On-the-job management training and multicultural

skills: the moderating effect of openness to

experience

Milan Pagon*

Al Ghurair University, P.O. Box 37374, Dubai, UAE Fax: +971-4-4200224 E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author

Emanuel Banutai

Faculty of Criminal Justice and Security, University of Maribor,

Kotnikova 8, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia Fax: +386-1-2302-687

E-mail: [email protected]

Uroš Bizjak

University of Iowa – CIMBA,

Via San Giacomo 4, 31017 Paderno del Grappa, Italy Fax: +39-0423-951104

E-mail: [email protected]

Abstract: This study examined the effects of on-the-job management training on the incumbent public administration managers’ multicultural skills as a function of the managers’ openness to experience. Two hundred eighty four public administration managers from the European Commission and 26 member states participated in the study. The results indicate that on-the-job training (including the initial training, informal training, mentoring, coaching, and the availability of resources) improve the incumbent managers’ multicultural skills, but only when the managers are moderate or high in openness to experience. The multicultural skills of the managers who are high in openness to experience benefit from on-the-job training the most, followed by the skills of the managers who are moderate in openness to experience. When the managers are low in openness to experience, the increased amounts of on-the-job training actually decrease their level of multicultural skills.

Keywords: management training; multicultural skills; openness to experience; public administration.

Biographical notes: Milan Pagon is a Professor of Management at Al Ghurair University in Dubai, UAE. He received his DSc in Organisational Sciences from the University of Maribor, Slovenia, and his PhD in Business Administration from the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, USA. Prior to his current position, he served as a Professor at the University of Maribor, Slovenia, Adjunct Professor at the University of Iowa, USA, as well as Visiting Professor at the Middle East Technical University, Northern Cyprus Campus, and the University of Arkansas, USA, among others.

Emanuel Banutai is a young Researcher at the Faculty of Criminal Justice and Security, University of Maribor, Slovenia. He received his BA in Criminal Justice and Security from the same institution. Prior to his current position, he worked as an intern at the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Slovenia. He is currently pursuing his PhD at the Faculty of Organisational Studies, University of Maribor, Slovenia.

Uroš Bizjak is an undergraduate Campus Life Coordinator at the University of Iowa – CIMBA Italy. He received his BSc in Management Information Systems from the University of Maribor, Slovenia. Prior to his current position, he worked as a Student Assistant at the Faculty of Organisational Sciences and as an intern at the Slovenia Control – Slovenian Air Navigation Company. He is currently pursuing his MBA at the University of Iowa – Henry B. Tippie College of Business.

1 Introduction1

Multicultural skills (MCS) can be understood as a subset of intergroup competencies (Ramsey and Kantambu Latting, 2005) and collaborative competencies (Getha-Taylor, 2008), but focus specifically on working with people and issues originating from cultures other than one’s own.

Pagon et al. (2009) found MCS to be significantly and positively correlated with openness to experience and on-the-job training. In this paper, however, we want to explore the interaction between openness to experience and on-the-job training in their relation to MCS.

In terms of the Fink and Mayrhofer’s (2009) framework, this is a personal-level study. It does not investigate the culture; rather, it focuses on personality and its impact upon the relationship between on-the-job training and MCS. While we agree with Fink and Mayrhofer (2009) that “people in their behavior are not mechanistically determined by values, norms and personality traits, but rather guided in their behavioral choices and also are willing and capable to learn” (p.45), we also believe that their capacity to learn is itself influenced by their personality.

openness to experience is “a trait dimension that affects nearly every aspect of the individual’s life”.

In previous research, openness to experience has been related to various aspects of MCS and settings. Summarising the research findings, Ang et al. (2006) conclude that working with people from different cultures can be difficult for individuals and for their organisations because cultural barriers can cause misunderstandings and interfere with efficient and effective interactions. The authors describe those individuals high on openness to experience as

“… curious and enjoy trying to figure out new things. In other words, they adopt metacognitive strategies when thinking about and interacting with those who have different cultural backgrounds. In addition, those who are high in openness should be more likely to question their own cultural assumptions, analyze the cultural preferences and norms of others (before and during interactions), and reexamine their mental models based on interactions with those from other cultures… They should be more knowledgeable about specific aspects of other cultures… They are also willing to experience and enjoy new and unfamiliar environments… [They] seek out, act on new experiences, and extend their repertoire of behaviors beyond the daily habits.” (pp.108–109)

Their results showed that openness to experience was related to all four factors of CQ (cultural intelligence), namely metacognitive, cognitive, motivational, and behavioural CQ. The authors emphasise the importance of openness to experience, particularly in dynamic situations where curiosity, broad-mindedness, and imagination are important. Therefore, openness to experience is a crucial personality characteristic that is related to a person’s capability to function effectively in diverse cultural settings (Ang et al., 2006). MCS not only require learning but also the development of different, more appropriate, and possibly counterintuitive ways of doing things (cf. Le Pine et al., 2000).

