Attachment State of Mind, Learning Dispositions, and Academic

Performance During the College Transition

Simon Larose

Universite´ Laval Universite´ de Montre´al

Annie Bernier

George M. Tarabulsy

Universite´ LavalThe purpose of this study was to examine the relation among attachment state of mind, students’ learning dispositions, and academic performance during the college transition. Sixty-two students were involved in a short-term longitudinal study and were interviewed with the Adult Attachment Interview. Students’ learning dispositions were assessed at the end of high school (Time 1) and halfway through their 1st semester in college (Time 2). Academic records were collected at Time 1 as well as at the end of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd college semesters. Autonomous students showed better learning dispositions throughout the transition and were less likely than dismissing and preoccupied students to experience a decrease in these dispositions between Time 1 and Time 2. In addition, dismissing students obtained the lowest average of grades in college, and this association was mediated by changes in quality of attention during the transition.

After decades of research on the links between attachment organization and socioemotional functioning (for reviews, see Thompson, 1999; Weinfield, Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson, 1999), the recent years have given rise to a growing interest in the association between attachment and different indices of academic achievement (e.g., Bernier, Larose, Boivin, & Soucy, 2004; Jacob-sen & Hofmann, 1997; Moss & St-Laurent, 2001; Teo, Carlson, Mathieu, Egeland, & Sroufe, 1996). These studies suggest that security of attachment, assessed at different developmental peri-ods, is consistently associated with higher school marks than insecurity. Although fascinating, such findings cannot be easily explained by attachment theory. Because academic achievement is a critical aspect of children’s and adolescents’ adaptation, related to academic perseverance (Ekstrom, Goertz, Pollack, & Rock, 1986) and mental health problems during adulthood (Caspi, Elder, & Bem, 1987), it is important to understand the processes linking attachment security and academic achievement. In the current study, we had two goals: (a) to investigate the relation between

college students’ attachment state of mind and their cognitive, behavioral, and emotional dispositions toward learning and school-work and (b) to test whether the presumed relation between at-tachment and academic performance can be accounted for by students’ learning dispositions during the college transition.

Attachment and Exploration

A key concept in attachment theory is that the attachment and exploration systems are interdependent (Bowlby, 1982) and that security consists of a balance between attachment and exploration (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). The secure base concept implies that security of attachment promotes competent exploration of the surrounding world by providing the child with the confidence that someone will be there to protect him or her should a threat arise during exploration (Bowlby, 1982) and with the self-confidence necessary to engage in exploration of the environment with assurance (Jacobsen, Edelstein, & Hofmann, 1994). Ainsworth (1990) further described exploration as includ-ing not only a general interest about the world but also “interest in gaining knowledge about the environment” (p. 473).

Neither Bowlby (1982) nor Ainsworth (1990) have, however, offered insight regarding the scope of the spheres of personal functioning that fall under exploration and that can thus be ex-pected to relate to attachment. Perhaps as a result of this lack of conceptual guidance from classic writings, contemporary attach-ment researchers are divided on the question of the nature of the spheres of adjustment that should be linked to attachment organi-zation. The issue of the relation between attachment and academic performance is thus open to speculation. Weinfield et al. (1999) argued that attachment organization should play a role primarily in beliefs about self and others, in the interpersonal and emotional domains, and within the relationships with the parents. Along those lines, Sroufe (1988) suggested that attachment should be Simon Larose, Groupe de recherche sur l’inadaptation psychosociale

chez l’enfant, De´partement d’e´tudes sur l’enseignement et l’apprentissage, Universite´ Laval, Que´bec, Canada; Annie Bernier, De´partement de psy-chologie, Universite´ de Montre´al, Montre´al, Que´bec, Canada; George M. Tarabulsy, Groupe de recherche sur l’inadaptation psychosociale chez l’enfant, E´cole de Psychologie, Universite´ Laval, Que´bec, Canada.

This study was made possible by funding from the Fonds pour les chercheurs et l’avancement de la recherche and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

We thank Jocelyne Gagnon, who provided invaluable assistance in coding Adult Attachment Interviews.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Simon Larose, De´partement d’e´tudes sur l’enseignement et l’apprentissage, Fac-ulte´ des Sciences de l’E´ducation, Universite´ Laval, Que´bec G1K 7P4, Canada. E-mail: [email protected]

related to a number of aspects of school adjustment, yet not to school grades.

In contrast, Grossmann, Grossmann, and Zimmermann (1999) proposed a wider view of the correlates of attachment with their concept of “security of exploration.” According to these authors, quality of exploration constitutes the functional and adaptive com-ponent of security of attachment. On the basis of early observa-tions to the effect that individual differences in quality of explo-ration were among the first outcomes found to be associated with attachment quality (Main, 1973), they argued that attachment theory integrates a need for security (the attachment system) and a need to explore (the exploratory system). According to Grossmann et al., a broad range of developmental outcomes is likely to be related to attachment, because open-mindedness and a careful but curious orientation to reality are direct consequences of attachment security. Security of attachment would thus favor competent ex-ploration and therefore academic competence.

Attachment and Academic Performance

Findings from several studies can help explain the mechanisms through which attachment may be related to academic perfor-mance in childhood and beyond. Toddlers with secure attachments to both parents are more eager to complete the Bayley scales (Grossmann et al., 1999), whereas secure preschoolers engage in more spontaneous reading (Bus & van IJzendoorn, 1988). Insecure toddlers are less enthusiastic, less effective, and show less endur-ance during a challenging task than their secure counterparts (Matas, Arend, & Sroufe, 1978). Grossmann et al. (1999) observed that 3-year-olds who had been insecure became less efficient at problem solving when faced with a possible failure, whereas the former securely attached children showed the opposite pattern. Further, Meins (1997) found that secure children showed superior search behavior at 1 year of age, larger vocabularies at 19 months, and were more likely than their insecure peers to pass a test assessing understanding of others’ minds at 4 years. Finally, Ja-cobsen et al. (1994) found longitudinal relations between attach-ment at age 7 and concrete and formal operational reasoning between ages 7 and 15 and formal deductive reasoning between ages 9 and 17. Securely attached children consistently did better than their insecure peers, even when controlling for IQ and atten-tion problems.

