Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:25

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Exploring the Value of MBA Degrees: Students’

Experiences in Full-Time, Part-Time, and Executive

MBA Programs

Grady D. Bruce

To cite this article: Grady D. Bruce (2009) Exploring the Value of MBA Degrees: Students’ Experiences in Full-Time, Part-Time, and Executive MBA Programs, Journal of Education for Business, 85:1, 38-44, DOI: 10.1080/08832320903217648

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320903217648

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 201

View related articles

JOURNAL OF EDUCATION FOR BUSINESS, 85: 38–44, 2010 CopyrightC Heldref Publications

ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832320903217648

Exploring the Value of MBA Degrees: Students’

Experiences in Full-Time, Part-Time, and Executive

MBA Programs

Grady D. Bruce

California State University, Fullerton, Fullerton, California, USA

Critics of the overall value of the MBA have not systematically considered the attitudes of MBA students about the value of their degree. The author used data from a large sample of graduates (N=16,268) to do so, and to explore predictors of overall degree value. The author developed separate regression models for full-time, part-time, and executive MBA programs. The predictor variables are multi-item scales that measure (a) satisfaction with the MBA degree, and (b) satisfaction with the school or program. Each scale contributes significantly to the prediction of overall value, and there is little difference in their relative importance in the regression models.

Keywords: MBA, MBA satisfaction, MBA value, Outcomes assessment, Part-time MBA programs

Zhao, Truell, Alexander, and Hill (2006) documented nega-tive rumblings about the MBA that have emerged in business journals and magazines. Chief among these are Pfeffer and Fong’s (2002) and Mintzberg’s (2004) criticisms. Pfeffer and Fong questioned the relevance of the educational product of business schools and asserted, “There is little evidence that mastery of the knowledge acquired in business schools en-hances people’s careers, or that even attaining the MBA cre-dential itself has much effect on graduates’ salaries or career attainment” (p. 80). Mintzberg said that, “MBA programs are specialized training in the functions of business, not general education in the practice of managing” (p. 5).

Bennis and O’Toole (2005) pointed to problems resulting from business schools’ measuring themselves on the rigor of scientific research produced by faculty “instead of measuring themselves in terms of the competence of their graduates. . .“ (p. 98). As a result, “. . .MBA programs face intense criticism for failing to impart useful skills, failing to prepare leaders, failing to instill norms of ethical behavior, and even failing to lead graduates to good corporate jobs” (p. 96).

Because criticisms generally focus on the relevance of MBA programs to the practice of management, it is important to ask what schools are doing. Some schools have

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Grady Bruce, 255 N. El Cielo, Suite 140–225, Palm Springs, CA 92262-6974, USA. E-mail: gbruce@fullerton.edu

responded with program reviews and curriculum changes (Ewers, 2005). Rubin and Dierdorff’s (2007) study of 373 schools explored curriculum criticisms and concluded, “the majority of business school curricula adequately cover key managerial competency requirements,” but the “competen-cies indicated by managers to be most critical (i.e., manag-ing human capital and managmanag-ing strategy/innovation) are the very competencies least represented in MBA curricula” (p. 2). The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Busi-ness (AACSB) has not been silent during this period, having introduced in 2003 new Assurance of Learning standards that required direct measures of student learning in the context of established learning goals (Martell, 2007). However, a 2006 survey showed that 37% of MBA programs had not assessed any learning goals (Martell).

In regard to the effects of an MBA education on students’ careers, Inderrieden, Holtom, and Bies (2006) reported a positive effect on early career success in their longitudinal study comparing individuals who completed an MBA degree with similarly qualified individuals who chose not to pursue the degree. Zhao et al. (2006) reported positive career effects over the short and long term. Holtom and Inderrieden (2007) calculated a 12% annualized return on investment (ROI) for MBA graduates from top-10 schools and an even higher 18% ROI for those from schools not in the top 10, evidence that refutes Pfeffer and Fong’s (2002) claim that students need to graduate from a top-ranked school to benefit economically from an MBA.

