Proceedings of

AR and VR Conference:

Perspectives on Business

Realities

27

th

of April 2016

Dublin Institute of Technology

2

AR and VR Conference: Perspectives on Business Realities

CALL FOR PAPERS

Co-Hosts:

School of Hospitality Management and Tourism, Dublin Institute of Technology Creative AR Hub, Hollings Faculty, Manchester Metropolitan University

Cutting-edge technologies are changing the business landscape and new innovations provide opportunities for businesses and destinations to offer unique services to their customers ranging from the overlay of digital content into users direct environment, gamifications, 3D printing etc.

The Perspectives on Business Realities of AR and VR conference organisers seek original, high‐quality papers in all areas related to augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), mixed reality and 3D user interfaces.

All paper submissions must be in English and submitted as a word file. The extended abstract should include: 1. Introduction; 2. Literature review; 3. Methods (if appropriate); 4. Findings; 5. Discussion and Conclusion. There are no strict formatting requirements however, APA referencing needs to be applied. The document file should not contain information that unnecessarily identifies the authors, their institutions, or their places of work. A separate cover sheet (work title, name, institution and contact details) should be submitted to ensure a double-blind review process. Selected papers will be published in the on-line journal (Journal of Augmented and Virtual Reality: Special Issue-Perspectives on Business Realities of AR and VR)

Paper length: Max. 1000 words extended abstract SUBMISSION DEADLINE:

15th March 2016

Papers must be submitted to [email protected]

For more information, please contact:

Academic conference chair: Dr. Timothy Jung (Manchester Metropolitan University)

Program chair: Dr. M. Claudia tom Dieck (Manchester Metropolitan University) [email protected]

Program convener: Alex Gibson (Dublin Institute of Technology) [email protected]

3

Conference Team

Dr. Timothy Jung

Dr. Timothy Jung is the Director of Creative Augmented Realities Hub

(www.creativear.org) at Manchester Metropolitan University, UK and

he is currently managing various Augmented and Virtual Reality

projects in the Tourism and Creative Industry. He has been involved

in a number of funded research projects at national and international

level. His current research focuses on the application of mobile and

wearable Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, mixed reality retail

experience, multi-sensory visitor experience in cultural heritage

tourism and smart tourism. Other research interests include social

media, mobile marketing and Cittaslow & Slow Food Movement.

Dr. Mandy Claudia tom Dieck

Dr. M. Claudia tom Dieck is specialised in tourism and hospitality

management with a strong focus on digital tourism including social

media and augmented reality. Coming from a hospitality background,

with an education from a leading Swiss hotel management school, she

worked in hotels in Malaysia and Germany. Her academic career

continued at Manchester Metropolitan University, completing her

Master in digital tourism and her PhD with a focus on social media and

customer relationship management. Mandy is Academic Editor of the

International Journal of Applied Augmented and Virtual Reality.

Alex Gibson

Alex Gibson is a Senior Lecturer in Marketing at the School of

Hospitality Management and Tourism, Dublin Institute of Technology.

He is a former President of Hospitality Sales and Marketing

Association HSMAI (Ireland) and has served on that organisation's

Europe Board. He is a member of the International Society of

Hospitality Consultants. He is the founder of the ARVR Innovate

Conference and Expo, which is a leading conference for practical

business applications of AR and VR. He has previously researched

and consulted on augmented reality projects for museums and hotel

4

Mary O’Rawe

Mary O’Rawe lectures in Management and Innovation Management in

Dublin Institute of Technology’s School of Hospitality Management

and Tourism. She has been involved in teaching, research and

supervision at undergraduate and graduate level for over 20 years,

and is a member of the visiting faculty team at ESSEC Business

School (IMHI), Paris. Mary has developed a number of creative

teaching and learning initiatives around enhancing student

engagement and learning, and has received a number of awards for

these. Mary works with industry to build relevant course material, and

Perspectives on Business Realities of AR and VR Conference Programme

27

thApril 2016, Dublin Institute of Technology, Cathal Brugha Street Campus

14.30 – 15.00 Registration and tea/coffee DIT Cathal Brugha Street, Foyer

15:00 – 15:15 Welcome - Dominic Dillane: Head of School, Alex Gibson: Dublin Institute of Technology, Timothy Jung: Academic Conference Chair 15.15 – 15:45 Industry Keynote Speaker 1 – Scott Hope, Commercial Director at AR Experiential Ltd

15:45 – 16:45 Paper Presentations Session 1 – Room 13

Moderator: Timothy Jung

Designing Virtual Reality for Sport: Some Crucial Considerations - Andy Miah

Eye-tracking Mobile Augmented Reality - Ann McNamara

Improving the customer experience in retail locations: The Game of Towns - Cathy Parker, Simon Quin, Nikos Ntounis, Steve Millington, Dominic Medway, Cathy Urquhart, Ed Dargan & Ben Keegan

16:45 – 16:55 Break

16:55 – 18:15 Paper Presentations Session 2 – Room 13

Moderator: Mandy tom Dieck

Session 3 – Boardroom Moderator: Mary O’Rawe Augmented Reality and Image Recognition Technology in Tourism: Opportunities and Challenges –

Caroline Scarles, Matthew Casey & Helen Treharne

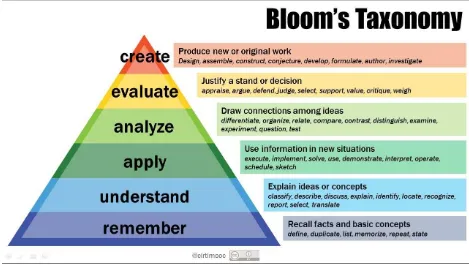

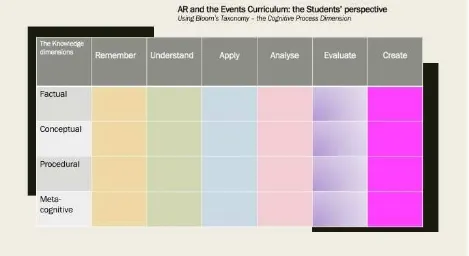

Augmented Reality and the Events Curriculum: The Students’ Perspective - Alex Gibson & Mary O’Rawe

Impacts of Augmented Reality Applications to Service Quality of Professional Tour Guides: The Case of Historical Museums –Ozlem Tekin

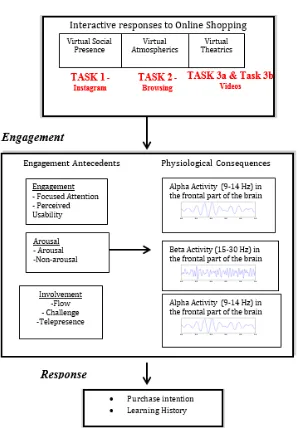

Virtually realistic? Analysing Consumer Engagement to Interactive Online Environments: An EEG study – Meera Dulabh, Delia Vazquez, Alex Casson & Daniella Ryding

Sonic Immersion in Mixed Reality Environment - Pasi P. Tuominen Implementing Augmented Reality to Increase Tourist Attraction Sustainability –Ella Cranmer, Timothy Jung, M. Claudia tom Dieck & Amanda Miller