More recent studies have taken the issue one step further by showing that attachment quality, whether assessed with behavioral (Moss & St-Laurent, 2001; Teo et al., 1996), representational (Jacobsen & Hofmann, 1997), or interview measures (Bernier et al., 2004), is associated with academic performance at different developmental periods. Hence, Teo et al. (1996) found associa-tions between attachment in infancy and academic performance during adolescence, whereas Moss and St-Laurent (2001) reported relations between 6-year-old attachment behaviors and school achievement at age 8. Further, Jacobsen and Hofmann (1997) found that children who were securely attached at age 7 got higher school grades than insecure ones from ages 7 to 17, whereas Bernier et al. (2004) reported that an insecure-preoccupied attach-ment state of mind is related to a drop in school marks during the transition from high school to college.

These findings open new avenues for attachment research, in that they cannot be readily explained by the original propositions

of Bowlby (1982) and Ainsworth (1990), which were mainly of a socioaffective nature. Moss and St-Laurent (2001) suggested that secure attachment is associated with a greater ability to meet the academic demands of school than insecure attachment, because the positive internal working model of the self, derived from a secure attachment relationship, may encourage the development of the child’s motivation and perceived competence in this context. Their results, and those of Jacobsen and Hofmann (1997), support this assumption by revealing a positive association between secure attachment and goal orientation as well as perceived academic competence. Jacobsen and Hofmann further reported that secure children showed greater attention and participation in class and that these positive behaviors in school partially accounted for the relation between attachment and achievement. According to Moss and St-Laurent, these findings suggest that the greater mastery motivation observed in the exploratory styles of secure infants, toddlers, and preschoolers is internalized by middle childhood into an intrinsic, motivational pattern in which learning is valued.

Learning Dispositions and Attachment in the Context of

Transition From High School to College

Pascarella and Terenzini (1991) proposed that work habits and attitudes toward school are determinant predictors of academic success during the college transition. Several studies have sup-ported these claims by showing that learning dispositions such as examination preparation and attention in class predict college success above and beyond high school grades (Britton & Tesser, 1991; Larose & Roy, 1995). Drawing on cognitive– behavioral theories (Bandura, 1986; Beck, 1976; Ellis & Grieger, 1978), Larose and Roy (1995) proposed that learning dispositions com-prise three interrelated personal systems in college students: the belief system, the behavioral system, and the emotional system. For instance, the college student who believes that a person must be gifted in order to succeed (belief system) will tend to invest less time studying the subject matter (behavioral system) and will also tend to exhibit signs of anxiety when faced with situations of evaluation (emotional system). Larose and Roy have shown that these dispositions toward learning and schoolwork are closely associated with college students’ academic performance.

The college transition may pose a challenge to students’ learn-ing dispositions. Students have to adjust to a new social and academic environment at a time when college staff and parents expect them to be more autonomous in managing their academic and personal life than before. They must take greater responsibility than they did in high school for managing their academic progress (registration, changing programs, etc.), showing self-discipline in their studies, taking the initiative to meet their teachers when problems arise, and making decisions about their future. Such tasks make the college transition a context of instability, which may challenge previous learning dispositions.

dis-tressing context, likely to activate students’ attachment system. If this is so, both insecure attachment states of mind (dismissing and preoccupied) could have a negative impact on students’ learning dispositions by activating their usual maladaptive coping style. Hence, preoccupied students may become overwhelmed with the social and emotional turmoil of the transition and thus fail to meet the academic demands of college, whereas dismissing students may avoid the challenge altogether, notably by investing few interpersonal resources into the academic experience (e.g., not seeking help from teachers and peers). In contrast, security of attachment should constitute a personal resource for adapting to the social and academic challenges of the transition. It is therefore expected that a secure attachment state of mind will be related to better learning dispositions during the college transition, to a lesser impact of the transition on these dispositions, and thus to higher grades in college than insecure states of mind.

Learning Dispositions as Mediating the Effect of

Attachment on Academic Performance

Some of the studies reviewed previously have indicated that secure attachment is associated with greater ability to meet the academic demands of school than insecure attachment, at least in the elementary school period (Jacobsen & Hofmann, 1997; Moss & St-Laurent, 2001). Furthermore, the association between learn-ing dispositions and academic performance is well documented in the literature (see Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991). On the basis of those studies, it is expected that learning dispositions will mediate the link between security of attachment and academic perfor-mance. Attachment security will provide students with a context favorable for the healthy management of negative emotions. This may allow students to better cope with new and potentially stress-ful situations, like starting college, and to use learning strategies adapted to these situations (e.g., talking to their peers or teachers about their problems, being well prepared for examination), thereby facilitating academic performance.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Sixty-two French-speaking Caucasian adolescents (31 male adolescents and 31 female adolescents), aged 16 to 17, were randomly selected from a sample of 298 participants involved in a longitudinal study of adjustment to college (Larose & Boivin, 1998). The focus on a subsample of partic-ipants for the administration of the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI; George, Kaplan, & Main, 1996) was due to financial and practical consid-erations; this project was part of a doctoral dissertation that required all AAIs to be administered and coded within a year and a half. All partici-pants attended the same college, located in the Que´bec City area (Canada). Almost 43% had to leave home to attend college. The majority (82.5%) were from intact two-parent households. Average income of the parents ranged from $10,000 to $19,999 for the mother and from $40,000 to $49,999 for the father. Level of education averaged 12.6 years for the mother and 13.1 years for the father. Participants were met at the end of high school (Time 1) and during their first semester in college (Time 2) and completed on both occasions the Test of Reaction and Adaptation to College (TRAC; Larose & Roy, 1995). The AAI, conducted at Time 2, was used to assess attachment state of mind. Academic records were collected at the end of high school as well as the end of each of the first three semesters in college.

