Brent R. Weisman

Florida Archaeology Confronts

the Recent Past:

Four Case Studies from Tampa

ABSTRACT

Human activity of the recent past has resulted in an interpretable archaeological record that can be investigated systematically by archaeologists and serve the interests of people in the pres-ent seeking to define and connect with a history relevant to them. In Florida archaeology, academic and cultural resource management environments have not favored the development of archaeological research designs that bring problem-driven stratigraphic approaches to bear on specific deposits dating from the 1880s to the present, therefore, opportunities for a scientifically based public archaeology are being lost. In the young city of Tampa, understanding the depositional processes that contributed to the archaeological record can produce insights into the social, economic, and political forces that shaped the growth of the city into its present form. In particular, deposits resulting from demolition and fill need to be considered as legitimate subjects of archaeological research and understood as the loci for intersecting levels of political relations. Archaeology of the recent past can be immediately attractive to community interests seeking to develop or rein-force heritage identities, and the very act of archaeology can serve these purposes regardless of actual results. In a more traditional role, archaeology can partner with more visible historic preservation efforts to bring a community-based his-tory to local architectural landmarks.

Why Tampa’s Recent Past Has Received Little Attention

Advances in the archaeology of Florida’s recent past have been hindered by a meaning, well-trained, and dedicated archaeological community determined to demonstrate that Florida has an ancient past worth knowing about and preserv-ing. No doubt, this is a worthwhile cause given Florida’s public image as a transient “dream state” (Mormino 2005), but one ultimately coun-terproductive to appreciating archaeology’s value in understanding the realities of Florida’s pres-ent. If the recent past is further defined to mean the late 19th to mid-20th centuries as a subset of the much broader span of time considered by historical archaeology, archaeological interest

would be found to be even less developed, with very few sustained and systematic investiga-tions of contexts dating to within the past 130 years. Although Florida’s historic preservation contexts that cover the recent past (Florida Division of Historical Resources 1996) do not rule out archaeological investigation, neither are they easily adapted to the kinds of settings in which compliance archaeologists typically find themselves. From the turn-of-the-century context (1898–1916) forward through the modern period beginning in 1950, archaeological research is not explicitly mentioned as a means of gaining additional knowledge. This same situation also pertains to Hillsborough County’s own historic resources survey (Hillsborough County 1998). Material remains of this period, however, are not especially scarce. Many have at least adequate historical documentation to allow for the devel-opment of a contextual research design and are found in soil deposits with sufficient integrity to produce a meaningful archaeological record.

Yet, perhaps overwhelmed by the need to mitigate damage to Florida’s imperiled and ever-vanishing prehistoric record, archaeologists rarely consider the investigation of the recent past with the legitimacy, passion, and seriousness of purpose that they devote to the more tradi-tional archaeological pursuit of Florida’s Native American prehistory. In the absence of a positive value structure, and lacking insightful and acces-sible theoretical perspectives that make sense in the contexts of Florida history, archaeologists (understandably) rarely devote much effort to the very recent past, and in so doing, I argue, are missing significant opportunities to truly engage with the public and to contribute to scholarly debates about the nature of modern life. Archae-ologists need not reach far for examples and model projects upon which to base future work. Urban archaeology in the American South has contributed fundamentally to the emergence of urban archaeology as a legitimate pursuit (Dick-ens and Bowen 1980; Dick(Dick-ens 1982; Staski 1987; Garrow 1995; Young 2000) and has demonstrated the value of applying archaeological perspec-tives to time periods usually consigned strictly

Historical Archaeology, 2011, 45(2):16–41. Permission to reprint required.

to the historian’s domain. Further, the broader literature on contemporary urban archaeology is replete with examples of archaeology’s relevance for understanding the complexities of modern life (Praetzellis 1994; Cantwell and Wall 2001; Mayne and Murray 2001).

The materiality of modern Florida is not without its advocates. Historical preservationists flock to support renovation and restoration of architectural gems such as Ybor City’s impres-sive turn-of-the-century cigar factories and ethnic social clubs built and owned by the cigar makers (Long 2006). Small town Main Streets and their courthouses and train depots often find grassroots support for public-private partnerships that net state or federal dollars for sprucing up civic cen-terpieces. The estates of the historically rich and famous find enthusiastic community support for their refurbishment. Yet, with few exceptions (all of them unpublished), sites relating to “history writ small,” the everyday history of daily life, and the dark side of history, all remain beyond preservation’s veil. Work camps and industrial sites are but little known and cared about (Smith 1995; Baram et al. 2001; Mikell and Butler 2003; Kendrick and Walsh 2007:195–213). World War II properties (including German POW camps) and Cold War facilities are just now entering public awareness, but remain largely archaeo-logically uninvestigated. Lighthouses have fared better due to their symbolic value for community identity, but concerns with physical repairs to the structures and basic preservation take pre-cedence over the preservation and investigation of the archaeological record associated with the lighthouse keepers and their families (Smith and Rolland 1996; Weisman 1998). State compliance requirements have never mandated intensive data-recovery excavations of a site dating exclusively to the 20th century. The preservation climate can be seen as heavily favoring the built environment and having little appreciation for the value of archaeological research and the public benefits of archaeology.

a post–Civil War, post-Reconstruction Florida struggling for fiscal and governmental stability; grasping for any and all opportunities to improve basic infrastructure, such as roads and schools; and attempting to restore a comfortable, that is, racially divided social order, while recognizing the need to integrate ethnically diverse immigrant populations. Further, the state was facing a new national economy in which cotton was no longer king, industrial production ruled, and Florida had relatively little to offer. Responses to the myriad challenges of population growth and chronic eco-nomic underdevelopment have been ever present since the last decades of the 19th century and continue to play out in the present day. The demography, politics, economy, and sociology of this recent past together form the foundations of modern Florida.

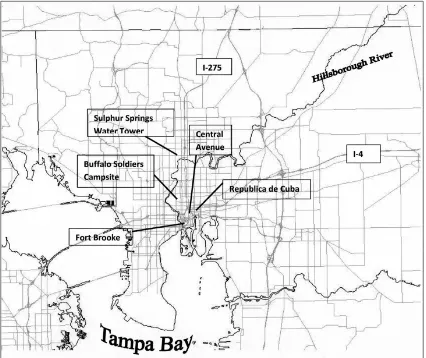

This article will describe four recent projects conducted in Tampa, Florida (Figure 1). These modest case studies, when considered together, illustrate ways in which archaeology can be conducted as a scientific pursuit in the public interest, theoretically informed and respecting the fundamentals of sound archaeological practice, while also acknowledging archaeology’s role in creating a tangible link to the perceived past. In doing the archaeology of the recent past, it becomes immediately clear that it can connect people to their own histories in very direct ways, by bringing places and things tenuously existing only at the edge of memory back into view, into touch. Thus, this archaeology can be at once both public in its message and appeal, and very pri-vate as it evokes, for the individual, experiences with the remembered past. Further, it can be systematically understandable by applying strati-graphic principles and seeking middle-range cor-relations between multiscaled patterns of human behavior, normalizing it within the discipline of archaeology and bringing uniquely archaeologi-cal perspectives to bear on contemporary human issues more commonly considered to be within the realms of history and sociology.

scope, provides a methodological benchmark for future work and contributes substantively toward building an urban-deposit model for the city of Tampa. Although care must be taken not to over generalize the value of the Tampa cases in establishing a new research paradigm for Florida archaeology, it is hoped that archaeologists will find some inspiration in this approach and begin to explore this new domain of Florida archaeology.

