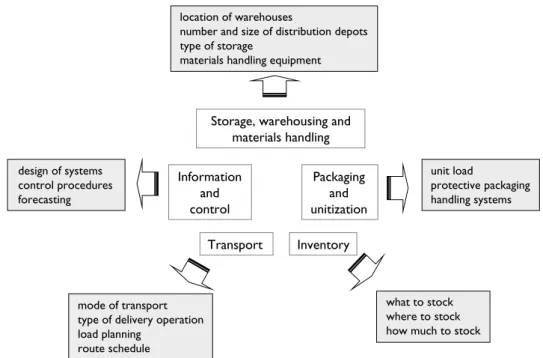

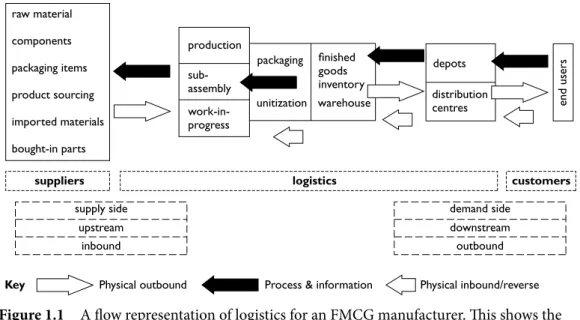

Introduction 367; Relative importance of the main modes of freight transport 368; Selection method 370; Operational Factors 371;. This shows the main components, the main flows and some of the different logistics terminologies. 5 1.2 The main components of distribution and logistics, shows some of the associated.

List of tabLes

PrefaCe

The next chapter focuses on one of the main aspects of this planning framework – logistics process planning. The last part of the book, Part 6, deals with many aspects related to the operational management of logistics and distribution.

THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

Concepts of logistics

Logistics is the management of the flow of goods and services between the point of origin and the point of consumption to meet customer requirements. This shows the key components, the main flows and some different logistic terms.

Historical perspective

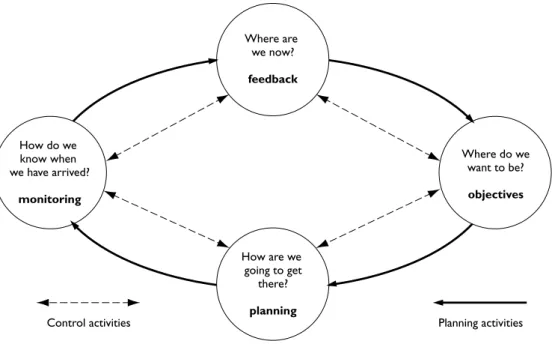

All these functions and sub-functions must be planned in a systematic way, both in terms of their own local environment and of the wider scope of the distribution system as a whole. The different ways to answer these questions and make these decisions are addressed in the chapters of this book as attention is paid to the planning and operation of the logistics and supply chain function.

1950s and early 1960s

Additionally, total system interconnections and constraints on appropriate costs and service levels will be discussed.

1960s and early 1970s

One of the major changes has been the recognition by some companies that distribution must be integrated into the functional management structure of the organization. There has been a reduction in the power of manufacturers and suppliers and a marked increase in major retailers.

Late 1980s and early 1990s

In the 1980s, fairly rapid cost increases and the clearer definition of real distribution costs contributed to a marked increase in the professionalism of distribution. These measures included centralized distribution, severe reductions in inventory, and the use of the computer to provide improved information and control.

2010 and beyond

For example, manufacturers and retailers must work together in partnership to help create a logistics pipeline that enables an efficient and effective flow of the right products to the final customer. This led to the development of many new ideas for improvement, specifically recognized in the redefinition of business objectives and the redesign of entire systems.

Logistics and supply chain were finally recognized as an area that was key to the overall success of the business. Thus, the role and importance of logistics continued to be recognized as a key opportunity for business improvement.

