SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

BureaaofAmerican EthnologyBulletin196

Anthropological Papers,No. 76

THE GIFT OF CHANGING WOMAN

By KEITH H. BASSO

113

CONTENTS

PAGE

Preface 117

Introduction 119

The WesternApache 119

Cibecue 121

Fieldmethods anddata 122

Apache words 124

Preliminaries 124

Ndeh Guhyaneh 127

Selection ofamedicine

man

128Selection of

Na

ihlesn 130Shitike 132

Na

eilanh 133Preparations 133

The danceground 135

Bigohjital 138

Theday before

Na

ih es 141Gish ih zhaha aldeh 141

The ritualparaphernalia 143

Nilslaihka 146

Bikeh ihl ze' 147

Bitiltih 149

Na

ih es 150Introduction 150

Preparations 152

Phases 153

I. Bihl denilke 153

II. Niztah 154

III. Nizii 166

IV. Gish ihzhaha yindasle dilihlye 156

V. 157

VI. Shanaldihl 158

VII. Banaihldih 158

VIII. Gihx ilke 159

Four"holy" days 159

Na

ih es and"lifeobjectives" 160Old age 161

Physicalstrength 163

Gooddisposition 163

Prosperity 165

Na

ih esand Cibecue 167Glossary ofApacheterms 170

Bibliography 172

115

116 BUREAU OF

AJVIERICANETHNOLOGY

[Bdll. 196ILLUSTRATIONS TEXT FIGURES

PAGE

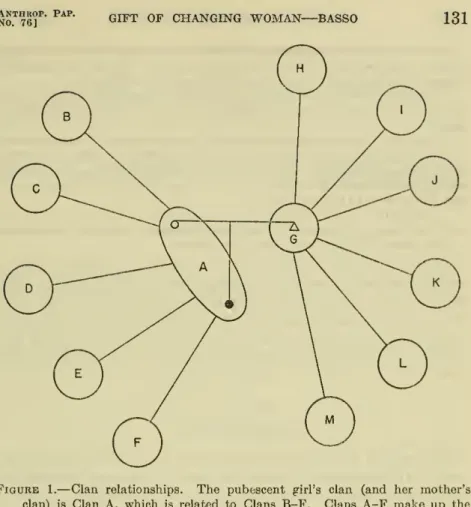

1. Clan relationships 131

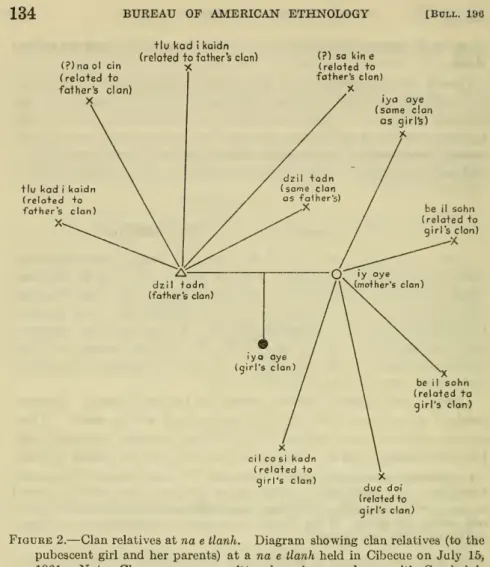

2. Clanrelativesat nae tlanh 134

3.

Na

ih esstructures 1364.

Na

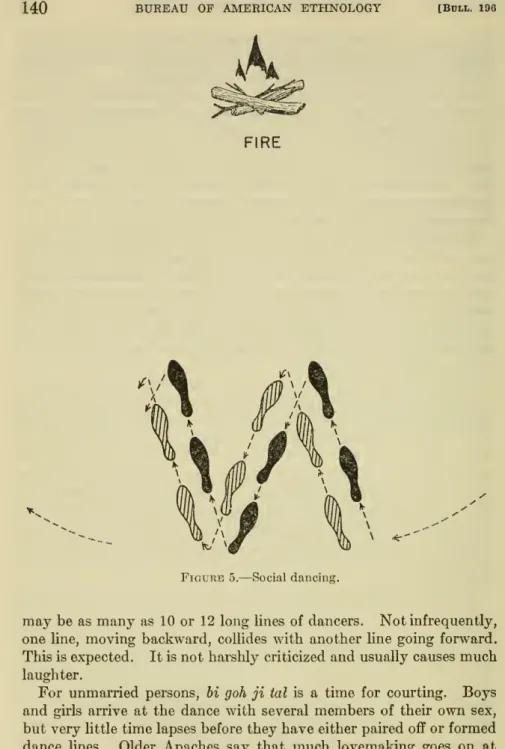

ih es danceground 1375. Socialdancing 140

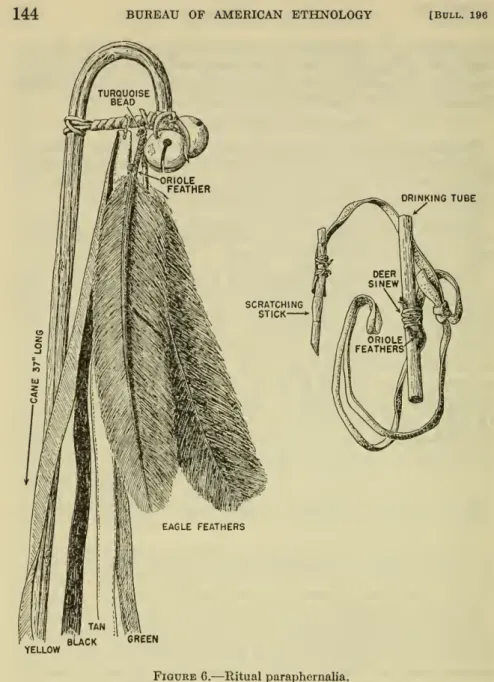

6. Ritual paraphernalia 144

MAP

1. FortApacheReservation 122

PREFACE

The

firstpart of thispaper(pp. 124-159) isatypedescriptionof theWestern Apache

girl's puberty rite orna

ih es as it isperformedby

a group ofApaches

living at Cibecueon

the FortApache

Indian Res- ervation inArizona.Compared

to the wealth of informationwe have

concerning the ceremonial formsand

beliefs of other SouthernAthapascan

tribes,verylittle is available

on

thoseof theWestern

Apache, Infact, onlytwo

trained ethnographershave

published studieson

the subject.Goodwin

(1938) has presented a brief outline of the entireWestern Apache

religious system,and Kaut (Goodwin and

Kaut, 1954) has analyzedanativisticmovement.