VALUE OF MBA DEGREES 39

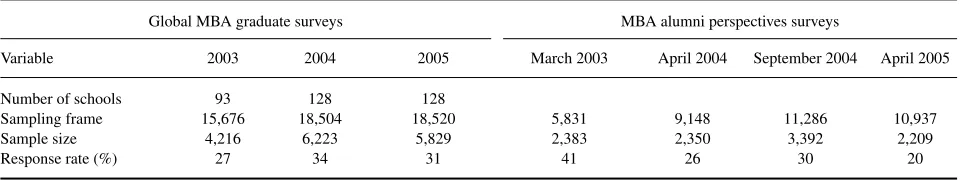

TABLE 1

Sample Sizes and Response Rates

Global MBA graduate surveys MBA alumni perspectives surveys

Variable 2003 2004 2005 March 2003 April 2004 September 2004 April 2005

Number of schools 93 128 128

Sampling frame 15,676 18,504 18,520 5,831 9,148 11,286 10,937

Sample size 4,216 6,223 5,829 2,383 2,350 3,392 2,209

Response rate (%) 27 34 31 41 26 30 20

Corporate recruiters responding to the annual surveys that the Graduate Management Admission Council (GMAC) con-ducts were asked to summarize their experiences during 2006 with new hires from MBA and other graduate business pro-grams (Murray, 2007). The majority—72%—indicated that their new hires met their expectations, 24% said they ex-ceeded expectations, whereas 4% said they did not meet expectations. In regard to managerial competencies, the re-cruiters indicated that MBAs show better knowledge of gen-eral business functions than their non-MBA peers and better behavioral competencies, such as managing strategy and in-novation and decision-making processes. MBAs are at the same level as their non-MBA peers in managing human cap-ital and in their interpersonal skills, a finding that may not be expected given the complaints of employers over the years about the interpersonal skills of new MBAs (Feldman, 2007). What is missing from these criticisms of the MBA and the research they have triggered is an evidence-based analysis of the attitudes of MBA students themselves. The present article offers that analysis by providing answers to four research questions as they relate to full-time, part-time, and executive MBA programs:

Research Question 1 (RQ1): How satisfied are students grad-uating from MBA programs with the potential benefits of their degree?

RQ2: How do students rate the schools or programs in which they are enrolled?

RQ3: How do students rate the value of the MBA?

RQ4: To what extent do MBA-degree satisfaction and school or program ratings predict the value of the MBA?

METHOD

I used data from annual online surveys of graduating students (Global MBA Graduate Surveys) that the GMAC conducted to answer these questions(Graduate Management Admission Council, 2003a; Graduate Management Admission Council, 2004a; Graduate Management Admission Council, 2005). GMAC invited its member schools and each school listed in the GMAC internal database to participate. Schools ei-ther supplied GMAC with a list of names and e-mail ad-dresses of students intending to graduate in the survey year

or agreed to forward survey invitations directly to students. GMAC used prenotification messages, reminders to non-respondents, and monetary incentives to increase response rates.

Participants

To answer the research questions, I aggregated responses of graduating students from Global MBA Graduate surveys con-ducted from 2003 through 2005(Graduate Management Ad-mission Council, 2003a; Graduate Management AdAd-mission Council, 2004a; Graduate Management Admission Council, 2005) into one sample (N=16,268). In all, 68% were male students and 32% were female students; 58% were aged 28–34; 78% were from schools located in the United States; and 60% were U.S. citizens. Table 1 shows the number of schools participating, sample sizes, and response rates.1

In discussing the results, reference is made to findings from four online alumni surveys that the GMAC conducted, the MBA Alumni Perspectives surveys (Graduate Manage-ment Admission Council, 2003b; Graduate ManageManage-ment Ad-mission Council, 2004b; Edgington & Schoenfeld, 2004b; Schoenfeld, 2005). Sample sizes and response rates for these surveys are also shown in Table 1. All respondents to MBA Alumni Perspectives surveys participated in one earlier Global MBA Graduate survey.

