BETWEEN INTERNATIONAL AND SOCIETAL

PRESSURES

INDONESIA’S EXPERIENCE

IN THE WAR ON TERROR,

2001

—

2009

DR. ALI MUHAMMAD

UNIVERSITAS MUHAMMADIYAH YOGYAKARTA

LP3M UMY

2012

2001

—

2009

SUMMARY

This book attempts to analyze Indonesia’s counter-terrorism policy during the period 2001—2009. It asks three interrelated questions. Firstly, according to the government’s perspective, who was responsible for the major bomb attacks in Indonesia? Secondly, what sort of counterterrorism policies did the government adopt? Finally, what are the

main factors that shaped the government’s counterterrorism policy during that period?

To explain the Indonesian government’s counterterrorism policy, this study adopts “the logic of two-level games” (Putnam, 1988) as the theoretical framework. The model explains how domestic politics and international relations get entangled and influence

the direction taken by the government’s policy. Based on the theoretical framework, government policy is a function of incentives and constraints both on the international

and on the domestic level. As “the gatekeeper” between the two levels game, the

government simultaneously processes these interdependent incentives and constraints in its policy decision-making.

This book uses a qualitative research method. The data used in this research are mostly derived from official documents, direct interviews with government officials and the secondary sources (books and journals) on terrorism and counterterrorism. This book demonstrates that, although it never banned Al-Jamaah Al-Islamiyah (AJAI) because of domestic considerations, the government believes that the AJAI is a terrorist network mostly responsible for the consecutive bombings in Indonesia.

Secondly, the present government has mostly relied on a “law-enforcement approach” in fighting the terrorist network which has been incrementally complemented with an

“ideological approach” to fight religious extremism. Finally, the pathway of

Indonesia’s counterterrorism policy was shaped by contradictory pressures originating

DR ALI MUHAMMAD is lecturer in International Relations at Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta. After completed his Bachelor’s degree in the Department of International Relations at Gadjah Mada University, he obtained his Master’s degree from Graduate Studies in International Affairs, the Australian National University, and his PhD in Political Science from International Islamic University Malaysia. During completing his PhD, he received Student Research Fellow at Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore (2008) and Leiden University, the Netherlands (2010)

This book is dedicated to:

Mrs. Hj. Subinah

Mrs. Hj. Suhaebah & Mr. H. Karnawan

And in memory of my father

Mr. Slamet Abdullah

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur. At the very outset, I would like to extend my profound gratitude to Prof. Dr. El-Fatih A. Abdelsalam, my supervisor, for his tireless and generous advice and guidance during the very initial stages of this book. He is very kind to go through and read the initial draft of this work. Needless to say, for any errors and shortcomings I hold myself fully responsible. I am also grateful to my

Gurus: Prof. Dr Abdul Rashid Moten, Assoc. Prof Dr. Wahabuddin Ra’ees, Assoc.

Prof Dr Ishtiaq Hossain, and Dr Tunku Mohar Tunku Mohtar as well as all my colleagues at the Department of International Relations, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta.

During my research, the Asia Research Institute, the National University of Singapore (NUS), generously granted me scholarship to undertake three months library research at the NUS library and the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS). Leiden University also generously granted me four months fellowship under

the scheme of “Training Indonesia’s Young Leader Program” to carry out intensive

library research at Utrecht University, Leiden University, and KITLV, the Netherlands. The Research Centre of IIUM also kindly provided me research grant. Indonesian government also kindly gave me DIKTI scholarship to support my final year of study. More importantly, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta gave me generous financial support. Therefore, I am deeply thankful to all those institutions.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abstract. ………..………...i

Dedication ……….... ……....x

Acknowledgments ………….……….…...…………...x

Table of Contents... ………….………...……...……... x

List of Tables and Figures………... ...x

List of Abbreviations ……….………...x

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION... .x

Security Problem:... ...x

“Terrorism” Defined…...x

Counterterrorism Policy... x

The State and the Logic of Two-Level Games...x

The State: Between Societal and International Pressures...x

Previous Studies...x

Organization of this book... x

CHAPTER 2: GOVERNMENT’S PERCEPTION OF TERRORISM... xx

Introduction………... xx

Origins of Al-Jamaah Al-Islamiyah……….. xx

Exile and Jihadin Afghanistan ………. xx

Organization and Network………... xx

Guidelines for Struggle ………...……….. xx

The Rise of the Terrorist Faction ……….……... xx

Bombing Operations……….……….………

Ideological Motives ………...……... xx

Establishing Daulah IslamiyahNusantara………... xx

Muslim Solidarity and (Mis) Interpretation of Jihad………...xx

Conclusion………. xx

CHAPTER 3: GOVERNMENT’S COUNTERTERRORISM POLICY... xx

Introduction……….….…. ……... xx

Evolution of Counterterrorism Policy……….………... xx

History: Failure of Militaristic Approach……….…... xx

Response: Before and After Bali Bombing 2002………….………….. xx

Political Context: the Governments……….…….. xx

Megawati Administration (2001—2005)……..……….….... xx

Yudhoyono Administration I (2005—2009)….………...…...xx

Guidelines: National Strategy for Counterterrorism ……….……... xx

Counterterrorism: Law Enforcement Approach………..……... xx

“Physical Battle” against Terrorist Network………... xx

Counterterrorist Law…………...……….... xx

Counterterrorism Agencies………... xx

Principal Agency: Indonesia National Police... xx

Special Detachment 88... xx

Intelligence Agencies……….……... xx

Supporting Agency: Armed Forces...………. …….……...… xxx

Counterterrorism Coordinating Desk…….………...xxx

Anti-Terrorism: An “Ideological” Approach………...…...… xxx

“An Ideational Battle” against Religious Extremism………….…….. xxx

Government’s Commitment………... xxx

Neutralising Extremism: Police and De-radicalization Programme.... xxx

Containing Extremism: Indonesian Ulama Council………….…….... xxx

Containing Extremism: Partnership with Muslim Community…….... xxx

Department of Religious Affairs: Hesitant Role.. ……….……... xxx

Conclusion……….………..……… xxx

CHAPTER 4: DEMOCRACY, SOCIETAL PRESSURES AND COUNTERTERRORISM POLICY... xxx

Domestic Context: The Rise of Democracy………....

xxx

Restoration of Democracy……….…………... xxx

The State, Society and Government Policy………... xxx

Societal Pressures: Muslim Community……….. xxx

Democracy and “Islamic Revivalism”………... xxx

Re-emergence of Islamic Political Parties……… xxx Islamic Revivalist Groups……….... xxx

