1 LAPORAN HASIL

KEGIATAN PENELITIAN DISERTASI DOKTOR TAHUN ANGGARAN 2013

PERAN MAHKAMAH KONSTITUSI DAN KONSOLIDASI DEMOKRASI DI INDONESIA

(THE ROLE OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT AND DEMOCRATIC CONSOLIDATION IN INDONESIA)

Nama Peneliti: Iwan Satriawan, S.H., MCL.

DIBIAYAI OLEH:

Kopertis Wilayah V DIY Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan sesuai Surat Perjanjian Pelaksanaan HIBAH DISERTASI DOKTOR

Nomor: 1140.7/K5/KL/2013 Tanggal 21 Mei 2013

2 HALAMAN PENGESAHAN

LAPORAN KEMAJUAN PENELITIAN DISERTASI DOKTOR 2013

1. Judul Penelitian : Peran Mahkamah Konstitusi dan Konsolidasi Demokrasi di Indonesia

2. Judul Desertasi : The Role of The Constitutional Court and Democratic Consolidation in Indonesia 3. Nama Peneliti : Iwan Satriawan, S.H., MCL.

3.1. Data Pribadi

a. Nama Lengkap : IWAN SATRIAWAN, S.H., MCL. b. Jenis Kelamin : Laki-Laki

c. NIK/Golongan : 153.039/Penata Tingkat I/III D d. Strata/Jabatan

Fungsional

: Lektor Kepala

e. Fakultas/Jurusan : Hukum

f. Perguruan Tinggi Asal : Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta g. Bidang Ilmu : Hukum

h. Alamat Kantor : Jl. Lingkar Selatan, Tamantirto, Kasihan, Bantul, Yogyakarta

i. Telepon/Faks/E-mail : (0274) 387656, Psw : 124, (0274) 387646 j. Alamat Rumah : Rewulu Wetan, Sidokarto, Godean, Sleman k. Telpon Rumah : -

l. Handphone : 081 328 788 844

3.2. Pembimbing Utama : Associate Prof. Dr. Khairil Azmin Mochtar Anggota Pembimbing 1 : -

Anggota Pembimbing 2 : - Anggota Pembimbing 3 : -

4. Program Studi S3 : Hukum Tata Negara 5. Fakultas / Sekolah

Pascasarjana

1 CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

1.1. BACKGROUND

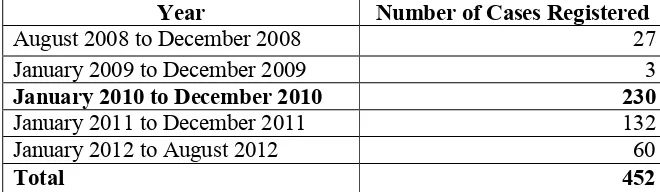

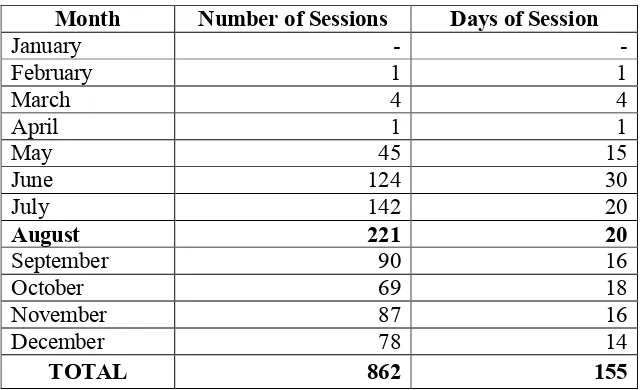

Since the establishment of the Constitutional Court in August 2003 until April 2012, the Court has received and decided 382 cases regarding judicial review of acts. The Court also has received and decided 399 cases on disputes over the result of local elections since 2008 after the Court was given an authority to settle the disputes.1 The Court has also received and decided 19 cases regarding disputes on authority among state institutions. The Court has also received and decided 657 cases of general election disputes in 2004 and 2009.2 By handling huge number of the cases, the Constitutional Court has given a meaningful contribution to the practice of constitutional principles, particularly in performing his power as the “guardian of the Constitution.” Therefore, towards celebrating a decade of the establishment of the Constitutional Court in 2013, it is important to evaluate performance of the Constitutional Court. This evaluation may investigate and analyze achievements performed and problems faced by the Constitutional Court in relation to the working of democratic consolidation in Indonesia.

Looking at the experiences of the countries called “the new emerging democracies”, there are so many obstacles that are hampering efforts to develop an effective “rule of law” system which is expected to counterweigh the system of democracy. Firstly, all new emerging democracies in East Europe such as Russia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Georgia, and other former Soviet Union States, as well as some Asian countries like the Philippines and South Korea, have similar problem on how to institutionalize democratic values through law and based on the existing law, as many of them have inherited an undemocratic past.3 Therefore, there are many laws and regulations that have to be reviewed and revised

1 Before 2008, the authority to settle over the result of local election disputes performed by the

Supreme Court through the High Court in each province.

2 See further www.mahkamahkonstitusi.go.id.

3 Article 134, 136 and 137 of Criminal Code had been nullified by the Constitutional Court of

2 according to the present demand. Secondly, within the process of transformation towards democracy, it needs to be institutionalized into official legal norms in the form of constitutions, legislations, and regulations. Thirdly, generally the new emerging democracy suffers from the “anomia syndrome” meaning that the integrity, the impartiality, and the independence of the judiciary are seriously influenced. Under the authoritarian regimes, courts are usually politically intervened by the ruling elite.4 In other words, in authoritarian regimes, courts are more considered as the attributes of the authority rather than as the attributes of justice. This situation also happened in Indonesia, in the era of Suharto regime.5 Authoritarian regimes also produce legal professionals without integrity. As the result, judicial corruption becomes very common.

In turn, judges play a significant role in guaranteeing the enforcement of “rule of law” which is the key point in achieving equilibrium in the above triadic relations among the state, the civil society and the market, and between the state and its citizens. Besides, the courts and the judges play a pivotal role in controlling the practices of democracy which is usually glued to the principles of “majority rules” and a formal application of the principle of representation.6 Some experts argue that the Constitutional Court is less dangerous compared to political institutions like parliament. Therefore, in some new emerging democratic countries then they mandated the authority to review acts to a new court: constitutional court.

In line with the development of constitutionalism ideas and the increasing demands for democratization all over the world, almost all countries claim themselves to be democratic countries, although at various levels. In the course of development, there have been many new democratic countries that started their democratization agenda by reforming their constitution. Constitutional reform has been deemed as the most fundamental measure for creating a constitution that

4 See Jimly Asshiddiqie. (2006). Access to Justice in Emerging Democracies: The Experiences

of Indonesia. In Fort, Bertrand. (Ed). Democratising Access to Justice in Transitional Countries. Proceeding of Workhsop “Comparing Access to Justice in Asian and European Transitional Countries, Indonesia, 27-28 June 2005, p. 10.

5 Many political experts and constitutional law experts describe the era of Suharto regime as

“bureaucratic-authoritarian regime which controlled every single aspect of the nation, including judicial power.

6 See Jimly Asshiddiqie. (2006). Access to Justice in Emerging Democracies: The Experiences

3 provides better assurances for the institutionalization of democratic values. This has been due to the position of the constitution as the foundation and at the same time as the framework or design of democratic values.7 The trend of new emerging democracies also shows that strengthening of checks and balances principles among state institutions is unavoidable to prevail a better environment towards democracy.

