i

A STUDY ON THE DEPTH OF VOCABULARY KNOWLEDGE ACQUIRED BY THE THIRD SEMESTER STUDENTS OF ENGLISH EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM OF SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

A THESIS

Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree

in English Language Education

By

Antonius Rendy Endrawan Student Number: 021214031

ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION

SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA

iv

STATEMENT OF WORK’S ORIGINALITY

I honestly declare that this thesis, which I wrote does not contain the works or part of the works of other people, except those cited in the quotations and bibliography, as a scientific paper should.

Yogyakarta, March 2007

v

I Dedicate This Thesis to:

Jesus Christ Almighty God,

Bapak,

Ibu (RIP),

Mbak Nessy,

Mas Sinung,

vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and above all, my greatest gratitude goes to my Holy Lord for His invaluable blessings and for giving me so many wonderful things throughout the journey of my life. Finally I managed to finish this thesis. Thanks God for everything.

Second, I am also in great debt to my major sponsor Dr. F. X. Mukarto, M.S. for giving me his thoughtful understanding, helpful suggestions, and positive advices, for sparing his valuable time to encourage me to finish my thesis, and for sharing me his great knowledge.

I would like to address my thankfulness to Laurentia Sumarni, S.Pd. and Gregorius Punto Aji, S.Pd. for permitting and for letting me to conduct the test in their classes. I am also very much grateful for the third semester students for their participation in the study and for their great contribution to the completion of this thesis. I would also thank Anita for her unwavering support and maintaining my sanity through her compassion and good counsels.

vii

Danik, mBak Tari, and mBak Leli, and those not listed here who have supported me directly and indirectly.

viii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE ... i

APPROVAL PAGE ... ii

ACCEPTANCE PAGE ... iii

STATEMENT OF WORK’S ORIGINALITY ... iv

DEDICATIONAL PAGE ... v

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... viii

ABSTRACT ... xii

ABSTRAK ... xiii

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ... 1

A. Background ... 1

B. Problem Identification ... 3

C. Problem Limitation ... 4

D. Problem Formulation ... 4

E. Research Objectives ... 5

F. Research Benefits ... 5

G. Definition of Terms ... 5

CHAPTER II: LITERATURE REVIEW ... 7

A. Theoretical Description ... 7

1. What is a word ... 7

ix

a. Real and Potential Vocabulary Knowledge ... 10

b. Active (Productive) and Passive (Receptive) Vocabulary Knowledge ... 10

c. Breadth and Depth of Vocabulary Knowledge ... 12

3. L2 Lexical Development ... 13

a. Formal Stage of Development (WordAssociation Stage) ... 14

b. LemmaMediation Stage (ConceptMediation Stage) ... 14

c. IntegrationStage (Final Stage of Development) ... 15

4. Model of Vocabulary Acquisition ... 16

5. Vocabulary Mapping Determinants ... 18

a. From Input to Intake: Quality Determinants ... 18

1) Context of Learning ... 18

2) Intrinsic Difficulties of Second Language Vocabulary ... 19

3) Learner’s First Language ... 19

4) Vocabulary Teaching Strategy ... 20

5) Learner’s Strategies for Discovering Meaning ... 20

b. From Intake to Lexicon: Consolidation Strategy ... 20

c. From Lexicon to Output: Language Use and Feedback ... 21

6. Componential Analysis of Meaning ... 22

a. Types of Meaning Relation ... 22

1) Inclusion ... 22

2) Overlapping ... 22

3) Complementation ... 23

x

b. Procedures for the Componential Analysis of Meaning ... 24

1) Analyzing a Meaning of a Lexical Unit in One’s Mother Tongue ... 24

a) The Verticalhorizontal Procedures ... 25

b) Overlapping Procedures ... 25

2) Determining the Meaning of a Lexical Unit in a Foreign Language ... 25

a) Analysis of Meaning on the Basis of Context ... 25

b) Determining a Meaning of a Lexical Unit with the Help of Informants ... 26

c) The Use of Dictionaries in the Analysis of Meaning ... 26

B. Theoretical Framework ... 26

CHAPTER III: METHODOLOGY ... 29

A. Method ... 29

B. Participants ... 30

C. Instrument ... 30

D. Data Gathering Procedures ... 31

E. Data Analysis Procedure ... 32

CHAPTER IV: RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS ... 33

A. Results ... 33

1. The Meaning of the Verb SEE ... 33

2. The Meaning of the Verb ASK ... 35

xi

4. The Meaning of the Verb GET ... 38

5. The Meaning of the Verb MAKE ... 39

B. Discussion ... 41

1. The Mapping of L2 Vocabularies ... 41

2. Cases Wrong Meaning Mapping ... 45

CHAPTER V: CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ... 49

A. Conclusions ... 49

B. Recommendations ... 49

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 52

APPENDIX I ... 55

xii ABSTRACT

Endrawan, Antonius Rendy. 2007. A Study on the Depth of Vocabulary Knowledge Acquired by the Third Semester Students of English Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University.

Vocabulary learning is central to language acquisition whether the language is a first, second or foreign. In the past years, vocabulary was often neglected in the language teaching and learning because it was thought that learners could learn it by themselves. Recently, the studies addressing the issues on second language vocabulary teaching and learning have got special attention. It could be seen from the flourish of experimental studies and materials development related to second language vocabulary teaching and learning. However, the studies mostly are focused on the measures of vocabulary sizes rather than on the depth of vocabulary knowledge (quality of learners’ vocabulary knowledge) of specific words or the degree of such knowledge, on the growth of L2 lexicons and on the number of words gained or forgotten over time.

The present study is intended to study the depth of vocabulary knowledge acquired by the third semester students of English Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University. It tried to answer just one research question: What is the depth of vocabulary knowledge acquired by the third semester students of English Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University?

The research was a descriptive qualitative study. The participants of the research were the third semester students of English education study program of Sanata Dharma University. A test was conducted to gather the data. The participants were asked to give a selfreport on the knowledge of the meaning of ten English verbs. The instrument used was the modified version of Vocabulary Knowledge Scale proposed by Wesche and Paribakht. Due to the large amount of data, only the meanings of five verbs were analyzed.

xiii ABSTRAK

Endrawan, Antonius Rendy. 2007. A Study on the Depth of Vocabulary Knowledge Acquired by the Third Semester Students of English Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University.

