Rock Art:

Recent Researches and New Perspectives

(Festschrift to Padma Shri. Dr. Yashodhar Mathpal)

Rock Art:

Recent Researches and New Perspectives

(Festschrift to Padma Shri. Dr. Yashodhar Mathpal)

(Vol. I)

Ajit Kumar

New Bharatiya Book Corporation

Publisher :

NEW BHARATIYA BOOK CORPORATION

208, IInd Floor, Prakashdeep Building,

4735/22, Ansari Road, Daryaganj,

New Delhi - 110002

Ph. : 011-23280214, 011-23280209

E-mail : deepak.nbbc@yahoo.in

All rights reserved. No part of the work may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

The Editors are not responsible for the views and opinions expressed by the contributors.

© Publisher

ISBN : 81-8315-263-5

978-81-8315-263-1

Type Setting: Dr. Rajesh S.V Cover Design: Dr. Ajit Kumar

Assistant Editors:

Rajesh. S. V

Abhyan. G. S Raj. K. Varman

Sachin Tiwary

Printed at

:

Jain Amar Printing Press

Yashodhar Mathpal

Padma Shri. Dr.Yashodhar Mathpal was born in 1939, in the small village of Naula, in Almorah district, he is an acknowledged Archaeologist, Curator, Philosopher, Gandhian and Artist.

Yashodhar Mathpal belongs to a category of dedicated and selfless lovers of art. His artistic talents came to the fore, as a child, when he had to assist his uncle, an astrologer, in drawing horoscopes and illustrating almanacs. Perusing his skills and interest, he later obtained his Masters degree in fine arts from Lucknow Arts College. Mathpal came back to his village and started teaching in the school founded by his father, who was a social worker and a follower of Gandhi. His fatherʹs nationalist idealism exposed him to Gandhian thought and philosophy which cultivated in him austerity and simplicity.

In 1973, he read a magazine article on the rock paintings of Bhimbetka near Bhopal in Madhya Pradesh. He resigned his job and with the few hundred rupees he had saved, set out to join the Deccan College under the University of Pune to obtain his Ph.D in Archaeology on Bhimbetka rock-paintings. Mathpal studied and reproduced the rock painting of Bhimbetka laboriously. He discovered that primeval drawings often tell stories of the lives of our ancestors who painted them. Consequent to obtaining his doctorate, Mathpal has carried out archaeological exploration-excavations and rock art studies in the regions of Kerala, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and the Shivaliks.

vi Rock Art: Recent Researches and New Perspectives (Festschrift to Yashodhar Mathpal)

England and Australia. He has also converted his drawings into glossy picture-postcards, to popularize and bring out the depth of ancient rock art.

It is one thing to eulogies art/folk-art and folk culture, and yet another to dedicate your life to the preservation of this rich and rare cultural heritage. With only his vision and invincible spirit by his side, Dr. Mathpal embarked on a venture which today has flowered into the Folk Culture Museum in Bhimtal. It is a one-man show and he runs it without accepting any aid either from the government or from any individual. The museum houses more than 700 stone implements of prehistoric period, collected and classified by Mathpal himself, old fossils, pottery and bricks recovered from prehistoric/historic excavation sites, dozens of woodwork specimen from Kumaoni region, rare manuscripts, and other folk and tribal crafts are the pride of his collections

He has authored eight books and has more than 175 published papers. He has presented papers in various national and international seminars and conferences and won accolades. His efforts and contribution to promote Indian culture has received appreciation from the society at large. He has been felicitated with several awards of international and national fame including Padma Shri from the Government of India. He continues his life, which is a saga of persistence, perseverance and patience at Bhimtal, nurturing his endeavour to preserve folk art and culture.

About this Book

This book is a humble tribute to Padma Shri. Dr.Yashodhar Mathpal, a scholar whom I had known from his rock art research works on Bhimbhetaka and Kerala. I got to meet him in person at New Delhi, while attending the International Conference on Rock Art organized by the IGNCA in 2012. I was deeply drawn to his scholarship, simplicity and affectionate approach. When I placed before him the thought and request of bringing out a festschrift volume in his honour, he acceded to it after some persuasion.

Considering the specialization of Dr. Mathpal, it was decided to devote the festschrift volume exclusively to rock art. The proposal received spontaneous support when placed before scholars working in the field. Papers on rock art from four foreign countries and nineteen Indian states find discussion in this book. I am grateful to all the scholars, foreign and Indian, who have contributed their research papers for this volume. It is heartening to note that a large number of young researchers are taking keen interest in rock art studies and have contributed papers. I am optimistic that this book will be useful to the connoisseurs of rock art studies.

Editing the articles and making it presentable for publication was an arduous task happily undertaken. In this task, I have had the support and active collaboration of young dynamic assistant editors like Rajesh.S.V, Abhyan, G.S, Raj.K.Varman and Sachin Kr. Tiwary. The credit of setting the books in its entirety goes to Rajesh, S.V, and I am indebted to him for it. I am thankful to proprietors of New Bharatitya Book Corporation, New Delhi Shri. Subhash Jain and Deepak Jain for conceding to publish the book.

vii

Page No. v-vi vii-xi

1-22

23-33

34-46

47-58

59-71

72-78

79-99

Contents

Yashodhar Mathpal

Contents

Vol. I

CUBA

1 Art in Majayara-Yara Elevations in Baracoa, Guantánamo, Cuba

Racso Fernández Ortega, Dany Morales Valdés, Dialvys Rodríguez Hernández, Roberto Orduñez Fernández, Alejandro Correa Borges and Juan Carlos Lobaina Montero

