encrypted by the ISO TC 176 authors and offers, actionable, pragmatic advice for users and quality practitioners around the world on how to understand and effect the ISO 9000 family of documents. With so many competing publications on the subject, this 7th edition should be the essential, go-to handbook for quality professionals seeking to understand and benefi t from an ISO 9001 modelled quality system.

Sidney Vianna, Management System Professional, DNV GL, USA A must-have for anyone tasked with facilitating the creation and delivery of value to stake- holders, David Hoyle’s staggeringly powerful latest edition of Quality Systems Handbook expertly and thoroughly demystifi es the updated ISO 9000 Standards. An indispensable tool for managing quality and successful certifi cation.

John Colebrook, Director, Enhanced Operating Systems Ltd, New Zealand A valuable resource that explores salient concepts arising from the ISO 9001:2015 stan- dard in an unambiguous manner. David Hoyle using his inimitable step by step approach demonstrates the applicability of quality management standard to any organisational con- text. This book is defi nitely recommended reading for both academics and business lead- ers seeking to gain an in depth understanding of quality management systems.

Dr Lowellyne James, Lecturer in Quality Management, Robert Gordon University, IEMA Certifi cate in Sustainability Strategy Programme Leader, Scotland To be up-to-date with the latest in ISO 9000 Quality Systems (ISO9000:2015), this is the defi nitive guide to refer to. David Hoyle’s 7th edition stays true to its purpose of ensuring interpreting the Standard, comprehensible.

Christopher Seow, Visiting Lecturer “Six Sigma for Managers”

Cass Business School, City, University of London, UK David Hoyle pulls no punches in this very comprehensive seventh edition of his ISO 9000 Handbook. Whether you are a scholar, business executive, quality manager, consultant or a Certifi cation Body, this book is for you. He goes out of his way to change the miscon- ception of what the ISO 9001:2015 standard is really all about. He meticulously explains that it is aimed at improved performance and not just a set of requirements for compliance.

David convinces the reader that Quality should be managed as an integral part of every business.

Paul Harding, Managing Director, South African Quality Institute, South Africa Yet again David Hoyle has produced another excellent book that explains the new stan- dard and its requirements in straightforward terms. It is the book we have all been waiting for that will help us implement the new Standard and will become the new bible for qual- ity management Systems. If you follow the advice in Hoyle’s book you will not have any issues when the auditor arrives at your door. It is suitable for all people involved in the standard from company directors who need to know more about their responsibilities to experienced and busy Quality Managers who need to implement and inform others about the changes.

Rhian Newton, HSEQ Manager, Morgan Advanced Materials, UK The book does a great job of showing how a quality system built to the principles of ISO 9000 and conforming to the new ISO 9001:2015 requirements can be an integral part of leadership’s strategic approach to running the business versus letting a quality manage- ment system operate in a silo.

The book explores and explains the ISO9001:2015 requirements in a way that is easy to follow yet at the same time deep and meaningful especially for those new concepts and requirements such as leadership, context of the organization and managing risk. This feels like a book I’ll keep referring to for many years to come.

Richard Allan, Director, Quality Assurance, Kimberly-Clark Corporation, UK

Completely revised to align with ISO 9001:2015, this handbook has been the bible for users of ISO 9001 since 1994, helping organizations get certifi ed and increase the quality of their outputs.

Whether you are an experienced professional, a novice, or a quality management student or researcher, this is a crucial addition to your bookshelf. The various ways in which require- ments are interpreted and applied are discussed using published defi nitions, reasoned argu- ments and practical examples. Packed with insights into how the standard has been used, misused and misunderstood, ISO 9000 Quality Systems Handbook will help you to decide if ISO 9001 certifi cation is right for your company and will gently guide you through the terminology, requirements and implementation of practices to enhance performance.

Matched to the revised structure of the 2015 standard, with clause numbers included for ease of reference, the book also includes:

• Graphics and text boxes to illustrate concepts, and points of contention;

• Explanations between the differences of the 2008 and 2015 versions of ISO 9001

• Examples of misconceptions, inconsistencies and other anomalies

• Solutions provided for manufacturing and service sectors.

This new edition includes substantially more guidance for students, instructors and man- agers in the service sector, as well as those working with small businesses.

Don’t waste time trying to achieve certifi cation without this tried and trusted guide to improving your business – let David Hoyle lead you towards a better way of thinking about quality and its management and see the difference it can make to your processes and profi ts!

David Hoyle as a manager, consultant, author and mentor has been helping individuals and organizations across the world understand and apply ISO 9001 effectively since its inception in 1987. He has held senior positions in quality management with British Aero- space and Ferranti International and worked with such companies as General Motors, the UK Civil Aviation Authority and Bell Atlantic on their quality improvement programmes.

Although neither a member of ISO nor BSI technical committees, he has been a member of the CQI for over 40 years and through his work with them built a network of like- minded professionals including members of ISO and BSI technical committees, which gave him privileged access to many reports, presentations and early drafts and thus gained an insight into the thinking behind ISO 9001:2015.

ISO 9000 Quality Systems Handbook

Increasing the Quality of an Organization’s Outputs

Seventh Edition

David Hoyle

Seventh edition published 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2018 David Hoyle

The right of David Hoyle to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe.

First edition published by Butterworth-Heinemann 1994

Sixth edition published by Butterworth-Heinemann 2009 and by Routledge 2013

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hoyle, David, author.

Title: ISO 9000 quality systems handbook : using the standards as a framework for business improvement / David Hoyle.

Description: Seventh edition. | Abingdonm, Oxon ; New York, NY : Routledge, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifi ers: LCCN 2016056514 (print) | LCCN 2016057166 (ebook) | ISBN 9781138188631 (hardback : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781138188648 (pbk. : alk.

paper) | ISBN 9781315642192 (ebook) | ISBN 9781315642192 (eBook) Subjects: LCSH: ISO 9000 Series Standards—Handbooks, manuals, etc. | Quality control—Auditing—Handbooks, manuals, etc.

