With only a few months left on the 14-year timeline of the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), it is clear that developing countries are racing against time to achieve the MDGs on eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, with experts rightly noting the herculean nature of such a task (Bain et al, 2014; Ferreira and Ravallion, 2008; Perera and Lee, 2013; Sumner, 2010). The beginning of the 21st century witnessed a rapid economic decline in Zimbabwe due to several reasons. The economic challenges currently facing Zimbabwe have derailed efforts to bring development to the rural areas of the country that have long been neglected since colonial times.

Under such circumstances, the aforementioned ongoing loss of the country's biological diversity is therefore a serious cause for concern.

Aim of the study 6

The key challenge for conservation authorities around the world is to devise conservation initiatives that embrace the livelihoods of neighboring communities (Makindi, 2010; Meilby et al, 2014; Miller, 2014; Pinho et al, 2014; Turner et al, 2012). ). The constant cry in current international conservation literature is that natural areas cannot survive without making a meaningful contribution to the livelihoods of the natural resource-dependent poor rural communities with which they often share their borders (Cronkleton et al, 2012; Gurney et al, 2014; Kashwan, 2013; McNeely and Miller, 1984; Mombeshora and Le Bel, 2009; Pinho et al, 2014; Romero et al, 2012; Scherl et al, 2004; Zhang et al, 2014). There has been no study that examines rural livelihoods in relation to protected areas through a comparative analysis of cases from different conservation approaches in Zimbabwe.

While some comparative studies have been conducted, for example Bond (1999) and Mashinya (2007), these have focused on comparing cases of community-based conservation, with none comparing cases from different conservation approaches.

