Volume 6 Number 1 2009 www.wwwords.co.uk/ELEA

‘Get Some Secured Credit Cards Homey’:

hip hop discourse, financial literacy and the

design of digital media learning environments

BEN D

EVANE

Department of Curriculum & Instruction,

University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA

ABSTRACT In the midst of the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, there exists a deficit of compelling financial education curricula in urban schools that serve financially vulnerable working-class students. Part of a design-based research investigation aimed at creating culturally-relevant financial literacy learning environments, this study is a Discourse analysis of a discussion of personal finance on a web-based fan forum dedicated to hip hop music and culture. In this analysis the author claims that the discourse strategies and participant roles present in this discussion are an example of the organic production of what has been called a borderlands Discourse that bridges school-based knowledge of financial literacy with the youth culture of hip hop. The analysis presented here highlights the complex and overlapping ways that discursive hybridity in both representational practices and textual performances of identity figure importantly in the financial literacy practices of community

participants. The author further contends that the understandings that emerge from this analysis can help design researchers attempt to ‘engineer’ the values, identities and modes of interaction of hip hop discourse communities into academically-oriented learning environments.

designers’ understandings as we attempt to ‘engineer’ compelling roles, practices and values into digital learning environments.

In an effort to develop a set of sociocultural design tools that help designers orient themselves toward the identities and cultures of their design project’s intended audience, this article presents a design investigation that uses Discourse analysis (Gee, 2005) to examine a discussion of personal finance on an web-based fan forum dedicated to hip hop music and culture. In this analysis I claim that the discourse strategies and participant roles present in this discussion are an example of the organic production of a borderlands Discourse (Gee, 1999) that bridges school-based knowledge of financial literacy with the youth culture of hip hop. The analysis presented here highlights the complex and overlapping ways that discursive hybridity in both representational practices and textual performances of identity figure importantly in the financial literacy practices of community participants. I further contend that the understandings that emerge from this analysis can help design researchers attempt to ‘engineer’ the values, identities and modes of interaction of hip hop discourse communities into academically-oriented learning environments.

Background

‘Born in the Bronx’: entrepreneurialism and hip hop

Hip hop culture – now a widespread global phenomenon – arose as a response of marginalized working-class urban youth to economic hardship and social fragmentation in their communities. In the 1960s the construction of the Cross-Bronx Freeway that displaced tens of thousands of working-class residents (Caro, 1975), the flight of hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs from the area, and a de facto, unofficial New York City policy of ‘slum clearance’ (Jonnes, 2002) all contributed to a perfect storm of socioeconomic catastrophe in the South Bronx. By the early 1970s, real estate value had depreciated so much in the area that it was common practice for slumlords to set fire to their properties, which were still occupied by tenants, in order to collect insurance policies, leading to a loss of housing capacity that reached 80% in some neighborhoods (Wallace & Wallace, 1999). In the fall of 1973, a pair of teenage Bronx siblings, brother and sister, whose Jamaican-immigrant family had been driven out of their previous home by one of these fires, began throwing parties in the recreation room of their apartment complex – price of admission: 50 cents – for their high school friends in order to make money to buy back-to-school clothes. The brother, a young graffiti artist who became known as DJ Kool Herc, reverse-engineered his father’s sound system to output extra volume, and developed a technique of back-cueing two copies of the same record in order to extend the popular breakbeat-only section of soul/funk songs indefinitely for party-goers (Chang, 2005). In this way, the music of hip hop was born of creativity, ingenuity, community and entrepreneurialism in the midst of urban poverty and devastation.

identity in the culture (Guins, 2007), hip hop, unlike other culture industries, uniquely emphasizes values of minority economic cooperation and solidarity similar to those articulated by W.E.B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey and Booker T. Washington (Alridge, 2005; cf. Basu & Werbner, 2001). For instance, Black Star, widely accepted as a canonical hip hop act, took the money from their first record contract and invested it in a historical, financially struggling Afrocentric bookstore in their hometown of Brooklyn, while rapper Paris offers detailed financial asset-building guides from his website (Guins, 2007). While the discourse of hip hop is largely banished from mainstream social institutions like schools, it speaks in powerful ways to the collective experience of racially-tinged political and economic marginalization of urban working-class youth in the United States (Kelley, 1996; Alim & Pennycook, 2007).

Narrative and Storytelling in Hip Hop

Many African-American communities – a major cultural influence on hip hop – have strong ties to a rich ‘oral culture’ (Smitherman, 1986; Edwards & Sienkewicz, 1990; Jones, 1991; Hecht et al, 2003) and a strong tradition of narrativizing everyday discourse as part of sense-making or explanatory rhetorical strategies (Smitherman, 2000). Drawing on this rich oral tradition of the African diaspora, hip hop artists frequently use rhymed narratives, which have been a core part of hip hop music since its inception, in their raps (Smitherman 1997; Chang, 2005; Alim, 2006). As such, narrative forms – often called ‘storytelling raps’ by hip hop enthusiasts – are foundational within the musical genre and constitutive of a core component of the subculture and art form (Rose, 1994). It is important to understand that storytelling is a complex, dynamic and multifaceted form within hip hop, as artists draw on literary narrative forms and create new poetic devices. In this way, the successful rapper, commonly called a master of ceremonies (MC), blends reality and fiction in order to maintain a balance between their position as ‘verbally gifted storyteller and cultural historian’ for the urban underclass (Smitherman, 1997, p. 4). In the discussion of personal finance in an online hip hop community analyzed in this article, we see participants narrativizing financial problems and using narrative discourse strategies to help frame the issue.

