Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 19:13

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Factors That Affect Students’ Capacity to Fulfill the

Role of Online Learner

Debra R. Comer, Janet A. Lenaghan & Kaushik Sengupta

To cite this article: Debra R. Comer, Janet A. Lenaghan & Kaushik Sengupta (2015) Factors That Affect Students’ Capacity to Fulfill the Role of Online Learner, Journal of Education for Business, 90:3, 145-155, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1007906

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1007906

Published online: 23 Feb 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 191

View related articles

Factors That Affect Students’ Capacity to Fulfill

the Role of Online Learner

Debra R. Comer, Janet A. Lenaghan, and Kaushik Sengupta

Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York, USABecause most undergraduate students are digital natives, it is widely believed that they will succeed in online courses. But factors other than technology also affect students’ ability to fulfill the role of online learner. Self-reported data from a sample of more than 200 undergraduates across multiple online courses indicate that students generally view themselves as having attributes that equip them for online learning. Additionally, course-level factors affect students’ online learning experiences. Specifically, students in qualitative (vs. quantitative) courses and in introductory (vs. advanced) classes reported more positive perceptions of their online learning and various aspects of their coursework.

Keywords: distance education, distance learning, online learner role, online learning, readiness for online learning

Enhancements in technology have led to an explosion in online learning. Many college and university presidents view online education as a critical component of their stra-tegic plan (Allen & Seaman, 2013) and commit substantial resources to meet the demand for online offerings (Young, 2011). According to a recent survey conducted by Babson College (Allen & Seaman, 2013), whereas only 1.6 million postsecondary students in the United States were enrolled in an online course in 2002, just one decade later, the num-ber had increased to 6.7 million, such that 32% of all stu-dents enrolled in higher education in the United States in 2012 had taken at least one course online. Results of the 2013 Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Busi-ness (AACSB) BusiBusi-ness School Questionnaire likewise indicate that between 2007 and 2012, the number of accred-ited schools that offer fully online courses rose 43%, and more than 25% of the 480 schools that had participated in every year of the survey had a fully online degree program (Nelson, 2013). The growth in online courses responds to students’ requirements for flexible scheduling (Daymont, Blau, & Campbell, 2011), as well as their need to develop the skills to perform in the virtual teams that are becoming

more prevalent in organizations (Arbaugh, 2014). This expansion in online education led U.S. News & World Reportto add the “Top Online Education Programs” rank-ing to its “Best of” lists in 2012 (DeSantis, 2012). Likewise, the Sloan Consortium, expecting growth in online programs globally, has recently renamed itself the Online Learning Consortium (Straumsheim, 2014).

Students’ learning in online courses has often been com-pared with their learning in more traditional, face-to-face courses. Because many students today are digital natives, who have used technology their entire lives (Prensky, 2001; see also Palfrey & Gasser, 2008), it may be taken for granted that they will embrace the technology associated with online classes and flourish in such classes. However, there is more to success in an online course than technologi-cal ability. Students favor online learning for its conve-nience; those whose work or family responsibilities would make it onerous or impossible to attend classes on campus especially appreciate the opportunity online programs afford (Beqiri, Chase, & Bishka, 2010; Bocchi, Eastman, & Swift, 2004). Yet, just because online learning is available to an individual does not mean that the individual will excel as an online learner. In this study, using a sample of under-graduate students enrolled in various online classes offered by the management department of an AACSB-accredited school, we investigated attributes that may predispose stu-dents to have positive online learning experiences.

Correspondence should be addressed to Debra R. Comer, Hofstra Uni-versity, Zarb School of Business, Department of Management and Entre-preneurship, Hempstead, NY 11549-1340, USA. E-mail: debra.r. comer@hofstra.edu

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1007906

PERCEPTIONS ABOUT THE EFFECTIVENESS OF ONLINE LEARNING1

Despite the rapid expansion of online programs, unfavor-able perceptions persist. According to Allen and Seaman (2013), chief academic officers in the United States report that only 30.2% of “their faculty accept the value and legitimacy of online education” (p. 27); even at institu-tions that have fully online courses, academic leaders report that only 38.4% of the faculty members fully accept online education. In 2010, the University of Cali-fornia offered a $30,000 bonus to create an online course, but only 70 of thousands of faculty members designed such a course, due to their skepticism about the efficacy of online education (Asimov, 2012). Some faculty mem-bers express concern that lack of face-to-face interaction in an online course diminishes student engagement (Aggarwal, Adlakha, & Mersha, 2006; Barker, 2010; Zemsky & Massy, 2004). To be sure, online instructors must avoid a hit-and-run approach in which they merely post canned lectures and notes on their institution’s course management system (e.g., Blackboard). When a distance learning course is poorly planned and executed, students’ satisfaction and learning suffer (Lawrence & Singhania, 2004; Vamosi, Pierce, & Slotkin, 2004). However, a thoughtful educator can structure and present an online course in a way that promotes students’ interaction with their fellow students and instructor and their mastery of course concepts (Arbaugh & Benbunan-Fich, 2007; Son-ner, 1999).

EMPIRICAL RESEARCH ON THE EFFECTIVENESS OF ONLINE LEARNING

A mounting body of research indicates that students in online classes achieve the same learning outcomes as their counterparts in traditional face-to-face classes (Arbaugh, 2000; Redpath, 2012). Online learning can foster interac-tivity (Han & Hill, 2006; Kuo, Walker, Schroder, & Bel-land, 2014; Swan, 2002) and collaboration (Arbaugh, 2008, 2010, 2014; Yoo, Kanawattanachai, & Citurs, 2002), and even promote the participation of students who would be less likely to contribute to face-to-face discussions (see, e.g., Comer & Lenaghan, 2013). Hansen (2008) asserted that participation and a sense of community are stronger in online courses because students’ interactions are open-ended and unbounded by time. Because of variability in the design and delivery of both face-to-face courses and online courses, simple comparisons between the two types are misguided and misleading. Instead, it seems that a given online course will be pedagogically effective to the extent that the instructor creates a community of learners by designing the course appropriately; giving students ample opportunities to connect to the course material, to

their instructor, and to one another; and ensuring that stu-dents can understand, apply, and synthesize course mate-rial (see Shea et al., 2010; see also Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007).