Kosakata adalah suatu hal yang pokok dalam pengenalan bahasa baik itu bahasa ibu, bahasa kedua, ataupun bahasa asing. Dahulu kosakata sering diabaikan dalam pengajaran dan pembelajaran bahasa karena muridmurid dianggap bisa mempelajarinya sendiri. Barubaru ini penelitian membahas isu tentang pembelajaran dan pengajaran kosakata bahasa kedua mendapatkan perhatian khusus. Ini bisa dilihat dari berkembangnya penelitianpenelitian dan pengembangan materi yang berhubungan dengan pengajaran dan pembelajaran kosakata bahasa kedua. Tetapi, penelitianpenelitian itu kebanyakan lebih difokuskan pada penghitunganvocabulary sizes daripadadepth of vocabulary atau kualitas peangetahuan arti kosakata bahasa kedua.

Penelitian ini dimaksudkan untuk meneliti depth of vocabulary knowledge dari mahasiswa semester tiga, program study pendidikan Bahasa Inggris di Universitas Sanata Dharma. Penelitian ini mencoba menjawab satu rumusan masalah: Apakah the depth of vocabulary knowledge dari mahasiswa semester tiga, program studi pendidikan Bahasa Inggris, Universitas Sanata Dharma?

Penelitian ini termasuk dalam penelitian deskriptif kualitatif. Subjek penelitian ini adalah mahasiswamahasiswa semester tiga, program studi pendidikan Bahasa Inggris, Universitas Sanata Dharma. Untuk mengumpulkan data digunakan sebuah tes yang meminta subjek penelitian untuk memberikan selfreport tentang pengetahuan dari arti sepuluh kata kerja Bahasa Inggris. Instrumen yang digunakan adalah modifikasi dari Vocabulary Knowledge Scale yang dibuat oleh Wesche dan Paribakht. Dikarenakan besarnya jumlah data, hanya arti dari lima kata kerja yang diteliti.

xiv

LIST OF TABLES

Table 4.1 Meaning Frequency of the Verb SEE ... 34

Table 4.2 Meaning Frequency of the Verb ASK ... 35

Table 4.3 Meaning Frequency of the Verb KEEP ... 37

Table 4.4 Meaning Frequency of the Verb GET ... 38

1 CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

Introduction

This chapter presents the background of the conducted research, the purpose of the research, the scope of the problem that would be discussed in the research, the benefits that may be obtained from the research and the definition of terms related to the study.

A. Background

(Wesche & Paribakht, 1996: 13; Schmitt, 1998: 282). One obvious limitation of test measuring the vocabulary size is that they do not measure how well given words are known (Read, 1998 quoted in Wesche and Paribakht 1996: 13). Schmitt (1998: 281) says that vocabulary research that is focused on the size of lexicons and the number of words learned through various activities has generated little understanding on how individual words are acquired.

Studies on the students’ vocabulary knowledge have been conducted inside the Sanata Dharma English Education Study Program. Two of them were conducted by Susilo (2001) and Saputro (2005). Susilo (2001) in his study measured the controlled active vocabulary of the students. He found that there were significant differences of students’ vocabulary size in every semester. He concluded that there were gradual improvements of students’ vocabulary sizes along with their length of study. Another study was conducted by Saputro (2005). He investigated the lexical richness in the written work of Indonesian students learning English as foreign language. He found that there were significant differences of lexical density indices of written work between second semester and fourth semester but the others are static. The study also showed that the higher the students’ proficiency level, the students produced more word types and used word types that are less frequent.

essential dimension, it does not mean that the other dimension i.e. depth of knowledge is not important. For advanced learners it is important that they acquire more senses of polysemous word and learn more about possible collocates, special uses, and so on (Boogards, 2000: 495).

The present study is conducted with the aim to study the depth of vocabulary knowledge of the third semester students of English Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University. The study is focused on the third semester students who are considered as the sophomore students. From the study, an assumption of depth of vocabulary knowledge of EFL learners in the initial level could be gained, so that further research aiming to observe the development of vocabulary knowledge could use the results or finding of this study as one of the related references.

B. Problem Identification

Greidanus and Nienhuis (2001) states that a word could be known in all sorts of degrees: from knowing that a given form is an existing word to knowledge including all four aspects of word knowledge which are knowing its form, its position, its function, and its meaning. Vocabulary knowledge of either L1 or L2 learners expands in breadth or the learners’ vocabulary sizes (the number of known words grows) and also in depth (the knowledge concerning the words already known increases, in other words, the quality of what the learners know increases) (Greidanus & Nienhuis, 2001: 567).

C. Problem Limitation

The discussion of the research would be limited on the depth of vocabulary knowledge acquired by the students of English Education Study Program focused on the third semester students. The investigation of the students’ depth of vocabulary knowledge covers the discussion on the students’ meaning mapping on the tested English verbs.

D. Problem Formulation

The general problem of the investigation, the study on the depth of vocabulary knowledge of the third semester students of English Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University, is formulated into more specific problem below:

E. Research Objective

The research would be intended to answer the questions that are formulated in the problem formulation above that is to find out the depth of vocabulary knowledge acquired the third semester students of English Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University.

F. Research Benefits

The result of the study could be used as one of the references for the next study intended to investigate the development of the students’ depth of vocabulary knowledge or any researches conducted in the field of vocabulary teaching and learning. The finding could also be used as a tool to evaluate the instructional processes and practice in the department particularly in the field of vocabulary teaching and learning and in making necessary adjustment for improvement.

G. Definition of Terms

In order to avoid misunderstanding in perceiving and understanding some important terms in this study, some significant terms related to this study would be defined as follows:

1. Depth of vocabulary knowledge

of a word while the breadth of meanings refers to the multiple meaning senses of a word.

2. Meaning mapping

7 CHAPTER II

LITERATURE REVIEW

Introduction

This chapter presents the literature review of the study. It is divided into two parts. The first part is the theoretical description containing review of the related theories to the study and the second part is the theoretical framework of the study.

Theoretical Description 1. What Is a Word?

