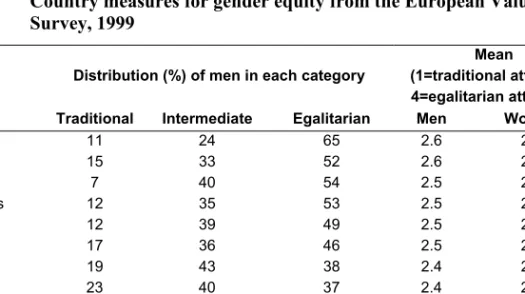

Stimulated by the recent debate on gender roles and men's fertility behavior (Puur et al. 2008; Westoff and Higgins 2009; Goldscheider, Oláh and Puur 2010), we present evidence from Finland as a country well into the second phase of the so-called. gender revolution. We present evidence from Finland as a country with a relatively high level of gender equality in both public and private life and thus well into the second phase of the gender revolution. However, they found that while “fertility is higher at the egalitarian end of the scale in Puur et al.

The wording of survey questions also varies (Westoff and Higgins 2009:72). This dilemma is at the heart of the debate between Puur et al. Reconciling work and family is one of the central objectives of Finnish family policy. Although equality is far from absolute, Finland and the other Nordic countries can be said to be well into the second phase of the gender revolution.

This fertility recovery has been attributed to high levels of development, including high gender equality, and possibly the impact of the family-friendly social policies described above (Myrskylä, Kohler, and Billari 2009). In a good relationship, it is important that both partners share responsibility for the survival of the family. Some questions were reversed so that a higher score on the composite variable indicates more equal attitudes toward gender roles.

We also analyzed the impact of family and public gender role dimensions separately by separating attitudes toward women's role in the public sphere from attitudes toward gender roles in the family, but found no significant differences between them among women.

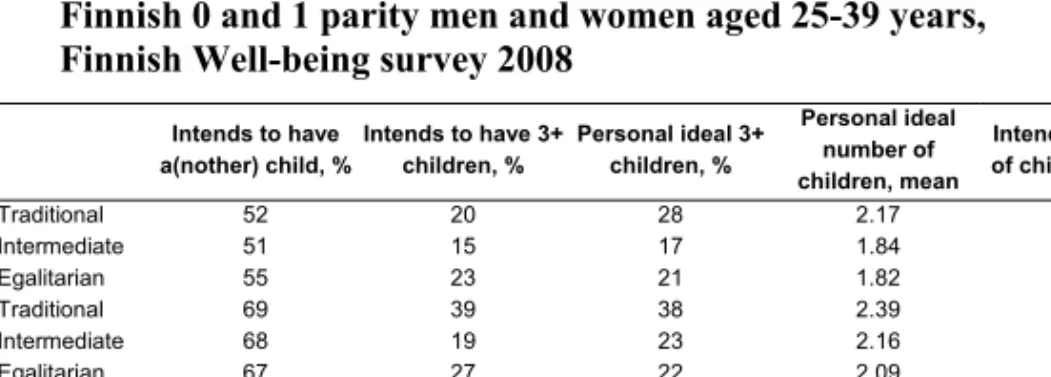

Descriptive results

How traditional and egalitarian gender attitudes relate to men's and women's intentions to have children in Finland. How is the influence of gender attitudes related to the fertility dimension under study (decisions regarding the near future versus more abstract ideals and goals). We expect that any association between egalitarian attitudes and fertility intentions will be most evident at critical steps in family formation in present-day Finland, that is, first the intention to have no children at all and then the intention to have many children.

Based on these descriptive statistics, traditional gender ideology slightly increases childbearing intentions and ideals among Finnish men. However, egalitarian childless men have higher fertility intentions than average men and plan to have three or more children more often than traditional men. Below, we explore how childbearing ideals and intentions are related to gender ideology after controlling for partnership and other factors.

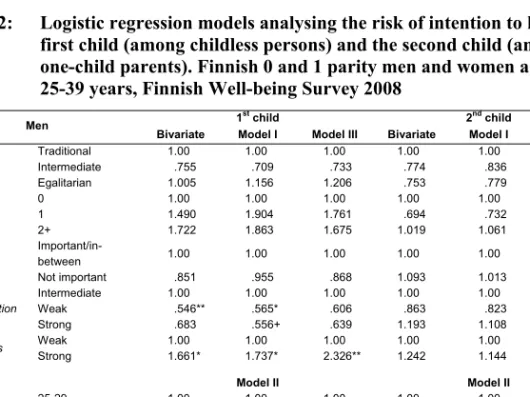

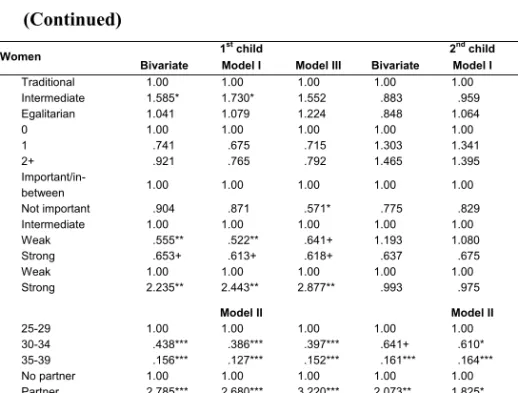

Regression section

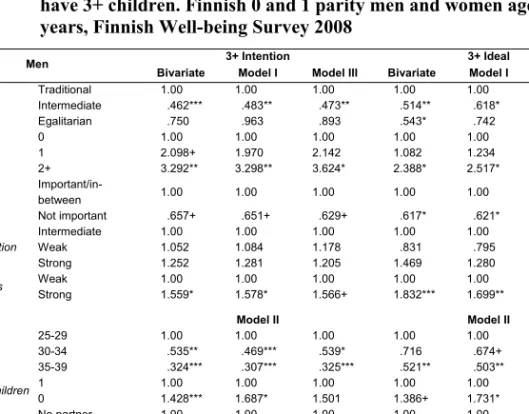

Finnish parents show a strong motivation to have a sister or brother for the first child, and this seems to override other ideational motives for having children. Multivariate analysis of intention to have the first child provides some support for this observation. However, there was a clear and significant impact of gender attitudes regarding more abstract fertility desires, or the ideals and intentions to have three or more children (Tables 3 and A3).

