Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Survey of Recent Developments

George Fane

To cite this article:

George Fane (2000) Survey of Recent Developments, Bulletin of Indonesian

Economic Studies, 36:1, 13-45, DOI: 10.1080/00074910012331337773

To link to this article:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910012331337773

Published online: 21 Aug 2006.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 59

View related articles

SURVEY OF RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

George Fane

Australian National University

SUMMARY

GDP grew slowly but steadily during 1999, thus confirming that Indonesia is at last recovering, although more slowly than the other countries most affected by the Asian crisis. Growth in 2000 is officially forecast at 3–4%. With the effects of discretionary fiscal policies included, inflation during 2000 is expected to be in the range 5–8%, compared with 2% during 1999. Indonesia’s sluggish output growth is probably due mainly to delays in restructuring the banking sector and resolving corporate debts. About 80% of the Rp 639 trillion of government bonds needed to recapitalise the banks has now been issued. However, with capital–asset ratios of only 4%, and assets dominated by illiquid bond holdings, the banks appear fragile.

The meeting of the Consultative Group on Indonesia promised new official loans of $4.7 billion. In addition, Indonesia signed a new agreement with the IMF that raises the total amount of its promised loan from $11 billion to $16 billion.

The policies to be followed under the new IMF agreement continue to emphasise the avoidance of money creation as a way of financing the budget deficits that will result from the interest payments on the government’s greatly increased debts. The government has unveiled new initiatives to deal with judicial corruption, and hopes that they will improve the workings of the bankruptcy law and hence the restructuring of corporate debt.

14 George Fane

MACROECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS

The massive fall in GDP—which was 13.7% lower in 1998 than in 1997— has been arrested, and a sluggish recovery has now been sustained since the fourth quarter (Q4) of 1998. However, because of the collapse of exports, fixed investment and stock accumulation during 1998, GDP in Q1 of 1999 was 8% lower than a year earlier, and GDP for the whole of 1999 was only 0.2% above its 1998 level.1 Bank Indonesia is forecasting

that in 2000 it will be 3–4% higher than in 1999, and the government is hoping to achieve a medium-term annual GDP growth rate of 5–6%.

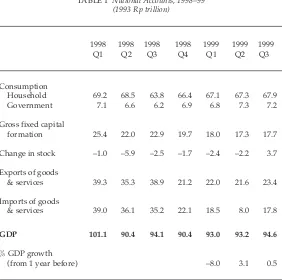

Table 1 shows that household and government consumption never fell as sharply as exports and investment; they have now been growing since Q2 of 1998. In contrast, exports, fixed investment and the level of stocks continued to fall until the middle of 1999, but began to grow in Q3.2 In this quarter, total exports and fixed investment were only 59%

and 70%, respectively, of their level in Q1 of 1998. An important element in the plunge in exports was the difficulty experienced by Indonesian companies in getting trade credit. The collapse of investment was part cause and part consequence of the fact that Indonesian banks have not made major new loans since the middle of 1998, and Indonesian companies have not been able to get new offshore loans since the start of the crisis.3 The main factor in the recovery of GDP has been the switching

of domestic spending from imported to domestic goods. The fact that imports in Q3 of 1999 were only 46% of their level in Q1 of 1998 means that consumption and investment spending on domestic goods fell much less than total consumption and investment (table 1).

The consumer price index, which had risen by 78% between December 1997 and December 1998, rose by only 2% between December 1998 and December 1999. This overall CPI change was the combination of falling prices of tradable goods, due to the strengthening rupiah, and rising prices of non-tradables. Inflation is expected to rise this year: Bank Indonesia is forecasting that the increase in the CPI between December 1999 and December 2000 will be 3–5% if the effects of increased VAT, fuel price rises and the tariff on rice are excluded. These effects are expected to add 2–3 percentage points during the year, thus bringing the total increase to 5–8%.

TABLE 1 National Accounts, 1998–99 (1993 Rp trillion)

1998 1998 1998 1998 1999 1999 1999

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3

Consumption

Household 69.2 68.5 63.8 66.4 67.1 67.3 67.9

Government 7.1 6.6 6.2 6.9 6.8 7.3 7.2

Gross fixed capital

formation 25.4 22.0 22.9 19.7 18.0 17.3 17.7

Change in stock –1.0 –5.9 –2.5 –1.7 –2.4 –2.2 3.7

Exports of goods

& services 39.3 35.3 38.9 21.2 22.0 21.6 23.4

Imports of goods

& services 39.0 36.1 35.2 22.1 18.5 8.0 17.8

GDP 101.1 90.4 94.1 90.4 93.0 93.2 94.6

% GDP growth

(from 1 year before) –8.0 3.1 0.5

Source: Bank Indonesia (BI).

was the strongest rupiah exchange rate since early 1998. During January 2000, however, the rupiah weakened to around Rp 7,500/$, and the budget assumption that the average exchange rate for the year would be Rp 7,000/$ began to look optimistic. This weakening was probably due mainly to the widespread violence and civil unrest, and the rumours of a military coup.

16 George Fane

TABLE 2 GDP Growth in Asian Crisis Countries, 1996–99 (% change from one year before)

Indonesia Korea Malaysia Philippines Thailand

Source: As for figure 1.

FIGURE 1 Exchange Rates of Asian Crisis Countries, 1997–99 (units of local currency per $; Jan-97 = 100)

Source: CEIC Data Hong Kong.

the most slowly in 1999. Figure 1 shows that the rupiah has appreciated relative to the other four currencies since mid 1998; it initially depreciated by much more, but the recent appreciation has not been nearly large enough to offset the original depreciation relative to the others. Figure 2 tells a similar story for interest rates: 3-month interest rates rose by much more in Indonesia than in any of the other countries. Since late 1998, interest rates have come down by more in Indonesia than elsewhere, but are still higher than in any of the other crisis countries.

Malaysia: Interbank rate, weighted average, 3 months.

Indonesia: Bank Indonesia Certificates (SBI) rate, 90 days (auction result).

Korea: Yield on certificates of deposit, monthly average, 91 days.

Philippines: Interbank rate, Central Bank of the Philippines, 3 months.

Thailand: Weighted average interbank interest rate (Bangkok Bank, Siam Bank, Standard Chartered Bank), 3 months.

Source: As for figure 1.

18 George Fane

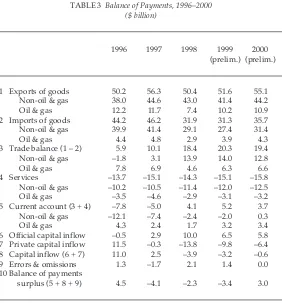

Table 3 shows that whereas in 1996 there was an official capital outflow of $0.5 billion, the total official net inflow in the three years 1997–99 was $19.4 billion. Capital flows were first substantially affected by the crisis in the last quarter of 1997, when there was an official net inflow of $3.2 billion and a private net outflow of $8.6 billion. If ‘the crisis’ is defined as the period from Q4 of 1997 to Q4 of 1999 inclusive, then adding the flows in Q4 of 1997 to those shown in table 3 for 1998 and 1999 implies that the total official net inflow during the crisis was $20 billion and the total net private outflow was $32 billion. While the official inflows during the course of the crisis have amounted to only 45% of the $43 billion label used to describe the original November 1997 IMF package, they have been large enough to offset over 60% of the private net outflows in this period. The budget papers predict that the total capital account will be almost in balance in 2000.

