http://jfn.sagepub.com/

Journal of Family Nursing

http://jfn.sagepub.com/content/17/2/202 The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/1074840711405527 2011 17: 202 Journal of Family NursingYu-Ting Chang and Mark Hayter

Grandchildren in Taiwan

Surrogate Mothers : Aboriginal Grandmothers Raising

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at:

Journal of Family Nursing

Additional services and information for

http://jfn.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://jfn.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

http://jfn.sagepub.com/content/17/2/202.refs.html Citations:

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

Journal of Family Nursing 17(2) 202 –223 © The Author(s) 2011 Reprints and permission: http://www. sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1074840711405527 http://jfn.sagepub.com

405527JFN17210.1177/1074840711405527 Chang and HayterJournal of Family Nursing © The Author(s) 2011 Reprints and permission: http://www. sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

1

Tzu Chi College of Technology, Hualien City, Taiwan 970, Republic of China

2

University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK

Corresponding Author:

Yu-Ting Chang, RN, MSN, Instructor, Department of Nursing, Tzu Chi College of Technology, 880, Sec. 2, Chien-kuo Rd., Hualien City, Taiwan 970 Hualien, Taiwan, Republic of China

Email: yuting@tccn.edu.tw

Surrogate Mothers:

Aboriginal

Grandmothers

Raising Grandchildren

in Taiwan

Yu-Ting Chang, RN, MSN

1and

Mark Hayter, PhD, RN, MSc, BA

2Abstract

The purpose of this qualitative study was to understand the experiences of Taiwanese aboriginal grandmothers when raising their grandchildren. Adopting a phenomenological approach, interviews were conducted with 15 Taiwanese aboriginal grandmothers who served as primary caregiver to a grandchild or grandchildren. Data were analyzed using Giorgi’s phenomeno-logical method. Four themes emerged from the data analysis, reflecting the parenting experience of grandmothers: using aged bodies to do energetic work: represented the physical effects of raising grandchildren; conflicting emotions: reflected the psychological effects of raising grandchildren; lifelong and privative obligation: described the cultural and societal beliefs of rais-ing grandchildren; and coprais-ing strategies for raisrais-ing grandchildren outlined methods the grandmothers used to cope with parenting their grandchildren. The results of this study offers insights into surrogate parenting within an underresearched group in Taiwan and will enable health care providers to be more aware of the physical, emotional, and social effects of the role of grandparent parenting.

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

Chang and Hayter 203

Keywords

grandmothers, grandparent parenting, child rearing, family caregiving, qualitative research, Taiwanese families

Grandparents who assume primary responsibility for raising their grand-children make up a fast-growing group of caregivers in the United States. Cur-rent estimates indicate that nearly 2.5 million grandpaCur-rents are raising their grandchildren (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009), and over 500,000 African Americans aged 45+ were estimated to be raising grandchildren (Minkler & Fuller-Thomson, 2005). In Taiwan, the 1988 census identified 39,500 households in which chil-dren were being raised by grandparents. Current estimates indicate that 86,900 children now live in households headed by grandparents (The Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, 2010). In addition, there are a significantly higher percentage of aboriginal grandparents than nonaboriginal grandparents raising their grandchildren in Taiwan (Chen, Weng, Hsu, & Lin, 2000). Unlike many Western nations where grandparents provide care for their grandchildren due to parental substance abuse, child neglect, child abuse (Bowers & Myers, 1999; Dowdell, 2004) or mothers being imprisoned (Ruiz, 2002), in Taiwan, most grandparents raising their grandchildren are doing so because the parents of the child are going through a divorce or working away from home (Chang, 2008). However, among the literature on “grandparent par-enting,” there is a distinct lack of empirical literature exploring this phenomenon in a Southeast Asian setting (Kataoka-Yahiro, Ceria, & Caulfield, 2004).

Raising Children: The Impact on Grandparents

Impact on Physical Health

The literature concerning the impact of parenting among grandparents dem-onstrates a varied picture. Minkler and Fuller-Thomson (1999) using quanti-tative survey data from African Americans found that custodial grandparents had more limitations in carrying out their daily living activities than did noncaregivers. Leder, Grinstead, and Torres (2007) also found that grandpar-ents who had higher parenting stress reported lower levels of physical health. In contrast, Hughes, Waite, LaPierre, and Luo (2007) conducted interviews with 12,872 grandparents aged 50 through 80 from across the cultural spec-trum in United States and found no evidence to suggest that caring for grand-children has a dramatic and widespread negative effect on a grandparent’s health and health behavior. Musil (1998) also found that there were no

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

204 Journal of Family Nursing17(2)

significant differences in self-assessed health between grandmother caregiv-ers and noncaregivcaregiv-ers within a questionnaire survey in the Middle East. Notable variability occurs within such studies, for example, Butler and Zakari (2005) conducted qualitative in-depth interviews with 17 parenting grand-parents in the United States and found that parenting grandgrand-parents’ self-ratings on physical health ranged from poor to excellent, with most grandparents rating themselves as having good health. However, Waldrop in a qualitative study with 37 American parenting grandparents (2003) described how 89% rated their health being adversely affected, with 22% feeling that parenting exacerbated preexisting health conditions.

