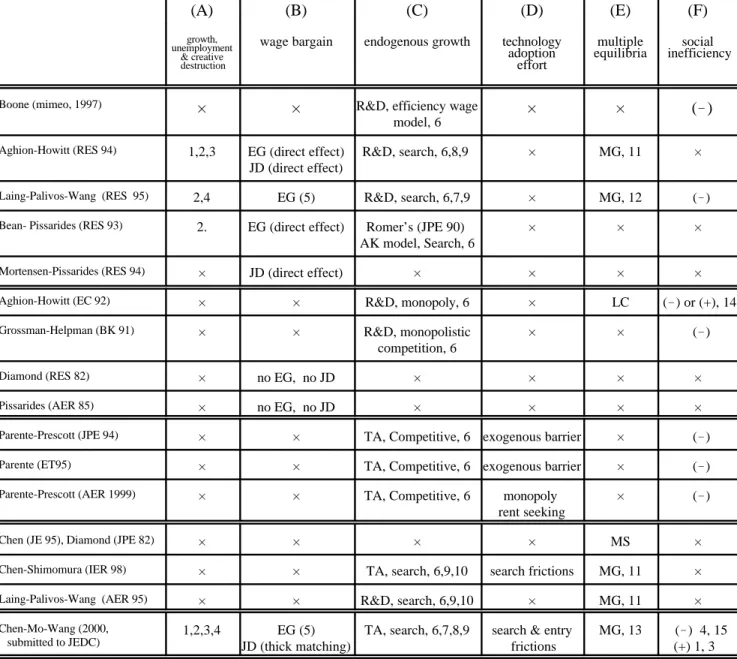

Second, unlike previous work on endogenous growth, both global and local multiple equilibria can emerge in our model as a result of the interactions between endogenous matching and. In our model, as a result of the dynamic interaction between endogenous matching and endogenous technology adoption, a small autonomous technological improvement may be enough to create a large real effect. Finally, in common with most R&D studies, our paper finds that the decentralized solution is generally socially inefficient (see Aghion and Howitt, 1992, and Grossman and Helpman, 1991).

One for oneV˜ matching implies the equality of the mass of corresponding workers (employment) and that of corresponding machines (filled vacancies), denoted E. Equation (2a) states that the flow-adjusted value of a worker consists of three components: ( i ) the wage, (ii) the incremental value by changing from matched to unpaired states, and, (iii) the incremental value by remaining in the matched state due to the continuous growth of technological knowledge. Under Condition TVC this can be done by dividing each of the continuously growing variables by H(t).

For example, a higher qo could be a consequence of the establishment of an employment center or better news and media for the public. 2 In fact, this equality rule is obtained from maximizing the joint objective function (˜JE&J˜U)1/2(A˜E&A˜U)1/2. In particular, by the symmetric Nash bargaining rule (which holds for all t), the evolution of the value of matching surplus against each machine, A/AE&AU, and the evolution of J are linearly dependent.

Furthermore, (4b) implies that the evolution of the unemployed and employed population measures, N and E, are also linearly dependent.

Exogenous Growth Equilibrium with Exogenous Technology Adoption

This implies that the matched value of machines depends positively on the power output, V - W, as well as on the reservation value (or unmatched value), AU. An increase in the job destruction rate (*) reduces both the matched and unmatched asset value of employees by increasing future discounts - a higher job destruction rate gives rise to a greater likelihood of separation in the future, thus increasing the subjective job destruction rate. discount. On the contrary, an increase in the rate of technological knowledge growth increases future values and can thus be considered a negative discount factor.

Of course, there is a positive direct wage effect that can be shown to dominate the waiting effect, so a higher rate of exogenous growth has an unequivocal positive effect on adjusted value.3 In response to a higher unadjusted value, the machine owner's reservation value increases, as well. Intuitively, an increase in the degree of contact with the worker (") strengthens the bargaining power of workers, which unambiguously leads to higher wage offers - this will be called the thick matching effect. However, there are opposing effects of technological growth (8l) on wage offers in a similar way to the discussion of equalized worker values: (i) a positive capitalization effect (the denominator of the first term on the right-hand side of equation (9)), (ii) a negative waiting effect (the numerator of the first term on the right-hand side), and (iii) a positive net productivity effect (the second term on right side).

Because the positive capitalization effect dominates the negative waiting effect, the net effect of technological knowledge growth on wages is found to be positive.4 As job destruction increases, workers face a negative capitalization effect and a positive waiting effect. Although Aghion and Howitt (1994) study both channels, they focus primarily on the capitalization effect, without considering thickness-matching or waiting effects. Also note that an increase in job separations * discourages machine entry, which in turn reduces worker contact rates.

This inequality shares great similarity with the positive growth condition imposed in the endogenous growth literature, often referred to as the Jones-Manuelli (1990) condition. Furthermore, the steady-state flow matches measured by both the worker and machine sets must be identical and thus (4b) yields E0'0,. This equation implies that the rates of the matches increase in the measures of both sides.