Identity and Language in Hip Hop Culture

The world-view of the ‘hip hop generation’ has been fundamentally defined by tremendous racial inequality in urban labor markets, in public educational systems, in housing markets and in enforcement attitudes of the criminal justice system towards young African and Latino Americans (Kitwana, 2005). Many working-class urban young people are skeptical and distrustful of dominant, mainstream institutions that perpetuate this inequality and instead affiliate with the alternative institutions and counter-cultures of hip hop. Such alienation with mainstream institutions is strong enough that Rose, considered by many to be the eminent scholar of hip hop studies, contends that rap artists are modern-day ‘prophets of rage’, a ‘large and significant element’ of which are ‘engaged in symbolic and ideological warfare with institutions and groups that symbolically, ideologically, and materially oppress African Americans’ (1994, pp. 99, 101-102). In this way, she notes, ‘rap music is a contemporary stage for the theater of the powerless’. The relationship, in this view, between youth who affiliate with hip hop culture and dominant cultural forms is entirely oppositional.

the language of hip hop is to an anti-language, as Halliday argued that it was a ‘metaphorical character that defines the anti- language’ and that ‘this metaphorical quality appears all the way up and down the [language] system’ (1976, p. 578). In examining the non-standard spelling conventions regularly used in hip hop, Olivo (2001) buttressed this argument, contending that the differences non-standard orthographic practices not found in African-American English or other dialects serve as evidence that the anti-language devices in hip hop language ‘function to create and sustain hip-hop culture as an “anti-society”’ (p. 67). While Smitherman and Olivo may overstate their case – the popularity of hip hop among white youth (Kitwana, 2005) certainly shows that hip hop is not a strict anti-language – hip hop culture (and hip hop identity) stands in opposition to many dominant American institutions and cultural forms. How, then, do design researchers, many of whom are culturally located well within said institutions and forms, appeal to the ever-growing number of youth affiliated with hip hop, a youth culture fixated on ‘authenticity’ in discourse (McLeod, 1999), without colonizing it?

Theoretical Orientation

Research trajectories in psychology, anthropology, linguistics, philosophy, literary studies, education and social theory have argued against the notion of identity in contemporary societies as a static, singular ‘core identity’, and instead argued for a notion of identity as fluid, multiple and dynamic – continuously reproduced by both discursive and extant-material social practices (e.g. Foucault, 1977, 1980; Bakhtin, 1981; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Butler, 1993; Hall & Du Gay, 1996; Gee, 1999). This view holds that people both perform their identity in different ways depending upon the social context and have their identity defined for them by the social norms, practices and discourses of a community. Identity, then, is in part positional (Holland et al, 1998), having to do with personal relationships, social status, and larger systems of power in communities or activity groups in which a person participates or belongs (Gee 1999, 2000). An individual will enact a distinct role or version of who they are, as well as have who they can be defined for them, in different social arenas – at work with workers, at home with family, at a church with co-worshippers, at a bar with their friends, etc. These different identities, however, are not always bound strictly by the social groups and activity, but are frequently overlapping, negotiated, contested and hybridized.

Methods

Context of Study: design-based research

This study is situated within a broader design-based research investigation (Brown, 1992; Collins, 1992). Design-based research, also known as design research or design experiments, is the practice of ‘engineering particular forms of learning and systematically studying those forms of learning’ in a given context (Cobb et al, 2003, p. 9). As a methodology, design research aims to better understand how to create productive ways of learning by examining the interaction of researcher interventions, which are often centered on computer-supported learning environments or curricula, with communities of learners in quasi-naturalistic settings like classrooms (Collins et al, 2004). While design-based research stands in contrast with psychological methods in part because it allows more active roles in the study to participants (Collins, 1992; Barab & Squire, 2004), its major focus is often on successfully implementing and evaluating a design that was chosen and planned by researchers prior to an engagement with the learning context. This approach has been criticized for ignoring the agency and identities of teachers and students (and others) who participate in the research (Olson, 2004; Engeström, 2008) in an effort to seek legitimization within the broader discourse of ‘scientifically valid’ educational research (Shavelson et al, 2003). Some scholars have called for new modes of design research that incorporate the local knowledges of participant groups (Barab et al, 2004; cf. Bell, 2004) and speak to their linguistic practices and cultures (Lee, 2003). In an effort to understand how to design learning environments that are relevant to working-class urban youth culture, this study examines the social practices and modes of interaction in one discussion about personal finance on an online hip hop discussion forum.

This study serves to inform my doctoral thesis, a design-based research project entitled ‘Rethinking “Hip Hop Tycoon”: social identity, youth culture and the design of games for learning’. This project probes two general questions: (a) how to design a game for learning financial and entrepreneurial literacies that speaks to the identities, social practices and cultures of marginalized urban middle-school youth; and (b) the efficacy of this identity-driven learning artifact in helping these working-class youth build the financial literacies necessary to navigate a segmented labor market in a recessional economy. The project seeks to leverage the entrepreneurial values of hip hop culture in a ‘mobile media’ game design to help working-class young people in a large urban Midwestern city develop their knowledge of finance and entrepreneurialism. To better align the learning environment and design processes with these young people’s culture, identities and practices, this project uses sociocultural design tools that have been drawn from other methodological approaches – critical design ethnography (Barab et al, 2004), focus groups (Merton & Kendall, 1946; Krueger & Casey, 2000), verbal think-aloud protocols (Ericsson & Simon, 1984); and knowledge assessment tasks (Chi & Koeske, 1983) – in order to better deal with the relationship between financial knowledge and cultural identity. As such, the design process is informed by two preliminary design investigations: a survey/focus-group study of the digital practices and game-play patterns of working-class urban youth (DeVane, 2008) and this study of talk about financial literacy in online hip hop forums.

Data Collection

this data, personal finance and business. The relative popularity of topical sub-forums can be surprising – the sub-forum for discussion of politics and society was the second most popular behind the one allocated for discussion of music, ostensibly the community’s primary shared interest.

The relevant forum thread for this interaction was active from August to December 2007. The data chosen for analysis represents four of the forty-three unique posts in the thread. ‘Trebred’, a pseudonym for a regular participant in the large online community, created a thread to seek assistance with what he perceived as his significant unpaid debt and attendant poor credit ratings. The data presented here includes both Trebred’s original post and a sub-thread about another poster who had difficulties similar to those of the thread author. The relevant posts of this sub-thread are encapsulated in one large post by ‘Souer’. She ‘quoted’, or includes with attribution, the entirety of other posts in her own, then included her own remarks underneath. Like many others, this sub-forum has identifiable social norms and a community of regulars who participate. Souer, unlike the other posters, was a regular participant in this sub-forum at the time the data was collected.