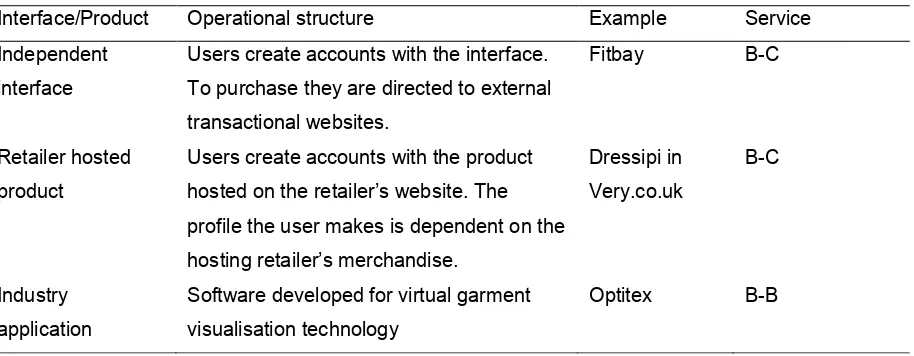

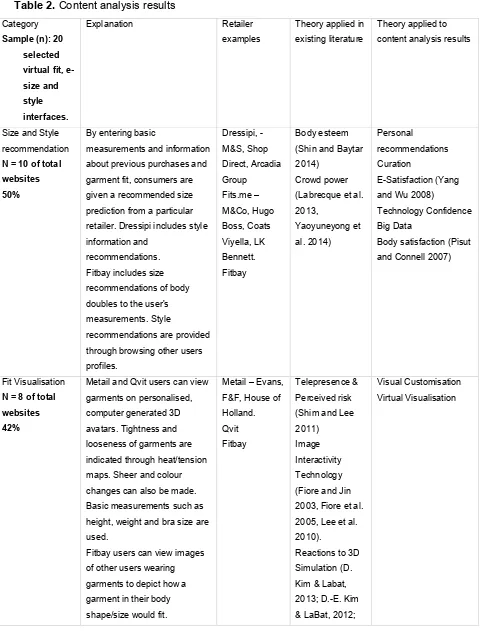

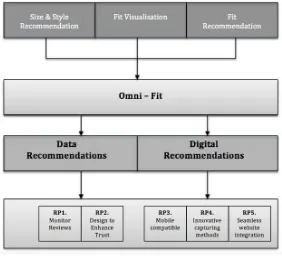

Augmented Reality as a Tool to enhance the Experience of Museum Visitors -Larissa Neuburger Modelling virtual size, style and fit conversion tools in online fashion retailing - Sophie Miell, Delia Vazquez & Simeon Gill

18.15 – 18:45 Industry Keynote Speaker 2 – vStream

18:45 – 19:00 Conference closing and introduction to ARVR Innovate –Timothy Jung & Alex Gibson 19.00 – 20:00 Wine reception

20.00 - late Finish and optional Dublin Dine Around, Le Bon Crubeen, 81-82 Talbot Street

6

Session 1

7

Designing Virtual Reality for Sport: Some Crucial Considerations

Professor Andy Miah, University of Salford

Extended Abstract

Intelligent exoskeletal devices (data gloves, data suits, robotic prostheses, intelligent second skins, and the like) will both sense gestures and serve as touch output devices by exerting forces and pressures….Exercise machines increasingly incorporate computer -controlled motion and force feedback and will eventually become reactive robotic sports partners....Today's rudimentary, narrowband video games will evolve into physically engaging tele-Sports' (Mitchell 1995: 19).

Mitchell’s vision of future human-computer interactions was one of the first instances to imagine a closer relationship between sports and digital technology. His vision of a world where ‘intelligent exoskeletal’ devices augment the range of human functions and the sensory experiences we enjoy, resonated with the direction sports were taking towards greater utilization of digital technologies. Moreover, back in the late 1990s, the growing synthesis of digital and biological systems was beginning to reveal new possibilities for experiencing our own corporeal presence and one could begin to see how this would create new kinds of performance possibilities, not just in sports, but in music and dance too.

Small changes in established sports were also suggesting how the structural parameters of sports were not sufficiently robust to accommodate the changing biological capacities of the techno-scientific athlete – athletes whose careers have been shaped by insights from sport science and technology. While sports considered how to modify their games to maintain their competitive integrity, Mitchell imagined a world composed of new kinds of sports, where 'remote arm-wrestling, teleping-pong, virtual skiing and rock-climbing' (ibid), were developed as a feast of cyborgian experiences, made for humanity’s growing bionic capacities.

8 interface has relevance for how one imagines the future sport. Stelarc’s exoskeletal machines and digitally immersive devices speaks our posthuman future, where artificial intelligence converges with robotics and where new forms of human agency bring forth new ways of experiencing embodied action. Back in the 1990s, many of these possibilities were realized only within the creative performances of artists like Stelarc, writers like Gibson (1984) and scholars like Mitchell (1995). While some of the ideas seem crude today, when they were first articulated, rapid accomplishments in digital technology were beginning to show how such scenarios could soon be realized. At the same time, the development of digital technology by a new generation of netizens was provoking a shift in how people consumed media and a rising population of 'prosumers' (Toffler 1970) was beginning to emerge. These new digital communities were more concerned with producing digital media content, than consuming it and this growing agency around technology is a key factor in explaining why these possible futures are compelling. As digital devices and sports cultures develop, humanity comes ever closer to an era of digitally constituted sports performances, where the primary medium of participation is no longer a physical playing field, but a digitally mediated space, a virtual reality.

Consider the recently launched Oculus Rift experience produced by ‘Virtually Live’, which uses motion-tracking technology to capture the movements of players within a live football match. It then translates this data into an Oculus experience, allowing the user to feel as though they are a spectator within the stadium, sitting in the stands watching the match in real-time. A number of questions arise from these prospects. For example, how would such conditions change sports experiences, physical activity, and people’s sense of what it is to be embodied? How would they change the social meaning attributed to sports, its social function, and the way in which it creates participatory communities? Would sports begin to occupy a different place within our social and cultural lives? Furthermore, what are the consequences of making corporeality a surrogate to a virtual economy, thus creating a physical culture that is defined largely by digital interactions? Would we even make the distinction when the level of sophistication is a perfect simulation?

10

Improving the customer experience in retail locations: The Game of Towns

Professor Cathy Parker, Institute of Place Management, Manchester Metropolitan University Simon Quin, Nikos Ntounis, Steve Millington, Dominic Medway, Cathy Urquhart, Ed Dargan and Ben Keegan

Extended Abstract

Internet shopping, which has been hailed as the ultimate level of retail decentralisation, along with the economic recession of 2008 and temporally concentrated lease expiry dates, have created the “perfect storm” for retail centre restructuring (Wrigley and Lambiri, 2015). Consequently, more city and town centres are changing, adapting to the new technology demands of today’s omni -channel consumer. However, as was the case with out-of-town developments a couple of decades ago (Clarke et al, 2007) not all centres fare well with this change. Medium-sized traditional town centres in particular are struggling and continue to under-perform, enduring high vacancy rates, victims from both out-of-town developments, Internet retailing, economic problems, policy restrictions, poor retail diversity, and outdated infrastructures that are irrelevant to today’s consumers. What is also evident is the continuous polarisation between north and south; Wrigley and Dolega (2011) noted that town centres in the south east and London are most likely to display resilience to the shocks of economic downturn and since then, this resilience has been portrayed in low vacancy rates percentages compared to the northern town centres (LDC, 2014). Many smaller centres, outside of London and the South East are therefore providing a very poor customer experience to shoppers. And improving the customer experience in these type of locations is the fundamental problem we want to address.

11 types of customer experience (Hallsworth, et al, 2015). We found a relationship between a distinct town type and constant or increasing footfall. This is customers 'voting with their feet' being attracted to centres that offer them the experience they require. Retailers located in places that attract more footfall perform better; there is a “strong correlation between spend and footfall" (Springboard, 2013).

To date, many retailers have not seen a need to cooperate in specific locations. “As each firm follows its own agenda and goals and may not see itself part of a larger, value-added channel” (Van Bruggen et al., 2010). To enhance the overall customer experience, retailers need to cooperate and strengthen the attractiveness of the places in which they are located (markets, the High Streets, shopping centres etc). Our proposal is to facilitate and quantify the value of collaboration, demonstrating the relationship between collective customer experience and individual retail performance through a new, easy-to use, simulated interface (a footfall optimiser), that brings information on town type, customer experience, customer demographics, etc. to individual decision makers, from retailers to place managers, enabling them to adjust their operations to meet local preferences, optimising both the customer experience and their own business performance. Algorithms and equations developed in the research stage of the project will be used to develop software that will predict and monitor the impact of interventions (such as changes to car-parking charges, opening hours, or resident population, etc.) on customer experience levels. This will bring complicated data analysis techniques to all town centre stakeholders, so that they can collectively decide strategies and interventions to optimise performance.

