Breastfeeding and

Human Lactation,

Third Edition

Jan Riordan, EdD, RN, IBCLC, FAAN

JONES AND BARTLETT PUBLISHERS

TeAM

YYePG

Jones and Bartlett Series in Breastfeeding/Human Lactation

Case Studies in Breastfeeding: Problem-Solving Skills and Strategies,Cadwell/Turner-Maffei

Clinical Lactation: A Visual Guide, Auerbach

Coach’s Notebook: Games and Strategies for Lactation Education, Smith

Comprehensive Lactation Consultant Exam Review, Smith

Core Curriculum for Lactation Consultant Practice, Walker, editor

Counseling the Nursing Mother: A Lactation Consultant’s Guide, Third Edition,Lauwers/Shinskie

Impact of Birthing Practices on Breastfeeding: Protecting the Mother and Baby Continuum,Kroeger with Smith

The Lactation Consultant in Private Practice: The ABCs of Getting Started,Smith

Reclaiming Breastfeeding for the United States: Protection, Promotion and Support, Cadwell

Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding: An 18 Hour Interdisciplinary Breastfeeding Management Course for the United States, Cadwell/Turner-Maffei

Breastfeeding and Human

Lactation

Third Edition

Jan Riordan, EdD, RN, IBCLC, FAAN

Professor

School of Nursing

Wichita State University

Wichita, Kansas

Lactation Consultant

Via Christi Regional Medical Center

St. Joseph Campus

World Headquarters

Jones and Bartlett Publishers 40 Tall Pine Drive

Sudbury, MA 01776 978-443-5000 info@jbpub.com www.jbpub.com

Copyright © 2005 by Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Inc. Cover image © InJoy Productions, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Breastfeeding and human lactation / [edited by] Jan Riordan.— 3rd ed. p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7637-4585-5 (hardcover)

1. Breast feeding. 2. Lactation.

[DNLM: 1. Breast Feeding. 2. Infant Nutrition. 3. Lactation. 4. Milk, Human. WS 125 B8293 2004] I. Riordan, Jan.

RJ216.B775 2004

649'.33—dc22 2003022400

Printed in the United States of America

08 07 06 05 04 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Jones and Bartlett Publishers Canada 2406 Nikanna Road

Mississauga, ON L5C 2W6 CANADA

Jones and Bartlett Publishers International

Barb House, Barb Mews London W6 7PA UK

Chief Executive Officer:Clayton Jones Chief Operating Officer:Don W. Jones, Jr. President of Jones and Bartlett Higher Education and Professional Publishing:Robert W. Holland, Jr. V.P., Design and Production:Anne Spencer V.P., Manufacturing and Inventory Control: Therese Bräuer

V.P. of Sales and Marketing:William Kane Acquisitions Editor:Penny M. Glynn Production Manager:Amy Rose

Editorial Assistant: Amy Sibley

Associate Production Editor:Jenny L. McIsaac Director of Marketing:Alisha Weisman Marketing Manager:Edward McKenna Manufacturing Buyer:Amy Bacus Cover Design:Anne Spencer

Composition:Modern Graphics Incorporated Printing and Binding:Malloy Inc.

