All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction.

SERMON APPLICATION IN THE DOCTRINAL PREACHING OF JOHN PIPER

__________________

A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of

The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

__________________

In Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy

__________________

by

James Daniel Detwiler December 2015

APPROVAL SHEET

MOVING FROM ORTHODOXY TO ORTHOPRAXY:

SERMON APPLICATION IN THE DOCTRINAL PREACHING OF JOHN PIPER

James Daniel Detwiler

Read and Approved by:

__________________________________________

Robert A. Vogel (Chair)

__________________________________________

Hershael W. York

__________________________________________

Michael A. G. Haykin

Date______________________________

To Jesus Christ,

from whom all true doctrine flows, who came preaching (Mark 1:38)

so that we might believe and obey (Luke 6:46-48), and to

Meredith, Eden, and Joelle, God’s good gifts, precious to me.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

LIST OF TABLES ... viii

PREFACE ... x

Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ...1

The Research Question ...2

Thesis ...4

Background ...5

Importance of Study ...7

Methodology Overview ...8

Delimitations ...10

2. THE SUBJECT OF STUDY: JOHN PIPER ...12

John Piper the Person ...12

John Piper the Pastor-Theologian ...14

John Piper the Preacher ...19

3. DEFINING ELEMENTS OF DOCTRINAL PREACHING AND SERMON APPLICATION ...25

What Defines Doctrinal Preaching ...25

Elements of Expository Preaching ... 28

Elements of Doctrinal Preaching ... 32

What Defines Sermon Application ...43

4. METHODOLOGY: A CRITICAL MODEL ...54

Chapter Page

Object of Analysis ...54

Method of Analysis ...56

The Six Qualities ... 58

The Four Purposes ... 71

The Doctrines Applied ... 75

5. SEGREGATED ANALYSIS OF THE SIX QUALITIES, FOUR PURPOSES, AND DOCTRINES APPLIED ...78

The Six Qualities ...78

Consistency ... 80

Creativity ... 83

Clarity ... 88

Recurrence ... 95

Cumulative and/or Climactic Effect ... 103

Contextualization ... 110

The Four Purposes ...116

Duty ... 117

Character ... 120

Goals ... 127

Discernment ... 135

The Doctrines Applied ...143

Anthropology ... 146

Bibliology ... 150

Christology ... 154

Ecclesiology ... 158

Eschatology ... 163

Hamartiology ... 168

Pneumatology ... 172

Chapter Page

Soteriology ... 179

Theology Proper ... 185

Summary of Segregated Analysis ...190

6. INTEGRATED ANALYSIS OF THE SIX QUALITIES, FOUR PURPOSES, AND DOCTRINES APPLIED ...191

Patterns of Quality ...191

Patterns of Purpose ...192

Patterns of Doctrine ...192

Patterns of Co-Occurrence ...195

Interplay of Quality, Purpose, and Doctrine ...205

Development over Time ...214

Development across Select Sermon Series ...222

Summary of Integrated Analysis ...234

7. CONCLUSION ...235

Key Insights ...236

Implications ...251

Suggestions for Future Research ...251

A Call to Doctrinal Fidelity, Expository Preaching, and Effective Sermon Application ...252

Appendix 1. RESEARCH GUIDE FOR ANALYSIS ...254

2. TAXONOMY OF DOCTRINE ...256

3. RESEARCH ANALYSIS SUMMARY ...259

4. SELECTED SERMONS BY DATE ...319

5. EXAMPLE OF SERMON ANALYSIS ...335

6. PIPER’S PREACHING BY SCRIPTURE ...342

7. PIPER’S PREACHING BY SERIES ...343

Appendix Page 8. PIPER’S PREACHING BY TOPIC ...345 BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 349