12 in many locations (e.g. speciality and convenience), and, towns that deliver a more coherent collective experience perform significantly better (in footfall terms) than those that do not. “It is vital to understand how centres are used, by whom and when” (CLG 2005, 2009). Footfall is already a key tool for implementation of established government policy supporting vital and viable town centres (e.g. PPG6, NPPG8, PPS5, PPS6, NPPF). Therefore, the interface will use footfall and other evidence (customer experience and retail sales) to understand different town types and provide more evidence to business and locations of the benefits of providing a more collective and coherent customer experience. Previous research (Parker et al, 2014) identified the 25 collaborative actions that will have most impact on town centre performance (vitality and viability), and these will be tested in 8 locations through The Game of Towns to facilitate their collective adoption and monitor impact. Impact will be measured through on-going consumer ratings of the retail/town experience, footfall and the financial performance of stores (establishing the relationship between certain types of collaborative activities and retail sales).

References

BCSC (2013). Beyond Retail, BCSC London.

Clarke I, Bennison D, and Pal J. (1997), Towards a contemporary perspective of retail location. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. 25(2), 59–69.

Experian (2012), Town Centre Futures 2020, http://www.experian.co.uk/assets/business-strategies/white-papers/town-centre-futures-whitepaper.pdf

Hallsworth, A, Ntounis, N, Parker, C and Quin, S, (2015). Markets Matter: Reviewing the Evidence and Detecting the Market Effect. Institute of Place Management. Manchester. http://www.placemanagement.org/media/19883/markets-matter-final.pdf

Parker, C, Quin, S. and Ntounis N, (2014). HSUK2020 25 priorities for Action, www.placemanagement.org/media/20731/top-25-priorities.pdf

Springboard, (2013). Retail Performance in the Changing Environment, http://www.spring-board.info/uk/reports/changing-retail-environment

Van Bruggen GH, Antia KD, Jap SD, Reinartz WJ, Pallas F. (2010). Managing marketing channel multiplicity. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 331–40.

Wrigley N., and Dolega L., (2011). Resilience, fragility, and adaptation: new evidence on the performance of UK high streets during global economic crisis and its policy implications.

13 Wrigley N, Lambiri D. (2015). British High Streets: from Crisis to Recovery? A Comprehensive

14

Eye-tracking and Mobile Augmented Reality

Dr. Ann McNamara, Texas A&M University

Introduction

Augmented Reality (AR) systems provide an enhanced vision of the physical world by integrating virtual elements, such as text and graphics, with real-world environments. AR allows us annotate the physical world with virtual information to enhance our understanding, enjoyment and usefulness of our immediate surroundings. The advent of affordable mobile technology has sparked a resurgence of interest in mobile AR applications. A fundamental problem is the optimal integration of real and virtual elements to provide a seamless user-integration paradigm.

This research is mid-way through a five-year project and (1) develops principled algorithms for optimized integration of real and virtual elements in mobile AR based on user-attention.

Integrating real and visual elements is a challenge because augmented elements, or labels, are contextually linked to real world objects or locations. To ensure the correct associations between virtual elements and real objects the augmented elements must be placed in the vicinity of the object it describes. Enforcing these spatial associations can lead to undesirable results: labels can overlap each other rendering them unreadable and, labels can obscure real world objects that are relevant to the user. Optimal placement of labels is an active area of research. This research evaluates the benefits of identifying where the user is looking and placing information in that location only.

Eye-tracking is used to determine both where the user is looking and to guide optimal label placement by only displaying virtual elements associated with real objects that the user attends to.

Literature Review

15

and Ellis, 2008b, Polys, Kim, and Bowman. 2005). While several

solutions have been proposed including greedy algorithms, cluster-based methods and screen subdivision methods (Rosenholtz, Li, Jin, and Mansfield. 2006, Rosenholtz, Li and Nakano. 2007, Tenmoku, Kanbara and Yokoya. 2005, Uratani and Takemura. 2005, Wither, DiVerdi, and Hollerer, 2009), we know of no other research that uses information about where the user is looking in the scene to place augmented elements in the scene.

Our research uses gaze position as the determining factor. There are clear benefits to doing so. By presenting label boxes only in the region the user looks minimizes the number of elements to display thereby minimizing the risk of overlap. Without risk of overlap clear associations with anchors can be ensured and once the user re-directs their gaze the label boxes in the unattended region do not need to be displayed, thereby minimizing the proportion of the real world that is obscured. The solution presented here uses a combination of screen position and eye-movement to ensure that label placement does not become distracting.

Methods

We are investigating candidate strategies for information (AR label) placement. Methods range from simply displayed all information available to methods that are a function of the distance between the object of interest and the gaze position. We are currently conducting pilot experiments on LCD screens with imagery sizes set to match that of mobile devices.

Participants are seated in front of a computer screen in a well-lit room. Using a FaceLa b Remote EyeTracking Device operating at 60 Hz with gaze position accuracy < 0.5 degrees, data pertaining to fixation position and saccades are recorded for each participant. After a brief calibration phase, three test images are used to familiarize the participant with the interface.

16 differently depending on the method used. So far we have only run the experiments on a typical LCD display, but image size matched that of a hand held device (iPhone).

Discussion and Conclusion

We have found that using gaze-control results in slightly faster response times and with higher accuracy when users perform a simple information retrieval task. The biggest advantage of a gaze based strategy however, is the fact that the method eliminates all but a single label so that the rest of the real scene is not as occluded. This is particularly useful when an application requires information delivery from multiple objects in a scene. View management schemes should aim to minimize the portion of the actual scene that is covered in the application. While this is not always possible, the strategy introduced here of revealing information for the objects the user is looking at provides a cleaner interface.

To date we have developed methods that use an observers’ gaze to influence the placement of virtual labels on a display. By monitoring the eye position of the user we are able to present only the most relevant information without over populating the screen space. This approach leaves more of the actual scene visible. This is particularly important when dealing with mobile AR applications using peripherals with limited screen space. The results of an experiment show that this approach to gaze directed AR is highly effective

Evaluating mobile AR with eye tracking of the laboratory setting will be challenging. We are currently developing and deploying our algorithms to present information in a more intuitive manner directly onto mobile devices, such as the Apple iPad and Google Tango.

While using a front facing camera on the iPad or Tango is not yet possible there are potential approaches to combat that such as using an external camera or eye tracker (such as eyeTribe), or using emerging wearable eye trackers such as those recently launched by SMI and Tobii.

17 such as feature congestion and image saliency to predict when our method would work best. For example, if there is not much information to display, and the virtual information presented does not obstruct the real scene in a disruptive manner there may be no need to employ any selection strategy. Feature Congestion and Saliency maps could also provide clues on the arrangement of objects in a scene and whether or not a view management strategy is necessary.

References

Peterson, S.D., Axholt, M., Cooper, M. and Ellis, S.R. (2009). Visual clutter management in augmented reality: Effects of three label separation methods on spatial judgments. Paper presented in 3D User Interfaces, 2009. IEEE Symposium on, Lafayette, LA.

Peterson, S.D., Axholt, M. and Ellis, S.R. (2008a). Comparing disparity based label segregation in augmented and virtual reality. In Proceedings of the 2008 ACM symposium on Virtual reality software and technology (VRST ’08). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 285–286.

Peterson, S.D., Axholt, M. and Ellis, S.R. (2008b). Label segregation by remapping stereoscopic depth in far-field augmented reality," Mixed and Augmented Reality, 2008. ISMAR 2008. 7th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on, Cambridge, 2008, pp. 143-152.

