Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:16

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

“Friending” Professors, Parents and Bosses: A

Facebook Connection Conundrum

Katherine A. Karl & Joy V. Peluchette

To cite this article: Katherine A. Karl & Joy V. Peluchette (2011) “Friending” Professors, Parents and Bosses: A Facebook Connection Conundrum, Journal of Education for Business, 86:4, 214-222, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.507638

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2010.507638

Published online: 21 Apr 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 2948

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.507638

“Friending” Professors, Parents and Bosses: A

Facebook Connection Conundrum

Katherine A. Karl

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, Chattanooga, Tennesse, USA

Joy V. Peluchette

University of Wollongong, Wollongong, New South Wales, Australia

The ever-growing popularity of Facebook has led some educators to ponder what role social networking might have in education. The authors examined student reactions to friend requests from people outside their regular network of friends including professors, parents, and employ-ers. We found students have the most positive reactions to friend requests from their mother or boss. Possible educational uses for Facebook, recommendations on Facebook etiquette for business educators, and directions for future research are discussed.

Keywords: authority figures, business education, Facebook, relationships, self presentation, social networking

As of April 2010, Facebook had 400 million active users, making it the world’s largest social networking site (Face-book, 2010; Sarno, 2009). Similar to other online social net-working sites (e.g., MySpace and Friendster), Facebook pro-vides a means for people to share information in an online profile and build connections with others by sending or ac-cepting friend requests. Although Facebook has prompts for different kinds of profile information (e.g., activities, inter-ests, relationship status, political affiliation, favorite music), users have considerable freedom to post any information or pictures of their choice. As the initial and primary users of Facebook, college students were generally carefree about what they posted on their profile, assuming that the chances of anyone other than fellow students or recent alumni see-ing their profile would be remote (Lupsa, 2006). However, the college student age group (18–24-year-olds) now makes up less than half of Facebook users and the fastest growing demographic are those 30 years old and older (Facebook, 2010). As a result, college students are receiving friend re-quests from sources that are outside their regular network of friends including parents, professors, and, in some cases, employers. Drawing from the self-presentation literature, the purpose of this study is threefold: to examine student

reac-Correspondence should be addressed to Katherine A. Karl, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, Department of Management, 615 McCallie Av-enue, Chattanooga, TN 37403-2598, USA. E-mail: Katherine-Karl@utc.edu

tions to such friend requests, to discuss possible educational uses for Facebook, and to provide recommendations on Face-book etiquette for use by business educators.

Self-Presentation in Social Networking Profiles

According to Goffman’s (1959) theory of self-presentation, humans are actors who stage daily performances in an at-tempt to manage the impressions of our audience. As actors, humans have the ability to choose the stage, props, and cos-tume to suit the situation. For most people, being onstage is different from being backstage. Most people are onstage when they interact with others in public or professional set-tings. Goffman noted that while onstage, performers typi-cally conceal certain behaviors, attitudes, and emotions. In contrast, when backstage, actors can loosen some of their self-imposed restrictions, relax, and be themselves. Addi-tionally, there is a critical barrier that separates the backstage from the frontstage, for if that barrier is crossed (i.e., an outsider intrudes into the backstage) it leads to a spoiled per-formance. Thus, access to the backstage is usually limited to a very select and small group. According to Donath and Boyd (2004), humans use time and space “in the physical world” (p. 78) to separate the incompatible aspects of our lives and we may even carefully organize our activities to prevent over-lap. However, in the virtual world, an individual’s social net-work friends are in one virtual space. And even though users can now classify people into specific groups such as friends,

FACEBOOK CONNECTION CONUNDRUM 215

coworkers, or relatives, and grant each category a different level of access to various items, Facebook’s default setting is “share” and, according to Facebook’s chief privacy offi-cer, only about 20% of users change their privacy settings (Stross, 2009). As a result,friendsnow means a hodgepodge of real friends, former friends, friends of friends, coworkers or colleagues, relatives of all ages, and perhaps even a boss or professor. Thus, for most Facebook members (80%), there is no separation between the backstage and the front stage.

Besides dealing with the dilemma of mixing diverse groups of friends and acquaintances in one forum, individ-uals face an even more awkward situation when receiving a friend request from an authority figure. What should I do if my professor, my boss or my mother sends me a friend request? If I accept the request, then this person has access to my profile and all of my personal information, some of which I may not be comfortable with being seen by this person. If I deny or ignore the request, the person being snubbed may retaliate in some way that harms me or it may damage the real-life relationship I have with that person. So, what does one do when faced with a friend request from a professor, boss, or mother? We address this question in the next several sections of this article.

