Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 18 January 2016, At: 19:57

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

SURVEY OF RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Ross H. McLeod

To cite this article: Ross H. McLeod (2008) SURVEY OF RECENT DEVELOPMENTS, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 44:2, 183-208, DOI: 10.1080/00074910802168980

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910802168980

Published online: 31 Jul 2008.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 120

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/08/020183-26 © 2008 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074910802168980

SURVEY OF RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Ross H. McLeod

Australian National University

SUMMARY

The 10th anniversary of Soeharto’s resignation was coloured by disappointment

with the slowness of reform, and with the government’s reluctance to confront blatant religious intolerance. Nevertheless, economic growth is strong and invest-ment spending buoyant. Infl ation has risen well above target, suggesting that a

more effective approach to monetary policy is needed. The recent surge in global rice prices coincided with bountiful domestic harvests, putting the government under pressure to restrict rice exports rather than imports as it has in recent years. However, restricting exports has been recognised as a ‘starve thy neighbour pol-icy’, and the ASEAN trade ministers have jointly agreed ‘to continue fair trade practices and to achieve an orderly regional rice trade’.

The government has at last increased domestic fuel prices signifi cantly,

mind-ful of the waste of valuable resources and the inequity involved in keeping such prices constant in the face of world price increases. It will implement a cash trans-fer program to compensate the poor for the resulting increase in living costs.

The Ministry of Finance is leading reform of the central government bureaucracy. Its most fundamental initiatives are in human resource management, where it is attempting to match remuneration to skill requirements and responsibilities, and to align the pay structure more closely with that in the private sector—with pay rates rising much more rapidly than hitherto as levels of responsibility increase. It is also encouraging competition to fi ll vacancies by advertising them internally,

rather than continuing to rely on promotion by seniority. At local government level, a small number of heads of government have gained a reputation as pioneers of reform. Two interviewed for this survey are exemplars of precisely what it was hoped would result from bringing government closer to the people through decen-tralisation, and from the switch to direct election of heads of local government. Both have considerable experience in the private sector, and their success seems related to their more entrepreneurial (as distinct from bureaucratic) way of thinking.

‘Good corporate governance’ has now become the mantra for state-owned enterprises (SOEs). It is recognised that this depends heavily on choosing the right people to manage each fi rm and to oversee it on behalf of its owner. Accordingly,

almost all directors and commissioners of the 11 SOEs indirectly studied here have been replaced in recent months, and there is now a willingness to appoint professionals from private companies and from academia in order to gain access to needed skills. In addition, the initial selection of candidates has been shifted outside the bureaucracy to professional recruitment agencies.

SOCIO-POLITICAL CURRENTS

May 21st 2008 marked the 10th anniversary of Soeharto’s resignation from the

presi-dency after over three decades in offi ce. There has been much discussion within the

media and academia about what has happened since then. Although the economy is in quite good shape, casual observation reveals a rather surprising mood of dis-appointment in some quarters with the extent of reform achieved in the last decade, and of pessimism about the future. Consistent with this, 40% of respondents in a recent survey rated conditions now worse or much worse than those 10 years ago, while only 33% rated them better or much better (LSI 2008).

The public has been disquieted by large increases in food prices over the last year, but of greatest concern in recent months has been the rapid escalation of world oil prices, and its implications for continuation of domestic fuel and energy subsidies. There is also much cynicism and dismay about the fact that the reformasi period has seen no end to the endemic corruption of the Soeharto era, but rather a fl ourishing

of corrupt behaviour at the local government level. It may be that public perception is being driven by the Corruption Eradication Commission’s vigorous campaign of prosecutions against corrupt offi cials: it is surely diffi cult for the public to believe

that reformasi is having a substantial impact on corruption when daily confronted with new cases. However, the volume of such prosecutions is an indicator not so much of increasing corruption as of an increased determination to act against it.

Another matter of growing concern is religious strife—particularly in relation to the tiny Ahmadiyah sect of Islam, which is regarded as heretical by mainstream Islamic groups, and has been hounded by the Defenders of Islam Front (FPI). Alarmed at the government’s failure to protect Ahmadiyah, a large number of Indo-nesia’s intelligentsia highlighted their concerns in prominent press advertisements in mid-May, and invited the public to a mass gathering in support of human rights and religious tolerance on 1 June (NAFRF 2008). Some of those who attended were attacked by members of the FPI while police looked on. The next day the president urged the police force to do its job, after which some of those responsible for the attack were arrested. But within days the government had issued a joint ministerial decree which, although not banning Ahmadiyah as its opponents wanted, called on its followers, in effect, to fall into line with mainstream Islam (JP, 10/6/2008), seem-ingly in confl ict with the Constitution’s guarantee of religious freedom.1

MACROECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS

The Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs, Boediono, was appointed gover-nor of the central bank on 22 May, following parliament’s rejection of the president’s two previous nominees (Kong and Ramayandi 2008: 31). Almost four weeks passed before it was announced that Boediono’s former position was to be fi lled by Sri

Mul-yani Indrawati, who would also continue to serve as fi nance minister. This came as

little surprise, not least because of the latter’s masterful performance in coordinat-ing a phalanx of cabinet ministers at a press conference on 23 May to announce the government’s long-awaited decision on domestic fuel prices (see below).

1 Article 29 (2) of the Constitution states that ‘The state guarantees the freedom of all mem-bers of the population to embrace their respective religions and to worship in accordance with their religions and beliefs’.

Growth

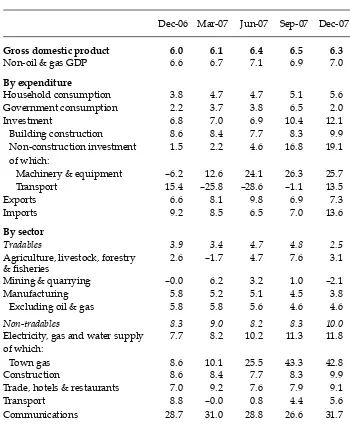

The national income accounts for the March quarter of 2008 show that the econ-omy has settled down to a fairly steady annual growth rate in the range 6.0 –6.5% (table 1). Non-oil and gas growth has been consistently a little higher—on average, around 6.9%, not too far behind the average growth rate of around 7.4% under Soeharto. The investment data have been very promising for some time now, with double-digit growth rates recorded during the last three quarters. Growth of investment in construction, by far the largest component, typically has been well

TABLE 1 Components of GDP Growth (2000 prices; % p.a. year on year)

Dec-06 Mar-07 Jun-07 Sep-07 Dec-07 Mar-08

Gross domestic product 6.0 6.1 6.4 6.5 6.3 6.3

Non-oil & gas GDP 6.6 6.7 7.1 6.9 7.0 6.8

By expenditure

Household consumption 3.8 4.7 4.7 5.1 5.6 5.5 Government consumption 2.2 3.7 3.8 6.5 2.0 3.6

Investment 6.8 7.0 6.9 10.4 12.1 13.3

Building construction 8.6 8.4 7.7 8.3 9.9 8.3 Non-construction investment 1.5 2.2 4.6 16.8 19.1 31.2 of which:

Machinery & equipment –6.2 12.6 24.1 26.3 25.7 31.4 Transport 15.4 –25.8 –28.6 –1.1 13.5 50.1

Exports 6.6 8.1 9.8 6.9 7.3 15.0

Imports 9.2 8.5 6.5 7.0 13.6 16.8

By sector

Tradables 3.9 3.4 4.7 4.8 2.5 3.6

Agriculture, livestock, forestry & fi sheries

2.6 –1.7 4.7 7.6 3.1 6.0

Mining & quarrying –0.0 6.2 3.2 1.0 –2.1 –2.3

Manufacturing 5.8 5.2 5.1 4.5 3.8 4.3

Excluding oil & gas 5.8 5.8 5.6 4.6 4.6 4.6

Non-tradables 8.3 9.0 8.2 8.3 10.0 9.0

Electricity, gas and water supply 7.7 8.2 10.2 11.3 11.8 12.1 of which:

Town gas 8.6 10.1 25.5 43.3 42.8 37.2

Construction 8.6 8.4 7.7 8.3 9.9 8.3

Trade, hotels & restaurants 7.0 9.2 7.6 7.9 9.1 7.2

Transport 8.8 –0.0 0.8 4.4 5.6 9.8

Communications 28.7 31.0 28.8 26.6 31.7 30.0 Financial, rental & business

services

6.5 8.1 7.6 7.6 8.6 8.3

Other services 6.2 7.0 7.0 5.2 7.2 5.7

Source: CEIC Asia Database.

above 8%. Less obviously, non-construction investment growth has been extra-ordinarily rapid in recent times. Investment in machinery and equipment has been growing for the last year at rates of 24–31%, while investment in transport surged to 50% (year on year) in the March quarter. Exports also grew very rapidly in that quarter, in line with earlier analyses that emphasised the bright side of Indonesia’s relatively small exposure to the slowing US economy. Import growth continued to accelerate from the already high level achieved in the December quarter.

