Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:05

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Gender Differences in Business Faculty's Research

Motivation

Yining Chen & Qin Zhao

To cite this article: Yining Chen & Qin Zhao (2013) Gender Differences in Business Faculty's Research Motivation, Journal of Education for Business, 88:6, 314-324, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.717121

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2012.717121

Published online: 26 Aug 2013.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 309

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.717121

Gender Differences in Business Faculty’s

Research Motivation

Yining Chen and Qin Zhao

Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green, Kentucky, USA

The authors use expectancy theory to evaluate gender differences in key factors that motivate faculty to conduct research. Using faculty survey data collected from 320 faculty members at 10 business schools, they found that faculty members, both men and women, who displayed higher motivation were more productive in research. Among them, pretenured faculty were motivated by extrinsic rewards; conversely, posttenured faculty were motivated by intrinsic rewards. Gender differences were observed in faculty’s overall and intrinsic motivations. Specifically, female faculty displayed higher overall and intrinsic motivations than male faculty, and such a gender difference was especially profound between posttenured female and male faculty. Faculty members, both men and women, considered receiving tenure and promotiosn to be the most important research motivations. Other important motivational factors included salary raises, satisfying a need for creativity–curiosity, and staying current.

Keywords: business faculty, expectancy theory, gender differences, research motivation, research productivity

In the progression of higher education, scholarly activities and research productivity habe become increasingly cru-cial elements in the quality of education across all busi-ness schools. Research productivity is also critically related to individual faculty member’s compensation, promotions, tenure, prestige, and marketability. Many research studies have documented that publication requirements for promo-tions and tenure have increased over time (Campbell & Mor-gan, 1987; Cargile & Bublitz, 1986; Englebrecht, Iyer, & Patterson, 1994; Milne & Vent, 1987; Read, Rama, & Raghu-nandan, 1998), and a number of studies have successfully identified and examined individual or institutional factors that most significantly influence the research productivity of faculty members (Cargile & Bublitz, 1986; Diamond, 1986; Goodwin & Sauer, 1995; Hu & Gill, 2000; Levitan & Ray, 1992). Existing literature, however, has provided limited dis-cussion of motivational factors and how they affect faculty research productivity, and few have examined the gender differences in faculty’s research motivation.

Correspondence should be addressed to Yining Chen, Western Kentucky University, Department of Accounting, 1906 College Heights Boulevard, Bowling Green, KY 42104, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

LITERATURE REVIEW

Factors Influencing Research Productivity

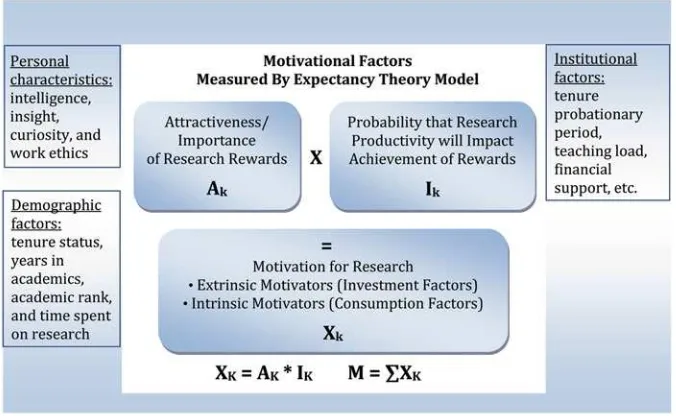

Prior studies have examined the factors that considerably in-fluence the research productivity of faculty members (Cargile & Bublitz, 1986; Diamond, 1986; Goodwin & Sauer, 1995; Hu & Gill, 2000; Levitan & Ray, 1992). Without a doubt, per-sonal characteristics such as intelligence, insight, curiosity, and work ethic have an influence, but other observable and systematic traits can also be important indicators of schol-arly achievement. Prior studies have identified the following factors that can influence research productivity (Buchheit, Collins, & Collins, 2001; Cargile & Bublitz, 1986; Chow & Harrison, 1998). Among them, the demographic factors are tenure status, allocated working time to research activities, and academic rank; and the institutional factors are length of the tenure probationary period, teaching loads, and financial research support.

Some scholars believe that external rewards, such as promotion, have a motivating effect on research productivity. For instance, Fox (1985) suggested that higher education institutions can influence faculty research behavior through manipulation of the reward structure for promotion. Other researchers, however, insist that faculty publish not for ex-ternal rewards but because they enjoy the process of inquiry

(McKeachie, 1979). Overall, prior studies have identified two categories of motivational factors that drive academic research: (a) investment factors or extrinsic rewards (e.g., salary increase, tenure, and promotion) and (b) consumption factors or intrinsic rewards (e.g., an individual’s personal satisfaction from solving research puzzles, contributing to the discipline, and achieving peer recognition). Based on a well-established research productivity theory, life-cycle theory, Hu and Gill (2000) suggested that in general the research productivity of a researcher rises sharply in the initial stages of his or her career, peaks at the time of tenure review, and then begins to decline. They indicated that pretenured research productivity is dominated by investment factors and extrinsic rewards and posttenured productivity by consumption factors and intrinsic rewards.

Motivation and Achievement

Motivation is the basic drive for human actions. Forms of motivation include extrinsic, intrinsic, physiological, and achievement motivation. Achievement motivation can be de-fined as the need for success or the attainment of excellence. Individuals will satisfy their needs through different means, and are driven to succeed for varying reasons both internal and external (Rabideau, 2005). Based on reaching success and achieving aspirations in life, motivation for achievement represents a desire to show competence, which affects the way a person performs a task (Harackiewicz, Barron, Carter, Lehto, & Elliot, 1997).