Data Analysis

Because I am examining how identity, status and affiliation function in this social interaction, I utilize the framework of ‘D/discourse analysis’, a ‘theory and method for studying how language gets recruited “on site” to enact specific social activities and social identities’ (Gee, 2005, p. 1; cf. Fairclough, 1995). The primary function of human language in this view is to support social interaction, to enact an identity within a given social group and to perform affiliation with a culture, institution or social group. In this way, Gee (2005) distinguishes between instances of communicative practices, or small ‘d’ discourses, and language used to perform ‘ways of being in the world’, or big ‘D’ Discourses. This understanding of language differs from ‘transmission models’ of human communication that view language as a transparent media, or ‘wrapper’, for decontextualized information (cf. Lasswell, 1948; Shannon & Weaver, 1949). Meaning in language, however, is situated in linguistic forms, social functions, modes of expression, cultural models and social activities. To better frame these situated, social meanings in my analysis, this data is organized around idea units (Chafe, 1979, 1980; Gee, 1986, 2005) or a chunk of language focused on sharing a somewhat small piece of information, as my base unit of analysis. These idea units, which are also called lines, have been organized into stanzas that center on a theme, function or perspective (Scollon & Scollon, 1981; Gee, 1991, 2005). When my analysis focuses on the textual devices that the authors are using to perform social work, I organize the text into stanzas to better represent situated meanings in social interactions.

Findings

Narrativizing a (Social) Problem

Literature in the learning sciences has emphasized the important role that representations of problems play in social problem solving and other joint activity. The ability to create useful representations of a problem space, for instance, characterizes the difference in expert and novice competency in solving physics problems (Chi et al, 1981). Similarly, the quality of a problem representation, and its constraints and affordances, has important effects on students’ discourse during collaborative problem solving (Bell, 1997; Suthers, 1999; Ploetzner et al, 1999). Studies of problem solving foreground and emphasize the importance of a well-structured representation in problem solutions and cognitive activity (Larkin & Simon, 1987; Kotovsky & Simon, 1990; Zhang, 1997). In this influential cognitive framework, the ability of people, either individually or collaboratively, to successfully engage with a problem is dependent foremost on the clarity and robustness of the problem representation.

If one considers the initial post of Trebred, the post that starts the discussion (excerpted below), from this perspective, Trebred’s post might be considered an odd way to request help with a bad financial situation. While it does a large amount of social work, it does not provide readers with a well-structured representation of the problem or much in the way of specific information about it. Instead, the text utilizes narrative devices in order to communicate to its audience a general impression of the problem and to convince them to care about it. In order to accomplish these ends, the author constantly evaluates the ‘facts’ of his condition. The text not only uses a range of evaluative devices – exaggeration, reproduction of phonology, repetition, etc. – to attempt to gain the readers’ sympathy by helping them feel what the author wants them to feel, but deploys other devices in a very structured way that move the reader from feelings of alarm and empathy for the author’s situation to a more concrete discussion of the specifics of his problem. As a result, two thematic sections emerge from the text – the first (reproduced below in stanza form) seeks to attract the community’s attention and emphasize the dire nature of the author’s predicament, while the latter starts guiding potential discussion of a solution.

Thread Post 1, Thematic Stanza 1: Trebred’s Urgent Problem

TI: I have horrible credit I OWE EVERYBODY, PROBABLY YOU!!! a For real.

b My credit is bad

c I havent checked my score in a while

d but it’s probably at the lowest possible number. e I have about $10,000 in debt

f minus my student loans. g You name it I got it ...

h car repo, payday loans, credit cards, family friends, apartments, utitility [sic] companies, cable companies ...

i I OWE EVERYBODY

phonologically expressive repetition of his catch phrase from the title in clause ‘i’ (‘I OWE EVERYBODY’) to return to the theme set out in the title. Throughout this thematic section, Trebred seeks to balance a sense of urgency in his text.

In the second thematic section of his post, the author tries to move toward a discussion of possible solutions to his problem without leaving behind the alarming nature of his predicament (employed in the first thematic section to gain his audience’s sympathy). Here, the author focuses on possible solutions while still reminding readers of his dire circumstances using less obvious means. Indicative of this shift are the comparatively fewer evaluators found within it than in the previous section. This section still evinces the author’s feelings about his situation, but it deploys new narrative devices alongside the previously prevalent intensifiers to accomplish that goal. Using comparators (Labov, 1972), another family of evaluators, as well as intensifiers, the writer seeks to remind the reader of the dire nature of the issue. Comparators juxtapose ‘events that did occur to those which did not occur’ (Labov, 1972, p. 381) in order to provide a framework for the audience to evaluate the importance of those events. Because event negation ‘expresses the defeat of an expectation that something would happen’ (Labov, 1972, pp. 380-381), comparators often take the form of negatives, which tell the reader what happened while simultaneously summoning alternative imaginings of what could have been.

The author’s use of evaluators within the second section of the text is prominent and strategic with regard to the message he wishes to convey, maintaining a sense of urgency while at the same time explicating the problem space and shaping solutions. The comparators used are future-oriented comparators (Toolan, 2001) that deal with future, hypothetical actions instead of events that have already occurred. Through their use, the author contrasts not what has happened with what has not but rather two possible events or courses of action. He positions the choice he favored against the one he opposes:

Thread Post 1, Thematic Stanza 2: Trebred’s More Specific Problem

j I got a pretty good job makin decent money k so I need to start payin this shit off. l Where do I start though.

m Collection Agencies want all this money n that I cant come up with with one big lump sum. o I dont want to file bankruptcy [sic] because

p that shit stays one [sic] your credit for what?? 7 years? q I figure I get to I can pay these muthafuckas off in about 2. r What should I do Financial Guru’s????

Clauses ‘j’, ‘k’ and ‘l’ serve as a transition from an emphasis on the severity of the problem found in the first thematic section to an examination of the specifics of the author’s problem in the second thematic section. The framing of the problem starts with clause ‘m’ in which the intensifier-quantifier ‘all’ is used to emphasize the large amount of money owed to collection agencies. In this way, the clause serves two functions: it informs the audience that there is a substantial dollar amount owed and it maintains the intensity of the former section. Likewise, the use of negation comparators in clause ‘n’ helps the author contrast what he can do with what he cannot do while maintaining an emphasis on the size of his debt. In clause ‘o’, this use of negative future-tense comparators continues as the author evaluates different solutions for his predicament. The author positions his desire to stay out of bankruptcy against the possibility that bankruptcy would cause more harm to his credit than his current outstanding debt. Clause ‘q’ marks the first time that the author contemplates the possibility that his debt might one day be retired, marking the first time the author uses a positive tone since the section transition in clauses ‘j’ and ‘k’. Described as an oft-used conversational ‘move’ in the Conversation Analysis literature, this optimistic projection is often used as an exit device in troubles talk, a form of conversation in which one participants’ problem is discussed (Jefferson, 1988), serving to encourage the reader to answer the author’s final request for help and advice in clause ‘r’. The audience is then left to decide whether or not they should try to aid the author.

rather a narrative presentation of a problem to a social group; thus, its structure differs from the archetypal narrative described by Labov (1972) and Labov & Waletzky (1967) while still containing recognizable narrative elements. Table I shows an analysis of the post based on Linde’s (1993) framework for narrative structural clause types.