The tendency of non-tradables growth to exceed that of tradables is still clearly evident (although the dividing line between these sectors is often quite fuzzy). Continued relatively slow growth of the agriculture, livestock, forestry and fi sheries sector (at an average of about 3.5% for the last several years) is an

expected consequence of structural change in the economy away from more traditional pursuits.2 By contrast, declining output in mining and quarrying

appears to refl ect reluctance to invest in these activities given the continued

uncertainties posed by the legal environment (Grigg 2008), whereas the disap-pointingly slow growth of manufacturing has much to do with labour mar-ket regulations that weigh heavily on labour-intensive manufacturing activity (Suryahadi et al. 2003). Within non-tradables it is interesting to note the rapid growth of the utilities sector (electricity, gas and water supply), within which the output of town gas has been expanding at astonishingly high rates of around 40% annually.

The communications sector, dominated by mobile telephone services, contin-ues its outstandingly rapid expansion, refl ecting immense benefi ts to consumers

and, presumably, very high profi ts within the industry. The down-side of this

appears to be an increasing tendency for domestic business interests to employ political infl uence to try to wrest parts of this industry from the grip of foreign

shareholders who have proven so successful in driving its growth. The previ-ous survey reported on a legally baseless decision by the Business Competition Supervisory Commission (KPPU) intended to force a foreign (indirect) share-holder to divest its ownership of one or the other of two large mobile phone companies (Kong and Ramayandi 2008: 25–8). Meanwhile, a new regulation introduced by the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology seeks to restrict investment in the telecommunications towers that comprise the mobile phone transmission network to domestic investors.3 This appears to

con-travene the recently enacted Law 25/2007 on investment, which explicitly

speci-fi es the fi elds of investment that are closed to foreign fi rms, and stipulates that

closure of additional fi elds to foreign investment requires a presidential decree

to that effect (art. 12(3)).

Infl ation: time for a new approach to monetary policy?

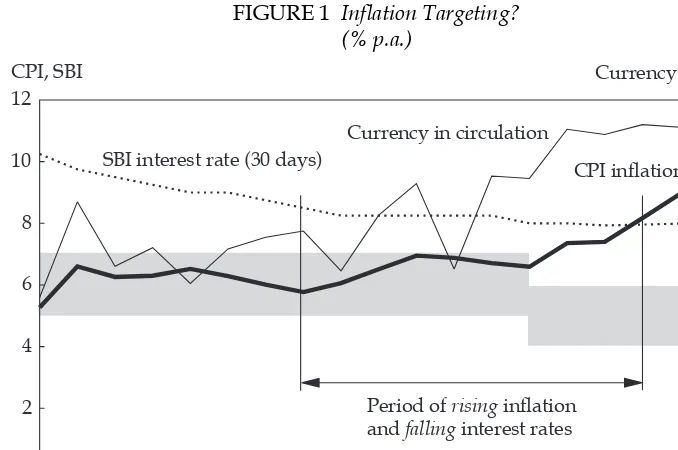

The central bank’s target for infl ation in 2008 is 4–6%. The last time Indonesia saw

CPI infl ation within this range was in June 2007, when the rate fell briefl y to slightly

below 6%. Since then there has been a steady and increasingly rapid upward trend,

2 Crop output is greatly infl uenced by climatic conditions, so the relatively high growth

rate in Q1 2008 (table 1) does not mean much on its own. 3 Art. 5(1) of Ministerial Decree No. 02/Per/M.Kominfo/3/2008.

with infl ation reaching 10.4% in May 2008 (fi gure 1)—even though Bank Indonesia

(BI) had reduced its target infl ation range to 4–6% in 2008 from 5–7% in 2007.

BI says that it follows an ‘infl ation targeting’ approach to monetary policy,

given that its legal responsibility is to achieve and maintain stability of the value of the currency (BI, no date). There is certainly an infl ation target, but in terms of

actual policy actions and outcomes this ‘single objective’ means little. Elsewhere, BI notes its concern also to safeguard the continuity of economic growth (e.g. BI 2008: 4). At the very least, therefore, there are in fact two objectives—although, in contrast with infl ation, BI does not specify any target for growth. Whether it is

wise for BI to concern itself with growth rather than simply focusing on infl ation

is moot. One virtue of having only an infl ation objective is that the central bank

can then be held accountable for failure to achieve it. With two objectives, this can readily be excused by reference to the supposed need to sacrifi ce infl ation to

sup-port economic growth.

Under a pure infl ation targeting regime, any sustained tendency of infl ation to

move beyond the upper bound of the target range should be met by a tightening of monetary policy. But as can be seen from fi gure 1, there was no such policy response

to the acceleration of infl ation between July and September 2007—or in early 2008,

even though by this time infl ation was well outside the now lower target range.

Indeed, BI’s policy interest rate continued to be pushed lower for a further eight months from the infl ation low point in June 2007 before being nudged upward by a

mere 0.25% in April 2008; by then the infl ation rate was already above 8% and still

rising. Moreover, infl ation as measured by the wholesale price index (not shown

here) rose to exceed 25% in April 2008.

FIGURE 1 Infl ation Targeting? (% p.a.)

a Shaded areas indicate infl ation target ranges for 2007 and 2008; CPI = consumer price index; SBI = Sertifi kat Bank Indonesia (Bank Indonesia Certifi cates), whose rates refl ect offi cial interest rate policy.

Source: CEIC Asia Database.

It was widely expected that BI would respond to the large jump in domestic fuel prices in late May 2008 (see below) by increasing its policy rate by perhaps 50 basis points (0.5%). In the event, the increase was only 25 basis points (to 8.5%), and the immediate reaction among observers was that this would not

suf-fi ce to subdue the infl ationary impact. More to the point, the fundamental

ques-tion is: what should be done with interest rates if infl ation is to be pushed below

the 6% level? The disappointing infl ation outcomes of the last several months,

like those in 2001–02 (Alisjahbana and Manning 2002: 282–3) and 2005–06 (Man-ning and Roesad 2006: 149), suggest that the answer is unknown—and probably unknowable, given our limited understanding of the dynamic relationships involved.

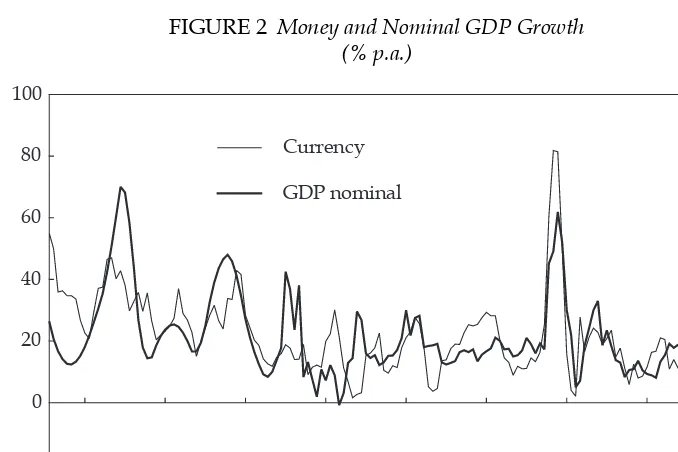

Is there a more effective way of going about infl ation targeting? One

possibil-ity would be to set the policy rate based on a target trajectory for growth of the money supply that is consistent with the desired evolution of the rate of infl ation.