Common Views: Scepticism on Terrorism Issue………... xxx

Global War on Terror: “War on Islam”….….………... xxx

Terrorism: Foreign Conspiracies…………..………... xxx

Societal Pressures: Human Rights Groups……….. xxx

Democracy and Human Rights Groups……….... xxx

Apprehension on Anti-Terrorism Law……….………… xxx

Critiques on Implementation……….... xxx

Implications for Counterterrorism Policy……….... xxx

Hesitancy to deal with Abubakar Ba’asyir………... xxx

Failure to Outlaw the AJAI………...……..…. xxx

Indecision to Expand an “Ideological” Approach……….... xxx

Failure to Adopt Tougher Anti-Terrorism Law………... xxx

Conclusion………... xxx

CHAPTER 5: GLOBAL “WAR ON TERROR,” INTERNATIONAL PRESSURES AND COUNTERTERORRISM POLICY... xxx

Introduction………. xxx

International Context: Bush’s War on Terror………... xxx

“Global War on Terror” and the US Strategy…………... xxx

Southeast Asia as “the Second Front”……….……….... xxx

Jamaah IslamiyahUncovered and Pressures on Indonesia…... xxx

International Pressures: Demands……… xxx

The Adoption of Legal Framework: Anti-Terrorism Law………….. xxx

The Arrest of the “Spiritual Leader” ofthe AJAI ……… xxx

Proscription of the AJAI ……….………... xxx

INTENSIVE DIPLOMATIC CHANNELS………... XXX

Anti-Terrorism Assistance……… xxx

ECONOMIC INDUCEMENTS………..………... XXX Pledge to reduce Military Embargo……….. xxx

Implications for Counterterrorism Policy……… xxx

Increasing Government’s Determination………... xxx

Bolstering Government’s Capability ………... xxx

Conclusion………..………..…………... xxx

CHAPTER 6: CONCLUSION... xxx

Issues Analyzed and Findings………... xxx

Limitations of the Study... xxx

Lessons: Indonesia’s Experiences...……….……. xxx

APPENDIX I. NOTES ON METHODOLOGY...xxx

APPENDIX II: GRL N0. 1/2002 ON COMBATING CRIMINAL ACTS OF TERRORISM...xxx

APPENDIX III: GRL NO. 2/2002 ON THE ENACTMENT OF GRL NO. 1/2002... . xxx

APPENDIX IV: EXPLANATION OF GRL NO. 2/2002... xxx

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

Tables No. Page No. Table 1.1: Major Terror Attacks, 2000 –2009……… …………...x Table 3.1: Hotel Marriott Bombers and their Education……… xxx

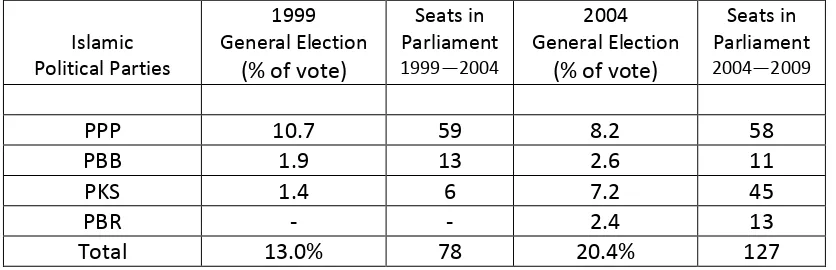

Table 3.2: The Australian Embassy Bombers and their Education…….……….... xxx Table 4.1: Performance of Islamic Political Parties in the 1999 and 2004

General Elections……….……….. xxx

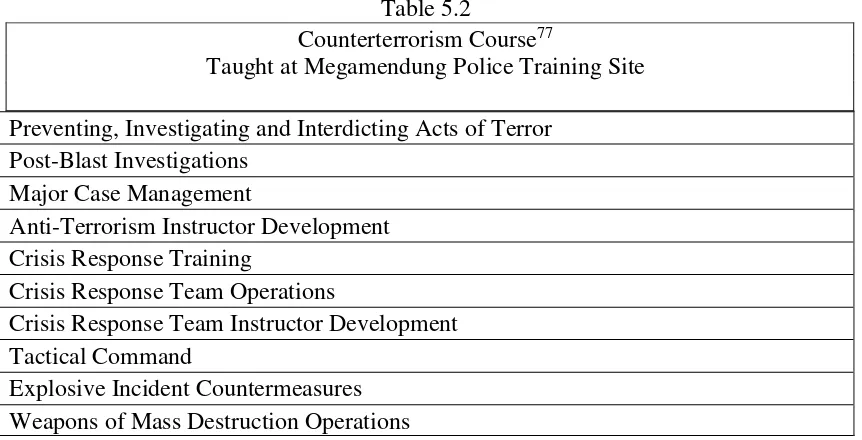

Table 5.1: Anti-Terrorism Assistance Program Funding for Indonesia…………. xxx Table 5.2: Counterterrorism Course Taught at Megamendung

Police Training Site………... xxx

Figures No.

Figure 2.1: Structure of the AJAI according to Indonesian Police……….... xxx

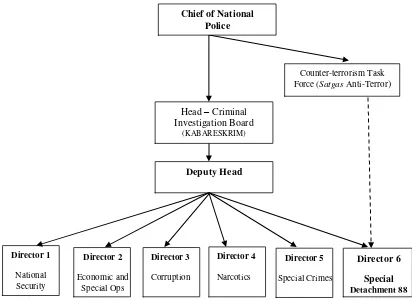

Figure 3.1: Indonesia’s Counter-terrorism Structure....………. xxx

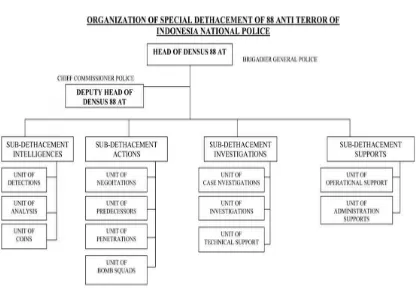

Figure 3.2: Organization of Detachment 88, Indonesian National Police... xxx

Figure 3.3: Counterterrorism Coordinating Desk………...xxx

BIN : Badan Intelejen Negara (State Intelligence Agency) CTCD : Counterterrorism Coordinating Desk

DENSUS 88 : Detasemen Khusus 88 (Special anti-terror police unit) DEPAG : Departemen Agama (Department of Religious Affairs) DI/NII : Darul Islam/Negara Islam Indonesia

DPR : Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat (Indonesian Parliament) FPI : Front Pembela Islam (Islamic Defender Front) GRL : Government Regulation in Lieu of Law GWOT : Global War on Terror

HTI : Hisbut Tahrir Indonesia ICG : International Crisis Group ISA : Internal Security Acts

KONTRAS :Komisi untuk Orang Hilang dan Korban Kekerasan (The Commission for Disappearances and Victims of Violence). MMI : Majelis Mujahiddin Indonesia (Indonesian Warrior Council) MUI : Majelis Ulama Indonesia (Indonesian Ulama Council) NU : Nahdhatul Ulama

PBB : Partai Bulan Bintang (the Moon and Star Party)

PKS : Partai Keadilan Sejahtera (the Prosperous Justice Party)

PERPU : Peraturan Pemerintah Pengganti Undang Undang (Government Regulation in Lieu of Law, GRL)

POLRI : Polisi Republik Indonesia (Indonesian National Police, INP) PPATK : Pusat Pelaporan dan Analisis Transaksi Keuangan (Financial

Transaction and Report Analysis Centre)

