State Promoted Technology Consortia In India: Internal and External Factors Influencing

the Realization Of Initial Objectives

S Raghunath Joseph Shields Indian Institute of Management, India

Abstract

The factors, which influence the functioning of state, promoted technology consortia are studied here. Two cases, one a technology development consortium and the other a technology deployment consortium were studied in this research. Both the internal and external factors were taken into account to understand the performance of the consortia. While in both the cases the non-participatory, but facilitating role of the state helped the consortia getting established and achieves its initial objectives smoothly. From the point of view of internal organization, corporate governance through establishment of independent corporate entities wherein the workforce was independent of functional loyalties to any of the consortium participants helped immensely in the success of the consortia. In both the cases, market attractiveness played a vital role of the consortium success. Among the external factors, availability of alternatives and the lack of competitive positioning of the impeded the growth of the technology deployment consortium studied. Participation of the technology users as stakeholders in the consortium aided the success of the technology development consortium. The user base was also small and formed part of the consortium. It was however not the case with the technology deployment consortium where the technology users were outside the consortium. The user base was quite large and had no stakes in the consortium. This resulted in the success of the technology deployment consortium not being as high as what was initially expected. The participation of the state in competing ventures also impeded the speedy realization of initial objectives in the case of the technology deployment consortium.

Introduction

State promoted technology consortia have been instrumental in enhancing national competitive advantages of various countries. Researchers [26], [29], [16], [10] have observed that technology consortia have been formed with various goals ranging from funding of basic R&D, technology and market coordination, overcoming technological discontinuities, funding risky ventures, standardization of technology and products, byproduct utilization, management training, competence building to improve national competitive advantage etc.

Worldwide, various consortia were established with government support and participation. SEMATECH, established in 1987 to develop semiconductor production technology with a US$ 1.7 billion budget as of 1996 had half of its funding from the government. The European Strategic Programme for Research and Development of Information Technology (ESPRIT), the EUREKA, the Japanese Fifth Generation Computer Project etc., are just a few more examples of state promoted technology consortia. In a recent study of over 200 consortia in Japan [23] it was found that governmental support is declining in technology consortia and the benefits expected now from governments are more of an intangible nature. It was also found that even the motivations for the formation of such consortia and expectations from the non-government partners are different now compared to what they were in the earlier cases. While the experiences of Sematech, Eureka, the semiconductor industry consortia in US, Japan and Taiwan were well researched [15], [5], [9], [27] the technology consortia in India with state participation are yet to be studied in detail.

Research Objective

effort to study the dynamics of Indian technology consortia with state participation and from the point of view of the determinants of success.

The following research questions were addressed:

1. What are the motivations for the formation of state promoted technology consortia in India 2. What are the internal and external factors that effect the realization of these objectives

Methodology

Technology consortia typically cover a range of emerging technologies including Information Technology, Biotechnology, Pharmaceutical, Telecom and Speciality Chemicals. These consortia represent a new organizational form and they pose management challenges. This study is based on case studies of consortia with private sector participation with a degree of government involvement. Government can have a significant influence on the formation of consortia including input on the type of participants who will be involved and the directions the consequent results will take [23]. The consortia selected for case studies are based on the criteria that the projects and the output of the consortia involve cooperation among private sector firms. In other words, consortia which involved primarily government participation and those in which the government agency simply allocated tasks without the initiative of the private sector were excluded. The cases considered were the International Technology Park Ltd., Bangalore in the Information Technology industry and the Biotech Consortium India Ltd., Delhi in the Biotechnology industry. These case studies include cooperative projects sponsored by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India and the Government of Karnataka (through the Karnataka Industrial Areas Development Board – KIADB).

