KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

AN INTEGRATED APPROACH

Second Edition

Ashok Jashapara

“This is an excellent book which manages to combine a consideration of the philosophy of knowledge with the practical discussion of what it means to

‘manage knowledge’ in an organisational context. This book integrates many disparate strands from the literature and in doing so provides a comprehensive and coherent coverage of this emerging area.”

Professor Sue Newell, Warwick Business School

Front cover image: © Getty Images www.pearson-books.com

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AN INTEGRA TED APPROACH

Second Edition

Jashapar a

As the economy increasingly moves towards a knowledge-based economy, the ability to manage knowledge becomes a matter of competitive survival. This textbook offers a clear, well-structured and interesting

introduction to knowledge management, with real-life case studies from well-known global organisations who are at the forefront of best practice. Many other books only address the subject partially, from a human resource, information systems or practitioner perspective. This is the fi rst textbook to bring together and integrate all these dimensions.

This engaging text offers a readable blend of theory and practice, making this the ideal resource for students studying knowledge management courses within business management, information science and computer science degrees at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

This textbook features engaging real-world examples throughout including a brand-new in-depth case study at the end of each chapter, covering topical issues in knowledge management. These case studies are all based on well-known organisations that have won MAKE (Most Admired Knowledge Enterprise awards), including Unilever, Infosys, Toyota, Tata and the World Bank.

Key features

• Offers comprehensive coverage of the most important ideas in knowledge management.

• Provides an excellent blend of theory and current managerial practice - including insights into best practice.

• Highlights the relevance of knowledge management ideas to all business functions and within any type of organisation.

• Case studies and vignettes from a range of sectors and organisations to illustrate the theory in practice.

• Features such as learning outcomes, exercises and questions for further thought aid refl ective learning.

About the author

Dr Ashok Jashapara is an internationally recognised expert in the fi eld of knowledge management and senior lecturer in knowledge management at Royal Holloway, University of London. He also has considerable consultancy experience in Europe and globally. He has published widely in leading books and journals and has won a number of awards for his writing.

CVR_JASH6852_02_SE_CVR.indd 1 16/11/2010 16:28

Knowledge Management

educational materials in management, bringing cutting-edge thinking and best learning practice to a global market.

Under a range of well-known imprints, including Financial Times Prentice Hall, we craft high quality print and electronic publications which help readers to understand and apply their content, whether studying or at work.

To find out more about the complete range of our publishing, please visit us on the World Wide Web at:

www.pearsoned.co.uk

Second Edition

Knowledge Management

An Integrated Approach

Ashok Jashapara

University of London (Royal Holloway)

Harlow Essex CM20 2JE England

and Associated Companies throughout the world Visit us on the World Wide Web at:

www.pearsoned.co.uk First published 2004

Second edition published 2011

© Pearson Education Limited 2011

The right of Ashok Jashapara to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying in the United Kingdom issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS.

All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. The use of any trademark in this text does not vest in the author or publisher any trademark ownership rights in such trademarks, nor does the use of such trademarks imply any affiliation with or endorsement of this book by such owners.

Pearson Education is not responsible for the content of third party internet sites.

ISBN: 978-0-273-72685-2

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jashapara, Ashok.

Knowledge management : an integrated approach / Ashok Jashapara. -- 2nd ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-273-72685-2 (pbk.) 1. Knowledge management. I. Title.

HD30.2.J38 2011 658.4'038--dc22 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 14 13 12 11 10

Typeset in 9/13 Stone Serif by 30

Printed by Ashford Colour Press Ltd, Gosport

This book is dedicated to the inspiring life of SPUD BAKHLE

(1929–2003)

for our numerous conversations over a glass of wine.

Custom publishing allows academics to pick and choose content from one or more texts for their course and combine it into a definitive course text.

Content choices include:

● chapters from one or more of our textbooks in the subject areas of your choice;

● your own authored content;

● case studies from any of our partners including Harvard Business School Publishing, Darden, Ivey and many more;

● third party content from other publishers;

● language glossaries to help students studying in a second language;

● online material tailored to your course needs.

The Pearson Education custom text published for your course is profession- ally produced and bound – just as you would expect from a normal Pearson Education text. You can even choose your own cover design and add your university logo.

To find out more visit www.pearsoncustom.co.uk or contact your local representative at: www.pearsoned.co.uk/replocator.

Preface xv

About the author xvii

Author’s acknowledgements xviii

Publisher’s acknowledgements xiv

Part 1 THE NATURE OF KNOWLEDGE

Chapter 1 Introduction to knowledge management 3

Chapter 2 The nature of knowing 33

Part 2 LEVERAGING KNOWLEDGE

Chapter 3 Intellectual capital 63

Chapter 4 Strategic management perspectives 89

Part 3 CREATING KNOWLEDGE

Chapter 5 Organisational learning 121

Chapter 6 The learning organisation 158

Part 4 KNOWLEDGE ARTEFACTS

Chapter 7 Knowledge management tools: component technologies 185

Chapter 8 Knowledge management systems 228

Part 5 MOBILISING KNOWLEDGE

Chapter 9 Enabling knowledge contexts and networks 261 Chapter 10 Implementing knowledge management 295