Impact on Psychological Health

From a psychological perspective, the stress of caregiving has been associated with a decline in grandparental assessment of their emotional well-being. For example, qualitative research in the United States by Bowers and Myers (1999) and in Africa by Thupayagale-Tshweneagae (2008) found parenting by grand-parents produced significant psychological morbidity, including depression and loss of control. However, findings related to emotional well-being were inconsistent across studies in numerous cultures, with some grandmothers reporting their emotional state was equal to or better than the general popula-tion (Musil, 1998; Whitley, Kelley, & Sipe, 2001). Emopopula-tional responses to grandparent parenting can also vary—including feelings such as fear and anxi-ety, or love, satisfaction, and pride (Waldrop, 2003; Williamson, Softas-Nall, & Miller, 2003). From a socioeconomic perspective, grandparent parenting can have a significant impact. Fuller-Thomson and Minkler (2005) in their study of African Americans found that most of the caregiving grandparents faced a number of financial challenges. Musil (1998) found that Middle Eastern grandmothers with primary responsibility reported significantly less social time than partial responsibility grandmothers. Fuller-Thomson and Minkler (2005) revealed a portrait of grandparents committed to raising their grand-children despite the fact that many were living in extreme poverty, with lim-ited resources and services. Indeed, having sufficient financial resources to adequately support the grandchildren is often a key concern of grandparents (Butler & Zakari, 2005; Fitzpatrick & Reeve, 2003).

Grandparents Raising Grandchildren in Taiwan

Grandparents in Chinese countries, as well as in the United States, play an active role in their three-generation households by helping with household

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

Chang and Hayter 205

work and child care. The caring for children by their grandmother originates from the cultural belief in most Taiwanese families that a grandmother is the relative most frequently accepting of the role of caregiver to a relative’s children (Chi & Huang, 2006; Chia & Chen, 1999). Chiu (2004) investigated the strengths of parenting models via a Taiwanese case study involving single parent or absent parent nonaboriginal Taiwanese families, and determined that grandparenting could be a good substitute for absent or dysfunctional parenting, providing steady financial support, and promoting closer bonding with the younger generation. Tsai and Lue (2006), in a cross-sectional sur-vey, explored the relationships between grandparent parenting involvement and grandchild social-emotional behavior and found that the more concerned and respectful behavior that grandparents adopted, the more positive social-emotional behavior children performed. However, the limited literature on this topic found, as in much of the Western literature, that grandparents’ health status and psychological well-being were often adversely influenced by raising grandchildren, especially among those who have financial hard-ship, are raising a young grandchild, or have no support in performing child care (Chi & Huang, 2006; Hsu & Cheng, 2007).

There are, however, few studies on aboriginal grandmothers caregiving experiences. As of 2009, there were 498,549 aboriginals living in Taiwan, and Hualien County has the most aboriginals of all the Taiwan counties (Council of Indigenous Peoples, 2009; Hualien County Government, 2009). In addition, the situation of grandparents raising their grandchildren occurs significantly more frequently among aboriginals than among nonaboriginals in Taiwan (Chen et al., 2000). This is linked to a number of cultural and socioeconomic factors. Aboriginal family ties are very strong and parenting has traditionally been seen as a very important aspect of their culture. However, there has been more migration of young people away from tribal areas to urban areas to seek work. Also, there has been an increase in marriage of aboriginals to nonaboriginals in Taiwan. This, together with many young aboriginals’ developing a Westernized consumer culture has contributed to a greater burden on the older generation to care for children in parental absence. It may also be the case that older members of the tribal group still hold the parenting and family values of the culture in high regard—and as such, feel obliged to care for grandchildren whilst their parents are absent (Chen et al., 2000). However, despite these social changes and issues, there has been no systematic research exploring and examining the social phenomenon of how aboriginal grandmothers experience becoming the primary caregivers for their grandchildren in Taiwan.

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

206 Journal of Family Nursing17(2)

Method

Design

Given the exploratory nature of this study, a qualitative descriptive design, employing Giorgi’s (1997, 2005) phenomenological methodology guided this study. Giorgi’s (1997, 2005) approach allows researchers to explore the experiences of individuals in relation to a specific social phenomenon, devel-oping an understanding of their perspectives, feelings, and attitudes toward the particular situation they find themselves in. Giorgi’s approach empha-sizes three directives in the philosophy of phenomenology. These are (a) gener-ate a precise description, (b) stay within the functions of phenomenological reduction, and (c) seek the most invariant meanings for a context (Giorgi, 1997, 2005). This enables a detailed exploration of subjective experiences, as a means to seek understanding (Kleiman, 2004).