Classifi cation: LCC TS156.6 .H69 2017 (print) | LCC TS156.6 (ebook) | DDC 658.5/620218—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016056514 ISBN: 978-1-138-18863-1 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-18864-8 (pbk) ISBN: 978-1-315-64219-2 (ebk) Typeset in Times New Roman by Apex CoVantage, LLC

Visit the companion website: http://www.routledge.com/cw/hoyle

Preface to the seventh edition xiii

PART 1

Introduction 1

1 Putting ISO 9001 in context 3

2 Comparison between 2008 and 2015 editions 19

3 How the 2015 version has changed misconceptions 37

Key messages from Part 1 48

PART 2

Anatomy and use of the standards 51

4 The ISO 9000 family of standards 53

5 A practical guide to using these standards 61

Key messages from Part 2 84

PART 3

Terminology 87

6 Quality 91

7 Requirements 102

8 Management system 108

9 Process and the process approach 126

10 Risk and opportunity 148

11 Interested parties and stakeholders 159

Key messages from Part 3 168

x Contents PART 4

Context of the organization 171

12 Understanding the organization and its context 175 13 Understanding the needs and expectations of interested parties 188

14 Scope of the quality management system 199

15 Quality management system 210

16 Processes needed for the QMS 219

Key messages from Part 4 251

PART 5

Leadership 255

17 Leadership and commitment 257

18 Customer focus 283

19 Policy 289

20 Organizational roles, responsibilities and authorities 305

Key messages from Part 5 320

PART 6

Planning 323

21 Actions to address risks and opportunities 325 22 Quality objectives and planning to achieve them 347

23 Planning of changes 365

Key messages from Part 6 373

PART 7

Support 375

24 People 379

25 Infrastructure 387

26 Environment for the operation of processes 396

27 Monitoring and measuring resources 409

28 Organizational knowledge 428

29 Competence 439

30 Awareness 457

31 Communication 464

32 Documented information 478

Key messages from Part 7 514

PART 8

Operation 519

33 Operational planning and control 521

34 Customer communication 537

35 Requirements for products and services 551

36 Review of requirements for products and services 562

37 Design and development planning 575

38 Design and development inputs 597

39 Design and development controls 608

40 Design and development outputs 621

41 Design and development changes 630

42 Control of externally provided processes, products and services 637 43 Evaluation, selection and monitoring of external providers 649

44 Information for external providers 661

45 Control of production and service provision 671

46 Identifi cation and traceability 686

47 Property belonging to external providers 692

48 Preservation of process outputs 698

49 Control of changes 704

50 Release, delivery and post-delivery of products and services 708

51 Control of nonconforming outputs 719

Key messages from Part 8 730

xii Contents PART 9

Performance evaluation 733

52 Monitoring, measurement, analysis and evaluation 735

53 Customer satisfaction 747

54 Analysis and evaluation 756

55 Internal audit 771

56 Management review 791

Key messages from Part 9 804

PART 10

Improvement 807

57 Determining and selecting opportunities for improvement 811

58 Nonconformity and corrective action 818

59 Continual improvement of the QMS 839

Key messages from Part 10 846

Appendix A: Common acronyms 848

Appendix B: Glossary of terms 850

Bibliography 861

Index 868

Purpose and intended readership

This book is aimed primarily at professionals, researchers and students seeking to under- stand the concepts and requirements in the ISO 9000 family of standards in terms of what they mean, why they are necessary and how they might be addressed and confor- mity demonstrated. I have made no assumptions about my readers’ prior knowledge or experience. In recognition that those seeking guidance on ISO 9001 may be experienced professionals but also people at various levels in an organization with no prior knowledge or experience of ISO 9001 or managing quality, the book is intended to meet the needs of both groups. Explanations may therefore appear laboured to some readers but provide new insight to others.

There are over 300 requirements in ISO 9001:2015, and the explanation of each of these forms the major portion of the book. The book is therefore intended as a source of reference for those using the standard to obtain or maintain ISO 9001 certifi cation and as a tool to improve the quality of an organization’s outputs and seeking meaning, justifi cation and/or solutions.

Reason for the new edition

It is now 23 years since the fi rst edition of the Quality System Handbook , and each sub- sequent edition has either built on experience gained in developing management systems or has followed revisions in the standard. This new edition is prompted by the major revision of ISO 9001 in 2015. Unlike the 2008 version, which contained no changes in requirements, the 2015 version is a complete revision, fi rst to bring it in conformity with the new structure and common text of all new and future revisions of management system standards and second, to refl ect the changes in the trading environment and user needs and expectations. The new structure and common text were introduced in 2014 through ISO/

IEC directives that provide the rules to be followed by ISO committees. As ISO standards are reviewed every fi ve years, it was inevitable that any future revision would have to take account of applicable ISO/IEC directives. However, if you look closely at the standard, you’ll see that most of the requirements remain but are expressed in a different form. Less than a quarter are entirely new, but it will be the 20% of changes that give users 80% of the problems with the new version.

This seventh edition of the Handbook is a complete revision, but I have included many sections from the sixth edition where relevant. Although of comparable size to the sixth edition, a desire to maintain compatibility between the parts of the Handbook and the main

xiv Preface to the seventh edition

sections of the standard has led to there being 10 parts as opposed to 8 in the sixth edition and 59 chapters as opposed to 40 in the sixth edition. System assessment, certifi cation and continuing development that was in Part 8 of the sixth edition has been moved to the com- panion website, as have some of the appendices.

Correlation with ISO 9001 structure

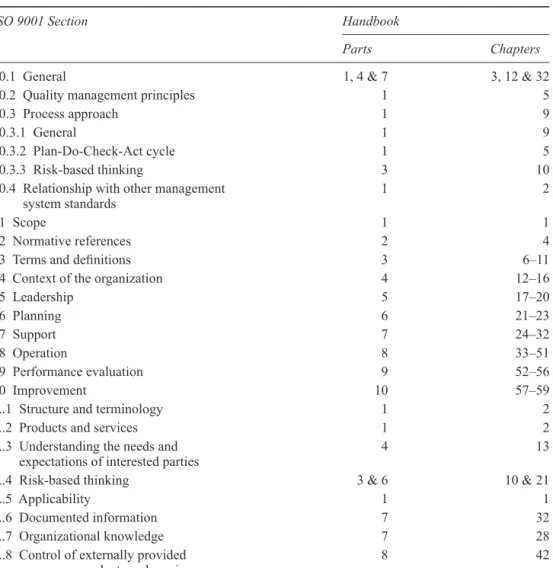

The standard was not written for authors to write books about it or to guide users in develop- ing a quality management system; if it had, the order in which the requirements are presented would have been different. Therefore, with very few exceptions, I have chosen to explain the requirements of the standard in the sequence in which they are presented in the standard and have added clause numbers to the headings to make it user friendly. Unlike previous editions, the Handbook now addresses all clauses of the standard, including those not con- taining specifi c requirements, as shown in the following table.

