AN ANALYSIS OF CONTEXT OF SITUATION IN OSCAR WILDE’S SHORT STORY “THE NIGHTINGALE AND THE ROSE”

A THESIS

BY

MENTARI FITRI ANNISA REG. NO. 120721004

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA

i AN ANALYSIS OF CONTEXT OF SITUATION IN OSCAR WILDE’S SHORT STORY “THE NIGHTINGALE AND THE ROSE”

A THESIS

BY

MENTARI FITRI ANNISA REG. NO. 120721004

SUPERVISOR CO-SUPERVISOR

Dr. Hj. Masdiana Lubis, M.Hum. Dr. Hj. Nurlela, M.Hum.

Submitted to Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Medan in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra from Department of English

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA

ii Approved by the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara (USU) Medan as thesis for The Sarjana Sastra Examination.

Head, Secretary,

iii Accepted by the Board of Examiners in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra from the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara, Medan.

The examination is held in Department of English Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara on 10 February 2015.

Dean of Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara

Dr. H. Syahron Lubis, M.A. NIP. 19511013 197603 1 001

Board of Examiners:

(Names) (Signatures)

1. __________

2. __________

3. __________

4. __________

iv AUTHOR’S DECLARATION

I AM, MENTARI FITRI ANNISA, DECLARE THAT I AM THE SOLE AUTHOR OF THIS THESIS EXCEPT WHERE REFERENCE IS MADE IN THE TEXT OF THIS THESIS. THIS THESIS CONTAINS NO MATERIAL PUBLISHED ELSEWHERE OR EXTRACTED IN WHOLE OR IN PART FROM A THESIS BY WHICH I HAVE QUALIFIED FOR OR AWARDED ANOTHER DEGREE. NO OTHER PERSON’S WORK HAS BEEN USED WITHOUT DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS IN THE MAIN TEXT OF THIS THESIS. THIS THESIS HAS NOT BEEN SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OR ANOTHER DEGREE IN ANY TERTIARY EDUCATION.

Signed :

v COPYRIGHT DECLARATION

NAME : MENTARI FITRI ANNISA

TITLE OF THESIS : AN ANALYSIS OF CONTEXT OF SITUATION IN OSCAR WILDE’S SHORT STORY “THE NIGHTINGALE AND THE ROSE”

QUALIFICATION : S-1/SARJANA SASTRA

DEPARTMENT : ENGLISH

I AM WILLING THAT MY THESIS SHOULD BE AVAILABLE FOR REPRODUCTION AT THE DISCRETION OF THE LIBRARIAN OF DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH, FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA ON THE UNDERSTANDING THAT USERS ARE MADE AWARE OF THEIR OBLIGATION UNDER THE LAW OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA.

Signed :

vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, I would like to thank and praise the Almighty God, Allah SWT, for the blessing and for giving me health, strength and ease to accomplish this thesis as one of the requirements to get the degree of Sarjana Sastra from Department of English Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara (USU), Medan.

Then, I would like to express a deep love, gratitude and appreciation to: • My mother, Erma Yona, my father, Syafrizal and my stepmother, Nida.

Thank you for the gens, loves, supports, prayers and finances.

• My grandmother, Erry Marina; my aunts, Ellen Yulia, Emma Yunita and Wati; and my uncles, M. Isnaini and Bob. Thank you for the loves, prayers, supports and tips.

• My brothers, M. Fikri Al Hakim and M. Fitryan Al Fajri; my stepbrothers, Bayu and Agung; and my half-brother, M. Fadhillah Al Hafiz; and my sister, Nita. Thank you for the loves, prayers, supports and company.

• My cousins, Casey Nurul Falisha, Naema Aira Falisha and M. Mirza Izz Faeyza; and my niece, Alya Khaleesi Hakim.

• My supervisor, Dr. Hj. Masdiana Lubis, M.Hum. and co-supervisor Dr. Hj. Nurlela, M.Hum. Thank you for the valuable times and patience in giving the correction and constructive critics in completing this thesis. • The Head of Department of English, Dr. H. Muhizar Muchtar, M.S. and

vii • The Board of Examiners. Thank you for the valuable times and patience in

examining this thesis.

• The Dean of Faculty of Cultural Studies, University of Sumatera Utara. Dr.

H. Syahron Lubis, M.A.

• My lecturers in Department of English. Thank you for the knowledge,

advices and pointers. • My seniors and juniors.

• My friends, Nazlia Putri, Ressa Elfiani, Kiswanda Wulan Ningsih, Nurhayati, Cut Surita Dessy, Astriah, Merisa, Mahyar Diyanti, Mulia Wati Is, Ayu Juanda, Karya Dewi Andiena, Risma Dewi, Dasmara Sukma, Dina Santi Lestari, Meli Astuti, Miftahul Khairi, Rachmi, Juwita Ulandari Saragih, Dessy Purnama Wati Tampubolon, Jenni P. Nababan and many more. Thank you for the loves, supports, jokes and friendship.

Furthermore, I wanted to thank all of the authors and writers of articles, journals and books that I used for this thesis. And finally, thank you for everyone above and anyone else I forgot to mention, for without them I would not be able to finish this thesis.

Medan, 10 February 2015 The writer,

viii ABSTRACT

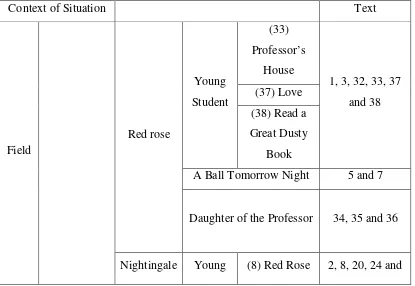

This thesis entitled “An Analysis of Context of Situation in Oscar Wilde’s Short Story ‘The Nightingale and the Rose’” discussed about the context of situation in Oscar Wilde’s Short Story “The Nightingale and the Rose”. The problem of this thesis is to know about the field, tenor and mode in the short story, and the objective is to find out about it order to understand the use of language in the short story. The research method applied is qualitative research method and the theory used in analysing the short story is the theory of context of situation by Halliday (1978). In analysing the 38 texts of Oscar Wilde’s Short Story “The Nightingale and the Rose”, writer found two main fields (topics) are Red Rose and Nightingale. The field Red Rose is supported with three sub-fields, they are Young Student, A Ball Tomorrow Night and Daughter of the Professor. While, the field Nightingale is supported with seven sub-fields, they are Young Student, True Lover, Mystery of Love, Soaring into the Air, Rose-tree, Oak-tree and Sing All Night Long. Then, there are ten tenors (participants), they are the Young Student, Nightingale, Little Green Lizard, Butterfly, Daisy, White Rose-tree, Yellow Rose-tree, Red Rose-tree, Oak-tree and Daughter of the Professor. Then, the roles of language were reflection and action, and the language was written as monologues, dialogues and on-going action.