Homan and colleagues (2008) found that there are differences in how teams experience their diversity. Diverse teams that score high on openness to experience perform better than diverse teams that score low on this characteristic. When differences within a team are salient, openness to experience helps teams to capitalise upon their differences.

But not only has openness to experience been linked to MCS and dealing with diversity; this personality construct was found to be a valid predictor of training proficiency (Barrick and Mount, 1991; Salgado, 1997). In a meta-analytic review of research on the big five, Barrick and Mount (1991) found a corrected correlation of .25 between openness and learning proficiency across five occupational groups. According to the authors, measures of openness to experience may identify which individuals are most willing to engage in learning experiences and, consequently, are most likely to benefit from training programmes. Cellar et al. (1996; cited in Colquitt et al., 2002) showed that open individuals received more favourable training evaluations in the context of flight attendant courses.

assessment that is necessary for learning in changing task contexts (Blickle, 1996; Busato et al., 1999 – both cited in Le Pine et al., 2000).

At the same time, on-the-job training has been linked to improved cognitive and behavioural cultural intelligence (Grigorian, 2008) and higher level of MCS (Pagon et al., 2009). Therefore, since both openness to experience and on-the-job training are related to cultural skills, and since openness to experience was found to be a predictor of training proficiency, we hypothesise as follows.

Hypothesis On-the-job-training and openness to experience interact to predict the level of MCS: relative to managers with lower levels of openness to experience, managers with high levels of openness to experience benefit from higher levels of on-the-job training.

2 Methods

2.1 Sample

Two hundred eighty four public administration managers from the European Commission and 26 Member States participated in the study. One hundred fifty three (54%) of the subjects were male and 130 (46%) were female. The mean age of the subjects was 46.2 years. Sample included 41 (14.5%) subjects with a doctoral degree, 138 (49%) had a master’s degree, 95 (33.7%) had a university degree, and 8 (2.8%) subjects had a high school degree or less. One hundred seventy two (61.2%) subjects reported being in the rank of middle management, while 109 (38.8%) indicated the rank of top management. The average amount of work experience of the subjects was 21.4 years; the average amount of work experience in public administration was 16.5 years; and the average amount of work experience at the current institution was ten years. The mean amount of work experience in the current position was 3.6 years.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Multicultural skills

We developed a 7-item scale measuring MCS. Sample items were: “I feel confident conducting a meeting in a foreign language”, “I feel confident working with and/or supervising people from other cultures”, and “I participate effectively in multicultural teams”. The respondents indicated their answers on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 – strongly disagree; 7 – strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .78.

2.2.2 On-the-job training

institution, funds for development and innovation are readily available”. The response format was the same as in the previous scale. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .79.

2.2.3 Openness to experience

We used a 4-item Openness to Experience subscale from the Mini IPIP Scales (Donnellan et al., 2006). Sample items were: “I have vivid imagination”, and “I am not interested in abstract ideas (reverse-scored)”. The response format was the same as in the previous scales. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .61.

2.3 Procedure

This study was a part of a broader study conducted for the Human Resource Working Group (HRWG) of the European Public Administration Network (EUPAN) under the Slovenian Presidency of the EU, and was financially supported by the Slovenian Ministry of Public Administration.

We used an online questionnaire, published at http://www.surveymonkey.com. The link to the questionnaire was distributed to public administration managers by the HRWG members in their respective countries. The rationale for the study was explained to the HRWG members at two meetings (in Brdo, Slovenia, and in Brussels, Belgium). Participation in the study was voluntary.

3 Results

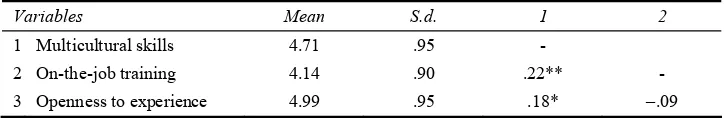

The means, standard deviations, and correlations for the variables of interest are reported in Table 1.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics and correlations

Variables Mean S.d. 1 2

1 Multicultural skills 4.71 .95 -

2 On-the-job training 4.14 .90 .22** -

3 Openness to experience 4.99 .95 .18* –.09

Notes: *p < .05; **p < .001 and ***p < .0001.

As reported previously (Pagon et al., 2009), MCS are significantly and positively correlated with openness to experience and on-the-job training. The amount of on-the-job training and openness to experience are not significantly correlated.