Table 0.1 Correlation with ISO 9001 structure

ISO 9001 Section Handbook

Parts Chapters

0.1 General 1, 4 & 7 3, 12 & 32

0.2 Quality management principles 1 5

0.3 Process approach 1 9

0.3.1 General 1 9

0.3.2 Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle 1 5

0.3.3 Risk-based thinking 3 10

0.4 Relationship with other management

system standards 1 2

1 Scope 1 1

2 Normative references 2 4

3 Terms and defi nitions 3 6–11

4 Context of the organization 4 12–16

5 Leadership 5 17–20

6 Planning 6 21–23

7 Support 7 24–32

8 Operation 8 33–51

9 Performance evaluation 9 52–56

10 Improvement 10 57–59

A.1 Structure and terminology 1 2

A.2 Products and services 1 2

A.3 Understanding the needs and

expectations of interested parties 4 13

A.4 Risk-based thinking 3 & 6 10 & 21

A.5 Applicability 1 1

A.6 Documented information 7 32

A.7 Organizational knowledge 7 28

A.8 Control of externally provided

processes, products and services 8 42

Preparation for the seventh edition

Being neither a member of ISO nor BSI technical committees, this independence has allowed me the freedom to comment on international standards without bias. However, I have been a member of the Chartered Quality Institute (CQI) and its predecessor, the Institute of Qual- ity Assurance (IQA), for over 40 years and through my work with them have built a net- work of like-minded professionals, some of whom are members of ISO and BSI technical committees.

I was involved with the IQA’s Standards Development Group (SDG) during the 1994 revision of ISO 9001 and in 2008 was invited to re-join the SDG by its then chair, Tony Brown, who was at that time a member of BSI TC QS/1 and the UK representative on TC 176/SC1 and TC 69. In January 2010, I was invited to lead a project on behalf of the CQI to infl uence the next revision of the ISO 9000 family of standards and specifi cally ISO 9000 and ISO 9001. The project team included representatives from academia, industry, BSI Technical Committees (TC), consultancy and auditing, so it was a good mix of peo- ple to work with. We were privileged to have access to many TC reports, presentations and early drafts and thus gain an insight into their thinking. Following a member survey, we received many hundreds of e-mails, which helped shape our views and prepare a position paper on the next revision of the ISO 9000 family of standards for the CQI. The paper was published in May 2011 and was well received by BSI and TC 176. The team also provided extensive comments on ISO Guide 83 (the forerunner to Annex SL), ISO 9000 and ISO 9001 during the development process. I captured feedback from several presentations I gave at CQI branch events, lengthy discussions I had with members of TC 176, including Dr Nigel Croft (chair of TC 176/SC2), and I engaged with contributors on LinkedIn up to and following the release of the fi nal versions of the two standards in September 2015.

In conducting research for this edition, I realized that the paradigm that has infl uenced the previous versions of ISO 9001, including the 2008 version, was that of scientifi c management, a belief that prescribing better ways of doing things and training people in those better ways will produce better quality outputs. There is no doubt that the appli- cation of scientifi c management does bring about great improvement in output quality, but it’s predicated on treating the organization as a machine in which the parts have no choice. In reality, an organization is far more complex. For one thing, it is multi- minded, meaning that everyone in it has a choice. Organizations are also infl uenced by external factors, and ignoring these factors will result in its current performance being unsustainable.

Our understanding of how organizations function has evolved since World War II, and ISO management system standards have not kept pace. With each revision of ISO 9001, a few concepts were changed or added that moved it beyond managing an orga- nization as if it were a machine to managing an organization as if it were a system of interdependent parts, but it’s become a hybrid of systems theory and scientific man- agement. During the development of this edition, I therefore encountered many issues that arose from ambiguities and inconsistencies in ISO 9000 and ISO 9001 that were not resolved by ISO TS 9002, the guide to the application of ISO 9001. Many of these arose first, from the definitions in ISO 9000 and the use of these terms in ISO 9001 and second, from the way requirements were expressed. At one stage I thought I’d not complete it at all as there were so many issues I had not resolved. But by ignoring some ISO definitions and putting my own interpretation on phrases like “establish,

xvi Preface to the seventh edition

implement and maintain a quality management system”, I think I have resolved these issues. Although many people may not choose to read the standards closely enough to appreciate these inconsistencies, it is important that they are highlighted and explana- tions provided.

One infl uential change in ISO 9001 has been the separation of product from service, and because the service sector is so diverse, I have used the example of a fast food outlet to illustrate how many of the requirements can be addressed. A fast food outlet has the advan- tage of being a provider of both products and services, and it’s one most readers will have experienced at one time or another so I reckoned they will relate to it.

On several occasions, I tried testing opinions using LinkedIn groups, but what I have learnt is that it is easy to be deluded into believing there is understanding, despite the fact there appears to be a consensus. Time and again I fi nd we don’t all attribute the same meaning to the words we use. The meaning is strongly infl uenced by how we see things, what we call a paradigm, and I have addressed this and other communication issues in the book. The views I express mainly result from research and deduction rather than conjecture, and I have tried to present explanations that are faithful to the intent of the standard.

How to use the book

The contents list shows the parts and chapters of the book, and the chapter headings mirror the major clause headings of ISO 9001 from Chapter 12 onwards. A contents list is included in the introduction to each chapter, and the section headings are consistent with the sub- clauses or subject of the requirements within a clause. This should make it relatively easy to navigate the book.

I realize it’s a hefty tome which may appear daunting to those unfamiliar with this work;

therefore, for those readers who want a quick summary of each of the 10 parts, I have included a small number of pages at the end of each part that contain a few key messages from each chapter.

Although the book may be used as a source of reference where readers may look up a clause to fi nd out what a requirement means, why it’s necessary or how to address it or audit it, it is strongly recommended that the chapters in Parts 1 , 2 and 3 be studied fi rst. The rea- son for this is that without an understanding of the concepts, principles, terminology, recent changes, common misconceptions and different approaches, an unprepared reader can eas- ily misinterpret what is written, both in the standard and in this book. The ways in which the term quality is commonly used may create fewer problems because its use in ISO 9001 is limited to specifi c concepts, but differences in the ways the terms risk, system, process, procedure and interested party are used may result in requirements being interpreted far dif- ferently from that which is intended.

In previous editions, the requirements of the standard have been paraphrased, but that has required the prior approval of BSI as the UK copyright holder. It is believed that this is no longer necessary, as judicious phrasing of chapter and section headings together with cross-references to clause numbers can achieve the same objective, but it is obviously desirable for users of this Handbook to have copies of ISO 9001:2015 and ISO 9000:2015 to hand.

Extensive use of cross-referencing is made throughout the book to avoid repetition. At the end of each chapter is a bibliography listing all the cited references in the chapter, and these are also recommended for further reading. As only chapters are numbered, cross-referencing

to sections is by the ISO 9001 clause number that appears in the section heading. Also as tables, fi gures and text boxes are identifi ed with the chapter number, this facilitates cross- referencing to specifi c locations within a chapter or section. Although tables and fi gures are referenced within the text, this is not always the case for text boxes.