DEMOCRACY, ECONOMIC POLICY MAKING

AND THE RULE OF LAW

Indonesia’s current political situation and its social and legal problems are vitally important in their own right, but are also crucial to economic recovery because of their impact on investor confidence. For all the killings and destruction that accompanied its withdrawal from East Timor, Indonesia has at least shed the moral and financial burden of its former province and is stronger for having done so. It is also immensely strengthened by having a democratic government whose legitimacy is generally accepted. However, before the economy can recover fully, Indonesia must also restore civil and political tranquillity and strengthen the rule of law. Most of all, this means ending the ethnic and religious violence that continues to smoulder in several regions and that flared up during the last few months in Maluku, Lombok and Aceh. It also means resolving the secessionist demands in Aceh (those in Irian Jaya are much less serious), consolidating Indonesia’s remarkable progress from military dictatorship to democracy, and greatly strengthening the legal system.

Economic Policy Making

TABLE 3 Balance of Payments, 1996–2000 ($ billion)

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000

(prelim.) (prelim.)

1 Exports of goods 50.2 56.3 50.4 51.6 55.1

Non-oil & gas 38.0 44.6 43.0 41.4 44.2

Oil & gas 12.2 11.7 7.4 10.2 10.9

2 Imports of goods 44.2 46.2 31.9 31.3 35.7

Non-oil & gas 39.9 41.4 29.1 27.4 31.4

Oil & gas 4.4 4.8 2.9 3.9 4.3

3 Trade balance (1 – 2) 5.9 10.1 18.4 20.3 19.4

Non-oil & gas –1.8 3.1 13.9 14.0 12.8

Oil & gas 7.8 6.9 4.6 6.3 6.6

4 Services –13.7 –15.1 –14.3 –15.1 –15.8

Non-oil & gas –10.2 –10.5 –11.4 –12.0 –12.5

Oil & gas –3.5 –4.6 –2.9 –3.1 –3.2

5 Current account (3 + 4) –7.8 –5.0 4.1 5.2 3.7

Non-oil & gas –12.1 –7.4 –2.4 –2.0 0.3

Oil & gas 4.3 2.4 1.7 3.2 3.4

6 Official capital inflow –0.5 2.9 10.0 6.5 5.8

7 Private capital inflow 11.5 –0.3 –13.8 –9.8 –6.4

8 Capital inflow (6 + 7) 11.0 2.5 –3.9 –3.2 –0.6

9 Errors & omissions 1.3 –1.7 2.1 1.4 0.0

10 Balance of payments

surplus (5 + 8 + 9) 4.5 –4.1 –2.3 –3.4 3.0

Source: BI.

20 George Fane

to continue in his position, and under the new Bank Indonesia Act he can only be forced out of office on medical grounds or for the commis-sion of a crime.

The fragmented state of economic policy making was deplored in an article by the Senior Deputy Governor of BI, Professor Anwar Nasution, who has been tipped as a likely successor to Sjahril (The Business Times, 26/1/2000). One of the problems of the economics ministers is that, in common with the rest of the National Unity Cabinet (Mackie 1999), they represent a wide spectrum of political parties. The Finance Minister, Bambang Sudibyo, is a member of Amien Rais’s National Mandate Party (PAN), the Coordinating Minister, Kwik Kian Gie, and the State Minister of Investment and State Enterprises, Laksamana Sukardi, belong to Megawati’s PDI-P, while Yusuf Kalla, the Minister of Trade and Industry, is a Golkar member.

In order to avoid being dominated by the economics ministries, the President has set up his own board of economic advisers, the DEN (Dewan Ekonomi Nasional), which comprises a number of prominent economists and businessmen and is headed by Emil Salim, one of the most eminent of the group of technocrats that pressed for deregulation during the Soeharto years. Perhaps in part because of a lack of interest in economic problems, Gus Dur has not used the DEN to flesh out his own preferred economic policies, but has rather suggested that its members take their ideas to the various economics ministers. The latter are reported to be understandably unenthusiastic about taking advice from the new interlopers. The President’s willingness to tolerate divisions among his economics ministers and advisers and to delegate concern with economic policy to others may well reflect the fact that these matters are mostly of secondary importance now that the outlines and much of the detail of economic policy for the next four years have been laid down in the agreement with the IMF.

The New IMF Program

Because it was not satisfied that former President Habibie’s government had responded satisfactorily to the PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) investigation into the Bank Bali scandal, and because of the bloodshed that followed East Timor’s vote for secession, the IMF suspended its lending program in September 1999.4

the international community, on condition that Indonesia pressed ahead with economic reforms. At the same time Richard Holbrooke, US Ambassador to the UN, explicitly warned Indonesia’s generals that the loans were also conditional on their not staging a coup. The government signed a new letter of intent (LOI) to the IMF on 20 January, in which it noted that a strong set of measures was being taken to ‘credibly advance’ its investigation of the Bank Bali affair. These were: to release the full version of the PwC report; to name six suspects, among whom were a senior official of Bank Indonesia, the former deputy chairman of IBRA (the Indonesian Bank Restructuring Agency), the former head of Bank Bali and Mr Tanri Abeng, a former minister; and to instruct the Attorney General to investigate the case further.

The new LOI is longer and more detailed than its predecessors, and much of the new detail involves defining procedures to audit state agencies and set up committees to investigate cases of suspected corruption and prosecute those responsible. There seems little reason to doubt that the increased emphasis on fighting corruption comes at least as much from the new government as from the IMF.

The budget begins the process of applying the economic policies in the LOI, which preserve the principles of earlier LOIs. BI is committed to keeping annual inflation to 5% and will do this by targeting base money; the poverty alleviation programs are being overhauled and expanded in aggregate; bank restructuring should be completed this year; the government plans to reduce its debts by privatising state-owned enterprises and selling off assets acquired as a result of the bank bailout; attempts are to be made to force judges to apply the bankruptcy law correctly; and teeth are being put into the Jakarta Initiative, which was originally created in 1998 as a purely voluntary mediation system for restructuring corporate debt.

In early February 2000, the loans promised by the US Treasury Secretary were officially approved. The Consultative Group on Indonesia (CGI)—the group of official lenders dominated by the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Japan—met in Jakarta on 1 and 2 February and agreed to lend Indonesia $4.7 billion.5 Then on 4 February,

the IMF formally agreed to add $5 billion to the $11 billion that it had previously agreed to lend, and immediately disbursed $349 million.

22

G

eo

rg

e F

ane

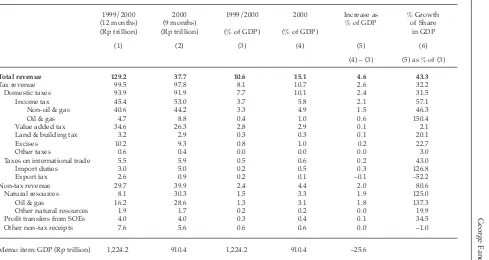

TABLE 4 Draft Budget Revenues for 1999/2000 and 2000

1999/2000 2000 1999/2000 2000 Increase as % Growth

(12 months) (9 months) % of GDP of Share

(Rp trillion) (Rp trillion) (% of GDP) (% of GDP) in GDP

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

(4) – (3) (5) as % of (3)

Total revenue 129.2 37.7 10.6 15.1 4.6 43.3

Tax revenue 99.5 97.8 8.1 10.7 2.6 32.2

Domestic taxes 93.9 91.9 7.7 10.1 2.4 31.5

Income tax 45.4 53.0 3.7 5.8 2.1 57.1

Non-oil & gas 40.6 44.2 3.3 4.9 1.5 46.3

Oil & gas 4.7 8.8 0.4 1.0 0.6 150.4

Value added tax 34.6 26.3 2.8 2.9 0.1 2.1

Land & building tax 3.2 2.9 0.3 0.3 0.1 20.1

Excises 10.2 9.3 0.8 1.0 0.2 22.7

Other taxes 0.6 0.4 0.0 0.0 0.0 3.0

Taxes on international trade 5.5 5.9 0.5 0.6 0.2 43.0

Import duties 3.0 5.0 0.2 0.5 0.3 126.8

Export tax 2.6 0.9 0.2 0.1 –0.1 –52.2

Non-tax revenue 29.7 39.9 2.4 4.4 2.0 80.6

Natural resources 8.1 30.3 1.5 3.3 1.9 125.0

Oil & gas 16.2 28.6 1.3 3.1 1.8 137.3

Other natural resources 1.9 1.7 0.2 0.2 0.0 19.9

Profit transfers from SOEs 4.0 4.0 0.3 0.4 0.1 34.5

Other non-tax receipts 7.6 5.6 0.6 0.6 0.0 –1.0

making only very slow progress with bank restructuring and asset sales, he replaced its head and some of its most senior staff members.