For example, if BI wants to reduce infl ation to, say, 5% by the end of 2008, it could

manipulate the interest rate over time so as to reduce the rate of money supply growth steadily from its current high level of around 28% until it is consistent with this infl ation rate. There is nothing new in this. Recall Boediono’s comment

about his experience as minister early in the Habibie presidency: ‘… it was not diffi cult to convince [Habibie] that a really tight monetary policy was necessary

to break the prevailing infl ationary spiral’ (Boediono 2002: 388). It did, at the same

time GDP growth was recovering from the depths of the crisis.

Estimating the end-of-year target money supply growth rate is straight forward, given the clear medium- to long-term relationship between base money, prices and real output. Figure 2 shows how closely the rates of nominal GDP and money growth have moved over almost the last four decades, so much so that the ratio of

FIGURE 2 Money and Nominal GDP Growth (% p.a.)

Mar–72 Mar–81 Mar–90 Mar–99 Mar–08

-20 0 20 40 60 80 100

Currency

GDP nominal

Source: CEIC Asia Database; BPS-Statistics Indonesia; BI, Indonesia Financial Statistics (various issues).

currency in circulation to nominal GDP is much the same now as it was in 1970.4

Since the growth rate of nominal GDP approximately equals the rate of infl ation

plus the rate of real output growth, and since output is likely to grow at about 6% in the near future, achieving 5% infl ation simply requires annual base money

growth to be reduced from 28% to around 11%. In the short run the interest rate on Bank Indonesia Certifi cates (SBIs)—or whatever other policy instrument is

cho-sen—will need to be increased somewhat in order that a suffi cient quantity can be

sold to bring about the desired reductions in money growth.5

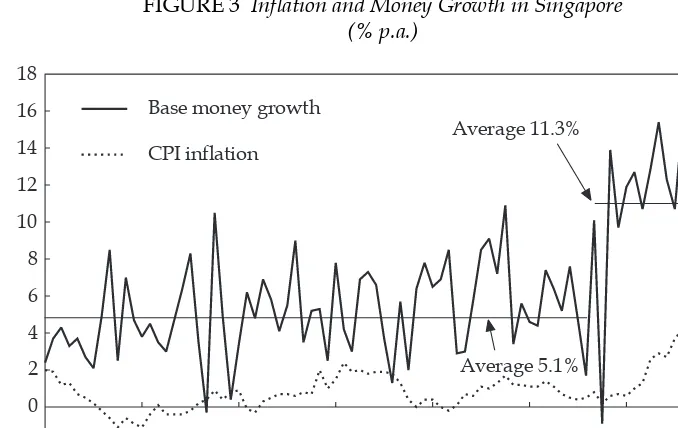

Strikingly strong support for the idea of controlling base money growth in order to meet an infl ation target can be derived from the somewhat surprising

experi-ence of Singapore. Until very recently Singapore has been a paragon of price sta-bility, with an average annual rate of CPI infl ation of just 0.7% during 2001–06

(fi gure 3). However, there has been a dramatic acceleration since the end of 2006,

such that by April 2008 it stood at 7.6%. An explanation is readily available in terms of a dramatic change in the outcomes of monetary policy. Although money growth clearly has been somewhat volatile during the period under review, it was slow on average through late 2006, at just 5.1%. Since then, however, the average growth rate has more than doubled, to 11.3%. In rough terms, an increase of 6% in money growth has resulted in a 7% increase in infl ation.

4 Currency in circulation comprises the bulk of base money. The demand for base money is distorted by regulatory changes in banks’ required reserve ratios, so it is more meaning-ful to focus on currency.

5 Sales of SBIs reduce base money by exactly the same amount, so all that is needed is to accept bids in auctions of SBIs up to the yield level that results in the desired quantity be-ing issued.

FIGURE 3 Infl ation and Money Growth in Singapore (% p.a.)

Apr–01-2 Apr–02 Apr–03 Apr–04 Apr–05 Apr–06 Apr–07 Apr–08

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18

Base money growth

CPI inflation

Average 11.3%

Average 5.1%

Source: CEIC Asia Database.

Financial markets

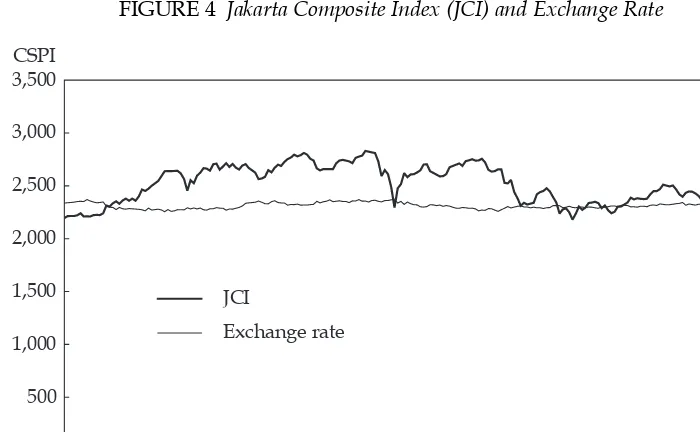

The accelerating upward trend of prices of goods and services has not been observed in either the capital market or the market for foreign exchange (fi gure 4).

On the contrary, the exchange rate has averaged about Rp 9,250/$ since August 2007, with no discernible trend, while the stock exchange composite index relin-quished almost all of the gains of September and October 2007 during the fi rst

half of March 2008, with little change subsequently.

RICE

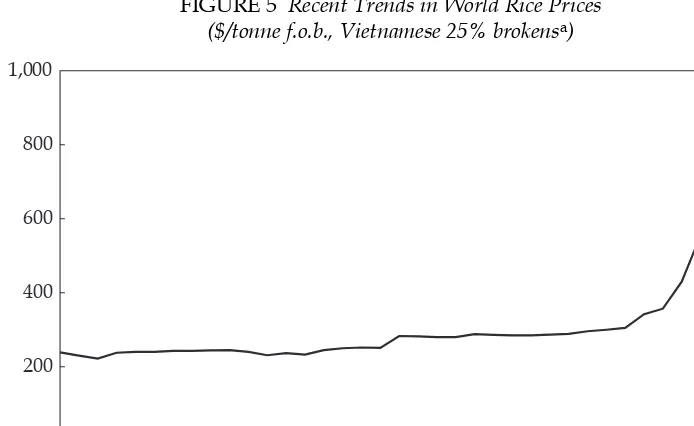

The annual rate of increase in domestic rice prices, which had been of the order of 15% in the latter half of 2007, declined quite rapidly at the end of the year and for the fi rst few months of 2008 as a consequence of very successful harvests.

Nevertheless, as is clear from work by Dawe (2008) and Simatupang and Tim-mer (2008) published in this journal’s recent special issue on rice policy (BIES 44 (1), April 2008), the long-term trend in Indonesia is for rice production to grow more slowly than the demand for rice. Indonesian self-suffi ciency in rice could

be achieved only by heavy subsidisation—or by closing the border to imports of rice and thus artifi cially increasing the incentive to produce it. This has been

offi cial policy in recent years. The rationale for the policy—that this helps the

poor—is now well understood to be misconceived (Warr 2005; McCulloch 2008). The majority of Indonesia’s poor are net rice consumers rather than net produc-ers, and so are harmed by the higher prices that result from import restrictions.

Ironically, this point was clearly demonstrated by the surge in global rice prices in late 2007 and early 2008, which happened to coincide with the bounti-ful domestic harvest (box 1 and fi gure 5). Suddenly, the government found itself

FIGURE 4 Jakarta Composite Index (JCI) and Exchange Rate

31-Aug-20070 5-Nov-2007 14-Jan-2008 20-Mar-2008 28-May-2008

500 1,000 1,500 2,000 2,500 3,000 3,500

0 2,000 4,000 6,000 8,000 10,000 12,000 14,000

JCI

Exchange rate

CSPI Rp/$

Source: Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX); Pacifi c Exchange Rate Service.

under pressure to restrict rice exports rather than rice imports, because exports would have raised domestic rice prices at the expense of consumers. Yet it was precisely the desire to raise domestic prices that had driven the previous policy of restricting rice imports. High rice prices were now correctly and widely per-ceived as harmful to net consumers: the burden to middle-class net consumers

BOX 1 CAN INDONESIA STILL TRUSTTHE WORLD RICE MARKET?

