Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:01

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Undergraduate Business Education: It's Time to

Think Outside the Box

John Duncan Herrington & Danny R. Arnold

To cite this article: John Duncan Herrington & Danny R. Arnold (2013) Undergraduate Business Education: It's Time to Think Outside the Box, Journal of Education for Business, 88:4, 202-209, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.672934

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2012.672934

Published online: 20 Apr 2013.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 310

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.672934

Undergraduate Business Education: It’s Time

to Think Outside the Box

John Duncan Herrington

Radford University, Radford, Virginia, USA

Danny R. Arnold

Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida, USA

For more than 100 years, institutions of higher learning in the United States have provided millions of students with an education in business. Presently, business ranks as one of the most popular undergraduate majors on American college campuses, awarding over 20% of all undergraduate degrees granted each year. Despite its popularity, many people question whether these students receive the type of education needed to effectively compete in a rapidly changing world. The authors report the findings of an extensive study of undergraduate business curricula in the United States, the results of which suggest that very little has changed since the Ford and Carnegie Foundations Reports were published in 1959. The authors conclude with some suggestions on how to improve business education for future graduates.

Keywords: business, curriculum, undergraduate

The University of Pennsylvania established the first formal school of business in 1881 (Van Fleet & Wren, 2005). The13 business programs in existence in the United States prior to 1913 (Pierson, 1959) grew to approximately 1,500 by 2010. During this time the number of students receiving a bache-lor’s degree in business from U.S. colleges and universities grew from just under 43,000 during the 1955–1956 academic year to approximately 348,000 during 2008–2009 (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2010). Almost 22% of all Bachelor’s degrees granted in the United States during 2008–2009 were granted in business.

This rapid growth helped encourage more intense scrutiny, both from inside and outside the Business Academy. The Ford and Carnegie Foundations sponsored two of the ear-liest comprehensive reviews and critical analyses of busi-ness education in America, typically referred to as the Gor-don and Howell (1959) and Pierson (1959) studies. Almost 30 years later, the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business International (AACSB) commissioned an addi-tional comprehensive study (Porter & McKibbin, 1988). All three reports have provided the business academy with

sig-Correspondence should be addressed to John Duncan Herrington, Rad-ford University, College of Business and Economics, Box 6950, RadRad-ford, VA 24142, USA. E-mail: dherring@radford.edu

nificant guidance for improving undergraduate business ed-ucation. The following provides a brief summary of some of the key findings and recommendations provided by the three reports.

First, Gordon and Howell (1959) found that business pro-grams did not require enough mathematics. They reported that only 63% of business programs had any math require-ment. The remaining programs required only business math (22%) or no math at all (15%). Many of the business math classes at that time covered only basic arithmetic and/or fi-nancial calculations.

Second, both the Ford and Carnegie Foundation reports suggested that programs required too many credit hours in business courses and allowed too much latitude regard-ing specific course requirements. Pierson (1959) noted that anywhere from 17 to 22 different core areas from which schools required students to take courses. The eight most commonly required business subjects were: accounting, fi-nance (banking), business law, economics, marketing, statis-tics, management–policy, and production. The number of credit hours required in core business courses ranged any-where from fewer than 30 to more than 54.

Porter and McKibbin (1988) reported the findings of two separate surveys conducted in the mid-1980s. The first, a survey of AACSB International member institutions, can be summarized as follows. First, respondents felt that programs

THINKING OUTSIDE THE BOX 203

were lacking in integration across the various functional ar-eas. Second, programs placed too much emphasis on prob-lem solving and not enough on probprob-lem finding (i.e., vision) and, further, too little emphasis on managing people (e.g., leadership, interpersonal skills), communication skills, ex-ternal environments, international dimensions of business, entrepreneurship, and ethics. Based on the findings of a sep-arate survey of corporate executives, Porter and McKibbin reported that many executives felt that quantitative require-ments were somewhat adequate. But, they also felt that the business curriculum should be more realistic, practical, and hands-on and needed to place more emphasis on soft skills (e.g., leadership, interpersonal skills).