Tampa as an Archaeological Site

The present city of Tampa has a population of nearly 400,000 and anchors, along with St. Petersburg, a metropolitan area containing some 3 million people. Billed by its own public

relations office as the “City of Neighborhoods,” Tampa includes a number of formerly separate communities that still maintain their ethnic or historical identities. The visitor today can still experience the distinct look and feel of neighbor-hoods such as Seminole Heights, Tampa Heights, West Tampa, and Hyde Park, all National Regis-ter districts; the retroatmospheric community of Sulphur Springs; and the distinctly Latin-influence National Historic Landmark District of Ybor City. The core area of downtown Tampa, the Central Business District, rises above the now-buried remains of Fort Brooke, which intruded upon an earlier, extensive, aboriginal shell-midden and burial-mound complex of the Manasota culture (Hardin and Austin 1987). An 1845 pencil sketch of Fort Brooke shows a large conical mound

within the fort compound, clearly incorporated as a landscape feature (Brown 1999:68). Built in 1824 as both a foothold on the Florida frontier and a checkpoint for the newly created 4-million-acre Seminole Indian reservation (Mahon 1967:50) in the central portion of the peninsula, Fort Brooke consisted of an open plan of wooden barracks, storehouses, blockhouses, and officers’ quarters, arranged according to one observer, in “fanciful order” (Brown 1999:79), loosely surrounded by palisaded fortifications and earthworks (Brown 1999:36,56). Bearing little resemblance overall to its sister fortification at Fort King (deep in the heart of Indian country, at

Stratigraphically, the Fort Brooke deposit consists of a dispersed but locally clustered occurrence of artifacts such as bottle glass, transfer-printed and shell-edged pearlwares and whitewares, crockery, pipestems and bowls, nails and iron hardware, and military items such as uniform buttons and lead shot. These artifacts occur in a thin brown-to-yellow sand matrix overlying or intruding upon the prehistoric Manasota deposits, within several inches to 4 ft. below the present ground surface (depending on the depth of modern fill), in the area generally south of Whiting Street (Piper and Piper 1987). Significantly, the Fort Brooke deposits contain a number of historical military, civilian, and Native American burials, some of which have been identified by archaeologists as Seminole Indians who died in captivity awaiting deportation to Indian Territory (Piper and Piper 1982; Piper et al. 1982; Weisman 1989). The attribution of these burials as ethnically Seminole and their pre-NAGPRA repatriation to the Seminole tribe by the City of Tampa lead to the 1984 creation mercantile and service sector formed around

all of the communities long before annexed by the city, and this primarily because long promo-tion of the area’s cultural heritage gave cred-ibility and legitimacy to those researching the history of the legendary cigar makers and their families. Even these excavations, commendable as they were, did not extend beyond ad hoc, last-minute, unfunded salvage operations involving graduate students as a training exercise (Piper and Piper 1976; Ellis 1977). In reviewing more than 50 archaeological project reports archived in the Florida master site file, it became appar-ent that while numerous investigations in urban Tampa have occurred since the mid-1960s, advancements in research design and theoretical perspectives have but inched forward. This article will begin with Ybor City.

Historical Archaeology in Ybor City

In 1885 the Tampa Board of Trade, represent-ing Tampa’s business interests, seized an oppor-tunity for economic development by inviting cigar manufacturer Vicente Martinez Ybor, then throttled by a labor strike in Key West, to begin anew by relocating his factories to 40 ac. of uninhabited scrub and swampland on the eastern outskirts of Tampa. Acting quickly to revive his enterprise, Ybor and several partners formed a land company, constructed several multistory brick cigar factories, and framed out the first of many famed casitas for the workers and their families, most of whom migrated from Cuba or Spain. When Italian (Mormino and Pozzeta 1990) and Jewish merchants and German lithog-raphers soon followed, little Ybor City presented quite a cosmopolitan flair and, when annexed by Tampa in 1886, brought its “Latin flavor” to the “cracker town,” in the words of local historian Tony Pizzo (Pizzo 1968). The entire saga of modern Florida’s boom-and-bust cycles played out in Tampa’s only National Historic Landmark District, as urban renewal cleaned up the 1960s bust, nightclubs and Bourbon Street–style bars occupied what had once been department stores and family restaurants, and stacks of high-end condominiums sit on lots where casitas once housed cigar workers and their families.

To the archaeologist, Ybor City presents a host of challenges and opportunities. It fits clearly within the paradigm of urban archaeology and has all the ingredients necessary to sustain

socially relevant, compelling research. Ybor City was a multiethnic community of immigrants, therefore issues of identity formation and mainte-nance threaded through the realities of everyday life. Racial tensions, already infusing life in the post-Reconstruction South, were here exacerbated by the presence of a small but prominent popu-lation of Afro-Cubans. Freed from Spanish slav-ery in Cuba, Afro-Cubans thrived in Ybor City by pushing the limits of acceptability, engaging in close-knit business ventures, and looking after their own interests (Greenbaum 2002). The cigar industry, as a capitalist enterprise, brought with it the inevitable division between workers and owners, thus the archaeologist might reasonably expect to find fruit in exploring the archaeology of class relations. The fact that both worker and owner were immigrants, identifying more strongly with each other than with the world of the American South surrounding them, adds intriguing complexity to conventional approaches to class relations and confounds easy expecta-tions about the ability of the archaeological record to yield the material correlates of class. For the thinking archaeologist, figuring all this out and expressing it in the form of a research remain, perhaps none more important than deter-mining the value of the archaeological record in answering questions of anthropological inter-est. The link between behavior and deposit, the crucial middle range of site-formation process (Rubertone 1982), has yet to be established. The Republica de Cuba excavation provides one example of why establishing this link can sometimes lead to the unexpected and completely reframe the perspective for understanding a site.

Republica de Cuba (8HI110): Site-Formation Processes in an Urban Environment

FiGURe 2. Republica de Cuba site on Hillsborough Community College campus in 2009, view to the north. the arguelles turkish Baths building is in the right background, now housing college administrative offices. (Photo by author, 2009.)