S E C T I O N 1

H

I STOR ICAL AN D

W

OR K

P

E R S P ECTIVE S

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

Preface xxi Chapter Authors xxiv

Acknowledgements xxiii

C H A P T E R 1

Tides in Breastfeeding Practice

3

Evidence About Breastfeeding Practices 3

Large-Scale Surveys 3

Other Evidence 4

The Biological Norm in Infant Feeding 5

Early Human Evolution 5

Early Breastfeeding Practices 5

The Replacement of Maternal Breastfeeding 5

Wet-Nursing 5

Hand-Fed Foods 6

Timing of the Introduction of Hand-Feeding 7

Technological Innovations in

Infant Feeding 8

The Social Context 8

The Technological Context 9

The Role of the Medical Community 9

The Prevalence of Breastfeeding 12

United States, England, and Europe 12

Developing Regions 13

The Cost of Not Breastfeeding 15

Health Risks of Using Manufactured

Infant Milks 16

Economic Costs of Using Manufactured

Infant Milks 16

The Promotion of Breastfeeding 18

Breastfeeding Promotion in the

United States 19

International Breastfeeding Promotion 20

Private Support Movements 23

Summary 24

Key Concepts 25

Internet Resources 26

References 27

C H A P T E R 2

Work Strategies and the

Lactation Consultant

31

History 31

Do Lactation Consultants Make a

Difference? 32

Certification 32

Getting a Job as a Lactation Consultant 35

Interviewing for a Job 36

Gaining Clinical Experience 36

LC Education 37

Lactation Programs 38

Workload Issues 41

Developing a Lactation Program 41

Marketing 44

The Unique Characteristics of Counseling

Breastfeeding Women 44

Roles and Responsibilities 45

Stages of Role Development 46

Lactation Consultants in the

Community Setting 47

Medical Office 47

Lactation Consultants and

Volunteer Counselors 48

Networking 48

Reporting and Charting 49

Clinical Care Plans 50

Legal and Ethical Considerations 51

viii Breastfeeding and Human Lactation

Reimbursement 53

Insurance and Third-Party Payment 53

Coding 56

Private Practice 57

The Business of Doing Business 57

Payment and Fees 58

Partnerships 59

Summary 60

Key Concepts 61

Internet Resources 62

References 62

S E C T I O N 2

A

NATOM ICAL AN D

B

IOLOG ICAL

I

M P E RATIVE S

C H A P T E R 3

Anatomy and Physiology

of Lactation

67

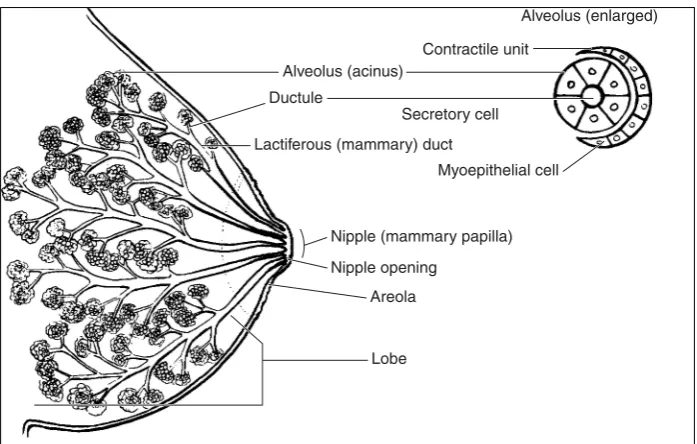

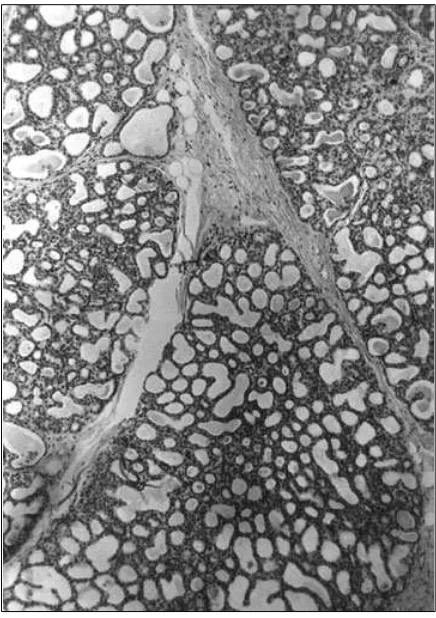

Mammogenesis 67

Breast Structure 69

Variations 72

Pregnancy 72

Lactogenesis 73

Delay in Lactogenesis 74

Hormonal Influences 74

Progesterone 75

Prolactin 75

Cortisol 77

Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone 77

Prolactin-Inhibiting Factor 77

Oxytocin 78

Milk Production 79

Autocrine Versus Endocrine 79

Galactopoiesis 80

Galactorrhea 80

Clinical Implications: Mother 80

Breast Assessment 80

Classification of Nipple Function 82

Concepts to Practice 82

Newborn Oral Development 83

Suckling 85

Breathing and Suckling 87

Frequency of Feedings 89

Summary 90

Key Concepts 90

References 92

C H A P T E R 4

The Biological Specificity

of Breastmilk

97

Milk Synthesis and Maturational Changes 98

Energy, Volume, and Growth 98

Caloric Density 99

Milk Volume and Storage Capacity 100 Differences in Milk Volume

Between Breasts 102

Infant Growth 103

Nutritional Values 103

Fat 103

Lactose 105

Protein 106

Vitamins and Micronutrients 106

Minerals 108

Preterm Milk 110

Anti-infective Properties 111

Gastroenteritis and Diarrheal Disease 111

Respiratory Illness 112

Otitis Media 114

Contents ix

Chronic Disease Protection 115

Childhood Cancer 116

Allergies and Atopic Disease 116

Asthma 117

The Immune System 117

Active Versus Passive Immunity 117

Cells 118

Antibodies/Immunoglobulins 119

Nonantibody Antibacterial Protection 120 Anti-inflammatory and Immunomodulating

Components 121

Bioactive Components 122

Enzymes 122

Growth Factors and Hormones 123

Taurine 124

Implications for Clinical Practice 124

Summary 126

Key Concepts 126

Internet Resources 127

References 128

Appendix 4-A: Composition of Human Colostrum and Mature Breastmilk 136

C H A P T E R 5

Drug Therapy

and Breastfeeding

137

The Alveolar Subunit 138

Drug Transfer into Human Milk 139

Passive Diffusion of Drugs into Milk 140

Ion Trapping 141

Molecular Weight 141

Lipophilicity 142

Milk/Plasma Ratio 142

Maternal Plasma Levels 142

Bioavailability 143

Drug Metabolites 143

Calculating Infant Exposure 143

Unique Infant Factors 144

Maternal Factors 146

Minimizing the Risk 146

Effect of Medications on Milk Production 146

Drugs That May Inhibit Milk Production 146 Drugs That May Stimulate

Milk Production 148

Herbs 149

Review of Selected Drug Classes 149

Analgesics 149

Antibiotics 150

Antihypertensives 153

Psychotherapeutic Agents 153

Corticosteroids 157

Thyroid and Antithyroid Medications 157

Drugs of Abuse 158

Radioisotopes 159

Radiocontrast Agents 159

Summary 161

Key Concepts 162

Internet Resources 162

References 162

C H A P T E R 6

Viruses and Breastfeeding

167

HIV and Infant Feeding 167

Exclusive Breastfeeding 168

What We Know 168

Treatment and Prevention 170

Health-Care Practitioners 171

Counseling 171

Herpes Simplex Virus 172

Chickenpox/Varicella 173

x Breastfeeding and Human Lactation

Rubella 176

Hepatitis B 176

Hepatitis C 176

Human Lymphotropic Virus 177

West Nile Virus 177

Implications for Practice 178

Summary 179

Key Concepts 179

Internet Resources 180

References 181

S E C T I O N 3

P

R E NATAL

, P

E R I NATAL

,

AN D

P

OSTNATAL

P

E R IODS

C H A P T E R 7

Perinatal and

Intrapartum Care

185

Breastfeeding Preparation 185

Early Feedings 186

Feeding Positions 191

Latch-on and Positioning Techniques 191

The Infant Who Has Not Latched-On 192

Plan for the Baby Who Has Not

Latched-On Yet 194

Establishing the Milk Supply 194

Assessment of the Mother’s

Nipples and Breasts 196

Baby Problems That May Cause

Difficulty with Latch-on 196

The 34 to 38 “Weeker” 197

Feeding Methods 198

Cup-Feeding 198

Finger-Feeding 199

Nipple Shields 200

Hypoglycemia 201

Cesarean Births 204

Breast Engorgement 205

Breast Edema 206

Hand Expression 207

Clinical Implications 209

Breastfeeding Assessment 209

Discharge Planning 210

Basic Feeding Techniques 210

Signs That Intervention Is Needed 211

Discharge 211

Summary 212

Key Concepts 212

Internet Resources 214

References 214

C H A P T E R 8

Postpartum Care

217

Hydration and Nutrition in the Neonate 217

Signs of Adequate Milk Intake 218 Milk Supply––Too Much or Too Little 218 Temporary Low Milk Supply or

Delayed Lactogenesis 220

Effect of Pharmaceutical Agents on

Milk Supply 220

Too Much Milk 221

Nipple Pain 221

Treatments for Painful Nipples 225

Nipple Creams and Gels 225

Engorgement + Milk Stasis = Involution 228

Breast Massage 228

Clothing, Leaking, Bras, and

Contents xi

Infant Concerns 230

Pacifiers 230

Stooling Patterns 231

Jaundice in the Newborn 232

Breast Refusal and Latching Problems 232

Later Breast Refusal 234

Crying and Colic 234

Multiple Infants 236

Full-Term Twins or Triplets 237

Preterm or Ill Multiples 237

Putting It All Together 238

Partial Breastfeeding and Human

Milk Feeding 239

Breastfeeding During Pregnancy 240

Clinical Implications 241

Summary 242

Key Concepts 242

Internet Resources 242

References 243

C H A P T E R 9

Breast-Related Problems

247

Nipple Variations 247

Inverted or Flat Nipples 247

Absence of Nipple Pore Openings 248

Large or Elongated Nipples 248

Plugged Ducts 248

Mastitis 250

Treatment for Mastitis 251

Types of Mastitis 252

Breast Abscess 254

Breast and Nipple Rashes, Lesions, and

Eczema 254

Candidiasis (Thrush) 255

Treatment 256

Breast Pain 260

Vasospasm 260

Milk Blister 261

Mammoplasty 261

Breast Reduction 261

Mastopexy 263

Breast Augmentation 263

Breast Lumps and Surgery 265

Galactoceles 266

Fibrocystic Disease 267

Bleeding from the Breast 267

Breast Cancer 268

Lactation Following Breast Cancer 269

Clinical Implications 270

Summary 271

Key Concepts 271

Internet Resources 273

References 273

C H A P T E R 1 0

Low Intake in the Breastfed

Infant: Maternal and

Infant Considerations

277

Factors That Influence Maternal

Milk Production 277

Normal Milk Intake and Rate of Gain 279

US Growth Curves 280

Current Growth Curves Still

Underrepresent Breastfeeding 280

Low Intake and Low Milk Supply: Definit-ions and Incidence of Occurrence 282

Confusing Terminology and

Nonstandardized Research 282

The Infant’s Presentation 283

The Mother’s Presentation 285

Abnormal Patterns of Growth: The Baby

Who Appears Healthy 286

Inadequate Weight Gain in the

First Month 286

xii Breastfeeding and Human Lactation

Oral-Motor Dysfunction

(Ineffective Suckling) 286

Gastroesophageal Reflux/Cow Milk

Allergy/Oversupply 290

Nonspecific Neurological Problems 291 Ankyloglossia (Tight Frenulum,

Tongue-Tie) 291

Abnormal Patterns of Growth:

The Baby with Obvious Illness 292

Maternal Considerations:

The Mother Who Appears Healthy 293

Delayed Lactogenesis 293

Stress 293

Inverted Nipples 294

Nipple Shields 294

Medications and Substances 294

Hormonal Alterations 294

Breast Surgery 295

Insufficient Glandular Development

of the Breast 295

Psychosocial Factors 296

Maternal Nutrition 296

Maternal Considerations:

Obvious Illness 296

History, Physical Exam, and

Differential Diagnosis 296

History 296

Physical Examination 296

Differential Diagnosis 297

Clinical Management 297

Determining the Need

for Supplementation 297

Intervention 297

Reducing the Amount

of Supplementation 300

Family and Peer Support 300

When Maternal Milk Supply Does

Not Increase 300

Special Techniques for Management of

Low Intake or Low Supply 300

Breast Massage 300

Switch Nursing 300

Feeding-Tube Device 301

Test Weighing 303

Galactagogues 303

Hindmilk 304

Summary 305

Key Concepts 306

Internet Resources 307

References 307

C H A P T E R 1 1

Jaundice and the

Breastfed Baby

311

Neonatal Jaundice 312

Assessment of Jaundice 313

Postnatal Pattern of Jaundice 314

Breastmilk Jaundice 314

Breast-Nonfeeding Jaundice 314

Bilirubin Encephalopathy 316

Evaluation of Jaundice 316

Diagnostic Assessment 317

Management of Jaundice 318

Key Concepts 319

Internet Resources 320

References 320

C H A P T E R 1 2

Breast Pumps and

Other Technologies

323

Concerns of Mothers 323

Stimulating the Milk-Ejection Reflex 324

Hormonal Considerations 328

Prolactin 328

Clinical Implications 329

Oxytocin 330

Pumps 330

Contents xiii

Compression 331

The Evolution of Pumps 331

A Comparison of Pumps 332

Manual Hand Pumps 333

Battery-Operated Pumps 335

Electric Pumps 336

Simultaneous and/or

Sequential Pumping 338

Flanges 338

Miscellaneous Pumps 342

Pedal Pumps 342

Clinical Implications Regarding

Breast Pumps 342

When Pumps Cause Problems 345

Sample Guidelines for Pumping 345

Common Pumping Problems 347

Nipple Shields 349

Review of Literature 350

Types of Shields 351

Shield Selection and Instructions 351

Weaning from the Shield 352

Responsibilities 352

Breast Shells 354

Feeding-Tube Devices 355

Situations for Use 355

Summary 357

Key Concepts 358

Internet Resources 361

References 361

Appendix 12-A: Manufacturers/

Distributors of Breast Pumps 365

C H A P T E R 1 3

Breastfeeding the

Preterm Infant

367

Suitability of Human Milk for Preterm

Infants 367

Mothers of Preterm Infants 368

Rates of Breastfeeding Initiation and

Duration 370

Research-Based Lactation Support

Services 370

The Decision to Breastfeed 370

Facilitating an Informed Decision 370 Alternatives to Exclusive, Long-Term

Breastfeeding 370

Models for Hospital-Based Lactation

Support Services 371

Initiation of Mechanical Milk Expression 372

Principles of Milk Expression 372

Selecting a Breast Pump 372

Milk-Expression Technique 373

Milk Expression Schedule 374

Written Pumping Records 374

Maintaining Maternal Milk Volume 376

Expressed Milk Volume Guidelines 376

Preventing Low Milk Volume 376

Skin-to-Skin (Kangaroo) Care 377

Evidence-Based Guidelines for Milk

Collection, Storage, and Feeding 378

Guidelines for Collection and Storage

of Expressed Mother’s Milk (EMM) 378 Preparing Expressed Mother’s Milk

for Infant Feeding 379

Special Issues Regarding the Feeding

of EMM 380

Volume Restriction Status 382

Commercial Nutritional Additives 382

Hindmilk Feeding 382

Methods of Milk Delivery 383

Maternal Medication Use 383

Feeding at Breast in the NICU 384

Suckling at the Emptied Breast 384 The Science of Early Breastfeeding 385 Progression of In-Hospital Breastfeeding 390 Milk Transfer During Breastfeeding 390

Discharge Planning for

Postdischarge Breastfeeding 396

Getting Enough: Determining the Need

xiv Breastfeeding and Human Lactation

Methods to Deliver Extra Milk Feedings

Away from the Breast 398

Postdischarge Breastfeeding Management 398

Summary 399

Key Concepts 399

Internet Resources 400

References 401

Appendix 13-A: The Preterm Infant

Breastfeeding Behavior Scale (PIBBS) 407

C H A P T E R 1 4

Donor Human Milk Banking

409

Defining Donor Milk Banking 409

A Brief History of Human Milk Banking 409

Foundations of Donor Human Milk

Banking: Pre-1975 409

Donor Human Milk Banking in the

United States: Post-1975 410

Potential Hazards of Informal Sharing of

Human Milk 411

Donor Human Milk Banking Beyond

North America 412

The Impact of Culture on Donor

Milk Banking 413

The Benefits of Banked Donor

Human Milk 413

Species Specificity 413

Ease of Digestion 413

Promotion of Growth, Maturation,

and Development of Organ Systems 414

Immunological Benefits 414

Clinical Uses 414

Distribution of Banked Donor Milk:

Setting Priorities 414

Classifying Clinical Uses: Is Donor

Milk Food or Medicine? 415

Current Practice 420

Donor Selection and Screening 420

Collection 422

Pasteurization 422

Packaging and Transport 425

Costs of Banked Donor Milk 425

Policy Statements Supporting the

Use of Banked Donor Human Milk 425

Summary 426

Key Concepts 427

Internet Resources 427

References 427

Appendix 14-A: Storage and Handling

of Expressed Human Milk 432

S E C T I O N 4

B

EYON D

P

OSTPARTU M

C H A P T E R 1 5

Maternal Nutrition

During Lactation

437

Maternal Caloric Needs 438

Maternal Fluid Needs 439

Weight Loss 439

Exercise 440

Calcium Needs and Bone Loss 441

Vegetarian Diets 442

Dietary Supplements 442

Foods That Pass Into Milk 443

Caffeine 443

Food Flavorings 443

Allergens in Breastmilk 443

The Goal of the Maternal Diet

Contents xv

Nutrition Basics 446

Energy 446

Macronutrients 447

Carbohydrates 447

Protein 447

Fat 448

Micronutrients 448

Vitamins 448

Minerals 449

Clinical Implications 449

Summary 453

Key Concepts 453

Internet Resources 454

References 454

C H A P T E R 1 6

Women’s Health

and Breastfeeding

459

Alterations in Endocrine and

Metabolic Functioning 459

Diabetes 459

Thyroid Disease 461

Pituitary Dysfunction 462

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome 462

Theca Lutein Cysts 462

Cystic Fibrosis 463

Acute Illness and Infections 463

Tuberculosis 464

Group B Streptococcus 464

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding 465

Maternal Immunizations 465

Surgery 465

Donating Blood 466

Relactation 467

Induced Lactation 467

Domperidone, Metoclopramide,

and Sulpride 468

Autoimmune Diseases 470

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus 470

Multiple Sclerosis 471

Rheumatoid Arthritis 471

Physically Challenged Mothers 472

Seizure Disorders 473

Headaches 475

Postpartum Depression 476

Clinical Implications 477

Medications and Herbal Therapy

for Depression 478

Support for the Mother with

Postpartum Depression 480

Asthma 480

Smoking 480

Poison Ivy Dermatitis 481

Diagnostic Studies Using Radioisotopes 481

The Impact of Maternal Illness

and Hospitalization 482

Summary 482

Key Concepts 483

Internet Resources 484

References 484

C H A P T E R 1 7

Maternal Employment

and Breastfeeding

487

Why Women Work 487

Historical Perspective 488

The Effect of Work on Breastfeeding 488

Strategies to Manage Breastfeeding

and Work 489

Prenatal Planning and Preparation 489

Return to Work 491

Hand Expression and Pumping 492

Human Milk Storage 493

Fatigue and Loss of Sleep 496

Maintaining an Adequate Milk Supply 496

xvi Breastfeeding and Human Lactation

Workplace Strategies 497

Lactation Programs in Work Sites 498

The Employer’s Perspective 500

Community Strategies 501

Health-Care Providers and

Lactation Consultants 501

Breastfeeding Support Groups 501

National and International Strategies 501

Legislative Support and

Public Advocacy 501

International Labour Organization 503

Clinical Implications 503

Summary 505

Key Concepts 506

Internet Resources 507

Other Resources 507

References 507

C H A P T E R 1 8

Child Health

509

Developmental Outcomes and Infant

Feeding 509

Growth and Development 511

Physical Growth 511

Weight and Length 512

Senses 513

Reflexes 514

Levels of Arousal 514

Theories of Development 514

Nature Versus Nurture 514

Social Development 517

Language and Communication 517

Attachment and Bonding 520

Temperament 523

Stranger Distress 523

Separation Anxiety 523

Clinical Implications 525

Immunizations 525

Vitamin D and Rickets 527

Dental Health and Orofacial

Development 527

Solid Foods 528

Introducing Solid Foods 528

Choosing the Diet 529

Choosing Feeding Location 531

Delaying Solid Foods 531

Obesity 532

Co-Sleeping 532

Long-Term Breastfeeding 533

Weaning 533

Implications for Practice 534

Summary 535

Key Concepts 535

Internet Resources 536

References 536

C H A P T E R 1 9

The Ill Child:

Breastfeeding Implications

541

Team Care for the Child with

Feeding Difficulties 541

Feeding Behaviors of the Ill Infant/Child 541

What to Do If Weight Gain

Is Inadequate 544

What to Do When Direct Breastfeeding

Is Not Sufficient 544

Alternative Feeding Methods 546

Care of the Hospitalized Breastfeeding

Infant/Child 548

Home from the Hospital:

The Rebound Effect 550

Perioperative Care of the Breastfeeding

Infant/Child 551

Contents xvii

Care of Children with

Selected Conditions 552

Infection 552

Gastroenteritis 552

Respiratory Infections 554

Pneumonia 555

Bronchiolitis 555

Respiratory Syncytial Virus 556

Otitis Media 556

Meningitis 556

Alterations in Neurological Functioning 557

Down Syndrome or Trisomy 21 560

Neural Tube Defects 560

Hydrocephalus 561

Congenital Heart Disease 561

Oral/Facial Anomalies 563

Cleft Lip and Palate 563

Pierre Robin Sequence 566

Choanal Atresia 568

Gastrointestinal Anomalies

and Disorders 568

Esophageal Atresia/Tracheoesophageal

Fistula 568

Gastroesophageal Reflux 569

Pyloric Stenosis 571

Imperforate Anus 571

Metabolic Dysfunction 571

Phenylketonuria 572

Galactosemia 572

Congenital Hypothyroidism 574

Type I Diabetes 575

Celiac Disease 575

Cystic Fibrosis 575

Allergies 576

Food Intolerance 579

Lactose Intolerance 579

Psychosocial Concerns 579

Family Stress 579

Coping with Siblings 581

Chronic Grief and Loss 581

The Magic-Milk Syndrome 581

The Empty Cradle...When a Child Dies 582

Caring for Bereaved Families 582

Summary 583

Key Concepts 583

Internet Resources 584

References 585

C H A P T E R 2 0

Infant Assessment

591

Perinatal History 591

Gestational Age Assessment 591

The New Ballard Score 594

Indicators of Effective Breastfeeding

and Assessment Scales 598

Breastfeeding Behaviors

and Indicators 598

Breastfeeding Scales and Tools 598 Summary of Breastfeeding

Assessment Scales 600

Physical Assessment 600

Transitional Assessment 600

Skin 604

Birthmarks 605

Head 606

Ears/Eyes 606

Nose 607

Mouth 607

Neck 608

Chest 608

Abdomen 609

Genitalia 609

Back and Spine 609

Extremities 609

Elimination 610

Behavioral Assessment 611

Sleep-Wake States 614

Neurobehavioral Cues and Reflexes 614

Summary 616

Key Concepts 616

xviii Breastfeeding and Human Lactation

Appendix 20-A: Infant Breastfeeding

Assessment Tool (IBFAT) 618

Appendix 20-B: LATCH

Assessment Tool 618

Appendix 20-C: Mother-Baby

Assessment Scale 619

Appendix 20-D: Via Christi Breastfeeding

Assessment Tool 620

C H A P T E R 2 1

Fertility, Sexuality,

and Contraception

During Lactation

621

Fertility 621

The Demographic Impact

of Breastfeeding 621

Mechanisms of Action 622

Lactational Amenorrhea 623

The Suckling Stimulus 624

The Repetitive Nature of the Recovery

of Fertility 628

The Bellagio Consensus 630

Sexuality 632

Libido 632

Sexual Behavior During Lactation 637

Contraception 639

The Contraceptive Methods 639

Clinical Implications 645

Summary 647

Key Concepts 647

References 648

S E C T I O N 5

S

OCIOCU LTU RAL AN D

R

E S EARCH

I

SS U E S

C H A P T E R 2 2

Research, Theory,

and Lactation

655

Theories Related to Lactation Practice 655

Maternal Role Attainment Theory 656 Parent-Child Interaction Model 656 Bonding and Attachment Theory 657 Theory of Darwinian and

Evolutionary Medicine 657

Self-Care Theory 658

Self-Efficacy Theory 658

Theory of Planned Behavior and

Theory of Reasoned Action 658

Types of Research Methods 659

Qualitative Methods 659

Quantitative Methods 660

Additional Methods and Approaches

for Breastfeeding Research 662

Elements of Research 663

Research Problem and Purpose 663

Variables, Hypotheses, and

Operational Definitions 665

Review of Literature 667

Protection of the Rights of Human

Subjects 667

Method 668

Data Analysis 669

Application of Methods to

Qualitative Approaches 669

Sampling 669

Data Collection 670

Data Analysis 670

Trustworthiness of Qualitative Research 671

Application of Methods to

Quantitative Approaches 671

Sampling and Sample Size 671

Data Collection 672

Reliability and Validity 672

Data Analysis 674

Results, Discussion, Conclusions,

and Dissemination 677

Contents xix

Using Research in Clinical Practice 680

Perspectives of Research Methodologies 680

Positivist and Postpositive Perspective 681 Naturalistic, Humanistic, or

Interpretive Perspective 681

Critical or Emancipatory Perspective 681

Summary 682

Key Concepts 683

Internet Resources 684

References 684

Appendix 22-A: Research Terms 687

C H A P T E R 2 3

Breastfeeding Education

689

Educational Programs 689

Distance Learning and Web Courses 690

Learning Principles 690

Adult Education 691

Curriculum Development 692

Parent Education 692

Prenatal Education 694

Early Breastfeeding Education 694

Continuing Support for

Breastfeeding Families 697

How Effective Is

Breastfeeding Education? 697

Teaching Strategies 698

Small Group Dynamics 700

Multimedia Presentations 700

Slides 701

Transparencies 701

Television, Videotapes, and DVDs 701

Compact Discs 702

Educational Materials 702

Education for At-Risk Populations 703

Adolescents 704

Older Parents 705

Educational Needs and Early Discharge 706

Continuing Education 706

Objectives and Outcomes 707

The Team Approach 708

Childbirth Educators 708

Nurses 708

Lactation Consultants 709

Physicians 709

Dietitians 709

Community Support Groups 709

Summary 709

Key Concepts 710

Internet Resources 711

References 711

C H A P T E R 2 4

The Cultural Context

of Breastfeeding

713

The Dominant Culture 714

Ethnocentrism Versus Relativism 714

Assessing Cultural Practices 715

Language Barriers 715

The Effects of Culture on Breastfeeding 716

Rituals and Meaning 719

Colostrum 719

Sexual Relations 719

Wet-Nursing 720

Other Practices 720

Contraception 720

Infant Care 721

Maternal Foods 722

“Hot” and “Cold” Foods 722

Herbs and Galactogogues 723

Weaning 723

Types of Weaning 724

Implications for Practice 725

Summary 726

xx Breastfeeding and Human Lactation

Internet Resources 727

References 727

C H A P T E R 2 5

Families

729

Family Forms and Functions 729

Family Theory 730

Social Factors that Influence

Breastfeeding 731

Fathers 733

The Adolescent Mother 736

The Low-Income Family 737

Lack of Information 737

Hospital Practices 738

The Importance of Peer Counselors 739

The Downside of Family Experience 739

Violence 740

Childhood Sexual Abuse 741

Summary 742

Key Concepts 742

Internet Resources 743

References 743

APPENDIXES 747

A. Clinical Competencies for

IBCLC Practice 749

B. Code of Ethics 754

C. Summary of Eligibility Pathway Requirements to Become Certified

by IBLCE 756

D. Prototype Lactation Consultant

Job Description 758

E. Tables of Equivalencies and Methods

of Conversion 761

F. Infant Weight Conversion Table 762 G. Breastfeeding Weight Loss Table 763

H. Patient History 764

Glossary 773

Index 785

I have worked in the field of lactation since the early 1960s, first as a La Leche Leader and later as a lactation consultant when it became a professional practice discipline in 1985. As I look back over those years I am struck both by how different things are now and by how much things have stayed the same. Although the breastfeeding initiation rate in the United States has risen to almost 70 percent––a vast improvement from 20 percent in the 1960s!––it still takes time and patience to help a new breast-feeding mother get her baby onto the breast.

New knowledge has changed the field. Re-search studies now verify that breastfed children are more intelligent and that not breastfeeding costs the U.S. health care system billions of dollars annually. Because of the new awareness of the importance of breastfeeding, the number and influence of lacta-tion consultants has expanded. The Internalacta-tional Board of Lactation Consultants has certified more than 10,000 health care workers in 36 countries. Most hospitals, large and small, offer lactation ser-vices of some type and employ lactation consul-tants. Lest anyone question the powerful, positive influence of interventions by health care workers on breastfeeding, they only need to review the table of intervention studies in Chapter 2. At the same time, lest we follow that conflicted path that led to the medicalization of childbirth, we must listen to voices that warn of the danger of lactation consul-tants medicalizing infant feeding.

