In this paper, we analyze the evolution of foreign exchange exposure and currency mismatches in emerging market economies (EMEs) and investigate the causes of currency mismatches. The problem of original sin may lead to an increase in the use of FCD and is likely to cause currency mismatches in EDE. 2018) document that EMEs extend their currency exposure over the recent period and the literature on currency mismatches paid little attention.

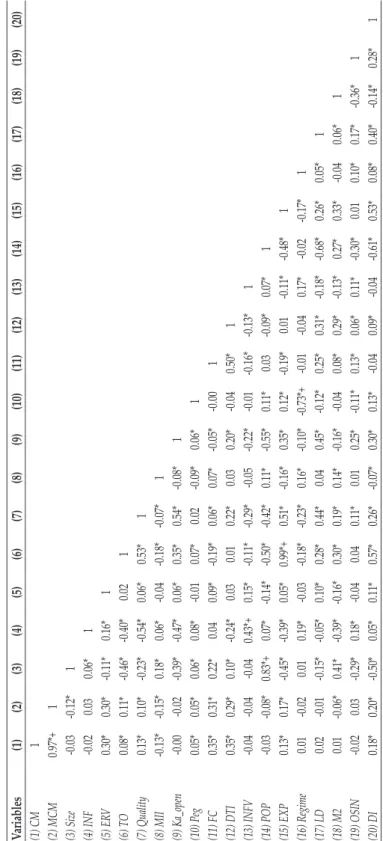

The panel regression methodology takes into account the time-varying and unobserved characteristics of the currency mismatch variables. In contrast, Goldstein and Turner (2004) and Özmen and Arinsoy (2005) argue that domestic factors are the main causes of currency mismatches. Baek (2013) empirically tests the determinants of currency mismatches using data from Lane and Shambaugh (2010a) on foreign currency exposures.

Measuring currency risk and currency mismatches in EMEs is challenging due to insufficient data. We apply the new methodology proposed by Kuruc et al. 2018) to measure currency mismatches in EMEs. Previous studies find monetary policy as an important determinant of currency mismatches in EDEs (Eichengreen et al., 2005b; Goldstein and Turner, 2004; Jeanne, 2005; Tobal, 2013).

The foreign exchange assets in domestic markets can increase credit facilities and decrease FCD, thereby reducing currency mismatches.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION A. Baseline Regression Results

Specifically, the results suggest that a country with high-quality institutions can issue debt in its own currency and thus limit the currency mismatch problem. One of the critical contributions of our study is to analyze the impact of monetary independence on currency mismatches. The index is "the reciprocal of annual correlation between monthly interest rates of the home country and the base country." The estimated coefficient on monetary independence is negative and significant, implying that a lack of monetary independence in EMEs exacerbates the currency mismatch problem.

The coefficient of Ka_open is positive, implying a higher degree of currency mismatch problem for financially liberalized countries. In fixed exchange rate regimes, low incentives to hedge currency risk create currency mismatches in EMEs. In model (2), we find that the coefficient of the peg is positive but statistically insignificant, implying that there is no strong evidence of the effect of pegged exchange rate regimes on currency mismatches.

We find that the coefficient of debt intolerance is negative and significant, suggesting that the share of total external debt in GDP determines the extent of currency misalignment. First, we use alternative variable comparison regressions to assess the robustness of our findings. The results presented in Table 8 confirm that large EMEs (in terms of population) have problems with currency misalignment.

In terms of currency risk, measured by exchange rate volatility, we find a relationship between bilateral exchange rate volatility and foreign currency debt position. We include exports as an alternative measure of trade openness, and the estimates are identical to those of the benchmark. The currency mismatch (CMi,t) method assumes that domestic bank loans and bonds are denominated in domestic currency.

Therefore, we include “the share of foreign currency in domestic bank loans to the private sector and the share of exchange rate-linked instruments in domestic public debt” in the modified version of the currency mismatch index according to Goldstein and Turner (2004). As expected, the inclusion of these two instruments increases the weight of the currency in total debt and the size of the currency mismatch in our sample. To examine the robustness of the estimates to this modification, we reestimate Eq. 4) using an alternative version of the currency mismatch (MCMi,t) as the dependent variable.

In contrast, we do not find the significant effect of capital openness and pegged exchange rate on the modified currency mismatch measure, but the coefficient on the flexible exchange rate regime index is significant in model (3). We include “the share of foreign currency in domestic bank loans to the private sector and the share of exchange rate-related instruments in domestic public debt” in the modified version of currency mismatch.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Currency mismatches, debt intolerance and original sin: why they are not the same and why it matters. The country chronologies of exchange rate regimes into the 21st century: Will the anchor currency last? The long or the short of it: Determinants of foreign exchange exposure in external balance sheets.

The role of macroprudential policy to manage exchange rate volatility, excess bank liquidity and credit. Pegi,t - dummy variable which takes the value of one for countries following the fixed exchange rate regime (Ilzetzki et al., 2018); Macroprudential policy indicators - foreign currency credit limits and debt-to-income ratio limits are denoted as (FCi,t) and (DTIi,t). Countries with a large size in terms of GDP or total population can lower the FCTD, and therefore they reduce currency mismatches.

However, large countries also issue more foreign currency debt, resulting in a net balance of foreign currency liabilities (Benetrix et al., 2015). The sign of the inflation coefficient is expected to be positive, indicating a larger currency mismatch or perceived currency risk due to a higher inflation rate (Reinhart et al., 2003; Goldstein and Turner, 2004; Baek, 2013). Exchange rate volatility can increase the value of foreign currency debt and increase the balance of foreign currency liabilities (Baek, 2013).

Furthermore, economies with a higher degree of trade openness have better access to foreign exchange assets and international financial markets than the closed economies (Eichengreen et al., 2005b; Baek, 2013). The institutional quality and monetary independence exacerbate the currency mismatches because a country with better institutional quality lowers the FCD and increases the share of domestic currency in foreign debt (Lane and Shambaugh, 2010b). Thus, countries with an open capital account hold debt in foreign currency, which increases the currency mismatches (Barajas and Morales, 2003; Park and An, 2012).

Furthermore, the effect of the exchange rate regime on currency mismatch is ambiguous – the floating exchange rate regime implies the hedging facility and lowers the currency risk, but increases the currency risk through the inflationary economy (Martinez and Werner, 2002; Hausmann and Panizza, 2003). Countries with a high level of development and financial development are expected to have lower currency mismatches. Finally, the original sin hypothesis and debt intolerance have a positive and negative influence on currency mismatch, respectively (Eichengreen et al., 2005b; Reinhart et al., 2003).