As the Handbook addresses the requirements of ISO 9001, I decided to use the language of ISO 9001 to avoid any confusion. In the sixth edition I referred to a management system rather than a quality management system, but I have found that this could create ambiguities because it’s clear from the requirements of ISO 9001 that they only apply to part of the man- agement system. It may be a large part of the management system, but nonetheless implying otherwise would be confusing to say the least.

Companion website

A companion website will be created which contains checklists, examples of forms, case studies, PowerPoint presentations and other pedagogical features as they become available.

See bottom of page vi for the url Acknowledgements

I can’t take credit for all the ideas expressed in this book. Some are my own, and some are from the people with whom I have had discussions, but many come from management philosophies, theories and techniques that have been pertinent to the fi eld of quality manage- ment over the last 100 years. I have included over 150 citations from literature and over 24 citations from related ISO documents. I am indebted to Chris Cox, Chris Paris, Iain Moore, Janette Large, John Broomfi eld, John Colebrook, Mustafa Ghaleiw, Nigel Croft, Olec Kova- levsky, Paul Harding, Peter Fraser, Rhian Newton, Richard Allan, Sidney Vianna, Winston Edwards and the late Tony Brown with whom I have corresponded over the last eight years or so and who helped form my views on various aspects of ISO 9001 and ISO 9000. They each brought a different perspective to the discussions and helped reveal to me interpreta- tions I hadn’t considered. It was good to be able to share ideas with a group of professionals I knew and could trust.

Tony Brown was my ardent companion on this journey, always providing support and encouragement until his untimely illness and death dealt a devastating blow and cut short our almost daily Skype calls. Winston Edwards has helped enormously with the chapter on management systems, and Chris Cox from TC 176/SC1 was invaluable for his knowledge about ISO defi nitions and their development. I would also like to convey special thanks to Peter Fraser, Rhian Newton and Richard Allan who provided useful input and helped scrutinize several chapters of the manuscript, providing numer- ous suggestions for improvement. I am also indebted to my former business partner, John Thompson, who many years ago changed the way I think about so many different aspects of management and infl uenced the views on process management and the ser- vice industry presented in this book. There are also countless others with whom I have engaged in one way or another and shared views and experiences that in some way will have infl uenced something I have written in this book. From Taylor & Francis, I would like to thank Amy Laurens, my commissioning editor, and Nicola Cupit and Laura Hussey, editorial assistants, who arranged the independent reviews and have provided excellent support in the preparation of the manuscript. I also pay tribute to Tina Cottone for her project leadership skills, patience and cooperation in editing the fi rst proof and

xviii Preface to the seventh edition

bringing it up to T&F’s production standards. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Angela, who has been so patient these past 18 months while I laboured away working on the manuscript, often working into the early hours so as not to lose an idea. It is my wish that all readers will learn something from these pages that will not only enable them to increase the quality of their organization’s outputs, but also provide a source of inspiration in the years to come.

David Hoyle

Monmouth

November 2016

E-mail: [email protected]

Introduction

Introduction to Part 1 Consider these two scenarios:

A. The organization already exists; it is delivering services and providing products and services to customers, but getting quite a few complaints so it’s becoming diffi cult to compete on quality. It is making a profi t but not enough to invest for the future because the managers spend a lot of time fi refi ghting instead of improving the effi ciency and effectiveness of their processes. It’s doing what it can to comply with regulations but occasionally breaches employment laws and environmental legislation as it strives to balance competing objec- tives. No matter how many times problems are fi xed, similar problems seem to arise again elsewhere, and often quick fi xes lead to bigger problems much later.

B. The organization already exists; it is delivering services and providing products and services to customers and mostly receiving compliments, but competition is tough. It is making enough profi t to invest for the future because its managers are proactive, putting a lot of effort into ensuring risks to success are mitigated. Thus, this organi- zation doesn’t need to spend much time fi refi ghting and can instead pursue opportunities for improving the effi ciency and effectiveness of its processes. By striving to satisfy customers in a way that meets the needs of the other stakeholders, it has found it can balance competing objectives and has not had compliance issues of any signifi cance.

When problems arise, managers tend not to go for the quick fi x, but spend time ensur- ing that actions to prevent their recurrence won’t have adverse consequences later.

These scenarios represent situations where both organizations are likely to obtain ben- efi ts from adopting ISO 9001:2015. In scenario A, the organization will gain a competitive advantage from a signifi cant improvement in its performance and demonstrable capabil- ity, and in scenario B, the organization will gain a competitive advantage by demonstrable capability. Most organizations are likely to be positioned between these two extremes and will therefore benefi t to varying degrees from adopting ISO 9001:2015. Creating a competi- tive advantage in quality should be a goal of top management, and perhaps the most widely recognized tool for doing this is ISO 9001. The standard can be used in ways that make your organization less competitive, which is why it is so important that you digest Part 1 of this book fi rst before deciding on your course of action.

In Chapter 1 we put the ISO 9000 family of standards in context. We examine its purpose, scope, content and application and the process by which it was developed. We include some statistics on its use and summarize the expected outcomes of accredited certifi cation.

2 Introduction

In Chapter 2 we compare the 2008 and 2015 editions, highlighting the signifi cant changes, the rationale for the change in structure, the new requirements and the withdrawal of some requirements that were introduced in the fi rst version nearly 30 years ago.

In Chapter 3 we examine the many misconceptions about the ISO 9000 family of stan- dards that have grown since its inception. There are many views about the value of ISO 9001 certifi cation, some positive and some negative. It has certainly spawned an industry that has not delivered as much as it promised, and even with the release of the 2015 version there is still much to be done to improve the standards, improve the image, improve the associated infrastructure and improve organizational effectiveness.

Introduction

There shall be standard measures of wine, ale, and corn (the London quarter), throughout the kingdom. There shall also be a standard width of dyed cloth, russet, and haberject, 1 namely two ells within the selvedges. 2 Weights are to be standardised similarly.

(Magna Carta, 1215) In the 800th anniversary year of Magna Carta, the International Organization for Standard- ization publishes a major revision to its most popular standard, ISO 9001. As will be under- stood from the quotation, standards have been used for centuries – in fact standards for quality have been traced as far back as 11th century BCE in China’s Western Zhou Dynasty, but the notion of quality systems emerged after World War II when the industrial practices were still largely based on scientifi c management as defi ned by Frederick Winslow Taylor at the turn of the 20th century.