Confined to Barracks for Now

Indonesia’s National Commission on Human Rights, which had been requested by the government to investigate alleged atrocities in East Timor, presented a report to the Attorney General on 31 January, documenting some of the ‘planned and systematic violence’ that had followed the ballot. The report recommended that ‘General Wiranto, as TNI [Indonesian military] chief, should be held accountable’ and that the Attorney General investigate Wiranto and 31 others, among whom are five other generals. In mid February, Wiranto was suspended from cabinet, and his position as Coordinating Minister for Political Affairs and Security was assumed on an acting basis by Lt General (ret.) Surjadi Soedirdja, the Minister of Home Affairs. Despite the earlier rumours of a coup, the military seemingly accepted Wiranto’s dismissal, and the prospect that he and other officers may be brought to trial for their part in the events in East Timor.

At least for the time being, the President appears to have established the dominance of a democratically elected civilian government over the armed forces. This achievement is fragile, but it is something that seemed scarcely possible even two years ago. Gus Dur’s astute judgment has been one important factor in bringing it about; others include the popular fury that toppled Soeharto, the increased dependence of Indonesia on the international community, the disgrace that the armed forces brought on themselves in East Timor and the fact that the National Commission on Human Rights did not flinch from its duty.

THE BUDGET

Projected Revenues and Expenditures in 2000

The President and Vice President unveiled the new budget on 27 January (tables 4, 5 and 6). The new financial year, beginning on 1 April, will last only nine months, so as to align the financial and calendar years with effect from 2001.

24

G

eo

rg

e F

ane

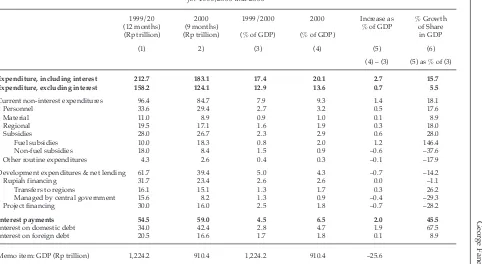

TABLE 5 Draft Budget Expenditures for 1999/2000 and 2000

1999/20 2000 1999/2000 2000 Increase as % Growth

(12 months) (9 months) % of GDP of Share

(Rp trillion) (Rp trillion) (% of GDP) (% of GDP) in GDP

(1) 2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

(4) – (3) (5) as % of (3)

Expenditure, including interest 212.7 183.1 17.4 20.1 2.7 15.7

Expenditure, excluding interest 158.2 124.1 12.9 13.6 0.7 5.5

Current non-interest expenditures 96.4 84.7 7.9 9.3 1.4 18.1

Personnel 33.6 29.4 2.7 3.2 0.5 17.6

Material 11.0 8.9 0.9 1.0 0.1 8.9

Regional 19.5 17.1 1.6 1.9 0.3 18.0

Subsidies 28.0 26.7 2.3 2.9 0.6 28.0

Fuel subsidies 10.0 18.3 0.8 2.0 1.2 146.4

Non-fuel subsidies 18.0 8.4 1.5 0.9 –0.6 –37.6

Other routine expenditures 4.3 2.6 0.4 0.3 –0.1 –17.9

Development expenditures & net lending 61.7 39.4 5.0 4.3 –0.7 –14.2

Rupiah financing 31.7 23.4 2.6 2.6 0.0 –1.1

Transfers to regions 16.1 15.1 1.3 1.7 0.3 26.2

Managed by central government 15.6 8.2 1.3 0.9 –0.4 –29.3

Project financing 30.0 16.0 2.5 1.8 –0.7 –28.2

Interest payments 54.5 59.0 4.5 6.5 2.0 45.5

Interest on domestic debt 34.0 42.4 2.8 4.7 1.9 67.5

Interest on foreign debt 20.5 16.6 1.7 1.8 0.1 8.9

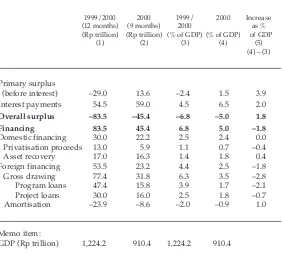

TABLE 6 Draft Budget Financing for 1999/2000 and 2000

1999/2000 2000 1999/ 2000 Increase (12 months) (9 months) 2000 as % (Rp trillion) (Rp trillion) (% of GDP) (% of GDP) of GDP

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

(4) – (3)

Primary surplus

(before interest) –29.0 13.6 –2.4 1.5 3.9

Interest payments 54.5 59.0 4.5 6.5 2.0

Overall surplus –83.5 –45.4 –6.8 –5.0 1.8 Financing 83.5 45.4 6.8 5.0 –1.8

Domestic financing 30.0 22.2 2.5 2.4 0.0

Privatisation proceeds 13.0 5.9 1.1 0.7 –0.4

Asset recovery 17.0 16.3 1.4 1.8 0.4

Foreign financing 53.5 23.2 4.4 2.5 –1.8

Gross drawing 77.4 31.8 6.3 3.5 –2.8

Program loans 47.4 15.8 3.9 1.7 –2.1

Project loans 30.0 16.0 2.5 1.8 –0.7

Amortisation –23.9 –8.6 –2.0 –0.9 1.0

Memo item:

GDP (Rp trillion) 1,224.2 910.4 1,224.2 910.4

by the phasing out of some emergency programs created to deal with the crisis-related increase in poverty. The regions are gradually getting more fiscal autonomy, but the main changes (Booth 1999: 27–32) will not occur until 2001.

26 George Fane

are assumed to offset the rise in non-interest expenditures by enough to convert the primary deficit (i.e. the deficit before allowing for interest payments) of 2.4% of GDP in FY 1999/2000 into a primary surplus of 1.5% of GDP in FY 2000.

However, interest payments on government debt are projected to rise from 4.5% of GDP in FY 1999/2000 to 6.5% in FY 2000. As a result, the overall deficit in FY 2000, as officially measured, is projected to be 5% of GDP. This happens to be less than the measured deficit in FY 1999/2000 of 6.8% of GDP, but the comparison is meaningless: budget deficits are supposed to measure how much the government is borrowing from other sectors, but in the aftermath of Indonesia’s economic crisis its budget deficits do not have this (or any other simple) meaning. The reason is that the cost of the bank bailout has not been acknowledged as an on-budget expense.6 Since the deficit in FY 1999/2000 should have included

a large part of the cost of bailing out the banks, it was really many times the size of the true deficit in FY 2000.