Friend Requests From a Professor

College and university administrators and faculty have al-ways had legitimate access to Facebook by virtue of having an “.edu” suffix in their email address. Initially, some admin-istrators accessed the site and used it for disciplinary reasons, such as to identify underage drinking or other violations of university codes of conduct (Woo, 2005). More recently, ad-ministrators and college faculty have taken a more positive approach and are using Facebook to build connections with students (Heiberger & Harper, 2008). For example, many schools including the Southern Illinois University College of Business in Carbondale and the University of Western On-tario’s Richard Ivey School of Business have formed their own Facebook groups to share news and communicate with students (Campbell, 2008; Damast, 2008). In addition, one study reported that 21% of colleges are using social network-ing sites in their efforts to recruit students (Hechnetwork-inger, 2008; Wandel, 2008). Likewise, professors have found Facebook to be a useful communication tool (Bollman & Wright, 2008; Soder, 2009). For example, one faculty member was quoted as saying, “I had e-mailed a student about coming in for a meeting. I waited three days with no response. I tried con-tacting the same student through Facebook and received a response in fifteen minutes” (Berg, Berquam, & Christoph, 2007, p. 34). On other campuses, faculty members have cre-ated Facebook groups for their classes to facilitate commu-nication (Sacks, 2009; Wolfe, 2009).

Research on the use of Facebook for educational purposes has been limited. Most of this literature has focused on the unprofessional content of students’ Facebook profiles and the

need to provide students with social media guidelines (e.g., Cain, Scott, & Akers, 2009; Chretien, Greysen, Chretien, & Kind, 2010; Foulger, Ewbank & Kay, 2009; Guseh, Brendel, & Brendel, 2009; McBride & Cohen, 2009; Peluchette & Karl, 2010; Thompson et al., 2008). However, others have suggested that Facebook could be used by educators to pro-mote learning outside the classroom. For example, Maloney (2007) suggested that the collaborative and active participa-tion characteristics of Facebook mirror what is known about good models of learning. Likewise, Schwartz (2010) sug-gested that Facebook interactions share many of the qualities of good mentoring relationships, including increased energy and well-being, potential to take action, increased knowledge of self and others, boost to self-esteem, and interest in more connection. In support, Cengage Learning (2007) surveyed 677 professors and found that 50% of them felt that social networking sites have or will change the way students learn. It is argued that if students use Facebook to share informa-tion about what a professor covered in class, they are con-tinuing to process the information and restructure it within their thoughts (Smith & Peterson, 2007). This was evident in a study by Schroeder and Greenbowe (2009), who found that students rarely used the bulletin board and chat func-tions of WebCT, so they examined whether a course-related Facebook group would be a viable alternative. In their study of 128 undergraduates enrolled in an introductory organic chemistry laboratory, they found that, although 59% did not join the Facebook group, the number of posts on Facebook was nearly 400% greater. In addition, they noted that Face-book postings raised more complex topics and generated more detailed replies than those on WebCT.

Although Facebook has been found by many to be an easy and convenient communication tool, there have been many others who have avoided student contact through Facebook. Similar to Goffman’s (1959) concept of the backstage, some college faculty members believe that sending friend requests to one’s students crosses too many boundaries (Haynesworth, 2009; Young, 2009). For example, one said, “it can be a case of ‘[too much information]’. . . I am learning things

about my students that I did not want to know” (Bollman & Wright, 2008). Another faculty concern is the unequal power distribution between faculty and students. Sacks (2009) and Haynesworth (2009) reported that faculty members believe that extending friend requests to students would put students in an awkward position. For example, one faculty member said, “Would you ever say no to a professor?” and another said “I don’t actively friend students so they don’t think I’m weird. . .the student might experience that as a form of

pressure.”

We identified five studies that examined student–faculty relationships on Facebook. After finding a Facebook group called “Screw Blackboard. . .Do it on Facebook!” with the

introductory statement “I spend most of my waking life on Facebook, sad so it may seem, I admit it proudly! Most of my lecture content is stuck on blackboard. . .so why not get

the university to shut blackboard and move everything to Facebook,” Selwyn (2007) studied the content of students’ Facebook pages to see how and to what extent students were using Facebook for educational purposes. His anal-ysis revealed that very little content was related to their academic studies. Those postings that were educationally related tended to involve disengagement (e.g., “essay not go-ing well. Arghhhhh!”) or disgruntlement (e.g., “oh I had clive last year. . .I don’t have him this year but wud kill myself if

I ever had him again!!!! I have some other rubbish lecturers but he is the damn SOUR cherry on the top!!!!!!!”). Selwyn concluded that Facebook was being used by most students as a space for contesting the asymmetrical power relationship between students and the university and its faculty. Thus, Facebook was a source of empowerment for them and pro-vided them a platform with backstage opportunities to be disruptive, challenging, and resistant.