Motivation for achievement includes three generic moti-vational factors that influence outcome attainment: (a) atti-tude or belief about one’s capability to attain the outcome, (b) drive or desire to attain the outcome, and (c) strategy or techniques employed to attain the outcome (Tuckman, 1999). Recent experimental research demonstrates a contributive in-fluence of each proposed factor on academic engagement and achievement. Pintrich and Schrauben (1992) reviewed a large body of research that suggested that the value of an outcome to the student affects his or her motivation, and motivation leads to cognitive engagement that manifests itself in the use or application of various learning strategies. By and large, researchers have explored and evidenced the critical relation-ship between motivation, engagement, and achievement. The current knowledge base in motivation gained from this line of research offers hope and possibilities for educators-teachers, parents, coaches, and administrators to enhance motivation for achievement.

Gender and Achievement Motivation

The role of gender in shaping achievement motivation has a long history in psychological and educational research. Early studies drew on achievement motivation theories (e.g., attri-bution, expectancy, self-efficacy, and achievement goal per-spectives) to explain why adult women and men differed in

their educational and occupational pursuits and achievement (Meece, Glienke, & Burg, 2006). Developing from traditional research on achievement motivation and achievement behav-ior, many successive studies contemplated or challenged the stereotyped gender differences typically found in areas such as science and mathematics performance (Hyde & Kling, 2001). Research in science and medical disciplines found general support that female faculty published less than did their male colleagues. Cole and Singer (1991) found that gen-der differences in the effects of family roles, such as marital and parenting responsibilities, can adversely affect women’s achievement in the scientific research community. Xie and Shauman (1998) reported empirical evidence that the dif-ferences in research productivity between female and male scientists declined over time, and that most of the differences could be attributed to personal characteristics, structural po-sitions, and marital status. Nakhaie (2008) discovered that, in aggregate, Canadian female scientists published signif-icantly less than their male counterparts; these differences were largely accounted for by differences in rank, years since PhD, discipline, type of university, and time set aside for research. Barnett et al. (1998) took a different angle by eval-uating the relationships between both internal and external career-motivating factors and academic achievement among full-time medical faculty, and found that female faculty pub-lished less than did their male colleagues, but this difference could not be accounted for by gender differences in career motivation.

Despite the notable literature, Broadbridge and Simpson (2011), in their review of the gender research in the past 25 years, urged researchers to continue monitoring and pub-licizing gender differences and to reveal hidden gendered practices and processes currently concealed within norms, customs, and values. Moreover, the gender differences of faculty’s research motivation and the effects of motivational factors on the research productivity appear to have received limited attention in broader literature. Our study fills this gap by examining the gender differences in faculty’s research motivation (behavioral intention) and its relationship with actual research productivity in a constructive manner using expectancy theory.

Perspective Behavioral Theories

Expectancy theory has been recognized as one of the most promising conceptualizations of individual motivation (Fer-ris, 1977). Many researchers have proposed that expectancy theory can provide an appropriate theoretical framework for research that examines an individual’s acceptance of and in-tention to use a system or devote to a pursuit (DeSanctis, 1983). However, empirical research employing expectancy theory within academe has been limited.

Expectancy models are cognitive explanations of human behavior that cast a person as an active, thinking, predicting

creature in his or her environment. He or she continuously evaluates the outcomes of his or her behavior and subjectively assesses the likelihood that each of his or her possible actions will lead to various outcomes. The choice of the amount of effort he or she exerts is based on a systematic analysis of (a) the values of the rewards from these outcomes, (b) the likelihood that rewards will result from these outcomes, and (c) the likelihood of attaining these outcomes through his or her actions and efforts.

According to Vroom (1964), expectancy theory shows that the overall motivation (M) of a faculty member to conduct research is the summation of the products of the attractiveness of various individual outcomes associated with research (Ak)

and the probability that research will produce those outcomes (Ik):

where M is motivation for conducting research, Akis

attrac-tiveness (or value or importance) of outcome k associated with research productivity, and Ikis the perceived

probabil-ity (or impact) that being productive in research will lead to outcome k.

In our application of the expectancy theory, each faculty evaluates the attractiveness of 13 possible outcomes result-ing from performresult-ing research. He or she then considers the likelihood that each of these outcomes will occur. Accord-ing to expectancy theory, the faculty member would multiply the attractiveness of each outcome by the probability of its occurrence. He/she then sums these resulting products to materialize his or her total motivation to conduct research. Based on this systematic configuration, the faculty member determines how much effort he or she would like to exert in conducting research.

The conceptual framework depicted in Figure 1 includes the factors that may influence faculty’s research productiv-ity with a focus on the motivational factors measured by expectancy theory. Based on the conceptual framework, we then proceed to consider the related scholarly work and to generate a set of hypotheses for further advancements in this area.

RESEARCH OBJECTIVE AND HYPOTHESIS

Our first research objective was to investigate the gender effects on the relationship between research motivation and research productivity. Prior studies substantiate that there is a positive correlation between research productivity and motivation for research rewards (Chandra, Cooper, Cornick, & Malone, 2011; Chen, Gupta, & Hoshower, 2006; Tien, 2000). Specifically, those who show higher total motivation for research rewards display better research performance.

Though it is expected that gender can have some observable effects, the exact nature of those effects is open to question. Based on the literature reviewed and the research objectives discussed above, we formulated the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):There will be a positive correlation be-tween research productivity and motivation, and the pos-itive correlation will be observable in both male and female faculty.