PPP : Partai Persatuan Pembangunan (the United Development Party) RUU : Rancangan Undang-Undang (Law proposal, Bill)

1

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

Security Problems

After the downfall of “New Order” regime in 1998, the repressive capacities of the state weakened significantly. The world’s biggest Muslim country slowly moved towards a consolidated democratic regime.1 During the critical phase, however, a

variety of internal security problems in the peripheral regions emerged such as, the increasing separatist movements in East Timor, Aceh, and West Papua2 as well as the

protracted communal conflict in West Kalimantan, Ambon and Poso.3 However, the new democratic governments also had to respond to terrorist threats which had adversely affected the national stability and security since 2000.4

On Christmas Eve, 24 December 2000, a clandestine network launched coordinated bombing attacks against churches in eleven cities across Indonesia.5 The

coordinated bomb attack used low-explosive materials and killed 9 and wounded 120 people. With a few exceptions, such as the attack on the residence of the Philippine

1 “New Oder” is an authoritarian, military dominated regime during Suharto’s rule, 1966—1998. 2 East Timor ceded from Indonesia after a Referendum in 1999. The Aceh problem was solved after the agreement between the government and the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) had been signed in Helsinki. The government agrees to give Aceh province a special autonomy status and GAM agrees to stop their armed struggle and aspiration for independence. However, the problem of separatism in West Papua has yet to be solved up to the present time. See, Andrew T.H. Tan, Security Perspective of the Malay Archipelago: Security Linkages in the Second Front in the War on Terrorism, (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, 2004), 175-90.

3 An excellent analysis on communal violence in the outer islands since the downfall of the New Order, see Gerry Van Klinken, Communal Violence and Democratization in Indonesia: Small Town Wars, (London and New York: Routledge, 2007).

4 Analysis on instability faced by Indonesia since the downfall of Suharto, see, Bilveer Singh, Indonesia and the Arch of Instability,” in Australia’s Arc of Instability: The Political and Cultural Dynamics of Regional Security, edited by D. Rumley, Vivian. L. Forbes and C. Griffin, (The Netherlands: Springer, 2006), 83-100.

2

ambassador in Jakarta in August 2000, the targets were mostly churches and priests. A report states that the motivation for the church bombing was revenge for massacres of Muslims by Christians in the conflict areas: Maluku, North Maluku, and Poso (Central Sulawesi) in 1999 and 2000.6

Since then, deadly bombings have become regular in Indonesia: the Bali Bombings killed mostly foreign tourists on October 12th 2002; the J.W. Marriot Hotel was bombed on 5 August 2003; there was a suicide bomb attack at the Australian Embassy on 9 September 2004, and suicide bombings in Bali on 1 October 2005. On July 17th, 2009, after Indonesia successfully has held a peaceful parliamentary and presidential election, two suicide bombers suddenly attacked the J.W. Marriott and Ritz-Carlton hotels, Jakarta. The consecutive terror attacks have damaged political stability, national security and the fragile economy of the world’s biggest Muslim nation on earth. Table 1 lists the major bomb attacks since 2000.

3 Table 1.1

Major Terror Attacks, 2000 – 20097

DATE MAIN TARGET VICTIMS METHODS

30/Dec/2000 Churches, priests, the residence of

12/Oct/2002 Foreign Tourists at Paddy’s Bar and Sari’s Club and the US Consulate (Bali)

202 dead, 300 wounded

Car Bombs

05/Aug/2003 Foreigners in the J.W. Marriott Hotel (Jakarta)

17/Jul/2009 Foreigners at the J.W. Marriott & Ritz Carlton Hotels (Jakarta)

9 dead, 53 wounded

Suicide Bomb

Base on the elaboration, it is obvious that terrorism was a serious security threat to this world’s biggest Muslim majority country. The big question in this book is: how the Indonesian government respond to the security problem? In particular, it asks several questions: Firstly, according to the Indonesian government’s perspective, who

was responsible for the consecutive major bomb attacks in Indonesia? What was their motivation? Secondly, what sort of counterterrorism policies did the government take during the 2001—2009 period? Finally, what were the main determinants that shaped

the direction of the government’s counterterrorism policy during that period?

“Terrorism” Defined

The word “terrorism” is derived from the Latin word terrere, meaning to frighten, to terrify, to scare away, or to deter. “Terrorism” has no precise or widely accepted

7

4

definition and is one of the most controversial concepts in social sciences.8 To define

it is intricate because the meaning has changed so frequently within social and historical contexts over the past two hundred years.9 The definition of the term

depends on political power, that is to say, government can increase their power when

they label opponents as “terrorists.”10 From a critical perspective, the way the term is

selectively applied is only to serve the interests of the powerful.”11 Furthermore, to define it is very complicated since a well-known adage says, “one person’s terrorist is

another person’s freedom fighter.”12

It is noteworthy that most of the definitions agree that acts of terrorism are

“immoral and abhorred.” However, the controversies have emerged on this point since

the definers seek to exclude groups that they wish to support or to include groups that they wish to denounce. Central to the disagreement is the categorization of whether

political violence is “lawful” and “legitimate” or “unlawful” and “illegitimate.”13

Some define terrorism if the perpetrator is only a sub-national group, but others define it more broadly to include state actors as well. For instance, the US Department of

Defense defines terrorism as “the unlawful or threatened use of force or violence against individuals or property to coerce and intimidate governments or societies,

8 Charles W. Kegley, Jr. The New Global Terrorism: Characteristics, Causes, Controls, (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2003), 16.

9 David J. Whittaker, The Terrorism Reader, (London and Now York: Routledge, 2001), 5.

10 Jonathan R. White, Terrorism: An Introduction, 3rd Edition, (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Thomson Learning, 2002). 6. See also, Walter Laqueur. Terrorism, (Boston: Little Brown and Co, 1977). 11 From critical perspective, see for instance, Edward Said, ‘The essential terrorist’, in Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question, edited by Edward Said and Christopher Hitchens (London: Verso, 2001), 147–57.

12 James M. Lutz and Brenda J. Lutz, Global Terrorism, (London and New York: Routledge, 2004), 8. In Israeli-Palestinian conflict, for instance, Israeli government and the Western governments label

HAMAS as “a terrorist organisation.” On the contrary, Palestinian resistance groups who live under the Israelis’ brutal occupation and the sympathisers of the Palestinian cause categorize the Israeli

government as “the real terrorist.”

5

often to achieve political, religious or ideological objectives.”14 Meanwhile, the

US State Department defines terrorism as “premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against noncombatant targets by sub-national groups or

clandestine agents, usually intended to influence an audience.”15 By using the US

State Department’s definition, political violence can be categorized as acts of

terrorism if they are “unlawful” or perpetrated by “sub-national groups.”16

In contrast, Ayatullah Syaikh Muhammad Ali Tashkiri formulated a broader definition at the international conference on terrorism called by the Organization of

the Islamic Conference (OIC) in Geneva in June 1987. He said that ”Terrorism is an

act carried out to achieve an inhuman and corrupt objective, and involving threat to security of any kind, and violation of rights acknowledged by religion and

mankind.”17 Using his definition, Tashkiri intended to include “state terrorism,” in

particular, the United States being “the mother of international terrorism.” Tashkiri

writes:

It is indeed comical that the United States of America, which is the mother of international terrorism, and the author of all the circumstances of oppression and subjection of people, by strengthening dictatorial regimes and supporting occupation of territories and savage attacks on civilian areas, etc. should seek to convene symposia on

14 Gus Martin, Essentials of Terrorism: Concepts and Controversies, (Los Angeles: Sage Publication, 2008), 8.

15 Ibid, 9.

16 This definition creates controversies because the attacks of the Israeli army against Palestinian civilians in the occupied territories and the US invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq cannot be categorized

as “terrorism” because it is “lawful” and “legitimate” since it is perpetrated by the state.