Other studies have focused on student reactions to fac-ulty Facebook presence. For example, Mazer, Murphy, and Simonds (2006) found that student reactions to the appropri-ateness of faculty having a Facebook profile were mixed, and 33% reported that it was somewhat inappropriate and 35% reported it was somewhat appropriate. Examples of nega-tive comments included “I think it is weird for a teacher to have one,” and “It should not be a ‘common bond’ between students and teachers because it opens a whole new line of teacher/student relationships.” Other students made neg-ative comments regarding a lack of professionalism. How-ever, Sturgeon and Walker (2009) found a more positive reaction to faculty presence on Facebook. They surveyed 72 faculty and 74 students and found that most students agreed that they were more likely to communicate with faculty if they had a Facebook profile and that they feel an additional connectedness in the classroom as a result of Facebook relations. Likewise, over 75% of the faculty sur-veyed agreed that students were more likely to approach them as a result of their having a Facebook profile. Inter-views with faculty also revealed that some thought Face-book was an effective means of opening lines of communi-cation between faculty and students. For example, one stated “Anything that helps students feel more comfortable in the classroom environment, where they can feel a connection with their instructors, opens the door to better understand-ing, better communication, and better learning” (Sturgeon & Walker, p. 4).

Likewise, Hewitt and Forte (2006) reported that 66% of their 102 student respondents who answered the question “Do you think faculty should be on Facebook?” indicated that faculty presence was acceptable. Many of the remaining 33% voiced concerns about privacy and that their profiles contained information they did not want professors to see. Some students voiced concern about student–faculty interac-tions remaining professional as opposed to social. For exam-ple, one student stated, “Faculty and students should remain separate when it comes to social functions.” Still, two thirds

of the students surveyed reported that they were comfort-able with having faculty on Facebook. Positive comments focused mainly on the idea that Facebook allowed for an al-ternate communication channel and that students might get to know professors better. However, it should be noted that Hewitt and Forte found that students gave very high ratings to both the faculty they had seen on Facebook and those they had not (i.e., the average overall rating was 4.7 on a scale of 1 to 5 for both groups). Thus, their study did not address student opinions of faculty who were not well liked nor did it address the issue of student reactions to friend requests from faculty. This raises some interesting questions. Would students react positively to friend requests if they came from faculty members they did not like? How would they react to a friend request from a faculty member they did not know? Cain et al. (2009) found that the majority of pharmacy stu-dents they surveyed (60.7%) did not want faculty members to friend them on Facebook. Therefore, we believe it is likely that, in these circumstances, students’ perceptions would be less positive.

Friend Requests From a Boss

Anecdotal evidence suggests most people agree it is alright for a boss to accept a friend request from a subordinate, but it is not appropriate for a boss to initiate such a request to a subordinate (Horowitz, 2008). For example, Diaz (2008) in-terviewed supervisors who voiced concerns such as, “when-ever you are in a power position, you have to be careful.” Others felt that an individual’s personal life should be kept separate from his or her work or professional life. In contrast, Rutledge (2008) claims there may be advantages to “friend-ing” the boss. For example, Facebook can be an opportunity for more personalized networking and these personal con-nections can become a major asset when you’re looking to move forward in your career or find a new job.

We identified four studies examining friend relationships in the workplace. DiMicco and Millen (2007) examined 48 Facebook profiles of IBM employees and then conducted follow-up interviews with eight employees. They found that employees seemed relatively unconcerned that coworkers or managers might be viewing their profiles. For example, one of their respondents reported that Facebook was for fun and he hoped that if his manager ever saw his profile, he would understand that it has “nothing to do with his professional life” (p. 385). Other respondents were unconcerned because they had intentionally cleansed their profiles before starting their jobs. Likewise, Lampinen, Tamminen, and Oulasvirta (2009) interviewed five medical students and five employees of a large IT company and concluded that individuals deal with the copresence of multiple groups in one virtual space by self-censorship and relying on the goodwill and discretion of other users.

In their study of Microsoft employees, Skeels and Grudin (2009) found that several participants experienced uneasiness

FACEBOOK CONNECTION CONUNDRUM 217

when “friended” by a senior manager. For example, one said, “It led to a dilemma because what do you do when your VP invites you to be his friend?” and another said “If a senior manager invites you, what’s the protocol for turning that down?” (p. 7). The authors noted that most respondents said they dealt with this tension of crossing status or power bound-aries by restricting what they posted; however they were still concerned about their friends’ postings, as exhibited by the following comment: “Can I rely on my friends to not put something incredibly embarrassing on my profile?” An even more awkward situation might be an individual accepting the boss’s friend request and then realizing that he or she may have friends that the boss should not know about. If the in-dividual then deletes the boss as a friend, what would be the consequences?

Finally, a survey of 1,203 social network users in the United Kingdom conducted by people search engine yasni.co.uk found that 86% did not want to be friends with their boss and 69% did not want to be friends with their colleagues. Seventy-eight percent reported their social net-working pages contained potentially embarrassing material but 94% reported the material would not be a problem if their parents, grandparents, or bosses did not want to add them as friends. Nearly 80% said they had received a friend request from someone they didn’t want to accept, but felt they had no choice ((Anonymous, 2009).