Importance in the economy

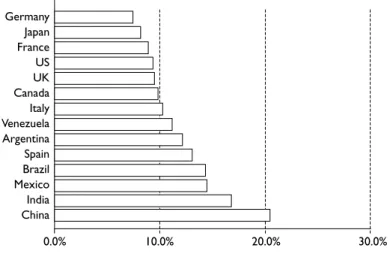

A study in the UK indicated that around 30 percent of the workforce is involved in work related to logistics. In the UK, the records go back about 30 years, when logistics costs were around 18 to 20 percent.

Importance of key components

A helpful discussion paper presented at the International Transport Forum (2012) provides some specific figures for measuring logistics costs and performance at a national level for certain individual countries and can be used for further information.

Importance in industry

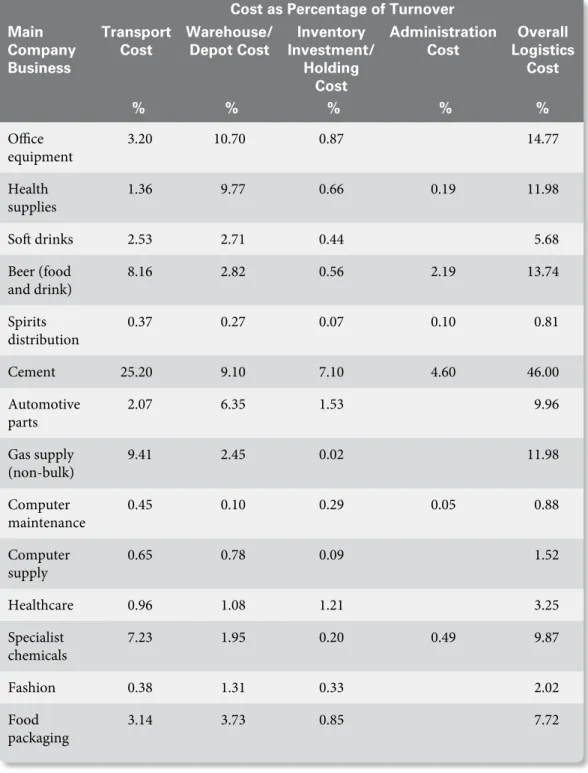

Spirits (whiskey, gin, etc.) are very high value products, so the relative logistics costs appear very low. Small companies tend to have proportionately higher logistics costs than large companies (about 10 per cent of sales costs versus about 5 per cent).

Logistics and supply chain structure

The importance of this distribution or logistics cost for the final cost of the product has already been highlighted. As already noted, this can vary according to the sophistication of the distribution system used and the intrinsic value of the product itself.

One idea that has been put forward in recent years is that these different elements of logistics a. This is a more positive view of logistics and is a useful way to assess the real contribution and importance of logistics and distribution services.

Within logistics components: this refers to the deviations that occur within single functions (eg warehouses). These types of considerations are therefore at the heart of the total logistics concept.