PERU

2 Quilcas and Toponymic Approach, an Original Contribution to Rock Art Research in Peru

Gori Tumi Echevarría López

ITALY

3 Prehistoric Pleistocenic Cave Art in Italy

Dario Seglie

PAKISTAN

4 Cup-Marks in Gadap, Karachi (Sindh, Pakistan)

Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

INDIA

5 Ladder Symbolism: Morphology and Meaning with Special Reference to Rock-Art India

Ajit Kumar

6 Some Thoughts on Rock Art

Bulu Imam

JAMMU AND KASHMIR

7 The Rock Art of Ladakh: A Historiographic and Thematic Study

viii

8

9

Stupas in Petroglyphs: A Living Héritage of Ladakh

Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak

A Note on Petroglyphs from Bomai, Sopore District, Jammu and Kashmir

Ajit Kumar and Abhishek Mishra

100-105

106-112

UTTARAKHAND

10 Situating Rock Art in the Archaeology of Garhwal Himalaya: A Fresh Look

Akshay Verma, Pradeep M. Saklani, Vinod Nautiyal, R. C. Bhatt, Sudhir Nautiyal, Bhagat Pawar, Manmatya Mishra and Nagendra Rawat

113-121

UTTAR PRADESH

11 Rock Art of Fatehpur Sikri Region with Special Reference to Bandrauli and Madanpura

Arakhita Pradhan

122-133

RAJASTHAN

12 Study of Rock Art and Associated Archaeological Cultures in Harauti Plateau, South-Eastern Rajasthan, India

Shaik Saleem

134-163

GUJARAT

13 Rock Paintings and Tribal Art in Gujarat: A Case Study

Urmi Ghosh Biswas

14 Prehistoric Investigations in Kutch, Gujarat

Shaik Saleem

164-174

175-180

MADHYA PRADESH

15 The Lower Paleolithic Petroglyphs of Bhimbetka

Robert G. Bednarik

16 Discovery of New Rock Art Sites and It’s Implications for Indian Archaeology in Central Indian Context

Ruman Banerjee, Radha Kant Varma and Alistair W. G. Pike

17 Decorated Rock Shelters of the Gawilgarh Hills

Prabash Sahu and Nandini Bhattacharya Sahu

18 Nanoun, A Rock Art Site Near Chanderi (Ashok Nagar District), Madhya Pradesh

Rajendra Dehuri and Sachin Kumar Tiwary

181-202

203-216

217-230

ix

19 Handprints in the Rock Art and Tribal Art of Central India

Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak and Jean Clottes

238-246

CHHATTISGARH

20 Some Aspects of Rock Art Research in Chhattisgarh Reference to Bastar and Adjoining Regions

G.L.Badam, Bharti Shroti and Vishi Upadhyay

with 247-274

BIHAR

21 Rock Art of Kaimur Region, Bihar

Sachin Kumar Tiwary

275-286

JHARKHAND

22 Distinct Dominant Thematic, Motivational and Stylistic Traits in the Rock Art of Southern Bihar and Adjoining Jharkhand

A. K. Prasad

23 A Newly Discovered Painted Rock Art Site at Banpur, Jharkhand

Himanshu Shekhar and Yongjun Kim

287-296

297-304

NORTH-EAST

24 A Note on the Rock Engraving of the North- East India

L. Kunjeswari Devi and S. Shyam Singh

305-315

ORISSA

25 Signs and Symbols in Odishan Rock Art and the Indication about Early Writings

Soumya Ranjan Sahoo

26 Glimpses of the Rock Paintings and Rock Engravings in Odisha

Tosabanta Padhan

316-320

321-331

Vol. II

ANDHRA PRADESH

27 Botanical Survey at the Rock Art Sites in Andhra Pradesh- A Report

M. Raghu Ram

28 Rock Art of Andhra Pradesh: A Review

P. C. Venkatasubbaiah

333-340

x

MAHARASHTRA

29 Rock Art of Maharashtra 367-379

Kantikumar A. Pawar

30 Petroglyphs on the Laterite Rock Surface at Kudopi, District 380-386 Sindhudurg, Maharashtra: Evidence of Prehistoric Shamanistic

Practices?

Satish Lalit

GOA

31 Rock Art of Goa- A Few Observations 387-394

M. Nambirajan

KARNATAKA

32 Rock Art at Kurugodu, District Bellary, Karnataka 395-414

M. Mahadevaiah and Veeraraghavan N.

33 Further Discovery of Rock Art at Tatakoti (Badami), North 415-424 Karnataka

Mohana R.

34 A Note on the Rock Art in Coastal Karnataka 425-432

T. Murugeshi

TAMIL NADU

35 Rock Art in Vellore Region 433-446

Rajan K.

36 Prehistoric Hunting from Palanimalai Paintings, Tamil Nadu – 447-456 An Ethno-archaeological Study

R. N. Kumaran and M. Saranya

37 An Iron Age-Early Historic Motif on the Rock Paintings of Tamil 457-460 Nadu

V. Selvakumar

KERALA

38 Petroglyphs in Kerala with Special reference to Those in Edakkal 461-474 Rock - Shelter, Kerala

Ajit Kumar

39 Some Fresh Observations on the Human Figures in Edakkal Rock 475-481 Engravings, Kerala

Praveen C. K. and Vijay Sathe

40 Rock Art in Kerala: Emerging Facets and Certain New 482-490 Interpretations

xi

41 Rock Art in the Great Migration Corridor of East Anamalai Valley

Benny Kurian

42 The Excavation of the Rock Shelter in the Anjunad Valley: A Preliminary Report

N. Nihil Das and P. P. Joglekar

43 White Paintings from Anjunadu Valley

Shabin Mathew

44 Discoveries of Rock Engravings from the Districts of Palakkad and Ernakulam, Kerala

V. Sanalkumar

Contributors

491-521

522-528

529-539

540-544

Discovery of New Rock Art Sites and It’s Implications for Indian

Archaeology in Central Indian Context

Ruman Banerjee

1, Radha Kant Varma

2and Alistair W. G. Pike

31 Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Bristol, BS8 1UU, U.K. (Email:

arxrb@bristol.ac.uk)

