to the increase in demand. The surplus of home care suppliers also decreased as policy pressures stimulated comple-mentary suppliers and gatekeepers to divert patients away from intramural care towards home care.

• The threat of substitutes decreased by the forces

described previously, thereby increasing the pres-sure on home care institutes to provide more services without receiving more revenues. This reduced the organizations’ surplus.

If we picture the situation of the home care industry in North Brabant in the year 1997, competitive forces did indeed increase, but the intensity of competition was still rather modest. Home care organizations that serve the so-called AWBZ-market (obligatory national insurance for long-term diseases, the so-called first compartment of the insurance system) retain their strong bargaining position towards financiers and patients. In this part of the sector, the threat of new entrants and mutual rivalry is limited. One important reason for this is the strategic behaviour of the home care organizations. Mergers and alliances created regional monopolistic positions for these organiza-tions, thereby partly eliminating new competition. In addition, the organizations strategically cooperated with financiers and complementary suppliers. Home care organizations that (also) serve the so-called second compartment of the insurance system (sickness fund or privately insured home care) did experience a strong increase in competition. In particular, the insurance companies gained a strong bargaining position within the industry structure.

4.2. Labour supply

The increase in the influence of several competitive forces between 1987 and 1997 put home care organi-zations’ surpluses under pressure. Limited budgets due to government cost containment policy, new entrants, an increase in the bargaining power of financiers and clients forced home care organizations to squeeze their costs in order to survive in a more competitive market.

An important question is what consequences this had for the (potential) employees of home care organi-zations. Was it possible to shift the threat of financial losses for home care organizations on to employees, as

partly happened to clients through growing waiting lists and rationing of care? This question coincides with that of the bargaining power of labour suppliers in relation to the bargaining power of the buyers, in this case the home care organizations. In the following subsections, we present the changes between 1987 and 1997, the situation in 1997, and finally the effects on personnel and profitability of home care organizations.

4.3. Changes in the bargaining power of labour suppliers between 1987 and 1997

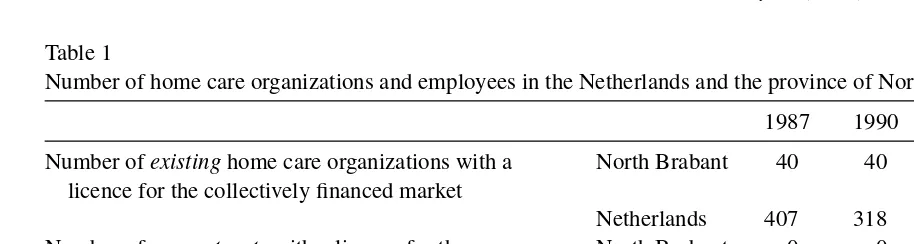

The application of determinants of bargaining power of labour suppliers shows that between 1987 and 1997 their buying power somewhat increased as a consequence of several determinants. Especially the decreased importance of home care organizations for the market of employee services plays an important part

(determinant 3 inFig. 3). In the time interval under

consideration, private (commercial) home care sup-pliers were allowed to enter the collectively financed home care market. Also, the number of home care orga-nizations on the privately financed market increased (see Table 1). Because of this, the alternative pos-sible choices for (potential) employees to offer their services increased. This enhances the competition for personnel between existing home care organizations and newcomers, and with this, the bargaining power of employees. Besides, the threat of forward integration of

employees grew (determinant 7 inFig. 3). The

intro-duction and gradual increase in the system of PGB’s made private set-ups more attractive for employees, to offer their services to clients with a personal budget.

However, more determinants seem to have con-tributed to a decrease in the bargaining power of labour suppliers. If we take stock of the situation in 1997, we can conclude that the bargaining power of labour sup-pliers in that year was relatively limited in relation to the buying power of home care organizations. The most important determinants that contribute to this situation will be mentioned hereafter.