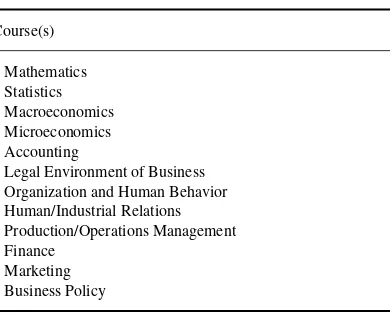

Presently, three organizations in the United States offer-ing accreditation of business programs provide recommen-dations regarding both the subjects and credit hours business programs should require in their core curricula: AACSB In-ternational, the Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs (ACBSP), and the International Assembly for Collegiate Business Education (IACBE). Gordon and Howell (1959) and Pierson (1959) each provided suggestions regard-ing what courses and credit hours should be required of all business majors, which are summarized in Table 1. Com-pared to the business core of 1955–1956, the most prominent recommended changes included adding 6–12 credit hours of mathematics (e.g., algebra, finite, and/or calculus), the inclu-sion of more behaviorally oriented subjects in management, and the delegation of courses in business communication to non-business academic areas (e.g., English, communica-tions).

While the reports differed in how many credit hours should be required for some subject areas, both suggested that at least one-half of the credit hours required for a degree in business should be non-business. Gordon and Howell (1959) further suggested that the common business core alone should

con-TABLE 1

Suggested Business Core Curriculum: Carnegie and Ford Foundations Reports

Course(s)

•Legal Environment of Business

•Organization and Human Behavior

•Human/Industrial Relations

•Production/Operations Management

•Finance

•Marketing

•Business Policy

Note.Adapted from Gordon and Howell (1959) and Pierson (1959).

TABLE 2

Summary of Competencies Desired of Business Graduates by Employers

Most frequently mentioned competencies

•Business expertise

•Motivation and commitment to firm

•Problem solving

Note. Sources are Harper (1987); Tanyel, Mitchell, and McAlum (1999); Abraham, Karns, Shaw, and Mena (2001); Abraham and Karns (2009); and Wickramasinghe and De Zoyza (2009).

sist of no more than 30–40% of the requirements for a four-year degree.

One of the key stakeholder groups to which business pro-grams are accountable consists of the organizations that offer employment to the millions of students who have or will re-ceive a business degree. While not a complete and exhaustive list, Table 2 provides a summary of some of the more com-monly mentioned competencies employers expect to see in prospective employees.

In summary, the past 50 years have been a time of much research, debate, and no small degree of angst within the business academy. Beginning in earnest with the Ford and Carnegie Foundations reports, the academy as a whole has devoted much time and effort towards developing business curricula worthy of professional status. Big questions remain, such as the following: (a) what progress has actually been made?, and (b) has it been enough? In the sections that follow we report the results of a comprehensive study of four-year business programs in the United States, followed by some recommendations that may serve to guide future research and development in the area of business education.

METHODOLOGY

Despite diligent search, no single source provides a complete listing of all institutions offering bachelor’s degrees in busi-ness in the United States. Subsequently, a variety of sources were used, including the membership rosters of recognized U.S. accreditors approved by the Council for Higher Ed-ucation Accreditation (e.g., AACSB International, ACBSP,

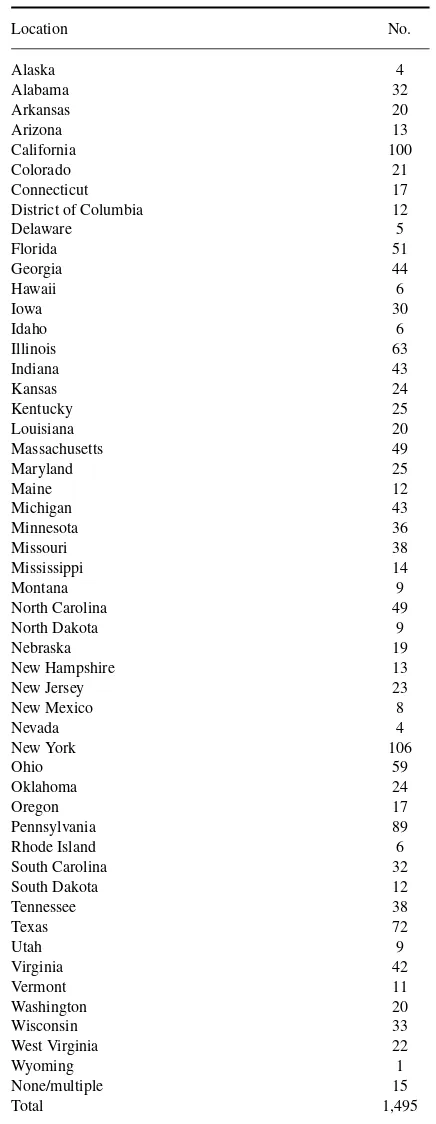

TABLE 3

Number of Colleges and Universities Offering 4-Year Degrees in Business by State

Location No.