Literature also suggests that the pretenured research pro-ductivity is dominated by investment (extrinsic) factors and posttenured productivity by consumption (intrinsic) factors (Hu & Gill, 2000). In order to examine whether this asser-tion applies to both male and female faculty, we posited the following hypotheses.

H1a:For both pretenured male and female faculty, research productivity will be positively correlated with extrinsic motivation but not with intrinsic motivation.

H1b:For both posttenured male and female faculty, research productivity will be positively correlated with intrinsic motivation but not with extrinsic motivation.

The second research objective was to discover the gender differences in faculty’s research motivation; in other words, to determine whether male and female faculties have different regard in various research motivations. Because pretenured and posttenured faculty can be radically different in their re-search motivation and preferences of the rewards, we analyze the gender differences across all faculty members as well as by group. Based on the research objectives discussed previ-ously and the literature to date, we formulated the following hypotheses:

H2:Male and female faculty members will be comparable in their motivation for research.

H2a: Pretenured male and female faculty members will be comparable in their extrinsic motivation for research.

H2b: Posttenured male and female faculty members will be comparable in their intrinsic motivation for research.

METHOD

We selected Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business–accredited colleges of business at 10 Midwestern universities with a balanced teaching and research mission. These ten universities are Carnegie Research Classification II research universities that do not offer PhD programs in the business college. They have similar research expecta-tions and academic standards. Questionnaires (see Appendix) were mailed to 670 business faculty members exclusive of non–tenure-track faculty. Between the original mailing and the one reminder mailing, we received 320 useable question-naires, representing a 48% response rate.

FIGURE 1 Conceptual framework: factors influencing faculty research productivity (color figure available online).

The questionnaire asked each faculty member to evaluate the importance of the thirteen research rewards to him or her (Ak) and his or her perceived probability that research

pro-ductivity would result in each of the thirteen rewards at his or her school (Ik).1Of the 13 rewards, six are extrinsic and six

intrinsic. The six extrinsic rewards are (a) receiving or hav-ing tenure, (b) behav-ing a full professor or receivhav-ing promotion, (c) receiving better salary raises, (d) receiving an administra-tive assignment, (e) receiving a chaired professorship, and (f) receivinga reduced teaching load. The six intrinsic rewards are (a) achieving peer recognition, (b) gaining respect from students, (c) satisfying a personal need to contribute to the field, (d) satisfying a personal need for creativity–curiosity, (e) satisfying a personal need to collaborate with others, and (f) satisfying a personal need to stay current in the field. The thirteenth reward, the ability to find a better job at another university, is probably an extrinsic reward because a better job probably means higher pay, better research support, and a lower teaching load. However, a better job could mean higher prestige and sense of achievement, which is an intrin-sic reward. Even though this thirteenth reward is probably an extrinsic reward, we segregated it from the other six extrinsic rewards, because, unlike the other six extrinsic rewards, it cannot be part of the reward system of the faculty member’s current university.

The questionnaire also collects demographic information such as academic discipline, gender, time allocated to re-search, academic rank, tenure status, research output during his or her entire academic career, and research output during the past 24 months. The summary statistics of these respon-dents’ profile and demographic information are provided in Tables 1 and 2.

RESULTS

Respondent Profile

Among the 320 respondents reported in Tables 1 and 2, 232 (72%) were men and 88 (28%) were women. Though the male and female samples were not even in size, they both

TABLE 1 Respondent Profile

Men Women

Characteristic n % n %

Total sample 232 72 88 28

Discipline

Accounting 53 22.8 16 18.2

Finance 29 12.5 9 10.2

Management information systems 22 9.5 4 4.5

Marketing 43 18.5 20 22.7

Human resource management 12 5.2 8 9.1 Organization behavior 8 3.4 9 10.2

Business law 11 4.7 6 6.8

Management (includes decision science, production, operations management, and quantitative business analysis)

22 9.5 6 6.8

Other 32 13.8 10 11.4

Rank

Full professor 120 51.7 16 18.2

Associate professor 76 32.7 37 42.0 Assistant professor 34 14.7 24 38.6 Tenure status

Tenured 193 83.2 52 59.1

Untenured 38 16.3 36 40.9

TABLE 2

Book chapters or cases (Y2) 0.16 0.13 .781

Journal articles (Y3) 1.13 1.36 .053

Grants (in$000) (Y4) 5.57 3.55 .313

Research output in the last 24 months

Books (Y5) 0.32 0.05 <.001

Book chapters or cases (Y6) 0.47 0.33 0.113

Journal articles (Y7) 2.87 2.83 0.894

Grants (in$000) (Y8) 23.03 7.00 0.177

Percentage of time spent in research

27% 32% 0.035

Number of years in academic employment

19.33 10.90 <.001

were representative of various disciplines and academic ranks and are sufficient for statistical tests. The male sample has a larger proportion of tenured faculty (83.2%) than the female sample (59.1%), which makes the by-group (pretenured and posttenured) analysis indispensable. In terms of research activities, male faculty members are more productive than female faculty in publishing books both in the per-year average and in the last 24 months. Unlike the findings of prior gender studies in science and medical disciplines, which found male faculty to be more productive than female faculty, our results indicate no significant dif-ference between male and female faculty’s journal articles published, book chapters published, and grants received. Noteworthy is that female faculty’s per year average journal articles published in academic career is higher than that of male faculty and the difference is marginally significant with apvalue .053.2Female business faculty also indicates

higher percentage of time spent in research.