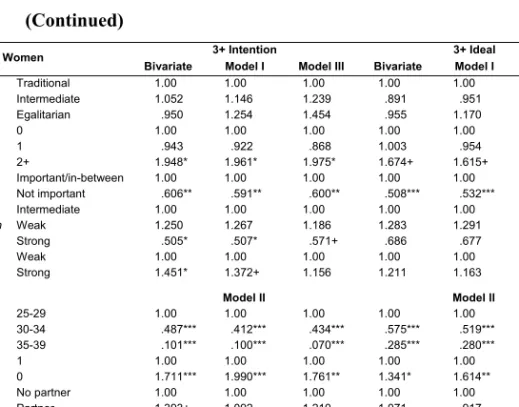

Egalitarian men are not significantly different from traditional men, while intermediate attitudes significantly reduce men's higher fertility intentions and ideals. In the multivariate analysis, women's egalitarian attitudes showed a positive but non-significant association with higher fertility intentions and this was stronger among mothers. In contrast, inclusion of partnership status in the models reduced the positive impact of intermediate gender attitudes on women's fertility intentions (Table A2).

We were interested in whether strong family orientation and low work orientation would increase fertility intentions independent of gender attitudes. Indeed, strong family orientation was consistently and significantly related to both men's and women's intentions to have a first child (Table A2). As expected, family orientation (as well as other ideological variables) does not show any significant relationship with the intention to have a second child.

This is plausible since for many young people in our data the decision to have a third child (or more than three) is still distant and less dependent on structural barriers than the decision to have the (next) child in in the near future. We also found a statistically significant interaction effect of education and gender attitudes on the fertility intentions of childless respondents (results not shown). Educational attainment moderated the effect of gender attitudes on parenting intentions, such that egalitarian attitudes increased parenting intentions among men with low and secondary education.

Among academic women, traditional gender attitudes increased parenting intentions compared to women with intermediate or egalitarian attitudes. In summary, we found some evidence that egalitarian attitudes increase men's risk of fatherhood when controlling for structural and ideational factors, although traditional attitudes also slightly increased this risk, and neither result was statistically significant. As expected, the impact of gender ideology (and other ideological factors) was visible both in the transition to parenthood and in terms of plans to have three or more children, but least pronounced in terms of the transition to a second child, which is a very common event in modern Finland.

Discussion

The impact of gender ideology significantly influenced men's overall fertility ideals and plans, such that traditional men were more likely and men with intermediate attitudes were least likely to desire and plan many children. The evidence from Finland presented here therefore lends slight support to Puur et al. 2008), in that egalitarian men seem the most eager to become fathers. However, traditional attitudes also clearly boost men's fertility ideals in the direction Westoff and Higgins (2009) found.

We controlled for family and work orientation and found that egalitarian attitudes still elicited post-parenthood intentions. Family orientation, however, is consistently and significantly related to men's and women's intentions after having their first child, as well as to men's intentions regarding greater fertility. The independent effect of gender attitudes and family orientation on men's fertility intentions remained after controlling for other conceptual and structural variables.

As in many previous studies, the impact of gender attitudes depended on the component of fertility that was examined. Gender attitudes had more influence on higher fertility intentions (among men) than on the immediate and more concrete decision to have the next child. While egalitarian men are almost as likely as traditional men to choose parenthood and large families, they may start having children at a later stage than other men.

Nevertheless, to understand how gender attitudes relate to fertility intentions, the inclusion of more abstract ideals and plans is warranted. To conclude, our findings suggest a preliminary U-shaped association between gender attitudes and fertility among Finnish men. Traditional but also egalitarian attitudes increase men's fertility intentions, especially related to above-average numbers of children.

Contrary to most other previous research, we found that Finnish women with traditional gender attitudes did not want more children than other women. Women's education level, income, family and work orientation were more important to their fertility goals than their gender role attitudes. We must also remember that egalitarian Finnish fathers of one were not extremely eager to have two or more children.

Acknowledgments

Men's reproductive desires and views on the male role in Europe at the beginning of the 21st century. The relationship between men's attitudes towards sex and fertility: a reply to Puur et al. "Men's Desires for Childbirth and Views of the Male Role in Europe at the Beginning of the 21st Century".

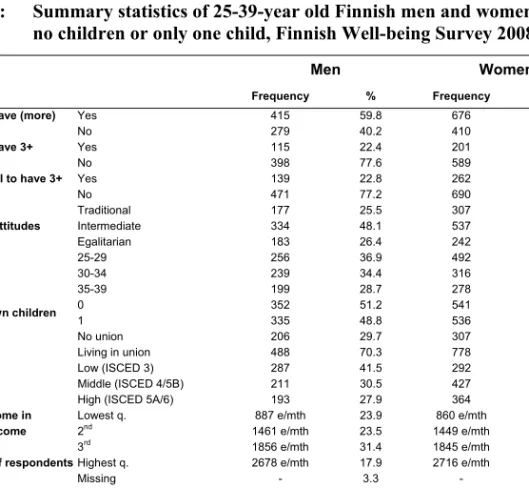

Summary Statistics

Logistic Regression