By

Elżbieta

M.

Goździak

, Ph.D.

Research Professor

Institute for the Study of International Migration

Georgetown University

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding for this research was provided by the Interdisciplinary Behavioral and Social Science Research-Exploratory (IBSS-Ex) program of the National Science Foundation (Award #1416769). Warm thanks to our NSF Project Officer, Dr. Brian D. Humes for his assistance throughout the life of the grant.

This report benefited greatly from the contributions of many individuals.

In the course of this and previous research projects on human trafficking in Nepal, I interviewed numerous representatives of the Nepali government, staff members of international and local non-governmental organizations, representatives of the International Labor Organization (ILO) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). They all shared their knowledge and insights and I am grateful for their generosity of time and wisdom.

My graduate research assistants, Charles Jamieson and Nicole Johnson, provided indispensable assistance in conducting literature reviews, analyzing existing anti-trafficking laws and data, and masterfully copy-editing and formatting this report.

Elżbieta M. Goździak is Research Professor at the

Institute for the Study of International Migration (ISIM) at Georgetown University. Formerly, she served as Editor of International Migration and held a senior position with the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). She taught at the Howard University in the Social Work with Displaced Populations Program, and managed a program area on admissions and resettlement of refugees in industrialized countries for the Refugee Policy Group. Prior to immigrating to the United States, she was an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the

INTRODUCTION

Trafficking of people for forced labor and sexual exploitation is believed to be one of the fastest growing areas of international criminal activity and one that is of increasing concern to the international community. Trafficking is commonly understood in terms of the activity, the means, and the purpose, where: (1) The activity refers to some kind of movement either within or across borders; (2) The means relates to some form of coercion or deception, and (3) the purpose is the ultimate exploitation of a person for profit or benefit of another (Martin & Callaway, 2011: 225).

While understanding and recognition of trafficking in persons has improved in recent years, there is little systematic and in-depth analysis of the full life cycle of cross-border human trafficking—from pre-trafficking and recruitment through exploitation to return home or integration into a new community. An area in which very little is known are the experiences of trafficking survivors after return to their home countries. Who returns to their home countries? What is the process for return? After return, are survivors still subject to the same situations that caused them to be trafficked in the first place? What are their health and mental health, education, employment, and other needs after return? Do they receive services that will enable them to reintegrate and, if so, for what period and with what efficacy? What types of stigmas persist over time, particularly for those who were sexually exploited and abused? What are the risk factors for being re-trafficked? To what extent is information available about the incidence and prevalence of re-trafficking? This information is of particular import given the fact that many countries provide survivors with respite assistance, but lack long-term immigration relief.

in 2010 and 2013. Data from those earlier projects—including extensive interviews with representatives of the Ministries of Labor and Transport; Women and Social Affairs; and Education; ethnographic interviews with representatives of district governments; interviews with several international NGOs providing anti-trafficking and educational services to children and adolescents; and discussions with other funders (e.g.; DOL, USAID, UNICEF)—have been incorporated into this analysis.

COUNTRY PROFILE

Nepal covers approximately 147,000 square kilometers, stretching 800 kilometers from east to west and 90 to 230 kilometers from north to south. Nepal is land-locked between China (including the Tibet Autonomous Region) and India. Nepal has three geographic regions: the mountainous Himalayan belt (including 8 of the 10 highest mountain peaks in the world), the hill region, and the plains region. Nepal contains the greatest altitude variation on earth, from the lowland Terai, at almost sea level, to Mount Everest at 8,848 meters. Nepal is divided into five development regions and seventy-five districts.

Nepal has a population of about 28 million people. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the country is in the middle of its demographic transition. Despite an increase in the contraceptive prevalence rate (41percent), the population is growing at a rate of 2.25 percent, which is higher than other countries in the region. Young people aged 10 to 24 years comprise 32 percent of the total population, a record level that presents concomitant challenges (Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, 2006).

Nepal is one of the poorest countries in Asia and the 15th poorest in the world with GDP

agricultural sector in the GDP is only 40 percent. The main foreign currency earners are remittances, around US$2 billion annually, from migrant workers, carpet exports (mostly to Germany), garment exports (to the United States), and tourism. Nepal receives $50 million a year through the Gurkha soldiers who serve in the Indian and British armies and are highly esteemed for their skill and bravery (IASC 2008).

Country Nepal

Population 28 million Land Area 147,180 km2 GNI Per Capita $730

Life Expectancy 69 years Official Languages Nepali US State Department TIPR Ranking1 Tier 2

Source: World Bank Development Indicators, US State Department Trafficking in Persons Report 2015

Nepal’s workforce of about 10 million suffers from a severe shortage of skilled labor. The

spectacular landscape and diverse, exotic cultures of Nepal represent considerable potential for tourism, but growth in this hospitality industry has been stifled by recent political events. IExplore, a travel company, published rankings of the popularity of tourist destinations, based on their sales, which indicated that Nepal had gone from being the tenth most popular destination among adventure travelers, to the twenty-seventh. The 2015 earthquakes adversely affected tourism in Nepal as well. The rate of unemployment and underemployment approaches half of the working-age population. Thus, many Nepali citizens move to India in search of work. The Gulf countries and Malaysia are also big destinations for labor migration.

1The US State Department Trafficking in Persons report ranks countries as follows:

Tier 1: Countries whose governments fully comply with the Trafficking Victims Protection Act’s (TVPA) minimum standards.

Tier 2: Countries whose governments do not fully comply with the TVPA’s minimum standards, but are making significant efforts to bring themselves into compliance with those standards. Tier 3: Countries whose governments do not fully comply with the minimum standards and are

The country has undergone great political and social change. In November 2006, a deal was struck between the government and the Maoists ending ten years of civil war during which 13,000 people were killed and an estimated 100,000 to 150,000 were internally displaced. The 2008 elections gave the Maoists a majority in the Nepali government and, after a 240-year reign, the monarchy was abolished. However, the conflict disrupted rural development activities and lead to a complex economic and political situation.

Although a Comprehensive Peace Agreement, ending a decade-long conflict between the Maoists, the government and monarchy, and a popular pro-democracy uprising, was signed in 2006, the situation in Nepal remains fragile. The peace process continues to be monitored by the United Nations Mission in Nepal as disparate groups who were previously united for democracy or under the banner of the Maoist insurgency, began to fragment and regroup around ethnic identities, with the potential to reignite localized conflict. The challenge for the Nepali peace process is to address grievances in an

inclusive manner that doesn’t replicate the power structures of yester years.

2010 was supposed to be an important year in the Nepalese peace process, following the slow progress in implementing the peace agreement and the creation of a new constitution. However, many crucial issues such as demobilization and reintegration of ex-combatants, merging of the Maoist rebels into the National Army, and competing calls from some regions for autonomy took much longer than expected. For five years, until the election of K.P. Oli in November 2015, Nepal was ruled by a caretaker government.

higher demand for sex workers, including trafficked sex workers. Military groups may have utilized child soldiers and war wives as well as other trafficked persons to undertake a variety of tasks (Cameron and Newman 2008).