17 Ayatullah S.M.A.Tashkiri, “Toward a definition of terrorism,” Al-Tauhid, vol. V, no. 1 (Muharram 1408 AH/1987CE), <http//www.al-islam.org/al-tawhid/definition-terrorism.html> (accessed on 26

October, 2009). Other Muslim intellectuals have also tried to define terrorism broadly: “An outrageous

attack carried out either by individuals, groups or states against the human being (his religion, life, intellect, property and honour). It includes all forms of intimidation, harm, threatening, killing without just cause and everything connected with any form of armed robbery, hence making pathways insecure, banditry, every act of violence or threatening intended to fulfil a criminal scheme individually or collectively, so as to terrify and horrify people by hurting them or by exposing their lives, liberty, security or conditions to danger; it can also take the form of inflicting damage on the environment or on

6

combating ‘terrorism, i.e., any act that conflicts with its imperialist interests…18

It seems obvious that there is an incompatible perspective on terrorism between

“the West” and “the Muslim world.” However, controversies have also emerged within the Muslim world itself. For instance, the Muslim world represented

“formally” by the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) also failed

excruciatingly to formulate an agreed definition of terrorism. In the extraordinary session of the Islamic Conference of foreign ministers on terrorism in Kuala Lumpur in April 2002, OIC foreign ministers were divided over whether or not Palestinian

suicide bombers can be categorized as “terrorists.”19

Another prominent scholar who studied terrorism is Alex P. Schmidt. He has

also examined 109 definitions of “terrorism” from leading academic researchers from

the field. From these definitions, he identifies the following definition elements: violence and force—appeared in 83.5% of the definitions; political goal—65%; spreading fear and dread—51%; threat of violence—47%; psychological impact of terrorism—41%; discrepancy between target and victims—37.5%; degree of consistency, planning, and organization of terrorism—32%; terrorism as a method of warfare, strategy and tactics—30.5%.20

Apart from those controversies and variety of meanings, however, a clear definition of the term is required not only for academic purposes but also for practical purposes. To fight against a terrorist group, for instance, we must first of all be very

clear whether the organization we are fighting against is “a terrorist group.” Boaz

18 Ibid.

19“OIC Leaves It to UN to Define “Terrorism,” Asian Political News, 8 April 2002. <http://findarticles. com/p/articles/mi_m0WDQ/is_2002_April_8/ai_84640350> (accessed on 27 January, 2009).

7

Ganor‘s definition of terrorism is useful here. He proposed a simple definition of

terrorism as follows, “terrorism is a form of violent struggle in which violence is

deliberately used against civilians in order to achieve political goals.”21 The definition

is based on three central elements: First, the essence of the action—the form of violent struggle.22 According to this definition, any action which does not involve violence is

not defined as terrorism.

Second, the goal underlying terrorism, which is always political, that is a goal aimed at achieving something in the political arena: overthrowing a regime, changing the form of governance, replacing those in power, revising economic, social and other policies, dominating and disseminating ideologies. With no political agenda, the action in question is not considered as terrorism.23 Violent action against civilians without a political goal is, at most, a purely criminal act, a felony, or simply an act of insanity that has nothing to do with terrorism.

Third, the target of the damage is civilians.24 In this way, “terrorism” can be distinguished from other forms of political violence, such as guerrilla warfare, popular insurrection, and so on. From the definition of terrorism elucidated above, it is obvious that the consecutive bombing attacks against civilians mentioned above can be categorized as acts of terrorism. Using the simple definition elaborated above, we can argue that the Bali Bombing and other consecutive bombings in Indonesia can be categorized as acts of terrorism.

21 Boaz Ganor, The Counter-Terrorism Puzzle: Guide for Decision Makers, (New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publisher, 2005), 17.

8

The Indonesian government has also formulated its own definition of

“terrorism.” According to Law No. 15/2003 (Indonesia’s Anti-Terrorism Laws), the

basic definition of the criminal act of “terrorism” is,

Any person who intentionally uses violence or the threat of violence to create a widespread atmosphere of terror or fear in the general population or to create mass casualties, by forcibly taking the freedom, life or property of others or causing damage or destruction to vital strategic installations or the environment or public facilities or international facilities.25

Counterterrorism Policy

Before elucidating the concept of “counterterrorism policy” it is crucial first to define

the concept of “policy” in the first place. “Policy” can be defined as a “set of

interrelated decisions concerning the selection of goals and the means of achieving them within a specified situation.”26 Policy may also be considered as a course of

[government’s] action or inaction rather than specific decisions or actions.27 Smith suggests that the concept of policy denotes a “deliberate choice of action or inaction,

rather than the effects of interrelating forces.”28 It should be emphasized here that

inaction as well as action and attention should not focus exclusively on decisions which produce change, but must also be sensitive to those which resist change.

More specifically, “public policy” can be defined as “anything a government

chooses to do or not to do.”29 This simple definition is not without merit. Firstly, it

means that the agent of public policy-making is a government. When we talk about public policies, we speak of the actions of government. Secondly, public policy

25 Law No. 15/2003, Section 6 [basic definition of criminal act of terrorism] 26 Jenkin W. I. Policy Analysis, (London: Martison Roberson, 1978), 17

27 Heclo, H, “Review Articles: Policy Analysis,” British Journal of Political Science, 2. (1972): 85 28 Smith, Policy Making in British Government, (London: Martin Roberson, 1978), 13

9

involves a fundamental choice on the part of governments to do something or to do nothing and the decision is made by individuals staffing the state and its agency. Public policy is a choice made by a government to undertake some course of action.30 The government’s policy to fight terrorism is definitely part of “public policy.”

Gus Martin refers to “counterterrorism policy” as “proactive [government’s] policies that specifically seek to eliminate terrorist environments and groups.”31

Because “terrorism occurs when opportunity, motivation, and capability meet,”32 a

multi-pronged counterterrorism policy approach is required not only to destroy terrorist networks, infrastructure and operational capability but also to curb, suppress, and refute their ideological motivation. Regardless of which policy is selected, the ultimate goal of counterterrorism policy is to save lives by proactively preventing or decreasing the number of terrorist attacks.33

Boaz Ganor points out a number of specific goals that might underlie a nation’s counterterrorism policy. Firstly, eliminating terrorism is likely to be expressed as eradicating the enemy (destroying the terrorist organization itself), removing the

enemy’s incentive to commit terrorist attacks and use violence against the state and its citizens, or resolving the controversial issues (since the motive behind terrorism is a political one, the solution is also to be found in the political sphere). Secondly, minimizing the damage caused by terrorism may include sub-goals such as reducing the number of attacks and/or the number of victims, preventing certain type of attacks (suicide bombing, mass killing, etc) lessening property damage etc. Thirdly,

30 Ibid.

31 Gus Martin, Understanding Terrorism: Challenge, Perspective, and Issues, (Thousand Oaks: Saga Publication, 2003), 345.

