Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 18:59

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Student and Professor Similarity: Exploring the

Effects of Gender and Relative Age

Kenneth Gehrt, Therese A. Louie & Asbjorn Osland

To cite this article: Kenneth Gehrt, Therese A. Louie & Asbjorn Osland (2015) Student and Professor Similarity: Exploring the Effects of Gender and Relative Age, Journal of Education for Business, 90:1, 1-9, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.968514

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2014.968514

Published online: 06 Nov 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 111

View related articles

Student and Professor Similarity: Exploring

the Effects of Gender and Relative Age

Kenneth Gehrt, Therese A. Louie, and Asbjorn Osland

San Jose State University, San Jose, California, USA

The authors examined student responses to faculty traits. Earlier findings revealing a preference for male instructors were obtained before female faculty and students were prevalent on college campuses and may have reflected a male demographic similarity effect. It was hypothesized that students would more favorably evaluate faculty who were similar in gender and in relative age (as reflected in faculty rank). As anticipated, female students evaluated female lower ranked faculty most favorably, and male higher ranked faculty least favorably. However, male students showed mixed effects. Although their evaluations were more favorable for lower ranked male faculty, they unexpectedly did not degrade higher ranked female faculty. Discussion focuses on gender-related causal factors and implications.

Keywords: communicator distinctiveness, gender, rank, similarity-attraction, teaching evaluations

Effective teaching stems in part from the ability to attract and to maintain students’ attention. More generally, success for many professionals (e.g., academics, industry leaders, politicians, religious advisors, athletes) depends on eliciting levels of responsiveness in targeted audience members. Researchers have long advocated that individuals identify especially strongly with those who share similar character-istics (Berscheid & Walster, 1983; Deshpande & Stayman, 1994; Hoffner & Buchanan, 2005), which is the basic prem-ise behind similarity-attraction theory (Bove & Smith, 2006; Byrne, 1971). A real-life illustration of the shared trait effect comes from the world of professional sports. In 2012 the New York Knicks had a high-performing guard named Jeremy Lin, an Ivy League–educated Asian Ameri-can of Christian faith. Due to his unique similarity to vari-ous groups of fans, his rise in fame corresponded with a 31% increase in his team’s parent company’s stock (Luo, 2012). Another example of similarity-attraction comes from the political world. In 2008 when then-Senator Hillary Clinton sought to become the Democratic candidate for president, much of her support was from females in her age group (Sullivan, 2008).

This research examines the effect of demographic simi-larity in higher education. Student and faculty congruence

in gender and relative age (as reflected by faculty rank) is explored through the real-life measure of teaching evalua-tions. Investigating similarity effects in higher education is especially worthwhile because recent history has seen dra-matic changes in the gender proportions of undergraduates and instructors (Clery, 1998; Mather & Adams, 2007). Therefore, we also aim to gain insights into how evolving norms might have altered perceptions of faculty members. The following is a review of work on demographic match-ing in college settmatch-ings.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Faculty Evaluations: Effects of Gender

Official teacher ratings often lack the requisite information to explore both student and instructor demographics. In addi-tion, substantial hurdles may exist to gain permission to use proprietary data. For these reasons, it can be difficult to find studies using university-required teacher evaluations to explore student and faculty gender. It is reasonable to expect male and female professors’ teacher ratings to reflect social norms. Prior to the 1990s there were noticeably more male than female professors at colleges (Clery, 1998) and more male than female students (Mather & Adams, 2007).

During that time, research using official teaching evalua-tions revealed preferences for male faculty members. When

Correspondence should be addressed to Asbjorn Osland, San Jose State University, Department of Organization & Management, One Washington Square, San Jose, CA 95192-0070, USA. E-mail: asbjorn.osland@sjsu.edu ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online

DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.968514

Sidanius and Crane (1989) conducted analyses using stu-dent and instructor gender, they found that male faculty received significantly higher evaluations than female fac-ulty on global teacher effectiveness and academic compe-tence. Qualitative and survey research findings concurred, revealing strong male student to male faculty preferences (Basow, Phelan, & Capotosto, 2006). The results paralleled those prevalent in industry during that time period, wherein male subordinates reacted more favorably to male than to female supervisors (Bass, 1990).

However, in recent decades there has been substantial movement toward gender parity on college campuses. Between 1976 and 1995, the percentage of women academ-ics increased by 114% (Clery, 1998). Also, since 1991 the proportion of young women in college has exceeded that of young men; by 2005 women comprised 54% of young adult college enrollment (Mather & Adams, 2007). Changing campus demographics have provided an opportunity for student perceptions to shift such that the inclination towards male faculty may not be as prevalent. By the mid-1990s, female students were showing some preferences for female instructors (Centra & Gaubatz, 2000). The one-directional preference for male faculty might have changed with the increased exposure to both genders.