Word is not an easy concept to define, either in theoretical terms for various applied purposes (Read, 2000: 17). Read makes some basic distinctions as the basic points to define words. One is the distinction between tokens and types. This distinction refers to the counting of words in a text. Individual words occurring more than once in the text are counted each time they are used refer to as tokens (Read, 2000: 18). For example, the word walk in a text occurs as walked, walking and walks is counted three times. On the other hand, the number of types is the total number of the different word forms, so that a word that is repeated many times is counted only once.

While content words – nouns, ‘full’ verbs, adjectives, and adverbs – they have little if any meaning in isolation and serve more to provide links within sentence, modify the meaning of content words and so on.

These content words may occur in various forms. For example, the word “wait” may occur as waits, waited, waiting. They would be normally regarded as the same word in different forms. These different forms are the result of inflectional endings adding to a base form without changing the meaning or word class of the base. The base and the inflected forms of a word are known as lemma (Read, 2000: 18). Content words may also have a variety of derived forms that often change the word class and add a new element of meaning. For example, the derived forms of the word happy: happily, happiness, happier. Even though they have slight semantics differences, all of these words are closely related in form and meaning. Such a set of word forms sharing a common meaning is known as a word family.

2. Vocabulary Knowledge

Richards (1976: 7789 cited in Mukarto 2005: 152) proposed several aspects on assumption of vocabulary knowledge. According to Richards, knowing a word means:

1. knowing its relative frequency and its collocation 2. knowing the limitation imposed on its use 3. knowing its syntactic behavior

4. knowing its basic forms and derivations 5. knowing its association with other words 6. knowing its semantic value

7. knowing many of the different meanings associated with the words

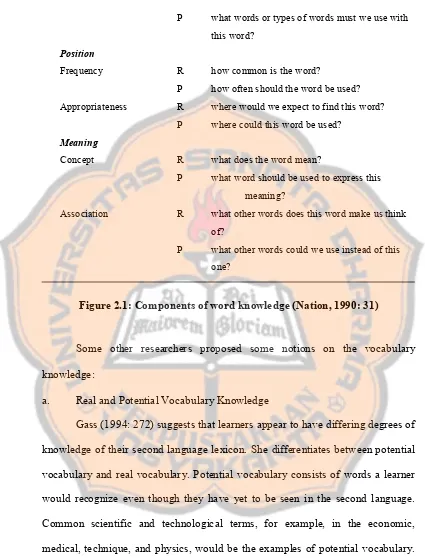

Nation (1990: 31) adopted Richards’ assumption of word knowledge; he added the receptive and productive knowledge and several other considerations and reorganized them.

Form

Spoken form R what does the word sound like?

P how is the word pronounced?

Written form R what does the word look like?

P how is the word written and spelled Position

Grammatical position R in what patterns does the word occur? P in what patterns must we used the word?

Collocation R what words and types of words could we express

P what words or types of words must we use with this word?

Position

Frequency R how common is the word?

P how often should the word be used? Appropriateness R where would we expect to find this word?

P where could this word be used? Meaning

Concept R what does the word mean?

P what word should be used to express this meaning?

Association R what other words does this word make us think

of?

P what other words could we use instead of this one?

Figure 2.1: Components of word knowledge (Nation, 1990: 31)

Some other researchers proposed some notions on the vocabulary knowledge:

a. Real and Potential Vocabulary Knowledge

b. Active (productive) and Passive (receptive) Vocabulary Knowledge Another distinction is between passive (receptive) vocabulary knowledge and active (productive) vocabulary knowledge. Passive or receptive vocabulary knowledge is the matter of word recognition (Gass, 1994: 375). Nation (1990) states that passive vocabulary knowledge includes the ability to distinguish a word from words with a similar form and being able to judge if the word form sounds right or look right. The knowledge involves having some expectation of the words that it would collocate with. Knowing a word in this knowledge includes being able to recall its meaning when we meet it. It also includes being able to see which shade of meaning is most suitable for the context that it occurs in. In addition, knowing the meaning of a word may include being able to make various associations with other related words. On the other hand, active or productive vocabulary knowledge involves knowing how to pronounce the word, how to write it and spell it, how to use it in correct grammatical pattern along with the words it usually collocates with. Active vocabulary knowledge is the extension of passive vocabulary knowledge. Active or productive vocabulary knowledge also involves not using the word too often if it a typically a lowfrequency word, and using it in the suitable situations. It involves using the word to stand for the meaning it represents and being able to think of suitable substitutes if any.

included to eliminate other possibilities). Free active knowledge involves spontaneous use of the word. According to Laufer and Paribakht, these three knowledge types developed at different rates. Passive vocabulary knowledge is the fastest while active (particularly free active) vocabulary knowledge is the slowest. In addition, passive vocabulary is always larger than active vocabulary, although there is a difference between learners in a foreign language setting and those in a second language setting. The gap between knowledge types is smaller in the foreign language setting, suggesting a strong role for the environment in learning (Gass, 1994: 375).

c. Breadth and Depth of Vocabulary Knowledge

Breadth of vocabulary knowledge is defined as vocabulary size, or the number of words for which a learner has at least some minimum knowledge of meaning (Qian, 1999). There are two ways to see how many words a second language learner needs. One way is to look at the vocabulary of the native speakers of English and consider that as a goal for second language learners. The other way is to look at the results of frequency counts and the practical experience of second language teaching and researchers and decide how much vocabulary is needed for particular activities.

meaning of a word while the breadth of meanings refers to the multiple meaning senses of a word.

3. L2 Lexical Development

One of the most essential tasks of vocabulary acquisition in an L2 is the mapping of lexical forms to meaning (Jiang, 2002: 617). Language learners use vocabulary mapping as the learning strategy to identify and specify lexical properties and to eventually incorporate them into their existing lexical system or network of the lexical properties (Mukarto, 1999: 28). This vocabulary mapping constitutes representation of a word meaning both syntactic and semantic features within the meaning boundary of a word which make up the meaning of that word (depth of meaning) and the multiple meaning senses of a word (breadth of meaning) (Mukarto, 2005: 157). This representation refers as meaning mapping. Swan (1997 cited in Mukarto 2005) claims that mapping second language vocabulary onto mother tongue is a basic and indispensable learning strategy. It is a general phenomenon in the EFL learning context in Indonesia.