ix ABSTRAK

Tesis yang berjudul “An Analysis of Context of Situation in Oscar Wilde’s Short Story ‘The Nightingale and the Rose’” membahas tentang konteks situasi di cerpen “The Nightingale and the Rose” yang ditulis oleh Oscar Wilde. Masalah tesis ini adalah untuk mengetahui tentang medan, pelibat dan sarana di cerpen tersebut, dan tujuannya adalah untuk mencaritahunya untuk memahami penggunaan bahasa di cerpen tersebut. Metode penelitian yang digunakan adalah metode penelitian kualitatif dan teori yang digunakan untuk menganalisa cerpen tersebut adalah teori konteks situasi dari Halliday (1978). Dalam menganalisa 38 teks-teks “The Nightingale and the Rose” yang ditulis oleh Oscar Wilde tersebut, penulis menemukan dua medan (topik) utama yaitu Mawar Merah dan Burung Bulbul. Medan Mawar Merah didukung oleh tiga sub-medan, yaitu Pelajar Muda, Pesta Dansa Besok Malam dan Putri Profesor. Sedangkan, medan Burung Bulbul didukung oleh tujuh sub-medan, yaitu Pelajar Muda, Kekasih Sejati, Misteri Cinta, Membumbung ke Langit, Pohon Mawar, Pohon Ek dan Menyanyi Sepanjang Malam. Kemudian, ada sepuluh pelibat (partisipan), yaitu Pelajar muda, Burung Bulbul, Kadal Hijau kecil, Kupu-kupu, bunga Aster, Pohon Mawar Putih, Pohon Mawar Kuning, Pohon Mawar Merah, Pohon Ek dan Putri Profesor. Kemudian, peran bahasa adalah refleksi dan aksi, dan bahasa ditulis sebagai monolog, dialog, dan aksi yang sedang berjalan.

x TABLE OF CONTENTS

SUPERVISOR’S APPROVAL SHEET ... i

DEPARTMENT’S APPROVAL SHEET ... ii

BOARD OF EXAMINERS’ APPROVAL ... iii

AUTHOR’S DECLARATION ... iv

COPYRIGHT DECLARATION ... v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... vi

ABSTRACT ... viii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... x

CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1.1Background of the Study ... 1

1.2Problem of the Study ... 6

1.3Objective of the Study ... 7

1.4Scope of the Study ... 7

1.5Significance of the Study ... 7

CHAPTER II. REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE 2.1 Context of Situation: Register Theory ... 9

2.2Relevance Studies ... 27

CHAPTER III. METHOD OF RESEARCH 2.3Research Design ... 30

2.4Data and Sources of Data ... 30

2.5Data Collection Method ... 30

2.6Data Analysis Method ... 31

CHAPTER IV. ANALYSIS AND FINDING 2.7Data Analysis ... 32

2.8Findings and Discussion ... 52

CHAPTER V. CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTION 2.9Conclusion ... 60

2.10 Sugestion ... 61

REFERENCES ... 62

viii ABSTRACT

This thesis entitled “An Analysis of Context of Situation in Oscar Wilde’s Short Story ‘The Nightingale and the Rose’” discussed about the context of situation in Oscar Wilde’s Short Story “The Nightingale and the Rose”. The problem of this thesis is to know about the field, tenor and mode in the short story, and the objective is to find out about it order to understand the use of language in the short story. The research method applied is qualitative research method and the theory used in analysing the short story is the theory of context of situation by Halliday (1978). In analysing the 38 texts of Oscar Wilde’s Short Story “The Nightingale and the Rose”, writer found two main fields (topics) are Red Rose and Nightingale. The field Red Rose is supported with three sub-fields, they are Young Student, A Ball Tomorrow Night and Daughter of the Professor. While, the field Nightingale is supported with seven sub-fields, they are Young Student, True Lover, Mystery of Love, Soaring into the Air, Rose-tree, Oak-tree and Sing All Night Long. Then, there are ten tenors (participants), they are the Young Student, Nightingale, Little Green Lizard, Butterfly, Daisy, White Rose-tree, Yellow Rose-tree, Red Rose-tree, Oak-tree and Daughter of the Professor. Then, the roles of language were reflection and action, and the language was written as monologues, dialogues and on-going action.

ix ABSTRAK

Tesis yang berjudul “An Analysis of Context of Situation in Oscar Wilde’s Short Story ‘The Nightingale and the Rose’” membahas tentang konteks situasi di cerpen “The Nightingale and the Rose” yang ditulis oleh Oscar Wilde. Masalah tesis ini adalah untuk mengetahui tentang medan, pelibat dan sarana di cerpen tersebut, dan tujuannya adalah untuk mencaritahunya untuk memahami penggunaan bahasa di cerpen tersebut. Metode penelitian yang digunakan adalah metode penelitian kualitatif dan teori yang digunakan untuk menganalisa cerpen tersebut adalah teori konteks situasi dari Halliday (1978). Dalam menganalisa 38 teks-teks “The Nightingale and the Rose” yang ditulis oleh Oscar Wilde tersebut, penulis menemukan dua medan (topik) utama yaitu Mawar Merah dan Burung Bulbul. Medan Mawar Merah didukung oleh tiga sub-medan, yaitu Pelajar Muda, Pesta Dansa Besok Malam dan Putri Profesor. Sedangkan, medan Burung Bulbul didukung oleh tujuh sub-medan, yaitu Pelajar Muda, Kekasih Sejati, Misteri Cinta, Membumbung ke Langit, Pohon Mawar, Pohon Ek dan Menyanyi Sepanjang Malam. Kemudian, ada sepuluh pelibat (partisipan), yaitu Pelajar muda, Burung Bulbul, Kadal Hijau kecil, Kupu-kupu, bunga Aster, Pohon Mawar Putih, Pohon Mawar Kuning, Pohon Mawar Merah, Pohon Ek dan Putri Profesor. Kemudian, peran bahasa adalah refleksi dan aksi, dan bahasa ditulis sebagai monolog, dialog, dan aksi yang sedang berjalan.

1 CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

1.1Background of the Study

Language used in conversation contains meaning, form and expression. As Halliday said that language is interpreted as a system of forms to which meanings are then attached (Halliday, 1985: XIV). Furthermore, language is functional, so study of language form alone cannot fully explain systematic language use. Language use, though unique, can be explored, and linguistic elements and specific language events can be systematically examined from a functional point of view. In short, we ‘make meaning’ through our choice and use of words, and systematic study of language in use is how we make sense of our meaning (Gerot, 1994: V-VI).

Meaning of language used can be interpreted within its context. The term of context had been purposed by Malinowski (1923/46, 1935), as it is stated in Eggin’s book, language only makes sense (only has meaning) when interpreted within its context (Eggins, 1994: 50-51).

There is different description towards the word context. In Song’s journal, Widdowson (2000: 126), when focusing his study on language meaning, thought “context” as “those aspects of the circumstance of actual language use which are taken as relevant to meaning.” While according to Yule (2000: 128), “Context is the physical environment in which a word is used.” These definitions have an important point in common: one main point of the context is the environment (circumstances or factors) in which a discourse occurs (Song, 2010: 876).

2 characteristics of the text (language) (Sinar, 2003: 54). But, for this study, the writer only focuses on context of situation.