Measures

Attachment state of mind: AAI (George et al., 1996). The AAI is a face-to-face semistructured interview focusing on childhood attachment experiences with one’s parents and on the integration of these experiences into a coherent view of the self, the parents, and attachment relationships. Participants are asked to describe their relationships with their parents when they were young, to substantiate descriptions with specific memories, to recall incidences of distress, and to conceptualize relationship influences.

The interview is recorded and then transcribed, and its content is rated on two sets of scales according to Main and Goldwyn’s (1998) classifica-tion system. The participant’s childhood relaclassifica-tionship with each parent is rated on a first set of five 9-point scales: Love, Rejection, Role Reversal, Pressure to Achieve, and Neglect. In a second step, the participant’s state of mind with regard to these experiences is rated on 12 scales: Idealization (of mother and of father), Lack of Recall, Anger (toward mother and toward father), Derogation, Metacognitive Monitoring, Passivity, Unre-solved Loss, UnreUnre-solved Trauma, and Coherence of Transcript and of Mind. Finally, the score pattern of these scales is used to classify each participant into one of the following attachment categories: free– autonomous (F), enmeshed–preoccupied (E), dismissing (Ds) or unre-solved (U). The AAI has been shown to have excellent reliability, dis-criminant validity, and predictive validity (see Hesse, 1999, for a review). The study participants were randomly assigned to two interviewers (one male, one female). These interviewers were graduate students in psychol-ogy who attended the Adult Attachment Institute in Charlottesville, Vir-ginia, during the summer of 1993. The interviews were conducted accord-ing to the protocol developed by George et al. (1996). They lasted from 45 to 90 min and took place in a quiet room provided by the college. Transcriptions were made by a professional secretary following directions provided by Main (1994). Simon Larose, who has successfully completed four fifths of the reliability certification process with M. Main and E. Hesse, rated each interview. Fifteen interviews were also coded by a second independent judge (Jocelyne Gagnon), fully certified as reliable by M. Main and E. Hesse. The two coders were blind to other measures as well as to the identity and gender of the participants. Agreement on the three-group classification was 80% with a kappa of .60. The four-way agreement was the same, as none of the 15 interviews was rated unresolved by either judge. Two problematic cases were resolved in conference with Annie Bernier (also fully certified as reliable by M. Main and E. Hesse).

Learning dispositions: TRAC (Larose & Roy, 1995). This 50-item questionnaire taps students’ beliefs, emotional reactions, and behaviors in learning situations and was developed within the theoretical confines of social-cognitive theories, specifically those proposed by Ellis and Grieger (1978) and Beck (1976). It contains nine subscales measuring three com-ponents: the emotional component related to evaluation (Examination Anxiety [EA; e.g., “During exams, I sweat more than on other occasions”; 10 items], Fear of Failure [FF; e.g., “I sometimes think that if I fail an exam, I will flunk out of school”; 7 items]), thebehavioral component

(Examination Preparation [EP; e.g., “When I take an exam, I have studied all of the relevant material”; 6 items], Quality of Attention [QA; e.g., “While studying, I have too many other things on my mind to fully concentrate on the task”; reverse coded, 6 items], Seeking Help From Teacher [SHT; e.g., “I hesitate to ask for help from my teacher when I need to have something cleared up”; reverse coded, 5 items], Assistance From Peers [AP; e.g., “When I’m sure that I do not understand a problem or an idea, I ask other students for help as soon as possible”; 4 items], Giving Priority to Studies [GP; e.g., “I have difficulty dedicating a lot of time and energy to academic success”; reverse coded, 4 items]), and finally the

hard”; 4 items]). Items are answered on a 7-point scale (1⫽never; 7⫽

always).

The TRAC has been shown to have good psychometric properties including clear factor structure and good concomitant and predictive va-lidity (see Larose & Roy, 1995). In this study, Cronbach’s alphas for the EA, FF, EP, QA, SHT, AP, GP, BWM, and BE subscales were, respec-tively, .93, .87, .80, .76, .70, .78, .70, .60, and .68 at Time 1 and .95, .93, .86, .78, .62, .82, .77, .68, and .74 at Time 2. Intercorrelations between subscales ranged from⫺.06 to .74 at Time 1 (absoluteM⫽.40) and from ⫺.03 to .66 at Time 2 (absoluteM⫽.36). Of a total of 36 correlations at each time, 29 were significant at Time 1 and 26 were significant at Time 2 (p⬍.05).

Academic Performance

Students’ high school weighted academic average (HSWAA) as well as standardized general mean (SGM) after their first, second, and third se-mesters in college were collected from official records. The HSWAA is a standardized index based on academic records during the last 3 years of high school. It has been identified as the best predictor of college success in the province of Que´bec (Terrill, 1988). The SGM is the average of all grades attained by a student during a semester in a common core of courses required for graduation. Courses that are failed or dropped by students receive a score of 50 in the computation of SGM. SGM during the first 2 years in college is strongly associated with college persistence and likeli-hood of graduating and predicts academic performance at the university level (Terrill, 1988).

Results

Attachment classifications were distributed as follows: 35 par-ticipants were classified as autonomous (56.5%), 17 as dismissing (27.4%), and 10 as preoccupied (16.1%). Only 1 participant was classified as unresolved. Specifically, he was classified as unre-solved and enmeshed–preoccupied. In line with the procedure proposed by Hesse (1999), this participant was assigned his sec-ondary classification (enmeshed–preoccupied). This distribution is consistent with those reported in typical adolescent samples (e.g., Van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1996). As reported in a previous article (Larose & Bernier, 2001), this AAI distribution was not related to demographic and family variables. Finally, no significant links were found between the dependent variables (TRAC scores and academic achievement) and family variables such as parental income and education, parental status (i.e., intact two-parent households vs. nonintact families), and living away from home.

