One exception is the ACT Framework for Measuring Social Norms Change Around FGM, which was developed as part of the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Program on the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation Accelerating Change, which includes a number of participatory research tools. Participatory research tools facilitate and engage the intended beneficiaries of social norms programming across its purpose, scope and.

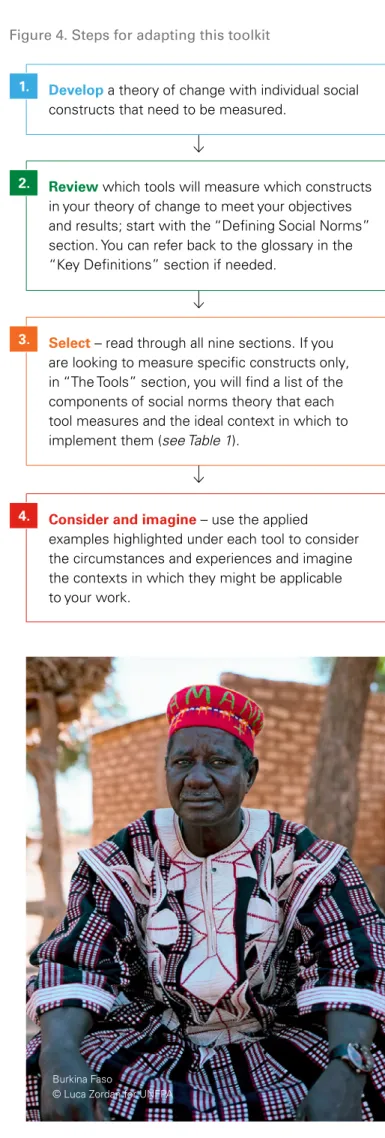

HOW TO USE THIS TOOLKIT

The use of participatory methods – either on their own or in combination with other quantitative or qualitative research efforts – is ideal for investigating social norms, offering several advantages over traditional research methods (see Figure 5). This toolkit does not go into detail about how to disseminate and utilize the information collected through participatory methods.

WHY USE PARTICIPATORY METHODS?

It deals with several components of social norms grouped into sociological factors that influence psychological factors (attitude, cognitive bias and self-efficacy) and the adoption of new behaviors and actions (Petit and Zalk, 2019). ACT emphasizes that social norms are bidirectionally related to knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes; social networks; and social support.

DEFINING

Another recent model, Everybody Wants to Belong, offers a broad approach to understanding the complexities behind how social norms persist and how change can best occur. Despite their growing popularity, there has been little global progress in developing evidence-based measures to assess whether social norms are having their intended effect.

SOCIAL NORMS

Individuals are motivated to follow norms because of expected outcomes; i.e. benefits and/or social sanctions expected for following or not following the norm (Mackie et al., 2015). One exception is the conceptual model for an ACT framework released as part of the joint UNFPA-UNICEF Program to End Female Genital Mutilation Advancing Change in December 2020, which addresses social norms related to female genital mutilation.

KEY DEFINITIONS

Allows the components of social norms (injunctive and descriptive norms, behavioral expectations, attitudes, and social rewards and sanctions) to be individually measured and compared so that norms can be understood at a deeper level. Used for a multitude of topics and contexts to specifically measure whether social norms are at play and, if so, what these social norms are, how common they are, and how they can best be addressed programmatically.

BODY

MAPPING

Use life-sized and sensory body maps when viewing body experiences related to the research topic. Life-size body maps take longer to complete because participants complete a large body outline.

WHEN TO USE THIS METHOD PRACTICAL EXAMPLES

When you ask each question, point to the body part it relates to on the sensory body map. Think about how things in the participants' lives could be changed to improve the results on the body map.

CONDUCTING THE ACTIVITY

However, if the life-size body maps are used, the questions can be broader; For example, ask the group or individual to explain what they drew and why and how what they drew relates to the research topic. The interpretation will generally consist of developing a list of themes from all body maps analyzed and interpreting the meaning behind these themes and how they influence normative factors. These data are best interpreted in combination with the more qualitative data from the life-size body maps and sensory body maps to compare how physiological knowledge interacts with psychosocial and experiential factors.

ANALYSING THE DATA

Divide data into groups based on participant characteristics for analysis (ie, gender, age, socioeconomic status, intervention-control, etc.).