Indeed, news outlets reported that right after the earthquake, authorities rescued 160 Nepalese trafficked to northern India. Kamal Saksena, home secretary for Uttar Pradesh state in India, indicated that 50 to 60 arrests were made in his district. In one case, the authorities intercepted a couple in their mid forties who had 15 children. The children lied, saying their parents were taking them to Mumbai for sightseeing. According to the authorities, the children were sold to the traffickers for 1,500 rupees ($32) each.2 The

Himalayan Times also reported that human trafficking via the Birgunj border has increased after the earthquake through the turbulent times of the blockade3 at the Nepal-India

border. As will be shown later in this report, our research did not corroborate the notion of increased trafficking after the earthquake. Interviewees did talk about instances of attempted clandestine border-crossing in order to secure necessary goods, especially fuel and medication, but not about kidnappings or trafficking.

2See http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-02-15/nepal-earthquakes-cause-spike-in-human-trafficking/7168398

LABOR MIGRATION IN NEPAL

Nepal has a nearly 300-year long history of labor migration dating back to the period of unification and a resulting mass migration to the neighboring states to avoid taxation (UN DESA 2013). The induction of young Nepali men into the colonial British army in the early 19th century is considered the first instance of formalizing labor migration

through treaties between the Nepali and the British governments (Gurung 2004).

Much of the history of labor migration from Nepal is characterized by migration to the neighboring country of India. Nepal and India, which share a very long border of over 1,800 kilometers, have a Friendship Treaty that allows for free movement without inspection between the two countries. Migration to the Gulf and Tiger States, Europe, and the United States is a much more recent development. The demand for workers in the Middle East created massive opportunities. The Government of Nepal responded with the promulgation of the Foreign Employment Act of 1985.4

There is limited documentation of the movements of migrant workers and their remittances and national census data has been criticized as giving an underestimate of migration numbers (Seddon et al., 2001; Graner and Gurung, 2003). Assessing the real number of labor migrants is nearly impossible considering both the country’s open

border with India and migrants’ use of irregular channels to seek better opportunities in

other countries. Several interviewees indicated that many people, especially women, depart for foreign countries via India. In the early 2000s, official data on international migration from Nepal revealed that the number of Nepalese living in foreign countries exceeded one million (Kollmair et al 2006). A more recent ILO report indicates that, in 2011, almost two million (1,921,494) or 7.3 percent of Nepali citizens lived abroad (CBS 2012). The Nepali Population Clock suggests that 77,000 Nepalese emigrated in 2015 alone.5

In Kathmandu as well as in several villages in the Terai6, the research team heard

numerous accounts of people seeking work abroad. Policy-makers and representatives of international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) repeatedly indicated,

“hundreds of people leave Nepal every day.” Numerous Nepalese we interviewed expressed similar sentiments. In the course of a discussion with a group of 16 women in a village in the Terai, one woman narrated her migration history to India with her grandparents and her subsequent return to Nepal. Another one talked about her two younger sisters who migrated: one to Iraq and one to Kuwait. A third woman had a husband in Qatar. He had been working there for four years. In two different settlements established for Kamaiyas freed from bonded labor, most males were working in India and were coming home only once a year. Several respondents sought our advice on migrating to the Gulf countries.

Freed Kamaiya women Photo by Elzbieta M. Gozdziak

Nepali people lining up to apply for a passport Photo by C. Timothy McKeown

International migration of children and young people is of particular import to funders such as the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) that support initiatives aimed at preventing child labor and child trafficking in Nepal. World Education, one of the grantees of DOL, suggested that about 40 percent of children participating in the Brighter Futures Program7 dropped out of the program because they decided to migrate (Gozdziak 2011).

The majority (70 percent) of those who migrate are boys and the remaining 30 percent girls. Many children migrate (or are brought) from rural areas into the city on the promise that they will get education, better life, and better pay. According to anti-trafficking activists and child advocates many of these children inadvertently become victims of trafficking—both internal and cross-border—for domestic servitude or sexual exploitation.

Migration of young people who complete schooling is also widely debated. On October 1, 2010, Tsering Dolker Gurung published an op-ed piece in the Kathmandu Post and observed:

Out of the 32 students who passed SLC [School Leaving Certificate] with me from my school, only 12 remain in Nepal. The rest have gone to what students now call their dream destinations—the US, the UK, Canada and other Western countries. Even the ones who are here are in the process of leaving. (Gurung 2010)

Indeed, the number of students going overseas each year is alarming. A significant decrease in the number of youth in the country has been noticed. In a study conducted in Galkot in the Midwestern part of Baglung district, often referred to as place of lahure or foreign migrant, Gautam (2008) studied the effects of migration of young people on the elderly. The research indicated that over 50 percent of the population migrated. The largest number (38.96 percent) moved to Indian cities, followed by Saudi/Qatar/UAE (19.5 percent), followed by Japan/Singapore, and other developed Asian countries (13.75 percent).

Young people are also migrating from rural areas to the Kathmandu Valley. Although Nepal is one of the least urbanized countries in the world, rural to urban migration is not a new phenomenon. Nepali people have been leaving their villages in droves in the past 50 years, seeking better opportunities in Kathmandu and other urban centers. In 2014, the level of urbanization was 18.2 percent, with an urban population of 5,130,000, and a rate of urbanization of three percent (UN DESA, 2014). For the period 2014-2050, Nepal will remain amongst the top ten fastest urbanizing countries in the world with a projected annual urbanization rate of 1.9percent (UN DESA, 2014).

The effects of the ensuing demographic change are easily visible within the capital, where the population of Kathmandu Metropolitan City was 1,003,285 in 2011 (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2012: 3). UN DESA (2014: 367) updated this to 1,142,000 in 2014, and projected a population of 1,183,000 in 2015, rising to 1,855,000 by 2030. New housing projects continue to pop up among lands that were once paddy fields and traffic congestion seems to be increasing every day. In 1972, there were 16 urban centers in Nepal, compared to 58 at the turn of the millennium.