Detailed descriptionsofceremonies arecompletelylacking,and

the presentwork

is, Ihope, a steptoward

the elimination of this deficiency.Inthesecondportion (pp.160-170),I

examine

thesymbolic content ofna

ihes inan

effort to illustratewhat

itmeans

toApaches and how

iteducatesthepubescentgirlinthe

ways

of adulthood. I alsodiscusssome

oftheways

inwhich na

ihes functionswith regardto society at large. In this attempt at structural analysis, Imake

use of Kluck- hohn's concepts of adjustiveand

adaptive response.This report

might

neverhave

beenwrittenhad

it not beenfor the interestand

instruction of other people. In particular, Iam

deeply indebtedto thelate Dr.Clyde Kluckhohn, who

firstencouragedme

to do fieldworkamong

theWestern

Apache. Iam

also grateful to Dr.CharlesR.

Kaut who

introducedme

tomany

peopleon

theFortApache

Reservation. In the actual writing, I profited greatlyfrom

the sug- gestions of Dr.Evon

Z. Vogt. Valuable adviceon

the linguistic materialwas

given tome by

Dr. RichardDiebold, Jr. I alsowant

to thankSymme

Bernstein for the timeand

effort she spent preparing theillustrations.For

their cooperation, indulgence,and

kindness Iowe my

greatest debt to the people of Cibecue, especiallyDick and Don

Cooley,Nashley

Tessay(my

interpreter),Teddy

Peaches,and

Nelson, Albert,Dewey, and Rose

Lupe. Also, I gratefullyacknowledgethe assistance ofHelena

Henry, Lillianand Sam

Johnson,Melvin Kane, Dudley

Patterson, George Gregg, ErnestMurphy, Roy Quay,

Pedro Martinez,and

Calvert Tessay.117

THE GIFT OF CHANGING WOMAN

By Keith H. Basso

INTRODUCTION

THE WESTERN APACHE

The

SouthernAthapascans have

been divided into sevenmajor

tribes

on

the basis of territorial, cultui'al,and

linguistic distinctionswhich

they themselves recognized (Goodwin, 1942, pp. 1-13, 1938, pp. 5-10).These

are the Jicarilla, the Lipan, theKiowa-Apache,

theMescalero, the Chiricahua, theNavaho, and

theWestern

Apache.Hoijer (1938, p. 86) categorized these tribes linguistically into

an

easternand

western group.The

latter includes theNavaho,

Chiri- cahua, Mescalero,and Western

Apache; the former iscomposed

of theJicariUa,Lipan,and Kiowa-Apache.

The

definition ofGoodwin

(1935,p.55),which

is themost

compre- hensiveyet devised, designates asWestern Apache

". . . thoseApache

peopleswho have

lived within the present boundaries of the state ofArizona duringhistorictimes, withtheexception oftheChiricahua,Warm

Springs,and

allied Apache,and

a smallband

ofApaches known

astheApaches Mansos, who

lived in thevicinity ofTucson." ^ In 1850,Western Apache

country extended north to Flagstaff, south to Tucson, east to the present city of St. Johns,and

west to theVerde

River.At

this time, the people were divided into five distinct groups, each ranging over itsown

area of landand

refusing to encroachupon

that of its neighbors.^These were

theWhite Mountain

Apache, Cibecue Apache,San

Carlos Apache, SouthernTonto

Apache,and Northern Tonto

Apache.Within

each groupIFor afullerdiscussion ofthis definition,includingmapsshowingthe distributionofWesternApache groups andthose living InArizonawhowerenotWestern Apache,seeGoodwin,1942,pp.1-62. In the middleofthe 19th century, the peoplenowcalledWesternApachewereknown bya varietyofnames (Coyoteros, White MountainApaches,etc.). Goodwinspentmuchtime on thisconfusing problem andin hisAppendix I (ibid.,pp. 571-572) hasprepared alist oftermsby whichthe WesternApache groupswereformerlyknown. Tounderstand which groupsare referredto in the earlyliterature,this tableisindispensable.

•In discussing thesocialdivisionsoftheWestern Apache,Ihave adopted Goodwin's(1942)terminology.

Althoughslightlymisleadingattimes(groupvs. localgroup,etc.)Itisotherwiseextremelyaccurateandthe productof extensive research.

119

120 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Boll. 196were three to five smaller

bands

which, in turn, were subdivided into severallocalgroups, theselatterbeingthe basic unitsupon which

the social organizationand government

of the "WesternApache

were founded.^Ever

since 1871-73,when

the United StatesGovernment began

to interfere with the original balance ofWestern Apache

cultureby

confining thepeople to theFort

Apache and San

Carlos Reservations, the old distinctionsbetween

groupsand bands have

brokendown.

Similarly, the composition of local groups hasbeen seriously altered.

The

matrilineal extended family, however, still preservesmuch

of its old form,and

the basic structureand

function of the individual household haschanged

very little.Before the

coming

of theWhite man,

theWestern Apache

prac- ticed a huntingand

gatheringeconomy. Wild

plant foods such as mescal tubers, acorns, juniper berries, pinon nutsand yucca

"fruit"were

collected all year round,and

biggame

(elk, deer, antelope,and

bear)was hunted

in the late springand

fall. Agriculture (beans, corn,and

squash)was

practiced sparingly.Although

themodern economy

revolvesalmostexclusivelyaround

cattle raising, the peoplestill

farm

smallplots ofcornand

beans,and

continuetogathermescal tubersand

acorns.Hunting

isnow

greatly curtailedby

reservation-imposed

seasons.Reservation life has brought about profound changes in religion.