Epilogue KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

Epilogue 325

Glossary 340

Index 345

Brief contents

Preface xv

About the author xvii

Author’s acknowledgements xviii

Publishers’s acknowledgements xix

Part 1 THE NATURE OF KNOWLEDGE

1 Introduction to knowledge management

3Learning outcomes/Management issues 3

Links to other chapters 3

Opening vignette: Life in an interconnected world 4

Knowledge management: an integrated approach 6

Part 1: The nature of knowledge 6

Part 2: Leveraging knowledge 7

Part 3: Creating knowledge 7

Part 4: Knowledge artefacts 7

Part 5: Mobilising knowledge 8

Introduction 8

The knowledge economy 9

What is knowledge management? 10

Is knowledge management a fad? 14

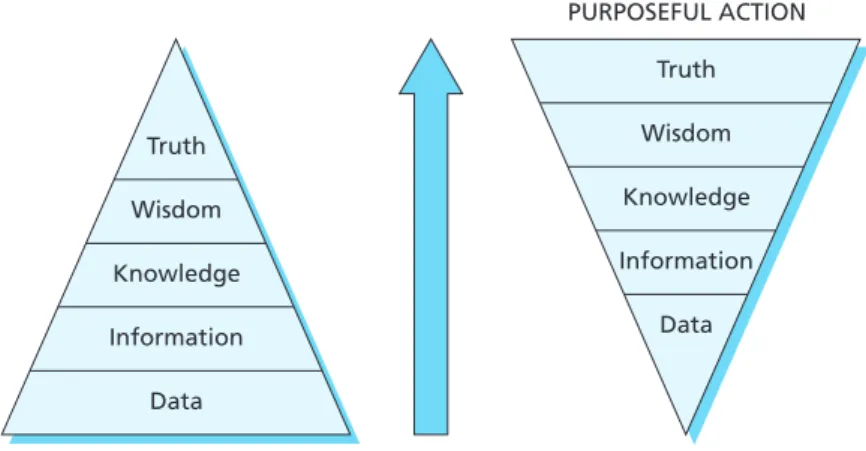

What are the differences between data, information, knowledge and wisdom? 16

Data 16

Information 17

Knowledge 18

Wisdom 19

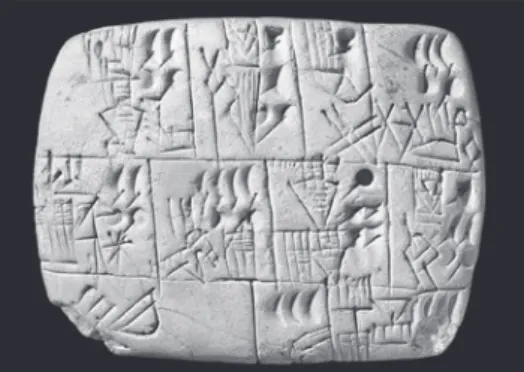

Early history of knowledge management: oral tradition to cuneiform 20

Knowledge management in ancient Greece and Rome 22

Management of knowledge in monastic and cathedral libraries 24

Paradigm shift from print to a digital age 26

Case study: Ernst & Young (US) 28

Summary 30

Questions for further thought 30

Further reading 31

References 31

2 The nature of knowing

33Learning outcomes/Management issues 33

Links to other chapters 33

Opening vignette: Business must learn from the new tribe 34

Introduction 35

What is knowledge? Philosophers from Plato to Wittgenstein 37

Contents

ix

Plato 37

Aristotle 37

Descartes 38

Locke 38

Hume 39

Kant 39

Hegel 39

Pragmatists 40

Phenomenology and existentialism 40

Wittgenstein 41

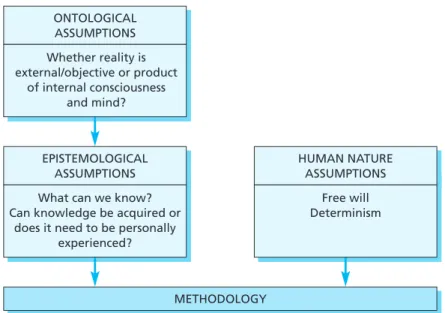

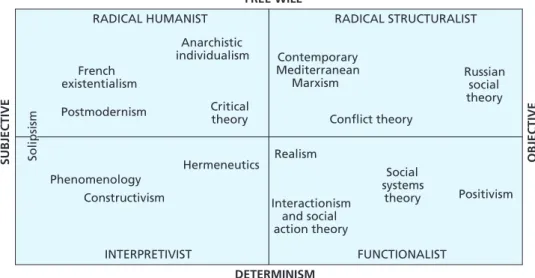

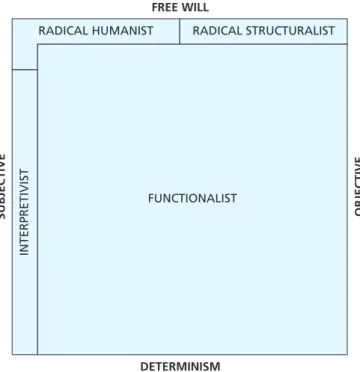

Contemporary philosophers: Ryle, Polanyi and Macmurray 42 Burrell and Morgan’s framework on philosophical paradigms 44 Competing philosophical positions in knowledge management: positivism,

constructivism, postmodernism and critical realism 46

The taxonomic perspective of knowledge 49

The process-based perspective of knowing 51

The practice-based perspective of knowledge and knowing 52

Case study: World Bank (US) 54

Summary 56

Questions for further thought 57

Further reading 57

References 58

Part 2 LEVERAGING KNOWLEDGE

3 Intellectual capital

63Learning outcomes/Management issues 63

Links to other chapters 63

Opening vignette: A little knowledge is deadly dangerous 64

Introduction 65

What is intellectual capital? 66

History of intellectual capital 68

Problems of measuring organisational performance 68

Frameworks of intellectual capital 71

Human and social capital 75

Organisational capital 76

Intellectual property and smart patents 76

Financial reporting of intellectual capital 79

Intellectual capital as a narrative 79

Knowledge auditing in practice 81

Case study: Infosys (India) 83

Summary 85

Questions for further thought 85

Further reading 86

References 86

4 Strategic management perspectives

89Learning outcomes/Management issues 89

Contents xi

Links to other chapters 89

Opening vignette: A hunger for knowledge is China’s real secret weapon 90

Introduction 91

Strategic management: schools of thought 92

Industrial organisation tradition 93

Excellence and turnaround 95

Institutionalist perspective 96

Resource-based view of the firm 100

Information systems strategy 101

Developing a knowledge management strategy 103

Innovation and personalisation strategies 108

Case study: Unilever (UK/Netherlands) 111

Summary 113

Questions for further thought 114

Further reading 114

References 115

Part 3 CREATING KNOWLEDGE

5 Organisational learning

121Learning outcomes/Management issues 121

Links to other chapters 121

Opening vignette: Recruits fired up by virtual rivalry 122

Introduction 124

Individual learning 124

Team learning 127

Drivers of organisational learning: success or failure? 128

Single-loop and double-loop learning 130

Sensemaking 131

Organisational learning frameworks 133

Knowledge acquisition 136

Information distribution 137

Information interpretation 138

Organisational memory 139

Unlearning 140

Organisational routines 141

Dynamic capabilities 144

Absorptive capacity 147

Politics and organisational learning 148

Critique of organisational learning 150

Case study: Toyota (Japan) 151

Summary 153

Questions for further thought 153

Further reading 154

References 154

6 The learning organisation

158Learning outcomes/Management issues 158

Links to other chapters 158

Opening vignette: Teaching materials: From pen to paper to wikis and video 159

Introduction 160

US contribution: the fifth discipline 161

UK contribution: the learning company 163

Japanese contribution: the knowledge-creating company 166

The competitive learning organisation 169

Power, politics and the learning organisation 173

Empirical research and the learning organisation 174

The learning organisation and knowledge management 176

Case study: Honda (Japan) 177

Summary 179

Questions for further thought 180

Further reading 180

References 180

Part 4 KNOWLEDGE ARTEFACTS

7 Knowledge management tools: component technologies

185Learning outcomes/Management issues 185

Links to other chapters 185

Opening vignette: Business starts to take Web 2.0 tools seriously 186

Introduction 188

Organising knowledge tools 189

Ontology and taxonomy 189

Capturing knowledge tools 194

Cognitive mapping tools 194

Information-retrieval tools 196

Search engines 200

Agent technology 201

Personalisation 202

Evaluating knowledge 203

Case-based reasoning (CBR) 203

Online analytical processing (OLAP) 203

Knowledge discovery in databases – data mining 204

Machine-based learning 206

Sharing knowledge 206

Internet, intranets and extranets 206

Security of intranets 209

Text-based conferencing 209

Web 2.0 platform 210

Conversational media: Blogs 212

Syndication and RSS feeds 213

Mashups 213

Wikis 214

Online social networks 215

3-D virtual worlds 216

Groupware tools 217

Videoconferencing 218

Contents xiii

Skills directories: expertise yellow pages 218

E-learning 218

Storing and presenting knowledge 219

Data warehouses 219

Visualisation 220

Case study: Royal Dutch Shell (Netherlands/UK) 222

Summary 224

Questions for further thought 224

Further reading 225

References 225

8 Knowledge management systems

228Learning outcomes/Management issues 228

Links to other chapters 228

Opening vignette: Decision-making software in the fast lane 229

Introduction 230

Systems thinking 232

Drivers of KM systems: quality management processes 235

Deming and Juran 235

Total quality management (TQM) 236

Business process re-engineering (BPR) 237

Lean production 238

Document management systems 239

Decision support systems 241

Group support systems 243

Executive information systems 245

Workflow management systems 247

Customer relationship management systems 250

Economics of KM systems 252

Case study: Tata Consultancy Services (India) 253

Summary 255

Questions for further thought 256

Further reading 256

References 257

Part 5 MOBILISING KNOWLEDGE

9 Enabling knowledge contexts and networks

261Learning outcomes/Management issues 261

Links to other chapters 261

Opening vignette: Building bridges for success 262

Introduction 265

Understanding organisational culture and climate 265

Norms, artefacts and symbols 267

Values, beliefs, attitudes and assumptions 270

Typologies of organisational culture 272

Measuring organisational culture 274

Description of the twelve OCI styles 275

Creating knowledge-sharing cultures 278 Cultural stickiness: developing communities of practice 282