Faculty Evaluations: Effects of Relative Age as Reflected in Rank

Gender diversity has altered not only the overall proportion of male and female faculty, but also their representations in vari-ous professional ranks. Over the years, increasing proportions of women have been promoted to full professor. This provides an opportunity to examine a second variable, relative age. Although it can be difficult to obtain specific information about birth years due to privacy protections, past work has used pro-fessional rank as a reflection of the relative age between stu-dents and faculty (Blackhart, Peruche, DeWall, & Joiner, 2006). As a group, junior faculty are closer in age to students and may benefit from a more natural rapport. Also, tenure and promotion goals are strong incentives to provide excellent classroom service. Alternatively, full professors may excel in teaching due to their years of experience and to the reduced pressures that come with promotion.

In actuality—similar to research on faculty gender— studies on instructor status have shown mixed results over the years, providing varied insights into the rank-related variable of age. More than three decades ago Nation, LeUnes, and Gray (1976) compared ratings for professors and graduate teaching assistants in Psychology. When pro-fessors received higher evaluations, the researchers postu-lated it was a teaching experience effect, and noted the lack of evidence for age-based natural rapport. In the 1980s, however, researchers examining faculty rank showed no effect for this factor (Hoffman, 1984; Romeo & Weber, 1985).

More recent evidence suggests that social customs and academic training may have changed in favor of younger and lower ranked instructors. In the early 2000s researchers found higher teaching evaluations for tenure-track than for tenured faculty (Isely & Singh, 2007). Blackhart et al. (2006) found that psychology students provided better rat-ings for graduate teaching assistants than for tenured and tenure-track faculty. The researchers postulated that the teaching assistants benefitted from perceived similarity to students, and from the enthusiasm, effort, and energy they brought to class. Although the study did not reveal signifi-cant differences within faculty ranks, the mean rating was higher for junior than for fully promoted professors. Note that in Blackhart et al.’s study, faculty members had pro-vided extensive instructional training to the teaching assis-tants. The graduate students’ high level of training, combined with their rapport with those they taught, may have overshadowed significant evaluative differences across the faculty members’ ranks.

Research Purpose and Hypotheses

In sum, the changing gender composition of faculty and stu-dents in higher education presents an opportunity to re-examine how gender and relative age (as reflected in rank) influence the perception of faculty. If individuals are drawn to those who share similar characteristics, students will more favorably evaluate same-gender faculty of lower rank. Hence, female students may provide the most favor-able ratings for lower ranked female professors, and male students may evaluate most favorably lower ranked male professors. Dissimilarity may also affect evaluations such that the most unfavorable ratings from both student groups might be for higher ranking faculty of a different gender. Thus we present the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Based on similarity, female students would most favorably evaluate female faculty of lower rank.

H2: Based on dissimilarity, female students would least favorably evaluate male faculty of higher rank.

H3: Based on similarity, male students would most favor-ably evaluate male faculty of lower rank.

H4: Based on dissimilarity, male students would least favorably evaluate female faculty of higher rank.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Teaching Evaluations Dataset

We used official teaching evaluations to examine the effects of gender and relative age similarity. Students enrolled in undergraduate classes at a large public American university anonymously completed official end-of-the-term teaching

2 K. GEHRT ET AL.

evaluations. The dataset contains information for tenured or tenure-track faculty from one semester, which includes 27,583 completed evaluation forms from all divisions across campus that provide undergraduate courses (i.e., Arts and Sciences, Business, Education, Engineering, Humanities and the Arts, Science, and Social Sciences).

Teaching evaluations are used in this study because they are the best means to obtain campus-wide data with which to explore the study hypotheses. The goal of this work was not to verify their validity but rather to gain insights into students’ perceptions of professors. However, as at many college campuses, it is important to recognize that the pro-cess of collecting teaching evaluations is not flawless. At the focal university in this research, every professor is supposed to collect teacher evaluations but it is unknown how strongly they enforce this rule. It may be that poor-performing faculty are less likely to collect evaluations, in which case the data-base would have a bias in favor of better teachers. In addi-tion, all students were encouraged to complete evaluations but to ensure anonymity their identification was not tracked, and it was not possible to ascertain the courses’ dropout rates. There were 21,396 undergraduates on campus, 28% of whom were part-time students. As with any rating system, students may be more inclined to complete surveys when they feel strongly positive or negative about their experien-ces, or when they have time to provide feedback. The uni-versity administrators who control the database noted that ratings were turned in for the vast majority of classes. How-ever, as information for the total number of courses offered in the term was unavailable, this research pertains to the 1,105 classes for which there were official evaluations. Given the constraints of the data, this study does not include some of the factors explored in past studies such as class length, enrollment level, teaching style, or instructor publica-tion history (Basow et al., 2006; Blackhart et al., 2006; Isely & Singh, 2007). Although an understanding of these varia-bles is important, they are beyond the scope of this research. Finally, there was no measure other than the students’ rat-ings with which to evaluate teaching. Again, the purpose of the study was not to verify the evaluation process but, rather, to gain insights into student perceptions of faculty as reflected in official teacher ratings.