The results are presented in four main steps. First, zero-order correlations between learning dispositions and indicators of aca-demic performance are presented. Second, a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) on the nine TRAC subscales (learn-ing dispositions) was performed with the AAI classification vari-able as a between-subjects factor, the transition varivari-able (Time 1 vs. Time 2) as a within-subject factor, and the HSWAA variable as a covariate. We included the HSWAA as a covariate to ensure that any relation between attachment and learning dispositions is unique and not confounded by prior academic achievement. Two a priori contrasts were defined on the AAI classification variable, allowing us to compare mean levels of dispositions of dismissing students with those of free–autonomous students (Contrast 1) and mean levels of dispositions of enmeshed–preoccupied students with those of free–autonomous students (Contrast 2). For all

sig-nificant contrasts, partial eta squared values are reported in order to estimate effect sizes. Second, we performed a univariate ANCOVA, using a repeated design, on the SGMs collected after the first, second, and third semesters in college, controlling for HSWAA. The same design as that previously defined was used here (i.e., AAI With 2 Contrasts ⫻ Transition), except that the transition variable was based on three instead of two times. Third, a set of regression analyses was performed to explore the mediat-ing effect of learnmediat-ing dispositions in the presumed association between attachment and academic performance.

Correlations Among Academic Variables

Table 1 presents the zero-order correlations between learning dispositions and indicators of academic performance. Overall, learning dispositions, assessed at Times 1 and 2, are associated with performance during the first semester in college to a greater degree than to previous or later achievement. Specifically, seven of the nine TRAC subscales are significantly related to grades in the first semester, whether they were completed at Time 1 or 2. Quality of examination preparation, priority given to studies, and quality of attention are the learning dispositions that are the most strongly associated with performance during the first semester. These results suggest that the TRAC scales are particularly sensi-tive to the experience of the first semester in college.

Attachment and Learning Dispositions

Means and standard deviations of the nine TRAC subscales are presented in Table 2. The AAI (Wilks’s⫽ .68),F(18, 92)⫽ 2.22,p⬍.01, and the AAI⫻Transition effects (Wilks’s⫽.50), F(18, 92) ⫽ 2.20, p ⬍ .01, were found to be significant. The transition effect was not significant.

With regard to the AAI ⫻ Transition effect, the univariate ANCOVA for Contrast 1 (dismissing vs. free–autonomous) re-vealed the following: Dismissing students experienced a slight decrease in the quality of their examination preparation during the transition (⫺.12), whereas free–autonomous students improved their preparation (.27),t(57) ⫽ ⫺1.97,p⬍ .05,2

⫽.09. Dis-missing students also experienced a decrease in the quality of their attention (⫺.35), whereas free–autonomous students’ quality of attention remained relatively stable (.07),t(57)⫽ ⫺2.10,p⬍.05,

2

⫽ .11. The univariate ANCOVA for Contrast 2 (enmeshed– preoccupied vs. free–autonomous) revealed the following findings: Fear of failure increased during the transition for enmeshed– preoccupied students (.82), whereas it remained stable for free– autonomous students (.06), t(57) ⫽ 2.20, p ⬍ .05, 2

⫽ .08. Giving priority to studies decreased during the transition for enmeshed–preoccupied students (⫺.67), whereas it remained sta-ble for free–autonomous students (.09),t(57)⫽ ⫺2.08,p⬍.05,

2

⫽.07. Finally, the disposition for seeking help from teachers decreased during the transition for enmeshed–preoccupied stu-dents (⫺.89), whereas it remained relatively stable for free– autonomous students (⫺.19),t(57)⫽ ⫺2.33,p⬍.05,2

p⬍.01,2⫽.15, and of attention (6.62 vs. 7.59),t(57)⫽ ⫺2.63, p⬍.05,2

⫽.11, gave less priority to their college studies (5.80 vs. 7.53),t(57)⫽ ⫺3.74,p⬍.01,2⫽.21, and reported more problems with seeking help from teachers (6.38 vs. 7.68),t(57)⫽ ⫺2.29,p⬍.05,2⫽.06. With regard to Contrast 2, enmeshed– preoccupied students showed lower quality of examination prep-aration (5.39 vs. 7.27),t(57)⫽ ⫺3.43,p⬍.01,2⫽.10, and of attention (6.05 vs. 7.60),t(57)⫽ ⫺3.28,p⬍.01,2

⫽.10, and

reported seeking less assistance from peers (6.59 vs. 7.94),t(57)⫽ ⫺2.50,p⬍.05,2

⫽.08, than free–autonomous students.

Attachment and Academic Performance

Means and standard deviations of academic records in high school and for the first three semesters in college are presented in Table 3. The results of the repeated ANCOVA showed an AAI Table 1

Zero-Order Correlations Between Learning Dispositions and Indicators of Academic Performance

TRAC scale HSWAA

SGM after the 1stsemester

SGM after the 2ndsemester

SGM after the 3rdsemester

Time 1

Examination Anxiety ⫺.09 ⫺.01 .11 .10

Fear of Failure ⫺.13 ⫺.31* .03 ⫺.01

Examination Preparation .12 .49** .20 .27*

Quality of Attention ⫺.03 .28* .02 ⫺.06

Assistance From Peers .29* .30* .13 .10

Giving Priority to Studies .18 .39** .20 .28*

Seeking Help From Teacher .02 .20 ⫺.07 ⫺.04

Belief in Effective Methods .04 .27* ⫺.07 .04

Belief in Easiness ⫺.18 ⫺.31* ⫺.05 ⫺.15

Time 2

Examination Anxiety ⫺.10 ⫺.08 .04 ⫺.03

Fear of Failure ⫺.17 ⫺.28* ⫺.18 ⫺.11

Examination Preparation .12 .51** .36** .29*

Quality of Attention ⫺.02 .35** .28* .21

Assistance From Peers .02 .28* .19 .17

Giving Priority to Studies .27* .45** .42** .29*

Seeking Help From Teacher ⫺.08 .28* .15 .09

Belief in Effective Methods .08 .04 ⫺.08 ⫺.11

Belief in Easiness ⫺.12 ⫺.27* .02 ⫺.16

Note. TRAC⫽Test of Reaction and Adaptation to College; HSWAA⫽High School Weighted Academic Average; SGM⫽Standardized General Mean; Time 1⫽end of high school; Time 2⫽halfway through student’s first semester in college.