LIST OF TABLES

Table Page

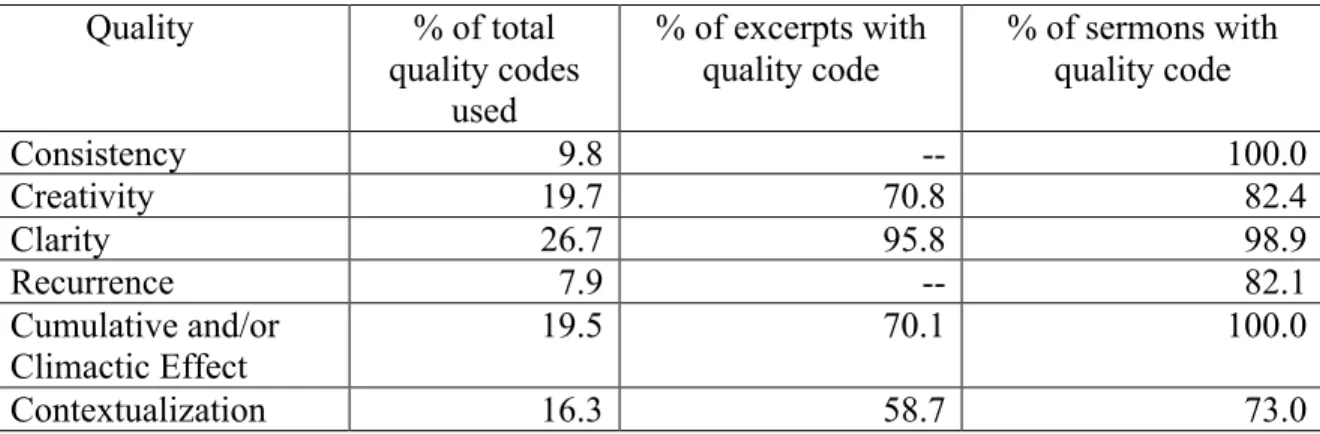

1. Distribution of quality codes ...79

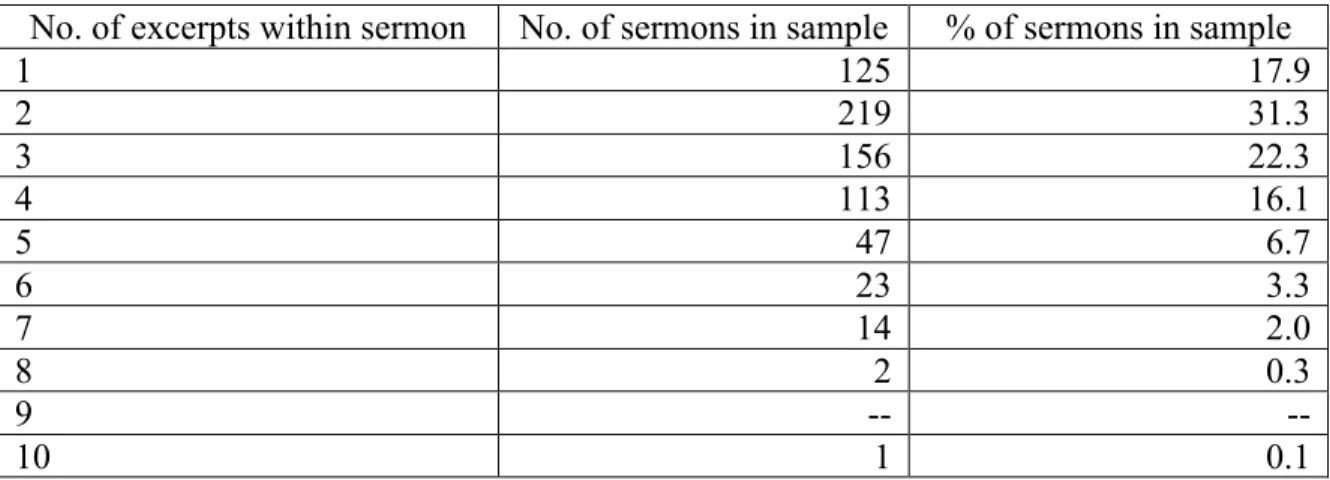

2. Distribution of sermon excerpts across sample ...96

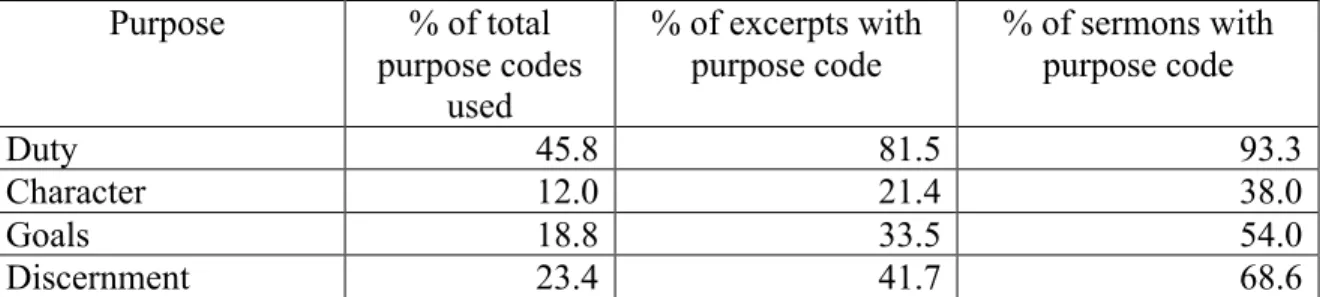

3. Distribution of purpose codes ...116

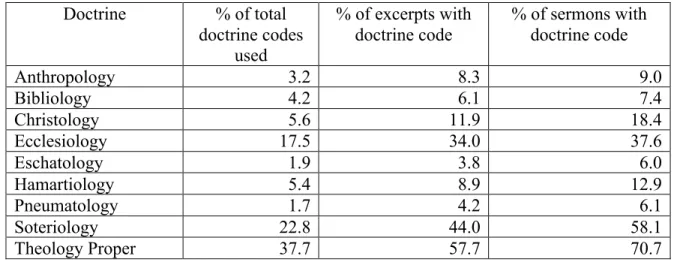

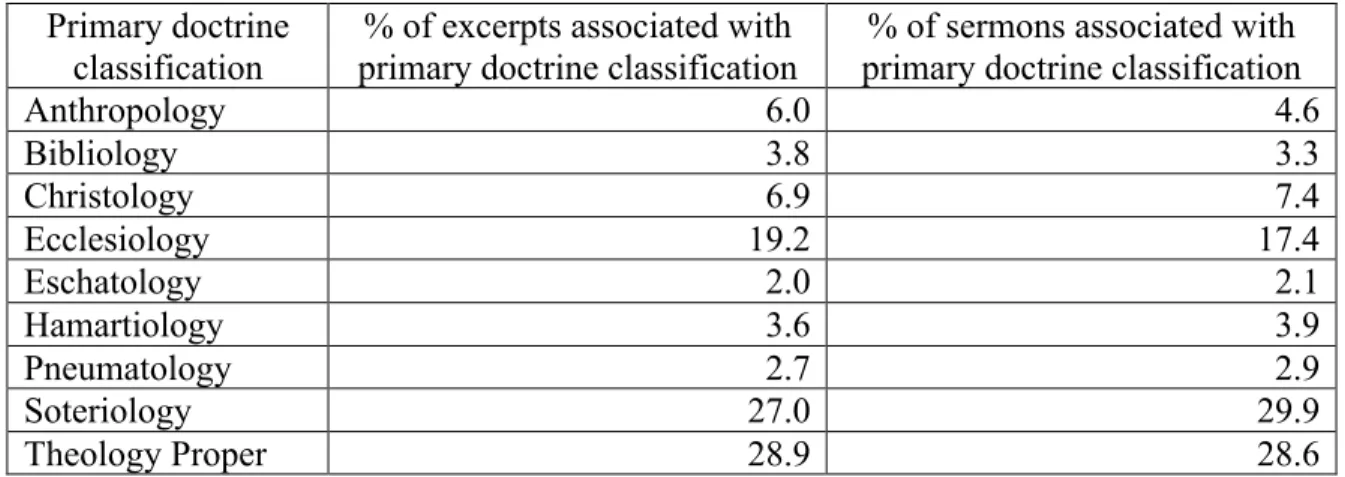

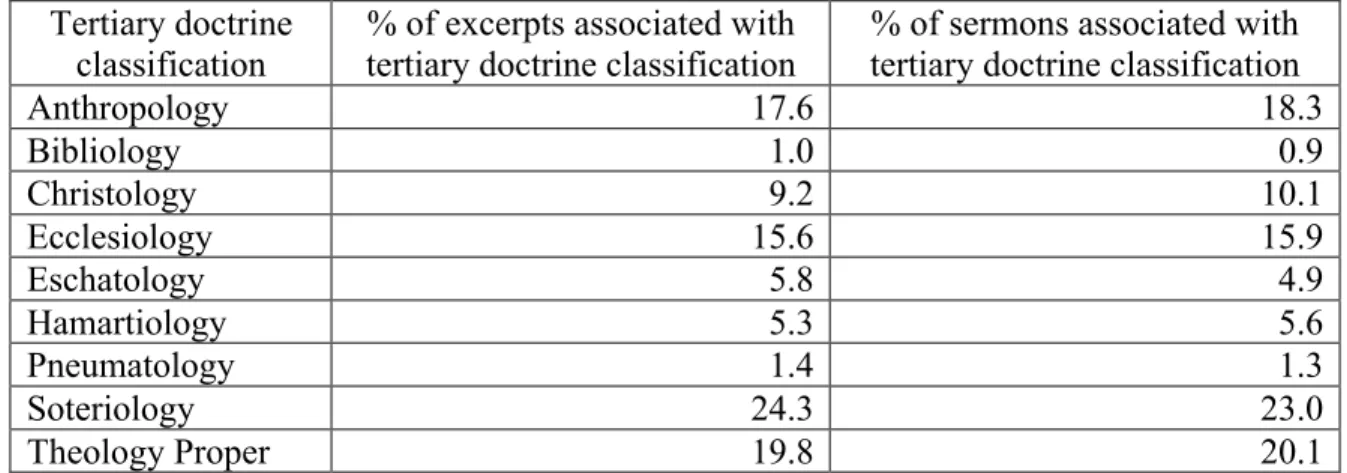

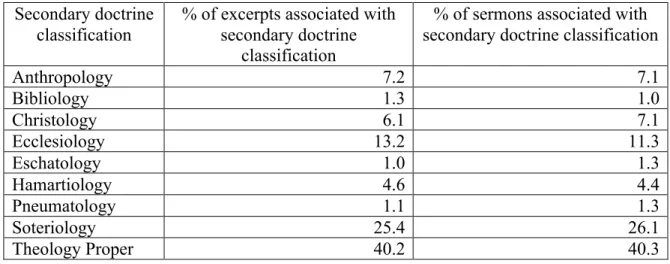

4. Distribution of doctrine codes, condensed format ...144

5. Distribution of primary doctrine metadata classification, across sample ...145

6. Distribution of secondary doctrine metadata classification, across sample ...146

7. Distribution of tertiary doctrine metadata classification, across sample ...146

8. Distribution of code co-occurrence (%), quality with purpose ...196

9. Distribution of code co-occurrence (%), purpose with purpose ...198

10. Distribution of code co-occurrence (%), quality with quality ...201

11. Distribution of quality codes (%), across sample, by primary doctrine metadata classification, normalized. ...202

12. Distribution of purpose codes (%), across sample, by primary doctrine metadata classification, normalized. ...203

13. Distribution of quality codes (%), across time, normalized ...215

14. Distribution of purpose codes (%), across time, normalized ...216

15. Distribution of quality codes (%), within ministry periods, normalized ...217

16. Distribution of purpose codes (%), within ministry periods, normalized ...218

17. Distribution of doctrine codes (%), across time, normalized ...220

18. Distribution of doctrine codes (%), within ministry periods, normalized ...221

Table Page 19. Percentage of sermons within select sermon series containing

quality code ...224 20. Distribution of quality codes (%) across select sermon series,

normalized ...225 21. Distribution of quality codes (%) within select sermon series,

normalized ...226 22. Percentage of sermons within select sermon series containing

purpose code ...227 23. Distribution of purpose codes (%) across select sermon series,

normalized ...228 24. Distribution of purpose codes (%) within select sermon series,

normalized ...229 25. Percentage of sermons within select sermon series containing

doctrine code ...231 26. Distribution of doctrine codes (%) across select sermon series,

normalized ...232 27. Distribution of doctrine codes (%) within select sermon series,

normalized ...233

PREFACE

I felt the call to preach in my early teens but took more than a decade to respond in obedience. Thanks be to God that my initial rebellion did not negate his call.