Based on Levelt’s model of lexical entry in the mental lexicon, Jiang (2000: 48), proposed the three stages of second language vocabulary mapping development.

a. Formal Stage of Development (WordAssociation Stage)

In the initial stage of L2 vocabulary learning, L2 words are mapped to L1 translations, not to its meaning directly. In this stage, L2 words are learned mainly as formal entities because the meaning is provided either through association with L1 translation or by means of definition rather than extracted or learned from the context by learners themselves (Jiang, 2000: 50).

b. LemmaMediation Stage (ConceptMediation Stage)

of corresponding words. The continuous L1 transfer could promote problem for L2 learners. Very rarely do L2 words have one to one correspondence with L1 words (Mukarto, 1999: 28). Poedjosoedarmo (1989: 6670 cited in Mukarto, 1999: 28) suggest that most L2 words are polysemous; they have more than one meaning and different meaning may require different linguistics context.

c. IntegrationStage (Final Stage of Development)

acquisition the learners may copy such abstract entries from L1 lexicon to the interlanguage lexicon to assist the recognition of L2 words. According to her, in this way of learning, concepts underlying word in the L1 are transferred to the L2 and mapped onto the new linguistic labels regardless of differences in the semantics boundaries of corresponding words (Ijaz: 405). This would easily lead the L2 learners to error in L2 use and production. The continuous L1 transfer may also become the impedance of L2 lexical development. L2 learners would stick on a certain stage of development and difficult to reach the complete and final stage of development.

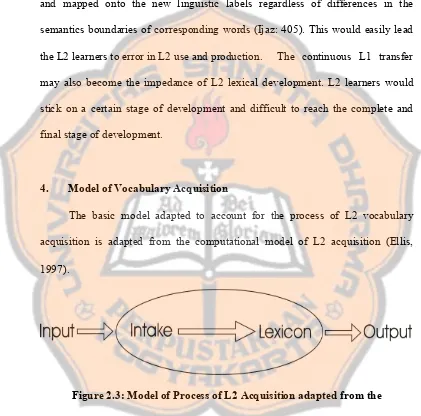

4. Model of Vocabulary Acquisition

The basic model adapted to account for the process of L2 vocabulary acquisition is adapted from the computational model of L2 acquisition (Ellis, 1997).

Figure 2.3: Model of Process of L2 Acquisition adapted from the Computational Model of L2 Acquisition (Ellis, 1997).

input is processed in two stages. First, information contained in the words are attended and taken into shortterm memory. The information attended may be the word forms (spelling, intonation, stress), and the word meaning(s). This attended information are called intake. Then, some of the intake is stored in the longterm memory as part of the lexicon. The process that is responsible for creating intake and the lexicon occurs within the “black box” of the learners’ mind. Finally the lexicon is manipulated or used by the learners in learner language (Ellis, 1997: 35).

This model of vocabulary acquisition corresponds to the five essentials steps in vocabulary learning proposed by Brown and Payne. Their paper was presented at the TESOL convention in Baltimore, MD, in 1994. The steps are 1. encountering new words

2. getting clear image – visual or auditory or both of the words forms 3. getting the word meaning

4. consolidating the word form and meaning in memory so that the new words become part of the lexicon

5. using the word

(Hatch and Brown, 1995: 371 391).

incorporated into the lexicon. In this stage learners continually construct and adjust the vocabulary mapping or network of associations in the mental lexicon. The third stage is the use of the lexicon by the L2 learners. According to Melka (1997), there are two natures of word use: 1. Receptive and productive. In the L2 acquisition context, the use of lexicon or words may serve two functions: to express one self and to understand others in communication. 2. To learn more properties of L2 words or vocabulary.

5. Vocabulary Mapping Determinants a. From Input to Intake: Quality Determinants

The quality of vocabulary intake is subject to the following determinants or factors:

1) Context of L2 Learning

number of contexts resulting the limited identification and acquisition of limited language features.

2) Intrinsic Difficulties of Second Language Vocabulary.

Intrinsic difficulties of L2 vocabulary may cause problems for learners in mapping the L2 words. Features such as familiar phonemes, consistency of sounds script relation, regularity, transparency, register neutrality, and one form to one meaning correspondence help learners in vocabulary mapping and also acquisition. On the other hand features like unfamiliar morphemes, inconsistency of sound script relation, irregularity, lexical complexity, synformity (Similarity among L2 lexical forms), register restriction and one form to multiple meaning correspondences, hinder vocabulary acquisition as vocabulary mapping become much more complicated.

3) Learner’s First Language

It is undeniable that L1 has a considerable influence on how L2 is learned. Swan’s view (1997) says that mapping L2 words into L1 is a basic and indispensable strategy in vocabulary learning, but also inevitably leads to error. Ijaz suggests that L2 learners transfer the concepts in the L1 to L2 words without regarding the differences in the semantics boundaries of corresponding words (Ijaz, 1986: 405) and this may lead the students to the error in the L2 production. Very rarely do L2 words have one to one correspondence with L1 words (Mukarto, 1999: 28). Poedjosoedarmo (1989: 6670 cited in Mukarto, 1999: 28) suggests that most L2 words are polysemous; they have more than one meaning and different meaning may require different linguistics context.

Vocabulary teaching generally focuses primarily on two aspects: form and meaning. The meaning taught is usually the core meanings of the words and the other possible meanings are often neglected because they are considered irrelevant at the moment. The learners learn the L2 words from the L1 translation and the problem here there is no exact translation from L2 to L1.

5) Learner’s Strategies for Discovering Meaning

There are three ways that are most helpful for discovering meaning according to Schmitt’s survey on vocabulary learning strategies used by Japanese learners of English (1997: 221223): (1) checking the meaning of unknown words in bilingual dictionaries, (2) asking teachers for paraphrases, synonyms, or gestures and (3) guessing meaning from contexts. However, Meara (1997) claims that L2 word is only partially taught and learned, but when different aspects of words are touched as the same word is encountered later, the mapping would be adjusted.