In relation to that idea to establish a Constitutional Court become highly prevalent in countries which were in transitional period heading toward democracy, including Indonesia. The idea serving as a basis for such measure was that it was important to establish a state institution which had the function of safeguarding the constitution as the highest fundamental law of a country.8 Having long experience with the practice of judiciary and surveys in particular countries like Germany and South Korea, Indonesia finally established a new court - Constitutional Court - which is expected to be the “guardian of the Constitution” in the light of guaranteeing of the fundamental rights of people.

The existence of the Constitutional Court in Indonesia has prompted ‘a new face’ and ‘a new hope’ of Indonesian constitutional system. Many achievements have been achieving by the Court since 20039. Hence, the existence of Constitutional Court has given ‘a new promising step’ in the light of judicial reform agenda in consolidating democracy in Indonesia. As stated by Gloppen,

7 See Mohammad Mahfud MD. (2010). Remarks of Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court of

Republic of Indonesia in Proceeding of The 7th Conference of Asian Constitutional Court Judges,

Jakarta, 12-17 July 2010. p.9.

8Ibid.

9 For examples, the Constitutional Court has nullified some acts which are contradictory to the

4 Gargarella and Skaar (2004) in their book “Democratization and Judiciary”, courts are important for the working and consolidation of democratic regimes. They facilitate civil government by contributing to the rule of law and by creating an environment conducive to economic growth. They also have a key role to play with regard to making power-holders accountable to democratic rules of the game, and ensuring the protection of human rights as established in constitutions, conventions and laws. In case of Indonesian Constitutional Court, however, some observers and researchers felt disappointed on particular decisions made by the Court.10 Therefore, a serious evaluation -after almost a decade of the existence of the Constitutional Court in Indonesia- is necessarily needed.

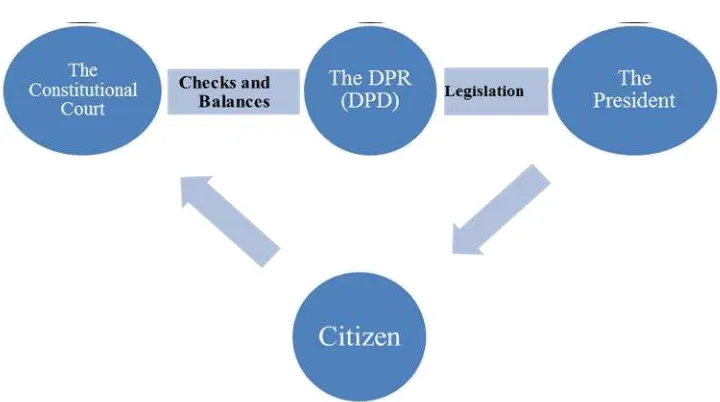

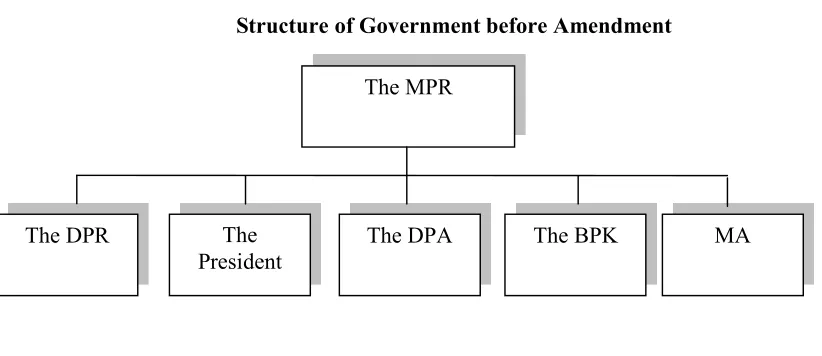

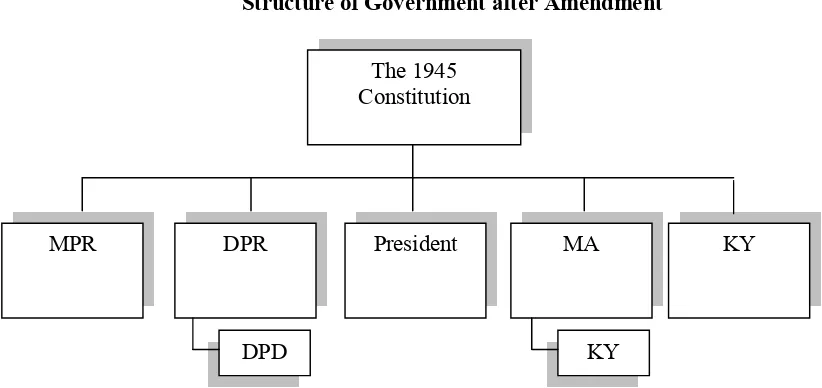

The Constitutional Court was formed based on the result of the amendment to the 1945 Constitution. As a new state organ, the Constitutional Court has strived to the extent possible to implement the authorities and obligation mandated by the 1945 Constitution and stipulated in the Law Number 24 of the Year 2003 regarding the Constitutional Court (amended by the Law Number 8 of 2011). The Constitutional Court has four authorities and one obligation in accordance with those mandated by article 24C paragraphs (1) and (2) of the 1945 Constitution. Four authorities of the Constitutional Court are examining at the first and the final level whose decision is final materially review the law against the Constitution, decide disputes over the authority of state institution whose authority is granted by the Constitution, decide the dissolution of political party, and decide dispute over the result of general election. Whereas the obligation of the Constitutional Court is providing decision over the opinion of the House of People’s Representative regarding the assumption of violation by the President and/or the Vice President according the Constitution.

10 See further the Constitutional Court Decision Number 005/PUU-IV/2006. In this decision,

5 Based on the authorities being possessed, it can said that the Constitutional Court is the guardian of the Constitution in relation to the four authorities and one obligation which its own. It also brings a consequence to the Constitutional Court to function as the sole interpreter of the Constitution. Constitution as the highest law stipulates the state governing based on the principle of democracy and one of the functions of the constitution is to protect human rights which are ensured in the Constitution. Therefore, human rights become the constitutional right of the citizen. Consequently, the Constitutional Court also functions as the guardian of democracy, the protector of the citizen’s constitutional rights and the protector of the human rights.11

Dealing with the above description, after almost 10 years or a decade of the existence of the Constitutional Court in Indonesia, it is important and urgent to evaluate the role of the Constitutional Court in light of democratic consolidation in Indonesia. The research will fundamentally examine the role of the Constitutional Court in relation to democratic consolidation in Indonesia. The evaluation is also important to highlight the achievements and the obstacles faced by the Constitutional Court in fulfilling its role in upholding the constitutional principles, and institutionalizing democratic values in the light of leading the country in the process of democratic consolidation in Indonesia. Last but not least, the research will propose some recommendations for a better role of the Constitutional Court in the future in order to strengthen the working of democratic consolidation toward an established democracy or mature democracy of Indonesia.