Jesus Christ is sovereign in all things, even the vocational training of such a wayward son. To him be glory and honor. I would like to thank several people for their support in this endeavor, including my committee members at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Dr. Robert Vogel, Dr. Hershael York, and Dr. Michael Haykin. Furthermore, I would like to express my sincere appreciation to Dr. Tom Stringfellow and Dr. Eddie Pate at Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary, who were both instrumental in my ministerial formation. In addition, I am especially grateful to three church families who helped make this project possible. It has been my great privilege to serve at First Baptist Church of Beverly Hills, California, Grace Bible Church of Barrington, New Jersey, and Ninth and O Baptist Church here in Louisville. Dr. Bill Cook and Dr. Jason Mackey, both at Ninth and O, have been particularly encouraging. I am also indebted to Rick Bristol, Paul Meredith, and John Merritt, good friends, co-laborers in education, and brothers in ministry. Finally, words can hardly express the herculean contribution my family has made toward this accomplishment. The Detwilers and Neighbors both share in this great reward, especially my wife, Meredith, and our two daughters, Eden and Joelle. Without their loving encouragement, none of this would have been possible.

James Detwiler Louisville, Kentucky

December 2015

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

The preaching ministry of John Piper is well-known. In contemporary evangelicalism, the man can rightly be considered a giant in the pulpit. I am greatly indebted to him and his ministry, having been significantly influenced by his preaching, teaching, and published works. Countless other seminarians, pastors, and lay people could undoubtedly say the same, as evidenced by the ever-growing popularity of the man and his work.1 For over three decades, John Piper served as Pastor for Preaching and Vision at Bethlehem Baptist Church.2 His influence has grown significantly over the past decade, due largely to the success of Desiring God (and the corresponding ministry) and the recent resurgence of Reformed belief within the American church. Piper has emerged as one of the most prominent figures within evangelical Christianity, alongside the likes of R. Albert Mohler Jr. and John MacArthur. His accomplishments are numerous, and he continues, through his preaching, to influence both pastors and lay people on a global

1The reach of John Piper’s ministry is astounding, aided dramatically by the digital age. In 2014, Jon Bloom commented on this tremendous worldwide impact, writing, “By God’s grace, the result has been this: in our first 12 years we mailed out about 500,000 resources, but in the last 12 months we had 22 million visits to our website (about 5.5 million of which were from outside the U.S.), and this number has doubled in less than three years.” Jon Bloom, “22 Million Reasons to Pray With Us,” accessed May 13, 2014, http://www.desiringgod.org/blog/posts/22-million-reasons-to-pray-with-us. From July 2010 to April 2011, 24.5 million audio and video files were downloaded from the Desiring God website. This does not include files downloaded from the Bethlehem Baptist Church website, which also houses Piper’s sermons.

See Jon Bloom, “Spreading Mission,” accessed September 4, 2012, http://www.desiringgod.org/blog/posts/

a-year-to-date-review-of-desiring-gods-spreading-mission.

2Piper transitioned out of this position in 2012. He continues to be actively involved in the ministries of Desiring God, Bethlehem College and Seminary, and Bethlehem Baptist Church (in a significantly reduced capacity). See David Mathis, “Update on John Piper’s Transition,” accessed August 20, 2014, http://www.desiringgod.org/blog/posts/update-on-john-piper-s-transition. Also see John Piper,

“My Future at Desiring God,” accessed August 20, 2014, http://www.desiringgod.org/blog/posts/my- future-at-desiring-god. Finally, see John Piper, “Transition Questions and Answers from Pastor John for Bethlehem,” accessed August 20, 2014, http://www.desiringgod.org/articles/transition-questions-and- answers-from-pastor-john-for-bethlehem.

scale.3 As such, the preaching ministry of John Piper is an excellent subject for homiletical study.

The Research Question

In Truth Applied, Jay Adams addresses the critical role of sermon application in the preaching enterprise. Adams contends that “preaching is truth applied.”4 Daniel Doriani also speaks to sermon application’s importance in both Getting the Message and Putting the Truth to Work.5 Doriani claims that “sound application is difficult, and therefore deserves our best attention.”6 Adams’s and Doriani’s contributions are noteworthy, yet additional research would be beneficial to the field of homiletics.

Specifically, what are some of the defining qualities of effective sermon application?

Furthermore, how do these qualities function in the preaching of a well-known expositor?

Finally, how might Doriani’s work, as it relates to purpose in sermon application, be utilized as a critical model of analysis?

Like Adams and Doriani, many homileticians have argued that application is necessary in preaching, especially in expository preaching.7 However, some biblical texts

3Piper’s profile is available on the website of Desiring God. See Desiring God, “About Desiring God,” accessed August 20, 2014, http://www.desiringgod.org/about/john-piper/overview. Piper has degrees from Wheaton College, Fuller Seminary, and the University of Munich. Prior to his pastorate at Bethlehem, Piper spent six years as an Associate Professor of Biblical Studies at Bethel College, St. Paul, MN. He has published over eighty books and is a regular speaker at such events as Together for the Gospel, the Passion Conference, and the Gospel Coalition National Conference.

4Jay E. Adams, Truth Applied: Application in Preaching (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1990), 39. Adams writes, “In applicatory preaching there is no need to think about how to apply any given portion of the sermon. The entire sermon should be aimed at one and the same objective: achieving the telos of the passage.” Ibid., 41. When handling a text, telic analysis is required in order to determine not only the God-intended meaning, but the God-intended purpose, which is “by its very nature, applicatory.”

Ibid., 39. Adams’s method centers on “abstracting the application”—a process of principilization and re- contextualization. Ibid., 45-55, 131-37. Adams also discusses application in relation to sermon format, introductions, conclusions, illustrations, examples, and language. See also Jay E. Adams, Preaching with Purpose: A Comprehensive Textbook on Biblical Preaching (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1982).

5See Daniel M. Doriani, Getting the Message: A Plan for Interpreting and Applying the Bible (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 1996) and idem, Putting the Truth to Work: The Theory and Practice of Biblical Application (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2001).

6Doriani, Getting the Message, 127.

7This point is developed in chap. 3.

seem tailor-made for sermon application, while other parts of Scripture present difficulties in application. The concrete biblical imperatives of the New Testament epistles fall into the former category. Yet, what about abstract theological concepts articulated as Christian doctrine? Should doctrine be relegated to the cognitive domain only, or should doctrinal content impact the affective and behavioral domains also?

Adams argues for the latter; in preaching, doctrine should be applied. Compared to the paraenetic passages of the Bible, doctrinal texts might not seem as readily applicable to life, but preachers should remember that doctrine was given for a purpose. For example, addressing the Christology of Philippians 1:27-2:13, Adams writes,

Certainly this section, containing some of the highest doctrinal teaching regarding the deity and incarnation of Christ, presents truth (doctrine) applied. Paul’s concern is not to teach doctrine as such. But he does teach it—for a purpose . . . the doctrine in the passage is given for a practical purpose; it is not taught academically. It is truth applied. This means that doctrinal truth should be preached as practical truth and forcefully applied to people.8

Like Adams, Doriani believes preaching, regardless of content, should include application (what Adams would call “truth applied”)—even preaching which

significantly incorporates doctrinal concepts and themes:

Sound doctrine does fortify the church . . . every passage, whether narrative, sermon, epistle, vision, praise, lament, or legal code, generates doctrine . . . [and]

since all Scripture describes or reflects upon God’s acts of redemption, all of it has theological interests and doctrinal implications . . . [therefore] all Scripture is doctrinal.9

Still, the following question arises: How does sermon application function in preaching distinguished by its doctrinal character? Examining the practice of a preacher known for

8Adams, Truth Applied, 41.

