Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Survey of Recent Developments

Ross H. McLeod

To cite this article:

Ross H. McLeod (2000) Survey of Recent Developments, Bulletin of

Indonesian Economic Studies, 36:2, 5-41, DOI: 10.1080/00074910012331338873

To link to this article:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910012331338873

Published online: 18 Aug 2006.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 64

View related articles

SURVEY OF RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Ross H. McLeod*

Australian National University

SUMMARY

Economic recovery remains hostage to politics, with the diverse coalition that makes up the cabinet unable to provide strong and effective government. There has been a high turnover of ministers, and the governor of the central bank has been placed in detention. Communal violence continues on a large scale, and law and order appears to be deteriorating. The economy has been growing modestly, but investment spending—the most basic indicator of confidence in Indonesia’s near-term economic prospects—remains far below pre-crisis levels.

POLITICAL BACKGROUND TO ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS

Although the economy is emerging hesitantly from the depths of recession, it will not return to normality in the near future. The severity and longevity of the crisis can be explained by the fact that it is primarily political rather than economic. For many years Indonesians awaited, with what can now be seen as well justified apprehension, the so-called ‘succession’: the transition to a new regime after many years of autocratic rule by Soeharto. The financial disturbance that began with the floating of the Thai baht in mid 1997 helped to trigger this transition, but also has been greatly amplified by it.

There was considerable rejoicing when public pressure succeeded in forcing Soeharto from office, and again when the parliamentary election process was completed successfully a little more than a year later, but the manner of the election of the new president, Abdurrahman Wahid (Gus Dur), in October 1999 gave cause for concern as to whether the diverse coalition that resulted would be able to deliver coherent policies and good government (Mietzner 2000: 39–40). By June 2000, five members of the first Wahid cabinet and one of their replacements had resigned or been dismissed, and euphoria had given way to frustrated cynicism and concern for Indonesia’s future.

The Bank Bali scandal that emerged towards the end of the Habibie interregnum made it clear that the Soeharto era practice of using public funds for private and political purposes had not ceased with the demise of the former president. And after Gus Dur took over the reins of power, it soon became apparent that Indonesia had yet to acquire a government and bureaucracy that consistently put the interests of the people and the nation before those of the political, business and bureaucratic elite.

The Dismissal of Laksamana Sukardi

Of major significance was the April dismissal from office of the Minister for Investment and State Enterprises, Laksamana Sukardi (SP, 25/4/00).1

to accept either explanation. Two alternative theories are: first, that factions of both the president’s party (PKB) and the vice-president’s party (PDI-P) are as kindly disposed to Texmaco’s owner as was Soeharto; and, second, that Laksamana was removed because as Minister for State Enterprises he had refused to accede to others’ suggestions as to who should be appointed to top management positions in those firms— positions that had been used in the past to bestow substantial financial favours on cronies and the former first family.

The Bulog Scandal

While this episode was still fresh in the public mind, a new scandal involving the logistics agency, Bulog, hit the headlines. This involved some Rp 35 billion (about $4 million) from the staff pension fund, which Bulog’s deputy, Sapuan, asserted he had disbursed after unrelenting pressure from the president, allegedly to support humanitarian relief work in Aceh (Kompas, 30/5/00). The president’s ‘masseur’, Suwondo— who turned out to be an entrepreneur of considerable means for a person with such a poorly remunerated vocation (SP, 10/6/00)—is alleged to have played a key role as go-between for the president in seeking access to non-budgetary funds. Sapuan was arrested, but Suwondo had yet to be tracked down at the time of writing, as had Leo Purnomo, a staff member at a new airline—Air Wagon International, established by a group that included Gus Dur and Suwondo (JP, 12/6/00)—who reportedly received Rp 5 billion of the missing funds (JP, 8/6/00).

If that were not enough, it was soon revealed that the president had received a gift of $2 million from the Sultan of Brunei (DJN, 12/6/00). Again, the alleged purpose was charity work in Aceh, but the public was disquieted to learn that the fruits of this magnanimous gesture were channelled not through the government system but through a non-government organisation led by the chair of PKB in Aceh and affiliated with Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the traditionalist Islamic body that Gus Dur headed until November 1999, shortly after he became president (Adil, 16–22/6/00).

The Detention of the Central Bank Governor

At the same time that the Bulog farce was being played out, the president was doing all he could to unseat the governor of the central bank, Syahril Sabirin. With its heavy emphasis on central bank independence, the new law on Bank Indonesia (BI) enacted in 1999 makes it impossible for the government to dismiss the governor, except if the latter is convicted of a criminal offence. Apparently anxious to be rid of Sabirin, the president appears at first to have secretly offered him an ambassadorship in return for his resignation (SP, 6/6/00), but when this offer was refused, he applied heavy pressure by stating openly that the governor had been corruptly involved in the Bank Bali scandal (JP, 8/6/00).

But there seems to have been another motive for wanting to remove Sabirin from his post. The government has been in the process of replacing the top management of the state banks, and Gus Dur’s preferred candidate for president director of Bank Rakyat Indonesia failed to pass the ‘fit and proper’ test applied by BI (DJN, 6/6/00). The president made his displeasure known to the public, as a result of which the Sabirin case has acquired a disturbing similarity to the dismissal of Laksamana.

Policy Making Outside the Bureaucracy

The bureaucracy seems to have made little contribution to resolving the economic crisis. This is hardly surprising in view of Lindsey’s comment (2000: 287) that ‘… by the end of Soeharto’s rule in 1998, the bureaucracy had largely ceased to function as any form of rational administration’, because of ‘the almost complete subordination of the administrative branch of government to its executive …’. The president’s lack of confidence in his economics coordinating minister and other economics ministers (two of whom, including Laksamana, have been removed from the cabinet) and in the policy advice available from their largely ineffectual departments has led to a proliferation of advisory groups. Most prominent is the National Economics Council (DEN)—a group of about a dozen academic economists, former ministers in various fields of economics, and representatives of business. Less prominent, and perhaps having less influence because of its perceived self-interested stance, is the National Council for Business Development (DPUN), a group of about 18 prominent business people. Working in the background is the more recently created Assistance Team, led by the foremost technocrat from the New Order, the seemingly ageless Professor Widjojo Nitisastro, assisted by two young and increasingly prominent economists, Dr Sri Mulyani (who is also active as DEN Secretary) and Dr Faisal Basri, and one big business representative, Alim Markus. Finally there is a monitoring team led by the formerly high profile economics consultant Rizal Ramli (now head of Bulog), which meets with the president on a weekly basis—among other things to report on the performance of various ministers. All of this can do little but reinforce the impression of a highly fragmented government with no clear sense of direction in formulating economic policy.

Social Unrest and the Military

of murdering some 57 villagers in Aceh in July 1999—and sentenced to up to 10 years’ imprisonment—no highly ranked officer has been charged, much less punished, for any wrongdoing (WSJ, 18/5/00).

Two bomb blasts occurred in the city of Medan in May, including one in a church that caused scores of injuries (DJN, 29/5/00). But the principal focus of social unrest recently has been in Maluku, where several thousands of individuals have been killed, injured, or driven from their homes in communal violence pitting Christians against Muslims. Not only have the armed forces been unable to put a stop to the carnage (DJN, 21/6/00): they have also failed to prevent the emergence of a Muslim militia known as Laskar Jihad, which openly trained its recruits near Jakarta before sending them off to Maluku to wage war on the Christian community in defiance of Gus Dur’s pleas (FEER, 6/7/00). Worse still, many believe that elements of the military are participating actively in the violence—on both sides—including supplying arms to the protagonists. The announcement by Gus Dur of a state of civil emergency in Maluku (Jawa Pos, 27/6/00) has failed to bring calm to the province, and there is a growing perception that social unrest, bombings and the like are being orchestrated by those anxious to keep the president off balance, and to cripple the government’s attempts to act against those who were involved in corruption and other crimes during the Soeharto era.