A

system that once included ceremoniesrelative to warfare, hunting,and moving camp now

centerson

curing ceremoniesand

the girl's pubertyrite. Thisis not to say thatbelief in the nativereligion hasbeen

abandoned.To

the contrary, there is evidence toshow

that, despite strenuous effortsby

missionaries to convertApaches

to Catholicismand

other forms of Christianity, the incidence of native ceremonies hasincreasedoverthepastdecadeorso. Thismay

simply indicate thatmore

people are getting "sick." But,more

likely, itrepresents a trend

toward

the reacceptance of old religious practices which, for reasons not yet clearly understood, were considered in- adequatearound

1920-25when

nativisticmovements swept

across the FortApache and San

Carlos Reservations.*Speakinggenerally,behefin the old rehgionisfound

most commonly among

personsoftoday'sgrandparentalgeneration (aged50-75years).These

peopleremember

the "olddays"

clearlyand

adhere tomany

of the

minute

ritual proscriptions once practicedby

everyone.A

large portionof the parental generation (aged25-50 years) also holds

«Groups,bands,etc.aredescribed In greatdetailby Goodwin(ibid.,pp.13-192). Hisdiscussions are Illustrated by numerousquotationsfrom Informants.

«Foradditionalinformationonthenativisticcultswhich have sprungupsincetheWesternApache came intocontactwith Whites,seeGoodwin,1938,pp.34-37,andGoodwinand Kaut,1954.

No.^T&r'

^^^' ^^^'^

^^ CHANGING WOMAN — BASSO 121

to itsbeliefin the nativereligion.

A

fewindividualshave

joined the church but it is significant that these "converts" attendApache

ceremonies asregularlyas prayermeetings.Today's

young

peoplehave mixed

feelings.Some

scoflF openly atwhat

theycall the "stupid" religious beliefsof their elders; practicallynone embrace White

rehgion.More

aware than theirparents ofthe benefits ofWhite

medical techniques, theyoung

people rarely rely on native medicinemen, who

heal the sickby

supernatural means.CIBECUE

The community

of Cibecue is located near the center of the FortApache

Reservation in east-central Arizona(map

1). It is a small settlement of nearly 700 inhabitantswhose

dwellings are scatteredon

both sides of Cibecue Creek, anarrow

stream originating inmountains

to the north.The

soil is redand

not particularly fertile.Vegetation consists mostly of juniper, pinon,

and

ponderosa pine in the higherareas,and cottonwood

along the creeks.Not

a great deal isknown

about the early history of the Cibecue Apache. Their first unwarlike relations with theWhites came

in 1859,when

they traveled toCamp Grant on

theSan Pedro

River todraw

rations. In 1875, the majority were forced tomove

south toSan

Carlos.Three

yearslater, they returnedto theirhomeland

and, in 1881, engaged in the historic CibecueMassacre

duringwhich

anumber

of troopsbelonging to aregiment of the UnitedStates Sixth Cavalry under thecommand

of GeneralCrook

were killed while attempting to arrest anApache

medicineman. As

far as Ihave

been able to detennine, this encounter ended hostilities with the miHtary.A

largenumber

ofApaches now

regard Cibecue as themost

old- fashioned settlement on the reservation.The

arguments used to supportthis opinion usually includeone ormore

ofthe following:1.

A

majority of the people at Cibecue still live in old-style grass wickiups.Comparativelyfew havebuiltcabins.

2. Cibecue hasmoremedicine

men

presently activethananyothercommunity.3. MoreceremoniesareheldinCibecuethananywhereelse.

Cibecue's conservatism

would seem

to be directly related to itsgeographical isolation.

The

nearestWhite

town.Show Low,

Ariz., is nearly 50 miles away.Few

Indianshave

reason to travel there, and, as a result, Cibecue people rarelycome

into prolonged contact withWhite

society.Two

years ago, I drove a 10-year-oldboy

toShow Low;

itwas

only the second time hehad

been there.122 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 196FORT APACHE RESERVATION

20 40 60 80 100fniles

Map

1.—

FortApacheReservation.FIELD METHODS AND DATA

When

Ibegan

to live in Cibecue Iwas

regarded as something of a curiosity.What

could possiblylure a "rich"White man

to Cibecue, the peoplewanted

toknow. Was

he working for theGovernment?

Why

did hecome

alone, without wife or relatives?Why

did he ask tobe taughtApache

words?And why was

hesowillingtogiveaway

cigarettes?

At

first, the Apache's attitude towardme was

one of moderatelyhostile resignation.As

long as I did nothingtointerrupt theirdaily routine, Iwas

left tomy own

devices.However,

asthepeoplegotusedtomy

presence, theygrew

friendlierand

less aloof. Before long I v/as drivingthem

to other parts of the reservation,and was

visiting theircamps

in Cibecue. QuestionsN^^er*

^^^"

^^^^

^^ CHANGING WOMAN — BASSO 123

about kinship terminologyand

clan organization were answered in a matter-of-fact manner, but inquiries about religion were generally brushed asidewith "I don'tknow"

or "ithas alwaysbeen thatway."

As

thesummer

progressed, Ibegan

to herd cattle with Cibecuecowboys

and, in thisway,made

several close friendswho

laterturned into first-rate informants.InCibecue,I lived in the

home

ofDick

Cooley,who

is partApache

himself,

and

astockman

for the Cibecue cattle district.Mr.