EMBRACING THE ROLE OF ONLINE LEARNER

Pitting online learning against face-to-face learning has dis-tracted scholars from ascertaining whether online learning is appropriate for all students. Yet, it has been asserted that “distance learning is not for everyone” (Crow, Cheek, & Hartman, 2003, p. 338), and our collective experience teaching online for numerous semesters suggests that stu-dents do vary in their readiness for online learning. Although some of our students excel in our online courses, others have trouble completing course requirements. Part of the problem may be that some members of the latter group misjudge what online learning entails. Previous studies of factors that affect students’ performance in online classes examine familiarity and comfort with e-learning (McVay, 2001; Smith, Murphy, & Mahoney, 2003), computer tech-nology (Bernard, Brauer, Abrami, & Surkes, 2004; Crow et al., 2003), and dispositional self-management (Hollen-beck, Zinkhan, & French, 2005; Mariola & Manley, 2002; Salas, Kosarzycki, Burke, Fiore, & Stone, 2002; Smith et al., 2003). However, they do not consider these attributes in terms of students’ fulfillment of the responsibilities inherent in the role of online learner.

A role represents shared normative expectations that drive and explain behavior (Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, & Rosenthal, 1964). A given role is defined vis-a-vis its rela-tionship with another role in a role set, such that one person assumes the principal role while the other assumes a counter-position (Stryker & Burke, 2000). Counter-role partners (e.g., supervisor and subordinate or teacher and student) shape each other’s behavioral expectations. The performance of any student—whether in a traditional face-to-face class or a wholly asynchronous online class—relies in large part on the student’s acceptance of key role responsibilities.

The role responsibilities students must assume when they take an online class are substantively—and, apparently, for some students, surprisingly—different from those required of students in a traditional face-to-face class. Students need to adjust their behavior, anchored in a traditional model of deliv-ery, to fit the role expectations of the online modality. They may erroneously assume that online courses require less work than traditional courses (Crow et al., 2003).2In reality, online students have at least as much coursework as students in tradi-tional classes, but they have more leeway as to when and where they will complete it (Fisher, King, & Tague, 2001). With their greater autonomy (to paraphrase Stan Lee) comes greater responsibility. Online students have to work indepen-dently and exercise self-discipline to negotiate course

requirements and meet deadlines. They need to be more active and self-directed learners than passive and teacher-directed followers (Fisher et al., 2001; Knowles, 1990; McVay, 2001). Students with superior time management skills and higher self-efficacy are more likely to continue in an online program (Holder, 2007). Those who routinely pro-crastinate perform worse in online courses, in part because they do not participate sufficiently in discussion forums (Michinov, Brunot, Le Bohec, Juhel, & Delaval, 2011).

Indeed, interaction and participation are other key aspects of the role of online learner (Arbaugh & Benbunan-Fich, 2007; Swan, 2002). Students will succeed to the extent that they engage in online discussions and contribute to their com-munity of learners (McIsaac & Gunawardena, 1996). More-over, students’ level of participation in online threaded discussions is related to their course performance (Hwang & Francesco, 2010; Krentler & Willis-Flurry, 2005). Given that coursework in asynchronous online classes relies on text-based communication, students need to write well. They also need to be able to resolve inevitable technical glitches. Stu-dents who can meet the requirements of the online learner role would be more likely to fare well in an online course. Thus:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Students whose personal attributes enhance their capacity to perform the responsibilities inherent in the role of online learner would have more favorable perceptions of their learning in an online course and more positive perceptions of various aspects of the course.

Other Factors That May Affect Fulfillment of the Responsibilities of the Online Learner Role

In addition to students’ personal attributes, other factors that may affect their ability to perform the responsibilities of the online learner role. One factor is the type of course material. The way course content is disseminated and learned varies by course (Arbaugh, 2005), and there are “discipline-related dif-ferences in online learning outcomes” (Arbaugh & Rau, 2007, p. 67). Although our study sample included only man-agement courses, manman-agement is a multidisciplinary field of study (Arbaugh, 2007). Even in face-to-face classes, instruc-tors of quantitative subjects may be inclined to rely on tradi-tional pedagogical methods to impart facts and formulae to their students. In face-to-face qualitative courses, on the other hand, instructors are more apt to use collaborative learning and to rely upon active learning. Students who enroll in an online qualitative course likely expect to be participating in group discussions and otherwise assuming an active part in their learning. Students may be less likely to anticipate the extent to which an online quantitative course will require active learning; thus, they may take such a course even though they are not ready to take on the role responsibilities of an online learner. Accordingly, we formulated the following hypothesis:

H2: Students enrolled in qualitative online courses would have more favorable perceptions of their learning and more positive experiences with various aspects of the course than would students enrolled in quantitative online courses.

By the same token, students may respond differently to a more advanced course than to an introductory course. An emerging stream of research suggests that students’ percep-tions of their learning and of the effectiveness of online deliv-ery are related not only to course discipline and content, but also to whether a course is at the introductory or advanced level (Arbaugh, 2013; Arbaugh, Desai, Rau, & Sridhar, 2010; Arbaugh & Rau, 2007; Chen, Jones, & Moreland, 2013). According to these findings, the effectiveness of online learn-ing may decrease at higher levels, as course material becomes more difficult conceptually (Chen et al., 2013). Moreover, stu-dents enrolled in more advanced courses express a greater need for face-to-face interaction than those enrolled in a principles course (Chen et al., 2013). We therefore expected that students in an introductory course would respond more positively to online learning than would those in upper level courses:

H3: Students in an introductory-level course would have more favorable perceptions of their learning in an online course and more positive experiences with vari-ous aspects of the course than would students in more advanced courses.