1.2. Statement of Problems

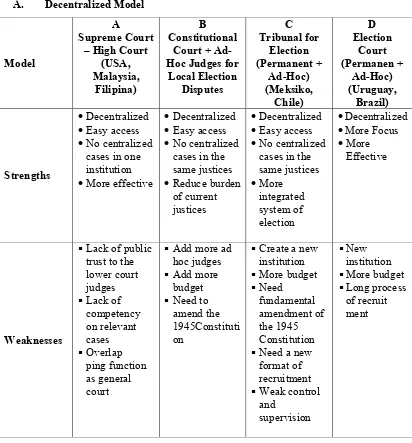

The reasons and the facts that encourage this study, first, after almost a decade of the existence of Constitutional Court in Indonesia, many constitutional law experts and political experts argue that the Constitutional Court has taken an important role in the process of democratic consolidation in Indonesia. Second, however, some experts also criticize the Constitutional Court as super body institution, go beyond their authority and question the effectiveness of the

6 structure and procedures of the Court particularly in relation to local elections disputes settlement. Therefore, a more comprehensive research on studying the role of the Constitutional Court in the working of democratic consolidation in Indonesia is necessarily needed. This comprehensive research will answer what are the roles of the Constitutional Court during the democratic consolidation in Indonesia, what achievements that have been performed and what obstacles that have been faced by the Constitutional Court. At the end of study, it will formulate some recommendations that can be proposed for a better role of the Constitutional Court in the process of democratic consolidation in order to strengthen the working of democratic consolidation toward a mature or established democracy in Indonesia.

1.3. Objectives of the Proposed Study

The emergence of the Constitutional Court in new democratic countries, including Indonesia, has prompted a fresh wind in the light of democratic consolidation. That is why a more comprehensive study is necessarily needed. As a new democratic country, Indonesia needs a sustainable and a better role of the Constitutional Court in safeguarding the consolidation of democracy. Therefore, the research will be conducted to achieve the following objectives:

1. To carry out a library research on the history and developments of constitutional adjudications in various jurisdictions. Some relevant countries like United States, Austria, Germany and South Korea will be models in the light of comparative approach.

2. To study the history of constitutional adjudication and elaborate major constitutional developments and changes in Indonesia that finally lead the framers of the amended 1945 Constitution created a new court: constitutional court.

3. To conduct analysis on the foundation of the emergence of the Constitutional Court in Indonesia.

7 5. To analyze the role the Constitutional Court in consolidating democracy in Indonesia by reviewing relevant decisions made by the Constitutional Court since 2003-2013.

6. To highlight some achievements that have been performed and problems which have been faced by the Constitutional Court in the process of democratic consolidation in Indonesia since 2003 - 2012. 7. To propose some recommendations for better role of the

Constitutional Court in the working of democratic consolidation toward mature democracy or established democracy in Indonesia.

1.4. Hypothesis

Based on the above background and explorative readings that have been conducted on the topic “the Role of Constitutional Court and Democratic Consolidation in Indonesia, the researcher hypothesizes that the Constitutional Court has played an important role in strengthening the working of democratic consolidation in Indonesia because the Constitutional Court, through its powers and decisions, has given a significant contribution at least on two aspects, first, in securing the quality of legislations, protect the fundamental rights of citizens, create more conducive political situation, support the simplification of number of political parties, guarantee freedom of expression and freedom of access of information. Second, by having those contributions, the Constitutional Court has influenced the upholding of rule of law, secure the working of elections that may lead to political stability of two elections, support stronger elected government and guarantee the right of civil society to control government and parliament (DPR).

8 better role of the Constitutional Court in strengthening the working of democratic consolidation toward a mature or established democracy in Indonesia.

1.5. Research Questions

The research focuses on answering three main questions as follows:

1. What is the role of the Constitutional Court normatively and practically in the process of democratic consolidation in Indonesia? 2. What are the achievements that have been performed and what are the

obstacles that have been faced by the Constitutional Court in strengthening the working of democratic consolidation in Indonesia? 3. What kind of recommendations that can be formulated and proposed

for a better role of the Constitutional Court in order to strengthen the working of democratic consolidation toward established democracy or mature democracy in Indonesia?

1.6. Literature Review

There are five major features of literature that attempt to address questions in dealing with the role of Constitutional Court and democratic consolidation in Indonesia. These include description on emergence of constitutional adjudication in various jurisdictions which lead in some countries- the emergence of constitutional court, constitutional adjudication in Indonesia and major developments that led the founding the new constitutional order followed by the emergence of constitutional court, constitutional bases of constitutional court in Indonesia and review some strengths and weaknesses compared to other jurisdictions and the role of constitutional court in the process of democratic consolidation in Indonesia. To complete the analysis, the research will review some pivotal decisions made by the Court that are relevant to the objectives of the research. These literatures will be examined in order to understand the relevant relationships to the current research.

9 seeks to protect the people’s basic rights by making sure the constitution is respected as the supreme law in actual practice. More concretely, it seeks to protect the constitutional order and implement the constitution by having either regular courts or a separate constitutional institution make an authoritative determination according to the constitution when cases arise in which violation of the constitution (e.g., infringement of basic rights) are alleged.12

Constitutional adjudication is as old as democratic constitutionalism. But for a long period of time, the United State of America remained alone in subjecting democratic decision-making to judicial review. While constitutions had become widely accepted already in the 19th century, it took almost two hundred years until constitutional adjudication has gained world-wide recognition.13 Rosenfeld also argues that constitutional adjudication is much older and more deeply entrenched in the United State than in Europe.14

Before the 20th century, the idea of constitutional adjudication was rejected by most European states, except in Switzerland for particular area. Grimm further explains that the reason for the rejection of constitutional adjudication in the 19th century was its alleged incompatibility with the principle of monarchical sovereignty which governed most of the European states at the time. When the monarchy collapsed and was replaced by popular sovereignty as in France in 1871 and in many other states after World War I, constitutional adjudication was found to be in contradiction with democracy. Parliament as representation of people should be under no external control. The only exception was Austria which in its Constitution of 1920 established a constitutional court with explicit power to review acts of legislature. Austria thus became the model of a new type of constitutional adjudication: that by a special constitutional court.15

In response to idea of constitutional adjudication, especially to review the acts enacted by parliament (constitutional review), there are different among the countries. In many countries, so-called constitutional adjudication is based on

12 Annual Report, Twenty Years of the Constitutional Court of Korea, 64.

13 Dieter Grimm (1999). Constitutional Adjudication and Democracy. Israel Law Review

32(1-4) and 33(1).

14 See further Michel Rosenfeld (2004), Constitutional Adjudication in Europe and the United

States: Paradoxes and Contrasts, International Journal of Constitutional Law, Vol 2, No 4, p.1.

15 Dieter Grimm(1999). Constitutional Adjudication and Democracy. Israel Law Review

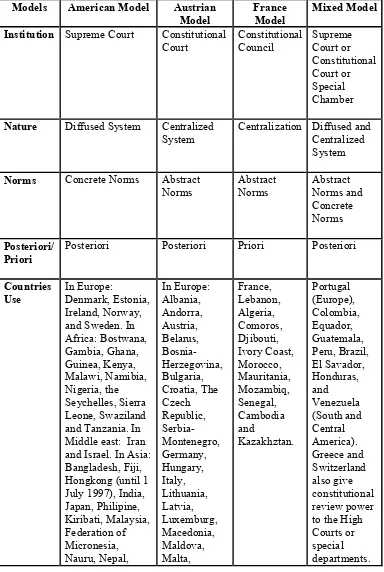

10 constitutional law. Generally speaking, there are two types of constitutional adjudication institutions16. One type establishes the Constitutional Court as a special court, while the other is the type in which constitutional adjudication is conducted by general courts, especially by Supreme Court in the final instance, without other special courts.17 Some common law countries like USA, Australia, India, and Malaysia18 put constitutional adjudication powers on Supreme Court, while continental European countries and some Asian countries like Austria19, Germany20, Eastern Europe21, South Korea22 and Indonesia23 mandate the powers to a new court: constitutional court, with different scope of authority. Elliot points out that the most things in this issue is the review of acts must be justified constitutionally as well as evaluated normatively, therefore can be refined: it must be justified by reference to relevant constitutional principles. He further explains that different types of power thus raised different challenges of justification.24