At the outset, the target population of case leads considered for the study was the following. 1) Technology Development Consortia

a. Biotech Consortium of India Ltd., New Delhi (Biotechnology industry)

b. Non-ferrous Materials Technology Development Center, Hyderabad (Defence Sector) c. Custom Molecules Pvt Ltd., Hyderabad (Pharmaceutical Industry)

2) Technology Deployment Consortia

a. International Technology Park Ltd., Bangalore (Information Technology Industry) 3) Marketing Consortia

a. VSNL-MTNL-TCIL consortium (Telecom Industry)

As the VSNL-MTNL-TCIL consortium was more of a marketing entity between three state owned firms and no private sector participation, it was not considered for the purpose of the study as a technology consortium. Custom Molecules Pvt. Ltd., a newly formed consortium between the Bulk Drug Manufacturers Association, the Government of Andhra Pradesh and 8 SMEs was also not considered for the study as it is a relatively new entity and it may not be possible to understand as of now whether or not the initial objectives are met. The Non-ferrous Materials Technology Development Center, a consortium between the Defence Metallurgical Research Laboratory and four state-owned firms in the mining and metals business was also dropped from the study due to strategic reasons as it addresses the defense sector.

Eventually two consortia were chosen for the study, the BCIL, which is a Technology Development Consortium, and the ITPL, which is a Technology Deployment Consortium.

Limitations of the Study

consortia was not an easy task given the busy schedule of these senior managers. Eventually, data was collected through a combination of face-to-face interviews and telephonic question and answer sessions.

Both the consortia considered here viz., the ITPL and the BCIL were not predominantly state funded and therefore the government did not have a majority stake in the consortia. Thus, the findings of this research may not be generalizable for consortia with predominant state funding. Both the consortia, which form the focus of this study, are separate legal entities. Thus, the findings may not necessarily apply to consortia formed without a separate legal identity being incorporated.

Use of Technology Consortia

The need to leverage scarce scientific and technical talent, and the desire to share the risks associated with technology generation and commercialization drives firms to band together in cooperative activities. Technology activities are complex and hence call for reducing the risks for firms involved in either developing or deploying them. Such activities are characterized by uncertainty, indivisibility and inappropriability [14]. The uncertainty associated with new technology development and deployment makes it difficult for firms to understand or predict the possible outcomes of associating with the technology. The indivisibility of the technology calls for firms to share their resources and knowledge, in order to collectively deal with the various interlinked elements of the technology. The difficulties associated with appropriating technology calls for firms to partner for transferring the knowledge to the right users at the right time. The knowledge involved in transferring the technology is very critical here. Time and again governments have participated in facilitating such multi-lateral partnerships between firms either for Technology Development or for Technology Deployment. Such efforts have lead to the formation of consortia.

Consortia are considered to be intermediate governance forms between markets and hierarchies [30], [13]. Consortia can be distinguished from other interorganizational forms such as joint ventures, technology licensing, subcontracting etc., along the following parameters:

- They typically involve multifirm rather than dyadic interfirm cooperation - They usually involve horizontal collaboration among direct competitors

Technology consortia thus constitute a subset of organizational forms involving formal interfirm cooperation among potential competitors from the same industry [6] and most of the collaboration is in the precompetitive stages [14]. However, with the pressure on time to market increasing and also the product development cycles being compressed into the product marketing activities, the very nature of the consortia is also changing with the line between pre-competitive and competitive stages slowly getting effaced.

In a comparative study between R&D consortia in US and Japan, it was found [1] that internal diversity and interorganizational relations in consortia have an impact on information exchange and governance mechanisms. Thus the diversity among participating firms and the nature of relationships they engage into would have implications on the success or failure of a consortium and also the governance costs that influence such a success or failure.