9Doriani, Putting the Truth to Work, 213-14. Doriani and Adams are not the only ones who hold this belief. Many homileticians believe doctrine is inherently applicatory. See Joel Breidenbaugh, Preaching for Bodybuilding: Integrating Doctrine and Expository Preaching in a Postmodern World (Bloomington, IN: CrossBooks, 2010); Millard J. Erickson and James L. Heflin, Old Wine in New Wineskins: Doctrinal Preaching in a Changing World (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1997); Robert G.

Hughes and Robert Kysar, Preaching Doctrine: For the Twenty-First Century (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1997); and Robert Smith Jr., Doctrine that Dances: Bringing Doctrinal Preaching and Teaching to Life (Nashville: B&H Academic, 2008).

doctrinal exposition should contribute to a better understanding of the relationship

between sermon application, preaching, and doctrine. Because John Piper demonstrates a unique “skill, character, and preparation” in terms of preaching, doctrinal exposition, and sermon application, the study of Piper’s preaching, specifically his application of

doctrinal concepts and themes, is fitting.10

Accordingly, the purpose of this research is to answer the following question:

How has John Piper practiced sermon application in his doctrinal preaching over the past four decades? By analyzing the work of a specific preacher, the theory and best-practices of effective sermon application may be tested. The results of this analysis should prove practically informative as a model for the effective use of application in doctrinal preaching.

Thesis

Expository preaching requires sermon application; this includes the kind of expository preaching which significantly emphasizes doctrinal concepts and themes, that is, doctrinal preaching.11 Doctrinal preaching does not stop at mere exposition of

doctrinal texts or communication of doctrinal truths. Application of the doctrinal truth, as derived from the biblical text(s), necessarily follows. John Piper demonstrates this

principle by intentionally and methodically applying doctrine throughout his preaching corpus. He adeptly connects abstract concepts to concrete applications, moving from doctrinal theory to doctrinal practice. As such, John Piper’s preaching can rightly be classified as doctrinal preaching with an eye towards application. Working from these basic premises, this dissertation argues that Piper’s sermon application in doctrinal

10Doriani writes, “Compelling application depends on exegetical skill, character, and preparation for all kinds of listeners.” Doriani, Getting the Message, 130.

11Chap. 3 explores the relationship between expository and doctrinal preaching and establishes some key definitions.

preaching is characterized by multifaceted purpose, consistency, creativity, clarity, recurrence, cumulative and/or climactic effect, and contextualization.

Background

It is not an overstatement to say that I would not be where I am in life if not for John Piper. In the spring of 2005, I first encountered his preaching ministry through the Internet. I was studying the works of J. I. Packer, R. C. Sproul, John MacArthur, and others, with the hope of soon beginning seminary education. As I engaged their material and listened to their sermons on the radio, I discovered that much of their preaching was being published on the Internet. I kept seeing the name John Piper mentioned on these websites. I soon sampled one of his audio recordings. After all, Piper was in such good company. From that moment, I was hooked on Piper’s preaching. I especially remember downloading his influential sermon series on Romans and listening to each message consecutively in the span of a few weeks (I believe at that point he was already seven years into the series). As my hunger for his preaching grew, I came to realize I knew very little about him. I was aware that he had written a popular work entitled Desiring God, that he was a superb expository preacher unlike any I had ever heard, and that he pastored Bethlehem Baptist Church in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Since I was not raised Baptist, I knew little about Baptist churches or denominations. At this point though, what I did know was that John Piper, this marvelous preacher, was Baptist.

In 2005, my wife and I moved to Los Angeles to pursue job opportunities. We were at the same time looking for a good church and a good seminary to attend for ministry training. A friend suggested we consider Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary, as it had a Southern California campus nearby. My wife and I knew little about the school except that it was evangelical and Baptist. As stated above, we were also looking for a good church. I searched the Internet for local options and came across the First Baptist Church of Beverly Hills, California. We knew nothing about the church

except that, like the seminary, it was evangelical and Baptist. Yet, we did know that John Piper, whom we both greatly admired and trusted, was also Baptist, and thus decided to visit the church and contact the seminary. The rest, as they say, is history. I would later go on to graduate from Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary with a Master of Divinity degree and become the pastor of the First Baptist Church of Beverly Hills, California.

In the summer of 2010, I applied for a church planting internship at Bethlehem Baptist Church, where John Piper pastored. Each year, the church offered internships to two individuals, selected from a pool of several dozen applicants. I was Bethlehem’s third choice, missing the cut by one. Disappointed, I sought God’s direction (and comfort) once again. Soon afterward, I developed a desire for further theological education, with an emphasis on pastoral ministry and preaching. After all, in my eyes, John Piper, the man I so greatly admired, was the consummate pastor-theologian. If Piper profited so much from advanced theological study, surely I would too. I quickly learned that The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary offered a PhD in Christian Preaching.

As a native Kentuckian with strong connections to the Bluegrass State, I knew this was the next step for me, my family, and my ministry. By the beginning of 2011, we had relocated to Kentucky, and I had begun doctoral studies at another Baptist institution.

During my doctoral course work, I continued to study the preaching ministry of John Piper, first in an expository preaching seminar, then in a doctrinal preaching course, and finally in a seminar on rhetorical criticism and preaching. In addition, Piper’s work frequently came up during colloquium conversations. A pattern of study was definitely emerging.

Furthermore, I remember Dr. Hershael York’s mentioning in his doctrinal preaching seminar the lamentable paucity of good doctrinal preaching resources currently available in contemporary scholarly circles. Even though expository preaching had experienced a significant revival in the last twenty five years or so, not much had been

said about doctrinal preaching specifically. In addition, although many expository preaching resources touched upon sermon application, few focused on application entirely. At that point, I realized that these deficiencies not only needed to be addressed, but could be addressed by my doctoral dissertation.

Importance of Study

Doctrinal preaching is an important part of pastoral ministry. Communicating foundational Christian truth to a congregation in a systematic way should be regularly practiced by every evangelical pastor. John Piper knows this well, as evidenced by his passion for Christian doctrine and doctrinal preaching. Piper correctly recognizes that sermons must speak to both heart and mind. Thus, even when Piper is tackling complex Christian doctrine from the pulpit, he preaches to both head and heart. The goal is not simply knowledge, but the excitement of the affections and other appropriate forms of congregational response. Doctrine is always applied. Therefore, I believe the topic of doctrinal preaching, specifically application in doctrinal preaching, is a worthy subject of study, considering the lack of relevant resources currently available.

Despite the expansive shadow John Piper currently casts on modern evangelicalism, scholarly work which examines, analyzes, and evaluates the man’s preaching is difficult to find. He is the topic of a handful of doctoral dissertations (pastoral or theological in scope) and has been the subject of at least one compilation of essays in tribute, yet nothing else exists at this point. Perhaps the research community prefers to wait until a person is deceased before evaluating his or her legacy, but I cannot imagine a world in which the contributions of John Piper are not considered significant, at least by evangelical Christians. It is the perfect time to capitalize on both the popularity of John Piper and the current availability of his massive sermon library.

Aspiring preachers who wish to preach doctrine well, with effective sermon application, should be particularly interested in this study. Although it is not my intention

to convince aspiring pastor-theologians to preach like John Piper in terms of style or voice, I do hope that readers will see considerable value in adopting Piper’s philosophy and methodology of sermon application in doctrinal preaching. Furthermore, I hope this specific evaluation of Piper’s homiletic helps them better understand how Piper’s preaching functions in general. Upon completion of this dissertation, the reader should not only understand how Piper approaches doctrinal preaching and sermon application, but how he executes the two so successfully, and why it matters to future generations of preachers.

Methodology Overview

This dissertation examines the preaching of John Piper, specifically his use of application in doctrinal preaching. Therefore, a major portion of the research necessarily consists of a critical analysis of Piper’s sermons. I utilize a stratified, non-random sample of sermons, chosen from the Desiring God website archive (some 1,300 available

messages).12 Thankfully, sermon audio, video, and manuscripts are available.13 The following criteria determine the sample.