In Sinar’s book, Malinowski also said that language is “context-dependent” which means the speech and the situation that is strictly tied to each other and the context of the situation is really necessary to understand the words. Then, Malinowski (1946: 307) and Firth (1957) said that language is the expression of social behavior in contexts: the meaning of each word in a certain level is dependent on the context (Sinar, 2003: 23).

In Eggin’s book, Malinowski stated that meanings depends on context because he claimed that language only becomes intelligible when it is placed within its context of situation. Then, the notion of context of situation was extended by J.R. Firth (1935, 1950, 1951), he pointed out that when a description of a context is given, we can predict what language will be used. His rather quaint but exact formulation of this was to claim that learning to use language is very much a process of learning to say what the other fellow expects us to say under the given circumstances.... Once someone speaks to you, you are in a relatively determined context and you are not free just to say what you please (Eggins, 1994: 50-51).

In Hu’s journal, Halliday proposed the concept of context consists of three strata: context of culture, context of situation and co-text. Context of culture and context of situation are outside of language itself. Co-text, also known as linguistic context, is certainly inside of language itself. There is a close interdependent relationship between language and context. Context determines and is constructed by the choice of language. On the one hand, language, when considered as a system--its lexical items and grammatical categories—is related to its context of culture. While on the other hand, the specific text and its component parts are related to its context of situation. To be specific, context of culture is related to genre, context of situation is related to register, and co-text to the discourse itself (Hu, 2010: 324).

3 Situational context, or context of situation, refers to the environment, time and place, etc. in which the discourse occurs, and also the relationship between the participants. Cultural context refers to the culture, customs and background of epoch in language communities in which the speakers participate. Language is a social phenomenon, and it is closely tied up with the social structure and value system of society. Therefore, language can not avoid being influenced by all these factors like social role, social status, sex and age (Song, 2010: 876-877).

Context of situation consists of three aspects: field, tenor and mode. Field refers to what is happening, to the nature of social action that is taking place. It answers such questions as what it is that the participant is engaged in. Tenor refers to who is taking part, to the nature of the participants, their status and roles: what kind of role relationship obtain among the participants, including permanent and temporary relationships of one kind or another, both the types of speech role that they are taking on in the dialogue and the whole cluster of socially significant relationships in which they are involved. Mode refers to what part the language is playing, what it is that the participants are expecting the language to do for them in that situation. Collectively the three aspects of situational context are called register (Hu, 2010: 324).

In Eggins’s book, Halliday claimed that field, mode and tenor are the three situational variables that matter, because there are the three types of meaning language is structured to make. He suggested that of all the uses we make of language (which are limitless and changing) is designed to fulfil three main functions: a function for relating experience, a function for creating interpersonal

relationships, and a function for organizing information.

4 make: the experiential, the textual and the interpersonal. And these are the three kinds of meanings that matter in any situation. It is this non-arbitrary organization of language that is what Halliday means when he stated that the internal organization of natural language can best be explained in the light of the social functions which language has evolved to serve. Language is as it is because of what it has to do (Eggins, 1994: 76-79). In conclusion, to understand the language use in the text we need to analyse its context of situation.

Context is influenced by text, this is due to the variable, which living on the text interacts with the text, affect each other (Sinar, 2003: 23-24). In discourse analysis, we need to understand the differences in discourse and text, so it does not become ambiguous in terms of its use. In Sinar’s book, Kridilaksana (1982) said “Discourse is the most complete language unit; in the grammatical hierarchy is the highest or largest grammatical unit. This discourse is realized in the form of a complete essay (novels, books, encyclopedias series, and so on), paragraphs, sentences or words that carry complete mandate.” (Sinar, 2003: 5). While Halliday and Hasan (1976:1) said that text is a unit of language use, not grammatical units such as clauses and sentences, and not defined following the size.

Systemic functional linguistic theory considers clauses as the highest grammatical unit and built on smaller units below it which are groups or phrases, while groups or phrases built on words unit consists of morpheme. Whereas sentences are not a grammatical unit but a unit of written language that begins with a capital letter and end with a period. Furthermore, words are a grammatical unit as the building factors of groups or phrases and morphemes are a grammatical unit that builds words (Sinar, 2003: 17-18). Then, paragraphs are made up of related sentences and are about one topic only. Paragraphs have a topic sentence; all the other sentences relate to it (Anonymous: 2).

5 used to discuss things oriented to social factors, while the term ‘text’ tends to be used to talk about things based/oriented to language (Sinar, 2003: 6).

So, with this study, in order to understand how texts work to make meaning, it is important to find the context of situation. In this study, writer is interested to analyse the context of situation found in Oscar Wilde’s short story “The Nightingale and the Rose”. The reason writer chose to analyse one of Oscar Wilde’s works is because his works reflects about self-awareness. While, the reason writer chose the short story “The Nightingale and the Rose” is because the participants of this story are comprised of humans, animals and plants, they are the young Student and the daughter of the professor, Nightingale, little Green Lizard and Butterfly, Daisy, White Rose-tree, Yellow Rose-tree, Red Rose-tree and Oak-tree. Because of the participants comprised of humans and non-humans, writer was interested in analysing the language used in the story. It can be seen in these examples:

"Why is he weeping?" asked a little Green Lizard, as he ran past him with his tail in the air.

"Why, indeed?" said a Butterfly, who was fluttering about after a sunbeam. "Why, indeed?" whispered a Daisy to his neighbour, in a soft, low voice. "He is weeping for a red rose," said the Nightingale.

"For a red rose?" they cried; "how very ridiculous!" and the little Lizard, who was something of a cynic, laughed outright.

The text above is the eighth text of Oscar Wilde’s short story “The Nightingale and the Rose”. The contexts of situation in this text are as the following.

Field

These paragraphs are about why the young Student is weeping, because the dialogues described that the Nightingale answering why the young Student is weeping to her neighbours who were asking about it and the little Green Lizard thought it was ridiculous to weep for a red rose.

Tenor

6 was infrequent because there were no vocatives in use and the affective involvement was low because the conversation was very brief.

Mode

The role of language in this paragraph is action, because it is used to describe the action of the participants, and the language is written as a dialogue. Also, the participants used formal language, because of the use of the third person (he) and active voice.

Besides, Oscar Wilde, the author of the story, made the animals and plants to be able to think as well as humans and used formal language. The examples of that can be seen in the first and fourth texts of Oscar Wilde’s short story “The Nightingale and the Rose”, as the following.

1. "She said that she would dance with me if I brought her red roses," cried the young Student; "but in all my garden there is no red rose."

2. "Here at last is a true lover," said the Nightingale. "Night after night have I sung of him, though I knew him not: night after night have I told his story to the stars, and now I see him. His hair is dark as the hyacinth-blossom, and his lips are red as the rose of his desire; but passion has made his face like pale ivory, and sorrow has set her seal upon his brow."

Form the examples in texts (1) and (2) we can see that the young Student and the Nightingale’s monologues both used the third person voices (She, her, him and his) and active voices, and that are the characteristics of formal language.

Based on explanation above, writer analyses the context of situation found in Oscar Wilde’s short story “The Nightingale and the Rose”.

1.2Problems of the Study

The problems of the study are as the following.

7 the Rose”?