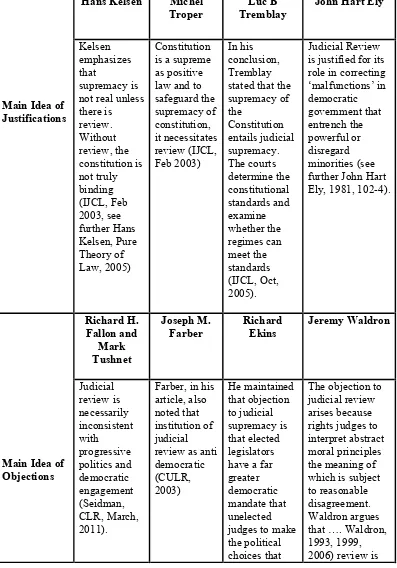

Modern scholarship on judicial review (constitutional review) begins with the counter-majoritarian difficulty. This famous problem focuses on the propriety of unelected judges, who lack democratic legitimacy, overturning duly enacted decisions of democratic assemblies.25 Ginsburg further explains that in contrast, the conventional move to solve the problem of the courts in democratic theory is to celebrate the role of judicial review in democracy as a check on majority

16 For more comparison see further Horowitz, Donald L, “Constitutional Courts: A Primer for

Decision Makers”, Journal of Democracy, Vol 17, no 4 (2006): 127-131.

17 Jibong Lim. (1999). A Comparative Study of the Constitutional Adjudication System of the

US, Germany and Korea. Tulsa Journal of Comparative and International Law 123(6).

18 Trindade, F.A & H.P. Lee. (1988). The Constitution of Malaysia-Further Perspectives and Developments. Petaling Jaya: Penerbit Fajar Bakti SDN. BHD.

19 John Ferejohn & Pasquale Pasquino. (June 2004). Constitutional Adjudication: Lessons

from Europe. Texas Law Review.

20 Taylor Cole. (May 1958). The West German Federal Constitutional Court: An Evaluation

after Six Years. The Journal of Politics 20 (2), 278-307.

21 Daniel Smilov. (January 2004). On Founding Constitutional Adjudication in Central Europe. International Journal of Constitutional Law.

22 Kun Yang. (Winter 1993). Judicial Review and Social Change in the Korean Democratizing

Process. The American Journal of Comparative Law 41(1), 1-8.

23 Jimly Asshididqie. (2005). Model-Model Pengujian Konstitusional di Berbagai Negara,

Jakarta: Konstitusi Press. See also Hendrianto. (2010). Institutional Choice and the New Indonesian Constitutional Court. In Andrew Harding & Penelope (Pip) Nicholson (eds.), New Courts in Asia (159-177). Madison, New York: Routledge.

24 Mark Elliot. (2001). The Constitutional Foundations of Judicial Review. Oxford- Portland:

Hart Publishing.

11 power.26 In others words, courts are important for the working and consolidation of democratic regimes. They facilitate civil government by contributing to the rule of law and creating an environment conducive to economic growth. They also have a key role to play with regard to making power-holders accountable to democratic rules of the game, and ensuring the protection of human rights as established in constitutions, conventions and laws.27 Mauro Cappelletti as quoted by Vanberg also emphasizes that in much of the Western world, constitutional review has come to be understood as “the necessary ‘crowning’ of the rule of law”.28

In case of Indonesia, Hendrianto29 and Ginsburg30 state that in studying the emergence of constitutional court in new democracies, some scholars have concluded that the political dynamics in a country in democratic transition are one of the main driving forces behind the creation of constitutional courts. Hendrianto further explains that Indonesia and South Korea have the same background in terms of the emergence of the constitutional courts. In the context of the establishment of the Korean Constitutional Court, the decision to adopt a designated court was the result of compromise between the ruling party and the opposition parties. Korean constitutional court had influenced Indonesian politician to look to the Korean Constitutional Court as a model.

Benny K Harman31 also asserts that the Constitutional Court has resulted in a new freshness in the political, democratic, and national life of Indonesia. The existence of the Constitutional Court serves as afresh wind for each citizen, especially in protecting their basic rights against every action taken by the state that they deem to be inconsistent with the Constitution. He further explains that

26 Ibid.

27 Siri Gloppen, Gargarella, Roberto., & Elin Skaar. (2004). Democratization and the Judiciary-The Accountability Function of Courts in New Democracies. Portland: Frank Cass Publishers.

28 Georg Vanberg. (2005). The Politics of Constitutional Review in Germany. United States of

America: Cambridge University Press.

29 Hendrianto. (2010). Institutional Choice and the New Indonesian Constitutional Court. In

Andrew Harding & Penelope (Pip) Nicholson (eds.), New Courts in Asia (159-177). Madison, New York: Routledge.

30 Tom Ginsburg. (2003). Judicial Review in New Democracies: Constitutional Courts in Asian Cases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

31 This is the translation of his article “Peranan Mahkamah Konstitusi dalam Reformasi

Hukum” in a book with title “Menjaga Denyut Nadi Konstitusi: Refleksi Satu Tahun Mahkamah

12 the existence of the Constitutional Court should be welcomed, with an expectation that this institution will be able to support the process of systematic democratization and political culture, to accomplish the checks and balances in the state administration, and to fill the gap where the community perceives that there is a lack of justice, which has for a long time been bound by authoritarianism and abuse of power of past regimes.

Lindsey argues that if effective, the new Constitutional Court has the potential to radically transform the Indonesian judicial and legislative relationship and creates a new check on the conduct of lawmakers and the presidency.32 Therefore, in relation to that, it is a meaningful effort if a more comprehensive evaluation conducted after a decade of the emergence of constitutional court. The evaluation will cover a critical analysis on the achievements made the court and it also find out obstacles faced by the Court. The research will also recommend relevant proposals to a better of role of constitutional court in the future of democracy in Indonesia.

Some studies have been conducted by constitutional law experts. Hendrianto, for instance, has initiated a serious research on the new emergence of the Constitutional Court in Indonesia. However, the research confined more on the history of the emergence of the Constitutional Court and analyzed the development of the Constitutional Court until 2006, three years after the establishment of the Constitutional Court. In this sense, the research will extend the period of the study on development of the Court until 2012, almost a decade after the establishment of the Court. Benny K Harman also wrote a paper on the role of the Constitutional Court relating to Indonesian legal reform. He focuses more on how the Constitutional Court influences the legal reform. Justice Ahmad Sodiki also written an article focused more on the role of the Constitutional Court in respect to the development of General Election Laws. Some constitutional law experts also conducted researches that study the decisions made by the

13 Constitutional Court. However, these researches emphasize more on how the implementation of the decisions in relation to the issues decided by the Constitutional Court.

In line with that, a more comprehensive research on the role of the Constitutional Court in relation to the role of the Constitutional Court in the process of democratic consolidation in Indonesia is urgent to be conducted33 The research is important in the light of giving a broader assessment on the role of the Constitutional Court and analyze how the Constitutional Court play an important role in consolidating democracy in Indonesia.