GMAC used a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 5 (extremely satisfied) to measure stu-dents’ satisfaction with the following randomly listed nine potential benefits of the MBA: (a) Preparation to get a good job in the business world; (b) an increase in career options; (c) credentials desired; (d) opportunity to improve person-ally; (e) opportunity for quicker advancement; (f) devel-opment of management knowledge or technical skills; (g) an increase in earning power; (h) opportunity to network and to form relationships with long-term value; and (i) job security.

GMAC used a different 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 5 (outstanding; with the option to selectnot applicable) to obtain ratings of the following randomly listed seven aspects of school or program quality: (a) admissions; (b) career services; (c) curriculum; (d) faculty; (e) program management (mission, standards, continuous improvement); (f) student services; and (g) fellow students.

40 G. D. BRUCE

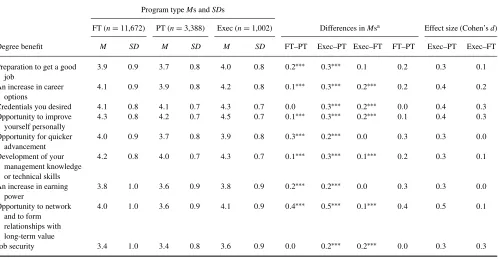

TABLE 2

Satisfaction With Potential Benefits of the MBA

Program typeMs andSDs

FT (n=11,672) PT (n=3,388) Exec (n=1,002) Differences inMsa Effect size (Cohen’sd)

Degree benefit M SD M SD M SD FT–PT Exec–PT Exec–FT FT–PT Exec–PT Exec–FT Preparation to get a good

job

3.9 0.9 3.7 0.8 4.0 0.8 0.2∗∗∗ 0.3∗∗∗ 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.1 An increase in career

options

4.1 0.9 3.9 0.8 4.2 0.8 0.1∗∗∗ 0.3∗∗∗ 0.2∗∗∗ 0.2 0.4 0.2 Credentials you desired 4.1 0.8 4.1 0.7 4.3 0.7 0.0 0.3∗∗∗ 0.2∗∗∗ 0.0 0.4 0.3 Opportunity to improve

yourself personally

4.3 0.8 4.2 0.7 4.5 0.7 0.1∗∗∗ 0.3∗∗∗ 0.2∗∗∗ 0.1 0.4 0.3 Opportunity for quicker

advancement

4.0 0.9 3.7 0.8 3.9 0.8 0.3∗∗∗ 0.2∗∗∗ 0.0 0.3 0.3 0.0 Development of your

management knowledge or technical skills

4.2 0.8 4.0 0.7 4.3 0.7 0.1∗∗∗ 0.3∗∗∗ 0.1∗∗∗ 0.2 0.3 0.1

An increase in earning power

3.8 1.0 3.6 0.9 3.8 0.9 0.2∗∗∗ 0.2∗∗∗ 0.0 0.3 0.3 0.0 Opportunity to network

and to form relationships with long-term value

4.0 1.0 3.6 0.9 4.1 0.9 0.4∗∗∗ 0.5∗∗∗ 0.1∗∗∗ 0.4 0.5 0.1

Job security 3.4 1.0 3.4 0.8 3.6 0.9 0.0 0.2∗∗∗ 0.2∗∗∗ 0.0 0.3 0.3 FT=full time; PT=part time; Exec=executive.

aDisplayed differences may differ by .1 from displayed means because of rounding. ∗∗∗p<.001.

GMAC measured the value of the MBA to students with the question, “When you compare the total monetary cost of your MBA (or equivalent degree) to the quality of education you received, how would you rate the overall value of your MBA (or equivalent) degree?”