District of Columbia 12

Delaware 5

IACBE, Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools), Peterson’s Guide to Four-Year Colleges, several Internet-based college directories (e.g., collegiateguide.com), and serendipity. The data used for this analysis consisted of

busi-ness program requirements in effect for the 2010–2011 aca-demic year, and were collected from official program web-sites, catalogs, and bulletins between August 2010 and April 2011.

The investigation identified 1,495 different institutions (not including branch campuses) offering bachelor’s degrees in business (see Table 3). All but one of the identified pro-grams were accredited at the institutional level by one or more organizations recognized by the Council for Higher Educa-tion AccreditaEduca-tion. Forty-nine percent held separate accredi-tation of their business programs—30% by the AACSB and 19% by either the ACBSP and/or IACBE.

Prior to sample selection, the total population of 1,495 known institutions offering one or more four-year business degrees was stratified into three groups: (a) programs holding accreditation by AACSB, (b) programs holding accreditation by ACBSP or IACBE, and (c) all other programs. A random sample was selected from each of the three groups resulting in a total sample of 623, which is an appropriate sample size to yield a maximum 5% sampling error overall and within strata. The sample included programs located in all 50 states as well as the Washington, DC.

FINDINGS

The analyses that follow include group comparisons ex-pressed in terms of either proportions or means. For propor-tions, the chi-square statistic was used as an overall measure of difference among groups and the Marascuilo procedure (Marascuilo, 1966) was used to determine individual pair-wise group differences. Analysis of variance was used to compare overall group means followed by the least signifi-cant difference (LSD) procedure for means comparisons.

Business Core Courses

The results of this study suggest that the number of credit hours required in business core courses increased between

TABLE 4

Semester Hours Required in Business Core: 1955–1956 Compared to 2010–2011

Percentage of programs

Semester hours 1955–1956 2010–2011

Under 30 10.6 3.0

Note.Data from 1955–1956 (n=132) were adapted from

Pier-son (1959). Estimate from 2010–2011 (n=623) was obtained by

multiplying course count by 3.

THINKING OUTSIDE THE BOX 205

TABLE 5

Business Core Requirements (n=632)

Number of required business core courses

Accreditation M δ LSD means comparisons

AACSB 15.72 2.298 b

ACBSP/IACBE 16.10 3.334 c

Other 14.90 4.135

All programs 15.49 3.428

Note. F(2, 620)=6.915,p=.001. Business math courses excluded mathematics. Least significant difference (LSD) group comparisons were

the following: a=group 1 is different from group 2 at the .05 level of

significance or higher; b=group 1 is different from group 3 at the .05 level of significance or higher; c=group 2 is different from group 3 at the .05 level

of significance or higher. AACSB=Association to Advance Collegiate

Schools of Business International; ACBSP=Accreditation Council for

Business Schools and Programs; IACBE=International Assembly for

Collegiate Business Education.