Knowledge across organisational boundaries 286

Case study: Fluor (United States) 289

Summary 291

Questions for further thought 292

Further reading 292

References 293

10 Implementing knowledge management

295Learning outcomes/Management issues 295

Links to other chapters 295

Opening vignette: Box clever and keep your star performers happy 296

Introduction 297

The nature of change 298

Personal response to change 299

Leadership and change 301

Change management strategies 302

Gaining commitment for change 304

Employee involvement 306

Training and development 308

Reward and recognition 312

Cultural change management 314

Politics of change 316

Case study: Woods Bagot (Australia) 316

Summary 318

Questions for further thought 319

Further reading 319

References 320

Epilogue KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

Epilogue

325Introduction 325

Wrestling with knowledge: some reflections 326

Knowledge management – is there an optimal approach? 328 Organisational gymnastics: balancing learning with routines and dynamic

capabilities 329

Knowledge management between nations 330

Institutionalist perspective and the knowledge-based view of the firm 332

Communities of practice 333

Personal knowledge management 334

Knowledge management between nations 335

Concluding remarks 337

Further reading 338

References 338

Glossary 340

Index 345

The stimulus for this book came from the fact that I wanted a single knowledge man- agement text for my postgraduate and doctoral students. During my deliberations, I was surprised that I could not find a single book that covered the breadth and range of material in knowledge management. Some of the scholarly offerings came from a human resource perspective, some from practitioner orientations, while others came from strong information systems directions. A cursory look at these texts showed that there was little crossover between these three dominant dimensions. Scholars from one perspective were rarely cited in the other and vice versa. The situation was as if each perspective of knowledge management was engrossed in its little world without having the language or foresight to engage in the other perspective.

Such a situation is not totally surprising given that knowledge management as a dis- cipline is little over ten years old. There is currently a tremendous drive and popularity in knowledge management as practitioners and academics have accepted that we are collectively moving into a knowledge economy. To survive as individuals or companies in this knowledge economy, we need tools and shared understanding of potential chal- lenges and ways of dealing with them in knowledge-based organisations.

This book is intended for students and practitioners of knowledge management and recognises the relevance of the book for students from a multitude of different industrial sectors. The problems of managing knowledge and the everyday needs of knowledge workers are common across many sectors. This book should appeal to stu- dents and practitioners looking for a comprehensive coverage of theoretical debates and best practice in knowledge management. The book is likely to be challenging as it demands some philosophical introspection on the nature of knowledge given the argu- ment that we cannot begin to manage knowledge until we know what knowledge is.

Certain management or information systems aspects may also appear daunting to the uninitiated, particularly if this is not your background.

I suggest that you work through the uncomfortable feelings as I believe that the strength of this emerging discipline lies in an integrated approach to knowledge man- agement. There are rich rewards as we move into a new paradigm of work. The material in this book is intended to provide you with some pertinent and practical frameworks as well as offer a source of stimuli to think and find out more in depth where needed.

Even though there are questions within the text related directly to material found in each chapter, the ‘Questions for further thought’ were designed to help you think ‘out- side the box’ using material from your experience and wider reading.

Facebook, Twitter and Second Life didn’t exist five years ago when this book was first published. There have been major advances in Web 2.0 technologies that facilitate interactive knowledge sharing, interoperability and collaboration. In this second edi- tion, I have brought these latest technologies up to date. I was never happy with the structure of the first edition. This is inevitable when you’re trying to break new ground in an emerging disciple. For this reason, I have revised the structure of the second edi- tion, which provides much greater coherence.

Preface

xv

One of the shortcomings of the first edition was the lack of real-life case stud- ies for class discussion. I found myself using different sources with limited success. I have rectified this situation by writing ten new case studies for class discussion. For my source material, I have only used companies that have won the MAKE (Most Admired Knowledge Enterprises) award. I felt that these international organisations would pro- vide exemplars and important sources of learning. I have stitched together the case studies from a variety of publicly available sources and followed the traditional case study format of starting with a problem that needs to be resolved and set within the context of limited real-life information. I have taken some poetic licence in order to reinforce the intended learning.

Ashok Jashapara November 2010

Dr Ashok Jashapara is an internationally recognised expert in the field of knowledge management. He has pub- lished widely in leading books and journals and has won a number of awards for his writing. He has secured a number of research awards from notable national and international funding bodies such as the ESRC, NIHR, EU and the United Nations. He has acted as External Examiner at the University of Sheffield and led the information studies discipline in teaching and learning as Associate Director for the Higher Education Academy. He is a Founder Member of the Knowledge Management Research Group at Loughborough University and the iCOM Research Group at Royal Holloway (University of London).

About the author

xvii

My special thanks go to my partner Karin. I would like to thank her for her tolerance of my many absences from family life, as well as practical and moral encouragement throughout the writing period. She was terrific! My two daughters, Nicole and Anna-Tina, have been an inspiration to me and I have valued their hugs and mischief when I have become overly involved with writing this book. My parents, Ramnik and Nilu, have also provided much-needed warmth and reassurance over the past year.

A large number of people have helped me with the preparation of this book, not least Gabrielle James and Emma Violet at Pearson Education, whose assistance and advice guided my percep- tions of a good textbook. I would like to thank colleagues in the School of Management at Royal Holloway (University of London) for their kind words and feedback on chapters and early drafts of the book, in particular Professor Duska Rosenberg, Dr Bill Ryan, Dr Leonardo Rinaldi and Dr Gloria Agyemang. A special acknowledgement goes to members of the Knowledge Management Research Group at Loughborough University who read draft chapters and gave me their valuable comments that helped improve the final version.

I would like to thank Professor Ron Summers, Dr Mark Hepworth, Dr Tom Jackson and Dr Ann O’Brien in this regard.

I owe a debt of gratitude to my friends at the

‘Swan, Hope and Windsor’ for their great forbear-

ance at my ramblings when I have needed to talk to someone outside the confines of knowl- edge management. John Mack and Tony Zajciw at the ‘Swan’ have provided perfect diversions into conversations around the arts. Similarly, Glen Thumwood, Graham Farenden, Roberto Sarah Sanchez, Terry Prudham, Tony Vaghela, Celis and Tommy have provided much-needed humour, wit and hilarity to balance the serious- ness of writing a book. I am similarly grateful to my biking friends Al and Blossom at the ‘Coffin Scratchers’ for the long bike rides and music fes- tival diversions during the writing of this book. I cannot forget Roger Faulks and Manu Frosch at Swithland Woods for their friendship and tacit encouragement in this process.