Recent events on the world rice market have called into question my recent observa-tion (Dawe 2008: 130) that Indonesia can trust the world rice market to supply its needs when domestic production falls below consumption requirements, as will usu-ally be the case. Prices more than doubled in just three months, from $357 per tonne in January 2008 to $923 per tonne in May—partly in response to exporting nations withholding supplies in order to hold down domestic prices, and to fears that others would follow suit. While some might argue that such events prove the need for self-suffi ciency, that is unlikely to be the optimal policy solution.

First, there is no policy that completely eliminates all risk in the rice economy. The world market was quite stable for many years before the current crisis, and autarky has very substantial costs and risks of its own. Self-suffi ciency induced by import

restrictions would raise domestic rice prices and increase poverty. In addition, prices will be very unstable in the face of domestic production fl uctuations if imports are not

an option; as an example, Indonesian domestic rice prices increased by 33% in real terms between May 2005 and May 2006 after import restrictions were imposed.

Second, while fortunate not to be in the market in early 2008, Indonesia could have afforded imports even at the very high prices observed at that time, just as the Philip-pines was able to afford them. Note also that the April 2008 peak price was 64% lower than the peak reached in April 1974 in infl ation-adjusted terms, and lower than the

average real price on the world market from 1950 to 1981.

Third, it is important to understand why prices surged. Per capita Asian rice pro-duction has been roughly constant during the past few years, and there has been no sudden increase in Asians’ rice consumption. Further, trade volumes were almost 20% higher in the fi rst few months of 2008 than in the same period in 2007, so there was no

shortage of supplies on the international market. In the absence of important develop-ments in the ‘real’ rice economy, it seems that a combination of fear, opportunism and panic on the part of traders, consumers, farmers and governments (the latter in the form of export restrictions and aggressive importing) led to a sudden surge in specu-lative demand, driving prices to high levels. Because the most important actors in the world market are governments, not private traders, the current crisis is an example of government failure, not market failure.

It would clearly be in Indonesia’s interest if exporters did not impose ad hoc trade restrictions, and importing nations might want to bring such considerations into inter-national trade negotiations at the World Trade Organization. But for exporters to agree to such conditions, importing nations will also need to agree to import in times of low prices. Thus, a free trade area for rice within ASEAN or ASEAN+3a (and

possi-bly including the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation) would provide increased stability for all Asian countries. Not many would question such a policy prescription when it comes to rice trade between districts, and there is no fundamental difference when trade between nations is involved.

David Dawe Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

a ASEAN plus China, Japan and South Korea.

now became large enough to generate protestation on a scale the government found hard to ignore.

The upheaval in the global rice market in early 2008 is reminiscent of the self-defeating policies implemented by many countries during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Faced with growing unemployment, countries typically deval-ued their currencies and imposed import restrictions so as to switch aggregate demand to domestic producers. These policies effectively attempted to export unemployment to trading partners, and so became known as ‘beggar thy neigh-bour policies’. Likewise in 2008, Egypt and India, both large rice exporting countries, faced with spiralling rice prices, introduced ‘starve thy neighbour policies’: they restricted rice exports to put downward pressure on domestic rice prices, sending global rice prices even higher for rice importing countries.

Fortunately this process has been recognised for what it is. Thus the ASEAN trade ministers held a meeting in Bali in early May at which they jointly agreed ‘to continue fair trade practices and to achieve an orderly regional rice trade’ (Bisnis Indonesia, 5/5/2008). Particularly noteworthy was the fact that the world’s largest exporter, Thailand, committed itself not to prohibit or limit rice exports—whereas earlier its prime minister had announced a goal of creating a rice exporter car-tel (Bowring 2008). The outcome of the ministerial meeting seems to suggest a regional consensus that interruptions to normal rice trading arrangements are not in any country’s long-term interests. Since Indonesia is usually a rice importer, this agreement should strengthen the hand of policy makers in resisting calls for protection for rice farmers against imports when domestic production again, inevitably, falls short of consumption. This is likely to occur next in the latter part of 2008.

FIGURE 5 Recent Trends in World Rice Prices ($/tonne f.o.b., Vietnamese 25% brokensa)

May–050 Nov–05 May–06 Nov–06 May–07 Nov–07 May–08

200 400 600 800 1,000

a f.o.b. = free on board; 25% brokens = rice with 25% broken grains.

Source: Food and Agriculture Organization.

ENERGY SUBSIDIES

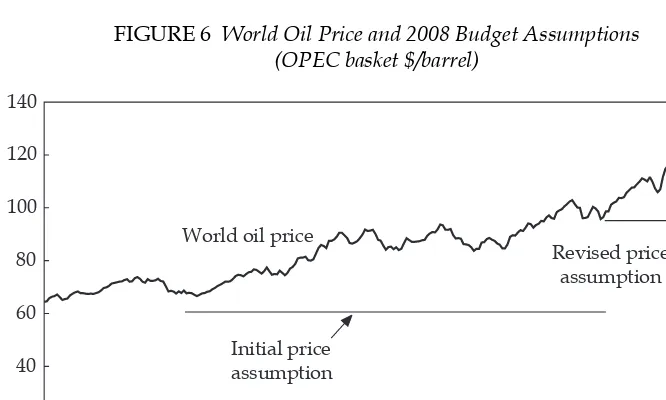

Unquestionably the major recent economic and political event was the gov-ernment’s decision to increase domestic fuel prices by an average of 28.7% on 24 May (table 2). This was precipitated by the astonishing rise in the world price of oil over the preceding 12 months. The initial draft budget for 2008 had assumed an oil price of $60 per barrel (Kong and Ramayandi 2008: 12–13) but, by the time the parliament enacted the budget in November, the actual price was closer to $90. The government was slow to respond, waiting until early April to raise the oil price assumption to $95. Although this was realistic in terms of spot prices at the time, within just two months, oil had risen further to around $130 per barrel (fi gure 6).

With the government committed to holding domestic prices constant, large increases in the world price necessitate correspondingly large increases in outlays

TABLE 2 Changes to Domestic Fuel Prices

Fuel Old New Increase Industrya

(Rp/litre) (%) (Rp/litre)

Gasoline (premium) 4,500 6,000 33.3 8,613

Diesel 4,300 5,500 27.9 10,816

Kerosene 2,000 2,500 25.0 11,036

Average 28.7

a New prices for (unsubsidised) industrial use were announced on 1 June 2008, and are shown here for

comparative purposes (Bisnis Indonesia, 6/6/2008).

FIGURE 6 World Oil Price and 2008 Budget Assumptions (OPEC basket $/barrel)

6-Jun-2007 31-Aug-2007 27-Nov-2007 25-Feb-2008 22-May-2008

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140

Initial price assumption

Revised price assumption World oil price

Source: OPEC, <http://www.opec.org/home/basket.aspx>.

on subsidies for consumption of fuel and electricity. The impact on the defi cit is

small by comparison, however, since the government derives additional revenue from the increased value of Indonesia’s oil and gas exports. The real underlying concerns—well understood by many of the key policy makers and their advis-ers—are the enormous waste of valuable resources and the inequity implied by these subsidies. Even with oil at only $100 per barrel the subsidies were estimated at about $26 billion (Kong and Ramayandi 2008: 16, box 1), with this amount becoming much larger as the price surged to $130 and beyond. Moreover, the inci-dence of the subsidies is highly regressive. Wealthy people consume much more energy, directly and indirectly, than the poor: the Ministry of Finance estimates that the richest 40% of the population account for some 66% of the subsidies, while the poorest 40% receive only 18% (MOF 2008a).