RESULTS

Satisfaction or Dissatisfaction With MBA Degree

Table 2 reports mean satisfaction scores for potential MBA benefits among respondents in the three types of MBA pro-grams and differences among the propro-grams. I used the range from 3.5 to 4.4 to denotevery satisfied; students in full-time and part-time programs were very satisfied with eight of nine potential benefits (all but job security); and students in exec-utive programs were very satisfied with all nine. Significant differences between pairs of types of MBA programs in mean satisfaction scores were identified with asterisks in Table 2 (as well as other tables). I usedttests to evaluate statistical significance. Full-time programs differed significantly from part-time programs in mean satisfaction for seven of nine potential degree benefits, and in each case satisfaction was higher in full-time than in part-time programs. Executive pro-grams differed significantly from part-time propro-grams on all nine potential degree benefits; and in all cases, satisfaction was higher in executive programs than in part-time programs.

Executive programs differed significantly from full-time pro-grams on six of nine items; and in each case, satisfaction was higher in executive programs than in full-time programs. Because these evaluations of statistical significance were in-fluenced by sample size, I calculated Cohen’sdas a measure of effect size, using the pooled standard deviation (Rosenthal & Rosnow, 1991). In no comparison could the effect of MBA program type on degree satisfaction be considered large (Cohen, 1988).

Satisfaction or Dissatisfaction With the Quality of School or Program

Students rated three aspects of the school or program the highest, regardless of type of MBA program: faculty, fellow students, and curriculum (see Table 3). Students rated career services and student services as the lowest. Mean ratings were significantly higher in full-time than in part-time programs on all seven aspects; and in executive programs, on six of seven aspects. Mean ratings in executive programs were higher than those in full-time programs on three aspects. However, ex-amination of Cohen’sdshowed no large effects on ratings of school or program quality resulting from MBA program type.

Value of MBA Degree

Table 4 showed that the majority of students rated the over-all value of the MBA as outstanding or excellent, regardless of the type of MBA program in which they were enrolled.

TABLE 3

Satisfaction With School or Program

Program typeM(SD)

FT PT Exec Differences inMsa Effect size Cohen’sd

School or program n M SD n M SD n M SD FT—PT Exec—PT Exec–FT FT, PT Exec, PT Exec, FT

Admissions 11,584 3.6 1.0 3,332 3.3 .9 991 3.7 .9 0.3∗∗∗ 0.3∗∗∗ 0.1 0.3 0.4 0.1

Career services 11,415 2.9 1.2 2,648 2.7 1.1 717 2.8 1.2 0.2∗∗∗ 0.1 –0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1

Curriculum 11,640 3.7 .9 3,379 3.6 .8 998 3.9 .8 0.2∗∗∗ 0.4∗∗∗ 0.2∗∗∗ 0.2 0.5 0.3

Faculty 11,659 3.9 .9 3,380 3.7 .8 997 4.0 .8 0.2∗∗∗ 0.4∗∗∗ 0.1∗∗∗ 0.3 0.4 0.1

Program management 11,577 3.6 1.0 3,298 3.4 1.0 995 3.7 1.0 0.2∗∗∗ 0.3∗∗∗ 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.1

Student services 11,495 3.4 1.1 3,101 3.1 1.0 919 3.5 1.0 0.3∗∗∗ 0.4∗∗∗ 0.1 0.3 0.4 0.1

Fellow students 11,638 3.9 .9 3,378 3.6 .9 994 4.1 .9 0.3∗∗∗ 0.4∗∗∗ 0.1∗∗∗ 0.3 0.5 0.1

FT=full time; PT=part time; Exec=executive.

aDisplayed differences may differ by. 1 from displayed means because of rounding. ∗∗∗p<.001.