Planning for logistics

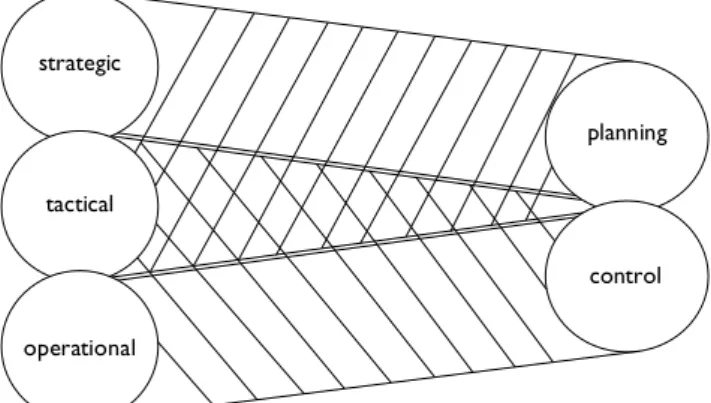

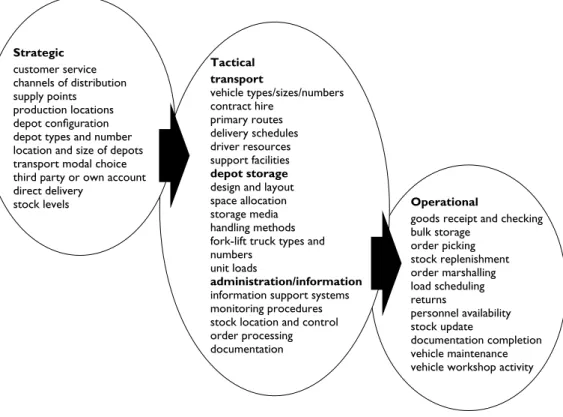

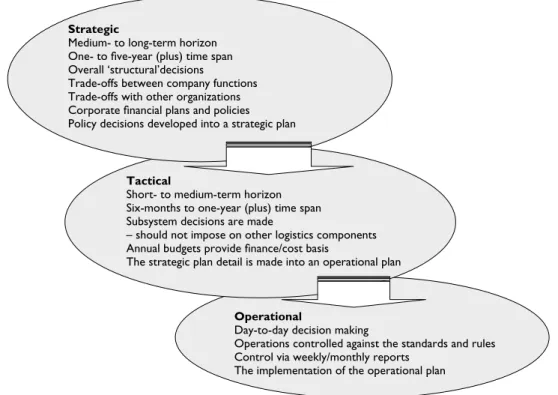

Some of the most important aspects and differences between the three time horizons are summarized in Figure 2.3. It is helpful to be aware of the planning horizon and its implications for any major decision being made.

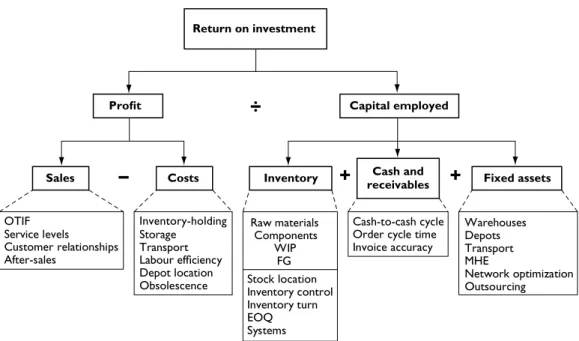

There are many different ways in which logistics can have both a positive and a negative impact on ROI. Finally, there are many fixed assets to be found in logistics operations: warehouses, depots, transport and material handling equipment.

From this it is perhaps clear that there is a direct conflict between globalization and the move towards rapid response, just-in-time operations that are being demanded by many companies. In companies moving to the just-in-time philosophy there is a desire to reduce production time and eliminate unnecessary stock and waste within their operations.

In global companies there is a tendency to see increased order lead times and increased inventory levels due to the distances involved and the complexity of logistics.

Direct product profitability (DPP)

Materials requirements planning (MRP) and distribution requirements planning (DRP)

Just-in-time (JIT)

For example, it can lead to more transport flows due to the need for smaller but more frequent deliveries of goods to the customer.

Competitive advantage through logistics

There are a number of JIT techniques that are generally used to a greater or lesser extent by large companies that have adopted the JIT philosophy, and these are discussed in Chapter 12. Leading companies segment their supply chains based on service and cost needs. customers.” This important point is discussed in more detail in Chapter 8.

Logistics and supply chain management

The vast majority of companies consider customer service to be an important aspect of their business. It is therefore essential for any company or organization to have a clear definition of customer service and to have specific and recognized customer service measures.