Ybor City campus (Figure 2). Eight 1 × 2 m units were staked out within the 50 × 100 m lot, and were excavated in natural levels down to cultur-ally sterile soil. In one unit, excavation reached a depth of 1 m below the surface, while the others were typically discontinued at depths of 40 to 50 cm below the surface (Haidar 1998:45,46). Some 4,000 artifacts were collected in the weekend’s work and were taken to USF. There they sat for 20 years, boxed and shelved, until graduate stu-dent Mary Haidar opened them up, released them from their bags, assembled the surviving field notes, and asked the question: Can the analysis of these artifacts, excavated 20 years before in hurried and imperfect field conditions, produce insights into the behavior of the people who once lived on this corner of Ybor City (Haidar 1998:2)? Quickly realizing that whatever happened on the site could not be understood without understanding its context within a neighborhood, Haidar recon-structed the population history of the surrounding

several such individuals, probably Afro-Cubans, populated almost exclusively by working-class people of immigrant origins, whose social and economic worlds were contained within the few blocks around their homes, but who were not immune to changing conditions brought in from the outside world.

For an archaeologist, the historical record cer-tainly is rich enough to generate a number of testable propositions about the use and role of material culture to indicate wealth, status, group membership, gender roles, family structure, divi-sion of labor, and the advent of consumerism, to name just some topics, in urban immigrant working-class populations of the early-20th-cen-tury South. In terms of developing an archaeo-logical research design, a project with such a solid historical base and cultural richness appears very promising, and it would be, except for one nearby homes and businesses. Its nearest neigh-bors were an auto painting and polishing business throughout the formerly thriving community: demolition by the wrecking ball of urban renewal (Mohlman 1995).

disturbance by the demolition process. Demolition demolition debris was spread.

The Republica de Cuba analysis was a direct can have serious, even traumatic, consequences for the people engaged with that space. The archaeology of the recent past is about people, yes, but people enmeshed in huge and complex social, political, and economic processes only partly within their control and realm of influence. Any anthropologically informed archaeological research design must first be based on a real-istic and informed appraisal of the archaeologi-cal record, for it is at once both maddeningly ephemeral and bewilderingly complex.

In Search of the Buffalo Soldiers: The Past in Service of the Present

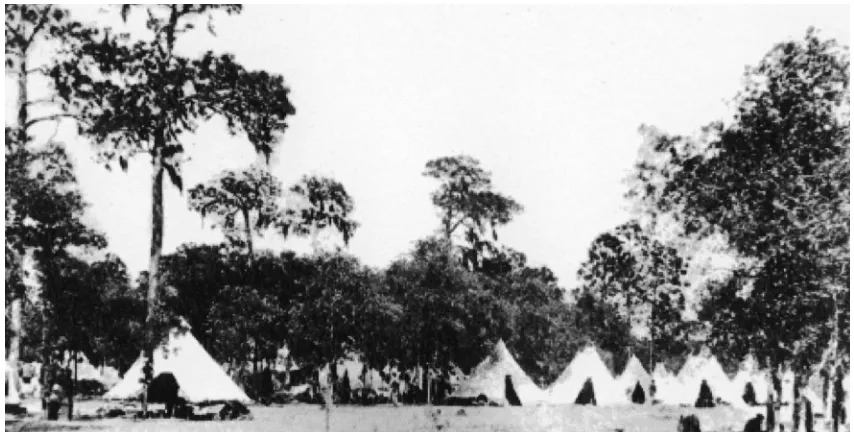

Called to the front lines with the quick mobi-lization of troops sent to invade Cuba during the Spanish-American War, the so-called buffalo sol-diers, African American regiments of the regular regiments through congressional order, the buf-falo soldiers had seen hard service at remote western outposts (Leckie and Leckie 2003), alter-nately engaged in either numbingly monotonous or extremely grueling tasks ( Kenner 1999) and

occasionally dispatched to enforce order among the Indian tribes, from whom they earned the respect-ful nickname “Buffalo” soldiers (Schubert 1995). Needless to say, the onslaught of nearly 3,000 their own incendiary journalism: “Negro Troops Still Trying to Run the Town—Situation Growing Serious,” proclaimed the Tampa Morning Tribune (1898) on 12 May, which helped propel the city to the brink of a race war, ultimately avoided only by the departure of the buffalo soldiers with the first invasion force steaming to Cuba during the second week of June.

by local black populations. Further, the arrival of drinking and little interested in padlocking well-known houses of prostitution. In came the buffalo soldiers to expose the double standard, demand-ing to have at whiskey, beer, and women, the American War approached, Florida’s department of state began soliciting proposals for projects commemorating Florida’s role in that conflict. I wondered, could that story be told through the lens of the buffalo soldier experience? That expe-rience had been wiped clean from the historical and cultural memory of Tampa. Other than a few idiosyncratic and short-lived efforts by local historians to situate the buffalo soldiers precisely within Tampa’s larger role as the major point of buffalo soldiers, their brief but dramatic sojourn in Tampa was largely ignored (Gatewood 1970; Mohlman 1999), their physical presence invisible. When the reality of Tampa’s highly contentious relegated to the dusty shelves of irrelevance?

Building the Archaeological Discovery Model

Mindful but undaunted, and with state fund-ing in hand, the project moved forward with a

Illinois Record (1898:1) (its out-of-state location undoubtedly contributing to the article’s positive spin) headlined “Colored Soldiers in Tampa,” subtitled “They Are Quick, Energetic, Painstak-ing and Thorough” and focusPainstak-ing on the 24th Infantry. The article showed keen observation of detail of great archaeological interest, noting, for example, that

[t]he streets are kept perfectly free from rubbish, and from a sanitary point of view no camp could be better conducted. At the mess kitchens and cook house gar-bage is not thrown out promiscuously as it is in the Cuban camps, for instance, but is cast into pits dug for the purpose, and when these are partially filled the sand is thrown in and the garbage buried.

Statements like these build archaeological models and kindle the archaeologists’ hopes of find-ing unintentional time capsules sealed tight in archaeological features.

Findings

To the field the team went, armed with mea-suring tapes, posthole diggers, shovels, screens, and metal detectors, and attracting, almost imme-diately, the earnest interest of the local press (Hawes 1997) and the begrudging attention of the homeless occupants of an underbrush-shrouded

back-corner camp. It was hoped at first to locate diagnostic military artifacts like buttons or equip-ment through use of a metal detector, naively it turned out (upon posthole testing), as modern metals blanketed the lots just below the surface. Without metal-detector hits to guide testing, the team simply established a grid across the six lots for which permission had been granted (each lot measuring about 60 ft. wide by 194 ft. deep), then dug 158 shovel tests (all but 7 yielding artifacts) at 10 m intervals. Plenty of artifacts were found, collected in 275 different proveniences, almost all of them, it turned out, relating to the residential development of the block that soon followed on the heels of the buffalo soldiers. A porcelain doll’s ear, a marble, a jack, hairpins, plastic beads, a comb, perfume bottles, coins (dating from 1930 to 1970), and, from what was most likely a trash dump or incinerator site against the back alley, large amounts of broken dishes and ceramics, glass bottles, utensils, an iron skillet, enamel pot, and a broken clock, all of which gave evidence of early suburban life in Tampa. Butchered animal bone and other faunal remains were also recovered in distributions suggesting kitchen-door deposition or backyard disposal. But where were the buffalo soldiers? At best, their activities were evidenced by no more than 16 artifacts spread across all six lots, none of them absolutely and specifically

diagnostic of a soldier, but most probably dating to the 19th century. These artifacts included a “REAL WOODSTOCK” kaolin pipe stem, lead shot and sprue, an “F” (for Federal) .22-caliber short rim-fire shell casing, three other shell cas-ings, a brass button or badge with an 1894 patent date, and several brass rivets and eyelets, conceiv-ably part of a tent. These paltry results would seem to spell doom for the success of the project, but, unexpectedly and fortunately, this turned out to be far from the case.