While there are pros and cons to end-of-the-term evalua-tions, they nonetheless play a major role in promotion and merit decisions, are used extensively by Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business-accredited schools (Comm & Mathaisel, 2000), and are deemed a starting point with which to explore the effects of gender and rank-reflected age.

Student and Faculty Gender

At the end of the official teaching evaluation form students were asked to note if they were male or female. For 1.62% of the returned materials the question was unanswered; the

responses from this group were excluded from the analysis. For faculty gender, each course had a random identification number that in an independent file was listed with instructors’ names. Files from the human resources depart-ment provided gender information that was matched with teaching evaluations.

Faculty Rank-Related Age

Following the same procedure that was used for inputting faculty gender, human resources data provided information about rank. The higher ranked group was composed of full professors, while the lower ranked group represented all remaining tenure-track faculty. For privacy reasons, it was not possible to obtain more detailed information for profes-sors in the dataset, or their years of birth. The same issue occurred in Etgar and Fuchs’s (2011) research that exam-ined ethnic similarity effects between Israeli patients and their doctors; as data for the medical specialists’ ethnicities were not available, the information was based on partic-ipants’ perceptions. We deemed that justifiable because consumers’ views of service providers’ demographics are typically perceptual rather than fact-based. In the same way, although the inclusion of age data would be ideal, fac-ulty typically advance through young adulthood in tenure-track positions before serving as full professors. Overall, age similarity to students is closer for lower than for higher ranked faculty. Therefore, as in previous work (Blackhart et al., 2006), in this study insights into relative age similar-ity are based on faculty status.

Student Measures: Ratings and Expected Grade

The dependent variable is the teaching measure that largely affects faculty promotion decisions at the target university in this study. Students responded to the statement, “Overall, this instructor’s teaching was” with ratings on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very ineffective) to 5 (very effective). Research findings suggest that students’ expected course grades can influence heavily teaching evaluations (Blackhart et al., 2006). Therefore, responses to the evaluation form ques-tion, “What is your current estimate of your expected overall grade in this course?” were used as a covariate. As 1.52% of the surveys did not contain an overall instruction rating, and another 0.64% did not provide an expected grade estimate, the total number of usable evaluations was 26,522. Expected grade was a significant covariate,F(1, 26,551)D1521,p<.0001,

when conducting the 2 (student gender)£2 (faculty gender)£

2 (faculty rank) data analysis.

FINDINGS

For an overview of the data, the number of responses col-lected for female and male faculty is presented in Tables 1

and 2, respectively. An analysis of variance revealed two significant teaching evaluation main effects. The mean rat-ing is more favorable for lower than for higher ranked fac-ulty (M D 4.30, SD D 0.85; M D 4.18, SD D 0.91, respectively), F(1, 26,552) D 44.96, p < .0001. A more

favorable mean evaluation is also seen for female than for male faculty (MD4.31,SDD0.86;MD4.19,SDD0.90, respectively), F(1, 26,551)D26.57, p <.0001. There are

no other significant main effects or two-way interactions. However, there is a significant three-way interaction of stu-dent gender, faculty gender, and faculty rank,F(1, 26,551)

D26.13,p<.0001.

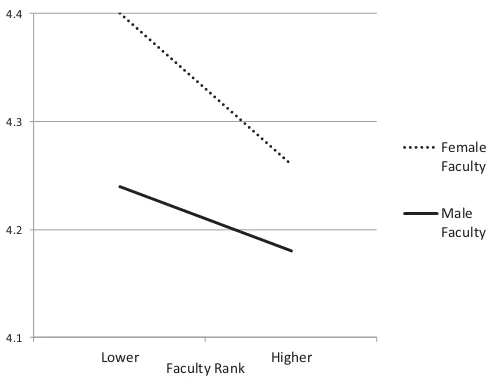

Female Students’ Findings

Figures 1 and 2 compare the dependent variable means across the study conditions. The female student data sup-port the prediction that students prefer faculty most similar in gender and relative age. As seen in Figure 1, and provid-ing support forH1, the most favorable mean rating across the eight experimental conditions are from female students for lower ranked female faculty. Post hoc tests (p <.05)

reveal that the mean rating (4.40, SD D 0.81) is

signifi-cantly more favorable than that provided by (a) female stu-dents rating higher ranked female faculty (MD4.26,SDD

0.88), (b) female students rating lower ranked male faculty (MD4.24,SDD0.87), and (c) male students rating lower

ranked female faculty (MD4.26,SDD0.86).

Also, in support ofH2, female students’ least favorable mean rating is for professors with whom they were most dissimilar, the male higher ranked faculty. This mean

(MD4.18,SD D0.89) is significantly less favorable than

that for male lower ranked faculty, and that for female higher ranked faculty. In sum, the direction of the results is as predicted for female students.