As shown in Figure 1, such a solution exists in the Inada conditions imposed on the matching technology. Thus, equilibrium employment (or, the equilibrium measure of matched worker-machine pairs) E* is positively related to the degree of worker contact. While the equilibrium measure of search workers N* depends negatively on the degree of worker contact, the equilibrium measure of free machines M* depends negatively on the degree of machine contact but positively on that of the worker.

Existence and Uniqueness of Steady-State Exogenous-Growth Equilibrium) Under

Technology Adoption

This is a reasonable setup because the ex ante profit of each machine owner is zero due to free entry, so maximizing the respective worker's objective is equivalent to joint optimization. We prefer the former setting, as the use of an ex ante unadjusted value is more consistent with the concept of an ex ante technology adoption decision. In response to a higher rate of adoption of new technologies (increase in 8=80 s), existing jobs are shed more quickly (ie, endogenous job destruction effect).

8 If instead 8(s) is assumed to be a strictly concave function with lims648(s)l(s) An increase in the worker contact rate (") raises the expected value and thus encourages technology adoption. Conversely, an increase in either the rate of exogenous job destruction or the cost of machine entry discourages technology adoption activity. However, the effect of the rate of exogenous technology arrival is ambiguous depending on the size of the positive knowledge growth effect (via the designation e80sl(s)80l(s) in the marginal benefit function) and the positive capitalization effects (via the effective discount rate in JU) (0)) versus the negative endogenous destruction effect (via. Thus, the higher the adoption effort, the shorter the diffusion of the technology. While Chen and Shimomura (1998) allow search frictions to influence adoption efforts under a search intensity configuration, our paper considers both search and entry frictions as determinants of technology diffusion in a dynamic search framework. overall balance. Notably, in contrast to the conventional literature where multiplication is the result of increasing returns to production, multiple equilibria emerge in our model mainly due to interactions between endogenous matching and endogenous technology adoption in the absence of increasing returns. As the prior expected value increases, adoption returns are found to be higher, thus fulfilling the original prophecies. In contrast to the literature on steady-state search (e.g. Diamond, 1982a; Chen, 1995) or the literature on creative destruction with limit cycles (e.g. Aghion and Howitt, 1992), multiple equilibria in our model are associated with different balanced growth paths . This means that different equilibria involve different levels of adoption effort, as well as different levels of economic growth. In the absence of endogenous job destruction, an increase in the rate of exogenous technology arrival or average growth spurs the worker's contact rate, encourages adoption activity, and raises wages, although its influence on the overall wage dispersion is ambiguous because of the conflicting effects on the long-term unemployed and the newly unemployed. In the presence of global uncertainty, a small autonomous technological improvement can create a large long-run effect, lifting an economy from a low-growth trap to a high-growth equilibrium. Another is to further investigate the finding that the dynamic effect of technology adoption on the severity of creative destruction depends on the size of the job customization market. Benhabib, Jess and Roberto Perli, 1994, Uniqueness and indeterminacy: On the dynamics of endogenous growth, Journal of Economic Theory. Bond, Eric W., Ping Wang and Chong Yip, 1996, A Generalized Two-Sector Model of Endogenous Growth with Human and Physical Capital: Balanced Growth and Transition Dynamics, Journal of Economic Theory. Brock, William and David Gale, 1969, Optimal Growth under Factor Augmenting Process, Journal of Economic Theory. Chen, Been-Lon, 1995, Self-fulfilling expectations, history, and the big push: a search equilibrium model of unemployment, Journal of Economics. Chen, Been-Lon and Koji Shimomura, 1998, Self-fulfilling expectations and economic growth: a model of technology adoption and industrialization, International Economic Review. Fields, Gary S., 1685, Industrialization and Employment in Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan, in Walter Galenson ed., Foreign Trade and Investment Economic Growth in the Newly. Grossman, Gene and Elhanan Helpman, 1991, Innovation and Growth in the Global Economy, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Jones, Larry and Rodolfo Manuelli, 1990, A Convex Model of Equilibrium Growth: Theory and Policy Implications, Journal of Political Economy. Mortensen, Dale and Christopher Pissarides, 1994, Job Creation and Job Destruction in the Theory of Unemployment, Review of Economic Studies. Murphy, Kevin, Andrei Shelifer, and Robert Vishiny, 1989, Industrialization and the Big Push, Journal of Political Economy. Parente, Stephen and Edward Prescott, 1994, Barriers to Technology Adoption and Development, Journal of Political Economy. Xie, Danyang, 1994, Divergences in economic performance: transition dynamics with multiple equilibria, Journal of Economic Theory.Existence and Multiplicity of Balanced Growth Paths) Under the assumptions described as in

Conclusions