41

42 G. D. BRUCE

Outstanding (%) 32 17 24

Excellent (%) 33 36 40

Good (%) 24 32 26

Fair (%) 8 11 9

Poor (%) 3 3 2

M 3.8 3.5 3.8

SD 1.1 1.0 1.0

However, there were statistically significant differences in mean ratings between full-time and executive programs and part-time programs. Students in full-time programs rated overall value higher (n=11,672;M=3.8,SD=1.1) than those in part-time programs (n = 3,388;M = 3.5, SD =

1.0),t(15,058)=14.7,p <.001; and students in executive programs rated overall value higher (n =1,002;M =3.8,

SD =1.0) than those from part-time programs, t(4,388)=

5.9, p<.001. Students in full-time programs rated overall value outstanding at nearly twice the rate of those in part-time programs.

Predicting Value of the MBA

To answerRQ4, I conducted a regression analysis. I devel-oped two scales to measure satisfaction with the MBA degree and satisfaction with the school or program. These are the predictor variables in the regression analysis, with responses to the MBA value question as the criterion variable. Each scale aggregates responses to the following items of which it is composed: (a) nine items for the MBA degree scale, and (b) seven items for the school or program scale. Both scales were reliable. For the MBA degree scale, Cronbach’s alpha=.91; and for the school or program scale, Cronbach’s alpha=.88. Factor analysis showed each scale is one-dimensional. The items in each scale were moderately-to-strongly correlated with the total scale value. The bivariate correlation between the two scales was .70.

The rationale for using these two scales to predict the value of the MBA to students is rooted in research on the stages through which potential MBA students pass from the time they considered pursuing an MBA to the time they selected the school or program in which they enrolled (Schoenfeld & Bruce, 2005). That is, students first make a category-level de-cision (whether to pursue the degree) and then a brand-level decision (where to pursue the degree). From a marketing perspective, the consumer decision process is no different from that for any other product or service in which con-sumers make category-level and brand-level decisions. Se-lecting a graduate school to attend is a deliberative process for prospective students (Chapman & Niedermayer, 2001). Nicholls, Harris, Morgan, Clarke, and Sims (1995) discussed

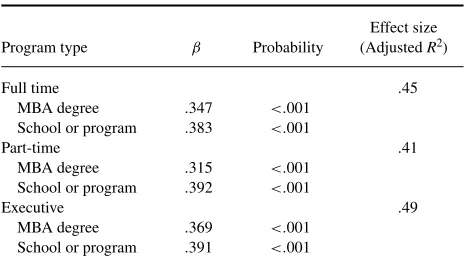

TABLE 5

Results of Multiple Regression Analyses

Program type β Probability

Effect size (AdjustedR2)

Full time .45

MBA degree .347 <.001 School or program .383 <.001

Part-time .41

MBA degree .315 <.001 School or program .392 <.001

Executive .49

MBA degree .369 <.001 School or program .391 <.001

this in marketing terms as an extended decision process in-volving complex buying behavior and high levels of involve-ment that result from expense (time and money), significant brand differences, and infrequent buying (Nicholls et al.). The ultimate decision to enroll in a specific school or pro-gram suggests that the student has come to the conclusion that the value of an MBA degree from a specific school or program is greater than its cost. With the importance of both category- and brand-level factors in the ultimate decision to enroll in a specific MBA program, the hypothesis implicit in askingRQ4was that both affect the overall value of the MBA at the time of graduation.

Table 5 reports the results of separate multiple regres-sion analyses that I conducted for the three types of MBA programs. Both predictors contributed significantly to the prediction of overall value, regardless of the type of MBA program. Beta coefficients showed that the MBA degree and school or program variables exerted highly similar influences on the prediction of overall value across the three types of MBA programs, although the school or program variable exerted slightly greater influence than the MBA degree vari-able. When I used R2 to indicate effect size for the three models, the analysis of the statistical significance of differ-ences between pairs of models showed significant differdiffer-ences for the full-time versus part-time and part-time versus exec-utive comparisons (p<.05), but not for the full-time versus executive comparison. This suggests that, just as part-time students rate the overall value of the MBA lower than do full-time and executive students, the capacity to predict their ratings was also lower.