First, each selected sermon had to address at least one biblical doctrine (e.g., election) from the loci of systematic theology.14 Treatment of the doctrine had to be substantive, not tangential. However, the central idea of the sermon did not have to be derived from or focus on one particular doctrine, although this was often the case.

Frequently, sermons expounded and applied multiple doctrines. Hence, sermons were

12Strata include five-year ministry periods and select sermon series.

13As noted by Tony Merida, the Desiring God website provides the manuscripts that Piper used from the pulpit, unless otherwise stated. See Tony Clifford Merida, “The Christocentric Emphasis in John Piper’s Expository Preaching” (Ph.D. diss., New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, 2006), 47. This fact was independently confirmed. Desiring God, e-mail message to author, June 18, 2015. Despite the occasional minor departure from the manuscript (e.g., a substitution in language or an extemporaneous comment), as a rule, the live recordings of Piper’s sermons follow his manuscripts.

14The relationship between doctrinal preaching and systematic theology will be discussed in chap. 3.

assigned primary, secondary, and tertiary doctrine classifications. By meeting this criterion, this study’s focus on doctrinal preaching was satisfied.

Second, a variety of biblical doctrines had be represented, to show Piper’s practice across a spectrum of doctrinal subjects. Does he emphasize certain doctrines, and if so, are these doctrines more suited to application? Does he favor particular doctrinal themes, and if so, why? Again, these doctrinal subjects were identified and classified by the loci of systematic theology. The focus of this research is doctrinal preaching, not preaching on every possible topic that falls within the church’s larger body of teaching.

The loci of systematic theology provides the necessary delimitation in this regard.15 Third, sermons from each five-year period of Piper’s ministry had to be included (e.g., 1980-1984), in relatively equal numbers, except when the number of available sermons within a period was limited (e.g., 1970-1979) or when a select sermon series, included in its entirety, contained a disproportionate number of sermons (e.g., Romans). Yet, in these cases, the normalization of data in statistical analysis provides a balancing effect.16 Similar to the previous criterion, a truly representative sample would examine Piper’s practice over time. Does Piper’s application of doctrine evolve over nearly four decades of preaching? If so, what might explain such change?

Fourth, a minimum of 50 percent of the doctrinal sermons available must be included. Analyzing a majority increases the likelihood that Piper’s normative practice is actually represented. Typical patterns may emerge, as well as occasional or exceptional features in his doctrinal preaching and its application. The criteria listed ensure an accurate and comprehensive representation of John Piper’s doctrinal preaching.

I employed a critical model of analysis which identifies and tracks the

15As mentioned previously, chap. 3 defines doctrinal preaching in relation to the loci of systematic theology. Additionally, chap. 4 further clarifies the function of this criterion as it relates to systematics.

16Regarding normalization and data analysis, see chap. 4.

following six qualities of application in Piper’s doctrinal preaching, as drawn from the thesis statement above: (1) consistency; (2) creativity; (3) clarity; (4) recurrence; (5) cumulative and/or climactic effect; and (6) contextualization.17 Furthermore, I drew on the work of Daniel Doriani. Specifically, his “four aspects of application”—duty, character, goals, and discernment—are utilized, as they relate to Piper’s use of

multifaceted purpose in sermon application.18 In addition, I analyzed the kinds of doctrine Piper applies in his preaching.

Piper’s own writing on homiletics, the pastorate, and the importance of Christian doctrine in preaching is also explored. As it relates to Piper’s preaching, selected scholarly literature on sermon application and doctrinal preaching is engaged.

Finally, some biographical material on Piper’s life, ministry, influence, and legacy is provided.

Delimitations

This research is not a study of Piper’s theology or philosophy of ministry, although his personal beliefs and core convictions certainly influence his preaching.

Piper’s published works are impressive and explicitly reflect his theology and

philosophy. His numerous books are readily accessible and can be consulted. I cannot improve upon what Piper himself has written concerning these things. The main focus of this study is his sermons. Nevertheless, where relevant to his preaching, his theological, philosophical, and pastoral writings are engaged.

17This model originated through preliminary study of sermon application in expository preaching. While none of the six qualities are original, the combination is. Chap. 4 will include a justification of this critical model.

18See chap. 5, “The Four Aspects of Application,” in Doriani’s Putting the Truth to Work.

Doriani addresses four categories of application: duty, character, goals, and discernment. He writes,

“People ask, and the Bible answers, these four essential questions: (1) What should I do? That is, what is my duty? (2) What should I be? That is, how can I become the person or obtain the character that lets me do what is right? (3) To what causes should we devote our life energy? That is, what goals should we pursue? (4) How can we distinguish truth from error? That is, how can we gain discernment?” Doriani, Putting the Truth to Work, 97-98.

Furthermore, this research is not an exhaustive study of Piper’s preaching. I focus on only one specific aspect of his preaching—the application of doctrine. Although great care has been taken to create a sufficient sample, one which truly represents Piper’s preaching, this research does not examine every sermon he has ever preached.

Admittedly, this study is limited by the criteria previously listed. However, I am

confident that the criteria employed and the sample utilized enable me to say confidently and definitively, “More often than not, John Piper’s sermon application in doctrinal preaching reflects the findings of this dissertation.”

CHAPTER 2

THE SUBJECT OF STUDY: JOHN PIPER

As previously stated, John Piper is a fitting candidate for study. Reasons include the following: (1) his evangelical influence; (2) his longevity in the pulpit; (3) his substantial body of work; and (4) his reputation as a doctrinal preacher par excellence.

This chapter explores the subject of the study through a biographical lens, specifically, his identity as a person, pastor-theologian, and preacher.

John Piper the Person

John Piper was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee, on January 11, 1946, to Bill and Ruth Piper, an itinerant evangelist and entrepreneurial homemaker, respectively.1 At an early age, John moved with his parents and older sister to Greenville, South Carolina, the place he would live until graduating high school and going off to college. These early years in the racially segregated American South impacted Piper in various ways,

particularly his view of race relations, a topic he addressed each year on Bethlehem Baptist Church’s “Racial Harmony Sunday.” His father and mother each significantly

1A biographical profile is available on the website of Desiring God. See Desiring God, “About Desiring God,” accessed August 20, 2014, http://www.desiringgod.org/about/john-piper/overview. Piper speaks about this influence during his Bethlehem Baptist Church candidating testimony on January 28, 1980. See John Piper, “John Piper’s Candidating Testimony,” accessed February 19, 2015, http://www.

desiringgod.org/sermons/john-pipers-candidating-testimony. For additional material, the following works all contain biographical treatments: Michael Douglas Lawson, “An Examination of the Influence of Jonathan Edwards on John Piper with Implications for Doctrinal Preaching” (Ph.D. diss., Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary, 2013); Tony Clifford Merida, “The Christocentric Emphasis in John Piper’s Expository Preaching” (Ph.D. diss., New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, 2006); Shawn Stanton Merithew, “Theological Tenets of the Evangelistic Ministry of John Piper During the Years 1980-2002”

(Ph.D. diss., The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2003); Sunghyun Pae, “A Study of John Piper’s Sermon Preparation: A Model for Pastors Who Emphasize the Supremacy of God in Expository Preaching”

(D.Min. thesis, Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary, 2011); Shin Woong Park, “A Study of John Piper as a Pastor-Preacher” (D.Min. thesis, Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary, 2009); and Michael James Taylor, “Doctrinal Exposition: An Analysis of John Piper’s Preaching Ministry” (Ph.D. diss., New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, 2014).

impacted John in their own unique ways, helping shape his character, calling, and Christian faith.2

Piper met Noel Francis Henry on June 6, 1966, at Wheaton College, where they both were students. Two years later, they married. In 1974, after time spent at Fuller Seminary in Pasadena, California, and the University of Munich, Germany, John’s studies were complete. The newly minted doctor moved his growing family (their first son, Karsten Luke, was born in 1972) to St. Paul, Minnesota, to begin teaching New Testament at Bethel College. During John’s six-year tenure as Associate Professor of Biblical Studies at Bethel, Noel would give birth to two additional sons, Benjamin John (1975) and Abraham Christian (1979).

