THE EFFECTS OF STUDENT TEAM-ACHIEVEMENT DIVISION COOPERATIVE LEARNING AND DIRECT INSTRUCTION ON

STUDENTS’ READING COMPREHENSION LEVELS

(A Mixed Method Study at Grade VIII of a Junior High School in Serang, Banten)

Thesis

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master’s Degree in English Education

By

Asep Suarman

1007015

GRADUATE SCHOOL

INDONESIA UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION

APPROVAL PAGE

This thesis entitled “THE EFFECTS OF STUDENT TEAM-ACHIEVEMENT

DIVISION COOPERATIVE LEARNING AND DIRECT INSTRUCTION ON STUDENTS’ READING COMPREHENSION LEVELS(A Mixed Method Study at Grade VIII of a Junior High School in Serang, Banten) has been approved by:

Supervisor

Emi Emilia, M, Ed., Ph. D. NIP. 196609161990012000

Head of English Education Study Program,

DECLARATION

I hereby certify that this thesis entitled,” The Effects of Student Team-Achievement

Division Cooperative Learning and Direct Instruction on Students’ Reading Comprehension Levels”, is completely my own work. I am fully aware that I have quoted and paraphrased some statements and ideas from other resources, and they are properly

acknowledged in the text.

Bandung, February, 2013

THE EFFECTS OF STUDENT TEAM-ACHIEVEMENT DIVISION

COOPERATIVE LEARNING AND DIRECT INSTRUCTION ON STUDENTS’

READING COMPREHENSION LEVELS

Asep Suarman 1007015

ABSTRACT

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TITLE SHEET ... i

APPROVAL SHEET ... ii

ABSTRACT ... iii

DECLARATION ... iv

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... v

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... vi

LIST OF TABLES ... ix

LIST OF CHARTS ... x

LIST OF APPENDICES ... xi

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study ... 1

1.2 Purpose of the Study ... 3

1.3 Research Question ... 3

1.4 Definition of the Terms ... 3

1.5 Significance of the Study ... 4

1.6 Structure of the Thesis ... 5

CHAPTER II: REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE 2.1 Reading Comprehension ... 6

2.1.1 Definitions of Reading Comprehension ... 6

2.1.2 Reading Comprehension Factors ... 8

2.1.3 Interactive Model or Approach of Reading Process ... 8

2.1.4 Reading Comprehension Levels ... 10

2.1.5 Reading Comprehension Skills ... 12

2.1.6 Teaching Reading Comprehension ... 15

2.1.7 Assessing Reading ... 18

2.2 Student Team Achievement Division (STAD) Cooperative Learning 19 2.2.1 Overview of Cooperative Learning ... 19

2.2.2 Principles of STAD CL ... 22

2.2.3 Procedures of STAD CL ... 23

2.2.4 Weaknesses of STAD CL ... 26

2.2.1 Definition of Direct Instruction ... 27

2.2.2 Principles of Direct Instruction ... 29

2.2.3 Procedures of Direct Instruction ... 30

2.2.4 Weaknesses of Direct Instruction... 32

2.4 Previous Study ... 33

2.5 Conclusion of the Chapter ... 34

CHAPTER III: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 3.1 Research Setting and Participants ... 35

3.2 Research Design ... 36

3.3 Data Collection Methods ... 37

3.4.1 Pretest and Post Test of Reading Comprehension ... 37

3.4.2 Class Observation ... 39

3.4.3 Questionnaire ... 39

3.4.4 Interview ... 41

3.4 Data Analysis ... 42

3.4.1 Pretest and Post Test ... 42

3.4.2 Class Observation ... 43

3.4.3 Questionnaire ... 43

3.4.4 Interview ... 44

3.6 Conclusion of the Chapter ... 44

CHAPTER IV TEACHING PROGRAMS 4.1 Phases of Study ... 45

4.2 Preliminary Phase ... 46

4.2.1 Searching for Teaching Materials ... 46

4.2.2 Trying Out the Pretest and Posttest Items ... 50

4.2.3 Administering Pretest ... 51

4.2.4 Inducting the Teaching Programs ... 53

4.3 Teaching Programs ... 54

4.3.1 Preparation (Before Instruction) ... 55

4.3.2Pre-Reading ... 55

4.3.3 While Reading ... 57

4.4 Post Teaching Phase ... 66

4.5 Conclusion of the Chapter ... 66

CHAPTER V: FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION OF DATA FROM TESTS, QUESTIONNAIRE AND INTERVIEW 5.1 Data from Tests……… 69

5.1.1 The Effect of the Teaching Programs on Reading Comprehension.. 69

5.1.2 The Effect of the Teaching Programs on Literal Comprehension Levels…..……… 72

5.1.3 The Effect of the Teaching Programs on Inferential Comprehension Levels……… 75

5.1.4 The Effect of the Teaching Programs on Evaluative Comprehension Levels……… 79

5.1.5 Summary of Discussion of Data from Tests ……… 82

5.2. Data from Questionnaire ……… 85

5.2.1 The Effect of STAD CL or DI on the Students’ Literal Comprehension Levels……….. 85

5.2.2 The Effect of STAD CL or DI on the Students’ Inferential Comprehension Level …….……….. 90

5.2.3 The Effect of STAD CL or DI on the Students’ Evaluative Comprehension Level……….. . 93

5.2.4 Summary of Discussion of Data from Questionnaire ……….. 97

5.3 Data from Interview……….. 99

5.3.1 The Students’ Responses toward STAD CL and DI……… 99

5.3.2 The Effect of STAD CL and DI on Literal Comprehension Level… 103 5.3.3 The Effect of STAD CL and DI on Inferential Comprehension ……105 5.3.4 The Effect of STAD CL and DI on Evaluative Comprehension ……108

5.3.5 Summary of Discussion of Data from Interview ………. 112

5.4 Conclusion of the Chapter ………

112

CHAPTER VI: THE CONCLUSION, LIMITATIONS AND IDEAS OF FUTURE RESEARCH 6.1 Conclusion ………. 113

6.2 Limitation of the Study………... 116

6.3 Ideas for Future Research .………. 118

BIBLIOGRAPHY ……….. 119

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2.1: Comprehension Levels and Skills ……… 14

Table 3.2: Research Design ……… 37

Table 4.3: The Phases of the Teaching Programs ………... 45

Table 4.4: Texts in the Teaching Programs ………. 47

Table 4.5: The Investigated Comprehension Levels and Skills ………... 49

Table 4.6: The Result of ANATESV.4 Analysis on the Try-Out Version of Both Pretest and Post Items ……… 50

Table 4.7: Descriptive Statistics of the Result of Pre-Test ……… 51

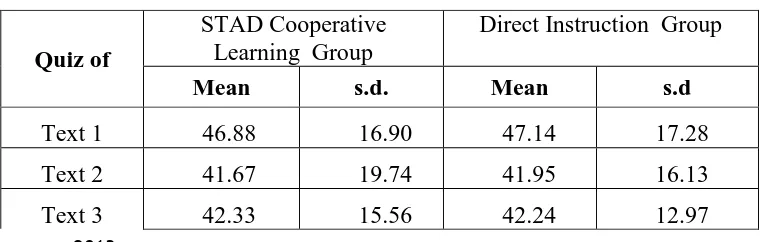

Table 4.8: Independent Samples Test of Pretest Scores of Class A, B and D …. 52 Table 4.9: The Mean Score of Quizzes ……… 64