Male Students’ Findings

As seen in Figure 2, the data for male students provides mixed support for the notion that they prefer faculty who are similar to them. Although the male students’ highest rating is indeed for lower ranked male faculty, there is only partial support for H3. Specifically, that mean evaluation (4.28,SD D0.86) is (a) significantly more favorable than

that from male students for higher ranked male faculty (MD4.11,SDD0.94) and (b) marginally (p<.10) more favorable than female students’ ratings for lower ranked

TABLE 1

Frequencies and Percentages for Female Faculty

Faculty rank

Lower Higher

Students n % n %

Female 3,583 54.8 2,956 45.2

Male 2,087 54.5 1,743 45.5

Total 5,670 54.7 4,699 45.3

TABLE 2

Frequencies and Percentages for Male Faculty

Faculty rank

Lower Higher

Students n % n %

Female 3,122 40.1 4,669 59.9

Male 3,229 38.5 5,163 61.5

Total 6,351 39.2 9,832 60.8

4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4

Lower Higher

Female Faculty

Male Faculty

Faculty Rank

FIGURE 1 Female students.

4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4

Lower Higher

Female Faculty

Male Faculty

Faculty Rank

FIGURE 2 Male students.

4 K. GEHRT ET AL.

male faculty (M D 4.24, SDD 0.87). However, the male students’ mean rating for lower ranked male faculty unex-pectedly does not significantly exceed that provided for lower ranked female faculty (MD4.26,SDD0.86).

Finally, contrary to H4the male students’ mean rating for dissimilar higher ranked female faculty (M D 4.25,

SDD0.89) is not most unfavorable, and in fact is

signifi-cantly more favorable, than that for higher ranked male fac-ulty. Different from the female students, the male-student findings do not completely support similarity effects.

CONCLUSIONS

Similarity Between Students and Faculty

It was proposed that the increased student and faculty gen-der diversity and the corresponding transformations in fac-ulty rank would prompt students to rate more favorably faculty who were most similar in gender and rank-sug-gested age. As anticipated, the female students’ most and least favorable evaluations are for the most and least similar faculty, respectively. In contrast, the male students’ find-ings are not as straightforward, especially with their absence of most dissimilar faculty downgrading. It is not the goal of this work to find groups superior in instruction or to explore the validity of teaching evaluations; instead, those measures are used to gain insights into student and faculty similarity. While today’s social norms encourage sensitivity and political correctness when discussing differ-ences based on demographics, not addressing the results risks hiding true perceptions and avoids a discussion of pos-sible related variables (Martin, 1994). Therefore, the unex-pected findings will now be explored with consideration to potential gender- and age-related causal factors.

Considerations: Female Faculty Findings

High female faculty ratings. The largely favorable evaluations for female faculty contrast with unfavorable female professional perceptions seen historically in higher education (Sidanius & Crane, 1989) and more recently in fields such as medicine (Stearns, Borna, & Srinivasan, 2001). The main effect of faculty gender in this study was unanticipated. While the female students’ evaluation of lower ranked female faculty was expected to be high, it additionally strongly exceeds that of every other student/ faculty pairing. Contrary to predictions, the male students’ ratings of low- and higher ranked females are not signifi-cantly lower than the male faculty counterparts. Numerous factors could have influenced the high female faculty rat-ings, such as the distinctiveness of their gender within the profession, their skill, the campus environment, and chang-ing gender norms. Each of these possible influences is considered.

Distinctiveness of communicator traits within a pro-fession. Further insights into the high female faculty evaluations may come from the proportion of male and female professors at the focal college in this study. This is potentially relevant due to research suggesting that traits which make communicators distinct within a profession can influence their evaluations. For example, Forehand, Deshpande, and Reed (2002), while not intending to find effects based on messenger atypicality, nonetheless found them when studying reactions to same-ethnicity spokesper-sons. Their participants included North American Cauca-sians who were either a minority or majority in their campus student population. The researchers made the par-ticipants’ ethnicity salient, and then exposed them to a print advertisement with a Caucasian spokesperson. The evalua-tion of the spokesperson was the same, regardless of the minority or majority status of the participants. In contrast, when Asian participants in parallel conditions viewed a print ad with an Asian spokesperson, they evaluated the spokesperson the most highly when they were in the minor-ity (versus majorminor-ity) group.