Factors Effecting Consortium Performance

Since consortia are often composed of companies that seek mutual benefits but remain competitors otherwise, they are composed of personnel from radically different corporate cultures, shareholders with different managerial priorities, policies and procedures. As a result, managing consortia poses a major challenge. There are a variety of possibilities in terms of the organizational structure, technological emphasis, funding mechanisms and personnel make-ups possible in consortia. These choices are a fall out of the mechanisms in place to avoid failure of the consortia and also in order to achieve the initial objectives set forth. The geographic shift, person-to-person, group-to-group and organization-to-organization interactions influence the ease of governance of a consortium and also the benefits accrued to the participant firms.

processing, equivocality of objectives, organizational processes relating to recruiting personnel, obtaining resources, decision making, evaluation of outputs, bureaucracy, retention of members etc., and external issues like culture of the country, institutional environment, legal issues, distance between the partnering firms, competitive positioning of the consortium etc [24], [6], [12], [17], [3]. Researchers [17] have found that all these governance issues lead to an increase in the transaction costs, which have been found to be the key determinants of the success or failure of consortia. They have also found that the effect of power dependence is much less compared to the effect of transaction costs.

Apart from incongruity of goals, bureaucracy and cultural factors, many technology consortia were found to be failures on account of the improper split of activities across various participating firms [28]. Closely related to this is the level of importance each of the partners attach to the technology being dealt with. Typically in consortia dealing with technology transfer, the willingness of the recipient to receive the technology as well as the willingness of the owner to transfer the technology are critical for the success of the consortium [20]. Recipients of the technology can be outside the consortium also. These are the end users in the marketplace. The market conditions and the utility value the end users attach to the technology as a tool or a product in the marketplace becomes critical here.

The nature and internal alignment of the relationship between the participating firms signified by the degree of procedurality, competitiveness or collegiality, involvement or distance, individualism or supportiveness, apart from the stress in the relationship determines the success of consortia [31]. Apart from this, the perception of the participating firms about the consortia also matters much in the performance of the consortium. Often firms view consortia as forced cooperative ventures [3]. This attitude of indifference could lead to opportunism and thus erode the benefits of a consortium. Several organizational mechanisms like individual structures and central controls are employed in order to overcome this problem in consortia. The importance attached to the consortium by the individual firms, the resulting involvement by each of these firms in the consortium, as well as the alternatives available would determine the success of the relationship [17].

On the relationship front, consortia performance has also been found to be closely coupled with the tightness of the individual level relationships between the decision makers of the consortia and the proponents of the consortia [18]. Thus more than the organizational-level networks, the individual level networks also play a vital role in the effective functioning and success of the consortia. The value addition each partner brings on account of their network ties with participating members, also determines the success of a consortium [17], [8], [4], [21]. Such ties would prevent the participating firms from indulging in opportunistic behavior. The ties that firms have outside the network could add additional value to the relationship as this could help commercially sustain the technological efforts of the consortium.

The functional loyalty [3] of the staff to their parent companies plays a vital role in their allegiance to the consortium and thus has a positive or detrimental effect on the results gained. Staffing is a key problem in consortia. The staff could be directly hired for the new entity floated or they could be deputed from the individual firms partnering in the consortium. Researchers have also found that the attitudes and expectations of the direct hires and deputed employees of the shareholders are different and the effects of these are reflected in the performance of the consortium [25].

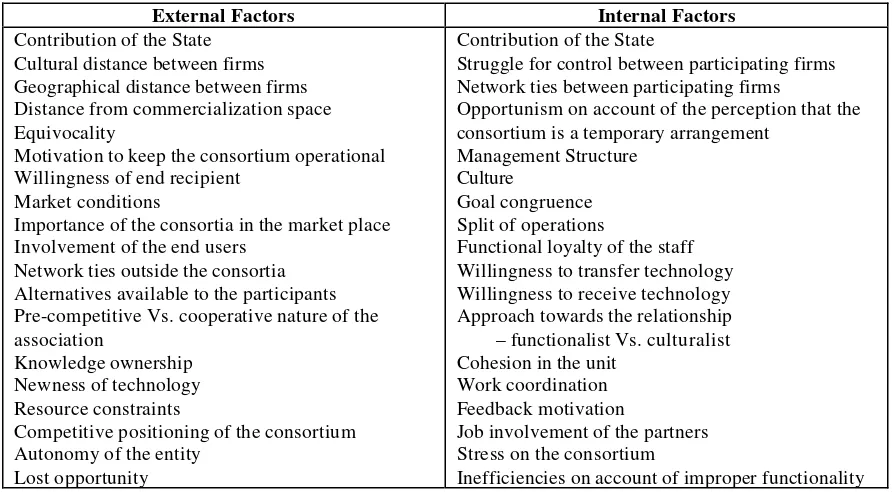

Table 1:INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL FACTORS INFLUENCING STATE-PROMOTED TECHNOLOGY

