Ž .

Animal Reproduction Science 59 2000 213–228

www.elsevier.comrlocateranireprosci

Sperm transport in the female reproductive tract of

the brushtail possum, Trichosurus

Õ

ulpecula,

following superovulation and artificial insemination

M.K. Jungnickel

a, F.C. Molinia

b,), A.J. Harman

a, J.C. Rodger

c aCooperatiÕe Research Centre for ConserÕation and Management of Marsupials, Department of Biological

Sciences, UniÕersity of Newcastle, Newcastle, New South Wales 2308, Australia

b

CooperatiÕe Research Centre for ConserÕation and Management of Marsupials, Landcare Research, PO Box

69, Lincoln, Christchurch 8152, New Zealand c

CooperatiÕe Research Centre for ConserÕation and Management of Marsupials, School of Biological

Sciences, Macquarie UniÕersity, Sydney,New South Wales 2109, Australia

Received 3 March 1999; received in revised form 23 December 1999; accepted 20 January 2000

Abstract

This study investigated sperm transport following superovulation and artificial insemination

ŽAI in the common brushtail possum, Trichosurus. Õulpecula. Females were superovulated by

Ž .

treatment with 15 IU pregnant mare serum gonadotrophin PMSG then 4 mg luteinizing hormone

ŽLH 78 h later. Inseminations were performed 27 h after LH 4 million motile spermatozoar. Ž

. Ž .

uterus . At 1.5, 3, 6, 9 and 12 h after AI ns5 per group , females were euthanised and

reproductive tracts removed for examination and flushed for sperm. No ovulations had occurred by 1.5 h, but 20% of animals had ovulated by 3 or 6 h, and 80% by 9 or 12 h. The mean numbers

of spermatozoa recovered ranged from 249 to 275=103 in the uterus; 16–51=103 in the

isthmus; 8–11=103in the middle segment; and 6–16=103in the ampulla at 1.5, 3 and 6 h after

Ž .

AI. Sperm numbers in all regions decreased at later times P-0.05 except the isthmus, where

3 Ž

100=10 sperm were recovered by 12 h. Highly motile thumbtack sperm a putative indicator of

. Ž . Ž .

capacitation in marsupials , were recovered from the isthmus 20% , middle segment 50% and

Ž .

ampulla 90% at all sampling times, but not from the uterus. The epithelium of the oviduct segments contained mucus-secreting and ciliated cells and peak secretory activity was observed in the ampulla at 6 h. At 3, 6 and 12 h, many spermatozoa were found in epithelial folds within the isthmus. The present study has provided basic information on sperm transport and storage events

within the female reproductive tract of T. Õulpecula following superovulation and AI. It is

)Corresponding author. Tel.:q64-3-325-6701 extension: 3746; fax:q64-3-325-2418.

Ž .

E-mail address: [email protected] F.C. Molinia .

0378-4320r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Ž .

concluded that this model may be useful to better understand pre-fertilization sperm maturation

events in the possum, which could facilitate the development of IVF technology.q2000 Elsevier

Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Possum; Sperm transport; Superovulation; Artificial insemination

1. Introduction

Timed observations on the fate of spermatozoa after their deposition in the female Ž

tract have been made in only five marsupial species, Macropus eugenii Tyndale-Biscoe

. Ž

and Rodger, 1978 , Antechinus stuartii Selwood, 1982; Taggart and Temple-Smith,

. Ž . Ž

1991 , Sminthopsis crassicaudata Breed et al., 1989 , Didelphis Õirginiana Rodger

. Ž

and Bedford, 1982a,b; Bedford et al., 1984 and A. agilis Shimmin et al., 1999; .

Taggart et al., 1999 . Semen is deposited in the upper part of the urogenital sinus in

Ž .

marsupials and progresses up the lateral vaginae to the twin cervices Rodger, 1991 . From the cervices, sperm move through the utero–tubal junction into the lower isthmus region of the oviduct. The utero–tubal junction forms a barrier to sperm migration up

Ž .

the female tract in eutherian mammals Hunter, 1988 . In marsupials, however, this region appears to present little, if any, barrier to sperm progression into the isthmus of

Ž . Ž .

the oviduct Taggart, 1994 . Both dasyurids Taggart and Temple-Smith, 1991 and

Ž .

didelphids Bedford et al., 1984 transport sperm efficiently with )1 in 20 ejaculated spermatozoa reaching the isthmus of the oviduct. In these species, sperm are stored in

Ž .

specialised isthmic crypts for up to 2 weeks located near the utero–tubal junction Žreviewed by Taggart, 1994 . Similar isthmic crypts have not been previously reported.

Ž . Ž

in the brushtail possum Arnold and Shorey, 1985 or macropodid marsupials Tyndale-.

Biscoe and Rodger, 1978 .

In addition to its role in sperm storage, the isthmus is thought to have an important

Ž .

role in the capacitation of spermatozoa in eutherian mammals Yanagimachi, 1994 . Capacitation is an obligatory maturational event which sperm must undergo in the female tract before achieving full fertilizing potential. It generally occurs in the lower segment of the oviduct, and is currently thought to involve the removal of surface

Ž

coating materials and an increased permeability to metal ions Sidhu and Guraya, 1989; .

