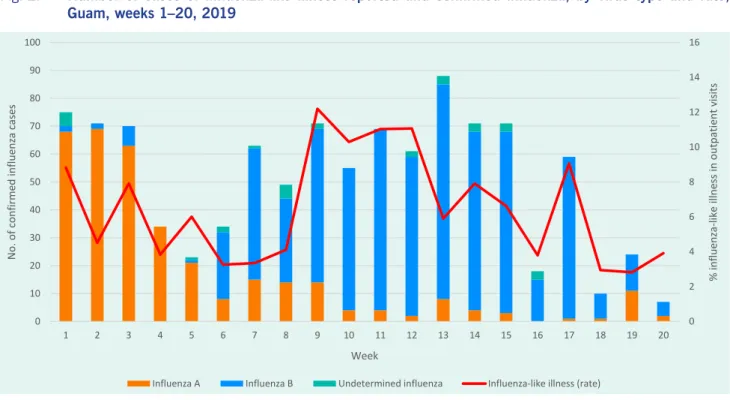

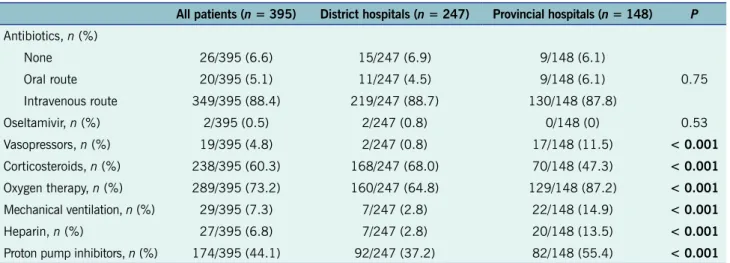

In May 2021, the World Health Assembly recommended investments in the health workforce to better manage the COVID-19.5 pandemic. This report describes data collected through the World Health Organization's Pacific Syndrome Surveillance System for the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), Guam, the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), and the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI). Number of cases of influenza-like illness reported in four of the Pacific Islands associated with the US: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, and the Republic of the Marshall Islands, weeks 1–23, 2019.