Porter girl in Dunbar Square Photo by Sanjula Weerasinghe

HUMAN TRAFFICKING IN NEPAL

THE LEGAL FRAMEWORKS

Nepal is not a party to the 2000 UN Trafficking in Persons Protocol. In the Nepali context, human trafficking is most commonly described as hili beti wosar pasar (buying and selling of girls and daughters) and yaabasayik taun soshan (commercial sexual exploitation). Both are terms that only partially capture the international definition of trafficking in persons enshrined in the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (also known as the Palermo Protocol) which defines human trafficking as:

The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. (Palermo Protocol 2000)

Trafficking of adults always requires force, deception and coercion, but when a third party moves or uses children in prostitution, pornography or removal of organs, force or coercion do not need to be present to deem these acts child trafficking (Dottridge and Jordan 2012). According to the Palermo Protocol, the use of threat, force or other forms of coercion, abduction, fraud, deception or abuse of power are not required when it comes to children and adolescents because in the eyes of the law children under the age of 18 do not have the same legal capacity as adults to engage in certain forms of work. “If children have been recruited and transported for the purpose of exploitation, they have been

‘trafficked’ no matter if they consented to move” (O’Connell Davidson 2011: 457).

removal of human organs. Prescribed penalties range from 10 to 20 years of imprisonment, which are sufficiently stringent and commensurate with those prescribed for other serious crimes, such as rape. Forced child labor and transnational labor trafficking offenses may be prosecuted under the Child Labor Act and the Foreign Employment Act.

The ambivalence of the Nepali government when it comes to criminalizing all forms of trafficking for labor exploitation and its limited ability to enforce the existing laws against human trafficking might be related to the fact that for centuries, millions of people in Nepal have been affected by generational bonded labor and other forms of servitude under such systems as Kamaiya, Haliya, Bhude, Kamalari, Haruwa-Charuwa, Baalighare (Khalo), Dom, Pode, Badi, and Deuki (See Box 1 for explanations of these various servitude systems). Debt bondage continues to be present in traditional agriculture and domestic work, but is also present in garment and brick industries. The practice is particularly prevalent in the Far Western Region (including Kanchanpur), which has the highest concentration of big land holdings.

Box 1: Servitude systems

Kamaiya Form of descent slavery: generation after generation, Kamaiyas were enslaved, bought and sold, and forced to work for their creditors in deplorable conditions. Because they received a minimum or no wage, they were virtually unable to repay their debts, which were inevitably passed onto their children and grandchildren.

Haliya Less severe form of agricultural debt bondage. The Haliyas could not be sold, they were allowed to leave the property of the creditor, and they usually received in-kind payments. They could also pursue other forms of employment in their free time. However, they had to make themselves available to work for the creditor upon request until their debt and incurred interest were fully repaid.

Haruwa-Charuwa

Traditional agricultural practice similar to slavery. Haruwas are men and boys whose main job is to plough. The term Charuwa refers to boys and girls who work as herders. The Haruwas and Charuwas serve for, and are highly dependent on, rich landlords across the eastern, central and western Terai districts.

Baalighare (Khalo)

This practice is found within the Dalit communities in the mid-western and far-western Nepal. It is an exploitative form of exchanging goods and services for other goods and services: the semi-skilled laborers offer door-to-door services and demonstrate loyalty to their patrons (Bista) for an entire year in order to accumulate seasonal crops as wages for their work. The Baalighare must meet their Bista’s demands and are unable to negotiate wages.

Doms Landless and compulsorily relegated to occupations that are viewed as inferior and polluting, the Doms are considered untouchable. They usually live and operate within a marked territory throughout the Terai belt, including Morang. Although they are involved in income-generating work, such as pig farming, basket waiving, cremation, and carcass disposal, their wages are minimal. If Doms refuse to perform their traditional duties, they often face mistreatment by the villagers and/or expulsion from the community. The Pode community in Kathmandu Valley resembles the Doms in the Terai. Podes clean garbage, drainage, and dirt in the city and are also considered untouchable.

Badi Adults and children who belong to the Badi community are also highly susceptible to exploitation. Badi people reside in the western part of Nepal, including Kanchanpur. They were traditionally known as entertainment providers. However, in the lack of opportunities, they became involved in prostitution, which led to social stigmatization, discrimination, and exclusion. Many Badi children are born out of wedlock, which limits their access to citizenship and reinforces their vulnerability to discrimination, trafficking, and abuse.

Deukis The Far-Western region, including Kanchanpur, is also home to about 2000 Deukis. Traditionally, Deukis were prepubescent girls who were given to the temples by their families as offerings to the gods. They were uncared for and forced into prostitution. Men believed that sexual intercourse with a Deuki would cleanse them of their sins and cure them of their illnesses. Although the practice was abolished several decades ago, the children of Deuki carry the stigma of their mothers and experience problems and abuses similar to that of the Badi.

Source: Adapted from the HUMAN TRAFFICKING ASSESSMENT TOOL REPORT FOR NEPAL by the American Bar Association8

8 The full report can be accessed here

Although the traditional Kamaiya and Haliya systems have been formally eradicated9,

the western part of Nepal continues to be affected by bonded labor, particularly in the agricultural sector. The laborers are free to leave, cannot be bought and sold, and, in comparison with the past, have more bargaining power over salary and work conditions. Nevertheless, their persistent poverty and lack of opportunities leave them and their children prone to exploitation.

According to the 2015 U.S. State Department’s Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report, Nepal is a source, transit, and destination country for men, women, and children who are subjected to forced labor and sex trafficking. Nepali men are subjected to forced labor in the Middle East. Nepali women and girls are subjected to sex trafficking in Nepal, India, the Middle East, and China and subjected to forced labor in India and China as domestic servants, beggars, factory workers, mine workers, and in the adult entertainment industry. They are subjected to sex trafficking and forced labor elsewhere in Asia, including in Malaysia, Hong Kong, and South Korea. Nepali boys are also exploited in domestic servitude and, along with a number of Indian boys transported to Nepal, subjected to forced labor within the country, especially in brick kilns and the embroidered textiles, or zari, industry. Extreme cases of forced labor in the zari industry frequently involve severe physical abuse of children. Bonded labor exists in agriculture, cattle rearing, brick kilns, the stone-breaking industry, and domestic servitude. Children of Kamaiya families that were formerly or are currently in bonded labor are also subjected to the kamalari system of domestic servitude. Human traffickers typically target low-caste groups.

Some of the Nepali migrants who willingly seek work in domestic service, construction, or other low-skilled sectors in India, Gulf countries, Malaysia, Israel, South Korea, and Lebanon subsequently face conditions indicative of forced labor such as withholding of passports, restrictions on movement, nonpayment of wages, threats, deprivation of food and sleep, and physical or sexual abuse. In many cases, unscrupulous Nepal-based labor brokers and manpower agencies facilitate this forced labor. Unregistered migrants— including the large number of Nepalese who travel via India or rely on independent recruiting agents—are more vulnerable to forced labor. Migrants from Bangladesh, Burma, and possibly other countries may transit through Nepal for employment in the Gulf States, fraudulently using Nepali travel documents, and may be subjected to human trafficking.