In discussing why minority group Asians reacted to the spokespersons with similar ethnicity yet the Caucasians did not, Forehand et al. (2002) reasoned it was due to the rela-tively low real-world proportion of Asian advertising spokespersons in North America. In other words, the Cau-casians in their sample viewed same-ethnicity advertising spokespersons regularly, and were therefore likely unaf-fected by the one in the study. In contrast, Asian spokesper-sons are not prevalent in the region where the study was conducted. That, combined with ethnic similarity, might have enhanced evaluations. Hence, the reaction to a spokes-person or messenger may be influenced in part by the prev-alence of his/her demographics within his or her profession. If the evaluation of a communicator depends in part not only on similarity to audience members but on his or her distinctiveness within a profession, it is worthwhile exam-ining the proportion of male to female faculty in this study. According to Tables 1 and 2, 39.05% of the evaluations in this research focus on female faculty. This corresponds somewhat to recent national estimates that females com-prise 42% of full time faculty in the United States (Curtis, 2011), and to human resources data indicating that they comprise 41% of faculty on the campus in this study.

As female faculty were a minority at this research study’s university, they—similar to the Asian advertising spokesperson in Forehand et al.’s (2002) work—might have been especially salient to the students sharing the same gendered trait. The combination of both gender and relative age similarity, combined with the comparatively low proportion of female professors, may in part account for the female students’ very high evaluation of the lower ranked female faculty. It might also explain why male stu-dents did not rate male faculty as highly as anticipated. As male faculty are prevalent in this research, their gender

may not have been as salient or appreciated as perhaps was the female faculty to female students.

There is one major difference between Forehand et al.’s (2002) findings and those of this study. The enhanced com-municator effect in their work occurred only when the eval-uators were population minorities on campus. In contrast, Tables 1 and 2 reveal that the female students are not a minority at the college of focus in this research. They con-stitute almost 54% of the teacher evaluations; in addition, enrollment data indicate that females comprise nearly 51% of the undergraduate population. However, there are many differences between Forehand et al.’s research and this work. While their advertising spokespersons were anony-mous and viewed only once, student and faculty identify each other’s names and are together for an entire term. More importantly, students interact with professors and depend on them to serve as educators, advisors, and letter writers. When communicators’ roles entail more long-term focus and leadership, the desire to have a connection with them may prompt a heightened sensitivity to shared traits when they are socially distinct in their profession. That may occur regardless of the minority or majority status of the evaluators. To illustrate, it is helpful to refer back to Clinton’s 2008 candidacy. As noted above, much of her support was from female voters in her general age group (Sullivan, 2008). This political example reflects an appreci-ation of professionals with whom the evaluators can iden-tify in terms of gender and relative age. Although female members of the baby boomer generation are not population minorities, they overall seemed to appreciate a candidate whose shared traits made her distinct in her field.

Skill. The relative salience of female professors might help to explain female students’ enthusiasm for them, but the results of this study suggest it is not the only factor pro-ducing favorable evaluations. Male students also provided favorable ratings for female professors such that those of lower and higher rank unexpectedly received similar or higher mean ratings relative to males of corresponding rank. At the college where this research was conducted, successful recruiting of skilled teachers, university policies (e.g., generous research and family leaves), or even luck might have enabled the university to hire female faculty equipped to earn high teaching evaluations. Additional evi-dence of female faculty skill at the focal campus in this study came from the past 10 university outstanding profes-sor of the year awards, 70% of which were given to women.

Campus environment. The size of the institution examined in this study may have influenced female faculty evaluations. Durvasula, Lysonski, and Madhavi (2011) noted that at large universities it may be difficult for stu-dents to feel meaningful levels of social integration and connectedness. Accordingly, feelings of alienation may be larger at public universities, which are less effective than

private universities at creating in-group attributes like school spirit and uniqueness (Judson, Aurand, Gorchels, & Gordo, 2009). It is possible that the female faculty at the high-enrollment public college in this study intentionally or unintentionally help to reduce levels of social disconnected-ness. That is, for better or for worse female faculty may be perceived as more approachable, which in turn might be especially important at large, less personal universities. This would be congruous with findings in the health care field in which consumers held higher expectations for female than for male physicians’ friendliness, likeableness, sociability, and warmth (Stearns et al., 2001). Expectations may be due to women’s, relative to men’s, historical emphasis on interpersonal affiliation (Meyers-Levy, 1988). Or, based on sex role traditions (Meyers-Levy & Zhu, 2010) it is also possible that students at the focal campus felt more comfortable approaching female faculty. If so, this gender-related bias can have duel effects as it might heighten evaluations yet also increase the time necessary to address students’ concerns.

Changing gender norms. In recent years increases in professional status achieved by female faculty have perhaps changed instructor gender norms. As noted previously, in the past male students showed a strong preference for male faculty, and that paralleled findings from industry wherein male subordinates reacted more favorably to male supervi-sors (Bass, 1990; Basow et al., 2006). Back then students may have entered college anticipating only male professors. That expectation, in turn, may have framed their preferen-ces. Since that time the general role of women’s profession-alism has heightened with almost 40% serving as the primary breadwinners in their households (Gibbs, 2009). In this study the male students’ overall acceptance of female faculty may reflect changing instructor expectations and a more general familiarity with female professionals. While it is not possible to know if undergraduates had precollege preferences for male or female faculty, the fact that either is possible reflects changes in norms in which students are more accustomed to encountering both genders in profes-sional roles. That may have enhanced the perception of female faculty in this study relative to past work.