Course duration is another factor expected to affect per-ceptions of online learning. Postsecondary students in face-to-face courses generally prefer nontaxing workloads (see Sperber, 2005). It is safe to conclude that students in online courses do, too. To the extent that an online course is administered over a shorter period of time, the role demands on any given day would be greater than those in a course whose contents are distributed over a longer period. We therefore expected online students to respond less posi-tively to highly compressed courses:

H4:Students enrolled in online courses of longer duration would have more favorable perceptions of their learn-ing and more positive experiences with various aspects of the course than would students enrolled in online courses of shorter duration.

METHOD

Sample

The sample consisted of undergraduate students enrolled in 13 completely asynchronous online courses in the management department of the AACSB-accredited busi-ness school of a medium-sized private nonsectarian

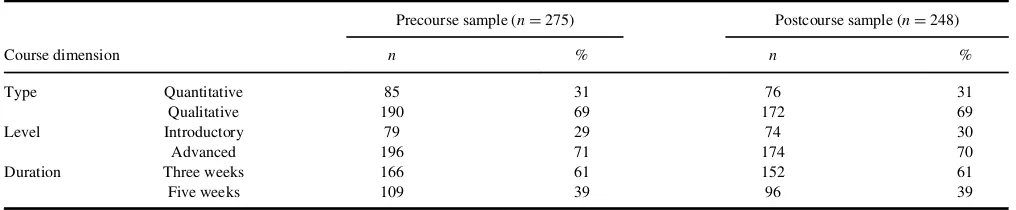

university in the Northeast United States. These courses were offered over condensed semesters during summer and winter sessions, between 2009 and 2011. We col-lected data from four sections of an introduction to man-agement course and from nine sections of advanced courses: four sections of operations management, three sections of purchasing and supply management, and two sections of recruitment and selection. The operations management course is highly quantitative, and the other courses are qualitative. Eight classes lasted three weeks and five lasted five weeks (see Table 1).

Measures

Students anonymously completed two surveys, one before starting their course and the other after completing the course. In order to encourage students to respond to the sur-vey, and following Chalmers’s (2009) advice to award stu-dents course credit for every piece of work in an online class, we gave students a small portion of course credit for completing each survey. The response rate was virtually 100% across samples. We had to exclude the responses of a tiny number of students, who either failed to answer several questions or whose answers we flagged as nonusable. Addi-tionally, because we were looking at students’ readiness for and perceptions of online learning, we considered responses only from those students who were taking their first online course.

A 50-item precourse survey assessed students’ readiness for online learning. Each item in the survey instrument was coded on a 4-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). Course materials were not available to students until the survey deadline had passed. Thus, responses on this precourse scale reflect students’ self-perceptions before they had completed any coursework. The postcourse survey, administered at the end of each course, tapped students’ perceptions of their learn-ing and of various aspects of the course. Students were instructed that their final course grade would not be posted until they completed the survey.

We derived several of the items for the presurvey and postsurvey from four extant scales used in studies of online or hybrid learning (Fisher et al., 2001; M. J. Jack-son & Helms, 2008; Kizlik, 2005; RobinJack-son & Hull-inger, 2008). Additionally, we each developed our own items, based on our collective experiences as to appro-priate practices and principles of online course design. Each of us independently came up with items, and then had multiple discussions and iterations to agree on the final list of items that constituted the scales for the two surveys.

Because we collected self-reported data, we adopted several well-accepted ex ante approaches during survey design and data collection in order to minimize the possibil-ity of common method variance (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). We sampled multiple courses and multiple sections within these courses, over different semesters and across three years. In addition, we ordered the questions in both surveys to separate like items, thereby reducing the likelihood of consistency motive and theory-in-use biases in the students’ responses (Podsakoff et al., 2003). We also used theex postapproach of analyzing the data with Harman’s single-factor test. For each survey, the single-factor solution extracted only 17% of the variance, and the final multifactor solution explained significantly more of the variance. We therefore believe that common method variance does not threaten the analysis and interpre-tation of our data. The analyses that follow are based on 275 usable responses for the precourse survey and 248 for the postcourse survey. We have fewer completed postcourse surveys because some students withdrew from their respec-tive courses before taking the postcourse survey (see Table 1).

RESULTS

Factor Analysis of Scales

Items of both the precourse and postcourse surveys were factor analyzed with principal component analysis

TABLE 1

Percentage of Sample by Course Dimension

Precourse sample (nD275) Postcourse sample (nD248)

Course dimension n % n %

Type Quantitative 85 31 76 31

Qualitative 190 69 172 69

Level Introductory 79 29 74 30

Advanced 196 71 174 70

Duration Three weeks 166 61 152 61

Five weeks 109 39 96 39

The postcourse sample is smaller because some students withdrew from their course before it was administered.

extraction and varimax rotation. We used the following cri-teria to determine the factors:

1. The total variance explained with the multiple factors was significantly higher than the variance explained with Harman’s single-factor solution.

2. A minimum of three items loaded on each factor.

3. Factor loadings for each of the items for a factor were at least .4 (which is higher than the normally accepted level of .3; Hair, Tatham, Anderson, & Black, 1998). In addition, the factor loadings for a specific item were higher on that factor than on any other factor. 4. The Cronbach’s Alpha reliability coefficient for each

factor was at least .5 (Hair et al., 1998).

TABLE 2

Factor Analysis of Precourse Scale

Factors

Capability Self-discipline Active learning

Overall learning orientation

I know how and where to search for information. .657 I am able to stay focused on a complex problem until I can solve it. .610 I feel at ease when working with computers, a variety of software applications, and the

Internet.