2. Who are the tenors in the Oscar Wilde’s short story “The Nightingale and the Rose”?

3. What kinds of mode are used in the Oscar Wilde’s short story “The Nightingale and the Rose”?

1.3Objectives of the Study

The objectives of the study are as the following.

1. To find out the fields in the Oscar Wilde’s short story “The Nightingale and the Rose” ;

2. To find out the tenors in the Oscar Wilde’s short story “The Nightingale and the Rose”;

3. To find out the mode in the Oscar Wilde’s short story “The Nightingale and the Rose”.

1.4Scope of the Study

The scope of the study is about context of situation, which are as the following.

1. Field: what the language is being used to talk about; 2. Tenor: the role relationships between the interactants; 3. Mode: the role language is playing in the interaction.

1.5Significance of the Study

The significance of the study can be seen theoretically and practically, as the following.

1. Theoretically, this study can be used to increase the reference about the language analysis about context of situation in short story;

9 CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

2.1 Context of Situation: Register Theory

The theory writer used to analyse the text is the theory of context of situation by Halliday. Context of situation can be specified through use of the register variables (a) Field: refers to what is going on, including: Activity focus (nature of social activity) and Object focus (subject matter), (b) Tenor: refers to the social relationships between those taking part, these are specifiable in terms of: Status or power (agent roles, peer or hierarchic relations) and Affect (degree of like, dislike or neutrality) and (c) Mode: refers to how language is being used, whether: The channel of communication is spoken or written and Language is being used as a mode of action or reflection (Gerot, 1994: 11).

Halliday developed this theory following in the functional-semantic tradition pursued by Firth. These three variables are called the register variables, and a description of the values for each of these variables at a given time of language use is a register description of a text.

In setting these three variables up, Halliday is making the claim that, of all the things going on in a situation at a time of language use, only these there have a direct and significant impact on the type of language that will be produced (Eggins, 1994: 52-53).

1. Field

10 However, although there are two texts that can have the same field, the situations which gave rise to each of these texts can be very different. We need to recognize that situations may be either technical or everyday in their construction of an activity focus. In other words, field varies along a dimension of technicality.

A situation which we would describe as technical would be characterized by a significant degree of assumed knowledge among the interactants about the activity focus, whereas in an everyday (or commonsense) situation, the only assumed knowledge is ‘common knowledge’. The knowledge that constitutes a field can be represented in taxonomies, by asking ‘how do people who act in this field classify and sub-classify the areas of the field?’ when we construct field taxonomies, we find a striking difference between the depth and complexity of a technical taxonomy and that of a commonsense taxonomy.

The technical taxonomy is complex: it involves initial classification of the topic into main aspects, then each of which is further sub-classified. When the extent of the classification involves is up to two times, that degree of sub-classification produces what we describe as a deep taxonomy. This particular deep taxonomy represents a detailed, in-depth organization of the activity focus of the topic, and the taxonomy can thus be seen to encode the expert’s understanding of the field.

On the contrary, the commonsense taxonomy has a larger number of initial cuts (the basic classification of the activity into constituent aspects is more diverse, i.e. less generalized), but each aspect is only sub-classified a further one or two times. Thus, this shallow taxonomy captures the layperson’s encoding of the field, which can be significantly different from technical construction of the same field.

Technical Situation Everyday Situation Assumed knowledge of an

activity/institution/area

Deep taxonomy - detailed sub-classification

‘Common knowledge’ no (or little) assumed knowledge

Shallow taxonomy - limited sub-classification

11 technical terms: not just technical nouns but also verbs. These terms are usually drawn from the ‘deep’ end of the taxonomy, and of course no explanation for the terms is given. Even more inaccessible to the layperson are the use of technical acronyms. The use of ‘jargon’ is not designed to impress the outsider, although it can be used in that depowering way. Its principal motivation is to allow the elaboration of the deep taxonomies of the field.

Technicality is not only encoded in the lexis, however. Technical texts frequently use abbreviated, non-standard syntax, or exploit another common technical technique: the use of a visual representation of a type particular to the field. The types of verbs used tend to be of technical processes, or of attributive (descriptive) process. These grammatical choices reflect the focus of a technical situation, which is to relate, comment on and evaluate an already shared knowledge base.

Language in an everyday field is more familiar to us: the lexis tends to consist of everyday words. Where a term is used technically, it will usually be signalled as such by being printed in bold or having quotation marks around it. Verbs will tend to be of the identifying (defining) kind, as technical terms are progressively introduced and defined. The grammatical structures will be standard, and acronyms and visual representations will be only be used if they first introduced and explained (Eggins, 1994: 67-74).

Technical and everyday language: the linguistic implications of Field Technical Language Everyday Language Technical terms

– words only ‘insiders’ understand Acronyms

Abbreviated syntax

Technical action processes attributive (descriptive) process

Everyday terms

– words we all understand Full names

Standard syntax

Indentifying processes (defining terms)

2. Tenor

12 customer/salesperson, and friend/friend.

Instinctively you recognize that the kind of social role you are playing in a situation will have an effect on how you use language. For example, you don’t talk to the greengrocer the same way you talk to your mother. However, we need to get more precise about just what aspects of the Tenor of situations are important, and in what ways.

Building on pioneering studies of language variation and role relationship variables such as formality, politeness, and reciprocity (e.g. Brown and Gilman, 1960/72), Cate Poynton (1985) has suggested that Tenor can be broken down into three different continua: (a) Power, (b) Contact and (c) Affective involvement. What this means is that the general notion of ‘role relationships’ can be seen as a complex of these three simultaneous dimensions:

a. Power

Power continuum shows the positions of situations in terms of whether the roles we are laying are those in which we are of equal or unequal power. The examples of roles of equal power are those of friends; examples of roles of unequal (non-reciprocal) power would be those of boss/employee.

b. Contact

Contact continuum shows the positions of situations in terms of whether the roles we are playing are those that bring us into frequent or infrequent contact. For example, contrast the frequent contact between spouses, with the occasional contact with distant acquaintances.

c. Affective involvement

13 involvement between us is high or low. This dimension refers to the extent to which we are emotionally involved or committed in a situation. For example, friends or lovers are obviously affectively involved, whereas work associates are typically not.

It is important to remember that Halliday’s identification, and Ponyton’s sub-classification, of tenor is proposed as a direct claim about the link between language and context. The claim, then, is that these aspects of our role occupation in a given situation will have an impact on how we use language.

We can draw a contrast between two situation types, the informal and the formal, according to their typical tenor dimension. Thus, an informal situation would typically involve interactants who are of equal power, who see each other frequently, and who are affectively involved (e.g. close friends). A formal situation would be one where the power between the interactants is not equal, the contact is infrequent, and the affective involvement low (e.g. a first-year student meeting the Vice Chancellor).

Informal Formal

Equal power Frequent contact

High affective involvement

Unequal, hierarchic power Infrequent, or one-off, contact Low affective involvement

14 language we find many politeness expressions (please, thank you, you’re welcome, etc.), often absent from informal language. Swearing, while common in informal settings, is taboo in most formal situation.

