www.elsevier.com / locate / econbase

Fairness as a constraint on trust in reciprocity: earned property

rights in a reciprocal exchange experiment

a b ,

*

´

Rene Fahr , Bernd Irlenbusch

a

¨

Bonn Graduate School of Economics, Universitat Bonn, Adenauerallee 24 –26, D-53113 Bonn, Germany b

¨ ¨

Laboratorium f ur Experimentelle Wirtschaftsforschung, Universitat Bonn, Adenauerallee 24 –26, D-53113 Bonn,

Germany

Received 22 February 1999; accepted 23 September 1999

Abstract

We investigate the concept of mindreading in a trust–reciprocity experiment. Our results show that the Trustees send back more, the stronger the Trustors’ property rights are. But instead of strategically relying on this reciprocal behavior, Trustors tend to unilaterally implement a fair outcome. 2000 Elsevier Science S.A. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Mindreading; Fairness; Trust; Reciprocity; Property rights; Real effort; Experiments

JEL classification: C70; C78; C91; D63

1. Introduction

1

¨

Several experimental studies show that in ultimatum games (Guth et al., 1982) the behavior of the

2

first mover changes when participants earn different property rights (Hoffman et al., 1994, 1996; Ruffle, 1998). If the Proposer holds property rights, she offers substantially lower amounts to the Responder compared to the situation with no property rights. On the other hand, if the Responder holds property rights, the proposal is much more generous than in a ‘no property rights’ setting. The

*Corresponding author. Tel.: 149-228-73-9196; fax:149-228-73-9193.

E-mail address: [email protected] (B. Irlenbusch) 1

In an ultimatum game the first mover, i.e., the Proposer, has to offer some proportion of a fixed amount of money. The second mover, i.e., the Responder, either accepts or rejects the offer. If the offer is accepted the money is allocated accordingly. If the Responder rejects nobody receives anything.

2

In accordance with the cited literature we use the term ‘property rights’ in the sense of an entitlement obtained by performing a (working) task.

fact that the rejection rates remain virtually the same in all settings (see Hoffman et al., 1994) is

3

particularly interesting. Smith (1998) explains these observations with the concept of mindreading . According to this concept there is a mental process which enables human beings to infer the reactions of others from the consciousness of their own behavior: ‘‘[Mindreading] enables me to see not only the value to me of possessing certain rights to act [i.e., property rights], but also to know intuitively the value of such rights for others’’ (Smith, 1998, p. 8). By applying the concept of mindreading to the ultimatum game, Smith claims that the Proposer as a property rights holder offers less because, due to mindreading, she expects the Responder to reward her property rights. Similarly, if the Responder holds the property rights, offers are supposed to be high because the Proposer may fear that the offer will be rejected otherwise. We doubt whether Smith’s concept of mindreading really characterizes the main driving force behind the observed behavior. Instead, we argue that, concerning property rights effects, unilateral fairness considerations (compare Kahneman et al., 1986) are much more important. As a test this paper investigates whether in a slightly different game — the trust–reciprocity game — the first mover really strategically acts according to the expected behavior of the second mover, as mindreading would predict.

In our one-shot trust–reciprocity game (see Fehr et al., 1993, 1997; Berg et al., 1995) the first mover (Trustor) is endowed with DM 10 to make an investment x while keeping the rest for herself (0#x#10). In a second stage the second mover (Trustee) receives a multiple (3x) of the investment and may return an amount y to the Trustor (0#y#3x). Trivially, the game is reduced to one stage if the Trustor passes nothing to the Trustee. In fact, x50, y50; x is the subgame perfect solution of the trust game, given the players are mere money-maximizers. In contrast to other reciprocity studies, we conducted three treatments along the property rights dimension, i.e., previous to the trust– reciprocity game various participants earn property rights by performing a real effort working task. In

4

treatment WL only the Trustor holds a property right, whereas in treatment LW a property right is obtained by the Trustee, but not by the Trustor. In a control treatment WW none of the two players is entitled to more than the other one. In the following we speak of subjects as holding a stronger property right, if they worked more than the participant they are paired with.

2. Experimental design and procedure: entitlement in a trust game

¨

The experiment was conducted at the Laboratorium fur Experimentelle Wirtschaftsforschung at the ¨

Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitat Bonn. Participants were students of different disciplines, but most of them were law or economics students.