Webber argues in his paper-by quoting concept of democracy raised by Dahl that Indonesia today may be described as a democracy and it would have completed its democratic transition after having staged legislative elections in 1999.34 Meanwhile, in terms of democratic consolidation, Webber views-by using definition of democratic consolidation made by Schneider and Schmitter- that Indonesia has most of the attributes of a consolidated democracy.35 He further concludes that by using the Schneider and Schmitter criteria, Indonesia compares very favorably with other, almost all older ‘third waves democracies’ in terms of the extent of democratic consolidation. However, Schneider and Schmitter confess

33 See further, Ikrar Nusa Bhakti, The Transition to Democracy in Indonesia: Some

Outstanding Problems, Avalaible at www. apcss.org/Publication…/Chapter1Bhakti.pdf. In this article, he concludes that as mentioned by Indonesian intellectuals on Indonesia’s political transition concerns its uncertainty. Draper (2002) also pointed out that Indonesia would be much further along in its transition to democracy……..

34 In his book, Dahl proposes concept of democracy as comprising elected officials, free, fair,

and frequent elections, inclusive suffrage and citizenship, freedom of expression, alternative sources of information and associational autonomy is taken as the yardstick (Webber, 2005: p.2), See also Bunte & Ufen, Democratization in Post-Suharto Indonesia, (London: Routledge, 2009).

35 Schneider and Schmitter propose the definition of democratic consolidation as the process

14 that their conceptualization of democratic consolidation has ‘an electoralist bias’. If more demanding conceptualizations of democratic consolidation that attach greater important to, for example, the implementation of the rule of law, should be the yardstick for measuring the degree of democratic consolidation, Indonesia’s post 1998 performance would certainly look less impressive (Webber, 2005: p.6).

After almost a decade of the existence of the Constitutional Court, it is important to review some pivotal decisions made by the Court that affecting directly the fundamental rights of citizens as one of the agenda of reformation. This study will focus on how the decisions of the Constitutional Court plays role in consolidating democracy in Indonesia. Therefore, representative decisions will be selected and analyzed to examine the impact of decision to democratic consolidation in Indonesia. According to Annual Report of the Constitutional Court 2009, since 2003 to 2009, the Constitutional Court has decided 404 cases which comprises of 247 decisions relating to judicial review, 11 decisions of disputes on authority among state institutions, 116 of decisions relating disputes over the result of election and 30 decisions relating to regional elections. Achmad Sodiki (2010) summarizes some pivotal decisions, particularly the decisions made by the Court relating to general elections law. The following are some of the Constitutional Court’s decisions affecting directly the development of general election laws, namely reinstatement of the voting rights of former members of banned organization36, allowing individual candidates in the local general elections37, providing equal treatment for political parties in election38, allowing the use of identity card in general elections39, designation of candidates-elect based on majority votes40 and some others relevant decisions. The above examples are decisions that show the important role of the Constitutional Court in protecting the fundamental rights of citizens and promoting democratic values in the light of consolidating democracy in Indonesia.

Another point that needs to be noted is the power of the Constitutional Court in settling disputes over the result of general elections. This mechanism has

15 been created to ensure that general elections are actually held in a honest and fair manner by providing opportunity to general election participants to take legal action by filling their complaints about the result of general elections stipulated by KPU41. Achmad Sodiki (2010) explains that up to 2010, the Constitutional Court has handled disputes over the result of general elections’ cases in the 2004 Legislative Election, the 2004 Presidential Election, the 2009 Legislative Election, and the 2009 Presidential Election, respectively. In addition to the above, since 2008, the Constitutional Court has also handled cases of disputes over the result of regional head and deputy regional elections. The existence of the Constitutional Court relating to disputes over the result of general elections has successfully become an important tool that providing the winners and the losers compete fairly in the court. In other words, the Court has moved a potential conflict among society from the streets to the air-conditioned hall in Constitutional Court building. In other words, as Maveety-lesson from Estonian case- proves that a court can act as conduit for significant democratic reform.42

In broader sense, the research will study the role of the Constitutional Court in relation to the strengthening the process of democratic consolidation in Indonesia. In his book “on Democracy”, Roberth Dahl summarizes democracy in term of process-oriented approaches as a political life that fulfill at least five standards, namely effective participation, voting equality, enlightened understanding, control of the agenda and inclusion of adults.43 Tilly substantively defines democracy as the condition of life and politics that promotes human welfare, individual freedom, security, equity, social equality, public deliberation, and peaceful conflict resolution.44

Linz and Stephan define a democratic transition is completed when sufficient agreement has been reached about political procedures to produce an elected government, when a government comes at power that is direct result of a

41 KPU is Komisi Pemilihan Umum (General Election Commission).

42 Nancy Maveety. (2004). “Constrained” Constitutional Court as Conduits for Democratic

Consolidation. Law & Society Review 38(3), 463-488.

43 Robert. A. Dahl. (2000). On Democracy. United States: Yale University Press.

44 Charles Tilly. (2007). Democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press. See also

16 free and popular vote, when this government de facto has the authority to generate new policies, and when the executive, legislative and judicial power generated by the new democracy does not have to share power with other bodies de jure. They further explain that in most cases after a democratic transition has been completed, there are still many tasks that need to be accomplished, conditions that must be established, and attitudes and habits that must be cultivated before democracy could be considered consolidated.45 Schedler describes democratic consolidation as the challenge of making new democracies secure, of extending their life expectancy beyond the short term, of making them immune against the threat of authoritarian regression, of building dams against eventual “reverse waves”.46

However, either warns that the emergence of democracy (as any other political change) is exclusively founded on political factors, that is, on the struggle or balance of power between different classes (or social groups). She further explains that in some countries, the prospects for consolidation of new democratic regimes appear rather gloomy due to the fragility and the limits of the social consensus.47 In case of Indonesia, particularly, Davidson argues that democratic consolidation in Indonesia will continue to be bedeviled due to the poor institutionalization of a democratic rule of law.48

To enrich and deepen the analysis, the research will be conducted also by using a comparative approach through library research as well as interviews in particular countries such as United States, Germany, South Korea, Malaysia and India. However, in terms of interviews, the comparative study will more focus on Germany and South Korea since both are the main models used by Indonesia to follow at the beginning of the establishment of the Court and for common law tradition countries, Malaysia, Australia and the United States are relevant

45 Juan J Linz & Alfred Stepan. (1996). Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation-Southern Europe, South America and Post-Communist Europe. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

46 Andreas Schedler. (Spring 2001). Measuring Democratic Consolidation. Studies in Comparative International Development 36(1), 66-92. See also Mainwaring, Scott. (1989). Transitions to Democracy and Democratic Consolidation: Theoretical and Comparative Issues. A Working Paper.

47 Diana Ethier. (1990). Democratic Transition and Consolidation in Southern Europe, Latin America and Southeast Asia. London: Macmillan Press.

48 Jamie S. Davidson, 2009, Dilemmas of Democratic Consolidation In Indonesia, the fasific

17 countries to be considered as comparison. Kun Yang, Lim, and Ginsburg, for instance, have written serious articles regarding the role of the Constitutional Court and Democratization in South Korea.49 Meanwhile, Cole, Juenger and Grimm have also written meaningful articles pertaining the Germany Constitutional Court and Democracy.50 These articles will be the basis of sources in relation to comparative approach used by the researcher at the beginning of the research. If it is possible, more interviews will be conducted directly to examine the accuracy of relevant sources in both countries.