Friend Requests From a Mother

When Facebook first opened itself to the public in 2006, thus allowing parents to become members, many students protested by forming antiparent groups such as “Don’t Let My Parents onto Facebook” and “What happens in Col-lege Stays in ColCol-lege: Keep Parents Off Facebook” (Aratani, 2008; Krieger, 2009). One site, “For the Love of God—Don’t Let Parents Join Facebook” is reported to have 5,819 mem-bers (Davis, 2009). However, there is also evidence that the generation gap between Millennials (those born after 1982) and their parents is narrowing. More than two thirds of the millennial children surveyed by Howe and Strauss (2003) indicated that their parents were in touch with their lives and that it was easy to talk to them. In addition, a recent report by the Association for the Study of Higher Education indicated that the use of emails, cell phone calls, instant messaging, or phone texting are daily activities for most students and their parents (Wartman & Savage, 2008). It would appear that communication via Facebook would be a natural extension of this. In support, Tilley (2007) reported his experience ob-serving a male student in a college pub wearing a T-shirt with “I facebooked your Mom” printed on it. He added that due to the “unrelenting growth of social network sites, it really was not that uncommon to Facebook someone’s mom or have your own mom Facebook you.” Likewise, Aratani (2008) re-ported that more and more moms and dads are friending (or

attempting to friend) their sons and daughters, and also their sons’ and daughters’ friends.

Hypotheses

A consistent theme running through the previous literature reviewed, which is also consistent with Goffman’s (1959) self-presentation theory, is the notion of boundaries or sep-aration. It appears that most people believe it is appropriate to change a role, costume, and props to fit the situation, and that it is not appropriate to let everyone into an indivdiual’s backstage area. In addition, the issue of unequal power distri-bution appears to be important for faculty–student relation-ships and boss–subordinate relationrelation-ships. Students may have negative reactions receiving friend requests from their boss or professor but, at the same time, they may feel powerless to refuse such requests. Even though some students are likely to reject friend requests from all three authority sources (pro-fessors, bosses, and parents), we believe that students would have more negative reactions to friend requests from profes-sors and bosses than those from their parents. Therefore, we predicted:

Hypothesis 1(H1): Students would be more likely to have

negative reactions to a friend request from their boss or professor than their mother.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Students would be more likely to

ac-cept friend requests from their mother than their boss or professor.

METHOD

Sample

Volunteers were recruited from undergraduate management and business communication courses at a medium-sized Mid-western university and were given some minimal course credit for their particpation. Of the 300 surveys distributed, 208 were returned for a response rate of 69%. About 53% of the respondents were male (n=110) and the mean age was 22.5 years (SD=4.74). Approximately 87% (n=180) indi-cated they were business majors and the remaining indiindi-cated some other nonbusiness major. The average hours worked per week was 20, although there was considerable variation (SD=13.67).

Survey Instrument

The survey instrument consisted of four measures: (a) de-mographic items including gender, age, academic major, and hours worked per week, and social network usage; (b) re-action to a friend request from a boss, mother, unknown professor, and worst professor; (c) response to a friend re-quest from a boss, mother, or unknown professor; and (d) description of a boss, mother or worst professor.

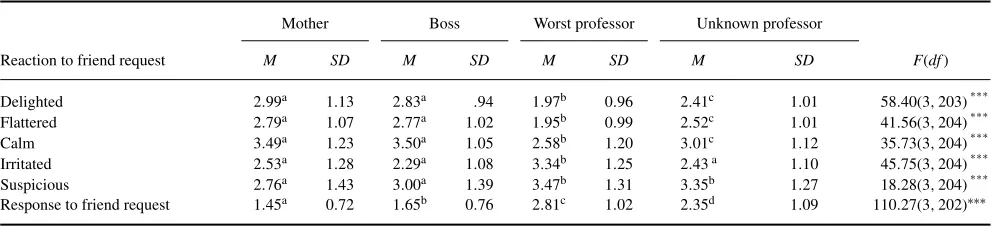

TABLE 1

Means, Standard Deviations, and ANOVA Results for Student Reactions and Responses to Friend Requests, by Source

Mother Boss Worst professor Unknown professor

Reaction to friend request M SD M SD M SD M SD F(df)

Delighted 2.99a 1.13 2.83a .94 1.97b 0.96 2.41c 1.01 58.40(3,203)∗ ∗ ∗ Flattered 2.79a 1.07 2.77a 1.02 1.95b 0.99 2.52c 1.01 41.56(3,204)

∗ ∗ ∗

Calm 3.49a 1.23 3.50a 1.05 2.58b 1.20 3.01c 1.12 35.73(3,204)∗ ∗ ∗

Irritated 2.53a 1.28 2.29a 1.08 3.34b 1.25 2.43a 1.10 45.75(3,204)∗ ∗ ∗ Suspicious 2.76a 1.43 3.00a 1.39 3.47b 1.31 3.35b 1.27 18.28(3,204)∗ ∗ ∗ Response to friend request 1.45a 0.72 1.65b 0.76 2.81c 1.02 2.35d 1.09 110.27(3,202)∗∗∗

Note.Responses were coded as 1 (accept as friend), 2 (accept as a friend, but with reservations), 3 (ignore, not respond), and 4 (respond that you do not know the person). Means with different superscripts are significantly different from one another.