Slow Progress with Reform in the Legal Sphere

Nor has there been any improvement in the functioning of the police force. On the contrary: especially in Jakarta there is concern about the steady deterioration of law and order (SP, 20/6/00). People are more and more wary of travelling around at night, and robberies in broad daylight are commonplace. Frustration with the incapacity of the police to protect the public has seen the emergence of an extreme form of street justice, in which robbers who happen to be caught in the act are beaten, doused with fuel and then set on fire by people in the vicinity (JP, 11/6/00). The Jakarta police chief bemoaned the barbarity of these acts (DJN, 12/6/00), but if the police cannot improve their performance, more of the same is to be expected: there is a demand for law enforcement, and if the public sector cannot provide it, it will be ‘privatised’.

disputes.’ Ironically, this is even more of a problem now than it had been under Soeharto, for in that era Soeharto and his appointees as governors and bupati (district chiefs) were in effect the ultimate source of authority, and people rarely bothered to use the courts when those at the top had made it known who was to be the winner in any given dispute. With nobody now playing this Soeharto role, the courts are being called on to do much more than before, especially in the commercial area. But this has served only to increase the opportunities for extracting bribes from parties in dispute, and to expose the atrophy of legal skills in the judicial system during the long years when they became largely irrelevant.

Nowhere is all this more evident than in the new Commercial Courts, from which a stream of highly questionable judgements has issued since their establishment in 1998. And no single entity has suffered as greatly as the Indonesian Bank Restructuring Agency (IBRA), which has lost all but a tiny handful of the scores of cases it has brought against defaulters, apparently because of a very understandable reluctance on the part of its officials to compete by offering bribes (using public money) to the judges hearing these cases. The proposal to appoint ad hoc judges to the courts in order to overcome the lack of expertise in the financial area and to raise standards of probity has as yet come to nothing, presumably because of resistance from incumbent judges and corrupt bureaucrats who prefer to keep the system as it is. Likewise, other initiatives intended to reform the judiciary (Fane 2000: 26–7) are yet to have any discernible impact.

There are hopes that the parliament (DPR) may make a significant contribution to the cause of law reform—and indeed, reform more generally—by appointing capable individuals of high integrity to a number of current vacancies on the Supreme Court, including the position of Chief Justice. But these appointments have been awaited for some time, and there are no doubt strong forces at work supporting a continuation of the status quo. Without an infusion of capable, reform-minded judges, it is unlikely that public trust in the courts can be rebuilt.

The Role of Parliament

rates on recapitalisation bonds (see below). In the case of IBRA, the DPR has been critical of attempts to negotiate settlements with defaulters involving debt write-offs, even though this is often the least costly option in the attempt to recover losses from the government’s bailout of the banking system.

It is not surprising that the DPR responds to public pressure in opposition to increases in prices. The public are well aware that they will be called upon for years to come to bear the enormous costs of bailing out the banking system, whether in the form of higher taxes or reduced provision of government services. They also vaguely comprehend that many of the individuals who are responsible for these costs (through their failure to repay loans from the banks) remain very well off. They correctly infer from this that an enormous wealth transfer is now in progress at their expense—whether to cover losses that should have been borne by those who undertook unsound investments, or to cover wilful default on a grand scale facilitated by a corrupt legal system. It is hardly surprising that members of the public resist paying more for fuel, electricity and public transport in such circumstances.

In at least one instance where the parliament could have made an important contribution, the Texmaco case, it failed to do so. As Fane (2000: 20) noted, after extraordinarily brief consideration of the case the DPR concluded that there was nothing untoward, and that the former regime had acted correctly in providing a huge amount of subsidised funding for the conglomerate. Few impartial observers were satisfied with the argument that the company was ‘a national asset … entitled to government assistance in time of crisis’ (JP, 1/12/99), not least because it would have been possible to keep the company in operation without bailing out its owners, and because the details of how the funds were actually used remained unclear. Ironically, the attorney general’s decision eventually to halt investigation into the case in May 2000 caused heated debate in the DPR (JP, 27/5/00).

doubt, desirable, the possibility of frequent changes in the presidency injects even greater uncertainty into politics, and this is something Indonesia can ill afford at a time when it is trying to convince the business community that it is safe to resume normal activity.

MACROECONOMIC CONDITIONS

Economic Growth

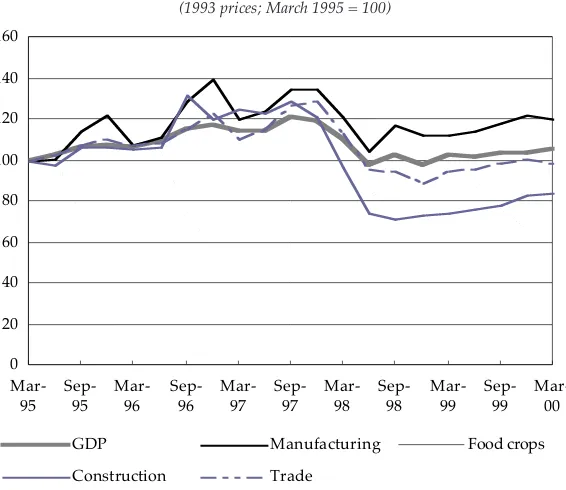

The economy bottomed out in the last three quarters of 1998, at a level of output similar to that recorded during 1995. Modest growth has occurred since then, such that output in the March quarter of 2000 was about 5% higher than during the depths of the recession (figure 1). With population growing by about 8% since Q1 1995, the implied fall in real per capita output is less than 3%. This is far less drastic than the 30% fall that some

FIGURE 1 Major Sectors’ Growth Performance (1993 prices; March 1995 = 100)

observers prefer to highlight, which is based on GDP measured in irrelevant current dollar prices rather than constant rupiah prices. Nevertheless, real output is now some 37% less than it would have been if the pre-crisis average growth rate of 7.5% p.a. had been maintained (cf. Pardede 1999: 9). Seen from this perspective, the crisis has been costly indeed.

Growth performance varies widely across major sectors of the economy. Construction fell most rapidly and by proportionately the greatest amount—about 45% in the year to mid 1998—but it has since been growing at nearly 12% p.a. from this low base. Wholesale and retail trade also fell precipitously—by some 31%—in calendar 1998, and has been growing at about 8% subsequently. Output of the oil and gas sector and the general government sector has been fairly stable during the crisis, as has that of food crops (seasonal fluctuation aside). It is surprising, however, that after bouncing back in 1999, recorded food crop output in the first quarter of 2000 was actually a little lower than in 1998 at the height of the El Niño drought. Since climatic conditions have been favourable, there is scepticism as to the accuracy of the Q1 2000 agriculture figures. The sector least affected overall by the crisis is manufacturing,

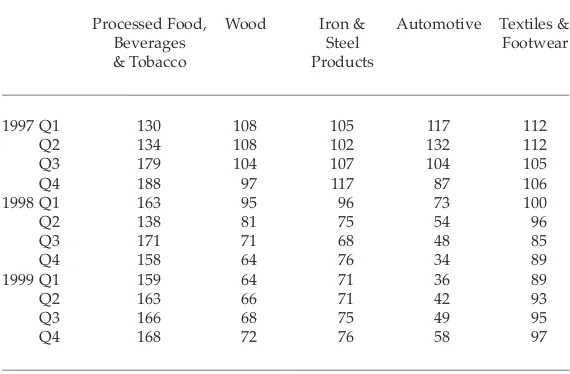

TABLE 1 Output of Selected Manufacturing Subsectors (March 1995 = 100)

Processed Food, Wood Iron & Automotive Textiles &

Beverages Steel Footwear

& Tobacco Products

1997 Q1 130 108 105 117 112

Q2 134 108 102 132 112

Q3 179 104 107 104 105

Q4 188 97 117 87 106

1998 Q1 163 95 96 73 100

Q2 138 81 75 54 96

Q3 171 71 68 48 85

Q4 158 64 76 34 89

1999 Q1 159 64 71 36 89

Q2 163 66 71 42 93

Q3 166 68 75 49 95

Q4 168 72 76 58 97

which, even after contracting considerably in the first half of 1998, never fell below its Q1 1995 level, and has also been growing at about 8% p.a. subsequently.