INTERPRETATION

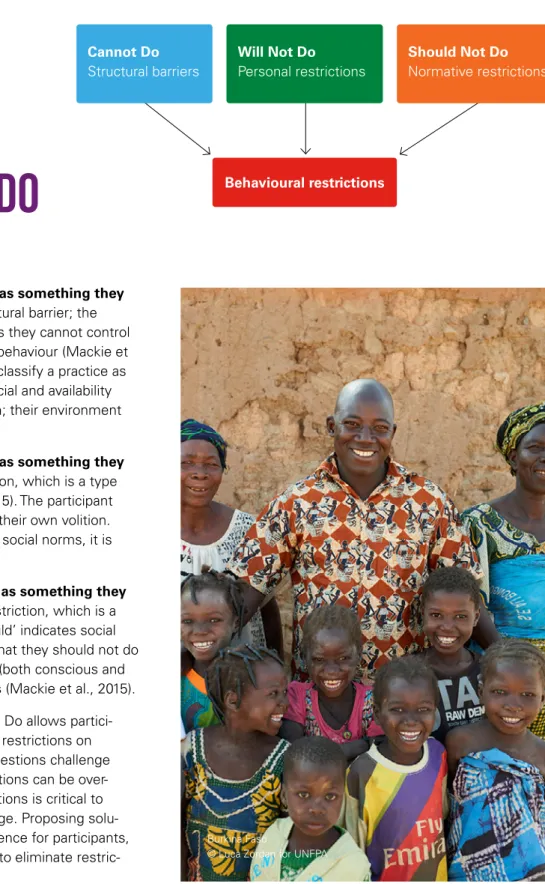

When the behavior is classified as something the participant cannot do, it is a structural barrier; the environment or other circumstances beyond their control prevent them from performing the behavior (Mackie et al., 2015). For example, they may classify a practice as something they cannot do due to financial and availability reasons.

CANNOT DO, WILL NOT DO,

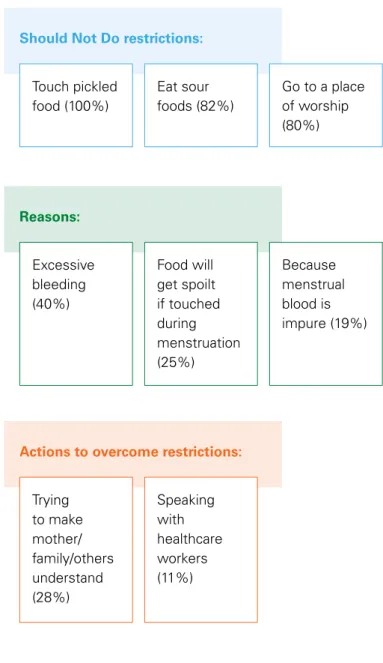

Can't do, won't do, must not do must be used to examine restricted behavior. The GARIMA evaluation incorporated the Can't do, won't do, must non-activity into focus group discussions with adolescent girls (UNICEF, 2018). The girls categorized each behavior as something they couldn't do, wouldn't do, or shouldn't do, and then described why they categorized it that way.

WHEN TO USE THIS METHOD

This activity will not be effective if the population engages in the behavior as the purpose is to categorize the reasons why they do not do it. Many of these restrictions are longstanding historical taboos that are still observed today, affecting girls' rights and perpetuating harmful beliefs and norms around menstruation. For all behaviors classified as things they shouldn't do, they were asked whether they did the behavior even though they "shouldn't".

PRACTICAL EXAMPLE

Cannot Do, Will Not Do, Should Not Do can be completed in both one-to-one and focus group discussion contexts. The following instructions describe how to do the Can't, Won't, Shouldn't do activity in focus group discussions. Make sure you have transcribed the Cannot Do, Will Not Do, Should Not Do data and transfer it to safekeeping.

ANALYSING THE DATA INTERPRETATION

Determine the frequency of each constraint by category (can't, mustn't, won't do) and list the most common constraints can't, won't, and mustn't. Determine the frequency of the most common/influential constraints listed and list the most common. Conduct a thematic analysis of probe data and report on the most common reasons for the existence of constraints and countermeasures.

COMPLETE- THE-STORY

Finish-the-story can be used in both one-on-one interviews and in focus group discussions. Go through a sample Complete-the-Story activity unrelated to the research topic. This provides a complete picture of the Complete-the-Story data, from which larger conclusions can be drawn.

WHEN TO USE THIS METHOD PRACTICAL EXAMPLE

To examine children's attitudes and social norms regarding positive discipline, children and adolescents in Jamaica were divided into four groups.3 Each group completed a free-list activity for one of four domains: "love." nurturing), "increase" (recognition), "setting rules". structure) and "get through the worst/get ready for life". The data showed how children and adolescents define effective parenting and captured cultural perspectives and beliefs about positive discipline. Most rule-setting words had a negative connotation, implying a programmatic need to focus on the positive side of constraints.

MENSTRUATION IS

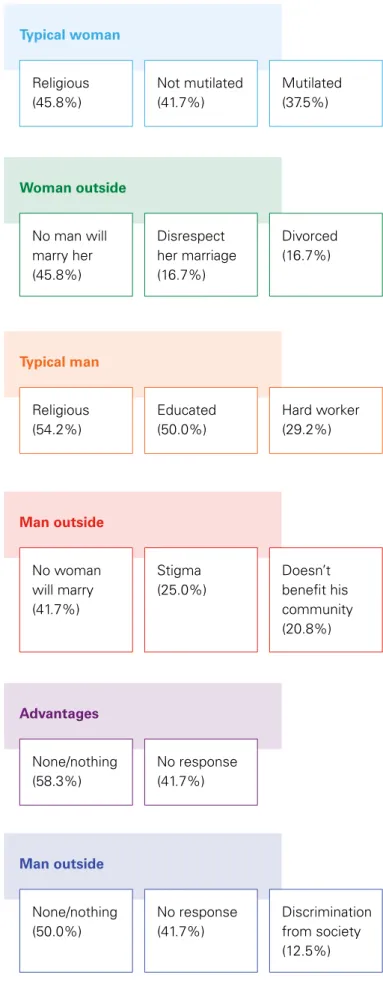

The ACT framework that has been developed to assess social and behavioral change related to FGM includes the Free Listing activity as part of the focus group discussion tool (UNICEF, 2019). Not breaking things' is a cultural belief that women who are not cut cannot control themselves and are thus prone to breaking things. The religion that supports the practice' was classified as a religious and social factor, highlighting how it is based on false beliefs that the Quran supports FGM and is supported by social norms that keep this belief in place.