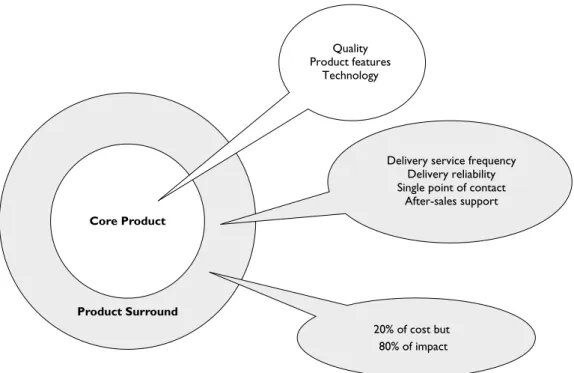

One way to think of customer service is to distinguish between the core product itself and the service elements associated with the product. This definition can be extended to what could be considered the seven 'rights' of customer service.

These are the right quantity, price, product, customer, time, place and condition; and the concept of using these for customer service can be seen in figure 3.2. Pre-transaction elements: these are customer service factors that occur before the actual transaction takes place.

Basic service model

Extended service model

However, it is also important to be able to identify why any such service interruption occurred, and the various reasons can be identified by measuring the other service gaps that appear in Figure 3.5. This gap can typically be caused because the provider and the customer measure service in a different way.

Developing a customer service policy

It is highly unlikely that a universal level of customer service will be suitable for all customers. It should be noted that there are a variety of types of customer service studies that can be used.

Levels of customer service

These should be based on the key elements identified in the customer service packages being developed. Some large companies conduct regular customer service surveys designed to identify such changes in service requirements.

Measuring customer service

It should also be noted that an increase in service from, say, 95 to 97 percent may have little or no noticeable impact on the customer's perception of the service provided, even if it is a costly improvement. The average reported performance for product availability was 93 percent for orders, 95 percent for lines, and 95 percent for cases.

Two conceptual models of customer service were discussed and the need for an appropriate customer service policy was highlighted. This chapter discusses some of the key requirements for successful customer service in logistics.

Physical distribution channel types and structures

Channel alternatives: manufacturer-to-retail

Products are transported by large vehicles along the line to locations where they are stored and then divided into individual orders that are delivered to retail stores on the supplier's retail delivery vehicles. This channel is very similar to the previous physical distribution channel in that these companies provide the "expert".

Channel alternatives: direct deliveries

This is a relatively rare type of channel and can sometimes be a trading channel and not a physical distribution channel. Initially, the physical distribution channels were comparable to those of mail order companies: by post and parcel delivery service.

Channel alternatives: different structures

However, the move to internet shopping for groceries has led to the introduction of additional specialist distribution operations for home delivery. See Chapter 11, Multichannel Fulfillment, for a more detailed discussion of the implications for distribution channels that have resulted from developments in home delivery.

Channel selection

Channel objectives

Again, a certain level of service needs to be established, measured and maintained from both the supplier's and the customer's perspective. As always, the price is very important as it is reflected in the final price of the product.

Channel characteristics

The importance of the product itself in determining channel choice should not be underestimated. This is because the product may impose limits on the number of channels that can be considered.

Company resources

It may well be that consumers' preference for a wide selection necessitates that the same stores are delivered. This may well be the main area of competitive advantage, especially for those products where it is very difficult to differentiate on quality and price.

Designing a channel structure

Typical decisions are whether to sell the product together with these similar products, or whether to try different, exclusive outlets for the product to avoid competition and the risk of substitution. It is essential that channel selection is made with a view to ensuring that the level of service that can be provided is as good as or better than that provided by key competitors.

Third party or own account?

In a European context, data from the Datamonitor (2012) study provide an additional breakdown of outsourcing spending, this time in major European countries. Outsourcing has become such an important factor in logistics that in some European countries it accounts for approximately 50 percent of total logistics spending.

Opportunities for outsourcing

Channel Selection: The objectives of good channel selection were discussed, taking into account the relative market, channel, and competitive characteristics, as well as the firm's available resources. Outsourcing: The question of doing business for own account or outsourcing was presented and the meaning and development of outsourcing was discussed.

In a recent survey of the top challenges driving the supply chain agenda, cost and service issues were two of the top three challenges. Demand variability was also considered very important, along with supply chain visibility, inventory management, and economic and financial volatility – the latter a note on our times.