Table I. Trebred’s narrative problem representation.

section. This structure places heavy emphasis on the author’s feelings about his problem around the boundaries of the telling, so to speak, without interrupting his report of the problem’s specifics with explicit evaluation. The evaluative interruptions are placed at the beginning of each section as the author orients (and reorients) his audience towards his problem and then at the end of the second section where the author evaluates potential outcomes and solutions. This embedding of evaluation maintains an emphasis on the author’s feelings – and thus his values – while allowing for a relatively smooth and engaging telling of the narrativized dilemma. In this way, he maintains an interesting and rhythmic reportability (i.e. the engaging happenings of the story) while presenting his values and sentiments, which he presumably hopes align with those of his audience (e.g. self-deprecation in lines a-d; use of hip hop vernacular in lines j-q, performance of limited financial expertise in lines o-p). Thus, the author does not just tell his story in a compelling fashion but also presents a certain version of himself in his narrative that aligns with the values of the community.

As one examines the text in increasing detail, it becomes more apparent that the text does a tremendous amount of social work for it to be considered a mere presentation of a problem. The presence of socially-oriented narrative features – narrative structure, audience-aimed evaluation, balance of reportability and credibility, etc. – suggests that the text, while certainly not phatic (Malinowski, 1923), is an artifact whose design is intended to establish a social relationship between its audience and the author – certainly at least to the same degree that it is designed to present to them a problem to be solved. These narrative features, moreover, are mobilized in a unique manner as the author seeks to present not a conventional narrative but rather a personal problem in story-like form. This choice suggests that the author’s goal, however tacit, is to establish himself as within the Discourse of the sub-forum community; indeed, in some ways we could argue that this need to establish identity is perhaps more important than the need to accurately convey a bevy of detailed information about his financial problem. Trebred’s presentation of his problem and solicitation of advice are nuanced social interactions that are designed to parlay his entrance into a community. In this context the development of financial literacy here, it seems, is intricately bound up in the production of social identities.

Hybrid Identity in Text

Trebred’s request for help spawns several discussions of credit-related financial problems and concomitant debates about possible solutions in the thread. Just as Trebred’s post illuminates that the how narrative can function as a social connector in collaborative problem solving, the discussion that followed his plea for help demonstrates how identity, collaboration and culture interact in the financial literacy practices of this hip hop community. After Trebred presented his case to the community, ‘EndlezFlowz’, a pseudonym for another forum participant, takes advantage of the opening presented by Trebred to present his own credit and debt problems, inquiring as to the credit score he would need to buy a home:

Thread Post 37 Excerpt: EndlezFlowz’ Problem

15 few ... In the next three yrs I wanna buy a crib. I was

16 about to call ccrs but i decided not to. How high would my 17 score need to be to get a home?

Thread Post 38 Excerpt: Naledje’s Advice

1 You have to have an average score of at least 620, even 2 with that, I would get it higher, so you don’t pay an

3 outrageous intrest [sic] rate. Pay off them bills get some secured 4 credit cards homey, you got time.

At no time in his 40-word declarative response does Naledje use any overt narrative or conversational devices to attempt to convey his authority or expertise in the subject matter – he does not, for example, explain the rationale behind his advice. He does, however, use non-overt devices for asserting authority within his text. For example, the terseness of the prose and the lack of any explanatory justifications can be construed as a projection of confidence, while deontic modals – expressions that convey requirement or necessity on the part of a speaker – like ‘have to’ (line 1) are used to convey authority in casual conversations (Palmer, 2003). Naledje only explicitly attempts to establish solidarity with EndlezFlowz one time, when he refers to EndlezFlowz as ‘homey’ (line 4). Instead, he uses the social language of hip hop – exhibited in the hip hop slang and tense markers of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) in his text – to establish himself as someone who is ‘speaking within’ the discourse. These AAVE markers include Naledje’s use of a demonstrative them (Mufwene, 1998) when he refers to ‘them bills’ (line 3) and substituted ‘got’ for ‘have’ (Weldon, 1994). While he does not show great interest in building a relationship with this newcomer to his community, Naledje does take the time to explicitly acknowledge EndlezFlowz as a peer and to make at least a small bid at establishing some minimal solidarity. In such ways, the design of the text presents the identity of the author as reserved and confident, yet knowledgeable and casually interested in helping others in the community.

Of course, the way in which a person performs and displays their identity within a given community through language – in ways that are recognizable by their fellow members –is never straightforward and uncomplicated. Naledje’s manner of performing identity and establishing one’s relationship to the community greatly contrasts with that chosen by Souer, a subsequent respondent. Compared to Naledje, Souer’s text seems to defy simple analysis. In her 214 word rejoinder to Naledje’s response, she negotiates a tension between elevating her status within the community through a display of expertise in financial matters and building solidarity with the community. She employs a range of conversational and communicative devices in order to accomplish this, sophisticated at times and seemingly rudimentary at others.

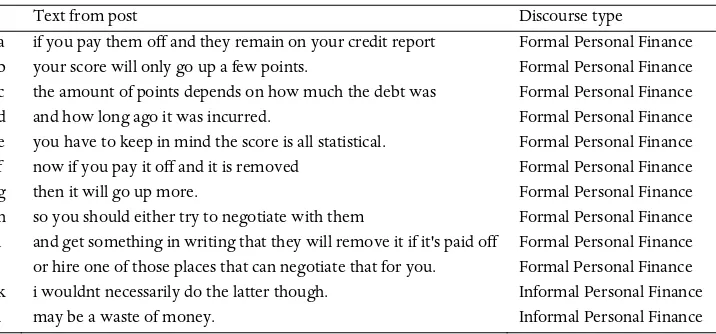

Text from post Discourse type

a if you pay them off and they remain on your credit report Formal Personal Finance b your score will only go up a few points. Formal Personal Finance c the amount of points depends on how much the debt was Formal Personal Finance d and how long ago it was incurred. Formal Personal Finance e you have to keep in mind the score is all statistical. Formal Personal Finance f now if you pay it off and it is removed Formal Personal Finance g then it will go up more. Formal Personal Finance h so you should either try to negotiate with them Formal Personal Finance i and get something in writing that they will remove it if it's paid off Formal Personal Finance j or hire one of those places that can negotiate that for you. Formal Personal Finance k i wouldnt necessarily do the latter though. Informal Personal Finance l may be a waste of money. Informal Personal Finance