• There was a relatively high concentration of existing

home care organizations in the province

(determi-nant 1 inFig. 3). A huge number of mergers between

1987 and 1997 resulted in regional monopolies of

home care organizations (see Table 1). Because

Table 1

Number of home care organizations and employees in the Netherlands and the province of North Brabant between 1987 and 1997

1987 1990 1994 1995 1996 1997

Number ofexistinghome care organizations with a licence for the collectively financed market

North Brabant 40 40 22 19 19 14

Netherlands 407 318 127 119 117 111

Number ofnew entrantswith a licence for the collectively financed market

North Brabant 0 0 0 1 4 4

Netherlands 0 0 – – – 25

Number of home care organization on privately financed market

North Brabant – – 29 – – 36

Number of nursing and caring employees in home care Netherlands 117.032 128.655 129.208 130.763 Number of full time equivalents Netherlands 50.066 48.579 47.102 47.790

Sources:[19,23,24].

travel far to their employer/clients had relatively few possible choices to offer their services.

• There was no serious shortage on the labour market

in 1997 (determinant 2). The home care organiza-tions were still provided with ‘sufficient’ input. The supply of labour was sufficient in relation to the relatively limited demand for labour as caused by

tight budgets (seeTable 1: the limited demand for

labour appears from the relatively limited growth of the number of employed persons in the nursing and caring professions in the home care sector and a relatively stable number of full-time jobs) [19].

• Although the number of new entrants on the

col-lectively and privately financed home care market

increased (see Table 1), the existing home care

providers were still the most important buyers of the services of labour suppliers (determinant 3). In 1997 only 5% (maximum) of the total workforce in home care worked for the new entrants. In addition, the existing home care organizations strategically anticipated on the loss of employees to private (commercial) new entrants by setting up private organizations themselves.

Compared to other sectors in health care, the home care sector is one of the most important employers for nursing and caring personnel in the health care sector. In 1996, about 35% of nursing and caring employees worked in the home care sector, about 20% in hospitals, 26% in nursing and elderly homes [19]. See also Hingstman et al. [20]. Although competition among these different employers might occur, this was still limited in 1997 because shortages on the labour market were not yet severe.

• The influence of the system of PGB’s and

for-ward integration of (potential) employees was limited (determinant 7). Research has shown that competition for employees between home care organizations and PGB holders was not that strong [21]. In most cases, it is about paid informal care or re-entrants in the labour market and no personnel is taken away from existing home care organizations.

• Costs of labour were high compared to the total

costs of home care organizations (around 80%) (determinant 8). This renders home care organi-zations more price-sensitive. Although the price of labour in the home care market is regulated by labour unions and employers’ organizations in collective labour agreements, a cost reduction can be realized by a shift from more expensive to relatively cheap workers. For certain occupational groups, in particular the (highly educated) nurses, this means a weakening of their bargaining power.

Summing up, home care organizations hardly have to compete for personnel in 1997, firstly because the number of new entrants was limited and secondly because enough personnel was still available. The rel-ative power position of home care institutions in 1997 makes it possible, in principle, to shift the (threaten-ing) financial losses with which they were confronted in the time interval under consideration, on to (poten-tial) employees.

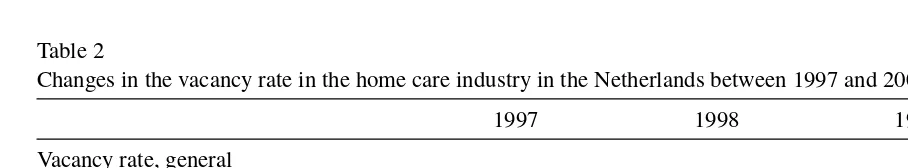

Table 2

Changes in the vacancy rate in the home care industry in the Netherlands between 1997 and 2001

1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Vacancy rate, general

Health care and welfare sector 1.2 1.6 1.9 2.1 2.5

Home care 1.2 1.9 2.5 2.7 3.2

Vacancy rate, difficult to fulfil

Health care and welfare sector 0.5 0.8 1.0 1.3

Home care 0.7 1.0 1.3 1.4

Source:[20].

4.4. Effects on personnel and profitability of home care organizations

Particularly in the mid-1990s, home care organiza-tions were confronted with financial losses caused by increased competition and tight budgets. The existing home care organizations’ budgets were cut by 5% to give room to new entrants. Research in the province of North Brabant has shown that home care organiza-tions were able to limit the financial losses by shifting

them on to employees[1]. An increase in productivity

and cost-cutting measures hit the suppliers of labour in several ways.