Considerations: Male Faculty Findings

Heightened dissimilarity. Another unexpected find-ing in this study pertains to the male higher ranked faculty group which received the least favorable evaluations from both student genders. Keeping in mind that there are strong and weak instructors at every faculty rank and across the genders, possible explanations for the results are considered here.

One explanation pertains to the age range of this study’s male faculty, especially because heightened age decreases similarity to undergraduates. Perhaps because of healthier

6 K. GEHRT ET AL.

lifestyles, medical advances, and economic realities, pro-fessional longevity in some industries is becoming more common. For example, in 2010 the U. S. Senate had an atypically high average age of 63.1 years (Manning, 2010). In 2012, one senior senator who lost re-election, along with 10 retiring colleagues, departed with an average age in the early 70s (Bernstein, 2012). This may be happening in many professions as the population in the United States ages.

At this study’s target institution professors have an incentive to delay retirement because pensions are based on a combination of age and years of service. There is also an option whereby those who are formally retired can teach half-time for full pay for five years. These issues plus the much lower percentage of female than male faculty before the 1990s (Clery, 1998) suggest that the database might have a high proportion of instructors of advanced age who are male. Indeed, Tables 1 and 2 reveal that 67.7% of the ratings for higher ranked faculty were for male professors. In addition, the advanced age notion is supported by data from human resources. That is, although privacy concerns prevent the release of individual professors’ ages, categori-cal data for the faculty as a whole indicate that 9.8% were 65 years old and older. In that group, 66.5% were men. It is possible that the less favorable evaluation of male higher ranked faculty might be based in part on the advanced age and decreased similarity with students.

Communication differences. Increased age dissimi-larity can correspond with numerous generational differen-ces that widen the communication gap with undergraduates. While there have always been age-related differences in attire and popular culture, recent advances in technology may be having an especially dramatic effect on the evalua-tion of very senior faculty. Student attentiveness has been distracted by rapidly available information on the Internet and quick modes of communication (Rennie & Mason, 2004). Observations at the university in this study suggest that as the age increases faculty are less likely to use laptops or YouTube clips in the classroom. Although the educational value of nontraditionally delivered information has long been a subject of debate (Sonner, 1999), younger faculty at the focal university in this research more readily understand, and try to accommodate, students’ decreasing attention spans. That extra effort may explain lowered evaluations for the more traditionally teaching very senior faculty. Again, while changing media have traditionally separated the lec-ture styles of lower and higher ranked faculty, this difference may be exacerbated by the recent explosion in technology.

Implications and Applications

The research findings provide insights into how similarity influences students’ evaluations of faculty. First, it is help-ful to have at least two traits in common. Female and male

students rated same-gender faculty higher when the latter were similar in relative age. Fortunately, many other traits can provide connections between faculty and students, such as shared academic interests, favorite hobbies or sports, and similar backgrounds.

Second, in accordance with Forehand et al.’s (2002) findings, similarity effects may be enhanced when the indi-vidual being evaluated is distinctive within his or her pro-fession, as is evidenced by the relatively high evaluation of female faculty. Although it may seem intuitive to consider the favorable effects of those who are underrepresented in their profession, that idea—similar to many business con-cepts—is not always obvious in practice. Referring back to the Jeremy Lin example, at the height of his popularity he separated from the Knicks when the team decided against matching his offer from a competing organization. As a result, the Knicks saw their parent company stock drop 8.5%. Journalists within and outside of sports felt the choice reflected a lack of understanding with regard to the value of demographic similarity (Dwyer, 2012; Kamer, 2012). Accordingly, the findings of this study concur that similarity may matter most in situations wherein consumers feel underrepresented in the target person’s profession.

In addition, while similarity may help, extreme dissimi-larity may hurt. The lowest evaluations occurred for higher ranked male faculty. As noted previously, it is suggested that this finding is at least in part due to the latter’s collec-tive advanced age and further dissimilarity to students. To address this issue, lessons might be learned from an exam-ple, again from the political arena. Indiana Senator Richard Lugar held his title for 36 years until he lost the Republican Senate primary in 2012 when he was 80 years old. While recognized as a significant figure in foreign policy, many in his home state felt he had lost touch with them, as evi-denced by his late 1970s sale of his Indiana home (O’Donnell, 2012). For the outcome of his campaign to have been different he needed to make continued efforts to connect with his constituents, which can be harder to achieve over time. In the same vein, male and female senior professors may have invested much of their careers devel-oping expertise, with the tradeoff of less time spent on emerging areas of concern. Luckily, faculty of more advanced age can keep current by fine tuning and updating course assignments as was likely done earlier in their careers. They can also put effort into a new course prepara-tion or a class not taught in years. This provides an opportu-nity to reboot, not by trying to appear young, but by creating fresh lecture notes that incorporate contemporary examples.