Finally, I would like to thank the reviewers of this second edition and draft chapters. They steered the book into new and uncharted waters and, while I do not claim to have incorporated all of their comments, they certainly caused some heart-searching reflection.

During the course of writing the first edition of this book, my close friend, Spud Bakhle, died.

I would like to dedicate this book to a celebration of his life and acknowledge our numerous conver- sations and ideas that have found their way into this book. Spud Bakhle was a Hegelian and Kantian scholar among other things and ideas around a dialectic are directly attributable to him.

xviii

We are grateful to the following for permission to reproduce copyright material:

Figures

Figure 2.3, 2.4, 11.1 adapted from Sociological Paradigms and Organizational Analysis: Elements of the Sociology of Corporate Life, Ashgate (Burrell, G. and Morgan, M. 1985) copyright © Ashgate Publishing; Figure 2.5 adapted from ‘The paradigm is dead, the para- digm is dead... long live the paradigm: the legacy of Burrell and Morgan’, Omega – The International Journal of Management Science, Vol 28 (1), pp.249–268 (Goles, T. and Hirschheim, R. 2000), Copyright © 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved; Figure 2.6 adapted from Method in Social Science: A Realist Approach, Routledge (Sayer, A. 1992) copyright © Cengage Learning EMEA Ltd; Figure 2.8 from ‘Moving beyond tacit and explicit distinctions: a realist theory of organizational knowledge’, Journal of Information Science, Vol 33 (6), pp.752–766 (Jashapara, A.), Sage Publications. Copyright © 2007, Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals; Figure 3.1 adapted from Intellectual Capital: Navigating in the New Business Landscape, Macmillan (Roos, J., Roos, G., Edvinsson, L. and Dragonetti, N.C. 1997) p.15, figure 1.2, Reproduced by permission of Palgrave Macmillan;

Figure 3.3 from ‘The Balanced Scorecard – Measures that Drive Performance’, Harvard Business Review (R.S. Kaplan and D.P. Norton, Jan–Feb 1992), copyright © Harvard Business School Publishing; Figure 3.4a from ‘Dow’s journey to a knowledge value management culture’, European Management Journal, Vol 14 (4), pp.365–373 (Petrash, G. 1996), Copyright © 1996 Published by Elsevier Science Ltd; Figure 3.4b from Intellectual Capital:

Realizing Your Company’s True Value by Finding Its Hidden Brainpower, Judy Piatkus (Publishers) Ltd (Edvinsson, L. and Malone, M.S. 1997) copyright © 1997 by Leif Edvinsson and Michael S. Malone. Reprinted by per- mission of HarperCollins Publishers and Little, Brown Publishers Ltd; Figure 3.4c from Strategic Management of Professional Service Firms, Handelshojskolens Forlag (Lowendahl, B. 1997) reproduced with permission;

Figure 3.4d from The Danish Confederation of Trade Unions, 1999, reproduced with permission of LO, Landsorganisationen Islands; Figure 3.4e from Profiting from Intellectual Capital: Extracting Value from Innovation, Wiley (Sullivan, P.H. 1998) Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Figure 3.4f from Intellectual Capital, Thomson Publishers (Brooking, A. 1996) copyright © Cengage Learning EMEA Ltd; Figure 3.6 adapted from ‘Developing and managing knowl- edge through intellectual capital statements’, Journal

of Intellectual Capital, Vol 3 (1), pp.10–29 (Mouritsen, J., Bukh, P.N., Larsen, H.T. and Johansen, M.R. 2002), Copyright © 2002, MCB UP Ltd; Figure 3.7 adapted from ‘Knowledge management: auditing and report- ing intellectual capital’, Journal of General Management, Vol 26 (3), pp.26–40 (Truch, E. 2001), copyright © The Braybrooke Press Ltd; Figure 4.1 adapted from

‘Of strategies, deliberate and emergent’, Strategic Management Journal, Vol 6 (3), pp.257–272 (Mintzberg, H. and Waters, J.A. 1985), Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Figure 4.3 adapted from ‘The effec- tive organisation: forces and forms’, Sloan Management Review, Winter, pp.54–67 (Mintzberg, H. 1991), © 1991 from MIT Sloan Management Review/Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Distributed by Tribune Media Services; Figure 5.2 adapted from The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organisation, Doubleday Currency (Senge, P.M. 1990) copyright (c) 1990, 2006 by Peter M. Senge. Used by permission of Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc.; Figures 5.5, 5.6, 5.7 adapted from “Organisational learning: the contributing processes and the litera- tures”, Organization Science, Vol 2, pp.88–115 (Huber, G.P. 1991), reproduced with permission. Copyright

© 1991, the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS), 7240 Parkway Drive, Suite 300, Hanover, Maryland 21076, USA; Figure 6.2 from The Learning Organization, Gower (Garratt, B. 1987) copyright © Professor Bob Garratt; Figure 6.3 from The Learning Company: A Strategy for Sustainable Development, McGraw-Hill (Pedler, M., Burgoyne, J. and Boydell, T. 1991) Reproduced with the kind permission of The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved; Figure 6.4 from The Knowledge Creating Company, Harvard Business Review, 69 (Nov–Dec), pp. 96–104 (Nonaka, I.

1991), copyright © Harvard Business School Publishing;

Figure 6.5 from ‘Cognition, culture and competition:

an empirical test of the learning organization’, The Learning Organization: An International Journal, Vol 10 (1), pp.31–50 (Jashapara, A. 2003), Copyright © 2003, MCB UP Ltd; Figure 6.6 from ‘A Typology of the Idea of Learning Organization’, Management Learning, 33 (2), pp.213–230 (Ortenblad, A. 2002), Copyright © 2002, SAGE Publications; Figure 7.13 adapted from John Risch at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, www.cybergeography.org/atlas/info_spaces.html, reproduced courtesy of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory; Figure 9.3 from ‘Handy’s typology of culture’

from Understanding Organisations, Fourth edition 1993, Penguin Books 1976 (Handy, C.B.) copyright (c) Charles Handy, 1976, 1981, 1985, 1993, 1999. Reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd; Figure 9.4 from

Publisher’s acknowledgements

xix

Corporate Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life, Penguin (Deal, T.E. and Kennedy, A.A. 1982) copyright © T. Deal and A. Kennedy. Reprinted by per- mission of The Peters Fraser and Dunlop Group Limited on behalf of T. Deal and A. Kennedy; Figure 9.6 from Organizational Culture Inventory, Human Synergistics (Cooke, R.A. and Lafferty, J.C. 1987) copyright © Human Synergistics International; Figure 9.7 from ‘The concept of ”Ba”: building a foundation for knowledge creation’, California Management Review, Vol 40(3), pp.40–54 (Nonaka, I. and Konno, N. 1998), copyright (c) 1998 by The Regents of the University of California; Figure 9.11 from ‘Transferring, translating and transforming: An integrative framework for managing knowledge across boundaries’, Organization Science, Vol 15, p.558 (Carlile, P.R. 2004), Reproduced with permission of INFORMS and Paul R. Carlile. Copyright © 2004, the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS), 7240 Parkway Drive, Suite 300, Hanover, Maryland 21076, USA; Figure 10.3 from The Theory and Practice of Change Management, Palgrave (Hayes, J. 2002) p.215, figure 12.2, Reproduced by permission of Palgrave Macmillan; Figure 10.8 from Employee Development Practice, Pitman Publishing (Stewart, J. 1999) copyright

© Pearson Education Ltd; Figure 11.7 from Know Your Value? Value What You Know, Prentice Hall (Cope, M.