The officially measured deficit for FY 1999/2000 reported in table 6 is smaller than predicted, because oil prices and revenues are higher than expected, and because development spending fell behind schedule. The latter was due partly to recent political uncertainties and civil unrest, and partly to donors delaying disbursement of funds in response to the Bank Bali affair.

Roughly half of the measured deficit in FY 2000 is to be financed by official foreign borrowing. The budget assumed that Indonesia would obtain $4.1 billion in new loans from major donors at the CGI meeting, a target easily surpassed by the $4.7 billion actually pledged. Most of the remaining half of the measured deficit is to be financed by IBRA’s asset sales and portfolio income (1.8% of GDP), the rest by privatisation of state-owned enterprises (0.7% of GDP).

disposals and privatisation sales should be classified as dis-investment in assets directly controlled by the government. If all three of the above corrections were made, the measured deficit of 5% of GDP in FY 2000 would become a surplus of 1.5%. In contrast, if measured expenditures in FY 1999/2000 were adjusted for the omission of the cost of the bank bailout and for the delays in reimbursing Pertamina for fuel subsidies, the true deficit would be far in excess of the 6.8% officially recorded.

TRADE LIBERALISATION

Although the trade regime is now much more open than it was in 1995, when it was already far more open than it had been in the mid 1980s, Indonesia has fallen behind the targets set in the May 1995 trade liberalisation package (Nasution 1995: 13–18). A new package of trade reforms announced on 31 December reduced the rates on 232 tariff lines, but this still left 2,142 lines above the 1995 target.

Apart from those on automobiles and alcohol, the highest tariff rate is now 25%, and this rate applies to only 45 tariff lines, mainly in the steel and chemical sectors. The four-year program agreed to with the IMF contains a commitment by the government to have a three-tier tariff structure in place by the end of 2003, with rates of 0, 5 and 10% for all items except automobiles and alcohol. Most non-tariff barriers have already been removed and all the remaining ones, except those required for health and safety reasons, are scheduled to go by the end of 2003. The taxes on exports of sawn timber are to be replaced by higher royalties and resource rent taxes. Indonesia is obliged by the barriers imposed on it by the industrialised countries to set quotas on exports of garments. All its other export licensing requirements—the main ones are now coffee, logs and wood products—are to be removed by the end of 2000.

The LOI makes a commitment to remove all import duty exemptions. This proposal is quite controversial, since such exemptions currently apply to about half of imports and are used mainly for producing exports and by investors. The LOI sides with those who argue that exemptions should be avoided and tax bases made as broad as possible, so as to allow rates to be set low. The opposite school of thought is that it is important for non-oil exporters to have access to inputs at world prices, and that the inevitable delays in obtaining duty drawbacks therefore make exemptions highly desirable.

28 George Fane

strengthening of the rupiah. This tariff is supposed to be temporary and will end in August 2000, unless it is explicitly renewed at that time. Exports of crude palm oil are still taxed, but the tax rate was reduced from 30% of the government’s reference price to 10% in July 1999. The effective rate is lower because world prices are now below the reference price.

PRIVATISATION

The government continues to make only very slow progress in privatising state-owned enterprises (SOEs). In FY 1999/2000, the initial budget projection was for privatisation revenue of Rp 13.0 trillion. This was reduced in the LOI to Rp 8.6 trillion and, with the financial year almost over, the total amount realised was only Rp 6.2 trillion. This was made up by sales of blocks of shares in only four enterprises: Telkom (Rp 2.8 trillion), two container terminals (Rp 2.8 trillion) and Indofood (Rp 0.5 trillion). Planned sales to strategic investors of shares in plantation companies and the Soekarno–Hatta airport authority fell through because, in each case, the prospective investor and the government could not agree on the price.

The economic case for privatisation is that managers answerable to private shareholders have a more direct incentive to eliminate cross-subsidies and maximise profits than do managers answerable to a minister. However, privatisation presents a dilemma to governments: selling assets yields an immediate cash flow far in excess of their earnings in a single year, but is politically unpopular, in part because many people feel that enterprises that are national icons should not be sold to private entrepreneurs, and in part because full privatisation puts an end to hidden cross-subsidies to employees, favoured customers and suppliers.

Hong Kong) for $243 million. The government did sell the whole of its former shareholding in Indofood, but this was only ever a minority shareholding. The sale of the Surabaya container terminal to Mermaid (a subsidiary of P&O Australia) raised $174 million. In this case, the government retained 51% of the shares.

Revenue from privatisation in FY 2000 is projected to be at least Rp 5.9 trillion, which is about 13% of the measured budget deficit. The State Minister for Investment and State Enterprises has suggested that the actual amount raised may be as high as Rp 8 trillion. These amounts refer to sales of shares in traditionally state-owned firms. Thus the FY 2000 projection excludes the IPO in Bank Central Asia, which is counted as part of IBRA’s contribution to the financing of the budget deficit.7

The government has not yet announced exactly what it will sell in FY 2000. Although the LOI mentions Telkom and Indosat as strong possible candidates for further privatisation, the government plans to deregulate the telecommunications sector before fully privatising it, and deregulation is not expected to be completed before 2004. However, this does not preclude the possibility of further sales of blocks of shares in 2000: following IPOs in 1995, and the 1999 sale of a further 9.8% of its remaining Telkom shares, the government still owns roughly two-thirds of both companies.8 Other privatisation possibilities in 2000 are: Sukarno–Hatta

International Airport in Jakarta; Garuda Indonesia; palm oil plantations in North Sumatra; a fertiliser company in East Kalimantan; a coal mining company in South Sumatra (PT Bukit Asam); and two pharmaceutical companies.

THE TEXMACO AFFAIR

In late November, the State Minister for Investment and State Enterprises, Laksamana Sukardi, revealed that President Soeharto had been directly involved in helping the textile and engineering conglomerate Texmaco, run by Mr Marimutu Sinivasan, to secure loans from Bank Indonesia that were channelled through Bank Negara Indonesia (BNI) and other state banks answerable to Sukardi’s ministry. The total loan package, which was negotiated between November 1997 and February 1998, was for about $1 billion, in the form of $754 million in foreign exchange and Rp 1.9 trillion (anything from $180 million at the February 1998 exchange rate to $500 million at the November 1997 rate) in domestic currency.

30 George Fane

under a special BI facility for export finance, to which this prudential limit does not apply. In the event, Texmaco apparently used the loan to repay short-term foreign currency debts. From Texmaco’s viewpoint, the loan from the export finance facility also had the advantage of being at a heavily subsidised interest rate.

At least initially, the reaction of the DPR seems to have been that the Texmaco group is so important a generator of jobs and exports that the affair must not be allowed to disrupt its operations. The Chairman of the Indonesian Textile Association said that ‘if you want to kill a rat, don’t burn down the house to do it’ (Business Indonesia Perspective, 1/1/2000: 21). One might add ‘so find a better way’. The Attorney General is still investigating possible illegalities.

POVERTY

Estimates of the Proportion of the Population in Poverty

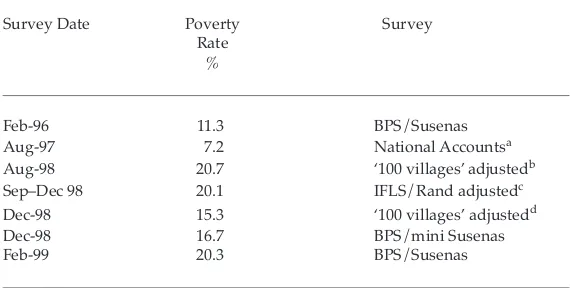

The debate over the extent to which poverty increased as a result of the crisis was comprehensively surveyed by Booth (1999). As Booth’s table 6 showed, the special ‘mini’ (‘Susenas-type’) survey of household expenditure carried out by the Central Statistics Agency (BPS) in December 1998 indicated that the poverty rate rose from 11.3% in February 1996 to 16.7% in December 1998.9 These estimates refer to the ‘headcount’

rate of poverty, defined as the percentage of the population with consumption expenditures below the official BPS poverty line.