Other changes affect lactation practice. The in-surance industry now drives the health care system, reversing the reward system in favor of short hospi-tal stays, which are now two days or less in the U.S. for vaginal births. While these short stays mean that breastfeeding mothers and babies return home less likely to be exposed to hospital infections and to supplementary feedings, this brief time allows al-most no opportunity to ensure that the baby is breastfeeding effectively. Mothers still needing care themselves return home to assume full-time child-care before they feel physically able to do so. Fol-low-up care of a new family at home should be universal, yet many mothers of preterm and “near-term” breastfed infants who are developmentally

immature leave the hospital without any plan for as-sistance.

This text brings together in a single volume the latest clinical techniques and research findings that direct evidence-based clinical practice. I have been fortunate in being able to enlist a dozen breastfeed-ing experts recognized around the world to help with the writing of this extensive volume. Dr. Kathleen Auerbach, the much-missed former co-author of this book, remains as co-author of two chapters.

Over 1,000 research studies support the clinical recommendations in this book. The Internet and MEDLINE made the literature searches so much easier for this edition––a sea of change from writing the first two editions. The Internet also made possi-ble quick correspondence with colleagues and chapter authors as this book progressed. Addresses of helpful resources on the Internet have been added to each chapter.

Like the earlier editions, the third edition of this text has a clear clinical focus. A new chapter on in-fant assessment reflects current expectations that the health care worker working with the breastfeed-ing dyad can perform a total assessment of the baby. Nearly every chapter contains a clinical im-plications section. Important concepts discussed in chapters are summarized at the end of each chapter––a new feature that will make studying eas-ier. Throughout the book are new references deemed by the authors to be the most important from the vastly expanded research and clinical lit-erature. Some older references that introduced new ideas that are now accepted common knowledge have been regretfully removed to make room for new research. The glossary of key terms relating to lactation has been expanded in this edition.

Section 1contrasts the past and present. Chap-ter 1 presents the history of breastfeeding by plac-ing lactation and breastfeedplac-ing in its historical context. Chapter 2 fast-forwards to the work of the present-day health care worker who specializes in lactation and breastfeeding, and it addresses the re-ality of work-related issues of lactation consulting.

Section 2 focuses on basic anatomic and bio-logic imperatives of lactation. Clinical application of

P R E F A C E

xxii Breastfeeding and Human Lactation

techniques must be based on a clear understanding of the relationships between form, function, and bio-logical constructs. Thus this section, too, provides the background upon which to understand other as-pects of lactation and breastfeeding behavior.

Section 3is the clinical “heart” of the book that describes the basics of whatto do, whento do it, and how to do it when one assists the lactating mother. Section 3 thus concerns itself with the perinatal pe-riod in the birth setting and concerns during the postpartum period following the family’s return home—notably breast problems, neonatal jaundice, and infant weight gain. This section also addresses special needs of preterm babies and their mothers, and it critically evaluates breastfeeding devices and recommends how and when they are most appro-priately used. It concludes with a review of the de-velopment and current activities of human milk banking.

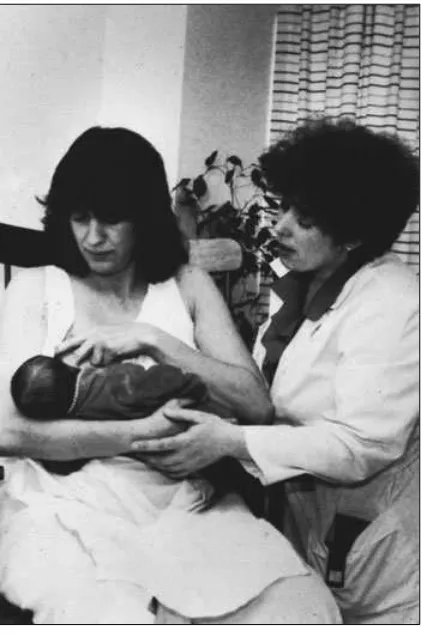

The first part of Section 4 focuses on the mother: maternal nutrition, the mother’s health, and returning to work. The topics then turn to the infant and child’s health and special health needs. The techniques of infant assessment are explained

and demonstrated with photographs in a new chap-ter. The section ends with a discussion of maternal sexuality and fertility.

Section 5begins with a careful look at research–– how it is conducted, why ongoing research is needed, and how research findings can be applied in clinical settings. The principles of education, the cor-nerstone of clinical practice, are explored next. The book concludes with the socio-cultural context of the breastfeeding family and explores the different ways in which the breastfeeding family functions within that context.

I gratefully acknowledge the contributions to this book made by the following individuals:

Judy Angeron BA, RN, IBCLC, Coordinator, Lac-tation Services, Via Christi Regional Medical Cen-ter, Wichita, Kansas

Kathleen G. Auerbach PhD, IBCLC, Ferndale, Washington

Suzanne Bentley MSN, CNM, IBCLC, Clinical Nurse Specialist, University of Kansas, Clinical In-structor, University of Kansas, School of Nursing, Kansas City, Kansas

Belinda Childs MN, ARNP, CDE, Clinic/Re-search Coordinator, Mid-America Diabetes Associ-ates, Wichita, Kansas

Mary Margaret Coates MS, IBCLC, TechEdit, Wheat Ridge, Colorado

Amy Ellington RN, BSN, Lactation Consultant, Via Christi Regional Medical Center, Wichita, Kansas

Barbara Gabbert-Bacon, La Leche League, Wi-chita, Kansas

Lenore Goldfarb, B.Comm, B.Sc, IBCLC, Herzl Family Practice Centre, Sir Mortimer B. Davis-Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Robert T. Hall MD, Professor, Children’s Mercy Hospital and Clinics, Kansas City, Missouri Eileen Hawkins MSN, ARNP, Wichita State Uni-versity, School of Nursing, Wichita, Kansas

Kerstin Hedberg-Nyqvist PhD, RN, IBCLC, Assis-tant Professor in Pediatric Nursing, Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, Uppsala Univer-sity,Uppsala, Sweden

Heather Hull MSN, PNP, Instructor, Wichita State University, Wichita, Kansas

Voni Miller RN, IBCLC, Lactation Consultant, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, Arizona Gerald Nelson MD, The University of Kansas School of Medicine, Wichita, Kansas

Amal Omer-Salim, MSc, Nutritionist, International Maternal and Child Health, Department of

Women’s and Children’s Health, Uppsala Univer-sity, Uppsala, Sweden

Virginia Phillips, IBCLC, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

Christina M Smillie MD, FAAP, IBCLC, Breast-feeding Resources, Stratford, Connecticut

I am especially grateful to La Leche League Inter-national for providing the foundation for my breast-feeding education and to those institutions which encouraged and supported me in writing the book: the School of Nursing, Wichita State University, and Via Christi Regional Medical Center, both of Wichita, Kansas.

Finally, thanks to my family: Hugh, Michael, Neil and Shirley, Brian, Quinn and Rika Riordan, Teresa Riordan and Richard Chenoweth, Renee and Don Olmstead and our 11 (breastfed) grand-children.

A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S

xxiv

Kathleen G. Auerbach,PhD, IBCLC Ferndale, Washington

Lois D. W. Arnold,PhD (C.), MPH, IBCLC National Commission on Donor Milk Banking East Sandwich, Massachusetts

Debi Leslie Bocar,PhD, RN, IBCLC Perinatal Educator, Mercy Health Center Director, Lactation Consultant Services Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Yvonne Bronner,ScD, RD, LD

Professor and Director, Public Health Program Morgan State University

Baltimore, Maryland

Mary Margaret Coates,MS, IBCLC TechEdit

Wheat Ridge, Colorado

Lawrence M. Gartner,MD Professor Emeritus

Departments of Pediatrics and Obstetrics/ Gynecology

The University of Chicago Chicago, Illinois

Kathy Gill-Hopple,MSN, RN Instructor

Wichita State University, School of Nursing Wichita, Kansas

Thomas W. Hale,PhD, RPH Professor of Pediatrics

Texas Tech University, School of Medicine Amarillo, Texas

Marguerite Herschel,MD Associate Professor of Pediatrics

Medical Director, General Care Nursery The University of Chicago

Chicago, Illinois

Roberta J. Hewat,PhD, RN, IBCLC Associate Professor

University of British Columbia, School of Nursing,

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Kay Hoover, MEd, IBCLC

Philadelphia Department of Public Health Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Nancy Hurst,RN, MSN, IBCLC