One area of considerable interest that differentiates the informal from the formal is that of vocatives. Vocatives, or terms of address, are the words that people call each other when, for example, they wish to get each other’s attention. The choice of which vocative to use reveals important tenor dimensions, compare: Sir John! Mr Smith! John! Johnno! Darl! Idiot Features! As these examples

indicate, vocatives are a very potent area for the realization of interpersonal meanings, an area very sensitive to these contextual constraints of tenor.

Ponyton’s study of vocatives in Australian English has suggested that there are correlations between the dimensions of power, contact and affect, and the choice of vocatives. It appears that:

1. When power is equal, vocative use is reciprocal: if I call you by your first name, you will call me by my first name. Or if I use title plus surname, so will you.

2. Where power is unequal, vocative use will be non-reciprocal: you may call your doctor Dr Bloggs, but he may call you Peter.

3. Where contact is frequent we often use nicknames: Johnno, Pete, Shirl. 4. Where contact is infrequent, we often have no vocatives at all (e.g. the

clerk at the post office, or the bus driver you see every day).

5. Where affective involvement is high, we use diminutive forms of names and terms of endearment: Georgie-Porgie, Petie-pie, Honey Bunch, Darl.

6. Where affective involvement is low, we use formal ‘given’ names: Peter, Suzanne.

15 but are just ‘chatting’), we can see a clear correlation between the tenor variables and both the length and type of interaction:

1. Where both affective involvement and contact are low (e.g. a conversation with your neighbour), conversations tend to be fairly brief; whereas with high affective involvement and frequent contact (e.g. with friends), conversations can go on for hours.

2. In addition, where affective involvement and contact are low, the conversation will emphasize consensus, agreement; whereas where contact and affect are high, the conversation is likely to be characterized by controversy and disagreement (Eggins 1990, Eggins and Slade, forthcoming).

These correlations help explain both why we find ‘polite’ conversation so difficult to sustain, and also why we spend most of our time with our friends arguing about things!

One further area, tenor can be related to nominalization (one kind of grammatical metaphor), so the variables of tenor can be related to a different kind of grammatical metaphor. Imagine you need help moving some furniture. In an informal situation (e.g. at home) you might turn to your partner/kids/friends and say:

1. Hey, Freddie! Get off your butt and give me a hand here. Shove that chair over closer to the desk.

Now imagine that you are moving furniture at work, and that the only available helper is the Big Boss. This time you might say:

2. Oh, Dr Smith, I’m just trying to tidy my office up a bit and I wondered if you’d mind maybe giving me a quick hand with moving some furniture?

16 move this chair over a bit nearer to the desk there. Thanks very much.

If we compare these two examples, we can see a number of the differences we have already discussed: the choice of vocatives, use/avoidance of slang and politeness phenomena. But another major difference between the two concerns the choice of clause structure. In the informal version, we see that to get an action carried out by somebody else we would use an imperative clause (get off your butt, shove that chair ...). This is the typical choice of clause type we use when

commanding family and friends. But in the formal situation, although the speaker is still making a demand of the other person, this time the clause type is the interrogative or question (would you mind ... if we could ...). The interrogatives also involve the use of words like would, could, mind, etc.: words we describe as functioning to modulate or attenuate the request. Clauses which package requests indirectly, using structures other than imperatives, are examples of grammatical metaphor (Eggins, 1994: 63-67).

Formal and informal language: the linguistic consequences of Tenor Informal Language Formal Language Attitudinal lexis (purr & snarl words)

Colloquial lexis - Abbreviated forms - Slang

Swearing

Interruptions, overlap

First names, nick-names, diminutives Typical mood choices

Modalization to express probability Modalization to express opinion

Neutral lexis Formal lexis

- Full forms - No slang

Politeness phenomena (Ps & Qs)

Careful turn-taking Titles, no names

Incongruent mood choices

Modalization to express deference Modalization to express suggestion

17 and speak about them. Arluke and Sanders (1996) said that how we view animals, indeed, what they mean to us is therefore a social construct that reflects our interactions with them and our cultural identities. Many of us, for instance, have clear ideas about the status of animals that are tied to historical and cultural uses of them as resources for food and fiber. Therefore, Glenn (2004) and Smith-Harris (2004) thought that language provides a powerful means by which to communicate our social values and norms, such as the uses and values assigned to animals.

In the animal industries, evidence of the relationship among language, power, and the socially constructed view of animals as human resources is easily found in animal science textbooks. In fact, many introductory chapters of such texts and Schillo (2003) characterized animals as existing solely to serve humans. The political nature of the relationship between humans and animals thus becomes clear—humans domesticated animals and subsequently maintain control over how they are used. Therefore, Van Dijk (1997) and Scully (2002) thought animals are viewed as subordinate to humans—an idea that is reinforced by such factors as the patriarchal nature of western society and religious beliefs related to humans having God-given dominion over animals. Inevitably, views, which are reflected in and reinforced by our language and interactions with animals, influence how we treat animals (Croney, 2008: 387-388).

In Fill’s journal, it discussed about the connections between language and environment. The term of Ecology was introduced into linguistics by Einar Haugen, an American linguist. Language ecology was defined by Haugen as “the study of interactions between any given language and its environment”, this environment being both the society that uses the language and the human mind in which it may be surrounded by other languages.

18 relationships between animals and plants (e.g. feeder – fodder, predator – prey relationships etc.) and in which the bio-diversity of the earth was studied.

The critical branch of ecolinguistics in the Hallidayan tradition has its theoretical basis in interaction between language, thought and reality. Languages are thought to have developed in a long evolutionary process whose aim was the proliferation of humans over the world, making the description (or rather construction) of the world for the best use by humans a principle of this development.

In Burke’s journal, she discussed about highly literate culture to make use of written texts to organize thought, to test beliefs, to convey what is valued, and to attempt to influence the actions and thoughts of others. More specifically, with stories involve animals possessing human capabilities and characteristics. When these animals begin to talk and scheme and learn to read, we have gone past their intuitive inclusion in a replication of reality and have put them to use in a purposeful distortion of reality. This is an example use of anthropomorphism. Simply put, anthropomorphism involves assigning a human trait to an animal or object. And, Vygotsky (1986) said that all forms of writing—imaginative, critical, scientific, and reporting—are the tools of thought. The use of a series of anthropomorphic stories is used to introduce and deal with new and controversial topics. (Burke, 2004: 205-207).

3. Mode

The general definition of mode referred simply to ‘the role language is playing in an interaction’. Martin (1984) has suggested that this role can be seen as involving two simultaneous continua which describe two different types of distance in the relation between language and situation.

a. Spatial/Interpersonal distance

19 of immediate feedback between the interactants. At one pole of the continuum, then, is the situation of sitting down to a casual chat with friends, where there is both visual and aural contact, and thus feedback is immediate (if you disagree with what your friend is saying, you say so straightaway, or ‘to his face’). At the other end of the continuum would be the situation of writing a book, where there is no visual or aural contact between writer and reader(s), and thus no possibility of immediate feedback (and even the possibilities of delayed feedback are limited. If you don’t like a novel, how do you let the author know?).