Motivation to keep the consortium operational Willingness of end recipient

Market conditions

Importance of the consortia in the market place Involvement of the end users

Network ties outside the consortia Alternatives available to the participants Pre-competitive Vs. cooperative nature of the association

Struggle for control between participating firms Network ties between participating firms

Opportunism on account of the perception that the consortium is a temporary arrangement

Inefficiencies on account of improper functionality These factors could however be different for technology development consortia and technology deployment consortia. Not all of these factors could be relevant for both types of consortia. The following sections would chart the evolution and functioning of one case each of the technology development consortia and technology deployment consortia and bring out the distinctions between the internal and external factors that effect the performance of the same.

Case of a Technology Development Consortium: Biotech Consortium India Ltd., Delhi

This consortium was started in 1990 at the initiative of the Department of Biotechnology of the Government of India, with a core capital of US$ 1.2 m. A major part of the initial investment came in from five Indian Financial Institutions viz., IDBI, ICICI, IFCI, UTI and RCTC. Apart from this a host of companies from the corporate sector viz, Ranbaxy Laboratories, Glaxo India, Cadila Laboratories, Lupin Laboratories, Kothari Sugars and Chemicals, Rallis India, SPIC, Madras Refineries, Zuari Agro, EID Parry, ACC and Excel Industries joined the consortium, with some investments from their side.

In the biotechnology industry, as realization of technological initiatives into commercial ventures could not take place in the absence of adequate scale up, the Department of Biotechnology felt the need to set up BCIL to undertake a continuous exercise to screen these technologies, interface between technology sources and technology seekers, assist in technology sourcing, marketing tie-ups and identification of joint venture partners.

The consortium was set up with the following objectives:

- Providing the linkages to facilitate accelerated commercialization of biotechnology - Technology development

- Technology transfer - Project consultancy - Fund syndication

- Manpower training and placement

The technology commercialization process was facilitated by the following: - Financing scale up from lab scale to pilot plant demonstration unit

- Packaging to enable entrepreneurs/industry and financial institutions to assess the commercial potential

- Industrial tie-up for scaling up from pilot plant to commercial level - Patenting of technology

-Role of the State

The consortium was first initiated by the State through the Department of Biotechnology. There was however no funding from the state. The State consciously refrained from having its personnel in the workforce of the company. However, the Secretary of the Department of Biotechnology and the heads of the CSIR and ICAR, two state run R&D councils are Directors on the board of the company. The Directors add value by bringing in the linkages from the basic R&D labs in the country. The state through the Department of Biotechnology also helps in developing specifications for the technology and standardizing the technology. The conscious step taken by the state to refrain from any management control over the consortium has enabled the consortium record good performance leveraging the flexibility that was built into the system.

Role of Other Stakeholders

The firms, which are part of the consortium, help in gauging the technology trends and also in taking the consultancy and technology development services of BCIL. They play the role of a captive market and also that of designers and drivers of the technology being incubated in the labs. Apart from this they also act as technology transfer channels for the company.

The financial institutions have their presence in the company more as equity holders as they had brought in the initial investment.

Market Attractiveness

All the firms in the consortium apart from the financial institutions are users of the technology and help BCIL incubate and commercialize those specific technologies, which they intend to transfer to the marketplace for being used by the end customers. The presence of a captive market and also the involvement of the recipients of technology as partners in technology development and commercialization has resulted in BCIL catering to a highly attractive market.