Cooley speaks fluentApache and

isknown and

trustedby

IndiansaU

over the reservation. I benefited greatlyfrom my

association with him.When

I returned to Cibecue in 1961 the peopleseemed

glad to seeme. They

answeredmy

questions willinglyand

wereno

longer reluctanttotalkaboutreligion. I continuedtolivewithMr.

Cooley, offer transportation, and,though

less frequently than during the previous year,work

with the cowboys.To my

surprise, Iwas

able to pickup

the languagemore

rapidlythanbefore and, obviously, this faciUtatedcommunication

withApaches who

spokeno EngHsh.

In addition, Iwas

able to enhst the aid of a close friend as interpreter.My

notebooksbegan

to swell with detailed informationon

a wide variety of subjects.Although

I never paidmy

informants withmoney,

I frequently gavethem

"presents" of cigarettesand

beer.The

dataon which

this paper is based were collected at Cibecue during thesummer months

of 1960and

1961.During

this time, I observed the preparationsand

performance of four girl's pubertyrites. In addition, I

had

57 long interviews (rangingfrom

half an hour to 2 hours) about theceremony

with 16 different informants.All but

two

of these were over 40 years of age.Three

werewomen.

Following the

method

outlinedby Kluckhohn

(1944, p. 10), I usedmy most

trusted informants as a check group againstwhich

to gage the testimonies of others. Fiveindividuals (fourmen and

awoman)

comprised this test group.Of my

57 interviews, 29 were held with them.Of

approximately 170 pages of field notes bearingon

the girl'spuberty rite, I estimate that a little over one-third were written in the presence of informants, the rest being written immediately after interviews

had

concluded. Forty-seven conversations were carried on throughan

interpreter.I

was

able to obtainwhat

information I did because of anumber

of factors.

Two

of these, however, were of particular significanceand

deserve specialmention

here.1. Apaches are more apt to speak candidly and truthfully about the girl's puberty rite than any other ceremony. The reason for this is that it is not concerned with sickness,asubject whichthe peoplefear greatly and arealways reticent tomention.

X

124 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 1962. Becauseof

my

age (21), I wasable toask theolderpeopleto "teach"me

abouttheceremony. In averyrealsensethisapproach wasinkeeping with the Apachepatternofyoung

men

asking eldersforinstructioninthe highermatters ofreligion.APACHE WORDS

Apache words

in thetext are written interms ofthebroad

phonetic transcription indicated below.Phonemic

interpretationawaits further investigation.i=[Il

ih=W

e=[e]

eh=[el

a=la]

ah=[xl

o=[cloh=[o]

u=[v]

uh=[u]

p,t,k=voiceless stops

b,d,g=

voiced stopsx=[1

1=[X]

ay=[ai]

v=

nasalized vowelPRELIMINARIES

At

one point in history, probably notmore

than 70 years ago, almosteveryWestern Apache

girlhad

a puberty ceremony, orna

ih es ('preparing her,' or 'getting her ready').^Today

this isno

longertrue. In Cibecue, the

ceremony

is held onlytwo

or three times a year and, in anumber

of other settlementson

the FortApache

Reservation, it is not performed at all.

Two

reasons for this decline arereadilyapparent. First,as aresult ofinroadsmade on

the tradi- tional religionby

missionaries,some Apaches no

longer believe in the effectiveness ofna

ih es, that it will assure the pubescent girl,among

other things, of long lifeand

prosperity.However,

this attitudeisopposedby many

older persons,notablythoseofthe present gTandparental generation,who

still considerna

ih es an extremely important ceremony,and

onefrom which

the entirecommunity,

«ThroughoutArizona,andInagreatdealofthepopularliterature,naihesisfrequently referredtoas the"sunrisedance,"atermwhich Apaches themselvesusewhenspeakingtoWhites.

No^ tcT'

^^' ^^^^

^^ CHANGING WOMAN —^BASSO 125

as well as the pubescent girl, will benefit.

A

second reason thatna

ih esis heldlessand

less is its prohibitivecost.As

willbeshown

below, the

amount

ofmoney and work

required is staggering,and

this condition

makes

theceremony

impossible formost

people. Infact,

Apaches

say "onlyrich people givena

ih es."The

decision to holdna

ih esis usuallymade

before a girl has herfirstmenses.

When

sheis 11 or 12 years old,her parentsand

grand- parentsdiscuss thepossibilitiesofhaving adance. If, as occasionally happens, parents are hesitant, a grandparent will supply the in- centive tofoUow

the "oldways."One

informantrecalled:I wasn't sureabouthaving a dance.

My

wifewantedto because shehad one whenshewasa girl. Now, somepeople thinkit'sold-fashionedandthemedicinemen

don't havethe power. It costs a lot, too.We

didn't know what to do.Then it came close to when

my

daughter wasto bleed forthe first time, so we had to get going. Thenmy

mother came tomy

camp and said, "I hear you won'tgivemy

granddaughter naihes.Why

don'tyou haveher one? Iam

an oldlady butIam

stillstrong.Na

ih esdid that."We

decided it was goodto have naihes.Another man

said:I wanted

my

daughter to have one [na ih es]. Some people say it doesn'tmean anything, but I think it is good. It sure was good for the old people.

Maybe

theyhadmorepowerthan today.Still anotherinformant, of a differentopinion, related:

Two

years ago,my

daughter had her first [period] and some people said I shouldhave naih es forher. ButIdon't believeinthosesuperstitionssoIsaid no.A

girl's parentswiU

notcontemplatena

ihes unless they canaffordit.

Although

clan relatives relievesome

of theburden

with gifts of foodand money,

the financial expense of theceremony

falls in large parton members

of thegirl's extended family.A

father,who

recentlygave na

ih es for his daughter, said:Me

andmy

wifestartedsavingmoneyabout6monthsbeforeshe[hisdaughter]hadherfirst [period]. Isavedongasand

my

wife didn'tbuy asmany

things at the store [tradingpost].My

brotherand hiswife tried tosave aHttle. So didmy

wife'sparents, but they didn'tsave verymuch.We

didmostofit.When

she had her first we had about $200 saved up, but it wasn't enough and just beforethe dance

my

wife had to borrow another $50 from her brother to buyflourandsugar with. Itwas alongtime'tilwe couldpayhimback.