Research objectives 6

Elements of the SLA 10

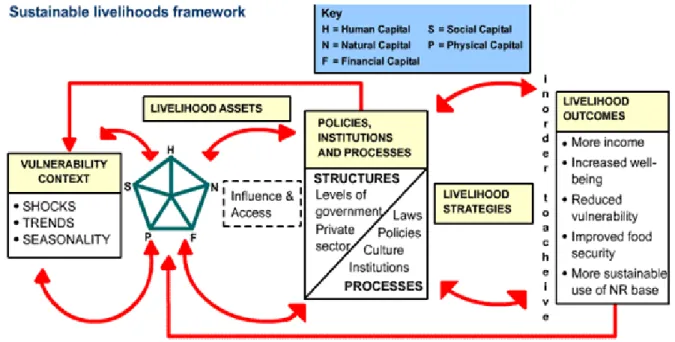

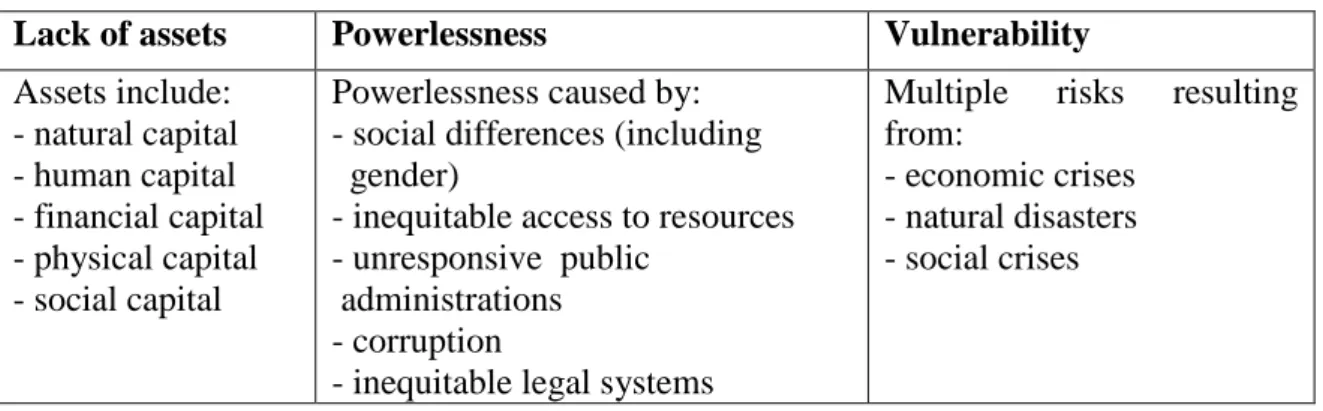

Assets refer to the basic material and social resources that people have in their possession (stores, resources, demands etc.) (Chambers and Conway, 1992; Ferrol-Schulte et al, 2013; . Scoones, 1998). Natural capital refers to the natural resource stocks (land, water, air, genetic resources, etc.) from which resource flows and services useful for livelihoods are obtained (Fisher et al, 2013; Scoones, 1998). Finally, social capital refers to the social resources that people use in the pursuit of livelihood goals (Chambers and Conway, 1992; Liu et al, 2014; Scoones, 1998).

Livelihood strategies refer to the range and combination of activities that people perform to achieve their livelihood goals (Chambers and Conway, 1992; Scoones, 1998; . Soltani et al, 2012).

Relevance of the SLA to current study 13

The nature and extent of the linkages between conservation and livelihoods, including the roles and responsibilities of different interest groups in addressing them, remain controversial (Roe and Walpole, 2010; Sanderson and Redford, 2003). Echoing this, Scoones and Wolmer (2003) state that hidden in the 'policies, institutions and processes' box of the livelihoods framework was a whole world of complex institutional arrangements, social relations and policy processes, all influenced by power and politics. The rather technocratic application of the livelihoods framework in the context of aid programming and project planning minimizes issues of power and politics (Scoones, 2009; Scoones and Wolmer, 2003).

Despite the above and other criticisms, the sustainable livelihoods framework has much to offer rural development.

Political ecology: exploring the political contours of conservation 15

Another defining characteristic of political ecology is that it is actor-based, focusing on all the people and organizations involved in conflicts over environmental issues (Borgerhoff Mulder and Coppolillo, 2005; Wilshusen, 2003). The third characteristic of political ecology lies in its deep commitment to a historical approach (Borgerhoff Mulder and Coppolillo, 2005; Fisher et al, 2013; Wilshusen, 2003). Finally, political ecology deals with the social construction of natural resources by social actors at every level, from village leaders to international institutions.

These characteristics of political ecology make it a suitable theoretical guide within which to explore and discuss issues of conservation and livelihoods, on which the present study focuses.

Conclusion 17

In particular, the political-ecology framework is useful in unraveling the various local to non-local factors, and also from local to non-local actors, involved in the conservation and livelihood initiatives in the two study areas. An understanding of livelihoods and transformative structures and processes in rural areas is critical for organizations pursuing conservation and development goals simultaneously. Political ecology recognizes that there are several stakeholders involved in the conservation and sustainable use of natural resources, some of which are local while others are non-local actors.

This chapter critically examines and discusses the information and findings currently available in the field of biodiversity conservation and rural development.

Key terms and concepts 19

- Biodiversity 19

- Conservation 22

- Livelihoods 23

- Poverty 23

- Conservation-development initiatives 26

The selection of literature for discussion in this chapter was guided by the objectives of the study. Genetic Diversity: Genes are the sequences of the DNA molecule (deoxyribonucleic acid) and serve as the functional units of heredity (Noss and Cooperrider, 1994; Russell et al, 2011). The three main objectives of the World Conservation Strategy are: to maintain essential ecological processes and life support systems; the maintenance of genetic diversity; and to ensure the sustainable use of species and ecosystems (Hambler, 2004).