Governance Structure and Staffing

The consortium is being operated as a separate legal entity and was incorporated as a separate company according to the Indian law. This gives the consortium a high degree of flexibility in its operations and also having direct hiring for its employees. As a result it does not possess any conflict of interests between its goals and those of its employees, as these employees do not have any affiliations with the partnering firms. This has been a critical success factor of the consortium.

Network Ties of the Parties

In summary the following table captures the major factors, which enabled BCIL to be a high performing state promoted technology consortium.

Performance of the Consortium

The facilities are currently benefiting over 120 clients, scientists, technologists, research institutions, universities, first generation entrepreneurs, the corporate sector, government, banks and financial institutions. The company has successfully commercialized and licensed out a host of indigenous technologies in the areas of biopesticides, neem pesticides, bacterial biofertilizers, Microbial aerobic fermentation, Lactic acid and derivatives etc., and a host of international technologies like spirulina production, extraction of papain from papaya, b-carotene production etc. Apart from these, blue green algae, bacterial biofertilizers, HIV detection kits and Pearl culture are some of the technologies in the process of commercialization.

The consortium was a recent recipient of the National Award for the Best Efforts in Commercialization and has been recording profits over the years. Apart from the initial investment, there has been no further funding for the consortium and the revenues are being generated purely through their own activities.

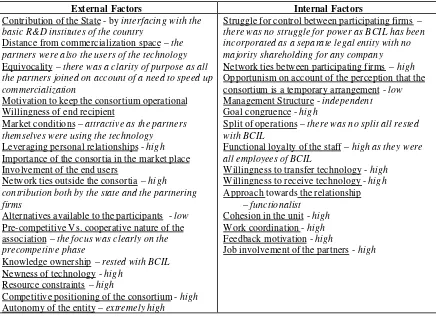

Table 2: INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL FACTORS INFLUENCING PERFORMANCE OF BCIL

External Factors Internal Factors

Contribution of the State - by interfacing with the basic R&D institutes of the country

Distance from commercialization space – the partners were also the users of the technology Equivocality – there was a clarity of purpose as all the partners joined on account of a need to speed up commercialization

Motivation to keep the consortium operational Willingness of end recipient

Market conditions – attractive as the partners themselves were using the technology Leveraging personal relationships - high Importance of the consortia in the market place Involvement of the end users

Network ties outside the consortia – high contribution both by the state and the partnering firms

Alternatives available to the participants - low Pre-competitive Vs. cooperative nature of the association – the focus was clearly on the precompetitve phase

Knowledge ownership – rested with BCIL Newness of technology - high

Resource constraints – high

Competitive positioning of the consortium - high Autonomy of the entity – extremely high

Struggle for control between participating firms – there was no struggle for power as BCIL has been incorporated as a separate legal entity with no majority shareholding for any company Network ties between participating firms – high Opportunism on account of the perception that the consortium is a temporary arrangement - low Management Structure - independent Goal congruence - high

Split of operations – there was no split all rested with BCIL

Functional loyalty of the staff – high as they were all employees of BCIL

Willingness to transfer technology - high Willingness to receive technology - high Approach towards the relationship – functionalist

Cohesion in the unit - high Work coordination - high Feedback motivation - high

Case of A Technology Deployment Consortium: International Technology Park Ltd.,

Bangalore

The city of Bangalore in South India has come to be known as the Silicon Valley of India. It has over 900 IT companies contributing a major chunk to the US$ 1.58b software exports from India. Over the years 1999-2000 Bangalore has experienced an exponential growth of 73% in its software export revenues and has reached a business of US$ 16.6m. One of the major infrastructural requirement for IT companies in India is the technology in terms of uninterrupted power supply and high speed communication backbone to their clients in US in order to have a 24 hour interface and make effective use of the differentials in time zones. With the latest advances in broadband and Internet technologies it was felt that there was a need to make these technologies available at a pool for IT companies in Bangalore. Also the power supply fluctuations called for establishing power generation units to cater to multiple users under the same roof at lower prices.