.588

I can easily follow written instructions. .570 I possess sufficient computer and software knowledge (or have ready access to adequate

support resources) to complete an on-line course.

.535

I recognize that technical problems are likely to occur on occasion and feel that I can work through such problems successfully.

.528

I take responsibility for my own learning. .469 I am the kind of person who is curious about many things. .467 Whenever I have a question, I tend to try to figure out the answer for myself before asking

someone else for help.

.465

I often figure out new ways to solve problems. .463 I can determine what I need to do in a particular situation and then come up with a way of

doing it.

.440

I am methodical whenever I have to solve a problem. .438

I am proud of my writing skills. .435

I am an organized person. .739

I am good at budgeting my time. .713

I manage my time well. .676

I often make myself a schedule or a list of the things I need to do. .602 I schedule times during a typical day/week to do my schoolwork. .598

I prioritize my work. .564

People who know me consider me responsible. .552

I have a lot of self-discipline. .545

I often challenge myself by going beyond course requirements. .484 Once I have a set of goals or objectives, I can figure out what I need to do to reach them. .469

My peers regard me as a self-starter. .405

It is interesting to me to find out what my classmates think about an issue. .735 I like classes in which students contribute to one another’s learning. .724

I enjoy helping others learn. .639

Applying course concepts to my own experiences helps me learn. .602 I use feedback about one course requirement to improve my performance on a future course

requirement.

.520

I enjoy expressing my opinions to others. .496

I am able to translate course requirements into objectives that matter to me. .483 I learn course material well when I can apply it to real situations. .469

I expect this on-line course to be less demanding than a traditional course held in a classroom .599 I tend to depend on others to remind me about what I need to do. .568 I would rather ask my instructor a question about course requirements than have to look up the

information myself on the course syllabus.

.526

There is not much I can learn from my classmates. .468

I become frustrated easily. .466

I fulfill only the minimum requirements of a course. .451

I become overwhelmed when I have many deadlines coming up at the same time. .410

I am an underachiever. .401

5. The discriminant validity of the factors was less than .85, indicating that the factors were distinct from one another (Campbell, 1960; Campbell & Fiske, 1959).

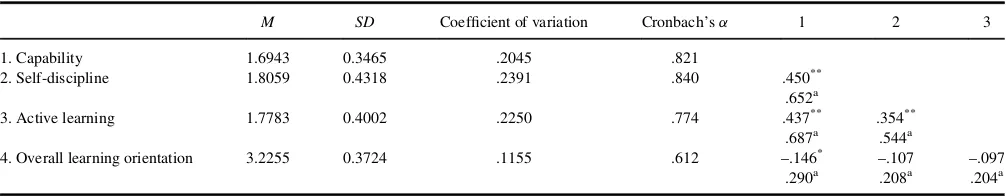

Precourse survey. Following these criteria, 40 of the 50 items in the precourse survey were retained (see Table 2). More than 35% of the variance was explained by these four factors: capability, students’ self-sufficiency and ability to do what is necessary in an online course (e.g., write and solve problems for themselves); self-discipline, students’ initiative and responsibility and their ability to manage their time and their activities; active learning, students’ tendency to engage fully with classmates and coursework; and overall learning orientation, students’ propensity to embrace the role of learners. Respondents’ perceptions of their greater readiness for learning online are associated with lower scores on the first three of the four factors and higher scores on the fourth factor. As Table 3 illustrates, the students in the sample generally perceived themselves as being suited for online learning. Although there are significant Pearson correlations between some of the factors, none of the dis-criminant validity scores approaches the threshold value of .85, with the highest score of .687 between capability and active learning. We analyzed the effect size parameters for the precourse survey factors using the three indices based on standardized mean differences (Cohen’sd, Hedges’sλ, and

Glass’sD). All three indices show a small effects size for

the factors. For instance, Cohen’sd ranges from less than .1–.26 (Cohen, 1988). The factor score is the mean of all the items loaded on that factor; all subsequent analyses are based on the factor scores.

Postcourse survey. Table 4 displays the items in the postcourse survey and the results of the factor analysis of responses to this survey. The analysis extracted four distinct factors, which together explain 43% of the variance: Students’ perceptions of their overall learning from the course, the value of course discussions and course materials, and the course workload. As expected, the reverse-coded items have negative factor loads; the scores on these items

are reversed for the reliability, correlation, and discriminant analyses. Low scores on the first three factors—learning, course discussions, and course materials—indicate a respondent’s favorable perceptions of learning. Low scores on course workload reflect a respondent’s perception that the course is demanding. The mean score for all four factors is around 2 (see Table 5), implying that students generally agree with the statements. In addition, the standard deviation values lie between .499 and .595, revealing a reasonably consistent set of responses within the sample. Similar to the precourse survey factors, the factors in the postcourse survey show some significant inter-factor correlations. However, the discriminant validity scores are low, with the highest score of .778 below the .85 threshold value. The standard-ized mean differences indices show a small to medium effects size for the postcourse survey factors. For instance, Cohen’sdhas a range of .03 to .46 (Cohen, 1988). Although some of the effects sizes were small, the testing of the hypotheses as discussed below shows that results are mixed, with support for some of the hypotheses.

Testing of Hypotheses

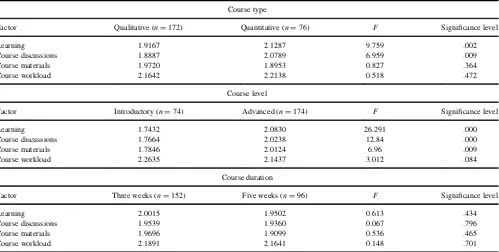

None of the correlations between the four precourse scale factors and the four postcourse scale factors are significant (see Table 6). In short, we did not find support forH1. We tested the remaining hypotheses using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) because our data involve categorical (two-level) variables. Table 7 shows the relationship between students’ perceptions of various aspects of online learning and course type, course level, and course duration.