2000) copyright © Pearson Education Ltd.

Screenshots

Screenshot 7.6 from Decision Explorer ®. Reproduced with the kind permission of Banxia Software Ltd.

Banxia and Decision Explorer are registered trademarks.

Tables

Table 5.1 from An organisational learning framework:

from intuition to institution, Academy of Management Review, 24 (3), pp. 522–37 (Crossan, M.M., Lane, H. and White, R. 1999); Table 5.2 adapted from ‘Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities’, Organization Science, Vol 13 (issue 3), pp.339–51 (Zollo, M. and Winter, S.G. 2002), Adapted with permission.

Copyright © 2002, the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS), 7240 Parkway Drive, Suite 300, Hanover, Maryland 21076, USA; Table 6.2 from The learning organisation simpli- fied, Training and Development, July, pp. 30–33 (Honey, P.

1991), copyright © Peter Honey, Education Development International; Table 6.3 from ‘The Competitive Learning Organization: A Quest for the Holy Grail’, Management Decision, Vol 31 (8), pp.52–62 (Jashapara, A. 1993), Copyright © 1993, MCB UP Ltd; Table 8.1 from ‘Review:

Knowledge Management and Knowledge Management Systems’, MIS Quarterly, 25 (1), pp.107–136 (Alavi, M.

and Leidner, D.E. 2001), Copyright © 1995, Regents of the University of Minnesota. Reprinted by permis- sion; Table 8.2 from ‘Systems thinking on knowledge and its management: systems methodology for knowl- edge management’, Journal of Knowledge Management,

Vol 6 (1), pp.7–17 (Gao, F., Li, M. and Nakamori, Y.

2002), Copyright © 2002, MCB UP Ltd; Table 8.5 from Working with Groupware: Understanding and Evaluating Collaboration Technology, Springer-Verlag (Andriessen, J.H.E. 2003) with kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media; Table 9.1 adapted from

‘Corporations, culture and commitment: motivation and social control in organizations’, California Management Review, Vol 31(4), pp.9–25 (O’Reilly, C.A. 1989), copy- right (c) 1989 by The Regents of the University of California; Table 9.2 from ‘Communities of practice:

the organizational frontier’, Harvard Business Review, pp.139–45 (Wenger, E.C. and Snyder, W.M., Jan–Feb 2000), copyright © Harvard Business School Publishing.

Photographs

Figure 1.5 © The Trustees of The British Museum; Figure 1.6 © The British Library Board (Lansdowne 1179 f34v);

Figure 1.7 © The British Library Board (C.9.d.3).

Text

Article on pages 262–264 from ‘Building bridges for success’, The Financial Times, 29/06/2007 (Grattan, L.), copyright (c) Lynda Grattan; General Displayed Text on pages 275–278 from Organizational Culture Inventory, Human Synergistics (Cooke, R.A. and Lafferty, J.C.

1987) copyright © Human Synergistics International.

The Financial Times

Article on page 5 from ‘Life in an interconnected world’, The Financial Times, 03/11/2009 (Waters, R.), copyright

© The Financial Times Ltd; Article on page 35 from

‘Business must learn from the new tribe’, The Financial Times, 29/05/2009 (Twentyman, J.), copyright © The Financial Times Ltd; Extract on pages 64–65 from ‘A little knowledge is deadly dangerous’, The Financial Times, 12/01/2010 (Stern, S.), copyright © The Financial Times Ltd; Article on page 91 from ‘A hunger for knowl- edge is China’s real secret weapon’, The Financial Times, 05/10/2005, p.12 (London, S.), copyright © The Financial Times Ltd; Article on pages 122–123 from ‘Recruits fired up by virtual rivalry’, The Financial Times, 04/05/2009 (Tieman, R.), copyright © The Financial Times Ltd;

Article on pages 159–160 from ‘Teaching materials: From pen and paper to wikis and video’, The Financial Times, 11/05/2009 (Jacobs, M.), copyright © The Financial Times Ltd; Article on pages 186–187 from ‘Business starts to take Web 2.0 tools seriously’, The Financial Times, 28/01/2009 (Twentyman, J.), copyright © The Financial Times Ltd;

Article on pages 229–230 from ‘Decision-making software in the fast lane’, The Financial Times, 28/02/2007 (Cane, A.), copyright © The Financial Times Ltd; Article on pages 296–297 from ‘Box clever and keep your star performers happy’, The Financial Times, 26/05/2009, p.14 (Stern, S.), copyright © The Financial Times Ltd.

In some instances we have been unable to trace the owners of copyright material, and we would appreciate any information that would enable us to do so.

Part 1

THE NATURE OF KNOWLEDGE

NATURE OF KNOWLEDGE

Data, information and knowledge

LEVERAGING KNOWLEDGE Intellectual capital Strategic management

perspectives Knowledge management

strategy

CREATING KNOWLEDGE Organisational learning

Learning organisations KNOWLEDGE

ARTEFACTS

Knowledge management tools Knowledge management systems

MOBILISING KNOWLEDGE Enabling contexts Knowledge networks Change management

History of managing knowledge Philosophical perspectives on knowledge

Chapter 1

Introduction to knowledge management

Learning outcomes

After completing this chapter, the reader should be able to:

●

● distinguish between different perspectives in the knowledge management (KM) literature;

●

● explain the diversity of disciplines and content that make up the field of knowledge management;

●

● describe the differences between the terms data, information and knowledge;

●

● assess the differences in the management of knowledge from ancient to modern times.

Links to other chapters

Chapter 2 examines the history of philosophical thought on the notion of knowledge which links directly to the history of managing knowledge from the oral traditions to the storage of knowledge in libraries.

Management issues

An introduction to the discipline of knowledge management implies these questions for managers:

●

● What is knowledge management?

●

● How can knowledge improve actions in an organisation?

●

● What is the difference between information management and knowledge management?

OPENING VIGNETTE

‘Tech companies are hoping that the latest inno- vations in the sphere of “collaboration software”

will revolutionise the way in which we work,’

writes Richard Waters.

The Digital Age has bred a new class of infor- mation slaves. They process endless streams of e-mail or waste time hunting for information on their hard disks and corporate intranets. Edited and re-edited versions of the same document bounce back and forth on long e-mail threads among co-workers, challenging them to keep up.

For the tortuous and time-consuming nature of this work, you can blame some of the world’s big- gest technology companies. Much of the ‘collabo- ration software’ that most workers use to commu- nicate and work together – in particular the e-mail systems that dominate white-collar working life – has barely changed in a decade, even as the tide of messages and documents has risen.

‘It’s almost been criminal, the lack of innova- tion on the e-mail client,’ says Matt Cain, an analyst at Gartner, the technology research firm.

Even in areas where technology has advanced, many workers are still in the Dark Ages – either because their companies have yet to give them the latest tools, or because they don’t have the time or inclination to try them out.

‘It’s a constant challenge for us to make peo- ple engage with new technologies,’ says Stephen Elop, president of Microsoft’s business division, which makes the widely used Office applications.

