SME Development in Indonesia and China

1Tulus Tambunan

Kadin Indonesia and Center for Industry and SME Studies, University of Trisakti, Indonesia

LIU Xiangfeng

Institute for International Economic Research, NDRC, China

1. Background

From a worldwide perspective, it has been recognized that small and medium enterprises (SMEs) play a vital role in economic development, as they have been the primary source of job/employment creation and output growth, not only in developing but also in developed countries. In Piper’s (1997) dissertation, for instance, it states that 12 million or about 63.2% of total labor force in the United States (US) work in 350,000 firms employing less than 500 employees, which considered as SMEs. According to Aharoni (1994), SMEs make up more than 99% of all business entities and employ more than 80% of total workforce in this country. These enterprises, often called the foundation enterprises, are the core of the US industrial base (Piper, 1997). SMEs are also important in many European countries. In the Netherlands, for instance, they account for 95% or more of total business establishments (Bijmolt and Zwart, 1994). As in the US, also in other industrialized/OECD countries such as Japan, Australia, Germany, French and Canada, SMEs are an important engine of economic growth and technological progress (Thornburg, 1993).

In developing countries, SMEs have also a crucial role to play because of their potential contributions to improvement of income distribution, employment creation, poverty reduction, export growth and development of entrepreneurship, industry and rural economy. According to Levy et al (1999), there is no doubt that the performance of SMEs is extremely important for the economic development of most less-developed countries. For this reason, the governments in these countries have been supporting their SMEs extensively through many programs, with subsidized credit schemes as the most important component. International institutes such as the World Bank and the United Nation Industry and Development Organisation (UNIDO) and many donor countries through bilateral co-operations have also done a lot, financially as well as technically, in empowering SMEs in developing countries. .

In developing Asia, SMEs have made significant contributions over the years measured in terms of their share in: (a) number of enterprises; (b) employment; (c) production and value added; (d) GDP; (e) enterprises set up by women entrepreneurs; and (f) regional dispersal of industry, among others. The contribution of SMEs is vital in as much as they, by and large: (a) make up 80-90% of all enterprises; (b) provide over 60% of the private sector jobs; (c) generate 50%-80% of total employment; (d) contribute about 50% of sales or value added (VA); (e) share about 30% of direct total exports (Narain, 2003).

1

With this background, the main aim of this paper is to discuss recent development of SMEs in Indonesia and China as two case studies. By focusing on SMEs in these two countries, this paper addresses two issues: their contributions to the economy and their main constraints.

2. The Role of SMEs in the Economy

It is widely suggested in the literature that the importance of SMEs in developing countries is because of their characteristics, which include the following ones2

1) Their number is huge, and especially small enterprises (SEs) and micro enterprises (MIEs)3are scattered widely throughout the rural areas and therefore they may have a special "local" significance for the rural economy. 2) As being populated largely by firms that have considerable employment growth potential, their development or

growth can be included as an important element of policy to create employment and to generate income. This awareness may also explain the growing emphasis on the role of these enterprises in rural development in developing countries. The agricultural sector has shown not to be able to absorb the increasing population in the rural areas. As a result, rural migration increased dramatically, causing high unemployment rates and its related socio-economic problems in the urban areas. Therefore, non-farm activities in rural areas, especially rural industries being a potentially quite dynamic part of the rural economy have often been looked at their potential to create rural employment, and in this respect, SMEs can play an important role.

3) Not only that the majority of SMEs in developing countries are located in rural areas, they are also mainly agriculturally based activities. Therefore, government efforts to support SMEs are also an indirect way to support development in agriculture.

4) SMEs use technologies that are in a general sense more "appropriate" as compared to modern technologies used by large enterprises (LEs) to factor proportions and local conditions in developing countries, i.e. many raw materials are locally available but capital, including human capital, is very limited.

5) Many SMEs may expand significantly, while the great majority of MIEs tend to grow little and hence do not graduate from that size category. Therefore, SMEs are regarded enterprises having the “seedbed LEs” function. 6) Although in general people in rural areas are poor, existing evidence shows the ability of poor villagers to save a

small amount of capital and invest it; they are willing to take risks by doing so. In this respect, SMEs provide thus a good starting point for the mobilization of both the villagers' talents as entrepreneurs and their capital; while, at the same time, rural SMEs can function as an important sector providing an avenue for the testing and development of entrepreneurial ability.

7) SEs and MIEs finance their operations overwhelmingly by personal savings of the owners, supplemented by gifts or loans from relatives or from local informal moneylenders, traders, input suppliers, and payments in advance from consumers. These enterprises can therefore play another important role, namely as a means to allocate rural savings that otherwise would be used for unproductive purposes. In other words, if productive activities are not available locally (in the rural areas), rural or farm households having money surplus might keep

2

More discussions on this, see for example, Tambunan (1994), Liedholm and Mead (1999), and Berry et al. (2001).

3

or save their money without any interest revenue inside their home because in most rural areas there is a lack of banking system. Or, they use their wealth to buy lands, cars, motorcycles or houses and other unnecessary luxury consumption goods which these items are often considered by the villagers as a matter of prestige.

8) Although many goods produced by SMEs are also bought by consumers from the middle and high-income groups, it is generally evident that the primary market for SMEs' products is overwhelmingly simple consumer goods, such as clothing, furniture and other articles from wood, leather products, including footwear, household items made from bamboo and rattan, and metal products. These goods cater to the needs of local low income consumers. SMEs are also important for securing the basic needs goods for this group of the population. However, there are also many SMEs engaged in the production of simple tools, equipments, and machines for the demands of farmers and producers in the industrial, trade, construction, and transport sectors.

9) As part of their dynamism, SMEs often achieve rising productivity over time through both investment and technological change; although different countries within the group of developing countries may have different experiences with this, depending on various factors. The factors may include the level of economic development in general and that of related sectors in particular; accessibility to main important determinant factors of productivity, particularly capital, technology and skilled manpower; and government policies that support development of production linkages between SMEs and LEs as well as with foreign direct investment (FDI). 4 10)As often stated in the literature, one advantage of SMEs is their flexibility, relative to their larger competitors. In

Berry et al. (2001), there enterprises are construed as being especially important in industries or economies that face rapidly changing market conditions, such as the sharp macroeconomic downturns that have bedeviled many developing countries over the past few years.

3. SMEs in Developing Asia

3.1 Definition

The definition and concept of SMEs vary widely among countries in the region. There is no common agreement on what distinguishes a microenterprise (MIE) from a small enterprise (SE), a SE from a medium enterprise (ME), and a ME from a large enterprise (LE). In general, however, a MIE employs less than five (5) full time equivalent employees; a SE is a firm with 5 to 19 workers in Indonesia and more than that in many other countries; and a ME may range from 20 to 50 employees or more. Moreover, definitions and concepts used for statistical purposes can vary from those used for policy or program purposes (for example, to determine eligibility for special assistance). All but a few countries have a definition for SMEs for statistical purposes. Many countries have also definitions for policy purposes, and to complicate matters further, these definitions often differ from the definition used for statistical purposes, as also differ by industry and by policy program.

4

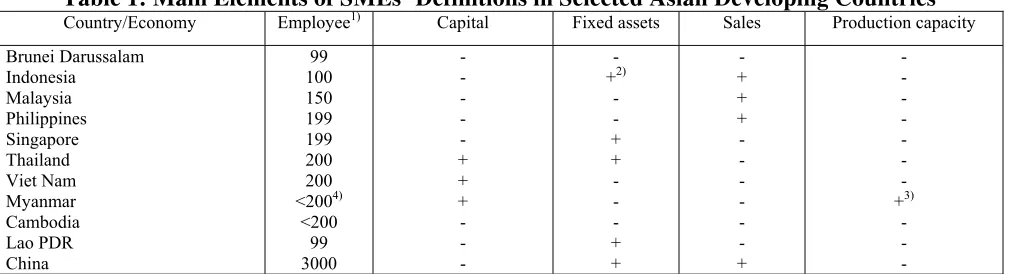

As shown in Table 1 the number of employees is the most common measure for many countries. However, some countries also use a monetary measure such as initial investment, including or excluding land and building, annual sales or turnover, or production capacity to define SMEs.5Even with the number employed, there is considerable diversity between the member countries.

Table 1: Main Elements of SMEs’ Definitions in Selected Asian Developing Countries

Country/Economy Employee1) Capital Fixed assets Sales Production capacity Brunei Darussalam

Notes: 1: figures indicate the maximum number of employees in a firm defined as an MSME; 2) : “+”as an element of the definition; 3) production value; 4) depends on sector.

Source: APEC (2003), UNESCAP (2004), Xiangfeng (2008), Tambunan, et al. (2008), Tambunan (2008).

What constitutes an SME also varies widely between countries. SMEs may range from a part time business with no hired workers or a non-employing unincorporated business, often called self-employed units, such as traditional business units making and selling handicrafts in rural Java in Indonesia, to a small-scale semiconductor manufacturers employing more than 10 people in Singapore. They may range from fast growing firms, to private family firms that have not changed much for decades or stagnated. They range from enterprises, which are independent businesses, to those, which are inextricably part of a large company, such as those, which are part of an international subcontracting network. The only true common characteristic of SMEs is that they are “not-large”; that is whether a firm is really a SME or not is relative.

Most enterprises form this SME category are actually very small and about 70% to 80% of them employ less than five (5) people. There are only a very small percentage of firms, typically ranging from about 1% to 4%, which have more than 100 employees. Unfortunately, there is no consistent definition of a MIE among countries.

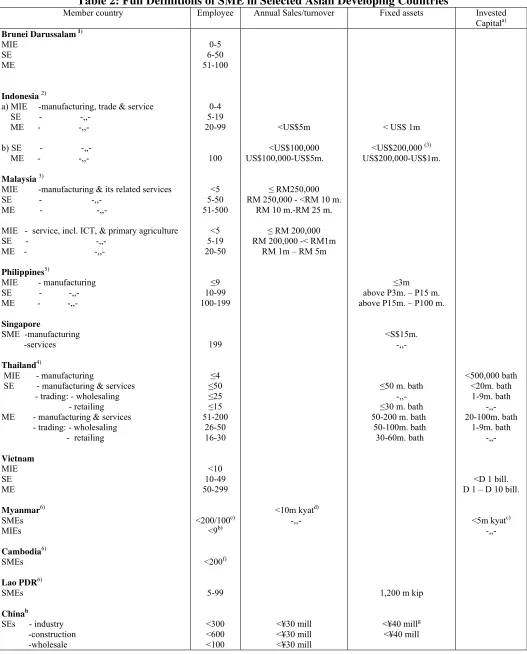

As presented in Table 2, some countries have definitions on MIEs, and most of these use 5 employees as a cut off. In practice, most MIEs are likely to be non-employing; they do not actually employ anyone, but they do create jobs and some incomes, even if only part time jobs, for the entrepreneurs. These MIEs make up the great majority of enterprises, usually comprising around 60% to 80% of all business establishments. Their contribution to employment is usually disproportionately small, and they typically contribute only about 10% to 40% of available jobs. However, as stated in the report, the role of MIEs in creating jobs tends to be greater in the future

5

in some countries, where they provide a higher proportion of jobs, or where they create job opportunities that would not otherwise be available.

Table 2: Full Definitions of SME in Selected Asian Developing Countries

Member country Employee Annual Sales/turnover Fixed assets Invested Capitala)

Brunei Darussalam 1) MIE

-retail -transport -post

-restaurant and hotel MEs - industry

-construction -wholesale -retail -transport -post

-restaurant and hotel

<100 <500 <400 <400 300-2,000 600-3,000 100-200 100-500 500-3,000 400-1,000 400-800

<¥10 mill <¥30 mill <¥30 mill <¥30 mill ¥30 mill-300 mill ¥30 mill-300 mill ¥30 mill-300 mill ¥10 mill-150 mill ¥30 mill-300 mill ¥30 mill-300 mill ¥30 mill-150 mill

¥40 mill-400 mill. ¥40 mill-400 mill.

Note: a) not including fixed assets; b) not limits for handicrafts; c) capital outlay; d) production value; e) depends on sector; f) industrial sector; g) total assets; h) SME meet one or more of the conditions. ME should meet three conditions, the others are SE.

Sources: 1) ASEAN-EU Partenariat ’97 (http://aeup.brel.com); (2) BPS = Central Bureau of Statistics (a) and the State Ministry of Cooperative and SMEs (b); 3) SMIDEC (2006); 4) ACTETSME.ORG (Website), except for MIE is from Allal (1999); 5) Sibayan (2005); 6): UNESCAP (2004); others: APEC (2003), Hall (1995), and Harvie and Lee (2002a), Xiangfeng (2008), Tambunan, et al. (2008), Tambunan (2008).

In Indonesia, there are several definitions of SMEs, depending on which agency provides the definition. The State Ministry of Cooperative and Small and Medium Enterprises (Menegkop & UKM) promulgated the Law on Small Enterprises Number 9 of 1995, which defines a SE as a business unit with total initial assets of up to Rp 200 million (about US$ 20,000 at current exchange rates), not including land and buildings, or with an annual value of sales of a maximum of Rp 1 billion (US$ 100,000), and a ME as a business unit with an annual value of sales of more than Rp 1 billion but less than Rp 50 billion. Although the Law does not explicitly define MIEs, Menegkop & UKM data on SEs include MIEs. The National Agency for Statistics (BPS), which regularly conducted surveys of SMEs, uses the number of workers as the basis for determining the size of an enterprise. In its definition, MIEs, SEs and MEs are business units with, respectively, 1-4, 5-19, and 20-99 workers, and LEs are units with 100 or more workers. The Ministry of Industry (MoI) defines enterprises by size in its sector also according to number of workers as the BPS definition.

SME definition in China depends on the industry category and is defined based on the number of employees, annual revenue, and total assets comprising a company. An industrial SME is defined as having up has up to 2,000 employees; while a ME has between 301 and 2,000 employees; and a SE has less than 300. Consequently, what is regarded as an SME in China may be quite large relative to an SME in other countries.

3.2 Performance

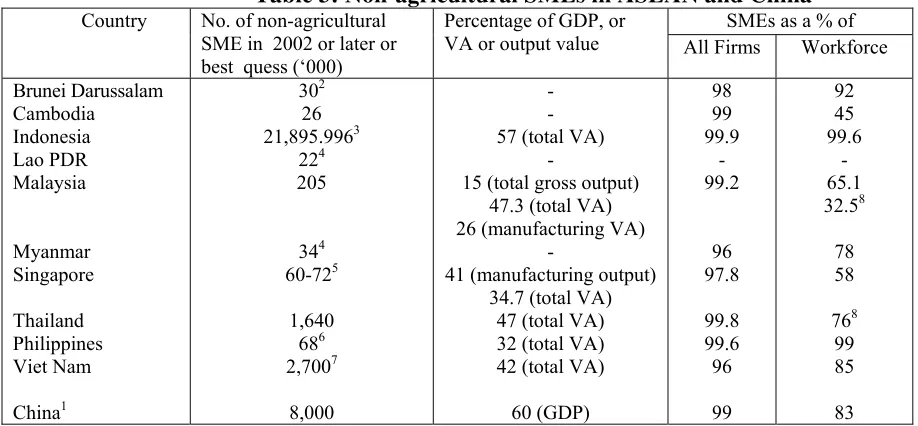

Asian developing countries have touted SMEs as the engine of economic growth and development, the backbone of national economies, the highest employment-generating sector, and a potential tool of poverty alleviation by creating self-employment avenues. This paper presents information on SMEs in ASEAN countries as a very important group within Asian developing countries, and China as a comparison. With respect to ASEAN, notwithstanding various definitional issues and data problems, by combining all sources which are available, there is an (rough) estimated total of some 21 million non-agricultural SME in this region, or about more than 90% of all non-agriculture firms in the region (Table 3). These enterprises play a strategic role in private sector development, especially in the aftermath of the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis. In some member countries, as their economies modernise or industrialise, SME provide the much-needed inter-firm linkages required to support LEs to ensure that they remain competitive in the world markets. SMEs generally account for between 20%-40% of total domestic output and they employ an overwhelming proportion (mostly in the 75%-90% range) of the domestic workforce, especially adult persons and women.6

On the other hand, in spite of the significance of these indicators, the SMEs’ VA contribution to the economy for most ASEAN countries has yet to commensurate with the sector’s size and socioeconomic potential. Wattanapruttipaisan’s (2004) own calculation shows that SME in ASEAN contribute a disproportionately limited share of 20% to 40% to gross sales value or manufacturing VA7In Singapore, for instance, the VA of SME is only 34.7% of the economy’s total VA, while their productivity is half that of LEs. Malaysian SME contributed only about 26% to manufacturing VA. In Thailand, commonly cited as a successful model for SME development in ASEAN, its SME contribution is only 47% of total VA.

In China, SMEs has been increasingly contributing to China’s economic growth. They make up over 99% of all enterprises in China today. The output value of SMEs accounts for at least 60% of the country's gross domestic product (GDP), generating about 83% of total employment opportunities in the country.

Comparatively, SMEs in the developed nations contribute about 50% of total VA in the European Union (EU), or, individually, for instance, SMEs in Germany are responsible for approximately 57% of the country’s

6

. A study conducted by the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) shows that women entrepreneurs own and operate up to 30% of SMEs in such as Indonesia, Philippines and the Republic of Korea (APEC 1999).

7

Gross National Product (GNP); between 40% and 50% of manufacturing output in Japan, Republic of Korea and Taipei, China; and in the United States (US) it is about 30% to total sales value.

Table 3: Non-agricultural SMEs in ASEAN and China

SMEs as a % of Country No. of non-agricultural

SME in 2002 or later or best quess (‘000)

Percentage of GDP, or

VA or output value All Firms Workforce

Brunei Darussalam

15 (total gross output) 47.3 (total VA)

Notes: 1: best guess for 2000; 2: est. active (2004); 3: includes MIEs (2006); 4: 1998/9; 5: estimated active; 6: excludes 744,000 MIEs (2001); 7: excludes 10 million MIEs; 8: manufacturing industry only.

Sources: APEC (2002), RAM Consultancy Services (2005), UNCTAD (2003), Hall (2002), Myint (2000), Regnier (2000), Ministry of Industry, Mines and Energy of the Kingdom of Cambodia, BPS (Indonesia), Census 2005 (Malaysia), JASME Annual Report 2004-2005 (Japan); SMEA (White Paper on SMEs in Taiwan 2005), OSMEP (White Paper on SMEs in Thailand, 2002), National SME Development Agenda 2000/2001 (Philippines), Xiangfeng (2008), Tambunan, et al. (2008), Tambunan (2008).

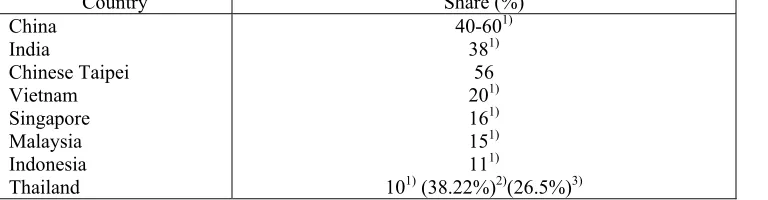

With respect to export, it reveals from Table 4 that in general ASEAN SMEs are not yet so strong in export as their counterparts in such as China, India, Chinese Taipei or South Korea; although the export intensity of ASEAN SMEs is different by country. For instance, in Indonesia the SMEs’ contribution to the country’s total export of non-oil and gas by the end of 1990s was only 11%, compared to Vietnam at 20%, or almost 27% in Thailand in 2003. Featuring prominently in SME exports from Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam are food products, textiles and garments, leather and plastic goods (including toys), furniture items, handicrafts, jewelry and, to a less extent, mature-technology automotive and consumer electronics parts.8Wattanapruttipaisan (2005) argues, however, that direct export of ASEAN SMEs might be low, but, if indirect contributions are taken into account, then their overall share in export earnings is certainly much larger because SMEs feature prominently as subcontractors to export-oriented local LEs and multinational companies (MNCs)9.

8

For further details, see Hill (1995, 2001, 2002), Rodriguez and Berry (2002), Steer and Taussig (2002); Regnier (2000), Tambunan (2000, 2006) and Tecson (2001).

9

Table 4: Share of SME exports in selected Asian Developing Countries, 1990s

Country Share (%)

China India

Chinese Taipei Vietnam Singapore Malaysia Indonesia Thailand

40-601) 381)

56 201) 161) 151)

111)

101) (38.22%)2)(26.5%)3)

Sources: 1) UNCTAD (2003); 2) Mephokee (2004): 38.22% in 2002 and 45.5% in 2003 of the country’s total export for industrial products; 3) White Paper on SMEs 2004 (Government of Thailand, website)

4. Indonesia

4.1 Economic Contribution

SMEs have historically been the main player in the Indonesian economy, especially as a large provider of employment opportunities, and hence a generator of primary or secondary sources of income for many households (Tambunan, 2006). Typically, Indonesian SMEs account for more than 90% of all firms (Table 5), and thus they are the biggest source of employment, providing livelihood for over 90% of the country’s workforce, especially women and the young. The majority of SMEs, especially the smallest units, i.e. MIEs are scattered widely throughout the rural area and therefore they may play an important role as a starting point for development of villagers' talents as entrepreneurs, especially those of women. MIEs are dominated by self-employment enterprises without hired paid workers. They are the most traditional enterprises, generally with low levels of productivity, poor quality products, and serving small, localized markets. There is little or no technological dynamism in this group. The majority of these enterprises are subsistence activities. Some of them are economically viable over the long-term, but a large portion is not. Many MIEs face closure or very difficult upgrading especially with import liberalization, changing technology and the growing demand for higher quality modern products. However, the existence or growth of this type of enterprise can be seen as an early phase of entrepreneurship development.

Table 5: Total Units of Enterprises by Size Category: 1997-2006 (000 units)

Size Category 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2003 2004 2005 2006

SEs 39,704.7 36,761.7 37,804.5 39705.2 39,883.1 43,372.9 44,684.4 47,006.9 48,822.9

MEs 60.5 51.9 51.8 78.8 80.97 87.4 93.04 95.9 106.7

LEs 2.1 1.8 1.8 5.7 5.9 6.5 6.7 6.8 7.2

Total 39,767.3 36,815.4 37,858.1 39789.7 39,969.995 43,466.8 44,784.14 47,109.6 48,936.8

Source: Menegkop & UKM (various issues).

simple traditional manufacturing activities such as wood products, including furniture, textiles, garments, footwear, and food and beverages. Only a small portion of total SMEs are engaged in production of machinery, production tools and automotive components. This is generally carried out through subcontracting systems with several multinational car companies such as Toyota and Honda. This structure of industry reflects the current technological capability of Indonesian SMEs, which are not yet as strong in producing sophisticated technology-embodied products as their counterparts in other countries such as South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan.

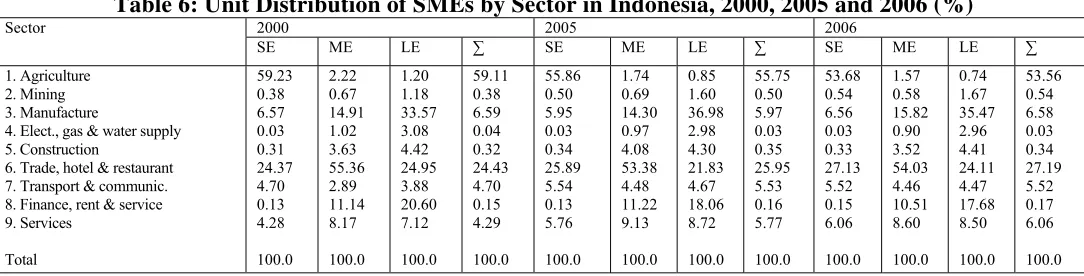

Table 6: Unit Distribution of SMEs by Sector in Indonesia, 2000, 2005 and 2006 (%)

2000 2005 2006

4. Elect., gas & water supply 5. Construction

6. Trade, hotel & restaurant 7. Transport & communic. 8. Finance, rent & service 9. Services Source: Menegkop & UKM (various issues).

With respect to the output structure, agriculture has always been the key sector for SEs, as they produce around 86% to 87% of total output in the sector. The second important sector for this group of enterprises is trade, hotel and restaurant with their annual share ranging from 74% to 76%. MEs, on the other hand has the largest output contribution in finance, rent & service at around 46% to 47%, followed by transportation and communication with a share ranging from the lowest 23.47% in 2006 to the highest 26.22% in 2001. In manufacturing industry, both SEs and MEs are traditionally not so strong as compared to LEs.

With respect to output growth, the performance of SMEs is relatively good as compared to that of LEs. The output growth of SEs and MEs was respectively 3.96% and 4.59% in 2001 and increased to 5.38% and 5.44%, respectively in 2006. LEs experienced, on the other hand, a growth rate of 3.04% and ended up at 5.60% during the same period. SMEs’ contribution to the annual GDP growth is also higher than that of LEs. In 2003, the GDP growth rate was 4.78%, from which 2.66% came from SMEs, compared to 2.12% from LEs. In 2005, the SMEs’ share in GDP growth reached the highest level at 3.18% before slightly declined to 3.06% in 2006. More interestingly, within the SME group, SEs’ contribution to the GDP growth is always higher than that of MEs. In 2006, from the GDP growth rate at 5.5%, about 2.15% is from SEs as compared to 0.91% cent from MEs.

much higher than that of SEs (Figures 2A and 2B). This significant gap may suggest that in the manufacturing industry, the ability of MEs to export is higher than that of SEs. The difference can be explained by differences in such as access to capital and market information, skills, promotion facilities, and external networks. Naturally, MEs are in a better position than SEs for all these factors, which are crucial in determining the successful of a firm in doing export.

Table 7: Exports of SMEs and LEs, 2000 and 2006 by Three Main Sector (billion rupiah)

2000 2006 Sector

SME LE SME LE Agriculture

Mining Manufacture

Total

8,396.3 6,57.0 66,395.3

75,448.6

427.5 74,490.8 357,135.5

432,053.8

12,662.7 1,621.3 107,915.5

122,199.5

1,078.8 153,874.3 501,170.5

656,123.6 Source: Menegkop & UKM

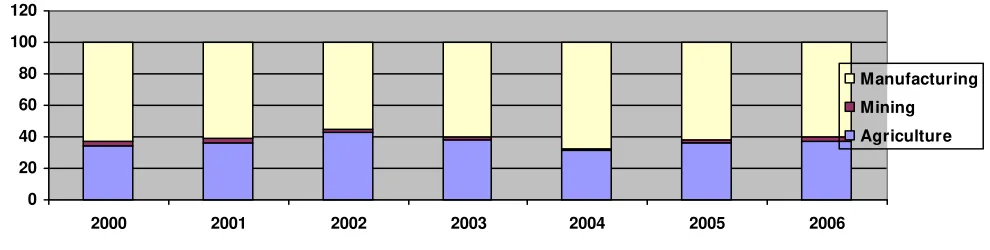

Figure 1: SMEs’ Contribution to Total Export Value, 2000-2006 (%)

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 SE ME LE

Source: Menegkop & UKM

Figure 2A: Distribution of SEs’ Export Value by Sector, 2000-2006 (%)

0 20 40 60 80 100 120

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006

Manufacturing

Mining

Agriculture

Source: Menegkop & UKM

period, the export share of MEs was 12.53% and improved to 14.72%. Previously, such as Hill (1997, 2001), Tambunan (2006b), and Thee (1993) argue that, although on average per year the export contribution of SMEs in Indonesia’s total manufacturing export is relatively small as compared to that of their larger counterparts, they seem to have shared nicely in the manufactured export boom in the 1980s and 1990s. Thee (1993) concludes that from the point of view of technology and adaptability, export growth of SMEs in manufacturing industry has been achieved substantially by finding niche markets and adapting costs and quality to market demand.

Figure 2B: Distribution of MEs’ Export Value by Sector, 2000-2006 (%)

0 20 40 60 80 100 120

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006

Manufacturing Mining Agriculture

Source: Menegkop & UKM

4.2 Constraints

The development of viable and efficient SMEs, particularly non-farm enterprises, is hampered by several constraints. The constraints may differ from region to region, between rural and urban, between sectors, or between individual enterprises within a sector. However, there are a number of constraints common to all SMEs. These common constraints faced by SMEs are the lack of capital, difficulties in procuring raw materials, lack of access to relevant business information, difficulties in marketing and distribution; low technological capabilities, high transportation costs; communication problems; problems caused by cumbersome and costly bureaucratic procedures, especially in getting the required licenses; and policies and regulations that generate market distortions.

RAM Consultancy Services’ (2005) report states that various impediments prevent SME in ASEAN from developing to their full potential. One of constraints faced by these enterprises is the lack of access to formal credit to finance their needed working capitals.10With limited working capital, it is hard for them to expand their production and hence to increase their share in total output. However, main constraints and the degree of

10

importance of each constraints faced by ASEAN SMEs vary by member country, depending on differences in many aspects including level of SMEs development, nature and degree of economic development, public policies and facilities, and of course also nature and intensity of government interventions towards SMEs.

In Indonesia, for instance, in 2003 BPS published the results of its survey on SMEs in manufacturing industry with some questions dealing with the main constraints facing the enterprises. As presented in Table 8, it reveals that not all of the producers surveyed see lack of capital as their serious business constraints. For those who face capital constraint are mainly MIEs located in rural/backward areas and they never received any credit from banks or from various existing government sponsored SME credit schemes. They depend fully on their own savings, money from relatives and credit from informal lenders for financing their daily business operations.

Table 8: Main Problems faced by SEs and MIEs in Manufacturing Industry, 2003

Note: * = % Source: BPS

Another main constraint is difficulty in marketing. SMEs facing this problem are those which usually do not have the resources to explore their own markets. Instead, they depend heavily on their trading partners for marketing of their products, either within the framework of local production networks and subcontracting relationships or orders from customers.

5. China

5.1 Economic Contribution

Currently, SMEs are an important part of China’s economy, and most of these enterprises came about in the last 15 years. With the opening up of China to market economy in the 1980s as part of the market-oriented reforms initiated by Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, private SMEs were finally recognised as vital to the country’s economic development.

The ensuing economic reforms involving state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China, major SOEs rapidly changed into small and medium non-SOEs until the end of 2004. Meanwhile, more SMEs sprouted, spurred by the implementation of non-SOE promotion policy. Since then urban collective enterprises, town and village enterprises (TVE), alongside the private sector and self-employment activities, have been sprouting and thriving all over China.

In 2007 a total of 4,459 LEs accounted for 0.19% of the total number of enterprises registered in the country; 4,2291 MEs, or 1.78%; and 2,327,969 SEs, or 98%, of the total. Overall, SMEs made up for 99.7% of the total number of companies operating in China at the time. Business revenue of SMEs accounted for 60.42% of total earnings, and SEs with 6.54 trillion, or 23.70%. The industrial income of SMEs accounted for 66.28%; with 11.77 trillion from SEs (37.29%).

As in Indonesia, SMEs in China are also playing an increasingly important role in employment generation and hence declining unemployment in the country. LEs employed 20,877.8 thousand individuals, or 18.11% of the total employment; whereas, MEs employed 35,464.3 persons (30.76%), and SEs 58,947.8 persons (51.13%).

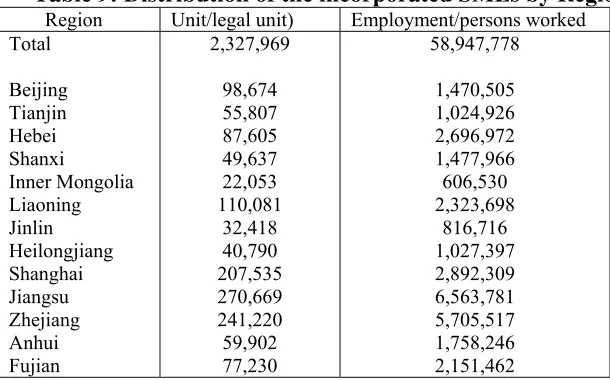

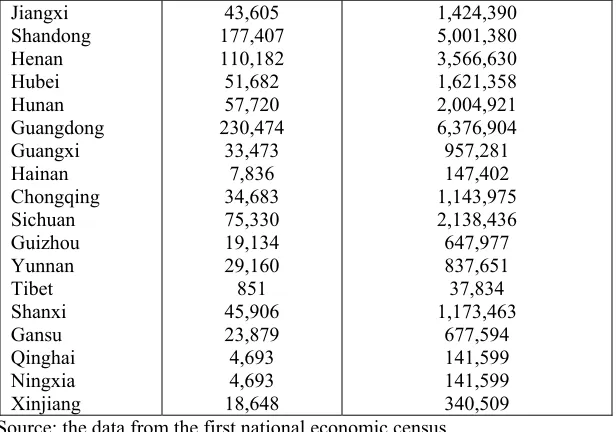

Based on regional distribution (Table 9), 68.58% of SMEs are located in the eastern area part, 20.14% in the mid-area, and 11.28% in the western part of China. SMEs in the top five provinces make up 48.4% of all SMEs. These provinces are all located in the eastern area of China, namely, Jiangsu, Zhengjiang, Guandong, Shanghai, and Shandong, which accounted for 11.6%, 11%, 10.4%, 9.9%, 8.9%, and 7.6% of all SMEs, respectively.

Table 9: Distribution of the incorporated SMEs by Region

Region Unit/legal unit) Employment/persons worked Total

Beijing Tianjin Hebei Shanxi

Inner Mongolia Liaoning Jinlin Heilongjiang Shanghai Jiangsu Zhejiang Anhui Fujian

2,327,969

98,674 55,807 87,605 49,637 22,053 110,081

32,418 40,790 207,535 270,669 241,220 59,902 77,230

58,947,778

1,470,505 1,024,926 2,696,972 1,477,966 606,530 2,323,698

Jiangxi

By sector distribution, the business revenue of manufacturing industry accounted for 52.8%, followed by the wholesale and retail (35.2%); construction (4.6%); and transportation and storage (2.6%). Further, based on the number of SMEs in the top three manufacturing industries, manufacture of general- purpose machinery leads with 9.2%, followed by metal products (6.7%), and textile (6.3%). (Table 10).

Table 10: Distribution of SMEs by Sector

Sector Unit/legal

-wearing apparel,food ware and caps

-raw chemical material and chemical products -plastics

-metal products

-general purpose machinery -special purpose machinery -transport equipment

-electrical machinery and equipment Electricity, gas and heat power Construction

Transport, storage and post

Information transmission, computer service and software wholesale and retail trade

Hotel and restaurants Financial intermediation Leasing and business services

Scientific research, technical service and geologic prospecting Management of water conservancy, environment and public fac. service to households and other services

2,327,969 Note: * including forestry, animal husbandry and fishing.

Distribution of registered types of SMEs is as follows: domestic enterprises in mainland China make up 96.1% of the total; Hong Kong-, Macao- and Taiwan-based enterprises, 2%; and foreign enterprises, 1.9%. Meanwhile, private enterprises comprise 66.1% of all SMEs (Table 11).

Table 11: Distribution of the incorporated SMEs by type of enterprises

Unit/Legal Entity

Employment/ person

Business Revenue of Whole Year/thousand

Total

Assets/thousand yuan

Total 2,327,969 58,947,778 6,535,425,319 7,229,524,125

Domestic enterprises 2,237,185 53,951,581 6,044,526,465 6,550,301,584 Private enterprises 1,538,315 32,481,099 3,950,057,989 3,084,959,621 Enterprises with funds from

Hongkong,Macao and Taiwan 46,315 2,814,528 246,579,103 340,220,847 Foreign funded enterprises 44,469 2,181,669 244,319,751 339,001,694 Source: The data from the first national economic census.

Finally, with respect to export, SME contribution to China’s total exports accounted for 62.3% of the total in 2006. Yet, the SEs contributed only between 5% and 10% to total exports, according to data from the China Private Economy Year Book for 2004-2006.11SEs’ modest contribution to China’s economy is further reinforced by the result of a survey conducted on 10,000 enterprises in 29 provinces (of which 3,339 were qualified enterprises) during that period (Table 12). Within SMEs, the ratio of external market of SEs to total exports is only around 18%, significantly lower than that of the MEs. The resulting data resulting from the survey showed that SE products are mainly focused on the domestic market.

Table 12: Product distribution of SME in China based on enterprise number

SME ME SE Eastern

area

Middle area

Western area

Province market 33.63 19.56 43.46 33.77 26.82 43.21

Other province

market in China 39.65 41.68 38.38 34.69 48.5 39.94

World market 26.72 38.76 18.16 31.54 24.68 16.85

Source: analysis of Questionnaire of SME financing in 2006. N=3339 (Http://www.sme.gov.cn).

5.2 Constraint

The followings are identified as the specific problems of SMEs in China. First, weak technological innovation. Technological innovations among SMEs in China come in four ways: internal R&D, imitation, licensing of know-how, and university- (and related institution)-led R&D. Figure 3 shows that the ratio of internal R&D to technological innovations is 54%; those of other three are 20%, 19.9% and 5.3%, respectively. Contributing the highest to income generation is imitation technology, followed by internal R&D, licensing of know-how, and

11

external R&D (or such efforts being pursued with university-based R&D and institute is the lowest. It appears that imitation is restricting the technological innovation of small enterprises, which in turn is borne of a inadequacy of funds (Liang 2007).

Figure 3: Technology Innovation of SMEs

Source: Data from the questionnaire of Small enterprises, NDRC.N=592.Http://www.sme.gov.cn

Second, inadequate financing. Lack of financial support is a major stumbling block to SME development in China. In particular, SMEs are beset by poor credit guarantee system, dearth of financial institutions supporting SMEs, extremely high stock market threshold, and inability to obtain bank loans owing to imperfect management and poor accounting system that discourages banks from lending to them. Based on a survey of 948 SEs on the issue of financing (Table 13), 73.3% of the respondents cited lack of a credit guarantee system (with an equivalent ratio of 36% relative to all other responses to the questionnaire) as their foremost concern, 73.3% of questionnaire SEs choose it (questionnaire enterprises can make several choices about the financing difficult of SEs).

Table 13: Difficulties of SE Financing

Reason of loan difficulties Measure for SME financing

Item system, though it has compensation ability

Poor profit ability 223 23.50% 11.50% need government

support fund 320 33.10% 12.70% of bank or financial institution

Lack credit institution 136 14.30% 7.10% Improve law

environment 151 15.60% 6%

Exceed Credit history 53 5.60% 2.70% Develop venture

capital 83 8.60% 3.30%

Develop non-bank

institution 74 7.60% 2.90%

Develop second

Board market 50 5.20% 2.00%

Notes: Due to multiple replies, 1928 replies was submitted from 948 enterprises. Source: Analysis of Questionnaire of SME in 2006.N=592. Http://www.sme.gov.cn

A Survey

A survey of SME clusters in three towns in Jiangsu Province has been conducted in November 2007.12These three towns clearly illustrate the concept of “one product, one town” in the Jiangsu province. The Guanlin cable cluster (comprising 12 small cable enterprises), the Shengze textile cluster (including six small textile enterprises), and the Hengshan sewing machine cluster (consisting of six small sewing machine makers) are engaged in the manufacture of metal products, textiles, and general machinery, respectively. These comprise the top three industries of China. The town of Guanlin is in Yixing City, Wuxi, Jiangsu Province. Started in the early 1980s, cable production in this town now boasts more than 200 cable enterprises, 20 of which have assets of at

12

least 100 million yuan, and eight have assets of 10 billion yuan or more. Cable output and sales account for 78% of the total industrial output of the town. Sales of cable enterprises in Guanlin and its surrounding towns account for more than one-third of the entire economic output of Yixing City, the largest cable production base nationwide.

Inspired by the rapid development of the cable industry, its auxiliary enterprises engaged in non-ferrous metal processing increased rapidly. Today, there are around 200 enterprises forming a complete industrial chain engaged in the manufacture of machines, auxiliary materials, metal rolls and cable coils. Guanlin also prides itself on having some 100 types of cable products with about a thousand specifications and over 10,000 varieties, including high-quality products.

Shengze, known as the “silk town,” has an extensive production line. It is one of four towns (the others being Suzhou, Hangzhou and Taihu) that were collectively called the major silk towns of China during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. The silk industry of Shengze has shifted from low- to high-quality materials, from textiles to R&D, from low to high-value added. Shengze has about 2,000 textile factories now, which have a combined 75,000 shuttleless looms. It has formed a textile production chain from silk reeling, polyester spinning, weaving, dyeing and finishing, deep processing of textiles to the manufacture of clothes and garments. It produces 2 million tons of polyester filaments, 6 billion meters of textiles, dyes and finishes, 2 billon meters of textiles; deep-processes 2 billion meters of textiles; and makes 50 million garments every year.

In 2006, the output value of Shengze’s textile industry was 36.032 billion yuan, accounting for over 90 percent of the total output of the town. The industry’s total taxes amounted to 600 million yuan, up 20.03 percent from 2005. Its employed personnel numbered 88,600, excluding 51,000 individuals working for it in the countryside.

The development of Shengze’s textile industry also helped to establish textile enterprises in its surrounding areas. Today it boasts a highly competitive textile production base operating in the areas around Shengze, which include Wujiang City, Jiaxing in Zhejiang, and some towns in Huzhou.

The sewing machine industry in Wanping, Hengshan began in the 1970s, continued on till the 1980s, and developed in the 1990s. Since then, SME clusters have been formed, which are marked by a closely coordinated production chain, strong collaboration among the small enterprises involved, strong and independent R&D efforts, and orientation to the domestic and international markets. Today there are over 30 sewing machine manufacturers and 162 related spare parts makers, who rely on a full gamut of production operations. The output of middle standard and thick-material sewing machines in Hengshan accounts for 30 percent of the total national output. At least 4,000 varieties of spare parts are produced in this town. Now the industry in Hengshan has over 170 patents, of which 30 to 40 patents are used every year.

These small enterprise clusters are marked by the following:

small enterprise clusters. SME clusters are driven by leading major enterprises, followed by affiliate enterprises, self-developed enterprises clusters, leading to the gradual evolution of the one industry, one region and one product, one town type of operation. Its regional reach has brought about expansion of production (Li Donglei 2005). The cable town in Guanlin, the silk town in Shengze, and the small sewing machine clusters in Hengshan exemplify the concept of such a regionalized layout. The presence of a large number of related enterprises in the same region will facilitate skills upgrade and enhance competitiveness, which in turn could speed up the sector’s pursuit of industrial clustering and technological innovation, as they take advantage of proximity, coordination, and ease of communication.

2) Specialization. SME clusters’ specialized operations help ensure their steady progress. Specialization comes about when enterprises clusters develop to a certain degree, resulting in the creation of professional divisions and steadily improving coordination. Along the way, some definite production processes will be spun off and turn into affiliated enterprises for some special processing. Hengshan town, for instance, is the production base of sewing machines for medium and heavy-duty materials. What started out as a small number of companies have grown to 162 parts manufacturing enterprises that now comprise the clusters of enterprises possessing a high degree of specialization. These produce over 200 kinds of parts for sewing machines annually. They supply both the domestic and export markets. Enterprises in clusters can make fully utilize infrastructure because of a centralized regional layout, and lower the utilization cost of infrastructures and services under the same level of supplying.

3) Market-oriented interaction. Shengze, dubbed “Kingdom of Clothes and Quilts,“ has many enterprises producing textile and silk. It is also well known as an oriental silk market. This is an example of regional branding, a result of more efficiently run and more developed enterprises that have developed a niche for their extensive and sustainable brands. Thus mention thin silk lining or materials, and Shengze town in Wujiang easily readily comes to mind. The same is true for Hengshan town, which is known for its machines for medium and heavy materials; Wujin for its lamps; and Yangzhong in Jiangsu for its low-voltage electrical equipment. The efficiency with which these manufacturers are run can be seen in reduced costs of operation and increased profit, as have been the experience of more than 200 IT companies operating on the 12 sq. km land in the developed zone of Wujiang city. This sector is also an example of a centralized cluster of enterprises that can easily obtain the latest technological information from the market and spread it efficiently through interpersonal channels. As such, enterprises could devote the a greater part of their time and resources to developing their markets ( Zhang 2005).

Order, transaction, packing, and delivery systems services are all also provided in a coordinated manner by those service enterprises. One town, for instance, has 3,500 enterprises producing wool sweaters; 600 enterprises handle the nationwide distribution; 500 others are engaged in affiliated operations; 400 enterprises produce materials; 200 are engaged in transportation; 100 enterprises repair equipment, all of them form an enterprise cluster with firm connection. Meanwhile, people, products, capital and information are all essential components of enterprises cluster, which collectively can accelerate the development of transportation, storage, telecommunications, restaurant, hotel, entertainment, education, sanitation, agency, financial insurance and real estate, etc.

5) Local government. Local government units provide an enabling environment through appropriate policies and regulations as well as vital infrastructure, which are all essential to business. Small enterprises located in the areas between Shanghai and Zhejiang enjoy the convenience of having these facilities, which allow them to do business with local and foreign enterprises. Besides, local governments arrange for enterprise visits to other places, and organize them to participate in international trade exhibits every year. These governments also support various spare part associations and service companies and provide technical and R&D services.

The findings show that certain problems persist in the SME enterprise industry. These are as follows: (a) lack of core technologies and intellectual property rights; (b) poor cooperation between foreign companies and local enterprises; (c) lack of preferential policies and advantageous labor costs that are disincentives to foreign companies, some of which have moved from China to Vietnam, India and other Southeast and South Asian countries in recent years; (d) limited access to funding; and (e) weak local government service system

6. Policy Implications

Although in general the performance of as well as constraints facing SMEs in Indonesia and China are more or less the same, due to different specific conditions of the two countries, SMEs in Indonesia may need different policy focus and development approach than their counterparts in China require.

6.1 Indonesia

management (MS/MUK), management quality systems ISO-9000, and entrepreneurship (CEFE, AMT); providing total quality control advice, technology and especially internet access (WARSI) and advisory extension workers, subsidized inputs, facilitation, setting up of Cooperatives of Small-Scale Industries (KOPINKRA) in clusters, development of infrastructure, building special small-scale industrial estates (LIK), partnership program (the Foster Parent scheme), Small Business Consultancy Clinics (KKB); establishment of the Export Support Board of Indonesia (DPE), establishment of common service facilities (UPT) in clusters, and implementation an incubator system for promoting the development of new entrepreneurs.

However, despite of all these efforts, Indonesian SMEs still face a number of problems which make them still difficult to performance as good as their larger counterparts in e.g. productivity, quality of products, and export, and to compete with imported goods. So, this study comes with the following policy implications:

1) The government indeed has a key role to play by facilitating or supporting capacity building in SMEs, especially SEs and MIEs so these enterprises can become subcontractors. The technological and managerial gaps between LEs (including foreign firms) and their SME subcontractors or, within SMEs, between MEs, on one hand, and SEs and MIEs, on the other, can be bridged through capacity building. Within SMEs, MEs are more developed and better organized or managed than SEs and MIEs. So, MEs are more ready as subcontractors than SEs and MIEs. Consequently, without government support for SE and MIEs, the subcontracting opportunities from the presence of foreign firms or provided by domestic LEs will only open to MEs.

2) As said before, the government supports for SMEs have been in various forms, ranging from a variety of special credit schemes to technical assistance and various types of training and skill upgrading. The emphasis, however, has been given too much on financial aspect; much less attention has been given on technology development, innovation capability and skills development. This paradigm should change. The focus should be on the “hardware” of the capacity building, namely skills and technology upgrading. Capital or credit is indeed important, but, it is not the hardcore of the problem facing many SMEs in Indonesia: i.e. low competitiveness due to their low technology and skill capability. They need to be trained and assisted technically, and when they already have the knowledge and they are going to buy computers or new machines or production tools, then the government can help them by providing funds through a special scheme.

3) The existing paradigm of SME development should change, from “the successful SMEs development strategy is marked by the annual increase in number of units” and “SMEs are important because they create employment”, to “the successful SMEs development strategy is marked by the annual increase in number of innovated and productive enterprises”, and “SMEs are important because they generate high value added, export, and they form domestic competitive supporting industries”.

yet so important as a source of technology development, skill upgrading or innovation activities in SMEs. So, in efforts to support capacity building in SMEs, the government should promote closer integration between R&D institutes and universities and SMEs by facilitating their effort to build strong networks. The government can encourage the involvement of R&D institutes and universities in local SMEs’ capacity building in their own district by providing a variety of facilities, ranging from a special fund scheme to finance R&D activities carry out by SMEs together with R&D institutes or universities, tax facilities and “attractive” awards to the most active R&D institutes in supporting SMEs.

5) Globalization and trade and investment liberalization should also give opportunities to local SMEs to integrate into global production network. Subcontracting is one thing to facilitate this. To develop into highly competitive supporting

industries or vendors supplying certain parts of global products is another way. For this too, the government has a very

important role to play to support this development, not only through special designed schemes but also indirectly

through creating “easy doing business” environment.

6.2 China

The government must ensure that initiatives funded with public money are responsive to business demands, address market failure, and provide added value. It must also see to it that the business support network provides the targeted service to businesses. Policymakers, both at the national and regional levels, must recognize that the process of business growth has significant policy implications for government services, and determine ways to address these implications. Aside from ensuring that employers get high-quality training from colleges and private institutions provider brokerage services on training are often key for many small firms.

The field survey in Jiangsu Government shows that the Jiangsu government has promulgated supporting policies on the development of SMEs. These mainly cover pioneering support, innovation promotion, market expansion, capital support, service guide, and rights protection. Based on this finding, then, local government units should:

1) insist on reforming the property rights system, and encourage individual and private enterprises to become share holders or owners of state-owned and collective SMEs. They must also develop joint-stock enterprises, advocate unequal stock ownership, and reform conditional joint-stock enterprises into standard company-system enterprises;

2) accelerate to encourage small enterprises to provide coordinative services for big companies, thus facilitating the pursuit of merger and acquisition activities. It should alleviate the burden of SMEs, such as some charges in reorganization of enterprises can be deducted;

cut;

4) expand financing channels. Commercial banks should set up credit organizations for SMEs. Local place should found credit guarantee funds and venture capital. High-quality assets of SMEs can come into market through equity and assets replacement, so as to realize direct capital market financing;

5) establish SME-centered technological innovation service system, information consulting service center, management consulting center, and product distribution center.

In addition, government should provide a policy framework that would serve as a guide in the setting up of industrial clusters of SMEs. Such a framework should indicate how such clusters could be formed, provide public funds for SME clusters, and set up promotional institutions that will enhance technological collaboration among SMEs, university and research institutions. The same framework should provide business support, specifically for innovation; cultivate markets; and foster human resources, among others. It should also build financing institutions for SMEs.

Specifically for SME clusters, the following countermeasures to develop such clusters should be as follows: 1) improve small town infrastructure. Improved and low-cost infrastructure, such as energy, transportation,

communications, and Internet, is vital to SME clustering;

2) small town infrastructure development could be pursued gradually but steadily while ensuring that SEs continue to produce and develop while getting the services that they need;

3) develop the industry that has competitive power. Small towns specializing in production, trade, and tourism industry should develop potentially competitive industries.

Undeveloped small towns should develop the industry using locally available resources and potential regional markets. This can be achieved through the industrial chain’s extension and new product research and development, external scale economy and healthy competition and cooperation within the SME cluster.

Implement the macroeconomic regulation and supply the local government service. The government should draw up a preferential policy for the development of SMEs, help these enterprises to choose appropriate region and adjust their development direction. The local government should help to cultivate entrepreneur spirit. The entrepreneurs of SME cluster have been regarded as important human resources in the development of the enterprises. It is necessary to create a suitable environment for the entrepreneur development and supply a preferential policy, completed law system, fair market rules and so on. The point is to build a culture of the local society to promote competition and cooperation in order to cultivate an innovative entrepreneur efficiently,

Above all, the policy for SME development should focus on financing. Following are some proposed measures toward this end:

private financing sources; 2) build policy bank of SME;

3) develop a credit guarantee system;

4) encourage utilization of foreign direct investment and expand external markets; 5) develop a second board market;

6) provide a finance and taxation support system for the promotion of SMEs’ technological innovation

References

Abdullah, Moha A., (2002), “An Overview of the Macroeconomic Contribution of Small and medium Enterprises in Malaysia,” in Charles Harvie and Boon-Chye Lee (eds.), The Role of SMEs in National Economies in East Asia. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Aharoni, Y. (1994), “How Small Firms Can Achieve Competitive Advantages in an Interdependent World”, in T. Agmon and R. Drobbnick (eds.), Small Firms in Global Competition, N.Y.: Oxford University Press.

Allal, M. (1999), Micro and Small Enterprises in Thailand: Definitions and Contributions. ILO/SEP/UNDP, Bangkok

Akrasanee, N., V. Avilasakul, and T. Chudasring (1986), “Financial Factors Relating to Small-and Medium Business Improvement in Thailand,” in James K. and N. Akrasanee, eds., Small-and Medium Business Improvement in the ASEAN Region: Financial Factors. Singapore: Institute of Southeast AsianStudies.

APEC (1999), “Women Entrepreneurs in SMEs in the APEC Region,” report to the APEC Policy-Level Group on SMEs, APEC Secretariat, Singapore.

APEC (2002), Profile of SMEs and SME Issues in APEC 1990-2000,Singapore: APEC Secretariat.

APEC (2003), “Providing Financial Support for Micro-enterprise Development.” information paper presented at the SMEs Ministerial Meeting, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 7-8 August.

Bakiewicz, Anna (2005), “Small and Medium Enterprises in Thailand. Following the Leader”, Asia & Pacific Studies, 2: 131-151.

Berry A., and D. Mazumdar (1991), “Small-Scale Industry in the Asian-Pacific Region.” Asian Pacific Economic Literature 5(2):35–67.

Berry, Albert, Edgard Rodriguez and Henry Sandee (2001), “Small and Medium Enterprise Dynamics in Indonesia”,

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 37(3): 363-84

Bijmolt, T. and P.S. Zwart (1994), “The Impact of Internal Factors on Export Success of Dutch Small and Medium-Sized Firms”, Journal of Small Business Management, 32(2).

Chiemprapha, C. (1993), “The Development of TCC and Regional Chambers in Thailand with Particular Reference to the SMEs Supporting Activities,” paper prepared for ZDH-Technonet Asia Project Review Conference, Singapore.

Chirathivat S. and Chantrasawang N. (2000), Current issues of SMEs in Thailand: The impact of the Financial Crisis and its linkages to foreign Affiliates,” Chulalongkorn Journal of Economics 12 (3): 337–361.

CIEM (2007), Vietnam economy in 2006, Finance Publishing House, Hanoi.

Cuong, Nguyen Hoa (2007), “Donor coordination in SME development in Vietnam: What has been done and how can it be strengthened” Vietnam Economic Management Review, 2, August, CIEM

GSO (2007), Yearly Statistical Book, Hanoi: General Statistical Office

Hakkala, Katarina and Ari Kokko (2007), “The state and the private sector in Vietnam”, Working paper no 236, June, Stockholm School of Economics.

Hall, Chris (1995), “APEC and SME Policy: Suggestions for an action agenda”, mimeo, University of Technology, Sydney.

Harvie, Charles and Boon-Chye Lee (2002a), “Introduction and Overview:, in Harvie, Charles and Boon-Chye Lee (eds.), The Role of SMEs in National Economies in East Asia,. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Harvie, Charles and Boon-Chye Lee (2002b), “East Asian SMEs: Contemporaty Issues and Developments – An Overview,” in Charles Harvie and Boon-Chye Lee (eds.), The Role of SMEs in National Economies in East Asia, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Harvie, C. and Boon-Chye Lee (2005), Sustaining Growth and Performance in East Asia: The Role of Small and Medium Sized enterprises, Volume III, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK.

Hill, Hal (1995), "Small-Medium Enterprises and Rapid Industrialization: the ASEAN Experience." Journal of Asian Business,11(2):1-31.

Hill, Hal (2001), “Small and Medium Enterprises”, Indonesia Asian Survey, 41(2): 248-270.

Hill, Hal (2002), “Old Policy Challenges for a New Administration: SMEs in Indonesia,” in Charles Harvie and Boon-Chye Lee (eds.), The Role of SMEs in National Economies in East Asia, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Humphrey, J. (1998), “Globalisation and supply chain networks in the auto industry: Brazil and India”, paper

presented at the International Workshop on Global Production and Local Jobs: New Perspectives on Enterprise Networks, Employment and Local Development Policy, International Institute for Labour Studies, 9-10 March, Geneva.

ILO (1993), “Development of Provincial Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Thailand”, report, International Labor Office, Bangkok.

ILO (1998), The Social Impact of the Asian Financial Crisis. ILO Regional Office, Bangkok.

ILO/UNDP (1999), “Micro and Small Enterprises Development & Poverty Alleviation in Thailand”, Project no THA/99/003, Bangkok.

Kecharananta, Nattaphan and Piyamas Kecharananta (2007), “Directions On Establishment Of Thailand’s Small And Medium Enterprises Promotion Policy And Challenges In The Future”, 2007 ABR & TLC Conference Proceedings Hawaii, USA.

King-Kauanui, Sandra, Dang Su Ngoc, Ashley-Cotleur, Catherine (2006), “Impact of Human Resource Management: SME Performance In Vietnam”. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, Available on line at URL: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3906/is_200603/ai_n17185145

Kittiprapas S., and P. McCann (1999), “Industrial Location Behavior and Regional Restructuring within the Fifth Tiger Economy: Evidence from the Thai Electronics Industry,” Applied Economics 31(1):35–49.

Lee, Boon-Chye and Wee-Liang Tam (2002), “Small and Medium Enterprises in Singapore,” in Charles Harvie and Boon-Chye Lee (eds.)., The Role of SMEs in National Economies in East Asia, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Levy, Brian, Albert Berry and Jeffrey Nugent (eds.) (1999), Fulfilling the Export Potential of Small and Medium Firms, Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Li, D. (2005), “Review of SMEs’ international cooperation in Southern SuZhou”, Business Modernization,451: 33-35.

Li, Y. (2006), “Review and experience of mode of SME clusters in Guangdong”, Business Economy,7:58-59. Liu, Q. (2001), “Review of mode of Sunan, Wenzhou, Pearl river”, China Situation and National Power,4: 23-24. Liang, G. (2007), “Policy System on promoting SME innovation and entrepreneurship in China”, Torch High

Technology Industry Development Center, Ministry of Science and Technology, China, http://www.in sme.info/documents/06_INSME2007_Liang.ppt [Accessed 27 December).

Liedholm, C. and D. C. Mead (1999), Small Enterprise and Economic Development: The Dynamic Role of Micro and Small Enterprises, London: Routledge.

Muller, E.. (1993), “The Development of FTI and Regional FTI Clubs in Thailand with Particular Reference to SMEs,” paper presented at ZDH-Technonet Asia Project Review Conference, Singapore.

Mustafa, R. and Mansor, S.A. (1999), “Malaysia’s Financial Crisis and Contraction of Human Resource: Policies and Lessons for SMIs”, paper presented at the APEC Human Resource Management Symposium on SMEs, 30-31 October, Kaoshiung.

Narain, Sailendra (2003), “Institutional Capacity-Building for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Promotion and Development”, Investment Promotion and Enterprise Development Bulletin for Asia and the Pacific, No. 2, Bangkok: UN-ESCAP

Nguyen Xuan Trinh and Le Xuan Sang (2007), Adjusting tax and subsidy policy after WTO accession: Concepts, international experiences and policy recommendations, Finance Publishing House, Hanoi, September.

Nobuaki Namiki (1988), “Export Strategy For Small Business”, Journal of Small Business Management, August.

Piper, Randy P. (1997), “The Performance Determinants of Small and Medium-Sized Manufacturing Firms”, unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of South Caroline.

RAM Consultancy Services (2005), “SME Access to Financing: Addressing the Supply Side of SME Financing”, REPSF Project No. 04/003, Final Main Report, July.

Rand, John, Finn Tarp, Nguyen Huu Dzung and Dao Quang Vinh (2002), “Documentation of the small and medium-scale enterprises survey in Vietnam for the year 2002”, DANIDA research project, Hanoi.

Rand, John and Finn Tarp (2007), Characteristics of the Vietnamese business environment: evidence from a SME survey in 2005, Component 5 – Business Sector Research, Business sector program Support, March, CIEM, DoE, ILSSA.

Regnier Philippe (2000), Small and Medium Enterprises in Distress. Thailand, the East Asian crisis and beyond.

Gower.

Régnier, Philippe (2005), “The East Asian financial crisis in Thailand: distress and resilience of local SMEs”, in Charles Harvie and Boon-Chye Lee (eds.), Sustaining Growth and Performance in East Asia, Cheltenham and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Richards, David (2002), “The Limping Tiger: Problems in Transition for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises in Vietnam,” in Charles Harvie and Boon-Chye Lee (eds.), The Role of SMEs in National Economies in East Asia,Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Rodriguez, Edgard and Albert Berry (2002), “SMEs and the New Economy: Philippine Manufacturing in the 1990s,” in Charles Harvie and Boon-Chye Lee (eds.), The Role of SMEs in National Economies in East Asia,Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Sang, Le Xuan (1997), “Developing SMEs in transition economy: The case of Vietnam”, unpublished Ph. D Thesis,

Moscow National University, Russian Federation, Moscow.

Sheng, S. and Y. Zheng (2004), Zhengjiang phenomenon: industrial clusters and regional economic development.

Beijing: Qinghua University Press.

Shi, J. (2004), Evolution and Prospective of Wenzhou Mode. Hangzhou, Zhejing Society Science Press. Sibayan, Dado (2005), “Best Practices in Microfinance in the Philippines”, Preliminary Draft, August, Manila SMIDEC (2006), SME Performance 2005, Small and Medium Industries Development Corporation, Kuala

Lumpur.

Steer, Liesbet and Markus Taussig (2002), “A Little Engine That Could….: Domestic Private Companies and Vietnam’s Pressing Need for Wage Employment”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2873, The World Bank, Washington, D. C.

UNCTAD (2003), “Improving the Competitiveness of SMEs through Enhancing Productive Capacity”, TD/B/Com.3/51/Add.1, January, Geneva.

Tambunan, Tulus T.H. (1994), The Role of Small-Scale Industries in Rural Economic Development. A Case Study in Ciomas Subdistrict, Bogor District, West Java, Indonesia, Amsterdam, Thesis Publishers.

Tambunan, Tulus T.H. (2000), Development of Small-Scale Industries during the New Order Government in Indonesia, Aldershot: Ashgate.

Tambunan, Tulus (2005), “Promoting Small and Medium Enterprises with a Clustering Approach: A Policy Experience from Indonesia”, Journal of Small BusinessManagement, 43(2): 138-154.

Tambunan, Tulus (2006), Development of Small and Medium Enterprises in Indonesia from the Asia-Pacific Perspective, Jakarta: LPFE-Usakti.

Tambunan, Tulus, Tran Tien Cuong, Le Xuan Sang, and Nguyen Kim Anh (2008), “Development of SME in ASEAN with Reference to Indonesia and Vietnam”, paper, January, Kadin Indonesia, Jakarta.

Tambunlertchai (1986), Small- and Medium—Scale Industries in Thailand and Subcontracting Arrangements. Tokyo, Institute of Developing Economies.

Tambunlertchai, S., W. Charmonman, S. Thitasajja, and S. Thammavitikul (1986), Small- and Medium- Scale Industries in Thailand and Subcontracting Arrangements. Tokyo: Institute of Developing Economies.

Taussig, Markus (2005), “Domestic Companies In Vietnam: Challenges For Development of Vietnam’s Most Important SMEs”, Policy Brief #34, September, The William Davidson Institute, at the University of Michigan, September.

Tecson, Gwendolyn R. (2001), “When the Things You Plan Need a Helping Hand: Support Environment for SMEs,” in Oscar M. Alphonso and Myrna R. Co (eds.)., Bridging the Gap – Philippine SMEs and Globalization, Manila: Small Enterprises Research and Development Foundation.

Thornburg, L. (1993), “IBM agent’s of Influence”, Human Resource Magazine, 38(2): 25-45.

Trinh, Nguyen Xuan and Le Xuan Sang (2007), Adjusting tax and subsidy policy after WTO accession: Concepts, international experiences and policy recommendations, Finance Publishing House, Hanoi.

UNESCAP (2004?), “E-business development services for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS)”, a desk study supporting the UNDP/UNESCAP project on Development of e-business development services for SMEs in selected ASEAN countries and southern China, Bangkok: UNESCAP.

Wattanapruttipaisan, Thitapha (2002a), “Promoting SME Development: Some Issues and Suggestions for Policy Consideration”, Bulletin on Asia-Pacific Perspectives: 57-67

Wattanapruttipaisan, Thitapha (2002b), “SMEs Subcontracting as Bridgehead to Competitiveness: Framework for an Assessment of Supply-Side Capabilities and Demand-Side Requirements,” Asia-Pacific Development Journal, 9, June.

Wattanapruttipaisan, Thitapha (2005), “SME Development and Internationalization in the Knowledge-Based and Innovation-Driven Global Economy: Mapping the Agenda Ahead”, paper presented at the International Expert Seminar on “Mapping Policy Experience for SMEs” Phuket, Thailand, 19-20 May.

White, Simon (1999), “Creating an Enabling Environment for Micro and Small Enterprise (MSE) Development in Thailand”, Working Paper 3, July Project ILO/UNDP: THA/99/003, Micro and Small Enterprise Development and Poverty Alleviation in Thailand, Bangkok.

Wiboonchutikula, Paitton. (1989), “Technology Transfer in Small- and Medium-Scale Industries,” paper prepared for ESCAP, Bangkok.

Wiboonchutikula, Paitton (1990), Household Demand for Goods Produced by Rural Industry. Bangkok: Thailand Development Research Institute.

Wiboonchutikula Paitton (2000), “The role of SMEs in Thailand’s Economic Development”. Chulalongkorn Journal of Economics 12 (3): 295–336.

Wiboonchutikula, Paitton (2001), Small and Medium Enterprises in Thailand: Recent Trends, June, Stock No. 37191, The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Washington, D.C.: The World Bank Wignaraja, Ganeshan (2003), “Promoting SME Exports from Developing Countries”, Competitiveness and SME

Strategy, Maxwell Stamp PLC, First Draft, 23 November. World Bank (2000), Asian Corporate Recovery, Washington, D.C.

Xiangfeng, Liu (2008),” SME Development in China: A Policy Perspective on SME Industrial Clustering”, in Hank Lim (ed.), “Asian SMEs and Globalization”, ERIA Research Project Report 2007 No. 5, Bangkok: JETRO.

Zhang, P. (2007), “Studies of SME clusters in mid-area of China”, Productivity Studies ,8:128-129.

Zhao, X. (2007), “Analysis of industrial cluster development stage in Guangdong Province”, Journal of Tianjin Manager College,9: 33-34.

Zhang, X. (2005), “Outward investment of industrial clusters: new way of SME international operation in China”,