Between conformity and critique: Doing social science under

Orde Baru

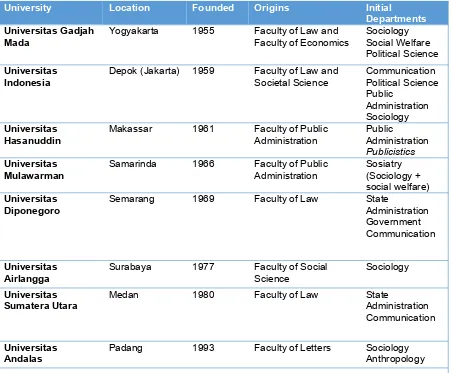

Upon their return from overseas training, most Indonesian social scientists under the New Order (1965-1998) were preoccupied with helping to create the infrastructure for doing their work. This is evident in the number of Faculties in Social and Political sciences established in the 1960s as depicted in the table below. The late arrival of social science and humanities in Indonesia comes as no surprise as most universities were only established in the 1920s, comprised of faculties of engineering, medical science and law (LP3ES, 1983:58). As shown in the table below, Universitas Gadjah Mada was the first university to establish a faculty for social and political science, in 1955. This was then followed by Universitas Indonesia and other universities who gradually established their faculties respectively until the 1990.

University Location Founded Origins Initial

Departments

Universitas Gadjah

Mada Yogyakarta 1955 Faculty of Law and Faculty of Economics SociologySocial Welfare Political Science

Universitas

Indonesia Depok (Jakarta) 1959 Faculty of Law and Societal Science CommunicationPolitical Science Public

Administration Sociology

Universitas

Hasanuddin Makassar 1961 Faculty of Public Administration Public Administration

Publicistics

Diponegoro Semarang 1969 Faculty of Law State Administration Government

Sumatera Utara Medan 1980 Faculty of Law State Administration Communication

Universitas

Andalas Padang 1993 Faculty of Letters SociologyAnthropology

The task of setting up the necessary infrastructure for teaching comes with the inevitable question of constructing an adequate content. With many scholars having only returned from the US, it is no coincidence that prevailing ideas in American social science were borrowed by their Indonesian counterparts. An indicative list of Indonesian scholars obtaining their academic credentials can be seen in the table below.

Name Depart

ure University Major Degree Return Notes

Selo

Soemardjan 1956 Cornell Sociology PhD 1959

Koentjaraningrat 1954 Yale Anthropology PhD 1956

1957 Established Department of Anthropology at UI

Soedjatmoko 1960 Cornell LecturerGuest 1962 Harsja Bachtiar xxx HarvardCornell, PhD

Mely G Tan xxx Cornell, UCBerkeley PhD

Soelaeman

Arief Budiman xxx Harvard Sociology Phd 1980

Daniel Dhakidae xxx Cornell PhD 1991

Mansour Fakih 1990 MassachusseUniversity of tts

1997 established Insist

Taufik Abdullah xxx Cornell History Phd 1970 George Junus

Aditjondro xxx Cornell PhD 1992

Ignas Kleden

Table 2. Almamater of early Indonesian social scientists

It is in this formative years where Samuel argues of the major influence of American social science. This is supposedly especially evident in the hegemony of functionalism, a theory introduced by Talcott Parsons, who himself only came to prominence in the US by way of introducing European thoughts (Ritzer, 2011: 210). Parson’s functionalism, Samuel claims, was well received and adopted by many indonesian scholars trained in the US during the 1960-1970s period.

theories drawing on the Frankfurt School and in development studies, Dependency Theories. Early proponents of a more critical approach in social science have found their home in the works and publications of LP3ES, as well as its their well-respected Prisma journal.

To this point, in a wider public discourse, the intellectual circle had already witnessed other important debates that impacted the cultural and social realm. The key battles will be discussed in the sections below.

1. The cultural question: Nationalism vs Westernisation

Prior to the prevalence of ‘modernisation’ and functionalism in social science, the cultural sphere went through existential questions of what it meant to be Indonesian. The Cultural Polemic (Polemik Kebudayaan) as it was called (1954), saw an extensive exchange between Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana (STA) and Sanusi Pane, who alleged the former for being an agent of westernisation and abandoning Indonesian roots and values in his writings.