Box 1.1 Steve Jobs on quality

Customers don’t form their opinions on quality from marketing, they don’t form their opinions on quality from who won the Deming Award or who won the Baldridge Award. They form their opinions on quality from their own experience with the prod- ucts or the services.

(Jobs, 1990)

Many people have started their journey towards ISO 9001 certifi cation by reading the standard and trying to understand the requirements. They get so far and then call for help, but they often haven’t learnt enough to ask the right questions. The helper might assume that the person already knows they are looking at ISO 9001 and therefore may not spend the necessary time for them to understand what it is all about, what pitfalls may lie ahead and whether, indeed, they need to make this journey at all. This should become clear when you read this chapter.

When you encounter ISO 9001 for the fi rst time, it may be in a conversation, on the Inter- net, in a leafl et or brochure from your local chamber of commerce or, as many have done, from a customer. If you are a busy manager you could be forgiven for either putting it out of your mind or getting someone else to look into it. But you know that as a manager you are

4 Part 1 Introduction

either maintaining the status quo or changing it, and if you stay with the status quo for too long, your organization will go into decline. So, you need to know whether there is an issue with product or service quality and:

• What the issue is?

• Why it’s an issue?

• What it’s costing you?

• What you should do about it?

• What the impact of it will be?

• How much it will cost to improve performance so that these types of issues don’t recur?

• Where the resources are going to come from?

• When you need to act?

• What the alternatives are and their relative costs?

• What the consequences are of doing nothing?

In this chapter, we put ISO 9001 in context by explaining:

• What ISO 9001 is intended to do, making the link between ISO 9000 and the funda- mental basis for trade

• The process by which international standards are developed and the roles of the various groups involved

• Reasons for using ISO 9001 – the interdependent duo of capability and confi dence • The scope of ISO 9001 and what it means

• Applicability of ISO 9001 – why it’s diffi cult to rule anything out • Design or assessment standard – the users’ choice

• ISO 9001 and the free movement of goods and services

• Popularity of ISO 9001 certifi cation – some facts, fi gures and trends • What accredited certifi cation means and doesn’t mean

What ISO 9001 is intended to do

Box 1.2 ISO 9000 in a nutshell

The standards were created to facilitate international trade.

Organizations use ISO 9001 to demonstrate their capability and in so doing give their customers confi dence that they will satisfy their needs and expectations and are committed to continual improvement.

Customers use ISO 9001 to obtain an assurance of product and service quality that they can’t get simply by examining them.

All other standards in the ISO 9000 family address particular aspects of quality management.

Since the dawn of civilization, the survival of communities has depended on trade. As communities grow, they become more dependent on others providing goods and services they are unable to provide from their own resources. Trade continues to this day on the

strength of the customer–supplier relationship. The relationship survives through trust and confi dence at each stage in the supply chain. A reputation for delivering a product or a service to an agreed specifi cation, at an agreed price, on an agreed date is hard to win, and organizations will protect their reputation against external threats at all costs.

But reputations are often damaged, not necessarily by those outside, but by those inside the organization and by other parties in the supply chain. Broken promises, whatever the cause, harm reputation, and promises are broken when an organization does not do what it has committed to do. This can arise either because the organization accepted a commitment it did not have the capability to meet or it had the capability but failed to manage it effectively.

This is what the ISO 9001 is all about. It is a set of criteria that, when satisfi ed by an organization, enable it to demonstrate its capability and in so doing give their customers confi dence that they will meet their needs and expectations. Customers use it to obtain an assurance of product and service quality that they can’t get simply by examining them. It can be applied to all organizations regardless of type, size and product or service provided.

When applied correctly these standards will help organizations develop the capability to cre- ate and retain satisfi ed customers in a manner that satisfi es all the other stakeholders. They are not product or service standards – there are no requirements for specifi c products or services – they contain criteria that apply to the management of an organization in satisfying customer needs and expectations in a way that satisfi es the needs and expectations of other stakeholders.

Box 1.3 ISO standards

ISO develops only those standards that are required by the market. This work is car- ried out by experts coming from the industrial, technical and business sectors which have asked for the standard, and which subsequently put them to use.

(ISO, 2009)

ISO standards are voluntary and are based on international consensus among the experts in the fi eld. ISO is a non-governmental organization, and it has no power to enforce the implementation of the standards it develops. It is a network of the national standards bodies from 162 countries, and its aim is to facilitate the international coordination and unifi cation of industrial standards.

Most internationally agreed standards apply to specifi c types of products and services with the aim of ensuring interchangeability, compatibility, interoperability, safety, effi ciency and reduction in variation. Mutual recognition of standards between trading organizations and countries increases confi dence and decreases the effort spent in verifying that suppliers have shipped acceptable products or delivered acceptable services.

The ISO 9000 family of standards is just one small group of standards among over 19,500 internationally agreed standards and other types of normative documents in ISO’s portfolio that are instrumental in facilitating international trade.

The standards in the ISO 9000 family provide a vehicle for consolidating and communi- cating concepts in the fi eld of quality management. It is not their purpose to fuel the certifi - cation, consulting, training and publishing industries. The primary users of the standards are intended to be organizations acting as either customers or suppliers.

6 Part 1 Introduction

You don’t need to use any of the standards in the ISO 9000 family to develop the capability of satisfying your stakeholders; there are other models, but none are more widely used.

Overview of the ISO standards development process

To understand why the 2015 version of ISO 9001 is the way it is, an appreciation of the standards development processes is necessary.

The International Organization of Standardization (ISO) is a network of national stan- dards bodies (NSB). Each member represents ISO in its country. Individuals or companies cannot become ISO members. ISO standards are developed by groups of experts which form technical committees (TCs). Each TC deals with a different subject and is made up of representatives of industry, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), governments and other stakeholders, who are put forward by ISO’s members. Being nominated as an expert doesn’t mean a person is academically qualifi ed or is more knowledgeable than anyone else in a subject. They must be able to demonstrate expertise to their peers on the TC in some area of the committee’s work and be available to attend ISO committee meetings wherever they are convened. Not every subject matter expert can commit to this level of participation, as it can be quite time consuming. The experts are not employees of ISO, and therefore ISO’s role is as a facilitator rather than a developer of standards, as it doesn’t fund their development.

The process stages are as follows:

1 New standard is proposed to TC. This is the Proposal stage , and if the proposal is accepted it moves to stage 2.

2 Working group of experts (WG) start discussion to prepare a working draft. This is the Preparatory stage which, when complete, the working draft moves to stage 3.

3 First working draft (WD) is shared with the TC and with ISO CS (Central Secretariat).

If the committee uses the Committee stage , a committee draft (CD) is circulated to the members of the committee, who then comment and vote. If consensus is reached within the TC, it moves to stage 4.