Yanagimachi, 1994 .

Although this is yet to be definitively established, it appears that marsupial spermato-zoa also undergo a period of capacitation, but exactly what regions of the female

Ž .

reproductive tract are involved in this process is unknown Mate and Rodger, 1996 . Further, the mechanisms involved appear quite different, not only from eutherians but also between Australian and American marsupials. In American species, separation of

Ž paired spermatozoa is highly correlated with the acquisition of fertilizing ability Moore

.

and Taggart, 1993 , while in several Australian marsupials, reorientation of the head

Ž .

region of highly motile spermatozoa to a thumbtack T-shape configuration is thought

Ž .

( )

M.K. Jungnickel et al.rAnimal Reproduction Science 59 2000 213–228 215

possum natural mating behaviour has led to the development of a laparoscopic artificial

Ž . Ž .

insemination AI procedure Molinia et al., 1998 . As possums are monovular, it has been necessary to concurrently develop superovulation and AI protocols to maximise potential numbers of ovulated eggs available for fertilization in vivo. Further, hormone manipulation permits control of the timing of insemination relative to ovulation, and fertilization. Using both AI and superovulation with the exogenous hormones pregnant

Ž . Ž .

mare serum gonadotrophin PMSGrLH, fertilized eggs or embryos 1–2 per possum

Ž .

are consistently recovered Molinia et al., 1998 . Accordingly, the combination of superovulation and AI provides a model system to investigate sperm transport and pre-fertilization events in the possum.

The main aim of the current study was to investigate sperm transport in vivo following intrauterine AI of PMSGrLH superovulated possums. Specific objectives were to determine the distribution of spermatozoa through the female reproductive tract in relation to ovulation, to characterise the epithelial lining of the oviduct with particular emphasis on the presence of any sperm storage regions within the lower isthmus, and to examine the morphology and motility of spermatozoa within each of the isthmus, middle and ampulla oviduct segments.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Ž .

Brushtail possums TrichosurusÕulpecula were captured in box traps and transferred to the Landcare Research Animal Facility at Lincoln, New Zealand. The animals were weighed and separate sexes were housed in individual cages. The animals were maintained on a diet of cereal pellets supplemented with fruit and vegetables and their food and water requirements were attended to daily. Experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research and the University of Newcastle Animal Care and Ethics Committee.

2.2. SuperoÕulation

A PMSGrLH hormone protocol was used to superovulate all female possums prior

Ž .

to laparoscopic AI. PMSG Folligon; Intervet, Oss, The Netherlands was administered as a single 15 IU i.m. injection followed by a single i.m. injection of 4 mg LH ŽLutropin-V; Vetrepharm, Essendon, Victoria, Australia 78 h later Glazier and Molinia,. Ž

.

1998 . LH was provided as a generous gift by Vetrepharm, Australia.

2.3. Semen collection and processing

Ž y1. Ž .

Male possums were anaesthetised by CO2rO2 2 lr1 l min Jolly et al., 1995 Ž and then killed with a single intra-cardiac injection of sodium pentobarbitone

Pento-. y1

Ž .

sharp blade and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline PBS to release spermatozoa. Spermatozoa were assessed for motility by phase contrast microscopy and for

concentra-Ž .

tion using a haemocytometer Rodger et al., 1991 . Semen samples were diluted with PBS to a concentration of 1=107 motile spermatozoa and stored at 48C for up to 2 h prior to insemination.

2.4. Laparoscopic intrauterine AI

Females were inseminated at 27 h after LH directly into both uteri using a

Ž .

laparoscopic procedure as previously described Molinia et al., 1998 . Each uterus Ž

received a single dose of spermatozoa 0.4 ml containing approximately 4 million motile .

spermatozoa . The animals were allowed to recover in a quiet corner before examination of the reproductive tracts.

2.5. Examination and processing of reproductiÕe tracts

Ž .

At 1.5, 3, 6, 9 and 12 h after AI ns5 per group , females were euthanised by barbiturate overdose as detailed above for male possums. Reproductive tracts were removed and the ovaries separated for assessment of numbers of recent ovulation sites

Ž .

and remaining un-ovulated follicles )2 mm . Vaginal smears were taken and the slides examined for the presence of spermatozoa using Hoffman modulation contrast

mi-Ž .

croscopy Zeiss Axiovert 35 microscope .

Each ovaryroviductruterus complex was separated from the vagina at the cervices.

Ž .

Each oviduct was clamped Vascu-Statt; Scanlan, Victoria, Australia by visual

assess-Ž .

ment into three approximately equal segments; the isthmus nearest the uterus , middle

Ž .

segment and ampulla nearest the ovary . As detailed below, the left side of the tract was flushed and the right side processed for either histological staining or electron mi-croscopy.

2.6. Flushing and estimation of sperm numbers

The left uterus and oviduct regions were excised from the remainder of the tract and

Ž . Ž . Ž

flushed with either 1.0 ml uterus or 0.6 ml oviduct segments of heparinised 12.5 IU y1.

ml PBS. After flushing, tissue was fixed in Bouin’s fluid, processed for routine light

Ž .

microscopy as detailed below and examined for the presence of spermatozoa to ensure that the procedure had been successful.