2 18c, Hastings Road, Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh, India (Email: radhak37_kant@ rediffmail.com)

3 Department of Archaeology, University of Southampton, SO17 1BF, U.K. (Email:

a.w.pike@soton.ac.uk)

by Carleylle from the Mirzapur region of Central India Central Indian rock art is long known for its exceptional rock paintings; depicting crucial stages of human

Abstract:

during the later half of nineteenth century till toda. During the first part of twenty first century a plethora of rock art sites evolution in the subcontinent. The inception of its discoverywas

have been discovered in India; particularly in Central India. It is relevant to mention here that the dataset is diverse and each rock art site has certain unique elements that other sites do not represent in their morphic record. However the variations of the morphic details and nature of their occurrences in different rock shelters and even within the same group of rock-shelters have not been explored yet. The methodological rigor and sound documentation techniques brought to light several new sites in the region during a field survey of nine months between 2010 and 2012. New discoveries of painted rock-shelters enhanced the total number of archaeological sites found in the given region, but also this poses new challenges for the preservation and conservation of the archaeological sites for future research and posterity. This paper details a few new discoveries in the districts of Mirzapur and Rewa discussing their present and future importance in rock art research and archaeology in Central Indian context.

Introduction

Rock art research in India has flourished within a period of a hundred and thirty years, right from the penultimate decades of the nineteenth century, when British officer Carleylle (1883, 1899) made his first discoveries in the then regions of Mirzapur and Central India. New sites in this region were discovered, documented and subsequently published by several other European officers and scholars as well (Cockburn, 1883 a,b;1888, 1899; Colonel Rivett-Carnac, 1877,1879; Brown, 1923). Later on, more scholars and researchers contributed fruitfully to enlarge the database incorporating their findings and discoveries throughout the twentieth century; finally proceeding towards the twenty-first century. Generations of archaeologists, anthropologists and other researchers have discovered and documented various painted sandstone rock-shelters in this region (Varma, 2012; Jayaswal, 1983; Tewari, 1990; Tewari and Singh, 1999; Tiwari, 2000; Partap and Kumar, 2009). Rock art research, overtime in the subcontinent, especially in India and particularly in Central India experienced a significant metamorphosis with technological advancements, recording techniques, site prospection and survey methods. Given the density of rock art clusters and motifs in Central India, it can be expected that in the coming years rock art enthusiasts and archaeologist will discover more sites (Varma, 2012; Banerjee

initiated

the

archaeologists

latter

204 Rock Art: Recent Researches and New Perspectives (Festschrift to Yashodhar Mathpal)

and Srivastava, 2013; Banerjee et al, 2013). However, the phenomenon of new site discoveries and its implications on local and national archaeological record depend on several parameters. Every new site comes with unique set of archaeological data. The specificity of archaeological data and anthropological interpretation play key roles in situating the sites within the context for future research and development both locally and nationally and perhaps depending on the quality of record globally. Rock art and its preservation in an open air rock-shelter context is an inextricably related issue. While detailing the data on rock art from the Central Indian region, it is equally important to describe the matrix of the art, the nature of the host rock, local climate and other anthropogenic activities to situate the art into perspective and to derive future implications from it. Here we aim to report a few new sites that yielded unique motifs and morphic variability which is not reported from any other Central Indian sites. These new findings demarcate the possibility of finding new types of motifs and variations in style in the entire iconographic record of the Central Indian region. Particularly the presence of thematic variability and morphic variability might have introduced the concepts of innovation, knowledge and probably identity generation for the past settlers of the region. The concepts and role of identity crisis and identity generation through rock art and archaeology is a recent trend in Central Indian rock art.

Study Area

Central India hosts a huge corpus of painted rock shelters in and around the areas of Mirzapur (23°52ʹ & 25°32ʹ N, 82°07ʹ & 83°33ʹE) having an area of 4,522 square kilometers (Drake-Brockman, 1911). Recently, the new district of Sonbhadra has been carved out from Mirzapur that used to form the southern part of the district. Mirzapur (Fig.1) is located just under the Vindhyan sandstone hills that received its dendritic drainage pattern from the prominent rivers of the region like the Ganges, Belan and Son (Chakrabarti and Singh, 1998).

The Vindhyan range being a border between the northern and peninsular India has a spread from Gujarat state in the West to Uttar Pradesh state in the north through the regions of Madhya Pradesh state. This range is situated at the southern border of the Gangetic valley, going through Mirzapur and at the northern part it forms the border of the lower Sivalik and the Himalayan Ranges. The Upper Vindhyan formations comprising sandstone, quartzite and shale along with the valleys of Mirzapur have been the home of prehistoric hunter-gatherers for a long time as revealed by the presence of various rock-shelters having numerous imageries and scattered stone tools on their surfaces. Mirzapur town being the headquarters of this district is bounded by the district Sonbhadra, in the south, districts of Rewa (Fig. 1) and Sidhi, in the south-west, district Allahabad in the north-west, district Banaras and Sant Ravidas Nagar in the north and district Chandauli in the north and north-east. The discoveries discussed in this paper were made in the border regions of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh; hence both the districts of Mirzapur and Rewa (24°19ʹ - 25°12ʹ30ʹʹ N & 81°.02ʹ -82°.19ʹ E) have been taken into account, since these two districts form the geographical boundary of present day landmass; although in the past they must have structured the landscape of the art for the hunter-gatherers and foragers. Rewa (Luard, 1908) is bounded by the districts of Mirzapur, Banda and Allahabad of Uttar Pradesh in the

205

B

Banerjee et al. 22014: 204-217

n

north and noorth-east; in the South by Sidhi distrrict and it shhares the bouundary withh Satna distrrict in the w

west.