Participants

Following the principles of qualitative research, participants were selected through an initial convenience approach within four aboriginal townships in the Hualien region of Taiwan. A convenience approach initially identified grandmothers involved in parenting who therefore would be able to relate their experiences of this phenomenon. Following this initial sampling, snow-ball sampling was used by inviting participants to nominate other grand-mothers in a similar parenting situation for the research team to contact them for inclusion in the study.

Based on the philosophic perspectives of phenomenology, the interviewer needed to establish a trusting relationship with participants to gain rich descriptions of their experiences. To earn trust, the researcher was accompa-nied by the aboriginal grandmother acquaintance during the subsequent inter-view. Aboriginal grandmothers met the criteria for inclusion in the study if (a) they could speak Chinese, (b) the children currently lived with the grand-mother, (c) the grandmother assumed responsibility for raising the child or children, (d) at least one child was younger than age 3, and (e) the biological parents resided in the home only during holidays or other infrequent times, meaning contact was very minimal across the sample. The 15 participants ranged in age from 38 to 65, with a mean age of 55.3; 4 of the 15 were illiter-ate; 4 lived with grandchildren with no other family members in the home. Eight grandmothers had health problem such as hypertension, diabetes, and renal disease. Grandmothers were caring for grandchildren with ages 3 months

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

Chang and Hayter 207

to 14 years; most of them had raised their grandchild for more than 2 years, and 10 grandmothers cared for their grandchild throughout the full week (see Table 1).

Protection of Participants

Ethical approval for the research was obtained from Tzu Chi College of Technology, Hualien, Taiwan. Informed consent was obtained from all par-ticipants prior to data collection by way of verbal consent (written consent forms were considered but due to literacy issues not used). Assurances about the confidentiality of the data were given, as were assurances that no indi-vidual would be identifiable in any publication of the data. This was achieved by coding participant information on transcripts and anonymising data at the transcription stage. This involved transcribers removing any reference to individuals in the data and replacing names with a pseudonym. Participants were also made aware that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Data Collection

In depth interviews, lasting between 50 and 70 min were conducted in the participant’s home. Interviews were guided by an interview guide of open-ended questions and in-depth discussion. Open-open-ended questions were employed, such as “What were the reasons that made you decide to take care of the grand-child?”; “What did you experience in becoming the caregiver to your grandchild or grandchildren?”; “How does raising a grandchild affect your experiences in relation to your physical/emotional and social life?” and “Do you want to tell any stories about your raising experience that you have not already shared?’ The interviews were facilitated by members of the research team and were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. Data saturation was reached when there was repetition of information. In addition, field notes were taken during the interviews to help capture key issues.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were analyzed using Atlas V5.0 software to organize the data. Analysis applied the frameworks of Giorgi. The Giorgi’s phenomenological methods used were (a) the text was read to obtain a sense of the narrative as a whole; (b) meaning units were extracted from the texts; (c) these meaning units were examined individually and then collectively to gain a sense of, and comprehensively describe, the experience; (d) meaning units were

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

208

Table 1. Characteristics of Participants

Case Age Education Living status

B 63 Illiteracy Living with grandchildren

Hypertension 5 months 6-month-old girl Both parents were working

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011

jfn.sagepub.com

209

I 59 Illiteracy Living with husband and grandchild

Gastric ulcer 1 year and 1 month

K 57 Illiteracy Living with husband and grandchild

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011

jfn.sagepub.com

210

Case Age Education Living status

Health problem

Years of caregiving

Number of grandchildren

Rationale for caregiving

L 65 Illiteracy Living with grandchildren

4 years 4-year-old girl; 1-year-and- 11-month-old boy

Both parents were working

M 55 Elementary

school

Living with grandchild 1 year 1-year-old Both parents

were working

N 58 Elementary

school

Living with husband and grandchild

Hypertension 9 months 1-year-and-4-month-old boy

Both parents were working

O 55 Elementary

school

Living with other child and grandchild

2 years and 2 months

2-year-and-2-month-old boy

Both parents were working

Note: N = 15.

Table 1. (continued)

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011

jfn.sagepub.com

Chang and Hayter 211

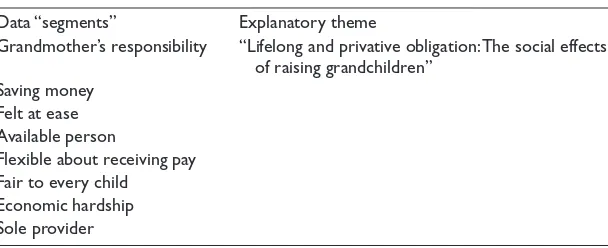

transformed into the language of science after the researcher’s reflection and imaginative variation; and, (e) specific structures were related to more gen-eral ones (Giorgi, 1985). This process led to the development of themes within which the data could be comfortably placed to provide a complete thematic description of the participants’ experiences. Table 2 provides an example of theme development by showing the data segments that ultimately formed the explanatory theme “Lifelong and privative obligation: The social effect of raising grandchildren.”