The sheer number of applications that the average worker has to juggle hasn’t helped. These now range from corporate document-sharing sites and web conferencing to Facebook and Twitter, which are starting to encroach from the consumer world.

‘If you count up all the applications people are being asked to use, it’s probably a dozen,’ says Ted Schadler, an analyst at Forrester Research.

The result, he says, is overload and frustration. In a survey last month of how 2,000 office workers use their PCs, Forrester concluded that the take- up of collaboration tools has ‘stalled out’, leaving e-mail as the all-purpose default option. Change, however, is finally in the air. The market for collaboration software, dominated for years by

Microsoft and IBM, is now under attack from all sides as other technology companies hunt for ways to make so-called ‘knowledge workers’

more productive.

Cisco Systems showed its hand last month with the announcement of a $3bn (e2bn,

£1.8bn) agreement to buy Tandberg, a Norwegian video-conferencing company, to add to widening portfolio tools. Google launched a limited test version of its own all-purpose online tool, known as Wave, in September.

Undaunted by the coming clash of giants such as these, several start-ups have also set their sights on the market. Typical of the breed is Xobni, whose technology rides on top of the widely used Microsoft Outlook e-mail software and aims to help users find and make use of information in their e-mail inboxes more effec- tively than Microsoft’s own tools can.

Most of these companies have their sights set on the same things: simplification and convergence.

One manifestation of this is the growing use of ‘dashboards’ – screens that bring a number of applications together in one view. They are usu- ally centred on the e-mail inbox, with parts of the screen given over to other applications.

Designs such as this are meant to help workers complete a task without having to close and open multiple windows on their PCs. They aggregate multiple sources of information and provide a limited amount of information integration.

‘For instance, when opening an e-mail from a customer, a user of Xobni’s dashboard might see information alongside it drawn automatically from the company’s internal customer relation- ship management system,’ says Jeff Bonforte, the company’s chief executive. ‘The bigger operators are also moving quickly in this direction, with most likely to announce similar products in the coming months,’ says Mr Schadler at Forrester.

Aggregating and integrating e-mail with other sources of information and applications is only part of the answer. Eventually, to solve e-mail overload, the inbox itself needs to become smarter.

‘It should be able to aggregate all the sources and recommend priorities,’ says Doug Heintzman, head of strategy for IBM’s collaboration software.

Life in an interconnected world FT

Chapter 1 / Introduction to knowledge management 5

Research labs at companies such as IBM and Microsoft have been working for some time on the algorithms to do this, but according to Mr Heintzman, a working system is still three to five years away.

A second approach to simplification and con- vergence focuses on ways for workers to collabo- rate on tasks without having to resort to endless group e-mails with multiple ‘cc’s’ and attachments.

Most new approaches revolve around software that keeps information in a central place and lets staff jointly access and work on it. Microsoft, for instance, has devised a way for people in differ- ent locations to ‘co-author’ a document simulta- neously, though their employers will need to buy the latest versions of its Office and server-based Sharepoint software for this to work.

Google is now trying to go one better. If peo- ple can communicate in the same place that they create and edit information, it calculates, then many of the complexities caused by current soft- ware would fall away.

The result is Google Wave, an online application built for both consumer and work use that merges multiple ways of working and communicating.

That makes it the Swiss Army Knife of software, and its early reception has been mixed, reflecting the difficulty of such an ambitious undertaking.

‘It’s the opposite of simple,’ says Mr Cain at Gartner, though he adds that it is ‘really innova- tive’. ‘There’s no doubt it will have an impact on the evolution of this market,’ he says. For the average information slave, meanwhile, none of this guarantees a quick or sure route to higher productivity and lower blood pressure. Though many of these new ways of interacting have already been tried out in the consumer world – ‘social’ software such as wikis, or co-authored documents were a staple of the Web 2.0 move- ment – it will be some time before they find their way into office life.

It takes time for experimental consumer serv- ices to evolve into the stable, secure applications that corporate IT departments feel comfortable with. Also, the slow upgrade cycle of corporate software feels glacial compared to the red-hot pace of innovation currently seen on the inter- net. The biggest challenge of all, though, comes from workers themselves.

‘Any collaboration tool that is not adopted widely will, by definition, fail, yet devising soft- ware that appeals to a broad group of users is

hard,’ says Mr Heintzman at IBM. ‘There are so many different work styles, people have so many different roles and come from different cultures,’

he explains.

They also come from different technological eras: a generation of workers wedded to e-mail is starting to encounter a generation that grew up on social networks and instant messaging. Keeping them all on the same page will not be easy.

Surf the Wave

It was classic Google ambition. Earlier this year, Lars Rasmussen, one of the company’s star devel- opers, stood in front of thousands at a company- sponsored conference and said that Google was about to reinvent e-mail.

Google Wave, now in a limited test, has been hailed as a radical departure in internet-based com- munication, though it has also been faulted for its complexity and poor design – criticisms that Mr Rasmussen and his fellow developers accept, though they say they will correct these glitches.

Like an expanded instant messaging system, Wave lets groups of users hold a text conversation while also creating, commenting on and jointly editing documents in the same window. In a head-turning gimmick, words can be seen by any- one connected to a ‘wave’ as they are being typed.

‘Making one tool with such broad utility is the way to go,’ Mr Rasmussen says. ‘You don‘t have to learn a new way of sharing something for every different collaboration task. Everything is just a wave.’ In spite of the simplicity which that implies, getting the most out of Wave will demand a lot from its users. ‘We weren’t try- ing to hit something that you could learn in an afternoon,’ he says. ‘We were trying to build a tool that will be with you for many hours each day. You can even imagine, in time, people will be teaching courses in Wave.’

Source: from Life in an interconnected world, The Financial Times, 03/11/2009 (Waters, R.), copyright © The Financial Times Ltd.

Questions

1 How can ‘information slaves’ overcome problems of ‘information overload’?

2 What are the problems of collaborative technologies for ‘knowledge workers’?

3 How can Google Wave improve collaboration and communication among ‘knowledge workers’?

Knowledge management: an integrated approach

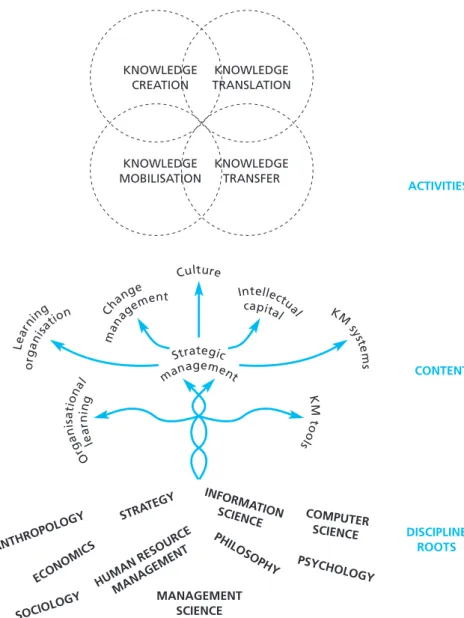

The aim of this book is to provide a comprehensive and integrated discourse on the various facets, emerging issues and perspectives on knowledge management. There are numerous accounts of knowledge management as a process and a continuous cycle and this representation has been used as a structure for this book, as shown in Figure 1.1.

The generic activities in the knowledge management cycle are subdivided into the five parts of this book: the nature of knowledge, leveraging knowledge, creating knowledge, knowledge artefacts and mobilising knowledge.