The scores of students in the qualitative courses are sig-nificantly lower than those of students in the quantitative course for both learning and course discussions. The scores in the qualitative courses are lower for course workload and higher for course materials, at a nonsignificant level. Based on these results, we found partial support forH2. Students in the introductory classes have significantly more favor-able views of learning, course discussions, and course materials. Those students in the advanced classes are more

TABLE 3

Descriptive Statistics, Correlations, and Discriminant Validity Coefficients of Precourse Factors

M SD Coefficient of variation Cronbach’sa 1 2 3

1. Capability 1.6943 0.3465 .2045 .821

2. Self-discipline 1.8059 0.4318 .2391 .840 .450**

.652a

3. Active learning 1.7783 0.4002 .2250 .774 .437** .354**

.687a .544a

4. Overall learning orientation 3.2255 0.3724 .1155 .612 –.146* –.107 –.097

.290a .208a .204a

aDiscriminant validity coefficient should be less than .85. *

p<.05.**p<.01.

likely, at a marginally significant level, to perceive the course workload as more demanding. We thus found sup-port for H3. In contrast, the results indicate that course duration does not affect the scores significantly on any of the four factors. We found no support forH4.

DISCUSSION

Many have compared online learning to face-to-face learn-ing. In contrast, we conducted this study with the premise that online learning can be just as effective and rewarding

TABLE 4

Factor Loadings of Postcourse Scale

Outcome factors

Learning Course discussions Course materials Course workload

I probably learned less in this on-line class than I would have learned in a face-to-face class.R

–.736

I felt more isolated from my instructor than I do in face-to-face courses.R –.604 I learned a lot from this course. .590 After taking this course, my interest in this subject matter has increased. .578 After taking this on-line course, I would like to take other on-line courses. .571 Completing this course has increased my confidence in my writing abilities. .571 Completing this course has enhanced my ability to organize my work. .551 Taking this course has made me recognize that I can learn on my own. .521 I found it more difficult to relate to the other students in this course than in the

face-to-face courses I’ve taken.R

–.479

Reading my classmates’ comments on the Discussion Boards helped me understand and apply the course concepts.

.802

Responding to my classmates’ comments on the Discussion Boards helped me understand and apply the course concepts.

.767

Posting my original comments on the Discussion Boards helped me understand and apply the course concepts.

.681

I was more comfortable participating in discussions in this course than I usually am in face-to-face courses.

.596

Taking this course has made me recognize that I can learn from other students. .553 Taking this course has taught me that I prefer expressing my opinions in writing

rather than orally.

.536

It was appropriate to assess students’ performance in this class on the basis of their comments on the Discussion Boards.

.472

The audio slideshows helped me learn the course materials. .778 I relied heavily on the audio slideshows to learn the materials in this course. .771 The videos helped me understand and apply the course concepts. .634 I relied heavily on the videos to learn the materials in this course. .583 This course has been one of the more demanding courses I have taken as a college

student.

.705

This course required more time than I had expected. .693

I worked hard to keep up with the course schedule and deadlines. .477 At the start of the course, it took me a lot of time to understand the course delivery,

structure, and requirements.

.476

RDreverse coded item.

TABLE 5

Descriptive Statistics, Correlations, and Discriminant Coefficients of Postcourse Factors

M SD Coefficient of variation Cronbach’sa 1. 2. 3.

1. Learning 1.982 0.501 .252 .836

2. Course discussions 1.947 0.529 .272 .823 .646**

.778a

3. Course materials 1.947 0.595 .305 .780 .409** .406**

.506a .507a

4. Course workload 2.179 0.499 .229 .532 –.012 .062 .045

–.018a .094a .069a

aDiscriminant validity coefficient should be less than 0.85. **

p<.01.

as traditional face-to-face pedagogy, but that its effective-ness may vary with students’ capacity to fulfill the responsi-bilities of the online learner role. We expected that attributes of students would affect their ability to fulfill that role, as would aspects of courses.

The students in our sample seemed to have a fairly uni-form and positive disposition to online courses. According to their responses to our precourse scale, they generally viewed themselves as ready to assume the role of the online learner. Specifically, they perceived themselves as self-suf-ficient, responsible, eager to engage with classmates and coursework, and oriented to learning. Given the increasing prevalence of online learning, these results bode well for colleges and universities. However, we cannot ignore the possibility of a response bias, due in part to students’ attempts to avoid postdecision dissonance (Vroom & Deci, 1971). Because the students we sampled were taking their first online course, they might have been experiencing a combination of excitement and apprehension. If so, in order

to quell their misgivings, they might have tried to “psych themselves up” by responding very positively to the pre-course questions. Furthermore, the prepre-course data we pres-ent come from studpres-ents who stayed in the course until at least the first week of the course. Our findings do not include the responses of students who withdrew between the time they completed the precourse survey and the beginning of the course. Indeed, we encouraged students to contemplate, as they completed the survey, the extent to which online learning would be appropriate for them. Also, insofar as students who believe that they will fare well as online learners may be more likely to register for online courses (see Perreault, Altman, & Zhao, 2002), it is plausi-ble that readiness for online learning may be higher in our sample than in the general population of undergraduate stu-dents. Indeed, upon administering the 40-item precourse survey to a group of 72 students in a face-to-face introduc-tory management class, we found that their scores on all four factors were less indicative of readiness for online

TABLE 6

Correlations Between Precourse Scale Factors and Postcourse Scale Factors

Precourse scale factors

Postscale factors Capability Self-discipline Active learning Overall learning orientation