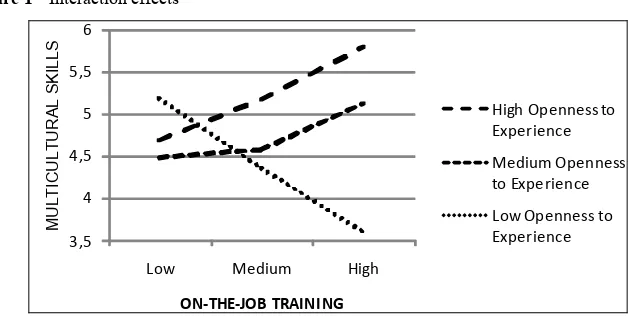

The results revealed a significant interaction between on-the-job training and openness to experience on MCS (see step 3 in Table 2), which accounted for 4% of the incremental variance in MCS beyond the main effects, lending support for our hypothesis.

Table 2 Results of hierarchical regression analysis for dependent variable MCSa

Variable Step 1 Step 2 Step 3

On-the-job training .22*b .25* .23*

Openness to experience .24* .27*

On-the job training × openness to experience .20*

Total R2 .05* .11* .15*

ΔR2 block .06* .04*

Notes: an = 239; bstandardised β coefficients are shown. *p < .001.

To understand this interaction, we plotted the effect of the three levels of on-the-job training for each of the three levels of openness to experience. The three levels for on-the-job training and for openness to experience were created by splitting the respective scores in three groups (low – the scores more than one standard deviation below the mean; medium – the scores within +/– one standard deviation from the mean; high – the scores more than one standard deviation above the mean). The interaction of on-the-job training and openness to experience is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Interaction effects

3,5

4 Discussion

To understand this study’s findings, one must consider the traits associated with openness to experience, namely, being imaginative, cultured, curious, original, broad-minded, and intelligent (Barrick and Mount, 1991); questioning their own cultural assumptions, being willing to experience and enjoy new and unfamiliar environments, seeking out, and acting on new experiences, and extending their repertoire of behaviours beyond the daily habits (Ang et al., 2006). It might as well be that when the levels of initial training, informal training, mentoring, coaching, and the availability of resources are low, individuals high in openness to experience get bored and do not put their abilities to the best use. On the other hand, those low in openness to experience might be much more comfortable under such circumstances, which is why they outperform their high-openness-to-experience counterparts in terms of their MCS. As the levels of initial training, informal training, mentoring, coaching, and the availability of resources start to increase, the situation gets reversed. Individuals high in openness to experience become more comfortable with the situation and their willingness to engage in learning experiences results in theirs benefiting more from training programmes, as found by Barrick and Mount (1991). Those low in openness to experience, on the other hand, might not respond well to the increased levels of on-the-job training, might be less able to deal with the newly created complexities, and might resent the burden placed upon their cognitive, conative, and behavioural resources. This explanation is in line with the reasoning of Hong et al. (2007; cited in Leung et al., 2008) that when close-minded individuals are exposed to unfamiliar cultures, they may find novel ideas and practices in these ‘foreign’ cultures overwhelming and threatening and therefore may resist these ideas and retreat to the intellectual comfort zone in their own culture.

The present study adds to the openness to experience and MCS literature by showing that openness to experience interacts with on-the-job training in their relation to MCS. Although it has been shown that MCS (under various names) are related both to openness to experience (e.g., Ang et al., 2006; Pagon et al., 2009) and to on-the-job training (e.g., Grigorian, 2008; Pagon et al., 2009), and that openness to experience was found to be a valid predictor of training proficiency (Barrick and Mount, 1991; Salgado, 1997) no research to date – to the best of our knowledge – has examined the interaction of these two variables.

Our results, therefore, add to the body of knowledge about the importance of openness to experience as a moderator of many relationships among various variables that have relevance for organisational life, such as multicultural experience – creativity, computer-assisted communication – decision-making, creative time pressure – creativity, and now on-the-job training – MCS relationship.

In terms of practical implications, our findings suggest that selecting public sector managers who score high on openness to experience might help increasing the effectiveness of on-the-job training programmes as well as the level of MCS in public administration. If, for whatever reason, openness data are not available, research shows that observer ratings of some big five characteristics are just as valid as self-ratings, so supervisors may be able to judge openness more informally (Mount et al., 1994; cited in Colquitt et al., 2002). At the same time, we cannot expect an individual’s openness to experience to change much over the years. Temporal stability for individual differences in traits increases over the life course, reaching impressively high levels in the middle-adult years (McAdams and Olson, 2010). Roberts et al. (2006; cited in McAdams and Olson, 2010) conducted a meta analysis of 92 longitudinal studies, analysing mean scores on traits by age decades, from age 10 to age 70. Openness to experience showed a curvilinear trend: an increase up to age 20 and then a decrease after age 50.