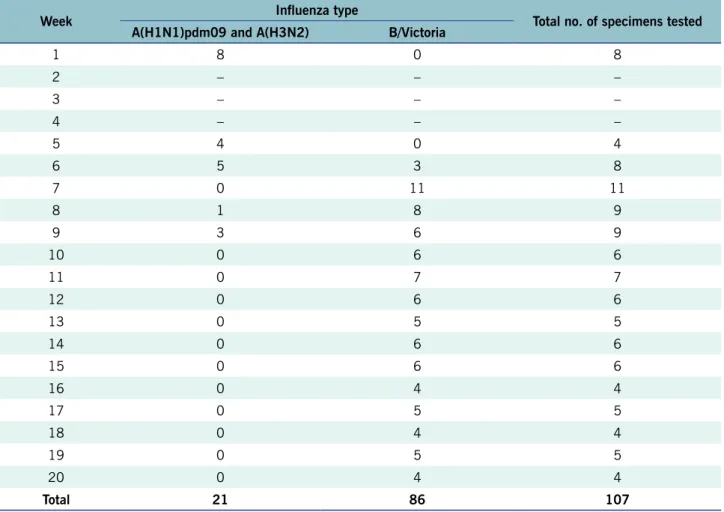

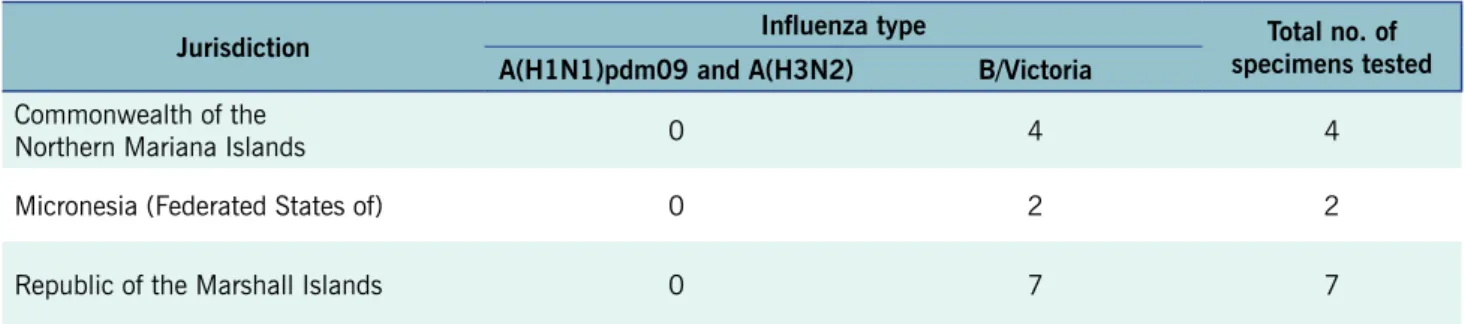

By the peak of the outbreak in week 13, influenza B viruses accounted for confirmed cases. Of the two specimens from Yap subtyped by the Guam Public Health Laboratory, both were influenza B/Victoria (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

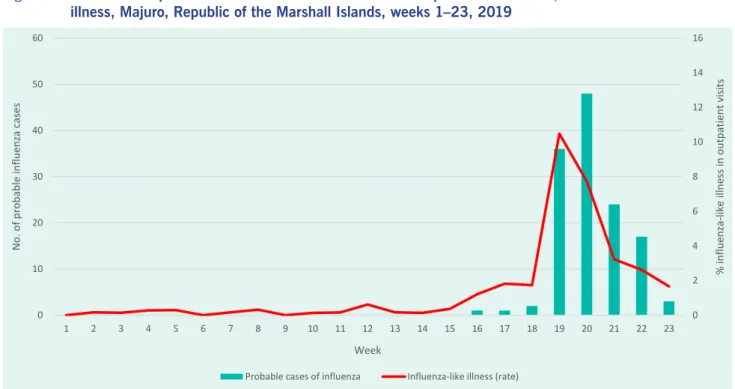

Although the timing of these influenza outbreaks in these Micronesian islands was consistent with the northern temperate climate, where influenza activity increases during the winter months,6 the occurrence of influenza B/Victoria did not match the patterns of viruses circulating in the United States. continent. Between weeks 1 and 20, only 5% of influenza cases reported to the US GISRS were caused by influenza B viruses.7 The Oceania–Melanesia–Polynesia influenza transmission area, of which all Pacific islands associated with the US are members, had a similar low levels of influenza B cases according to the global reporting system.7 Patterns of confirmed influenza cases in the wider WHO Western Pacific region recorded during week 15. Number of reported cases of influenza-like illness and probable influenza with influenza-like illness, Majuro, Republic of the Marshall Islands, 1-23 weeks of 2019.

RMI received 2,049 visitors during the period January-March 2019, with peaks in March.10 Data from previous years suggest that the majority of visitors to RMI come from other Pacific Islands and North America,11 and FSM visitors are mainly from the US.12 However, Guam serves as a major air transport hub for FSM and RMI, which may have provided an opportunity for the introduction of influenza B. The epidemiological evidence provided on the vaccination status of influenza cases has implications for policy of immunization.