The flushes were first examined under a phase-contrast microscope to assess motility and headrtail orientation of spermatozoa. To estimate sperm numbers, a constant

Ž . Ž

volume of the flush 0.5 ml was centrifuged at 150=g for 5 min. The supernatant 0.4

. Ž .

( )

M.K. Jungnickel et al.rAnimal Reproduction Science 59 2000 213–228 217

2.7. Histological processing

For half of the possums examined, the right side of the tract was fixed whole in Bouin’s solution. Segments were immersed in Bouin’s fixative for 48 h, then washed in several changes of 70% ethanol and stored in 70% ethanol. Wax blocks were prepared

Ž .

and 7-mm sections were cut and stained with Harris’ haematoxylin and eosin HNE , or with one of the following mucopolysaccharide histochemical methods: 1% alcian blue,

Ž . Ž .

pH 2.5 or periodic acid-Schiff PAS Pearse, 1968 .

2.8. Electron microscopy

For the remaining possums, the right side of the tract was fixed whole in Karnovsky’s

Ž .

solution Karnovsky, 1965 at pH 7.6 overnight at 48C before storage in 0.1 M

Ž .

phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 at room temperature Mate et al., 1992 . Post-fixation was in

Ž .

1% wrv OsO4 in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for 1 h at 48C. This was followed by washing in distilled water, dehydration and embedding in Spurr’s resin. Ultrathin sections were placed on nickel grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined on a Joel CX-100 electron microscope.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Ovarian assessments are presented as mean values with range intervals. The numbers of spermatozoa recovered from flushes of the tract are presented as means"standard

Ž .

error of the means S.E.M. . Comparison of treatment means was examined non-para-metrically using a Kruskal–Wallis one way ANOVA on ranks. Dunns’ method was used for pairwise comparison to determine which treatment groups were different.

3. Results

Ž

Histological processing revealed that the uterus and oviduct segments isthmus, .

middle segment and ampulla in T.Õulpecula were structurally distinct. Uterine sections characteristically consisted of a series of small glands lined by tall columnar epithelial cells with small basal nuclei. All oviduct segments were lined with pseudo-stratified

Ž .

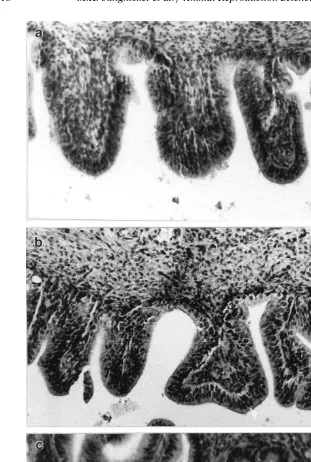

columnar epithelial cells Fig. 1 . The epithelium lining the isthmus region nearest the uterus consisted of highly-folded villi-type projections. Invaginations of this epithelium or ‘folds’ were also abundant within this region. The middle oviduct region was characterised by a simpler less folded epithelial lining. The epithelium found within the ampulla oviduct segment was the most simple in appearance. There were no deep epithelial folds in this region.

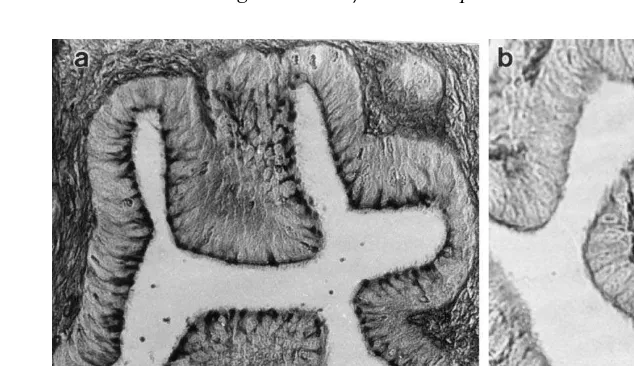

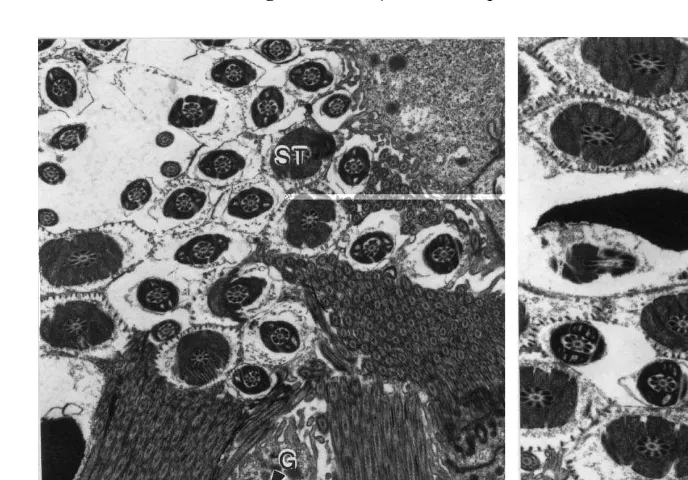

The columnar epithelium lining both the oviduct lumen and the epithelial fold regions

Ž .

contained ciliated and mucus-secreting cells Fig. 2 , and TEM showed that these had numerous electron-dense granules in their apical cytoplasm, together with many

mito-Ž .