Eventually the president was persuaded of the need to raise domestic prices. The government was well aware of the political sensitivity of the issue, however, and thus announced its intention to adjust fuel prices well in advance, without specify-ing either the date on which this would occur or the extent of the increases—in short, giving the public time to adjust psychologically to the idea. In the event, although there were protests for several days by certain NGOs and student groups, the gen-eral public seemed resigned to the reality that fuel prices were bound to rise. There were also protests by minibus drivers in response to delays by local government authorities in adjusting public transport fares, which unreasonably and unnecessar-ily reduced their earnings signifi cantly for a period of about two weeks.

Although fuel subsidies are clearly inequitable, individuals are concerned about the direct impact on themselves of fuel price increases rather than the distribu-tional implications. This impact is signifi cant for the poor, and so the government

also announced its intention to implement a cash transfer program to compensate them for the higher costs of public transport and of the kerosene used for cook-ing and lightcook-ing. These transfers were set at Rp 100,000 per month per family for some 19.1 million families designated as poor, and would continue through to the end of 2009. A similar program had been implemented following the very large fuel price increases in October 2005. The SMERU Research Institute found that, while the Post Offi ce was an effective mechanism for delivery of these transfers,

the program was rather poorly targeted: 45% of the available funds went to non-poor households, while 45% of non-poor households did not receive any transfers (SMERU Research Institute 2006). For its part, the government claims that the rate of mistargeting in 2005 was only 10%, and that it expects an improved outcome this time (Bisnis Indonesia, 12/06/2008). In any case, the cash transfer program could hardly be less equitable than untargeted subsidies for fuel consumption. This point seemed lost on the protesters, however.

Indonesia is not the only country that has faced politically diffi cult choices as

a consequence of surging world oil prices. Malaysia, for example, reduced its fuel subsidies shortly after Indonesia did. In neither case did the government raise domestic prices to world prices, as has been done in many other countries, including Singapore.6 There is much to be said for such a policy, which in fact was

6 Malaysia’s announced increases were considerably larger than Indonesia’s, and the government has foreshadowed its intention to implement further increases until domestic prices match world prices.

foreshadowed on the previous occasion when domestic prices were adjusted in Indonesia (Presidential Decree 55/2005, art. 9), but has never been implemented (except that fuels for industrial use are not subsidised). World prices are changing constantly, leading to unanticipated changes in the cost of subsidies if domestic prices are fi xed. This can be highly disturbing to budget outcomes, and can result

in signifi cantly reduced spending in other, more desirable areas. For all his faults,

former President Soeharto ensured that a very large proportion of the oil boom revenues of the 1970s and early 1980s was reinvested in infrastructure, education and health care; even the considerable windfall gains channelled to his cronies were largely re-invested in private sector activity. Much of the explanation for remarkable economic progress—including poverty reduction—during the Soe-harto era can be found in these policies. By contrast, the current president has not perceived the new oil boom of the last few years as a welcome opportunity to increase spending on badly needed infrastructure, or to bring about improve-ments in the quality and quantity of education and health services. Rather, it is seen and portrayed as a burden to be borne.

The government also announced its intention to introduce an alternative means of targeting fuel subsidies more carefully, by restricting the purchase of subsidised fuel to owners of motor cycles and operators of public transport vehicles, given that poorer people tend to make greater use of public transport and to own motor cycles rather than automobiles. Under this policy, fuel for motor cars would also continue to be subsidised for an indefi nite period, though at a lower rate. The new scheme

was to rely on an electronic ‘smart card’, which would allow some maximum amount of subsidised fuel to be purchased within any given period.7 Purchases

beyond this threshold would have to be at unsubsidised, or less heavily subsidised, prices, which implied that the government would need to introduce a three-tier pricing system involving further increases in the prices paid by non-target groups.

The deadline for introduction of the new system was to be the beginning of 2009, but this seemed unrealistic. Apart from the need to identify the tens of millions eligible to participate, and to produce and allocate the new cards to them, retailers of these fuels would need to be provided with electronic card reading equipment and to be connected to a central database by a nationwide telecommunications network. In view of the evident enormity of these tasks, only Java and Bali were to be covered in the fi rst phase, implying the need for highly problematical

differ-ent pricing structures in differdiffer-ent parts of the country. In the evdiffer-ent, however, the smart card plan was abandoned (Dow Jones International News, 18/6/2008). The government blamed the high cost of the scheme, but it is hard to imagine that this would have outweighed the potentially large savings in subsidies. It seems more likely that the crucial factor was concern about middle-class sensitivity to the fur-ther implied increases in prices.

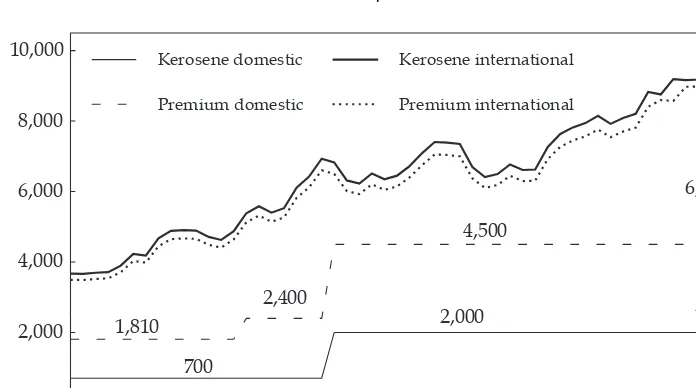

Notwithstanding the new increases, subsidised domestic fuel prices remain far below world levels. A large part of total subsidies is for the consumption of kero-sene, the domestic price of which is far lower relative to the world price than is the

7 ‘Pemerintah akan menerapkan sistem distribusi BBM jenis tertentu secara tertutup [Government to apply closed system of distribution for certain kinds of fuels]’, Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, 30/1/2008, accessed 18 June 2008 at <http://www.esdm. go.id/berita/migas/40-migas/1157>.

case for gasoline (fi gure 7) and diesel fuel. The government is intending to phase

out this subsidy, not merely by raising the price of kerosene, but also by restricting its supply, while simultaneously encouraging households to switch to natural gas by providing free gas storage bottles. Since this is a massive task it will take some time to complete; in the meantime it is planned to issue such households with ‘control cards’, which will allow them to purchase subsidised kerosene in limited amounts. At world prices, natural gas is a cheaper form of fuel for these purposes than kerosene, and Indonesia’s relatively high consumption of kerosene refl ects

the high levels of subsidy in the past. Thus the shift to using natural gas at world parity prices will involve some additional burden to households, but this also does not yet seem to have been noticed by the media.

PUBLIC SECTOR REFORM

Indonesia’s economic performance in recent times has been impressive, notwith-standing the severe challenges posed by rising global food and energy prices and by all too frequent natural disasters. But there remains much room for improve-ment in the climate in which the private sector is required to operate: Indonesia ranks 123rd of 178 countries on ease of doing business in the World Bank’s Doing

Business 2008 report, and 143rd of 180 countries in Transparency International’s

Corruption Perceptions Index for 2007, for example. Expectations as to how quickly the public sector could be reformed after Soeharto left offi ce may well

have been unrealistic, but that does not diminish the urgency of achieving more in this fi eld. The remainder of this survey focuses on three parts of the public sector,

FIGURE 7 Domestic and International Fuel Pricesa

(Rp/litre)

Jan–04 Jul–04 Jan–05 Jul–05 Jan–06 Jul–06 Jan–07 Jul–07 Jan–08 Jul–08 0

2,000 4,000 6,000 8,000

10,000 Kerosene domestic

Premium domestic

Kerosene international

Premium international

1,810

2,400

4,500

6,000

2,000

700

2,500

a Diesel is omitted for clarity.

Source: Ministry of Finance.

widely defi ned, in which particularly notable efforts are being made to introduce

the kinds of reforms on which further improvement in Indonesia’s performance depends: the Ministry of Finance (MOF), two local governments in Central Java, and a group of companies under the Ministry for State-owned Enterprises. These specifi c entities were chosen for study because they are at the forefront of reform,

rather than being representative of the public sector in general. Moreover, the emphasis is on describing some of the main thrusts of reform; for the most part it is too early to provide an analysis of their impact, which, in any case, is beyond the scope of this survey.