When manufacturing sector performance is disaggregated, however, it appears that the dominant processed food, beverages and tobacco subsector has generated the bulk of this success (table 1). Its output hardly declined as a result of the crisis (although strong seasonal volatility obscures the picture), and was running 62% higher in Q1 2000 than in Q1 1995—in stark contrast to all other major sectors. Output of the automotive subsector, in particular, fell by about three-quarters from mid 1997 through the end of 1998, and although it has grown quite rapidly since then, in Q1 2000 it remained 40% below its level five years earlier. Other subsectors such as wood products, iron and steel products, cement and textiles, relying heavily on depressed sectors of the domestic market, are still operating at low levels of output, although all have recovered somewhat from the low points reached in 1998.

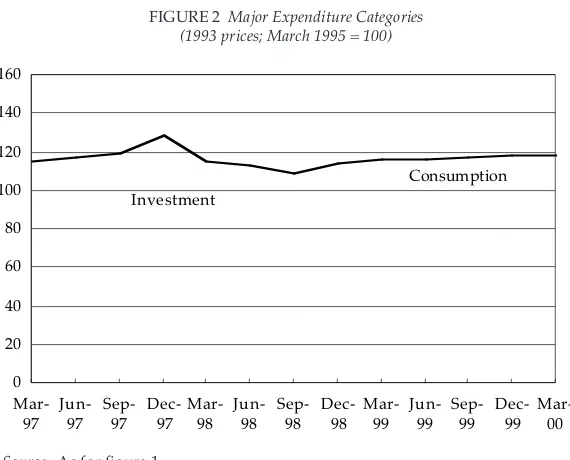

From the expenditure perspective, there is a sharp contrast between household consumption and investment (figure 2), reflecting the much greater degree of discretion that attaches to timing of the latter: baldly

FIGURE 2 Major Expenditure Categories (1993 prices; March 1995 = 100)

stated, people have to eat, but businesses and government can choose not to expand productive capacity if circumstances are not congenial. Although consumption exhibited some volatility early in the crisis— partly related to seasonal factors—the extent of the decline from its trend level was never more than 10%, and it has been growing slowly since Q3 1998. By contrast, investment (i.e. gross fixed capital formation) fell steadily for almost two years from immediately after the crisis started, to about half its initial volume. The levels recorded more recently have been significantly higher than the lowest ebb, but the promising spurt in Q4 1999 was not maintained in Q1 2000.

The data presented above are consistent with a general impression that the business community is ‘marking time’; very few firms seem interested in undertaking any major new investments. Ways are being found to adjust to low levels of domestic demand in many markets, to cut costs by substituting cheaper inputs (including locally produced import substitutes), to postpone the repayment of existing obligations, and to adjust to the lack of new loans available from banks. In short, most decision makers in the private sector would probably agree with the economics coordinating minister, Kwik Gian Gie, who was widely criticised for saying, reportedly, ‘If I were a foreign investor, I wouldn’t come to Indonesia. The law enforcement is not there, but not only that, the whole thing is so confusing’ (DJN, 11/5/00).

Forecasts of overall growth in 2000 range from a low of 1.5% in the central statistics agency’s (BPS) ‘worst case scenario’ (box 1)2 (JP, 17/5/00)

through 3–4% at BI (DJN, 6/6/00), to the president’s 5.5% ‘if we are really lucky’(DJN, 8/6/00), and economics commentator Sjahrir’s 6% (JP, 26/ 6/00). The international financial institutions and most commentators appear to accept 4% as realistic for the time being. The wide dispersion of these forecasts highlights their arbitrariness, which is inevitable given the current high level of political uncertainty.

Inflation and Monetary Conditions

BOX 1 BPS AS ECONOMIC FORECASTER

BPS’s involvement in economic forecasting is a matter of some concern (DJN, 21/5/00). Other countries’ national statistics agencies stay clear of such involvement, for reasons that also apply in the Indonesian context. First, forecasting involves conflict of interest. Having made a forecast, the agency will inevitably feel under some pressure to produce ex post data that demonstrate, or at least do not call into question, its forecasting capabilities. Second, growth rate and inflation rate forecasts are politically sensitive numbers if they are produced by a government agency, and thus are capable of drawing BPS—which ideally should be above politics—into political controversies. Thus for it even to raise the possibility (much less to predict) that year 2000 growth might be well below the official target immediately drew criticism from many who accused it of adding to general concerns about the process of economic recovery and therefore possibly helping to bring about just this unwanted outcome. Moreover, the comment could be interpreted as a veiled criticism of the government’s performance in managing the economy. Third, with limited resources, the statistics agency should concentrate its attention on producing and disseminating the best possible and most useful permanent record of what has happened—not guesses about what will happen, which have little or no lasting value.

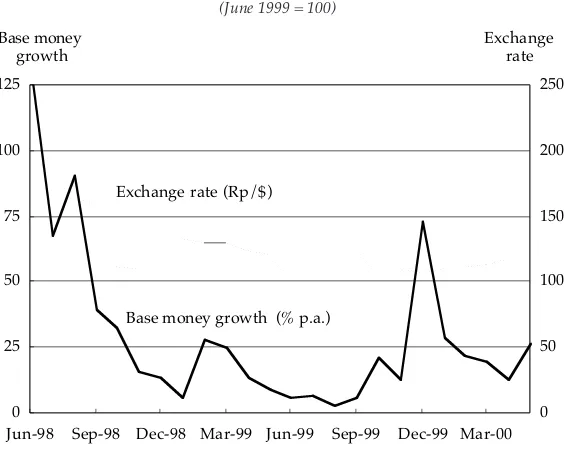

Figure 3 presents annualised base money growth rates for the preceding six-month period. On this basis, it shows that the downward momentum of the money growth rate was lost in about August 1999. The six-month growth rate quadrupled between August 1999 and November 1999, and more than doubled again by January 2000. By May 2000 it was approaching five times the rate of mid 1999, at 27% p.a. (The spike in December 1999 can be ignored: it is largely the consequence of the now all but forgotten Y2K bug, which saw Indonesian banks holding vastly increased amounts of cash and clearing deposits at the end of 1999 for precautionary reasons.)

Base money is measured differently in the government’s Letters of Intent (LOIs) to the IMF and in the balance sheet of the monetary authorities, on which the above comments are based, making direct comparison of absolute levels impossible. Nevertheless if we compare the implied growth rates in the LOIs, a similar conclusion about loss of

FIGURE 3 Base Money Growth (6-Month) and Exchange Rate (June 1999 = 100)

Source: As for figure 1.

0 25 50 75 100 125

Jun-98 Sep-98 Dec-98 Mar-99 Jun-99 Sep-99 Dec-99 Mar-00 Base money

growth

0 50 100 150 200 250 Exchange

rate

Exchange rate (Rp/$)

control of money growth emerges. The targeted increase in base money from August 1999 through March 2000 in the July 1999 LOI was 7.8%, whereas the actual increase (as recorded in the May 2000 LOI) was 12.8%. And the recorded increase for the 12 months to May 2000 was 18.7%, which may be compared with targeted growth rates of 13.4% p.a. in the year to March 2000 (March 1999 LOI), and just 8.6% p.a. in the period January through December 2000 (May 2000 LOI).