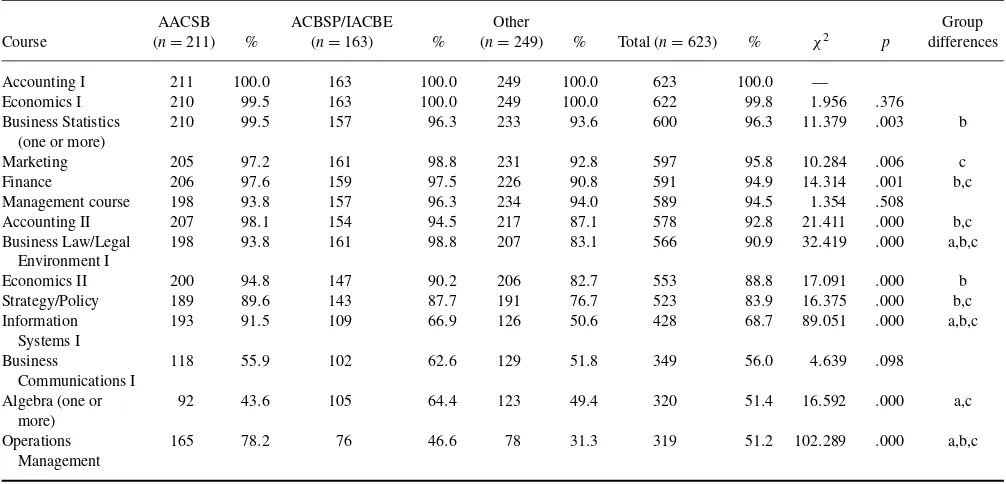

1955 and 2010 (Tables 4 and 5), yet most programs were able to do so without exceeding 50% of the credit hours required for a degree. In addition, programs seem to have become more consistent in terms of business core courses (Table 6). Information systems, business communications and a management course (separate from business policy) were the only courses added to the original list of eight business core courses identified by Pierson (1959). However,

there remain 14 additional business courses required by 5% or more of business programs (Table 7).

In summary, curriculum change has occurred, yet it would be difficult to contend that the list now includes all of the courses that should be included in the business core. Other important topics potentially missing from the list of core business courses include interpersonal skills, teamwork, in-ternational business, ethics, and experiential and business integration, to name but a few—all of which are presently required by fewer than 50% of business programs.

The typical business core of 2010 (Table 6) may not ade-quately address all of the competencies desired by employers (Table 2). Certainly the competencies relating to communica-tions, analytical skills, and business expertise (via functional courses) are generally covered. As for the remaining compe-tencies, it can only be guessed, as there seem to be few clear connections with any given course title or description. Recent research seems to call into question whether these compe-tencies are adequately addressed (Abraham & Karns, 2009). For example, employers have noted that business programs have not done well at providing students with opportunities to gain hands-on experience prior to entering the workforce. While most business programs offer internships, very few (15%) require them. One does not have to look far to find examples of professors requiring students to engage in real-world projects as a course requirement, yet the extent to which such activities were practiced is not clear.

TABLE 6

Courses Required by 50% or More of Business Programs

Course

Note.Group differences using the Marascuilo procedure were the following: a=group 1 is different from group 2 at the .05 level of significance or higher;

b=group 1 is different from group 3 at the .05 level of significance or higher; c=group 2 is different from group 3 at the .05 level of significance or

higher. AACSB=Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business International; ACBSP=Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs;

IACBE=International Assembly for Collegiate Business Education.

TABLE 7

Courses Required by 5–49% of Business Programs

Course

AACSB

(n=211) %

ACBSP/IACBE

(n=163) %

Other

(n=249) % Total (n=623) % χ2 p

Group differences

Computer Literacy 95 45.0 94 57.7% 119 47.8 308 49.4 6.332 .042

Business Math (one or more)

83 39.3 69 42.3% 88 35.3 240 38.5 2.121 .346

Calculus (one or more)

155 73.5 24 14.7% 57 22.9 236 37.9 174.426 .000 a,b

International Business

73 34.6 77 47.2% 85 34.1 235 37.7 7.686 .021 a,c

Ethics 63 29.9 72 44.2% 91 36.5 226 36.3 8.164 .017 a

Introduction to Business

69 32.7 52 31.9% 64 25.7 185 29.7 3.195 .202

Human Resource Management

12 5.7 44 27.0% 51 20.5 107 17.2 32.536 .000 a,b

Internship 8 3.8 41 25.2% 44 17.7 93 14.9 35.502 .000 a,b

Finite Math 38 18.0 26 16.0% 25 10.0 89 14.3 6.424 .040

Career/ Professional Development

38 18.0 11 6.7% 23 9.2 72 11.6 13.593 .001 a,b

Economics III 24 11.4 12 7.4% 25 10.0 61 9.8 1.705 .426

Leadership 19 9.0 10 6.1% 22 8.8 51 8.2 1.240 .538

Accounting III 4 1.9 18 11.0% 27 10.8 49 7.9 15.695 .000 a,b

Excel 10 4.7 14 8.6% 24 9.6 48 7.7 4.098 .129

Systems/

Integration/Process

24 11.4 10 6.1% 11 4.4 45 7.2 8.638 .013 b

Information Systems II

8 3.8 13 8.0% 20 8.0 41 6.6 4.039 .133

Society/ Environment

19 9.0 5 3.1% 16 6.4 40 6.4 5.395 .067 a

Research 4 1.9 7 4.3% 24 9.6 35 5.6 13.643 .001 b

Money and Banking 9 4.3 8 4.9% 18 7.2 35 5.6 2.102 .350

Entrepreneurship 11 5.2 6 3.7% 17 6.8 34 5.5 1.927 .382

Business Law II 2 0.9 14 8.6% 16 6.4 32 5.1 12.434 .002 a,b,c

Business

Communications II

14 6.6 8 4.9% 10 4.0 32 5.1 1.631 .442

Note.Group differences using the Marascuilo procedure were the following: a=group 1 is different from group 2 at the .05 level of significance or higher;