Ministry of Finance

The fi rst steps towards reform within the Ministry of Finance occurred under

the government of Megawati Soekarnoputri and her fi nance minister,

Boedi-ono. The process began with the establishment of a Large Taxpayers Offi ce as

an attempt to increase the level of income tax revenues, widely regarded as well below potential. Further impetus for reform was generated by the enactment of three laws in the following two years: Law 17/2003 on State Finances; Law 1/2004 on the State Treasury; and Law 15/2004 on Auditing of State Finances. These laws heralded a change from past practices, demanding a much higher level of transparency and accountability within government and, in particular, within the fi nance ministry.

The Medium Term National Development Plan for 2004–09 included a plan for reform of the bureaucracy, calling for the application of ‘good governance’ principles in general—and, in particular, improved supervision and accountabil-ity of civil servants; restructuring of management and institutions; better man-agement of human resources; and the improvement of services provided to the public. When the present Minister of Finance, Sri Mulyani Indrawati, took up her position in December 2005, she decided to push forward vigorously with reform in her own ministry, clearly signalling her intentions by replacing the heads of the ‘notoriously corrupt’ tax and customs and excise directorates general (DGs) within four months of taking offi ce (Witular 2006).

The Ministry of Finance has a large number of offi ces spread throughout the

archipelago, and employs around 62,000 civil servants. Under the current minis-ter, it is serving as a pilot project to lead reform of the bureaucracy, rather than waiting for centrally driven whole-of-government reforms that seem unlikely to materialise in the near future. Broadly stated, the aim of bureaucratic reform is to create a civil service whose personnel are ‘clean’ (non-corrupt), professional and accountable, and which is effi cient and effective in carrying out its functions. Thus

it is recognised that reform does not merely entail bringing corruption under con-trol (seemingly the president’s principal focus), but also involves improving the capacity of the bureaucracy to design and implement government policies.

There are two main components of this reform effort, one concerned with the way the ministry goes about its business, and the other with the way its human resources are managed (MOF 2008b).

To make itself more effective in carrying out its functions the ministry has changed its organisational structure, splitting some DGs into two or more, and combining other organisational units into a single DG. It has also defi ned the

functions of some of the DGs more precisely than before. At the same time it has

focused on all of the repetitive tasks undertaken throughout the ministry, with a view to redesigning the processes involved (‘standard operating procedures’) to make them simpler and more transparent—and to backing this up by setting standard times for completion of these tasks.

While important in themselves, these kinds of measures are much less funda-mental than changes to the way human resources are managed, precisely because it is the job of individuals to decide upon, for example, the best way to organise the ministry and design its operational processes. The changes to human resource management currently being implemented are far reaching, refl ecting the need

to clear away the accumulation of policies and practices that hinder efforts to optimise performance of the bureaucracy. The changes include preparing detailed job descriptions for each position; grading each position on the basis of its scope, the competencies required and the risks that need to be managed by incumbents; determining a structure of remuneration that refl ects this grading; identifying

training needs by comparing individuals’ skill sets with the skills required in the positions they occupy or are likely to occupy in the future; quantifying surpluses and defi cits of skills within the existing workforce; and developing a system for

monitoring performance and rewarding or penalising individuals accordingly. The ministry has found that there is a surplus of lower-level employees with only general skills, while at higher levels the need for offi cials with professional

skills (particularly those acquired through post-graduate education) often far exceeds their availability. This refl ects the failure in the past to relate the level and

types of recruitment to actual manpower needs, and to provide suffi cient

oppor-tunities for ministry personnel to undertake further training. A particular prob-lem (apparently common to the entire bureaucracy) is that both recruitment and training were cut back heavily in the late 1990s as a result of budgetary diffi culties

following the 1997–98 fi nancial crisis. Ten years later this is causing considerable

problems, to which the ministry is responding by sending large numbers of its staff to study for higher degrees, both domestically and overseas. It has also indi-cated that it will establish additional functional positions for staff with specifi c

professional skills, and that it may introduce crash training courses to meet its workforce needs—particularly for accountancy staff (Bisnis Indonesia, 6/7/2007, 21/9/2007, 24/9/2007). By contrast, there appears to be little the ministry can do about excessive staff numbers at the lower levels, even though the civil service ministry is well aware of the problem.8

The fi nance ministry has compiled a set of guidelines for improving discipline

among MOF offi cials, together with a code of ethics for all Echelon I (top-level

management) offi cials, and has also established a Code of Ethics Council. More

important in practice, perhaps, is the decision to improve the structure of remu-neration and to tie remuremu-neration to the work done. Henceforth, performance is to be ‘valued’—that is, remunerated—on the basis of the job gradings mentioned above. The greater the skill requirements and responsibilities of the position, the higher the level of remuneration.

As a fi rst step in determining a new pay structure, a multinational consulting fi rm specialising in monitoring private sector remuneration of managerial and

8 ‘Menpan: Indonesia kelebihan PNS [Minister for the Civil Service: Indonesia has an ex-cess of civil servants]’, Tempo Interaktif, 15/5/2007.

professional employees was commissioned to provide a comparison with offi cial

levels of remuneration in the ministry.9 Consistent with other studies, its research

found that civil service pay at lower levels in the hierarchy was quite comparable with that in the private sector, but that the rate of increase in remuneration with increasing levels of responsibility was much slower. In other words, formal remu-neration of offi cials at the highest levels of the bureaucracy was far below that of

top executives within the private sector—the implication being that this was detri-mental to the goal of optimising the performance of such offi cials, and thus the

min-istry itself. Accordingly, the minmin-istry has brought its pattern of remuneration more closely into line with that in the private sector, through the mechanism of a special allowance for fi nance ministry offi cials known as tunjangan khusus pembina keuangan

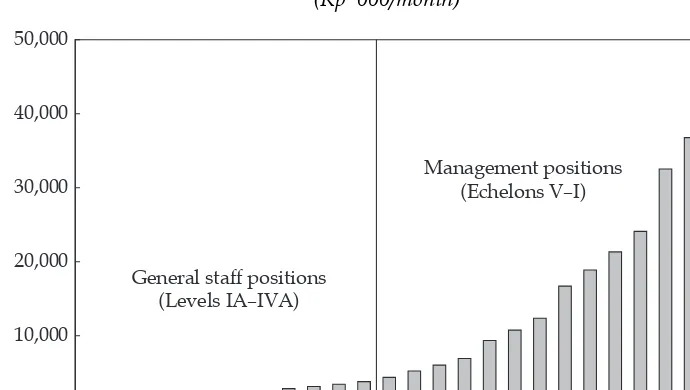

negara (TKPKN) (fi gure 8), intended to replace all existing allowances.

The ministry needed to be given special approval to raise remuneration levels for its employees signifi cantly. There have been reports that remuneration has been

increased four-fold (Sheridan 2008), but this means little because, as fi gure 8 shows,

the increase has not been applied evenly across all levels of the hierarchy; indeed, to

9 It is necessary, albeit tedious, to refer to ‘pay/remuneration’ rather than ‘salaries’, be-cause total remuneration consists of basic salary plus allowances, and the latter far exceed the former—especially at the upper levels of the hierarchy.

FIGURE 8 Ministry of Finance Special (TKPKN) Allowancesa

(Rp ‘000/month)

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27

0 10,000 20,000 30,000 40,000 50,000

General staff positions (Levels IA–IVA)

Management positions (Echelons V–I)

a See text for an explanation of ‘TKPKN’. These allowances represent an increasing proportion of total

remuneration as responsibility level increases, reaching well over 75% at higher management levels. It has been reported that offi cials working in designated ‘modern offi ces’ in the Directorate General of Taxation also received an ‘additional allowance’, tunjangan kerja tambahan (TKT), with an ‘additional special allowance’, tunjangan tambahan khusus (TTK), for account representative staff (Bisnis Indonesia,

6/7/2007).