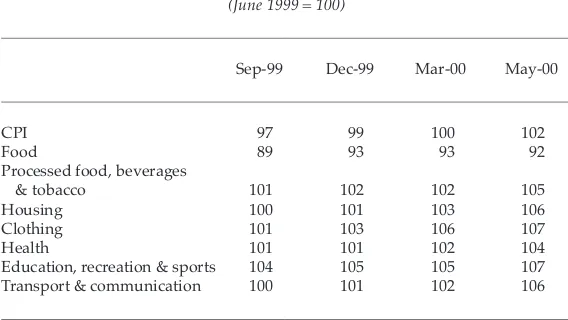

It is of interest to note that the unprocessed food component of the CPI (dominated by rice) was much lower in June 2000 than a year earlier, following a large decline early in this period (table 2). It is important not to jump from this observation to the conclusion that inflation would have been higher if not for this fortuitous decline in rice prices, as this begs the question as to whether price rises in the other categories would have been the same if rice prices had been rising, not falling. The monetarist view is that declines in the value of money (which is another way of referring to increases in the price level) depend significantly on the rate at which the supply of money grows. From this it follows that for a given growth rate of money, declines in prices of particular goods will tend to cause increases in prices of other goods. To put it another way, relative price changes are not inflationary or deflationary.

TABLE 2 The CPI and Its Major Components (June 1999 = 100)

Sep-99 Dec-99 Mar-00 May-00

CPI 97 99 100 102

Food 89 93 93 92

Processed food, beverages

& tobacco 101 102 102 105

Housing 100 101 103 106

Clothing 101 103 106 107

Health 101 101 102 104

Education, recreation & sports 104 105 105 107 Transport & communication 100 101 102 106

Thus if inflation is to be kept in check, the central bank will need to exercise more careful control of its monetary liabilities than it has been doing in recent months. With its independence now enshrined in law, it can no longer blame government interference for its failure to keep monetary policy on track.

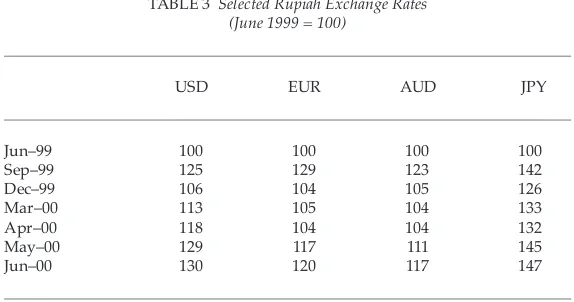

Rupiah Exchange Rates

Figure 3 also shows that the strong recovery of the rupiah in the latter half of 1998 has not been sustained; by the end of June 2000 the rupiah price of dollars was 30% higher than in mid 1999. There was continued volatility in 1999, albeit not of the same order as previously, with the strongest point being recorded in mid 1999. After the election of Gus Dur in October 1999 the rupiah again strengthened, but this was short lived, and there has been a steady decline subsequently.

The rupiah is not the only currency to depreciate against the dollar in recent times, so its decline against some currencies (such as the euro and the Australian dollar) was relatively slight until about April 2000 (table 3). But there has been a significant decline subsequently against even these currencies. Moreover, depreciation of the rupiah against the yen has been even greater than that against the dollar; this is significant because Japan is Indonesia’s most important single trading partner, and an important source of foreign loans.

TABLE 3 Selected Rupiah Exchange Rates (June 1999 = 100)

USD EUR AUD JPY

Jun–99 100 100 100 100

Sep–99 125 129 123 142

Dec–99 106 104 105 126

Mar–00 113 105 104 133

Apr–00 118 104 104 132

May–00 129 117 111 145

Jun–00 130 120 117 147

The impact of depreciation of the currency is multi-faceted. Tradable goods producers will gain from increased competitiveness, especially relative to Japan. On the other hand, those with unhedged borrowings denominated in dollars and yen will suffer wealth losses. Having said this, it is not clear to what extent borrowers have reduced their exchange rate risk exposure in recent months, having learned in the most direct possible manner of the considerable danger of not doing so in 1997–98.

There is now a widespread perception that continued weakness of the currency can be explained by psychological factors, political uncertainty and social disharmony. For example, the then senior deputy governor of BI, Anwar Nasution, was reported as saying that ‘the fate of the rupiah will depend on developments in the economy, politics and security. If we continue to fight and burn other people’s property [the rupiah will continue to weaken]’ (JP, 24/5/00). On the other hand, economics coordinating minister Kwik Kian Gie could offer no explanation for why the rupiah remained weak, given that ‘all macroeconomic and monetary aggregates are showing positive and encouraging development’ (DJN, 12/6/00).

What Should the Central Bank Be Doing?

Two questions being asked repeatedly of the central bank are: what is being done to stabilise or strengthen the rupiah? and what is going to happen to the interest rate on BI certificates of deposit (SBIs)? BI finds itself facing a number of policy options, none of them congenial. The extent to which it can sell off international reserves to support the rupiah is limited, since commitments to the IMF do not allow significant reductions in these reserves. Besides, the government has a nominal commitment to a floating exchange rate policy, however vaguely this is defined (McLeod 1999: 149), which would be incompatible with significant intervention in the foreign exchange market. On the other hand, if it moves to strengthen the currency indirectly by increasing SBI rates, it increases its own costs, and it increases the government’s cost of servicing the enormous volume of bonds it has issued to recapitalise the banking system, since the interest rate for most bonds is the same as that on SBIs. Both factors have a substantial impact on the budget, directly or indirectly.

The official answer to these questions was provided by the then BI governor, Syahril Sabirin, in a parliamentary hearing on 12 June 2000. BI ‘would continue to intervene to prop up the rupiah’, including raising interest rates on SBIs (JP, 13/6/00). A more appropriate answer would have been to say that BI has no target for either the exchange rate or the level of interest rates, and that these two financial prices are being left to be determined by the markets—in the same way that the prices of shares, or bananas, for example, are determined. At the same time, it would be necessary to emphasise that this would not mean that the central bank was doing nothing. On the contrary, what it is (or should be) doing is controlling the growth of its own monetary liabilities—base money— and all financial prices are being influenced, indirectly, through this instrument. To put it differently, the most effective means available to the central bank of contributing to general stabilisation is to do what the current LOI requires it to do: stick to a clear and sensible target growth rate for base money (currently about 7% p.a.).3 By contrast, there are no

targets in the LOI for the exchange rate or interest rates, for good reason: in implementing monetary policy, less is more.

money to grow far more rapidly than the current LOI calls for suggests that reluctance to allow upward adjustment of these rates has once again been compromising the LOI base money growth targets.

Alternative Monetary Policies

Frustration with the steady decline of the rupiah appears to have led to a ‘brief exchange of views’ on the possibility of introducing capital controls at a meeting between the president and his economic ministers and advisers at the end of May (DJN, 1/6/00). But there was little support for the idea, and it was officially laid to rest a few days later at a meeting between the president and the new managing director of the IMF, Horst Koehler (JP, 6/6/00). Another radical alternative for stabilising monetary conditions—a currency board, which had been close to adoption shortly before Soeharto was forced from office in May 1998—has reappeared in recent times, with the publication of an article advocating such a course in the international press (AWSJ, 15/5/00). The suggestion was quickly followed by a strongly voiced counter attack in a letter to that newspaper by former BI governor Soedradjad Djiwandono (AWSJ, 26/5/00). By contrast, Schuler’s (1999) suggestion of dollarisation for Indonesia seems to have fallen on deaf ears, at least for the time being.