The Information Technology Park Limited was set up with an initial outlay of US$ 1.2m to provide efficient & reliable infrastructural services offering a dynamic business platform of international standards to the IT companies based in Bangalore. It was conjured by the best brains and corporate enterprises from both India and Singapore, who are experts in the formation and management of high-tech business superstructures. The consortium was formed between The Tata Industries Ltd., the investment arm of the Tata Group one of India's largest conglomerates with more than 80 companies in diverse businesses, the Singapore Consortium, a consortium of Singapore companies, led by Ascendas Land International Pte. Ltd., associated with successful industrial and science parks in Singapore, China and other Far East nations and the Karnataka Industrial Areas Development Board (KIADB), a statutory body of the Government of Karnataka, India.

The International Tech Park, Bangalore was set up to provide a one-stop solution to multinationals and other conglomerates for conducting high-tech and knowledge-base business in India in an environment based on the integrated concept of work, live and play. High quality professionally-managed services apart from state of the art communication facilities like video conferencing, high speed data transfer links, uninterrupted power supply etc., were provided at the park.

The Park already houses corporate majors operating in a wide range of businesses, such as information technology, biotechnology, electronics, telecom, R&D, financial services, and other IT-related services. With the commissioning of Stage 2, the park is gearing up for extending its commitment to the new occupants.

The fully occupied Phase 1 of the Park stands on a 27 hectares (68 acres) plot in Whitefield, Bangalore. Whitefield is located 12 kms from Bangalore airport and 18 kms from the city. The ready-built facilities; infrastructure like power, water, telecommunication and satellite connectivity as well as other value added services offer companies a quick start up - a distinct advantage over others who have to start from scratch and put in heavy upfront investment. The first phase of the project comprises three buildings - Discoverer, Innovator and Creator, totaling close to 1.2 million square feet of built up office, production and retail space. A 51-unit residential tower, situated in the Park, also enjoys the facilities of the Park like power, water and recreation.

Electricity being a major constraint in Bangalore. ITPL as its own 9 MW (3x3) Dedicated Power Plant. This is synchronized with the 220 KV grid of the Karnataka Power Transmission Corporation Limited. The synchronized power is redistributed to the clients thereby ensuring reliable and clean power supply 24 hours a day. ITPL is the only such establishment in Karnataka to receive power from the Utility Board (KPTCL) at the highest voltage level i.e. at 220,000 volts. The power supply at 220 kV ensures that is far more dependable than what is available at lower voltage levels to other consumers in the State (11 kV for e.g.) The supply to the Park is through two such 220 kV lines from two different substations of KPTCL thus ensuring 100% redundancy.

Role of the State

The participation of the state in the consortium was through a statutory body called the KIADB. The objective of the state in participating in the venture was to help in the overall industrial growth of Karnataka and also to generate employment. Since it was expected that most of the companies occupying the park would be from the IT industry, the state expected to have Bangalore on the IT map of the world by providing high quality infrastructure, which could attract the best companies in the world to Bangalore. The state helped in procuring the land and the necessary clearances.

Role of Other Stakeholders

The Tatas were instrumental in bringing in the investment and the Singapore consortium with its vast expertise in building similar technology parks enabled to develop the park as a good international destination by bringing in its technical expertise and apart from the investment. The Tatas also leveraged on their relationship with the government and helped the Singaporeans cope with the cultural aspects of managing the consortium and its dealings with the external interfaces.

Market Attractiveness

As mentioned earlier, the market for software exports has been quite attractive and Bangalore as a destination for IT companies had also been an attractive proposition. India has a great advantage in the IT world map as it has a good low-cost high-quality manpower, and is the second largest English speaking manpower resource to the world. The IPR laws in the country are also quite attractive.