32 Muhammad H. Hasan, “Countering-Ideological Work: Singapore Experience” in The Ideological War on Terrorism: Worldwide Strategies for Counter-Terrorism,” edited by Anne Aldis and Graeme P. Herd (London: Routledge, 2007), 143.

10

preventing the escalation of terrorism is based on two sub-goals: (1) ensuring that the conflict does not spread—stopping the terrorist organization’s growth and development through enlistment of new activists to its ranks, preventing the organization from gaining political ground in the international arena, blocking or neutralizing support from their country, impeding the intensification of the

organizations’ political objectives and effort (2) making certain the scope of attacks

does not escalate.34

Art and Richardson also demonstrate that government can use a range of counterterrorism policies to combat groups resorting to terror. These measures can be grouped into three categories: political measures, legislative and judicial measures, and security measures.35 Firstly, political measures include negotiations with groups (in which the government makes compromises and concessions) to bring about the end of resistance; socio-economic and political reforms to win the “hearts and minds” of the people from whom the terrorists draw both armed adherents and more general support; and international cooperation to cut off funds to terrorists, extradite terrorists, police borders, and provide intelligence to the state under siege.36

Secondly, legislative and judicial measures include emergency and other special legislation to expand the government’s powers to arrest, detain, and incarcerate suspects and to gain intelligence about them in ways that involve

infringements on citizen’s privacy; use of the courts to empower the state and special

magistrates and prosecutors to undertake broad investigative actions; legislation to disrupt the finances of groups employing terrorism; and amnesty and repentance measures designed to wean active armed members away from such groups and to

34 Ganor, 25-6.

35 Robert J. Art and Louise Richardson, Democracy and Counterterrorism: Lesson from the Past, (New York: US Institute of Peace Press, 2007), 17.

11

reintegrate them into society.37 Finally, security measures could include military

deployment to protect the population and to seek out and destroy terrorist groups; intelligence operations, especially the use of counterterrorist units to penetrate terrorist networks and disrupt their logistics and support networks; new organizational machinery to coordinate the security instruments and disparate units of governments dealing with terrorism; and preventive actions for defence, such as, the hardening of facilities, control of access, and the like. Of course, not all governments employ every one of the above measures, and each government has its own particular way of utilizing the measures depending on the nature of the threat as well as the political context.38

This study will classify Indonesia’s counterterrorism policy into two main approaches. The first is a legal or “law-enforcement” approach. The objective of this approach is to promote the rule of law and regular legal proceedings. It can be conducted by the creation of counterterrorist laws which criminalize terrorist behaviour. This approach includes the use of law-enforcement agencies, such as empowering the police, the intelligence as well as criminal investigative techniques in the prosecution of suspected terrorists. Thesecond is an “ideological” approach based

on the belief that terrorism is the product of an “evil ideology.” Fighting terrorism,

therefore, should include the fight against the extremist ideologies which are conducive to terrorism. In broad terms, this sort of approach involves government policy to curb, refute, neutralize, or suppress the ideological factor which is supposed to be implicated in terrorist acts. Failure to neutralize the ideological motivation would mean that terrorist networks could suffer losses at the hands of security forces, but still

37 Ibid.

12

replenish their ranks with ideologically committed fresh recruits from the wider constituency.39

Because the ultimate goal of counterterrorism policy is to save lives by proactively preventing or decreasing the number of terrorist attacks,40 the effectiveness of the policy can be observed from the two main criteria: first, the reduction or disappearance of terror attacks. The significant decrease or disappearance of terror

attacks means that the government’s counterterrorism policy is effective. Second, the

neutralization or suppression of “violent ideology,” i.e. to what extent the spread of

“violent ideology” into the wider community has been prevented and stopped by the

government.

The State and the Logic of Two-Level Games

The state is a key agency that adopts and implements counterterrorism policy. Dietrich Reuschemeyer and Peter B. Evans define “the state” in its Weberian conception as “a set of organizations invested with the authority to make binding decisions for the people and organization juridically located in a particular territory and implement these

decisions using, if necessary, force.”41 Max Weber writes that,

A compulsory political organization with continuous operations will be called a state insofar as its administrative staff successfully uphold the claim to the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical forces in the

enforcement of its order…[The modern state] possesses an

administrative and legal order subject to change by legislation, to which the organized activities of the administrative staff, which are also controlled by regulations, are oriented. This system of order claims binding authority, not only over members of the state, the citizens, most of whom have obtained membership by birth, but also to a very large extent over all action taking place in the area of its jurisdiction. It is

39 Kumar Ramakrishna, “It’s the Story, Stupid: Neutralizing Radical Islamism in the Southeast Asia

Theatre” in Anne Aldis and Graeme P. Herd, (eds.), 128.

40 Martin, 346.

13

thus a compulsory organization with a territorial basis. Furthermore, today, the use of force is regarded as legitimate only so far as it is either permitted by the state or prescribed by it…The claim of the modern state to monopolize the use of force is as essential to it as its character of compulsory jurisdiction and continuous operations.42

Using the Weberian conception, Hall and Ikkenberry underline that a substantial agreement exists among social scientists on how “the state” should be defined. They stress three elements: first, the state is a set of institutions, the most important of which is that of the means of violence and coercion; secondly, these institutions lie at the centre of a geographically bounded territory usually referred to as a society; thirdly, the state monopolizes rule making within its territory.43

What does ‘government’ refer to? A broad definition of ‘government’ includes

all public institutions which make or implement political decisions and that can be spread over several tiers, being called the federal, state, and local government. The general understanding of government includes the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Most commonly, however, the “government” refers to a country’s central political executive.44 Although the “government” is only part of “the state,” it is the

political executive of the nation which speaks on behalf of the state, which is vested with its power, and which has to take ultimate responsibility for its actions. The terms

‘state’ and ‘government’ will be used interchangeably in this study.45

How are international politics, domestic politics and government policy interconnected theoretically? A prominent scholar in international relations writes aptly, “in a rapidly changing, interdependent world the separation of national and

international affairs is problematic…” and, “…domestic and foreign affairs have

42 Max Weber, Economy and Society, vol. I. (New York: Bedminster, 1978), 54-6.

43 John Hall and John G. Ikkenberry, The State, (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1989), 1-2. 44 Wolfgang C. Mueller, ”Government and Bureaucracies,” in Comparative Politics edited by Daniel Caramani (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 190.