*p⬍.05. **p⬍.01.

Table 2

Means and Standard Deviations for Scores of Learning Dispositions at the End of High School (Time 1) and the Middle of the First College Semester (Time 2)

TRAC scale

Free–autonomous (n⫽35)

Dismissing (n⫽17)

Enmeshed–preoccupied (n⫽10)

Time 1 Time 2 Time 1 Time 2 Time 1 Time 2

M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD

Examination Anxiety 2.58 1.21 2.74 1.38 2.62 0.91 2.67 1.06 2.71 0.77 3.31 0.86

Fear of Failure 2.31 1.16 2.39 1.39 2.59 1.06 3.14 1.46 2.30 0.85 3.46 1.53

Examination Preparation 4.97 1.03 5.34 0.99 4.38 1.19 4.21 1.18 3.96 1.55 3.70 1.44

Quality of Attention 5.32 0.74 5.42 0.99 4.93 0.94 4.43 1.17 4.57 0.95 3.98 1.59

Assistance From Peers 5.62 0.93 5.66 1.12 5.16 0.95 4.97 1.09 5.00 1.64 4.36 1.30

Giving Priority to Studies 5.26 1.13 5.39 1.17 4.19 1.14 4.01 1.55 5.19 1.23 4.25 1.04 Seeking Help From Teacher 5.37 1.04 5.49 1.19 4.99 1.43 4.40 1.32 5.47 1.11 4.20 1.37 Belief in Effective Methods 5.48 1.06 5.95 1.06 5.21 0.95 5.71 0.84 6.25 1.05 6.19 1.11

Belief in Easiness 3.68 1.08 2.93 1.18 4.09 1.28 3.48 1.27 3.58 1.09 3.42 1.28

effect,F(2, 52)⫽3.01,p⬍.05. A significant effect was found for Contrast 1 only (dismissing vs. free–autonomous). The averaged SGM of dismissing students was lower than that of free– autonomous students, even after controlling for HSWAA (adjusted Ms⫽121.92 vs. 126.16),t(54)⫽ ⫺2.40,p⬍.05,2

⫽.07. The transition and the AAI⫻Transition effects were not significant. On an exploratory basis, we also examined whether enmeshed– preoccupied and dismissing students differed on learning and academic dispositions. Following the same analytic strategy as that described above while omitting the free–autonomous students, we found an AAI effect (dismissing vs. enmeshed–preoccupied) on the TRAC scores at the multivariate level (Wilks’s⫽.45),F(9, 15)⫽2.80,p⬍.05. However, at the univariate level, only one of the TRAC subscales accounted for this difference: Dismissing students obtained lower scores on BWM than enmeshed– preoccupied students (5.46 vs. 6.21),F(1, 23)⫽5.52,p⬍ .05,

2

⫽.05. There are no other significant differences between the two groups, either on learning dispositions or academic perfor-mance. Overall, the findings thus suggest that secure adolescents differ from their insecure peers on learning and academic dispo-sitions, whereas there are very few significant differences between the two insecure groups in this sample, perhaps because of the low number of dismissing and enmeshed–preoccupied students.

Learning Dispositions as Mediating the Effect of

Dismissing State of Mind on Academic Performance

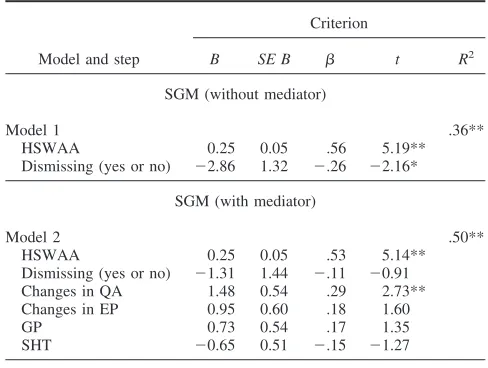

In this final section, we were interested in testing the hypothesis that the effect of a dismissing state of mind on academic perfor-mance could be explained as a function of poor learning disposi-tions and/or fluctuadisposi-tions of those disposidisposi-tions during the college transition. To test mediation hypotheses, Baron and Kenny (1986) suggested conducting three hierarchical regression models. The first model tests the effect of the predictor variable (being a dismissing student or not) on the hypothesized mediator variables (learning dispositions). The second model regresses the predictor variable (being dismissing or not) on the criterion variable (aca-demic performance). The third model regresses both the predictor (being dismissing or not) and the mediator (learning dispositions) on the criterion variable (academic performance).

The previous multivariate analyses performed on Tables 2 and 3 data supported the first two models for certain variables. A dis-missing state of mind was found to be associated with a decrease in students’ quality of attention and examination preparation

dur-ing the transition, with less priority to college studies and with more problems seeking help from teachers. A dismissing state of mind was also found to be associated with poor academic perfor-mance throughout the first 2 years of college. The two regression models presented in Table 4 reveal full mediation of the relation between a dismissing state of mind and academic performance by changes in quality of attention throughout the transition. For theses analyses, attachment state of mind was dummy coded (0⫽ not dismissing; 1⫽dismissing) and the SGMs at the first, second, and third semesters were averaged. In addition, we computed changes in students’ quality of attention and examination preparation dur-ing the transition by subtractdur-ing the Time 1 from the Time 2 assessment. Model 1 (see Table 4) shows that a dismissing state of mind was associated with poor academic achievement in college ( ⫽ ⫺.26) above and beyond academic achievement in high school (HSWAA). Model 2 indicates that when the mediator and predictor variables are included in a hierarchical regression model Table 3

Means and Standard Deviations for Academic Performance

Variable

Free–autonomous (n⫽35)

Dismissing (n⫽17)

Enmeshed– preoccupied (n⫽10)

M SD M SD M SD

HSWAA (high school) 89.71 10.89 87.23 11.75 90.43 9.92

SGM after the 1st semester 83.03 5.94 80.34 3.53 81.26 4.35

SGM after the 2nd semester 83.27 4.99 79.49 6.00 83.07 3.06

SGM after the 3rd semester 84.17 5.01 79.63 4.35 83.03 3.75

Note. HSWAA⫽high school weighted academic average; SGM⫽standardized general mean.