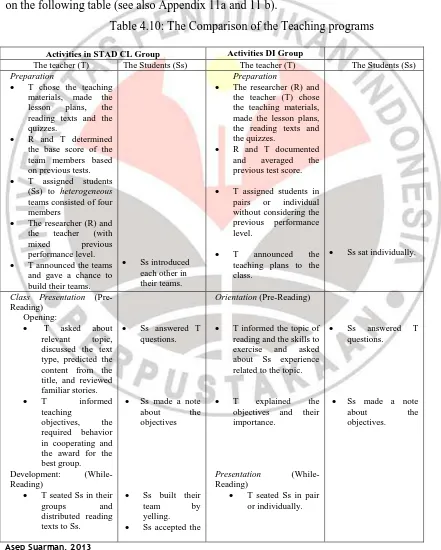

Table 4.10: The Comparison of the Teaching programs ……… 66

Table 5.11: Descriptive Statistics of Reading Comprehension Post Test Scores of both STAD CL and DI Groups ……… 69

Table 5.12: Independent Samples t-Test of the Reading Comprehension Scores of STAD CL and DI Groups ………. 71

Table 5.13: Descriptive Statistics of the Pretest and Posttest Scores on Literal Comprehension Level of STAD CL and DI Groups ………. 72

Table 5.14: Independent Samples t-Test of the Pretest and Post Test Scores on Literal Comprehension Level between STAD CL and DI Groups………. 74

Table 5.15: Descriptive Statistics of the Pretest and Posttest Scores on Inferential Comprehension Level of STAD CL and DI Groups ……… 75

Table 5.16: Independent Samples t-Test of the Pretest Scores on Inferential Comprehension Level between STAD CL and DI Groups ..… 77

Table 5.17: Descriptive Statistics of the Pretest and Posttest Scores on Evaluative Comprehension Level of STAD CL and DI Groups ………... 79

Table 5.18: Independent Samples t-Test of the Pretest and the Post Test Scores on Evaluative Comprehension Level between STAD CL and DI Groups …... 81

Table 5.19: The Comparison of Questionnaire Response between STAD CL and DI Groups on Literal Comprehension ……… 86

Table 5.20: The Comparison of Questionnaire Responses between STAD CL and DI Groups on Inferential Comprehension ……… 91

List of Charts

Chart 4.1: The Comparison of the Mean Scores and the Standard Deviation

between STAD CL and DI groups ………. 65

Chart 5.2 The Tendency of Mean Score of All Comprehension Levels ………… 82

List of Appendices

1. a. The Items of Pre-Test (Try-Out Version) b. The Items of Pre-Test (Pre-test Version) 2. a. The Items of Post-Test (Try-Out Version)

b. The Items of Post-Test (Pre-test Version) 3. a. An Example of Quiz Items

b. ANATES V.4 Analysis on Quiz #3

4. a. Observation Guidelines in STAD CL Group b. Observation Guidelines of DI Group

5. a. Condensed Observation Field note in the STAD CL Group b. Condensed Observation Field note in the DI Group

6. a. Questionnaire for STAD CL Group (not random) b. Questionnaire for DI Group (not random)

c. Questionnaire In Bahasa Indonesia for STAD CL Group (Random ) d. Questionnaire In Bahasa Indonesia for DI Group (Random )

7. The Microsoft Excel Analysis on the Result of Questionnaire Try Out. 8. a. STAD CL group Interview Guidelines

b. DI group Interview Guidelines

9. a. The Result of Questionnaire in STAD CL Group b. The Result of Questionnaire in DI Group

10.Reading texts for the Teaching Programs

11.a. An Example of Lesson Plans for STAD CL Group b. An Example of Lesson Plans for DI Group

12.a. ANATES V.4 Analysis on Pretest Items (Try-Out Version). b. ANATES V.4 Analysis on Post Test Items (Try-Out Version). 13.a. The Mark list of DI group

b. The Quiz Score Sheet of STAD CL group c. The Team Summary Sheet of STAD CL group 14.a. The Example of Certificate of Super Team

b. The Example of Certificate of The Best Student

15.a. The Comparison of Pretest and Post Test Scores on Literal Comprehension b. The Comparison of Pretest and Post Test Scores on Inferential Comprehension c. The Comparison of Pretest and Post Test Scores on Evaluative Comprehension 16. a. Condensed Version of Data from STAD CL group Interview

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION

This introductory chapter discusses the background and states the purposes of the

study and research questions. It further describes the significance of the study. Finally, it

outlines the structure of this thesis as a whole.

1.1 Background of the Study

Reading is a very important skill for both our life in general and language

learning in particular. For our life, it enables us to access written worlds of ideas (Hood et

al. 1996 p. 33), feelings as well as knowledge of the ages and vision of the future

(Alderson, 2000, p. x). It also facilitates us to gain access to science in various field of

study and to sense others’ feeling, attitude or behavior and to know what happened in the

past or what may happen in the future. For language learning, it can improve other general

language skills and help to think in the target language, enlarge vocabulary and improve

writing skill (Mikulecky and Jeffries, 1996 p. 1).

The importance of reading can be seen from the fact that the main part of national

examination in junior and senior high schools was to do with reading skill. It is to measure

students’ reading competence as being targeted by the national content standard (see

Depdiknas, 2005).

Various questions on English national exam are intended to assess students’

reading comprehension. The questions commonly deal with assessing the students’ skills

in getting explicit and implicit information, guessing words/phrase/clause meaning in

context, identifying main idea, communicative purpose of the text and the coda from a

story (BSNP, 2011; Hood et al. 1996 p. 44, see also Depdiknas, 2011). Such questions

basically are to inspect the students’ understanding or comprehension as a reflection of

their mind (Dorn and Soffos, 2005 p.2) after reading; as the essential goal (Brassell and

Rasinski 2008, p. 11) and as the product of reading (Alderson, 2000 p.5). Thus, the

difference of students’ comprehension levels is hopefully revealed through such questions. Some theorists assert that comprehension has some levels. Some academics

applied/assimilative/critical/evaluative levels (Heilman, 1961; Alexander, 1989 p. 125;

Muhamad, 1999; Alderson, 2000; Berry, 2005; Brasell & Rasinski, 2008 p. 17; Cuesta

College, 2011; see also Gunning, 2010). Others add two other levels: reorganization and

appreciation comprehension levels (Clymer 1968 in Pettit and Cockriel, 1974; Burnes,

1985 in Setiadi, 2010 p. 92; Brown, 1995; RIC Publication Staff, 1996; Snow, 2003;

Briskin, 2005). These levels of comprehension vary among readers.

Teaching reading comprehension levels with their own strategies or skills is quite

demanding for English teachers. Although comprehension can be taught directly (Fielding

and Pearson, 1994), its teaching requires teachers to be well-informed, creative, and

innovative (Depdiknas, 2007) about theories, approaches, methods, models, media or

findings. On the top of that, the teachers are required to have opportunities to experiment

the various approaches, models or methods (Arends and Kilcher, 2010).

Two of the models to teach reading are Student Teams-Achievement Division as

a cooperative learning (STAD CL) model (Slavin, 1989; 1995) and Direct Instruction (DI)

as a competitive model (Adams & Engelmann, 1996 in Kozloff, 2003; Moore, 2008;

Kozloff et al., 2001; Lang and Evan, 2006). Cooperative learning (CL) is a teaching

technique and philosophy employing small groups (Killen, 1998 p. 82; Jhonson et al.,

1993 p. 3 in McCafferty et al. 2006 p. 3; Lie 2004 p. 28) so that learners work together to

maximize their own and their peer’s learning and receive rewards based on their group’s

performance (Olsen and Kagan 1992; Richards and Rodgers, 2001 p. 192; Sach et al.,

2003). Competitive model is a teaching model wherein students individually compete to

be rewarded as the winner of the competition (Lie, 2004 p. 23-24).