Director, Lactation Program and Mother’s Own Milk Bank

Texas Children’s Hospital Assistant Professor of Pediatrics Baylor College of Medicine Houston, Texas

Kathy I. Kennedy,MA, Dr.PH

Director, Regional Institute for Health and Envi-ronmental Leadership,

University of Denver Associate Clinical Professor of Preventive Medicine,

University of Colorado Health Sciences Denver, Colorado

Mary Koehn,PhD, RN, MSN Assistant Professor

Wichita State University, School of Nursing Wichita, Kansas

Paula Meier,DNSc, RN, FAAN

NICU Lactation Program Director, Department of Maternal-Child Nursing,

Associate Director for Clinical Research, Section of Neonatology,

Rush-Presbyterian-St Luke’s Medical Center Chicago, Illinois

Sallie Page-Goertz,MN, CPNP, IBCLC Assistant Clinical Professor,

KU Children’s Center/Kansas University School of Medicine

Overland Park, Kansas

Nancy Powers,MD

Medical Director, Lactation Services Pediatrix Medical Group

Chapter Authors xxv

Wailaiporn Rojjanasrirat,PhD, MSN Research Assistant Professor

University of Kansas, School of Nursing Kansas City, Kansas

Linda J. Smith, BSE, FACCE, IBCLC Bright Future Lactation Resource Centre Ltd. Dayton, Ohio

Marsha Walker,RN, IBCLC Lactation Associates

Executive Director, National Alliance for Breast-feeding Advocacy

Research, Education, and Legal Branch Weston, Massachusetts

Karen Wambach,PhD, RN, IBCLC Assistant Professor

Just as the breastfeeding course flows and ebbs in

a woman’s life, so breastfeeding has experienced

flows and ebbs through the centuries. It takes a

vil-lage to return to breastfeeding, and community-based

programs that promote breastfeeding are successfully

and steadily increasing the rate of breastfeeding

around the world.

As more mothers choose to breastfeed, the need for

specialized help increases also. The visibility and

ac-ceptance of lactation consulting as an allied health

profession offers opportunities for practice in

hospi-tals, the community, and in private practice.

Ran-domized clinical trials consistently demonstrate that

lactation consultant services lengthen a mother’s

breastfeeding course and save money through

health-ier mothers and babies.

Historical and Work Perspectives

1

S E C T I O N

3

1

C

H

A

P

T

E

R

Throughout the world today, an infant is apt to re-ceive less breastmilk than at any time in the past. Until the 1940s, the prevalence of breastfeeding was high in nearly all societies. Although the feed-ing of manufactured milks and baby milks had begun before the turn of the century in parts of Eu-rope and North America, the practice spread slowly during the next decades. It was still generally lim-ited to segments of population elites, and it in-volved only a small percentage of the world’s people. During the post–World War II era, how-ever, the way in which most mothers in industrial-ized regions fed their infants began to change, and the export of these new practices to developing na-tions was underway.

Evidence About Breastfeeding

Practices

How do we know what we “know” about the preva-lence of breastfeeding? (The wordprevalenceis used here to mean the combined effect of breastfeeding initiation rates and breastfeeding continuance rates.) Before attempting to trace trends in infant feeding practices, let us consider the nature of the evidence.

Tides in Breastfeeding Practice

Mary Margaret Coates and Jan Riordan

Large-Scale Surveys

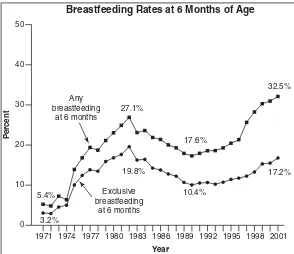

National surveys that produce the kind of represen-tative data that allow statistical evaluation have been available only since 1955. These surveys consist pri-marily of national fertility or natality surveys and of marketing surveys conducted by manufacturers of artificial baby milk. For most, exclusive breastfeed-ing is not a separate statistic. However, the percent-age of exclusive breastmilk feedings at hospital discharge can be found in state birth certificate data-bases (Feldman-Winter et al., 2002). A brief descrip-tion of nadescrip-tional surveys conducted in the United States follows (Grummer-Strawn & Li, 2000):

● National Health Interview Survey:A personal in-terview is conducted in 43,000 households. Questions about incidence and duration of breastfeeding are asked.

4 Historical and Work Perspectives

● Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance System (PedNSS): Statistics of breastfeeding incidence and duration in low-income populations are collected in pub-lic health clinics and reported annually. National, state, county, and clinic data are analyzed.

● WIC Participant Characteristics Study: Data on breastfeeding are collected each even-num-bered year by the Department of Agriculture.

● Ross Laboratories Mothers Survey: Questionnaires are mailed to new mothers whose names are obtained from a national sample of hospitals and physicians. For marketing purposes, data on type of milk fed is collected for up to 12 months for a given cohort. Data are published on an ad hoc basis. The survey currently func-tions as a baseline and monitoring data source for breastfeeding goals in Healthy People 2010.

● Mead-Johnson Longitudinal Study of Infant Feeding Practices:For marketing purposes, a panel of in-fants is followed for 12 months. Data is col-lected on incidence of, duration of, and changes in breastfeeding frequencies.

Outside the United States, representative data for countries in Latin America, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East are derived from three sources. World Fertility Surveys are sponsored by the Office of Population within the United States Agency for In-ternational Development (USAID), the United Na-tions Fund for Population Activities, and the United Kingdom Office of Development Assistance (Light-bourne, Singh, & Green, 1982). The World Health Organization began ongoing surveys on infant feeding in the mid-1970s. Its Global Data Bank on Breast-Feeding pools information garnered from well-designed nutrition and breastfeeding surveys around the world; on the basis of these data, breast-feeding practices are periodically summarized. The most recent summary appeared in 2000 (WHO, 2000). Finally, demographic and health surveys were initiated in 1984; these ongoing surveys are sponsored jointly by USAID and governments of host countries in which the surveys are made.

Other Evidence

Until the last several decades, breastfeeding was the unremarkable norm. Thus what we “know” about

breastfeeding from much earlier times often must be inferred from evidence of other methods of feeding infants. Most historical material available in English-language literature derives from a rather limited ge-ographic area: Western Europe, Asia Minor, the Middle East, and North Africa. Written materials, which include verses, legal statutes, religious tracts, personal correspondence, inscriptions, and medical literature, extend back to before 2000BC.

Some of the earliest existing medical literature deals at least in passing with infant feeding. An Egyptian medical encyclopedia, the Papyrus Ebers (c. 1500 BC), contains recommendations for

increas-ing a mother’s milk supply (Fildes, 1986). The first writings to discuss infant feeding in detail are those of the physician Soranus, who practiced in Rome aroundAD100; his views were widely repeated by

other writers until the mid-1700s. It is not immedi-ately apparent to what degree these early exhorta-tions either reflected or influenced actual practices. Many writings before AD 1800 deal primarily with

wet nurses or how to hand-feed infants.

Archeological evidence provides some informa-tion about infant feeding prior to 2000BC. Some of

the earliest artifacts are Middle Eastern pottery fig-urines that depict lactating goddesses, such as Ishtar of Babylon and Isis of Egypt. The abundance of this evidence suggests that lactation was held in high re-gard (Fildes, 1986). Such artifacts first appear in sites about 3000 BC, when pottery making first became

widespread in that region. Information about infant feeding may also be derived from paintings, inscrip-tions, and infant feeding implements.

Modern ethnography has a place of special im-portance. By documenting the infant feeding prac-tices of present-day nontechnological hunter-gath-erer, herding, and farming societies, ethnographers expand our knowledge of the range of normal breast-feeding practices. At the same time, they provide a richer appreciation of cultural practices that enhance the prevalence of breastfeeding. Such studies are also our best window into breastfeeding practices that may be the biological norm forHomo sapiens sapiens.

Tides in Breastfeeding Practice 5

FIGURE 1–1. The antiquity of lactation. The bottom line shows the approximate times of first appearance of lactating precursors of modern humans and of reg-ular use of nonhuman animal milk by humans.