Depending on the treatment, some participants (the workers) had to perform a real effort working

5

task, i.e., they were asked to crack walnuts. In order to succeed they had to come up with at least

3

This concept is taken from the literature on evolutionary psychology (see Baron-Cohen, 1995). 4

WL (LW ) indicates that the Trustor Worked (had Leisure time) while the Trustee had Leisure (Worked) time. WW

indicates that both participants Worked. 5

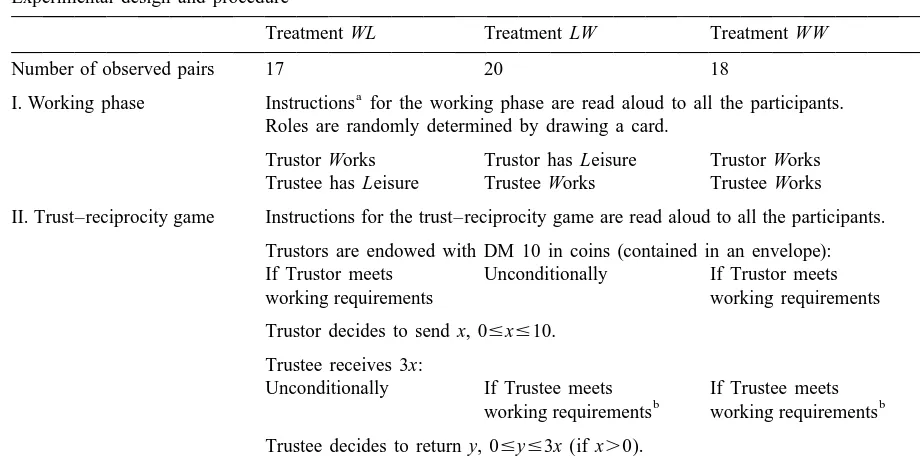

Table 1

Experimental design and procedure

Treatment WL Treatment LW Treatment WW

Number of observed pairs 17 20 18

a

I. Working phase Instructions for the working phase are read aloud to all the participants. Roles are randomly determined by drawing a card.

Trustor Works Trustor has Leisure Trustor Works Trustee has Leisure Trustee Works Trustee Works

II. Trust–reciprocity game Instructions for the trust–reciprocity game are read aloud to all the participants.

Trustors are endowed with DM 10 in coins (contained in an envelope): If Trustor meets Unconditionally If Trustor meets working requirements working requirements

Trustor decides to send x, 0#x#10.

Trustee receives 3x:

Unconditionally If Trustee meets If Trustee meets

b b

working requirements working requirements

Trustee decides to return y, 0#y#3x (if x.0).

III. Payment All participants are paid an additional DM 5 show-up fee.

a

The instruction sheets and the raw data can be obtained from the authors on request. b

At the time when the Trustor made her investment decision she did not know whether the Trustee had succeeded in his working task. This would have created a situation of incomplete information for the Trustor in which she would have to estimate the success probability of the Trustee. Because we wanted the game to be one of perfect information, we set up the rule that a Trustor would get back her original investment if she was matched with a Trustee who did not accomplish his work.

150 g of walnut kernels in half an hour. The subjects who did not have to work were at leisure to do what they wanted. For example, they could leave the laboratory to drink coffee, read newspapers, study their lecture notes, play cards, or watch the workers. The design and procedure of the experiment is depicted in Table 1. The trust–reciprocity game was conducted under anonymous conditions, i.e., participants did not know with whom they were matched.

3. Research hypotheses

The main aim of this study is to analyze whether property rights alter the behavior in the trust–reciprocity game and if so, whether we can predict this influence with the mindreading concept. Testing for the equity principle (Selten, 1978) in the trust–reciprocity game was the second objective we had in mind when designing the present experiment.