Previous findings show that both STAD CL and DI have their own benefits for

teaching reading comprehension. On one hand, STAD CL can improve reading

comprehension (Slavin, 1995; Jhonson et. al, 2000; Wichadee 2005; Norman, 2005;

Jalilifar 2010) and achievement (Jhonson et al, 2000). On the other hand, DI is a good

model for teaching reading comprehension providing students specific skills or strategies

that are necessary for reading proficiency (Moore, 2008; Gregory et al., 2005; Kozloff,

2003); could raise student achievement in reading (Iver, et al. 2003) and was an

Considering the benefits of STAD Cooperative Learning and Direct Instruction

above, this study attempts to shed light on the effects of STAD CL and DI on students’

reading comprehension in general and comprehension levels in particular.

1.2 The Purpose of the Study

This study is intended to investigate how STAD cooperative learning (STAD CL)

and Direct Instruction (DI) are implemented in a classroom, to find out which instruction

is more effective in improving reading comprehension in general and comprehension

levels in particular, and what the students’ responses are to STAD CL or DI.

1.3 Research Questions

Based on the purposes of the research above, this study attempts to answer the

following research questions:

1. How cooperative learning (STAD CL) and direct instruction (DI) are implemented in

the classrooms?

2. Which instruction, STAD CL or DI, is more effective in improving the students’

reading comprehension?

3. Which instruction, STAD CL or DI, is more effective in improving each of the

students’ reading comprehension level?

4. What are the students’ responses to STAD CL or DI?

1.4Definition of the terms

There are many terms used in this study, so to add precision to this study

(Cresswell, 1994 p. 106; 2003 pp. 142-3), it is necessary to clarify the terms. Below are

listed the operational definition of the used terms.

- Reading is defined as the interaction between a reader and a text to combine information from the reader’s background knowledge, his/her purpose and the text to

build meaning (Mikulecky, 1990 p. 2; Anderson in Nunan, 2003; Snow, 2002, p. 2 see

also Alexander, 1989).

- Reading comprehension is the process of simultaneously extracting and constructing meaning through interaction and involvement with written language (Snow, 2002 p.

xiii). In this study, the term reading and reading comprehension are treated

- Comprehension levels are the levels of understanding about the author’s intended message of a text (Haris et al. 1981 in Setiadi, 2010 p. 88). In this case, only three

levels are investigated: literal, inferential and evaluative (Alexander, 1989 p. 125;

Muhamad, 1999; Berry, 2005; Brasell & Rasinski, 2008 p. 87).

- Student Team Achievement Division (STAD) in this study refers to the cooperative learning models consisting of class presentation, teams, quizzes, individual

improvement and team recognition (Slavin, 1995 p. 71).

- Cooperative Learning (CL) in this study refers to a teaching procedures employing small team so that learners work together to maximize their own and their peer’s

learning and receive rewards based on their team’s performance (Killen, 1998 p. 82;

Jhonson et al., 1993 in McCafferty et al. 2006 p. 3; Olsen and Kagan 1992; Richards

and Rodgers, 2001 p. 192; Sach et al., 2003).

- Direct Instruction (DI) refers to a pattern of teaching that consists of the teacher’s explaining a new concept or skill to students, having them test their understanding

under teacher direction in controlled practice, guided practice and independent practice

(Binder & Watkins, 1990; Killen, 1998 p. 2; Stein et al., 1998; Kozloff, 2003 Joyce,

2011).

- Responses in this study refer the students’ opinion about the effect of STAD CL or DI on their reading skills in each comprehension level and when they were facilitated by

the instructions.

1.5 Significance of Study

This study is expected to provide its significance at least in three points of view,

referring to Creswell (1994 p. 111; 2003 p. 149).

Theoretically, this study may add empirical support to existing theories, literature

and scholarly research findings of STAD cooperative learning and direct instruction (DI)

in teaching reading comprehension.

Practically, the results of this study may help to clarify the benefits of applying

STAD CL and DI in teaching reading so that more teachers can replicate the study and

apply the CL or DI in their daily teaching to improve students’ comprehension.

Professionally, this study may encourage the teachers in the research site or in the

regency to apply STAD CL and DI in their teaching; and promote the theory-based

1.6 Structure of Thesis

This thesis is organized into six chapters. Chapter I presents the background, the

purpose, the research questions, significance of the study and the structure of the thesis.

Chapter II discusses theoretical reviews on reading comprehension, STAD Cooperative

Learning and Direct Instruction with their recent research finding. Chapter III describes

the methodology for collecting and analyzing the data, including design, participants, data

collection techniques, and data analysis. Chapter IV discusses the teaching programs as

the implementation of both STAD CL and DI with the result of observation and quizzes.

Chapter V presents the findings and discussion of the obtained data from tests,

questionnaire and interview. Finally, Chapter VI presents the conclusions and limitation of

CHAPTER III: RESEARCH METHOD

The previous chapter has described the theoretical background of the study. It

discusses literature review about reading comprehension, comprehension levels, STAD

Cooperative Learning (STAD CL) and Direct Instruction (DI) along with the principles,

procedures and their weaknesses.

This chapter provides the information about the methodology of the research

including the research questions, the setting and participants of the study, the design, data

collection methods and data analysis. The conclusion ends this chapter.

3.1 Research Setting and Participants

This research was undertaken in a junior high school in Serang Regency, Banten

Province. This site made the research more feasible and suitable in terms of time, mobility

and skills (McMillan and Schumacher 2001 p. 432). Firstly, it was located in the same

town as the researcher. This could ease the researcher in managing time and cost in

running the study. Secondly, based on the researcher’ previous observation, the English teacher had the necessary skill to implement the teaching procedures. Thirdly, the

researcher had good access to the site, since the researcher was one of teaching personnel

in the site.

The participants of the study were 64 students of eight graders which were

divided into two groups each of which consist of 32 students. They were selected based on

the historical factors and pre-existing ability (Hatch and Farhady, 1982 p. 7; Mc.Millan

and Schumacher, 2001 pp. 186-7). In terms of historical factors, to follow Hatch and

Farhady, the students in both groups had relatively the same language learning experience.

Previously, they had been studying English for more than 1.5 year the same teacher and

the same materials. No one of them had ever joined any English course. In such a time

span and experience, they were assumed to have adequate knowledge background which is

beneficial for their reading (Alderson, 1999). This condition helped the researcher

assumed that the participants had similar prior knowledge (Hatch and Farhady, 1982 p.7).

In addition, they were also chosen based on the homogeneity of pre-existing

were statistically homogenous, no significant difference on their pretest scores. In other

words, the two groups have approximately similar pre-existing reading comprehension

ability (Hatch and Larazaton, 1991 pp. 261-3). The selected groups, then, were assigned as

experimental and control groups by flipping a coin (Hatch and Farhady, 1982 p. 19).

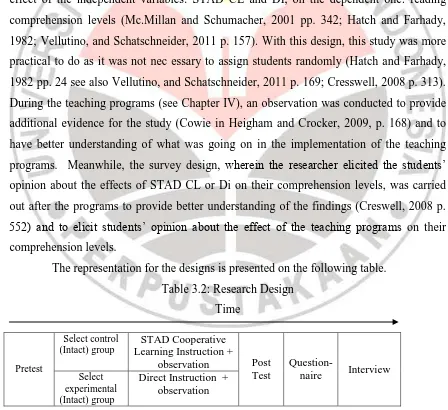

3.2 Research Design

This study employed triangulation mixed method design (Creswell, 2003 p. 213;

2008 pp. 558-9 see also Mc.Millan and Schumacher, 2001 p. 542; Darlington and Scott,

2002 p. 123). The design was the combination between two designs: quasi-experimental

and survey designs (Hatch and Farhady, 1982; Mc.Millan and Schumacher, 2001 pp.

32-4). The quasi-experimental design was employed since this study compared the causal

effect of the independent variables: STAD CL and DI, on the dependent one: reading

comprehension levels (Mc.Millan and Schumacher, 2001 pp. 342; Hatch and Farhady,

1982; Vellutino, and Schatschneider, 2011 p. 157). With this design, this study was more

practical to do as it was not nec essary to assign students randomly (Hatch and Farhady,

1982 pp. 24 see also Vellutino, and Schatschneider, 2011 p. 169; Cresswell, 2008 p. 313).