In terms of vocabulary mapping, intake is the first step in the mapping process and is temporary and partial in nature.

b. From Intake to Lexicon: Consolidation Strategy

Some of the intake is stored in longterm memory (Ellis, 1997: 35), so that the maximizing the portion of intake in longterm memory as part of the lexicon and L2 knowledge should be the concern of both language educators and the learners.

most commonly used strategy is repetition in its various form, one of them called “structured repetition” technique. This technique requires the students to memorize a list of vocabulary items. Weekly tests, consisting 40% new vocabulary items and 60% “old” vocabulary items which have been tested before, are given as a means to encourage learners to memorize the vocabulary items. In an experimental study, Purba (1990) found out that this structured repetition technique proved to be effective to increase the learners’ mastery of English vocabulary. This technique allows the students to reach their threshold where they could start to learn from context. However, this technique must not be the sole technique of vocabulary learning as only core meanings are given.

Consolidation strategies allow the learners better map the newly acquired vocabulary into the existing lexicon by making as many connections as possible between the newly learned words with the existing lexicon and strengthening the link through repeated encounter of the words in various linguistic contexts.

c. From Lexicon to Output: Language Use and Feedback

the L2 lexical development, it would be better for the teachers or lecturers to give negativefeedback when the students inaccurately map the words.

6. Componential Analysis of Meaning

a. Types of Meaning Relation

According to Nida (1975: 15), there are four principal ways in which the meanings of different semantic units may be related to one another: inclusion, overlapping, complementation, and contiguity.

1) Inclusion

In many instances the meaning of one word may be said to be included within the meaning of one another. All poodles, for example, are dogs, and all dogs are animals. Thus the meaning of poodle could be said to be included in the meaning of dog, and the meaning of dog included in the meaning of animal. Such inclusions of meaning, one within another, are extremely important in determining the significant features of meaning, since each “included” meaning has all the features of the “including” meaning, that is, the immediately larger area of meaning, plus at least one or more feature which serves to distinguish the more restricted area.

2) Overlapping

certain contexts without significant changes in the conceptual content of an utterance. Initial learners should be aware of the English synonyms because they could lead the learners into the misuse of words.

3) Complementation

Meanings complementary to each other involve a number of shared features of meaning, but show certain marked contrasts, and often opposite meanings. Generally, there are three types of complementary relations: (1) opposites, (2) reversives, and (3) conversives.

Opposites are often spoken of as polar contrasts, since they involve distinct antithesis of qualities (e.g. good/bad, high/low,), quantities (e.g. much/little, many/few), states (e.g. dead/alive, open/shut), time (e.g. now/then), space (e.g. here/there), and movement (e.g. go/come).

Certain complementary meanings involve reversives of events, e.g. tie/untie, alienate/reconcile; or may be better described as conversives, e.g. buy/sell, lend/borrow.

4) Contiguity

movement, and the relation of the limbs to the supporting surface involve clearly definable contrasts. The relation of contiguity does not apply to the words walk, hop, run, skip, and crawl, but only to the meanings of those words which are related, in the sense that they share certain common features, and hence constitute a single semantic domain.

b. Procedures for the Componential Analysis of Meaning

A meaning is not a thing in itself, but only a set of contrastive relations. In some instances the crucial contrasts involve a few related meanings, but there is no way to determine a meaning apart from comparisons and contrasts with other meanings within the same semantic area (Nida, 1975: 151).

1) Analyzing a Meaning of a Lexical Unit in One’s Mother Tongue

The procedures for determining a single referential meaning of a lexical unit in one’s mother tongue involve comparison with related meanings of other units, that is, with other meanings in the same semantic domain. Where the meaning of a lexical unit occurs in a semantically contiguous set, especially if this set is part of a more or less systematic hierarchical structure, the procedures are relatively simple, and the results could be determined with little difficulty. Since they are varieties in between comparable meanings it is important to recognize two distinct types of procedure. One may be called the “verticalhorizontal procedures”, the other, the “overlapping procedures”.

a) The Verticalhorizontal Procedures

inclusive meanings, that is, meanings on different hierarchical levels, and (2) a horizontal dimension in which meanings on the same hierarchal level are compared, whether contiguous, overlapping, or complementary.

b) Overlapping Procedures

In general it is preferable to employ the verticalhorizontal procedures in determining the meaning of a semantic unit. However, in many instances it is impossible to do so, since the relevant contrasts could be stated only in terms of overlapping meanings.

2) Determining the Meaning of a Lexical Unit in a Foreign Language

In analyzing the meaning of a lexical unit in a foreign unit in a foreign language, two principal types of resources are usually available: (1) items in context, either existing texts or material provided by informants, spontaneously or by elicitation, and (2) dictionaries (monolingual or bilingual) and vocabulary lists with glosses.

a) Analysis of Meaning on the Basis of Context

The analysis of word meaning on the basis of context could be done by a series sentence of sentences containing different context on the use of the word.

If the lexical unit seems to refer to some entity or object, one of the first question may be, “what does it look like?” It may be necessary to ask questions as, “What does it sound like?” “What does it feel like?” other types of question could be developed to elicit description of words.

c) The Use of Dictionaries in the Analysis of Meaning

Key syntactic and semantic features of a word could be generally found in dictionary definitions (Mukarto, 2005: 156). Finer semantic features of words could be identified by contrasting them with other words sharing the common meaning sense of the words. By contrasting them, one could identify the features that constitute the meaning of those words. In general, dictionaries cover the semantic areas involved, list typical contrast, provide illustrative contexts, indicate different syntactic uses, give historical data suggestive of relation between meanings, frequently list idiomatic and figurative uses, and may note such temporal features as “obsolescent”, “archaic”, “neologism”, etc (Nida, 1975: 172). Dictionaries may also be very useful in providing terms for setting up contiguous and overlapping series, since they often list under generic terms those synonyms which are structurally included.

B. Theoretical framework

vocabulary knowledge is an essential dimension, it does not mean that the other dimension i.e. the depth of vocabulary knowledge is not important. For advanced learners it is important that they acquire more senses of polysemous words and learn more about possible collocates, special uses and so on (Boogards, 2000: 495).

In attempt to answer the research problem mentioned in chapter I, the present study uses several theories: vocabulary knowledge, second language lexical development proposed by Jiang (2000), vocabulary mapping determinant proposed by Mukarto (1999), and componential analysis of meaning proposed by Nida (1975).