b=group 1 is different from group 3 at the .05 level of significance or higher; c=group 2 is different from group 3 at the .05 level of significance or

higher. AACSB=Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business International; ACBSP=Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs;

IACBE=International Assembly for Collegiate Business Education.

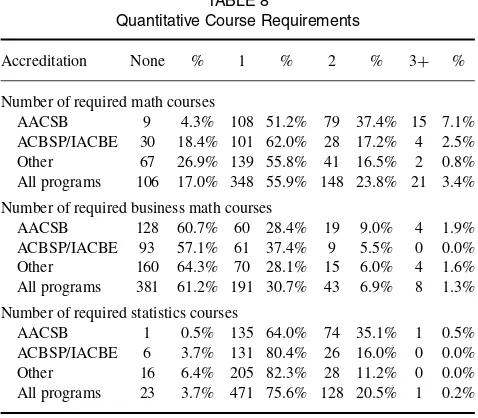

Some change in the number and level of math courses is evident. A total of 83% of programs required one or more math (excluding business math and statistics) classes (Table 8), compared to 73% in 1955. However, with an overall average of one required math course (Table 9), it seems that far too few programs have followed the advice of Gordon and Howell (1959), Pierson (1959), and many others who have advocated for increasing math requirements to 6–12 credit hours for business students—only 27% of programs required more than one math course and 17% required none. On the other hand, what passes for business math seems to have improved—the vast majority of courses categorized as business math in this study covered topics common to man-agement science rather than simple arithmetic, yet only 39% of programs required a business math course.

Credit Hour Requirements

To analyze credit hour requirements, subsamples consisting of 53 programs accredited by AACSB, 29 programs holding other business accreditation (ACBSP, IACBE), and 28 pro-grams that do not hold separate business accreditation were randomly selected from each of the three groups. Additional data were collected for these programs regarding total credit hours required for a degree and credit hours required for busi-ness core courses (excluding math and up to two semesters of economics). Data obtained for programs operating on the quarter system were converted to semester-hour equivalents prior to analysis.

For the subsample, the average number of credit hours required for a degree was 123 (SD=4.2 credit hours) with an average number of credit hours required in business core

THINKING OUTSIDE THE BOX 207

TABLE 8

Quantitative Course Requirements

Accreditation None % 1 % 2 % 3+ %

Number of required math courses

AACSB 9 4.3% 108 51.2% 79 37.4% 15 7.1%

ACBSP/IACBE 30 18.4% 101 62.0% 28 17.2% 4 2.5%

Other 67 26.9% 139 55.8% 41 16.5% 2 0.8%

All programs 106 17.0% 348 55.9% 148 23.8% 21 3.4%

Number of required business math courses

AACSB 128 60.7% 60 28.4% 19 9.0% 4 1.9%

ACBSP/IACBE 93 57.1% 61 37.4% 9 5.5% 0 0.0%

Other 160 64.3% 70 28.1% 15 6.0% 4 1.6%

All programs 381 61.2% 191 30.7% 43 6.9% 8 1.3%

Number of required statistics courses

AACSB 1 0.5% 135 64.0% 74 35.1% 1 0.5%

ACBSP/IACBE 6 3.7% 131 80.4% 26 16.0% 0 0.0%

Other 16 6.4% 205 82.3% 28 11.2% 0 0.0%

All programs 23 3.7% 471 75.6% 128 20.5% 1 0.2%

Note.For math courses,χ2(2)=80.0,p=.000; for business math,

χ2(2)=9.1,p=.166; for statistics,χ2(2)=52.5,p=.000.n=623.