The Biological Norm in Infant Feeding

Early Human Evolution

The class Mammalia is characterized principally by the presence of breasts (mammae), which secrete and release a fluid that for a time is the sole nour-ishment of the young. This manner of sustaining newborns is extremely ancient; it dates back to the late Mesozoic era, some 100 million years ago. (See Figure 1–1.) Hominid precursors first appeared about 4 million years ago; the genus Homohas ex-isted for about 2 million years. The currently dom-inant human species, Homo sapiens sapiens, has existed for perhaps 40,000 years. Information about breastfeeding practices among our earliest ances-tors is uncertain, although other information about Paleolithic societies that existed 10,000 or more years ago sheds light on this subject.

Early Breastfeeding Practices

Diets reconstructed by archeological methods re-veal that the Late Paleolithic era, roughly 40,000 to

10,000 years ago, was populated by pre-agricultural peoples who ate a wide variety of fruits, nuts, veg-etables, meat (commonly small game), fish, and shellfish. This diet closely resembles that of twenti-eth-century hunter-gatherer societies. Therefore, the infant-feeding practices of societies today may reflect breastfeeding practices of much earlier (pre-historic) times. Consider the breastfeeding practices of the ¡Kung of the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa (Konner & Worthman, 1980) as well as hunter-gatherer societies of Papua New Guinea and elsewhere (Short, 1984). Among these people, breastfeeding of young infants is frequent (averag-ing four feeds per hour) and short (about 2 minutes per feed). It is equally distributed over a 24-hour period and continues, tapering off gradually, for two to six years. These breastfeeding patterns are considered a direct inheritance of practices that pre-vailed at the end of a long, and dietetically stable, evolutionary period that ended about 10,000 BC.

This assumption is supported by observations of the human’s closest primate relative, the chimpanzee, which secretes a milk quite similar to that of hu-mans, suckles several times per hour, and sleeps with and nurses its young at night (Short, 1984).

The Replacement of Maternal

Breastfeeding

Wet-Nursing

Wet-nursing may not have been the earliest alterna-tive to maternal breastfeeding, but it was the only one likely to enable the infant to survive. Wet-nurs-ing is common, although not universal, in tradi-tional societies of today and (by inference) among ancient human societies. An already-lactating woman may have been the most obvious choice for a wet nurse, but women who stimulate lactation without a recent pregnancy have been described in many traditional societies (Slome, 1976; Wiesch-hoff, 1940).

Wet-nursing for hire is mentioned in some of the oldest surviving texts, which implies that the practice was well established even in ancient times. The Babylonian Code of Hammurabi (c. 1700 BC)

6 Historical and Work Perspectives

for the foundling Moses; the fact that the “wet nurse” was Moses’s own mother is incidental. The epic poems of Homer, written down around 900

BC, contain references to wet nurses. A treatise on

pediatric care in India, written during the second centuryAD, contains instructions on how to qualify

a wet nurse when the mother could not provide milk. The Koran, written about AD 500, also

per-mits parents to “give your children out to nurse.” Although the history of wet-nursing has contin-ued virtually unbroken from the earliest times to the present, the popularity of the practice among the elite classes who used it most has waxed and waned. In England during the 1600s and 1700s and elsewhere in Europe, the middle classes began to employ wet nurses. The use of less attentive nurses and the sending of infants greater distances from home diminished maternal supervision of either nurse or infant. Often infants were not seen by their parents from the time they were given to the nurse until they were returned home after weaning (pro-viding they lived). However, by the latter part of the 1700s wet nursing was on the decline in North America and England (except in foundling hospi-tals), owing to increased public concern regarding the moral character of wet nurses and the quality of the care they provided. In France, government offi-cials and physicians led a campaign against wet nursing. Some women recalling this period of his-tory proudly reported that they nursed their babies themselves (Yalom, 1997). Throughout this long pe-riod, wet nurses were used sometimes because of maternal debility but more often because of the so-cial expectations of the class of women who could afford to hire a wet nurse in order to free them for obligations incumbent upon highborn ladies. Thus the use of wet nurses by social elites foreshadows the demographic pattern later seen in the use of manufactured baby milks.

Hand-Fed Foods

The Agricultural Revolution.

The idea that an-imal milks are suitable foods for human infants is reflected in such myths as that of Romulus and Remus, the mythical founders of Rome, who are usually depicted as being suckled by a wolf. Sur-prisingly, the currently most popular hand-fed in-fant foods––animal milks and cereals––did notbecome part of the human diet until well along in human history. Cereal grains first appeared only about 10,000 years ago, and animal milks some-what later (McCracken, 1971). The widespread adoption of these foods was made possible by the development of agriculture and (later) animal hus-bandry. Perhaps because of the availability of new weaning foods, periods of lactation that normally lasted three to six years were shortened to about two years in farming and herding societies (Schae-fer, 1986).

Gruels.

In much of the world, the soft foods added most commonly to the infant diet have been gruels containing a liquid, a cereal, and other sub-stances that added variety or nutritional value. The cereal might be rice, wheat, or corn. It might be boiled and mashed; ground and boiled; or, as in the case of bread crumbs, ground, baked, crushed, and heated. The liquid might be animal milk, meat broth, or water. Eggs or butter might also be added. If grains are not commonly eaten, similar soft foods for infants are based on starchy plants such as taro, cassava, or plantain.Animal Milks.

Animal milks are a relatively re-cent addition to the human diet; this is implied ge-netically, because children beyond weaning age commonly do not produce lactase, an enzyme needed to digest the milk sugar lactose. In cultures that traditionally do not use animal milks, such as those in Mexico or Bangladesh or Thailand, some children may be lactose-intolerant before 1 year of age; in those cultures that use animal milks abun-dantly, the onset of lactose intolerance occurs con-siderably later––after age 10––in Finland (Simoons, 1980). Adult lactose tolerance is common only in cultures in which animal milks have traditionally been an important part of the diet, such as those of northern Europe and western Asia (McCracken, 1971).Tides in Breastfeeding Practice 7

infant feeding, a small spouted bowl found in an in-fant’s grave in France, is dated c. 2000–1500 bc (La-caille, 1950). Small spouted or football-shaped bowls have been found in infant burial sites in Ger-many (c. 900 bc) and in the Sudan in North Africa (c. 400 bc) (Lacaille, 1950). These utensils suggest that hand-feeding of infants has been attempted for more than three millennia. (See Figure 1–2.)

Timing of the Introduction of

Hand-Feeding

What archeological evidence cannot tell us is why or how much these infants were hand-fed. Neonates may temporarily be offered certain foods as prelacteal feeds; young infants may be offered oc-casional tastes of other foods, and they will be of-fered increasing amounts of soft foods as they make the transition to the adult diet (mixed feeds). Fi-nally, infants may be reared from birth on other foods (artificial feeding).

Prelacteal Feeds.

Many of the world’s infants, even those who later will be fully breastfed, receive other foods as newborns. Of 120 traditional soci-eties (and, by inference, in many ancient preliterate societies) whose neonatal feeding practices have been described, 50 delay the initial breastfeeding more than two days, and some 50 more delay it one to two days. The stated reason is to avoid the feed-ing of colostrum, which is described as befeed-ing dirty, contaminated, bad, bitter, constipating, insufficient, or stale (Morse, Jehle, & Gamble, 1990).Early medical writers in the eastern Mediter-ranean region (Greece, Rome, Asia Minor, and Arabia) and later in Europe––from Soranus through those of the 1600s––also discouraged the use of colostrum for feeding. These writers recommended avoiding breastfeeding for periods as short as one day (Avicenna, c. AD1000) to as long as three weeks

(Soranus, c. AD 100). Commonly, to promote the

passage of meconium, the newborn was first given a “cleansing” food such as honey, sweet oils (such as almond), or sweetened water or wine.

In Europe, the fear of feeding an infant colostrum may have contributed to the undermin-ing of maternal breastfeedundermin-ing, at least among the upper classes, and spread wet-nursing (Deruisseau, 1940). A similar charge has been leveled at the prelacteal bottle feeds commonly given in Western (or Western-style) hospital nurseries; many studies show that early bottle-feeds undermine breastfeed-ing and increase the mother’s use of manufactured baby milk. One can only wonder if Western hospi-tal practices, which include delayed first breastfeed-ing and prelacteal feeds of water or artificial baby milk, are technological vestiges of this widespread traditional “taboo.”