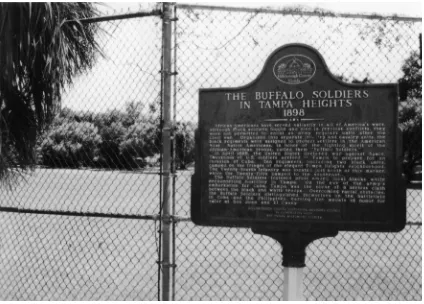

Heritage Making and Commemoration

While doing the fieldwork the team was also presenting public-education programs on the buffalo soldiers and developed a portable exhibit that made its appearance in several highly attended public venues associated with the Spanish-American War centennial. These activities plus the newspaper visibility brought supporters from

an unlikely place, namely the congregation of a church on the block adjacent to the survey area. This traditionally black church had recently opened its doors to a displaced white congregation and was attracted to a ready-made local historical example of blacks and whites working together for a common purpose, as they saw the black and white regiments doing in the Spanish-American War. To further the cause, one of the congregants, who also served on the Hillsborough County Historical Advisory Council, convinced the group to support the installation of a state historic marker on the corner of the survey block and across the street from the church. On 5 December 1998, this marker entitled “The Buffalo Soldiers in Tampa Heights 1898” was unveiled in a dedication ceremony featuring a 21-gun salute from a combined group of Rough Rider and buffalo soldier reenactors, a invocation by the church’s minister, and speeches by local politicians and community activists (Figure 4).

To the best of my knowledge, this is the only historical marker in existence offering public interpretation of the role of the buffalo soldiers in the Spanish-American War and is quite probably the only marker commemorating their activities east of the Mississippi River. As another measure of benefit, although the project cannot take entire credit, the buffalo soldiers have been included more frequently, even if still only slightly, in new local-history exhibits and public-education venues opening in the 10 years since the marker dedication. All of this started with a simple, small-scale archaeological survey. The message is clear: the act of archaeology itself, no matter how inconsequential the result, can bestow legitimacy and credibility to the process of heritage making in the modern world (Trouillot 1995) and can thus serve both political and social interests that might be quite distinct from those of the archaeologist. Public archaeology of the recent past can have unintended consequences, largely positive it is hoped, but not always or necessarily within archaeological control. The team also learned from working on Elmore Street that suburban life can imprint its own signature on the archaeological record and is a prime candidate for middle-range modeling.

Central Avenue: History Lost and Found

Few undertakings have had more profound effect on the physical and social fabric of modern Tampa than the construction and subse-quent widening of interstate highways through the core of its historic neighborhoods (Gedalius 2006) and the destruction and displacement resulting from urban renewal, often targeting those very same communities. Beginning with the construction of I-4 in 1963 and continuing to the present day with the massive widening of I-4 and I-275 (in some places to 10 lanes), several of Tampa’s oldest neighborhoods were literally cut in half (Gedalius 2006), with people and busi-nesses forced to flee, and those who did not or could not were forced to define a new network of connections in their new enclaves of exis-tence. These devastated communities made easy targets for ongoing federal- and city-funded urban renewal and its hope of promoting new kinds of neighborhoods that would thrive at the ends of interstate exits. The combined effects of these large-scale impacts are nowhere better evidenced

than in the Central Avenue district of Tampa, now flattened and largely submerged beneath the gargantuan cement cloverleaf linking I-4 and I-275 (known locally as “Malfunction Junction”). In its heyday during the 1940s when known as

2006), a free-form neighborhood of working-class or poor blacks in the no-man’s-land separating middle-class Central Avenue from Ybor City. For the archaeologist, Perry Harvey, Sr. Park provided the perfect setting—flat, open, unobstructed, the lure of a “lost city” right beneath the feet, its deposits nicely bracketed in time and presenting a range of historical contexts that have rarely been subject to systematic archaeological inves-tigation (Figure 6). If successful in producing meaningful archaeological results, this pioneering effort promised to put a truly urban archaeology on the larger map of Florida archaeology, its stars and dots until now almost entirely indicat-ing locations of prehistoric sites.

Further, engaging in a visible, relatively large-scale project right in peoples’ front yards made the team’s presence both difficult to avoid and the perfect venue for public archaeology, the very setting FDOT was interested in exploring as part of a new approach to their compliance

practices. Could archaeologists engage the local residents in the quest for the early history of their neighborhood? What would the message be about the value of learning about this history through archaeology? Answering these ques-tions became a major challenge to the project, despite going in with a community engagement plan. Allowing open access to work in progress brings a certain democracy to an enterprise, as people moving about in the course of their daily routines, peering into open units, bring questions and observations to the project that might go unexpressed in more formal focus-group settings. At night team archaeologists often sat up devel-oping new flyers or posters in response to the questions of the day, often written to confront the skepticism expressed by local residents about the value of what was being done. It became clear day by day that this community, like many modern communities, was composed of people who had different points of view and who chose

to engage with the outside world with varying levels of interest. Some eyed the archaeological team with suspicion, others altered their normal routes to avoid passing by. But, by turning that first shovel load of dirt, the genie had been let out of the bottle. Now something had to be found to validate the community history that the team promised lay buried beneath the sod.

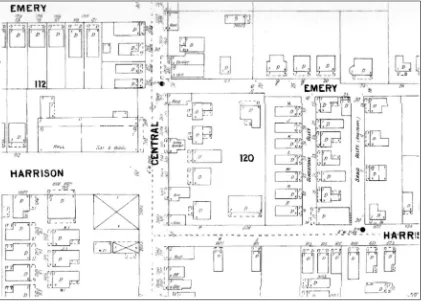

Archaeological Discovery

Study was focused on a one-block stretch of Central Avenue (most of it within Block 120) that throughout its history had a consistent mix of businesses and residential properties, and also was contained largely within the open field of Perry Harvey Park (Figure 7). The team devel-oped a set of four broad research questions relevant both to modern social urban processes and to the specific history of Tampa, and then described the archaeological requirements for

investigating these questions in the ground. First, the team wanted to know if the earliest docu-mented businesses of Central Avenue, dating to the 1880s and 1890s, were connected to local, state, regional, national, and international com-mercial networks and markets. Beneath this question was another: Did the early consumers of Central Avenue have access to the same goods that were for sale to consumers in Tampa and Ybor City? Did being a consumer on Central Avenue mean something different than being a consumer elsewhere in Tampa? The most direct archaeological test would be to find glass bottles associated with a well-documented 1890s saloon.