Researchers took several steps to ensure the trustworthiness of the find-ings, for example, piloting questions with two aboriginal grandmothers to ensure clarity, and involving aboriginal grandmothers’ experiences in the design of the study. This included the design of interview questions and help with publicizing the study and assistance with recruitment. In addition, data analysis was subject to internal review by members of the research team and also to peer review by two qualitative research scholars and nursing faculty members at the University of Taiwan—a procedure drawing on the qualita-tive research credibility work of Lincoln and Guba (1985).

Findings

Four themes emerged from the data analysis that encompassed the grand-mothers’ caregiving experiences of the participants. They were as follows: Using aged bodies to do energetic work: The physical effects of raising grandchildren; Conflicting emotions: The psychological effects of raising grandchildren; Lifelong and privative obligation: The social effects of rais-ing grandchildren; and Coprais-ing strategies for raisrais-ing grandchildren. The

Table 2. Structure of “Lifelong and Privative Obligation” Theme

Data “segments” Explanatory theme

Grandmother’s responsibility “Lifelong and privative obligation: The social effects of raising grandchildren”

Saving money Felt at ease Available person

Flexible about receiving pay Fair to every child

Economic hardship Sole provider

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

212 Journal of Family Nursing17(2)

following sections use representative examples of data to illustrate the themes in more detail.

Using Aged Bodies to Do Energetic Work:

The Physical Effects of Raising Grandchildren

Most grandmothers described how changes they associated with aging cre-ated parenting challenges. Health problems and limited energy made it difficult for grandmothers to take care of their grandchildren. Grandmother caregivers in this study expressed feelings of fatigue when using their aged bodies to raise energetic grandkids:

D: Sometimes I feel my hands are powerless, because I’m old. When I give my granddaughter a bath, I worry if she will slip in the bath-tub because my hands are powerless.

H: I have had hypertension and diabetes for more than twenty years. One year ago I had a stroke (pointing to her left face). Now, I still cannot speak very fluently. I have those illnesses, and sometimes I get so sick that, when I want to hold my grandson, I cannot. K: When I first took care of my children, I felt okay, because I was

younger. At this time, I’m older, and I feel tired when raising my grandson.

When raising their grandchildren, some grandmothers had to work, in addition to doing all of the housework necessary to meet their families’ needs. Furthermore, the very energetic nature of young children also placed physi-cal demands on grandmothers with the constant care required by younger grand-children increasing the grandmother’s daily tasks:

A: Raising two grandchildren makes me feel tired, especially when I need to clean the house, cook, and wash all of the clothing. M: My grandson is very selfish. He puts everything that he finds into

his mouth. He grabs everything, I tell you. He likes to open the wardrobe, and toss around all the clothing that I have folded. H: I must take care of my mother who is 83 years old and my

young-est daughter who is handicapped. At the same time, I have my own business; I pack betel nuts for sale and manage a small grocery store. My grandson is very energetic; he likes to climb up and down on things, and go outside. I must watch over him very carefully.

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

Chang and Hayter 213

Conflicting Emotions: The Psychological

Effects of Raising Grandchildren

Grandmothers’ love and concern for their grandchildren was a dominant subcategory and an emotional issue. The love and concern caused the grand-mothers to feel that they could not leave their grandchildren. In this study, all of the grandmothers had raised their grandchildren since infancy. They watched their grandchildren grow up day by day. Every grandmother told of happiness, pride, and satisfaction from the years spent raising grandchildren. In addition, grandmothers described an intense emotional bond with their grandchildren that felt equivalent to their emotional bond to their children:

A: I felt satisfaction and pride as my grandchildren grew up. Now, they want to be together with me more than with their father and mother. They know they are their parents, but they don’t want to spend time with them. I have sentiments with them. They are my grandchildren; I cannot leave them yet.

J: I told you, I must see my granddaughters everyday. If I cannot see my granddaughters one day, I miss them and cry. Raising them makes me feel happy. They haven’t a real mom; I am their mom. I equal their mom. Because they haven’t a true mother’s love, I am to be their mother love until they attain womanhood, or until I die.

However, most of grandmothers agreed that it is a burden for them to take care of their grandchildren. They felt concerned and worried about their grandchildren’s health. Four grandmothers shared their experiences with having their grandchildren hospitalized. When the child was sick, they wor-ried the child’s parent may blame them for not taking better care of the grandchild, because they have committed themselves to their child in accept-ing responsibility for raisaccept-ing the grandchild:

C: I am afraid of times when he gets sick, such as having a cold, diar-rhea, or an injury. All of those make me afraid. If he gets sick, I worry that my daughter-in-law or my son will say something. I worry about that in my mind. You can’t prevent yourself from thinking about it.

B: When I raise my grandchildren, I am worried about criticism, because I don’t want my child to say that my grandchild became sick because I didn’t take good care of him.