Figure 1: MMap of Studyy Area

D

Discoveriies and th

heir naturee

A

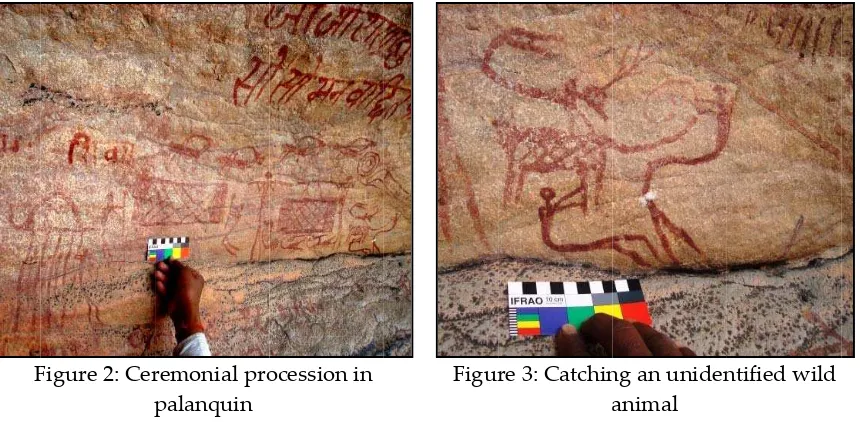

A few of thhe painted rrock-shelter sites of Miirzapur andd Rewa distrricts and thheir unique morphic eelements expplicitly delinneate their immportance in Central Inndian rock aart research iin the conteemporary ttimes. Differrent aspectss of these ddiscoveries ppave a wayy towards t he genesis of various kinds of k

knowledge aand/or idenntities in a rrestricted geeographic sppace and ecoo-geologicall niche. Thee painted rrock-shelter of Valwavi in Mirzapurr district deppicts a probaable ceremonial processsion which hhas never b

been documeented in the rock-shelterr archaeologgy of Centrall India beforre (Fig. 2).

F

Figure 2: Cerremonial proocession in Figurre 3: Catchinng an unidenntified wild p

palanquin aanimal

T

2

206 Rock AArt: Recent Reesearches and NNew Perspectivves (Festschriftft to Yashodharr Mathpal)

((Fig. 3). Thiss scene, wheere musical instrumentss like drumss are involveed, along wiith mythicall animals

introduce a sense of revvelry and rittual celebrattion. In Cenntral Indian context, thiss particular thematic eelement is quuite unique to this regioon. This landdmark scene of Valwavi might also pportray supeernatural aand sacred bbelief systemms of the preehistoric andd/or historic period artis ts, embeddeed within their social

irzapur

organizationn, but yet uunexplored, untapped and unscraambled. Teww

rresearch papper linked the mythiccal motifs aand themes from a spp

--((presently Soonbhadra diistrict) with the ‘Lorikayyan Episodee’. Tewari (20011) in his wwork also mmentioned tthat ‘some p aintings of tthe historicall period are clearly asso ciated with rreligious rituuals and activities. A cchronology has been suggested mainly onn the basiss of compaarative conssiderations, relative ssuperimposiitions and suubject matteer’. The chroonological asssessment, eeither relativve or absolutte, of the n

new discoveeries is beyonnd the scopee of this worrk, however certain themmatic variatioons in the roock art of C

Central Indiaa suggest addvanced forms, use of sspace, technique and styyle which have been coonsidered h

here very cauutiously. Teewari (1990) in his previious work cooncludes thaat a war-scenne at the Kaauva-Koh rrock-shelter imparts preeliminary cluues, where aa warrior is ddepicted ‘hoolding an eleephant in eaach of his rraised handss and both hhis feet trammpling an eleephant undeer them. Thiis figure may be associaated with ‘Lorika’ whoo is the hero of a popularr folk-lore knnown as ‘Loorikayan’ in tthe area’.

T

The ‘Lorikayyan Process’’ is not unifform to all tthe sites of Central India and inva riably differrent sites eexemplify diifferent sets of data andd various tyypes of knowwledge. Valwwavi is a goood example behind tthis reasoninng, which deepicts mythiical animals and humanns, deer hun ting scenes, marching ddeers and aalso househhold scenes. The centraal theme of this rock-sshelter can be related to alleged mmarriage cceremony ass well, althouugh this analogy might ssupport the ‘Lorikayan’ tale, dominnant in the diistricts of

districts the revolves ar B

Banaras, Allaahabad and Mirzapur aand popular among the local tribals . Lorikayan oound the love affair off the Ahir heero Lorik annd his lover CCanda. Interrestingly in these three versions o

of the folklorre is differennt and have been sung iin a differennt way throuugh differentt linguistic mmediums like Avadhi,, Bhojpuri, MMaithili, Maaghahi and Chhattisgarrhi. Already published literatures ffrom this rregion confirrm the fact (Pandey, 19987; Khande lwal and Chhandra, 19611: 51-4). Thee study at thhe site of V

Valwavi revveals copiouus amount of vandalissm. Devanaagarii and HHindi scrippt have beeen found ssuperimposeed on the unnique themattic element oof the site.