Table II. Souer’s specialist first section.

text’s tendency toward the social language of Standard English is apparent through the lack of auxiliary verb omissions, a common feature of African-American English, as well as the shortage of contractions, indicating formality. One plausible reason for the lack of auxiliary omission is that Souer used many deontic modals (expressions that imply requirement or necessity on the speaker’s part) to convey her authority and impose obligation on the author. The presence of so many uncontracted auxiliaries (‘will’ in line b, ‘have to’ in line e, ‘should’ in line h, etc.) conveys formality. Words like ‘incurred’, ‘statistical’ and ‘negotiate’ all perform an expertise in matters of finance generally and credit specifically. Toward the end of the paragraph, Souer begins to use contractions, thereby transitioning towards a more casual tone, with the last sentence seemingly so casually composed that it omits the subject. This change in inflection from formality to informality indicates that Souer is preparing the reader for a tonal shift in the next paragraph.

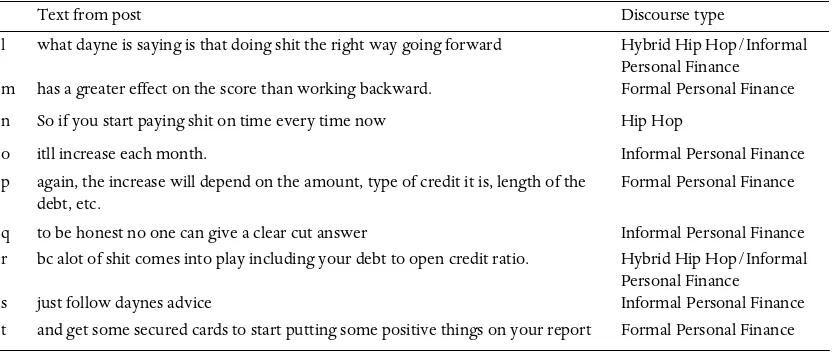

Text from post Discourse type

l what dayne is saying is that doing shit the right way going forward Hybrid Hip Hop/Informal Personal Finance

m has a greater effect on the score than working backward. Formal Personal Finance

n So if you start paying shit on time every time now Hip Hop

o itll increase each month. Informal Personal Finance p again, the increase will depend on the amount, type of credit it is, length of the

debt, etc.

Formal Personal Finance

q to be honest no one can give a clear cut answer Informal Personal Finance r bc alot of shit comes into play including your debt to open credit ratio. Hybrid Hip Hop/Informal

Personal Finance s just follow daynes advice Informal Personal Finance t and get some secured cards to start putting some positive things on your report Formal Personal Finance

Table III. Souer’s hybrid second section.

If the language of the first paragraph indicates that Souer is seeking to establish her expertise and authority in the discourse of finance, the very first sentence of the next paragraph shows that Souer has a different purpose for this subsequent section (see Table III). She continues to build her credibility in the subject area but her language is significantly altered to establish her affiliation with the discourse of the community:

Thread Post 42: Souer (second section excerpt by stanza)

l what dayne is saying is that doing shit the right way going forward m has a greater effect on the score than working backward.

Souer still occupies the discursive space of expertise and authority in this part of the text but now has clearly broadened her authorial voice, abandoning the specialist language of the first paragraph and using profanity in this section to establish herself as speaking within the oppositional social language of hip hop. Her use of profanity escalates through the final paragraph of her post:

Thread Post 42: Souer (second section excerpt by stanza)

n so if you start paying shit on time every time now o itll increase each month.

p again, the increase will depend on the amount, type of credit it is, length of the debt, etc. q to be honest no one can give a clear cut answer

r bc alot of shit comes into play including your debt to open credit ratio. s just follow daynes advice

t and get some secured cards to start putting some positive things on your report.

‘anti-language’. Smitherman (1997) notes that, depending upon the context, vulgarities like ‘muthafucka’ and ‘shit’ in the social language of hip hop are routinely used in place of pronouns as neutral, ‘filler’ words in order to distinguish the language of hip hop from that of the dominant culture. While the exact tone – neutral or negative – of Souer’s profanity-in-place-of-a-pronoun is ambiguous, what is clear is that she is using them to realign her language with the discourse of hip hop. In doing so, she modifies the social language or register in which she is writing to compensate for the tensions between her main ideational goal, the subject matter being discussed (in this case, finance and credit scores) and her interpersonal goal, maintenance of her relationships with the people in a conversation (in this case, affiliation with hip hop culture), in her language.

Souer also does overt social work to establish relationships with others in the community throughout this balancing act between affiliation with hip hop culture and recognition as an expert in financial literacy. In her second paragraph, she clarifies Naledje’s advice that Trebred simply ‘pay them bills’ (line 3) in order to achieve a higher credit score. At this juncture, Souer could attempt to gain status in the community by criticizing Naledje, whose advice does seem a bit glib, as lacking any depth of understanding of credit scores and thereby juxtaposing her own expertise with his. However, Souer responds in a very different way: She reframes her detailed correction of Naledje’s suggestions as an exposition of what he actually said. In this way, Souer avoids a face-threatening encounter (Brown & Levinson, 1987; Goffman, [1967] 2005) – a social event in which a person loses status in a group – with Naledje by using the conversation technique of revoicing to engage in avoidance face-work. Rather than trying to achieve status within the community by criticizing another’s advice on the subject, however, Souer actively builds her relationships in the community by aligning prior contributions to her own.

Souer’s text is explained by its relationship to the overlapping Discourses of the forum community. The community has values aligned with both the Discourse of financial literacy as well as the Discourse of hip hop culture. While the case has been made convincingly that hip hop culture highly values financial and entrepreneurial literacy through its emphasis on what has been variously called ‘bootstrap capitalism’ (Basu & Werbner, 2001) or ‘expressive entrepreneurship’ (Fernández-Kelly & Konzcal, 2005), the Discourse of hip hop lacks a well-developed language for talking about finance in general and credit specifically. Souer, therefore, adopts a specialist social language of finance (see Gee, 2004) – one that is tied through mainstream social institutions to domain-specific knowledge – in order to be able to talk about matters of finance and credit. This is consistent with research that holds that social frames of interaction – ways of engaging in social exchange – are tied to cognitive knowledge schemas (Tannen & Wallat, 1987), or ways of thinking about and setting expectations for what happens in the world. Souer’s writing shifts throughout her post as she attempts to fuse the language of finance with the language of hip hop. The result is that her writing – her written voice – is thoroughly heteroglossic (Bahktin, 1981), displaying the simultaneous existence of different social languages and their attendant values and assumptions within one text. Souer’s language is indeed hybrid –built of multiple, variant discourses that are, at times, even in conflict.