Table 4

Mediation Model Testing Learning Dispositions as Mediator of the Effect of Dismissing State of Mind on Academic

Achievement

Model and step

Criterion

B SE B  t R2

SGM (without mediator)

Model 1 .36**

HSWAA 0.25 0.05 .56 5.19**

Dismissing (yes or no) ⫺2.86 1.32 ⫺.26 ⫺2.16*

SGM (with mediator)

Model 2 .50**

HSWAA 0.25 0.05 .53 5.14**

Dismissing (yes or no) ⫺1.31 1.44 ⫺.11 ⫺0.91 Changes in QA 1.48 0.54 .29 2.73** Changes in EP 0.95 0.60 .18 1.60

GP 0.73 0.54 .17 1.35

SHT ⫺0.65 0.51 ⫺.15 ⫺1.27

Note. SGM ⫽ standardized general mean; HSWAA ⫽ high school weighted academic average; QA⫽Quality of Attention; EP⫽ Examina-tion PreparaExamina-tion; GP⫽Giving Priority to Studies; SHT⫽Seeking Help From Teachers.

simultaneously, only changes in quality of attention during the transition (⫽ .29) explained academic achievement in college beyond academic achievement in high school. It is important to note that the beta score of dismissing state of mind dropped from ⫺.26 (p⬍.05) to⫺.11 (ns). To ensure that the mediation effect was not explained by the number of mediators involved in the analysis, we performed a third regression analysis without the presence of the nonsignificant mediators (i.e., changes in EP, GP, and SHT). In this third analysis, the beta score of dismissing attachment remained nonsignificant (⫺.17,p⫽.13), whereas the beta score related to changes in QA was significant (.31,p⬍.01). Sobel’s tests were performed to verify whether the reduction in the magnitude of the beta coefficient was significant (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Sobel’s test produces aZscore that can be used to evaluate whether the mediation path is greater than 0 when the direct independent-dependent path is taken into account. Sobel’s test indicates a significant reduction in the beta coefficients for the dismissing variable (Z⫽2.01,p⬍.05). This supports the hypoth-esis that a dismissing state of mind leads to poor academic achievement in college notably through its negative impact on students’ quality of attention during the college transition.

Discussion

The first goal of this study was to examine whether students’ attachment state of mind affects their learning dispositions during the college transition. On the basis of the attachment theory and research, we posited as a general hypothesis that attachment secu-rity would constitute a personal resource for adapting to a social and academic transition, thus protecting against a reduction in learning dispositions. The main findings supported this hypothesis. All significant findings involving the transition suggested that nonautonomous students experienced a deterioration of their learn-ing dispositions, whereas those of autonomous students either remained relatively stable or improved. Thus, learning dispositions of autonomous students were less negatively affected by the col-lege transition than those of nonautonomous students. These re-sults are all the more impressive in that we controlled for academic achievement in high school. Thus, attachment security protects against the negative impact of the college transition on learning dispositions beyond what can be explained by previous academic achievement.

The results appear to vary as a function of the type of insecurity. Preoccupied students experienced more fear of failure at the mid-dle of the first semester in college than at the end of high school, felt less comfortable seeking help from teachers, and gave less priority to their studies. On the other hand, dismissing students experienced a decrease in their examination preparation and in their quality of attention during the same period of time. The changes for preoccupied students thus seem to pertain to emotional and social components (i.e., fear of failure, devaluation of learning, and help-seeking problems), whereas those reported by dismissing students appear to be related to practical school-related behaviors (i.e., attention and examination preparation). These two apparently different patterns of findings must, however, be interpreted with great caution, as the exploratory analyses that contrasted dismiss-ing and preoccupied students directly revealed very few significant differences. The most robust findings of this study therefore

per-tain to the autonomous–nonautonomous distinction, rather than to differences between the two nonautonomous groups.

From a theoretical point of view, however, the two possibly different patterns of findings mentioned above are interesting because they would be in line with current theory and recent findings about the differential implications of dismissing and pre-occupied states of mind. A prepre-occupied state of mind is theoreti-cally (Dozier & Tyrrell, 1998; Kobak, Cole, Ferenz-Gillies, Flem-ing & Gamble, 1993; Main & Goldwyn, 1998) and empirically (Dozier & Lee, 1995; Pianta, Egeland, & Adam, 1996) associated with self-reported emotional and social distress, notably during the college transition (Bernier et al., 2004; Larose & Bernier, 2001). The results of the present study suggest that this felt distress may extend to feelings and reactions toward school, impeding preoc-cupied students’ capacity to engage in college-level studies with confidence and an appropriate help-seeking attitude.

In contrast, a dismissing state of mind is theoretically (Dozier & Tyrrell, 1998; Kobak et al., 1993) and empirically (Dozier & Lee, 1995; Pianta et al., 1996) related to problems in acknowledging emotional difficulties but has been shown to relate to social and emotional difficulties, as reported by clinicians and peers (Dozier & Lee, 1995; Larose & Bernier, 2001). Thus, even though dis-missing individuals have a restricted capacity to recognize and report affective problems, they do report adjustment difficulties. The findings of this study, showing that dismissing students report a decrease in the quality of their class- and examination-related behaviors during the transition, suggest that dismissing individuals do have the capacity to acknowledge difficulties with regard to nonthreatening issues that do not place them in a vulnerable position. This is in line with the conception that dismissing indi-viduals emphasize personal strengths and prefer to focus on non-emotional issues (Main & Goldwyn, 1998).