∗∗∗p<.000.

Reaction to friend request. This measure included the following statement:

Assume you received the following email message from

Facebook—Mr./Ms. X (who is your [boss, mother,

pro-fessor for one of your preregistered classes whom you know nothing about, or the worst professor you have this semester]) added you as a friend on Facebook. We need you to confirm that you are, in fact, friends with Mr./Mrs. X. To confirm this friend request, follow the link below.

Respondents were then asked to indicate how they would feel if they received that email from their (i.e., boss, mom, unknown professor, or worst professor) using 5 items and a 5-point Likert-type rating scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The 5 items in-cluded delighted, flattered, calm, irritated, and suspicious.

Response to friend request. Respondents were asked to indicate what their response would be to each of the four friend requests. This measure included four options: (a) ac-cept as friend; (b) acac-cept as a friend, but with reservations; (d) ignore, not respond; and (d) respond that you do not know the person.

Description of boss, mother, or worst professor. In an attempt to examine possible explanations as to why stu-dents might have negative reactions to a friend request from their boss, mother, or worst professor, we also asked students to describe these individuals using a 4-item scale. Respon-dents were asked the following: “For each of the following items, please use the same scale as above to indicate the ex-tent to which you agree or disagree that each is an accurate description of (i.e., boss, mother, or worst professor).” The 4 items included: competent, trustworthy, fun, and ap-proachable. Coefficient alpha for the boss, mother, and worst professor scales were.78,.82, and.81, respectively. This scale was not used for the unknown professor because students would not be able to describe a professor they had not yet

had for class. Respondents were also asked to provide de-mographic information on their boss and worst professor including: gender, age, race, and marital status.

RESULTS

Means and standard deviations for student responses and re-actions to a friend request from their boss, mother, unknown professor and worst professor are shown in Table 1. To ex-amine the relative impact of the four different sources of friend requests on student reactions, we conducted six sepa-rate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with repeated measures in which the source of the friend request (i.e., unknown pro-fessor for whose class they have enrolled next semester, worst professor, boss, mother) was entered as the within subjects variable. Significant effects were found for all variables.

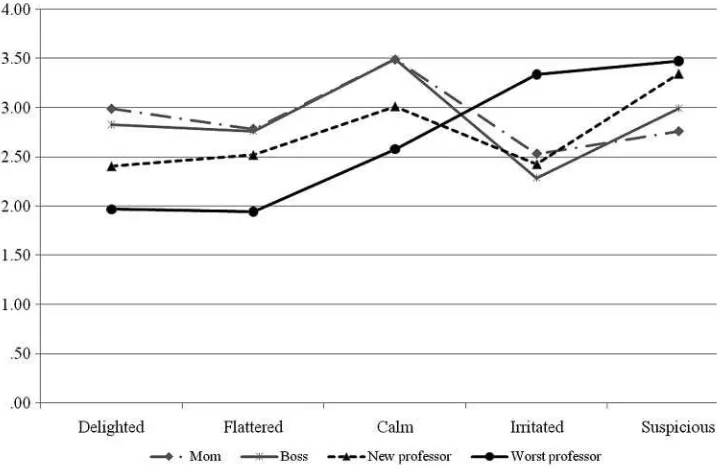

In Figure 1, we show the results of the reaction variables. ForH1, e predicted that students would be more likely to

have negative reactions to a friend request from their boss or professor than their mother. However, students in this study had relatively positive reactions to their mother and their boss, and less positive reactions to a new professor or their worst professor. More specifically, students had the most positive reactions (i.e., delighted, flattered, calm) to friend requests from their mother or boss and significantly less positive reactions to such requests from an unknown professor or their worst professor. Students, in general, were most suspicious of friend requests from their worst professor and an unknown professor and significantly less suspicious by such requests from their boss or mother. Students were most irritated by friend requests from their worst professor. Consistent with these findings, the results of the description scales showed that students, in general, described both their mother (M =4.19,SD=0.81) and their boss (M =3.96,

SD=0.83) favorably and their worst professor unfavorably (M=2.29,SD=0.92).