14

always formed a seamless web.”46 Analytically, it can be shown that hard and fast

boundaries cannot be drawn between domestic policy and foreign policy, “between what happens at the national level and what happens at the global level.”47 In this interdependent world, however, it does not mean that “the state” will be nudged aside

as authority shifts in diverse directions. Instead, the state remains a key agency and plays a strategic role in domestic as well as in international affairs.

Having a ‘Janus-face,’ the state is both a domestic and international actor.48 Metaphorically, one might think of the state as a bidirectional valve, responding to whichever pressure is greater, sometimes releasing pressure from the domestic into the international, at other times releasing it from the international into the domestic.49 Another scholar also suggests that the state is “the (shifting) accommodation between

these counter-pressures”50 and other scholars call the phenomenon “intermestic” politics.51

“The logic of two-level games” developed by Robert D. Putnam provides a useful theoretical perspective to explain how domestic politics and international relations get entangled.52The “two-level games” perspective suggests that government policy is a function of incentives and constraints both at the international and the domestic level. As gatekeepers between the two levels, governments simultaneously

46 To probe the domestic as an aspect of ‘comparative politics’ and examine the foreign as a dimension

of ‘international politics’ is more than arbitrary: it is downright erroneous. See, James N. Rosenau,

Along the Domestic-Foreign Frontier: Exploration of Governance in a Turbulent World, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 4.

47 James N. Rosenau, Linkage Politics, (New York: Free Press, 1969).

48 John M. Hobson, The Wealth of States: A Comparative Study in International Economic and Political Change, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 11.

49John Ikenberry, “The State and Strategy of International Adjustment,” World Politics. 39, 1 (1986): 76.

50 Ian Clark, Globalization and International Relations Theory, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 66.

51 Those issues confronting a state that are simultaneously international and domestic, Charles W. Kegley and Eugene R. Wittkopf, World Politics: Trend and Transformation. 9th Edition (Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2004), 64.

15

process these interdependent incentives and constraints in their policy decision-making. They balance between potentially conflicting international and domestic pressures and attempt to formulate and implement policies that satisfy both. At the international level, governmental policies are shaped by the dynamics of international political events and developments as well as by the preferences, power, and negotiating strategies of other governments. At the domestic level, the governmental room for manoeuvre is constrained by the preferences and political resources of those actors on which a government depends for political support. Domestic groups pursue their interests by pressuring the government to adopt favourable policies and politicians seek power by constructing coalitions among those groups.53

Moves that are rational on one board may not be so on the other; but a leader must negotiate a consistent policy on both boards. Failure on the international board may lead a player to topple it; and failure on the domestic board may result in the leader being toppled. Putnam shows that the politics of many international negotiations is as follows,

At the national level, domestic groups pursue their interests by pressuring the government to adopt favourable policies, and politicians seek power by constructing coalitions among those groups. At the international level, national governments seek to maximize their own ability to satisfy domestic pressures, while minimizing the adverse consequences of foreign developments. Neither of the two games can be ignored by central decision-makers, so long as their countries remain interdependent, yet sovereign.54

Putnam also writes,

Each national political leader appears at both game boards. Across the international table sit his foreign counterparts, and at his elbows sit diplomats and other international advisors. Around the domestic table behind him sit party and parliamentary figures, spokespersons for domestic agencies, representatives of key interest groups, and the leader's own political advisors. The unusual complexity of this

16

level game is that moves that are rational for a player at one board (such as raising energy prices, conceding territory, or limiting auto imports) may be impolitic for that same player at the other board. Nevertheless, there are powerful incentives for consistency between the two games. Players (and kibitzers) will tolerate some differences in rhetoric between the two games, but in the end either energy prices rise or they don't.55

From the elaboration above it can be seen that politics at the domestic and international levels are fundamentally interdependent, and to explain the policies of states in the international arena one must pay serious attention to domestic and international forces.

Although the ‘two-level games’ perspective aims at explaining the state’s foreign policy in international affairs and negotiation , it will be adopted here in the Indonesian context to explain the government’s internal security policy. To adopt the counter-terrorism policy in domestic affairs, as it will be argued later, the government

has to face a similar “two-level games’ logic, i.e. it faces the pressures from the international environment and, simultaneously, it has to be sensitive to the domestic constraints from the most vocal groups within society.

The State: Between Societal and International Pressures

Societal Pressures are the first determinant that shapes the pathway of the

government’s counterterrorism policy. The adoption and implementation of the

government’s counterterrorism policy is not located within a political vacuum. Instead,

it has to face various societal forces in the domestic environment that attempt to

influence the government’s formulation of public policy. To explain the course of

government policy, it is necessary to explicate theoretically the state-society relations.

This study will adopt the “State–in–Society” model developed by Joel S. Migdal in

17

State Power and Social Forces. Rejecting the theory of a state-centred society and a society-centred state, Migdal posits that states are part of societies, meaning that states may help to mould, but they are also continually moulded by, the societies within which they are embedded. Societies affect states as much as, or possibly more than, states affect societies.56

Migdal continues to argue that states vary in their effectiveness based on their ties to society. As the state organization come into contact with various social groups, it clashes with and accommodates different moral orders. These engagements, which occur at numerous junctures, change the social bases and the aims of the state. The state is not a fixed ideological entity. Rather, it embodies an ongoing dynamic, a changing set of goals, as it engages other social groups. This sort of engagement can come through direct contact with formal representatives, often legislators, or, more commonly, through political parties closely allied with the state. Social forces, like states, are contingent on specific empirical conditions.57

It is crucial to note that the regime has changed from authoritarianism to democracy after the collapse of Suharto in 1998. In a democratic regime, the state is influenced by multiple forms of citizen participation within the limits of a consensus on the boundaries of state action. Individuals in a democratic polity have diverse ways of expressing their preferences and values. There are three major mechanisms of societal influence on the government: public opinion, voting in elections, and protests or demonstrations—where the institutionalized mechanism is unresponsive. Public opinion and voting are explicitly two major modes of societal influence on the democratic government. Social movements, interests groups, and political parties

56 Joel. S. Migdal, and et al. State Power and Social Forces: Domination and Transformation in the Third World, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 2.

18

aggregate individual preferences and values into collective political demands, which are presented to agencies of the government. A party system is a key mediating institution between state and society.58 Any government would avoid the electoral cost

of ignoring the domestic voices stemming from societal groups within the domestic politics.

After the downfall of the New Order of president Suharto and the establishment of a democratic regime, two societal and political forces are relevant to counterterrorism policy; firstly, the re-emergence of “Islam as a political force.” The revival of Islam as a political force was indicated by the spontaneous formation of various Islamic revivalist organizations as well as “Islamic political parties.” The

Islamic ‘revivalist’ organizations that emerged among others, included Majelis

Mujahidin Indonesia (MMI), Hisbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI), Front Pembela Islam

(FPI), Forum Komunikasi Ahlussunah wal Jamaah (FKJAWJ).59 In the meantime,

the Islamic political parties which were formed, among others, included the

Prosperous Justice Party (PK/S), the Moon and Star Party (PBB) and the “New”

United Development Party (PPP).60 Within the new democratic environment, the Muslim revivalist organizations and the Islam-friendly parties freely express their political aspirations concerning various issues without government restraint.