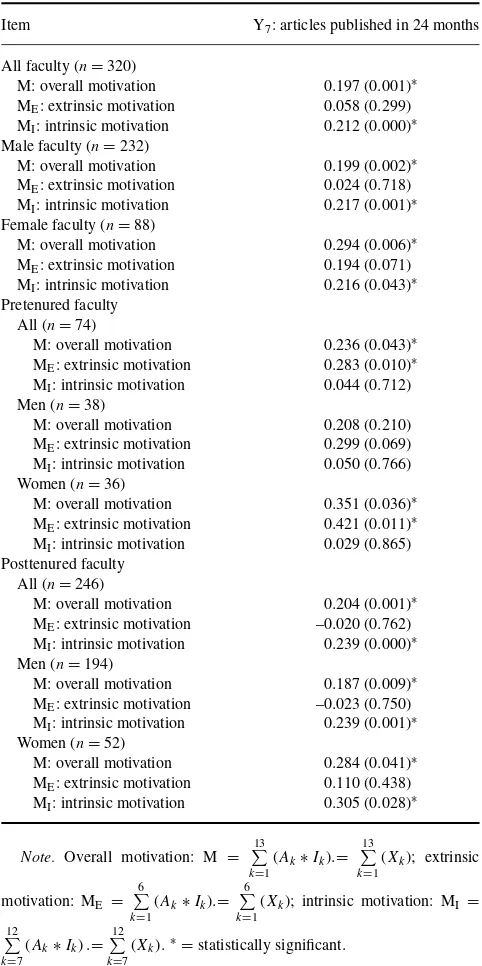

Hypothesis 1

Table 3 presents the Pearson’s correlation coefficients and significance levels (p values) between research motivation and research productivity. Journal articles published in the last 24 months (Y7) was used as the primary measure of

research productivity.3The correlations were calculated for

the aggregate faculty as well as male and female faculty individually. We tested the hypothesis with a .05 level of significance.

Results shown in Table 3 indicate a significant positive correlation (Pearson correlation coefficient=.197 andp= .001) between overall research motivation and research pro-ductivity. The by-gender analysis shows similar results, as male faculty evidences a correlation of .199 (p=.002) and female faculty evidences a correlation of .294 (p =.006).

TABLE 3

Motivation for Research and Research Productivity Pearson’s Correlation Coefficients andpValues

(in Parentheses)

Item Y7: articles published in 24 months

All faculty (n=320)

Note. Overall motivation: M =

13

These results supportH1that there is a positive correlation between research productivity and motivation, and the posi-tive correlation is observable in both male and female faculty. Evidently, the assertion made by literature, that faculty who show higher research motivation are more active and produc-tive in research, stays true for both male and female faculty. We further examine the correlation between research pro-ductivity and motivation by tenure status, by gender, and within each subgroup. For the pretenured and posttenured faculty, a significant positive correlation between research

productivity and overall research motivation was evident with Pearson correlations of .204 (p=.001) and .236 (p=.043), respectively. These results align withH1, concerning positive correlation between research productivity and motivation, and such positive correlation was observed in both pre and posttenured faculty. The results of the by-gender analyses in-dicate that significant positive correlation between research productivity and research motivation was evident among the posttenured male (Pearson correlation=.187,p=.009) and female faculty (Pearson correlation =.284 andp=.041), and among the pretenured female faculty (Pearson correla-tion=.351,p=.039). For the pretenured male faculty, the correlation was marginally significant (Pearson correlation =.299,p=.069).

In terms of faculty driven by different motivations be-fore and after receiving tenure, our results indicate that, for pretenured faculty, research productivity is dominated by ex-trinsic factors but not by inex-trinsic factors, where a significant positive correlation was observed between research produc-tivity and extrinsic research motivation (Pearson correlation =.238,p=.010), but not between research productivity and intrinsic research motivation (Pearson correlation=.044,p

=.712). The positive correlation between research produc-tivity and extrinsic research motivation was observed in both female and male pretenured faculty, with the correlation be-ing significant for women (Pearson correlation=.421,p= .011) and marginally significant for men (Pearson correlation =.299,p=.069). Despite this, no significant correlation is observed between research productivity and intrinsic moti-vation for both the male (Pearson correlation =.050,p= .766) and female (Pearson correlation = .029, p = .865) pretenured faculty. Based on these results, we attain general support forH1athat for pretenured male and female faculty research productivity was positively correlated with extrin-sic motivation but not intrinextrin-sic motivation. The assertion that pretenured research productivity would be dominated by in-vestment (extrinsic) factors was applicable to both pretenured male and female faculty.

On the other hand, for the posttenured faculty, research productivity is expected to be dominated by intrinsic factors rather than extrinsic factors. Based on the results presented in Table 3, a significant positive correlation was observed be-tween research productivity and intrinsic research motivation (Pearson correlation=.239,p=.000), but not between re-search productivity and extrinsic rere-search motivation (Pear-son correlation= −.020,p=.762) for all posttenured fac-ulty. These results can be observed in both male and female posttenured faculty. Consequently, we can conclude thatH1b

was supported, whereas, for both posttenured male and fe-male faculty, research productivity was positively correlated with intrinsic motivation, but not with extrinsic motivation.