4 Draft international standard (DIS) is prepared and shared with all ISO national mem- bers, who have three months to comment. This is the Enquiry stage , and if consensus is reached it moves to stage 5.

5 Final draft (FDIS) is sent to all ISO members. This is the Approval stage , and the standard is approved if a two-thirds majority of the participating members (P-members) of the TC/SC is in favour and not more than one-quarter of the total number of votes cast are negative. Only editorial corrections are made to the final text.

6 The ISO international standard is published.

As can be seen, there are two stages where the decision to proceed is based on consensus rather than unanimity. ISO standards are reviewed every fi ve years to determine whether they should be revised, withdrawn or confi rmed extant for a further fi ve years, and those that are to be revised pass through the aforementioned process. Further details are on the ISO website (ISO-SD, 2016).

Reasons for using ISO 9001

Trading organizations need to achieve sustained success in a complex, demanding and ever- changing environment. This depends on their capability to:

a) anticipate and/or identify the needs and expectations of their customers and other stakeholders;

b) convert the anticipated or identifi ed needs and expectations of customers into products and services that will satisfy all stakeholders;

c) attract customers to the organization;

d) supply the products and services that meet customer requirements and deliver the expected benefi ts;

e) operate in a manner that satisfi es the needs of the other stakeholders.

Many organizations develop their own ways of working and strive to satisfy their customers in the best way they know how. We will explain this further in more detail, but in simple terms the management system enables the organization to do (a)–(e) and includes both a technical capability and a people capability. Many organizations develop the technical capa- bility but not the people capability and are thus forever struggling to do what they say they will do.

In choosing the best solution for them, they can either go through a process of trial and error, select from the vast body of knowledge on management or utilize one or more manage- ment models available that combine proven principles and concepts to develop the organiza- tion’s capability. ISO 9001 represents one of these models. Others are Business Excellence Model, Six Sigma and Business Process Management (BPM).

Box 1.4 Food for thought

Many ISO 9001–registered organizations fail to satisfy their customers, but this is largely their own fault – they simply don’t do what they say they will do, and even those that do may not be listening to their customers. If your management is not pre- pared to change its values, it will always have problems with quality.

Having given the organization the capability to do (a)–(e) above, in many business-to- business relationships, organizations are able to give their customers confi dence in their capability without becoming registered to ISO 9001. In some market sectors, there is a requirement to demonstrate capability through independently regulated conformity assess- ment procedures before products and services are purchased. In such cases the organization has no option but to seek ISO 9001 certifi cation if it wishes to retain business from that particular customer or market sector. However, conformity with ISO 9001 may not be a USP (unique selling point) in the markets that some organizations operate, as it no longer confers special status. It may already be perceived as a given without certifi cation being expected or mandated.

8 Part 1 Introduction Scope of ISO 9001

The scope of ISO 9001 is expressed in clause 1, and it’s worth pulling this apart to explain the concepts it contains because it’s an essential part of the standard that is often overlooked.

Requirements for a quality management system

ISO 9001 is not a quality management system (QMS); it contains requirement for a QMS.

These are requirements that the industry representatives of national standards bodies believe will adversely affect the quality of products and services were they not to be met. A QMS is that part of an organization’s management system that creates and retains customers by understanding their needs and designing and providing products and services that satisfy those needs (see Chapter 8 for further explanation).

Need to demonstrate its ability

Levels of confi dence

It is clearly stated that the standard is for use by organizations that need to demonstrate their ability, but where would that need come from? From its inception ISO 9001 has been a business-to-business standard. Customers need confi dence that their suppliers can meet their quality, cost and delivery requirements and have a choice as to how they acquire this confi dence. They can select their suppliers:

a) purely based on past performance, reputation or recommendation. (This option is often selected for general services, inexpensive or non-critical products coupled with some basic receipt or service completion checks.);

b) by assessing the capability of potential suppliers themselves. (This option is often selected for bespoke services and products where quality verifi cation by the purchaser is possible.);

c) based on an assessment of capability performed by a third party. (This option is often selected for professional services and complex or critical products where their quality cannot be verifi ed by external examination of the output alone.).

Most customers select their suppliers using option (a) or (b), but there will be cases where these options are not appropriate because there is no evidence for using option (a) or resources are not available to use option (b), or it is uneconomic to travel halfway around the world when an accredited certifi cation body is on the spot to do the same job. Whether the certifi cation body would do this job as well as the customer is the subject of much debate and is not an issue addressed by ISO 9001. ISO 9001 was developed for use in situations (b) and (c), enabling customers to impose common QMS requirements on their suppliers and either assess those suppliers themselves or use third-party audit as a means of obtaining confi dence that their requirements will be met.

Overview of certifi cation process

An organization wishing to do business with a customer and assure them they can meet their requirements submits to a second-party audit performed by their customer or a

third-party audit performed by an accredited certifi cation body independent of both cus- tomer and supplier. An audit is performed against the requirements of ISO 9001, and if no major nonconformities are found, a certifi cate is awarded. This certifi cate provides evidence that the organization has demonstrated its ability to meet certain requirements.

Customers are now able to acquire the confi dence they require, simply by establishing whether a supplier holds a current ISO 9001 certifi cate covering the types of products and services they are seeking. However, the credibility of the certifi cate rests on the competence of the auditor and the integrity of the certifi cation body, neither of which are guaranteed.

If an organization’s customers are not demanding ISO 9001 certifi cation, the use of ISO 9001 is optional (i.e. there is no need to demonstrate its ability). However, many organi- zations wish to use ISO 9001 to create a competitive advantage in their market and may perceive there are tangible benefi ts from obtaining ISO 9001 certifi cation. In such cases the need arises from top management rather than the customer. It is important to recognize that there is no requirement in the ISO 9000 family of standards for certifi cation. Only where customers are imposing ISO 9001 in purchase orders and contracts would it be necessary to obtain ISO 9001 certifi cation.

Meeting customer requirements

It is often believed that the customer requirements referred to in ISO 9001 are those specifi ed by the customer verbally or in writing, but this is untrue. ISO 9000:2015 defi nes a require- ment as a “need or expectation that is stated, generally implied or obligatory”. It therefore includes specifi ed requirements as in those defi ned in a contract, order or specifi cation, but also standards that a reasonable person would regard as expected such as safety, reliability and maintainability. These are discussed further in Chapter 35 .