3.1. Hypothesis implied by mindreading versus that emerging from fairness

6

experimental results in Hoffman et al. (1994), on the dictator game. They find that the Allocator gives less if he holds stronger property rights. If the Trustee in our game has received money, he faces a situation which is strategically equivalent to that of the Allocator in the dictator game. Thus, let us first consider the reactions of the Trustee. We use Freturn(?) to denote the cumulative distribution

7

function of returns on an investment of DM 10 for each of the three treatments:

Hreturn: the stronger the property rights of the Trustors, the higher the returns (on investment of

DM 10): Freturn(WL ),Freturn(WW ),Freturn(LW )

According to the concept of mindreading the Trustor should anticipate the Trustee’s behavior as outlined in Hreturn. Thus, if the Trustor tries to strategically exploit the knowledge obtained from mindreading, it would be profitable for her to invest more, the more she is entitled. This would enable the Trustee to reciprocate, i.e., to send back more money. With Finvest(?) denoting the cumulative distribution function of investments, we have the mindreading hypothesis:

mind

Hinvest: The stronger the property rights of the Trustors, the higher the investments: Finvest(WL )

,Finvest(WW ),Finvest(LW )

Alternatively, Trustors could unilaterally implement an outcome that can be considered to be fair, i.e., the one who has higher property rights should earn more. The latter means that Trustors only place confidence in the Trustees with a high investment if this investment does not conflict with their own fairness considerations. In this case, higher investments should be observed if the Trustees are the ones who deserve the higher payoffs by holding stronger property rights. This gives us the hypothesis emerging from fairness considerations:

fair

Hinvest: the stronger the property rights of the Trustees, the higher the investments: Finvest(LW )

,Finvest(WW ),Finvest(WL )

3.2. Hypotheses implied by the equity principle

One important fairness norm is the equity principle: an allocation is perceived as fair if the ratio of the outcome to the input is equal to the outcome / input ratio of others. This is formulated in a qualitatively similar way by Burrows and Loomes (1994, p. 203): ‘‘differentials in payoffs are deserved, and are, therefore, fair if they correlate positively with the amount of effort involved in obtaining them.’’

According to the equity principle, the difference in entitlement should make a difference in payoffs, namely Trustors deserve the highest (lowest) payoff in treatment WL (LW ), in which they have a strong (weak) property right (vice versa for the Trustee). Because in treatment WW the property rights

6

In the dictator game one player (the Allocator) receives a sum of money from the experimenter which he can unilaterally distribute between another person (the Recipient) and himself.

7

of the two players are equal, we expect the payoffs of this treatment to lie in between. Let FP(?)(?) be the cumulative distribution function of payoffs for each of the three treatments. Thus, our hypotheses about the payoffs are:

HP( Trustors): the stronger the property rights of the Trustors, the higher their payoffs:

FP( Trustors)(WL ),FP( Trustors)(WW ),FP( Trustors)(LW )

HP( Trustees): the stronger the property rights of the Trustees, the higher their payoffs:

FP( Trustees)(LW ),FP( Trustees)(WW ),FP( Trustees)(WL )

We will test all our hypotheses against the null hypothesis that the distributions are identical.

4. Results and conclusion

By applying the nonparametric Jonckheere test for ordered alternatives, we find the following results.

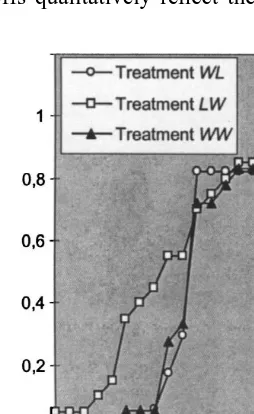

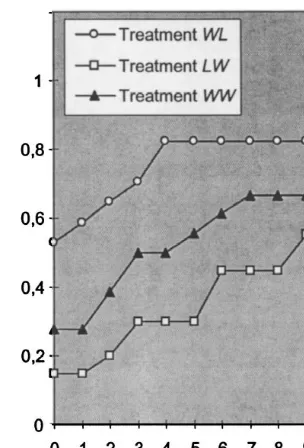

We can weakly significantly reject the null hypothesis that the distributions of payoffs are equal in all treatments in favor of HP( Trustors) (P50.0526, see Fig. 1). Analogously, we reject the null hypothesis in favor of HP( Trustees), which is highly significant (P50.0001, see Fig. 2). Thus, our results underline the robustness of property rights effects found in a number of experimental settings. Final payoffs of both the Trustors and the Trustees tend to increase if they hold stronger property rights. It is amazing that even in such an extreme asymmetric bargaining situation as the reciprocal exchange, the observed total payoffs qualitatively reflect the equity principle.