Source: Finance Minister Decree No. 289/KMK.01/02007, available at <http://depkeu.multiply.com/ journal/item/1/Tunjangan_Depkeu_naik_Rp43_triliun>.

have done so would have been needlessly expensive, and would not have had much impact on incentives for good performance. In keeping with the heavy emphasis on differentiating between positions and tying remuneration to their grading, much higher proportionate increases have been implemented at higher levels. Thus Ech-elon I offi cials at the highest grading (level 27) should now receive a special

allow-ance (and total remuneration) of around $60,000 annually.10

The new pay scale appears to leave high-level offi cials still well behind their

private sector peers, however. Directors of large companies appear to earn far higher sums: of the order of $350,000 p.a. in PT Telkom, for example (Trianto 2008). A private sector human resources training manager with a university degree and 5–6 years experience could expect to earn Rp 10–15 million per month according to Kelly Services (2007). This would correspond to a ministry position grading of about 18, for which the special allowance, basic salary and other allowances would total about Rp 14 million, yet promotion to this level would typically take about twice as long: 10–11 years. Nevertheless, this still amounts to a dramatic break with the past. The total remuneration fi gure of Rp 14 million just mentioned

is dominated by the special allowance of Rp 10.8 million.

A further important and closely related change concerns the fi lling of vacancies.

Whereas in the past individuals waited patiently until seniority brought them to the top of the list of those eligible for promotion to higher positions, under the new arrangements—still in the initial phase—vacancies are advertised internally, and anybody within the ministry who meets the job specifi cations (in relation to

requisite educational qualifi cations, skills and experience) is encouraged to apply.

Applications can be made via the internet, and CVs can be updated online. For the time being this kind of competition for promotions is limited to Echelon II posi-tions. After applications are received a short list is prepared, on the basis of which a committee of Echelon I offi cials makes its recommendations. Since promotions

previously have depended heavily on seniority but also on the backing of one’s superiors, the new approach is experiencing some opposition from Echelon I offi

-cials—uncomfortable, presumably, with losing their capacity to dispense patron-age to (and thus ensure the loyalty of) their subordinates. In order to minimise the infl uence of favouritism, the ministry now puts heavy emphasis on ‘key

per-formance indicators’ (KPIs), which are used to differentiate between applicants for vacant positions. At the highest level the minister holds quarterly meetings with her Echelon I offi cials, at which the latter are required to report on their own

achievements relative to KPI targets.

As yet there has been no move to open up ‘structural’ job vacancies to applica-tions from people outside the ministry, much less from the private sector, although limited outside hiring to fi ll ‘functional’ positions is well accepted. Functional

positions are those that require specifi c technical skills, whereas structural

posi-tions do not. For example, a medical graduate would probably be employed in a functional position open only to qualifi ed doctors, whereas an economics

gradu-ate would typically be employed in a structural position that might just as likely be occupied by an arts graduate. Within the MOF, applications for positions as lecturers at the ministry’s training institute (Sekolah Tinggi Akuntansi Negara) are accepted from outside. Arguably, the lack of opposition to outside recruitment

10 At an exchange rate of Rp 9,300/$.

to functional positions refl ects the fact that they require skills not possessed by

people already employed in the ministry. By contrast, there tends to be an over-supply from within of individuals eligible for promotion to higher structural posi-tions (albeit often lacking desirable skills), so any suggestion that outsiders should also be permitted to apply would be bound to meet with strong opposition.

It is hoped that the now more generous remuneration levels will provide a stronger incentive to employees of the ministry to work hard and to act with integ-rity and discipline, and new internal regulations stipulate a list of sanctions that can be imposed on those who do not live up to these expectations. Specifi cally, it

is envisaged that fi nes will be imposed in the form of deductions from the

spe-cial allowances: for example, employees who fail to come into the offi ce without

reasonable excuse will fi nd their monthly special allowances cut by 5% per day

of absence. For more serious offences employees can be subjected to deductions as large as 90–95% of their special allowances, or can be demoted or dismissed from their positions. It is hard to imagine that the threat of such penalties will have much of an impact, given an organisational culture averse to actually impos-ing them. On the other hand, the much higher remuneration available to those who gain promotion to the higher levels, in conjunction with a more competitive system of promotions based on individual performance, has the potential signifi

-cantly to alter the behaviour of ministry offi cials.

Although the original intention was for the new special allowance to replace the plethora of existing allowances, in fact it seems that many of the latter still exist, so that high-level bureaucrats now receive the new TKPKN allowance in addition to the allowances they received prior to reform. As a consequence it would appear that many are now paid far more generously than has been the case in the past—perhaps even more generously than would be necessary to bring them into line with their private sector peers. The problem is being tackled, however. For example, the ministry announced recently that all of its high-level offi cials

cur-rently serving also as commissioners of state-owned enterprises would be resign-ing from these positions as soon as practicable (Bisnis Indonesia, 12/6/2008).

Perhaps the minister’s most spectacular action in relation to bureaucratic reform was to remove some 1,200 individuals from the customs offi ce at Tanjung Priok,

Jakarta’s main port, and replace them with about 850 offi cials regarded as more

trustworthy. The new offi cials are monitored quite carefully, and there is a strong

emphasis on rewards for good performance and penalties for those who do not perform well. The ministry claims to be encouraged by the results of this shake-up, but it is under no illusion that the battle has already been won. At its request, offi cers of the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) carried out raids at the

end of May 2008 on the same Tanjung Priok offi ce, during which quantities of

cash, presumed to be bribes, were found hidden in the desk drawers of a number of customs offi cers (JP, 3/6/2008).

Local governments

Indonesia undoubtedly has a great deal to gain from successful reform of the central government bureaucracy. However, given the dramatic increase in responsibilities of local governments (districts and municipalities) since the beginning of 2001 under decentralisation, reform at that level is perhaps equally urgent. In January 2007 there were 456 local governments (363 districts and

93 municipalities),11 and the heads of a small number of these have gained a

reputation as pioneers of reform. The outstanding achievements of these few pioneers will not in themselves change the face of Indonesia, but the exam-ples they set, in combination with the recent introduction of direct elections for heads of government, seem likely to have a considerable impact in the longer run. Some of the individuals who have been able to develop a reputation as successful reformers at local government level are now seeking to build on that success by running for election at provincial level.

In order to gain some appreciation for what is being done by way of reform at local government level, the author briefl y visited two neighbouring district

gov-ernments in Central Java—the municipality of Solo and the district of Sragen—to interview their respective heads of government, both of whom have established reputations as active and successful reformers.

It is probably no coincidence that both the walikota (mayor), Bpk Joko Widodo, and the bupati (district head), Bpk Untung Wiyono, have considerable experience as private sector businessmen. This gives them a different perspective from the majority of their peers who have spent their entire careers within the bureau-cracy (and/or the military). In particular, when faced with a problem they seem naturally inclined to look for ways to deal with it, rather than to list the reasons why its solution is beyond their authority or capacity. It seemed clear that both men are in the habit of imagining useful things to do, and then fi nding ways to

get them done.

The entrepreneurial way of thinking can be seen in policies of the mayor of Solo in relation to small-scale trading activity in the city. All over Indonesia, such trad-ing is carried on in two main locations: traditional markets and public spaces. For the traders or shoppers who use traditional markets, these places leave much to be desired. Architectural eyesores, their design does not facilitate the movement of people and goods. They are usually poorly lit, poorly drained and unhygienic, lacking adequate sanitation facilities and garbage disposal systems. These short-comings are multiplied when pedagang kaki lima (PKL, petty traders) establish their own market areas in public spaces such as along roadsides and footpaths, in public parks and gardens and, indeed, around the fringes of traditional markets. As a result, the fl ow of traffi c in such locations is greatly hindered, and the visual

quality of the urban environment is seriously degraded.

In all of this the mayor perceived both the need for better management of some of the city’s major assets—its traditional markets and its streets and other pub-lic spaces—and the opportunity to generate substantial additional revenues. The traditional markets were totally rebuilt in modern form so as to provide a far more attractive and functional environment in which to carry out this kind of economic activity—which, of course, is a very important part of daily life within Indonesia’s lower income strata. In addition, an entirely new market was con-structed in order to relocate almost 1,000 PKLs then occupying much of the space in the park surrounding an important local monument. The design of this new market took into account inputs from the PKLs following a deliberate program of

11 A list is available at <http://www.bps.go.id/mstkab/mfd2007.pdf>.

consultation,12 and this mass relocation was therefore accomplished in a festive

atmosphere, without any of the protest—or even violent resistance—that is a typi-cal outcome elsewhere when city authorities decide to clear particular areas of informal traders by force. The new market is some fi ve kilometres away from the

original informal trading area, so the government upgraded the roads and public transport services leading to it. It also created much publicity for the move, as a result of which the new market is thriving.