In 1980, John left Bethel College in order to take a pastorate at Bethlehem Baptist Church3 in inner-city Minneapolis. The family would move into a house in the same neighborhood, only a few minutes walk to the church. In 1983, Noel gave birth to their fourth son, Barnabas William. On December 15, 1995, the Pipers adopted a two- month-old baby girl, Talitha Ruth.4

In late 2005, John was diagnosed with prostate cancer, leading to a sabbatical from BBC in 2006. Not surprisingly, the cancer treatment could not stop Piper from being productive, as he wrote What Jesus Demands from the World during that time.5 Piper would go on to say, “Don’t waste your cancer.”6 In 2010, Piper took an eight-

2David Livingstone, “Three Doors Down from a Power Plant,” in For the Fame of God’s Name: Essays in Honor of John Piper, ed. Sam Storms and Justin Taylor (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2010), 24-35. Also see John Piper, What’s the Difference? Manhood and Womanhood Defined According to the Bible (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 1990).

3Hereafter, referred to as BBC.

4John Piper, “Talitha Ruth Piper,” accessed May 28, 2015, http://www.desiringgod.org/

articles/talitha-ruth-piper. See also Noel Piper, “We Meet Talitha Ruth Piper,” accessed May 28, 2015, http://noelpiper.com/2009/11/14/we-meet-talitha-ruth-piper.

5Tim Brister, “Piper’s Update and the Pastor as Theologian,” accessed June 1, 2015, http://timmybrister.com/2006/06/pipers-update-and-the-pastor-as-theologian.

6John Piper, “Don’t Waste Your Cancer,” accessed June 1, 2015, http://www.desiringgod.org/

articles/dont-waste-your-cancer. Also see John Piper, Don’t Waste Your Cancer (Wheaton, IL: Crossway,

month sabbatical devoted to nothing but his and Noel’s personal refreshment.7 In 2012, after thirty-three years in the pulpit, Piper transitioned out of pastoral leadership at BBC, the only church he ever pastored.

John Piper the Pastor-Theologian

John Piper has always been a deep and serious thinker, although the call to either the pastorate or scholarship was not obvious in his early years.8 Piper writes,

Very quickly I knew that I would never be a preacher because by the time I was in junior high school, I could not speak in front of any group. I was paralyzed with anxiety about it and trembled so terribly and choked up so completely that it was physically impossible to read or speak before any size group. Don’t imagine your average person with butterflies. Imagine physical impossibility. So preaching and the pastorate were totally ruled out of my dreams. Moreover, there was no apparent vision for scholarship in my home. It was not even a category in our minds, or a word in our vocabulary. . . . So pastoring was not an option because of my disability (or whatever it was), and scholarship was a nonexistent category when I went to high school. But I was a believer. I loved Jesus. I hated sin. I feared God in a good way. I took heaven and hell and salvation and the gospel very seriously. They were dominant realities in my life. And so the seeds of ministry were there. But there was no dream to be a pastor and no awareness that there even was such a thing as

scholarship.9

2011).

7John Piper, “John Piper’s Upcoming Leave,” accessed June 1, 2015, http://www.desiringgod.

org/articles/john-pipers-upcoming-leave. Piper writes, “The difference between this leave and the sabbatical I took four years ago is that I wrote a book on that sabbatical (What Jesus Demands from the World). In 30 years, I have never let go of the passion for public productivity. In this leave, I intend to let go of all of it. No book-writing. No sermon preparation or preaching. No blogging. No Twitter. No articles.

No reports. No papers. And no speaking engagements.”

8Albert Mohler explores the idea of the “pastor-theologian” in his three-part work, “The Pastor as Theologian.” Mohler writes, “Every pastor is called to be a theologian. This may come as a surprise to some pastors, who see theology as an academic discipline taken during seminary rather than as an ongoing and central part of the pastoral calling. Nevertheless, the health of the church depends upon its pastors functioning as faithful theologians—teaching, preaching, defending and applying the great doctrines of the faith.” R. Albert Mohler Jr., “The Pastor as Theologian,” accessed June 1, 2015, http://www.sbts.edu/wp- content/uploads/sites/5/2010/09/the-pastor-as-theologian.pdf. On his blog, Mohler further connects theology to pastoral preaching, writing, “As a theologian, the pastor must be known for what he teaches, as well as for what he knows, affirms, and believes. The health of the church depends upon pastors who infuse their congregations with deep biblical and theological conviction. The means of this transfer of conviction is the preaching of the Word of God. We will be hard pressed to define any activity as being more inherently theological than the preaching of God’s Word. The ministry of preaching is an exercise in the theological exposition of Scripture. Congregations that are fed nothing more than ambiguous ‘principles’

supposedly drawn from God’s Word are doomed to spiritual immaturity, which will become visible in compromise, complacency, and a host of other spiritual ills.” R. Albert Mohler Jr., “The Pastor As Theologian, Part Three,” accessed June 1, 2015, http://www.albertmohler.com/2006/04/21/the-pastor-as- theologian-part-three/.

9John Piper and D. A. Carson, The Pastor as Scholar and the Scholar as Pastor: Reflections on

As a young man, Piper was reluctant to pursue pastoring or teaching and sought a different vocation:

I knew when I was done [with high school] that I could not speak in front of any group, and I was deeply troubled and anxious about my future—what kind of job would help me avoid that? And I knew also that I read painfully slowly. To this day, I cannot read faster than I can talk. Something short-circuits in my ability to

perceive accurately what’s on the page, when I try to push beyond that—probably some form of dyslexia. Those two disabilities, paralysis before people and painfully slow reading, I knew would keep me out of any profession that demanded great quantities of reading and any public speaking.10

Despite his weaknesses, as a natural-born thinker, Piper grew to excel at the disciplines of critical thinking, careful reading, and meticulous writing. Piper states,

“These were two huge impulses feeding into who I am in ministry: painstaking observation of texts and the demand for precise thinking—from myself and from others.”11 This precision of thought and language is obvious not only in his published works, but his sermons also. It is not surprising that two of Piper’s favorite authors, C. S.

Lewis and Jonathan Edwards, were both great thinkers. Their writings significantly influenced Piper’s development.

At Wheaton, his initial intention was to become a medical doctor, until a bout of mononucleosis, an eventual breakthrough regarding his fear of public speaking, and the preaching of Harold John Ockenga and John Stott changed his mind.12 Knowing that he wanted to study the Bible further and learn the skills necessary for careful exegesis and exposition, Piper decided to attend seminary. His time at Fuller Seminary,

particularly his relationship with Daniel Fuller, proved crucial to his development into a pastor-scholar:

For me it proved to be the most decisive time of my life theologically and

Life and Ministry, ed. Owen Strachan and David Mathis (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2011), 26-27.

10Piper and Carson, The Pastor as Scholar and the Scholar as Pastor, 29.

11Ibid., 28.

12Piper, “John Piper’s Candidating Testimony.”

methodologically. And the key living person under God was Daniel Fuller. . . . Nobody thought more rigorously than Dan Fuller. Nobody was more riveted on the biblical text in his exegetical method than Dan Fuller. . . . Nobody was more jealous to think the author’s thoughts after him, because that’s what meaning was—

the author’s intention . . . Nobody was more practically committed to the truth and authority of Scripture than Dan Fuller. Nobody communicated a greater gravity of the ultimate things at stake in biblical truth. . . . Nobody was more committed to showing that much reading is not the essence of scholarship, but that assiduous, detailed, meticulous, logical analysis of great texts can lift you to the level of the greatest minds. Nobody pierced to the essence of true scholarship the way Dan Fuller did.13

Not surprisingly, John Piper came to embody the very traits he so admired in his mentor, Daniel Fuller. After seminary, he would earn his doctorate from the

University of Munich (his application was rejected by Princeton). His dissertation topic was Jesus’s command to love.14

Piper would go on to serve as a faculty member of Bethel College for six years. He recalls, “These were heady days as I stretched my academic wings. I loved writing. I loved teaching.”15 Although Piper would eventually leave Bethel to become pastor of Bethlehem, his love of scholarship, particularly theology, would not wane. In fact, this love would transfer to the pastorate, although it would require change:

By the end of that sabbatical [from Bethel], the battle was over, and I had resolved to leave teaching and seek a pastoral position. I longed to see the Word of God applied in preaching to the whole range of ages and life situations. . . . I knew what this would mean to leave the world of academia. It would mean no more summers free to read and study and write; endless administrative pressures and challenges; an uncontrollable schedule; an audience who would not want or reward academic prowess but pastoral warmth and presence; funerals and weddings and baptisms and

13Piper and Carson, The Pastor as Scholar and the Scholar as Pastor, 38-39.