Figure 44: Vandalismm in the formm of inscriptiions

rock-shelter

207

The identified and readable part of the vandalism reads (Fig. 4) ‘SESH SRAHAS MUKHVARNANHARI DINAN KE DUKH HARAT BHAVANI’ which according to the local people and local belief is a part of ‘SHIV-PARVATI CHARIT’ or the chronicles of ‘Lord Shiva’ and his wife ‘Goddess Parvati’. From another part of the same rock-shelter, but away from the supposed holy ritual or thematic element the sacred ‘Gayatri Mantraii’ has been documented. This fact confirms the presence of different Hindu sects in the region perceiving rock art in differing perspectives. One of the field guides, who belong to the Kol tribal group of Mirzapur region, tried to relate the painted theme to a marriage ceremony or some sort of ritual involved with some mythical unidentified animals and mentioned about the love affair of Lorik and Canda. On the other hand the vandalisms in the painted parts of the shelter in the form of hymns and narratives suggest the dominance of present day Hindu religious elements in the same area. This dualism in terms of perception and interpretation of individual rock art motifs and themes among the local people, who could be the ethnic groups of the region and/or Hindus, is a striking feature of Central Indian rock art, particularly in the regions of Mirzapur and Rewa. In this case we noticed that attempts to interpret the motifs have been made by both the groups of contemporary society in the border areas of Mirzapur and Rewa who are not specialists in rock art or trained archaeologists and anthropologists. Such unique evidence was only found at Valwavi, which indicates that this particular section of the entire painted canvas is reasonably young; although the motifs are not dated by means of absolute chronology yet. Other parts of the shelter exhibit different morphic elements in red ochre, same as the previous. But thematically and motif wise the paintings suggest long antiquity within this particular shelter. It appears to be the case, that the same rock-shelter was visited and revisited by different groups of people overtime, having different ideologies that enabled the creation of diverse morphic elements and sometimes unique elements that have not been reproduced elsewhere in the entire region.

Banerjee et al. 2014: 204-217

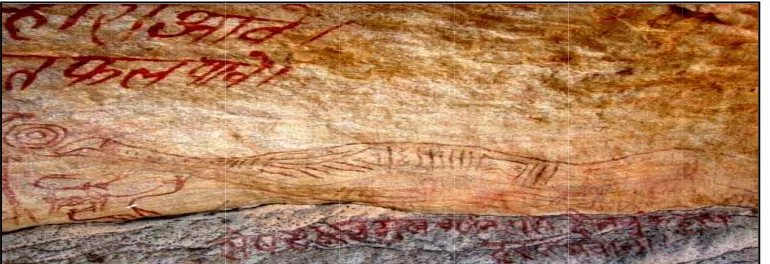

Similarly the discovery of the rock-shelters in Sehore in Mirzapur district, brought to light the presence of six giant mammals or quadrupeds (Fig. 5). The paintings were found in the ceilings and a few anthropomorphs in yellow colour were found at the basal and middle part of this shelter (Fig. 6). Profuse superimposition and use of different colour along with decorative patterns made it impossible for us to understand the type of animals individually.

Figure 5: Giant mammals or quadrupeds Figure 6: Anthropomorphs in yellow colour

through

208 Rock Art: Recent Researches and New Perspectives (Festschrift to Yashodhar Mathpal)

Only a deer and a bison’s head were prominent enough to understand and interpret the complicated effects of superimposition along with taphonomical alterations (Bednarik, 1994). The anthropomorphs were found to be executed in a separate part of the same shelter and all of these paintings seemed very old, in terms of superimposition, techno-stylistics and taphonomy. No vandalism was found here. This again reminds the fact that the contemporary villagers of the region leave meaningful traces of their

paintings pose significant amount of challenge to the localities in terms of interpretation and perception cognitive capacities only; when they can relate to the rock paintings in a way or other. When the