DISCUSSION

On the basis of the analysis of effect sizes, program type does not strongly affect satisfaction with the benefits of the MBA, evaluations of school or program quality, or ratings of the value of the MBA. Part-time students’ generally lower ratings on these measures, combined with the higher unexplained variance from the part-time regression model, suggested the

VALUE OF MBA DEGREES 43

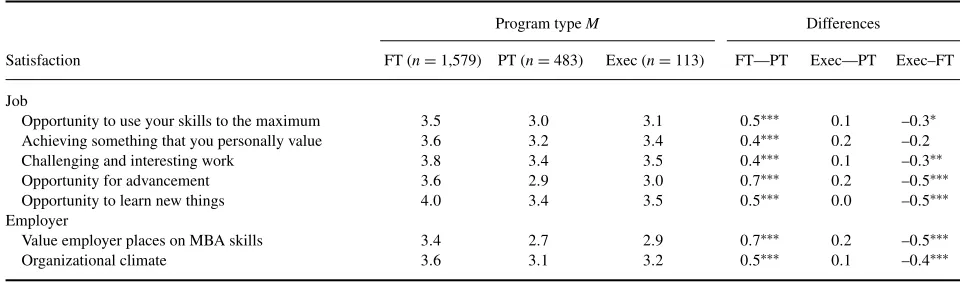

TABLE 6

Alumni Satisfaction with Employers, by Program Type

Program typeM Differences

Satisfaction FT (n=1,579) PT (n=483) Exec (n=113) FT—PT Exec—PT Exec–FT Job

Opportunity to use your skills to the maximum 3.5 3.0 3.1 0.5∗∗∗ 0.1 –0.3∗ Achieving something that you personally value 3.6 3.2 3.4 0.4∗∗∗ 0.2 –0.2 Challenging and interesting work 3.8 3.4 3.5 0.4∗∗∗ 0.1 –0.3∗∗ Opportunity for advancement 3.6 2.9 3.0 0.7∗∗∗ 0.2 –0.5∗∗∗ Opportunity to learn new things 4.0 3.4 3.5 0.5∗∗∗ 0.0 –0.5∗∗∗ Employer

Value employer places on MBA skills 3.4 2.7 2.9 0.7∗∗∗ 0.2 –0.5∗∗∗ Organizational climate 3.6 3.1 3.2 0.5∗∗∗ 0.1 –0.4∗∗∗

FT=full time; PT=part time; Exec=executive. ∗p<.05.

∗∗p<.01. ∗∗∗p<.001.

need to explore other factors that may influence part-time students’ attitudes. One other possible explanation related to work–life balance problems of part-time MBA students. Edgington (2003) reported that among pre-MBA students, those intending to enroll in part-time programs cited the fol-lowing reservations about pursuing an MBA more than did those intending to enroll in full-time programs: (a) “it might require more energy and time than I am willing to invest”; (b) “it might be too stressful”; and (c) “it might severely limit the time I have for people who are important to me.”

A second possible explanation for part-time graduates’ lower ratings of the overall value of the MBA related to their employment situations. According to the September 2004 MBA Alumni Perspectives survey, 77% of graduates of part-time programs were employed while they were in school, a significantly larger proportion than graduates of full-time programs, and 86% of part-time graduates were employed by the same employer they had at graduation (Edgington & Schoenfeld, 2004b). If overall value of the MBA is related to job satisfaction, and job satisfaction in turn is lower for graduates of part-time programs, it can be hypothesized that graduates of part-time programs will rate the value of the degree lower than graduates of full-time programs. I used data from three MBA Alumni Perspectives Surveys to ex-plore the aforementioned hypothesis. In surveys conducted from 2003 through 2005 (see Table 1), GMAC asked re-spondents: “How satisfied are you with your job?” They responded along a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very sastisfied). Alumni in these same surveys also rated the overall value of the MBA. I obtained data from these surveys and computed correlation coefficients. There is a positive correlation between job sat-isfaction and ratings of the overall value of the MBA in each survey (r=.38,r=.40, andr=.44, respectively). The results across three surveys conducted a year apart by GMAC (with a minimal amount of overlap in sample members) support

the first part of the hypothesis: The more satisfied respon-dents are with their jobs, the higher they rate the value of the MBA.