●

◗ Part 1: The nature of knowledge

Part 1 explores all the different aspects related to the notion of knowledge and knowl- edge management. An historical perspective on how knowledge was managed across the centuries from the bardic oral tradition to the current digital revolution is provided.

Philosophy is not often taught in our universities and its central role in understanding knowledge is examined. This will allow future students to move beyond the current structural, process and practice perspectives in the literature.

●

● Chapter 1: Introduction to knowledge management. This chapter provides an explora- tion of the emerging discipline and forwards an integrated model. The differences between data, information and knowledge are examined. An historical perspective on knowledge management illustrates the central function of libraries in knowledge creation, sharing and transfer.

NATURE OF KNOWLEDGE Data, information and knowledge

LEVERAGING KNOWLEDGE Intellectual capital Strategic management

perspectives Knowledge management

strategy

CREATING KNOWLEDGE Organisational learning

Learning organisations KNOWLEDGE

ARTEFACTS

Knowledge management tools Knowledge management systems

MOBILISING KNOWLEDGE Enabling contexts Knowledge networks Change management

History of managing knowledge Philosophical perspectives on knowledge

Figure 1.1 Web of knowledge management

Chapter 1 / Introduction to knowledge management 7

●

● Chapter 2: The nature of knowing. This is a thought-provoking chapter exploring issues of ontology and epistemology. What is the nature of knowledge and reality? What are the aspects of knowledge that we can know? The contributions of major philoso- phers in the knowledge debate are examined and the current notions of knowledge in the knowledge management literature are assessed.

●

◗ Part 2: Leveraging knowledge

Part 2 explores the fruits of knowledge management in the formation of intellectual capital within an organisation. Knowledge is considered as the critical factor for com- petitiveness and economic growth. The knowledge management strategies underlying innovation and growth are assessed.

●

● Chapter 3: Intellectual capital. This chapter examines some of the limitations of tradi- tional financial measures in performance measurement and the search for non-financial measures such as intellectual capital to supplement these conventional sources. Several models of intellectual capital are compared and generic notions of human capital, social capital, organisational capital and customer capital are presented.

●

● Chapter 4: Strategic management perspectives. This chapter contrasts the difference between three dominant strategy schools of thought: industrial organisation, excel- lence and turnaround, and the institutionalist perspective.

●

◗ Part 3: Creating knowledge

Part 3 examines the different organisational processes involved with knowledge crea- tion. At its heart are the various learning processes intrinsic to organisational survival and growth. The organisational learning literature has led to the conception of a ‘learning organisation’. The nature and debates surrounding a learning organisation are explored.

●

● Chapter 5: Organisational learning. This chapter outlines the nature of individual, team and organisational learning. An information processing perspective is adopted to examine the processes of knowledge acquisition, information distribution, information interpretation and organisational memory. The development of organi- sational routines and dynamic capabilities are discussed.

●

● Chapter 6: The learning organisation. This chapter contrasts the terms ‘organisational learning’ and the ‘learning organisation’ and articulates the diversity of US and UK models associated with the learning organisation. Empirical research in this field is assessed.

●

◗ Part 4: Knowledge artefacts

Part 4 examines knowledge artefacts, which occur as different forms of information and communication technologies to enable effective utilisation of knowledge. This part pro- vides an understanding of the different technologies used to mobilise knowledge, especially

the new Web 2.0 platform with applications such as Twitter, Facebook and Second Life. A number of these technologies have been integrated as knowledge management systems to allow organisations to manage the high load and complexity of knowledge.

●

● Chapter 7: Knowledge management tools: component technologies. This chapter pro- vides a grounding in the variety of knowledge management tools that can be used at different stages in the knowledge management cycle. These include ontology and taxonomy tools, information retrieval tools, personalisation tools, data mining tools, case-based reasoning tools, groupware tools, video-conferencing tools, e-learning tools and visualisation tools.

●

● Chapter 8: Knowledge management systems. This chapter elaborates on a variety of knowledge management systems including document management systems, deci- sion support systems, group support systems, executive information systems, workflow management systems and customer relationship management systems.

●

◗ Part 5: Mobilising knowledge

Part 5 examines the softer aspects of mobilising knowledge through people and tech- nology. Apart from conducive social environments, organisations are increasingly providing a mixture of physical and virtual spaces for their knowledge workers. The intention is to enable them to engage actively in discussion and dialogue in formal and informal settings. Innovation and new initiatives can often face hostility and difficul- ties. The various human resource interventions for the successful implementation of such initiatives are explored.

●

● Chapter 9: Enabling knowledge contexts and networks. This chapters contrasts the lit- erature on organisational climate and culture and explores the debates around knowledge-sharing cultures. Informal networks called ‘communities of practice’ are explained along with the role of storytelling and narratives within them.

●

● Chapter 10: Implementing knowledge management. This chapter provides the latest thinking on the effective implementation of knowledge management initiatives. It examines how high levels of commitment can be developed through leadership and a variety of human resource interventions. The role of politics in change manage- ment programmes is highlighted.

Introduction

Knowledge management has similar parallels with the rise of English as an academic discipline in the early twentieth century. In the 1920s it was unclear why anyone should study English and, by the 1930s, it was a question of whether students should study anything else at all. English was initially a poor man’s Classics and was taught in working men’s colleges and mechanic institutes. The subject was considered an upstart and rather amateurish affair compared with the traditional subjects such as Classics and Philology. Similarly, knowledge management in the twenty-first century has risen from

Chapter 1 / Introduction to knowledge management 9 practitioner and consultancy knowledge and has only recently become a subject for academic study. Today English is often associated with creative or imaginative writing.

However, in the eighteenth century, English covered all the valued writings in society including history, philosophy, essays, letters and poems (Eagleton 1999; Palmer 1965).

Similarly, today knowledge management can be confused with information systems by some commentators and human resource management by others. In reality, it has roots in a wide variety of disciplines such as philosophy, business management, anthropol- ogy, information science, psychology and computer science.

In fashioning knowledge management into a serious discipline, this chapter will explore the nature of knowledge management and propose a definition of this field from an interdisciplinary perspective. To provide a balanced appraisal of the literature, a critical understanding of reservations in this field will be forwarded. The terms ‘data’,

‘information’ and ‘knowledge’ can often be used synonymously in the literature and the distinction between these terms is explored.

Knowledge, and the way it is managed, has been with humankind since the beginning of time. This chapter shall proceed to explore the history of knowledge management, taking a broad perspective and including the vital role of libraries in the ancient and modern worlds. The development of oral knowledge from the oral tra- ditions to the first writing of cuneiform among Sumerians is discussed. A journey is conducted through the flourishing libraries in ancient Greek and Roman periods such as the Alexandria library and the Ulpian library. The influence of Christianity in the rise of monastic and cathedral libraries is explained together with the emergence of early universities. The paradigm leap in knowledge creation and dissemination that has occurred through the development of print, computers and telecommunications is fully explored.

The knowledge economy

Peter Drucker (1992, 1993) argued that the workplace was changing and there was an increasing distinction between the manual worker and the ‘knowledge worker’. To him, a manual worker used his hands to produce goods and services, whereas a knowledge worker used his head to create ideas, information and knowledge that could add value to the firm.