Polys, N.F., Kim, S. and Bowman, D.A. (2005). Effects of information layout, screen size, and field of view on user performance in information-rich virtual environments. In Proceedings of the ACM symposium on Virtual reality software and technology (VRST ’05). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 46–55

Rosenholtz, R., Li, Y., Jin, Z. and Mansfield, J. (2006). Feature congestion: A measure of visual clutter. Journal of Vision, 6, 1-15.

Rosenholtz, R., Li, Y. and Nakano, L. (2007). Measuring visual clutter. Journal of Vision, 7(2), 17-17.

Tenmoku, R., Kanbara, M. and Yokoya, N. (2005). Annotating User-Viewed Objects for Wearable AR Systems. In Proceedings of the 4th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR ’05). IEEE Computer Society, Washington, DC, USA, 192–193. Uratani, K. and Takemura, H. (2005). A Study of Depth Visualization Techniques for Virtual

Annotations in Augmented Reality. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Conference 2005 on Virtual Reality (VR ’05). IEEE Computer Society, Washington, DC, USA, 295–296.

Wither, J., DiVerdi, S. and Hollerer, T. (2009). Annotation in outdoor augmented reality.

18

Session 2

19

Augmented Reality and Image Recognition Technology in Tourism: Opportunities and

Challenges

Dr Caroline Scarles, University of Surrey Dr Matthew Casey, Pervasive Intelligence Ltd

Dr Helen Treharne, University of Surrey

Abstract

Technology and tourism have a long legacy as reflected upon by Buhalis & Law (2008; 2014). Within this, mobile technology and augmented reality (AR) has come to the fore more recently within the last five years (e.g. Pesonen & Horster, 2012; Yovcheva et al 2012; Linaza et al 2012; Wang et al, 2012). However, while AR has been developed in a range of contexts, the focus of this paper lies in the role it plays in enhancing the visitor experience within arts and heritage tourism. This paper critiques the opportunities AR affords in enriching the visitor experience whilst recognising the pressures cultural organisations face in developing creative and innovative ways of displaying and interpreting artefacts. Secondly, it presents the challenges of producing a technology that supports an intuitive, easy to use multi-media guide for interpretation in a cost and resource efficient manner.

Keywords: augmented reality, image recognition, technology, visitor experience

Introduction and Literature Review

20 multimedia formats, on top of the real-world view…In other words, AR can augment one’s view and transform it with the help of a computer or a mobile devise, and thus enhance the user’s perception of reality and of the surrounding environment” (: 1). However, while AR has been developed in a range of contexts such as DMOs and city adventures (ibid.), the focus of this paper lies in the role AR plays in enhancing the visitor experience within arts and heritage tourism.

Interpretation and the visitor experience in arts and heritage spaces has been researched extensively (see for example: Fleck et al, 2002; Graburn, 1977; Moscardo, 1996). However, the role of digital within this has only recently received increased attention (e.g. Charitonos et al, 2012; Silverman, 2010). Museums and art galleries are coming under increasing pressure, through visitor expectation and direct competition with other institutions, to introduce digital content to enrich user engagement. As such, the sector has witnessed a recent surge in interest

21

Methods

Working directly with key partners, namely The Lightbox (Woking, Surrey), Brooklands Museum (Weybridge, Surrey), Watts Gallery (Compton, Surrey), Historic Royal Palaces and Visit Surrey, this research emerges from a wider project that encompasses the development of technology supporting the provision of digital solutions within arts and heritage environments. Findings emerge from 40 interviews that were conducted as part of live public trials of the “Let’s Explore” mobile application. The purposive sample was identified at the key trial sites of Watts Gallery and The Lightbox. Interviews were then transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis.

Findings and Discussion

Firstly, recognising the pressures cultural organisations face in developing creative and innovative ways of displaying and interpreting artefacts, this paper presents “Let’s Explore” as a low-cost solution for cultural organisations to deploy and maintain their own content without relying upon bespoke development. While many technologies exist (i.e. QR codes, iBeacon), it uses image recognition technology to trigger interpretation of artefacts once they are detected. While this is a well-established technology, many technical challenges persist in exhibition spaces (i.e. lighting and glare). Indeed, while commercial 2D recognition solutions work well on image targets with sufficient contrasting features, such as posters, photographs and paintings, technology remains incapable of detecting images with very limited features. This paper explores solutions to this and extends findings into 3D object recognition through key point analysis.

Secondly, the paper presents the challenges of producing a technology that supports an intuitive, easy to use multi-media guide for interpretation in a cost and resource efficient manner. It reflects on the importance of ensuring technology can be managed by organisations to ensure flexibility and control in managing app content and considers “Let’s Explore” as a flexible technology framework that facilitates such autonomy. This requires an understanding of the existing limited capacity and resources of smaller/regional organisations that rarely have a technology infrastructure to support Wi-Fi in their exhibition spaces.

22 organisations face to develop and expose greater levels of information during exhibition design. For example, findings suggest visitor intrigue is stimulated not only by curatorial data, but also vignettes of contemporary history which may not be readily available in existing digital repositories.

References

ALVA (2015). ALVA | Association of Leading Visitor Attractions. Available at: http://alva.org.uk/. [Accessed July 2015.]

Buhalis, D. & Law, R. (2008). Progress in Information Technology and Tourism Management: 20 years on and 10 years after the internet – The state of eTourism research, Tourism Management, 29, 609-623.

Charitonos, K., Blake, C., Scanlon, E. & Jones, A. (2012). Museum Learning via Social and Mobile Technologies: (How) can online interactions enhance the visitor experience?, British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(5), 802-819.

Collections Trust (2014). Digital Strategy. Available at: http://www.collectionstrust.org.uk/digital-strategy. [Accessed July 2015.]

Davis, J. (2011). Art & Artists. Museums and the Web, 2011. Available at:

http://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw2011/papers/art_artists. [Accessed July 2015.] Fiore, A., Mainetti, L., Manco, L. & Marra, P. (2014). Augmented Reality for Allowing Time

Navigation in Cultural Tourism Experience: A Case Study, Augmented and Virtual Reality, 8853, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 296-301.

Fleck, M., Frid, M., Kindberg, T. & Rajani, R. (2002). From Informing to Remembering: Deplaying a Ubiquitous System in an Interactive Science Museum, Hewlett Packard Company, hp Invent.

Graburn, N. (1977). The Museum and The Visitor Experience, Roundtable Reports, Fall, 1-5. Kounavis, C.D., Kasimati, A.E. & Zamani, E.D. (2012). Enhancing the Tourism Experience

through Mobile Augmented Reality: Challenges and Prospects, International Journal of Engineering Business Management, 4, 1-6.

23

Linaza, M.T., Marimon, D, Carrasco, P., Alvarez, R., Montesa,

J., Aguilar, S.R. & Diez, G. (2012). Evaluation of Mobile Augmented Reality Applications for Tourism Destinations. In Fuchs, M et al (eds). Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, Springer, Heidelberg.

Moscardo, G. (1996). Mindful Visitors: Heritage and Tourism, Annals of Tourism Research, 23(2), 376-397.

Pesonen, J. & Horster, E. (2012). Near Field Communication Technology in Tourism, Tourism Management Perspectives, 4, 11-18.

Rojas, C. & Camarero, C. (2008). Visitors’ Experience, mood and satisfaction in a heritage context: evidence from an interpretation centre, Tourism Management, 29, 525-537. Silverman, L. (2010). Visitor Meaning-Making in Museums for a New Age, Curator: The Museum

Journal, 38(3), 161-170.

Stack, J. (2013). Tate Digital Strategy 2013–15: Digital as a Dimension of Everything. Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/tate-digital-strategy-2013-15-digital-dimension-everything. [Accessed July 2015.]

Visit England (2013). Domestic Leisure Tourism Trends for the Next Decade. Available at:

https://www.visitengland.com/sites/default/files/visit_england_report_print_tcm30-39493.pdf. [Accessed July 2015.]

vom Lehn, D. & Heath, C. (2005). Accounting for New Technology in Museum Exhibitions,

Marketing Management, 7(3).