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Fig. 1. Longitudinal section LS through the ampulla a , middle segment b and isthmus segment c of the

Ž .

possum oviduct taken at 6 h after AI. Spermatozoa arrowhead ; E, epithelial fold.

( )

M.K. Jungnickel et al.rAnimal Reproduction Science 59 2000 213–228 219

Ž . Ž .

Fig. 2. a LS through the ampulla region of the possum oviduct 6 h after AI 33 h after LH showing

Ž .

secretion on the apical epithelial surface stained strongly with PAS. b LS through the ampulla at 1.5 h after

Ž .

AI 28.5 h after LH showing weak PAS staining of the apical epithelial surface.

Ž .

tails Figs. 3 and 4 . Appropriate sections through the sperm head also showed the

Ž .

presence of an intact acrosome Fig. 4 .

3.1. 1.5 h after AI

The ovarian response to PMSGrLH superovulation and AI is presented in Table 1. At 1.5 h after AI none of the five animals had ovulated, but an average of 10–11

Ž . Ž .

Ž . Ž .

Fig. 4. TEM of an epithelial fold, showing ciliated C and mucus-secreting MU epithelial cells. Spherical

Ž . Ž .

apical granules G are apparent within secretory cells. Sperm tails ST are aligned parallel to the lumen,

Ž .

while sperm heads SH are randomly-oriented. Appropriate sections through the sperm head show an intact

Ž .

acrosome A . c, Cilia.

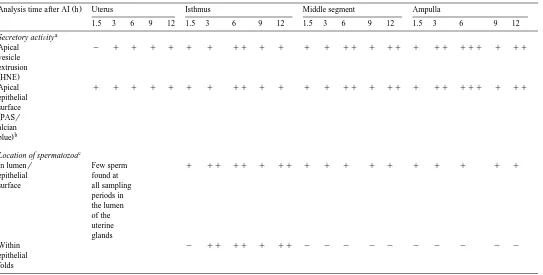

follicles )2 mm per female were observed. Secretory activity was minimal in all regions of the genital tract at 1.5 h after AI, as indicated by low apical vesicle extrusion from HNE-stained secretory cells and the weak staining of epithelial surfaces by PAS

Ž .

and alcian blue Table 2 . The histological location of spermatozoa from unflushed segments of the reproductive tract is presented in Table 2. At 1.5 h after AI, spermato-zoa were found in both the lumen and on the epithelial surfaces of all oviduct regions with their heads opposed or in close proximity to the apical cells. No spermatozoa were

Table 1

The ovarian response of the brushtail possum following PMSGrLH superovulation and intrauterine artificial insemination

a

Ž . Ž .

Time of analysis h Proportion ovulating Mean number range per female

After LH After AI Ovulation sites Follicles remaining)2 mm

Ž .

28.5 1.5 0r5 0 10.6 2–16

Ž .

30.0 3.0 1r5 16 from one female 9.8 1–14

Ž .

33.0 6.0 1r5 3 from one female 10.4 3–22

Ž . Ž .

36.0 9.0 4r5 4.4 0–12 4.8 0–14

Ž . Ž .

39.0 12.0 4r5 5.4 0–13 7.6 0–13

a

()

The location of spermatozoa and secretory activity within the reproductive tract of the brushtail possum following PMSGrLH superovulation and intrauterine artificial insemination

Ž .

Analysis time after AI h Uterus Isthmus Middle segment Ampulla

1.5 3 6 9 12 1.5 3 6 9 12 1.5 3 6 9 12 1.5 3 6 9 12

Secretory activity: y absent, q weak, qq moderate, qqq strong. b

No difference in staining pattern between PAS and alcian blue.

c Ž . Ž . Ž .

found within the epithelial folds. Within the uterus, sperm were located in the lumen of the uterine glands.

3 Ž .

Around 250=10 spermatozoa were flushed from the right uterus Table 3 . None of these displayed thumbtack head orientation. Approximately 16=103 spermatozoa were recovered from the isthmus, whereas 8=103 and 6=103 spermatozoa were flushed

from the middle and ampulla, respectively. Thumbtack spermatozoa with a progressive

Ž .

motility rating of 4–5 on a 0–5 scale, Rodger et al., 1991 were recovered from the oviduct, with a progressive increase in the proportion of these spermatozoa recovered in

Ž . Ž .

moving from the isthmus 20% to the middle 50% and finally to the ampulla Ž)90% . The relative proportion of thumbtack spermatozoa distributed within the. possum reproductive tract was similar at all sampling times after AI.