During the teaching programs (see Chapter IV), an observation was conducted to provide

additional evidence for the study (Cowie in Heigham and Crocker, 2009, p. 168) and to

have better understanding of what was going on in the implementation of the teaching

programs. Meanwhile, the survey design, wherein the researcher elicited the students’ opinion about the effects of STAD CL or Di on their comprehension levels, was carried

out after the programs to provide better understanding of the findings (Creswell, 2008 p. 552) and to elicit students’ opinion about the effect of the teaching programs on their comprehension levels.

The representation for the designs is presented on the following table.

Table 3.2: Research Design

Time

Pretest

Select control (Intact) group

STAD Cooperative Learning Instruction +

observation Post Test

Question-naire Interview

Select experimental (Intact) group

Direct Instruction + observation

Table 3.2 above shows a pretest (see Section 3.3.1) preceded the research, then

experimental and control groups were selected on the basis of the pretest. After that, the

teaching programs (see chapter IV) were conducted. After the programs ended, a post test

(see Section 3.3.1), questionnaire (see Section 3.3.2) and interview (see Section 3.3.4)

were administered.

3.3. Data Collection Methods

This section discusses data collection methods including pretest and post-tests,

observation, questionnaire and interview.

3.3.1 Pretest and Posttests of Reading Comprehension

As mentioned in the research design (see Section 3.1), to gather the data about the students’ achievement in reading comprehension, a pencil and paper tests (Mc.Millan and Schumacher, 2001 pp. 250-7) were administered. The tests were pretest, posttest and

quizzes. The pretest (see Appendix 1a and 1b for the items) was aimed to see and compare

the existing ability of the groups involved in the study. It was done before the teaching

programs were conducted. The posttest (see Appendix 2a and 2b) was conducted after all

teaching programs were done. It was conducted to see the effect of the teaching programs

on the students’ comprehension levels. In addition, in the end of every treatment, a quiz

(see Appendix 3a,b for the example of the items) was also administered to assess the

students’ comprehension of the text learned.

In the tests, multiple choice items were chosen for several considerations. Firstly,

they are suitable items for testing reading as receptive skill (Brown, 2005 p. 47). Secondly,

they are selected due to its objectivity and its practicality. Multiple choice items are more

objective since there will be less scoring mistakes than other test formats (Brown, 29).

They are also easy to administer and can be scored quickly (Brown, 2005 p. 47). It can be

administered and scored in shorter time than that of other formats. It has simplicity in

analyzing the test validity and the test reliability (Brown, 2001 p. 386; 2004 p. 20).

Some test items were taken from available reading tests and some others were

constructed by the researcher. They were adopted from the items of previous national

examinations (Balitbang – Kemendiknas, UN, 2011) or its try out. The selection and the construction of the items were based on the comprehension levels to measure and their

The items were segmented into three sections, according to comprehension

levels: literal, inferential and evaluative (see Section 2.1.5). For literal level, the test items

required students to scan for specific information; read for detailed explicit information;

guess the meaning of unfamiliar word from context, and identify or locate information.

For inferential comprehension, test items were related to identifying or reading for main

ideas and pronominal reference; reading for implicit meaning; outlining logical

organization of text and drawing inferences in the content. For evaluative comprehension,

test items were to assess students’ ability in recognizing a writer’s purpose, attitude, tone and emotion in the text and identifying the characteristics of characters; and analyzing the

(generic) structure of the text (see Section 2.1.5 for detail).

The test consisted of thirty items with two genres of texts: recount and narrative

(see Martin and Rose, 2008; Anderson and Anderson, 1997). These genres were also as

the material in the teaching programs (see Chapter IV). They were chosen since they had potential to challenge all levels of students’ comprehension, according to Barret Taxonomy of reading comprehension levels (www.campbellps.det.wa.edu.au; Clymer

1968 in Hudson, 2007 and Pettit and Cockriel, 1974; Berry, 2005). The pretest items

included two recounts, about unforgettable experience and holiday, and two narratives

about folktale and legend. The posttest ones were also composed of five texts: two

recounts about lost dog and unforgettable experience, and three narrative texts about fables

and legend.

To enhance the validity of the test items, some efforts were made. To maintain the

content validity (Hatch and Farhady, 1982 pp. 250-5; Hughes, 2003 p. 26: Brown, 2005 p.

221), the construction of the test items were referred to reading comprehension levels,

basic competence of the content standard (Depdiknas, 2006) as well as graduation criteria

of English national examination of Junior High School (Depdiknas, 2011). To support the

face validity, the items were constructed in such a way that they had similar length of

options; the same number of options and similar organization (Hughes, 2003 p. 33). At

last, to uphold the criterion validity (Hughes, 2003 p. 27), the results of the (pre- and post)

tests were compared with those of the previous tests.

To ensure the reliability and the difficulty levels, the test items were tried-out and

subsequently modified (Hatch and Farhady, 1982 p. 253). The items were tried out to

another group of students not involved in the study. This try-out was intended to see bad

50% of medium and 25% of difficult items (Hughes, 2003; Brown, 2005; Arikunto, 2009,

p.207). There were 40 items on the try-out but only 30 items were selected for the tests.

The selection was based on difficulty and comprehension levels. Further discussion of the

try-out of the items is discussed in Chapter IV Section 4.2.2.

3.3.2 Class Observation

Observation was carried out to provide additional evidence for the study (Cowie

in Heigham and Crocker, 2009, p. 168) and to get to know first-hand information about

social process in a naturally occurring context (Silverman, 1993). In this case, the

researcher acted as a participant observer (Creswell, 2001 p. 222; see also Cowie in

Heigham and Crocker, 2009 p. 166) wherein he got involved in helping the teacher plan

the teaching programs, prepare reading texts, implement the procedures of the programs

and evaluate them. This observation aimed to have better understanding of what was going

on in the implementation of the teaching programs and how the teacher as well as students

participated in the activities.

To provide sharper focus of data collection (Nunan, 1992 p. 98), in this study, the

researcher applied structured observation wherein specific categories to observe had been

determined previously (Mc.Millan and Schumacher, 2001 pp.40-1; see also Nunan, 1992

p. 96). The categories included the principles and the procedures of the teaching programs.

The observation sheet for STAD CL group (see appendix 4a) were adapted from

Furtwengler (1992; see also Leighton in Cooper, 1990 pp. 330-331). It contained some

indicators of effective cooperative learning related to classroom organization, classroom

management, presentation content, group facilitation, monitoring and lesson summary. In

the meantime, the observation sheet for DI group (see appendix 4b) were adapted from

observational guideline of direct instruction from education.byu.edu. It included direct

instruction procedures consisting of the indicators of opening, modeling, guided practice,

independent practice and closing phases.

When the observation was being conducted, the researcher also made field notes

(see Appendix 5a and 5b, for the example). The notes about what the teacher as well as the

students did in the teaching programs.

3.3.3 Questionnaire

After all the teaching programs were done, a questionnaire (see Appendix 6a -

anonymity of respondents (Mc.Millan and Schumacher, 2001 p.257). In this study, the questionnaire surveyed the students’ opinion about the effect of STAD CL or DI on their comprehension levels. It was aimed to provide a numeric information, data or trend about the students’ opinions on the teaching programs (Mc.Millan and Schumacher, 2001 p. 304; Cresswell, 2008 p. 61; 2002 pp. 154; 1994 pp. 127-130). The questionnaires were

distributed to both groups after the posttest.