Hypothesis 2

Table 4 presents the means, standard deviations, and equity test results (two-tailedt-tests andpvalues) of motivational

factors between male and female faculty. From Panel A, we find significant difference between male and female faculty’s overall research motivation as well as intrinsic research mo-tivation. Specifically, female faculty revealed higher overall and intrinsic motivation than male faculty did, with thep val-ues oft-tests being .01 and .00, respectively. As a result, our results did not extend support forH2, that male and female faculties would comparable in their research motivations. Though pretenured male and female faculty are comparable,

t(0.11)=0.11 andpvalue=0.92) in their extrinsic research motivations which supports H2a, posttenured male and female faculty are not comparable in their intrinsic research motivations. Female posttenured faculty demonstrate signif-icant higher intrinsic motivation,t= −2.79,p=.01, than do male posttenured faculty. H2b, therefore, is not supported. By and large, we find no cross-border support that male and female faculties are comparable in their research motiva-tions. Female faculty displayed significantly higher intrinsic research motivation than did male faculty and such a differ-ence is primarily driven by the significantly higher intrinsic research motivation found in posttenured female faculty.4

Given the research design by expectancy theory that re-search motivation (Xk) is the product of the faculty’s

per-ceived attractiveness and importance of the research rewards (Ak) and the faculty’s perceived impact of research

produc-tivity on achieving those rewards (Ik), we performed itemized

analyses in order to better understand the drivers of differ-ences observed between male and female faculty. Panel B of Table 4 reports faculty’s perceived attractiveness or impor-tance of various research rewards (Ak) and Panel C reports

the faculty’s perceived impact of research productivity on achieving various rewards (Ik). The results of Panels B and

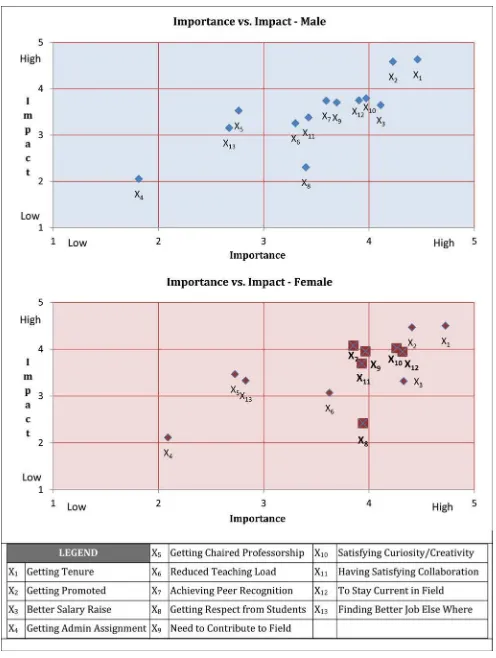

C are also combined and plotted in Figure 2.

From the itemized results presented in Panel B of Table 4, we found that among the 13 research rewards, both male and female faculty perceived receiving or having tenure (A1),

re-ceiving promotion (A2), and getting a better salary raise (A3)

to be the most important research rewards with the highest means, and getting an administrative assignment (A4) to be

the least important one. Among the six intrinsic rewards, though the perceived importance did not vary as much, male faculty considered satisfying the need for creativity or cu-riosity (A10) to be the most important, and female faculty

considered satisfying the need to stay current (A12) to be the

most important intrinsic research reward. Regarding faculty’s perceived impact of research productivity on achieving the 13 research rewards, results in Panel C of Table 4 indicate that both male and female faculty perceived research productivity as having the greatest impact on receiving tenure (I1) and

pro-motion (I2), and having the least impact on getting an

admin-istrative assignment (I4). Among the six intrinsic rewards,

male faculty perceived that research productivity has the greatest impact on satisfying a need for creativity or curiosity (I10), and female faculty perceived that research productivity

has the greatest impact on achieving peer recognition (I7).

FIGURE 2 Research importance versus impact (color figure available online).

TABLE 4

Gender Differences of Research Motivation

Male Female Equity test

Research reward (motivation factor) M SD M SD t p

Panel A: Motivation for research (Xk)

All faculty

Overall motivation (M) 171.45 45.28 184.28 39.02 –2.51 0.01∗

Extrinsic motivation (ME) 81.24 25.72 80.66 23.41 0.19 0.85

Intrinsic motivation (MI) 80.47 30.26 92.48 25.29 –3.59 0.00∗

Posttenured faculty

Overall motivation (M) 168.42 45.86 179.23 41.95 –1.62 0.11

Extrinsic motivation (ME) 80.58 26.44 78.31 23.69 0.60 0.55

Intrinsic motivation (MI) 78.95 30.32 90.5 25.42 –2.79 0.01∗

Pretenured faculty

Overall motivation (M) 186.92 39.18 191.58 33.59 –0.55 0.58

Extrinsic motivation (ME) 84.61 21.69 84.06 22.90 0.11 0.92

Intrinsic motivation (MI) 88.21 29.14 95.33 25.17 –1.13 0.26

Panel B: Attractiveness–importance of research rewards to faculty (Ak)a

Extrinsic:

A) Receiving or having tenure (A1) 4.46 1.21 4.72 0.74 –2.38 0.02∗

B) Receiving promotion (A2) 4.23 1.16 4.41 0.84 –1.54 0.13

C) Getting better salary raises (A3) 4.11 1.11 4.33 0.94 –1.75 0.08

D) Getting an administrative assignment (A4) 1.81 1.05 2.09 1.45 –1.83 0.07

E) Getting chaired professorship (A5) 2.76 1.52 2.73 1.34 0.20 0.84

F) Getting reduced teaching load (A6) 3.30 1.37 3.63 1.21 –2.06 0.04∗

Intrinsic:

G) Achieving peer recognition (A7) 3.59 1.16 3.85 0.98 –1.99 0.05∗

H) Getting respect from students (A8) 2.40 1.31 3.94 1.00 –3.96 0.00∗

I) Satisfying need to continue (A9) 3.69 1.08 3.97 0.96 –2.18 0.03∗

J) Satisfying need for creativity or curiosity (A10) 3.97 1.06 4.26 0.90 –2.42 0.01∗

K) Having collaborations with others (A11) 3.43 1.07 3.93 0.96 –4.07 0.00∗

L) Satisfying need to stay current (A12) 3.91 0.98 4.32 0.70 –4.18 0.00∗

Other:

M) Finding a better job (A13) 2.67 1.45 2.83 1.44 –0.87 0.39

Panel C: Faculty’s perceived impact of research productivity on achieving various rewards (Ik)b

Extrinsic:

A) Receiving or having tenure (I1) 4.63 0.73 4.50 0.95 1.20 0.23

B) Receiving promotion (I2) 4.59 0.79 4.47 1.01 1.01 0.31

C) Getting better salary raises (I3) 3.65 1.39 3.32 1.51 1.78 0.08

D) Getting an administrative assignment (I4) 2.05 1.03 2.11 1.06 –0.47 0.64

E) Getting chaired professorship (I5) 3.53 1.50 3.47 1.52 0.32 0.75

F) Getting reduced teaching load (I6) 3.25 1.46 3.07 1.45 1.02 0.31

Intrinsic:

G) Achieving peer recognition (I7) 3.74 1.14 4.08 0.91 –2.75 0.01∗

H) Getting respect from students (I8) 2.30 1.12 2.42 0.94 –0.95 0.34

I) Satisfying need to continue (I9) 3.70 1.09 3.95 1.11 –1.82 0.07

J) Satisfying need for creativity or curiosity (I10) 3.79 1.12 4.02 0.97 –1.81 0.07

K) Having collaborations with others (I11) 3.38 1.09 3.69 1.05 –2.36 0.02∗

L) Satisfying need to stay current (I12) 3.75 1.04 3.94 0.84 –1.72 0.08

Other:

M) Finding a better job (I13) 3.16 1.52 3.33 1.65 –0.86 0.39

∗Significant at the 0.5 level.

aResponses were rated on a scale of 1 (not important at all) to 5 (very important). bResponses were rated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Looking into the gender differences from the equity test results in Panel B of Table 4, we found that female fac-ulty perceived all but one (getting chaired professorship) re-search reward as more attractive/important than male faculty did. This difference is especially recognizable in intrinsic

research rewards. Thet-tests indicate significant difference between male and female faculty for all six intrinsic research rewards. For extrinsic motivational factors, female faculty considered five of six of them more attractive and important than male faculty did. Among the five, two were significant

and two were marginally significant. These results led to the conclusion that female faculty had higher regard toward various research rewards and incentives than did male fac-ulty. This difference is especially compelling among intrinsic research rewards.

In terms of the faculty’s perceived impact of research pro-ductivity on achieving various rewards reported in Panel C, female faculty agreed more than do male faculty that research productivity has an impact on intrinsic research rewards. The difference was significant in two of the intrinsic rewards (I7

[achieving peer recognition] and I11 [having collaborations

with others]) and marginally significant in three others. On the other hand, the difference in the extrinsic rewards is not significant between male and female faculty. In general, we can conclude that female faculty is more convinced that re-search productivity leads to intrinsic rewards.

According to the expectancy theory, motivation for research (Xk) is the product of faculty’s perceived

attrac-tiveness and impact of research rewards (Ak) and faculty’s

perceived impact of research productivity on achieving perspective research rewards (Ik). Figure 2 depicts the

com-bined results from Panel B (Ak) and Panel C (Ik) of Table 4.

For both female and male faculty, receiving tenure (X1)

and promotion (X2) remained the top two motivations for

research, followed by getting salary raises (X3), satisfying a

need for creativity/curiosity (X10), and staying current (X12).

Though details are not reported, we conducted equity test between male and female faculty’s motivation for research (X1 to X13) and found significant differences in six out of

the thirteen motivational factors (as noted by enlarged marks in Figure 2). It is noteworthy that all of the motivational factors that differ significantly between male and female faculty are intrinsic factors (i.e., achieving peer recognition [X7], getting respect from students [X8], need to contribute

to field [X9], satisfying curiosity and creativity [X10], having

satisfying collaboration [X11], and staying current in field

[X12]). This finding provides further evidence to confirm our

findings inH2that male and female faculty members are not comparable in their research motivations and the difference is especially substantial in intrinsic motivations.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This study applies expectancy theory to examine research motivations of business faculty focusing on gender differ-ences. Overall, we found a positive correlation between re-search productivity and rere-search motivation, and such a cor-relation was observable in both female and male faculty. While examining whether faculty are driven by different motivational factors before and after receiving tenure, our results indicate that, for both male and female pretenured faculty, research productivity was dominated by extrinsic factors but not by intrinsic factors, and for both male and

fe-male posttenured faculty by intrinsic factors but not extrinsic factors. Altogether, our results offer support that pretenured research productivity is associated with investment (extrin-sic) factors and posttenured productivity with consumption (intrinsic) factors; no gender difference is found, and the assertion stays valid for both male and female faculty.