Recent rapid changes and developments in logistics thinking and logistics information technology have also contributed to another issue that has a significant impact on logistics – that is the problem of the limited availability of suitable management and labour. In the past few years, there have been a number of unpredictable and unexpected events such as natural disasters, terrorism, corporate failures and industrial disputes that have led to, among other things, serious disruptions in the supply chain and logistics activities.

Manufacturing and supply

Emphasis is placed on the need for companies to work together across the supply chain to meet customer demands and be flexible in the way they are organized for production and distribution. Replenishment at the various levels of the supply chain is driven by actual sales data collected at the customer interface via EPOS (electronic point of sale) systems.

Logistics and distribution

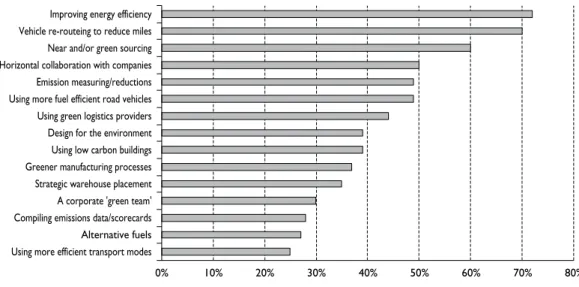

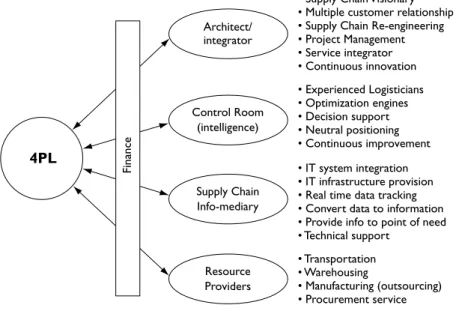

An interesting measure has been the extent and speed of recognition of the importance of distribution, logistics and supply chain. The main thrust is to outsource the overall planning and bring the complete supply chain operation within the purview of the 4PL.

A reduction in DC stock; this has been undertaken to promote cost savings through lower inventory levels in the supply chain. This has been achieved through the use of a number of information technology advancements, most notably Electronic POS Systems (EPOS), which provide a much more accurate and timely indication of the need for restocking at store level.

One very recent example of the growing importance of customer service has been the move to develop an alternative approach to the supply chain by creating what is known as Demand Chain Management (DCM). Finally, it is the connection of the two concepts of supply chain management (SCM) with customer relationship management (CRM) or connecting logistics directly with marketing.

Planning for logistics

Planning framework for logistics

Pressures for change

In this way, the probability of the sub-optimization of logistics activities can be avoided. The quantitative modeling of logistics requirements as a second phase of strategic business planning is an important aspect of this.

Typically, the brewing of beer has been considered the key feature of the industry, and the brewing industry has a strong tradition to back it up. There are different parts of the supply chain that can be influential and necessitate the development of a completely different type of business environment.

Logistics design strategy

It is inappropriate to concentrate on someone without understanding and taking into account the influence of the others. Any of the design factors can play the most dominant role for a specific company.

Product characteristics

Each of these different logistics design factors must be planned in conjunction with the others. Although Figure 6.4 has process design as the first logistics design factor, this does not mean that it is necessarily the first to be considered when conducting a strategic study.

Volume to weight ratio

Thus, total distribution costs tend to be higher for high-volume products than for high-weight products. It can be seen that the total cost of moving and storage tends to increase as the volume to weight ratio increases.

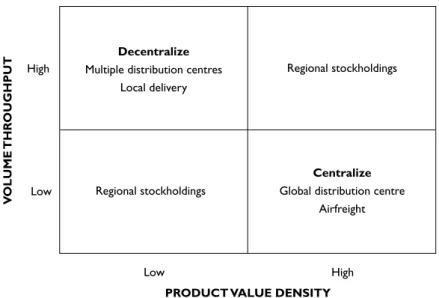

Value to weight ratio

These products use a lot of space and are costly to both transport and store because most companies measure their logistics costs based on weight (cost per ton) rather than volume (cost per cubic meter). In Europe, for example, drag strip trailer outfits are often used to increase vehicle capacity and reduce the transportation costs of moving high-volume products.