Learning .048 .092 .112 –.023

Course discussions .104 .107 .096 .085

Course materials –.052 .019 .015 .013

Course workload –.109 –.067 –.063 .043

TABLE 7

Differences in Perceptions of Online Learning by Course Type, Level, and Duration

Course type

Factor Qualitative (nD172) Quantitative (nD76) F Significance level

Learning 1.9167 2.1287 9.759 .002

Course discussions 1.8887 2.0789 6.959 .009

Course materials 1.9720 1.8953 0.827 .364

Course workload 2.1642 2.2138 0.518 .472

Course level

Factor Introductory (nD74) Advanced (nD174) F Significance level

Learning 1.7432 2.0830 26.291 .000

Course discussions 1.7664 2.0238 12.84 .000

Course materials 1.7846 2.0124 6.96 .009

Course workload 2.2635 2.1437 3.012 .084

Course duration

Factor Three weeks (nD152) Five weeks (nD96) F Significance level

Learning 2.0015 1.9502 0.613 .434

Course discussions 1.9539 1.9360 0.067 .796

Course materials 1.9696 1.9099 0.536 .465

Course workload 2.1891 2.1641 0.148 .701

learning than the scores of the 79 students in our sample who took the same course online. Their self-reported capa-bility, initiative and responsicapa-bility, and propensity to engage actively with classmates and coursework were sig-nificantly higher,tD2.20,pD.0292;tD3.12,pD.0022; and t D 3.98, p D .0001, respectively, and their self-reported overall learning orientation was significantly lower

tD9.70,pD.0001.

We had expected to find a relationship between students’ readiness to fulfill the responsibilities of the online learner role and their perceptions of online learning. That we did not can be attributed, at least in part, to the fact that students who were not performing well in their respective courses (or not as well as they would have liked) withdrew before taking the posttest. It is reasonable to assume that the slightly more than 10% of students who withdrew from their online courses would have responded less positively about their online learning experiences. Their leaving the course before taking the posttest restricted the range of responses we obtained on this mea-sure. Future researchers should explore the relationship between readiness for online learning and perceptions of online coursework by assessing the latter before the very end of the semester.

Our other results provide some information about factors that affect students’ perception of their learning in online courses. The results show that students in qualitative courses have more favorable perceptions of learning and course discussions than their counterparts in quantitative courses. However, students’ enrollment in quantitative ver-sus qualitative courses does not seem to affect their percep-tions of course materials or course workload.

We also found that students in introductory online clas-ses have more favorable perceptions of their learning, course discussions, and course materials; and students in advanced online classes perceive the course workload as more demanding. Upper level courses are objectively more challenging, covering topics with greater complexity and intensity. It could also be the case that students’ perceptions change as they take more advanced coursework. They may expect to derive more benefits from higher-level courses. Students may hold the delivery and quality of their advanced courses to a higher standard than do students in introductory-level courses; higher expectations are more difficult to satisfy. Additional studies could address whether the online learning platform is more suitable for introduc-tory-level courses, and explore ways to meet the needs of students in upper level online courses.

We expected students in five-week courses to have more favorable perceptions of their online courses than students in three-week courses. Both are compressed-format courses, covering the same material as courses taught over 15 weeks in a regular (fall or spring) semester. However, based on our extensive experience teaching both five-week and three-week courses, online and in a classroom, we note

a marked difference between them. Whereas the pace of a five-week course is brisk but manageable, that of a three-week course borders on exhausting and uncomfortable. Our findings suggest, nonetheless, that these differences are more salient to us than to our students, who perceive three-week courses no less positively than five-three-week courses. It is left for additional research to assess whether students’ per-ceptions of their learning in compressed online courses dif-fer from their perceptions of learning in full-semester online courses.3

Limitations

Our results are based on a sample of undergraduate business students at one AACSB-accredited business school in Northeast United States. Further studies are required to examine whether the same results hold with other student populations in different geographic locations. Although the students in our sample perceived themselves as ready for online learning, their counterparts at other postsecondary institutions may be less equipped. Many undergraduate stu-dents lack a sense of responsibility for their own learning and are also deficient in other behaviors and strategies that contribute to success in meeting the demands of college-level coursework—in the traditional or online classroom (Conley & French, 2014; J. Jackson & Kurlaender, 2014; Tierney & Sablan, 2014). Additionally, because of our focus, all of the students in this sample were taking their first online courses. It is up to future research to examine whether the perceptions we assessed change when students take successive online courses.

It bears repeating that we depended on self-reported measures. As discussed, we took steps to reduce the possi-bility of common method variance in the two surveys. However, it may make sense to gauge students’ readiness for online learning by asking them to have their close friends or family members complete the survey about them rather than using the survey as a self-report instrument.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the research regarding online learning in business education. Our findings indicate that course content and level (but not course duration) affect students’ perceptions of their overall learning, course dis-cussions, course materials, and course workload. We look to future research to explore other curricular components that may contribute to students’ responses to online learn-ing. Additionally, preliminary results suggest that our 40-item precourse survey has potential as a tool to guide stu-dents in gauging their readiness for online learning. As mentioned, the scale scores of 72 students enrolled in a tra-ditional (i.e., nononline) introductory management class indicate that they were less ready for online learning than the students in the online classes of the same course.4We

plan to collect more data to ascertain the suitability of our readiness-for-online-learning scale as a tool for guidance. As an increasing number of business schools expand their online offerings, understanding the factors that enhance students’ capacity to fulfill the responsibilities of the online learner role can help academicians and administrators design and deliver online programs. Meanwhile, giving stu-dents information as to how well they may fare as online learners may reduce disappointment and increase retention in online courses.