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

214 Journal of Family Nursing17(2)

M: My husband comes back every Monday. I ask him to drive the car, and take my grandson and me to the doctor, even if he seems OK, because I worry so much about his health. I worry whenever he has even some slight symptoms of illness.

Lifelong and Privative Obligation: The Social

Effects of Raising Grandchildren

In this study, most of grandmothers raised their grandchildren because the mother and father of the child were working full time, they did not want the grandchild to go to a babysitter’s home, and/or they wanted to financially assist the parents of the child. Therefore, some grandmothers raised their grandkids because they believed they had a responsibility to do so. Some grandmothers saw themselves as the grandchild’s only resource, as being the only relative willing to come to the aid of the grandchild and accept the role of primary caregiver:

C: If I didn’t raise my grandson, I could not live with my conscience. He is my grandson; I think my raising him is better than having oth-ers do it. Another reason is that my son earns very little salary. I raise my grandson rather than taking him to a babysitter and pay the bab-ysitter’s fee. I really think of that.

G: When he was born, his biological father disappeared. My daughter did not marry him. I felt my grandson was so pitiful, with no one to take care of him. If no one raised him, I do not know where he would stay.

Some grandmothers spoke of their long-term experience about the care of the grandchild, and the major reason they must be fair to every child. Once grandmother promised to take care of an elder child’s offspring, it would be unfair to say no to raising a younger child’s offspring. Therefore, some of grandmothers raised their grandchildren one by one—feeling obliged to do this:

D: Before this child, I already raised one, two, three, . . . three kids. This is the youngest. I raised my son’s and my daughter’s kids. I took care of her (gesturing towards a girl who sits on the sofa) from 4 months of age until she entered elementary school, and she is my daughter’s kid. I think I must be fair. If not, my daughter-in-law may say I am unfair.

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

Chang and Hayter 215

Another significant issue for participants was a lack of support in child care. They must raise their grandchild full-time and by themselves.

B: I raised 4 grandchildren by myself. Sometimes I feel very tired. I say I don’t want to raise them, but who else can raise them?

E: I raised them when they were born, watched them 24 hours, and took them to see the doctor. Every time they were hospitalized, they cried at the night while in the hospital, I must stay in the hospital to take care of them, and I cannot sleep for the whole night.

Most of grandmothers received little financial help from their own chil-dren for child care. Some grandmothers did receive payments—but often in limited amounts. Some grandmothers suffered from economic stress brought about by parenting requirements. However, the attitude toward this was mixed. Some participants did not mind receiving payments—others were less accommodating and reported financial strain more clearly:

M: There have been many years . . . almost eight years when I did not earn money. In those years, I only raised my grandkids. I don’t care how much money she (daughter) pays me for child care. I only ask her to subsidize the water and electricity fees.

G: We’ve paid everything after he was born. My daughter had a tem-porary job for a period; at that time she gave me some money for child care. Then she didn’t have a job; so nothing was paid. My husband is handicapped. I need to raise my children and my grandson, so I cannot go to work. Now, we received government assistance to live.

Coping Strategies for Raising Grandchildren

Common coping strategies that grandmothers used in raising grand-children were as follows: doing housework while the grandgrand-children sleep, adjusting child care method, saving money whenever possible, and hoping their grandchildren grow up quickly. In our interviews, grand-mothers’ narrative responses told how they arranged their daily life to finish housework:

M: When he sleeps, I sleep with him. And, when he wakes up, I also wake up. He usually sleeps at twelve o’clock and I wash clothing at that time.

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

216 Journal of Family Nursing17(2)

E: I go to farm in the early morning when they are still sleeping. I will come back at eight o’clock, and they usually wake up at about nine o’clock.

Some of the grandmothers were aged and had chronic illnesses. When they felt limited energy or became sick, they adjusted their child care methods, for example, washing the feeding bottle instead of disinfecting it in boiling water, or letting a child play freely on the ground. However, some grand-mothers’ health problems and lack of energy influenced their grandchildren’s daily care:

H: When I took care of my children, I never put them on the ground. But now, I’m old, and feel limited energy and less vitality. I put my grandson on the ground so that he can do some activities. I feel it is ok if he gets dirty; I will give him a bath later at night.

D: Sometimes, I feel very tired. I wash her feeding bottle with running water. I don’t use boiling water to boil it all the time. Now she is five months old. It’s OK, right?

One issue of note was how the grandmothers reacted to their financial strain. Six of the 15 participating grandmothers either had to rely on others or could barely meet their basic needs on their own. Therefore, they tried to skimp on their overall and daily expenditures, including health care fee, adequate housing, and adequate food:

H: I have stroke and need to go to the hospital for rehabilitation. But, I haven’t the money. I only went to hospital two or three times. I choose to stay at home and rehabilitate by myself.

G: When he was 2 months old, I start to feed him porridge, infant milk power is too expensive. Now he is more than 1 year old, and has grown very well.