In addition to the effect of the transition on dismissing and preoccupied students’ learning dispositions, many significant as-sociations were found between dismissing and preoccupied states of mind and dimensions of learning dispositions. Hence, compared with autonomous students, dismissing students reported lower levels of test preparation and attention in class, gave less priority to studies, and had more difficulty seeking teachers for help. Preoccupied students also reported lower levels of test preparation and attention, in addition to reporting more difficulty seeking help from their peers, compared with autonomous students. This latter finding may seem counterintuitive, given that preoccupied indi-viduals are thought to overemphasize dependency. One may spec-ulate, however, that preoccupied students do in fact seek help from their peers to a substantial degree but fail to recognize doing so because of an evaluation bias (Dozier & Lee, 1995). Alternatively, it is possible that preoccupied individuals’ dependency needs are more likely to be activated by emotional issues than academic demands. Further research contrasting self-reports and peer reports of preoccupied individuals’ help seeking in varying circumstances is needed to clarify this issue.

with lower school marks throughout the first three college semes-ters provides further support for this view and extends previous findings on attachment security and school success at earlier developmental periods (Jacobsen & Hofmann, 1997; Moss & St-Laurent, 2001; Teo et al., 1996).

The results also suggest that a dismissing state of mind leads to poor academic performance in college, notably through its nega-tive impact on students’ quality of attention during the college transition. This process is in line with previous findings showing that greater attention and participation in class partially accounted for the relation between security of attachment and achievement in childhood (Jacobsen & Hofmann, 1997). It may be that the neg-ative internal model held by dismissing students with regards to parental availability interferes with the student’s attention capabil-ities. During the college transition, such an internal model may challenge the relationship with the parents, with the consequence of lowering parental emotional support and school involvement and indirectly decreasing students’ attention toward studies. In turn, changes in quality of attention may affect school perfor-mance. Future research including parenting measures seems nec-essary to clarify the nature of the links between a dismissing state of mind and school performance.

This study presents methodological limitations that require con-sideration. Most obviously, the sole reliance on students’ reports for assessing their learning dispositions limits the external validity of the results. Furthermore, three scales of the learning dispositions measure (SHT, BE, and BWM) present indices of reliability below .70 at one of the measurement points. The internal and external validity of the results may be improved by using teacher or peer evaluations and with the inclusion of additional measures of learn-ing dispositions, especially those addresslearn-ing school beliefs. How-ever, by controlling for academic achievement in high school in predicting learning dispositions in college and by using two dif-ferent times of measurement, we were able to increase the causal inference that can be drawn from the results.

The low participants-to-variables ratio represents another limit to the present study. Sixty-two participants were involved, whereas 10 repeated outcomes and one covariate were examined in relation to the AAI. Although the repeated design yielded greater statistical power, it will be important to replicate the current findings with larger samples. In addition to increased statistical power, such studies will allow for the inclusion of parenting measures, such as parental school involvement and emotional support, and for ex-amining the impact of these variables in understanding the effects of attachment on academic and learning dispositions. The links that were observed in this study between attachment and academic outcomes may be independent from parenting variables, attribut-able to parenting variattribut-ables, or even spurious, that is, caused by parenting that fosters both secure attachment and positive learning dispositions. Exploring the mechanisms linking attachment to ac-ademic performance constitutes a complex task that requires care-ful examination of multiple potential mediating, moderating, and control variables that may intervene at the beginning of the causal chain (e.g., denying or being enmeshed with parental school in-volvement) as well as at the end (e.g., low perceived academic competence).

Assessing attachment state of mind during the first semester in college constitutes a further limitation of the present study. In a perfect design, student attachment state of mind would have been

assessed before the college transition. In the current design, it is possible that the college transition, or changes in learning dispo-sitions, influenced students’ attachment. However, many attach-ment researchers would argue that attachattach-ment state of mind is stable and not affected by normative transitions. That assumption is supported by empirical research that has shown high stability of attachment status over periods ranging from 1 month to 1 year (Benoit & Parker, 1994; Sagi et al., 1994; Steele & Steele, 1994). Research has also shown that attachment state of mind is unaf-fected by an intervention specifically targeting participants’ state of mind (Korfmacher, Adam, Ogawa, & Egeland, 1997). There-fore, it appears unlikely that the college transition would change students’ attachment state of mind.

This study has suggested that the learning dispositions of inse-cure students are more negatively affected by the college transition than those of autonomous students. It was also observed that a dismissing attachment state of mind acts as a risk factor for low academic performance during the college transition, regardless of previous levels of achievement. The results also suggest that quality of attention in class mediates the impact of a dismissing state of mind on academic performance. Given that the college transition is recognized as a critical developmental period that impacts on several spheres of adolescents’ adjustment, we believe these results highlight the importance of attachment state of mind in times of stress, especially during transition periods. Taken together, the results point to the necessity for future research to further explore the mechanisms through which the relation be-tween attachment state of mind and varying aspects of functioning in college operates.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. (1990). Some considerations regarding theory and as-sessment relevant to attachments beyond infancy. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & C. M. Cummings (Eds.),Attachment in the preschool years(pp. 1–96). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ainsworth, M. D., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978).Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation.Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bandura, A. (1986).Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory.Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51,1173–1182.

Beck, A. T. (1976).Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders.New York: International Universities Press.

Benoit, D., & Parker, K. C. H. (1994). Stability and transmission of attachment across three generations. Child Development, 65, 1444 – 1456.

Bernier, A., Larose, S., Boivin, M., & Soucy, N. (2004). Attachment state of mind: Implications for adjustment to college.Journal of Adolescent Research, 19,783– 806.

Bowlby, J. (1982).Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment(2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books.

Britton, B. K., & Tesser, A. (1991). Effects of time-management practices on college grades.Journal of Educational Psychology, 83,405– 410. Bus, A. G., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (1988). Mother– child interaction,

attachment, and emergent literacy: A cross-sectional study.Child De-velopment, 59,1262–1272.

Life-course patterns of explosive children.Developmental Psychology, 23,308 –313.