CONCLUSIONS

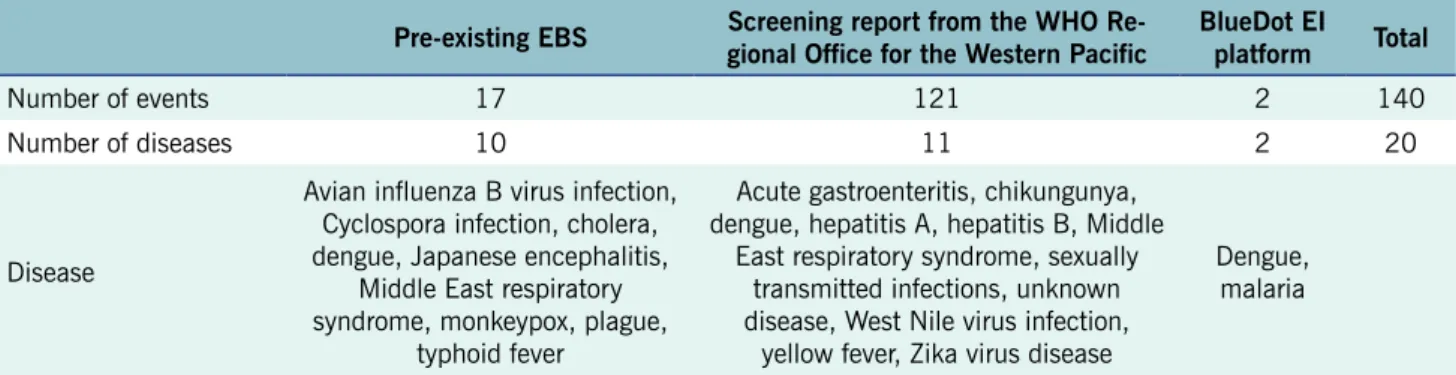

This article describes the methodology and preliminary results of the improved EBS for infectious diseases occurring overseas (excluding covid-19) that have potential for import before and during the Games. The enhanced EBS before and during the Games did not detect any major public health event that would warrant action for the Games. The enhanced EBS for the Games was conducted at the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID), Japan, which hosts the country's Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP).

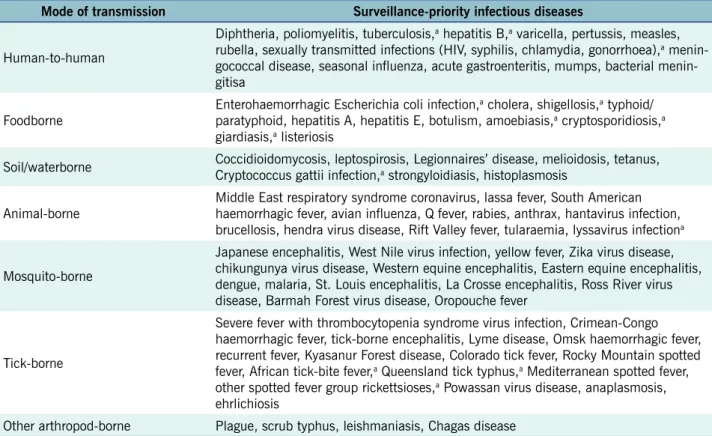

The enhanced EBS for infectious diseases occurring overseas (except for COVID-19) included the pre-existing EBS system plus two external systems - the open source World Health Organization (WHO) Epidemic Intelligence System (EIOS) and BlueDot. The Epidemic Intelligence (EI) Platform, a surveillance and risk assessment platform that uses both artificial intelligence and human intelligence (Fig. 1).4,5. Second, if there was an import risk associated with the Games, the subsequent risk of transmission between Games personnel and athletes was assessed.