58 Robert R. Alford and Roger Friedland, Powers of Theory: Capitalism, the State, and Democracy, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 83.

59 Most western scholars use pejorative terms, such as fundamentalist, radical, militant, Islamist,

hardliner, scriptualist Muslim, etc. This study uses a neutral term, “revivalist Muslim.” An analysis on

the main characteristics visions of these Islamic revivalist organizations after the downfall of New Order, see, Khamami Zada, ibid.

60 “Islamic parties” refer to “those that explicitly contain ‘Islam’ in their names, philosophies, or

19

On the issues of terrorism, they have tended to be suspicious of the US intentions in “the global war on terror” and perceive it as a “war against Islam.”61 They struggle to influence policy by putting opposite pressures on the government

not to be “too submissive to the US hidden agendas” in adopting various policy

responses towards terrorism.62 The Megawati and Yudhoyono governments avoided

any policy measures that could undermine their coalition with Muslim political forces.

Secondly, the re-emergence of democracy also gives more political space for other societal forces—especially, human rights defender groups—to influence the government policy. There are many human rights defender groups in the post New Order era, but the most energetic ones are, among others, KONTRAS, Imparsial, and the Muslim Lawyer Team (TPM). They are watchful towards any government policy initiatives and express concern that the government’s efforts to combat terrorism could undermine human rights, civil liberty and democratic principles as well as giving way to the potential re-emergence of a repressive regime. As a result, the government seeks to reach a compromise with those societal pressures and strike a balance between the importance of security and democracy. In short, the democratic regime and the rise of Muslim political activism as well as the vibrant civil society have turned out to be domestic constraints on the government counterterrorism policy.

International Pressures are the second determinant to influence the direction of

the government’s counterterrorism policy. Besides facing societal pressures originating from the domestic political environment, the state also has to interact with other states on the international front. K.J. Holsti argues that the international political process commences when any state seeks through various acts or signals to change or sustain

20

the behaviour of other states. Power can thus be defined as “the general capacity of a

state to control the behaviour of others.”63 Alvin Rubenstein argues that “influence”

in international politics is manifested when state A affects the behaviour of state B through non-military means, directly or indirectly, so that state B responds to the policy to the advantage of state A.Roles played by A and B will be sometimes referred

to as ‘influencer’ and ‘influencee’ or influence target. Over time, the definition has gained some currency among scholars who study influence relationships among state actors.64

David Singer defines ‘influence’ as the ways that state A tries to shape the

behaviour of state B. State A manages to make state B act according to state A’s

wishes, in order to strengthen state A’s benefits or interests. State B is not inclined to

act to serve country A’s interests unless state A acts in such a persuasive and forceful

manner as to alter state B’s behaviour. All influence attempts are future oriented.65 State A may rely on state B’s past and present behaviour in order to predict and, if

possible, influence state B’s behaviour. However, state A’s predictions are far from

certain. In other words, if state A is confident that country B would behave according

to state A’s interests, state A’s desire to influence state B would decline. Therefore,

state A must distinguish a boundary line among state B’s perceived, predicted, and

preferred behaviours.66

63 K.J. Holsti, “Power, Capability, and Influence in International Politics,” in The Global Agenda, Issues and Perspectives, edited by Charles W. Kegley Jr., and Eugene W. Wittkopf, 6th edition, (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001),14.

64 Alvin Rubenstein, quoted in Chookiat Panaspornprasit, US-Kuwaiti Relations 1961-1992, (London: Routledge), 2005.

65 David Singer, “Inter-Nation Influence: a Format Model,” in International Politics and Foreign Policy: A Reader in Research and Theory, edited by James N Rosenau, (New York: Free Press, 1969), 381.

21

K.. J. Holsti demonstrates that state A can use six different tactics to influence state B.67 Firstly, persuasion. A initiates or discusses a proposal with B and elicits a favourable response without explicitly holding out the possibility of punishments. Secondly, the offer of rewards. In this situation, A promises to do something favourable to B if B complies with the wishes of A. Thirdly, the granting of rewards. In some instances, the credibility of A is not very high, and, before complying with

A’s wishes, B may insist that A actually gives the reward in advance. Fourthly, the threat of punishment. A threatens to punish B if it does not comply. Fifthly, the infliction of non-violent punishment. In this situation, threats are carried out in the

hope of altering B’s behaviour, which in most cases, could not be altered by other

means. Finally, the use of force. A actually uses force to make B comply with A’s

demands.68

In this study, the term “international pressures” refers to the pressures exerted

by the US—supported by its allies—on the Indonesian government to take policy measures in accordance with the US demands. The United States is the sole super power in the contemporary world politics that, during the Bush Administration, declared a so-called “a global war on terror” (GWOT) since the 9/11 tragedy. The US

assertively demanded other states to join in the GWOT, initiated “regime change” in

Afghanistan and Iraq, and exerted pressures on “reluctant” states. Using various

instruments—diplomatic, economic, technical assistance—the US exerted pressure on

the ‘reluctant‘ Indonesian government to follow their perspectives.

Previous Studies

67 K. J. Holsti, International Politics: A Framework for Analysis, 7th Edition, (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1995), 125-6.

22

The production of scholarly works on terrorism and counterterrorism has increased

considerably since the tragedy of 9/11 and Bush’s subsequent “global war on terror.”

Correspondingly, the works on Southeast Asia are also abundant. In general, the main works on terrorism in Southeast Asia can be classified into three major themes, first, who the terrorists in Southeast Asia and Indonesia are; second, regional terrorist groups and their connection with the global terror network, Al-Qaeda; third, the root causes of terrorism.69

Firstly, who are the terrorists? The various studies of terrorism in Southeast Asia focus on the who and what of terrorist activity, having at their core descriptive compilations of names, dates and meetings involving terrorists, or terrorist-related, individuals and groups as well their historical background.70 Various articles written by Sydney Jones of the Brussels-based International Crisis Groups (ICG) provides the most detailed analysis on the topic.

Sydney Jones’ early work that sparked controversy in Indonesia is an article on

the “Ngruki Network.” She wrote, “One network of militant Muslims has produced all

the Indonesian nationals so far suspected of links to Al-Qaeda.… The network has as its hub a religious boarding school (pesantren or pondok) near Solo, Central Java,

69 A good review on the major works on terrorism in Southeast Asia, see, Natasha Hamilton-Hart,

“Terrorism in Southeast Asia: Expert Analysis, Myopia and Fantasy,” The Pacific Review, vol. 18 no. 3, (September 2005): 303-25. This literature review benefits mostly from her mapping of the major works on terrorism in Southeast Asia.