In between these two poles we can situate other types of situations, such as telephone calls (where there is aural but not visual contact, with slightly constrained feedback possibilities), and radio broadcasts (with one-way aural contact, but no immediate feedback). Modern communication modes (such as Faxes, Telexes, and Electronic Mail, etc.) reveal complicated mode dimensions.

b. Experiential distance

This second continuum of experiential distance illustrates ranges the situations according to the distance between language and the social process occurring. At one pole of this continuum, we can put situations such as playing a game (of cards, monopoly, etc.), where language is being use to accompany the activity interactants are involved in. We can describe the role of language here as almost kind of action: as well as the action of dealing and playing the cards, there is the verbal action of making a bid, talking about whose turn it is, naming the cards to be played, etc. In such a situation, language is just one of the means being used to achieve on-going action.

Contrast this with the other polar extreme, for example writing a piece of fiction, where language is all that there is. There is no other social process going on: language is in fact creating, and therefore constituting, the social process. In these situations, language is being used to reflect on experience, rather than enact it.

20 each continuum), we can characterize the basic contrast between spoken and written situations of language use. The situations where we use spoken language are typically interactive situations (we do not usually deliver monologues to ourselves, although we do often interact with ourselves by imagining a respondent to our remarks). In most spoken situations we are in immediate face-to-face contact with our interactant(s), and we are very typically using language to achieve some on-going social action, e.g. to get the furniture positioned, the kids organized, etc. In such situations we usually act spontaneously, so that our linguistic output is unrehearsed. Because spoken situations are often ‘every day’, we are generally relaxed and casual during the interaction.

Contrast this with typical situation where we are using written language, for example, writing an essay for university. There we would typically find ourselves alone, not face-to-face, aural or visual contact with our intended audience (the marker of our essay). Language would be used to reflect on some topic, the lecturer does not want to read a commentary on our actions, feelings and thoughts of our essay writing process (‘now I’m picking up my pen, but I’m not really feeling like writing this essay ..’!) Written situations in our culture call for

rehearsal: we draft, edit, rewrite and finally re-copy our essay. Finally, for most of us writing is not a casual activity: we need peace and quiet, we gather our thoughts, and we need to concentrate. The two situations of language use, then, reveal very different dimensions.

Mode: typical situations of language use

Spoken Discourse Written Text

+Interactive

2 or more participants +Face-to-face

In the same place at the same time +Language as action

Using language to accomplish some task +Spontaneous

Without rehearsing what is going to be said +Casual

Informal and everyday

Non-interactive One participant Not face-to-face On his/her own

Not language as action Using language to reflect Not spontaneous

Planning, drafting and rewriting Not casual

21 To this point all we have done is suggest ways of analysing situations of language use. But you will remember that the systemic claim is much more than that: it is that this analysis of the situation tells us something significant about how language will be used. To evaluate that claim, what we have to do is to demonstrate that these dimensions of the situation have an effect on the language used.

In fact it turns out that there are some very obvious implications of the contrast between spoken and written modes, i.e. that certain linguistic patterns correspond to different positions on the mode continua.

We can see that the linguistic differences that correspond to our two polar extremes of a spoken and a written language situation. The language we use in a spoken language will typically be organized according to the turn-by-turn sequencing of talk: first you speak, then I speak, then you speak again. Written language, on the other hand, will be produced as a monologic block. Because we are usually in the same place at the same time when we talk each other, our language can depend in part on the context: when we’re washing up, I can say to you ‘pass it to me’ or ‘put it over here’ or ‘don’t do that’, because you will be able to interpret the ‘it’ or the ‘that’ from the on-going context we share. But a written text needs to stand more or less by itself: it needs to be context-independent. It is not a good strategy to begin an essay with ‘I agree with this’, or ‘As it says here in this book’, as the reader will not be able to decode the ‘this’ or the ‘it here’.

Because a spoken interaction tends to accompany action, so the structure of the talk will be a largely dynamic one, with one sentence leading to another to another to another (‘Well if you don’t pass me that I won’t be able to get in here and then we’ll be stuck because what will they say?’, etc.). Written text, however, because it

is intended to encode our considered reflections on a topic, will be organized synoptically: it will have the Beginning, Middle, End type of generic structure, and then, the structure will be determined before the text itself is complete. So, regardless of the specific essay question, the (good!) student will try to follow the stages of Statement of Thesis, Evidence, Summary, and Reiteration of Thesis.

22 observed. If we recorded the spoken text, we would find that it contained a range of spontaneity phenomena such as hesitations, false starts, repetitions, interruptions, etc., whereas the written text will (ideally) have all such traces removed. The spoken text will contain everyday sort of words, including slang and dialect features (e.g. youz), and often sentences will not follow standard grammatical conventions (e.g. I usen’t to do that; I seen it yesterday). In the written text, however, we will choose more prestigious vocabulary, and use standard grammatical constructions.

To this point the differences we have noted between the language of spoken and written situations are no doubt quite familiar to you. It is important to appreciate that these linguistic differences are not accidental, but are the functional consequence (the reflex) of the situational differences in mode.

However, there are two more linguistic features that are highly sensitive to mode variation: the degree of grammatical complexity and the lexical density of the language chosen. These features are responsible for perhaps the most striking differences between spoken and written language, and both can be related to the process of nominalization (Eggins, 1994: 53-57).

Spoken and written language: the linguistic implications of Mode Spoken Language Written Language Turn-taking organization

Context dependent Dynamic structure - Interactive staging - Open-ended

Spontaneity phenomena

(False start, hesitations, interruptions, overlap, incomplete clauses)

Everyday lexis Non-standard grammar Grammatical complexity Lexically sparce Monologic organization Context independent Synoptic structure

- Rhetorical staging - Closed, finite ‘Final draft’ (polished)

Indications of earlier drafts removed

23 Characteristics of Spoken and Written Language

Written and spoken language differs in many ways. However some forms of writing are closer to speech than others, and vice versa. Below are some of the ways in which these two forms of language differ:

1. Writing is usually permanent and written texts cannot usually be changed once they have been printed/written out.

2. Speech is usually transient, unless recorded, and speakers can correct themselves and change their utterances as they go along.

3. A written text can communicate across time and space for as long as the particular language and writing system is still understood.

4. Speech is usually used for immediate interactions.

5. Written language tends to be more complex and intricate than speech with longer sentences and many subordinate clauses. The punctuation and layout of written texts also have no spoken equivalent. However some forms of written language, such as instant messages and email, are closer to spoken language.

6. Spoken language tends to be full of repetitions, incomplete sentences, corrections and interruptions, with the exception of formal speeches and other scripted forms of speech, such as news reports and scripts for plays and films.

7. Writers receive no immediate feedback from their readers, except in computer-based communication. Therefore they cannot rely on context to clarify things so there is more need to explain things clearly and unambiguously than in speech, except in written correspondence between people who know one another well.

24 9. Writers can make use of punctuation, headings, layout, colours and other graphical effects in their written texts. Such things are not available in speech

10.Speech can use timing, tone, volume, and timbre to add emotional context.

11.Written material can be read repeatedly and closely analysed, and notes can be made on the writing surface. Only recorded speech can be used in this way.

12.Some grammatical constructions are only used in writing, as are some kinds of vocabulary, such as some complex chemical and legal terms. Some types of vocabulary are used only or mainly in speech. These include slang expressions, and tags like y'know, like, etc (Simon, 1998).