Relations

between

the girl's familyand

their blood kinmust

be unstrained because, without the contributions of kinsmen, therewould

be toomuch work

foran

extended family, evena largeone, toaccommodate.

If, forany

reason, serious tensions existbetween

them, plans for the dance are postponed until the difl&culties can be resolved. If this is impossible, the idea of holdingna

ih esmay

be completelyabandoned.74T-014—66 9

126 BURKAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[lUiu.. 190An

informantcommented on

thisproblem

in the followingway:

When

Ihave naihes formy

daughter, I liadtroubleat fh-st.A

lotofpeople weremad

atmy

wife because she got (hunkonenight andgot into a fight withmy

brother's wife. Shehit her witha bottleand hadtogoto jailin Whiteriver forCOdays. Theysaid tome:"We

won'thelpyougetreadyfornaih esbecause your wifedrinkstoomuch

and acts crazy." I'.venmy

clan relatives were mad.They said:

"Why

does your wife fight with your brother's wife?He

has been friendly with her. Itis because she drinks all thetime.Maybe

shewould get drunk and figlit with us." I was really scared for a while, because I didn'tknowifanybody wouldhelp us atthe dance. Then

my

wifeapologizedandcut down on drinking, and we got help. But some people werestill nuid, and did nothingfor us.Occasionally, nonrelatives offer to help, particularly

when

the danceground

is being prepared. Itis rare, however, for personswho

are not related in

some way

to one ormore members

of the girl'sextended family to take a largopartin the preliminaries.

One man

said:U(!latives do most ofthe work, but sometimes friends help out. Tliey know

it's goodto help, and they might get somefood for helping.

A

friend of minelet

me

usehispickup [truck]three timestohaulgroceries from Whiteriver.My

wifeborrowed two te tza [baskets] from her friend. Neither ofthesepeople are related to us,but they justwantedto help out.

When

they getthe place[dance ground] r(!ady and have social dancing until midnight, youngmen

come and work during the day. Theygo tothe danceat night. I guess that'swhy

they doit.Another

informantcommented:

People who aren't relatedto thegirl don't work as hard as her relatives. If _.^you help your relativesout, then when you want somethingthey will helpyou.

In

most

instances, noceremony

ofany

kind accompanies a girl's first menstruation.However,

sometimesan

elderly person, often a maternal grandmother, will sprinklehadn

tin ('ycHow powder') in the four cardinal directions, sajnng to the pubescent girl as she doesso: "It is

good

this way.Now you

willhave na

ih es." "If the girl is too shy to tell her parents of her first menstruation, she

may

inform hergrandmother

wlio conveys the news. It some- times luippcns that a girl is not told that she canhave na

ih es until after herfirstperiodhas occurred.When

she has her firstone,theymay

tellheraboutgivingnaihes. Theysayit willmakeherstrongand keepherfrom getting sick andmakeher lead agood

lifeandstayoutof trouble. Sonu:timesthey don'ttell her thatshe hastodance

in frontofall tluipeople, becauseifsheis bashfulshemight not wantthe dance.

But most girls that age havese(ni 7i,a ih cs and know about it. They say no at first becausetheyare bashful. Butthey changetheirminds.

*Iladntinismmlofromcornnnd/orcattailpoUon. ItIsubiquitouslUnilApachoroltglousceremonies, oudIsoften cullud"holy" powder.

N^TCr'

^^^^^^ CHANGING WOMAN — BASSO 127 When,

for one reason or another, a girl decides that she does notwant

tohave

a dance, shemakes

her feelingsknown

and, if she per-sists, plans for

na

ihes are discontinued.The

father ofan

unwilling girl said:My

daughter didn't want a dance. She said she was bashful and that her friends would tease her. Somy

wife talked to her, but she didn't change her mind.My

wifeandmy

wife'sparentsweresuremad.We

neverhadthe dance.Itwouldn't begoodto makeherhavethedanceifshe didn'twantit.

It is not until the girl has herfirst period that actual preparations arebegun.

With

thegirl'sconsent toparticipatewillingly inna

ihes,enough money

tofinance alarge portionofthe expenses,and

amicable relations withrelatives, the girl's parentsembark on

preliminaries.NDEH GUHYANEH

('wisepeople')

Immediately

after a girl's first menstruation, her parents select a group of older persons, called ndehguhyaneh, withwhom

it is decidedwhen and where

the dance will be held and,most

important of all,who

will be the girl'sna

ihl esn ('shemakes

herready,' 'she prepares her'), or sponsor.Ndeh

guhyaiieh usually consist of at least one set of grandparentsand

other close blood kin; but it isby no means uncommon

for nonrelatives, respected for their ageand

familiarity with ceremonialproceedings, tobe chosen. Normally, there arefrom

fiveto eightndeh guhyaneh,the parentsofthe pubescentgirlincluded.

Said one

man:

When

we have na ih es we had eight ndeh guhyaneh. There wasmy

wife's fatherandheroldestbrotherandmy

brother, too.We

alsoaskedPP

[amedicineman

who does not know the songs for na ih es] and his wife to help us.We

asked himbecause heis old and hiswife is averygood lady.