14See John Piper, Love Your Enemies: Jesus’ Love Command in the Synoptic Gospels and the Early Christian Paraenesis (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2012). Regarding his doctoral experience, Piper writes, “What I saw in the theological educational system and state-church life in Germany confirmed most of what I did not want to become. Here were world-class scholars, whom everyone on the cutting edge in America were oohing and ahhing over, teaching in a way that was exegetically non-transferable,

insubordinate toward the Scriptures, and indifferent to the life of the church. . . . I used my Fuller-taught method of observation and analysis to research and write an acceptable dissertation, and then left Germany as quickly as I could. . . . I earned my doctorate. They mailed it to me a few months after I left. I took it out of the mailing tube in the fall of 1974 to see if it was real. I put it back in and have not looked at it since.

It’s still in the tube in a bottom drawer at home (I think), and no one has ever asked to see it. But, by God’s grace, it did get me my first job.” Piper and Carson, The Pastor as Scholar and the Scholar as Pastor, 41- 42.

15Piper and Carson, The Pastor as Scholar and the Scholar as Pastor, 43.

counseling and hospital visitation and emergencies and conflict resolution and staff management; relentless pressure to write a sermon or two or three every week; and that the days of publishing articles in NTS and Scottish Journal of Theology and Theologische Zeitschrift—the days of being on the cutting edge of any scholarly discipline—were over. But knowing all that, I could not resist any longer. The passion to preach and to see God shape and grow a church by the Word of God was overwhelming.16

While no longer an academic per se, John Piper would continue to be a serious thinker. The seeds planted in his teen and early-adult years would continue to bear

intellectual fruit. Regarding his transition from academic to pastor-scholar, Piper writes, The impulses from my high school days and from Wheaton are very much alive. I am a (very slow) reader, a thinker, a feeler, a writer, a lover of poetic power, and, I hope, in all these ways, a loyal shepherd who does not forsake the sheep when the enemy comes. I have written all my sermons in manuscript form (with very few exceptions), and I try to write them with manifest rooting in the text of Scripture, with clear thinking, with strong feeling, and with imaginative surprise.17

As a pastor, John Piper has flourished in his theological and pastoral writing and speaking. He has published over eighty books and is a regular speaker at events like Together for the Gospel, the Passion Conference, and the Gospel Coalition National Conference.18 Piper’s deep theological thought may best be represented in his work Desiring God, first published in 1986. This treatise on the doctrine of Christian

hedonism—”God is most glorified in us when we are most satisfied in him”—launched a significant theological movement within modern evangelicalism which continues to this day.19 What began as a book of “meditations” turned into a worldwide ministry, an annual conference for pastors, and the consuming theme of Piper’s life (and countless others throughout the world who have embraced Piper’s views).

Although Piper’s fame as a prolific writer and prophetic speaker has grown

16Piper and Carson, The Pastor as Scholar and the Scholar as Pastor, 44-45.

17Ibid., 45-46.

18Desiring God, “John Piper—Bibliography,” accessed May 28, 2015, http://www.desiringgod.

org/about/john-piper/bibliography.

19John Piper, Desiring God: Meditations of a Christian Hedonist (Sisters, OR: Multnomah Publishers, Inc., 2003), 288.

exponentially over the last three decades, his ascendancy has not diminished his

shepherd’s heart. If anything, his success in the former has been driven and supported by the latter. Friend and coworker David Mathis has painted an insightful, and endearing, portrait of John Piper, the pastor:

At Bethlehem I found the more everyday Pastor John, not merely the Big Name who rocked the Big Event with sixty minutes of preaching and book after book. I quickly learned that John is first and foremost pastor, not conference speaker or best-selling author. His speaking and writing flow from his everyday practice of steeping his soul in the Bible and shepherding the needs of his flock at Bethlehem.20

When Piper candidated at BBC in January 1980—an established church with a long and celebrated history—he had preached only a handful of sermons and never pastored (although he was a popular Sunday School teacher at a nearby church). At the time, the inner-city church was aging and in decline (85% were over the age of 65). It would have been easy for this “rookie” pastor to convince himself that the best years of the church were in the past and thus not worth the effort. On the other hand, it would have been just as easy for this once-great church to convince itself that such an

inexperienced pastor was not up to the task. In his candidating testimony, Piper remarked frankly,

When I look at this church, when I look at any church, I shake in my boots, frankly, because the responsibility of being a pastor is so awesome. And in a church like this, with around 700 members, with a very complex structure and tremendous amount of history and tradition behind it, it’s a little bit awesome and you need to think very seriously about whether you think somebody like me is capable of it.

When I ask myself: “Are you capable, Piper, of stepping into a situation like that or any other situation?” My answer is always, “No way. Who is sufficient for these things?”21

Nevertheless, BBC did in fact call John Piper, and he gladly accepted, after some encouragement from his father.22 Within just a few years, the church demographics

20David Mathis, “Who Is John Piper?” in For the Fame of God’s Name: Essays in Honor of John Piper, ed. Sam Storms and Justin Taylor (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2010), 38.

21Piper, “John Piper’s Candidating Testimony.”

22Ibid.

shifted dramatically, as Piper drew hundreds of young people to BBC through his

passionate preaching and visionary leadership. This early growth set the tone for the next thirty years of ministry, in which Piper would lead the church to do great things. The ministry flourished as additional staff was hired, building and expansion projects completed, church governance and membership policies updated, and education, discipleship, and missions programs launched. Eventually, BBC would grow into a multisite church with several thousand attending each week.23

Piper thrived in the pastorate, yet kept a foot in both the academy and the church. Through Bethlehem College and Seminary, where he still serves as Chancellor, he continues to teach.24 Through BBC, he shepherded God’s flock. He not only kept up with the current theological and pastoral trends, but established many through his prolific writing and preaching. Is this kind of man not the epitome of the pastor-theologian? Piper humbly reflects,

If I am scholarly, it is not in any sense because I try to stay on the cutting edge in the discipline of biblical and theological studies. I am far too limited for that.

What “scholarly” would mean for me is that the greatest object of knowledge is God and that he has revealed himself authoritatively in a book; and that I should work with all my might and all my heart and all my soul and all my mind to know and enjoy him and to make him known for the joy of others.

Surely this is the goal of every pastor.25

John Piper the Preacher

At his core, John Piper is a preacher. He writes, “The ministry of preaching has

23Livingston, “Three Doors Down from a Power Plant,” 33-34.

24In a recent commencement address at Bethel College and Seminary, Piper clearly stated one of the aims of the institution, demonstrating the critical relationship between theological scholarship and ministry, particularly how to discern and join God’s present actions in the world: “Higher education, therefore, at Bethlehem is the endeavor to build habits of mind and heart into the students that will make them competent life-long learners of what God is doing in the world—in their soul, in their family, their friendships, their church, their vocation, their city, their nation, their world, because glad-hearted, free, non- slavish, God-centered, Christ-exalting, friend-like obedience is rooted in and grows out of the soil of knowing what the Master is doing—what God is doing in all the spheres of life where he calls us to live.”

John Piper, “Friendship with Jesus and the Aim of Education in Serious Joy,” accessed May 29, 2015, http://www.desiringgod.org/conference-messages/friendship-with-jesus-and-an-education-in-serious-joy.