Governance Structure & Staffing

As the state helped in procuring the land and the necessary clearances and in return was given a 20% equity in the consortium. The rest of the partners the Tatas and the Singapore Consortium were given a 40% state each. Each of the partners have a proportionate representation in the board. The ITPL was incorporated as a separate corporate entity under the Indian law and has employed its one sole employees. The park is currently headed by a CEO from Singapore. The government refrained to depute its employees as staff of the ITPL. It was agreed that the Chairman of the consortia would be a nominee of the Tata group and the CEO would be a nominee of the Singapore consortium. Initially some personnel were deputed at the senior level from both the parties in order to establish the consortium. There was however no such participation from the state.

Network Ties of the Parties

The government was able to leverage its linkages by getting the necessary clearances and also procuring the land.

Performance of the Consortium

The consortium is considered to be moderately successful as it was not at the pace, which was expected. Plans are however afoot for the phase-II. The schemes offered by the STPI (Software Technology Parks of India), an autonomous association floated to promote the software industry, were taken as a better proposition by many firms due to the tax and import duty concessions and the flexibility in location. As a result large corporates set up their own technology parks closer to the city of Bangalore than ITPL and still enjoying the same infrastructural facilities built by them as those existing at ITPL. It was the smaller firms, which could not afford their own infrastructure in communication, and power that opted for ITPL. However, as the STPI also set up cost effective large technology parks in the Electronics City promoted by the Government of Karnataka, some of the smaller IT companies found attractive to occupy those office spaces due to proximity to the city of Bangalore and availability of cost effective space.

Table 3: INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL FACTORS INFLUENCING PERFORMANCE OF ITPL

External Factors Internal Factors

Contribution of the State - by interfacing with the government for clearances

Distance from commercialization space – high Market conditions – attractive

Importance of the consortia in the market place – not very high as there were other alternative sources

Network ties outside the consortia – high contribution both by the state

Nature of technology – investment intensive Competitive positioning of the consortium - low Autonomy of the entity – moderately high

Struggle for control between participating firms – there was no struggle for power as ITPL has been incorporated as a separate legal entity with no majority shareholding for any company

Management Structure – independent. However it was agreed that the Chairman would be from the Tata group and the CEO would be from the Singapore consortium.

Split of operations – there was no split all rested with ITPL

Functional loyalty of the staff – high as they were all employees of ITPL

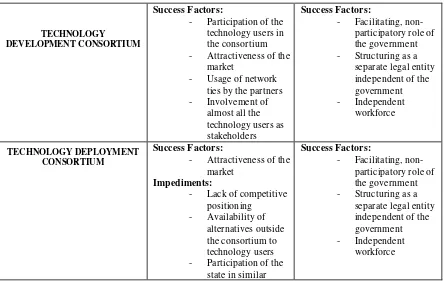

Summary of Findings

The following grid depicts the critical success factors and the detrimental factors both internal and external for the technology development and the technology deployment consortia. The role of the government, which enables the consortia to reach a level of success, is also listed.

competing ventures - Large number of

technology users and the inability to incorporate them as stakeholders

EXTERNAL FACTORS INTERNAL FACTORS

References

[1] Aldrich, H.E., Bolton, M.K., Baker, T., & Sasaki, T. (1998). Information Exchange and Governance Structures in U.S., and Japanese R&D Consortia: Institutional and Organizational Influences. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, Vol. 45, No.3, 263-275.

[2] Blodgett, L. (1992). Factors in the Instability of International Joint Ventures: An Event History Analysis. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 13(6), 475-481.

[3] Brown J.H.U (1981). The Research Consortium – Its Organization and Functions. Research Management, Vol. 24(3), 38-42.

[4] Buckley, P. & Casson, M. (1988). A Theory of Cooperation in International Business. In F.J.Contractor & P.Lorange, (Eds.), Cooperative Strategies in International Business: Joint Ventures and Technology Transfers Between Firms (pp 31-53). New York, NY: Lexington Books.

[5] Chang P. & Tsai C (2000). Evolution of Technology Development Strategies for Taiwan’s Semiconductor Industry: Formation of Research Consortia. Industry and Innovation, Vol. 7(2), 185-197.