THE SCALE OF HUMAN TRAFFICKING IN NEPAL

The Nepalese authorities do not track the number of victims identified, and observers reported to the U.S. State Department that government efforts to identify victims remained inadequate in 2015. The scale of human trafficking in Nepal cannot be substantiated by rigorous research either. The estimates vary widely. In 2003 Terre des Hommes put the number of women and girls trafficked from Nepal to India at 5,000 to 8,000 each year (Terre des Hommes 2003). Others estimate that over 140,000 to 200,000 young girls and women are trafficked into the sex market of Indian brothels in Calcutta, Siliguri, Kanpuir, Gorakhpur, Lucknow, New Delhi, and Bombay (Sangroula 2001).

Maiti Nepal, a large anti-trafficking and rehabilitation NGO based in Kathmandu which has won worldwide praise for its efforts,10 claims that they alone have rescued some

30,000 girls and young women at the Nepal-India and Nepal-China borders from potential risks of trafficking.11 Research on child trafficking is limited and focuses mainly

on cross-border trafficking for sexual exploitation. ILO-IPEC reported in 2001 that 12,000 girls were trafficked annually to India and identified 86 districts that were affected. Many NGOs currently feel that the entire nation is affected by trafficking. These figures are for cross-border trafficking for sexual exploitation only and there is neither data on internal trafficking nor on trafficking for other forms of exploitation (ILO-IPEC 2001).

According to TDH, a recent survey showed that there are 1.3 million children who are being sexually exploited in India. The majority or 85 percent are Indian. The rest are Bangladeshi and Nepali. The majority of Nepali child victims come from indigenous groups (Janajati). Reportedly, approximately 11,000 to 13,000 Nepali persons are trafficked each year; roughly 33 percent are children. However, there has never been any empirical research conducted on this issue so this estimate should be taken with a grain of salt (Terre des Homme 2003).

Some interviewees estimated that 20-25 percent of sex workers in Nepal are under the age of 16 years. Indeed, we have seen very young girls, including an eight-year-old, working in the kitchen of a “cabin restaurant” and being groomed to work as a sex worker

10Anuradha Koirala, the founder and director of Maiti Nepal, received the CNN Hero of the Year award in 2010. See

http://www.cnn.com/SPECIALS/cnn.heroes/archive10/anuradha.koirala.html

there. We have also met with several young women working in “massage parlors” who

come to a drop-in center for a bit of respite and literacy training. Two of the young women we spoke with—they claimed to be 18 years of age, but the program staff told us later that they were only 15 and 1612, respectively—were about to migrate to China for sex

work. The program staff tried to persuade them to stay in Kathmandu, but they thought they would be better off (economically) in China. They did not speak a word of Chinese or any other language but Nepali and told us that they did not know anyone in China except the man who was arranging their travel.

The American Himalayan Foundation (AHF) indicates that 20,000 Nepali children are trafficked annually. The foundation cites Acharya (1998) to support their claims.

However, Acharaya’s report includes in these estimates both trafficked children and

children in hazardous forms of labor. While both constitute child abuse and child exploitation, not all forms of child labor should be equated with child trafficking. Bal Kumar and colleagues describe the conflicting numbers as follows in a report commissioned by ILO-IPEC (2001):

The range of information and the variation in estimates of girls trafficked for sexual exploitation in Nepal and India is so vast that it is impossible to determine the real magnitude of the problem based on the existing literature alone (Seddon 1996; Upreti 1996). The figure ranges from 5,000 to 7,000 to 20,000 Nepalese children being

trafficked every year (…). Furthermore, Indian and Nepalese sources also differ considerably and (…) it is safe to say that all estimates made are speculations that have

not been verified by rigorous research methods. (p. 6)

National estimates are unreliable and administrative data is scarce as well. In 2010, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Kathmandu indicated that they assisted some 400 survivors of trafficking, mostly women. While most of them were adults at the time of rescue, they were trafficked when they were minors. IOM was not able to provide any administrative data for later periods of time, including the time period covered by this research. According to IOM, most children are trafficked to India. Boys are trafficked mainly for the circus industry and girls both for the circus industry and for sexual exploitation. Minors who are trafficked to India rarely are trafficked to a third country. It is generally adult women in possession of passports that can be trafficked to other countries beyond India. The open border makes trafficking very easy as there is no need to show an identity card. Adults are also trafficked to the Middle East; women mainly for sex and domestic work, and men primarily for other forms of labor. Women

and children are also trafficked within Nepal; women mainly for domestic work, and children to work in factories and in domestic work (Meena Paudel, personal communication).

PREVENTION, PROTECTION AND ASSISTANCE

TO TRAFFICKED VICTIMS

In most countries anti-trafficking initiatives are organized around the 4 Ps: prevention, protection, prosecution, and partnerships. The efforts of the Nepali government as well as most of the initiatives supported by foreign donors focus mainly on prevention, especially prevention of child labor that is believed to put children at an increased risk for cross-border and internal trafficking. While awareness raising campaigns also target women, the main strategy of the Nepali government to prevent trafficking of women was to ban migration of females under the age 30 to the Gulf states for domestic work. In May 2014, the government suspended all exit permits for domestic work. Officials acknowledged the ban had increased illegal migration and subsequently heightened

migrants’ risks to exploitation; however, the government viewed these policies as

temporarily necessary to protect female migrant workers while formulating safe migration guidelines. Men seem to be completely absent in these governmental initiatives.

In the following section we discuss programs that focus on prevention of trafficking of women and children, but especially minors, and present a range of promising practices and strategies.

FOCUS ON PREVENTION OF HUMAN TRAFFICKING

Prevention efforts are being launched in Nepal at the expense of protection of and assistance to returned victims. The overwhelming focus on prevention of human trafficking is dictated, on the one hand, by the alarmist assumptions that trafficking is rampant in Nepal and therefore no effort should be spared to prevent it. On the other

According to the 2015 TIP report, the Nepali government has undertaken several efforts to prevent human trafficking. The inter-ministerial National Committee for Controlling Human Trafficking (NCCHT) met regularly and issued its second report on the

government’s anti-trafficking efforts. The government also issued the National Plan of Action implementation plans and conducted two coordination sessions with local officials from at least 27 districts to clarify their roles and responsibilities and set budget and timeline goals to ensure completion of the tasks. The NCCHT allocated 233,000-380,000 Nepali rupees (NPR), approximately $2,300-$3,750, to each of the 75 district committees to support awareness campaigns, meeting expenses, and emergency victim services; this was an increase over the 42,000-57,000 NPR ($414-$562) allocated in fiscal year 2013. This allocation specifically included 120,000 NPR ($1,180) for each district to establish at least three new village level committees. All Nepali peacekeeping forces were provided pre-deployment trafficking training. The government provided anti-trafficking training or guidance for its diplomatic personnel. However, the government did not make efforts to reduce the demand for commercial sex acts or forced labor.