• Many organizations made labour relations more

flex-ible, on the one hand to control costs, on the other hand to be able to realize a customer-oriented supply of care. Examples of more flexibility are: temporary contracts, min-max contracts (with a minimum and a maximum number of working hours), 0 h contracts, increased input of temporary workers, a decrease in the number of working hours in employee con-tracts. Some organizations even had redundancies. Because of this, the degree of security for employ-ees decreased.

• The realization of savings on personnel by

techno-logical aid supplies.

• A move from relatively expensive to cheaper

per-sonnel[19]. Many home care organizations replaced

part of their personnel in paid employment by ‘alpha assistants’ who are not employed by the organiza-tion. A shift also took place from nursing to caring

personnel (lower level of professionalism)[22].

• The consequence of a smaller number of hours

per client (rationing) was less attention and time for the client while work pressure for the per-sonnel increased. Moreover, the labour satisfaction

decreased as a consequence of the introduction of the ‘Taylorian work methods’, implying the registration of patient care minute by minute.

The shift of costs on to employees is consistent with the relatively strong power position of home care orga-nizations in 1997. Since then, however, the bargaining power of labour suppliers improved, primarily as a consequence of the increased tightening of the labour market. Furthermore, the government allowed an increase of the budgets in an attempt to resolve waiting lists problems. As a consequence, labour demand increased. The number of persons employed in the home care sector increased, but the number of (hard

to fill) vacancies increased as well (seeTable 2)[20].

Moreover, since 2001 the importance of the exist-ing home care providers for employees has dwindled because of the increasing number of private suppliers and a growth of the PGB system. Although we did not research the labour conditions and circumstances of employees after 1997, one can assume that these have improved because of the improvement in the bargain-ing power of labour suppliers after 1997.

5. Conclusion

At the outset of the paper, we have described changes in the macro-environment that stimulated health organizations to analyse the competitive dynam-ics of their industrial structure and to behave more business-oriented. As a result, the Dutch home care sector is shifting towards more business-orientated behaviour and attitudes. This is partly due to the gov-ernmental stimulus towards more internal competition. Consequently, instruments of strategic management – which originally stem from the profit sector – become increasingly important for the home care industry, as it is losing its pure character of a non-profit sector. Still, the core strategic management tool for analysing indus-try competitiveness, Porters’ five forces model, had to be adapted and extended significantly for use in the home care industry.

Basically, this extension implies adding the influ-ence of five additional competitive forces:

• Direct influence of the government.

• Relations with suppliers of complementary products

or services.

• Bargaining power of ‘gatekeepers’ (who determine

the type and amount of service needed and direct clients to service providers).

• Bargaining power of suppliers of (sequential)

com-plementary products.

• Bargaining power of providers of financial sources

in the home care industry.

This way, the modified Porter-model appears to be useful for analysing the restructuring of the home care industry in the Netherlands. The instrument helps to understand the structural changes in the home care industry, given its difficult task to sustain social benefits against pressures to initiate economic and strategic actions. The instruments also demonstrate the complexity of the supply chains and value systems of the industry, i.e., the specific role and position of complementary health care suppliers and the interdependency between all actors. This complexity and interdependency also influences the labour supply as one of the important forces in the competitive environment of home care organizations.

What is the distinctive role of labour supply within our tailored strategic management model of the home care industry? In theory, it makes sense to consider labour forces (in particular the current and potential home care employees) as an important ‘supply force’

within the home care industry. Vacancies, unemploy-ment, wages and labour conditions reflect the status of the labour market for home care personnel.

Application of the Porter-plus model to the home care industry in the Netherlands shows that the influ-ence of suppliers of labour slightly increased between 1987 and 1997. This is especially caused by a decreas-ing dependence of potential labour suppliers on exist-ing home care organizations only and a growexist-ing threat of forward integration. However, more determinants seem to have contributed to a decrease in the bargaining power of labour suppliers. If we take stock of the situa-tion in 1997, we can conclude that the bargaining power of labour suppliers in that year was relatively limited. A number of factors contributed to this situation: the con-centration of home care organizations caused by strate-gic mergers, no serious shortages on the labour market, limited budgets of home care organizations, relatively high labour costs, and the importance of existing home care providers as buyers of the services of labour suppliers.