This study should be evaluated in light of its limitations. The major ones are a small sample size and exclusive reliance on self-report measures; no data from the managers’ subordinates, superiors, or clients were collected. In testing the predictive validity of individuals’ self-reported multicultural competence, Cartwright et al. (2008) found significant differences between self-report scores and independent observer ratings, with self-report scores being higher for all respondents.

Future studies should address these limitations. Also, this study’s findings obtained on a sample of public administration managers should be tested in other sectors/industries. It is our hope that this study will instigate more research into the role that openness to experience is playing in organisational settings, especially when it comes to MCS and competency.

References

Aiken, L.S. and West, S.G. (1991) Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions, Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA.

Ang, S., Van Dyne, L. and Koh, C. (2006) ‘Personality correlates of the four-factor model of cultural intelligence’, Group & Organization Management, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp.100–123. Baer, M. and Oldham, G.R. (2006) ‘The curvilinear relation between experienced creative time

pressure and creativity: moderating effects of openness to experience and support for creativity’, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 91, No. 4, pp.963–970.

Barrick, M.R. and Mount, M.K. (1991) ‘The big five personality dimensions and job performance: a meta-analysis’, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp.1–26.

Cartwright, B.Y., Daniels, J. and Zhang, S. (2008) ‘Assessing multicultural competence: perceived versus demonstrated performance’, Journal of Counseling & Development, Vol. 86, No. 3, pp.318–322.

Costa, P.T. and McCrae, R.R. (1992) Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual, Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa, FL.

Donnellan, M.B., Oswald, F.L., Baird, B.M. and Lucas, R.E. (2006) ‘The mini-IPIP scales: tiny-yet-effective measures of the big five factors of personality’, Psychological Assessment, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp.192–203.

Fink, G. and Mayrhofer, W. (2009) ‘Cross-cultural competence and management – setting the stage’, European Journal of Cross-Cultural Competence and Management, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp.42–65.

Getha-Taylor, H. (2008) ‘Identifying collaborative competencies’, Review of Public Personnel Administration, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp.103–119.

Grigorian, R.A. (2008) ‘Assessment of the current cultural awareness and training for the Air Force contingency contracting officer – thesis’, Air Force Institute of Technology, Graduate School of Engineering and Management.

Homan, A.C., Hollenbeck, J.R., Humphrey, S.E., Van Knippenberg, D., Ilgen, D.R. and Van Kleef, G.A. (2008) ‘Facing differences with an open mind: openness to experience, salience of intragroup differences, and performance of diverse work groups’, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 51, No. 6, pp.1204–1222.

Jaccard, J., Turrisi, R. and Wan, C.K. (1990) Interaction Effects in Multiple Regression, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

Le Pine, J.A., Colquitt, J.A. and Erez, A. (2000) ‘Adaptability to changing task contexts: effects of general cognitive ability, conscientiousness, and openness to experience’, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 53, No. 3, pp.563–593.

Leung, A.K., Maddux, W.W., Galinsky, A.D. and Chiu, C.Y. (2008) ‘Multicultural experience enhances creativity: the when and how’, American Psychologist, Vol. 63, No. 3, pp.169–181. McAdams, D.P. and Olson, B.D. (2010) ‘Personality development: continuity and change over the

life course’, Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 61, pp.517–542.

McCrae, R.R. (1994) ‘Openness to experience: expanding the boundaries of factor V’, European Journal of Personality, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp.251–272.

McCrae, R.R. and Costa, P.T. (1997) ‘Conceptions and correlates of openness to experience’, in Hogan, R., Johnson, J. and Briggs, S. (Eds.): Handbook of Personality Psychology, pp.825–847, Academic Press, San Diego.

Pagon, M., Banutai, E. and Bizjak, U. (2009) ‘Multicultural skills in the EU Public

Administration’, Proceedings of the 7th International Conference ‘Economic Integration, Competition and Cooperation’, Opatija, Croatia, available at

http://www.oliver.efri.hr/~euconf/2009/docs/session11/1%20Pagon%20Banutai%20Bizjak.pd f.

Ramsey, V.J. and Kantambu Latting, J. (2005) ‘A typology of intergroup competencies’, Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, Vol. 41, No. 3, pp.265–284.

Salgado, J.F. (1997) ‘The five factor model of personality and job performance in the European community’, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 82, No. 1, pp.30–43.

Notes