Substitutability

High-risk products

There are significant implications for the choice of distribution system for many products like these. There are many and different product characteristics that can pose important requirements and limitations for all types of logistics operations.

Some products have fixed time or seasonal deadlines: daily newspapers have a very limited shelf life, which requires early morning delivery and does not allow for delivery delays; fashion products often have a specific season; agrochemicals such as fertilizers and insecticides have specific time periods for use; there are classic seasonal examples of limited-time Easter eggs and Christmas crackers. For operations where many products are at different stages of the product life cycle, this may not be critical.

Packaging

There is a clear requirement to consider the product life cycle when planning for logistics. A different emphasis should be placed on certain aspects of the logistics system according to the stage of a product's life.

Some of the main product characteristics that should be taken into account in logistics planning were also taken into account. As discussed in Chapter 6, one of the key elements of logistics planning is planning the appropriate logistics processes.

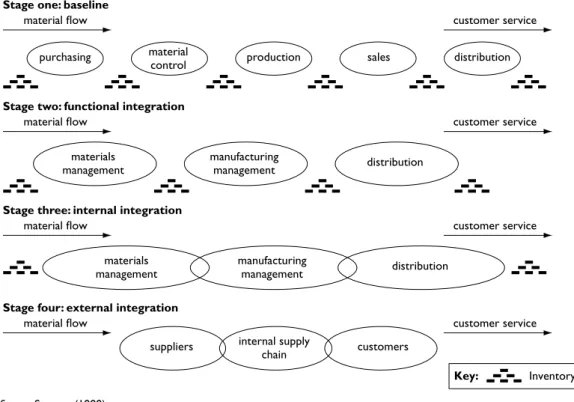

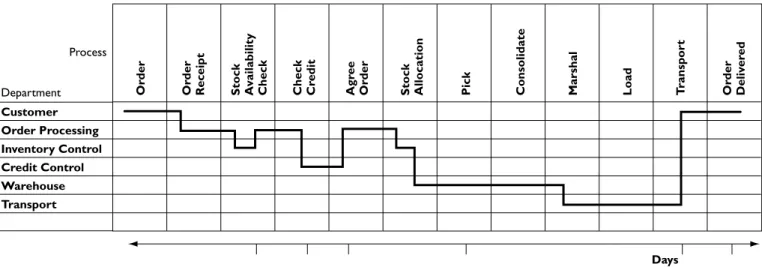

This chapter discusses the importance of logistics processes and the need to move from functional to cross-functional process development. Some of the most important logistics processes are described and the 'process triangle' is introduced as a way of categorizing the different processes.

Functional process problems

The goal of any supply chain is to ensure that cross-company and cross-supply-chain activities are aimed at achieving customer satisfaction for the end user. They must be able to bridge internal functions and company boundaries to provide the type and level of customer service required.

Cross-functional process problems

Properly designed processes must be customer-oriented, that is to say, they must aim specifically at satisfying the customers' requirements and expectations. Finally, they should be time-based, reflecting the importance of time as a key element in the logistics offer.

Logistics process types and categories

Second, it is very difficult to pinpoint the source of the problem – not least because of the associated culture of 'blaming' that often exists between functions, so that one traditionally blames the other regardless of the actual issues. They should also be cross-functional, or where possible they should be supply chain oriented, in that they cross not only business functions, but also the boundary between companies.

Key logistics processes

The goal is to link product development with logistical requirements so that all secondary developments (which are usually many) can be identified and redesigned in the shortest possible time. This is another example of the need to develop processes specifically designed to perform a specific task.