Grandmothers talked about their feelings of lifelong obligation in raising grandchildren. Although, grandmothers love and enjoy taking care of their grand-children, all of the grandmothers were still anticipating their grandchildren grow-ing up quickly, so that they can receive a break from the full-time obligation:

C: When my granddaughter becomes 5 years old, she can study in kin-dergarten. Then, I only have to take care of my grandson. I think it will be better.

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

Chang and Hayter 217

M: I raised all of my grandkids until they were 3 years old. Now, this one is only 1 year old. Two years later my daughter will take him back, then I can earn money.

Discussion

This phenomenological study revealed aboriginal grandmothers’ experi-ences of raising grandchildren. The findings address a growing social phe-nomenon in Taiwan and provide preliminary insights in terms of why grandmothers assume the role of raising of their grandchildren and its effects on their lives. In this study, the physical effects of parenting was certainly an issue, something that certainly parallels other work from other cultures. Similar physical health issues are described in the work of Minkler and Fuller-Thomson (1999) and Dolbin-MacNab (2006) from a broad number of ethnic and social groups and the data in this study appears to add to this. These reports of physical health impact also appears to challenge the work of Hughes et al. (2007) and Musil (1998) who found little impact on physical health amongst White parenting grandparents. However, it could well be argued that there is variability in this respect and that while this sample of Taiwanese grandmothers certainly did identify the physical effects of parent-ing as a problem another group may not—an issue which concurs with Butler and Zakari’s (2005) analysis that physical impact varies in intensity.

Interestingly, from a cultural perspective, Pruchno and McKenny (2002), who studied both Black and White families in the United States, argue that the strength of a cultural sense of responsibility may mitigate against the expressions of health problems by grandparents. This aspect, given the strength of parenting attitudes in Taiwan, did not seem to effect the reporting of physical problems—but it may have affected how strongly they were emphasized. Nevertheless, the impact on physical health (or potential impact) does seem to be a cross-cultural phenomenon and as such should clearly be recognized by health care professionals. Although the results were insuffi-cient in clarifying how grandmothers’ poor health influenced the quality of child care, or how caregiving influenced grandmothers’ health, they did sug-gest a lack of perception or acknowledgment by some participants that such effects could exist—supporting prior research that indicates grandmothers’ roles may make it difficult for them to provide effective or safe grandchild care (Reschke, Manoogian, Richards, Walker, & Seiling, 2006).

The findings of this research demonstrate that being a grandmother and a primary caregiver to young grandchildren generates conflicting emotions. Despite the physical and emotional strains, almost all of the aboriginal

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

218 Journal of Family Nursing17(2)

grandmothers who were raising their grandchildren said they had grown closer to the grandchild since they began providing full-time care; they were grateful to have the children living with them and could not imagine life without them now. This is certainly an interesting finding and seems to per-petuate a theme found in other cultural studies of parenting by grandparents (Orb & Davey, 2005). For example, Cox, Brooks, and Valcarel (2000) describe similar mixed emotions in amongst Latino grandparents in the United States and Hayslip and Goodman (2008) among Mexican grandparents. It seems, therefore, that there is often a fine balance between reward and loss in this aspect of family life. However, it may be also linked to feelings of guilt and a sense of having to take responsibility that leads grandparents to profess benefits too—as a way of justifying their role to themselves as suggested by the work of Minkler, Fuller-Thompson, Miller, and Driver (1997).

Another aspect was the concern expressed by grandmothers that their “performance” as a parent would be judged by others—including their own siblings. This might be due to these aboriginal grandmothers’ strong identifi-cation with the parental role, and/or because they have never really left behind this role (Dolbin-MacNab, 2006). It is also possible that these aborigi-nal grandmothers had attributed their obligation to the cultural expectations that a grandmother is the most reliable surrogate mother in cases when there has been a divorce, a teenage pregnancy, or when both parents have to work (Chia & Chen, 1999). This sense of obligation has been reported in other cultural research with grandparents such as Cox et al. (2000), Hayslip and Goodman (2008), and Musil (1998) all of whom report that grandparents have a strong sense of duty in respect to facilitating the parenting role.

Therefore, even though the Taiwanese aboriginal grandmothers in this study may be committed to looking after their children, their parenting roles are not always gratifying. Parenting the children has become a burden that some of the grandmothers had to live with. In addition, they expressed concern about the appraisals from their own child and worries about their grandchildren’s health. These pressures clearly influence the grandmothers’ physical and psychologi-cal well-being. Accordingly, as numerous authors note, health professionals need to be ready to provide appropriate support for individuals in this type of situation (Butler & Zakari, 2005; Fitzpatrick & Reeve, 2003; Minkler & Fuller-Thomson, 1999; Sands & Goldberg-Glenn, 2000).

Limitations

This was a relatively small, exploratory, qualitative study. The main limita-tion of the study is that these results are based on the lived experiences of the

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

Chang and Hayter 219

grandmothers alone. Although designed to capture the views of grandmoth-ers, future studies would be useful to collect data from other family mem-bers, including children. In addition, in terms of qualitative rigor, member checking could have reinforced the findings, but this was not possible due to time constraints.