In addition to the Nepali government, many other organizations, including the International Labor Organization (ILO), International Organization for Migration (IOM), international non-governmental organizations, and local civil society groups are involved in anti-trafficking efforts. Between 2009 and 2011, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) supported the Ministry of Labor and Employment (MoLE) with capacity building for government officials, services to labor migrants, development of country specific fliers and flip charts on safe migration channels, including the establishment of a Migrant Resource Center in Kathmandu, which provides information on overseas migration and destination countries to potential labor migrants.

IOM’s newest initiative in Nepal—the Trafficking Survivors and Vulnerable Children Support Program--funded by ChildFund Korea and implemented in partnership with local NGOs in December 2015, focuses on vulnerable children and women to prevent them from falling prey to various forms of exploitation, including unsafe migration and trafficking. The majority of the activities center on anti-trafficking and safe migration campaigns at the national level; however, the project is designed to also provide support to the shelters for vulnerable children and survivors of trafficking. At the time of our last site visit in December 2015, the program was just being launched and there was little to observe in terms of services provided at the shelters.

labor issues in Nepal: 1) International Labor Organization’s International Program on the

Elimination of Child Labor (ILO/IPEC); and 2) Child Labor Education Initiative projects.

The ILO-IPEC project aimed to rehabilitate bonded adult and child laborers and to prevent them from re-entering exploitative forms of labor. The intervention strategy consisted of:

Direct action targeted at ex-Kamaiyas, their families and children in order to secure their effective release from bondage and to sustainably reduce their poverty through training and education and livelihood improvement;

Capacity and alliance building among key actors--the Government, workers' and employers' organizations, and civil society--for policy development and program formulation at the national and district levels; and

Awareness raising campaigns among ex-Kamaiyas, their landlords and society at large. Another important component of the project is to ensure sustainability through data collection, research, and the implementation of a tracking system.

The direct beneficiaries of the project were ex-Kamaiyas and children under the Kamaiya system and those still de facto in debt bondage or at risk of falling into bondage in the eight districts of western Nepal — Banke, Bardia, Dang, Kailali, Kanchanpur, Nawalparasi, Rupandehi, and Kapilvastu. Since women and girls are at high risk of bondage due to the prevailing gender discrimination in these communities, priority target groups were Kamaiya women and girls under the age of 18. The project also worked in close collaboration with the ILO sub-regional Project on Preventing and Eliminating Bonded Labor in South Asia (PEBLISA) in Nepal, which focused on prevention of bonded labor through various strategies, including micro finance.

The Child Labor Education Initiative was implemented by two international NGOs: Winrock International and World Education. Below we present some of the promising practices identified and implemented by these INGOs.

PROMISING PRACTICES

actively used to enhance existing initiatives, posited interviewees. Interviewees called for giving voice to small NGOs working in the provinces and remote areas. At the moment,

What this means is that NGOs that are smooth, well known, have status and who can write end up dominating the discussion on child labor. So Maiti Nepal and CWIN are the voices that are heard and not the NGOs on the ground, which do the frontline work. What is needed is more documentation of best approaches, promising practices, and good pilots, which can inform future work. The best way to do this is to be disciplined and build these into the projects.

Respondents also called for sharing best practices from within the region. They said that Nepal could probably learn from experiences of other projects in India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh where there are populations of child laborers and trafficked children.

Despite the general feeling that there has not been much reporting on promising practices, two programs identified working strategies and approaches to combating child labor and child trafficking in Nepal. In April 2008, Winrock International published a 200-page handbook of best practices in eliminating child labor through education. This extensive manual is based on over five years of experience in implementing the Community-based Innovations for the Reduction of Child Labor through Education (CIRCLE) Project. The Best Practices in Preventing and Eliminating Child Labor manual documents the experiences of over 80 NGOs and demonstrates the possibilities for change and sustainability in difficult environments. It addresses questions of how to work with child labor monitoring committees, develop savings programs, and inspire volunteer work. It offers insights on the best means of reaching rural families, treating marginalized groups,

and strengthening women’s and children’s participation in decision-making.

In the words of the project final evaluation report “… the most exciting aspect of CIRCLE

is the model itself and its potential for revolutionizing the relationships between communities, implementing organizations, and funding partners by facilitating a more

participatory approach to project design and implementation.”13

Below we include a couple of vignettes taken from the manual to illustrate innovative and promising practices implemented in Nepal, with funding provided by OCFT projects. The research team met with some of the NGOs, which implemented these approaches and found that they continue to be major innovators in the anti-child labor field.

Aasaman: Street Drama to Raise Community Awareness of Child Labor

One of the principal objectives of the Aasaman project in Nepal was to raise awareness among disadvantaged communities about the importance of education for all children and about withdrawing children from work and enrolling them in school. Aasaman used a number of different methods, including public rallies, sensitization and training workshops, a birth registration campaign, homevisits, and street theater. It found that street theater was particularly effective in attracting the interest of the whole community and, through interaction with the audience, ofinvolving them in finding solutions to social challenges.

Theater is a popular and powerful visual medium for conveying social development challenges. It educates, informs, and entertains an audience and can hold up a mirror for people to see things that they may not normally notice in day-to-day life or that may be hidden from view, such as the exploitation of children. In the communities in which Aasaman worked, partnerships were formed with local NGOs to put together interactive street theater performances conveying messages about the dangers of child labor and the benefits of education. The actors, including children from the targeted communities, performed short plays depicting everyday situations involving children and work, including some of the worst forms of child labor such as child domestic labor. The plays presented scenarios in which, the actors would turn to the audience and ask their opinion, for example, whether an employer of a child domestic laborer should allow the child to go to school and benefit from the same opportunities as her or his own children.

The technique draws the audience into the performance and leads to a lively debate between the actors and the audience and among members of the audience. It also provides invaluable insight into the level of community awareness. Aasaman was able to build on this growing awareness through home visits, meetings with different stakeholders, children’s clubs, and women’s forums.

CWIN: Children as Advocates

The CWIN project in Nepal organized a National Forum of Working Children, bringing together children from different occupations. The forum drew up a set of written recommendations, which were presented to the Minister of Labor, who gave his assurances that the government would implement existing child labor legislation and policy.

existing government policies on child labor and education and drafted an improved policy document on the education of working and at-risk children.

CWIN also sought the involvement of local government institutions, including the District Women’s Development Office, the Department of Women’s Development, and the District Child Welfare Board in the project location. In addition, it put together a package of advocacy materials including a booklet on “Myths and Realities of Child Labor,” which was distributed among various stakeholders, including government institutions.

CWIN: Child-to-Child Advocacy Training in Nepal

The CWIN project in Nepal conducted a specific child-to-child advocacy training program for 239 children. Most of the participants were already involved in special children’s groups, called Child Rights Forums, set up within the framework of the project. The training program was designed to convey communication and interpersonal skills to support the child advocates in persuading their peers to leave situations of work and return to school.