In February 1999, a full household expenditure survey was undertaken and the results have now been released. Suryahadi, Sumarno, Suharso and Pritchett (1999)—henceforth SSSP—analyse these data and adjust existing studies so as to put them all on a comparable basis and estimate how poverty changed during the crisis. The main features of their results are summarised in table 7. Starting from the rate of 11.3%, which was officially estimated by BPS from a full household expenditure survey in February 1996, poverty fell to 7.2% in August–October 1997, just before it began to be affected by the crisis (SSSP 1999: table 6, last column).10 It then rose sharply to just over 20% in August 1998 and was

still just over 20% in February 1999. The exact rate implied by the February 1999 survey is 20.3%. If this new estimate is correct, it implies that the poverty rate in February 1999 was similar to the rate observed in the mid 1980s, whereas the December 1998 mini household expenditure survey had implied a regression only to late 1980s rates.

apparently indicate a much lower poverty rate even than the 16.7% estimated for December 1998. At least some of the surveys must contain measurement errors, because they tell an implausible story in which the poverty rate took a one-year roller coaster ride from somewhere between 20 and 21% in mid 1998 down to 16.7% in December, climbed to 20.3% in February 1999, and then by August 1999 had apparently swooped back down to below the rate in December 1998.11

One possible interpretation of these estimates is the following. Because the price of rice (which has a much higher weight in the basket that defines

TABLE 7 Estimates of Poverty Rate on a Consistent BPS Basis, 1996–99

Survey Date Poverty Survey

Rate %

Feb-96 11.3 BPS/Susenas

Aug-97 7.2 National Accountsa

Aug-98 20.7 ‘100 villages’adjustedb

Sep–Dec 98 20.1 IFLS/Rand adjustedc

Dec-98 15.3 ‘100 villages’ adjustedd

Dec-98 16.7 BPS/mini Susenas

Feb-99 20.3 BPS/Susenas

aThere was no survey in August 1997. The estimate was derived by Suryahadi et

al. (1999), who adjusted the BPS estimate for February 1996 using national accounts data on the changes in consumption between February 1996 and August 1997.

bAdjustment by SSSP of estimate by the Social Monitoring and Early Response

Unit (SMERU); reported rate was 21.41%.

cAdjustment by SSSP of estimate from a special round of the Indonesian Family

Life Survey (IFLS) conducted by the Rand Corporation; reported rate was 19.9%.

dAdjustment by SSSP of estimate by SMERU; reported rate was 16.79%.

32 George Fane

the poverty line than in the CPI) has been falling both in absolute terms and relative to the CPI, poverty really did fall between mid 1998 and mid 1999. But the roller coaster ride surely exaggerates the real changes. Although the full household expenditure survey (February 1999) and the mini surveys (December 1998 and August 1999) used identical questionnaires, they were undertaken by different groups within BPS, which may have treated in different ways some of the inevitably arbitrary decisions that must be made in such surveys.

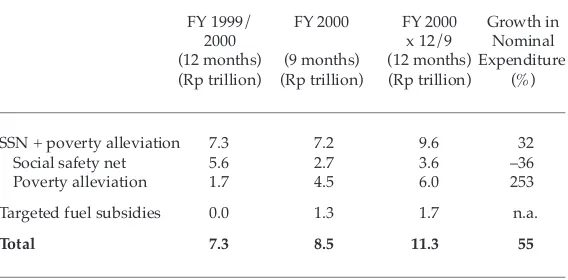

Spending on Programs to Combat Poverty

The new budget and LOI distinguish three broad groups of policies for helping poor people: the social safety net (SSN), poverty alleviation and targeted fuel subsidies.12 The ‘targeted fuel subsidies’ in the welfare

program are expected to cost Rp 1.3 trillion in FY 2000, and represent compensation to poor families for higher domestic fuel prices. The main element is the increased price of kerosene. No decision has yet been made on how to distribute these subsidies.

The difference between the safety net and poverty alleviation programs is partly real and partly a matter of labelling. The SSN programs were created hurriedly in response to the crisis and are now mostly being wound back, whereas the ‘poverty alleviation’ programs are being expanded. For FY 1999/2000, one can say which programs were in the SSN category (budgeted to cost Rp 5.6 trillion in that year) and which were in the poverty alleviation category. Table 8 shows the distribution of the budgetary estimates between the two categories in FY 2000 as it appears in the LOI. However, this division has little meaning, because decisions on which programs to expand and which to eliminate have not yet been finalised. The poverty alleviation program, for which Rp 1.7 trillion was budgeted in FY 1999/2000, is the much amended descendant of the program for backward villages (IDT: Inpres Desa Tertinggal), first introduced in 1994. In FY 2000, this program will be retained and an analogous program for urban areas will be added. But the fate of the individual elements that were in the SSN in FY 1999/2000 has not yet been decided. Some, such as the programs for spending on scholarships and schools, may well be retained, but the majority will be phased out. The programs that are judged to have been most successful and are retained on a long-term basis will be reclassified from ‘SSN’ to ‘poverty alleviation’.

substan-tially: when the FY 2000 budget projections are scaled up to a 12 months basis, the increase will be 55% if the targeted fuel subsidies are included, and 32% if they are excluded.

There are two other kinds of welfare programs in addition to the ‘mainstream’ ones included in table 8. First, there are programs run by NGOs and funded directly by donations from foreign governments. These are small compared with the mainstream programs, but are believed to be growing rapidly. The new LOI expresses the government’s approval of this trend. Second, there are numerous initiatives by provincial governments to alleviate poverty using the growing share of GDP that the central government is allocating directly to them.

The Social Safety Net and Poverty Alleviation Programs

There are currently four elements in the social safety net: a subsidised food program; a program to provide block grants to schools in poor communities and scholarships to help children from poor families to stay in school; a program to subsidise health clinics and medicines in poor areas; and various job creation schemes.

Appraisals of the social safety net programs by SMERU suggest that education subsidies have been the most effectively targeted.13 The funds

TABLE 8 Expenditure on Social Safety Net and Poverty Alleviation, 1999–2000

FY 1999/ FY 2000 FY 2000 Growth in

2000 x 12/9 Nominal

(12 months) (9 months) (12 months) Expenditure (Rp trillion) (Rp trillion) (Rp trillion) (%)

SSN + poverty alleviation 7.3 7.2 9.6 32

Social safety net 5.6 2.7 3.6 –36

Poverty alleviation 1.7 4.5 6.0 253

Targeted fuel subsidies 0.0 1.3 1.7 n.a.

Total 7.3 8.5 11.3 55

34 George Fane

for scholarships have been handed out to village community groups who then have the responsibility of selecting the most needy and deserving children.

The rice subsidy program has not escaped allegations of corruption,14

but is judged by SMERU to have worked quite well, given that the administrative resources needed to issue and stamp ration coupons were not available. Data collected by the National Family Planning Board were used to identify 17 million poor households, using criteria such as whether they live in houses with earth floors and whether they are too poor to own a motorcycle. These data determine the total entitlements of all the poor people in particular villages or urban areas. It appears that trucks are then sent to these locations with roughly appropriate amounts of cheap rice, which people then queue to buy. Self-selection probably ensures that the poor get most of it.