It was also suggested that faculty of advanced age may have larger communication gaps in the classroom than did their predecessors due to technological changes influencing information availability. The same concern exists in the business world. Marketing professionals from the Inc. 500, and even from the more traditional Fortune 500, are

increasingly adopting social media tools to communicate and provide added value to consumers (Barnes, 2010). In a similar vein, it may behoove male and female senior faculty who are many years away from their last high-tech training sessions to make efforts to learn new instructional methods. Even if such devices are not incorporated into lectures they may provide insights into how to communicate with stu-dents and their technology-influenced attention spans.

Finally, similarity effects may weaken as professional norms evolve. The male students’ favorable evaluation of female faculty contrasts with past findings of their prefer-ence for male faculty. This suggests that any expectation that professors are male has diminished, and perhaps that corresponding preferences no longer predominate. To the degree that the removal of biases and expectations is favor-able, the distinction between these research findings and those of the past is encouraging.

Recommendations for Additional Research

The dataset provided an opportunity to examine the effects of gender and relative age and to explore those variables outside of laboratory settings. Limitations to this effort should be addressed as well as future research ideas. Ear-lier, in the Research Methodology section we outlined potential drawbacks of using official teaching evaluations such as faculty or student lack of participation. In addition, this study is centered in only one area of the United States. Future researchers should test the generalizability of this work across American regions and subcultures. Additional studies can also examine if and how course type (e.g., requirement or elective, or quantitative or qualitative) inter-acts with demographics. An investigation using graduate students would further examine the pervasiveness of simi-larity effects, especially with regard to relative age. Explor-ing other variables would help determine which similarity traits are most important in higher education and in other settings.

As noted in the Research Methodology section, the use of an established dataset has both pros and cons. The real-life data are the closest approximation possible at the target university to evaluating all faculty. However, outside of a laboratory setting it is not possible to control all potentially influential factors. More generally, as it is impossible to randomly assign students and faculty to demographic groups, the study conditions may have differed based on variables unrelated to those of focus in this research. This work can be considered a starting point from which more controlled examinations can follow. Surveys that allow par-ticipants to provide in-depth, open-ended teaching evalua-tions can examine students’ precollege, present, and postcollege perceptions of faculty. In addition, as discus-sing demographics is sensitive, indirect or interactive quali-tative measures such as interviews and focus groups may

provide helpful insights into how students respond to facul-ties’ similar and dissimilar traits.

Having noted limitations of this research, it is worth-while to reiterate that the dataset contained official teaching evaluations used for formal faculty promotion decisions. Even if the information gathering process was difficult to control completely, the data have bottom-line consequences that make exploring patterns and causal factors worthwhile. In addition, the objective was not to measure teaching effectiveness but to explore students’ perceptions of faculty as reflected in formal evaluations. The present study’s find-ings contrast with past work and shed light on the impact of changes in demographic norms. The results suggest that when similarity matters consumers value it highly. Future research can explore when trait congruence is most conse-quential. In the meantime, it is hoped that the real-world findings from this work provide insights into student–fac-ulty similarity effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank David Mease, Heli Maldonado, Stuart Ho, Jodi Frick, Hailee Bouthillier, Jing Zhang, Joan Torne, andJournal of Education for Businesseditors for their con-tributions to this research. Author order is alphabetical.

REFERENCES

Barnes, N. G. (2010). Tweeting and blogging to the top. Marketing Research,22, 8–13.

Basow, S. A., Phelan, J. E., & Capotosto, L. (2006). Gender patterns in col-lege students’ choices of their best and worst professors.Psychology of Women Quarterly,30, 25–35.

Bass, B. M. (1990). Women and leadership. In B. M. Bass (Ed.),Bass and Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications, third edition(pp. 707–737). New York, NY: The Free Press.

Bernstein, J. (2012, May 8). That old, old Senate update.The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/post-partisan/ post/that-old-old-senate-update/2012/05/08/gIQA5FZ3AU_blog.html Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. (1983).Interpersonal attraction, second

edi-tion. New York, NY: Random House.

Blackhart, G. C., Peruche, M. P., DeWall, N. C., & Joiner, T. E. Jr. (2006). Factors influencing teaching evaluations in higher education.Teaching of Psychology,33, 37–39.

Bove, L. L., & Smith, D. A. (2006). Relationship strength between a cus-tomer and service worker: Does gender dyad matter.Services Marketing Quarterly,27, 17–34.

Byrne, D. (1971).The attraction paradigm. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Centra, J. A., & Gaubatz, N. B. (2000). Is there gender bias in student eval-uations of teaching?The Journal of Higher Education,70, 17–33. Clery, S. (1998). Faculty in academe.NEA Higher Education Research

Center Update,4, 1–8.