Alumni satisfaction with their jobs and employers is avail-able from the Alumni Perspectives survey conducted by GMAC in September 2004, in which alumni rated their satisfaction with several specific aspects of their jobs and employers using the same scale for general job satisfaction (Edgington & Schoenfeld, 2004b). Among respondents who were still working for the same employer they had after grad-uation, alumni from part-time programs were less satisfied than those from full-time programs on five important aspects of their jobs and on two important aspects of their employers (see Table 6). The hypothesized influence of the employment situations of students in part-time programs on their ratings of the overall value of the MBA was supported.

CONCLUSION

Negative rumblings about the MBA in recent literature have not considered evidence of graduating students’ attitudes to-ward the overall value of the degree and their satisfaction with potential benefits of the MBA, or their satisfaction with the schools and programs in which they are enrolled, evi-dence that generally presents a positive picture. The present article has attempted to fill that void by examining available evidence and exploring the predictability of overall value. MBA degree (category-level) and school or program (brand-level) predictors were shown to be relevant, although they explain less than one-half of the variance in overall value. Work–life balance and current employment situations likely contribute to the variation left unexplained in the model for part-time programs.

The type of MBA program a student attends does not have a large effect on attitudes toward degree benefits or

44 G. D. BRUCE

satisfaction with the school or program attended. However, when full- and part-time programs are compared, the lower ratings of the overall value of the MBA by part-time students, considered along with consistently lower satisfaction with degree benefits and the school or program attended, should attract the attention of part-time MBA program directors and strongly suggests the need for additional research on the attitudes and experiences of part-time MBA students.

NOTE

1. A list of participating schools is available from the author.

REFERENCES

Bennis, W., & O’Toole, J. (2005). How business schools lost their way.

Harvard Business Review,83, 96–104.

Chapman, G., & Niedermayer, L. (2001). What counts as a decision? Pre-dictors of perceived decision making.Psychonomic Bulletin and Review,

8, 615–621.

Cohen, J. (1988).Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences(2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Earlbaum.

Edgington, R. (2003).Mba.com registrants survey 2003 general report. Graduate Management Admission Council. Retrieved July 17, 2006, from http://www.gmac.com/NR/rdonlyres/18A69BD0–2EB3–414D-A7C7– 0009464B11B2/0/MBACOMREGISTRANTSSURVEYGENERALRE PORTFinal.pdf

Edgington, R., & Schoenfeld, G. (2004a).MBA alumni perspectives survey executive summary 2004–2005. Graduate Management Admission Council. Retrieved February 12, 2005, from http://www.gmac.com/

NR/rdonlyres/D850BECB-1571–421C-BA85-BFBDC3D9324C/0/MBAAlumniPerspectivesExecSumSept2004.pdf Edgington, R., & Schoenfeld, G. (2004b).MBA alumni perspectives survey

comprehensive report September 2004. Graduate Management Admis-sion Council. Retrieved March 17, 2005, from http://www.gmac.com/

NR/rdonlyres/AFE02CCB-FB54–49D2-A4F4-BAB1E4486579/0/September2004OverallReport.pdf

Ewers, J. (2005, April 11). Is the MBA obsolete?U.S. News & World Report,

138, 50–52.

Feldman, D. (2007). The food’s no good and they don’t give us enough: Re-flections on Mintzberg’s critique of MBA education.Journal of Education for Business,82, 217–220.