1.7. Scope and Limitations

The study generally explores the role of the Constitutional Court during the democratic consolidation in Indonesia. It confines the research on the period 2003-2012, almost a decade, after the establishment of the Constitutional Court in 2003. The pivotal points of the research are the functions of the Constitutional Court normatively and practically that influence the process of democratic consolidation in Indonesia. The powers of the Constitutional Court are to review the law against the 1945 Constitution, to decide disputes over the powers of state institutions whose authorities are mandated by the 1945 Constitution of Republic of Indonesia, to decide dissolution of political parties, and to decide disputes over the result of general election. In line with that, the research will seek the relation of the functions of the Constitutional Court to the process of democratic consolidation in Indonesia.

Another point that is the major concept of democratic consolidation and how it implemented in Indonesia after the democratic transition is completed. The research will discuss the key elements of democratic consolidation in relation to the role of the Constitutional Court in Indonesia. It will also elaborate the problems and challenges of democratic consolidation in Indonesia. As the main

49 Kun Yang. (Winter 1993). Judicial Review and Social Change in the Korean Democratizing

Process. The American Journal of Comparative Law 41(1), 1-8. See further Jibong Lim. (Spring 1999). A Comparative Study of the Constitutional Adjudication System of the US, Germany and Korea. Tulsa Journal of Comparative and International Law 123(6). See also Tom Ginsburg. (2003). Judicial Review in New Democracies: Constitutional Courts in Asian Cases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

50 Taylor Cole. (1958). The West German Federal Constitutional Court: An Evaluation after

18 focus of the research, it will assess the role of the Constitutional Court in consolidating democracy in Indonesia.

The limitation of the research includes the avoidance of discussion more on political matter. Although in particular chapters, it discusses on the issues of democracy and democratic consolidation, the focus of the research definitely is more on constitutional law perspective relevant to the specialized area of the researcher. However, to some extent, if the discussion touches the political issues, it is knowledgeably admitted that constitutional law and politics is like “bones” and “meat” in one body. Constitutional law is the bones and the latter is politics.

It is also worth mentioning that the limitation of the research is in terms of period of judges which is used as the background of the research. The period of judges that will be used is from 2003 to 2008 and from 2008 to 2012. This period is almost a decade after the emergence of the Constitutional Court in Indonesia. The data collection and analysis will use random sampling by choosing representative judges in each period to be interviewed by preparing list of questions.

In addition, it is also important to be noted that the analysis of the research will focus on the existing authorities of the Constitutional Court lies in the 1945 Constitution and the Constitutional Court Act. According to Article 10 of Act, the Constitutional Court is authorized to hold trials at the first and final stage and will produce final decisions on the following: a) review the laws against the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia; dispute settlement over the powers of state institutions whose authorities are mandated by the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia; dissolution of political parties; and disputes on the result of general election.

19 Court i.e. review of acts, dispute settlement over the authorities of state institutions and dispute on the result of general election. The rest of authorities i.e. deciding dissolution of political parties and one obligation to decide case relating to impeachment of President and/or Vice President will not cover in this research since there is no case relating to the matter.

This research will be conducted by using qualitative and quantitative approach. The research will take Jakarta and Yogyakarta as main places of collecting data. The data will be taken through library research and interviews. Library research will conducted in Constitutional Court Library and some constitutional law experts will be interviewed deeply to examine accuracy of any documents gathered. Some state organs and NGO’s and other relevant institutions will be samples for field research. Comparative study on the role of the Constitutional Court in relevant countries will be conducted to enrich the quality of research such as Germany or South Korea.

1.8. Methodology Type of Research

The type of this research is a doctrinal legal research51. In this regard, the research will study the concept and the implementation of the role of Constitutional Court during the democratic consolidation in Indonesia. The researcher will seek to collect and then analyze some relevant cases that have decided by the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Indonesia, together with any relevant legislation (so called primary sources). The research also involves a historical perspective study as well as may include secondary sources such as journal articles or other written commentaries on the case law and legislation relating the Constitutional Court and its role in consolidating democracy in Indonesia.

Method of Research

This research will be conducted by using both qualitative and quantitative approach. The research will take Jakarta and Yogyakarta as main places of collecting data. The data will be taken through library research and interviews.

51 See further Ian Dobinson and Francis Johns in Research Method of Law edited by Mike

20 Library research will conducted in Constitutional Court Library and some constitutional law experts will be interviewed deeply to examine accuracy of any documents gathered. Some state organs and NGO’s and other relevant institutions will be samples for field research. Comparative study on the role of the Constitutional Court in relevant countries will be conducted to enrich the quality of research such as United States, Austria, Germany and South Korea.

To support the accuracy of reading materials from library research, interview with some constitutional law experts as well as political sciences experts will be conducted. Some of the experts are Prof. Jimly Asshiddiqie (UI, former chairman of the Constitutional Court), Prof. Mahfud MD (UII, the chairman of the Constitutional Court), Prof. Saldi Isra (Andalas University), Prof. Laica Marzuki (Unhas), Prof. Aidil Fitriciada Azhari (UMS), Prof. Denny Indrayana (UGM), Prof. Pratikno (UGM), Prof. Purwo santoso (UGM), Prof. Yusril Ihza Mahendra (UI), Haydar Gumay MA (CETRO), Dr. Ni’matul Huda (UII).

Data Collection

In terms of library research, data will be collected such as journals, periodicals, books, newspapers, legislation, Constitutional Court decisions, the internet and other assorted secondary materials regarding the process of the emergence of the Constitutional Court in 2003 and the role of the Constitutional Court in democratic consolidation in 2003-2012.

The interviews will focus on the interviewees’ own direct experience of the emergence of the constitutional court and their comments on the evaluation of the Constitutional Court’s achievements and problems after 10 years of the establishment. For guidance, the interviews will be directed by a list of questions.

Data Analysis

21 evaluating the role of the Constitutional Court in democratic consolidation in Indonesia. Specifically, in analyzing decisions made by the Court, some constitutional interpretation such as literal, purposive, activism, judicial restraint, historical interpretation will be used. The evaluation will produce description of achievements and shortcomings of the role of the Constitutional Court and recommendations that can be proposed for a better role of the Constitutional Court in the future in Indonesia.

1.9. Chapterization

The research will discuss “the role of the Constitutional Court during the process of democratic consolidation in Indonesia”. The discussion consists of seven chapters as follows: Chapter One will discuss the basic guideline of the research including background, statement of problem, objectives of the study, hypothesis, scope and limitations, literature review, and methodology.

Chapter two will explore some issues namely the definition of constitutional adjudication and the ground of constitutional adjudication in various jurisdictions. The chapter also discusses the origin and development of constitutional adjudication. To deepen the understanding, the research describes the discourse on the concept of constitutional adjudication since there is discourse among the proponents and the opponents of the concept constitutional adjudication. Discussing on various types (model) of constitutional adjudication in the world also would be conducted in order to enrich the understanding more on the concept of constitutional adjudication. Lastly, the chapter also highlights some important issues regarding the concept of constitutional adjudication.

22 highlights the critical period that lead the founding of new constitutional order following the departure of Soeharto in 1998 and points out debate on the emergence of constitutional court in Indonesia.

Chapter four will consist of discussion on the foundation and constitutional bases of the Constitutional Court. At this stage, it will convey the powers of the constitutional court as well as the nature of the Constitutional Court. Discussion on procedures of the Constitutional Court will also be part of the discussion. The chapter will end up by highlighting some strengths as well as weaknesses of the constitutional court.