3.2. 3.0 h after AI

By 3 h after AI, one animal had ovulated in response to the PMSGrLH stimulation,

Ž .

but there were still around 10 follicles )2 mm remaining per female Table 1 . HNE, alcian blue and PAS staining indicated that secretory activity was greater at this

Ž .

sampling period than at 1.5 h after AI Table 2 . Further, there was a progressive increase in the amount of secretion from the uterus to the ampulla. Within all regions of the oviduct, spermatozoa were found in both the lumen and on the apical epithelial

Ž .

surface. Spermatozoa in the isthmus were also located within epithelial folds Table 2 . Sperm orientation within these regions was similar to that observed within the oviduct lumen at 1.5 h. The numbers of spermatozoa recovered from the uterus and oviduct

Ž .

regions at 3.0 h, were similar to the numbers recovered at 1.5 h after AI Table 3 .

3.3. 6.0 h after AI

Even at 6 h after AI, only one out of five animals had ovulated and the ovarian

Ž .

response was similar to that reported at 3.0 h Table 1 . Secretory activity, was greater at

Ž .

this sampling period than at 1.5 or 3.0 h Table 2 , and the amount of vesicle extrusion

Ž .

progressively increased from the uterus to the ampulla Fig. 2 . Spermatozoa were found in the lumen of the uterine glands. For the isthmus, middle and ampulla segments of the

Table 3

Ž 3. Ž .

Total numbers of spermatozoa =10 recovered from the female reproductive tract mean"S.E.M. after PMSGrLH superovulation and intrauterine artificial insemination

Ž . Ž .

Within columns, means "S.E.M. with different superscripts are significantly different P-0.05 .

Ž .

"Time of analysis h Uterus Oviduct

After AI After LH Isthmus Middle Ampulla

( )

M.K. Jungnickel et al.rAnimal Reproduction Science 59 2000 213–228 223

oviduct, spermatozoa were located in both the lumen and at the apical surface of the epithelial cell lining. In the isthmus, spermatozoa were also observed within epithelial

Ž .

folds Table 2 .

Ž .

Once again, similar numbers of spermatozoa were flushed from the uterus Table 3 . The highest numbers of spermatozoa were recovered from all the oviduct segments compared with the 1.5- and 3.0-h sampling periods, but this was only significant for the

3 Ž .

isthmus where approximately 50=10 spermatozoa were recovered P-0.05 .

3.4. 9.0 h after AI

By 9 h after AI, four of the five animals had ovulated, which resulted in a concomitant reduction in the mean number of remaining follicles )2 mm to around 5

Ž .

mm per female Table 1 . Secretory activity was lower at the 9-h sampling period than

Ž .

at 6 h, and there was no increase in secretion from the uterus to the ampulla Table 2 . Within all oviduct segments, spermatozoa were found in both the lumen and associated with the epithelial surfaces. Only few spermatozoa were found within the epithelial folds at 9 h after AI. As in previous sampling periods, uterine spermatozoa were located within glandular regions.

Much lower numbers of spermatozoa were flushed from the uterus at this time than at

Ž .

previous sampling periods P-0.05 . A similar drop in sperm numbers occurred within

Ž .

all regions of the oviduct at 9 h relative to the 6-h sampling period P-0.05, Table 3 .

3.5. 12.0 h after AI

The ovarian response at 12 h after AI was similar to the response at 9 h, with an

Ž .

average of over five ovulation sites observed per female Table 1 . Secretory activity

Ž .

was greater at this sampling period than at 9 h after AI Table 2 and the pattern of secretion again showed a progressive increase from the uterus to the ampulla. Uterine spermatozoa were located in glands at this sampling period. Within the ampulla, middle and isthmus regions of the oviduct, spermatozoa were found in the lumen and associated with the apical surface of epithelial cells. Isthmic spermatozoa were also seen in the

Ž .

epithelial fold regions Table 2 .

Twice as many spermatozoa were recovered from the uterus and a significantly

Ž .

greater number of spermatozoa P-0.05 were recovered from the isthmus at 12 h

Ž 3.

compared with 9 h. Low numbers of spermatozoa 1–2=10 were flushed from the

Ž .

middle and ampulla regions as for the 9-h sampling period Table 3 .

4. Discussion

The PMSGrLH treatment used in this study resulted in ovarian stimulation of

Ž .

possums as previously reported Glazier and Molinia, 1998 . The results are consistent

Ž .

Ž . Ž .

after AI 33 h after LH , but by 9 and 12 h 36 and 39 h after LH , 40–50% of these had ovulated. This translated to around five ovulation sites per female, which is consistent

Ž

with that previously reported for possums following laparoscopic AI Molinia et al., .

1998 .

In the present study, sperm transport in the possum was examined following superovulation and AI into the uterus. Not surprisingly, the numbers of sperm recovered were 5–15 times those flushed from the oviducts and uterus of naturally mated tammar

Ž . Ž .

wallabies Tyndale-Biscoe and Rodger, 1978 . However, Smith et al. 1987 reported that whereas numbers of sperm recovered from oviducts of artificially inseminated and naturally mated golden hamsters were different, the pattern of sperm distribution was the same. Progression of sperm to the site of fertilization in eutherian species is stimulated

Ž .

by the ovulating follicle s , either via direct intraluminal effects of ovulation products, andror through follicular hormones delivered systematically or concentrated

ipsilater-Ž .

ally through counter-current exchange or simple diffusion Hunter, 1995 . Increasing synthesis of progesterone rather than of oestradiol, is a principal feature, arising as a sequel to the pre-ovulatory gonadotrophin surge and loss of follicular aromatase activity, and a principal role for progesterone interacting with the wall of the oviduct in

Ž .

facilitating sperm transport has been demonstrated Hunter, 1972 . A recent study has demonstrated that levels of oestradiol and progesterone in the peripheral plasma, ovarian veins and oviduct fluid do not differ significantly between PMSGrLH superovulated

Ž and naturally cycling possums around the onset of ovulation and fertilization M.K.