He

has seenlots of na ih es, even though he doesn't do that [particular ceremony]. His wife wouldknowaboutwhoisgoodfornaihlesn.One man,

usually a grandfather of the girl, is appointedhead

ornan

tan (literally 'chief,' but heremeaning

'foreman' or 'boss') of the proceedings; he is second incommand

to the girl's father. Hismain

functions are: (1)To

supervise preparations forthe dance, par- ticularly those concerned with clearing thedanceground and

erecting temporary dwelHngsthere; (2) to actas aspeakerforthe girl'sfamily in offering the role ofna

ihl esn to thewoman nominated by

the ndeh guhyaneh;and

(3) to give a speech beforena

ih es remindingallpresentof the solemnityof the occasion

and

cautioningthem

to be on theirbest behavior.The problem

of selecting agood day on which

to holdna

ih es isnot a pressing one for the ndeh guhyaneh. Regardless of

when

the128 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 196 girlhas herfirstperiod, theceremony

isheldinJulyorAugust, usually the latter. (It is interesting to note that parentswelcome

their daughter's first menstruation in the fall or winter because this givesthem ample

time to saveup enough money

for the dance.)The Apache

givetwo main

reasons for preferring thesummer

months.First, theevenings

and

nights arewarm —

^ideal for the social dancing which accompaniesna

ih es. Second,more

people, notably high school students, will be in Cibecue to attend the dance during thesummer

than atany

other time. Therefore, the ndeh guhyaneh merely decideon

an appropriate weekend,which must

then be ap- provedby

the tribal council at Whiteriver.^One

informant said:I wanted a weekend when there arelots of people.

We

[the ndeh guhyaneh]talkedabout itfora whileandthought theweekend oftherodeoin Cibecuewas good. There would be lots of people there from Whiteriver and Cedar Creek.

Some San Carlos people might come too. Some White cowboys ride in that rodeo andthey comesometimes. I wentto seethe tribalcouncil and they said itwas o.k.tohaveitthen.

Once

a date hasbeen

selected, the task of picking a site atwhich

to hold

na

ih es confronts the ndeh guhyaneh. Necessary requisites includean abundant

source of water close at hand; proximity to a largesupplyofwood; and ample

spaceforthedancearea, thedwellings of thegirl'sclose kin,and

theclosekinofna

ihl esn. Ifthegirl'sown camp

or dwelling place is lacking, a location outside thecommunity

is chosen, usually to the north (where thereis

more wood) and

near Cibecue Creek.One woman, who had

givenna

ih es forher daughter, recalled:Our camp was no good for na ih es. It wasn't big enoughto have a dance, andthere wasn'tflatgroundthere. So wehaditat "wheretheroadcrossesthe creek." That wasa goodplace. There wasn't

many

stones or weedsthereanditwas easytomakeaplace to dance. Trees weresowecould usethemaspart ofthe shadesandtheplaceswekept thetulipay^ and groceries. [Another thing]

was that the cattle were close to that place so it was easy to get them to be butchered. . . .

SELECTION OF A MEDICINE MAN

Another

responsibility of the ndeh guhyaneh is the selection of a medicineman

ordi'yin('onewho

haspower') tosingna

ihes.^ Here, a uniqueproblem

faces the people of Cibecue because there are no medicinemen

left alive in thecommunity who know

the ceremony.Therefore, a medicine

man must

besecuredfrom

elsewhere.»Practicallyalllarge ceremonials,suchasnatt es,areheldon weekends,enabling personswhohold jobs outsideofCibecuetoreturnandattend them. AfavoriteweekendfornaihesisJuly4,whenanall-Indian rodeoIsheld.

»TulipayIsanative liquormadefrcanthefermented pulpofmashedcorn shoots.

'ThereareafewfemaleshamansontheApachereservationstoday,buttheseneversingnaihes

no!'76]^" ^^^^

^^ CHANGING WOMAN — BASSO 129

Na

ih es is performed alone (as opposed to beingcombined

with asecondceremony

callednjanjleesh,meaning

'sheispainted') inonlytwo

other communitieson

the FortApache

Reservation besides Cibecue— Cedar Creek and

Carrizo.The two

medicinemen from Cedar Creek who know na

ih es are thought well of in Cibecue.They

are highlyrespected for their strong power, which, in this case, refers to their ability tomake na

ih es effective.On

the otherhand, there is only one medicineman

in Carrizowho knows

the ceremony, and, for reasonswhich

Iwas

unable to ascertain, he ismuch

less popular. Consequently, for the pastfew

years,na

ih es has been performed in Cibecueby Cedar Creek

medicinemen.

CibecueApaches

are quick to say that theCedar Creek

version ofna

ih es differslittlefrom

theway

theirown

used to be performed.There

are only a fewminor

variationsand

these are attributed to the medicineman's

individual style, rather than to significant regional differences inideology. Said oneman from

Cibecue:They [the Cedar Creek people] do italmost like we do.

When LA

[a Cedar Creek medicineman] comesover hereit'snot hardlyany differentfromtheman

whosanghere. Someofthesongsarealittledifferentbut notmany. Itmeansallthesamething. It's never bothered people here. They knowthat

LA

sure^

has got power. Besides,

LA

was born in Cibecue.He

just learned [the songs foriiaihes]from aCedar Creek medicineman.Once

a medicineman

has been chosenby

the ndeh guhyaneh itremains for the girl's father to visit

him and

askhim

to sing. Thismay

bedone

aslong as amonth

after the girl'sinitial menstruation, but is usually taken care ofmuch

sooner. First, the girl's father acquires certain items to be given to the medicineman.

These include the tail feather ofan

eagle, to the base ofwhich

a turquoiseis attached with deer sinew,

and

a small container of holy powder.With

theseinhand,and enough money

topay

themedicineman's

fee, the fathersetsout early inthe morning.He must

arriveat themedi- cineman's camp

before sum-ise.Igottherereal earlyandwaitedin

my

pickupuntilthe suncameup. Ididn't see anything so I just sat there. Then his wife came out of her wickiup and threwsome water away she had in a cooking pot. She sawthe truck but she didn't say anything and went back inside. Then the medicineman

came out and went behind the wickiuptomake water.When

hecame backI gotoutofmy

truckand wenttowhere he was. Itook allthestuffwithme

that I would givehim.He

had sung naih es formy

daughter 4years ago, so Ialready knew him andhow much

hewouldcharge.When

Igot towherehewassittinghe held outhisleft hand,inside[palm] up.He

helditlikethisandIopenedthejarand took outsomepowder. Imadea crosswithit onhishandinthefourdirections.ThenIput thefeatheron hishandwith thebluestone[turquoise]wherethecross

cametogether. Thenafter Ididthishe took thefeatherandputitin hispocket.