Chapter five will mainly discuss on the major constitutional developments and the working of democratic consolidation in Indonesia. The sub topic will be derived into some issues such as discussion on amendment of the 1945 Constitution and critical comments on relevant issues. The chapter will also elaborate the definition and the concept of democratic transition, democratic consolidation as well as what is meant by mature democracy. Problems and challenges of democratic consolidation will also strengthen the process of democratic consolidation toward a mature or established democracy in Indonesia.

In chapter six, discussion will focus on review of major Constitutional Court decisions 2003-2013. The focus will mainly convey the review and comments on Constitutional Court decisions pertaining to judicial review of acts, disputes settlement over the result of elections, and disputes settlement on authority among state institutions. Then, by analyzing the Constitutional Court decisions, the chapter will answer how the role of the Constitutional Court in the working of democratic consolidation in Indonesia. In order to have a critical assessment, the chapter will end up by discussing the problems and the challenges of the Constitutional Court in the working of democratic consolidation toward a mature or established democracy.

24 CHAPTER TWO

THE COURT IN CONSTITUTIONAL ADJUDICATION

2.1 INTRODUCTION

To understand further the framework of constitutional adjudication comprehensively, in this chapter, it will discuss definition of constitutional adjudication, the origin and development of constitutional adjudication, elaborate the ground of constitutional adjudication in various jurisdictions which discourse the debate on justification and objection to the existence of constitutional adjudication, and explore some models of constitutional adjudication that are different among countries. At the end of the chapter, it will also conduct survey and highlight some important issues on the various jurisdictions of constitutional adjudication in relevant countries.

2.2 Defining Constitutional Adjudication

There are some terms that should be understood properly in this thesis since the terms are the main terms that would be used in the discussion regarding the topic. The terms are constitutional adjudication, judicial review, constitutional review, constitutional preview or preventive constitutional review. In this below paragraph, it will explain the basic meaning of each term in order to avoid improper understanding on the issues.

Constitutional adjudication is a system of rectifying, in the name of constitution, violation of constitutional values and thereby maintaining the fundamental value-order inherent in the constitution. It refers to a system that seeks to protect the people’s basic rights by making sure the constitution is respected as the supreme law in actual practice. More concretely, it seeks to protect the constitutional order and implement the constitution by having either regular courts or a separate constitutional institution make an authoritative determination according to the constitution when cases arise in which violation of the constitution (e.g., infringement of basic rights) are alleged.52

25 In liberal democratic states, constitutional adjudication is also means of defending the constitution, and functions as a powerful restraint on state power. This is why it is now regarded as one of essential constituent principles of government structure, along with system of representation, separation of powers, periodic elections, local autonomous, etc. In addition, constitutional adjudication contributes to the substantive rule of law by subjecting the exercise of state power to the requirement of constitutionally guaranteed basic rights, which in turn secures the procedural legitimacy of state power.53 Constitutional adjudication term is closely related with term “judicial review” since judicial review is a part of constitutional adjudication mechanism.

Before continuing further, it is better to begin with a brief account of what meant by judicial review. What meant by judicial review in this study is about judicial review of legislation, not judicial review of executive action or administrative decision making.54 Another term that is usually used is constitutional review. This distinction should be clearly understood, at least, because two reasons. First, constitutional review-besides exercising by judges-is also able to be exercised by other organs mandated by Constitution. Second, concept of “judicial review” has a broader sense in term of its objects, for instance, including review on the regulation under the statutes enacted by legislature, while “constitutional review” only relates to review on statutes made by legislature, whether are compatible with constitution or not.55

Regarding the organs mandated by the constitution, some countries give authority to a special court that called “constitutional court” such as in many European countries and some countries give authority to the ordinary courts: Supreme Court as like in the United States. France mandates its authority to a different organ which is not a court, but it is like a council, called “Conseil Constitutionnel”. Counseil Constitutionnel is a political organ, not a court. If term “judicial review” is used, it means that the organ is a court.56

53 Ibid.

54 In Indonesian legislation process, executive branch is also involved although the authority

of making legislation lies in the hand of legislature, called Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat or DPR.

55 Jimly Asshiddiqie, Model-Model Pengujian Konstitusional di Berbagai Negara, (Jakarta,

Konstitusi Press, 2006), 2-3.

26 Other distinction of terms that should be understood is judicial review and judicial preview. Judicial review is a review on “posteriori abstract norms” of legislation which is enacted by parliament, while judicial preview is a review in “a priori abstract norms of legislation which is agreed by parliament, but not yet officially enacted. If the review uses constitution as parameter, it is called “constitutional review” of legislation. If the review uses statutes as the parameter, it is usually named as judicial review on the legality of regulation. Therefore, it should be differentiated between constitutional review and legal review.57 Other different terms used are abstract review and concrete review. If review on abstract norms (regeling), it is called as area of constitutional law issues. While the review on the concrete norm and individual, it is called as judicial review in the area of administrative court.

2.3 The Origin and Development of Constitutional Adjudication

Historically, constitutional adjudication is much older and more deeply entrenched in the United States than in Europe. Judicial review as a part of constitutional issues have been implemented continuously in the United States since the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803). While constitutional review in Europe, however, is largely a post–World War II phenomenon.58

In pre-World War II Europe, democratic constitutions could typically be revised at the discretion of the legislature; they prohibited review of the legality of statutes by the judiciary; and they did not contain substantive constraints, such as rights, on the legislative authority. The rule of legislative supremacy meant that conflicts between a statute and a constitutional norm were to be either ignored by judges, or resolved in favor of the former.59 One of remarkable political developments of the twentieth century has been the development of constitutional

57 Ibid, 7.

58 See Michel Rosenfeld, Constitutional Adjudication in Europe and the United States:

Paradoxes and Contrast, International Journal of Constitutional Law, No 4 (Oct. 2004). See also Anna Gamper, On the Justiciability and Persuasiveness of Constitutional Comparison in Constitutional Adjudication, Online International Journal of Constitutional Law, vol.3, no. 3(2009), 154.

59 Alec Stone Sweet, Governing with Judges: Constitutional Politics in Europe, (New York:

27 democracy in Europe after World War II. The defeated powers in the western part of continent adopted new constitutions that embrace notions of individual rights and limited government60. In other words, since the end of World War II, a ’new constitutionalism’ has emerged and widely diffused. Human rights have been codified and given a privileged place in the constitutional law; and quasi judicial organs called constitutional courts have been charged with ensuring the normative superiority of the constitution. Such courts have been established in Austria (1945), Italy (1948), the Federal Republic Germany (1949), France (1958), Portugal (1976), Spain (1978), Belgium (1985), and after 1989, in the post-Communist Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, the Baltics, and several states of the former Yugoslavia.61

Throughout the history of mankind, the idea of higher and more fundamental law to which all acts of the state must conform has had long tradition. With the emergence of written constitutions in the modern era, the constitution was understood to be the embodiment of such higher and more fundamental law. This provided the theoretical basis for the system of constitutional adjudication which allows for the overruling of operations of the state that do not conform to the constitution.62 The experience in particular countries shows that parliamentary sovereignty also create problem of hegemony of majority which has potentiality to ignore minority. Therefore, the concept of constitutional democracy emerged to control the tyranny of majority.