WHY FGM

In general, however, the data will provide attitudes and views on social norms related to the chosen topic. Nevertheless, the data should be interpreted holistically and according to these categories and/or themes from the thematic analysis. As noted in the “Implementing the Activity” section above, data should be used to understand how participants define the domain (your topic), which can be used as part of formative research to ensure programming is culturally appropriate and targets attitudes and norms. in ways that will be relevant to the population.

Within the framework, participants describe the characteristics and behaviors of a “typical” man or woman (International HIV/AIDS Alliance, 2006). Participants are divided into two groups: one group fills in the gender field for a "typical" woman, and the other group fills in the gender field for. They write in the box the characteristics and behaviors expected of this "typical" man and woman.

Introduce the activity to the participants by explaining that you will distribute a set of cards with images and/or words on them and ask them to categorize the cards into one of the four columns as labeled on the large sheet of paper: “girls/women,” "boys/. Have the participants discuss the cards and then come to the sheet of paper and place the cards in the column where they think they belong. Make sure there is enough space to place all the cards on the sheet of paper so they can be seen (see Figure 22).

Because the nature of the Lifeline activity can vary, it has a wide range of applications. Determine what the time intervals on the lifeline will be; in other words, whether you want them to be predetermined (see Figure 25) or created by the participants (see Figure 24). Show them the lifeline diagram and explain the nature of the time intervals (that it starts from birth on the left and continues regardless of the last age interval you selected on the right).

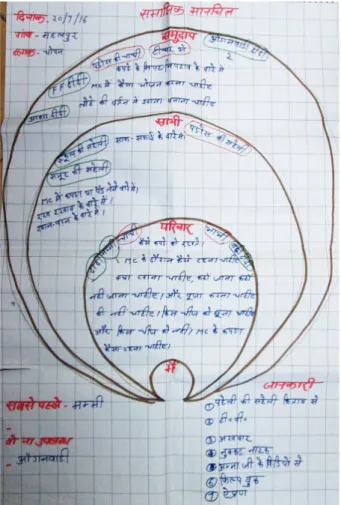

SOCIAL NETWORK

Social network mapping can be used when research questions focus on the flow of information, social support, and diagramming of reference groups around a particular topic. Menstrual health and hygiene management In rural India, social network mapping was used as part of the evaluation of the GARIMA initiative (see Figure 27). Determine the frequency of responses by level of the social network map and report the most frequent by level.

2X2 TABLES FOR SOCIAL

Institute for Reproductive Health, 'Resources for Measuring Social Norms: A Practical Guide for Program Implementers', 2019, accessed 26 July 2020. Petit, Vincent and Zalk, Tamar Naomi, 'Everybody Wants to Belong: A Practical Guide for Addressing and Promoting Social Norms in behavior change programming', 2019, accessed 26 July 2020. Sood, Suruchi, et al., 'ACT: An Evidence-Based Macro Framework for Examining How Communication Approaches Can Change Social Norms Regarding Female Genital Mutilation', Frontiers in Communication, vol.

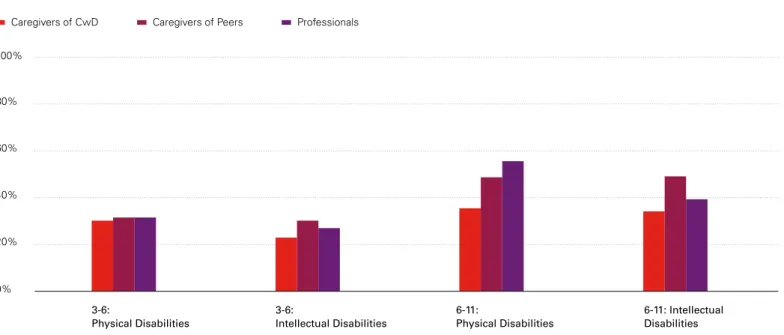

Cislaghi, Ben and Heise, Lori, "Measuring Gender-Related Social Norms: A Meeting Report", paper presented at the Social Norms and Gender-Based Violence Learning Group of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, January 2017. Sood, Suruchi, et al., Developing a Monitoring and Evaluation Framework for Tracking and Evaluating the Outcomes of Interventions to Change Discriminatory Attitudes and Social Norms Towards Children with Special Needs in Europe and Central Asia: Operational Research Protocol, 2019, [unpublished] . Towards a new M&E model for measuring changes in social norms around female genital mutilation, 2019, accessed 26 July 2020.