70 Sydney Jones writes numerous articles on terrorism in Indonesia. Most of her articles are in

International Crisis Group (ICG), among others, “Al-Qaeda in Southeast Asia: the Case of the Ngruki

Network in Indonesia,” ICG Asia Briefing, (8 August 2002); “Indonesian Backgrounder: How the Jemaah Islamiyah Terrorist Network Operated,” ICG Asia Report, (11 December 2002); “Jemaah Islamiyah in South East Asia: Damage, but Still Dangerous,” ICG Asia Briefing, (26 August 2003);

23

known as Pondok Ngruki, after the village where the school is located.”71 Sydney Jones has unique access and meticulous information on “militant” Muslim activists

because of her past involvement in advocating the oppressed “militant” Muslim

activists during the New Order regime. After the collapse of the New Order and the

rise of the “global war on terror,“ she uses her previous abundant data on Muslim

“militants” and unconsciously turns herself from a human rights activist into a

prominent terrorism expert in Indonesia.72

Secondly, what is their connection with the global terror network, Al-Qaeda? The international dimensions of terrorist activity in Southeast Asia have also been headlined in a substantial section of the works on terrorism in the region.73 Much of

the urgency and profiles of such work rest on claims that terrorism in the region is no longer the province of local groups engaged in long-running struggles against their governments but has acquired a more threatening dimension through links to Al-Qaeda. Since most sources concur that the direct Al-Qaeda presence in the form of transplanted cell members transferred from the Afghanistan-based organization only ever amounted to a small number of individuals, the more significant terrorist presence is portrayed as consisting of local groups with connections to Al-Qaeda. Al-Jemaah Al-Islamiyah is the primary Southeast Asian group treated in almost all accounts as a terrorist organization linked to Al-Qaeda, if not part of Al-Qaeda itself.74

71 Sydney Jones, “Al-Qaeda in Southeast Asia…” 1

72 Sidney Jones, “The Political Impact of the ‘War on Terror’ in Indonesia,” Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University, Working Paper No. 116, (No year): 1.

73 Hamilton-Hart, 305.

74 Peter Chalk, “Al-Qaeda and its Links to Terrorist Groups in Asia,” in The New Terrorism: Anatomy, Trends and Counter-Strategies, edited by Andrew Tan and Kumar Ramakrishna (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2002), 107-28, Rohan Gunaratna, Inside Al Qaeda: Global Network of Terror (New Delhi: Roli Books, 2002), 198-203; Zachary Abuza, “Tentacles of Terror: Al Qaeda’s Southeast Asian

Network, “Contemporary Southeast Asia, Volume 24, Number 3, December (2002); Zachary Abuza, Militant Islam in Southeast Asia: Crucible of Terror (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publisher, 2003);

24

Finally,what is the root causes of terrorism?75 Works on the cause of terrorism

can be viewed from two main angles: those which are religion-driven and those which are politics-driven. Both types of explanations introduce the concept of radicalization to explain the readiness to employ strategies of violence, particularly terrorist violence.76 (a) Religion-driven explanations of terrorism maintain that the

deployment of Islam as an emotive force to mobilize violence is a distortion of proper religious teachings, and it is therefore the radical or extremist versions of Islam that are threatening.77Attention to the propagation of radical Islamist goals/ objectives/ rhetoric is frequently matched with recommendations to take an “ideological”

response to terrorism, that is, to combat the spread of terrorist behaviour or militant

sympathies by disseminating “good Islamic teachings, placing curbs on religious

schools, preachers and publications, and enlisting the support of “moderate Islamic

figures.”

(b) Politics-driven explanations of terrorism take the spotlight off religion to emphasize concrete grievances and local experiences of marginalization, repression, and political conflict.These studies place most emphasis on local agendas, historic

75 Hamilton-Hart, 316. 76 Hamilton-Hart, 316-20.

77 Maftuh Abugabriel, et.al, Negara Tuhan [State of God]: the Thematic Encyclopaedia, (Yogyakarta:

Multi Karya Grafika, 2004); Martin Bruinessen, “Genealogies of Islamic Radicalism in post-Suharto

Indonesia,” South East Asia Research 10 (2) (2002); Noorhaidi Hasan, “Faith and Politics: the Rise of the Laskar Jihad in the Era of Transition in Indonesia,” Indonesia 73 (April, 2002); Robert Hefner,

“Civic Pluralism Denied? The New Media and Jihadi Violence in Indonesia “in New Media in the Muslim World: The Emerging Public Sphere (2ndedition ) edited by Dale Eickelman and Jon Anderson, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003); Zachary Abuza, Militant Islam in Southeast Asia: Crucible of Terror, (Boulder, CO: Lynne Reinner, 2003); Endang Turmudi and Riza Sihbudi, Islam dan Radikalisme di Indonesia [Islam and Radicalism in Indonesia], (Jakarta, LIPI Press, 2005); Mike Millard, Jihad in Paradise: Islam and Politics in Southeast Asia, (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2004); Gunaratna, Rohan, Inside Al-Qaeda: Global Network of Terror, (New York: Berkley Books, 2003),

Kumar Ramakrishna, “Constructing the Jemaah Islamiyah Terrorist: A Preliminary Enquiry” IDSS Working Paper no.71 (Singapore, 2004); Kumar Ramakrishna, “Countering Radical Islam in

Southeast Asia: The Need to Confront the Ideological ‘Enabling Environment,” in ‘Terrorism and Violence in Southeast Asia edited by Paul J. Smith, (New York: ME Sharpe, 2005); Kumar

25

grievances and politics at the national or sub-national levels, even if global sympathies serve to frame motives and interests. In line with their emphasis on underlying political causes, they advocate counter-terrorism strategies that would remedy the conditions of economic marginalization, social injustice or political repression.78

From the review of the major literature on terrorism and counterterrorism

above, it is apparent that works which specifically focus their analyses on Indonesia’s

counterterrorism policy remain rare but by no means non-existent. For instance,

William M. Wise’s Indonesia’s War on Terror has investigated the threat of terrorism

and Indonesia’s policy response. He highlights the desirability of law reform and

improving Indonesia’s intelligence capabilities.79 Using Boaz Ganor’s framework,

Robert E. Tumanggor’s Indonesia’s Counterterrorism Policy has also investigated the efficacy of Indonesia’s counterterrorism policy. Unfortunately, neither of the works

yet provides systematic analyses on “why the government did what it did.” Similarly,

Anthony L. Smith’s the Politics of negotiating the terrorist problem in Indonesia also investigates Indonesia’s response to terrorism.80 Unfortunately, his analysis focuses

only on the domestic political environment and neglects international factors to

explain the shaping of the government’s counterterrorism policy.

To fill the gap in the existing works on Indonesia’s counterterrorism policy, therefore, this book attempts to provide a systematic analysis on the government counterterrorism policy in the context of domestic and international politics. The

78 John Gershman, “Is Southeast Asia the Second Front? “ Foreign Affairs 81 (4) (2002): 60-74; James

Putzel, “Political Islam in Southeast Asia and the US-Philippine Alliance,” in Global Responses to Terrorism: 9/11, Afghanistan and Beyond, edited by Mary Buckley and Rick Fawn (London: Routledge, 2003), 176-87; David Wright-Neville, “Dangerous Dynamics: Activists, Militants and Terrorists in Southeast Asia, The Pacific Review 17(1) (2004): 27-46; David Leheny, “Terrorism,

Social Movements, and International Security: How Al Qaeda Affects Southeast Asia,” Japanese Journal of Political Science 6(1) (2005): 1-23.