At the time the currency board proposal was endorsed by Soeharto, the extraordinarily vociferous domestic and international opposition to it was not to the currency board concept per se, but was driven, rather, by the conviction that the proposal was a subterfuge by Soeharto to enable him to prolong the looting of the central bank that was already under way. In the event, of course, that looting continued regardless, and it is sobering to contemplate that the ultimate damage might have been less if the proposal had not been blocked. The Soeharto factor hardly seems relevant any longer, however, with the former president apparently seriously weakened by two strokes, being subjected to repeated (albeit apparently fruitless) questioning in relation to corruption allegations by the attorney general’s office, and having been placed first under city detention and then, in late May, under house arrest (Kompas, 30/5/00).

1998: 32–3). His proposal was to announce the intention to establish a currency board, and then to allow the rupiah to float freely without any form of intervention in the market by the central bank for a period of perhaps a month; the chosen rate would be that which emerged from this market driven process by the end of the free-float period. Individuals close to the policy making action at the time seem in little doubt that Soeharto’s intention was to fix the rate within the range just mentioned, regardless of Hanke’s position, but if the currency board proposal is to be rethought now, this important detail concerning the process for setting the rate will need to be taken into account.

BANK RECAPITALISATION AND THE SAGA OF BANK CENTRAL ASIA

In thinking about the collapse of the banking system and the damage this has done to the economy (box 2), it is worth noting that although this is widespread in terms of the number of banks that have failed, to a large extent the losses are concentrated amongst the state banks and a small number of private banks—including Bank Central Asia (BCA), now majority owned by IBRA on behalf of the government. The bank was taken over in May 1998 after Soeharto’s resignation triggered a run on its deposits, but not before Bank Indonesia had provided a staggering amount of liquidity support—some Rp 32 trillion (Republika, 19/9/98), equivalent to about $4 billion at an exchange rate of Rp 8,000/$.

Since BCA was owned by various members of Soeharto’s family and by long-time crony Liem Sioe Liong, it immediately came under physical attack by opponents of the regime when Soeharto was forced by public pressure to step down in May 1998. It was soon taken over by the government, and eventually became part of IBRA’s portfolio, pending de-nationalisation.

BOX 2 ALTERNATIVE MEASURES OFTHE COSTOF BAILING OUTTHE BANKING SYSTEM

Fane (forthcoming) suggests that the probable (stock) cost of the government’s commitment to bail out depositors and other creditors of the banking system (often misunderstood as bailing out the owners of the banks, although in reality there is probably much of this as well) is of the order of 40% of GDP. An alternative measure is the flow cost—the annual cost of amortising the stock cost over a number of years. This is more difficult to determine because it involves a somewhat arbitrary choice as to the length of the amortisation period, and also requires the choice of a suitable interest rate. Notwithstanding these difficulties, it is of interest to estimate the flow cost on the basis of various assumptions.

In table 4, flow costs are estimated for amortisation periods of 10 and 20 years, and for interest rates of 10, 13 and 15% p.a. It is assumed that nominal GDP grows at 5% p.a., and that domestic revenues are always 13% of GDP. On this basis, the flow cost is of the order of 3.3–6.7% of GDP, and 25–52% of domestic revenues.

TABLE 4 Flow Costs of Banking System Bailout Costing 40% of GDPa

Interest Rate Amortisation Period

(% p.a.) 10 years 20 years

% of GDP % of % of GDP % of

Domestic Domestic

Revenue Revenue

10 5.4 41 3.3 25

13 6.2 47 4.2 32

15 6.7 52 4.8 37

aIt might be thought that if inflation were to increase significantly, these

of the range that had been discussed just a few weeks earlier. The issue was reported to have been moderately (1.2 times) oversubscribed, and will contribute about Rp 0.9 trillion to the government’s cash inflows in the current financial year—considerably less than the Rp 3 trillion, and later Rp 1.5 trillion, previously hoped for (Fane 2000: 30; DJN, 10 and 24/5/00). The level of interest on the part of foreigners was relatively low, despite the government’s attempts to promote BCA as the jewel in the crown of the private bank sector, and it was necessary to rely on domestic investors for the success of the issue.

Two state-owned securities companies closely related to IBRA (Danareksa Sekuritas and Bahana Securities) had committed themselves to taking up nearly 43% of the issue each if it could not be sold; the long list of 76 other underwriters could only be persuaded to commit to taking 15% of the issue between them—less than 0.2% each (BCA 2000: 180–2). Given this obvious lack of interest among relatively sophisticated market players, both foreign and domestic, there are suspicions that many of the shares have not really left government hands at all, but have merely been shifted from one government agency to various others, including the pension funds of various government entities.

Failure to achieve substantial foreign involvement in BCA is a blow to IBRA, which had already been dealt what can be seen in retrospect as a devastating setback by the withdrawal of Standard Chartered Bank from its intended move into Bank Bali (Fane 2000: 29). IBRA has had very little success in its attempts to rehabilitate the banking system, and doubts began to emerge in June about the next important challenge—the intended merger of eight failed banks into Bank Danamon, prior to de-nationalisation of the merged entity (Bisnis Indonesia, 9/6/00). It appears there were concerns as to the adequacy of the required equity injection by the government, which amounted to Rp 29 trillion (of which almost Rp 28 trillion was needed to cover the combined losses of the group).5

All in all there seems good reason to review carefully the entire rehabilitation strategy, and the BCA share sale is a good place to start.

Rethinking Bank Restructuring

to risk-weighted assets) for banks after recapitalisation (by comparison with the pre-crisis target of 12%); and the use of government bonds rather than cash as the government’s equity injection to banks being recapitalised.

Reducing the CAR Requirement. Even the 8% CAR set out in the Basle Capital Accord6 implies an extremely high level of leverage (i.e. ratio of

debt to equity) by comparison with what is regarded as reasonable in the corporate sector. This implies that banks’ shareholders have very little of their own funds at risk, and almost guarantees that moral hazard will be a serious problem—especially in developing countries where financial skills are lacking, legal systems are weak, and uncertainty is relatively high. Thus one lesson from the East Asian crisis is that minimum capital adequacy levels should be raised, not lowered, in order to give a much stronger incentive in the future for banks to be managed in prudent fashion. (It is the writer’s understanding, however, that a lowering of the minimum CAR to 4% was urged by the IMF from the outset, though the rationale remains unclear.)

This argument carries even greater force in an economy in the midst of a deep recession and financial crisis, in which it is unlikely that newly recapitalised banks will be able immediately to begin operating profitably. The worst of the non-performing loans may well have been stripped from these banks’ balance sheets, but it can hardly be imagined that the remaining assets will be trouble-free with the economy still in such poor shape. The ‘negative spread’ problem—interest expenses exceeding interest revenues—that has dogged the banks since early in the crisis will not soon disappear, which means that even if the banks had genuine 4% CARs to begin with, these may soon be whittled down to nothing. None of these arguments seems to commend itself to the central bank, which has announced a further softening of the CAR requirement (JP, 16/6/00) in the forlorn belief that it is this that is holding back the long awaited resumption of bank lending (rather than such things as political uncertainty, already high indebtedness of potential borrowers, and lack of confidence in the legal system). This is reminiscent of the government’s lack of conviction about the importance of strong prudential regulation, apparent in the 1992 Law on Banking (McLeod 1992: 116–7), and of a similar watering down of the CAR requirements in mid 1993 (McLeod 1993: 21). The inherent conflict between BI’s roles as prudential regulator and monetary policy maker has thus come to the fore yet again, despite the unconvincing attempt in the new central bank law (no. 3 of 1999) to preclude this by separating these functions (McLeod 1999: 151–2).

has bailed them out. In principle there is nothing wrong with using government bonds rather than cash to recapitalise banks. All that is required is to increase the aggregate value of assets to a level that exceeds liabilities by the required minimum book value of equity, and this can be done by adding a sufficient quantity of any kind of asset. However, if the bond interest rate is set unrealistically low relative to market rates, the bonds’ market value will be less than their nominal value. Especially if the government bonds form a large proportion of total assets in a bank’s post-recapitalisation balance sheet, overstatement of the true value of the bond portfolio would mean that the true value of equity could be considerably less than its book value.