Graduate Management Admission Council. (2003a).Global MBA grad-uate survey 2003 summary report. Retrieved August 12, 2006, from http://www.gmac.com/NR/rdonlyres/595C1B31–0599–479D-9DA2– 5F40648CE3E7/0/ExecSummaryGlobal2003.pdf

Graduate Management Admission Council. (2003b).MBA alumni perspec-tives survey March 2003. Retrieved August 12, 2006, from http://www.

gmac.com/NR/rdonlyres/33DAE7E1–8EE1–4C73-A7F6–3F53327DBB 05/0/MBAAlumniPerspectivesSurveyMarch2003Report.pdf

Graduate Management Admission Council. (2004a).Global MBA graduate survey 2004. Retrieved August 12, 2006, from http://www.gmac.com/ NR/rdonlyres/C0B737DA-017B-4996–83A0–0D68DF178100/0/2004-GeneralReport.pdf

Graduate Management Admission Council. (2004b).Comprehensive re-port April 2004 MBA alumni perspectives survey. Retrieved July 22, 2006, from http://www.gmac.com/NR/rdonlyres/36AAE5FA-06EB-4256-A371–8329A69B7A72/0/AlumniApril2004ReportFinal.pdf Graduate Management Admission Council. (2005).Global MBA graduate

survey 2005 general report. Retrieved July 22, 2006, from http://www. gmac.com/NR/rdonlyres/7EEFE0DF-6804–420D-957D-DA5D8EE7CF 6C/0/GlobalMBAGeneralReport2005.pdf

Holtom, B., & Inderrieden, E. (2007). Investment advice: Go for the MBA.

BizEd, January/February, 36–40.

Inderrieden, E., Holtom, B., & Bies, R. (2006). Do MBA programs deliver? In C. Wankel & R. DeFillippi (Eds.),New visions of graduate management education(pp. 1–19). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. Martell, K. (2007). Assessing student learning: Are business schools

making the grade? Journal of Education for Business, 82, 189– 195.

Mintzberg, H. (2004).Managers not MBAs: A hard look at the soft practice of managing and management development. London: Prentice Education Ltd.

Murray, M. (2007). Corporate recruiters survey March 2007 general data report. Retrieved June 7, 2007, from http://www.gmac.com/NR/ rdonlyres/440ADD86-C549–402E-997F-DA86941E27A1/0/CorpRec SurveyGeneralDataReport2007.pdf

Nicholls, J., Harris, J., Morgan, E., Clarke, K., & Sims, D. (February, 1995). Marketing higher education: The MBA experience.International Journal of Educational Management, 9(2), 31–38.

Pfeffer, J., & Fong, C. T. (2002). The end of business schools? Less success than meets the eye.Academy of Management Learning and Education,1, 78–95.

Rosenthal, R., & Rosnow, R. L. (1991).Essentials of behavioral research: Methods and data analysis(2nd ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. Rubin, R., & Dierdorff, E. (2007, August).How relevant is the MBA?

Assessing the alignment of MBA curricula and managerial competencies. Paper presented at the Management Education & Development Division, Academy of Management, Philadelphia, PA.

Schoenfeld, G. (2005).MBA alumni perspectives survey comprehensive report April 2005. Graduate Management Admission Council. Re-trieved August 12, 2006, from http://www.gmac.com/NR/rdonlyres/ E6A527A7-EBA9–41BA-BEEB-474BEF01707E/0/MBAAlumniApril 2005OverallReport.pdf

Schoenfeld, G., & Bruce, G. (2005). School brand images and brand choices in MBA programs.2005 Symposium for the Marketing of Higher Educa-tion(pp. 130–139). Chicago: American Marketing Association. Zhao, J. J., Truell, A. D., Alexander, M. W., & Hill, I. B. (2006). Less success

than meets the eye? The impact of master of business administration education on graduates’ careers.Journal of Education for Business,81, 261–268.