Characteristics of Formal and Informal Language

Formal Language

1. Use Specific Language

Use of specific terms—in place of general ones—will make more of an impact, providing the reader with more information.

Example: “Book” is a general term, while “The Scarlet Letter, by Nathaniel Hawthorne” is more specific.

Use of physically concrete language, which appeals more directly to the senses, should replace vague, abstract terms, which have a debatable definition. The reader will get a clearer understanding.

Example: “The scenery was beautiful.”

25 “The bright green grass and the clear blue afternoon sky made us thankful to be outdoors.”

2. Avoid Clichés

Because clichés are phrases that are commonly used, they tend to make your paper sound less original. Try, instead, to think of a new way to say something, or leave the phrase out.

Example: He took to it like a duck to water. Try instead, “He accomplished the task with little effort."

The chances are few and far between. Try instead, "The chances are

very rare."

His grandfather was as blind as a bat. Try instead, "His grandfather had a severe vision problem."

It was as easy as could be. Try instead, "It was extremely easy."

These are just some examples of clichés. In general, remember that if

you’ve heard a phrase all your lifetime, your professor probably has

too, so change it.

3. Use Third Person Voice

First person is “I,” or “we”; second person is “you,” and third person is “he,” “she,” “one,” or “they.”

4. Choose Active over Passive Voice

Active voice usually uses fewer words, and emphasizes the doer of the action, thus making the writing clearer and livelier for the audience. Example: “He gave the paper to me” is an active sentence.

Passive voice puts the receiver of the action first, and then either puts the doer of the action after the verb, or does not name the doer at all. Passive voice should only be used if the doer of the action is unimportant, or unknown. To say it another way, with active voice, the subject of the sentence acts, but in passive voice, the subject is acted upon.

26 5. Words to Avoid

a) Avoid euphemisms; be straightforward.

Euphemisms are “nice” words that are used in the place of certain realistic words.

Example: His cousin “passed away,” Instead write: His cousin died. b) Replace “neologisms” with more commonly accepted words.

Neologisms are new words which have not been widely accepted in formal language throughout society.

Example: He is a “player.” Instead write: He is a philanderer. c) Avoid slang and colloquialisms.

Example: “Y’all" come with us. Instead write: All of you come with us.

d) Avoid unnecessary “buzzwords” which add no meaning to a sentence.

Example: She was only interested in the “bottom line.” Instead write: She was only interested in the profits.

e) Replace existential noun phrases with specific, active verbs. Try not to use “there” or “it” at the beginning of a sentence to show existence. Avoid wordiness by using a specific subject.

Example: It was on Monday that she called. Instead write: She called on Monday.

27 Informal Language

1. Discourse markers which organize and link whole stretches of language.

Example: Anyway, well, right, now, OK, so.

2. Grammatical ellipsis in which subjects, main verbs and sometimes articles are omitted. The omissions assume the message can be understood by the recipient.

Example: Sounds good (That sounds good); Spoken to Jim today (I’ve spoken to Jim today); Nice idea (That was a nice idea)

3. Purposefully vague language which serve to approximate and to make statements less assertive.

This includes very frequent nouns such as thing and stuff and phrases such as I think, I don’t know, and all that, or so, sort of, whatever, etc. 4. Single words or short phrases which are used for responding.

Example: Absolutely, Exactly, I see.

5. Frequent use of personal pronouns, especially I and you and we, often in a contracted form.

Example: I’d or we’ve.

6. Modality is more commonly indicated by means of adjectives and adverbs such as possibly, perhaps, certain and modal phrases such as be supposed to, be meant to, appear to, tend to.

7. Clause structure which often consists of several clauses chained together.

Example: I’m sorry but I can’t meet you tonight and the cat’s ill which doesn’t help but call me anyway (Anonymous, 1-2).

2.2 Relevance Studies

The relevance studies are as the following.

28 Situation by Lenni Waty Sitinjak, 2004.

In this thesis, Sitinjak analysed about the context of situation in Jakarta Post Headlines from the 1 - 15 April about Indonesian Politics and used the library research method. Sintinjak concluded that headlines cannot describe clearly what is ‘going on’ (the field of the discourse), who are taking parts in it (tenor of the discourse) and what role is language playing (the mode of discourse). These three features of context of situation can be seen from the texts that support the headlines.

This thesis also helps writer in analysing context of situation.

2. An Analysis of Advertisements Based on the Theory of Context of Situation by Gita Amalia, 2005.

In this thesis, Amalia was analysing about the context of situation in Advertisements in Kompas daily newspaper published in July 2004 and used library research method. Amalia concluded that by studying and analysing context of situation the readers can be more easily understand the meaning of the advertisement text. So, the communication would gain successfully.

The same with the previous thesis, this thesis also helps writer in analysing context of situation.

3. Tenor Analysis on Some World’s Influencing Women Speeches by Ayu Sugianto, 2012.

29 brought infrequent contact. It can be seen that they never used nick names when they called name of someone that being there in the forum of the speech. And (c) Hillary Rodham Clinton and Condoleezza Rice brought low affection when delivering their speech, but their feeling is positive. This can be seen that they showed their pride, honor and thankfulness of being there in the forum of the speech and for the audiences’ support of their statement.

30 CHAPTER III

METHOD OF RESEARCH

3.1 Research Design

The method of research applied is qualitative research method. The focus of qualitative research method is on the designation of meaning, description, clarification, and placement of each of the data context and often described in the form of words rather than numbers. Qualitative research method based on the paradigm of inductive methodological and data provision activities take place simultaneously with the data analysis activities. The steps of data analysis applied in this method are (1) Conceptualization, categorization, and descriptions are developed on the basis of incidences that occur and (2) Theorization that showed linkage relationships among categories is also developed on the basis of the data obtained (Mahsun, 2012: 256-257).

1.2Data and Sources of Data

The data of the study are the utterances in Oscar Wilde’s short story “The Nightingale and the Rose”. The source of the data is obtained from the internet, and it consisted of 38 texts. Writer chose the short story “The Nightingale and the Rose” because this is the only short story by Oscar Wilde with the participants that comprised of humans, animals and plants.

1.3Data Collection Method

31 1.4Data Analysis Method

The method of analysing data is descriptive method. Descriptive method aims to explain the matters of the problem or a particular object in detail (Suyanto, 2005: XIV).

The steps of analysing data are: 1) Reading the text.

2) Identifying the field, tenor and mode of the text.

32 CHAPTER IV

ANALYSIS AND FINDING

In this chapter writer analysed the data, which are 38 texts, to find the field, tenor and mode in each paragraphs of the Oscar Wilde’s short story “The Nightingale and the Rose” using the theory of context of situation by Halliday (1978).

4.1Data Analysis

1. "She said that she would dance with me if I brought her red roses," cried the young Student; "but in all my garden there is no red rose."

Field

This paragraph is about the young Student who wanted a red rose to get a dance with a girl, but he did not have a red rose in his garden, because the young Student was talking about a red rose.

Tenor

The participant is the young Student. There was no power, contact and affective involvement because he only interacted with himself.