Dozier, M., & Lee, S. (1995). Discrepancies between self- and other-report of psychiatric symptomatology: Effects of dismissing attachment strat-egies.Development and Psychopathology, 7,217–226.

Dozier, M., & Tyrrell, C. (1998). The role of attachment in therapeutic relationships. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rhodes (Eds.),Attachment theory and close relationships(pp. 25– 45). New York: Guilford Press. Ekstrom, R. B., Goertz, M. E., Pollack, J. M., & Rock, D. A. (1986). Who drops out of high school and why? Findings from a national study.

Teachers College Record, 87,356 –373.

Ellis, A., & Grieger, R. (Eds.). (1978).Handbook of rational-emotional therapy.New York: Springer.

George, C., Kaplan, N., & Main, M. (1996).Adult Attachment Interview protocol(3rd ed.). Unpublished manuscript, University of California, Berkeley.

Grossmann, K. E., Grossmann, K., & Zimmermann, P. (1999). A wider view of attachment and exploration: Stability and change during the years of immaturity. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.),Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications(pp. 760 –786). New York: Guilford Press.

Hays, R. B., & Oxley, P. (1986). Social network development and func-tioning during a life transition.Journal of Personality and Social Psy-chology, 50,305–313.

Hesse, E. (1999). The Adult Attachment Interview: Historical and current perspectives. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.),Handbook of attach-ment: Theory, research, and clinical applications(pp. 395– 433). New York: Guilford Press.

Jacobsen, T., Edelstein, W., & Hofmann, V. (1994). A longitudinal study of the relation between attachment representations in childhood and cognitive functioning in childhood and adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 30,112–124.

Jacobsen, T., & Hofmann, V. (1997). Children’s attachment representa-tions: Longitudinal relations to school behavior and academic compe-tency in middle childhood and adolescence.Developmental Psychology, 33,703–710.

Kobak, R. R., Cole, H. E., Ferenz-Gillies, R., Fleming, W. S., & Gamble, W. (1993). Attachment and emotion regulation during mother–teen problem solving: A control theory analysis.Child Development, 64,

231–245.

Korfmacher, J., Adam, E., Ogawa, J., & Egeland, B. (1997). Adult attach-ment: Implications for the therapeutic process in a home visitation intervention.Applied Developmental Science, 1,43–52.

Lapsey, D. K., Rice, K. G., & Shadid, G. E. (1989). Psychological sepa-ration and adjustment to college.Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36,

286 –294.

Larose, S., & Bernier, A. (2001). Social support processes: Mediators of attachment state of mind and adjustment in late adolescence.Attachment and Human Development, 3,96 –120.

Larose, S., & Boivin, M. (1998). Attachment to parents, social support expectations, and socioemotional adjustment during the high school– college transition.Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8,1–27. Larose, S., & Roy, R. (1995). Test of Reactions and Adaptation in College

(TRAC): A new measure of learning propensity for college students.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 87,293–306.

Main, M. (1973). Exploration, play and cognitive functioning related to infant-mother attachment.Infant Behavior and Development, 6,167– 174.

Main, M. (1994).Recording and transcribing the Adult Attachment Inter-view.Unpublished manuscript, University of California, Berkeley, De-partment of Psychology.

Main, M., & Goldwyn, R. (1998).Adult attachment classification system

(Draft 6.2).Unpublished manuscript, University of California, Berkeley. Matas, L., Arend, R. A., & Sroufe, L. A. (1978). Continuity of adaptation in the second year: The relationship between quality of attachment and later competence.Child Development, 49,547–556.

Meins, E. (1997).Security of attachment and the social development of cognition.Hove, England: Psychology Press.

Moss, E., & St-Laurent, D. (2001). Attachment at school age and academic performance.Developmental Psychology, 37,107–119.

Pascarella, E., & Terenzini, P. (1991).How college affects students.San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Pianta, R., Egeland, B., & Adam, E. (1996). Adult attachment classification and self-reported psychiatric symptomatology as assessed by the Min-nesota Multiphasic Inventory—2.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64,273–281.

Rice, K. G. (1991, July).Attachment, separation–individuation, and ad-justment to college: A longitudinal study.Poster presented at the Inter-national Society for the Study of Behavioural Development, Minneap-olis, MN.

Sagi, A., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Scharf, M., Koren-Karie, N., Joels, T., & Mayseless, O. (1994). Stability and discriminant validity of the Adult Attachment Interview: A psychometric study in young Israeli adults.

Developmental Psychology, 30,771–777.

Sroufe, L. A. (1988). Relationships, self, and individual adaptation. In A. Sameroff & R. Emde (Eds.),Relationship disturbances in early child-hood(pp. 70 –94). New York: Basic Books.

Steele, H., & Steele, M. (1994). Intergenerational patterns of attachment. In K. Bartholomew & D. Perlman (Eds.),Advances in personal relation-ships: Vol. 5. Attachment processes in adulthood(pp. 93–120).London: Jessica Kingsley.

Teo, A., Carlson, E., Mathieu, P., Egeland, B., & Sroufe, L. A. (1996). A prospective longitudinal study of psychosocial predictors of achieve-ment.Journal of School Psychology, 34,285–306.

Terrill, R. (1988).L’abandon scolaire au collegial: Une analyse du profil des decrocheurs [Dropout in college: Examination of the students’ characteristics]. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Services Re´gional d’Admission Me´tropolitain.

Thompson, R. A. (1999). Early attachment and later development. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.),Handbook of attachment: Theory, re-search, and clinical applications(pp. 265–286). New York: Guilford Press.

Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (1996). Attach-ment representations in mothers, fathers, adolescents, and clinical groups: A meta-analytic search for normative data.Journal of Consult-ing and Clinical Psychology, 64,8 –21.

Weinfield, N. S., Sroufe, L. A., Egeland, B., & Carlson, E. A. (1999). The nature of individual differences in infant– caregiver attachment. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.),Handbook of attachment: Theory, re-search, and clinical applications (pp. 68 – 88). New York: Guilford Press.

Received December 10, 2003 Revision received September 28, 2004