Discussion and Implications

communities as part of a design research project of a financial literacy game for learning. This project seeks to draw (in respectful, authentic ways) on the finance-oriented values and practices of hip hop culture in order to design a game-based learning environment that helps working-class youth learn twenty-first-century economic skills. This study’s analysis suggests that the hybridization of: (a) personal narratives with collaborative problem solving, and (b) the cultural-political values of hip hop’s communicative practices with specialist financial language, play productive roles in the dissemination of financial knowledge in hip hop communities.

In this study, we saw how narrative framings of problems that align with storytelling traditions in hip hop can motivate intense collaborative problem-solving and learning activities in an online hip hop community. In general accordance with communicative practices in African-American English and specific alignment with foundational language norms in hip hop, Trebred uses sophisticated narrative devices to frame his financial problem and to address a social one – how to get a community in which he is a peripheral participant to engage with his personal financial problem. In part because of Trebred’s clever use of humor and evaluative narrative devices, community members like EndlezFlowz, Naledje, Souer and others identify with his situation and engage with his problem substantively even though they will receive no remuneration or reward. The hybridization of problem representations with narrative forms – a common practice in hip hop music (Smitherman, 1997) – is an approach to connecting with audiences to which designers of learning environments and games should give serious consideration as we design new activity scaffolds and participant structures.

The hybrid nature of identities, Discourse and communicative practices in the interaction are evinced in the complicated but helpful advice to thread respondents in credit debt. Through their lexical and syntactic choices, participants in the interaction display membership and affiliation with the Discourse of hip hop – a Discourse which many contend is an anti-language of political resistance. While it is true that hip hop culture is often a site of resistance to alienating and marginalizing social forces, performances of identity similar to Souer’s post challenge the notion that hip hop culture is, in its essence, thoroughly oppositional (Rose, 1994; Smitherman, 1997). The hybridity in Souer’s textual presentation of herself – as a member of both the Discourse of hip hop as well as the Discourse of finance – emphasize the role of online hip hop communities as places where an organic bridging of different Discourses takes place. Researchers who study learning and culture have contended that this kind of boundary space between Discourses is a powerful site for marginalized youth to learn and produce knowledge. This hybrid discursive space – variously labeled a borderlands Discourse (Gee, 1999), a third space (Gutiérrez et al, 1999; Leander, 2002; Moje et al, 2004), a heteroglossic classroom (Kamberelis, 2001), or culturally responsive pedagogy (Lee, 1995) – is a discursive ‘space of regulated confrontation’ (Bourdieu, 1991b) that allows a person belonging to two conflicting Discourses to use her/his knowledge in one Discourse to facilitate a rise in status in another. Gee (1999, 2004) argues that marginalized students often create these borderlands Discourses to facilitate their transition through the economic-gatekeeping institutions of schools while maintaining fidelity to their peer- or community-based primary Discourses. We see one such borderlands Discourse present in this interaction: Souer occupies a bridging discursive space that allows her to practice the financial skills, language and dispositions that she needs in a neoliberal monetarist economy while maintaining her affiliation with the youth culture of hip hop. Her hybrid communicative practices point to the efficacy of language in producing new discursive spaces at the boundaries of existing ones.

presents designers with an example of how to use cultural forms and culturally-based communicative practices to create authentic and compelling third spaces. In my own research, users playing early prototypes of Hip Hop Tycoon found dialogues with game characters to be inauthentic and uninteresting. Later iterations that featured character-dependent dialogues with regional- and period-based hip hop ‘dialects’ alongside more specialist financial language won far more praise from users. While such results are indeed preliminary, investigation of the effects of integration of culturally-based communicative practices and modes of interaction into learning environments would help to align design practices with basic research on naturally-occurring learning practices.

At a time when young people need working knowledge of financial skills and language, concerned scholars of learning and designers of learning tools would do well to look towards the powerful financial literacies and informal pedagogies that emerge in naturalistic youth culture communities. Such a focus on ‘everyday’ collaborative practices involved in successful financial learning will better inform the design of financial education learning environments. Moreover, it is incumbent upon learning environment researchers to look outwards toward a world full of culturally-rich learning practices in order to better understand ‘what works’ (Brown, 1992; Barab & Squire, 2004) for our designs. The compelling cultural practices of youth – modes of interaction, habits of mind, participant structures, and ways of being in the world – drive a world full of practical innovation and creativity. Why should we not borrow from, and orient our designs toward, these thriving figure worlds of youth culture?

References

Alim, H.S. (2002) Street-Conscious Copula Variation in the Hip Hop Nation, American Speech, 77, 288-304.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/00031283-77-3-288

Alim, H. (2003) On Some Serious Next Millennium Rap Ishhh: Pharoahe Monch, hip hop poetics, and the internal rhymes of internal affairs, Journal of English Linguistics, 31(1), 60.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0075424202250619

Alim, H.S. (2006) Roc the Mic Right: the language of hip hop culture. New York: Routledge.

Alim, H.S. & Pennycook, A. (2007) Glocal Linguistic Flows: hip-hop culture(s), identities, and the politics of language education, Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 6(2), 89-100.

Alridge, D. (2005) From Civil Rights to Hip Hop: toward a nexus of ideas, Journal of African American History, 90(3), 226.

Bakhtin, M. (1981) The Dialogic Imagination: four essays, trans. M. Holquist & C. Emerson. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Barab, S. & Squire, K. (2004) Design-Based Research: putting a stake in the ground, Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 1-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1301_1

Barab, S., Thomas, M., Dodge, T., Squire, K. & Newell, M. (2004) Critical Design Ethnography: designing for change, Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 35(2), 254-268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/aeq.2004.35.2.254

Basu, D. & Werbner, P. (2001) Bootstrap Capitalism and the Culture Industries: a critique of invidious comparisons in the study of ethnic entrepreneurship, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 24(2), 236-262.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870020023436

Bell, P. (1997) Using Argument Representations to Make Thinking Visible for Individuals and Groups, in Proceedings of the 2nd International Computer Supported Collaborative Learning Conference, vol. 97, 10-19. Bell, P. (2004) On the Theoretical Breadth of Design-Based Research in Education, Educational Psychologist,

39(4), 243-253. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3904_6

Bourdieu, P. (1977) Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1991a) Language and Symbolic Power, ed. J. Thompson, trans. G. Raymond & M. Adamson. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1991b) Epilogue: on the possibility of a field of world sociology, in P. Bourdieu & J. Coleman (Eds) Social Theory for a Changing Society, 373-388. Boulder: Westview Press.