Subsequently, knowledge workers have been defined as professionals, associate pro- fessionals or managers with graduate level skills in critical thinking, communications and technology. In 2006 knowledge workers accounted for 42 per cent of all employ- ment in the UK (Brinkley, 2006). The concept of a knowledge economy has emerged to represent a ‘soft discontinuity’ from the past. It is not a new economy with new laws.

Instead it is an economy driven by knowledge intangibles rather than physical capital, natural resources or low-skilled labour. The OECD (1996) has recognised that knowledge and technology have become drivers of productivity and economic growth in modern economies. The new focus for economic performance is on knowledge, technology and learning. The role of governments and policy makers is shifting towards the greater development and maintenance of this knowledge base. It is not purely an increased

commitment to R&D but rather the mobilisation of knowledge to add value to goods and services. A number of definitions of the knowledge economy are provided below:

‘….one in which the generation and exploitation of knowledge has come to play the pre- dominant part in the creation of wealth. It is not simply about pushing back the frontiers of knowledge; it is also about the most effective use and exploitation of all types of knowledge in all manner of economic activity.’ (DTI 1998)

‘. . . economic success is increasingly based upon the effective utilisation of intangible assets such as knowledge, skills and innovative potential as the key resource for competitive advantage. The term ‘knowledge economy’ is used to describe this emerging economic struc- ture.’ (ESRC 2005 quoted in Brinkley 2006)

Unlike the use of scarce resources in previous economies, knowledge is not a resource that is depleted after its use. Instead, knowledge grows through transfer and exchange and an abundance of knowledge can be seen to exist on the internet. Firms are no longer restrained by the physical location of partners in a supply chain. Instead they can exist as virtual organisations and engage in economic activity within virtual marketplaces across the world. This can make it difficult for governments to regulate and control this economic activity through laws and taxes on a national basis.

Globalisation is closely related to the knowledge economy. Firms have added value through knowledge to new products in the West and have had them built and assem- bled in lower-wage economies such as China and India. However, the same low-waged economies are now investing heavily in knowledge through greater investment in R&D as a proportion of their GDP and increased numbers of home-grown graduates. They are developing their knowledge economies through greater share of highly educated labour and greater production and utilisation of information and communication technologies.

In 2007 a Booz Allan Hamilton (a consulting firm) report on global innovation showed that the top global innovating firms had established 80–90 per cent of their new corporate R&D sites and personnel in India and China (Teagarden et al., 2008). Is this an example of the use of ‘cheap smarts’ rather than use of more expensive home-grown talent?

What is knowledge management?

In the post-industrial or knowledge economy (Bell 1973; Drucker 1992), knowledge management has become an emerging discipline that has gained enormous popularity among academics, consultants and practitioners. It has been argued that it is no longer the traditional industrial technologies or craft skills that drive competitive performance but, instead, knowledge that has become the key asset to drive organisational survival and success.

To the uninitiated reader, the multitude of offerings on knowledge management in books, journals and magazines can appear rather daunting and confusing at first. The fact is that it is a relatively young discipline trying to find its way, while recognising that it has roots in a number of other, very different disciplines. Some literature on knowl- edge management is heavily information systems oriented, giving the impression that

Chapter 1 / Introduction to knowledge management 11 it is little more than information management. Other literature looks more at the peo- ple’s dimension of knowledge creation and sharing, making the subject more akin to human-resource management. These are the two most common dimensions and there is often little crossover between them. Each world fails to comprehend the other, as the language and assumptions of each discipline vary significantly. However, it is precisely these interdisciplinary linkages that provide the most rewarding advances in this field.

Given the interdisciplinary nature of this emerging field, conventional academic demarcations in traditional subject areas do not help. For example, it is relatively rare for computer or information science graduates to gain sufficient grounding in human resource management and vice versa with traditional business management students.

This impasse is often based on fear on both sides about the nature and relative merits of their respective skills and expertise. Beyond these two dominant dimensions, there are some additional perspectives within the KM literature, ranging from strategy to cultural change management. It is not surprising that there is little coherence between these offer- ings, as many authors orientate the subject area to their singular discipline perspective.

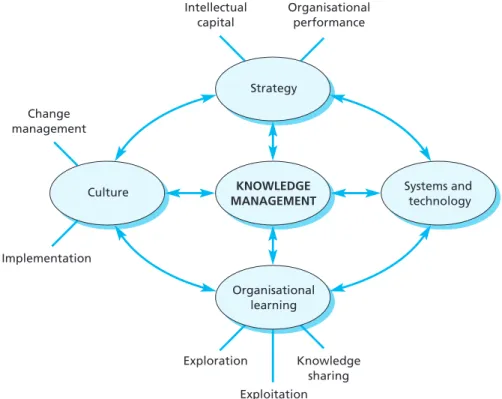

The strength and challenge of knowledge management as an emerging discipline comes from its interdisciplinary approach, as shown in Figure 1.2. For example, if knowledge management was purely information systems, current tools and business processes would suffice. However, the reality is that different information systems approaches such as data processing, management information systems and strategic information systems have been found wanting. There are numerous examples of major investments made in this area, particularly in the financial services sector, that have yielded little or no benefit to host organisations. Instead, the real synergies in knowl- edge management are more likely to occur from boundary-spanning individuals who can see beyond the narrow margins of their own disciplines and recognise the value of dialogue and debate with other disciplines.

Given the multidisciplinary nature of knowledge management, it is not surprising that the variety of current definitions comes from a number of different perspectives, as shown in Table 1.1. Some come from an information systems perspective (Mertins et al. 2000), while others suggest a human-resource perspective (Skyrme 1999; Swan et al. 1999a). A few definitions have begun to adopt a more strategic management per- spective, recognising the importance of knowledge management practices for gaining competitive advantage (Newell et al. 2009; uit Beijerse 2000). However, none of these definitions expands on the alliances with particular strategic schools of thought, and the basic assumptions of the nature of competitive environments (such as highly tur- bulent) or strategic positioning (such as continuous innovation) need to be questioned

Critical thinking and reflection

What does knowledge mean to you? If you were asked to detail your specialist knowledge, how would you describe your knowledge? Have you ever thought of the market value of your knowledge and what this may be? Given that there is a competitive market for knowledge and skills, how do you ensure that your knowledge is state-of-the-art and kept up to date?

(Newell et al. 2009). External environments may shift from turbulent to more stable environments over time and competitive environments may favour efficiency rather than innovation in a given period. The basic fact is that we live in uncertain times and any assumptions about competitive environments and approaches to organisational alignment and adaptability need to be considered carefully.

DISCIPLINE ROOTS INFORMA

SCIENCETION

ACTIVITIES

CONTENT

COMPUTER SCIENCE PHILO

SOPH

Y PSYCHOLOGY MANAGEMENT

SCIENCE STRATEGY

HUMAN RESO URCE MANAG

EMENT ANTHROPOLOGY

ECONOMICS SOCIOLOGY

Strategic management

Intellcapitealctual KM sys

te ms

KtoM s ol Chan

ge

management

Culture

Lea rning

organisa tion

rg O an

isa

tio nal

lear

ning

KNOWLEDGE CREATION

KNOWLEDGE TRANSLATION

KNOWLEDGE MOBILISATION

KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER

Figure 1.2 Tree of knowledge management – disciplines, content and activity

Chapter 1 / Introduction to knowledge management 13

Table 1.1 Representative sample o