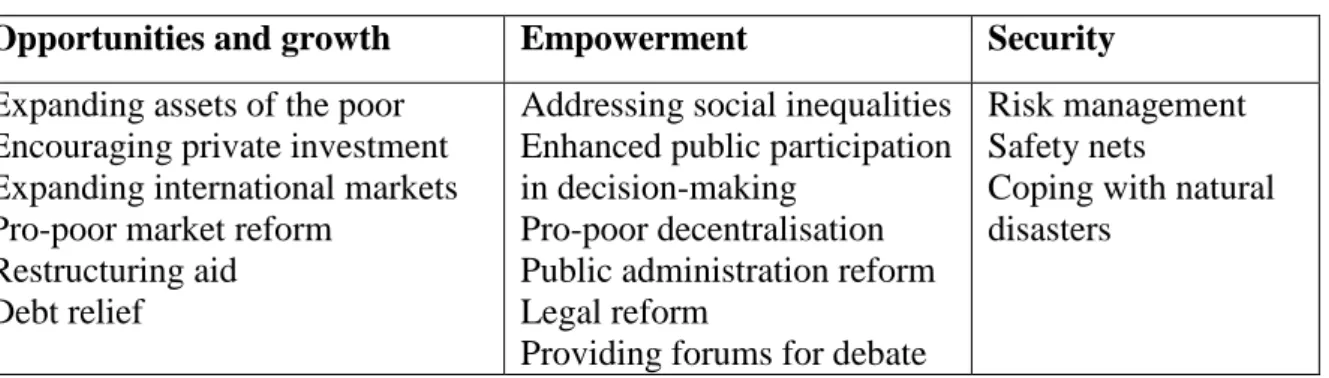

It is noteworthy that after more than a decade in which the World Bank has recognized key causes of poverty and identified strategies to intervene, as noted earlier, poverty has increased and challenges remain.

Downward trends in the biosphere 26

Brockington et al. note that “the most pressing need expressed by conservationists is the need to conserve biodiversity and combat the extinction crisis.” Although extinction has always existed as a natural process, it has currently become a primarily human-induced phenomenon especially since the second half of the 20th century due to increased human interaction with and manipulation of biological resources (Sandava et al, 2011; .Swanson, 1997). The observation of species declared extinct demonstrates the above challenge (Brockington et al, 2008; Jeffries, 2006; Seddon et al, 2014).

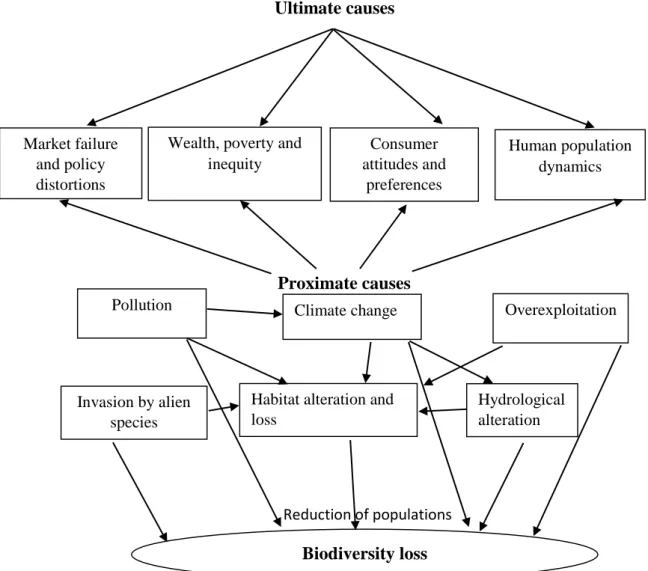

Proximate causes of loss include overexploitation of natural resources, invasion of alien species, pollution, climate change, alteration of hydrological systems, and habitat alteration and loss (Babigumira et al, 2014; Brook et al, 2014; Butchart et al, 2010; Hou et al, 2014 ; Laurance et al, 2014; Rands et al, 2010; Turpie, 2009).

Why biodiversity matters: valuing biodiversity 30

Use values of biodiversity: utilitarianism 31

- Direct use values: the resource-based argument 31

- Indirect use values: ecosystem services 35

Even in the developed world, where most of the food consumed comes from domesticated species, food supplies are critically dependent on wild populations and a. It is estimated that approximately 75% of the world's population depends mainly on traditional medicines obtained from wild natural products (Vira and Kontoleon, 2010). Indeed, natural products have long been recognized as an important source of therapeutically effective drugs in many parts of the world (Harvey, 2000).

However, it is important to note that most of the industrial uses of biodiversity have also greatly contributed to the degradation of the earth's biological resources.

Non-use values of biodiversity: ethics and aesthetics 37

- Option value: future worth 38

- Bequest value: intergenerational equity 38

- Intrinsic value: nurturing nature for nature’s sake 39

It has previously been shown that a relatively small part of the world's biodiversity is currently actively exploited by humans. However, it is apparently clear that including the option value among the non-use values is highly questionable as it still hints at the benefit of biodiversity to humans. They assume that value is expressed solely in terms of the well-being of humanity (Gaston and Spicer, 2004).