ForH2, we predicted that students would be more likely

to accept friend requests from their mother than their boss or

FACEBOOK CONNECTION CONUNDRUM 219

FIGURE 1 Student reactions to friend requests from their mother, boss, unknown professor, and worst professor.

professor. To test this, we conducted another ANOVA with repeated measures in which the source of the friend request (i.e., unknown professor for whose class they have enrolled next semester, worst professor, boss, mother) was entered as the within-subjects variable. To test for significant differ-ences between means, we selected the pairwise comparison option, which compares differences between the estimated marginal means and adjusts for multiple comparisons us-ing the Bonferroni test. These results show that there were significant differences among means for all four sources of friend requests,F(3, 606)=142.08,p<.000. Specifically,

students were most likely to accept friend requests from their

FIGURE 2 Percentage of response types by source of friend request.

mother (M=1.45,SD=0.73), followed by their boss (M=

1.65,SD =0.76), then an unknown professor (M =2.35,

SD=1.09), and they were least likely to accept one from their worst professor (M=2.81,SD=1.02). The percent-age of students who chose each type of response for each of the four sources of friend requests is shown in Figure 2. As indicated in Figure 2, students were most likely to ac-cept friend requests from their mother (67%), followed by their boss (51%), an unknown professor (27%), and worst professor (15%). Thus, H2was partially supported.

DISCUSSION

How might students react when they receive a friend request from their boss, mother, or professor? The results of this study suggest that students have the most positive reactions (delighted, flattered, calm) to friend requests from their boss or mother and the vast majority indicated that they would accept such a request from these sources. Given the close relationship that those in the millennial generation tend to have with their parents, we were not surprised by the findings of students’ reactions to friend requests from their mother. Even though we expected students to react negatively to such requests from their boss, students in this study rated their boss favorably. Thus, it is likely that students in this study had positive relationships with their boss and did not view friend requests from them as an intrusion of their privacy. For those not employed, it appears that students assume that their relationship with their potential/future boss would be a positive one and such action would not be seen as intrusive.

Students were most suspicious of friend requests from their worst professor or an unknown professor and students

were most irritated by requests from their worst professor. Although most students indicated that they would accept such a request from an unknown professor, they would have reservations about doing so and they would ignore a friend request from their worst professor. Receiving friend requests from these faculty sources was less appreciated by students because in both of these cases the relationship between the two parties was either less established or less positive. By ig-noring the friend request from the worst professor, students limit that faculty member’s access to their personal informa-tion and do not appear to be concerned about any potential consequences to their grade.

Implications

The results of this study have implications for both students and faculty. Faculty who are considering the use of Facebook as a means of communicating with their students should be cautioned in doing so as the results of this study suggest that many students are uncomfortable with having professors as Facebook friends. A considerable number of students agreed they would feel nervous, worried, suspicious, and concerned if they received a friend request from a professor. These find-ings lend some support to the advice provided earlier (e.g., Lipka, 2009) that it may be appropriate to accept a friend request from a student, but it is not appropriate for faculty to initiate such requests to students. Similarly, Schwartz (2010) argued for the importance of faculty being open to new tech-nologies but also setting boundaries. Instead of following her colleagues’ policy of not interacting with students on Facebook, she takes a passive stance by accepting students’ friend invitations but not initiating them and only responding to student posts directed to her. She has found that students appreciate the accessibility and respect her boundaries.

It is also important for business school faculty to remind students that Facebook is no longer just for college students, and that their parents, college administrators, and maybe even their present or future boss are also Facebook members. Students should be advised of the importance of creating a front stage image on their Facebook pages that enhances rather than diminishes their chances of getting a job once they enter the job market and are at the mercy of Google searches of their name. Students should also be advised to use the Facebook privacy options. Finally, students should also be warned that others might judge them based on the friends they keep (Walther, Van Der Heide, Kim, Westerman, & Tong, 2008). Thus, they should be careful as to whom they accept as a Facebook friend.

Future Research

As noted previously, many of our student respondents were reluctant to accept friend requests from professors and many stated they felt uncomfortable by the request, it was an in-vasion of their privacy, or they felt that their personal life should be kept separate from their classroom life. However,

it is possible that faculty use of Facebook might be perceived more favorably by students if the professor took actions to mitigate these reactions prior to sending the friend request. For instance, the professor could provide an explanation in class as to the reason for the friend request prior to sending it and explain that Facebook would be used as a learning tool for the class, not as a surveillance tool. Favorable re-actions may be even more likely if the professor reminded students that they could adjust their privacy options so that the professor would have only limited access to their pro-file. Future researchers examining these possibilities should advise faculty on the use of Facebook for faculty–student interactions.

Student reactions to friend requests from professors may also depend on the professor’s popularity. Because past re-search by Hewitt and Forte (2006) examined student reac-tions to highly rated faculty, we only examined student re-actions to friend requests from their worst professor or an unknown professor. It is possible that most students would not be opposed to accepting friend requests from professors they respect and admire. Future researchers should examine the relationship between student evaluations of the profes-sor and student reactions to receiving a friend request from such a professor. Students’ negative reactions to professors using Facebook could be due to the fact that many students probably still believe Facebook should be for students only. As time passes, and friend requests from unlikely sources become more common, student attitudes may change. Also, if students become accustomed to using the privacy options, thus creating the same type of boundaries or separations in their virtual world that exist in the real world, their reactions may change.