Jiang (2000) proposed three stages of second language lexical development, namely: (1) the initial stage of second language lexical development or word association stage, (2) lemmamediation stage or conceptmediation stage, (3) final stage of second language lexical development or integration stage. The stages of second language development is used to see in what stage do the third semester students belong to and to see the quality of mapping produced by the students.

29 CHAPTER III

METHODOLOGY

Introduction

This chapter presents discussion on the procedure of the study. The discussion includes the discussion on the research methodology used on the study, the subjects of the study, the instrument used to gather the data, the procedure of data gathering and the procedure to analyze the data in order to answer the problem formulations mentioned in the first chapter.

A. Method

The present study is a descriptive qualitative study. Fraenkel (1993: 380) affirms that studies investigate the quality of relationships, activities, situations, or materials are referred to as qualitative research. The study investigated the students’ depth of vocabulary knowledge by analyzing documents of selfreport on the students’ knowledge on the meaning of five tested English verbs (see, keep, make, get, ask) and was intended to give a general description on the students’ depth of vocabulary knowledge. The interpretation of the data was descriptive in nature and it did not deal with any hypothesis testing so that the study was a descriptive qualitative study.

B. Participants

The participants of the study were one class of third semester students of English Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University attending Extensive Reading I course. The third semester students were chosen with the assumption that they have had adequate English vocabulary mastery since they have passed courses on Vocabulary I, Vocabulary II, Reading I and Reading II. Therefore, a picture of depth of vocabulary knowledge of L2 learners that is focused to learn English in the sophomore stage could be obtained.

C. Instrument

In order to find out the answer to the research questions, the study used the modified version of Vocabulary knowledge Scale proposed by Wesche and Paribakht (1997: 180). Vocabulary knowledge Scale is a generic instrument that it could be used to measure any set of words (Read, 2000: 132; Mukarto, 2005: 152). It consists of two scales: one for eliciting responses from the testtakers and one for scoring the responses. The first scale is presented with the words to be tested. It has five categories representing how well the testtakers know the words. The categories range from 1 representing complete unfamiliarity to 5 representing the ability to use a word with grammatical and semantic accuracy in a sentence (Mukarto, 2005: 154).

vocabulary knowledge so that it could give clearer picture of the students’ vocabulary knowledge. The scale of scoring was not used because the test results were not scored instead the words which the students have written in the VKS were tabulated.

The tested verbs were taken from Collins Cobuild Dictionary. They were see, get, keep, take, draw, make, run, kill, carry, and ask. The ten tested verbs

were all high frequency words. High frequency verbs were chosen because they usually had more extended meaning than the low frequency words so that they could give more opportunity to the students to explore their vocabulary knowledge in the test. (See Appendix II for the instrument used).

D. Data Gathering Procedure

The subjects were asked to give a selfreport of their knowledge on 10 the tested verbs using the modified version of Vocabulary Knowledge Scale. They had two minutes to give self report on every verb, so that the data gathering lasted for twenty minutes. The data was collected on 9 October 2006. The researcher himself collected the data. The procedure of collecting the data was generally divided into three parts: preparation, administering the test, and data collection. 1. Preparation

Modifying the Vocabulary Knowledge Scale.

Choosing the verbs to be tested from “Collins Cobuild English Dictionary” Obtaining permission to the lecturer whose class was intended to be tested. 2. Administering the test

Distributing the test sheets.

Announcing the time limitation and the prohibition of using dictionary. 3. Data collection

The results of the test were not scored; instead the meaning of the tested verbs which the students had written in the VKS was tabulated into the table of inventory of meaning.

Since the focus of the study was on the third semester students’ depth of vocabulary knowledge, for those who were not the students of the intended semesters but taking the class (shoppers) their works were put aside.

E. Data Analysis Procedure

In order to answer the problem formulation mentioned in Chapter I: What is the depth of vocabulary knowledge acquired by the third semester students of English Education Study Program of Sanata Dharma University? The procedure of data analysis is presented as follows:

1. From the ten tested verbs only five verbs (see, keep, get, make, ask) were chosen to be discussed for reason of manageability, financial and time consideration.

2. Tabulating the data.

33 CHAPTER IV

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

This chapter presents the results of the study and the discussion on interpretation of the results. The results of the study concern the meaning of the tested verbs and their occurrence. Those two aspects are expected to reveal the depth of vocabulary knowledge acquired by the third semester students of English Education Department of Sanata Dharma University. The discussion covers the discussion on the students’ L2 vocabulary meaning mapping and the cases of the students’ inacurrate meaning mapping.

A. Results

The results are the tabulation of the meaning of every tested verb (see, make, ask, keep, get) written by the respondents in the selfreport categories (Vocabulary Knowledge Scale modified version). Every meaning of the tested verbs in the form of both English synonyms and Indonesian translation equivalents is counted so that each meaning and its frequency are presented in the following tables.

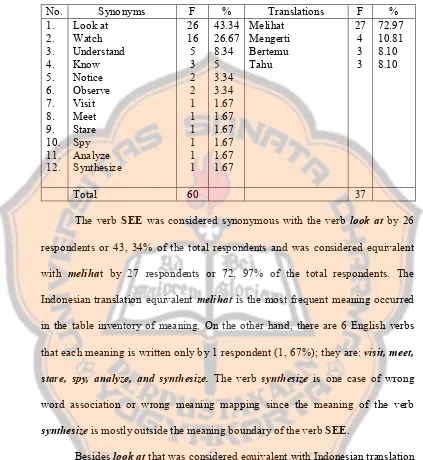

1. The Meanings of the Verb SEE

Table 4.1: Meaning Frequency of the Verb SEE

No. Synonyms F % Translations F %

1.

Total 60 37

The verb SEE was considered synonymous with the verb look at by 26 respondents or 43, 34% of the total respondents and was considered equivalent with melihat by 27 respondents or 72, 97% of the total respondents. The Indonesian translation equivalent melihat is the most frequent meaning occurred in the table inventory of meaning. On the other hand, there are 6 English verbs that each meaning is written only by 1 respondent (1, 67%); they are: visit, meet, stare, spy, analyze, and synthesize. The verb synthesize is one case of wrong word association or wrong meaning mapping since the meaning of the verb synthesize is mostly outside the meaning boundary of the verb SEE.

using the eyes or using the sight sense; rather they have the connotative meaning or the figurative meaning senses of the verb SEE. The verbs that have the figurative meaning senses are: synthesize, visit, meet, understand, know, and analyze.