The questionnaire was developed following the guideline from Oppenheim (1982);

Barbie (1998) in Mc Millan and Schumacher (2001 p. 258) and Dornyei (2002). The items

were arranged in Likert Scale, in the four gradations starting from ‘strongly agree’, ‘agree, ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’ (Mc.Millan and Schumacher, 2001 p.262; Dornyei, 2002 p. 27; Creswell, 2008 p. 176;). The respondents were only required to check the

place on the scale that best reflect their belief or opinion about the statements (Mc.Millan

and Schumacher, 2001 p.262).

The questionnaire contained 18 statements about the reading skills related to the

three levels comprehension: literal, inferential and evaluative (see Appendix 6a and 6b).

They consisted of nine positive and nine negative ones to avoid a response set in which the

respondents mark only on side of the scale (Dornyei, 2002 p. 43). They were randomly

arranged to make sure the students’ consistency, real perception, and to prevent guessing (Sugiyono, 2005; Oppenheim, 1982). They were written in Bahasa Indonesia to make it

more comprehensible for the students and to avoid misunderstanding.

Further, to enhance the effectiveness and comprehensibility of questionnaire, it

was validated, coded and pilot-tested (Mc Millan and Schumacher, 2001 p. 267; Dornyei,

2002 pp. 53-55; Creswell, 2008 p. 402;). Before being tried out, it was validated by

having others to read and to give feedback whether it was vague or incomprehensible. It

was also coded by giving the initial of comprehension levels, the number of statements of

each level and positive (+) or negative (-) symbols. It was also pilot-tested to a group of

students not involved in the study to see their capability of completing the questionnaire

and their reaction.

In the pilot testing, it was found that generally all statements in the questionnaire

were comprehensible for the students. But, the term ‘pembelajaran langsung’ (Direct Instruction) needed describing since the students were not familiar with the terms. Then, to

follow Juliandi (2007), the result of the pilot test was statistically analyzed via Microsoft

Correlation. It was found that most statements (73%) were statistically valid to use. And,

in terms of internal consistency, the score of split-half reliability (Brown, 2005, p. 177;

Hughes, 2003, p. 40) between positive and negative statements was 0.97. It meant that the

questionnaire had good reliability. The score was close to the perfect reliability, that is,

one (1.00).

3.3.4 Interview

In addition to the previous data collections, interview was conducted to verify,

extend, elaborate or explain the data collected (Creswell, 2008 p. 552; McMillan and

Schumacher, 2001 p. 444). In this case, it was intended to elicit the students’ opinions about the effects of STAD CL or DI on their learning reading strategies. It was done after

the analysis of the posttest score.

The interview was a directive (Richard, 2003 p. 51) or structured one (Nunan,

1992 p. 149) wherein specific topics/agenda were totally predetermined (see also

McMillan and Schumacher, 2001 p. 444). Its form was focused group interview. It was to

encourage a sense of divergent opinion (Krueger and Morgan, 1993 p. 17-18 in Emilia

2005 p. 245), to collect shared understanding from several individuals of students, to take

the pressure off the participants (Darlington and Scott, 2002 p. 62) and to provide

welcoming condition so that they were not hesitant to talk (Creswell, 2008 p. 226).

Twelve students from each group were purposefully chosen (Creswell, 2008 p. 214;

McMillan and Schumacher, 2001 pp. 400-1) from low, middle and high achievers in the

post tests.

Interview guideline (see Appendix 8a and 8b) was used when interviewing. It

consisted of some questions to elicit students’ opinions about the effect of the teaching programs. The questions were related to the advantages of STAD cooperative learning

(STAD CL) or Direct Instruction (DI) for their learning and their comprehension levels.

The questions were segmented into three parts: introduction, core part and winding down

or closing (Ritchie and Lewis, 2003 p. 114). In the introduction, to follow Ritchie and

Lewis, easy, opening questions were asked. The core part included deeper and more

specific questions. Finally, suggestive questions were delivered in the closing.

The number of questions in the group interviews was at least 16 questions. They

core ones were related to their impression and experience in implementing the instructions

especially the difference between the STAD CL or DI models and those that the students

had experienced before, the facilitation of the models to their learning and to their

comprehension levels. The closing ones consisted of a question relevant to students’ suggestions on the application of the learning models in the future.

3.4 Data Analysis

In this section, data analyses are discussed. The analyses include the four data

collection techniques employed: tests, class observation, questionnaire and interview.

3.4.1 Pretest and Posttest

ANATES V.4 (version 4) and SPSS V.15 software were utilized to analyze the

result of the pretest and the posttest. ANATES V.4 (KarnoTo and Wibisono, 2003) could

automatically analyze the reliability, the level of difficulty, discrimination index and distracters’ quality of the items. It helped researcher to identify the quality of the test items quickly and appropriately. The second one, SPSS (Nie and Hull,1968) could easily

analyzed quantitative data just by clicking the menu. It was to statistically analyze the

difference of means among data through independent t-test and non-parametric test.

The procedures of analyzing the data from the tests were as follows.

1. Data Entry and the Analysis via ANATES software

Firstly, the coded names of participants, the answers and the key answers were entered

into ANATES V.4. Then, the correct answers were scored, one correct answer got one

score. The sum of correct answers was divided by the number of the items to have

percentage point. Finally, the reliability, the level of difficulty, discrimination index and distracters’ quality of the items were analyzed automatically, just by clicking the menu.

2. Independent t-test analysis via SPSS V.15

The total scores obtained from ANATES V.4 were then statistically analyzed through

the SPSS V.15 software. This analysis was intended to see which teaching program,

STAD CL or DI, is more effective in improving the students’ comprehension in general. It compared the mean scores of total scores of both groups. Since they were

two independent groups, independent t-tests were chosen (Hatch and Farhady, 1982

pp. 111-4, Hatch and Lazaraton, 1991 pp. 258-262; Kinnear and Gray, 1994 p. 86). It

normal distribution since the participants were more than 30 students (Hatch and

Farhady, 1982 p. 98).

3. SPSS independent t-test on every level of Comprehension

Further, to see the improvement of the scores of both STAD CL and DI groups on

every level of comprehension, SPSS descriptive statistics and independent t-test were

carried out. For the comparison, the students’ answers on the raw data (data mentah) of ANATES.V4 were categorized into three levels of comprehension: literal,

inferential and evaluative, each of which consisted of 10 items. Such number of items

was appropriate enough to have descriptive statistics and inferential one (Kinnear and

Gray, 1994 p. 83). This analysis was intended to compare the significance of the

difference between the mean score both groups on every level of comprehension.

Since the data was the same as mentioned previously, independent t-test was run.

Then, the result of the analysis was described adequately.

3.4.2 Class Observation

The data from observation consisted of researcher’s field notes (Creswell, 2008 p. 224) and the result of reading comprehension quizzes. The analysis of the data was

conducted during and after the data collection (Miles and Huberman, 1994 p. 10). The

obtained data then were analyzed and described adequately, all of which will be presented

in Chapter IV together with the teaching programs. Specifically the data comprised mainly

of the teacher’s activities and the students’ response on the procedure of the teaching programs. The data obtained were presented in a condensed body of information (Emilia,

2005 p. 86) (see Appendix 5a and 5 b) which will be discussed in Chapter IV, together

with the teaching programs.

3.4.3 Questionnaire

The data from the questionnaire were analyzed in several steps. Firstly, the

questions or the statements in the questionnaires were categorized into the central themes

(Alwasilah, 2000 p. 160; Cresswell, 2008 pp. 251): the levels of comprehensions. Then,

simple computation and percentage were conducted. The results were tabulated,

statistically analyzed and interpreted adequately.

In analyzing the result of the questionnaire, the scores between the positive and

negative statements were reversed (Dornyei, 2002 p.43). For positive statements, to

meanwhile for negative ones, ‘strongly agree’ was scored one and ‘strongly disagree’ was scored four (see also Creswell, 2008 p. 184). All respondents’ checks were presented in recapitulation table (see Appendix 9a and 9b). In the end, SPSS.V15 analysis: non

parametric Wilcoxon signed rank was done. The result of the analysis will be presented in

Chapter V.