Process categorization

Basic processes: those processes that are not really recognized as essential for a company, but are nevertheless a prerequisite. Benchmark processes: those processes that are considered important to the customer and must be of at least an acceptable standard even to begin to compete satisfactorily in a given market.

It is therefore useful to understand some of the main methods of distinguishing between the various factors that are fundamental to most logistics operations. In addition, it may be possible to identify certain parts of the process that are completely redundant.

It is helpful to put together a dedicated team to take on this and the remaining stages of the process redevelopment. This is useful because standard shapes are used to represent different types of activity (storage, motion, action, etc.), and the importance of flows can be emphasized in terms of the number of moves along a flow.

Product segmentation

Stolen goods: certain goods may be the target of opportunistic or planned robberies and therefore require greater security. For example, low-value goods can be held in multiple locations close to customers, while high-value goods can be centralized in order to reduce safety stocks (as explained in Chapter 13).

Demand and supply segmentation

Within this segmentation framework, lean supply chain principles can be applied where predictable demand exists. Under these circumstances, supply may be adjusted to meet rapidly changing market demands, and inventories may again be low.

Marketing segmentation

Innovative: this tends to be where the customer is constantly looking for new developments and ideas from suppliers. The latter must therefore be innovative in terms of supply chain solutions and fully flexible in their response.

Combined segmentation frameworks

However, the demands of fashion-conscious buyers (i.e., those looking for the latest fashions as seen on the catwalks or in fashion magazines) must be met in a much more flexible way – for example, using rapid design and production techniques, local suppliers and cross-docking via the distribution network directly to the stores. It is a common behavior when dealing with mature products whose demand is fairly predictable and is often associated with a supply chain design that uses continuous replenishment principles.

The question of the number, size and location of facilities in a company's distribution system is a complex one. The understanding of the importance of logistics for most companies, and the need to cut costs and improve efficiency, has provided sufficient impetus for a number of companies to review their logistics and distribution structure with a particular emphasis on use and location of DCs and warehouses .

This will usually consist of supplying a number of DCs on a regional or area basis, and using large primary (line transport) vehicles to service them, with smaller vehicles delivering the orders to various customers on each ride delivery For certain operations, even these simple ratios will naturally vary due to the need for very high levels of customer service or the very high value of products.

Cost relationships

Storage and warehousing costs

The change is likely to be from a single large site to two medium sized sites. Thus, as the number of DCs in a distribution network increases, the total storage cost (DC) will also increase.

Road transport costs

Inventory holding costs

This is the finance charge, which is either the current cost of capital for a business or the opportunity cost of tying up capital that could otherwise provide a return if invested elsewhere. These first three costs, when taken together and measured against the number of DCs in a system, can be represented as shown in Figure 9.5.

Information system costs

Storage costs – these costs are considered here separately as storage and warehousing costs (see earlier in this section).

Total logistics costs

For example, just for a single DC, there is a large cost of local distribution to add to the much smaller costs of major shipping, inventory, storage and system costs. The results, in practice, will depend on a number of factors – type of product, geographic area of demand, demographics and population density, level of service required, etc.

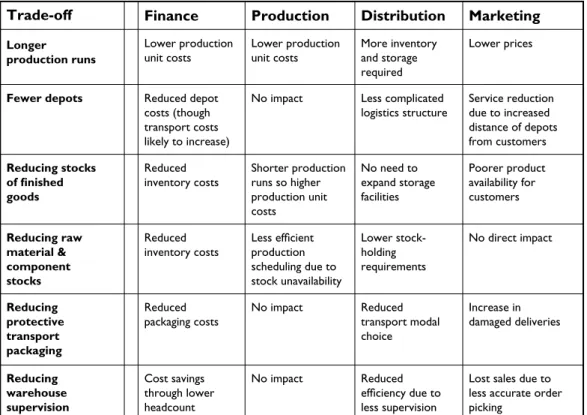

Trade-off analysis

These will vary depending on the type of manufacturing process or system used and the type of product being manufactured. These costs vary depending on the type of storage and handling systems used, along with volume and throughput at the site.