Comm, C. L., & Mathaisel, D. F. X. (2000). Assessing employee satisfac-tion in service firms: An example in higher educasatisfac-tion.Journal of Busi-ness and Economic Studies,6, 43–53.

8 K. GEHRT ET AL.

Curtis, J. W. (2011).Persistent inequity: Gender and academic employ-ment. American Association of University Professors. Retrieved from http://www.aaup.org/our-work/research

Deshpande, R. S., & Stayman, D. M. (1994). A tale of two cities: Distinc-tive theory and advertising effecDistinc-tiveness. Journal of Marketing Research,31, 57–64.

Durvasula, S., Lysonski, S., & Madhavi, A. D. (2011). Beyond service attributes: Do personal values matter?Journal of Services Marketing,

25, 33–46.

Dwyer, K. (2012, July 18). MSG stock dives following Jeremy Lin’s depar-ture, after an initial upshot in the wake of “Linsanity.”Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved from http://sports.yahoo.com/blogs/nba-ball-dont-lie/msg-stock-dives-following-jeremy-lin-departure-initial-202902733-nba.html Etgar, M., & Fuchs, G. (2011). Does ethnic/cultural dissimilarity affect

perceptions of service quality? Services Marketing Quarterly, 32, 113–128.

Forehand, M. R., Deshpande, R., & Reed, A. II. (2002). Identity salience and the influence of differential activation of the social self-schema on advertising response.Journal of Applied Psychology,87, 1086–1099. Gibbs, N. (2009, October 26). What women want now: A Time special

report.Time, 25–29.

Hoffman, R. A. (1984). Correlates of faculty performance.College Student Journal,18, 164–168.

Hoffner, C., & Buchanan, M. (2005). Young adults’ wishful identification with television characters: The role of perceived similarity and character attributes.Media Psychology,7, 325–351.

Isely, P., & Singh, H. (2007). Does faculty rank influence student teaching evaluations? Implications for assessing instructor effectiveness. Busi-ness Education Digest,16, 47–59.

Judson, K. M., Aurand, T. W., Gorchels, L., & Gordo, G. L. (2009). Build-ing a university brand from within: University administrators’ perspec-tives of internal branding.Services Marketing Quarterly,30, 54–68. Kamer, F. (2012, July 17). The Jeremy Lin effect on $MSG stock: Jimmy,

we’re going down. The New York Observer. Retrieved from http:// observer.com/2012/07/msg-stock-jeremy-lin-effect-leaving-07172012/ Luo, M. (2012, February 11). Lin’s appeal: Faith, pride and points.The

New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/12/

sports/basketball/the-knicks-jeremy-lin-faith-pride-and-points.html?pag ewanted=all

Manning, J. E. (2010, December 27).Membership of the 111th Congress: A profile. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved from http://www. senate.gov/CRSReports/crs-publish.cfm?pid=%260BL%29PL%3B%3D %0A

Martin, C. L. (1994). Political correctness in the service sector.Journal of Services Marketing,8, 3.

Mather, M., & Adams, D. (2007, February).The crossover in female-male college enrollment rates. Population Reference Bureau. Retrieved from http://www.prb.org/Articles/2007/CrossoverinFemaleMaleCollegeEnro llmentRates.aspx

Meyers-Levy, J. (1988). The influence of sex roles on judgment.Journal of Consumer Research,14, 522–530.

Meyers-Levy, J., & Zhu, R. J. (2010). Gender differences in the meanings consumers infer from music and other aesthetic stimuli.Journal of Con-sumer Psychology,20, 495–507.

Nation, J. R., LeUnes, A. D., & Gray, M. (1976). Student evaluations of teachers of psychology as a function of academic rank.Teaching of Psy-chology,3, 186–187.

O’Donnell, K. (2012, May 8). Lugar loses Indiana GOP Senate primary.

NBC Nightly News. Retrieved from http://www.nbcnews.com/video/ nightly-news/47345727

Rennie, F., & Mason, R. (2004).The connecticon: Learning for the con-nected generation. Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Romeo, F. F., & Weber, W. A. (1985). An examination of variables which influence student ratings of university faculty.College Student Journal,

19, 133–140.

Sidanius, J., & Crane, M. (1989). Job evaluation and gender: The case of university faculty.Journal of Applied Social Psychology,19, 174–197. Sonner, B. S. (1999). Success in the Capstone business course—Assessing

the effectiveness of distance learning.Journal of Education for Busi-ness,74, 243–247.

Stearns, J. M., Borna, S., & Srinivasan, S. (2001). The effects of obesity, gender and specialty on perceptions of physicians’ social influence.

Journal of Services Marketing,15, 240–250.

Sullivan, A. (2008, June 16). Gender bender.Time Magazine, 36.