Next, the team wanted to know if the residents of Central Avenue were able to participate fully in the local economy, the shops, businesses, and services available right outside their front doors. Would the material record reflect their member-ship in the middle class? To answer this, it would be necessary to find refuse deposits associated

with these households. Third, the team wanted to find out if economic or class distinctions within the African American community were evidenced in the archaeological record. Looking specifically for the remains of houses along the Gladstone Alley portion of the Scrub, it was hoped to find backyard midden deposits that would contain a wide range of artifacts, including animal bone and food refuse, enabling the reconstruction of the daily life of this community. Finally, the team wanted to see if the flow of capital and the history of capital improvements produced an archaeological signature that could be compared with capital investments elsewhere in Tampa. Of specific and compelling interest, given the eventual outcome that all of Block 120 was demolished in urban renewal, could this fate be predicted by the presence of archaeological indicators signal-ing economic decline? Archaeologically the team needed to look broadly at land use patterns and go

deep stratigraphically to find evidence of capital improvements in construction sequences.

To be successful, the archaeological team needed to find reasonably intact deposits in the right places and containing the right kinds of materials. It was decided not to leave this to chance, but to instead develop a targeted excava-tion plan. The quesexcava-tions had to fit the deposits. The team had a detailed knowledge of the San-born maps and a good understanding of how the maps correlated to the modern landscape. The team knew the kinds of deposits and contexts needed to answer the research questions and so had the elements of a predictive model. The team was fully aware that it would take the excavation of large units to meet the archaeological require-ments, but wanted to minimize the effort spent in needless excavation. Multiple trips were made to the project area, maps and historical photographs in hand, and repeated surface inspections were

conducted in an attempt to identify locations where surficial deposits might indicate the pres-ence of buried remains. Although helpful and showing promise, surface collection alone was inadequate for further defining target areas, so a grid of quickly completed posthole tests was used to provide an initial characterization of soil deposits, which, when added to the predictive model, greatly increased confidence in success. The archaeological team then moved forward to open six excavation units, specifically placed to yield the kinds of remains necessary to answer its research questions. It was also important to open all units as simultaneously as possible to allow for the development of a master strati-graphic profile and to test ideas about relation-ships between deposits during excavation, rather than in a later analysis stage. investment/land-use question, and it was hoped the unit would show a stratigraphic sequence research projects (Logan-Hudson 2004; O’Brien 2004). The academic products of this project will be slow in coming. The public results, however, have been more immediate. Selected artifacts have traveled back to the community in heritage

Beyond artifacts, Central Avenue excavations reinforce the awareness that the archaeology of the recent past has stratigraphic reality, that is, deposits ordered in an understandable sequence

and demonstrating archaeological integrity. This is an important realization in Florida archaeol-ogy, where too often these deposits are written multi-intrusive layers or lenses present along Central Avenue itself (buried but evident) and its strip of commercial buildings, and domestic midden levels characterizing the deposits to the east (behind the commercial strip), increasing in depth closer to the Scrub, where several feet of dark, artifact-rich soils come into contact with the white sand subsoil. A distinct demolition layer consisting of broken brick, twisted metal, broken glass, and concrete covers these occupational and commercial deposits across the site, thickest in the commercial area where the most substantial construction existed, clearly resulting from urban renewal. On top of the demolition layer is a fill the accumulation of artifacts relating to recent uses of the space by nearby residents of the Central Park Village public housing complex (razed in 2008 and slated to be covered over, adding yet another stratigraphic episode for archaeological study). As the team looks toward building a master stratigraphic profile for the city of Tampa, Central Avenue shows that attention must be paid to both demolition and fill layers as cultural deposits, reflecting the dramatic local effects of powerful extra-local forces whose seat of authority and control is far removed from the community. Demolition and fill are fundamental urban processes and represent a fundamental truth about the realities of power in city politics (Byles 2005:202–221). As made physically evi-dent in the archaeological record, any local story of demolition and fill should be one of the main narratives of urban public archaeology.

to be of no promise does in fact contain interpretable archaeological remains, the team came up short in successfully answering all of its research questions. As expected, questions that rely on the recovery and analysis of glass bottles or bottle glass have a good chance of being answered. Historical archaeologists recognized long ago the value of bottle glass for studying consumer behaviors (Baugher-Perlin 1982; Spencer-Wood 1987; Bond 1989). For the period after the mid-19th century, when rampant consumerism swept the world, and through the preplastic 20th century, the myriad attributes of bottle glass have proven useful in recognizing distribution and supply chains and market penetration into new population sectors. The studies of the Central Avenue glass, although far from complete, are focusing on analyzing the assemblage by functional category, location of manufacture (local, regional, East Coast, national), date ranges, and breakage and disposal patterns. The primary sample consists of 33 intact bottles and nearly 1,000 diagnostic shards, although these represent only a small percentage of total glass recovered. Glass bottles and containers are present in the earliest documented historical contexts (1890s) through the terminal deposits of the 1960s, with one major buried bottle-dump feature dating probably to the 1940s. African Americans of the Central Avenue community participated as consumers within the larger consumer-based economy, consumed a range of products that were widely available and reflect regional and national trends, and appear through the lens of archaeology not to be materially distinct in any dramatic way from society at large. This conclusion reinforces the more general interpretation of African American consumer behaviors in urban settings (Little and investigating the social and economic processes of community rise and fall. Six units, no matter how well placed, are not enough to answer complicated questions in a complex urban envi-ronment. It was evident, for example, that the broader interactions between the demolition, fill, and construction deposits relating to the transition

developing it as an urban riverfront park and botanical garden.

Working on the same FDOT grant that funded the Central Avenue Project, the team was here interested in using archaeology to broaden the value of a city landmark by shifting the focus away from the prominent built environment to buried archaeological deposits. The 1931 Sanborn map (the earliest for the area) enticed interest by showing several structures near the base of the then-nonfunctioning tower. One of these, the largest, was the pump house and continued to be in evidence as a standing structure through the 1980s. The second, a much smaller concrete-block building on the riverbank, vanished from maps and photographs after 1956 (USGS 1956, 1981). Could archaeology have a role in figur-ing out how this buildfigur-ing was used and what its importance was in the activities taking place around the functioning tower? Could archaeol-ogy here help to address the larger concern of

demonstrating to FDOT the value of community-based archaeology focusing on places or proper-ties that the community already deemed important to its heritage?

Talking with local historians confirmed what was already suspected: the small block house had once been the residence of the caretaker and his family in the 1930s. The quest for this family meant that a human dimension could be added to the research design. What could be learned about the life and work of the caretaker and his family through archaeology? Although their identities remain unknown, could archae-ology help bring them back to life and situate them in the context of the times in which they lived? Possibly, but first the team had to find an archaeological deposit to investigate. Nothing of the structure itself remained and the immedi-ate area of the house had been seriously altered over the years. As the team walked the site, bottles and cans were noticed sticking out of

the exposed riverbank near where the house had been, and more of the same littering a small sandbar at the base of the bank on the edge of the river. This looked to be a deep and extensive dump, cascading down over the side of the bank in what appeared to be discernible layers of trash (Figure 10). If evidence of the caretaker were to be had, it was hoped to find it there.