NOTES

1. In this study, we focused on asynchronous online courses characterized by a relatively small number of students, thus facilitating extensive interaction among students and between students and their instructor. Therefore, we do not consider massive open online courses (MOOCs), which have a very different aim and focus. Nor do we consider synchro-nous online courses nor hybrid/blended courses. 2. Students’ unrequited expectations likely contribute to

the lower retention rates identified in online versus traditional classes (Allen & Seaman, 2013; Heyman, 2010; Kember, 1996).

3. We did not have an opportunity to analyze full-semester online courses in this study because our institution introduced such courses only recently. 4. We compared the scores of the class of traditional

students to the subset of our online sample in the same course to minimize the effects of other factors. It should be noted that their scores were also signifi-cantly different on all four factors when compared to those of the whole online sample.

REFERENCES

Aggarwal, A. K., Adlakha, V., & Mersha, T. (2006). Continuous improve-ment process in web-based education at a public university.E-Service Journal,4(2), 3–26.

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2013).Changing course: Ten years of tracking online education in the United States. Babson Park, MA: Babson Survey Research Group. Retrieved from http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/ reports/changingcourse.pdf

Arbaugh, J. B. (2000). Virtual classroom versus physical classroom: An exploratory comparison of class discussion patterns and student learning in asynchronous internet-based MBA course.Journal of Management Education,24, 207–227.

Arbaugh, J. B. (2005). How much does “subject matter” matter? A study of disciplinary effects in on-line MBA courses.Academy of Management Learning and Education,4, 57–73.

Arbaugh, J. B. (2008). Does the community of inquiry framework predict outcomes in on-line MBA courses?International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning,9, 1–21.

Arbaugh, J. B. (2010). Sage, guide, both, or even more? An examination of instructor activity in on-line MBA courses.Computers and Education,

55, 1234–1244.

Arbaugh, J. B. (2013). Does discipline moderate COI-course outcomes relationships in online MBA courses?The Internet and Higher Educa-tion,17, 16–28.

Arbaugh, J. B. (2014). What might online delivery teach us about blended management education? Prior perspectives and future directions.Journal of Management Education,38, 784–817. doi:10.1177/1052562914534244 Arbaugh, J. B., & Benbunan-Fich, R. (2007). The importance of participant

interaction in online environments.Decision Support Systems,43, 853–865. Arbaugh, J. B., Desai, A., Rau, B., & Sridhar, B. S. (2010). A review of

research on online and blended learning in the management disciplines: 1994–2009.Organization Management Journal,7, 39–55.

Arbaugh, J. B., & Rau, B. L. (2007). A study of disciplinary, structural, and behavioral effects on course outcomes in online MBA courses.Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education,5, 65–95.

Asimov, N. (2012, June 22). Online education has teachers conflicted.The San Francisco Chronicle.Retrieved from http://www.sfgate.com/educa tion/article/Online-education-has-teachers-conflicted-3654171.php. Barker, R. (2010). No, management is not a profession.Harvard Business

Review,88(7–8), 52–60.

Beqiri, M. S., Chase, N. M., & Bishka, A. (2009). Online course delivery: An empirical investigation of factors affecting student satisfaction. Jour-nal of Education for Business,85, 95–100.

Bernard, R. M., Brauer, A., Abrami, P. C., & Surkes, M. (2004). The devel-opment of a questionnaire for predicting online learning achievement.

Distance Education,25, 31–47.

Bocchi, J., Eastman, J. K., & Swift, C. O. (2004). Retaining the online learner: Profile of students in an online MBA program and implications for teaching them.Journal of Education for Business,79, 245–253. Chalmers, R. (2009). Teaching online: How to get started.CTSE

Newslet-ter,5(2), 9.

Chen, C. C., Jones, K. T., & Moreland, K. A. (2013). Online accounting education versus in-class delivery: Does course level matter?Issues in Accounting Education,28, 1–16.

Cohen, J. (1988).Statistical power for the behavioral sciences(2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Conley, D. T., & French, E. M. (2014). Student ownership of learning as a key component of college readiness.American Behavioral Scientist,58, 1018–1034.

Comer, D. R., & Lenaghan, J. (2013). Enhancing discussions in the asynchronous online classroom: The lack of face-to-face interaction does not lessen the lesson.Journal of Management Education,37, 261–294.

Crow, S. M., Cheek, R. G., & Hartman, S. J. (2003). Anatomy of a train wreck: A case study in the distance learning of strategic management.

International Journal of Management,20, 335–341.

Daymont, T., Blau, G., & Campbell, D. (2011). Deciding between tradi-tional and online formats: Exploring the role of learning advantages, flexibility, and compensatory adaptation. Journal of Behavioral & Applied Management,12, 156–175.

DeSantis, N. (2012). “U.S. News” sizes up online degree programs, with-out saying who’s no. 1.Chronicle of Higher Education,58(20), A20. Fisher, M., King, J., & Tague, G. (2001) Development of a self-directed

learning readiness scale for nursing education.Nurse Education Today,

21, 516–525.

Garrison, D. R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions.Internet and Higher Education,10, 157–172.

Hair, J. F., Tatham, R. L., &erson, R. E., & Black, W. (1998),Multivariate data analysis(5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Han, S., & Hill, J. R. (2006). Building understanding in asynchronous dis-cussions: Examining types of online discourse.Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks,10(4), 29–50.

Hansen, D. E. (2008). Knowledge transfer in on-line learning environ-ments.Journal of Marketing Education,30, 93–105.

Heyman, E. (2010). Overcoming student retention issues in higher educa-tion online programs.Online Journal of Distance Learning Administra-tion, 13(4). Retrieved from http://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/ winter134/heyman134.html

Holder, B. (2007). An investigation of hope, academics, environment, and motivation as predictors of persistence in higher education online pro-grams.Internet and Higher Education,10, 245–260.

Hollenbeck, C. R., Zinkhan, G. M., & French, W. (2005). Distance learn-ing trends and benchmarks: Lessons from an online MBA program.

Marketing Education Review,15(2), 39–52.