Not all published work supports the idea that prelacteal feeds and a delay in initiating breastfeed-ing reduce the likelihood of continued lactation (see Chapter 24). Some authors believe that ensuing breastfeeding is associated with the maternal per-ception that prelacteal feeds are appropriate. They hold that a particular set of culturally approved maternal behaviors follows the commencement of breastfeeding: nearly constant contact with or proximity to the infant; breastfeeding ad lib day and night; and no further use of feeding bottles (Nga & Weissner, 1986; Woolridge, Greasley, & Silpisornkosol, 1985).

Mixed Feeds.

On the basis of current practices of many traditional societies, early mixed feedings may be the most common infant-feeding regimen (Dimond & Ashworth, 1987; Kusin, Kardjati, & van Steenbergen 1985; Latham et al., 1986).Mixed feeding is widely practiced, even during the time when breastmilk forms the foundation of the infant diet. In many regions, such as Africa and Latin America, breastfeeding continues into the sec-ond or third year of life. In non-Western cultures, FIGURE 1–2. An English Staffordshire Spode nursing

8 Historical and Work Perspectives

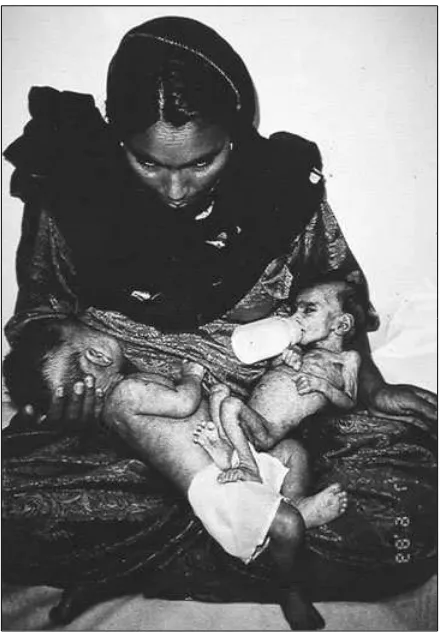

FIGURE 1–3. UNICEF photograph of thriving breast-fed twin and his dying bottle-breast-fed sister. (Courtesy of Children’s Hospital, Islamabad, Pakistan.)

hand-fed foods include tea infusions, mashed fruits, and a variety of starchy gruels or pastes. Where the use of a particular food dominates a culture (e.g., rice in many parts of Asia), that food is usually the principal family food fed to an infant ( Jelliffe, 1962). In some (mostly non-Western) cultures, such foods are offered to weaning infants in such a way that they supplement, rather than replace, breastmilk (Greiner, 1996; Whitehead, 1985) and thus do not appreciably hasten complete cessation of breast-feeding. The use of feeding bottles, however, can shorten the weaning interval, the period between full sustenance by breastmilk and full sustenance by family foods (Winikoff & Laukaran, 1989).

Hand-Feeding from Birth.

In a few regions of northern Europe (e.g., Switzerland, Finland, and Iceland) a cool, dry climate and a tradition of dairy farming permitted the survival of at least some in-fants who were fed cow milk nearly from birth. From at least the 1400s in Switzerland and Finland, breastfeeding was actively discouraged (Fildes, 1986). However, even in climatically optimal areas, hand-feeding was hazardous. In Iceland infants were hand-fed during the 1600s and 1700 despite disastrous results; married women bore as many as 30 infants because so few survived (Hastrup, 1992). In France, some foundlings and infants with syphilis were fed directly from goats; this practice was first described in writings in the 1500s, and it persisted until the early 1800s (Wickes, 1953a). Of necessity, foundling hospitals of the 1700s and 1800s in Europe and the United States hand-fed in-fants but with appalling mortality rates: up to 100 percent died. (See Figure 1–3.) However, by the mid-1900s in industrialized countries, hand-feeding from birth had become the norm and hand-fed in-fants survived and grew. Why did that happen?Technological Innovations in Infant

Feeding

The Social Context

During the late 1800s and the early 1900s, high in-fant mortality, even among inin-fants cared for at home, was a major public concern. Physicians and parents recognized that poorly nourished children were more susceptible to illness. Between 1910 and

Tides in Breastfeeding Practice 9

As women’s aspirations for community service and commercial involvement were rising, Victorian beliefs about modesty discouraged breastfeeding in public. Advertising, which promoted bodily cleanli-ness, may have led to associating breastmilk with body fluids that were unclean or noxious, a notion that persists to this day, at least in North America (Morse, 1989). Advances in the prevention of dis-ease, largely through public health measures re-lated to sanitation, extended an expanding faith in “modern science” in general to “modern medicine” in particular. Women’s magazines developed a wide audience of readers interested in female accom-plishments outside the home, in modern attitudes, and in technological innovations; these same maga-zines reinforced concerns about infant health. An 1880 issue of the Ladies’ Home Journalcontained this statement(Apple, 1986):

If fed from your breast, be sure that the quantity and

quality supply his demands. If you are weak or worn

out, your milk cannot contain the nourishment a

babe needs.

The Technological Context

Between about 1860 and 1910, scientific advances and technological innovations created many new options in infant feeding that appeared to enhance infant survival. The upright feeding bottle and rub-ber nipple, each of which could be cleaned thor-oughly, made artificial feeding easier and safer. New foods to be used with this equipment ap-peared. Large-scale dairy farming produced abun-dant supplies of cow milk, which was marketed first as canned evaporated milk and later in condensed (i.e., highly sweetened to retard spoilage) or dried forms.

This technological ferment, fueled both by the need for improved infant health care and by a pop-ular belief in the ability of science and technology to provide answers, attracted analytical chemists. Around 1850 chemists had begun to turn their at-tention to food products. Early investigations (now viewed as rudimentary) into the composition of human and cow milk convinced them that “the combined efforts of the cow and the ingenuity of man” could construct a food the equal of human

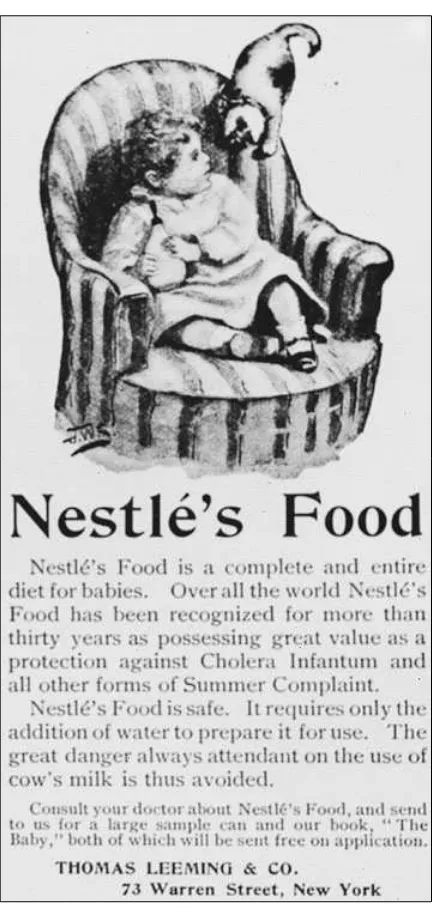

milk (Gerrard, 1974). Patented foods, such as Liebig’s Food and Nestle’s Milk Food, were first marketed in Europe and the United States in the 1860s. The Nestle’s product was a mixture of flour, cow milk, and sugar that was to be dissolved in milk or water before feeding. Milk modifiers, such as Mellin’s Food, and milk foods, such as Horlick’s Malted Milk, were popular in the United States by the 1880s.

Extravagant claims for these foods (Liebig’s Food was called “the most perfect substitute for mother’s milk”) were combined with artful adver-tising that played on fears for the health of the in-fant and faith in modern science (Apple, 1986). (See Figure 1–4.) A hundred years later we see these ad-vertising themes played again and again.

In the 1890s, physician Thomas Rotch devel-oped a complex system of modifying cow milk so that it more closely resembled human milk. Rotch observed that the composition of human milk varies, as do digestive capacities in infants. He devised mathematical formulas to denote the proportions of fat, sugar, and protein in cow milk that some infants required at a particular age (Rotch, 1907). The result was an exceedingly com-plex system of feeding that required constant in-tervention by the physician, who often changed the “formula” weekly. Supervising infant feeding then became a principal focus of the newly emerg-ing specialty of pediatrics.

Commercial advertising promoted the use of manufactured infant milks to both mothers and physicians. The basic themes––a mother’s con-cern for her infant’s health, the perfection of the manufactured product, and the difficulty of breastfeeding––have persisted over the years (Apple, 1986).