ThenItook out $50from

my

walletandputit in bishand. ThenIsaid, "Will yousingnaih es formy

daughter?"He

said,"Yes." ThenItoldhim what day130 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Boll. 196 it was [to beheld]and hesaidthat was good andthathe wouldbethere 2 days early, so to have everythingready then. Then he put the $50 in his pocket.I went homeafter thatand told ndehguhyaneh what hesaid. They wereglad hesaidyesand wouldsing.

SELECTION OF NA IHL ESN

Ndeh

guhyaneh also choose awoman

to be the pubescent girl's 'sponsor'orna

ihlesn.The most

important criterion for ana

ihl esnis thatshe belong to a clan

which

is not related to the girl's clan or to thegirl's father's clan, or toany

clan towhich

these are related.In order tounderstand this proscription, one

must know

something of the relationshipsbetween

clans.A

clan ismade up

of personswho

consider themselves related to eachother through thematernalUne

butwho

areunable to trace the specificgenealogical tiesinvolvedin theserelationships. In thesame way,

every clan hasassumed

matrilineal relationships with certain other clans. Together, these related clans comprisewhat Goodwin

(1942) calls a "clan set." Restating the

above

proscription in these terms, ana

ihl esnmust come from

a clanwhich

is notrelated toany

clan in the girl's clan set or to

any

clan in the girl's father's clanset (fig. 1).The

sociological importance of this limitation willbecome

apparentlater on, but for the time being it is instructive to seehow

it applies in terms of actual

Western Apache

clans.On August

20, 1961,na

ih eswas

held forW.G. whose

clan is iya aiye {'iya ai people').^*' /?/aaiyeisrelatedtotua

gaidn ('white water people'), tudilxili ('blackwater people'),tena

dolja ge {'tena

dolja ge people'), tset ean

('rock-jutting-into-water people'),nd

nde zn ('tall people'), ducdo e ('fly-infested-soup people'), tc ilda ditluge ('bushes- sloping-up-growing-thickly people'), iyahadjin ('mesquites-extending- out-darklypeople'),?iadabilna ditin ('mescal-with-road-acrosspeople')and

sai e digaidn (line-of-white-sand-joining people'). Thus,na

ihl esn could not belong toany

of these clans, because all ofthem

aremembers

of the girl's clan set. Similarly,na

ihl esn could not be related toany

of the clanswhich made up W.G.'s

father's clan set,which

includedna

wadesgijn ('between-two-hills people'), ti sle dnt ind

('cottonwoods joiningpeople'), tcilndiyenadn

aiye ('walnut trees people'), k aintcidn

('reddenedwillows people'), te go tsudn ('yellow- streak-running-out-from-the-water people'), t i skadn

('cottonwood standingpeople'),sagna

[meaning unclear],h kaye [meaning unclear],na

gonan

('bridge across people'), k isde stcina

ditin ('trail-through- horizontally-red-alders people'), gad oahn

('juniper-standing-alone people'), teatcidn

('red-rock-strata people'). Thus, includingall the clans in these 2 clan sets, there were 26 clansfrom which na

ihl esnw ClannamesareherewrittenInaccordancewithGoodwin's(1942)orthographicsystem.

Anthrop. pap.

No. 76] GIFT

OF CHANGING WOMAN — BASSO 131

Figure 1.

—

Clan relationships. The pubescent girl's clan (and her mother's clan) is Clan A, which is related to Clans B-F. ClansA-F

make up thegirl's clan set. The girl's father's clan is Clan

G

which isrelated to ClansH-M.

ClansG-M

makeuphisclanset.Na

ihlesnmustcomefroma clan which isnotrelatedto anyof theclansinthesetwo clansets.could not come.

The woman

selectedwas from

ci tc iltco sika dn

(*Gambel's-oak-standing people').

Once

the ndeh guhyanehhave

singled out all thewomen

in thecommunity who

are eligible (by clan) for the position ofna

ihl esn,they

make

their final decisionon

the basis of characterand

wealth.Apaches

saythat characteris themost

important,butIrecallonecasewhere

itwas

freely admitted that thena

ihl esnwas

a"bad

person."She

had

beenchosen, Iwas

told,becauseshewas

richenough

toafford the expenses entailed. In all other instances, however, thena

ihl esnwas

awoman

of highly esteemed reputation.The

following state-ments

indicate the qualitieson which

such reputations arecommonly

based.

132 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 196Na

ihlesnmustbe agoodperson. She mustbe strongandworkhardandnever belazy. Alsosheshouldn'tdrink toomuch

or act crazy. Sheshouldn'tsaymeanthings thatwillmakeotherpeople

mad

atherandfightwithher.. . . must be friendly with people and not make them fight with her. She should bepretty oldandwiseaboutthings. Allthe timeshe says nicethings to people.

, .. It'sgoodifshehadana ih eswhenshewas agirlherself. Thatwaysheis wiseandknows aboutthethingsinna ih esanditmakes herstrongandhealthy and easytogetalong with. Ifshehad na ih esshewon't actcrazyor drink too

much

or getin trouble orbother people. That'swhy

itis best to get someone who had naih es tobe na ihl esn.^^. . .should not besickvery

much

but strongsoshe canworkhardandmakea good cleancamp. It's goodifshe haslotsof children. Partofna ih esissothegirlhaschildreneasilyandwon'tdie[in childbirth].