AACSB= Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business

In-ternational; ACBSP=Accreditation Council for Business Schools and

Programs; IACBE=International Assembly for Collegiate Business

Edu-cation.

of 36 (SD=8.3 credit hours). With respect to the business core as a percentage of total credit hours required for a degree, the average among all schools was 29% and ranged from a low of 27% for programs that did not hold separate business accreditation to a high of 30% for programs holding AACSB accreditation. The only significant difference observed was between programs accredited by AACSB and the group of programs that did not hold separate business accreditation.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study can be viewed from at least two interrelated perspectives: the view from the trenches as well as the 30,000-ft view. The view from the trenches consists of faculty and administrators attempting to review their cur-ricula to determine its consistency with present practices. In that light, the data provide present norms, which can be used for benchmarking purposes. Business programs that do not presently require a course in information systems, for ex-ample, may wish to consider adding such a course to their curriculum because 69% of business programs have one. Al-ternately, a program presently requiring a course in money and banking may wish to evaluate whether the course is still relevant, as only 6% of other programs require such a course.

The 30,000-ft. view refers to that of the business academy as a whole, which is concerned with loftier issues relating to three basic questions. (a) Have business curricula changed in the last 50 years or so?; (b) Have they changed for the better?; and finally (c) Have they changed enough to address

TABLE 9

Quantitative Course Requirements for Business Programs

Accreditation M δ LSD means comparisons

Number of math courses

AACSB 1.47 .692 a,b

ACBSP/IACBE 1.05 .727 c

Other 0.91 .678

All programs 1.14 .737

Number of business math courses

AACSB 0.52 .739

ACBSP/IACBE 0.48 .602

Other 0.45 .683

All programs 0.48 .682

Number of statistics courses

AACSB 1.36 .499 a,b

ACBSP/IACBE 1.12 .427

Other 1.05 .418

All programs 1.17 .469

Note.Least significant difference (LSD) group comparisons were the

following: a=group 1 is different from group 2 at the .05 level of

sig-nificance or higher; b=group 1 is different from group 3 at the .05 level of significance or higher; c=group 2 is different from group 3 at the .05 level of significance or higher. Math courses included algebra, calculus, and finite. Business math courses included all math courses not clearly identi-fied as math or statistics, typically management science. For math courses,

F(2, 620)=39.085,p=.000; for business math,F(2, 620)=0.627,p=

.537; for statistics,F(2, 620)=27.989,p=.000. AACSB=Association to

Advance Collegiate Schools of Business International; ACBSP=

Accredi-tation Council for Business Schools and Programs; IACBE=International

Assembly for Collegiate Business Education.

the concerns expressed in the Carnegie and Ford Foundations reports (among others)?

It seems clear that overall, business curricula and practices have changed. In addition, many would probably agree that some improvements have occurred in the areas of mathemat-ics and business core requirements. Yet despite some evident progress, it appears that more could be done to improve undergraduate business education. In light of the continued growth in the demand for business degrees, it is critical that these issues be addressed. But what changes may be needed?

Curriculum Change: Outside the Box Thinking

As can be seen from the various tables and discussions, the business core in 2010 closely resembles that of 1955–1956. Despite encouragement from the various accrediting agen-cies regarding innovation in curriculum design, there have been few changes in the typical required core business courses. There are several possible explanations as to why. First, accrediting agencies generally try to encourage inno-vation, but business schools seeking to achieve or maintain accreditation are often risk-averse. Faculty and administra-tors look at what has worked in the past for other accredited business programs and see schools that offer the same list of

traditional core courses. So, they do the same thing, thereby perpetuating the business core of the 1950s.

Second, disciplinary turf protection may also play a role. Quite often, faculty members think of their discipline as the most important one in business. In addition, most business programs maintain two or more separate academic depart-ments, from which business core courses are staffed and scheduled. At many institutions the number of faculty posi-tions (as well as operating budgets) available to an academic department is contingent upon the number of courses and credit hours offered. Consequently, faculty often exert great effort to maintain the status quo relative to the number of credit hours required within academic departments in order to protect silos.

In addition, many faculty and administrators appear to resist change. Faculty members presently serving in higher education generally have received their academic prepara-tion within the last fifty years, during which there has been little change in business core courses. Since many faculty members tend to teach what they have been taught in the manner in which it was taught to them, the status quo re-mains the norm. The resulting lack of inertia perpetuates the cookie-cutter curriculum.