3.4.4 Interview

The data from interview were analyzed through several steps. Firstly, recorded data

were transcribed. In transcribing the data, the participants were coded to protect their

privacy (Silverman, 1993). To follow Miles and Hubberman (1994 pp. 10-11), then,

inappropriate or non relevant data were reduced. After that, the data were categorized into

central themes which became the main concern of this study (Cresswell, 2008 pp.

251-261); they are the participants’ impression on STAD CL or DI and their effects on their comprehension levels. The obtained data were presented in the condensed body of

information (Emilia, 2005 p. 86) (see Appendices 16a and 16b).

3.5 Conclusion of the Chapter

This chapter has provided the information about the methodology of the research

including the setting, the participants and the designs of the study. It also discusses the

data collection techniques and analyses for the study including tests, observation,

questionnaire and interview.

The following chapter discusses the teaching procedures as the teaching programs

for the study. It describes the steps of STAD CL and Direct Instruction (DI) in teaching

CHAPTER IV: THE TEACHING PROGRAMS

The previous chapter describes the methodology of the research including the

setting, participants, design of the study, data collection and data analysis.

This chapter depicts the stages of the study, the teaching programs and the

observed students‟ responses to them. It aims to answer the first research questions: how

to implement STAD CL or DI in the classroom. It sets out the phases of the study and

compares the similarities and the dissimilarities of the teaching procedures between the

Student Team Achievement Division (STAD) Cooperative Learning and Direct

Instruction. In presenting the phases, the students‟ responses obtained from observation

sheet (see Appendices 4a and 4b) and the researcher‟s field notes (see Appendices 5a and

5b) are also included in the description.

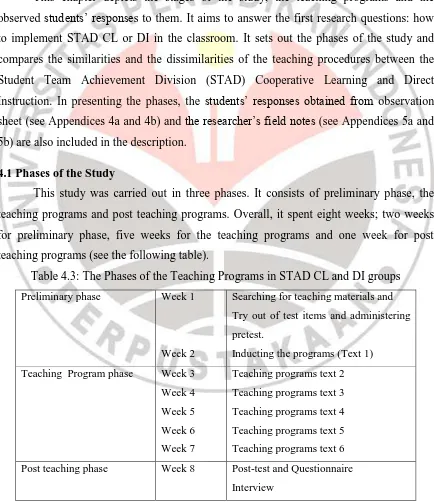

4.1 Phases of the Study

This study was carried out in three phases. It consists of preliminary phase, the

teaching programs and post teaching programs. Overall, it spent eight weeks; two weeks

for preliminary phase, five weeks for the teaching programs and one week for post

teaching programs (see the following table).

Table 4.3: The Phases of the Teaching Programs in STAD CL and DI groups

Preliminary phase Week 1

Week 2

Searching for teaching materials and

Try out of test items and administering

pretest.

Inducting the programs (Text 1)

Teaching Program phase Week 3

Week 4

Week 5

Week 6

Week 7

Teaching programs text 2

Teaching programs text 3

Teaching programs text 4

Teaching programs text 5

Teaching programs text 6

Post teaching phase Week 8 Post-test and Questionnaire

Summarized from the stages of this study

4.2 Preliminary Phase of Teaching Programs

In this phase, the researcher conducted three activities: i) searching for teaching

materials; ii) trying out the pretest items; iii) administering the pretest and iv) inducting

the teaching programs. Each activity will be delineated below.

4.2.1 Searching for Teaching Materials

The teaching materials for this study included reading texts with their practices

(see Appendix 10), quizzes (see Appendix 3) and lesson plans (see Appendices 11a and

11b). Overall, there were six reading texts utilized in this study. As mentioned before (see

Section 3.4.1), the texts consisted of two genres: recount and narrative texts (see Martin

and Rose, 2008; Anderson and Anderson, 1997). These texts, Martin and Rose describe,

comprise a series of interrelated episodes that include goal-directed actions and causally

related events. The ability to comprehend those genres can be a foundation for later

reading comprehension skills since the students have to monitor their understanding,

generate inferences, identify the key points, and understand causal relations (Paris & Paris,

2003 in Broek et al. 2009 p. 112). In addition, these genres had a potential to challenge all

levels of students‟ comprehension (Barret Taxonomy in Clymer, 1968 in Pettit and

Cockriel, 1974 p.64 in Hudson, 2002; Berry, 2005; Setiadi, 2012, see also

www.campbellps.det.wa.edu.au).

The teaching materials and their assessment in both STAD CL and DI groups were

similar. The similarities were to maintain the internal validity of the research (Hatch and

Farhady, 1982 p. 7; Hatch and Larazaton, 1991 pp. 33-41). Both groups used the same

reading texts (see Appendix 10) for the teaching and the same items for the quizzes/tests.

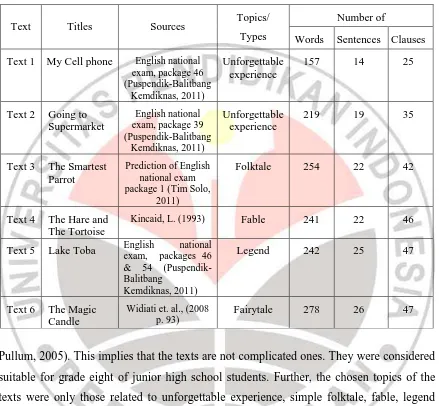

The texts (see Table 4.4) were selected from several resources. The selection, to

follow Hudson (2007, p. 34; see also Grabe and Stoller, 2002 p. 33; Hedgcock and Ferris,

2009 p. 29), was based on the length of the passage (the number of words), the complexity

of grammar and content familiarity. The texts were adapted from electronic book by

Widiati et. al. (2008); the text on the items of previous national examinations (Balitbang –

Kemendiknas, UN, 2011) or other resources like the internet, English fables, legend.

Table 4.4 below shows the profile of the texts. It presents that the selected reading

the comprehension. The number of clauses is twice as many as sentences, meaning that

most sentences consisted of simple clauses, rather than complex ones (Huddleston and

Table 4.4: Texts in the Teaching Programs

Text Titles Sources Topics/

Types

Number of

Words Sentences Clauses

Text 1 My Cell phone English national exam, package 46

Pullum, 2005). This implies that the texts are not complicated ones. They were considered

suitable for grade eight of junior high school students. Further, the chosen topics of the

texts were only those related to unforgettable experience, simple folktale, fable, legend

and fairy tale, which were considered familiar for the students and within their background

knowledge (Sadeghi, 2007 p. 199; see also Vaezi, 2006).

The examples of the texts are as follows.

The example of Recount text:

My Cell Phone

That Sunday evening I felt very tired after hanging out the whole day with my friends at the mall. As soon as I arrived home, I hung my jacket on a hanger and took a rest. About an hour I took a nap, and then I took bath.

Adapted from Puspendik - Balitbang – Kemendiknas, (UN), 2011.

The example of Narrative text:

The Hare and The Tortoise

One day, The Hare and The Tortoise were arguing in the forest.

“I could beat you in a race, any day,” The Hare said to The Tortoise. “Hmmm,” said The Tortoise.”Maybe you could.”

“I could!” said The Hare.”My legs can run much faster than yours.” “That doesn‟t mean you would win a race,” said The Tortoise “Then, we should have a race,” said The Hare.

So the race was arranged, “I will wait for you at the finishing post, “shouted The Hare to The Tortoise, and he sped off.

“May be,” said The Tortoise, and he plodded slowly after The Hare. “This is easy,” said The Hare to himself as he raced along.

After a while, The Hare stopped and looked behind him. There was no sign of The Tortoise. As it was very hot, The Hare sat under a tree, in the shade. He thought there was plenty of time, and The Tortoise would never catch up with him. The Hare closed his eyes.