Wang, D., Park, S. & Fesenmaier, D.R. (2012). Journal of Travel Research, 51(4), 371-387. Wang, D. & Fesenmaier, D.R. (2013). Transforming the Travel Experience: The Use of

Smartphones for Travel. In Proceedings of the International Conference in Innsbruck,

Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2013, (pp.58-69), Springer, Heidelberg.

Wang, D., Xiang, Z. & Fesenmaier, D.R. (2014). Smartphone Use in Everyday Life and Travel,

Journal of Travel Research, 1-12.

Wei, S., Ren, G. & O’Neill, E. (2014). Haptic and Audio Displays for Augmented Reality Tourism Applications, Haptics Symposium (HAPTICS), 2014.

Yovcheva, Z. (2015). User-centered Design of Smartphone Augmented Reality in Urban Tourism Context, Doctoral Thesis, Bournemouth University, 2015. Accessed online at:

24

Yovcheva, Z., Buhalis, D. & Gatzidis, C. (2012). Overview of

Smartphone Augmented Reality Applications for Tourism, e-Review of Tourism Research (eRTR), special issue – ENTER 2012 exchange idea, Vol.10(2), 63-66.

25

Impacts of Augmented Reality Applications to Service Quality of Professional Tour

Guides: The Case of Historical Museums

Ozlem Tekin, Necmettin Erbakan University

Abstract and Introduction

Technological innovations used by proffesional tour guide’s expressions in museum have been examined in this study. The impacts of AR applications to the quality of guidance service have been evaluated. The Museum of Mausoleum of Ataturk in Ankara/Turkey using AR innovations has been selected as research field. The interview questions have been composed after reading related literature, and semi-structured interviews have been conducted with tourists.

Keywords:

Professional Tourist Guide, Museum Guidance, Technological Innovations, AR,Service Quality.

Literature Review

The Concept of AR

AR can be defined as a technology that provides more enriched environment by means of including objects like 3D model in real time, animation, film, audio on a real image in current environment. Created image can be displayed as if they were almost in real world with the AR applications (Javornik, 2016; 253). The emergence of AR applications has changed the way tourist’s experience in a destination, leading to more interactive and diversified experiences (Fritz, Susperregui, & Linaza, 2005; Kourouthanassis et al., 2015). AR applications provide tourists with the opportunity to get to know unknown surroundings in an enjoyable and interactive manner (tom Dieck and Jung, 2015). The increased situational awareness for tourists gained from linkages of information and real world elements has been utilized in many fields.

26

of culture and heritage with the potential to bring history to life

(Höllerer and Feiner, 2004; Fritz, Susperregui, & Linaza, 2005).

Professional Tour Guidance

A person who guides visitors in the language of their choice and interprets the cultural and natural heritage of an area which person normally possesses an area-specific qualification usually issued and/or recognised by appropriate authority (www.wftga.org, 2016).

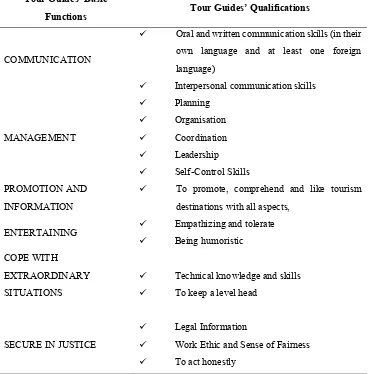

Table 1.Basic Functions and Qualifications of Tour Guides’ (Yildiz vd., 1997):

Methods

“Semi-structured interview” technique has been used in this research, which one of in – depth interview of qualitative research methods (Ekiz, 2003). The primary questions consist of open-

Tour Guides’ Basic

Functions Tour Guides’ Qualifications

COMMUNICATION

Oral and written communication skills (in their own language and at least one foreign

Work Ethic and Sense of Fairness

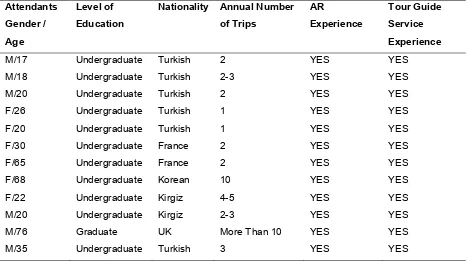

27 ended and neutral questions. The secondary questions consist of closed- ended questions to make obvious the results of analysis of the research (Yildirim and Simsek, 2013). The interviewer begins with an open-ended question and each subsequent question follows as a gradual path narrowing the scope of questions to get specific information in funnel method (Yuksel et al., 2007). Interviews are composed of domestic and foreign tourists coming to Mousoleum of Ataturk. Within this research, it is asked if tourists have experience of a tour guided vacation and an AR application. The semi-structured interviews have been carried out with tourists who have two of these experience. Datas were collected on February, 2016. Interviews were terminated when collected the data obtained after interviews with 12 tourists because answers were in the same direction. Participants consists five nationalities including Turkish, France Korean, Kirgiz and British. The interviews lasted between approximately 15-30 minutes for each participant. Reseacher has taken note of the datas obtained during conversations.

Findings

Interviewers have been named in the age and gender category with the information of services they have purchased are shown in Table 2:

Table 2. Datas on visitors who were interviewed

28 Remarkable response about effects of usage AR applications to guidance service during museum visits as follows:

‘I’m expecting detailed information and promotion about destination from tour guides.’ ‘I can see historical artifacts as reconstructed with the help of AR application’s 3D feature.’ ‘AR applications make easy to interpret tangible and intangible informations and make tour guide’s presentation visualised.’

‘Presentations with AR applications are more remindful.’

Tourists are expecting detailed, accurate and impartial information and promotion service about destination from tour guides. And they are expecting a tour guide service that informative about history. Mapped AR applications and animations with game, mobile phone based AR applications are often prefered by tourists. Especially 3D visual characteristic of AR applications is the reason of tourist’s intention of use. All of respondents think that AR applications have a possitive affect of tour guide’s presentation performance. Because AR applications make tour guide’s presentation visualised. So they allow a better understand about historical informations. In additon to infotmative feature, AR applications make tour activity entertaining. AR applications is a tool of interpret tangible and intangible informations. It is possible to give more remindful information with the help of AR applications. The other remarkable finding is that a few of respondents have used AR applications before travel. Most of them have prefered during travel. There was just basic level AR applications in Mausoleum Museum of Ataturk selected as study area. In this case, researcher had to explain features of AR applications including experienced tourists. Usage of AR in tourism is very rare in Turkey.

Discussion and Conclusion

29 applications, map based AR applications. Maybe, it can be another research topic about gender or education status and choice of AR applications type. The main conclusion of the research that AR applications make tour guides’ presentation visualised and make easy to interpret tangible and intangible information. The other important conclusion is AR applications can enable remindful & efficient presentations for tour guides. It is an important effect about a touristic destination marketing. Consumer satisfaction is main target of tourism organisations and the best promotion method is word of mouth marketing between tourists (Litvin et al., 2008).

The findings of research should benefit for tour guide service quality literature because a lot of study on service quality are quantitative (Parasuraman et al.,1988; Nowacki, 2005; Armstrong et al., 1997). A qualitative research on a focus group can contribute a different aspect.

References

Armstrong R. W. Mok C. Go F. M. ve Chan A. (1997). The Im¬portance of Cross-Cultural Expectations in the Measu¬rement of Service Quality Perceptions in the Hotel In¬dustry, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 16 (2), 181-190.

Ekiz, D. (2003). Introduction to Research Methods in Education, Ankara: Ani Press.

Fritz, F., Susperregui, A. & Linaza, M.T. (2005). Enhancing Cultural Tourism Experiences With Augmented Reality Technologies. 6th International Symposium on Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Cultural Heritage (VAST), Pisa, Italy, 8-11 November.