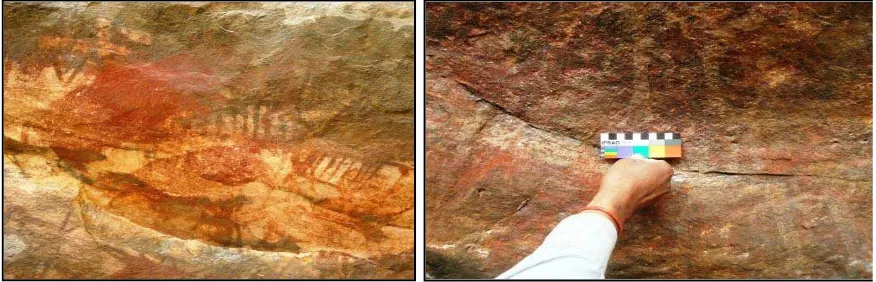

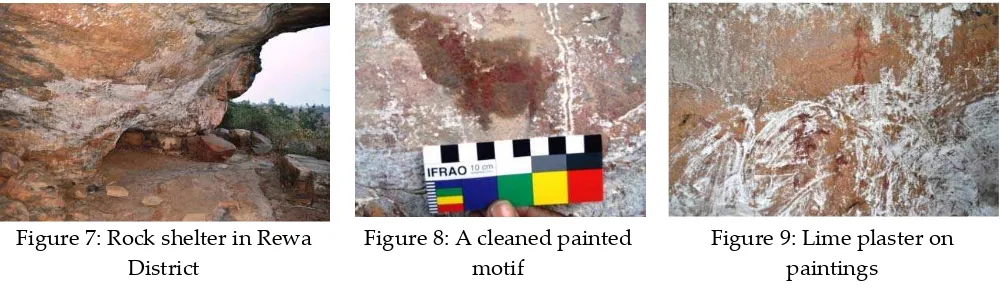

then perhaps they get frustrated and vandalize the painted collage indiscriminately and randomly without a pattern. Further evidences from the Rewa district would confirm this fact. It is equally important to understand what these motifs convey. There has been a tendency in Central Indian rock art, particularly in Mirzapur and Rewa to group the motifs, instead of identifying unique morphic and thematic elements intertwined within the superimposed panels (Pratap and Kumar, 2009). The nature of vandalisms, structure-function and corresponding effects have also been ignored thoroughly; which should have been incorporated to make sense of the entire rock art corpus including the landscape in the present day conditions. Profuse superimposition and presence of different kind of motifs with varying style, colour combinations and techniques represent the urgent need of categorization and classification of rock-shelter sites based on discreet parameters. In the case of Sehore, future work is tenable in the light of the recent discovery including the identification of these naturalistic cum decorative elements and comparison of the painted motifs with that of other shelters when the paintings invoke similarity. The last rock-shelter within this group is locally known as ‘Bhairo Baba ki Pahari’ in the Rewa district which has been highly vandalized and the first of its kind discovered and documented in this region (Fig.7).

Figure 7: Rock shelter in Rewa Figure 8: A cleaned painted Figure 9: Lime plaster on

District motif paintings

This rock-shelter represents different types of painted motifs like, anthropomorphsiii, therioanthropomorphsiv, marching animals, hunting scenes, stick like human figures, and other unidentified motifs. Unfortunately all these motifs are under a layer of modern day lime plaster. It is possible to clean the paintings using water, but it might deteriorate the state of the paintings as well

(Fig. 8). A few motifs were cleaned using natural water for the sake of documentation and to assess the

damage that had already been caused by the lime plaster to the rock art (Fig. 9). Local amateur rock art specialists and villagers who accompanied me with all these discoveries informed that ‘sadhusv’

209

Banerjee et al. 2014: 204-217

normally choose these locations away from the village areas and human interferences to reside on a long term basis. Undoubtedly, this has been the case for this specific rock-shelter, ‘Bhairo Baba ki Pahari’ where the religious practitioners have failed to understand the value of the prehistoric painted motifs and unintentionally vandalized the collage. Therefore, it is quite evident that lack of coherent knowledge about past societies and cultures poses a danger for the painted rock art sites in this region. Various forms of vandalisms either by local villagers, workers coming to the jungles for mining sandstone and collecting woods, groups of pastoralists entering the forested areas for grazing their animals or the sadhus actually residing in the rock-shelters; all are totally ignorant about the prehistoric paintings, archaeological sites and ancient anthropogenic deposits. Specifically rock-shelters like these, representing a wealth of data in terms of morphic patterns and number of painted motifs impart important clues to understand the cultural evolution within the local micro-area under study. Regional study, based on specific problem oriented research gets hampered when valuable sites with important sets of data get mutilated and vandalized.

The Issues of Conservation and Protection of Rock Art Sites

210 Rock Art: Recent Researches and New Perspectives (Festschrift to Yashodhar Mathpal)

211

Banerjee et al. 2014: 204-217

Identity Crisis and Identity Generation in Rock Art

212 Rock Art: Recent Researches and New Perspectives (Festschrift to Yashodhar Mathpal)

through rock art is another issue, where rock art being an agent of past memories, experiences and information create a sense of belongingness. A particular type of awareness, in terms of present day social context; that these are ancient forms of knowledge representing the interaction of past human societies and cultures is the fundamentals of present day socio-cultural identity and solidarity, particularly when the archaeological record is continuous. The protection, preservation and conservation of painted motifs enable humankind to respect and appreciate the evolution of social choice, decision making and ancient technologies. The variable developmental phases of ancient traditions in the form of rock paintings can be elucidated from the careful examination of superimpositions, chrono-stylistics, techno-stylistics and morphic variability within the same eco-geographical region. Rock art being powerful and particularly serving religious purposes in specific parts of India create and define identity for the local people. A form of art becomes a form of living tradition in the contemporary world (Imam, 2013). Phases of ancient knowledge systems get reinterpreted and welcomed into the present day belief systems and world views. In this way rock art can generate identity for itself and for the local people, when understood within the purview of present day conditioning and social setting, especially in Central Indian context. Rock art, when perceived categorically based on differential belief systems and/or is contextually misinterpreted; suffers from vandalisms and mutilations by the same people. Most of the Indian urban dwellers so far, have not taken serious interest in rock shelter archaeology and anthropology. However the scenario is gradually changing in India with increased government funding and social awareness. University students of various disciplines are more aware about their rich cultural heritage and some of them are working towards the protection and upkeep of both tangible and intangible cultural heritages in the Central provinces of India. New rock art sites are being discovered in Central Indian region by several scholars, researchers and government organizations. These are the preliminary steps towards identity generation, where the cultural heritage of a specific region receives renewed interest, in-depth scrutiny and revitalization. Indian archaeology on the other hand gets richer and richer through all these new discoveries of unique sets of data on rock art and in future through thorough scientific analyses of the new and old paintings; it can claim international reputation in rock shelter archaeology.