The approach adopted by the child advocates included street theater techniques, whereby they developed pieces of drama based on the realities of working children and the benefits of education. These were performed in most of the project sites and schools, reaching thousands of children and adults, raising awareness and delivering messages to at-risk children and those both working and going to school. The drama was particularly appreciated by other children and was found to be an effective method of reaching disadvantaged children.

Use of Media

In addition to these promising practices, the research team found the following approaches very impressive and worthy of dissemination and wider discussion:

Mainstreaming madrassas into the national education system. Numerous respondents stressed the fact that the Muslim minority has been neglected in Nepal. There are approximately one million Muslims, of which roughly one-fifth includes children. The Muslim leaders requested the assistance of World Education to mainstream their schools into the national education system and to upgrade the quality of education in madrassas. World Education supported Muslim schools to form management committees and parent/teacher associations. The schools then developed Madrassa School Improvement Plans and started income generation activities to support their efforts. With funds raised these committees and associations embarked on a lofty goal to improve the quality of education in the madrassas, including upgrading physical facilities, introducing the national curriculum, and adding advanced grade levels. The government also provided financial resources to these schools. About 70 madrassas have been mainstreamed to date. The research team visited a girls’ madrassa in Western Nepal and was quite impressed with the community leadership rallying around the female principal and embracing the goal of educating Muslim females.

Girls’ madrassa in Western Nepal

Photo by Elzbieta M. Gozdziak

pay teachers’ salaries, but it does have the capacity to support infrastructure and educational materials. According to the Madrassa Improvement Plan, tripartite agreements have been made between the Nepali government, madrassas, and UNESCO. In a district where illiteracy levels among Muslim women reached 90-100 percent, these efforts cannot be underestimated.

Combating child labor in the entertainment industry. Saathi is an example of a small Nepali NGO that has managed to make great strides in combating child labor and protecting young female workers in the entertainment industry. Roughly 15-20 young women and girls drop-in every day to take advantage of literacy classes, life skills training, vocational training (sewing and embroidery), counseling, and other services. Recently, Saathi started collaborating with World Education around enrollment of young girls in formal education. The organization works with girls as young as 11, but most of their clients are females between the ages of 15-30. Their non-judgmental approach to both the young sex workers and the owners of cabin restaurants, massage parlors, dance restaurants, and open restaurants where alcohol drinking and prostitution are promoted enables Saathi to freely go into the entertainment industry establishments and train women on labor rights, counsel them on sexually transmitted diseases and reproductive health issues. Saathi has also attempted to organize these women into a labor union and turn over to them the management of the program. Unfortunately, because of the fluidity of the group it became apparent that it was not possible to give them full ownership of the program. However, Saathi managed to accomplish something that few Nepali organizations even attempted, namely they were able to raise about five percent of their budget from private donations!

Self-help women’s groups. In several localities the evaluation team visited with members of self-help groups. The name is somewhat of a misnomer, because these groups are really grass-roots savings and loans groups reminiscent of the early Grameen Bank in Bangladesh. These groups are not only examples of promising practices, but also have the potential to be sustainable for years to come as they do not have any overhead expenses and are formed on the basis of already existing linkages and personal friendships.

Female grass-roots leadership. The Tharu Women’s Upliftment Center is an excellent example of a grass-roots leadership program. About 17 years ago a few women in bonded labor worked for the same master. Working together in the same place provided them with a platform to discuss their problems, including domestic violence and other forms

of abuse. One of the women decided to seek advice from the master’s wife about

development and income generation for women and liked their idea. The group decided to concentrate not only on family matters but to also tackle such issues as income generation. These women began by saving money. They also raised money through membership fees. The money is put in a bank and it earns interest at around 5-7 percent. They spend the money on a variety of initiatives, including loans for income generation activities such as opening a shop, farm commercializing activities (vegetable growing and selling at markets), and sheep and goat rising. Sometimes the money is spent on philanthropic activities. For example, the group purchased rice and gave it to people who were affected by floods. Money is also spent on scholarships. The group provides about 5 scholarships per year to children from families who were desperately poor so that they can go to school and get the necessary materials. The amount for each scholarship and the number is based on the interest that is earned. The ladies manage to save money from the bangle money they received from parents and relatives during different festivals. They hold various fund-raising activities. Recently, they held a song competition and raised 23,000 rupees.

The research team met with 14 members of the center; they ranged in age from 18 to 50+. Most of the women were members and volunteers, but the group included also a couple of salaried staff members. Among them was a woman whose job is to motivate parents to send their daughters to school and to encourage parents to get involved in income generation activities. When asked what a husband should be like the response was that he should understand the feelings of his wife; be good to his family; educated; not drunk; better if rich; if the behavior is good his looks don’t matter; and he should approve her working and support whatever work she wants to do. At the moment the money for staff salaries comes from World Education, but the group has already made connections with other organizations, including the International Rescue Committee (IRC), to receive

additional support. The group also has ‘endowment fund’ and plans to establish

computer, communication, and advocacy learning, training and service centers to provide services to the local governments. They are also considering becoming a watchdog organization, so that they can hold the government accountable and monitor their activities vis-à-vis minority groups.

foreign aid, fostering private sector involvement is very important to ensure diversification of funding and private-public partnership.

FOCUS ON PROTECTION AND ASSISTANCE

As indicated at the outset of this report very little is known about the situation of survivors of human trafficking upon return to their countries of origin, especially limited are empirical studies of successful reintegration and prevention of re-trafficking (Crawford and Kaufam 2008).

It is worth mentioning that existing studies about human trafficking in Nepal almost exclusively focus on trafficking of girls and women for sexual exploitation. Additionally, it is noteworthy that researchers and practitioners often do not differentiate between adult sex workers who enter the sex industry voluntarily and those who had been trafficked for sexual exploitation (See Weitzer 2007; Soderlund 2005). Many authors suggest that Nepali women become involved in sex work because they are compelled by economic situation and social inequality (Simkhada 2008). Following the stance of many anti-trafficking programs, scholars frequently conceptualize entrance into the sex work stemming from poverty and gender inequality as forced prostitution. The Palermo Protocol, on the other hand, requires the presence of force, fraud or coercion to deem a

person a victim of trafficking. People “forced” by poverty to seek livelihoods in the sex industry would not meet the muster of the trafficking definition unless they are underage. Under international law, minors are conceptualized as having no volition therefore they cannot consent to sex work and are always deemed victims of trafficking.

In the following section, we discuss several programs assisting returned sex workers and/or survivors of trafficking for sexual exploitation. All of the discussed programs

include the words “trafficking” or “victims of trafficking” in their names. The same is true about published works based on research with returned victims, where these word appear in titles, but in the body of the articles authors often interchangeably use the term

STIGMA AS A BARRIER TO REINTEGRATION

The majority of Nepali survivors of human trafficking are rescued by the police or social workers. We heard only about a couple of women who managed to escape on their own. Maiti Nepal has staff members at nine crossings at the Nepal-India border and claims to intercept 2,500 young women annually. Our discussions with representatives of Maiti Nepal indicate that the staff conceptualizes all sex work as sex trafficking. They are also very outspoken against most forms of female migration stating that women embarking on migration journeys do not realize how vulnerable they are to trafficking, especially to brothels in India.