Consider a concrete example—roughly representative of BCA’s balance sheet—in which the post-recapitalisation bank has total assets of 100, comprising bonds worth 64 (at face value) and risky assets worth 36. Deposits and other liabilities sum to 95, such that equity is 5. Equity seems impressive at 14% of risk-weighted assets (bearing in mind that government bonds carry a zero risk weight).7 But if the true value of the

bonds is, say, just 8% less than their face value (i.e. 59) the true value of equity is then 0, and the true CAR is 0%.

There have been few market transactions involving these government bonds,8 but market observers recall some sales at discounts of 15–25% to

face value. An explanation is not hard to find. Almost all are variable rate bonds, the interest rate being equal to the yield on 3-month SBIs, yet the maturities are spread over periods ranging up to as long as 10 years— with increasingly larger amounts at longer maturities. By contrast with more developed financial markets in which there is a strong demand for long-dated interest-bearing securities, these are almost unknown in Indonesia. Although banks accept 2-year time deposits, there is very little demand for them, and apparently none at all for longer maturities: investors are very reluctant to tie up their savings for periods longer than 1–3 months.

SBI rate in recent times, which would suggest a bond rate about 3.75% higher than the 3-month SBI rate. This indicates strongly that the recapitalisation bonds are overvalued, and suggests that Brown’s concern that the true value of BCA’s equity might in fact be zero or negative was well founded.

Presumably the government’s decision to set such a low bond interest rate was driven by a desire to minimise the future budgetary impact of servicing the recapitalisation bonds. With roughly Rp 400 trillion issued9

(Fane 2000: 29), and with the 3-month SBI rate around 11% p.a., the budgetary cost is around Rp 44 trillion— equivalent to over a quarter of the government’s total domestic revenue in 1998/99—so it is hardly surprising that this is a politically sensitive issue. Nevertheless, it is not possible to reduce the cost of bailing out failed banks’ depositors and other creditors in this manner: recapitalising with bonds whose true value is less than their face value is equivalent simply to supplying something less than the full amount of cash needed to bring the banks’ equity up to a genuine 4% CAR.

The government seems to have been well aware of this. From the outset there was some confusion as to whether or when banks holding recapitalisation bonds would be permitted to sell them into the market, and eventually it was announced that such sales were restricted to no more than 10% of the full amount they had received. The only sense that can be made of this is that the government feared that if the bonds were sold their true value would be revealed, and the banks would be seen to be well below the required minimum CAR. An implication of this is that the central bank is now knowingly allowing the banks to overstate their capital adequacy, which does not augur well for the new era of meaningful prudential regulation.

DECENTRALISATION

Laws 22 and 25 of 1999 on Regional Government and Fiscal Balance between the Centre and the Regions, respectively, enacted by the short-lived Habibie administration, aim to bring about one of the most profound reforms to Indonesia’s system of government in decades (Booth 1999: 28). The desirability of such reforms is widely accepted in principle, but there is a growing realisation that attempts to implement them too rapidly—at a time when the economy is still in very poor condition and political stability is far from assured—could be a disaster. It is arguable, therefore, that the reforms should be put on hold, even at the risk of further aggravating the crisis of mistrust in the government. Implementation is not the most important issue. Rather, the great danger of having pushed through such important legislation very quickly is that it will prove to be misconceived (box 3), and a delay in implementation would provide an opportunity to rethink the entire approach to decentralisation. The following discussion can do no more than highlight just some of the many issues that seem worthy of careful reconsideration.

It is unfortunate that in Laws 22 and 25 the word ‘region’ (daerah) applies to both provinces and districts/municipalities, as though the distinction between them were unimportant. On the contrary, whether ‘regional’ autonomy turns out to be meaningful is likely to depend crucially on the extent to which various functions of government are devolved to these two distinct levels. Perhaps the major reason for doubt as to the willingness of the centre to cede significant power to the regions, and for concerns about the smooth implementation of decentralisation, is the decision to bypass the provinces and shift the bulk of centre funds earmarked for the regions all the way down to the district/municipality level. This is believed to have been insisted upon late in proceedings by then President Habibie and the military, against the wishes of those who had been responsible initially for drafting the legislation. It has been justified in terms of the need to bring government closer to the people. The more plausible explanation, however, is that the centre wanted to avoid having to deal with challenges to its policies and authority that might have arisen from time to time if it provided more substantial amounts to (and thereby strengthened) the relatively few provinces, whereas it would face no conceivable challenge of any substance from a highly fragmented group of roughly 370 far smaller districts.

BOX 3 DECENTRALISATIONAND BPS

One example of problems posed by a hastily decided decentralisation initiative relates to the collection of statistics. It is intended that the regional offices of BPS henceforth should come under the control of regional governments. This raises important questions about the priority that will be accorded to data collection by these governments, the relative importance assigned to different kinds of data, and the possibility of many different methodologies being adopted. In particular there is concern that the national budget for routine data collection and analysis is being reduced in anticipation that local governments will carry the funding burden. The capacity to produce a complete set of standardised data on a national basis would appear slight under such circumstances.

Indeed, recent events appear to portend the decline of key data sources. The population census carried out in June involved a much shorter form than previous sample censuses, and was to be administered to all households and processed in regional offices. The omission of detailed questions on employment was justified on the grounds that the Susenas (National Socio-Economic Survey) would produce such information for regional governments. Unfortunately, a series of budget cuts to the census brings the quality of the data it yields into question. Also, exercising their new powers under regional autonomy, local officials in some provinces added extra questionnaires on income and expenditure that provoked resistance and criticism in the community, causing delays in data collection. All this implies that the 2000 census could be less reliable than any census since 1961. This problem is exacerbated by other budget cuts, and cuts to sample size and survey detail, which suggest that the Susenas will not be able to produce representative data at the level of small provinces or districts/municipalities. As a result, within the next few years analysts will be hard pressed to answer important questions about local trends in employment, education, health and demography, and national estimates may be clouded by non-standardised methods of data collection and analysis. This is a matter of great concern to the professionals at the Central Statistics Agency, but its resolution requires understanding and commitment by the Ministry of Finance, Bappenas (the National Planning Agency), and particularly the DPR.

to keep provincial governments weak suggests strongly that powerful interests at the centre in fact do not want to give up their control of various areas of policy and administration, and that, despite the best intentions of those responsible for bringing the draft laws to the parliament, the shift to greater emphasis on regional autonomy may be more apparent than real.

Real or Imaginary Autonomy?

Although the words otonom (autonomous) and otonomi (autonomy) are sprinkled liberally through them, the degree to which the new laws will promote genuine regional autonomy cannot be taken for granted. Doubts emerge as soon as we look at some matters of detail. Consider, for example, the status of provincial governors. Law 22 states that the provincial parliament is responsible for electing the governor (and deputy governor), but elsewhere it requires that the list of names of candidates for these positions be determined in consultation with the president. The parliament also ‘recommends’ his/her appointment (or subsequent discharge from office), presumably to the president, but it is not clear that the latter is obliged to accept the recommendation. The law does state explicitly, however, that the governor is the representative of the central government, and is accountable to the president.