Excavating this feature turned out to be more complicated than anticipated. The team opened up three 5 × 5 ft. units to sample different areas of the deposit. The upper levels contained numerous ash deposits, tin-foil balls likely used to wrap food cooked directly in a fire, plastics, paper, burnt and fused metals and glass, and other indications of recent (perhaps clandestine) use of this area of the riverbank. The team also encountered numerous artifacts that it did not recognize and had not seen previously in archaeological sites, like hundreds of carbon rods, at 3.5 in. long about the size of a small ballpoint pen, used in industrial-sized lamps (like

searchlights) and projectors. These could have come from the adjacent drive-in movie theater, which operated from 1952 to 1985, or from the beacon mounted atop the tower in the 1950s and 1960s. The Coca-Cola bottles found in the upper levels could certainly have been dumped from the theater, as the bottle styles date from 1951 to 1965. Going deeper, the team found that bever-age glass and tin cans dominated the assemblbever-age. Thin sand lenses were evident also in the artifact layers, possibly indicating flood deposits from the rising river. Clusters of nested bottles and associ-ated artifacts indicassoci-ated single dumping episodes (Figure 11). Then there were the glass canning jars, baking dishes, perfume and cosmetic bottles, and cutlery, indicating domestic use of the site, perhaps by the caretaker’s family in the 1930s. Finding 1919, 1929, 1944, 1953, and 1954 pen-nies, a 1948 nickel, and a 1942 Mercury dime helped document the periods of active dumping. Ultimately, more was learned about the com-munity’s historical attitudes toward land use than

about specific individual behaviors. What started out as a family dump over the riverbank––“out of sight, out of mind”––became the customary and accepted dumping ground for neighboring businesses, and then became accepted as a itiner-ant camping spot. In the years before municipal garbage collection and as a much cheaper alter-native to commercial hauling, people felt justified in disposing their trash in a dedicated spot, here assuming or hoping the river would carry it away or make it magically disappear. This general behavior is evident throughout Florida as areas now valued for their natural beauty often turn out to harbor piles of trash dumped by earlier pioneers or homesteaders, concerned more with scratching out a living than with environmental aesthetics. At the Sulphur Springs Water Tower, the dump reflects a composite of distinctly separate activities by different groups of people at different times, all of which combined to set this site aside as a dedicated dumping ground for neighborhood activities.

Media coverage (Lengall 2003), based on the novelty factor of archaeologists working in plain view in the everyday world doing the archaeol-ogy of “us,” led to a high level of community interest and also made the city realize that the property around the iconic tower might hold important, unrecognized historical resources. To evaluate better proposed impacts to site 8HI8937 (as it came to be designated) resulting from their planned improvements to the property, the city retained a private firm for additional archaeologi-cal study. This study concluded that the proposed grading of the riverbank associated with park development could indeed negatively affect an historical resource (Panamerican Consultants 2004:29). Here can be seen, for the first time to the best of my knowledge, an archaeological resource in Tampa dating exclusively to the early to mid-20th century deemed sufficiently important to require further attention or avoidance. Further, this one small example suggests that archaeology can usefully and routinely partner with historic

preservation efforts to enrich and expand the public interpretation of historical structures such as cigar factories, bottling plants, schools, hospi-tals, or theaters.

Conclusions

The grip of prehistory is strong, its archaeo-logical record immensely rich, but the tangibles of the recent past carry unexpected power in their ability to connect with people in direct and very personal ways. The recent past can be productively investigated through archaeol-ogy if archaeologists only expand their view of whom and what comprise the proper subjects of archaeological investigation. An interpretable archaeological record does exist and can become known through standard archaeological techniques and the application of proven archaeological

principles such as stratigraphic analysis. Beyond the level of proving itself worthy, this archaeol-ogy provides a unique view of the materiality of the very recent human experience, and thus, like all good archaeology, forces people to take a critical look at the inseparable link between human action and the world it creates.

In Florida, where the archaeological pursuit of the recent past is only now gaining legitimacy, relatively small-scale projects in an urban set-ting indicate the potential of public archaeology and the feasibility of building citywide models of archaeological site formation. Such models would be valuable to cultural resource manag-ers by enabling them to develop more specific and coherent research designs based on the depositional history of the city. In Tampa, by city ordinance, archaeological deposits associated with pre–Civil War Fort Brooke are regularly

tested and assessed because they fall within the Central Business District, but postbellum and 20th-century deposits are not systematically addressed here or in Tampa’s historic neighbor-hoods. In not linking archaeology to publicly popular preservation causes, opportunities are missed for demonstrating the relevance of archaeological knowledge. The recent location of the west central Florida office of the statewide Florida Public Archaeology Network (FPAN) on the University of South Florida campus might help gain greater public visibility for previously neglected archaeological resources.

Archaeological knowledge of the recent past must be highly integrative given the wealth of documentary sources available, but it can also stand on its own. Asking the question: What kinds of deposits penetrate (are directly intrusive into) or come into contact with the subsoil? puts archaeological inquiry on its own footing and anchors human activity directly in the environ-ment. In Tampa’s Scrub neighborhood, deep dark backyard midden deposits contact or penetrate the underlying white “scrub” sand, while a block to deposit. Derelict landscapes (Jackle and Wilson 1992) are created, covered over, and made new and still are largely ignored. Tourism, transporta-tion, and the Cold War (National Park Service 2004) all provide sites that can be productively investigated, not to mention confinement sites such as WWII prisoner-of-war camps, quar-conventional concerns with ethnicity, wealth, and status. When archaeology helps illuminate the hidden realities of the recent past it enlightens Florida Department of Transportation, students in the 2003 USF archaeological field school, former

BaUgher-PerLin, Sherene

1982 Analyzing Glass Bottles for Chronology, Function, and Trade Networks. In Archaeology of Urban America: The Search for Pattern and Process, Roy S. Dickens, Jr., editor, pp. 259–289. Academic Press, New York, NY.

BeLLUSh, JeWeL, and MUrraY haUSknecht (editorS)

1967 Urban Renewal: People, Politics, and Planning. Doubleday Anchor, Garden City, NY.

Bond, kathLeen h.

1989 The Medicine, Alcohol, and Soda Vessels From the Boott Mills Boardinghouses. In Interdisciplinary Inves-tigations of the Boott Mills, Lowell Massachusetts, Volume 3: The Boarding House System as a Way of Life, Cultural Resource Management Study No. 21, Mary C. Beaudry and Stephen A. Mrozowski, editors, pp 121–139. Report to National Park Service, North Atlantic Regional Office, Boston, MA, from Center for Archaeological Studies, Boston University, Boston, MA.

Brooke, george M.