Conclusion

Central Indian rock art is one of the richest living cultural heritages on earth. From the prehistory to the contemporary the character, ramifications and manifestations of this extraordinary cultural resource has shown continuity, revival and rejuvenation. It incorporates the ever enigmatic puzzles of human evolution, migration, subsistence pattern, demic diffusion, palaeoenvironment, cognitive neuropsychology and finally the ways of lives of several human groups and races overtime in the Indian subcontinent. Recent decade has seen the discovery of many new rock art sites in the regions of Mirzapur and Rewa, where vandalism has been rampant, which sometimes defaced the painted rock canvas completely. The agencies of vandalism are yet unknown, but it may be concluded that ignorance about the prehistoric science and lifeways of past peoples among the localites and villagers is one of reasons of this unintentional but pernicious activity, which reflects major identity crisis. Other factors are lack of proper education and lack of overall interest in preserving and conserving the

213

Banerjee et al. 2014: 204-217

cultural heritage of the region. The content of rock paintings have been challenging enough for the local people, where the contents have been misinterpreted, solely based on dominant folklore and mythologies, prevalent in the region. The paintings and sometimes the entire site is vandalised due to this false conception and religious beliefs, deep rooted in the contemporary socio-cultural traditions. However, in some exceptional cases, discovery of new rock art sites in the recent past were welcomed by the villagers in the areas of Mirzapur and Rewa districts and they took initiatives to find out more such painted sites. A few of them on the basis of importance have been included in this paper to establish the role of new discovery, interpretation of the paintings (either prehistoric or historic) and vandalism within the purview of Indian rock-shelter archaeology and cultural heritage studies delineating the capacity of rock art involved with identity crisis and identity generation. Finally we observed a renewed and avid interest among the local people in the archaeological sites of the region, which would prove fruitful for Indian culture and heritage studies and research work in future in mainland India.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Archaeological Survey of India, Janpath, New Delhi, for providing all the necessary permissions to conduct field work in Central India. The first author is indebted to the people of Mirzapur and Rewa districts for their cordial help, hospitality and fruitful discussions about the paintings and rock-shelters. The authors extend their sincere gratitude to Professor Ajit Kumar for the invitation to contribute a research article in the Festschrift in the honor of Dr. Prof. Yashodhar Mathpal.

References

Banerjee, R and Srivastava, P.K. (2013). ‘Reconstruction of contested landscape: Detecting land cover transformation hosting cultural heritage sites from Central India using remote sensing’.

Land Use Policy, Vol.34, 193-203.

Banerjee, R.; Pike, A.W.G. and Verma, R.K. (2013). ‘Preliminary report on the newly discovered site of Uraihava, Mizapur District, India’. International Newsletter on Rock Art, 66, 4-9.

Bednarik, R. G. (1994). ‘A Taphonomy of Paleoart’. ANTIQUITY 68: 68-74.

Bednarik, R.; Kumar, G.; Watchman, A. and Roberts, R.G. (2005). ‘Preliminary Results of the EIP Project’. Rock Art Research, 22(2): 147-197.

Brown, P. (1923). ‘Notes on the prehistoric cave paintings at Raigarh’ in Prehistoric India. (Eds.) P. Mitra, pp: 245-255, Calcutta, Calcutta University.

Carleylle, A.C. (1883). ‘Notes on lately discovered sepulchral mounds, cairns, caves, cave paintings and stone implements’. Proceedings of the Asiatic society of Bengal. pp. 49-55.

Carleylle, A.C. (1899). ‘Cave paintings of the Kaimur Range’. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta.

214 Rock Art: Recent Researches and New Perspectives (Festschrift to Yashodhar Mathpal)

Chakraverty, S. (2009). ‘Interpreting Rock Art in India: A Holistic and Cognitive Approach’. XXIII

Valcamonica Symposium. pp. 94-107.

Chakraverty,S. (2003). ‘Rock Art Studies in India: A Historical Perspective’. The Asiatic Society, Kolkata.

Chandramouli, N. (2002). ‘Rock Art of South India’. Bharatiya Kala Prakashan, India.

Chandramouli, N. (2013). ‘Rock Art of Andhra Pradesh: A New Synthesis’. Aryan Books International, India.

Cockburn, J. (1883a). ‘On the recent existence of the Rhinoceros indicus in the Northwestern Provinces’.

Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 52 (2): 56-64.

Cockburn, J. (1883b). ‘A short account of the petrographs in the caves and rockshelters of the Kaimur range in the Mirzapur District’. Proceedings of the Asiatic society of Bengal. Pp. 125-126.

Cockburn, J. (1888). ‘On Palaeolithic implements from the drift gravels of the Singrauli Basin, South Mirzapur’. Journal of the Anthropological institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 17: 57-65.

Cockburn, J. (1899). ‘Cave drawings in the Kaimur Range, Northwest Provinces’. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, January. 31, 89-97.

Drake-Brockman, D. (1911). ‘Mirzapur: A Gazetteer’. Superintendent, Government Press, United Provinces.

Dubey-Pathak, M. (2013). ‘The Dharkundi Rock Art Sites in Central India’. International Newsletter on Rock Art, 66, 10-17.

Haak, W.; Brandt, G.; de Jong, H.; Meyer, C.; Ganslmeier, R.; Heyd, V.; Hawkesworth, C.; Pike, A.W.G.; Meller, H. and Alt, K. (2008). ‘Ancient DNA, strontium isotopes and osteological analyses shed light on social and kinship organization of the later stone age’. Proceedings of

the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105, (47), 18226-18231.