It is also often believed that the customer referred to in ISO 9001 is the person or organi- zation that purchases the organization’s products or services, but again this in untrue. ISO 9000:2015 defi nes a customer as a “person or organization that could or does receive a prod- uct or a service that is intended for or required by this person or organization”. It therefore includes the consumer, client, end user, retailer, benefi ciary and purchaser. The customer is therefore anyone who may use your products and services however they may have come by them. But a person may have acquired your organization’s products, and regardless of how long after they were put on the market, if they were intended for their use, they are classed as customers for the purposes of ISO 9001.

Meeting applicable statutory and regulatory requirements

Box 1.5 What are statutory and regulatory requirements?

Statutory requirements are obligatory requirements specifi ed by a legislative body (persons who make, amend or repeal laws).

Regulatory requirements are obligatory requirements specifi ed by an authority mandated by a legislative body (e.g. an agent of a national government).

(ISO 9000:2015)

10 Part 1 Introduction

ISO 9001 is not requiring your organization to meet all statutory and regulatory require- ments. The word applicable in the scope statement means those statutory and regulatory requirements that are applicable to the product or service being provided. These require- ments differ depending on the sector of the population, country, market and industry sector (see also Chapter 18 ).

If there is a law prohibiting the sale of products containing certain substances, that statutory requirement applies to the products offered for sale. It does not prohibit such substances being used in manufacturing processes providing they don’t contaminate the product supplied. If there is a law granting maternity leave to employees, this applies to the organization but not the product or service being supplied. However, if there is a law governing hygiene in places where food is consumed, it applies to the organization and not the product offered, but will apply to any service offered where food is consumed as part of the service.

Consistently provide products and services

The ability the organization needs to demonstrate is an ability to “consistently” pro- vide products and services of a certain standard. The key concept here is “consistent provision”, which is important because it has more than one meaning. The word con- sistent means “Remaining in the same state or condition” ( Oxford English Dictionary , 2013) but is it a specifi c product or service that should remain consistent or the meeting of customer and applicable statutory and regulatory requirements that should remain consistent?

The concept of consistent provision was introduced in the 2000 version of the stan- dard. Demonstrating an ability to consistently provide products and services that meet customer and applicable statutory and regulatory requirements, which now includes their needs and expectations, therefore means not only meeting those requirements in every product and service that is provided to every customer, but also possessing the ability to anticipate future requirements of customers and offer products and services that will meet their requirements. Put another way, “consistently provide” can mean that every Ford Mondeo we provide meets the specifi cation for that model of car. But it can also mean every time we provide a car, it will meet the customer’s needs and expectations regard- less of its specifi cation.

This extension in scope was not obvious in the 2000 and 2008 versions, but in the 2015 version it is expressed through requirements in clause 8.2.2 and 8.2.3, where it addresses the determination and review of requirements related to products and services to be offered to customers and where it required product and service improvements to address future needs and expectations in clause 10.1a). The phrase “to be offered” implies an intention and there- fore no longer does the standard only apply after a customer has expressed an interest in the organization’s products and services but applies before a customer is even aware of the organization’s products and services. Why the change? Well, some organizations are reactive, reacting to what customers’ demand of them and aiming to satisfy their needs and expectations. Then there are others that are proactive, aiming to create a need and expecta- tion and offering products and services the customer had not even dreamed of. The organiza- tion seeks opportunities to create new customers and through its marketing builds customer expectations. The products and services it eventually provides need to consistently meet

these expectations, and this is expressed through the requirement in clause 8.2.2d where it states “the organization shall ensure that it can meet the claims for the products and services it offers.”

Enhancing customer satisfaction

The standard has referred to meeting customer requirements so it may appear tauto- logical to place “meet customer requirements” in clause 1a)” and “enhance customer satisfaction” in clause 1b), but one may satisfy customers by meeting most of their requirements and enhance customer satisfaction by meeting all their requirements, which, as we have stated, means meeting stated, generally implied or obligatory needs and expectations.

Applicability of ISO 9001

There are several possible situations where the requirements of ISO 9001 could be deemed applicable:

A. After an organization has received a contract or order for specifi c products and services

B. When a customer has indicated an intention to place a contract or order for specifi c products and services

C. When a customer has expressed an interest in the organization’s capability

D. When an organization seeks to create a new market for existing products and services

E. When an organization seeks opportunities for developing new products and services in its chosen market

ISO 9001 was introduced to facilitate national and international trade between orga- nizations and was therefore a tool of business-to-business relationships. The premise on which the fi rst edition of ISO 9001 was based was that customers would be seeking suppliers that were able to demonstrate they could provide products and services that satisfi ed their requirements. Until the 2015 edition, ISO 9001 applied to situations A, B and C. In these situations, the product or service being offered already existed, with one exception; in situation C the customer may be attracted to the supplier because of its potential capability to design a product or service to their performance specifi cation. In situations D and E, the requirements for a product or service have yet to be determined and there is no specifi c customer – only an unsatisfi ed need or potential want has been identifi ed, and the organization may not yet have developed the necessary capability to satisfy it. In the 2015 revision, the applicability of ISO 9001 was extended to include situations D and E.

The requirements specifi ed in the standard are complementary to requirements for products and services. In fact there are no product or service requirements in the standard – all the requirements apply to the organization, but which parts of an organization? As will be seen so far, the focus of ISO 9001 is on customers; therefore, it does not apply to other

12 Part 1 Introduction

stakeholders except in so far as they affect the ability of the organization to consistently provide products and services that satisfy its customers. The standard does not apply to management of the environment, occupational health and safety, fi nances, business risks and any other factor, provided those factors do not positively or negatively affect the ability of the organization to consistently provide products and services that satisfy its customers. However, it should not be assumed these factors are outside scope altogether.

One property of a system is that everything is connected to everything else, so it is dif- fi cult to rule anything out.

Used for design and assessment purposes

When reading ISO 9001 it is easy to be confused over its purpose. The scope in clause 1 implies it’s used to demonstrate ability, but when readers reach clause 4.4 they’ll fi nd that it requires a QMS to be established, thus in effect implying that the standard is used to design a QMS. When ISO 9001 is invoked in contracts, this requirement could be interpreted as requiring a QMS to be established specifi cally for the contract. In fact, it is used for both design and assessment purposes, but there are only 5 requirements for the organization to demonstrate something that would be indicative of a standard used for assessment purposes, and there are 50 requirements for something to be either determined or established, which is indicative of a standard used for design purposes. Although ISO 9001 can be used to design a QMS, it was intended to be used in contractual situations by customers seeking confi dence in their supplier’s capability.

The quest for confidence through regulated standards evolved in the defence indus- try. Defence quality assurance standards were based on the principle that when con- tractors can substantiate by objective evidence that they have systems in place to maintain control over the design, development and manufacturing operations and have performed inspection which demonstrates the acceptability of products and services, the customer can be assured that the products and services will be or are what they are claimed to be and will be, are being and have been produced under controlled conditions.