The legislators attempt to rescue their devolutionist bona fides by distinguishing dual roles for governors: although all are to be representatives of the centre and accountable to the president, they are also to be chief officers of their province and accountable to its parliament. This appears very much in line with old ways of thinking in Indonesia about how government at various levels should operate, relying on the belief that these two roles can be kept separate and that conflicts between them will never arise. Alternatively, it might be argued that to be accountable to two different entities is to be accountable to neither, or that one role will win out over the other—and with the bulk of province funding coming from the centre, governors seem likely to care more about keeping the president happy than looking after the interests of their constituents. Dwifungsi (dual functions) for governors are no less likely to be injurious to the public interest than they have been in respect of the military (which has exercised both military and civilian functions) or the state enterprises (being required simultaneously to maximise profits and to sell their products at a loss as ‘agents of development’).

for example, although the law states explicitly that the district/ municipality (kabupaten/kotamadya) is not subsidiary to the province, it nevertheless requires governors, as representatives of the centre government, to ‘guide and supervise’ them. Elsewhere, the law gives the centre the power of veto over regulations and decrees of the regions’ chief officers that are in conflict with the ‘public interest’—as interpreted, presumably, by the centre. None of this seems compatible with genuine regional autonomy.

Funding of Decentralised Government Activity

One of the noteworthy aspects of the new fiscal arrangements is that they make little attempt to match the total funds available to regional governments with their likely expenditures. Indeed, the funding arrangements were all determined in May 1999, while the government regulation that lists the sharing of expenditure responsibilities between centre and regions was still being formulated more than a year later!

Law 25 lists four categories of ‘revenue’ for funding activity that is the responsibility of regional governments (i.e. ‘decentralisation’): the region’s own income (pendapatan asli daerah); equalisation funds (dana perimbang); borrowing; and ‘other’. Regions’ own income consists of regional taxes, levies (retribusi), profits from regional government enterprises, and returns on other assets owned by regional governments. Regions’ borrowings may be made directly from domestic sources, or indirectly from offshore through the centre. Domestic borrowing is a potential area for concern, as it cannot be taken for granted that the regions will have the same degree of commitment to keeping borrowing to a prudent level as did the national government under Soeharto.10 ‘Other’

covers any other lawful possibility, but is not specified further in the law. The most important revenue category is equalisation funds, which are transferred from the centre budget to the regional governments. These consist of a general funds allocation, a special funds allocation and an allocation from land and other natural resource revenues.

BOX 4 REGIONS’ SHAREOF REVENUESFROM LANDAND OTHER

NATURAL RESOURCES

The complex system for sharing revenues from land and other natural resources is summarised in table 5. There are some curious features worth noting, and certain aspects remain unclear as a result of poor drafting.

In this context, the single term ‘region(s)’ (daerah) may have five possible meanings:

• the province from which the revenue derives (the source province); • all provinces;

• the districts/municipalities from which the revenue derives (source districts/ municipalities);

• non-source districts/municipalities in the source province; • all districts/municipalities in Indonesia.

When the percentage shares in the table are marked ‘?’, it is not clear from the law to which one of these regions the share in question is allocated.

TABLE 5 Shares of Each Government Level in Land and Natural Resource Revenuesa

(%)

Centre Regions

Source All Source Other All Province Provinces District/ Source National

Municipality Province Dist./ Dist./Mun. Mun.

Land

PBB (10)b 90 ? 90 ? ? ? 10

BPHTB (20)b 80 ? 80 ? ? ? 20

Natural resources

Forestry

IHPH 20 16 ? 16 ? 64 0 0

PSDH 20 16 ? 16 ? 32 32 0

Fisheries 20 80

Mining

IT 20 16 64 0 0

IE & Royalties 20 16 32 32 0

Oil 85 3 6 6 0

Gas 70 6 12 12 0

aPBB: Pajak Bumi dan Bangunan (Land & Building Tax)

BPHTB: Bea Perolehan Hak atas Tanah dan Bangunan (Land & Building Transfer Tax) IHPH: Iuran Hak Pengusahaan Hutan (Forest Enterprise Levy)

PSDH: Provisi Sumber Daya Hutan (Forest Royalties) IT: Iuran Tetap (Land Rent)

IE: Iuran Explorasi (Exploration Levy)

BOX 5 AN INDEPENDENT WEST PAPUA? JAKARTA’S NEW CHALLENGE

Since the fall of Soeharto, all four resource-rich provinces (Aceh, Riau, East Kalimantan and West Papua) have made extravagant claims both for a much greater share of the natural resource revenues they generate and for greater economic and political autonomy—or independence. A major goal of Law 25 is to placate these provinces by offering them a significant share of such revenues. West Papua, with its huge gold and copper deposits, its large reserves of natural gas, and its abundant forest resources, stands to gain enormously in revenue terms from the new fiscal arrangements.

Will this offer of greater fiscal autonomy be enough to persuade West Papuan leaders to drop their demand for independence? The resolution from the government-supported Papuan People’s Congress held in Jayapura from 29 May to 4 June 2000, proclaiming that West Papua had been independent since 1961 (AWSJ, 5/6/00), suggests otherwise. The offer of a large share of resource revenues has perhaps dampened protest and helped to maintain relative calm, and Gus Dur’s decision to rename Irian Jaya ‘West Papua’, and to see in the new millenium in the provincial capital of Jayapura, were masterly political moves. But West Papuans have been disappointed by Jakarta’s greater preoccupation with Aceh—even if the much more tense security situation there in the past year indeed warranted such attention. In the wake of the special meeting of Papuan leaders convened by then President Habibie in Jakarta in February 1999, the failure to acknowledge the need for some form of special status for Irian Jaya at the MPR session in November 1999 was a disappointment: evidence to suggest, yet again, that Jakarta could not be relied upon to work out such an arrangement.

In contrast to Riau and East Kalimantan, the case for greater autonomy in West Papua (as in Aceh) goes far beyond the division of spoils from natural resources. It relates to a strong sense of difference in social and cultural norms from those of the dominant Javanese culture, as well as to the way in which Irian Jaya was ‘incorporated’ within the Republic. On the other hand, many claims of injustice are exaggerated: Jakarta has provided generous financial support to Irian Jaya over the years, and the province certainly has performed better than independent Papua New Guinea on a range of social and economic indicators.

Gus Dur’s offer of greater freedom and consultation is a beginning. But as tensions rise in the wake of the People’s Congress, it appears that Jakarta will need to take concrete steps to deal with the deep sense of grievance associated both with the failure to acknowledge and accommodate perceived differences, and with Jakarta’s clumsy and often repressive actions in Irian Jaya over three decades.

The only type of natural resource revenue that appears even roughly to approximate being treated correctly from a constitutional point of view is that derived from fisheries, 80% of which is divided equally amongst all districts/municipalities (with the remainder going to the centre). At first glance this may seem a reasonably fair approach to distributing this revenue, but it ignores the vast differences in population amongst districts/municipalities. Thus, for example, the citizens of East Kotawaringin district receive only half as much on a per capita basis as their neighbours in West Kotawaringin because they are twice as numerous. And the unfortunate residents of Bogor district, with a population about twenty times as great as West Kotawaringin, receive only one-twentieth as much.

Another important aspect of the scheme for allocating natural resource revenues that seems to have attracted little attention is that for some categories it discriminates not only against resource-poor provinces, but also against poor districts/municipalities within the resource-rich provinces. To take a specific example: non-mining districts/ municipalities in a mining province receive no share of the IT (land rent) mining revenue, while the districts/municipalities where the mining takes place receive 64% of what they generate.

In thinking about the new funding arrangements, it is useful to bear in mind that Rp 1 billion of revenue finances Rp 1 billion of government spending, regardless of where the funds come from originally, or in what category they fall. All that matters, therefore, is: (a) how much in total the centre distributes to lower levels of government; and (b) how this amount is apportioned amongst different governments at each level. From this it follows that the entire scheme for allocating natural resource revenues could turn out in practice to be nothing more than an elaborate hoax on the resource-rich provinces and districts/municipalities, since their share of the other equalisation fund components seems likely to be relatively small.