Fig. 2. Cumulative distributions of Trustees’ payoffs.

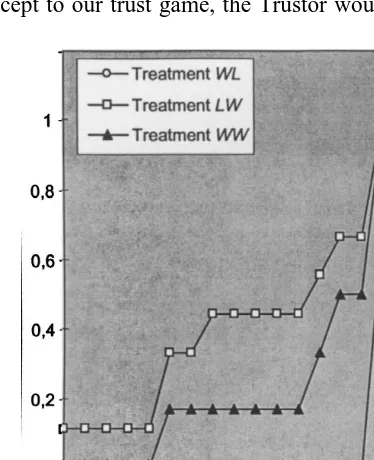

We can significantly reject the null hypothesis that the distributions of the considered returns are the same, in favor of our hypothesis Hreturn (P50.0179, see Fig. 3). This means that Trustees return significantly more, the stronger the property rights of the Trustors are. According to the concept of mindreading proposed by Smith (1998), bargainers are able to foresee the tendency of the reactions of others. If we apply this concept to our trust game, the Trustor would expect the observed behavior of

Fig. 4. Cumulative distributions of investments.

the Trustee. Thus, a Trustor should invest more if she holds stronger property rights and thereby strategically exploit the expected reciprocal behavior of the Trustee. However, we do not observe such

mind

behavior and thus cannot significantly reject the null hypothesis in favor of the hypothesis Hinvest.

fair

Instead, the null hypothesis is rejected very clearly in favor of our hypothesis Hinvest (P50.0026, see Fig. 4). This is clear evidence against the implications of mindreading. Trustors unilaterally implement a fair outcome by investing more, the more the Trustee is entitled. Unilateral fairness considerations seem to be sufficiently strong to abandon strategic opportunities, which would arise from trust in the norm of reciprocity. Our result — that the Trustor tends to invest less, the more the Trustee is expected to reciprocate — rejects the applicability of the concept of mindreading in a trust–reciprocity game and thereby raises severe doubts as to whether the concept really explains what is observed in the ultimatum game.

Acknowledgements

¨ ¨

The authors thank the anonymous referee, Klaus Abbink, Simon Gachter, Werner Guth, Radosveta ¨

Ivanova-Stenzel, Manfred Konigstein, Bettina Kuon, Abdolkarim Sadrieh, Wendelin Schnedler and Reinhard Selten and the participants of the GEW-Workshop 1998 for helpful comments. Financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through Sonderforschungsbereich 303 at the

¨

References

Baron-Cohen, S., 1995. In: Mindblindness. An Essay on Autism and Theory of Mind, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., McCabe, K., 1995. Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games and Economic Behavior 10, 121–142. Burrows, P., Loomes, G., 1994. The impact of fairness on bargaining behaviour. Empirical Economics 19, 201–221. Fehr, E., Kirchsteiger, G., Riedl, A., 1993. Does fairness prevent market clearing? An experimental investigation. Quarterly

Journal of Economics 108 (2), 437–460. ¨

Fehr, E., Gachter, S., Kirchsteiger, G., 1997. Reciprocity as a contract enforcement device: experimental evidence. Econometrica 65 (4), 833–860.

¨

Guth, W., Schmittberger, R., Schwarze, B., 1982. An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 3, 367–388.

Hoffman, E., McCabe, K., Shachat, K., Smith, V.L., 1994. Preferences, property rights, and anonymity in bargaining games. Games and Economic Behavior 7, 346–380.

Hoffman, E., McCabe, K., Smith, V.L., 1996. On expectations and the monetary stakes in ultimatum games. International Journal of Game Theory 25, 289–301.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J.L., Thaler, R., 1986. Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: entitlements in the market. The American Economic Review 76 (4), 728–741.

Ruffle, B.J., 1998. More is better, but fair is fair: tipping in dictator and ultimatum games. Games and Economic Behavior 23, 247–265.

Selten, R., 1978. The equity principle in economic behavior. In: Gottinger, H.W., Leinfellner, W. (Eds.), Decision Theory and Social Ethics, Issues in Social Choice, D. Reidel, Dordrecht, pp. 289–301.