Garau, C. (2014). From Territory to Smartphone: Smart Fruition of Cultural Heritage for Dynamic Tourism Development. Planning Practice and Research, 29(3), 238-255.

Hollerer, T.H., & Feiner, S.K. (2004). Mobile Augmented Reality. In H. Karinzi, & A. Hammand (Eds.), Telegeoformatics: Location-based computing services (pp. 1-39). Florida: Taylor and Francis books Ltd.

Javornik, A. (2016). Augmented reality: Research Agenda for Studying the Impact of Its Media Characteristics on Consumer Behaviour. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 30, 252-261.

Kourouthanassis, P., Boletsis, C. Bardaki, C. & Chasanidou, D. (2015). Tourists Responses to Mobile Augmented Reality Travel Guides: The Role of Emotions on Adoption Behavior, Pervasive and Mobile Computing, 18, 71-87.

30 Nowacki M. M. (2005) Evaluating a Museum as a Tourist Pro¬duct Using the SERVQUAL

Method, Museum Manage¬ment and Curatorship, 20, 235-250.

Parasuraman A. Zeithaml V. A. ve Berry L. L. (1985). A Concep¬tual Model of Service Quality and Its Implications for Fu¬ture Research, Journal of Marketing, Fall, 49, 41-50.

tom Dieck, M.C. and Jung, T. (2015). A Theoretical Model of Mobile Augmented RealityAcceptance in Urban Heritage Tourism, Current Issues in Tourism. (ISSN: 1747-7603, Impact Factor: 0.918) DOI: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1070801.

Yildirim, A. And Simsek, A. (2013).Qualitative Research Methods in Social Sciences. Ankara: Seckin Press.

Yildiz, R., Kusluvan, S. ve Senyurt, Y. (1997). A New Model on Tourist Guide Education. Weekend Workshop IV: Türkiye’de Turizmin Gelistirilmesinde Turist Rehberlerinin Rolu, (7-36) Erciyes University Nevsehir Tourism and Hotel Management School. Kayseri: Erciyes University Press.

31

Augmented Reality as a Tool to enhance the Experience of Museum Visitors

Larissa Neuburger, Salzburg University of Applied Sciences

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to improve the situation of museums, as visitor numbers in the Federal Museums in Austria have been decreasing over the last few years (Standard 2012). Therefore museums have to change their previous strategy, rethink their approach and include new media technology to stay up to date in order to attract more visitors. Customers do not only want to be consumers but also wish to feel and immerse themselves in the product or service. They now demand information, entertainment, active participation and multisensory stimulation in combination with innovative design elements (Pine II and Gilmore, 2011). Having these thoughts in mind, the aim of this paper is to work with the experience approach, to combine this knowledge with the new technology of Augmented Reality (AR) and finally to explore if the experience of museum visitors can be enhanced using such ways. The following research question aim to address objectives of the paper and pose one overall question:

Does Augmented Reality have the potential to enhance the experience of visitors in museums?

Literature Review

32 have tried over the last years not only to be places of collection, conservation, research and communication but also have additionally become places of trust for the visitors (Barricelli and Golgath, 2014). The challenge of museums in the 21st century is their existence in the dual reality of tangible objects, digital technologies and social media (Falk and Dierking, 2013). AR “[…] describes the concept of augmenting a view of the real world with 2D images or 3D objects [...]” (Woods, et al., 2004). With advancements and developments over the recent years, AR can be seen as a flexible and practicable tool with high visual quality to overcome the problems of limited space or the high value of exposed objects and additionally support the quality of the museum content (Woods, et al., 2004; Noh, et al., 2009).

Methods

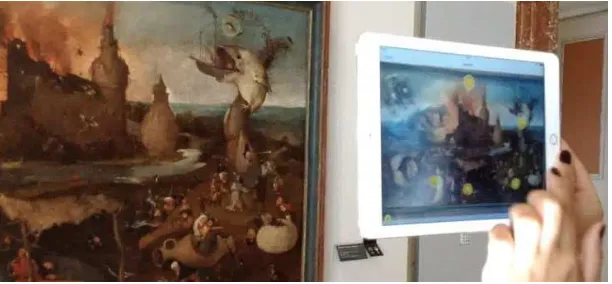

Based on the results of the literature, an empirical research study with an experimental design was conducted in order to strengthen the findings of the literature. Furthermore an AR prototype was developed to be able to test the experience enhancement of the museum visitors. The application was designed to provide background information on the selected artworks of the museum exhibition. An impression of the prototype can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Example picture AR application prototype, Source: Own illustration

33 exhibition with the help of the AR application prototype. Both groups had to fill out a questionnaire afterwards. For the empirical data analysis of this paper, the concept of measuring the experience is important. Therefore, the experience model of Pine and Gilmore (1999) is applied. The four realms of the model are operationalised in order to deduce suitable questions for the survey based on papers of Mehmetoglu and Engen (2011) and Oh et al. (2007). In order to also measure the special aspect of the museum experience, the concept of the Museum Experience Scale (MES) by Othman et al. (2011) was added to the survey. Also the different constructs of the MES were operationalized into suitable questions by adapting the original paper from Othman et al. (2011) to this research project.

Based on the research questions and the mentioned research models, the conducted experiment was used to verify following hypotheses:

H1: AR is enhancing the overall experience of the museum visitors.

H1 (a-d) is based on the experience model of Pine and Gilmore and representing the different constructs of the model Entertainment (H1a), Education (H1b), Escapism (H1c) and Esthetics (H1d).

H2: AR is enhancing the overall museum experience of the museum visitors.

H2 (a-d) is based on the Museum Experience Scale and also representing the different constructs Engagement (H2a), Knowledge (H2c), Meaningful Experience (H2c) and Emotional Connection (H2d):

In order to test the results of the groups on their differences, the independent t-test is used to compare the means of the different groups with the sample size of each � = . Thereby it is analysed if the differences only exist due to random fluctuations or if the differences are explicable significantly (Bühl, 2014). The items of the different constructs of the models were summed up to a common value for each construct. The different items of the questionnaire were tested with a 7-level Likert-Scale.

Findings

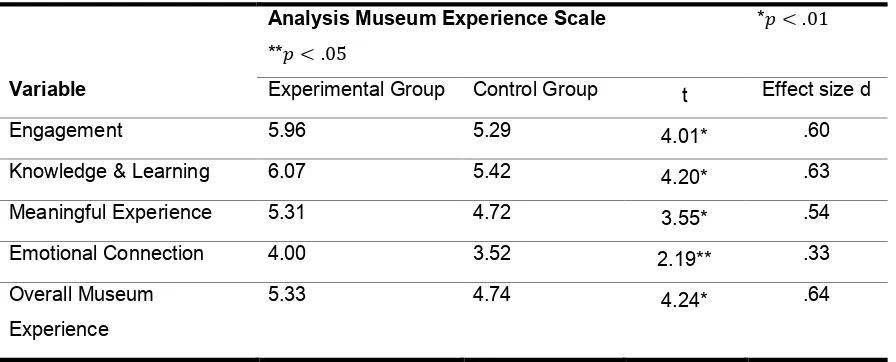

34 Escapism on a significance level of � < . . The results of the experiment group were higher and therefore show that AR enhanced the experience. Only the result of the construct Esthetics (H1d) could not show significant results. This can probably be explained through the external influencing factors concerning the location of the museum. The hypotheses of H2 (a-c) also show significant higher results in the experimental AR group in the constructs Overall Museum Experience, Engagement, Knowledge and Meaningful Experience again on the significance level of � < . . The construct of Emotional Connection (H2d) also shows significant results but only on a significance level of � < . 5. The values of the results can be seen in Table 1 and 2.