Further, a number of the concerns reported by Porter and McKibbin (1988)—such as the lack of integration and too little emphasis on problem finding, international dimensions, entrepreneurship, and practical experience—have seemingly not been widely addressed. Nor have many of the other competencies considered important by employers (e.g., motivation and commitment to firm, creativity, quality focus, customer focus, ethics–integrity, teamwork, flexibility, and interpersonal skills, to name but a few). Why? Perhaps one of the greatest reasons is that no academic department owns these competencies. For example, there appear to be few if any Departments of Business Integration. As a result, such competencies remain in limbo unless covered under the broader rubric of one of the traditional business core courses. From a broader perspective, the inadequacies of business education may be more systemic. Ghoshal (2005) suggested that much of what is wrong in business today results from problems associated with what students have learned, or not, in business courses. Further, much of what is wrong in business courses (academe) stems from problems related to management research–theory and pedagogy. There seems to be a general disconnect between the research business fac-ulty conduct and what is actually needed and practiced in the workplace (Khurana, 2007). Many academic institutions place greater emphasis and rewards on discipline-based re-search at the expense of rere-search relating to application and pedagogy (Hambrick, 2005).

So, where has the cookie cutter approach gotten us? It seems that few individuals outside of business programs are particularly happy with the state of business educa-tion. As a result, business graduates quite often compete against, and frequently lose out in the job market to,

stu-dents with degrees in liberal arts, engineering, and sciences. If our business core were really good, wouldn’t business graduates have a significant competitive advantage over non-business graduates for non-business jobs? Perhaps a different business core would provide students receiving a degree in business with a distinct competitive advantage over stu-dents receiving a nonbusiness degree. But how is it possible to get there? In the following discussion we touch on just a few of the possibilities and we hope to provoke thought and discussion.

There is little question that the subjects included in the business core as it presently exists are relevant. However, employers and other stakeholders are expecting more. The issue therefore involves how best to incorporate more top-ics into the existing core business curriculum. The simplest solutions (and perhaps the least desirable) include the fol-lowing: (a) adding additional relevant courses to the business core thus increasing total credit hours required for a business degree; or (b) substituting additional business core courses for either general education or specialization courses. Both of these options are fraught with budgetary and political danger.

A third option involves rethinking the traditional notion that all business courses must be three credit hours. Consider the present standards. The typical undergraduate business degree requires approximately 120 credit hours consisting of 60 credit hours of general education credits (50%), 21 credit hours in specialization courses (17.5%), and 39 credit hours in the business core (32.5%). Table 6 lists 13 business courses, totaling approximately 39 credit hours, required by the majority of business programs. It is readily apparent from this list that there is no room for additional courses/topics in the business core without cannibalizing general education or specializations (majors).

Now consider a different approach, one involving the re-distribution of credit hours across core topic areas. Such a curriculum could include a limited number of three–credit-hour courses (e.g., accounting and economics, which are frequently transferred from community colleges), with the remaining credit hours distributed in increments of 1.5 credit hours. Why not one– or two–credit-hour courses? First, fac-ulty teaching loads are generally devised in light of two, three, or four courses per semester, each at three credit hours. Insert-ing a one– or two–credit-hour course causes load imbalance. This is particularly problematic in the summer, when faculty pay is often based on the number of credit hours taught. That would leave the rest of the traditional core as 1.5–credit-hour courses. In addition to the thirteen traditional topics, there are many other topical areas to consider (see Table 2 for examples).

Another solution would involve utilizing the strengths and resources of general education programs to provide business students with some of the competencies employers seek in business graduates. In their recently published book, Rethink-ing Undergraduate Business Education: Liberal LearnRethink-ing

THINKING OUTSIDE THE BOX 209

for the Profession, Colby, Ehrlich, Sullivan, and Dolle (2011) made a strong case for business programs formally coordi-nating with liberal education to deliver competencies in such areas as analytical thinking, multiple framing, and reflective thinking to name but a few. Certainly some of the miss-ing topics mentioned earlier could be adequately covered by general education.

Still another approach might involve continuing the use of the traditional three–credit-hour course format but, re-grouping around related topics. For example, the traditional corporate finance course could be combined with financial statement analysis, and financial markets could be combined with Investments into single three–credit-hour courses. Op-erations management and marketing could also be combined into one three–credit-hour course in supply chain manage-ment.