In addition, research is needed to explore the reasons why students react and respond as they do. For example, how significant is the issue of the unequal distribution of power between students and faculty or their boss? Many of our re-spondents indicated they would feel awkward in rejecting a friend request from their boss or professor, but no one specifi-cally mentioned the issue of power, pressure, or intimidation. Is power an issue? Future researchers should examine student perceptions of the level and types of power (reward, coercive, legitimate, referent, expert, information) held by the source of the friend request and its relationship to student reactions and responses.

To conclude, we believe that this study has made some headway into furthering our understanding of social network-ing as user demographics evolve. Our findnetwork-ings provide impli-cations for management education, as well as opportunities for further research.

REFERENCES

Anonymous. (2009, April 29). Bosses unpopular as Facebook friends.The Globe and Mail (Canada), B20.

FACEBOOK CONNECTION CONUNDRUM 221

Aratani, L. (2008, March 3). When mom or dad asks to be a Face-book ‘friend’. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www. washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/03/08/AR20080308 01034 pf.html

Berg, J., Berquam, L., & Christoph, K. (2007). Social networking technolo-gies: A “poke” for campus services.EDUCAUSE Review,42(2), 32, 34, 36, 38, 40, 42, 44.

Bollman, M., & Wright, J. (2008, September 17). Professors and stu-dents come Facebook to Facebook. Lee Clarion. Retrieved from http://www.leeclarion.com/life/2008/09/17/professors-and-students-come-facebook-to-facebook/

Cain, J., Scott, D. R., & Akers, P. (2009). Pharmacy students’ Facebook ac-tivity and opinions regarding accountability and e-professionalism. Amer-ican Journal of Pharmaceutical Education,73(6), 1–6.

Campbell, D. (2008). Reaching students where they live.BizEd,7(3), 60–61. Cengage Learning. (2007, May 7).Many college professors see podcasts, blogs and social networking sites as a potential teaching tool. Retrieved from http://www.cengage.com/press/release/20070507.html

Chretien, K. C., Greysen, S. R., Chretien, J., & Kind, T. (2010). Online posting of unprofessional content by medical students.Journal of the American Medical Association,302, 1309–1315.

Damast, A. (2008). The Admissions Office finds Facebook. With an eye on the demographics, schools are seeking applicants through social network-ing sites.Business Week. Retrieved from http://www.businessweek.com. mx/bschools/content/sep2008/bs20080928 509398.htm?chan=bschools

bschool+index+page getting+in

Davis, A. (2009). Friended by mom and dad on Facebook. Students worry about parental snooping, devise ways to protect privacy. ABC News on Campus. Retrieved from http://abcnews.go.com/OnCampus/ story?id=6555853&page=1

Diaz, J. (2008, April 16). Facebook’s squirmy chapter. Site’s evolution blurs line between boss and employee.The Boston Globe.Retrieved from http://www.boston.com/lifestyle/articles/2008/04/16/facebooks squirmy

chapter/

DiMicco, J. M., & Millen, D. R. (2007). Identity management: Multiple presentations of self in Facebook.Proceedings of GROUP 2007, 383–386. Donath, J., & Boyd, D. (2004). Public displays of connection.BT Technology

Journal,22(4), 71–82.

Facebook. (2010).Company statistics. Retrieved from http://www.facebook. com/press/info.php?statistics

Foulger, T. S., Ewbank, A. D., & Kay, A. (2009). Moral spaces in Myspace: Preservice teachers’ perspectives about ethical issues in social network-ing.Journal of Research on Technology in Education,42(1), 1–28. Goffman, E. (1959).The presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City,

NY: Double Day Anchor.

Guseh, J. S., Brendel, R. W., & Brendel, D. H. (2009). Medical profession-alism in the age of online social networking.Journal of Medical Ethics, 35, 584–586.

Haynesworth, L. (2009). Faculty with Facebook wary of friend-ing students. The Daily Princetonian. Retrieved from http://www. dailyprincetonian.com/2009/02/18/22793/

Hechinger, J. (2008). College applicants, beware: Your Facebook page is showing.Wall Street Journal (Eastern Edition),252(67), D1, D6. Heiberger, G., & Harper, R. (2008). Have you facebooked Astin lately?

Using technology to increase student involvement.New Directions for Student Services,124(Winter), 19–35.

Hewitt, A., & Forte, A. (2006, November).Crossing boundaries: Iden-tity management and student/faculty relationships on the Facebook. Paper presented at the Computer Supported Cooperative Work Confer-ence, Banff, Alberta, Canada. Retrieved from http://basie.exp.sis.pitt.edu/ 710/1/Crossing Boundaries Identity Management and Student Faculty Relationships on the Facebook (14).pdf

Horowitz, E. (2008). Befriending your boss on Facebook.The Age. Re-trieved from http://thebigchair.com.au/news/career-couch/befriending-your-boss-on-facebook

Howe, N., & Strauss, W. (2003).Millennials go to college: Strategies for a new generation on campus. Washington, DC: American Association of Collegiate Registrars.