Without considering the morality of the needs of other creatures, policies to protect biodiversity will be built on shaky ground (Glenn et al, 2010; Maynard et al, 2014; Minteer and Miller, 2011; Noss and Cooperrider, 1994).

Biodiversity and protected areas 40

The history of protected areas 41

Definition and classification of protected areas 43

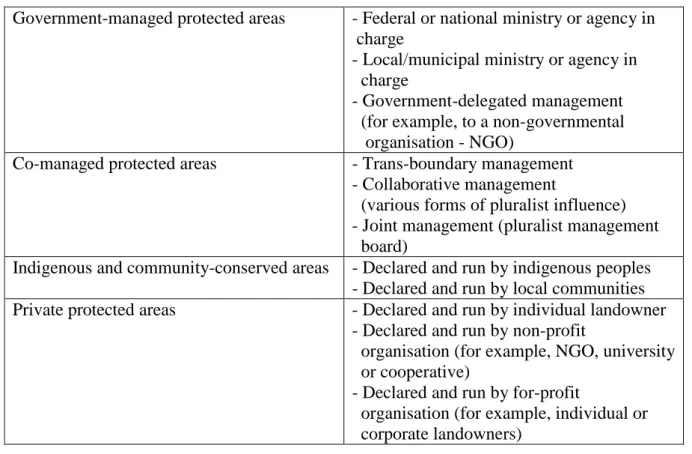

The main goal of protected areas is the long-term conservation of nature, in addition to associated ecosystem services and cultural values (Stolton, 2010b). It is important to note that half of the areas under protected areas in Europe are in category V (Dudley et al, 2010b). Controversy has also arisen over the use of management objectives in the IUCN classification of protected areas (Boitani et al, 2008; Dudley et al, 2010b).

Although the IUCN protected area categories have been criticized at various points, they currently provide the best concise overview of the multitude of protected area types (Stolton, 2010b).