1959 Letter to the Adjutant General, 2 January 1829. In The Territorial Papers of the United States, the Territory of Florida, Volume 24, 1828–1834, Clarence E. Carter, editor, p. 128. National Archives, Washington, DC.

BroWn, canter, Jr.

1999 Tampa Before the Civil War. University of Tampa Press, Tampa.

BroWn, connie J.

2004 Mapping a Generation: Oral History Research in Sulphur Springs, FL. Master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of South Florida, Tampa.

BYLeS, Jeff

2005 Rubble: Unearthing the History of Demolition. Har-mony Books, New York, NY.

cantWeLL, anne-Marie, and dianadi zerega WaLL

2001 Unearthing Gotham: The Archaeology of New York City. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

catteLino, JeSSica r.

2008 High Stakes: Florida Seminole Gaming and Sover-eignty. Duke University Press, Durham, NC.

citYof taMPa

1989 Landmark Designation Report for the Sulphur Springs Water Tower. Manuscript, City of Tampa, Architectural Review Commission, Tampa, FL.

dickenS, roY S., Jr. (editor)

1982 Archaeology of Urban America: The Search for Pattern and Process. Academic Press, New York, NY.

dickenS, roY S., Jr., and WiLLiaM r. BoWen

1980 Problems and Promises in Urban Historical Archae-ology: The MARTA Project. Historical Archaeology

14:42–57.

digitaLgLoBe

2002 Quickbird Scene Catalog, ID: 10100100015FBD01. DigitalGlobe, Longmont, CO.

eLLiS, garY d.

1977 8HI426: A Late19thCentury Historical Site in the Ybor City Historic District of Tampa, Florida. Master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of South Florida, Tampa.

fLorida diviSionof hiStoricaL reSoUrceS

1996 Statewide Comprehensive Historic Preservation Plan. Manuscript, Florida Division of Historical Resources, Department of State, Tallahassee.

froehLich, JaniS d.

2003a Reclaiming the Glory. Tampa Tribune Baylife 8 June:1,11. Tampa, FL.

2003b Anthropology Class, Children Dig into City’s Black History. Tampa Tribune 15 June:B1,B9. Tampa, FL.

garroW, Patrick h.

1995 Archaeological Investigations of the Courthouse Block, Knoxville, Tennessee. Report to Barber and McMurry, Inc., Knoxville, TN, and General Services Administra-tion Historic PreservaAdministra-tion Office, from Garrow and Associates, Atlanta, GA.

gateWood, WiLLard B., Jr.

1970 Negro Troops in Florida, 1898. Florida Historical Quarterly 49(1):1–15.

gedaLiUS, eLLen

2006 Interstates Divided and Connected. Tampa Tribune 29 June:A-1,A-6,A-7. Tampa, FL.

greenBaUM, SUSan d.

1998 Central Avenue Legacies: African American Heritage in Tampa, Florida. Practicing Anthropology 20(1):2–5. 2002 More Than Black: Afro-Cubans in Tampa. University

Press of Florida, Gainesville.

haidar, MarY

1998 Twenty Years in a Box: Analysis of Artifacts From Ybor City, Florida, 20 Years After Excavation. Mas-ter’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of South Florida, Tampa.

hardin, kenneth W., and roBert J. aUStin

1987 A Preliminary Report on the Bay Cadillac Site: A Prehistoric Cemetery in Tampa, Florida. The Florida Anthropologist 40 (3):233–234.

haWeS, LeLand

1997 On the Trail of the Buffalo Soldiers. Tampa Tribune Baylife 21 December:1. Tampa, FL.

2004 Cigars, Culture, Church Enriched Life in Scrub. Tampa TribuneBaylife 22 February:6. Tampa, FL.

hendrYand knight

hendrYx, greg, BoB aUStin, deBra WeLLS, and Brian

Worthington

2009 An Overview of Recent Excavations at Fort Brooke, a Seminole War and Civil War Military Outpost in Hillsborough County, Florida. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Florida Anthropological Society, Pensacola.

hiLLSBoroUgh coUntY

1998 Hillsborough County Historic Resources Survey Report. Report to Florida Department of State, Bureau of Historic Preservation, Tallahassee, FL, from Hill-sborough County Planning and Growth Management Office, Tampa, FL.

IllInoIs RecoRd

1898 Colored Soldiers at Tampa: They Are Quick, Energetic, Painstaking, and Thorough. Illinois Record 18 June:1. Springfield.

JackLe, John a., and david WiLSon

1992 Derelict Landscapes. Rowman and Littlefield, Savage, MD. 1867–1898. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Leckie, WiLLiaM h., and ShirLeY a. Leckie

2003 The Buffalo Soldiers: A Narrative History of the Black Cavalry in the West. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

LengaLL, Sean

2003 USF Team Digging Up Tampa’s Past. Tampa Tribune

5 June:1–2. Tampa, FL.

LittLe, BarBara J., and nancY J. kaSSner

2001 Archaeology in the Alleys of Washington, DC. In The Archaeology of Urban Landscapes, Alan Mayne and Tim Murray, editors, pp. 57–68. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Logan-hUdSon, kiMBerLY

2004 An Analysis of Glass Bottle Artifacts of Site 8HI4561. Bachelor honor’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of South Florida, Tampa.

Long, karen haYMon

2006 Restoration to Light Up a Cigar City Icon. Tampa Tribune Baylife 19 November:7–10. Tampa, FL.

LUSh, taMara

2003 The Dig for Historic Gold. St. Petersburg Times 11 June:B1,B7. Tampa, FL.

Mahon, John k.

1967 History of the Second Seminole War, 1835–1842. University of Florida Press, Gainesville.

MaYne, aLan, and tiM MUrraY (editorS)

2001 The Archaeology of Urban Landscapes: Explorations in Slumland. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

MaYS, B. e., arthUr raPer, and J. h. McgreW

1927 A Study of Negro Life in Tampa, Made at the Request of the Tampa Welfare League and the Tampa Young Men’s Christian Association. Manuscript, University of South Florida Library, Special Collections, Tampa.

MikeLL, gregorY a., LiSa n. LaMB, and carroLL B. BUtLer

2003 Archaeological Site Testing and Evaluation of Eleven Naval Stores Sites within the Eglin Air Force Base, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, and Walton Counties, Florida. Report to Ecology and Environment, Lancaster, NY, from Panamerican Consultants, Tampa, FL.

MikeLL, gregorY a., and LiSa n. QUinn

2004 Archaeological Site Testing and Evaluation of Twenty Selected Pioneer and Early Rural Industrial Expan-sion Period Sites within the Eglin Air Force Base, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, and Walton Counties, Florida. Report to Ecology and Environment, Lancaster, NY, from Panamerican Consultants, Tampa, FL.

MohLMan, geoffreY

1995 Bibliography of Resources Concerning the African American Presence in Tampa, 1513–1995. Master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of South Florida, Tampa.