None of the traders involved in this process was required to contribute any capital to the costs of construction or reconstruction of the markets; rather, these investments were funded from the city budget. However, all traders are now required to pay a small daily fee (retribusi) for their occupancy. This provides a signifi cant additional revenue stream from which the mayor expects, for example,

to repay the costs of construction of the new market within about eight years. These initiatives amount to a remarkable success story: the park has regained its status as green space; traders and their customers have much improved environ-ments in which to interact; traffi c fl ows more smoothly on the city’s streets; and

the government has acquired a signifi cant additional revenue stream. As a

conse-quence of this and other policy initiatives the mayor appears to enjoy considerable popularity and respect among his constituents. These are the kinds of outcomes it was hoped could be achieved by bringing government closer to the people through decentralisation, and by the switch to direct election of heads of government.

The bupati of Sragen is also having a signifi cant impact on the daily life of his

constituents through an extraordinarily wide range of initiatives, ranging from the creation of wireless ‘hot spots’ for internet users to the processing of market refuse to produce bio-gas (Suherdjoko 2008a). He has built a high public profi le,

and uses it to exhort both government employees and the general public to work hard and to be creative. One of the most basic ideas about being in business is that high profi ts are available only to those willing to do different things or do

things differently. Thus, for example, the bupati encourages farmers to involve themselves in mixed farming (combining livestock and/or fresh-water fi sheries

with crop production) and to ‘go organic’—conscious of both the negative long-term impact of inorganic fertilisers on soil quality and the much higher prices commanded by organic food products. To this end, he places government person-nel in the villages to advise farmers on such matters and to motivate them to seize new income generation opportunities.

The government has its own experimental farming area for research on organic farming, and it encourages the local population to switch to organic foods for health reasons. At the same time, it provides opportunities for individuals outside agriculture to learn new skills useful in business. To this end, it has established a training agency to teach a wide range of skills, such as garment and furniture making, automotive and electrical repairs, English language, beauty salon man-agement and the use of computers and information technology. Such training is provided free of charge to those who are unemployed or are seeking to enter the workforce for the fi rst time.

12 A local NGO, Kompip (Consortium for Monitoring and Strengthening Public Institu-tions), which focuses on democratisation and is supported by the Ford Foundation, claims some of the credit for this (Kompip 2007).

Another achievement has been the conversion of dry waste land to productive use through irrigation (Suherdjoko 2008b). This has been accomplished mainly by tapping into artesian water, which seems to be quite plentiful in the area. Many small dams have been constructed that permit this water to be stored and then pumped into rice fi elds, allowing three harvests per year rather than one or two.

Some dams are also used for fi sh farming, and the government has a facility for

breeding fi sh, eels, prawns and so on, which are then placed in the dams until they

mature. A recent resurgence in the popularity of batik in Indonesia has provided an opportunity to exploit yet another under-utilised local resource: the skills of batik makers. The government has established a batik showroom on the main street of Sragen, from which it markets a wide range of batik products, relying exclusively on local artisans—who, in turn, use only organic dyes. It claims to assist some 17,000 batik makers in this way.

The kabupaten (district) government is pioneering a revolution in the recruit-ment of civil servants (Pemkab Sragen 2008). Rather than ranking applicants on the basis of a general examination, as is the usual practice throughout Indonesia, it now screens them carefully for competency in the particular skills it needs. For example, applicants for a position in public relations are tested on their ability to write press releases, draft speeches or public presentations, take photographs, shoot and edit videos, and undertake graphic design work. All applicants are also tested on their computer skills and English language abilities, both of which are regarded as essential. In an attempt to ensure a professional and fair selection process, the government involves academics from nearby universities, along with a team from an independent fi rm of educational consultants.

Such an approach to recruitment is self-evidently sensible, so it is indicative of the fundamental malaise in human resources management in government throughout the nation that the kabupaten had to obtain special permission from the civil service ministry before it could put this into practice. By contrast, there is yet to be any signifi cant change to human resources management in Solo because

of continuing and counter-productive control from the centre. The mayor com-plained that perhaps half of his employees were surplus to real needs, yet he is prohibited not only from dismissing them but even from reducing the total number through attrition (i.e. through retirements and deaths). On the contrary: the civil service ministry instructs his government as to how many new staff must be recruited each year, without even allowing it to select only those applicants with useful skills.13

Both the mayor and the bupati were well aware of the stifl ing impact of

bureaucratic red tape on both businesses and individuals in the past, and both have established what appear to be very successful ‘one-stop shops’ to facilitate the issue of documents such as licences, permits, identity cards and health care cards.14 Past practice, familiar throughout Indonesia, involved a tortuous process

in which individuals would have to approach one (typically unsmiling) offi cial

after another, usually in uncomfortable and unattractive surroundings, wasting

13 This is in spite of the minister’s earlier observation that ‘the number of civil servants would be reduced by at least one million in order to improve effi ciency’ (JP, 10/16/2006).

14 Indeed, the bupati felt that many of the existing requirements for permits and other documents served no useful purpose, so he simply abolished them.

hours, days or weeks of valuable time, and probably having to hand over ‘grease money’ in order to make any progress at all.15 Under the new approach, offi ces

have been attractively refurbished to allow friendly, across-the-counter inter-action with a single offi cial, who is able to see the process through to completion

in a far shorter—and pre-specifi ed—time. Indeed, Sragen has led the nation in

introducing a system that also allows these kinds of interactions to be under-taken online (JP, 8/4/2007).

Interesting differences emerge in regard to remuneration of offi cials in these

two local governments. The mayor argued that as a result of controls imposed by the central government he had virtually no freedom to make any kind of incentive payments to his offi cials. Moving to the one-stop-shop approach deprived many

offi cials of the additional income they obtained previously in the form of bribes

intended to hasten the issue of permits and other documents, and the loss of this income might have been offset by compensating increases in salaries or allow-ances. In the absence of such compensation there was some initial resistance to this radical new way of doing things. The mayor was able to overcome this, how-ever, simply by shifting a couple of recalcitrant offi cials to other positions where

they had no opportunities for soliciting bribes. This was suffi cient to overcome

any potential opposition from other offi cials.

By contrast, the bupati has found a way to reward good work with better remu-neration. His solution to the problem of central control is to argue that, although he may not make incentive payments using funds transferred from the central government, any revenue he can generate from business activity becomes peda-patan asli daerah—own-source revenue—which he is free to use as he chooses. Thus, for example, with the assistance of various local fi nancial institutions, he

has established a lending program designed to help local micro-enterprises. This program seems to be running satisfactorily, and he allocates half of its interest income to boost the remuneration of government employees. In similar vein, he found it possible to pay off the debt of the local water supply company using budgetary savings,16 and the consequent savings in interest payments—together

with a small increase in the charge for piped water—rendered the company newly profi table, adding further to the district’s own-source revenue.

Both the Solo and Sragen governments not only have a strong focus on facili-tating private sector business activity, but also have signifi cant poverty

allevia-tion programs. The most important of these involve free educaallevia-tion and health care for the poor. The Solo government also has a lending program designed to upgrade the housing of the poor from slums to simple though decent houses built to standard designs. It is careful to fund only a modest share of the total cost involved, leaving the owners and their families with the responsibility to cover the rest.

15 In typically blunt fashion, the bupati described the district’s employees in the past as lazy, lacking creativity, non-innovative, and responsive rather than pro-active; bureau-cratic procedures were described as slow and rigid, and accompanied by petty extortion (pungutan liar or pungli).

16 He found that it was possible to cut the actual cost of certain large capital expenditure items (such as bridge construction) by more than half relative to the budgeted amounts through more careful procurement procedures.