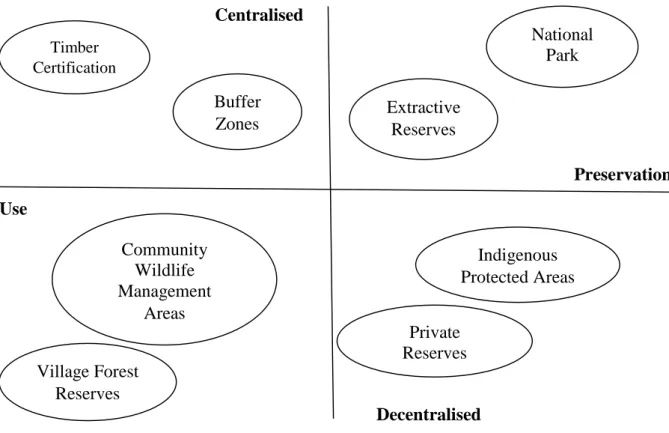

Protected area governance/management approaches 46

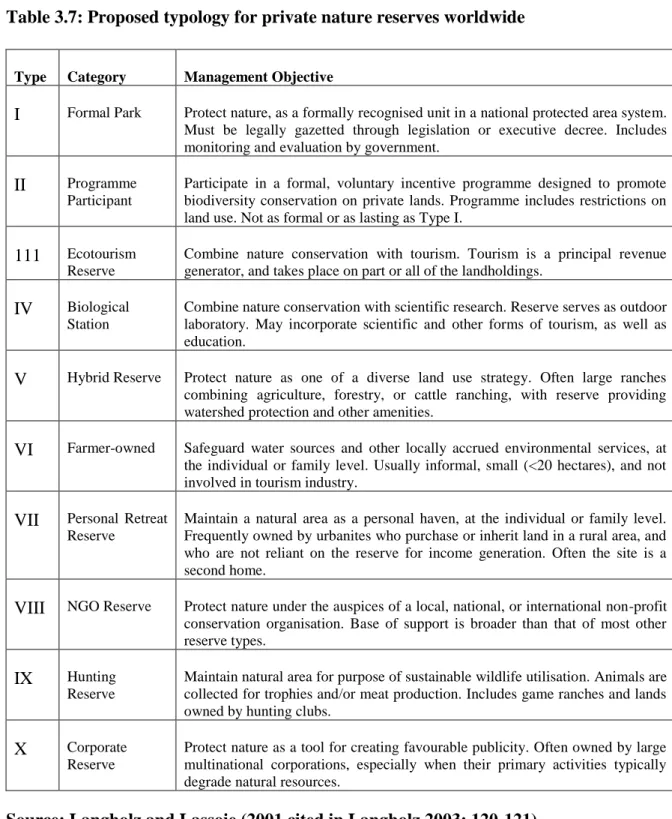

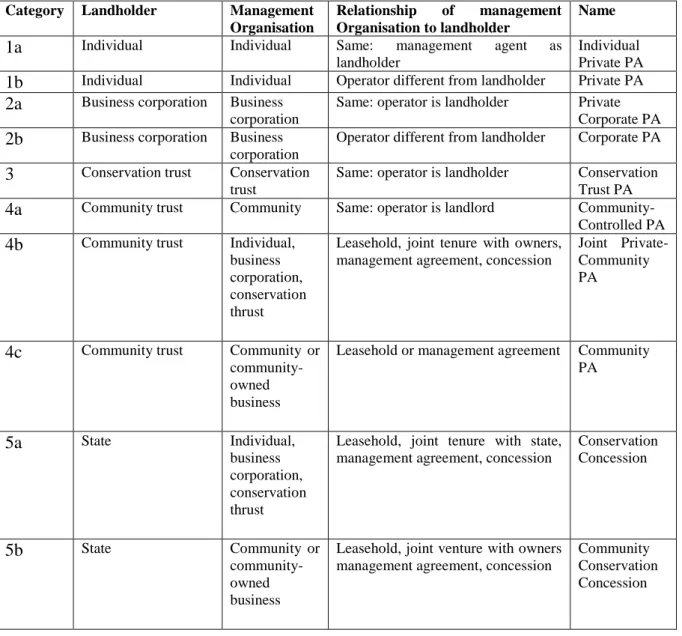

There is increasing recognition of the importance of the private sector to biodiversity conservation strategies (Carter et al, 2008; Iftekhar et al, 2014). There is no doubt that private protected areas now play an increasingly important role in conserving the world's biodiversity. Ironically, some of the same weaknesses in the typology by Langholz and Lassoie (2001) were pointed out by Carter et al (2008).

However, such a problem should not obscure the growing role that private protected areas now play in conserving global biodiversity. Despite the disadvantages mentioned above, private protected areas have proven to be an important tool for biodiversity conservation worldwide. Second, many of the jobs created by protected areas often do not go to local residents (Borgerhoff Mulder and Coppolillo, 2005; Leisher et al, 2010).

The term ecotourism emerged in the late 1980s as a direct result of the world's recognition of sustainable and global ecological practices (Coria and Calfucura, 2012) and is potentially the most direct and least intrusive way of deriving social and economic benefits from protectionism, and can be a very profitable enterprise for wildlife-rich areas (Agrawal and Redford, 2006; Borgerhoff Mulder and Coppolillo, 2005). Local communities view ecotourism positively because of the potential it brings for their participation in the economic growth of their area (Bayliss et al, 2014; Borgerhoff Mulder and Coppolillo, 2005). However, increasing population pressure on communal areas led to further land fragmentation.

While 54 of the country's 56 counties currently have the appropriate authority (Feresu, 2010), only 14 of these counties have consistently earned revenue from CAMPFIRE since 2000 (Mashinya, 2007). One of the objectives of the policy was infrastructural development in communal areas, which included roads, bridges, schools and clinics. It is worth noting that the liberation war that brought about independence also destroyed most of the limited infrastructure in communal areas (Bond, 1999).

Closely associated with the initial phases of the resettlement program was agricultural price policy. However, the impact of the growth centers on the economic development of the municipal areas has been disappointing (Conyers, 2001; Murashiki, 2010; Rambanapasi, 1990). This represented a major loss of livelihood as natural resources had played a vital role in the daily sustenance of the population.