This Surgeon General's report returns to the subject of the health effects of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke. The 1979 Surgeon General's report, Smoking and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General (USDHEW 1979), also contains a chapter entitled "Involuntary Smoking." The chapter emphasizes that “attention to involuntary smoking is of recent vintage, and only limited information on the health effects of.

Organization of the Report

The agency also estimated that between 24,300 and 71,900 low birth weight or premature births, about 202,300 episodes of childhood asthma (new cases and exacerbations), between 150,000 and 300,000 cases of lower respiratory tract disease in children, and about 70,089 cases of middle ear infections in children occur each year in the United States as a result of exposure to secondhand smoke. The health effects of secondhand smoking have not received extensive coverage in this series of reports since 1986. Reports since then have addressed selected aspects of the topic: the 1994 report on tobacco use among youth (USDHHS 1994), the 1998 report on tobacco use among U.S.

Because second-hand smoke remains widespread in the United States and other countries, preparation of this report was motivated by the continuation of second-hand smoke as a public health problem and the need to evaluate substantial new evidence reported that from 1986. This sub-report significantly expands the list of topics that were included in the 1986 report. For some associations of involuntary smoking with adverse health effects, only a few studies were reviewed in 1986 (p. eg, ear disease in children); now, the relevant literature is considerable.

Following the approach used in the 2004 report (The Health Consequences of Smoking, USDHHS 2004), this 2006 report also systematically evaluates the evidence for causation, assesses the extent of the available evidence, and then draws an inference about the nature of the association.

Preparation of the Report

Definitions and Terminology

Evidence Evaluation

To address the nexus, the report draws not only on the evidence for involuntary smoking, but also on the even more extensive literature on active smoking and disease. Although the evidence reviewed in this report largely comes from research on passive smoking, the larger body of evidence on active smoking is also relevant to many of the associations examined. The 1986 report found that passive smoking was qualitatively similar to regular smoke inhaled by the smoker and concluded that passive smoking was expected to “have a toxic and carcinogenic potential.

Adult exposure to secondhand smoke has immediate adverse effects on the cardiovascular system and causes coronary heart disease and lung cancer. The scientific evidence indicates that there is no risk-free exposure to passive smoking. Many millions of Americans, both children and adults, are still exposed to secondhand smoke in their homes and workplaces despite significant progress in tobacco control.

Chapters in this report consider the evidence on active smoking relevant to the biological plausibility of causal links between involuntary smoking and disease.

Major Conclusions

Consistency, coherence and the temporal relationship of involuntary smoking with disease are central to the interpretations in this report. The 2004 report of the Surgeon General reviewed the health consequences of active smoking (USDHHS 2004), and the conclusions greatly expanded the list of diseases and conditions caused by smoking. The reviews included in this report cover evidence identified through search strategies outlined in each chapter.

Because of the significant time involved in preparing this report, lists of new key references published after these cut-off dates are included in an appendix. Literature reviews were expanded when new evidence was sufficient to possibly change the level of a causal conclusion.

Chapter Conclusions

- Assessment of Exposure to Secondhand Smoke

- Toxicology of Secondhand Smoke

- Prevalence of Exposure to Secondhand Smoke

- Reproductive and Developmental Effects from

- Respiratory Effects in Children from Exposure

- Cancer Among Adults from Exposure to Secondhand Smoke

- Cardiovascular Diseases from Exposure to Secondhand Smoke

- Respiratory Effects in Adults from Exposure to Secondhand Smoke

- Control of Secondhand Smoke Exposure

The evidence is insufficient to infer the presence or absence of a causal relationship between secondhand smoke exposure and neonatal mortality. The evidence is sufficient to infer a causal relationship between secondhand smoke exposure and sudden infant death syndrome. The evidence is insufficient to infer the presence or absence of a causal relationship between secondhand smoke exposure and birth defects.

The evidence is suggestive but not sufficient to infer a causal relationship between secondhand smoke and breast cancer. The evidence is sufficient to infer a causal relationship between secondhand smoke exposure and olfactory grin. The evidence is sufficient to infer a causal relationship between secondhand smoke exposure and nasal irritation.

The evidence is suggestive, but not sufficient to infer a causal relationship between passive smoking and chronic respiratory symptoms.

Classification of Secondhand Smoke Exposure

Cigarette smoke is, of course, the source of most secondhand smoke in the United States, followed by pipes, cigars, and other products. Epidemiological studies generally focus on assessing the exposure, which is contact with secondhand smoke. Biomarkers can give an indication of an exposure or possibly the dose, but for secondhand smoke it is only used for recent exposure.

People are exposed to secondhand smoke in a number of different places, often referred to as "microenvironments" (NRC 1991). Some key microenvironments for secondhand smoke include the home, the workplace, public places, and transportation environments (Klepeis 1999). Questionnaires assessing exposure have been the primary instrument used in epidemiologic studies of secondhand smoke and disease.