After a while The Tortoise reached the tree. He saw The Hare sleeping under it. The Hare didn‟t see The Tortoise plodding by.

Later, The Hare woke up and raced off to the finishing post. He couldn‟t believe it when he saw The Tortoise

waiting for him.

“You must have cheated!” said The Hare to The Tortoise.

“Certainly not!” said The Tortoise. “While you were sleeping, I carried on the race”

Adapted from Aesop Fables

The reading texts were presented together with the exercises (see Appendix 10) to

provide students with practice and self assessment (Slavin, 1995, p. 95; see also Leighton

in Cooper, 1990 p. 328). To follow Slavin, the number of items/exercises was about ten to

fifteen items in the form of completion and short answer. As Slavin suggested, the reading

texts were distributed to every pair of students to ease their reading. They were distributed

right before the instruction. It was intended to maintain the equivalence of knowledge

background (Brown, 2001; Barnet, 1981; Vaezi, 2006; Hudson, 2002), in the sense that

the students read the texts for the first time when the teaching programs were being

implemented.

The reading texts (see Appendix 10) for both STAD CL and DI groups included

the exercises. They consisted of a text followed by several questions challenging their

literal, inferential and evaluative comprehension levels. The questions exercised and assessed the students‟ comprehension skills. As mentioned in the previous chapter, the comprehension levels and skills were to follow Barret taxonomy of comprehension

(Clymer, 1968 in Pettit and Cockriel, 1974 p. 64; in Hudson, 2002; Berry, 2005; Setiadi,

comprehension levels and skills. The selection of the skills, as mentioned in previous

chapter (see Section 2.1.5), was due to the feasibility of the study.

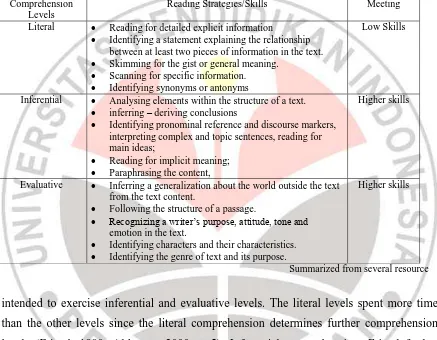

Further, to exercise those three levels of comprehension, the practices were

segmented into two meetings. In the first meeting, the questions were aimed to practice of

lower level reading skills to gain literal comprehension, and in the second one they were

Table 4.5: The Investigated Comprehension Levels and Skills

Comprehension Levels

Reading Strategies/Skills Meeting

Literal Reading for detailed explicit information

Identifying a statement explaining the relationship between at least two pieces of information in the text.

Skimming for the gist or general meaning.

Scanning for specific information.

Identifying synonyms or antonyms

Low Skills

Inferential Analysing elements within the structure of a text.

inferring – deriving conclusions

Identifying pronominal reference and discourse markers, interpreting complex and topic sentences, reading for main ideas;

Reading for implicit meaning;

Paraphrasing the content,

Higher skills

Evaluative Inferring a generalization about the world outside the text from the text content.

Following the structure of a passage.

Recognizing a writer‟s purpose, attitude, tone and

emotion in the text.

Identifying characters and their characteristics.

Identifying the genre of text and its purpose.

Higher skills

Summarized from several resource

intended to exercise inferential and evaluative levels. The literal levels spent more time

than the other levels since the literal comprehension determines further comprehension

levels (Friend, 1980; Alderson, 2000 p. 5). Inferential comprehension, Friend further

claims, is dependent on literal one and higher order skill can only grow from competence

in the lower order skills. Literal comprehension is needed to be blended with prior

knowledge, intuition, and imagination for conjecture or to make hypotheses (Pennel,

2002) to get inferential and evaluative levels. It was also necessary to spend time more to

discuss vocabularies and grammatical expressions available on the texts to activate and

provide more background knowledge (Hudson, 2002 p. 143; Hedgcock and Ferris, 2009 p.

163; Setiadi, 2012). As Nunan (1999 p. 259) claims, what the students already know,

In addition, quizzes (see Appendices 3a and 3b) were also administered in the

study. The quiz, according to Slavin (1995), is a short test in the form of multiple choice

items to save the testing time. The quiz consisted of twelve items consisting of four

questions for every levels of comprehension. So, the items were 12 overall.

Above all, to provide rhythm to a course of study (Brown, 2001 p. 149) and

facilitate the participant teacher in implementing the programs, pre-established lesson

plans (see Appendices 11a and 11b) were provided. They were functioned as the

guidelines for participant teacher and students in implementing the teaching programs

(Feez and Joyze, 1998 p. 2 in Emilia, 2005 p. 115). They were made in Bahasa Indonesia

to be more comprehensible for the teacher. It covered the objectives of the lesson, the

material, the teaching procedures and evaluation (Brown, 2001 pp. 149-151; Lang and

Evans, 2006 pp. 218-220).

4.2.2 Trying Out the Pretest and Posttest Items

The try-out of the items was intended to make sure that all the test items, meet the

requirements in terms of their validity and reliability (Hatch and Lazaraton, 1991 p. 529;

Brown, 2005; Hughes, 2003). It was carried out by having another group of students, not

involved in the study, to answer test items.

After the try out (see Table 4.6) the reliability, the difficulty levels and the

discrimination index were obtained. The reliability of the pretest items (try-out version)

was 0.71 and the posttest was 0.75 indicating that both items were reliable enough to be

used in this study (Hughes, 2003 p. 39; Brown, 2005 p. 175).

As seen on Table 4.6, the difficulty levels of the pretest items (try-out version) consisted

of 32.5% difficult, 52.5% medium and 15% easy items and that of the posttest ones was

42.5% difficult, 42.5% medium and 15% easy items. These percentages meant that the

difficulty levels were balanced enough (Brown, 2005 p. 69). The discrimination index of

the items was relatively good. More than 75 % of the items exceeded 0.20 discrimination

index, which means that the items could discriminate the low and high level students

(Hughes, 2003 p. 226; Brown, 2005 p. 69). Additionally, bad distracters on several items

were modified and ten items in the tried-out version which either was too difficult or too

easy were eliminated in the test version.

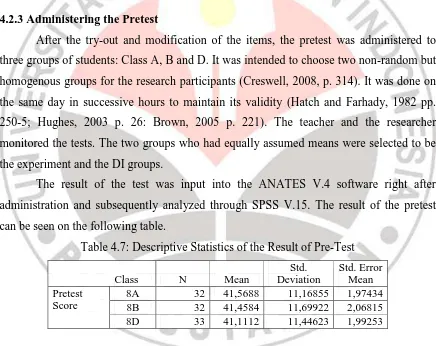

4.2.3 Administering the Pretest

After the try-out and modification of the items, the pretest was administered to

three groups of students: Class A, B and D. It was intended to choose two non-random but

homogenous groups for the research participants (Creswell, 2008, p. 314). It was done on

the same day in successive hours to maintain its validity (Hatch and Farhady, 1982 pp.

250-5; Hughes, 2003 p. 26: Brown, 2005 p. 221). The teacher and the researcher

monitored the tests. The two groups who had equally assumed means were selected to be

the experiment and the DI groups.

The result of the test was input into the ANATES V.4 software right after

administration and subsequently analyzed through SPSS V.15. The result of the pretest

can be seen on the following table.

Table 4.7: Descriptive Statistics of the Result of Pre-Test

Class N Mean

Std. Deviation

Std. Error Mean Pretest

Score

8A 32 41,5688 11,16855 1,97434

8B 32 41,4584 11,69922 2,06815

8D 33 41,1112 11,44623 1,99253

The descriptive statistics above shows that the mean score of Class A (41.56) and

B (41.66) were almost the same but the standard deviation of Class A (11.16) is quite

different from that of Class B (11.51). This means that the pre-existing ability of Class A

and B was almost the same but its variability or the range between the lowest score and the

highest one in Class B is larger than that of Class A (Hatch and Farhady, 1982 p. 57).

standard deviation (11.44) lies between that of class A or B. To see whether class A, B and

D were statistically homogeneous, an independent t-test was used (see Table 4.8).