The subsidised health program faces the inevitable problem that in rural areas many families are located far from the nearest health clinics and find it very difficult to make use of even heavily subsidised facilities and medicines. The least successful schemes have been the job creation programs. The contractors who successfully tender for the funds to operate these programs have little incentive to try to allocate the jobs to the most needy, and the infrastructure projects that have been commissioned sometimes appear to have little value.

In 1999/2000 there was one main poverty alleviation program: the

kecamatan (subdistrict) development program (KDP). This is descended

from the IDT program to help poor villages, but differs from it in several ways: funds under the IDT program went directly to villages identified by the government. Under the KDP, funds go to each kecamatan, and villages can compete by submitting proposals. The villages whose proposals are selected then have considerable control over the details of how their grants are spent. The rules of the competition favour small-scale labour-intensive projects that will provide facilities for the use of local communities; examples include repairing roads, renovating or extending schools, clinics and other public buildings, or improving facilities in open air markets.

BANKRUPTCY

Progress under the new bankruptcy law that came into force with the opening of the Commercial Court in September 1998 has been disappointing, but not completely negligible. About 30 cases were filed in 1998 and exactly 100 in 1999. The creditors have won only about one-fifth of the cases brought. To have the defendant declared bankrupt, the plaintiff must prove that the defendant has debts to at least two creditors and that one of these debts is due and payable. Although this test seems relatively simple, most of the decisions in favour of debtors have been made on technicalities. In discussing debt and bankruptcy, the LOI refers to the judiciary having ‘governance problems’, which is a not very indirect way of saying that they are corrupt (LOI, para 62).

Speaking at a seminar on economic recovery, Professor Sadli, an eminent economist and former minister, called on the government to take the lead in speeding up corporate restructuring, and to make an example of a few prominent recalcitrant debtors. One obvious way to do this is for IBRA to file bankruptcy suits in strategic cases. In December 1999, IBRA filed two suits in the Commercial Court against debtors that it claimed had failed to cooperate with it in attempts to restructure their debts (JP, 28/1/00). One case was brought against PT West Kalindo Pulp Papermill, the other against PT Comexindo.

36 George Fane

In the Kalindo case, IBRA’s application was dismissed on two grounds: first, the court held that IBRA had failed to prove that Kalindo had at least two creditors; second, it ruled that Kalindo’s debt was not ‘due and payable’, because IBRA and Kalindo had entered into a debt-restructuring deal.

IBRA’s mixed fortunes at least gave it a better success rate than private creditors.

JUDICIAL CORRUPTION

The LOI reveals three strategies for trying to make the bankruptcy law work as it is supposed to. The first involves the appointment of ad hoc

judges from the private sector to the Commercial Court. Procedures for appointing such judges were published in December 1999, and the LOI announced that IBRA would request that all future cases it files be heard by ad hoc judges. The first time IBRA did so, the Court rejected its request without giving reasons that appeared valid. How much difference ad hoc

judges will make, even if they are eventually admitted, seems doubtful, because decisions by the Commercial Court can be appealed to the Supreme Court, which also regularly finds technical grounds for deciding cases in favour of debtors. Even an appeal to the Supreme Court is not necessarily the final step in bankruptcy cases, because—if there is new evidence, or if there has been a serious misapplication of the law in both the lower court and the Supreme Court—the loser can request the Supreme Court to review its own decisions under a process of Civil Review.

The second element in the government’s strategy is the creation of an Independent Commission for the Audit of State Officials (ICASO), which is to be established and functioning by the end of March. In addition to investigating the wealth of ministers and senior bureaucrats, it will have a special subcommission to investigate the wealth of judges and refer evidence of corruption to the Attorney General for prosecution. The LOI notes that this will be its first priority. A Joint Investigating Team to be coordinated by the Attorney General will investigate allegations of corruption, and its first task will be to investigate corruption within the court system.

What is new is the creation of a framework of regulations to facilitate this process. This is to be done by putting teeth into the Jakarta Initiative (JI), which was originally a purely voluntary mediation framework. The LOI foreshadowed the creation of a new committee, the Financial Sector Policy Committee (FSPC), comprising several of the most senior economics ministers, that reports directly to the President and oversees both IBRA and the JI. One of the functions of the FSPC will be to refer strategic corporate restructuring cases to the JI. If the JI staff judge that the debtor is not negotiating in good faith, they can notify the FSPC, which in turn can recommend that the Attorney General should file an application for the debtor to be declared bankrupt. Actions in the public interest are now defined to include participation in good faith in the Jakarta Initiative, and a new decree defines ‘failure to participate in good faith’.

The strategy of the government (and the IMF) is obvious: they hope to make the bankruptcy law work in the way originally intended by catching the judges of the Commercial Court in a pincer movement: at the same time that the Attorney General will be making strategic bankruptcy applications in the public interest, he will also be directing investigations of possible judicial corruption.

THE RESTRUCTURING OF BANKS

AND CORPORATE DEBTS

The Jakarta Initiative for Restructuring Corporate Debt

The Jakarta Initiative is predicting that agreements to restructure most of Indonesia’s corporate debt will have been reached by the end of this year. This forecast includes restructuring deals reached outside the JI, which focuses on helping medium-sized firms restructure debts of $100–$500 million, while leaving the very large deals of $1 billion or more to be handled by the conglomerates and their creditors. If this prediction is fulfilled, it will demonstrate a remarkable acceleration of progress, which has so far been slow. As of 7 February 2000, only 19 firms had reached final binding restructuring agreements in the JI with their creditors, and only another 46 had reached even ‘in principle’ or informal standstill agreement with creditors. However, over 330 companies were enrolled in the JI. The aggregate debts of these companies appear to be less than one-third of total private sector indebtedness to non-residents.15

38 George Fane

and its creditors, and a final agreement is due to be announced soon. However, reports of the supposedly imminent announcement of this deal have been circulating for a long time.

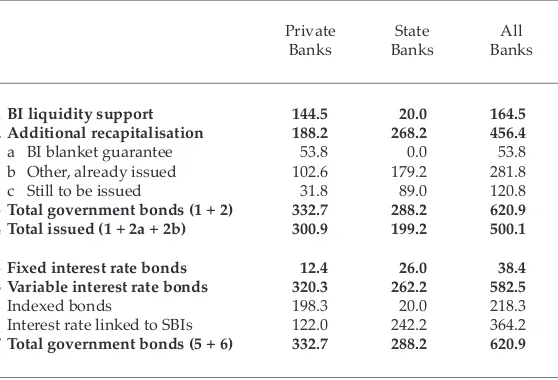

The Bank Bailout and IBRA’s Asset Management and Disposal Programs

In January 2000, Bank Indonesia estimated that the total amount of government bonds needed to recapitalise the banks would be Rp 621 trillion, which is 51% of GDP in FY 1999/2000.16 In aggregate, the private

banks account for just over half of the total—Rp 332.7 trillion, compared to Rp 288.2 trillion for the state banks and regional development banks (table 9). The estimate of the bonds needed has grown rapidly: just one year ago, it was only Rp 166 trillion, which included interest payments in FY 1999/2000 (Cameron 1999: 21).