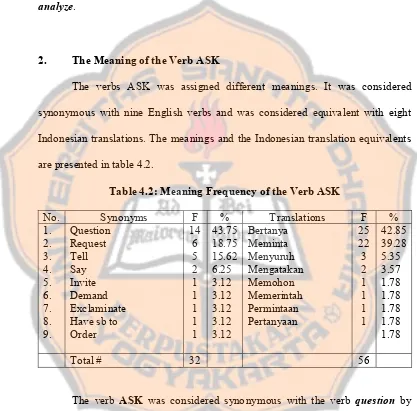

2. The Meaning of the Verb ASK

The verbs ASK was assigned different meanings. It was considered synonymous with nine English verbs and was considered equivalent with eight Indonesian translations. The meanings and the Indonesian translation equivalents are presented in table 4.2.

Table 4.2: Meaning Frequency of the Verb ASK

No. Synonyms F % Translations F %

1.

Total # 32 56

equivalents that are each is also written only by one respondent, they are: memohon, memerintah, permintaan, and pertanyaan. One respondent wrote exclaminate in the selfreport categories, which is not a word or a dictionary entry. In addition, the Indonesian words permintaan and pertanyaan are not classified as Indonesian verbs, rather they are nouns.

Besides the verb question that is considered equivalent with the Indonesian translation bertanya, there are some other English verbs that can be considered equivalent with the Indonesian translation, they are: request that can be considered equivalent with meminta, order that can be considered equivalent with menyuruh and memerintah, have somebody to that can be considered equivalent with menyuruh, and tell and say that can be considered equivalent withmengatakan.

The meaning of the verb ASK that is have somebody to has different meaning with the common meaning of the verb ASK. It does not share the common meaning of the verb ASK which is question. The meaning is one of the examples of extended meaning or multilpe meaning senses of English vocabularies particularly English verbs. The other examples could be found in the table of meaning frequency.

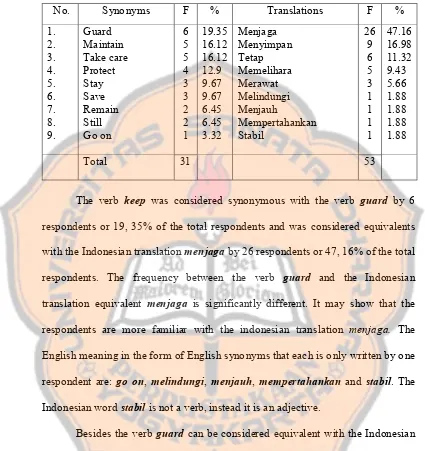

3. The Meaning of the Verb KEEP

Table 4.3: Meaning Frequency of the Verb KEEP

No. Synonyms F % Translations F %

1.

Total 31 53

The verb keep was considered synonymous with the verb guard by 6 respondents or 19, 35% of the total respondents and was considered equivalents with the Indonesian translationmenjaga by 26 respondents or 47, 16% of the total respondents. The frequency between the verb guard and the Indonesian translation equivalent menjaga is significantly different. It may show that the respondents are more familiar with the indonesian translation menjaga. The English meaning in the form of English synonyms that each is only written by one respondent are: go on, melindungi, menjauh, mempertahankan and stabil. The Indonesian word stabil is not a verb, instead it is an adjective.

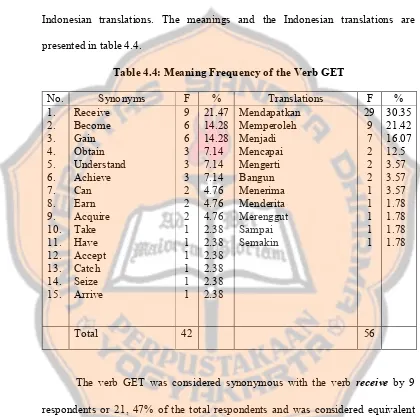

4. The Meaning of the Verb GET

The verb GET was assigned different meanings. It was considered synonymous with 15 English verbs and was considered equivalent with 11 Indonesian translations. The meanings and the Indonesian translations are presented in table 4.4.

Table 4.4: Meaning Frequency of the Verb GET

No. Synonyms F % Translations F %

1.

Total 42 56

The verb GET was considered synonymous with the verb receive by 9 respondents or 21, 47% of the total respondents and was considered equivalent with Indonesian translation mendapatkan by 29 respondents or 30, 35% of the total respondents. Some English verbs are each is only written by one respondent: take, have, accept, catch, seize, and arrive. There are also some meanings in the

consider the Indonesian translation semakin with the verb GET with additional affix ing. From the table of meaning frequency, we could also see the core meaning of the tested verb based on the respondents’ vocabulary knowledge. This notion is also based on the theory of vocabulary meaning mapping determinants saying that usually the meaning of vocabulary taught to the students in the initial level are the core meaning of words. Therefore, the core meaning of the verb GET based on the respondents’ knowledge is receive that is considered equivalent with mendapatkan.

Besides receive that was considered equivalent with the Indonesian translation mendapatkan, there are some other verbs that can be considered equivalent with the Indonesian translation: the verbs receive and accept can be considered equivalent with menerima, the verb become can be considered equivalent with menjadi, the verbs obtain, acquire, and earn can be considered equivalent with mendapatkan and memperoleh, the verb understand can be considered equivalent with mengerti, achieve can be considered equivalent with mencapai, and the verb arrive can be considered equivalent with sampai. The verb understand contribute the connotative meaning of the verb GET since the verb understand is not the literal meaning of the GET.

5. The Meaning of the Verb MAKE.

Table 4.5: Meaning Frequency of the Verb MAKE

No. Synonyms F % Translations F %

1.

Total 16 45

The verb MAKE was considered synonymous with the verb create by 9 respondents or 56, 25% of the total respondents and was considered equivalent with membuat by 31 respondents or 68, 89% of the total respondents. The frequency of the Indonesian translation equivalent membuat is significantly higher compared to the English verb create and to other meanings and the Indonesian translation equivalents.

something, although, actually, both verbs have slight different sense. The verb make has the sense of forcing somebody to do something, on the other hand, the verb have has the sense of persuading or ordering somebody to do something.