.

Jungnickel and T.P. Fletcher, unpublished observations . Accordingly, sperm transport processes observed in the current study were unlikely to be influenced by the exogenous hormone treatment.

Morphologically, the structure of the possum oviduct was as previously reported ŽArnold and Shorey, 1985 and the luminal epithelium contained ciliated and secretory.

Ž .

cells as reported for other marsupials reviewed by Taggart, 1994 . The secretory cells stained positive for mucopolysaccharides, particularly in the ampulla during the peri-ovulatory period. These cells and those from the uterus were probably secreting mucoid and shell coat precursors, respectively, since after fertilization marsupial eggs acquire

Ž

these coats in transit from the oviduct to the uterus reviewed by Roberts and Breed, .

1996 .

The specialized sub-luminal isthmic sperm-storage crypts have been identified in three marsupial families. In these marsupials, the epithelium lining the isthmic crypts has a different morphology and staining properties to that of the main oviduct lumen: while the oviduct lumen is lined by mucoid-secreting and ciliated epithelial cells, the

Ž isthmic crypts are lined by non-mucoid secreting ciliated and non-ciliated cells D.

Õirginiana, Rodger and Bedford, 1982a; Bedford et al., 1984; S. crassicaudata, Breed et

.

al., 1989; A. stuartii, Bedford et al., 1984; Taggart and Temple-Smith, 1991 . Invagina-tions into the epithelium of the isthmus have also been described in the mouse and

Ž

hamster, with the former species having a unique epithelial cell type Smith et al., 1987; .

Suarez, 1987 . Further, oviduct crypts have recently been identified within a primitive

Ž . Ž

eutherian group of Insectivores-shrews Bedford et al., 1997 and moles Bedford et al., .

( )

M.K. Jungnickel et al.rAnimal Reproduction Science 59 2000 213–228 225

located in both the lumen and deep within folds or invaginations of the epithelium. However, the epithelium lining both the isthmic lumen and epithelial folds in the possum appeared to be morphologically identical and consisted of ciliated and mucus-secreting cells.

The highest numbers of spermatozoa were recovered from the oviduct around the onset of ovulation from 28.5 to 33 h after LH. Interestingly for the possum, more sperm were found in the ampulla during the peri-ovulatory and not the post-ovulatory period,

Ž

which differs from that documented for both eutherian mammals reviewed by Sultan

. Ž

and Bedford, 1996 and other marsupials e.g., S. crassicaudata, Breed et al., 1989; .

Bedford and Breed, 1994 . This suggests that the interval from ovulation to fertilization may be very short in the possum, confirmed in a recent study where early stage fertilized

Ž .

eggs were recovered from the ampulla, 33–39 h after AI Jungnickel et al., 1999 . At 12 h after insemination, sperm numbers in the ampulla and middle regions of the oviduct decreased, whereas isthmus numbers had actually increased. This latter result possibly reflects contamination from the uterus. Secretion of ovarian steroids during an oestrus cycle is known to alter the size and appearance of all regions of the possum reproductive

Ž .

tract Curlewis and Stone, 1987; Crawford et al., 1997 . At the 12-h sampling period,

Ž .

the utero–tubal junction was somewhat thickened externally , so it is possible that the isthmic flush contained sperm from the uterus. Alternatively, since the numbers of sperm depleted from the uterus are reflected in those recovered from the isthmus, it is possible that these sperm were being mobilized for later ovulations, since ovulation of the multiple follicles following PMSGrLH treatment in the possum occurs sequentially

Ž .

over several hours rather than simultaneously Glazier, 1999 . At all sampling periods, the oviduct was arbitrarily separated into three approximately equal segments, and subtle variations in these divisions may have contributed to the wide range of sperm numbers Žreflected in the standard errors flushed from these regions..

Possum sperm did not adhere to the epithelium lining the isthmic folds, but instead were aligned with their heads in close proximity to the microvilli of the epithelial cells

Ž

as reported for sperm in the isthmic crypts of dasyurids Breed et al., 1989; Taggart and .

Temple-Smith, 1991 . Spermatozoa were contained within the isthmic epithelial folds at 3 and 6 h after insemination, suggesting that isthmic colonisation in the possum may be restricted to a pre-ovulatory ‘window’, unlike certain other marsupial species in which

Ž .

sperm are stored in the isthmic crypts for extended periods up to 2 weeks before

Ž .

ovulation reviewed by Taggart, 1994 .