The bonds comprise two parts: (1) those needed to replace the loans made by BI to banks that failed or were taken over; and (2) the additional bonds still needed to restore a capital to risk-weighted assets ratio (CAR) of 4%, which is the minimum permitted level until end-2001, by which time banks are supposed to have raised their CAR to 8%. The first part— repaying BI’s emergency liquidity support—comes to Rp 164.5 trillion. These bonds have already been issued. A further Rp 53.8 trillion has been issued to BI to refund amounts it paid out in 1998 and 1999 under the blanket guarantee. The remainder of the second part comes to Rp 402.6 trillion, of which Rp 281.8 trillion has already been issued. With about 80% of the bonds now issued, bank recapitalisation is at last nearing completion. However, since the bonds that make up the bulk of their assets are relatively illiquid, and since their CARs are only 4%, the banks still appear to be fragile.

The government is in the process of merging several of the banks that it has acquired. Four state banks—Bank Dagang Negara, Bank Bumi Daya, Bank Exim and Bank Pembangunan Indonesia—have already been merged to form Bank Mandiri, which is now Indonesia’s largest bank (JP, 26/1/2000). IBRA also plans to merge ten formerly private banks that it took over in August 1998 and May 1999. The largest of these, Bank Danamon, is to absorb the remaining nine. Bank PDFCI was merged into Danamon in December, and IBRA expects to complete the merger of the remaining eight banks into Danamon by the end of May (WSJ Interactive, 11/1/2000).

deputy, Mr Cacuk Sudarijanto. The slow progress was caused in part by the withdrawal of the Standard Chartered Bank from an agreement signed with IBRA in July 1999 to manage Bank Bali and to contribute the 20% private share of the new capital needed to raise its CAR to 4%. The agreement just survived the disclosure of the Bank Bali scandal, but Standard Chartered withdrew after a violent revolt by Bank Bali’s staff, who locked out the expatriate management team and accused them of racism—a charge that Standard Chartered strongly denied (AWSJ Interactive, 15/12/1999).

IBRA is scheduled to raise Rp 17 trillion in FY 1999/2000 and Rp 16.3 trillion in FY 2000 from asset sales and the earnings of its performing assets. As of early February 2000, it had raised only Rp 12 trillion of the target for FY 1999/2000. Roughly half of this amount came from the fact that the subscription to the rights issues made to recapitalise the private banks exceeded the 20% minimum share of the total cost of recapitalisa-TABLE 9 Government Bonds Needed to Bail Out and Recapitalise Commercial Banks

(Rp trillion)

Private State All

Banks Banks Banks

1 BI liquidity support 144.5 20.0 164.5 2 Additional recapitalisation 188.2 268.2 456.4

a BI blanket guarantee 53.8 0.0 53.8

b Other, already issued 102.6 179.2 281.8

c Still to be issued 31.8 89.0 120.8

3 Total government bonds (1 + 2) 332.7 288.2 620.9 4 Total issued (1 + 2a + 2b) 300.9 199.2 500.1

5 Fixed interest rate bonds 12.4 26.0 38.4 6 Variable interest rate bonds 320.3 262.2 582.5

Indexed bonds 198.3 20.0 218.3

Interest rate linked to SBIs 122.0 242.2 364.2

7 Total government bonds (5 + 6) 332.7 288.2 620.9

40 George Fane

tion that the government insisted private shareholders must contribute if they were to retain an interest in a bank whose CAR was below 4%. The balance came from the earnings of its performing assets. IBRA plans to raise most of the remaining Rp 5 trillion needed to achieve the FY 1999/2000 target by selling its 30% stake in Bank Central Asia and its 45% stake in PT Astra International, one of Indonesia’s most prestigious companies.17

In January, IBRA reported that 19 of its 200 largest debtors, with outstanding debts of Rp 13 trillion, are now engaged in debt workouts and another 10, with Rp 10 trillion of assets, have submitted business plans and restructuring proposals. IBRA is currently negotiating with 1,000 corporations, in 200 business groups, representing 76% of its portfolio. By the end of March, it expected to have completed Rp 26 trillion of debt restructuring deals with corporate debtors (JP, 13/1/2000). Given its slow progress in the past, such claims need to be treated with caution.

Bank Central Asia (BCA)

IBRA acquired a 30% stake in BCA in 1998 after its owners, the Salim group and two of Soeharto’s children, failed to repay loans from BI. BCA was Indonesia’s largest private bank, with total assets of Rp 84.4 trillion, and 767 branches.

In its LOI sent to the IMF on 22 July 1999, the government stated (paragraph 28) that it expected the sale of IBRA’s stake in BCA to be completed during the last quarter of 1999. This target passed and IBRA did not register the IPO for BCA with the Capital Market Supervisory Agency, Bapepam, in time to get the deal done in February, as it had subsequently planned. Bapepam demands 45 days advance notice of IPOs, and IBRA did not register the IPO until January because of delays in improving BCA’s credit supervision department. A second potential problem was that Bapepam’s rules require newly listed companies to have made profits in each of the two years before listing, whereas BCA has made losses in each of these years. However, an exception was made for BCA because its losses were deemed to have been caused by the crisis, rather than by mismanagement, and because the Stock Exchange believed that it should not prevent the listing of companies with good prospects (JP, 4/2/2000). At the time of writing, IBRA expected the IPO for BCA to go through in March and to raise about Rp 3 trillion.

Astra International

The fortunes of the owners of PT Astra International have fluctuated with the fortunes of their banks. The founder of Astra, William Soeryadjaya, had to sell his controlling interest in the company to repay depositors after the collapse in December 1992 of Bank Summa, which was also owned by his family (MacIntyre and Sjahrir 1993: 12–16). The relatives and business associates of former President Soeharto bought most of the shares, and his close associate Bob Hasan became Astra’s President Commissioner in the mid 1990s.

The banking crisis of 1997–99 led to another change of ownership at Astra. Several of the major new (i.e. post–Bank Summa) shareholders pledged their Astra shares so that their banks could get liquidity support from BI during the crisis; others surrendered Astra shares in partial settlement of the debts of banks that had violated legal lending limits. As a result of the 1997–99 bank failures, about 45% of Astra’s shares are now held by IBRA, and it is possible that the wheel may be about to turn full circle, since the Soeryadjaya family is apparently part of one of the consortia now seeking to buy Astra.

A successful sale of its Astra shares was essential if IBRA was to meet its revenue targets for 1999/2000. The sale was also viewed as a test of IBRA’s capacity to handle the enormous task of liquidating the bad assets of the banking sector. IBRA had claims on 1.04 billion shares, or 45% of the total equity in Astra. Since the share price was about Rp 3,750 in February, IBRA’s total stake in Astra was therefore worth almost Rp 4 trillion. However, it was expecting to raise only about Rp 3 trillion from the initial sale, because its claims to some of its shares were encumbered. It proposed to sell these shares to the successful bidder at a later date, once it had established clear title to them.

In August 1999, IBRA entered into negotiations with an American investment consortium, led by Newbridge Capital and Gilbert Global Equity Capital Asia Ltd, which IBRA chose as its ‘preferred bidder’. IBRA claimed that the Astra management team was uncooperative with Newbridge/Gilbert’s attempts to obtain the information needed for a due diligence investigation, and called a meeting of shareholders on 8 February at which it dismissed Astra’s chief executive officer, Rini Soewandi, and her deputy, while retaining the rest of the management team.

42 George Fane

had made it the ‘preferred investor’. Following Newbridge/Gilbert’s failure to make this payment, IBRA terminated its exclusive agreement with Newbridge/Gilbert and invited other prospective bidders to make offers for Astra. At the time of writing it had received expressions of interest from over 30 investors and hoped to complete the sale in late March.