Hwang, A., & Francesco, A. (2010). The influence of individualism-collec-tivism and power distance on use of feedback channels and consequen-ces for learning.Academy of Management Learning & Education,9, 243–257.

Jackson, J., & Kurlaender, M. (2014). College readiness and college com-pletion at broad access four-year institutions.American Behavioral Sci-entist,58, 947–971.

Jackson, M. J., & Helms, M. M. (2008). Student perceptions of hybrid quality: Measuring and interpreting quality.Journal of Education for Business,84, 7–12.

Kahn, R. L., Wolfe, D. M., Quinn, R. P., Snoek, J., & Rosenthal, R. A. (1964).Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. New York, NY: Wiley.

Kember, D. (1996).Open learning courses for adults: A model of student progress. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology.

Kizlik, R. (2005). Getting ready for distance education: Distance Education Aptitude and Readiness Scale (DEARS). Adprima: Toward the best. Retrieved from http://www.adprima.com/dears. htm

Knowles, M. S. (1990).The adult learner: A neglected species. Houston, TX: Gulf.

Krentler, K. A., & Willis-Flurry, L. A. (2005). Does technology enhance actual student learning? The case of online discussion boards.Journal of Education for Business,80, 316–321.

Kuo, Y., Walker, A. E., Schroder, K., & Belland, B. (2014). Interaction, internet self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses.The Internet and Higher Educa-tion,20, 35–50.

Lawrence, J. A., & Singhania, R. P. (2004), A study of teaching and testing strategies in a required statistics course for undergraduate business stu-dents.Journal of Education for Business,79, 333–338.

Mariola, E., & Manley, J. (2002). Teaching finance concepts in a distance learning environment—A personal note.Journal of Education for Busi-ness,77, 177–180.

McIsaac, M. S., & Gunawardena, C. N. I. (1996). Distance education. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.),Handbook of research for educational communica-tions and technology(pp. 403–437). New York, NY: Simon & Shuster Macmillan.

McVay, M. (2001).How to be a successful distance learning student: Learning on the Internet. New York, NY: Prentice Hall.

Michinov, N., Brunot, S., Le Bohec, O., Juhel, J., & Delaval, M. (2011). Procrastination, participation, and performance in online learning envi-ronments.Computers & Education,56, 243–252.

Nelson, C. (2013).Our reach. Retrieved from http://aacsbblogs.typepad. com/dataandresearch/accreditation/

Palfrey, J. G., & Gasser, U. (2008).Born digital: Understanding the first generation of digital natives. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Perreault, H., Waldman, L., & Zhao, M. A. J. (2002). Overcoming barriers to successful delivery of distance-learning courses.Journal of Education for Business,77, 313–318.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies.Journal of Applied Psychology,

88, 879–903.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants: Part I. On the Horizon,9(5), 1–6.

Redpath, L. (2012). Confronting the bias against on-line learning in man-agement education.Academy of Management Learning & Education,

11, 125–140.

Robinson, C. C., & Hullinger, H. (2008). New benchmarks in higher edu-cation: Student engagement in online learning.Journal of Education for Business,84, 101–109.

Salas, E., Kosarzycki, M. P., Burke, C. S., Fiore, S. M., & Stone, D. L. (2002). Emerging themes in distance learning research and practice: Some food for thought.International Journal of Management Reviews,4, 135–153. Shea, P., Hayes, S., Vickers, J., Gozza-Cohen, M., Uzuner, S., Mehta, R.,

. . .Rangan, P. (2010). A re-examination of the community of inquiry framework: Social network and content analysis.Internet and Higher Education,13, 10–21.

Smith, P. J., Murphy, K. L., & Mahoney, S. E. (2003). Toward identifying factors underlying readiness for online learning: An exploratory study.

Distance Education,24, 57–67.

Sonner, B. S. (1999). Success in the capstone business course—Assessing the effectiveness of distance learning.Journal of Education for Busi-ness,74, 243–248.

Sperber, M. (2005). How undergraduate education became college lite— and a personal apology. In R. H. Hersh & J. Merrow (Eds.),Declining by degrees: Higher education at risk(pp. 131–143). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Straumsheim, C. (2014, July 7). Sloan goes online. Inside Higher Ed.

Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2014/07/07/ sloan-consortium-renames-itself-online-learning-consortium

Stryker, S., & Burke, P. J. (2000). The past, present, and future of an iden-tity theory.Social Psychology Quarterly,63, 284–297.

Swan, K. (2002). Building learning communities in online courses: The importance of interaction.Education Communication and Information,

2, 23–49.

Tierney, W. G., & Sablan, J. R. (2014). Examining college readiness.

American Behavioral Scientist,58, 943–946.

U.S. News and World Report. (2014). Best online graduate business pro-grams ranking. http://www.usnews.com/education/online-education/ mba/rankings?int=da9048

Vamosi, A. R., Pierce, B. G., & Slotkin, M. H. (2004). Distance learning in an accounting principles course—Student satisfaction and perceptions of efficacy.Journal of Education for Business,79, 360–366.

Vroom, V. H., & Deci, E. L. (1971). The stability of post-decision disso-nance: A follow-up study of the job attitudes of business school gradu-ates.Organizational Behavior & Human Performance,6, 36–49. Yoo, Y., Kanawattanachai, P., & Citurs, A. (2002). Forging into the wired

wilderness: A case study of a technology-mediated distributed discus-sion-based class.Journal of Management Education,26, 139–163. Young, J. R. (2011). College presidents are bullish on online education but

face a skeptical public.Chronicle of Higher Education,58(2), A16. Zemsky, R., & Massy, W. F. (2004).Thwarted innovation: What happened

to e-learning and why. Retrieved from http://thelearningalliance.info/ Docs/Jun2004/ThwartedInnovation.pdf