RESULTS

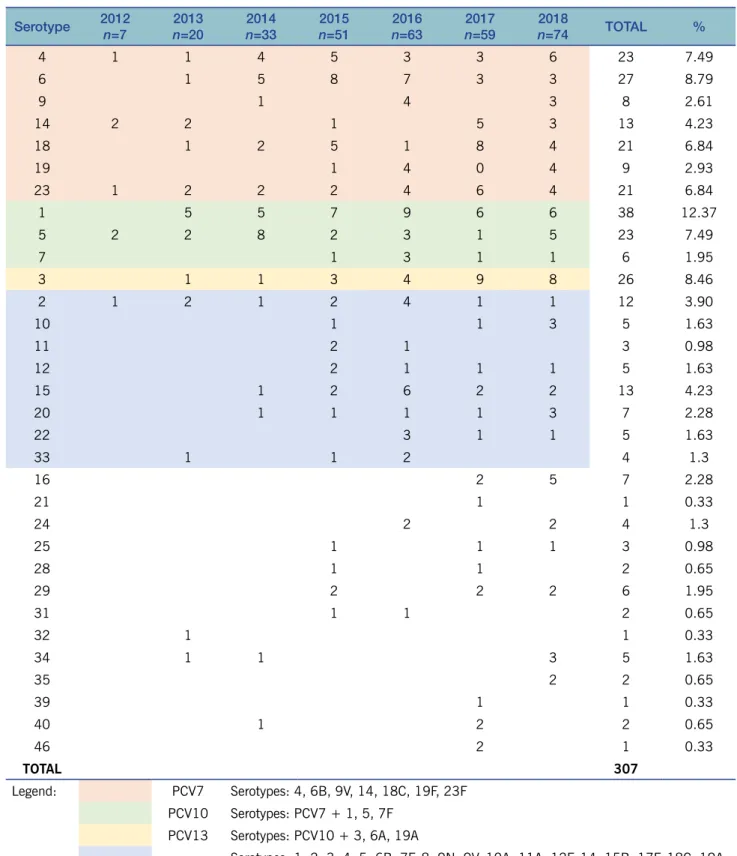

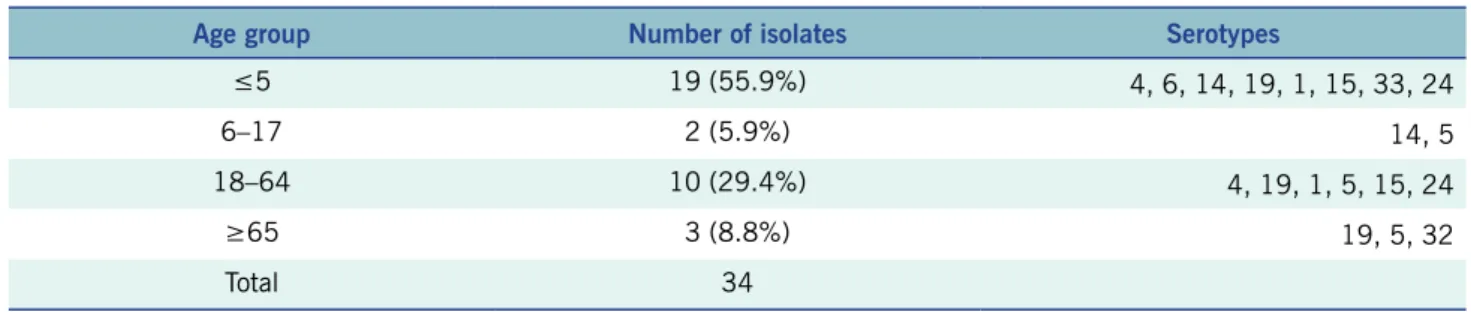

Objective: There is scarce data on the prevalent serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the Philippines, including the relative antimicrobial resistance (AMR) of these bacteria. Discussion: With the inclusion of PCV13 in the National Immunization Program, continued monitoring of the prevalent serotypes of S. Data on the prevalent pneumococcal serotypes in the Philippines, including their resistance to specific antimicrobials, are lacking.