16 February 2000

NOTES

1 The annual growth rate is based on BI’s prediction of the level of GDP in the last quarter of 1999.

2 ‘Fixed investment’ means ‘gross fixed capital formation’ in table 1; ‘investment’ means ‘fixed investment’ plus ‘changes in stock’ (table 1).

3 In February 2000, for the first time since 1997, an Indonesian company was able to obtain a new offshore loan without relying on a guarantee from a foreign government or multilateral agency. BA Asia, a unit of Bank America Corporation, is managing a bank consortium that seeks to raise over $200 million for PT Indah Kiat Pulp and Paper Corporation. More than $100 million has already been pledged. The cost of the loan to the borrower will exceed the SIBOR (Singapore Inter-Bank Offer Rate) dollar interest rate by 5.4 percentage points per year for one-year loans and 6.4 percentage points per year for two-year loans (Basis Point, issue 368, 5/2/2000). Indah Kiat Pulp and Paper’s export revenues provide a natural hedge for the loan, which is also guaranteed by its parent, Asia Pulp and Paper. APP is incorporated in Singapore, but it is part of the Sinar Mas Group and its core business is in Indonesia; it is one of the few Indonesian groups not to have defaulted on its debts during the crisis. 4 The Bank Bali scandal was covered in the previous Survey (Booth 1999: 4–8). Bank Bali paid Rp 546 billion to PT Era Giat Prima (EGP) to handle its claim on IBRA for reimbursement—in accordance with the government’s January 1998 blanket guarantee of bank debts—of amounts owed to it by banks that had failed. Following EGP’s efforts on its behalf, Bank Bali received Rp 904 billion from IBRA. Many people had imagined that the government would automatically pay what it owed, and were shocked to learn that a private company like EGP could apparently have a large effect on the amount or the timing of the supposedly guaranteed payments. It was widely suspected that the payments involved corruption. Since EGP is partly controlled by the deputy treasurer of Golkar (the ruling political party at that time), it was also suspected that the payment to EGP included a large covert donation to Golkar. 5 Of this total, just over $4 billion was pledged by Japan, the World Bank and

6 Acknowledging the huge expenditure on the bailout as an on-budget expense would have been too transparent even for the IMF, which has been content to go along with the pretence that an expenditure is not an expenditure if it is paid for with bonds rather than cash. Ironically, this internationally accepted charade is closely analogous to the most important of the now defunct Indonesian accounting conventions, according to which a deficit was not a deficit if it was financed by borrowing, rather than by paying in cash. The new convention produces much larger errors than the old Indonesian one ever did, because most of the bank bailout is current expenditure—the assets acquired by the government are worth only a small fraction of the bonds issued—whereas the old Indonesian convention was applied only to development expenditures. Since the bank bailout comes to around half of annual GDP, the magnitude is also far bigger than any error produced by the now discarded Indonesian conventions.

7 It also excludes the planned IPO for Bank Mandiri, the new state bank discussed in the section on bank restructuring. The $1.2 to $1.5 billion that the government hopes to raise from this IPO is to be used to finance Bank Mandiri’s own expansion, rather than the national budget deficit. Bank Mandiri intends to use most of the new equity to finance loans to industrial firms, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises and firms engaged in debt restructuring and exporting.

8 The government offered 35% of the shares in Telkom in an IPO in 1995, but demand was lower than expected, and not all these shares were sold. 9 The household expenditure surveys referred to in this section are the official

Survei Sosio-Ekonomi Nasional (Susenas) carried out by the Central Statistical Agency (BPS). The 1998 estimate quoted here is Booth’s ‘adjusted’ estimate, i.e. it uses the same basket of goods to define the poverty line in both periods. 10 This estimate is derived from national accounts data on changes in consumption, together with estimates of the distribution of the population around the poverty line.

11 SSSP obtained the 20 to 21% starting point in mid 1998 by adjusting the estimates of two surveys not undertaken by BPS to put them on a comparable basis with the BPS estimates. Details are given in SSSP (1999).

12 The targeted fuel subsidies are quite different from the ‘fuel subsidies’ that are estimated in table 5 to cost Rp 18.3 trillion in FY 2000. The latter measure the revenue loss to Pertamina from acquiring petroleum at world market prices, refining it, distributing it and selling it at relatively low administered domestic prices.

13 SMERU receives contributions and technical support from the World Bank, AusAID, the European Union ASEM Fund and the US Agency for International Development.

44 George Fane

15 Indonesia’s total private sector external indebtedness was reported to be $72.46 billion (World Bank 1998), and the firms enrolled in the JI at 7 February 2000 had foreign currency debts of $23 billion and rupiah debts of Rp 14.7 trillion. However, although some of their rupiah debts are owed to non-residents, the firms enrolled in the JI probably account for less than one-third of total Indonesian private external debt, because some of the $23 billion of their foreign currency denominated debts are owed to Indonesian banks.

16 In February 2000, BI revised this estimate to Rp 639.2 trillion, but did not publish a breakdown that would allow a full updating of table 9.

17 Astra’s automotive division, which assembles Toyota and several other leading brands, generates about two-thirds of its revenue. Its other interests include electronics, agribusiness, financial services, heavy equipment and wood-based products.

REFERENCES

BI (Bank Indonesia) (1999), Indonesia’s Recent Economic and Monetary Development, Jakarta (mimeo).

Booth, Anne (1999), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 35 (3): 3–38.

Cameron, Lisa (1999), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 35 (1): 3–40.

MacIntyre, Andrew, and Sjahrir (1993), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 29 (1): 5–33.

Mackie, Jamie (1999), ‘Indonesia’s New “National Unity” Cabinet’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 35 (3): 153–8.

McLeod, Ross H. (1999), ‘Crisis-driven Changes to the Banking Laws and Regulations’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 35 (2): 147–54.

Nasution, Anwar (1995), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 31 (2): 3–40.

Pardede, Raden (1999), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 35 (2): 3–39.

Suryahadi, Asep, Sudarno Sumarto, Yusuf Suharso and Lant Pritchett (1999), ‘The Evolution of Poverty During the Crisis in Indonesia, 1996 to 1999’, Working Paper, SMERU, Jakarta.

SURVEY EXTRA

a collection of post-Survey developments compiled by Indonesia

Project staff

GDP was 5.8% higher in Q4 1999 than a year earlier, but still below its level as long as four years previously; investment spending was still less than half its level just after the crisis began. Inflation remains negligible, while the rupiah weakened a little to Rp 7,630/$ at the end of March. IBRA sold its 40% interest in Astra International at the end of March for about Rp 3.8 trillion, but postponed the sale of its shares in Bank Central Asia. The IMF postponed indefinitely its planned April disbursement of funds because of unsatisfactory progress on several fronts.

Yet another person charged with high level involvement in the Bank Bali scandal was set free, this time on a legal technicality; the prosecutor is appealing the decision. Another court has ruled that IBRA acted illegally in taking over Bank Bali, throwing its, and others’, rehabilitation into doubt. Mr Bob Hasan, business tycoon and close associate of former President Soeharto, was arrested on a charge of corruption. Soeharto himself failed to answer his second summons to appear for questioning in relation to alleged corruption, sparking a violent protest by students. Eventually he was questioned briefly at his residence in early April.

Strong protests have resulted in postponement of reductions in subsidies to fuel users. The lack of support for the reductions—even though the main beneficiaries of the subsidies are those relatively well off—is perhaps understandable: the fact that nobody has as yet been punished despite huge transfers of wealth to the rich from the general public in the course of the banking crisis makes people reluctant to accept even greater hardship.