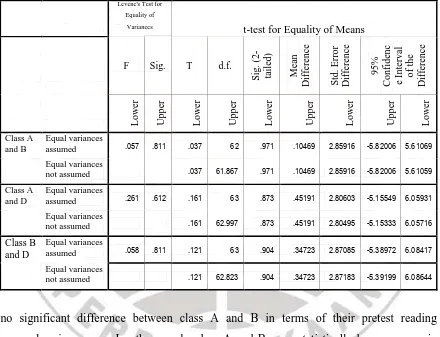

Table 4.8 below shows the result of SPSS independent t-test to see the

homogeneity of the groups or class A, B and D. It indicates that class A and B were

statistically homogeneous, but class D is not. Based on the independent t-test SPSS V.15

analysis, the null hypothesis was accepted when Class A and B were compared. The

t-value (t= -.036, d.f.=62, p= .704) was less than the alpha ( .05). This means that there was

Table 4.8: Independent Samples Test of Pretest Scores of Class A, B and D

Levene's Test for Equality of

Variances t-test for Equality of Means

rejected. There was significant difference between class D and class A or B. Thus, class A

and B were selected to be the STAD CL and DI groups.

Meanwhile, the result of pretest on every level of comprehension will be discussed

Afterward, to follow Slavin (1995 p. 74), the teacher together with the researcher,

documented and averaged the previous test scores to determine the students‟ base score. In

STAD CL group, the base scores were the basis for grouping the students (Slavin, 1995 p.

94; Leighton in Cooper, 1990 p. 320); in DI group, in contrast, they were only used for

comparing the gain between pretest and posttest.

Then, in STAD CL group, the teacher assigned students in groups/teams.

Following Slavin (1995 pp. 74-5; see also Leighton in Cooper, 1990 p. 320), the

researcher and the teacher carried out at least five steps: i) making a form of team

summary sheets for every group of students; ii) ranking students from highest to lowest in

past performance on the sheet on which previous daily test scores were the basis; iii)

dividing students by four; iv) assigning and balancing them to the team so that the group

consisted of heterogeneous performance with the average were relatively equal; and v)

filling out team summary sheet (see Appendix 13) by filling the names of the students on

each teams. This grouping, as STAD CL required, was intended to have equal „achievement division‟ wherein each team consisted of the students with various comprehension ability (Slavin 1995; Apple, 2006 p. 280; Lang and Evan, 2006 p. 422).

4.2.4 Inducting the Teaching Programs

After the groups of participants were determined, the researcher and the teacher

inducted the teaching programs to both groups. It aimed to introduce and familiarize both

the teacher and the students to apply the principles and procedures of the teaching

programs (see Chapter II) and to see potential problems that might come up during the

implementation.

In this stage, the researcher, as participant observer, observed and took part

actively in (Creswell, 2008 p. 222; Cowie in Heigham and Crocker, 2009, p. 167) helping

the teacher as well as students implement the teaching procedures in both groups. In

implementing the teaching programs, the researcher assisted the teacher in timing the

activities, reminding teachers the teaching procedures to avoid missing, getting involved in

managing the classroom and directing students to do what should they do.

On this induction of teaching programs, it was observed that the students in STAD

CL group were more enthusiastic than those in DI group. In STAD CL group, many

students asked questions to the teacher and also researcher either about the procedures of

livelier than that of DI. STAD CL seemed, as Olsen and Kagan (1992; see also Johnson

and Johnson 1989 in Sach et al. 2003; Ming, 2007) claim, promoted the interaction and

communication not only between teachers and the students, students and students, the

researcher and the teacher, and the researcher and the students. This communication and

interaction were enhanced as the teacher and the students were not familiar yet with the

procedures and the principles of either STAD CL. In DI group, the students were not

observed as enthusiastic as those in DI. This is probably because the DI steps (see Chapter

II Section 2.3.3) were not much different with what they used to do. So, the students did

not ask many questions about the procedures of the programs, instead, they did the

practices as they were required. The response to the practices in DI will be discussed in

Chapter 5 Section 5.3.

4.3 Teaching Programs

The teaching programs were conducted in the classroom of participants twice a

week in the schedule of English subject. They were scheduled twice a week, each of which

80 minutes long. This length was in accordance with the enactment of the 2006 school

based curriculum (Depdiknas, 2004).

The teaching program of STAD CL and DI, as previously mentioned (see Chapter

II Section 2.2 and 2.3), had similarities and differences, which can be seen in lesson plans

(see Appendices 11a and 11b). The similarities lied on the steps in pre-reading, partly

while reading and post reading activities (Barnet, 1988a; Brown, 2001; Vaezi, 2006;

Hedgcock and Ferris, 2009). In both groups, the activities consisted of preparation, class

presentation, structured and guided practices, quiz; and individual accountability (as

described earlier in Chapter II Section 2.2.3 and 2.3.3).

The difference existed when students did the team or independent practice and the

reward or goal oriented structures (Slavin 1995 p. 16). When doing the practice, to follow

Slavin (1995 p. 77; see also Leighton in Cooper, 1990 p. 320; Apple, 2006 p. 282)

suggested, the students in the STAD CL group worked in teams, but in DI group, students

worked individually (Moore, 2008; Joyce et all, 2011; Arend and Kilcher, 2010, p. 201).

In terms of reward or goal-oriented structure, STAD CL groups applied cooperative goal

oriented structure wherein students were assessed individually and rewarded as both an

goal achievement. On the other hand, in DI group, competitive goal-oriented structure was

employed (Slavin (1995 p. 16; Lie, 2004 p. 24), wherein the students were only assessed

and rewarded as an individual. It operated competitive goal structure, wherein each individual‟s goal efforts frustrated other‟s goal attainment (Slavin, 1995 p. 16; Lie, 2004 p. 24). In other words, the reward in STAD CL group was group certificate, but in DI

group it was individual certificate (Slavin, 1995 p.80; Leighton in Cooper 1990 p. 312;

Lie, 2004).

4.3.1 Preparation (Before Instruction)

In preparation, more activities were done in STAD CL group than those in DI one.

In the former, as previously mentioned (see Section 4.2.3), the teacher grouped the

students based on their previous test scores. In the latter, there was no grouping. In STAD

CL group, the teacher announced the members of each group/team and let the students

build their team by naming their group, introducing group mates and creating team name,

logo, yell etc. (Slavin, 1995 pp. 139-140; Apple, 2006 p. 279; Jacobs, 2004). This aimed

to give team members a chance to do something fun, to get familiar with each other

(Slavin, 1995 p. 75) and a kind of warming up before cooperating. In DI group, there was

no specific preparation besides materials and the practice like in STAD CL group.

From the observation, in preparing STAD CL, the teacher had more activities to do

than that of DI. In STAD CL, the teacher needed to determine the base score and assigned

students into heterogeneous but balanced group in terms of the achievement. Then, the

teacher needed to announce the teams and let the students build their team. Meanwhile in

DI, the teacher was not required to do such activities. This indicates that applying STAD

CL is more demanding for the teacher than DI. This fact is in line with the claims that

applying STAD CL spends considerable time in preparing the students to learn; in

recording the student performance on each learning task and in calculating group

achievement scores (Killen, 1998 p. 88) and in researching a topic and creating lesson

(Solari, 2008).

Although STAD CL is more demanding for teachers, the grouping and the team

building e.g. making yell, leads to the feeling of togetherness. The students get closed to

each other in their teams, as revealed in interview that will be discussed in Section 5.3.

They looked cheerful and spirited. This fact confirms the STAD CL principle that the