Moreover, we examined whether male and female fac-ulties differed in their research motivations and found that female faculty revealed higher research motivation than male faculty did. This broad-spectrum inequity was driven by fe-male faculty’s higher intrinsic research motivation, and such a gender difference is especially profound between posttenured female and male faculty. While examining the components of research motivation, we found that female faculty consider intrinsic research rewards (e.g., achieving peer recognition, receiving student respect, satisfying a need to sustain, satisfy-ing creativity and curiosity, havsatisfy-ing collaborations, and stay-ing current) more attractive and important than male faculty did; moreover, female faculty were more convinced that re-search success can lead to these rere-search rewards. In line with past research in education and psychology (Conti, Collins, & Paciriello, 2001; Daoust, Vallerand, & Blais, 1988; Vallerand et al., 1992), it appeared that female faculty displayed a more self-determined motivational profile than male faculty.

In summary, this study finds gender differences in fac-ulty’s research motivation. Female and male faculties at dif-ferent stages of their career are motivated by difdif-ferent re-search rewards. Results of this study can provide valuable intelligence for business colleges and higher education in-stitutions to analyze faculty’s research productivity, conduct annual evaluations, perform pretenured or posttenured as-sessment, construct incentive and rewarding systems, con-stitute promotion and tenure policies, and make hiring and promotion decisions. Moreover, with the knowledge gained from this study, institutions can actively influence faculty research behavior and stimulate faculty research motivation through the meticulous design of the reward structure for promotion and evaluation.

NOTES

1. We compiled this group of 13 factors from previous literature, a pilot study that asked the respondents to list other motivations, and from a focus group of 20 business faculty.

2. This gender difference was evidenced among both pre-tenured and postpre-tenured faculty, though not as signifi-cant.

3. We performed the same tests using the average per-year articles published in academic career (Y3) as the

measure of research productivity and found similar re-sults.

4. When examining the research productivity, post-tenured female faculty had higher short-term research

productivity (Y7) than posttenured male faculty do,

although the difference was not significant. Posttenured female faculty also had higher long-term research productivity (Y3) than did their male peers, and the

difference was marginally significant.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980).Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NY: Prentice Hall.

Bagozzi, R. P. (1982). A field investigation of causal relations among cog-nitions, affects, intentions and behavior.Journal of Marketing Research,

19, 562–584.

Barnett, R. C., Carr, P., Boisnier, A. D., Ash, A., Friedman, R. H., Moskowitz, M. A., & Szalacha, L. (1998). Relationships of gender and career motivation to medical faculty members’ production of academic publications.Academic Medicine,73, 180–186.

Bouvier, D., McLaughlin, J., & Conley, V. M. (2011). Females who teach business: Exploring the impact of positive and negative affect in the workplace.North American Management Society Proceedings,5(3–4), 27–38.

Bridgwater, C. A., Walsh, J. A., & Walkenbach, J. (1982). Pretenure and posttenure productivity trends of academic psychologists.American Psy-chologist,37, 236–238.

Broadbridge, A., & Simpson, R. (2011). 25 years on: Reflecting on the past and looking to the future in gender and management research.British Journal of Management,22, 470–498.

Brownell, P., & McInnes, M. (1986). Budgetary participation, motivation, and managerial performance.Accounting Review,61, 587–600. Buchheit, S., Collins, A. B., & Collins, D. L. (2001). Intra-institutional

factors that influence accounting research productivity.The Journal of Applied Business Research,17(2), 17–31.

Campbell, D. R., & Morgan, R. G. (1987). Publication activity of promoted accounting faculty.Issues in Accounting Education,2(1), 28–43. Cargile, B. R., & Bublitz, B. (1986). Factors contributing to

pub-lished research by accounting faculties.The Accounting Review,61(1), 158–178.

Chandra, A., Cooper, W. D., Cornick, M. F., & Malone, C. F. (2011). A study of motivational factors for accounting educators: What are their concerns?Research in Higher Education Journal,11(6), 19–36. Chen, Y., Gupta, A., & Hoshower, L. B. (2006). Factors that motivate

business faculty to conduct research: An expectancy theory analysis.

Journal of Education for Business,81, 179–189.

Chow, C. W., & Harrison, P. (1998). Factors contributing to success in research and publications: Insights of “influential” accounting authors.

Journal of Accounting Education,16, 463–472.

Cole, J. R., & Singer, B. (1991). A theory of limited differences: Explaining the productivity puzzle in science. In H. Zuckerman, J. R. Cole, and J. T. Bruer (Eds.),The outer circle: Women in the scientific community

(pp. 277–310). New York, NY: Norton.

Conti, R., Collins, M. A., & Paciriello, M. L. (2001). The impact of compe-tition on intrinsic motivation and creativity: Considering gender, gender segregation and gender role orientation.Personality and Individual Dif-ferences,31, 1273–1289.

Daoust, H., Vallerand, R. J., & Blais, M. R. (1988). Motivation and educa-tion: A look at some important consequences.Canadian Psychology,29, 172 (abstract).

DeSanctis, G. (1983). Expectancy theory as an explanation of voluntary use of a decision support system.Psychological Reports,52, 247–260.

Diamond, A. M. (1986). The life-cycle research productivity of mathemati-cians and scientists.Journal of Gerontology,41, 520–525.

Englebrecht, T. D., Iyer, G. S., & Patterson, D. M. (1994). An empirical investigation of the publication productivity of promoted accounting fac-ulty.Accounting Horizons,8(1), 45–68.

Ferris, K. R. (1977). A test of the expectancy theory as motivation in an accounting environment.The Accounting Review,52, 605–614. Fox, M. F. (1985). Publication, performance, and reward in science and

scholarship. In J. C. Smart (Ed.),Higher education: Handbook of theory and research(Vol. 1, pp. 255–282). New York; NY: Agathon Press. Goodwin, A. H., & Sauer, R. D. (1995). Life cycle productivity in academic

research: Evidence from cumulative publication histories of academic economists.Southern Economic Journal,61, 729–743.

Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Carter, S. M., Lehto, A. T., & Elliot, A. J. (1997). Predictors and consequences of achievement goals in the college classroom: Maintaining interest and making the grade.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,73, 1284–1295.

Hu, Q., & Gill, T. G. (2000). IS faculty research productivity: Influential factors and implications.Information Resources Management Journal,

13(2), 15–25.

Hyde, J. S., & Kling, K. C. (2001). Women, motivation, and achievement.

Psychology of Women Quarterly,25, 364–378.

Lane, J., Ray, R., & Glennon, D. (1990). Work profiles of research statisti-cians.The American Statistician,44, 9–13.

Levitan, A. S., & Ray, R. (1992). Personal and institutional characteris-tics affecting research productivity of academic accountants.Journal of Education for Business,67, 335–341.

McKeachie, W. J. (1979). Perspective from psychology: Financial incen-tives are ineffective for faculty. In D. R. Lewis and W. E. Becker (Eds.),

Academic rewards in higher education(1–28). Cambridge, England: Ballinger Publishers.

Meece, J. L., Glienke, B. B., & Burg, S. (2006). Gender and motivation.

Journal of School Psychology,44, 351–373.

Milne, R. A., & Vent, G. A. (1987). Publication productivity: A comparison of accounting faculty members promoted in 1981 and 1984.Issues in Accounting Education,2(1),94–102.

Nakhaie, M. R. (2008). Gender differences in publication among university professors in Canada.Canadian Review of Sociology,39, 151–179. Pintrich, P. R., & Schrauben, B. (1992). Students’ motivational beliefs and

their cognitive engagement in classroom academic tasks. In D. Schunk & J. Meece (Eds.),Students perceptions in the classroom: Causes and consequences(pp. 149–183). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rabideau, S. T. (2005).Effects of achievement motivation on behavior. Retrieved from http://www.personalityresearch.org/papers/rabideau.html Read, W. J., Rama, D. V., & Raghunandan, K. (1998). Are publication requirements for accounting faculty promotions still increasing?Issues in Accounting Education,13, 327–339.

Tien, F. F. (2000). To what degree does the desire for promotion motivate faculty to perform research?Research in Higher Education,41, 723–752. Tuckman, B. W. (1999, December).A tripartite model of motivation for achievement: Attitude/drive/strategy. Paper presented in the Sympo-sium: Motivational Factors Affecting Student Achievement—Current Perspectives, Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Associ-ation, Boston.

Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Briere, N. M, Senecal, C., & Vallieres, E. F. (1992). The academic motivation scale: A measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education.Educational and Psychological Measurement,52, 1003–1017.

Vroom, V. C. (1964),Work and motivation. New York, NY: Wiley. Xie, Y., & Shauman, K. A. (1998). Sex differences in research productivity:

New evidence about an old puzzle.American Sociological Review,63, 847–870.

APPENDIX

Faculty Motivation to Conduct Research

This brief questionnaire is designed to understand faculty motivation to conduct research. We greatly appreciate your taking time to provide meaningful input. Your responses will be kept confidential. Your name or the name of your institution will not be revealed in any of our reports or articles.

1. As a faculty, please evaluate the importance of the following to you using a scale of 1 to 5, ranging from 1 (not important at all) to 5 (very important).

Not

Importance of the following important Very

to me: at all important

a. To have tenure 1 2 3 4 5

b. To be full professor or receive promotion

1 2 3 4 5

c. Get better salary raises 1 2 3 4 5 d. Get an administrative

assignment

1 2 3 4 5

e. Get a “Chaired Professorship”

1 2 3 4 5

f. Get reduced teaching load 1 2 3 4 5 g. To achieve peer recognition 1 2 3 4 5 h. To get respect from students 1 2 3 4 5 i. To satisfy my need to

contribute to the field

1 2 3 4 5

j. To satisfy my need for creativity / curiosity

1 2 3 4 5

k. To have pleasure of collaborating with others

1 2 3 4 5

l. To satisfy my need to stay current in field

1 2 3 4 5

m. To find a better job at another University

1 2 3 4 5

2. Based on your perception, please evaluate the impact of your research productivity on achieving the follow-ing usfollow-ing a scale of 1 to 5, rangfollow-ing from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

My research productivity has an Strongly Strongly

high impact on: disagree agree

g. Achieving peer recognition 1 2 3 4 5 h. Getting respect from students 1 2 3 4 5 i. Satisfying my need to contribute

to the field

1 2 3 4 5

j. Satisfying my need for creativity / curiosity

1 2 3 4 5

k. Getting pleasure of collaboration with others

1 2 3 4 5

l. Satisfying my need to stay current in field

1 2 3 4 5

m. Finding a better job at another University

1 2 3 4 5

3. Based on your experience and expectations of your College’s environment, please evaluate the impact of faculty research productivity on achieving the follow-ing usfollow-ing a scale of 1 to 5, rangfollow-ing from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

At my college / school, faculty

research productivity has an Strongly Strongly

high impact on: disagree agree

a. Receiving tenure 1 2 3 4 5

b. Receiving promotion 1 2 3 4 5

c. Getting better salary raises 1 2 3 4 5 d. Getting an administrative

assignment

1 2 3 4 5

e. Getting a “Chaired Professorship”

1 2 3 4 5

f. Getting reduced teaching load 1 2 3 4 5