However, within the constellation of competi-tive forces, the bargaining power of the home care workforce became stronger after 1997. Since then, home care organizations have experienced substantial budget increases to solve waiting lists. This has caused a growing demand for labour, while the supply side of the labour market had lagged behind for a number of years. In spite of the present economic recession, scarcity on the labour market for home care personnel seems to prevail in the longer term, due to a growing demand for home care services.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Ronald Batenburg and Geertje Verbraak for providing several comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this paper. An ear-lier version of this paper was presented at the EHMA conference in Sicily in 2003.

References

[2] Porter ME. The competitive advantage of nations. Harvard Busi-ness Review 1990;68(2):73–93.

[3] Yin RK. Case study research, applied social research method series, vol. 5. London: Sage Publications; 1994.

[4] Social and Cultural Office. Social and Cultural Report 2000 (in Dutch). Den Haag: SCP; 2000.

[5] Committee Structure and Financing of Heath Care (committee Dekker). Readiness for change. Den Haag: Ministry of Welfare, Health and Culture; 1987 (in Dutch).

[6] Kertzman E, Janssen R, Ruster M. E-business in health care. Does it contribute to strengthen consumer interest? Health Pol-icy 2003:63–73.

[7] Social and Cultural Office. Social and Cultural Report 1998. 25 years of social changes. Rijswijk: SCP; 1998.

[8] Elsinga E, van Kemenade YW. From revolution to evolution. Ten years of reforming the Dutch health care system. Utrecht: De Tijdstroom; 1997 (in Dutch).

[9] Rumelt RR, Schendel DE, Teece DJ. Fundamental issues in strategy. Harvard Business School Press; 1994.

[10] Scott WR. Organizations: rational, natural and open systems. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall; 1998.

[11] Fahey I, Narayanan VK. Macro-environmental analysis for strategic management. St. Paul/New York: West Publishing Company; 1986.

[12] Devine PJ, Lee N, Jones RM, Tyson WJ. An introduction to industrial economics. London: George Allen and Unwin; 1993. [13] Scherer FM, Ross D. Industrial market structure and economic

performance. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1990. [14] Porter ME. Competitive strategy, technique for analyzing

indus-tries and competitors. New York: The Free Press; 1980.

[15] Porter ME. Competitive advantage. New York: The Free Press; 1985.

[16] Snier H. Competition and strategy in the pharmaceutical indus-try. Delft: Eburon; 1995 (in Dutch).

[17] Van den Bosch FAJ, de Man AP. Government’s impact on the business environment and strategic management. Journal of General Management 1994;3:50–9.

[18] Brandenburger AM, Nalebuff BJ. Co-opetition. New York: Doubleday; 1996.

[19] van der Windt W, Calsbeek H, Hingstman L. Verpleging en ver-zorging in kaart gebracht 1998. Utrecht: LCVV/De Tijdstroom; 1998 (in Dutch).

[20] Hingstman L, Kenens R, van der Windt W, Talma HF, Mei-huizen HE, Josten EJC. Report labour market health and welfare 2002. Tilburg/Utrecht: Nivel/Prismant/OSA; 2002 (in Dutch). [21] Groot I, Kok L (CEO), Aerts H (Sinzheimer Instituut). Health

professionals without security. The labour market position of freelancers in health care and of employees of people with a Personal Budget (in Dutch). Tilburg: OSA; 2003.

[22] Landelijke Vereniging voor Thuiszorg (LVT) en Cen-traal Bureau voor de Statistiek (CBS). Jaarboek Thuiszorg 1999–2000. Voorburg/Heerlen: CBS; 2002 (in Dutch). [23] Breedveld EJ, Batenburg RS. Structural changes and strategic

behaviour: the Dutch home care sector1985–1997. In: Schrui-jer S, editor. Multi-organizational partnerships and coopera-tive strategy. Tilburg: Dutch University Press; 1999. p. 155– 61.