Ultrastructurally, spermatozoa within the isthmic lumen and epithelial folds were identical, and appropriate sections through the sperm head showed the presence of an intact acrosome, and there was no evidence of degeneration. This contrasts with the scenario in eutherians where a large proportion of sperm found in the oviduct lumen are acrosome-reacted, while others temporarily adhere to the apical plasma membrane of the isthmic epithelium so that sperm viability is maintained and capacitation proceeds at a

Ž

lower rate thereby prolonging the fertilizable life span of the sperm reviewed by Smith, .

1998 . The nature of the sperm–isthmic relationship in marsupials requires further investigation, but irrespective of whether sperm are stored in specialized crypts or sequestered into the isthmus as for the possum, it is likely that it serves as a means of

Ž .

The recovery of highly motile spermatozoa with T-morphology from the oviduct segments is evidence of at least some sort of maturational change to possum sperm during the pre-fertilization period in vivo. Re-orientation of the sperm head to the thumbtack configuration appears to be a prerequisite for fertilization in some Australian

Ž

marsupials based on in vivo observations Bedford and Breed, 1994; Molinia et al., .

1998 . However, thumbtack sperm recovered from the isthmus of S. crassicaudata were incapable of fertilization in vitro, suggesting that further maturational events are required

Ž .

before sperm could be classed as truly ‘capacitated’ Bedford and Breed, 1994 . In the possum, no thumbtack sperm were found in the uterus or vagina, but an increasing proportion were recovered in moving from the isthmus to the ampulla. This suggests that, like their eutherian counterparts, pre-fertilization changes in the possum may be initiated in the isthmus, then a wave of modified spermatozoa move through to the upper

Ž .

oviduct regions where fertilization occurs Yanagimachi, 1994 . The recovery of these in vivo modified sperm, particularly from the ampulla around the time of fertilization, are currently being used to attempt the fertilization of matured oocytes in vitro.

Acknowledgements

This study was undertaken with the financial assistance of the Australian Cooperative Research Centre Program and the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Policy Division. The authors thank L. Milne and the staff of the Landcare Research Animal Facility at Lincoln for the trapping handling and housing of possums in New Zealand.

References

Ž

Arnold, R., Shorey, C.D., 1985. Structure of the oviducal epithelium of the brush-tailed possum Trichosurus

.

Õulpecula . J. Reprod. Fertil. 73, 9–19.

Bedford, J.M., Breed, W.G., 1994. Regulated storage and subsequent transformation of spermatozoa in the fallopian tubes of an Australian marsupial Sminthopsis crassicaudata. Biol. Reprod. 50, 845–854. Bedford, J.M., Mock, O.B., Nagdas, S.K., Winfrey, V.P., Olson, G.E., 1999. Reproductive features of the

Ž . Ž .

eastern mole Scalopus aquaticus and star-nosed mole Condylura cristata . J. Reprod. Fertil. 117, 345–353.

Bedford, J.M., Mori, T., Oda, S., 1997. Ovulation induction and gamete transport in the female tract of the musk shrew Suncus murinus. J. Reprod. Fertil. 110, 115–125.

Bedford, J.M., Rodger, J.C., Breed, W.G., 1984. Why so many mammalian spermatozoa — a clue from marsupials? Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 221, 221–233.

Breed, W.G., Leigh, C.M., Bennett, J.H., 1989. Sperm morphology and storage in the female reproductive

Ž .

tract of the fat-tailed dunnart, Sminthopsis crassicaudata Marsupialia: Dasyuridae . Gamete Res. 23, 61–75.

Crawford, J.L., Shackell, G.H., Thompson, E.G., McLeod, B.J., Hurst, P.R., 1997. Preovulatory follicle

Ž .

development and ovulation in the brushtail possum Trichosurus Õulpecula monitored by repeated

laparoscopy. J. Reprod. Fertil. 110, 361–370.

Curlewis, J.D., Stone, G.M., 1987. Effects of oestradiol, the oestrous cycle and pregnancy on weight,

Ž

metabolism and cytosol receptors in the oviduct and vaginal complex of the brushtail possum Trichosurus

.

( )

M.K. Jungnickel et al.rAnimal Reproduction Science 59 2000 213–228 227

Ž .

Glazier, A.M., 1999. Time of ovulation in the brushtail possum TrichosurusÕulpecula following PMSGrLH

induced ovulation. J. Exp. Zool. 283, 608–611.

Glazier, A.M., Molinia, F.C., 1998. Improved method of superovulation in monovulatory brushtail possums

ŽTrichosurus Õulpecula using pregnant mares’ serum gonadotrophin-luteinizing hormone. J. Reprod..

Fertil. 113, 191–195.

Hunter, R.H.F., 1972. Local action of progesterone leading to polyspermic fertilization in pigs. J. Reprod. Fertil. 31, 433–444.

Hunter, R.H.F., 1988. Transport of gametes, selection of spermatozoa and gamete lifespans in the female tract.

Ž .

In: Hunter, R.H.F. Ed. , The Fallopian Tubes: Their Role in Fertility and Infertility. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp. 53–74, Chap. 4.