Brake, M. (1980) The Sociology of Youth Culture and Youth Subcultures. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Brown, A. (1992) Design Experiments: theoretical and methodological challenges in creating complex

interventions in classroom settings, Journal of the Learning Sciences, 2(2), 141-178.

Brown, A. & Campione, J. (1990) Communities of Learning and Thinking: or a context by any other name, Contributions to Human Development, 21, 108-126.

Brown, J.S., Collins, A. & Duguid, P. (1989) Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning, Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32-42.

Brown, P. & Levinson, S. (1987) Politeness: some universals in language usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Butler, J. (1993) Bodies that Matter. New York: Routledge.

Caro, R. (1975) The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the fall of New York. New York: Vintage Books. Chafe, W. (1979) The Flow of Thought and the Flow of Language, Syntax and Semantics, 12, 159-182. Chafe, W. (1980) The Deployment of Consciousness in the Production of a Narrative, The Pear Stories:

Cognitive, Cultural and Linguistic Aspects of Narrative Production, 3, 9-50.

Chang, J. (2005) Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: a history of the hip hop generation. New York: St Martin’s Press. Chi, M. & Koeske, R. (1983) Network Representation of a Child’s Dinosaur Knowledge, Developmental

Psychology, 19(1), 29-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.19.1.29

Chi, M., Feltovich, P. & Glaser, R. (1981) Categorization and Representation of Physics Problems by Experts and Novices, Cognitive Science, 5(2), 121-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog0502_2

Cobb, P., Confrey, J., diSessa, A., Lehrer, R. & Schauble, L. (2003) Design Experiments in Educational Research, Educational Researcher, 32(1), 9. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032001009

Collins, A. (1992) Toward a Design Science of Education, in E. Scanlon & T. O’Shea (Eds) New Directions in Educational Technology, 15-22. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Collins, A., Joseph, D. & Bielaczyc, K. (2004) Design Research: theoretical and methodological issues, Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 15-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1301_2

DeVane, B. (2008) Looking Past the Digital Divide: the digital literacies and videogame practices of low-income youth. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. New York.

Edwards, V. & Sienkewicz, T. (1990) Oral Cultures Past and Present: rappin’ and Homer. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Engeström, Y. (2008) From Design Experiments to Formative Interventions. Keynote, in Proceedings of the International Conference of the Learning Sciences 2008, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Ericsson, K. & Simon, H. (1984) Protocol Analysis: verbal reports as data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Fairclough, N. (1995) Critical Discourse Analysis: the critical study of language. Harlow: Longman.

Fernández-Kelly, P. & Konczal, L. (2005) ‘Murdering the Alphabet’. Identity and Entrepreneurship among Second-Generation Cubans, West Indians, and Central Americans, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28(6), 1153-1181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870500224513

Foucault, M. (1977) Discipline and Punish: the birth of the prison, trans. A. Sheridan. New York: Pantheon. Foucault, M. (1980) The History of Sexuality, Volume I: An Introduction. New York: Vintage Books. Gee, J.P. (1986) Units in the Production of Discourse, Discourse Processes, 9(4), 391-422.

Gee, J.P. (1991) A Linguistic Approach to Narrative, Journal of Narrative and Life History, 1(1), 15-39. Gee, J. (1999) Social Linguistics and Literacies: Ideology in Discourses, 2nd edn. New York: Taylor & Francis. Gee, J.P. (2000) Identity as an Analytic Lens for Research in Education, Review of Research in Education, 25,

99-125.

Gee, J.P. (2003) What Video Games have to Teach Us about Learning and Literacy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Gee, J.P. (2004) Situated Language and Learning: a critique of traditional schooling. New York: Routledge.

Gee, J.P. (2005) An introduction to discourse analysis: theory and method, 2nd edn. New York: Routledge. Goffman, E. ([1967] 2005) Interaction Ritual: essays in face to face behavior. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction. Guins, R. (2007) Hip-Hop 2.0, in A. Everett (Ed.) Learning Race and Ethnicity: youth and digital media. The

John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning, 63-80. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gumperz, J. (1982a) Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gumperz, J. (1982b) Language and Social Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gutiérrez, K., Baquedano-Lopez, P. & Tejeda, C. (1999) Rethinking Diversity: hybridity and hybrid language practices in the third space, Mind, Culture, and Activity, 6(4), 286-303.

Hall, S. & Du Gay, P. (1996) Questions of Cultural Identity. London: Sage.

Hall, S. & Jefferson, T. (1976) Resistance through Rituals: youth subcultures in post-war Britain. London: Hutchinson.

Halliday, M. ([1973] 2004) An Introduction to Functional Grammar, 3rd edn. London: E. Arnold. Halliday, M. (1976) Anti-languages, American Anthropologist, 78(3), 570-584.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/aa.1976.78.3.02a00050

Hebdige, D. (1979) Subculture: the meaning of style. London: Routledge.

Hecht, M., Jackson, R. & Ribeau, S. (2003) African American Communication: exploring identity and culture. Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Holland, D., Lachicotte, W., Skinner, D. & Cain, C. (1998) Identity and Agency in Cultural Worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hutchins, E. (1995) Cognition in the Wild. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jefferson, G. (1988) On the Sequential Organization of Troubles – talk in ordinary conversation, Social Problems, 35(4), 418-441. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/sp.1988.35.4.03a00070

Jones, G. (1991) Liberating Voices: oral tradition in African American literature. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Jonnes, J. (2002) South Bronx Rising: the rise, fall, and resurrection of an American city. New York: Fordham University Press.

Kamberelis, G. (2001) Producing of Heteroglossic Classroom (Micro) Cultures through Hybrid Discourse Practice, Linguistics and Education, 12(1), 85-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0898-5898(00)00044-9

Kelley, R. (1996) Kickin Reality, Kickin Ballistics: gangsta rap and postindustrial Los Angeles, in W. Perkins (Ed.) Droppin Science: critical essays on rap music and hip hop culture, 117-158. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Kitwana, B. (2002) The Hip Hop Generation: young blacks and the crisis in African American culture. New York: Basic Civitas Books.