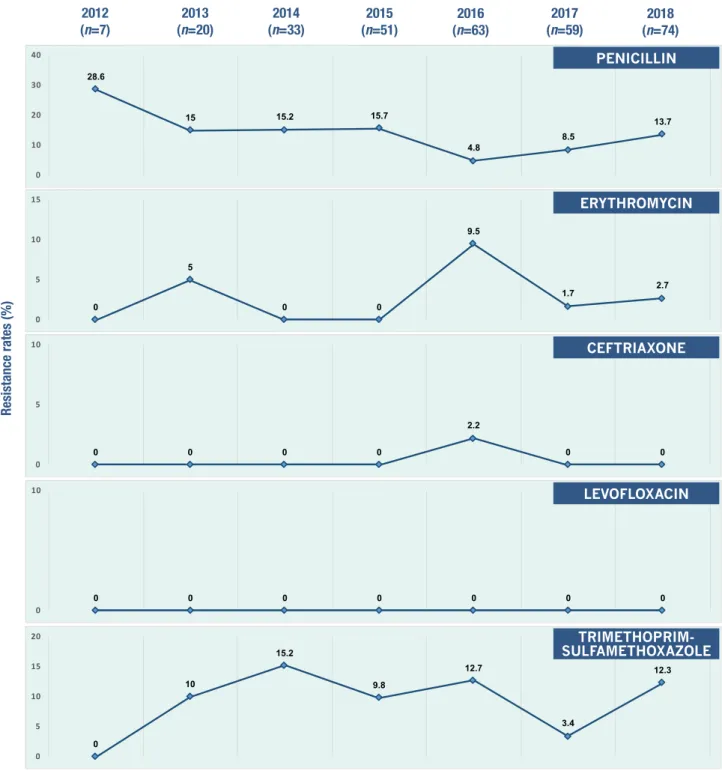

Thus, the sampling in the current study is largely based on diagnostic practices of the clinicians at the sentinel station. Annual Antimicrobial Resistance Rate of Penicillin, Erythromycin, Ceftriaxone, Levofloxacin, and Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole in the Philippines, 2012–2018.

CONCLUSION

Phase 2 Phase 3

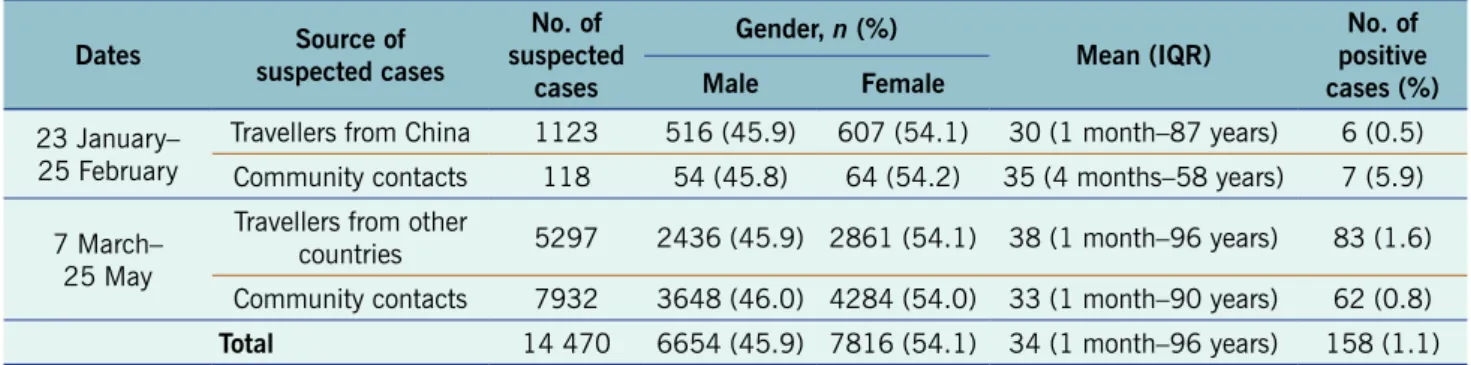

Conclusion: Asymptomatic and presymptomatic infections were common during the second wave of COVID-19 in Vietnam.

PROBLEM

CONTEXT

The two index cases were admitted to the medical ward of Hospital 1 on 20 and 26 March 2020 for the management of COVID-19. Their respective dates of diagnosis and notification to the Department of Health were 19 and 26 March. All three HCW cases worked on the medical ward of Hospital 1, although none provided direct care to the two index patients.

Of the cases, 81 were HCWs, 23 were patients in the three hospitals, one was a resident of the aged care facility, and 33 were close contacts. Of the 81 cases among HCWs, 72 (89%) worked in Hospital 1, some of whom also worked in other facilities during the outbreak period, and 49 (60%) were nurses. HCWs are at risk of contracting COVID-19 infection from their patients and subsequently causing or amplifying healthcare outbreaks.2,3 In recognition of the expected increased risk from the pandemic, hospitals in Tasmania had stepped up infection prevention - and monitoring procedures, even though only nine patients with COVID-19 were being treated at a hospital in Tasmania prior to this outbreak.

Outbreak cases were defined according to Australian national guidelines4 as persons with laboratory confirmation of COVID-19 by nucleic acid testing from a deep nasopharyngeal swab, with disease onset on or after March 19, 2020, who had an epidemiological link direct or indirect. in any of three health care facilities (Hospitals 1–3) in the North West region of Tasmania. Map of Australia showing Tasmania (inset) and the north coast of Tasmania showing the locations of health care facilities involved in the outbreak. Epidemic curve of COVID-19 cases associated with the northwest outbreak in Tasmania, Australia, from March to May 2020.