Let’s take for example of two major traditions regarding the constitutional adjudication, American tradition and European tradition. To flower the history of this issue, history of constitutional adjudication in some Latin America, Eastern Europe and Asian countries will also be part of further discussion. From the history, we may highlight that classical concept of separation of powers where the parliament is considered as the representative of the will of people had been left. Parliament sovereignty has been replaced by idea of constitutional democracy

60 John Ferejohn and Pasquale Pasquino, “Constitutional Adjudication: Lesson form Europe”, Texas Law Review, vol. , no. (2004):1

61 Alec Stone Sweet, 31.

28 where put the constitution as the supreme law. Therefore, the parliament decisions have to subject to the constitution.

Looking at back to the historical background, there are at least three waves of the constitutional adjudication history, namely United State of America tradition, European tradition, Latin America, Eastern Europe tradition and Asian tradition. To understand further the history, in the below paragraph, it will highlight the history of each tradition of constitutional adjudication. Although the idea of constitutional adjudication has spread over the world, in this paragraph, the discussion will focus more on the three waves of the emergence of constitutional adjudication.

1. US History (1803)

Constitutional adjudication is as old as democratic constitutionalism. But for a long period of time, United State of America (USA) remained alone in subjecting democratic decision- making to judicial review. While constitution had become widely accepted already in the 19th century, it took almost two hundred years until constitutional adjudication has gained world-wide recognition. In the 19th century, only Switzerland entrusted its Supreme Court with competencies in the field of constitutional law, yet, not including review of federal legislation. All other attempts to introduce constitutional adjudication failed. This is also true for Germany where the constitution of 1849 had provided for judicial review in ample manner. But the constitution adopted by the revolutionary Paulskirchen Assembly did not enter into force because the monarchs refused their consent after the revolution had been put down.63

Historically, the Americans may have been the first to grapple with the concept of constitutional review, but they were certainly not the last. The common law world has observed the legacies of Marbury v. Madison64 with a mixture of trepidation and envy. It discomfort with

63 Dieter Grimm, Constitutional Adjudication and Democracy, Israel Law Review, vol 32 no

1-4 and vol.33, no 1.

64 See further Sylvia Snowiss, Judicial Review and the Law of the Constitution, (New Haven

29 the judiciary’s power to nullify the legislative commands of an elected majority eventually prompted various commonwealth legislatures to initiate their own unique constitutional responses to the intricate conundrum of balancing legislative supremacy with judicial protection of human rights.65 After the universal declaration of human rights, many countries are actually influenced by the idea of protection of fundamental human rights. At the same time, the practice of parliament sovereignty also emerged the fear of hegemonic of majority which is considered a threat to minority. Hence, many legal scholars then created a new paradigm which is able to control the hegemony of majority in parliament by proposing the idea of constitutionalism and constitutional democracy. Constitutional democracy means that the sovereignty of parliament is limited by the constitution.

Ginsburg asserted also that the origin of the practice in the United States may lead us to look for Marbury-type “grand cases” wherein the court asserts its power to overrule political authorities. The danger is that a grand case is not the only way judicial review can be established. Beginning with an American orientation may lead us in the wrong direction by focusing our attention on the search for nonexistent “grand cases” in new democracies. This approach may misread Marbury, which after all did not include any command to a political branch. More accurately, observers looking for “grand cases” Marbury; and from Marbury to the end of Marshall’s tenure on the Court. During the first period judicial authority over unconstitutional acts was often claimed but its legitimacy was just as often denied. Period 2 judicial review was not derived from the written constitution per se, as Marbury

suggests, but form the existence in the American states of real, explicit social contracts or fundamental law which came into being in the aftermath of the revolutionary break from England. Period 2 judicial review, furthermore, derived its authority over legislation form an equality of the governmental branches under explicit fundamental law, not, as does the Marbury doctrine, from a uniquely judicial responsibility to a written constitution. Period 3 began with Marshall’s assumption of the chief justiceship and consisted of his reworking of the period 2 position. Marshall’s key innovations did not come in Marbury, which was only a peculiarly worded restatement of the ground already won in period 2, but in the way he treated the Constitution in his opinions of the 1801s and 1802s.

65 Po Jen Yap, Rethinking Constitutional Review in America and the Commonwealth: Judicial

30 that establish institutions of judicial review have in mind Brown v.

Board of Education (1954) where the Supreme Court overturned the

American caste system with a single blow.66 In this case, the Court held that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment forbade race-based discrimination in the public schools.67

Robert Post added that constitutionalism, at least in the United States, entails the institution of judicial review, in which courts determine whether to strike down otherwise perfectly legitimate enactments that are presumed to reflect the popular will. Sometimes, as in First Amendment jurisprudence, these enactments are invalidated on the ground that they are inconsistent with a freedom of expression that is deemed “vital to the maintenance of democratic institutions. In such circumstances, the First Amendment is characterized as “the guardian of democracy.”68 In other words, the courts become the guardian of the constitution which guarantee the fundamental rights if citizens by ensuring that no enactments are in contradiction to the constitution. 2. European History (1920)

By contrast, in various nations of Europe, where the ideals of popular sovereignty and representation were relatively stronger, it was considered improper to allow ordinary courts to review the constitutionality of legislations made by the representatives of the people.69 For example, the 1911 Constitution of Portugal adopted the system of judicial review under the influence of the American constitution, but it failed to take root. The origins of constitutional adjudication on the Continent must be traced back to the 1920 Federal

66 See Tom Ginsburg, Judicial Review in New Democracies, 17.

67 Richard H. Fallon, Jr, The Dynamic Constitution: An Introduction to American Constitutional Law, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 23. This is one of the landmark’s decision made by the US Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warrant in 1954. The Court declared state laws establishing separate schools for black and white students unconstitutional. The decision overturned the Plessy v. Ferquson decision of 1896 which allowed state-spomsored segregation. Some argue that this decision is more relevant substantively in relation to the issue of judicial review compared to Marbury v. Madison.

68 Robert Post, Democracy, Popular Sovereignty, and Judicial Review, California Law Review, Vol 86 No 429 (1998), 437.

31 Constitution of Austria which established a constitutional court at the recommendation of the famous jurist Hans Kelsen. This court was authorized to rule on the constitutionality of federal statutes. The German 1919 Constitution of Weimar Republic did provide for a State Court (Staatsgerichtshof) which was empowered to decide on issues of impeachment and constitutional disputes between the governments of the federal republic (Reich) and the provinces (Lander). There were, however, no provisions on review of the constitutionality of federal statutes or on jurisdictional disputes between agencies of the federal government.70

It was natural that the early proponents of democracy supported parliamentary sovereignty. The saw threats to liberty form the traditional sources: the ancient regime, the monarch, and the church. Once these formidable obstacles to popular power had been overcome, theorists could hardly justify limitations on the people’s will, the sole legitimate source of power. As democratic practice spread, however, new threats emerged. In particular, Europe’s experience under democratically elected fascist regimes in World War II led many new democracies to recognize a new, internal threat to the demos.71 A Democratically elected regime also had opportunity to threat basic liberties of the people. Therefore, the idea to limit the power elected bodies was appeared in the light of protecting basic rights of people. The ideal of limited government, or constitutionalism, is in conflict with the idea of parliamentary sovereignty. This tension is particularly apparent where constitutionalism is safeguarded through judicial review. One governmental body, unelected by the people, tells an elected body that its will is incompatible with fundamental aspirations of the people. This is at the root of the “counter-majoritarian difficulty,” which has been the central concern of normative

70 Annual Report, 20 Years of Constitutional Court of Korea, 65