Table 1. T-Test Experience Scale

Analysis Experience Scale *� < . **� < . 5

Variable Mean Experimental Group

Mean Control

Group

t Effect size d

Entertainment 5.47 4.58 5.71* .86

Education 6.06 5.41 3.86* .58

Escapism 4.79 4.17 2.98* .45

Esthetics 5.79 5.51 1.65 .25

Overall Experience 5.53 4.92 4.36* .66

Table 2. T-Test Museum Experience Scale

Analysis Museum Experience Scale *� < . **� < . 5

Variable Experimental Group Control Group t Effect size d

Engagement 5.96 5.29 4.01* .60

Knowledge & Learning 6.07 5.42 4.20* .63

Meaningful Experience 5.31 4.72 3.55* .54

Emotional Connection 4.00 3.52 2.19** .33

Overall Museum

Experience

35

Conclusion

With the results of the conducted experiment in the Dommuseum Salzburg, it can be said that AR definitely has the potential to enhance the experience of museum visitors. The results show that the utilization of AR in the museum can enhance both the overall experience, and the overall museum experience. When broken down into the different realms and dimensions of the two tested models, it can be said that nearly all realms show significantly increased values of visitors using the AR application. Only the realms of Esthetics being part of the experience model and Emotional Connection as part of the Museum Experience Scale do not show significant values or only a very low effect size due to the special location of the museum next to the Cathedral of Salzburg and its special religious artefacts with their complex meaning. Beside that, it can be said that the museum visitors felt more entertained and engaged, gained more education and knowledge, could escape the real world and had a meaningful experience in the museum by using the AR application prototype.

36

References

Barricelli, M. and T. Golgath (2014). Historische Museen heute, Schwalbach: Wochenschau. Bühl, A. (2014). SPSS 22. Einführung in die moderne Datenanylse. 14th ed., Hallbergmoos:

Pearson.

Falk, J. and L. Dierking (2013). Museum Experience Revisited. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. John, H (2008a). Hülle mit Fülle. Museumskultur für alle – 2.0. In: John, H. and A. Dauschek,

(eds.) Museen neu denken. Perspektiven der Kulturvermittlung und Zielgruppenarbeit.

Bielefeld: transcript, 15–66.

Kipper, G. and J. Rampolla (2012). Augmented Reality: An Emerging Technologies Guide to AR, Waltham: Elsevier.

Mehmetoglu, M. and M. Engen (2011). Pine and Gilmore's concept of experience economy and its dimensions. An empirical examination in tourism. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 12 (4), 237–255

Noh, Z., Sunar, M. and Z. Pan (2009). A review on augmented reality for virtual heritage system. In: Chang, M. et al. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on E-Learning and Games: Learning by Playing. Gamebased Education System Design and Development. (5670) Banff, August 2009. Berlin: Springer, 50–61.

Oh, H., Fiore, A.M. and M. Jeoung (2007). Measuring experience economy concepts. Tourism applications. Journal of travel research, 46 (2), 119-132.

Othman, M.K., Petrie, H. and C. Power, (2013). Measuring the Usability of a Smartphone Delivered Museum Guide. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 97, 629–637. Pine II, B.J. and J.H. Gilmore (2011). The experience economy, Boston: Harvard Business Press. Pine II, B.J. and J.H. Gilmore (1999). The Experience Economy, Boston: Harvard Business Press. Sherman, A. (2011). How Tech Is Changing the Museum Experience. Mashable. [online] Available at: http://mashable.com/2011/09/14/high-tech-museums/ [Accessed 23 July 2015].

Standard (2012). Bundesmuseen verzeichneten 2011 einen Rückgang. [online] Available at: http://derstandard.at/1326502878492/Zwei-Prozent-Minus-Bundesmuseen-verzeichneten-2011-einen-Rueckgang [Accessed 20 November 2015].

37 Wojciechowski, R. et al. (2004). Building virtual and augmented reality museum exhibitions. In:

Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on 3D Web Technology, Monterey, CA, April 2004. New York: ACM, 135–187.

Woods, E. et al. (2004). Augmenting the science centre and museum experience. In: Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques in

38

Sonic Immersion in Mixed Reality Environment

Pasi P Tuominen, Haaga Helia University of Applied Sciences

Introduction

An emotional environmental element such as enjoyable music arouse desire which leads to loyalty, willingness to buy and recommendation (Baker et al., 2002; Kotler, 1974; Sherman et al., 1997; Wakefield and Brodgett, 1996). This abstract explains and builds a literature driven conceptual model for sonic immersion in a multi-sensory, mixed reality environment. Multi-sensory, mixed reality environments allow the control of multiple sensory stimuli, hence the scents, temperature, moisture level, sounds and the sights of the environment can be adjusted according to customer wishes or pre-programmed scenarios. (Tuominen and Heikkinen, 2014.)

Literature Review

39 There seems to be little consensus on the definitions of immersion (Brown and Cairns, 2004; Adams, 2004b), and the role of sound in the formation of immersion. For example, Rollings and Morris (2000) describe that sound is important for immersion because it is hardly noticed by the user. Van Leeuwen (1999) emphasise the role of ambient sound and postulates that the immersion occurs when sound is experienced and heard from all directions. In these circumstances, the listener becomes immersed and loses the ability observe the sound source and the auditory milieu. Immersion has been used often to describe the level of involvement in games, especially in virtual reality environments (Adams, 2003, p.58). Designers, and researchers also investigate the phenomenon of immersion as an important element of interaction (Brown & Cairns, 2004).

40

Discussion and Conclusion

The sensation of sound is linked to emotions and feelings (Lindström, 2005; Hultén, 2011) and these sensations impact brand experiences, interpretations, and that companies have great opportunities to create signature sound that symbolises the brand, creates sensory experiences and enhances recall. (Botteldooren et al., 2011; Pawaskar and Goel, 2014.) Signature sounds, according to Botteldooren (2011) and Pawaskar (2014) evoke the sensations and influences the emotive feelings influencing the brand experience. These sensory experiences enhance recall while symbolises the brand. Similarly to Van Leeuwen (1999), Henriques (2011) stated that ‘sonic dominance’, is the total immersion of the participants present in the experience. Therefore the vibration frequencies connect to the physiology of the participant, thus creating a deep level of immersion. Despite the earlier findings of the importance of the ‘sonic environment’, or the sonic immersion, there is no research involving virtual or mixed reality environment, especially in the context of hospitality and tourism. Therefore, besides classifying immersion in MREs, this project aims to measure, and finally define a model for sonic immersion (fig 1.) in a mixed reality environment, within tourism context.

References

Baker, J., Parasurman, A., Grewal, D., & Voss, G. B. (2002). The influence of multiple store environment cues on perceived merchandise value and patronage intentions. Journal of Marketing, 66(2), 120-141.

Botteldooren, D. (2011). Understanding urban and natural soundscapes. Proceedings of Forum Acusticum, 2047-2052.

Brown, E., & Cairns, P. (2004). A grounded investigation of game immersion. CHI'04 extended abstracts on Human factors in computing systems, 1297-1300. ACM.

41 Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tourism management, 29(4), 609-623.

Cruz-Neira, C., Sandin, D. J., DeFanti, T. A., Kenyon, R. V., & Hart, J. C. (1992). The CAVE: audio visual experience automatic virtual environment. Communications of the ACM, 35(6), 64-73.

Dovey, J., & Kennedy, H. W. (2006). Game cultures: Computer games as new media: computer games as new media. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Ermi, L., & Mäyrä, F. (2005). Fundamental components of the gameplay experience: Analysing immersion. Worlds in play: International perspectives on digital games research, 37. Ferreira, P. P. (2008). When sound meets movement: Performance in electronic dance music.

Leonardo Music Journal, 18, 17-20.

Gilmore, J., &. (1999). The Experience Economy: work is theatre and every business a stage.

Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Guerra, J. P., Pinto, M. M., & Beato, C. (2015, March). Virtual reality-shows a new vision for tourism and heritage. European Scientific Journal.

Henriques, J. (2011). Sonic bodies: reggae sound systems, performance techniques, and ways of knowing. USA: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Huang, H. M., Rauch, U., & Liaw, S. S. (2010). Investigating learners’ attitudes toward virtual reality learning environments: Based on a constructivist approach. Computers & Education, 55(3), 1171-1182.