Implications for Practice

In this study, most of the grandmothers perceived raising grandchildren and helping children as a lifelong obligation. Because of the strong motivation to support their children, grandmothers insisted on continuing to provide care, even when their own physical health might suffer or their own needs and desires took second place (Fingerman, 1996). In addition, no matter how much or how little money the child paid to the grandmother for child care, most grandmothers did not overtly complain about a lack of financial support even though there were some grandmothers that reported significant financial problems, necessitating the curtailment of their own health care needs. Therefore, recognition of the special and unique issues faced by full-time grandmother caregivers is important for health care providers, particularly those who may frequently interact with multigenerational families. The experiences of the grandmothers in this study demonstrate how important it is to understand the differences grandmothers have in their experience as they raised their grand-child. Health care providers in many clinical settings deal with grandmother caregivers, and it is important that they understand the living conditions and stress experienced by grandmother caregivers. Using the results of this study, health care providers can obtain a greater awareness of the existence of, or potential development of, health problems in aboriginal grandmother caregivers. They can provide aboriginal grandmother caregivers with more information on current child-rearing practices, child-development characteristics, emotional support, and safety tips. This study also demonstrates how health care provid-ers need to monitor and manage the considerable physical and emotional strain of parenting grandmothers.

Conclusion

From the findings of this study it is clear that even though aboriginal grand-mothers in Taiwan desire to have healthy relationships with their grandchil-dren, and to help their own chilgrandchil-dren, they may also experience conflict when they endure poor health, limited energy levels, and economic pressures. The findings provide some insights for continued research into this growing

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

220 Journal of Family Nursing17(2)

phenomenon, and can begin to challenge health care providers to consider the needs and issues of grandmothers who take on this difficult task of parenting.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publica-tion of this article.

References

Bowers, B. F., & Myers, B. J. (1999). Grandmothers providing care for grandchildren: Consequences of various levels of care-giving. Family Relations, 48, 303-311. Butler, F. R., & Zakari, N. (2005). Grandparents parenting grandchildren: Assessing

health status, parental stress, and social supports. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 31(3), 43-54.

Chang, S. Y. (2008). The study on grandparenting families. Comptroller Monthly, 631, 54-61.

Chen, L. H., Weng, F. Y., Hsu, W. S., & Lin, C. C. (2000). An analytical study on grandparenting families in Taiwan (2). Journal of Education, 4, 51-66.

Chi, S. M., & Huang, Y. T. (2006). Surrogate parents: The study on health status of grandparents raising grandchildren. Journal of Living Science, 10, 243-264. Chia, H. F., & Chen, P. H. (1999). The decision process of grandparents’ nurturing

the grandchildren—Using the perspective of structural family therapy. Bulletin of Educational Psychology, 31(1), 109-137.

Chiu, J. (2004). The strengths of grandparenting—A case study. Journal of National University Taiwan: Education, 38(2), 33-44.

Council of Indigenous Peoples. (2009). Demographic data of aboriginal population. Retrieved from http://www.apc.gov.tw/main/docDetail/detail_TCA.jsp?isSearch

=&docid=PA000000003194&cateID=A000297&linkSelf=161&linkRoot=4&lin kParent=49&url=

Cox, C. B., Brooks, L. R., & Valcarel, C. (2000). Culture and caregiving: A study of Latino grandparents. In C. B. Cox (Ed.), To grandmother’s house we go and stay: Perspectives on custodial grandparents (pp. 218-232). New York, NY: Springer. The Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics. (2010). Transi-tion within family type. Retrieved from http://www.stat.gov.tw/public/Data/ 071617231971.pdf

Dolbin-MacNab, M. L. (2006). Just like raising your own? Grandmothers’ percep-tions of parenting a second time around. Family Relations, 55, 564-575.

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

Chang and Hayter 221

Dowdell, E. B. (2004). Grandmother caregivers and caregiver burden. American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 29, 299-304.

Fingerman, K. L. (1996). Sources of tension in the aging mother and adult daughter relationship. Psychology and Aging, 11, 591-606.

Fitzpatrick, M., & Reeve, P. (2003). Grandparents’ raising grandchildren—A new class of disadvantaged Australians. Family Matters, 66, 54-57.

Fuller-Thomson, E., & Minkler, M. (2005). American Indian/Alaskan Native grand-parents raising grandchildren: Findings from the Census 2000 Supplementary Survey. Social Work, 50(2), 131-139.

Giorgi, A. (1997). The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research procedure. Journal of Phenomenological Psy-chology, 28, 235-260.

Giorgi, A. (2005). The phenomenological movement and research in the human sciences. Nursing Science Quarterly, 18(1), 75-82.

Hayslip, B., & Goodman, C. C. (2008). Grandparents raising grandchildren: Benefits and drawbacks. Journal of Inter-generational Relationships, 5(4), 117-119. Hsu, S. W., & Cheng, S. T. (2007). The role and satisfaction of grandparenting

prac-tice. Journal of Taiwan Home Economics, 41, 51-68.