April 11 – Quarantine of HCWs from the medical and surgical departments of Hospital 1; additional staff support provided from Hospital 2. April 13 – Closure of Hospital 1 and 2 and all adjacent facilities; quarantine of all HCWs and their household contacts from these facilities April 6 – Hospital closed. HCW: healthcare worker (all HCWs including medical, nursing, allied health, administration, technical support and catering staff); Patients: people who contracted the disease while staying in one of the healthcare facilities; Other: all other linked cases, mostly household contacts of HCWs.

ACTION

However, at this stage of the pandemic, the importance of infection and asymptomatic transmission was not recognized; therefore, testing asymptomatic contacts was not standard practice.4,10. Reasons for individuals continuing to work include workplace culture and expectations, the desire to support their colleagues, especially when there is a shortage of staff, and to maintain income, a particularly important consideration for casual workers.11, 12 Interventions were subsequently introduced to support this cultural change, including screening staff for acute respiratory symptoms before each shift, requiring COVID-19 testing for staff who develop acute respiratory infection, and developing operational frameworks to support absences of staff due to symptomatic respiratory infections and pending test results. There were many challenges with timely identification of close contacts from the three hospitals.

One challenge was locating multiple electronic and paper information systems to identify staff and patient movements during the outbreak, often by members of the outbreak investigation team who were unfamiliar with the local environment. COVID-19 response guidelines and the definition of a close contact were regularly updated throughout the study, and as the outbreak escalated, contact tracing became overwhelming for the number of contact tracers available.5 These logistical difficulties made quarantining close contacts a challenge .9 ,12. The outbreak occurred early in the pandemic, when national guidelines limited COVID-19 testing to those with symptoms and access to rapid testing was limited.4 As a result, not all contacts were tested.

This hindered the rapid identification of new cases and may have resulted in asymptomatic cases going undetected, possibly contributing to transmission. Outbreak management principles, including the testing of asymptomatic contacts, were later added to the Australian series of national guidelines for COVID-19 businesses on 28 May 2020.4, the strictest restrictions in Australia at the. These control measures were followed by a reduction in the number of new cases over the following days.

The outbreak was declared over on 6 June after two incubation periods (i.e. 28 days) had passed with no new cases.

LESSONS LEARNT

The lessons of this first major Australian outbreak in a healthcare setting have contributed to ongoing interventions and pandemic responses across Tasmania and other states and territories of Australia. We recognize the many people who have worked in difficult circumstances to contain the COVID-19 outbreak in northwestern Tasmania and who continue to work to protect Tasmanians from a serious threat to their health and well-being. Risk of COVID-19 among frontline health workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study.

Many infectious disease staff were highly mobile within healthcare facilities or worked in more than one healthcare setting. Given the small regional hospital workforce at this location, mobility between health care and aged care facilities was inevitable. Some patients who were transferred between hospitals were infectious but not yet diagnosed with COVID-19; this contributed to transmission from Hospital 1 to Hospitals 2 and 3 early in the outbreak.

Infection Prevention and Control Practices Independent transmission from two index cases of COVID-19 to health care workers was confirmed by genomic analysis,13 and a subsequent case of transmission from a patient with COVID-19 to a health care worker in hospital 3 was identified by epidemiologic investigation.5 Although no specific violations of infection control protocols were raised by the health care workers concerned, strengthening of infection control practices for all health care workers was quickly implemented after the outbreak through increased funding and staff education, training, and support. 12. A contact tracing assessment of the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in Taiwan and the risk during different pre- and post-symptomatic exposure periods. Estimating the extent of asymptomatic COVID-19 and its potential for community transmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Containment of COVID-19 cases among health care workers: the role of surveillance, early detection, and outbreak management. COVID-19: integrating genomic and epidemiological data to inform public health interventions and policy in Tasmania, Australia. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG among healthcare workers of a large university hospital in Milan, Lombardy, Italy: a cross-sectional study.

WPS R