However, not everybody is happy that organizations such as STOP, an affiliate of Maiti Nepal, raid Indian brothels at midnight and forcibly take Nepali women away. Laxmi Pokharel, program officer at ABC Nepal, another local NGO, which rescues and rehabilitates trafficked women, went on record to indicate that some of the women have been rescued against their will (Thinley 2002).

The women we spoke with reported enormous problems in returning to community life due to high levels of stigma placed by society on returned survivors, especially victims of sex trafficking. Other researchers show similar findings. “Frequently, not only society at large but also parents condemn their daughters morally, and repudiate them. They are fully aware that society looks down on them and therefore offers no hope for dignified

life” (Simkhada 2008: 243; see also Hennik & Simkhada 2004). Dahal and colleagues (2015) confirm that social stigma as well as limited opportunities to secure means of support pose enormous barriers to reintegration and reasons of continued social isolation.

promising practices to reduce the stigma or medical services aimed at managing the infection (Silverman et al 2007). In interviews the research team conducted in 2010 and 2013 with women in the Terai, many respondents shared with us that their husbands who work in India have STDs and infect their wives when they return home for an annual visit. Service providers confirmed that migration of men results in the spread of STDs among women that never migrated.

Dahal and colleagues indicate that survivors of trafficking for sexual exploitation “fail to construct their own identities as other than a sexual object, which further escalates their isolation and rejection” (Dahal et al. 2015: 7; see also Chatterjee et al 2006). The traumatic experiences of sexual exploitation, claims Robinson (2007), make it impossible for the survivors to remember the person they used to be. The denial and rejection ensuing from the stigma force survivors to flee their communities, often back to the sex trade (Kelley 2000).

Richardson et al. (2016) conducted an empirical study focusing on 46 Nepali women who left trafficking situations and returned home. The key findings of this study spotlight the effects of stigma; access to livelihoods and skills training; marriage prospects; and citizenship. The researchers emphasize that discrimination and social rejection very much depend on whether the identity of the returning women is protected or disclosed. The authors cite narratives of women who have been handed over by the police to NGOs who in turn post pictures of the returned survivors and spread the news of their rescue

operations thus destroying the women’s izzat (family honor). There also seems to be a geographical hierarchy of stigma where the society perceives women returning from

Delhi or Kolkata as “damaged goods” since the prevailing assumption is that they

worked in the sex industry. Upon return to Nepal, many of these women are forced to migrate internally to preserve their anonymity. Women coming back from Lebanon or Kuwait enjoy a better welcome since labor migration to the Middle East is seen as more prestigious and is not associated with sex work.

Richardson’s research showed that assistance provided to returned women by local

NGOs focused on skills training in traditional female occupations such as sewing and

This research suggests that marriage remains one of the main livelihood strategies for trafficked returnees. At the same time, marriage might not be the best durable solution if

the women’s trafficked identity becomes known to the husband and his family. Many men resort to sexual and physical violence upon finding what their wives did while abroad. However, without marriage, returned women can face difficulties in obtaining citizenship which further limits their livelihood options, curtails their access to government supported services such as healthcare and education, prevents them from securing appropriate housing, and undertake any legal action.

In the latest publication based on the above study, Richardson and colleagues (2016) analyze the relationship between gender, sexuality, and citizenship. They examine

returned women’s access to citizenship in the context of ‘post-conflict’ transformations that took place in Nepal after the country has emerged from a decade of civil war and political infighting and has transformed into a nascent secular democratic republic. The authors argue that citizenship remains inaccessible to many women who have been disowned by their families due to trafficking experiences. Moreover, when women do have formal citizenship, the patriarchal social system in Nepal shapes women’s and girls’ status in communities (See also Rankin 2004; Samarasinghe 2008). It also renders them unequal citizens. In addition to curtailed access to education and health care mentioned above, many returned trafficked women do not have the right to inheritance, ownership of property and land, and non-discriminatory laws on travel and migration. Many

trafficked women also have difficulties furnishing “proof” of citizenship because they lack birth certificates. Without documentation establishing Nepal as their birthplace to underpin an application for citizenship, it seems unlikely that the current situation returnees experience will ever change.

percent were employed in income generating activities (retail or tailoring shops, small hotel, goat raising, and garment industry). The researchers attributed the surprisingly positive reintegration outcomes to the fact that the NGO provided the girls with vocational skills enabling them to set up their own businesses or find work in the community. There are obvious limitations to this study: the sample is very small and is drawn from the population of cases admitted to shelters of one organization.

RETURNED LABOR MIGRANTS

We include in this section of the report a discussion of returned labor migrants. There is a lot more information about returned labor migrants than returned trafficked victims. While many of the returned labor migrants would not qualify as survivors of human trafficking for labor exploitation, many do indeed feel wronged by their employers and are looking for ways to recoup lost earnings.

In 2014, the Government of Nepal published its first consolidated report regarding the status of labor migrants for foreign employment.14 In the report the government includes

information on the number of complaints launched as well as cases registered, settled, and remaining to be settled.

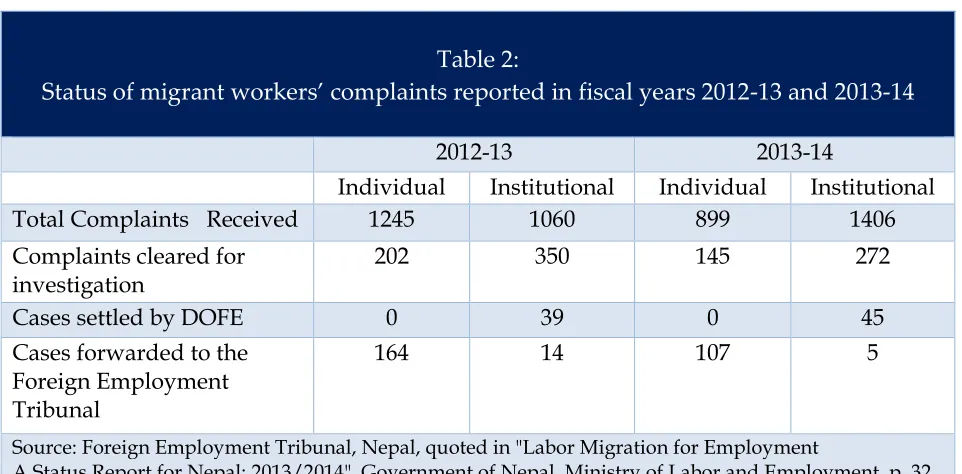

Table 2:

Status of migrant workers’ complaints reported in fiscal years -13 and 2013-14

2012-13 2013-14

Individual Institutional Individual Institutional

Total Complaints Received 1245 1060 899 1406

Complaints cleared for investigation

202 350 145 272

Cases settled by DOFE 0 39 0 45

Cases forwarded to the Foreign Employment Tribunal

164 14 107 5

Source: Foreign Employment Tribunal, Nepal, quoted in "Labor Migration for Employment

A Status Report for Nepal: 2013/2014", Government of Nepal, Ministry of Labor and Employment, p. 32.