Hualien County Government. (2009). Demographic data of Hualien city. Retrieved from http://web.hl.gov.tw/static/population/pop_table/9805.xls

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., LaPierre, T. A., & Luo, Y. (2007). All in the family: The impact of caring for grandchildren on grandparents’ health. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 62(2), 108-119.

Kataoka-Yahiro, M., Ceria, C., & Caulfield, R. (2004). Grandparent caregiving role in ethnically diverse families. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 19, 315-328.

Kleiman, S. (2004). Phenomenology: To wonder and search for meanings. Nurse Researcher, 11(4), 7-19.

Leder, S. Grinstead, L. N., & Torres, E. (2007). Grandparents raising grandchildren: Stressors, social support, and health outcomes. Journal of Family Nursing, 13, 333-352. Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE. Minkler, M., & Fuller-Thomson, E. (1999). The health of grandparents raising

grand-children: Results of a national study. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 1384-1389.

Minkler, M., & Fuller-Thomson, E. (2005). African American grandparents raising grandchildren: A national study using the Census 2000 American Community Survey. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 60(2), S82-S92.

Minkler, M., Fuller-Thompson, E., Miller, D., & Driver, D. (1997). Depression in grandparents raising grandchildren: Results of a national longitudinal study.

Archives of Family Medicine, 6, 445-452.

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

222 Journal of Family Nursing17(2)

Musil, C. M. (1998). Health, stress, coping, and social support in grandmother care-givers. Health Care for Women International, 19, 441-455.

Orb, A., & Davey, M. (2005). Grandparents parenting their grandchildren. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 24, 162-168.

Pruchno, R. A., & McKenny, D. (2002). Psychological well-being of Black and White grandmothers raising grandchildren: Examination of a two-factor model. Journal of Gerontology, 57, 444-452.

Reschke, K. L., Manoogian, M. M., Richards, L. N., Walker, S. K., & Seiling, S. B. (2006). Maternal grandmothers as child care providers for rural, low-income mothers. Journal of Children & Poverty, 12(2), 159-174.

Ruiz, D. S. (2002). The increase in incarcerations among women and its impact on the grandmother caregiver: Some racial considerations. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 29, 179-197.

Sands, R. G., & Goldberg-Glenn, R. S. (2000). Factors associated with stress among grandparents raising their grandchildren. Family Relations, 49(1), 97-105. Thupayagale-Tshweneagae, G. (2008). Psychosocial effects experienced by

grand-mothers as primary caregivers in rural Botswana. Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing, 15, 351-356.

Tsai, Y. C., & Lue, T. (2006). The relation between grandparents’ parenting involve-ment and children’s social-emotional behavior. Journal of Study in Child and Education, 2, 43-84.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2009). U.S. Census Bureau News—Facts for features: Grand-parents day 2009. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/pdf/ cb09-ff16.pdf

Waldrop, D. P. (2003). Caregiving issues for grandmothers raising their grand-children. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 7(3-4), 201-223. Whitley, D. M., Kelley, S. J., & Sipe, T. A. (2001). Grandmothers raising grandchildren:

Are they at increased risk of health problems? Health & Social Work, 26(2), 105-114. Williamson, J., Softas-Nall, B., & Miller, J. (2003). Grandmothers raising grand-children: An exploration of their experiences and emotions. The Family Journal 11(1), 23-32.

Bios

Yu-Ting Chang, RN, MSN, in an instructor in the Department of Nursing, Tzu Chi College of Technology in Taiwan. Her research interests relate mainly to children health care and adolescent sexual health. Her recent publications include “A systematic review and meta-ethnography of the qualitative literature: Experiences of the menarche” in

Journal of Clinical Nursing (2010, with M. Hayter & S. C. Wu) and “Experiences of sexual harassment among elementary school students in Taiwan: Implications for school nurses” in Journal of School Nursing (2010, with M. Hayter & M. L. Lin).

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com

Chang and Hayter 223

Mark Hayter, PhD, RN, MSc, BA (Hons), is a reader in nursing, Center for Health and Social Care Studies and Service Development, School of Nursing and Midwifery, at the University of Sheffield, United Kingdom. He has had a sustained interest in adolescent health research, in particular, factors that influence adolescent risk taking behavior and the underlying social factors. His clinical interests relate mainly to adolescent sexual health. His recent publications include “Experiences of sexual harassment among elementary school students in Taiwan: Implications for school nurses” in Journal of School Nursing (2010, with Y. T. Chang, & M. L. Lin) and “School-linked sexual health services for young people (SSHYP): A survey and systematic review concerning current models, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and research opportunities” in Health Technology Assessment (2010, with J. Owen, C. Carroll, J. Cooke, E. Formby, J. Hirst, . . . A. Sutton).

at University of Sheffield on June 24, 2011 jfn.sagepub.com