Krieger, L. M. (2009, March 29). Don’t worry, kids, Stanford will teach Mom, Dad about Facebook. Mercury News. Retrieved from http://www.mercurynews.com/topstories/ci 11648461

Lampinen, A., Tamminen, S., & Oulasvirta, A. (2009). “All my people right here, right now”: Management of group co-presence on a social networking site.Proceedings of GROUP 2009, 281–290.

Lipka, S. (2007). For professors, “friending” can be fraught.Chronicle of Higher Education,Chronicle of Higher Education54(15), A1.

Lupsa, C. (2006, December 13). Facebook: A campus fad becomes a campus fact. The social-networking website isn’t growing like it once did, but only because almost every US student is already on it.The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved from http://www.csmonitor.com/2006/1213/p13s01-legn.html

Maloney, E. J. (2007). What Web 2.0 can teach us about learning.The Chronicle of Higher Education,53(18), B26–B27.

Mazer, J. P., Murphy, R. E., & Simonds, C. J. (2007). I’ll see you on ‘Facebook’: The effects of computer-mediated teacher self-disclosure on student motivation, affective learning, and classroom climate. Communi-cation EduCommuni-cation, 56, 1–17.

McBride, D., & Cohen, E. (2009). Misuse of social networking may have ethical implications for nurses.ONS Connect,24(7), 17.

Peluchette, J., & Karl, K. (2010). Examining students intended image on Facebook: “What were they thinking?”Journal of Education for Business, 85, 30–37.

Rutledge, P. (2008).The truth about profiting from social networking. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Sacks, I. (2009, February 23). Student, professor Facebook friend-ships bring communication, risks. The Maneater. Retrieved from http://www.themaneater.com/stories/2009/2/23/student-professor-facebook-friendships-bring-commu/

Sarno, D. (2009, September 16). Facebook reports milestones in cash flow, users.Los Angeles Times, B4.

Schroeder, J., & Greenbowe, T. J. (2009). The chemistry of Facebook: Using social networking to create an online community for the organic chemistry.Innovate: Journal of Online Education,5(4), 1–7.

Schwartz, H. L. (2009). Facebook: The new classroom commons?Chronicle of Higher Education,56(6), B12–13.

Selwyn, N. (2007). ‘Screw Blackboard... do it on Facebook!’: An in-vestigation of students’ educational use of Facebook. Retrieved from http://www.scribd.com/doc/513958/Facebook-seminar-paper-Selwyn Skeels, M. M., & Grudin, J. (2009). When social networks cross boundaries:

A case study of workplace use of Facebook and LinkedIn.Proceedings of GROUP 2009, 95–104.

Smith, R., & Peterson, B. (2007). Psst. . .what do you think? The relation-ship between advice prestige, type of advice, and academic performance. Communication Education,56, 278–291.

Soder, C. (2009, July 27). Social media extend search for prospective stu-dents; Universities build relationships, canvass recruits with Facebook, other online tools.Crain’s Cleveland Business, 0012.

Stross, R. (2009, March 8). When everyone’s a friend, is anything pri-vate? The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/ 2009/03/08/business/08digi.html? r=2&pagewanted=print

Sturgeon, C. M., & Walker, C. (2009, March).Faculty on Facebook: Confirm or deny?Paper presented at the 14th Annual Instructional Technology Conference, Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

Thompson, L. A., Dawson, K., Ferdig, R., Black, E. W., Boyer, J., Coutts, J., & Black, N. P. (2008). The intersection of online social networking with medical professionalism.Journal of General Internal Medicine,23, 954–957.

Tilley, S. (2007, August 17). Facebook even a mother can love. The Toronto Sun. Retrieved from http://cnews.canoe.ca/CNEWS/ MediaNews/2007/09/16/4501290-sun.html

Walther, J. B., Van Der Heide, B., Kim, S., Westerman, D., & Tong, S. T. (2008). The role of friends’ appearance and behavior on evaluations of individuals on Facebook: Are we known by the company we keep? Human Communication Research,34, 28–49.

Wandel, T. (2008). Colleges and universities want to be your friend: Com-municating via online social networking.Planning for Higher Education, 37(1), 35–48.

Wartman, K., & Savage, M. (2008). Reasons for parental involvement. As-sociation for the Study of Higher Education Report,33(6), 7–19. Wolfe, K. (2009).Facebook: Not just for students. What started as a college

networking site now has University faculty jumping on the bandwagon.

Retrieved from http://www.mndaily.com/2009/02/25/facebook-not-just-students

Woo, S. (2005). The Facebook: Not just for students. Administrators at other schools disciplining, hiring students based on Web site profiles.The Brown Daily Herald.Retrieved from http://media.www.browndailyherald.com/ media/storage/paper472/news/2005/11/03/CampusWatch/The-Facebook. Not.Just.For.Students-1044229.shtml

Young, J. R. (2009). How not to lose face on Facebook, for pro-fessors. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from 0 http://chronicle.com/free/v55/i22/22a00104.htm