Hunter, R.H.F., 1995. Ovarian endocrine control of sperm progression in the fallopian tubes. Oxford Rev. Reprod. Biol. 17, 85–124.

Jolly, S.E., Scobie, S., Coleman, M.C., 1995. Breeding capacity of female brushtail possums Trichosurus

Õulpecula in captivity. N. Z. J. Zool. 22, 325–330.

Jungnickel, M.K., Harman, A.J., Rodger, J.C., 1999. Ultrastructural observations on in vivo fertilization in the brushtail possum, TrichosurusÕulpecula, following PMSGrLH superovulation and artificial insemination.

Zygote 7, 307–320.

Karnovsky, M.J., 1965. A formaldehyde-gluteraldehyde fixative of high osmolarity for use in electron-mi-croscopy. J. Cell Biol. 27, 137A–138A.

Mate, K.E., Giles, I., Rodger, J.C., 1992. Evidence that cortical granule formation is a periovulatory event in marsupials. J. Reprod. Fertil. 95, 719–728.

Mate, K.E., Rodger, J.C., 1996. Capacitation and the acrosome reaction in marsupial spermatozoa. In: Marsupial Gametes and Embryos. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 8, 595–603.

Molinia, F.C., Gibson, R.J., Brown, A.M., Glazier, A.M., Rodger, J.C., 1998. Successful fertilization after superovulation and laparoscopic intrauterine insemination of the brushtail possum, TrichosurusÕulpecula,

and tammar wallaby Macropus eugenii. J. Reprod. Fertil. 113, 9–17.

Moore, H.D.M., Taggart, D.A., 1993. In vitro fertilization and embryo culture in the grey short-tailed opossum Monodelphis domestica. J. Reprod. Fertil. 98, 267–274.

Pearse, A.G.E., 1968. Histochemistry, Theoretical and Applied. 3rd edn. Churchill, London.

Roberts, C.T., Breed, W.G., 1996. Variation in ultrastructure of mucoid coat and shell membrane secretion of a Dasyurid marsupial. In: Marsupial Gametes and Embryos. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 8, 645–648.

Ž .

Rodger, J.C., 1991. Fertilization in marsupials. In: Dunbar, B.S., O’Rand, M.G. Eds. , A Comparative Overview of Mammalian Fertilization. Plenum, New York, pp. 117–135.

Rodger, J.C., Bedford, J.M., 1982a. Induction of oestrus, recovery of gametes and timing of fertilization events in the opossum DidelphisÕirginiana. J. Reprod. Fertil. 64, 159–169.

Rodger, J.C., Bedford, J.M., 1982b. Separation of sperm pairs and sperm–egg interaction in the opossum

DidelphisÕirginiana. J. Reprod. Fertil. 64, 171–179.

Rodger, J.C., Cousins, S.J., Mate, K.E., 1991. A simple glycerol-based freezing protocol for the semen of a marsupial, TrichosurusÕulpecula, the common brushtail possum. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 3, 119–125.

Selwood, L., 1982. A review of maturation and fertilization in marsupials with special reference to the

Ž .

Dasyurid: Antechinus stuartii. In: Archer, M. Ed. , Carnivorous Marsupials. Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales, Sydney, pp. 53–76.

Shimmin, G.A., Jones, M., Taggart, D.A., Temple-Smith, P.D., 1999. Sperm transport and storage in the agile

Ž .

Antechinus Antechinus agilis . Biol. Reprod. 60, 1353–1359.

Sidhu, K.S., Guraya, S.S., 1989. Cellular and molecular biology of capacitation and acrosome reaction in mammalian spermatozoa. Int. Rev. Cytol. 118, 231–280.

Smith, T.T., 1998. The modulation of sperm function by the oviductal epithelium. Biol. Reprod. 58, 1102–1104.

Smith, T.T., Koyanagi, F., Yanagimachi, R., 1987. Distribution and number of spermatozoa in the oviduct of the golden hamster after natural mating and artificial insemination. Biol. Reprod. 37, 225–234.

Suarez, S.S., 1987. Sperm transport and motility in the mouse oviduct: observations in situ. Biol. Reprod. 36, 203–210.

Taggart, D.A., 1994. A comparison of sperm and embryo transport in the female reproductive tract of marsupial and eutherian mammals. In: Marsupial Reproduction: Gametes, Fertilization and Early Develop-ment. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 6, 451–472.

Taggart, D.A., Shimmin, G.A., McCloud, P., Temple-Smith, P.D., 1999. Timing of mating, sperm dynamics,

Ž .

and ovulation in a wild population of agile Antechinus Marsupialia: Dasyuridae . Biol. Reprod. 60, 283–289.

Taggart, D.A., Temple-Smith, P.D., 1991. Transport and storage of spermatozoa in the female reproductive

Ž .

tract of the brown marsupial mouse Antechinus stuartii Dasyuridae . J. Reprod. Fertil. 93, 97–110. Tyndale-Biscoe, C.H., Rodger, J.C., 1978. Differential transport of spermatozoa into the two sides of the

Ž .

genital tract of a monovular marsupial, the tammar wallaby Macropus eugenii . J. Reprod. Fertil. 52, 37–43.

Ž .