The general funds allocation will discriminate amongst regions in precisely the opposite direction from that for natural resource revenues. This allocation is fixed in total at ‘not less than 25% of domestic revenues’ of the centre,11 and the total amount is split in the proportion 10% for the

such as the ‘potential’ of manufacturing (whatever this might mean), the endowment of natural and human resources, and gross regional domestic product.

Presumably it is intended that a given region’s proportional entitlement to this general funds allocation is positively related to ‘needs’ and negatively to its ‘economic potential’ (the law is not explicit). If so, the latter aspect is surprising: the greater the economic potential of a region, the greater the level of government spending on infrastructure and the provision of services likely to be needed to complement private sector activity in exploiting this potential. This point aside, note that if the amount going to a specific region is indeed negatively related to its natural resource endowment, this is precisely the reverse of the case with natural resource revenues.

Thus the gain to resource rich provinces and districts/municipalities from natural resource revenues could be largely offset if their proportional entitlements to the general funds allocation are set at a low level precisely because of their large resource endowments. This point carries even greater force when we take into account the special funds allocation from the centre budget to regions to finance expenditures in relation to ‘specific needs’. The law does not seem to have anything to say about who is to be the arbiter of such ‘needs’, and it is hard to imagine that it will not be the centre. In principle, the resource-rich regions may well discover that they have no special needs at all.

Reallocation of Civil Servants

An issue that has been largely absent from debate on devolution is what happens to bureaucrats at the centre. Shifting financial resources to the regions implies that work previously done at the centre is now to be done in the regions. This requires reallocating bureaucrats from the central government’s payroll to those of the regions, and from the provinces to the districts/municipalities, but such relocation is likely to be strongly resisted in at least some cases.12 Moreover, there will be opposition to

governments, the reallocation of revenues to the regions offers the promise of controlling funds considerably in excess of the amounts controlled in the past, and far too many potential mini-Soehartos relish this prospect— and will not want to share the side benefits it will bring.

No Distinction between Districts and Municipalities

An important but unremarked feature of the new laws is that they do not differentiate between districts (kabupaten), on the one hand, and municipalities (kotamadya), on the other, except by name. Thus the cities of Semarang and Solo are treated in exactly the same way as the largely rural districts that make up most of the rest of Central Java, for example. Yet the funding requirements for managing a city are likely to be quite different from those for rural areas. Large cities are usually the location for universities and hospitals, for example, whereas rural areas have only schools and health clinics. The physical infrastructure of cities—roads, streets, traffic lights, public transport, storm-water drainage and sewerage systems—are all qualitatively different from what is required in small towns and rural areas. Moreover, cities, and the rural lands that surround them, are mutually dependent. The cities are the node through which many agricultural products from their hinterland are exported (domestically or internationally), and many inputs and consumer products for the rural population are imported. It is arguable, therefore, that with the possible exception of a few of the biggest cities, it makes sense for rural areas and the cities they surround to be governed as integral units, since each is so heavily dependent on the other. That said, the larger cities are probably justified in also having their own special form of local government.

10 July 2000

NOTES

* With contributions from Terry Hull and Chris Manning, ANU.

1 The Minister for Industry and Trade, Yusuf Kalla, was dismissed at the same time, but this has met with little criticism from those concerned with good governance.

2 This was not the agency’s preferred estimate of growth, as many seem to have assumed.

4 BI operates in the interbank money market, which also gives it some control over base money for fine tuning purposes, but its borrowing and lending here is only for periods of at most a few days.

5 The DPR eventually agreed to the recapitalisation (JP, 23/6/00).

6 The Basle Capital Accord is the international agreement on capital measurement and capital standards for banks <http://www.bis.org/publ/ bcbsc002.htm>.

7 BCA claimed a much higher CAR, apparently because many of its non-bond assets were also in zero risk-weight categories.

8 The recapitalised banks would need to sell bonds in order to ‘make room’ for new lending, but there is little appetite for new lending in current depressed and highly uncertain conditions.

9 Excluding those issued to BI.

10 Government borrowing is not conventionally regarded as ‘revenue’, so we are really talking about categories of cash inflows here.

11 It is not clear if this means 25% of gross domestic revenues, or 25% of domestic revenues net of the special funds allocation and the regions’ share of natural resource based revenues. The latter interpretation would seem more logical. 12 Some of the difficult issues this would raise include how differences in pay scales, recruitment and promotion systems, and pension liabilities to such civil servants, would be handled.

REFERENCES

BCA(2000), PT Bank Central Asia Tbk:Prospektus, 11 May, Jakarta.

Booth, Anne (1999), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 35 (3): 3–38.

Broening, Stephens (1998), ‘Voice of Suharto’s Guru Q & A/Steve Hanke’, International Herald Tribune, 20 March.

Brown, M.S. (2000). ‘BCA’s Initial Public Offering: Let the Buyer Beware’, Jakarta Post, 29–30 May.

Fane, George (2000), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 36 (1): 3–34.

—— (forthcoming), ‘Indonesian Monetary Policy during the 1997–98 Crisis: A Monetarist Perspective’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 36 (3). Hanke, Steve (1998), ‘How I Spent My Spring Vacation’, The International Economy,

July/August: 30–3.

Lindsey, Tim (2000), ‘Black Letter, Black Market and Bad Faith: Corruption and the Failure of Law Reform’, in Chris Manning and Peter van Diermen (eds), Indonesia in Transition: Social Aspects of Reformasi and Crisis, ISEAS, Singapore: 278–92.

—— (1993), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 29 (2): 3–42.

—— (1999), ‘Crisis-driven Changes to the Banking Laws and Regulations’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 35 (2): 147–54.

Mietzner, Marcus (2000), ‘The 1999 General Session: Wahid, Megawati and the Fight for the Presidency’, in Chris Manning and Peter van Diermen (eds), Indonesia in Transition: Social Aspects of Reformasi and Crisis, ISEAS, Singapore: 39–57.

Pardede, Raden (1999), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 35 (2): 3–39.

Schuler, Kurt (1999), ‘Dollarising Indonesia’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 35 (3): 97–113.

Soetjipto, Adi Andojo (2000), ‘Legal Reform and Challenges in Indonesia’, in Chris Manning and Peter van Diermen (eds), Indonesia in Transition: Social Aspects of Reformasi and Crisis, ISEAS, Singapore: 269–77.

SURVEY EXTRA

a collection of post-Survey developments compiled by Indonesia

Project staff

GDP growth in the year to June 2000 was 4.1%. During the same period household consumption grew by only 2.6%, suggesting that this has now come to be holding back recovery rather than ameliorating the recession. By contrast, investment grew by 21%—and by 5.5% in Q2 2000—which is a positive sign for recovery. But there was a dramatic jump in the

inflation rate in the month of July 2000 to 16.5% p.a., such that year-on-year inflation rose from only 2% in June to 5% in July. During June and July the rupiah first depreciated significantly but then recovered, for a net depreciation of about 4%. Base money stood at Rp 94,745 trillion at the end of July, nearly 7% above the May 2000 LOI target of Rp 88,750 trillion. Despite the central bank’s failure to meet this fundamental macroeconomic target, a new LOI was signed (after some delay) at the end of July.

The slow eclipse of former president Soeharto continued. In July, some real estate assets of foundations with which he was linked were seized by the attorney general’s office, and the banknote bearing his likeness began to be withdrawn from circulation (along with two other notes said to be often counterfeited). And at the beginning of August he was at last charged with corruption, his trial expected to commence within weeks. Meanwhile, in a reshuffle of top Army personnel in July, Army Strategic Reserve (Kostrad) Commander Agus Wirahadikusumah, who had earlier brought to light seeming financial irregularities involving a foundation managed by Kostrad, was sidelined.