[6] Evan W.M. & Olk P. (1990). R&D Consortia: A New U.S. Organizational Form. Sloan Management Review, Spring, 37-46.

[7] Geringer, J.M. & Hebert, L. (1991). Measuring Performance of International Joint Ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, Vol.22, 249-263.

[8] Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic Action and Social Structures: The Problem of Embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, Vol.91, 481-510.

[9] Ham R.M., Linden G., & Appleyard M.M (1998). The Evolving Role of Semiconductor Consortia in the United States and Japan. California Management Review, Vol. 41(1), 137-163.

[10] Hawkins R. (1999). The Rise of Consortia in the Information and Communication Technology Industries: Emerging Implications for Policy. Telecommunications Policy, Vol. 23(2), 159-173.

[11] Killing. J.P. (1983). Strategies for Joint Venture Success. New York, NY: Praeger.

[12] Kopczynski M. & Lombardo, M. (1999). Comparative Performance Measurement: Insights and Lessons Learned from a Consortium Effort. Public Administration Review, Vol 59(2), 124-134.

[13] Lorange, P. & Probst,G. (1987). Joint Venture as Self-Organizing Systems: A Key to Successful Joint Venture Design and Implementation’. Columbia Journal of World Business, Vol.22(2), 71-77.

[14] Lucchini, N. (1998). European Technology Policy and R&D Consortia: The Case of Semiconductors. International Journal of Technology Management, Vol.15 (6/7), 542-555.

[16] Nathalie L. (1998). European Technology Policy and R&D Consortia: The Case of Semiconductors. International Journal of Technology Management, Vol. 15(6,7), 542-555.

[17] Olk P. & Young, C. (1997). Why Members Stay in or Leave and R&D Consortium: Performance and Conditions of Membership of Continuity. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 18 (11), 855-877.

[18] Olk P. (1998). A Knowledge-Based Perspective on the Transformation of Individual-Level Relationships into Inter-Organizational Structures: The Case of R&D Consortia. European Management Journal, Vol. 16(1), 39-49.

[19] Parkhe, A. (1993). Strategic Alliance Structuring; A Game Theoretic and Transaction Cost Examination of Interfirm Cooperation. Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 36, 794-829.

[20] Pinkston J.T. & K.D.Walters (Ed.) (1989). Technology Transfer: Issues for Consortia in Entrepreneurial Management. Massachusetts: Ballinger Publishing Company.

[21] Provan (1993). Embeddedness, Interdependence and Opportunism in Organizational Supplier-Buyer Networks. Journal of Management, Vol.19, 841-856.

[22] Raghunath, S. (1998). Joint Ventures: Does Termination Mean Failure? Management Review, Jan-Jun, 11-17.

[23] Sakakibara, M. (1997). Evaluating Government-Sponsored R&D Consortia in Japan: Who Benefits and How? Research Policy, Vol. 26, 447-473.

[24] Smilor R.W. & Gibson D.V. (1991a). Accelerating Technology Transfer in R&D Consortia. Research Technology Management, Jan-Feb., 44-49.

[25] Smilor R.W. & Gibson D.V. (1991b). Technology Transfer in Multi-Organizational Environments: The Case of R&D Consortia. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, Vol.38(1), 3-11.

[26] Souder W.E. & Nassar, S. (1990). Choosing and R&D Consortium. Research Technology Management, March-April, 35-41

[27] Spencer, W.J. & Grindley, P. (1993). SEMATECH After Five Years: High Technology Consortia and U.S. Competitiveness. California Management Journal, Summer, 9-32.

[28] Van Den Hooff, H. (1993). European Technology Development Consortia: Dangerous Liasons? European Management Journal, Vol. 11(2), 223-228.

[29] Werner, J. (1992). Technology Transfer in Consortia. Research Technology Management, May-June, 38-43.

[30] Williamson, O.E. (1975). Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications. A Study in the Economics of Internal Organization. New York, NY: Free Press.