Like other common intellectual debates, the dispute remain unsettled but provided a taste of how narratives were easily framed in a dichotomous, binary manner and had an underlying message that serving the interests of the nation was supposed to be the true calling of all intellectuals and theirlike. Polemik Kebudayaan simultaneously portrayed an important self-awareness among intellectuals that would continue to grow as questions regarding their roles would be brought up in the course of time, only to be halted by a much troubling theme: ideology.

2. The ideological turn

Preceded by political upheaval and an attempted coup d’etat in 1965, social science found itself in the midst of an ideological battle. Soeharto’s rise to power in 1966 came with consequences to the teachings of Marxism. With Marxist thought closely associated with communism, all literature and Marxism-related material were banned and confiscated. The repression on Marxist literature deprived students of important subjects in the field of sociology and also students in Economics, who missed out on critical perspectives regarding economic development and global capitalism.

Kebudayaan (MANIKEBU). The battle highlighted a highly polarised society with ideological questions spilling over into the realms of social science.

One of the most significant consequence to the field of social sciences is the absence of class analysis, leaving social research with a static framework that neglects to discuss social tensions engendered by unequal power relations (Hadiz and Dhakidae, 2005: 168). Indonesian scholars influenced by Marxism were nonetheless present. If anything, the ban on Marxism created a myth of the subject that helped to grow the curiosity of students. Scholars such as George Junus Aditjondro and Arief Sritua would have loyal circle of Marxist-enthused students, but are in the eyes of the modernists and government-loyal technocrats remained as outlaws. Given the death of studies using a Marxian framework, it is no surprise that one of the first work using a class analysis in the Marxian discourse would only appear in the late 1980s, namely Richard Robison’s the Rise of Capital (1986) (Hadiz and Dhakidae, 2005: 169).

To find their way around the ban, scholars keen to adapt critical perspectives against capitalism would strategise by adopting variations of Marxist thoughts without having to highlight the presence of Marx himself in the readings. This would include adopting a critical stance towards developmentalism and finding refuge in the concepts of ‘empowerment’ and ‘participation’.

This was an effective strategy used in the works of Daniel Dhakidae (who was Prisma’s Head of Editorial Board between 1979-1984), Adi Sasono and Sritua Arief (who published Dependency and Underdevelopment in 1981) and also in the works of other scholars leaning towards alternative stream of thoughts, such as Mansour Fakih or ‘populist economists’ such as Mubyarto and Dawam Rahardjo.

3. Between Modernisation, Developmentalism and Critical Social Science

The main period of Orde Baru saw social scientists shaping disciplines that help Indonesian society to become part of modernizing world. They did so by promoting and applying ideas of objective science, becoming ‘value-free’ scholars and aiding development agendas with the use of their scientific methods.

According to Samuel, this prevalence of modernization theories promoted a mutual trust shared between the modernist social scientist with the state bureaucracy. In his words, this accorded with their tendency to hold reformist and non-radical attitudes (Samuel, 2007:5). He continues by stating that scholars provided ‘scientific apology’ for attempts to maintain the predominance of the state over civil society, providing knowledge for decision makers to strengthen the state bureaucracy (Samuel, 2007: 2006).

Despite the hegemony of modernists scholars, Orde Baru also witnessed the emergence of new universities and study groups. A small circle of social scientists at Universitas Kristen Satya Wacana (UKSW) in Salatiga, Central Java, would play a significant role in adding variety to the discourse. This small group of intellectuals, most prominently represented by Arief Budiman, Ariel Heryanto, George Junus Aditjondro, are known for their fondness in using critical perspectives to contest on going debates on development and democracy.

The discourse on community development builds heavily on critical agrarian studies and studies on rural sociology or rural development. Here is where the teachings of Prof. Ben White and the late Prof. Sajogyo are of importance and relevance. The thoughts of Sajogyo in particular has a lasting impact on theory and method, as he designed an ingenious tool to measure poverty level in rural areas. Over his career, Sajogyo would prove to be an exemplary scientist who not only managed to achieve academic reputation but also become an expert and consultant for various government-led projects, being involved in the large scale intensification programme of the green revolution (Revolusi Hijau). He embodies the role of a wise technocrat whilst earning the respect of his fellow scientific peers.

This is partly what George Junus Aditjondro had in mind when stating the shift of social sciences from state-oriented to society-oriented (pro-Negara to pro-masyarakat) (1997:41). He took note of the move away from state-centrism towards a clearer emphasis on the community and publicness of sociology in particular. This move is not geared by social scientists only, but is a consequence of the widening influence of non-governmental organisations and the growing civil society itself.