1999 “An Insult and a Blow”: The Buffalo Soldiers at Tampa Bay. In Soldier and Patriots: Buffalo Soldiers and Afro-Cubans in Tampa, 1898, Brent R. Weisman, editor, pp. 20–83. University of South Florida, Department of Anthropology, USF Studies in Historical Archaeology, No. 2. Tampa, FL.

Morgan, PhiLiP

2002 Relics, Ruins, and Rebirths. Tampa TribuneBaylife 22 October:1,6. Tampa, FL.

MorMino, garY

2005 Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams: A Social His-tory of Modern Florida. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

2006 Life in the Scrubs. Tampa TribuneBaylife 27 August:10. Tampa, FL.

MorMino, garY r., and george e. Pozzetta

1990 The Immigrant World of Ybor City: Italians and Their Latin Neighbors in Tampa, 1885–1985. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

nankiveLL, John h.

2001 Buffalo Soldier Regiment: History of the Twenty-fifth United States Infantry, 1869–1926. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

nationaL Park Service

o’Brien, MattheW

2004 An Examination of the Usefulness of Posthole Digging in Archaeological Sampling Strategies: A Case Study From 8HI4561. Bachelor honor’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of South Florida, Tampa.

PanaMerican conSULtantS, inc.

2002 An Archaeological and Historical Survey of the Perry Harvey Senior Park, Downtown Tampa, Hillsborough County, Florida. Report to Award Engineering and the City of Tampa, FL, from Panamerican Consultants, Tampa, FL.

2004 An Archaeological and Historical Survey of the River Tower Property Project Area in Hillsborough County, Florida. Report to Ash Engineering, Tampa, FL, from Panamerican Consultants, Tampa, FL.

PiPer archaeoLogY/JanUS reSearch

1992 A Cultural Resource Assessment Survey of the Tampa Interstate Study Activity A, Task II (EIS) Project Area Including the Proposed Crosstown Connector and the South Tampa Crosstown Expressway Improvements. Report to Greiner, Inc., Tampa, FL, and the Florida Department of Transportation, Tallahassee, from Piper Archaeology/Janus Research, St. Petersburg, FL.

PiPer, harrY M., and JacQUeLYn g. PiPer

1976 Archaeological Survey Notes, Republica de Cuba Site. Manuscript, University of South Florida, Department of Anthropology, Archaeology Laboratory, Tampa. 1982 Archaeological Excavations at the Quad Block Site,

8HI998. Report to the City of Tampa, from Piper Archaeological Research, St. Petersburg, FL. 1987 Urban Archaeology in Florida: The Search for

Tampa’s Historic Core. The Florida Anthropologist

40(4):260–265.

1993a Locating Fort Brooke Beneath Present-Day Tampa.

The Florida Anthropologist 46(3):151–158. 1993b A Nineteenth-Century Cooling House. The Florida

Anthropologist 46(3):159–161.

PiPer, harrY M., kenneth W. hardin, and JacQUeLYn

g. PiPer

1982 Cultural Responses to Stress: Patterns Observed in American Indian Burials of the Second Seminole War.

Southeastern Archaeology 1(2):122–137.

Pizzo, anthonY P.

1968 Tampa Town: 1824–1886, The Cracker Village With a Latin Accent. Trend House, Tampa, FL.

PraetzeLLiS, MarY (editor)

1994 West Oakland—A Place to Start From. Research Design and Treatment Plan, Cypress I-880 Replace-ment Project, Vol. 1: Historical Archaeology. Report to California Department of Transportation, Sacramento, from Anthropological Studies Center, Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park, CA.

Proctor, SaMUeL

1996 Prelude to the New Florida, 1877–1919. In The New History of Florida, Michael Gannon, editor, pp. 266–286. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

roULeaU, charLeS t.

1966 Fifth U.S. Army Corps, Tampa, Florida 1898, Spanish-American War. Map, Special Collections, University of South Florida Library, Tampa.

rUBertone, Patricia f.

1982 Urban Land Use and Artifact Deposition: An Archaeo-logical Study of Change in Providence, Rhode Island. In Archaeology of Urban America: The Search for Pattern and Process, Roy S. Dickens, Jr., editor, pp. 117–142. Academic Press, New York, NY.

1995 Overseas Heritage Trail Research: A Search for the Remains of the Florida East Coast Railroad, Monroe County, Florida. Report to Florida Department of Transportation District 6, Miami, from Florida Envi-ronmental Services, Inc., Report of Investigations, No. 66. Jacksonville.

SMith, greg c. and vicki L. roLLand

1996 Keep Your Lamps Trimmed and Burning: Archaeologi-cal Testing at the St. Augustine Lighthouse, St. Johns County, Florida. Report to Junior Service League, Inc. of St. Augustine, Florida, from Florida Environmen-tal Services, Inc., Report of Investigations, No. 97. Jacksonville.

SPencer-Wood, SUzanne M. (editor)

1987 Consumer Choice in Historic Archaeology. Plenum Press, New York, NY.

StaSki, edWard (editor)

1987 Living in Cities. Current Research in Urban Archaeol-ogy. The Society for Historical Archaeology, Special Publications Series, No. 5. California, PA.

taMPa Morning triBUne

1898 The Negro Troops, Still Trying to Run the Town, Situation Growing Serious. Tampa Morning Tribune

12 May:2.

1898 Negro Murderers. Tampa Morning Tribune, 17 May:1. 1898 Soldiers Wreck Saloons, Mob of Negroes and Whites Prove Themselves to be Thieves. Tampa Morning Tribune 8 June:4.

troUiLLot, MicheL-roLPh

United StateS geoLogicaL SUrveY (USgS)

1956 Sulphur Springs, Florida, Quadrangle Map, 7.5 minute series. U.S. Geological Survey, Washington, DC. 1981 Sulphur Springs, Florida, Quadrangle Map, 7.5 minute

series. U.S. Geological Survey, Washington, DC.

WeiSMan, Brent r.

1989 Like Beads on a String: A Culture History of the Semi-nole Indians in North Peninsular Florida. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

1999 Unconquered People: Florida’s Seminole and Micco-sukee Indians. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

WeiSMan, Brent r. (editor)

1998 Guiding Light to Safe Anchorage: An Archaeological and Historical Survey of the Anclote Keys Light Station. Report to Florida Division of Historical Resources, Tal-lahassee, from Department of Anthropology, University of South Florida, Tampa.

1999 Soldiers and Patriots: Buffalo Soldiers and Afro-Cubans in Tampa, 1898. University of South Florida, Department of Anthropology, USF Studies in Historical Archaeology, No. 2. Tampa.

WeiSMan, Brent r., and Lori d. coLLinS

2004 A Model for Evaluating Archaeological Site Signifi-cance in Cities: A Case Study From Tampa, Florida. Report to Florida Department of Transportation, Central Environmental Management Office, Tallahassee, from Department of Anthropology, University of South Florida, Tampa.

YoUng, aMY (editor)

2000 Archaeology of Southern Landscapes. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Brent r. WeiSMan

dePartMentof anthroPoLogY