A word of explanation is required regarding launched complaints and registered cases. The Department of Foreign Employment registers the complaints they deem appropriate with the Foreign Employment Tribunal. As can be seen from Table 2 above only a small proportion—approximately 16 percent of complaints launched by individuals and 19-33 percent of those launched by institutions—are cleared for investigation. No individually launched complaints have been settled by the Department of Foreign Employment (DOFE). However, DOFE settled a small percentage of complaints launched by institutions; approximately 11 to 16 percent. Interviews with local NGOs indicate that the decision which cases to register is not very transparent. As will be seen later in the report some returned labor migrants think that there is a need for migrants to organize and receive training to be able to launch complaints as organizations instead of as individuals.

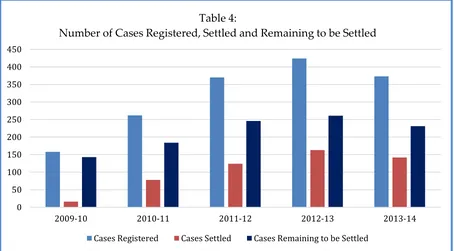

Table 3:

Number of Cases Registered, Settled and Remaining to be Settled

2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14

Cases Registered 158 262 370 424 373

Cases Settled 16 78 124 163 142

Cases Remaining to be Settled

143 184 246 261 231

Source: Foreign Employment Tribunal, Nepal, quoted in "Labor Migration for Employment. A Status Report for Nepal: 2013/2014", Government of Nepal, Ministry of Labor and Employment, p. 32.

Table 4 below depicts the trends discussed above in a graphic form and visually points out the discrepancies between launched complaints and adjudicated cases. We want to emphasize here that we are not necessarily interpreting these data as cases of trafficking for labor exploitation, although it is conceivable that some of the exploitation would meet the muster of the international definition of human trafficking. According to the Nepali Government and stakeholders interviewed in the course of this research, most labor migrants, even those that were wronged by their employers, do not identify as victims of trafficking. It would be interesting to know if there are any differences in levels of exploitation between legal and irregular labor migrants. Unfortunately, there is no data available to make such comparisons. The data the government report discussed refer to labor migrants who used a variety of recruitment agencies to secure employment outside Nepal.

Source: Foreign Employment Tribunal, Nepal, quoted in "Labor Migration for Employment. A Status Report for Nepal: 2013/2014", Government of Nepal, Ministry of Labor and Employment

Individuals that launch complaints about their experience working abroad, receive no other assistance from the government in order to reintegrate into their communities. Many of the interviewed labor migrants plan on seeking employment abroad again, hoping that they will find better opportunities in a different country. It seems that migrants who experienced exploitation while working abroad ought to be referred, at

minimum, to programs providing information about safe migration and workers’ rights. As will be discussed later, there are several NGOs that provide such services. However,

0

Number of Cases Registered, Settled and Remaining to be Settled

knowledge of their existence is not as extensive as is warranted. The Department of Foreign Employment and/or the Foreign Employment Tribunal ought to establish a referral system and provide support to these NGOs.

RETURNED TRAFFICKING SURVIVORS

The number of annually returning survivors of human trafficking is unknown in Nepal (Pranab Dahal et al. 2015) since the Government of Nepal does not collect data on any form of human trafficking. According to the 2015 TIP Report, immigration officials reportedly do not notify police of possible trafficking crimes when abused migrant workers return to Nepal, and instead urge them to register complaints under the Foreign Employment Act of 2007 (FEA). However, due to pressure from influential suspects, police sometimes interrogate victims to discourage them from filing cases.

At the time of this research, the IOM Global Trafficking Database was not available for independent analysis. However, the existing reports indicate that IOM assisted 188 Nepali victims between the years of 2000-2010; 178 victims in 2010; and 116 victims in 2011.15 It is difficult to discern whether all of the assisted individuals were returned

victims or were provided services in destination countries prior to return to Nepal or both. The published statistics do not correspond with the estimates provided by IOM Nepal. According to Meena Paudel, IOM assisted some 400 female returned victims in 2010 alone (Personal communication 2010). IOM was not able to provide estimates for later periods during our site visit in December 2015. These numbers also do not correspond with the estimates discussed at the outset of this report indicating that thousands of Nepali women and girls are trafficked every year to India and beyond.

The national minimum standards for victim care set forth procedures for referring identified victims to services. However, referral efforts remain ad hoc and inadequate. The Ministry of Women, Children, and Social Welfare (MWCSW) continues to partially fund eight rehabilitation homes and emergency shelters for female victims of gender-based violence, including trafficking. The government does not fund shelter services for adult male victims in Nepal, although there was one NGO-run shelter for men in Kathmandu during the reporting period covered by the 2015 TIP report. There were reports that some

of these shelters limited victims’ ability to move freely. This is not surprising since in

other countries included in this research, protection of victims, especially women and children, was often operationalized as placement in locked facilities. The government continued to run emergency shelters for vulnerable female workers—some of whom were likely trafficking victims—in Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates. Nonetheless, shelter capacity was insufficient to adequately respond to the demand for rescue services and assistance abroad (TIP Report 2015).

Research indicates that most of the returning survivors of trafficking do not use rehabilitation and shelter homes (Dahal et al. 2015). Reintegration is a difficult process in Nepal since women who were trafficked for sexual exploitation are stigmatized by their families and communities (see Chen and Markovici 2003; Mahendra et al. 2001). Interviews with service providers such as Maiti Nepal and Shakti Samuha confirm these

assertions. Discussions with returned male labor migrants also suggest that “a failed

migration project” defined as migration that did not result in anticipated levels of earnings is also shameful.

Despite these obstacles to reintegration, there are several organizations that work with returned victims. We list them here alphabetically and describe them briefly below.

ABC NEPAL

ABC Nepal, a local non-profit human rights organization with a special focus on trafficking of women and children for the purpose of sexual exploitation has been in existence since 1987. ABC/N runs a wide range of programs, including education and awareness programs in trafficking prone communities; provide skills training and create savings and credit cooperatives for women; provide formal and non-formal education for girls and women; and also basic medical services at field clinics. For the purpose of

this research, the most important elements of ABC/N’s operations are three transit homes