Hultén, B. (2011). Sensory marketing: the multi-sensory brand-experience concept. European Business Review, 23(3), 256-273.

Kotler, P. (1973). Atmospherics as a marketing tool. Journal of Retailing, 49(4), 48-64. Leeuwen, T. v. (1999). Speech, Music, Sound. London: Macpress.

Lindstrom, M. (2005b). Brand Sense. Build Powerful Brands through Touch, Taste, Smell, Sight, and Sound. New York: Free Press.

Lorenz, M. B. (2015). I'm There! The influence of virtual reality and mixed reality environments combined with two different navigation methods on presence. Virtual Reality (VR), 223-224. IEEE.

42 the 26th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference on Designing Futures: the

Future of Design, 430-439.

Patrick, E., et al., (2000). Using a large projection screen as an alternative to head-mounted displays for virtual environments. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM.

Pawaskar, P., & Goel, M. (2014). A Conceptual Model: Multisensory Marketing and Destination Branding. Procedia Economics and Finance, 11, 255-267.

Rietveld, H. C. (2013). Journey to the Light? Immersion, Spectacle and Mediation. . DJ Culture in the Mix: Power, Technology, and Social Change in Electronic Dance Music, 79-102. Sherman, E., Mathur, A., & Smith, R. B. (1997). Store environment and consumer purchase

behavior: Meditating role of consumer emotions. Psychology & Marketing, 14(4), 361-378. Tuominen, P., & Heikkinen, V. (2014). Managing the Multisensory Spaces of Hospitality, Tourism

and Experience Industries. Proceedings of EuroCHRIE 2014, n.a. Dubai: EuroCHRIE. Wakefield, K. L. (1996). The effect of the servicescape on customers' behavioral intentions in

leisure service settings. The Journal of Services Marketing, 10(6), 45-61.

43

Session 3

AR & VR in Education, Retail and for

44

Implementing Augmented Reality to Increase Tourist Attraction Sustainability

Eleanor Cranmer, Manchester Metropolitan University Timothy Jung, Manchester Metropolitan University M. Claudia tom Dieck, Manchester Metropolitan University

Amanda Miller, Manchester Metropolitan University

Abstract

Tourism is in need of new technologies, such as Augmented Reality (AR) to provide enhanced tourist experiences; hence, much research focuses upon this potential. At the same time, sustainability is considered among the most important topics within the tourism domain and the use of information technologies for tourism sustainability has emerged as a research area within the last six years (Ali & Frew, 2010). However, currently few studies explore the use of AR technology in improving and increasing tourism sustainability. Sustainability plays a particularly important role for cultural heritage tourism attractions, which are dependent on their natural environment, cultural and social traditions (Barthel-Bouchier, 2012; Prentice, 1993). One example of such an attraction is Geevor Tin Mine Museum, a UNESCO world heritage site located in Cornwall. Therefore, the present study aims to use the case of Geevor Tin Mine Museum to identify a number of ways AR implementation could positively contribute to increased attraction sustainability.

Keywords: augmented reality, sustainability, tourist attractions, cultural heritage

Introduction and Literature Review

45 experience their surroundings, has propelled AR to become a widely accepted and valuable tool for tourism (Chung, Han, & Joun, 2015; Martínez-Graña, Goy, & Cimarra, 2013). Hence, a number of AR applications in tourism have begun to be developed to create ‘info-cultural-tainment’ experiences (Palumbo, Dominci, & Basile, 2013) and facilitate the tailoring of information to users preferences and knowledge levels (Kounavis, Kasimati, & Zamani, 2012). The potential and benefits of AR are widely explored; however, few studies attempt to appreciate the use of AR as a means to improve sustainability. Using technologies as tools to increase sustainability in tourism is much overlooked, despite the fact ICTs are a critical element in the modern tourism industry (Ali & Frew, 2014). The majority of tourism sustainability studies focus upon the use of technologies in consumer and demand dimensions, technological innovations and industry functions (Buhalis & Law, 2008). Therefore, this study aims to identify how AR implementation can increase sustainability, to help improve the longevity and self-sufficiency of tourist attractions.

Methods

UNESCO recognised Geevor Tin Mine Museum, Cornwall is used as a case study. Performing stakeholder analysis of Geevor identified key influential stakeholders involved in the attraction. As a result 46 semi-structured interviews were held with, 9 internal stakeholders, 30 visitors, 2 tertiary groups, 1 local business and 4 local authorities. The interviews were conducted from April 2015 to March 2016 and lasted between 20 to 52 minutes. Results were analysed using content analysis to permit the identification, comparison and organisation of data.

Findings

46 pressure on staff and helping keep within budget. Further to this, using AR as a method to deliver information and interpretation, such as ‘virtual signage’ was acknowledged for its benefit of minimising damage and harm to the protected environment. This is considered one of the key advantages of AR for destination and attraction sustainability. The introduction of AR in itself was considered a tool to improve sustainability, by broadening the visitor appeal, increasing and enticing interest and demonstrating site advancement. All these factors respondents suggested would ensure the longevity of the attraction, since engaging in younger audiences is vital because they are the visitors of the future. Additionally, attracting more visitors means generating more revenues through increased ticket sales. Lastly, some respondents identified that implementing AR would encourage visitors to spend longer on site, increasing their likelihood to visit, and spend in the site café and shop. An option to link the AR experience to the site facilities and entice customers was recommended as a method to increase revenues and therefore self-sufficiency and sustainability.

Discussion and Conclusion

47

References

Ali, A., & Frew, A. J. (2010). ICT and its role in sustainable tourism development. In U. Gretzel, R. Law., & M. Fuchs (Eds.), Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism

2010 (pp. 479-491), Springer, Heidelberg.

Ali, A., & J. Frew, A. (2014). ICT and sustainable tourism development: an innovative perspective. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 5(1), 2-16.

Barthel-Bouchier, D. (2012). Cultural heritage and the challenge of sustainability: Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet ; the state of eTourism research. Tourism management, 29(4), 609-623. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2008.01.005

Chung, N., Han, H., & Joun, Y. (2015). Tourists’ intention to visit destination: Role of augmented reality applications for heritage site. Computers in Human Behavior, 50(2015), pp. 588-599. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.068

Di Serio, A., Ibanez, M., & Kloos, C. (2013). Impact of an augmented reality system on students' motivation for a visual art course. Computers & Education, 68(2013), 586-596.

Han, D., Jung, T., & Gibson, A. (2014). Dublin AR: Implementing augmented reality in tourism. In Z. Xiang & I. Tussyadiah (Eds.), Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism (pp. 511-523). Wien, New York: Springer Computer Science.

Hume, M., & Mills, M. (2011). Building the sustainable iMuseum: is the virtual museum leaving our museums virtually empty? International journal of nonprofit & voluntary sector marketing, 16(3), 275-289. doi:10.1002/nvsm.425

Kounavis, C., Kasimati, A., & Zamani, E. (2012). Enhancing the tourist expeirnce through mobil augmented reality: challenges and prospects. International Journal of Engineering Business Management, 4(10), pp. 1-6.

Leue, M., Jung, T., & tom Dieck, D. (2015). Google Glass Augmented Reality: Generic Learning Outcomes for Art Galleries Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2015 (pp. 463-476): Springer.

Martínez-Graña, A., Goy, J., & Cimarra, C. (2013). A virtual tour of geological heritage:

Valourising geodiversity using Google Earth and QR code. Computers & Geosciences, 61(0), 83-93. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2013.07.020

Palumbo, F., Dominci, G., & Basile, G. (2013). Designing a mobile app for museums according to the drivers of visitor satisfaction. Retrieved from

48 Prentice, R. (1993). Tourism and heritage attractions.

Roesner, F., Kohno, T., & Molnar, D. (2014). Security and privacy for augmented reality systems (Vol. 57, pp. 88-96). New York: ACM.