Kitwana, B. (2005) Why White Kids Love Hip Hop: wankstas, wiggers, wannabes, and the new reality of race in America. New York: Basic Civitas Books.

Kotovsky, K. & Simon, H. (1990) What Makes Some Problems Really Hard: explorations in the problem space of difficulty, Cognitive Psychology, 22(2), 143-183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(90)90014-U

Krueger, R. & Casey, M. (2000) Focus Groups: a practical guide for applied research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Labov, W. (1972) Language in the Inner City: studies in the black English vernacular. Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press.

Labov, W. & Waletzky, J. (1967) Narrative Analysis: oral versions of personal experience, in C. Helm (Ed.) Essays on the Verbal and Visual Arts, 12-44. Seattle: University of Washington.

Lankshear, C. & Knobel, M. (2006) New Literacies: everyday practices and classroom learning. Buckingham and Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Larkin, J. & Simon, H. (1987) Why a Diagram is (Sometimes) Worth Ten Thousand Words, Cognitive Science, 11(1), 65-100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0364-0213(87)80026-5

Lasswell, H. (1948) The Structure and Function of Communication in Society, The Communication of Ideas, 37-51.

Lave, J. (1988) Cognition in Practice: mind, mathematics and culture in everyday life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991) Situated Learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leander, K. (2002) Polycontextual Construction Zones: mapping the expansion of schooled space and identity, Mind, Culture, and Activity, 9(3), 211-237. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327884MCA0903_04

Leander, K. & Frank, A. (2006) The Aesthetic Production and Distribution of Image/Subjects among Online Youth, E-Learning, 3(2), 185-206.

Lee, C. (1995) A Culturally Based Cognitive Apprenticeship: teaching African American high school students skills in literary interpretation, Reading Research Quarterly, 30(4), 608-630.

Lee, C.D. (2003) Toward a Framework for Culturally Responsive Design in Multimedia Computer Environments: cultural modeling as a case, Mind, Culture, and Activity, 10(1), 42-61.

Linde, C. (1993) Life Stories. New York: Oxford University Press.

Malinowski, B. (1923) The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Languages, in C. Ogden & I. Richards (Eds) The Meaning of Meaning, 196-336. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

McLeod, K. (1999) Authenticity within Hip-hop and Other Cultures Threatened with Assimilation, Journal of Communication, 49(4), 134-150.

Merton, R.K. & Kendall, P.L. (1946) The Focused Interview, American Journal of Sociology, 51(6), 541.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/219886

Moje, E., Ciechanowski, K., Kramer, K., Ellis, L., Carrillo, R. & Collazo, T. (2004) Working toward Third Space in Content Area Literacy: an examination of everyday funds of knowledge and discourse, Reading Research Quarterly, 39(1), 38-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.39.1.4

Mufwene, S. (1998) African-American English: structure, history, and use. London: Routledge.

Muhammad, T. (1999) Hip-Hop Moguls: beyond the hype. As rap music has exploded, so have the fortunes of its young executives, Black Enterprise, 30, 78-92.

Olivo, W. (2001) Phat Lines: spelling conventions in rap music, Written Language & Literacy, 4, 67-85.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1075/wll.4.1.05oli

Olson, D. (2004) The Triumph of Hope over Experience in the Search for ‘What Works’: a response to Slavin, Educational Researcher, 33(1), 24. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033001024

Palmer, F. (2003) Modality in English: theoretical, descriptive and typological issues, in R. Facchinetti, M. Krug, & F. Palmer (Eds) Modality in Contemporary English, 1-20. New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Perry, I. (2004) Prophets of the Hood: politics and poetics in hip hop. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Ploetzner, R., Fehse, E., Kneser, C. & Spada, H. (1999) Learning to Relate Qualitative and Quantitative

Problem Representations in a Model-Based Setting for Collaborative Problem Solving, Journal of the Learning Sciences, 8(2), 177-214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0802_1

Resnick, L. (1987) Learning in School and Out, Educational Researcher, 16(9), 13-20.

Rose, T. (1994) Black Noise: rap music and black culture in contemporary America. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press.

Sandoval, W. & Bell, P. (2004) Design-Based Research Methods for Studying Learning in Context: Introduction, Educational Psychologist, 39(4), 199-201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3904_1

Scollon, R. & Scollon, S. (1981) Narrative, Literacy and Face in Inter-ethnic Communication. Norwood: Ablex. Shannon, C. & Weaver, W. (1949) The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana, IL: University of

Illinois Press.

Shavelson, R., Phillips, D., Towne, L. & Feuer, M. (2003) On the Science of Education Design Studies, Educational Researcher, 32(1), 25. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032001025

Smitherman, G. (1986) Talkin and Testifyin: the language of Black America. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Smitherman, G. (1997) ‘The Chain Remain the Same’: communicative practices in the hip hop nation, Journal of Black Studies, 28, 3-25.

Smitherman, G. (2000) Talkin that Talk: language, culture, and education in African America. London: Routledge. Squire, K. & Steinkuehler, C. (2005) Meet the Gamers: they research, teach, learn, and collaborate. So Far,

without Libraries, Library Journal, 130(7), 4.

Steinkuehler, C. (2006) Massively Multiplayer Online Gaming as Participation in a Discourse, Mind, Culture, and Activity, 13(1), 38-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327884mca1301_4

Straw, W. (1991) Systems of Articulation, Logics of Change: communities and scenes in popular music, Cultural Studies, 5(3), 368. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09502389100490311

Suthers, D.D. (1999) Effects of Alternate Representations of Evidential Relations on Collaborative Learning Discourse, in Proceedings of the 3rd International Computer Supported Collaborative LearningConference, Palo Alto, CA: International Society of the Learning Sciences.

Tannen, D. & Wallat, C. (1993) Interactive Frames and Knowledge Schemas in Interaction: examples from a medical examination/interview, Framing in Discourse, 57-76.

Thomas, D. & Brown, J. (2007) The Play of Imagination: extending the literary mind, Games and Culture, 2(2), 149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1555412007299458

Wallace, D. & Wallace, R. (1999) A Plague on Your Houses: how New York was burned down and national public health crumbled. London: Verso.

Weldon, T. (1994) Variability in Negation in African American Vernacular English, Language Variation and Change, 6(3), 359-397. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954394500001721

Wenger, E. (1999) Communities of Practice: learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zhang, J. (1997) The Nature of External Representations in Problem Solving, Cognitive Science, 21(2), 179-217.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog2102_3