With air concentrations of markers and information on time activity, estimates of secondhand smoke exposure can be made with the microenvironmental model.

Misclassification of Secondhand Smoke Exposure

With respect to random misclassification of secondhand smoke exposure, there is an inherent degree of unavoidable measurement error in the exposure measures used in epidemiologic studies. One specific form of misclassification has been raised regarding exposure to secondhand smoke and lung cancer: the classification of some current or former smokers as lifetime nonsmokers (USEPA 1992; Most studies of lung cancer and secondhand smoke have used spousal smoking as the main exposure variable.

During the time that the epidemiological studies of passive smoking have been conducted, exposure has been widespread and virtually unavoidable. This distortion was also recognized in the 1986 NRC report, and this misclassification was corrected for in the estimate of lung cancer (NRC 1986). Similarly, the EPA's 1992 report commented on background exposure and made an adjustment (USEPA 1992).

The possibility of publication bias has been raised as a potential limitation to the interpretation of evidence on involuntary smoking and disease in general, and specifically on lung cancer exposure and secondhand smoke.

Confounding

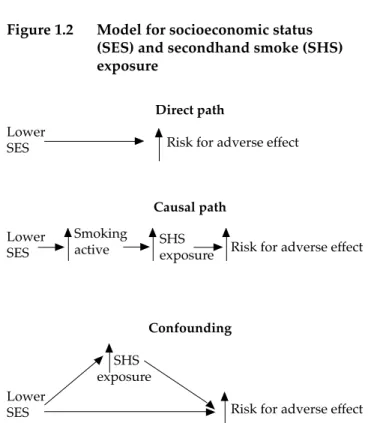

Confounding implies that the confounding factor has an effect on risk that is independent of passive smoking. However, some factors considered as potential confounders may be in the same causal pathway as secondhand smoke exposure. Although socioeconomic status (SES) is often cited as a potential confounding factor, it may not have an independent effect but may influence disease risk through its association with passive smoking (Figure 1.2).

This figure shows general alternative relationships between SES, exposure to passive smoking and the risk of a negative effect. For example, controlling for SES would not be appropriate if this is a determining factor for exposure to passive smoking, but has no direct effect. Survey data from the United States (Matanoski et al. 1995) and the United Kingdom (Thornton et al. 1994) show that adults exposed to passive smoking tend to have less healthy lifestyles.

The importance of correlation with the interpretation of the evidence further depends on the magnitude of the effect of secondhand smoke on disease.

Tobacco Industry Activities

SES may have a direct effect, or exert its effect indirectly through an association with passive smoking exposure, or it may confound the relationship between passive smoking exposure and disease risk. Controlling for SES as a potential confounder without considering underlying relationships can lead to incorrect risk estimates. Nevertheless, because the health effects of involuntary smoking have other causes, the potential for confounding should be carefully examined when assessing associations of passive smoking exposure with adverse health effects.

Potential bias from confounding varies with the association of the confounder with secondhand smoke exposures in a particular study and with the strength of the confounder as a risk factor. As the strength of an association decreases, confounding as an alternative explanation for an association becomes an increasing concern. In previous reviews, confounding has been addressed either quantitatively (Hackshaw et al. 1997) or qualitatively (Cal/EPA 1997; Thun et al. 1999).

In the chapters of this report that focus on specific diseases, confounding is specifically addressed in the context of potential confounding factors for particular diseases.

A Vision for the Future

As these and other research questions are addressed, the scientific literature documenting the adverse health effects of secondhand smoke exposure will expand. Similarly, since the 1986 report (USDHHS 1986), the number of adverse health effects caused by exposure to secondhand smoke has also expanded. With this expanding base of scientific knowledge, the list of adverse health effects caused by exposure to secondhand smoke is likely to grow.

Biomarker data from the 2005 Third National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals document major progress since the 1986 report in reducing nonsmokers' involuntary exposure to secondhand smoke (CDC 2005). First, there is a need to continue and even improve monitoring of sources and levels of exposure to passive smoking. Second, data from the 2005 Exposure Report suggest that the scientific community must maintain current momentum to reduce nonsmokers' exposure to secondhand smoke (CDC 2005).

Continued progress toward a society free from involuntary exposure to secondhand smoke must remain a national public health priority.

IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking. An introduction to the indirect exposure assessment approach: modeling human exposure using microenvironmental measurements and the recent National Human Activity Pattern Survey. Misclassification of smoking habits as assessed by cotinine or by repeated self-reporting – summary of evidence from 42 studies.

Characteristics of nonsmoking women in NHANES I and NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study with Exposure to Smoking Spouses. Tobacco industry efforts undermine International Agency for Research on Cancer's secondhand smoke study. The reliability of passive smoking history reported in a case-control study of lung cancer.

Meta-analytic approaches to dose-response relationships, with application in studies of lung cancer and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke.