Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:45

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Transitions in Classroom Technology: Instructor

Implementation of Classroom Management

Software

David Ackerman, Christina Chung & Jerry Chih-Yuan Sun

To cite this article: David Ackerman, Christina Chung & Jerry Chih-Yuan Sun (2014) Transitions in Classroom Technology: Instructor Implementation of Classroom Management Software, Journal of Education for Business, 89:6, 317-323, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.903889 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2014.903889

Published online: 03 Sep 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 337

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Transitions in Classroom Technology: Instructor

Implementation of Classroom Management Software

David Ackerman

California State University Northridge, Northridge, California, USA

Christina Chung

Ramapo College of New Jersey, Mahwah, New Jersey, USA

Jerry Chih-Yuan Sun

National Chiao Tung University, Hsinchu, Taiwan

The authors look at how business instructor needs are fulfilled by classroom management software (CMS), such as Moodle, and why instructors are sometimes slow to implement it. Instructors at different universities provided both qualitative and quantitative responses regarding their use of CMS. The results indicate that the top needs fulfilled by CMS are distribution of materials and communication with students. They also suggest that ease of use and usefulness of CMS are related to attitudes toward it, but that confusion in its use is not. Lastly, lack of clarity and time were the primary concerns of those who had not yet adopted CMS. Implications are discussed.

Keywords: classroom technology, CMS, instructors, technology adoption

In higher education, using course management systems (CMSs) has become popular, with researchers focusing on the benefits they afford teaching and learning. However, except for a few studies such as Harrington et al. (2006), there is lack of investigation into why or when instructors should use a CMS. The purposes of this study are therefore to understand why instructors adopt CMS to the degree that they do, what instructional needs it fulfills, and why some instructors do not use it. These findings will hopefully be helpful to business schools in providing the resources and help in more effective implementation of CMS.

There are two important sets of issues regarding CMS. The first is whether instructors need to adopt CMS for their classes. Business instructors may already be quite effective teachers without the new instructional technology. They may question what benefits they and their students will reap by using a new technology. There are also research findings indicating that learning technology may not be the most important factor impacting learning outcomes (Young,

Klemz, & Murphy, 2003). Also, procrastination that depends on a variety of internal and external factors is not uncommon in academia (Ackerman & Gross, 2007). Instructors may think that a particular instructional technol-ogy sounds like a good idea but then put it off until some indefinite time in the future. Getting started on the adoption of a CMS is a key to success, and, in a survey taken in both 1998 and 2000, Lincoln (2001) found that overall there was an increase in technology usage in instruction over time.

The second issue is the nature of the benefits of class-room management technology to instructors. Classclass-room management software varies in the options it offers, but in general it must benefit student learning first and secondarily facilitate faculty management of the classroom. Here we look at both of these issues and explore the linkages between them.

There are a number of benefits of classroom manage-ment software to both instructors and students. Instructors can create content online, combine it with any number of audio and visual content, and deliver it to students. They may also more easily monitor student progress in class since assignments can be uploaded and quizzes given online. Classroom management software also provides a

Correspondence should be addressed to David Ackerman, California State University Northridge, Department of Marketing, 18111 Nordhoff Street, Northridge, CA 91330-8377, USA. E-mail: david.s.ackerman@csun.edu ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online

DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.903889

common ground for communication in cyberspace, making it an important tool for online classrooms. Information and files can be transferred effortlessly between the instructor and unlimited numbers of students. In addition, using a CMS integrated with multimedia helps students increase their academic performance and enhances interest in the course (Walsh, Sun, & Riconscente, 2011). Last, students themselves can communicate within groups and via discus-sion boards themselves. Study guides provided by instruc-tors and perhaps shared commonly among students are another important benefit of CMSs (Lewis et al., 2005).

Studies have suggested that students do find the online learning components provided by most classroom software packages to be effective for their overall learning (Clarke, Flaherty, & Mottner, 1999) and student engagement (Sun & Rueda, 2012). Moreover, this positive impact does not seem to vary by the learning style of the student (Young et al., 2003). Despite these potential benefits, not all is opti-mism when it comes to the use of classroom management systems.

There are differences in perceptions between faculty and students. First, students seem to adapt to classroom technol-ogy faster than instructors, although this may be a function of the comparatively greater responsibility and amount of work that instructors need to do to utilize such software. A survey at one university found that students perceived class-room management software to be easier to use than faculty did, and that a higher percentage of students than faculty learned the use of the software on their own (Payette & Gupta, 2009).

The major course management systems are Blackboard, WebCT, and Moodle, although there are many other choices available. Despite familiarity with Blackboard or WebCT, adoption of Moodle usage has grown since its introduction in 2003 to approximately 3,000,000 courses in 209 countries as of October 2009. Moodle is an open source learning man-agement system. This means it is available free of charge to anyone under the terms of the General Public License, that is, there is no licensing fee. Some have suggested that stu-dent motivation is a key factor in the success of Moodle in the classroom and that they found it easier to use (Beatty & Ulasewicz, 2006). Students tend to like Moodle better than faculty (Payette & Gupta, 2009), but this may be a function of greater faculty familiarity with other classroom manage-ment software. So, if classroom managemanage-ment software pro-vides so many benefits as an instruction technology, why do instructors procrastinate in implementing this technology? Are there good reasons not to use it at all?

WHY DO INSTRUCTORS USE OR NOT USE CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT SOFTWARE?

It is likely that many instructors intend to fully implement classroom management software, but procrastinate in doing

so for a variety of reasons. Most people procrastinate some of the time depending on the circumstances. Distractions of vari-ous sorts lead faculty to procrastinate on projects that they have started as more immediate tasks come up (Ackerman & Gross, 2007). Fear is also a factor. Fear of implementing classroom management software may delay instructors from starting to learn it. In fact a big complaint faculty members have regarding instruction technology is reliability (Butler & Sellborn, 2002). What happens if the technology breaks down when faculty really need it? The more user-friendly functions and technical support there is for particular software, the more these fears may be allayed. That distractions delay the completing of projects means that the actual length of time required to implement a classroom management software sys-tem may also impact its adoption by instructors.

A couple of months or even a couple of weeks is a long time in the busy schedule of faculty, many of whom may have more immediate issues to deal with. This is supported by general findings about the adoption of academic technol-ogy which suggest that time is an important variable that influences whether a particular technology is implemented (Liu, Maddux, & Johnson, 2004). Those universities that pro-vide time off or perhaps reduced units to learn new classroom software may see increased rates of adoption. Administration certainly can have a role in fostering the creativity that is nec-essary for faculty adoption of classroom innovations (Celsi & Wolfinbarger, 2002).

Despite the difficulty of starting to use a CMS for an instructor, there are many advantages to enhance teaching effectiveness. Brown and Johnson (2007) discussed several advantages of using a CMS. Among these, consistency in delivery, performance tracking, and interactive functions can be applied to an academic environment. Given the pre-vious literature review, here we focused on three research questions:

Research Question 1(RQ1): Why do faculty procrastinate

in using a CMS? Are there differences between pro-crastination in using a CMS and propro-crastination in using other technologies?

RQ2:How do faculty feel about CMSs in terms of the diffi-culty, usefulness, and favorability of using them?

RQ3:Are there relationships between the perceptions (diffi-culty, usefulness, and favorability) and the effective-ness of using a CMS?

In the present study we investigated faculty perceptions of adopting and using a CMS in their teaching and how their perceptions impact on their effective use of the CMS.

METHOD

We administered a survey designed to measure perceptions of CMSs among higher education instructors. Data were

318 D. ACKERMAN ET AL

collected primarily from the members of a marketing aca-demic association using a convenience sampling method. The sample consists of instructors that were teaching at a college or university. A web-survey invitation was sent to those in the sample frame, asking them to participate in a self-administered survey. The sample frame is appropriate and reliable since it consists of faculty members who teach at a school that provides a course management system for the faculty. Among 152 participants, eight respondents answered that they had never used a CMS. The other 144 stated that they had used such software. After deleting incomplete surveys, 126 were suitable for analysis. The participants were 55% male and 45% female. They had teaching experience ranging from 6 months to 38 years with a mean of 15 years.

The measurement items can be found in the Appendix. First, respondents were asked if they had ever used a CMS as a screening question. If they had never used a CMS, they were asked what they think about web-based CMSs. Queries concerning interest, confidence and desire to use a CMS, whether or not it is important to use a CMS, as well as the mental efforts employed in and the effectiveness of using CMSs were incorporated.

The nonuser part of the survey was based on the survey on instructor procrastination found in Ackerman and Gross (2007) modified to measure instructor adoption of class-room management software technology. There were 10 var-iables each measured by three associated individual items. Questions consisted of a 7-point Likert-type scale with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly

agree). There were measures of fear or worry about

adopt-ing a CMS, norms or expectations that projects are started early, competing demands from other project deadlines, incentives and rewards for not delaying the adoption of a CMS and a measure of interdependence between adoption of a CMS and other work.

There were two measures of appeal of CMSs, a measure of the faculty member’s interest in adopting CMS and a measure of skill variety required for the adoption of a CMS. There were three constructs measuring the perceived difficulty of adopting a CMS. There was a measure of how time-consuming the respondent anticipated adopting a CMS would be, a measure of how difficult respondents believed that adopting a CMS would be and a measure of how clear they were on how to adopt a CMS. Finally, respondents were asked about their own general propensity to procrastinate.

For those who had used a CMS, several close-ended questions were asked concerning Confusion in using the CMS, ease of use, and functional usefulness in resolving classroom needs. For all questions, the response options consisted of a 7-point Likert-type scale with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). There were items for measuring the usefulness of CMSs (MD4.42,SDD1.57; Cronbach’saD.95), items related

to confusion encountered in using a CMS (MD3.04,SDD

1.74; Cronbach’saD.85), and items measuring how easy

it was to use a CMS in instruction (MD4.83,SDD1.71; Cronbach’saD.80).

In addition, an open-ended question was asked, “What classroom needs are fulfilled by your use of a CMS?

RESULTS

Nonadopters of CMS

Those faculty members who had never used a CMS revealed that they were interested in and saw the benefits of using a CMS, but were not clear about how to use it and felt that it may be difficult or time-consuming to imple-ment. On the one hand, most respondents felt there would be benefits, such as management of paperwork, providing timely feedback and communication with students, provid-ing a sense of satisfaction from masterprovid-ing technology, and helping integrate information technology.

On the other hand, they were not fully clear about how to get started on implementing the software and were putting if off. Most respondents agreed with the following state-ments: (a) It is not clear how I could use a CMS with my classes, (b) I don’t fully understand how a CMS could be successfully used in my class, and (c) I don’t know exactly what is necessary to successfully use a CMS in my class. The respondents also agreed with these statements: (a) using a CMS requires using a variety of skills, (b) I need to use a lot of different skills to use a CMS, and (c) I have to approach learning a CMS using many different types of skills. In addition, respondents are under time constraints that cause delays in learning to use a CMS. Most respond-ents agreed with the statemrespond-ents: (a) I have many other proj-ects to complete before starting to use a CMS, (b) many other projects have to be finished before I start to learn to use a CMS, and (c) I have other projects with deadlines before I start to learn to use a CMS.

Given the small sample size, statistical comparison between the two groups, users and non-users, is not possi-ble. Yet, it is interesting to note that procrastination as a personality characteristic does not seem to be higher for the non-user than for the user group, even though both had highly favorable attitudes toward CMSs. The mean for the user group was 3.46 whereas that for the nonuser group was 1.93.

Needs Fulfilled by CMSs

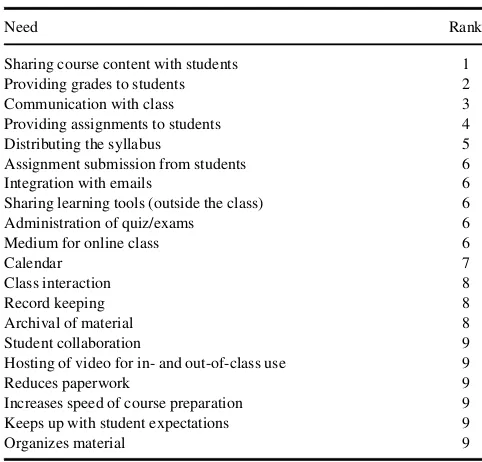

For the open-ended question, “What classroom needs are fulfilled by your use of a CMS?” the respondents provided detailed information as displayed in Table 1. Sharing of course content with students was the need most frequently mentioned by the instructors, who said they shared course

lecture slides, readings, and supplemental materials with students. The second most frequently mentioned need was grading. The CMS functioned as a grade book and a tool to let large numbers of students know about their progress in the course without the time involved in face-to-face interac-tion. Communication with the class was the third most fre-quently mentioned need fulfilled by the CMSs. Annou-ncements, schedule changes and reminders were easily facilitated via the CMSs. The next frequently mentioned function was the handing out and receipt of assignments. The instructors mentioned that a CMS was an efficient way of giving out and receiving assignments from large num-bers of students. Less frequently mentioned were student interaction and online exams/quizzes. Perhaps these require more technological expertise to administer, and in the case of student interaction, do not directly impact on the instructor’s teaching experience.

Instructors’ Use of Moodle

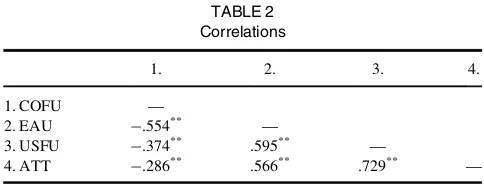

Several close-ended questions using a 7-point Likert-type scale were created to examine ease of use (EAU), confusion in the use of a CMS (COFU), usefulness (USFU), and atti-tudes toward CMSs (ATT). The four constructs include 24 items, EAU (4), COFU (7), USFU (5), and ATT (5). Cronbach’s alpha was used for testing the internal consis-tency of the measurement and increasing the precision of the measurement by precluding the obstructive items from the instruments. The alpha values for EAU, COFU, USFU, and ATT were .88, .91, .95, and .75, respectively. These values indicate that strong associations and implied meas-urements were consistent.

Correlation analysis was conducted to evaluate the strength of relationships among the three constructs. As a result, there were significant relationships between the three constructs, ease of use, confusion in the use of a CMS, and usefulness.

Then, a multiple regression analysis was conducted to evaluate how COFU, EAU, and USFU are related to ATT. The predictors were COFU, EAU, and USFU, while the cri-terion variable was ATT. The result indicated that the linear combination of COFU, EAU, and USFU was significantly related to ATT,F(3, 105) D48.13, p < .01. The results

indicate that approximately 58% of the variance of the effectiveness of using CMS was accounted for by the com-bination of these three constructs. The results also indicate that COFU was not significant, but EAU and USFU were significant. Thus, usefulness and ease of use are strong pre-dictors of attitudes toward CMS.

Multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to evaluate the relationships among the three independent var-iables. As shown in Figure 1, result indicated that COFU was significant (p <.01) and had a negative relationship

(b D –.374) with USFU. Also, COFU was significant (p<.01) and had a negative relationship (bD–.554) with

EAU. In the relationship between USFU and EAU, there was a significant and positive relationship (bD.595). The results explain that ease of use and usefulness increase posi-tive attitudes toward CMS. There was no direct relationship between confusion in using a CMS and ATT, but it indi-rectly affects ATT by increasing usefulness and ease of use.

DISCUSSION

Analysis of Instructor Use of Moodle

The results show that ease of use and usefulness are signifi-cantly related to attitude toward CMS, but not confusion in using it. It is possible that some aspects of CMSs are easy to use, but that frustration with completing a particular task or perhaps bugs in the system software can lead to confu-sion in use. As both impact instructors’ perceived useful-ness of CMS, it may be necessary for departments or

TABLE 1

Needs Fulfilled by Classroom Management Software

Need Rank

Sharing course content with students 1

Providing grades to students 2

Communication with class 3

Providing assignments to students 4

Distributing the syllabus 5

Assignment submission from students 6

Integration with emails 6

Sharing learning tools (outside the class) 6

Administration of quiz/exams 6

Medium for online class 6

Calendar 7

Class interaction 8

Record keeping 8

Archival of material 8

Student collaboration 9

Hosting of video for in- and out-of-class use 9

Reduces paperwork 9

Increases speed of course preparation 9

Keeps up with student expectations 9

Organizes material 9

FIGURE 1 Summary of regression analysis.

320 D. ACKERMAN ET AL

school administrators to consider two issues in order to ensure the most effective use of their classroom manage-ment technology systems.

First, despite the fact that some CMSs such as Moodle may be easy to start to use, for faculty to figure out how it can perform functions that meet their classroom needs, they may just require time to adjust. This notion is supported by the finding that the instructors’ perceived usefulness of CMSs was positively related to the number of years they had been teaching, and this despite the fact that new instructors tend to be more technologically savvy. Newer instructors may find the software easier to use, but also find it more confusing to set it up and apply it to their busy teaching schedules.

Perhaps instructors could receive written instruction or seminars on using a new CMS, but confusion in the use of the CMS comes in applying it to particular problems and issues during the course of a semester. There may just be a learning curve so that the longer a particular CMS is in place, the better instructors will be at applying it to their courses. This would also apply to new uses for a CMS such as online or distance learning. Instructors would need time to apply the different facets and features of the CMS that would be applicable to these courses.

Second, to reduce the amount of downtime and perhaps lost information from bugs in the system, technical assis-tance needs to be available. Troubleshooting is the issue. This may take the form of paid personnel available to answer questions or deal with issues. This type of assistance may also take the form of discussion boards where other fac-ulty can trade tips or war stories of workarounds to problems that have arisen in the use of the CMS in the classroom.

The results also indicate that the confusion in using CMS for an instructor is not related to its perceived usefulness or ease of use. This suggests that there are unique aspects of CMSs that are confusing, unrelated to the ease with which an instructor can start using a classroom management soft-ware package. There are aspects of CMSs that go beyond the software learning curve to the way the class is con-ducted. Online chat rooms and group cooperation, asyn-chronous discussion, and fast distribution of grades to students are just a few of the aspects of CMSs that involve changing the way instructors manage a class. Instructors

can feel confusion from these changes in the class enabled by the CMS, and not from ease or difficulty of the use of the software itself.

Discussion forums might be helpful for instructors to trade tips and suggestions about how to implement the improvements in the classroom allowed by the CMS. Requiring students to monitor incoming information during the week or grading discussion is something that instructors more experienced with CMSs in the classroom could help with. Time and experience with adoption of a CMS will in time reduce this problem. New instructors who start off teaching with a CMS will expect the benefits provided by the system, and those who are learning to work with it will get used to it.

Another area where confusion can be an issue is that var-ious CMSs continue to be introduced and sometimes a fac-ulty member will have to learn a new CMS system. For example, the transition to a new CMS such as Moodle might be challenging with instructors confused about fea-tures and protocols that are different from those which they encountered previously. In support of this contention is that fewer participants found the more difficult features such as online exams and quizzes and interactive features helpful. This suggests that giving technical support in these areas to instructors who are already using a CMS for their courses would be helpful in making them more useful.

Analysis of Needs Fulfilled by CMSs

There are clearly some basic needs related to facilitation of communication with the class and the distribution of mate-rials that are high on the list of most instructors. Routine tasks, such as distribution of course materials, feedback, and receipt of student assignments are time-consuming tasks for instructors. Anything in classroom management software that makes these routine class tasks easier will be looked upon favorably and adopted more quickly.

In developing the use of a CMS, departments and admin-istrators could focus on developing efficient protocols in the handling of these basic tasks. For example, a basic intro-duction to a particular CMS could highlight tips for dissem-inating classroom material or feedback to students. Similarly, there could be a guide or instruction on com-monly made mistakes in receiving student assignments on the system.

Also important, though not quite as much as the basic needs mentioned previously, are the needs revolving around communication with the class. Instructors have other means of communicating. There is also email, direct contact, the occasional phone call, and other forms of social media. CMS is a powerful means not just of instructor-class com-munication, but also of communication within the class itself. The questions for instructors are whether or not and the extent to which they and their students will use it. Given

TABLE 2

Note: COFU: Confusion in the use of CMS; EAU: Ease of use; USFU: Usefulness; ATT: Attitude toward CMS.

**

pD.01 (two-tailed).

inertia and the fact that instructors may already be familiar with other means of communication, it is not surprising that communication via CMS does not rate as highly as the basic needs mentioned above. On the one hand, instructors may over time become used to communicating with their classes via a particular CMS, replacing old patterns of com-munication. On the other hand, students are there for a lim-ited period of time and will clearly have more experience with other forms of communication such as social media. It is not yet clear whether experience communicating with, for example, Facebook will transfer easily to the habit of communicating with their instructors and classmates on the class Moodle page.

Farthest down the list of needs fulfilled by CMS are those that relate to the customization of courses such as vid-eos, facilitating collaboration and online class needs. These are areas in which the CMS functions to transform a class beyond what could normally be done in a semester by an instructor. Completely online classes and hybrid classes extend the reach of a university to non-traditional and working students, but customization can impact the tradi-tional student in a face-to-face classroom as well. It is very time-consuming to customize the learning experience in the classroom to the needs of different students, but with CMS it is possible to cluster course materials into types of inter-ests and needs for use by different segments of the student population in any particular course. For example, in a mar-keting research class, multi-media, in-depth study material and even examination of the material could be provided for students who are interested in specific techniques such as qualitative research, surveys or experiments. Chat rooms broken down by category could provide support and guid-ance for students who are working on projects in each of these areas.

Nonadopters of CMSs

It is more surprising that a large percentage of nonusers of CMS also had highly favorable attitudes toward CMS. Given that everyone finds CMSs to be appealing to some degree, what leads to the difference in their usage? Though no definitive answers can be drawn from this study, two factors stood out. First was the lack of clarity about how to implement CMSs. The instructors knew the value of CMSs and, as pointed out, had favorable attitudes toward them, but they were not clear about how to implement one for their course and so procrastinated. It would be helpful for technology personnel to walk instructors through the pro-cess of implementing a course on a CMS and to be avail-able to troubleshoot throughout the semester.

Time available was another important factor mentioned in not adopting a CMS. Making a major change in

instruction technology, such as adopting a CMS, often takes a considerable amount of time. Instructors may see others using a CMS seemingly effortlessly to save time and effort, but procrastinate in doing so themselves because of the per-ceived upfront investment of time. Perhaps departments could have a CMS already set up and linked to instructors’ courses in order to get them started. If it is already set up, that would reduce the concern or inertia of instructors hav-ing to take the first step. Also, given the earlier findhav-ings, perhaps first implementation of a CMS could focus on satis-fying more basic classroom needs such as distribution of class materials and receipt of student assignments. That would reduce the time required while providing significant benefits to the instructor.

REFERENCES

Ackerman, D., & Gross, B. (2007). I can start that JME manuscript next week, can’t I? The task characteristics behind why faculty procrastinate.

Journal of Marketing Education,29, 97–110.

Beatty, B., & Ulasewicz, C. (2006). Online teaching and learning in transi-tion: Faculty perspectives on moving from Blackboard to the Moodle Learning Management System.TechTrends,50, 36–45.

Butler, D. L., & Sellborn, M. (2002). Barriers to adopting technology for teaching and learning.Educause Quarterly,25, 22–28.

Celsi, R. L., & Wolfinbarger, M. (2002). Discontinuous classroom innova-tion: Waves of change for marketing education.Journal of Marketing Education,24, 64–72.

Clarke, I. III, Flaherty, T. B., & Mottner, S. (1999). Student perceptions of educational technology tools. Journal of Marketing Education, 23, 69–77.

Lewis, B. A., MacEntee, V. M., DeLaCruz, S., Englander, C., Jeffrey, T., Takach, E.,. . .Woodall, J. (2005). Learning management systems com-parison.Proceedings of the 2005 Informing Science and IT Education Joint Conference, 17–29.

Lincoln, D. (2001). Marketing educator internet adoption in 1998 versus 2000: Significant progress and remaining obstacles.Journal of Market-ing Education,23, 103–116.

Liu, L. P., Maddux, C., & Johnson, L. (2004). Computer attitude and achievement: Is time an intermediate variable?Journal of Technology and Teacher Education,12, 593–607.

Payette, D. L., & Gupta, R. (2009). Transitioning from Blackboard to Moodle–course management software: Faculty and student opinions.

American Journal of Business Education,2, 67–73.

Sun, J. C.-Y., & Rueda, R. (2012). Situational interest, computer self-efficacy and self-regulation: Their impact on student engagement in dis-tance education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43, 191–204. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01157.x

Walsh, J. P., Sun, J. C.-Y., & Riconscente, M. (2011). Online teaching tool simplifies faculty use of multimedia and improves student interest and knowledge in science. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 10, 298–308. doi:10.1187/cbe.11-03-0031

Young, M. R., Klemz, B. R., & Murphy, J. W. (2003). Enhancing learning outcomes: The effects of instructional technology, learning styles, instructional methods and student behavior.Journal of Marketing Edu-cation,25, 130–142.

322 D. ACKERMAN ET AL

APPENDIX Non-Users

Fear

1. I am worried I won’t to do a good job with a CMS. 2. I’ll perform poorly with a CMS.

3. I’m not confident I could do a good job with a CMS.

Norms

4. In my department, most faculty members use a CMS. 5. It is expected in my department that faculty use a CMS. 6. Most faculty use a CMS for classes.

Interest

7. I am interested in a CMS. 8. CMS holds my interest.

9. I could really get involved with a CMS.

Scope of Task (Time Consuming)

10. A CMS requires a lot of time.

11. Using a CMS will occupy a lot of my time. 12. Using a CMS will be time consuming.

Difficulty

13. Using a CMS will be tough in my classes.

14. It will be really difficult to use a CMS for my classes. 15. I know that using a CMS will not be easy in my classes.

Clarity

16. It is not clear how I could use a CMS with my classes. 17. I don’t fully understand how a CMS could be successfully

used in my classes.

18. I don’t know exactly what is necessary to successfully use a CMS in my classes.

Deadline Pressure

19. I have many other projects to complete before starting to use a CMS.

20. Many other projects have to be finished before I start to learn a CMS

21. I have other projects with deadlines before I start to learn a CMS.

Skill Variety

22. Using a CMS requires using a variety of skills. 23. I need to use a lot of different skills to use a CMS.

24. I have to approach learning a CMS using many different types of skills.

Incentives and Rewards

25. There are incentives for getting an early start on learning a CMS.

26. There is a real benefit to starting to learn a CMS soon. 27. There are rewards for getting an early start on learning a CMS.

Interdependence

28. Doing other projects I desire to work on depends on first learn-ing a CMS.

29. I have to learn a CMS before I can do other projects I want to do.

30. I need to learn a CMS before I can start other work I want to do.

Self-Reported Propensity to Procrastinate

1. I delay starting projects. 2. I procrastinate on projects

3. I wait until the last minute to work on projects.

Users

Which CMS(s) have you used? (Please mark as many as needed.) (1) Blackboard (2) WebCT (3) Moodle (4) other system ___________________

How long have you used course management systems? (1) Less than 1 year (2) 1–3 years (3) More than 3 years Currently, what course management system do you use?

(1) Moodle (2) Blackboard (3) WebCT (4) None (5) other ___________

Confusion in using a CMS

1. I often become confused when I use a CMS 2. I make errors frequently when using a CMS. 3. Interacting with a CMS is often frustrating.

4. I need to consult the user manual often when using a CMS.

5. Interacting with a CMS requires a lot of my mental effort. 6. A CMS is rigid and inflexible to interact with.

7. A CMS often behaves in unexpected ways.

Ease of Use

1. Interaction with a CMS is easy for me to understand. 2. It is easy for me to remember how to perform tasks using a

CMS.

3. A CMS provides helpful guidance in performing tasks. 4. Overall, I find a CMS easy to use.

Functional Usefulness

1. A CMS enables me to accomplish tasks more quickly. 2. Using a CMS allows me to accomplish more work than would

otherwise be possible.

3. Using a CMS reduces the time I spend on unproductive activities.

4. Using a CMS increases my productivity. 5. Using a CMS makes it easier to do my job.

Favorable Attitude toward CMS

1. I am likely to recommend a CMS to my colleagues. 2. I strongly feel that faculty should use a CMS. 3. Using a CMS is favorable.

4. Using a CMS is wise.

5. Learning to use a CMS is time consuming.