25Piper and Carson, The Pastor as Scholar and the Scholar as Pastor, 67.

been the central labor of my life.”26 Beginning with his senior sermon at Fuller Seminary, given March 24, 1971, all the way to his farewell message at BBC in late March 2013, John Piper has preached over 1,300 sermons, not to mention countless other addresses at conferences and events. In 33 years as BBC’s pastor, Piper amassed a sermon archive which spanned 54 books of the Bible, 76 separate series, and 130 different topics. The man will certainly leave behind a legacy of preaching for generations to come. Yet, from where does such longevity and power in the pulpit come? How does a person, virtually unable to speak in public for the first twenty years of life, become one of the great

preachers of our era? The answer can be found in the absolute sovereignty of God and his empowered Word. Piper’s preaching is clearly founded upon the inherent power of the Bible. In 1980, during his first sermon as the newly installed pastor of BBC, Piper set the tone for his future pulpit ministry:

The source of my authority in this pulpit is not—as we shall soon see—my wisdom;

nor is it a private revelation granted to me beyond the revelation of Scripture. My words have authority only insofar as they are the repetition, unfolding and proper application of the words of Scripture. I have authority only when I stand under authority. And our corporate symbol of that truth is the sound of your Bibles opening to the text. My deep conviction about preaching is that a pastor must show the people that what he is saying was already said or implied in the Bible. If it cannot be shown it has no special authority.27

Undoubtedly, John Piper takes the Word of God seriously. Consequently, the preaching of the Word is central to his theology of worship. He writes, “Preaching is worshiping over the Word of God—the text of Scripture—with explanation and exultation.”28 Piper’s approach to preaching, his methodology, follows this pattern of explanation and exultation, the latter being one of Piper’s key forms of sermon

26John Piper, “After Darkness . . . Light,” accessed May 28, 2015, http://www.desiringgod.org/

articles/after-darkness-light-video-from-geneva.

27John Piper, “The Wisdom of Men and the Power of God,” accessed August 20, 2014, http://www.desiringgod.org/resource-library/sermons/the-wisdom-of-men-and-the-power-of-god.

28John Piper, The Supremacy of God in Preaching, rev. and exp. ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2015), 11.

application.29 Piper’s goals are the following: (1) to explain the biblical text, particularly the theological and doctrinal significance; (2) to glorify God, particularly his sovereignty and supremacy; and (3) to exult in God’s revealed truth.30 In this sense, Piper directly links exposition to heartfelt response and life application. Seeing the truth of God, through exposition, leads to savoring God.31 Stirring up the affections, therefore, is a necessary part of true worship and should be one of the preacher’s aims.32 Accordingly, the stimulation of listener feeling or emotion is a valid form of sermon application (i.e., human response). However, affection should be anchored to God’s revelation:

There are always two parts to true worship. There is seeing God and there is

29As this dissertation unfolds, the connection between exultation and application will be shown. This dissertation views exultation, and doxology, as Piper’s primary means of applying biblical doctrine. See chaps. 4-6. The chief response (i.e., application) to the exposition of doctrine should be human exultation and divine glorification. Piper writes, “I have devoted most of my life to defending and explaining and applying this reality: God is glorified by our enjoying him. . . . I believe with all my heart that this truth is crucial to preaching and that preaching is uniquely suited for this truth . . . I believe this truth lies at the heart of biblically faithful, God-exalting, soul-saving, and soul-satisfying preaching.” Piper, The Supremacy of God in Preaching, 119.

30Piper argues, “Preaching is not just explaining or teaching. Preaching is heralding. Preaching is what a town crier does when there is a message from the king. . . . Preaching is more than teaching. It is, exultation in the Word. ‘Preach the Word’ means ‘exult in the Word.’ That is, announce it and revel in it.

Speak it as amazing news. Speak it from a heart that is moved by it.” John Piper, “Advice to Pastors:

Preach the Word,” accessed September 18, 2014, http://www. desiringgod.org/sermons/advice-to-pastors- preach-the-word.

31Piper writes, “What you believe about the necessity of preaching and the nature of preaching is governed by your sense of the greatness and the glory of God and how you believe people awaken to that glory and live for that glory.” John Piper, “Preaching as Expository Exultation,” in Preaching the Cross, ed. Mark Dever (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2007), 108. Piper continues, “If it is the purpose of God that we display his glory in the world, and if we display it because we have been changed by knowing and enjoying it, and if we know and enjoy it by beholding the glory of the Lord, and if we behold that glory most clearly and centrally in the gospel of the glory of Christ, and if the gospel is a message delivered in words to the world, then what follows is that God intends for preachers to unfold these words and exult over them—which is what I call expository exultation.” Ibid., 113.

32Piper contends that such preaching “exposes the all-satisfying God as he speaks and reveals himself in Scripture. And the mission of preaching is worship, and the matter of preaching is the manifold glories of God revealed in Scripture.” John Piper, “Preaching as Worship: Meditations on Expository Exultation,” Trinity Journal 16, no. 1 (Spring 1995), 40. According to Piper, the primary subject matter of preaching should be the knowledge of God, the glories of Christ, and the truths of the gospel. Piper continues, “When I call preaching ‘expository exultation’ that’s what I mean by ‘expository.’ ‘To expound Scripture,’ Stott says, ‘is to bring out of the text what is there and expose it to view.’ And what is there in Scripture mainly is God. The all-pervasive, all-important, all-surpassing reality in every text is God.

Whether he is commanding or warning or promising or teaching, he is there. And where he is, he is always supreme. And where he is supreme, he will be worshiped. Therefore the overarching, pervasive, relentless subject of preaching is God himself with a view to being worshiped.” Ibid., 36.

savoring God. You can’t separate these. . . . In true worship, there is always

understanding with the mind and there is always feeling in the heart. Understanding must always be the foundation of feeling, or all we have is baseless emotionalism.

But understanding of God that doesn’t give rise to feeling for God becomes mere intellectualism and deadness.33

Considering Piper’s prioritization of biblical exposition, it is not surprising that his sermons are saturated with doctrinal content. Furthermore, his entire preaching

ministry, and pastoral ministry for that matter, is driven by biblical doctrine, namely, the supremacy of God in all things. The sovereignty and majesty of God is Piper’s defining doctrine, especially as it relates to preaching.34 He contends,

Preaching is not simply teaching. Preaching is the heralding of a message permeated by the sense of God’s greatness and majesty and holiness. The topic may be anything under the sun, but it is always brought into the blazing light of God’s greatness and majesty in his word.35

Piper believes the intellect must be engaged by the great truths of Scripture in order for preaching to succeed. This “affair of the mind” produces a response of the heart.

True worship always combines the heart and the head . . . True worship does not come from people whose feelings are like air ferns with no root in the solid ground of biblical doctrine. The only affections that honor God are those rooted in the rock of biblical truth. . . . Strong affections for God, rooted in and shaped by the truth of Scripture—this is the bone and marrow of biblical worship. . . . [which] resists the assumption that intense emotion thrives only in the absence of coherent doctrine.36

For Piper, Christian worship, especially preaching, necessitates a faith which is unashamedly biblical and doctrinal. Without correct Christian knowledge and

understanding, one cannot properly worship God. In this way, biblical doctrine is integral

33Piper, The Supremacy of God in Preaching, 10-11. Piper views preaching as both “heralding”

and “teaching.” The former is the “public exultation over the truth” proclaimed, while the latter is the

“faithful exposition” of God’s Word.

34Piper’s concern for God’s sovereignty and majesty form one half of the Christian hedonism equation (i.e., the glory of God). The equation’s other half consists of the satisfaction which results when a person makes much of (glorifies) God. This human satisfaction, or joy, is expressed in exultation.

35John Piper, “Preaching as Expository Exultation,” in Preaching the Cross, ed. Mark Dever (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2007), 104-5.

36Piper, Desiring God, 102-4. See also idem, Brothers We Are Not Professionals: A Plea to Pastors for Radical Ministry (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2002), 73-79. Piper continues to emphasize the inextricability of biblical doctrine from Christian worship, preaching, etc. He exhorts pastors to become biblical theologians who study and preach the Scriptures systematically, always seeking to see how the biblical texts and doctrines “fit together into a glorious mosaic of the divine design.”