These can occur due to inadequate customer service and are very important in the context of the DC's proximity to the customer, along with reliability and speed of service. They have an essential relationship with the DC network in terms of the number of stock holding points and the stock holding hierarchy by DC type.

Once a suitable logistics strategy has been identified, it is essential to undertake the dual process of evaluating this strategy against the preferred business strategy and ensuring that every practical consideration has been taken into account. The following sections of the chapter include a brief discussion of the key steps depicted in Figure 9.9.

External factors

Internal factors

Establish current position

The complex nature of data requirements is illustrated in the (relatively simple!) network diagram in Figure 9.10, where examples of some typical major flows and costs are given. The network consists of five production points and shows the flow of products through finished product warehouses and distribution centers to retail stores.

Data collection for costs and product flow

This can be essential to help understand the implications of the data in terms of demand for different product groups in different geographies and subsequent DC location recommendations. It is advisable to collect the initial data in the format that can be used for subsequent modeling of the logistics strategy.

Customer service analysis

The quantitative data obtained are crucial for the analytical process carried out and thus for the final conclusions and recommendations given.

Logistics objectives and options

Logistics modelling: logistics options analysis

Modelling complete logistics structures

A brewery with canning lines has large economies of scale and a product with sufficient shelf life for a medium to large economic footprint. A bakery has much lower economies of scale and a product with a short lifespan and thus has a smaller footprint.

Sourcing models

The economies of scale of production, the customer service requirement and the logistics costs are all considered to provide an optimal factory size and operating radius, hence the economic footprint. One means of "rough-cut modeling" for an entire logistics operation is to use sourcing models.

Distribution centre location modelling

Clustering techniques are used to reduce the complexity of the problem: that is, all customers in the geographical proximity are grouped together. There is a consequent requirement during the modeling process to check and test the appropriateness of the model and the results produced.

When agreement has been reached or deviations understood, several alternative options can be tested. An additional step in the modeling process when sourcing models have been used is to redo the allocation with the landed costs as modified in the logistics simulation.

Practical considerations for site search

Logistics 10

As a result, the second major point becomes clear – the need for logistics planning and strategy to be recognized and used as an important ingredient in the corporate plan. As such, it can be considered and treated as a short-term factor, with little direct relevance to long-term planning.

Logistics organizational structures

Furthermore, the consequence of inadequate planning is often seen as a short-term operational problem. In fact, due to the size and scale of financial and physical investments, it is imperative to distinguish between long-term and short-term investments and, where necessary, to include relevant elements of distribution and logistics in the overall business plan.

This type of structure is known as mission management and is based on the concept of managing systems or flows. Clearly, the potential problems with mission management lie in the difficulty of managing and coordinating across functional boundaries.

As already indicated, the operational role of managers can vary considerably depending, among other things, on the size and nature of the company, product, channel type and customer profile. In addition to all these aspects of the operational role, and probably common to all types of distribution organizations, is the responsibility for and the need to maintain a balance between the service to the customer and the cost of providing this service.

Payment schemes

Financial bonuses can be offered as a form of pay-for-performance based on things like miles/kilometers driven, cases turned in, etc. Merit-based bonuses, perhaps based on participation, can be offered, and certainly productivity-related bonuses are likely to be very common, based on picked cases, moved pallets etc.

Drivers will most likely be paid for working hours or guaranteed hours - a form of day work. Additionally, there will likely be different rates depending on different job functions (forklift drivers, pickers, etc.).

Hiring temporary staff

Does the employment agency have all relevant insurance policies such as employer and liability coverage? Provide the agency with all relevant health and safety information in advance so they have time to brief their drivers.

Hiring temporary vehicles

The role of the logistics and distribution manager was assessed in terms of his input into the planning process and in terms of his operational role. Due to the rapid expansion of the latter, this has become a major problem for many companies.