ISO 9001 and the free movement of goods and services

With the formation of the European Union (EU) in 1993 there was a need to remove bar- riers to the free movement of goods across the Union. One part of this was to harmonize standards. At the time, each country had its own standards for testing products and for controlling the processes by which they were conceived, developed and produced. This led to a lack of confi dence and, consequently, to the buying organizations undertaking their own product testing and, in addition, assessment of the seller’s quality manage- ment systems. The Council of the European Union has therefore adopted a common framework for marketing products. This broad package of provisions is intended to remove obstacles to the free circulation of products and represents a major boost for trade in goods between EU member states. ISO 9001 is perceived by the EU Council as ensuring health and safety requirements are met because ISO 9001 now requires organizations to demonstrate that they have the ability to consistently provide a product

that meets customer and applicable statutory and regulatory requirements. Such require- ments would be specifi ed in EU directives. Where conformity with these directives can be verifi ed by inspection or test of the end product, ISO 9001 is not a requirement for those seeking to supply within and into the EU. Where conformity cannot be ensured without control over design and/or production processes, conformity with ISO 9001 needs to be assessed by a “ notifi ed body ”.

Since the formation of the EU, several other “common markets” have been formed throughout the world adopting many of the founding principles of the EU. These common markets are currently as identifi ed here:

1 European Union Single Market (EU) of 28 countries

2 Sistema de la Integración Centroamericana (SICA) of 8 countries 3 Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME) of 12 countries

4 Eurasian Economic Space of 5 countries located primarily in northern Eurasia 5 Southern Common Market (Mercosur) of 6 countries in South America

6 Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) that includes all Arab states of the Persian Gulf except for Iraq and Yemen

7 Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Economic Community (AEC) that includes 27 countries

8 The proposed East African Community (EAC) that includes six countries in the African Great Lakes region in eastern Africa

Although regulations may vary, as a general principle, if your organization is planning to export products into any one of these markets and conformity with that country’s health and safety regulations cannot be verifi ed by inspection or test of the product alone, conformity with ISO 9001 may be required to be demonstrated.

Popularity of ISO 9001 certifi cation

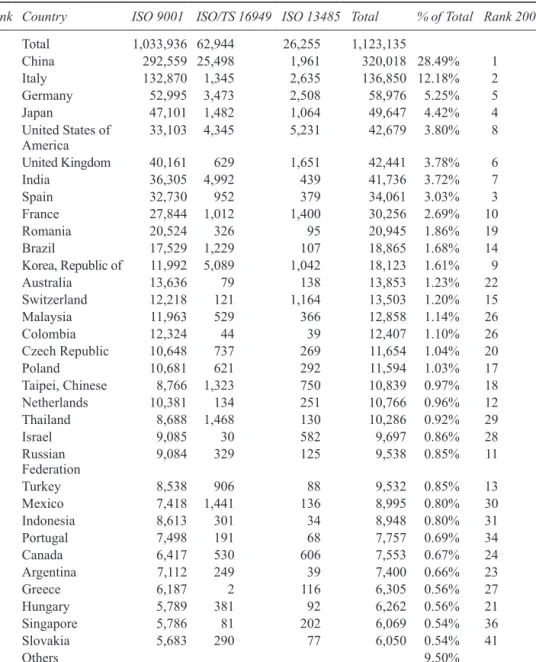

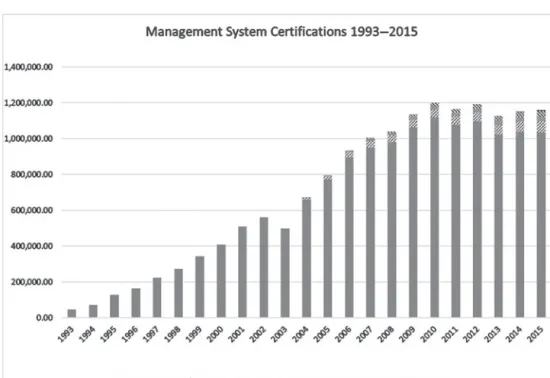

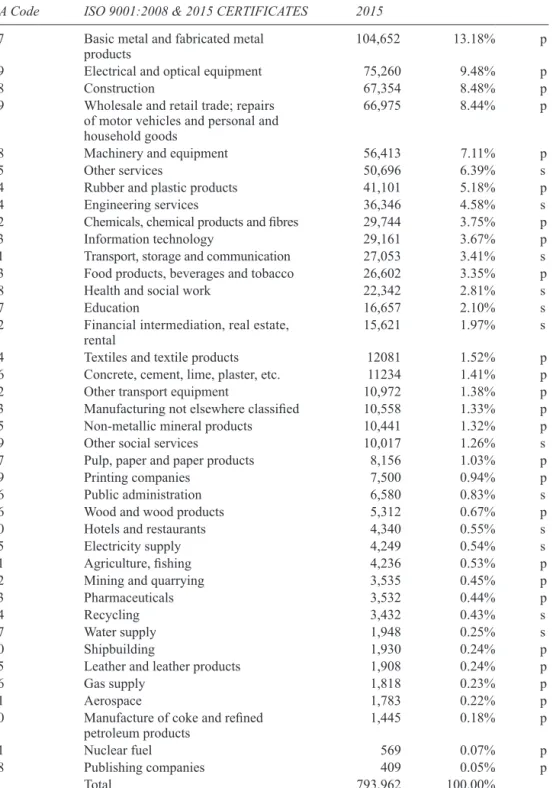

ISO 9001 has gained in popularity since 1987 when the UK led the fi eld holding the high- est number of ISO 9001, 9002 and 9003 certifi cates. Since then certifi cation in the UK has declined from a peak of 66,760 in 2001 to a low of 35,517 by 2008 and rising to 40,161 in 2015, putting the UK into fi fth place. The latest year for which there are published fi gures is 2015 (up to 31 December 2014), when 33 of 195 countries (17%) held 90% of the total number of certifi cates issued, as detailed Table 1.1 .

As quality system standards for automotive and medical devices (ISO/TS 16949 and ISO 13485) include all requirements from ISO 9001, certifi cation to these standards can be added to the numbers of ISO 9001 certifi cates. The numbers only include data from cer- tifi cation bodies that are accredited by members of the International Accreditation Forum (IAF). The data are for numbers of certifi cates issued and not for the number of organiza- tions to which certifi cates are issued, which may be less as some organizations register each location. In the sixth edition of this Handbook, data were used from the 2008 ISO Survey, and comparing the ranking reveals how certifi cations have increased and declined over the intervening period.