Ih' tsos hahihl tza ('eagle feather, it is given') is the

Apache

phrase used todescribetheprocedureofasking awoman

tobena

ihl esn.The nan

tan goes to thewoman's camp

before sunriseand

asks her to filltherole. Ifshe

and

herhusband (who

usuallymakes

thefinaldecision) accept, thenan

tan givesthem an

eagle feather, turquoise,and

holy powder.Then

he invitesthem

tocome

to thecamp

of the girl's parents—

to drink tulipayand

discuss details.SHI

TIKE

('my

good

friend')The

meeting after ih' tsos ha hihl tza is an extremely important event. It inaugurates a formal relationshipbetween

the girl, her parents,and na

ihl esnand

herhusband —a relationship which is

binding forlife,

and

onewhich

ismarked by

the adoption ofhitherto unused terms of address. Henceforth, the girland

her parents callna

ihl esnand

herhusband by

theterm

shi ti ke,and

vice versa.By

extension, shitikemeans

'all thatIhave

belongs toyou,'and

this principle constitutes the basis of anew

set of reciprocal obligationsincumbent on

the persons involved. In fine, the shi ti ke relation- shipmeans

that theymust

help each other forwhatever

reasonand whenever

the needmay

arise.The

significance of thisbond

lies inthe fact thatit is almost asdemanding

asan

actualblood relation- ship. Said one informant:When

youcallsomeoneshi tike you alwayshelp him out. It's good to have someonelikethatbecause he will help you.When my

baby girldiedlast year, thewoman

whowasmy

wife'snaihlesnsurehelpedusout. She gaveusfoodand madeherbrotherkillabeeffor us.My

wife gives her presentsnowandthentoo.LastyearI think

my

wifegave hersomeclothfora dress. Whenever youget in trouble it's good tohave someonelike that. There was aman

who had a sonwho

gotputinjailin Whiteriveron afornication charge. Thewoman

whowas»

My

datashowthatItIsnotImperativefornaihlesn tohave had naih es herself. However,adefinite preferenceIsexpressedforwomen whohave.Na^Ter*

^^^' ^^^^

^^ CHANGING WOMAN — BASSO 133

naihlesnforthatman's daughter gave himsomemoneytohelpbailtheboy out ofjail.Once

awoman

has agreed to bena

ihlesn, she preparesforna

ihes inmuch

thesame way

as the girl's parents, relying heavilyon

the support of close kin. Sincena

ihl esn need not concern herself with the preparation of the dance ground, hermajor

task is to procureenough

food to feed her relatives during the ceremonial proceedings,and

to give thegirl's relativesalarge feaston

theday

beforena

ih es.NA E TLANH

('have drinking,' or 'goes before drinking')

About

amonth

prior tona

ih es, the gu-l's family, also concerned aboutan

adequate food supply, holdna

e tlanh. Thisis an informal affair atwhich

the girl's family presents clan relatives (and relatives of related clans) with tulipay, in returnforwhich

the latter promise to contributemeat

or groceries (fig. 2).A

clanmember

need not state preciselywhat

he will contribute, or evenhow much,

but it isunderstood that in accepting the

tuHpay

he obligates himself to reciprocate with afairly substantialgift.Usually,

na

e tlanh is held atmidday

at the girl'scamp.

Inside a shade,^^ gallon cans filled with tulipay are set out in rows.When

enough

relativeshave

arrived, the girl's father standsup and

starts the proceedings with a short speech, an example of which follows:I appreciate your coming here at this time. 1 asked you all to come over for drinks soyou would helpusoutbybuying groceries.

You

were not forced tocome,youwereinvited.You

cameofyourownaccord,becauseyou wantedto help out in the dance. It has always been done this way—

helping each otheroutforthe dance,werelatives.

After this, the tulipay is distributed,

and

the rest of the afternoonis spent drinkingit

and

talking about the forthcoming dance.^^Thus, having enlisted a medicine

man,

appointed ana

ihl esn,inaugurated the shi ti ke relationship,

and

assured themselves of the support of relatives, the girl's family turnsits attention to preparing thedance ground.PREPARATIONS

Apaches

attach a great deal of importance to ceremonial prep- arations,and

negligence in carryingthem

out is sternly rebuked.To

a large extent, the effectiveness of a ritual is thought to be de- pendenton

its being flawlesslyperformed, in precise coincidence withitsestabUshedpattern.

Anything which

disturbs oralters thispattern1^Shades,inwhichthewomendo mostoftheirwork,arelarperectangular structures,madefromcedar postsand cottonwoodboughs. TheycloselyresembleSpanish ramadas.

**NaetlanhIsa wonderfulexcuseforthementogetdrunk,and they almost alwaystakeadvantageofIt,

134 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 196i?)r\aol cin (related to father's clan)

X

tlu kadikaidn

(relatedtofather's clan) (?) sokine (related to father's clan)

lya aye (same clan

as girl's)

X

tlukadikaid (reloted to fath er's clan

X

be ilsohn (related to

girl'sclan)

X

be iI sohn (relatedto girl's clan)

ciICOsi kadn

(related to

girl's clan) X

due doi (relatedto girl's clan)

Figure2.

—

Clanrelatives atnaetlanh. Diagram showing clanrelatives (to the pubescentgirl and herparents) at a na eilanhheld in Cibecue on July 15, 1961. Note: Clan names are written here in accordance with (jroodwin's (1942)orthographic system.is inauspicious

and

feared; it is taken as a sign that something isout of order.

For

example, if, as sometimeshappens

at cm-ing ceremonies, there is notenough

food to go around, those presentbecome

nervous."Something

is wrong," they say, "there should be food." It is important to view the elaborate preparationswhich na

ih esand

other ceremonies entail as theApaches

do—

as pre-cautions taken against the occurrence of incidents, such as the one

mentioned

above,which

injectan unexpectedand unwelcome

element of disorder into aceremony

and, in so doing, reduce the possibilities ofits success.One man

said:Everything should be ready before it starts.

You

shouldn't have to do any workwhile<