An even more radical approach might involve creating a mosaic design of shorter sequential, related modules perhaps pooling common topics. For example, pricing is a topic com-monly covered in four or more of the traditional business core courses (e.g., accounting, economics, marketing, and operations management). Such topics could be reorganized into single modules thereby reducing redundancy and which could involve clock hours of contact that could be converted into credit hours. Certainly such an approach would be an ad-ministrative challenge with respect to scheduling and faculty workload assignments. However, the flexibility in terms of topic coverage would be tremendous. Regrouping and com-bining topics would also require changes to the pedagogical and structural “silos” typically found in business programs (Campbell, Heriot, & Finney, 2006; Stover, Morris, Pharr, Reyes, & Byers, 1997).

The solutions discussed previously are just a few of many possible alternatives. Some business programs are already experimenting with such unique approaches (cf. Strempek, Husted, & Gray, 2010). However, at this time it would seem that the vast majority of undergraduate business programs in the United States are mired in the past with little indication of significant change in the near future. Students deserve the absolute best education that can be provided and the business academy should continue to strive to ensure that this happens.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

We have identified several seemingly important topics (e.g., integration, ethics, experiential), which did not appear to be included in most business curriculum. However, some of these topics could be sufficiently addressed within courses at some institutions and yet not be discernible from course titles or description. As the saying goes, you can’t judge a book by its cover. Great care was taken to try to place courses in the appropriate category. Some were easy (e.g., accounting, economics) but others were more challenging and required an examination of course title or descriptions. Consequently, some margin for error should be considered.

In addition to the topics reviewed earlier, there are several additional topics that are starting to receive the attention of the business academy. These topics include innovation, en-trepreneurship, sustainability, social responsibility, and criti-cal thinking, to name but a few. While these topics are of im-portance, standalone courses in these areas were rare. Also, the data on which business core credit hours were based comes from a very small subsample. Additional research in this area using a larger sample of programs is needed.

Both Gordon and Howell (1959) and Pierson (1959) expr-essed concerns regarding the role general education courses (other than math) played in business curriculum. We did not address any of these concerns other than to examine math requirements. Additional research is needed in this area.

REFERENCES

Abraham, S. E., & Karns, L. A. (2009). Do business schools value the

competencies that businesses value?Journal of Education for Business,

84, 350–356.

Abraham, S. E., Karns, L. A., Shaw, K., & Mena, M. A. (2001). Managerial

competencies and the managerial performance appraisal process.The

Journal of Management Development,20, 842–852.

Campbell, N., Heriot, K., & Finney, R. (2006). In defense of silos: An

argu-ment against the integrative undergraduate business curriculum.Journal

of Management Education,30, 316–332.

Colby, A., Ehrlich, T., Sullivan, W. M., & Dolle, J. R. (2011).Rethinking undergraduate business education: Liberal learning for the profession. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Gordon, R. A., & Howell, J. E. (1959).Higher education for business. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good

man-agement practices.Academy of Management Learning & Education,4,

75–91.

Hambrick, D. C. (2005). Just how bad are our theories? A response to

Ghoshal.Academy of Management Learning & Education,4, 104–107.

Harper, S. C. (1987). Business education: A view from the top.Business

Forum,12(3), 24–27.

Khurana, R. (2007).From higher aims to hired hands. Princeton, NJ: Prince-ton University Press.

Marascuilo, L. A. (1966). Large-sample multiple comparisons.

Psychologi-cal Bulletin,65, 280–290.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2010).Digest of

educa-tion statistics. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest

Pierson, F. C. (1959).The education of American businessmen. New York,

NY: McGraw-Hill.

Porter, L. W., & McKibbin, L. E. (1988).Management education and devel-opment: Drift or thrust into the 21stcentury?New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Stover, D., Morris, J., Pharr, S., Reyes, M., & Byers, C. (1997). Breaking

down the silos: Attaining an integrated business common core.American

Business Review,15(2), 1–11.

Strempek, R., Husted, S., & Gray, P. (2010). Integrated business core

cur-ricula (undergraduate): What have we learned in over 20 years?Academy

of Educational Leadership Journal,14, 19–34.

Tanyel, F., Mitchell, M. A., & McAlum, H. G. (1999). The skill set for success of new business school graduates: Do prospective employers and university faculty agree?Journal of Education for Business,75, 33–37. Van Fleet, D. D., & Wren, D. A. (2005). Teaching history in business schools:

1982–2003.Academy of Management Learning & Education,4, 44–56.

Wickramasinghe, V., & De Zoyza, N. (2009). A comparative analysis of managerial competency needs across areas of functional specialization. Journal of Management Development,28, 344–360.