4. The role of the intellectual and democratisation

When discussing the role of social science in development, Selo Soemardjan emphasised the importance of objectivity as social scientists are above all, scientists (1983: 50). Yet the role of scientists as opposed to intellectuals has often been subject of heavy debates among the Indonesian intellectual circle. One book that was often cited at that particular time is Julien Benda’s Treason of the Intellectual (1927). The main premises of the book are often referred to as a reminder to Indonesian intellectuals to stay true and loyal to their calling, that is the pursuit of truth and to contribute to the fullest to the development of Indonesia. The role of the scientist in the particular context of New Order creates an inherent tension in juggling between commitments. Especially during the New Order, social scientists seemingly had to choose between being within the circle of power or outside of it (LP3ES, 1983).

This goes in line with Samuel’s argument on how institutionalisation of social science was only made possible by the obedience of its scholars towards the state. The emphasis of then social scientists was directed towards fostering a ‘harmonious society’, conditions to be created through planned intervention (Samuel, 2007: 10). Scholars had to adopt a co-operative attitude and go along with prescriptive orders, most visible in avoiding theories with ideological baggage, best exemplified by Marxism. According to Samuel, Soeharto was always happy having to work with scientists who were ‘optimistic, pragmatic and supportive of the state bureaucracy’ (Samuel, 2007:9).

non-research activities” she added (Hadiz and Dhakidae, 2005:68). A similar observation was made by Michael Morfit who was also cited by Ariel Heryanto (1981): “Until 1971, almost every ministry established a research and development section to carry out what was referred to as policy oriented research”.

For all of the ‘conformity and compliance’ of social scientists during the Orde Baru, there have also been the awareness of the need to ‘democratise’. This is the biggest concern of Soeharto’s administration and one of the main reasons to monitor academic associations more closely. Whilst not always being at the centre of events, intellectuals would find themselves right in the middle of student protests and uprisings against Soeharto’s regime. This is also related with persistent student movements that led to several unrests during Orde Baru and made the university a battlefield between academic freedom and government control1. The

need to discipline students eventually led to the monitoring of universities and left little room for teachers to give critical lectures and question political agendas.

Even though the majority of scholars made democratisation their business, none could have predicted the outcome of the Asian monetary crisis as Soeharto left his throne in 1998. The reform movement was credited to the students and their resolute movement, with little credit given to the intellectual circle as they were commenting the proceedings whilst observing the change they also have been anticipating. Eventually, 1998 became a watershed moment that changed the preconditions of doing social science.

Epilogue

The state of social science in Indonesia under Orde Baru has always been influenced by political agendas and cultural sentiments. The role of ideology became even more apparent against the backdrop of the events surrounding the 1965 attempted coup d'état and the ensuing ban on Marxist literature.

Under a strong state hegemony, social science seemingly followed a singular path of modernisation, evidently manifested in both thought (e.g. dominant teachings on functionalism) and practice (the use of science for developmental application). This leaves

1 This is best exemplified by the normalisation of university activities under the Normalisasi

sparse room for doing critical social science: adopting variations of Marxist theory to counter state-driven development agendas under the framework of empowerment and bottom-up participation.

For the majority of social researchers, the common way of doing science is by playing it safe, as the increasing control of government meant greater scrutiny of curriculum, research projects and even non-academic activities inside or outside the university. As scientists had little choice but to conform, students would take a greater role in rattling Soeharto’s establishment. When democratisation eventually gathered pace, the role of intellectuals would again be put into question as it always has been from the early days of the republic.

Bibliography

1. Hadiz, Vedi.R. and Dhakidae, Daniel. 2005. Social science and power in Indonesia. Singapore: Equinox Publishing.

2. Kleden, Ignas. 1987. Sikap Ilmiah dan Kritik Kebudayaan. Jakarta: LP3ES

3. LP3ES.1983. Cendekiawan dan Politik (Intellectuals and Politics). Jakarta: LP3ES

4. Nordholt, Nico.G.Schulte and Visser, Leontine. E. 1997. Ilmu Sosial di Asia Tenggara (Social Science in Southeast Asia). Jakarta: LP3ES.

5. Ritzer, George. 2011. Sociological Theory, Eight Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. 6. Samuel, Hanneman. 2007. Indonesian Social Sciences: Looking Back, Creating the

Future. Depok: Labsosio Universitas Indonesia