Three respondents wrongly associate the verb MAKE with Indonesian translation equivalents berlari and meminta. The Indonesian translation berlari and meminta are mostly outside the meaning boundary of the verb MAKE. It seems that the respondents fail to identify the meaning boundary of those words.

B. Discussion

1. The Mapping of L2 Vocabularies

equivalent with menjaga, and the core meaning of the verb GET is receive that is considered equivalent with mendapatkan. The decreasing of meaning frequency from the verb that has the highest frequency to the verb that has the lowest frequency may indicate that the meanings in the table range from the core meaning to peripheral meaning. It may show that in the high frequency words the unknown features of the verb is relatively low so that it is easier for the respondents to identify their semantics features whereas in the low frequency words the unknown semantic features is relatively high.

The tables of meaning frequency of every verb showed that the respondents’ knowledge on the meaning of each verb is varied. It may confirm Jiang’s statement that learners’ L2 lexicon contains words that are at various stages of development, or, it can be said that a respondent’s knowledge on the meaning of certain words may better than the other words.

In the study, the four verbs: SEE, ASK, GET, and KEEP showed that the respondents’ have built L2 lexical networks on their lexicon. They mapped or associated the tested verbs with other different verbs to express their knowledge on the meaning of the tested verbs. The respondent may no longer depend on Indonesian translation equivalent in the meaning recognition of the verbs; instead they have had a L2 lexical network to recognize the meaning of the tested verbs.

Since the third semester students are the sophomore students, they may have not had enough exposure to English. In the previous stage of learning (junior high school or senior high school) the students probably got English learning subject in their school but the teaching and learning process still use Indonesian as the medium of instruction. This kind of English learning setting may not provide the students with enough exposure to English. Moreover, when learning English vocabularies the students are provided with the Indonesian translation to facilitate the vocabularies learning. It gives the students opportunity to remember the meaning of the vocabularies in form of Indonesian translation rather than extracted from context, i.e. English texts. Jiang (2000: 50) said that in the initial stage of vocabulary learning, especially in tutored context, L2 vocabularies are learned as formal entities or the vocabulary learning is focused on the formal features of the word, i.e. spelling, pronunciation, the meaning is provided through L1 translation or by means of definition rather than extracted or learned from context by learners themselves.

courses such as prose, extensive reading, drama, and play performance, so that they have more opportunity to learn English from context and reach fuller development stage of L2 lexical development.

2. Cases of Wrong Meaning Mapping

Swan (1997 cited in Mukarto, 1999: 34) holds the view that mapping L2 words onto L1 is a basic and indispensable strategy, but also inevitably leads to errors. The errors come from the learners’ inability to define the semantics boundaries of L2 words that results in the mismatch of meaning features contained within L1 and L2 words. The error on the meaning mapping of L2 words seemed to be a general phenomenon in the L2 learning context. Ijaz (1986) holds a similar view that second language learners tend to transfer concepts in the L1 to the L2 and mapped onto new linguistics labels regardless of differences in the semantics boundaries of corresponding words. However, very rarely do L2 words have one to one correspondence with L1 words so that the mapping L2 onto L1 words would be prone to error (Mukarto, 1998: 28).

dictionary entry for the verb SEE). It is obvious that mapping the meaning of the verb see to the meaning of the word synthesize is inaccurate.

Inaccurate L2L2 meaning mapping may be caused by a lack of exposure as well as opportunity to use English vocabularies. In this case, it is possible that the student does not have enough knowledge on one of the words either see or synthesize or maybe the students’ knowledge on the meaning of both words is partial in nature, or some of the semantic features of the words are known while the others are not. This results in the failure of the students to identify the semantic boundary of both words which may lead to the inaccurate meaning mapping.

The second case is the inaccurate meaning mapping of L2 to L1. In this case, the verb make is mapped or associated with the Indonesian translation berlari and meminta. The meaning of Indonesian verbs berlari and meminta share very few meaning features of the verb make. In other words, the meaning of Indonesian verb berlari and meminta are mostly outside the meaning boundary of the verb make.

48 CHAPTER V

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This chapter presents the conclusions and the recommendations related to the study. The conclusions are drawn from the discussion on the result of the study presented in the chapter IV. The recommendations are intended for the lectures, the learners and the following researchers conducting similar study.

A. Conclusions

Based on the discussion on the result of the study, the following conclusion is drawn:

B. Recommendations

This section is meant to present some recommendations that would hopefully give a new idea to provide a better teaching and learning process in the English Language Education Study Program Sanata Dharma University. The first recommendation is intended for the lecturers who are competent to conduct good circumstances to facilitate the learning process. The second is for the students who are going to learn. The last is or the other researchers who are interested in conducting further study, particularly in the area of vocabulary.

1. For the Lecturers

a. Although breadth of vocabulary knowledge is an essential dimension, it does not mean that the other dimension i.e. depth of vocabulary knowledge is not important. For advanced learners, it is important that they acquire more senses of polysemous words and learn more about possible collocates, special uses, and so on (Boogards, 2000: 495). Considering the notion above, it is recommended for the lectures to teach vocabulary not merely focused on the students’ vocabulary size but also to teach the depth dimension of vocabulary knowledge or focused to the quality of the students’ vocabulary knowledge.

meaning of English words would be improved so that such case of inaccurate words meaning mapping resulting from students’ failure in identifying the semantics boundary of given words could be lessen.

c. To avoid fossilization in the L2 lexical development process, the lecturers are recommended to be aware on such cases of inaccurate meaning mapping. The lecturers could give some kind of negative feedback every time there is a student whom inaccurately maps English words.

2. For the Students

a. The goal of vocabulary learning is to reach the final stage of L2 lexical development or in other words, approaching the nativelike vocabulary knowledge. Thus, the students should be always proactive to enrich their own vocabulary by doing a lot of practice and exposures through reading English text such as English novel, English newspaper, etc. Class participations would be very helpful.

b. The students should apply strategies to learn vocabulary. Strategies that could be used may include consulting the dictionary either monolingual or bilingual, guessing words in context, and etc.

3. For Other Researchers

The results of the study raise several inputs for the other research which could be investigated in the future.