Mode

The role of language in this paragraph is action, because it is used to describe the thought of the young Student, and the language is written as a monologue. Also, the young Student used formal language, because of the use of the third person (she and her) and active voice.

2. From her nest in the holm-oak tree the Nightingale heard him, and she looked out through the leaves, and wondered.

Field

33 Tenor

The participant is the Nightingale. There was no power, contact and affective involvement because there was no interaction.

Mode

The role of language in this paragraph is action, because it is used to describe the activity of the Nightingale, and the language is written as on-going action.

3. "No red rose in all my garden!" he cried, and his beautiful eyes filled with tears. "Ah, on what little things does happiness depend! I have read all that the wise men have written, and all the secrets of philosophy are mine, yet for want of a red rose is my life made wretched."

Field

This paragraph is about the young Student who was crying for a red rose, but he did not have a red rose in his garden, because the young Student was talking about a red rose.

Tenor

The participant is the young Student. There was no power, contact and affective involvement because he only interacted with himself.

Mode

The role of language in this paragraph is action, because it is used to describe the thought of the young Student, and the language is written as a monologue. Also, the young Student used formal language, because of the use of active voice.

4. "Here at last is a true lover," said the Nightingale. "Night after night have I sung of him, though I knew him not: night after night have I told his story to the stars, and now I see him. His hair is dark as the hyacinth-blossom, and his lips are red as the rose of his desire; but passion has made his face like pale ivory, and sorrow has set her seal upon his brow."

Field

34 Tenor

The participant is the Nightingale. There was no power, contact and affective involvement because she only interacted with herself.

Mode

The role of language in this paragraph is reflection, because it is used to describe the experience of the Nightingale, and the language is written as a monologue. Also, the Nightingale used formal language, because of the use of the third person (him, his and her) and active voice.

5. "The Prince gives a ball to-morrow night," murmured the young Student, "and my love will be of the company. If I bring her a red rose she will dance with me till dawn. If I bring her a red rose, I shall hold her in my arms, and she will lean her head upon my shoulder, and her hand will be clasped in mine. But there is no red rose in my garden, so I shall sit lonely, and she will pass me by. She will have no heed of me, and my heart will break."

Field

This paragraph is about the young Student who was talking about a ball tomorrow night, but he did not have a red rose to give to a girl to get a dance with her, because the young Student was talking about a ball tomorrow night and about a red rose.

Tenor

The participant is the young Student. There was no power, contact and affective involvement because he only interacted with himself.

Mode

The role of language in this paragraph is action, because it is used to describe the thought of the young Student, and the language is written as a monologue. Also, the young Student used formal language, because of the use of the third person (her and she) and active voice.

35 Field

This paragraph is about the Nightingale’s thought about true lover, because the Nightingale was talking about true lover.

Tenor

The participant is the Nightingale. There was no power, contact and affective involvement because she only interacted with herself.

Mode

The role of language in this paragraph is reflection, because it is used to describe the experience of the Nightingale, and the language is written as a monologue. Also, the Nightingale used formal language, because of the use of the third person (he and him) and active voice.

7. "The musicians will sit in their gallery," said the young Student, "and play upon their stringed instruments, and my love will dance to the sound of the harp and the violin. She will dance so lightly that her feet will not touch the floor, and the courtiers in their gay dresses will throng round her. But with me she will not dance, for I have no red rose to give her"; and he flung himself down on the grass, and buried his face in his hands, and wept.

Field

This paragraph is about the young Student imagining about what will happen in the dance if he did not have a red rose, because the young student was talking about the musicians and red rose.

Tenor

The participant is the young Student. There was no power, contact and affective involvement because he only interacted with himself.

Mode

The role of language in this paragraph is action, because it is used to describe the thought of the young Student, and the language is written as a monologue. Also, the young Student used formal language, because of the use of the third person (she and her) and active voice.

8. "Why is he weeping?" asked a little Green Lizard, as he ran past him with his tail in the air.

36 "Why, indeed?" whispered a Daisy to his neighbour, in a soft, low voice.

"He is weeping for a red rose," said the Nightingale.

"For a red rose?" they cried; "how very ridiculous!" and the little Lizard, who was something of a cynic, laughed outright.

Field

These paragraphs are about why the young Student is weeping, because the dialogues described about the Nightingale answering why the young Student is weeping to her neighbours who were asking about it and the little Green Lizard thought it was ridiculous to weep for a red rose.

Tenor

The participants are a little Green Lizard, Butterfly, Daisy and Nightingale. The participants had equal power, because of their status as neighbours, the contact was infrequent because there were no vocatives in use and the affective involvement was low because the conversation was very brief.

Mode

The role of language in this paragraph is action, because it is used to describe the action of the participants, and the language is written as a dialogue. Also, the participants used formal language, because of the use of the third person (he) and active voice.

9. But the Nightingale understood the secret of the Student's sorrow, and she sat silent in the oak-tree, and thought about the mystery of Love.

Field

This paragraph is about the Nightingale who was thinking about the young Student and the mystery of Love.

Tenor

The participant is the Nightingale. There was no power, contact and affective involvement because there was no interaction.

Mode

37 10.Suddenly she spread her brown wings for flight, and soared into the air. She passed through the grove like a shadow, and like a shadow she sailed across the garden.

Field

This paragraph is about the Nightingale who soared into the air and sailed across the garden.

Tenor

The participant is the Nightingale. There was no power, contact and affective involvement because there was no interaction.

Mode

The role of language in this paragraph is action, because it is used to describe the activity of the Nightingale, the language is written as on-going action.

11.In the centre of the grass-plot was standing a beautiful Rose-tree, and when she saw it she flew over to it, and lit upon a spray.

Field

This paragraph is about the Nightingale who saw a Rose-tree and flew over to it.

Tenor

The participant is the Nightingale. There was no power, contact and affective involvement because there was no interaction.

Mode

The role of language in this paragraph is action, because it is used to describe the activity of the Nightingale, and the language is written as on-going action.

12."Give me a red rose," she cried, "and I will sing you my sweetest song." But the Tree shook its head.

"My roses are white," it answered; "as white as the foam of the sea, and whiter than the snow upon the mountain. But go to my brother who grows round the old sun-dial, and perhaps he will give you what you want."

38 These paragraphs are about the Nightingale who was asking for a red rose to the White Rose-tree, because the dialogues described about the Nightingale was asking for a red rose.

Tenor

The participants are the Nightingale and the White Rose-tree. The participants had equal power, because of their status as neighbours, the contact was infrequent because there were no vocatives in use and the affective involvement was low because the conversation was very brief.

Mode

The role of language in this paragraph is action, because it is used to describe the action of the participants, and the language is written as a dialogue. Also, the participants used formal language, because of the use of the third person (he) and active voice.

13.So the Nightingale flew over to the Rose-tree that was growing round the old sun-dial.

Field

This paragraph is about the Nightingale who flew over to the Rose-tree that was growing round the old sun-dial.

Tenor

The participant is the Nightingale. There was no power, contact and affective involvement because there was no interaction.

Mode

The role of language in this paragraph is action, because it is used to describe the activity of