Imam, B. (2013). ‘The historical perspective of prehistory through a study of Meso-Chalcolithic rock art and contemporary tribal mural paintings in Jharkhand, Eastern North India’, XXV Valcamonica Symposium.

Imam, J. (2013). ‘Contemporary Tana Bhagat Puja to a Meso-Chalcolithic rock art site at the Thethangi, Chatra District, North Jharkhand, East Central India’, XXV Valcamonica Symposium.

Jayaswal, V. (1983). ‘Excavation of a Painted Rock-Shelter at Laharia-Dih, Mirzapur District’, In Singh, P. and Prasad Singh, T (Eds.) Bharati, No.1 pp. 127 – 133.

Khandelwal, K and Chandra, M. (1961). ‘New Documents of Indian Paintings’, Lalit Kala, No. 10. Luard, C. E. (1908). ‘The Central India state gazetteer series’, Thacker, Spink.

Macroscopic and Biomolecular Approach’ , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham. E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3593/

Malla, B.L.(1999). ‘Conservation and Management of Rock Art Sites’, In Conservation of Rock Art, (EDs) Dr. B. L. Malla, IGNCA.

Mathpal, Y. (1984). ‘Prehistoric Rock Paintings of Bhimbetka’. New Delhi, Avinav Publications. Mccarrison, K. E. (2012). ‘Exploring Prehistoric Tuberculosis in Britain: A Combined

Mirzapur’. Rock Art of India.

215

Banerjee et al. 2014: 204-217

Pandey, S.M. (1987). ‘The Hindi Oral Epic Lorikayan’. Sahitya Bhawan Private.

Pratap, A. & Kumar, N. (2009). ‘Painted rockshelters at Wyndham Falls, Mirzapur, Uttar Pradesh, India’. Antiquity, Vol 83, Issue, 321.

Ravindran, T.R.; Arora, A.K.; Singh, M. and Ota, S.B. (2012). ‘On- and off-site Raman study of rock-shelter paintings at world-heritage site of Bhimbetka’. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI 10.1002/jrs.4148.

Renfrew, A.C. and Morley, I.R. (2009). ‘Becoming Human: Innovation in Prehistoric Material and Spiritual Culture’. Cambridge University Press,Cambridge.

Richards, MP. (2002). ‘A brief review of the archaeological evidence for Palaeolithic and Neolithic subsistence’. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 56.

Rivett-Carnac, J.H. (1877). ‘Rough notes on some ancient sculpturing on rock rocks in Kumaon, similar to those found on Monoliths and rocks in Europe’. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol 46, No.1, pp 1-15.

Rivett-Carnac, J.H. (1879). ‘Prehistoric remains in Central India’. Journal of Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. 48, No. 1, pp. 01-16.

Taçon, P.S.C et al. (2013). ‘Mid-Holocene age obtained for nested diamond pattern petroglyph in the Billasurgam Cave complex, Kurnool District, southern India’. Journal of Archaeological Science, 40 (4): 1787-1796.

Tewari, R and Bharti. (1988). ‘Lorikayan scene in rock paintings’. Bulletin of Museum and Archaeology, No. 41, pp.97-102.

Tewari, R. (1990). ‘Rock Paintings of Mirzapur. Monograph on the rock paintings of district Mirzapur (including newly created district of Sonbhadra)’, U.P. State Archaeological Organisation, Lucknow.

Tewari, R. (2011). ‘.… Given another life ….’. Man and Environment XXXVI(1): 14-30.

Tewari, R.; Singh, P.K.; Srivastava, R.K. and Singh, G.C. (1999). ‘Archaeological Investigations in District Mirzapur, Uttar Pradesh’. Prāgdhārā: journal of the UP State Archaeological Organisation: 163.

Tiwari, S. K. (2000). ‘Riddles of Indian rockshelter paintings’. New Delhi, Swarup and Sons.

Varma, R. K. (1964). ‘Stone age cultures of Mirzapur’. Unpublished D. Phil Thesis, University of Allahabad.

Varma, R. K. (1981). ‘The Mesolithic cultures of India’. Puratattva, 13-14: 27.

Varma, R. K. (1984). ‘The Rock Art of Southern Uttar Pradesh with special Reference to Varma, R. K. (1986). ‘The Mesolithic Age in Mirzapur’. Allahabad.

Varma, R. K. (2008). ‘Beginnings of Agriculture in the Vindhya-Ganga Region’. History of Agriculture in

India, Up to C. 1200 AD 5: 31.

Varma, R. K. (2012). ‘Rock Art of Central India: North Vindhyan Region’. Aryan Books International, New Delhi.

Varma, R.K. ( 2002). ‘Mesolithic technology’. In Misra, VD and Pal, JN (Eds.) Mesolithic India. Allahabad

University, Allahabad. pp. 347-355.

216 Rock Art: Recent Researches and New Perspectives (Festschrift to Yashodhar Mathpal)

Waterman, A. J. (2012). ‘Marked in life and death: identifying biological markers of social differentiation in late prehistoric Portugal’. PhD diss., University of Iowa, http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/3007.

Endnote

i A particular type of alphabet predominant in India, Nepal, Tibet and is written from left to right. ii A hymn from the Rigvedic text named after the deity Savitr or Sāvitrī.

iii Rock paintings that represent human forms, but not totally human like motifs.

iv Rock paintings that represent both human and animal elements, like human body with a deer head, In some

ethnic indigenous tribes of India, the animal head might reveal particular types of masks.

v According to Hindu religion a Sadhu is a holy man, a wondering ascetic who denounced material cravings,

sensual gratifications, attachements and aims to attain complete liberation by means of spiritual practices.